Abstract

Purpose

Explore contraceptive use, unmet need of and attitudes towards contraceptive use in Sweden. Secondly, to investigate knowledge of contraceptives, prevalence and outcomes of unintended pregnancies.

Materials and methods

Internet based e-survey of Swedish women aged 16–49. The e-survey contained 49 questions with both spontaneous and multi-choice character on demographics, contraceptive use, knowledge of and attitudes towards contraception, importance of monthly bleeding, and experience of unintended pregnancy. The e-survey was closed when reaching the estimated sample size of 1000 respondents.

Results

A total of 1016 women participated, whereof 62.4% used contraception, 31.8% did not and 5.8% had stopped in the last 12 months. Unmet need for contraception was estimated at 17.2%. At least one unintended pregnancy was experienced by 19.9%. All women rated effectiveness as the most important characteristic of a contraceptive method.

Conclusions

Use of contraception in Swedish women remains low, 62.4%, and the unmet need for contraception has increased to 17.2%. Method effectiveness and health benefits of hormonal contraception should be emphasised during contraceptive counselling, and actions are needed to target groups with low use of effective contraception as well as to reach those who never seek contraception.

Close to one third of Swedish women do not use contraception and one fifth have experienced at least one unintended pregnancy. Unmet need for contraception is high despite easy access and subsidies for young women.

KEY MESSAGE

摘要

目的:探索瑞典的避孕措施、未满足的避孕需求和对避孕措施的态度。其次, 调查避孕知识、意外怀孕的发生率和结局。

材料和方法:对16-49岁的瑞典女性进行基于互联网的电子调查。电子调查包含49个问题, 涉及人口统计特征、避孕措施、避孕知识和态度、月经的重要性以及意外怀孕的经历等方面, 这些问题都是自发和多选的。在达到1000名受访者的估计样本量时结束电子调查。

结果:共有1016名女性参加, 其中62.4%采取避孕措施, 31.8%不采取避孕措施, 5.8%在最近12个月内停止采取避孕措施。未满足的避孕需求约占17.2%。19.9%的人至少经历过一次意外怀孕。所有女性都将有效性视为避孕措施最重要的特征。

结论:瑞典女性的避孕措施采取率仍然很低, 为62.4%, 未满足的避孕需求已增加到17.2%。在避孕咨询时应强调激素避孕方法的有效性和健康益处;我们需要采取行动, 针对有效避孕措施采取率低的群体, 以及那些从未采取避孕措施的群体。

Introduction

Globally, about 61% of all unintended pregnancies end in abortion, corresponding to a rate of 39 abortions per 1000 women in fertile age. Access to effective and acceptable contraception and legal access to abortion is linked to low rates of unintended pregnancy and unwanted pregnancies ending in abortion [Citation1]. Among western European countries, Sweden has a unique position with comparatively high fertility and birth rates, but also the highest abortion rate [Citation2]. Whereas physicians are the main providers of contraception in most countries, the Swedish model includes contraceptive counselling free of charge, provided by trained nurse-midwives mainly at youth- and midwifery clinics. Through national subsidies, users can access most contraceptives, including long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARC, intrauterine contraception and contraceptive implants) and short-acting reversible contraceptives (SARC, pills, patch and ring) free of charge up to 21 years of age, and to an annual cost of approximately 10 euros (€) up to 26 years of age. The model assumes that ready access and subsidies increases contraceptive use and lowers unwanted pregnancies. However, the Swedish abortion rate has remained stable at around 20 per 1000 women of fertile age since reporting started in 1995 [Citation3].

In recent years, a decline in abortion rates have been seen, especially among women aged 15–19 and 20–24 years [Citation3]. This trend is similar to most European countries but reasons for the decline are unknown and may be multifactorial. The Swedish Board of Health and Welfare proposes one reason to be the increased use of LARC methods, known to effectively decrease first and repeated unwanted pregnancies in general, but especially in young women who may have more difficulties with daily, weekly or monthly administration [Citation4–6]. Despite this, Sweden still has higher abortion rates than other Nordic countries [Citation7]. As counselling and cost affects contraceptive method choice and initiation [Citation4,Citation8,Citation9], it is increasingly important to understand attitudes related to contraception and unintended pregnancy, and what factors affect contraceptive use to meet demands and needs of women. To increase knowledge on attitudes and experiences of Swedish women concerning contraceptive use, nationwide telephone surveys were carried out in 2013 and 2017 [Citation10,Citation11]. In May 2021 we performed an internet based nationwide e-survey with the primary objective to explore current use of contraception and attitudes towards contraceptive use in Sweden. Secondary objectives were to investigate the knowledge women have of contraceptive methods, reasons for non-use of contraception, and how unintended and unwanted pregnancies are dealt with.

Reporting follows the CHERRIES checklist for internet e-surveys [Citation12].

Material and methods

The e-survey was performed by Kantar SIFO. Kantar is a global company specialised in market surveys and consultancy. The target population were women of fertile age, and the sample frame included all women between 16 and 49 years old identified in the ‘SIFO-panel’, an online-panel of about 100,000 individuals recruited through nationally representative surveys on a random sample (i.e., no self-admission). The target population were invited to participate in the web-based e-survey via unique links sent by email. The e-survey was open only to those invited, with a quota for each age strata to ensure that all age groups were well represented. The survey was available in the Swedish language and closed after the estimated sample size was reached (approximately 1000 women). All participants in the ‘SIFO-panel’ receive incentives to answer questionnaires in the form of ‘points’ which can be traded for items (S3 Document: Supplementary information about the SIFO-panel).

Invited women were informed about the objectives of the e-survey, that it was performed and analysed by independent researchers but funded by a pharmaceutical company (Bayer Sweden AB). They were also informed that completion would require approximately 15 min, that answering questions was voluntary, that they could quit taking the e-survey at any time, and that all personal information would be coded and maintained confidential even to the researchers. Informed consent for participation was by continuing the e-survey after the initial information.

The e-survey contained 49 questions with one question per page. The participants could follow their own rate of completion, review their answers, and make changes until final submission. Adaptive questioning depending on previous answers was used to reduce the number of questions. To ensure 100% completion, all displayed questions were mandatory but included non-response options such as ‘I do not know’, ‘not applicable’ or ‘rather not say’. The e-survey’s structure and questions were modelled from an Austrian contraceptive survey performed in 2012 [Citation13], and were modified from our previous surveys with high participation and completion rate to match the new e-survey format [Citation10,Citation11]. No testing of the survey was made prior to fielding.

The e-survey consisted of eight questions on demographic characteristics of women such as age, employment status, educational level, civil status, income in the household, and ethnic background (born in Sweden, parents born in Sweden, etc.).

There were nine COVID-pandemic related questions on access and use of contraception during the pandemic (not further described in this publication).

There were 32 questions on choice of contraceptive method, knowledge on contraceptive methods, criteria on aspects important for contraceptive choice, reasons for not using contraception (for women not currently using contraception), perceived knowledge on the efficacy of different contraceptive methods, opinion on importance of monthly bleeding or absence thereof, perceived problems during contraceptive use, opinions about how information on contraception can be improved, and experience of unwanted pregnancy.

Statistical analysis

It was estimated that 1000 women would be sufficient to enable valid subgroup analyses of different age intervals according to our previous experiences. Data from completed e-surveys was automatically entered in an electronic database used for analysis. No answers from discontinued e-surveys were included. Except the quotas for age, no statistical corrections were applied to adjust for a possible non-representative sample. Demographic characteristics such as age, migrant background, residential area, educational level, and income were compared to information available in open electronic databases provided by the Swedish Tax Authority and Statistics Sweden.

The unmet need for contraception was defined as ‘at risk of pregnancy among those being fecund (i.e., not diagnosed infertile/partner diagnosed infertile, having had hysterectomy, using contraception etc.) and heterosexually active without a reported pregnancy desire, and calculated according to Supporting information, Table S1.

Descriptive statistics were used to display frequencies. Group differences were analysed by Fisher’s exact test and a two-sided p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were analysed with SPSS Statistics 28 (IBM, Armonk, NY).

Ethical approval

Ethical permission is not required for anonymous surveys in Sweden where the commissioner of the report does not have access to identifying data.

Results

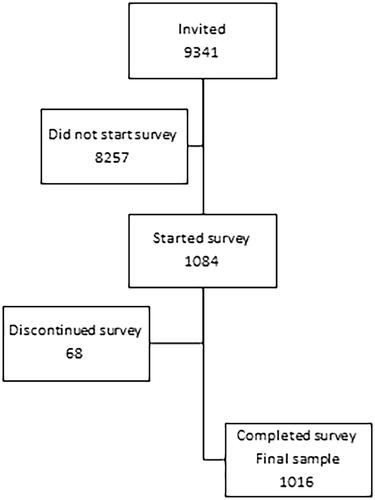

The invitation was sent 9 June 2021. In total 9341 women between 16 and 49 years were invited to take the e-survey. The target sample size was set at approximately 1000 women, and when this was reached the survey closed and the invitation for participation was withdrawn for the remainder of women. While open, a total of 1084 women started the e-survey, whereof 68 discontinued. The known demographic information of women who discontinued was analysed and found to have the highest discontinuation rate of approximately 30% in the age group 41–49 years. The final study population consisted of 1016 participants. The e-survey closed 18 June 2021. The flow of participants is described in . There were fewer women born abroad who participated in the e-survey (45/1016, 4.4%) compared to the population of this age group (26.6%) whereas the women born in Sweden with one or two parents born abroad were well represented at 13.0% (132/1016) compared to 13.6% in the general female population of this age group (manual calculations based on official statistics) [Citation14]. Participants in our e-survey had a higher educational level and a higher household income compared to the general Swedish population through official statistics of Statistics Sweden. Our sample represent the Swedish female population well with regards to residential area, civil status, and employment status, according to census information in Sweden (results not shown). The demographic characteristics of women who participated in the e-survey are shown in .

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of participants by age group.

Among all participants, 634/1016 (62.4%) women stated that they currently used contraception, 323 (31.8%) women did not use contraception, and 59 (5.8%) had stopped using contraception sometime during the last 12 months.

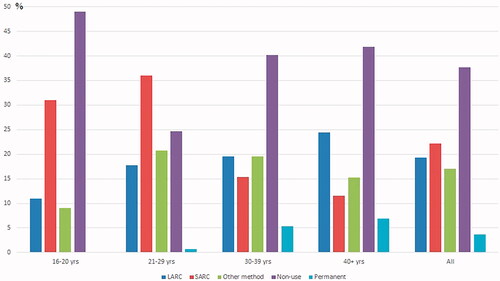

The distribution of contraceptive methods used in different age groups is presented in . Two women did not wish to state which method they used. Use of short-acting reversible contraceptives (SARC) was highest in the group of women 16–20 years old and then lowered with increasing age. LARC use was lowest in younger age groups and thereafter rose with increasing age. The use of other methods such as the condom or emergency contraceptive pills had a peak at 21–29 years and thereafter fell. A total of 278/1016 (27.4%) used less effective methods (any method but sterilisation, LARC and SARC).

Figure 2. Main contraceptive method used the last 12 months. LARC: long-acting reversible contraception; SARC: short-acting reversible contraception; Permanent: male and female sterilisation.

The reasons for not using contraception differed in different age groups, and the results are presented in .

Table 2. Reasons for non-use of contraception by age group.

Contraceptive method awareness differed for most contraceptive methods (), with a generally higher awareness among current users compared to non-users. In both groups, the male condom was the contraceptive method most women were aware of. Method awareness also differed between age groups. Women below 20 years had the lowest awareness of all types of contraceptives except for the patch and contraceptive apps where the lowest awareness was seen in the group above 40 years. Women above 30 years were significantly more aware of the diaphragm (results not shown, p < 0.001).

Table 3. Awareness of different contraceptive methods.

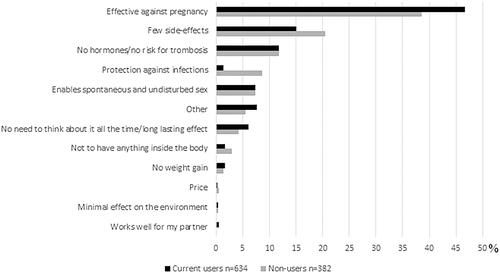

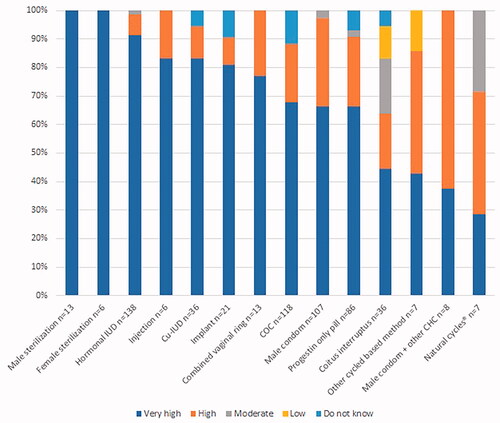

Both current users and non-users stated that the effectiveness is the most important characteristic of a contraceptive, but with a higher proportion among current users (296/634, 46.7%) compared to non-users (147/382, 38.5%, p < 0.001). The importance of different characteristics of contraceptive methods are given in . Users’ estimates on the effectiveness of their methods are shown in .

Figure 4. Users’ estimated effectiveness of their method (n = 634). Patch: combined hormonal patch; Hormonal IUD: levonorgestrel intrauterine device; injection: high dosed progestin only injection; COC: combined oral contraceptive pill; CHC: combined hormonal contraception; ECP: emergency contraceptive pill.

Among current or ever-users of the contraceptive pill, 26.5% (n = 209/789) stated they had experienced frequent side effects. The second most common problem was that women admitted to forgetting to take one or several pills. A total of 10.5% (83/789) stated that this happens/happened often. The details on problems experienced during pill usage are outlined in Supporting information, Figure S1. Problems related to the use of the male condom are outlined in Supporting information, Figure S2.

In total, 62.5% (635/1016) of participants would find it positive to be without monthly bleeding for a longer period. Out of the 1016 women in the e-survey, 153 (15.1%) did not want to be without menstrual bleeding, and 74 (7.3%) were undecided. The remainder of women (154, 14.7%) would find it positive with fewer and less bleedings. Women above 40 years were significantly more positive to being without bleedings or having less bleedings with 271/321 (84.4%) indicating that this would be positive, whereas the corresponding proportion in the youngest age group was 105/145 (72.4%). (p = 0.003). Most women (789, 77.7%) were ever users of contraceptive pills. Among ever users of combined oral contraceptives, skipping the hormone free break (i.e., no pills or placebo pills) to avoid a monthly bleeding was done routinely by 23.6% (n = 186), sometimes by 30% (n = 241), once by 8.2% (n = 65) and never by 43.2% (n = 341). Among current users of combined hormonal contraception (n = 133), 65 women (58.9%) skipped breaks regularly, whereas 26 (19.5%) skipped breaks sometimes, 7 had done it once (5.3) and 33 (24.8%) always took the hormone free break (missing n = 2).

When asked about use of emergency contraception, seven women (0.7%) stated not being aware of this method. A total of seven women (0.7%) had used a copper intrauterine device for emergency contraception. A total of 133 women (13.1%) had used emergency contraception three times or more.

The majority of women (814/1016, 80.1%) stated that they had never had an unintended pregnancy whereas 202 (19.9%) women had experienced at least one unintended pregnancy. There was a total of 286 unintended pregnancies whereof 102 (35.7%) resulted in childbirth, 151 (52.8%) in abortion, 28 (9.8%) in miscarriage, and four (1.4%) were ectopic pregnancies. Four participants chose not to answer how they handled their unintended pregnancy. Unintended pregnancies occurring due to non-use of contraception and contraceptive failure are shown in .

Table 4. Contraceptive method used at the time of fertilisation of unintended pregnancies.

The unmet need for contraception was calculated at 17.2% (132/766). Factors affecting the calculation is found in supporting information, Table S1. In addition, 173/631 (27.4%) used less effective methods (other methods than hormonal, intrauterine or permanent contraception).

Discussion

Findings and interpretation

In this nationwide e-survey 32.1% of women did not currently use contraception. Effectiveness was the most important characteristic of contraception. A total of 814 women (80.1%) had never experienced an unintended pregnancy whereas 202 women (19.9%) had experienced at least one unintended pregnancy. This confirms the relatively high proportion of women in Sweden who experience unintended pregnancies. The unmet need for contraception was calculated at 17.2%.

Differences and similarities in relation to other studies

Users and non-users alike stated that one of the most important characteristics of a contraceptive method is its effectiveness, but users grossly overrated the effectiveness of the male condom and combined oral hormonal contraception but underestimated effectiveness of all LARC methods. These results are consistent with our previously published surveys [Citation10,Citation11]. Overestimation of the effectiveness of the currently used method may well explain the high proportion of unwanted pregnancies and abortions in Sweden. It has been shown that women choose more effective methods and especially LARCs when effectiveness is emphasised in contraceptive counselling [Citation8,Citation15].

In our study, 49% of women in the age group 16–20 years stated that they did not use contraception, whereof 40% stated that it was because they are not sexually active. Meanwhile, above 40% of participants in this age group used highly effective methods such as LARCs and SARCs. In Sweden, there has been a rapid reduction in the teenage abortion rates and Sweden now has an internationally low abortion rate in this age group at 8.9/1000 women [Citation16]. The Swedish Society of Obstetrics and Gynaecology has promoted use of LARCs especially for young women at risk of pregnancy since the publication of the contraceptive CHOICE project in Missouri, USA, in 2012[Citation4,Citation17] and the recent large LOWE study on contraceptive counselling confirmed that uptake of LARC increased in youth clinics when effectiveness, added health benefits and the lack of need for daily intake was stressed in counselling [Citation8]. Thus, the reduced need for abortions in this age group may be due to identification of young women at risk for pregnancy and subsequent provision of highly effective contraception. Similar trends with change from SARC to LARC use in users of contraception has been seen in the United States [Citation18] and the Nordic countries [Citation19]. The study from the United States also concluded that non-use is constant and not affected by these trends.

The unmet need for contraception in this study was 17.2%. Unmet need for contraception is seldomly calculated due to difficulties in obtaining information on use of non-hormonal method such as cycle-based methods and coitus interruptus. Attempts to calculate unmet need has been done in the United States (10%) [Citation18] and France (<3%) [Citation20] and may be used for comparison to our results although the system for contraception in the US differs significantly from that in Europe. The unmet need of contraception in Sweden is difficult to explain and troublesome as contraception is easy to access in maternal health clinics and youth clinics and that subsidies apply up to the age of 26 years. In addition, a large proportion of Swedish women (27.4% of contraceptive users) use methods with a lower effectiveness. This is a considerably higher proportion than in France where only 15% of women use less effective methods [Citation21]. The difference in use of effective methods of contraception and the proportion of women with an unmet need for contraception may well account for the differences in abortion rates between Sweden and other western European countries.

Among women experiencing an unintended pregnancy despite using contraception, user dependent methods were most common whilst very few (3.5%) were experienced while using LARC. Increasing LARC use could therefore lower rates of unintended pregnancies and abortion. Recently the concept of ‘contraceptive coercion’ has been launched in response to the increased push for use of LARCs. ‘Contraceptive coercion’ implies dissatisfaction with counselling and a feeling of being coerced into using contraception or a certain contraceptive method. However, in a study of increased use of LARCs after structured contraceptive counselling focussing on contraceptive effectiveness and health benefits of all types of hormonal contraceptives [Citation8], patients were very satisfied and felt supported in their choice of contraception [Citation22]. The satisfaction was equally high also among immigrants [Citation23]. Similar effects were seen in Australia, where women who received effectiveness-based structured contraceptive counselling with rapid referral pathways to LARC insertion clinics initiated LARCs during the study period to a higher extent compared to women who received the usual contraceptive care [Citation24]. Both providers and patients valued the effectiveness approach [Citation25]. This suggests that methods for LARC-forward counselling do not necessarily imply a feeling of coercion.

A majority of women (62.5%) stated that it would be positive to be without monthly bleeding. Yet only 50.4% of current users of combined hormonal contraception had ever skipped the hormone free break. Having a shorter pill free break has been shown to increase the effectiveness of oral combined hormonal contraception[Citation26] and wellbeing [Citation27,Citation28]. Implementation of this regimen can still be improved in Sweden.

Strengths and weaknesses

A strength of this e-survey is the large sample size of 1016 women and the short period of data collection. The major limitation of the e-survey is that it is an internet-based survey with a possible selection bias. We reduced bias as women did not know the topic of the e-survey before they opened it and we could analyse age in women who discontinued the survey. Telephone surveys are becoming increasingly difficult to perform as few answer calls from unknown phone numbers and thereby become expensive with a large selection bias. We therefore decided to use an internet-based survey through an established provider. Less than 7% of those starting the e-survey chose to discontinue and there are few missing answers. There were differences in background characteristics among the participants in the e-survey compared to official statistics available in Statistics Sweden. The levels of education and income where higher, whereas there was a lower proportion of women born abroad in our study population. It is known that immigrant women often have lower contraceptive use. Reaching immigrant women is difficult and poses a dilemma for all research.

It was difficult for women to differ between medium dosed and low dosed progestin only pills. We therefore had to pool all progestin only pills into one category although they differ in effectiveness and user dependency. Use of the low dosed progestin only pills is very low in Sweden.

Relevance of the findings: implications for clinicians and policy-makers/health care providers

This e-survey of contraceptive use and attitudes towards contraception shows a high unmet need for contraception despite easy access and available subsidies for the groups at the highest risk for unintended pregnancy. Women express that contraceptive effectiveness is the most important quality of a contraceptive, but method specific knowledge on contraceptive effectiveness of the currently used method is lacking and a high proportion of women use less effective methods. Also, awareness of different methods differed considerably depending on age, indicating the importance of continuous information of all contraceptive methods at counselling so that they can actively choose and not be at risk of passive continued use of a method which may not suit them the best. A large proportion of women have experienced at least one unintended pregnancy with slightly above 50% of these ending in abortion. Increasing knowledge on fertility and awareness of contraceptive effectiveness is necessary. Promoting continuous use of combined hormonal contraception and LARCs with maintained acceptability and increased satisfaction with bleeding patterns are possible ways forward in the effort to reduce the rates of unintended pregnancy.

Conclusion

Current use of contraception among Swedish women remains low at 62.4%, and the unmet need for contraception has increased to 17.2%. Method effectiveness and added health benefits of hormonal contraceptives should be emphasised during contraceptive counselling, and actions are needed to target groups with low use of effective contraception as well as reaching those who never actively seek contraception.

Author contributions

The study was initiated by HKK and KGD. HKK, KGD and NE participated in the design of the survey. The analysis of the results was performed by NE, TW and HKK. NE, TW, KGD and HKK have participated in manuscript writing.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the outstanding assistance of Staffan Jannesson Billing, Bayer Sweden AB, for administrating the execution of the e-survey, and Eva Pokkinen and Jessica Paulsson at Kantar SIFO, for excellent knowledge and assistance in designing the e-survey. We extend our special thanks to Christian Fiala, Austria, for providing us with the questions for the original survey in 2012.

Disclosure statement

Tove Wallström declares no conflicts of interest. Niklas Envall, Helena Kopp Kallner, and Kristina Gemzell Danielsson have received honorariums for giving lectures for Bayer. NE have received honorarium for expert opinions on contraception from Medsphere Corporation. HKK and KGD have participated in the national and international medical advisory boards for Bayer. KGD is a member of the standing international Women’s Health Academy supported by Bayer. HKK and KGD have participated in trials sponsored by Bayer as principal investigators. The survey was fully sponsored with an unrestricted grant from Bayer Sweden AB, but the entity had no influence on the content of the survey nor in the writing of the manuscript. The authors received no personal compensation for conducting the study nor manuscript writing. Outside the submitted work HKK and KGD receives honorariums for lectures on women’s health, contraception and fibroid care from: Actavis, Gedeon Richter Exeltis, Nordic Pharma, Natural Cycles, Mithra, Teva, Merck, Ferring, Consilient Health, Norgine, and KGD also from Campus Pharma,Vifor, Daisy and Obseva/Theramex. HKK provides expert opinion for: Evolan, Gedeon Richter, Exeltis, Merck, Teva, TV4 och Natural Cycles and is an investigator in trials sponsored by MSD, Mithra, Ethicon, Azanta and Gedeon Richter. HKK and KGD teach courses sponsored by Merck and MSD/Organon and Gedeon Richter.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bearak J, Popinchalk A, Ganatra B, et al. Unintended pregnancy and abortion by income, region, and the legal status of abortion: estimates from a comprehensive model for 1990-2019. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(9):e1152–e1161.

- Exelgyn. Abortion Statistics, Abortion rates per 1,000 women aged 15–49. 2018. [updated February 2020; cited 2021 December 7th]. Available from: https://abort-report.eu/europe/

- The National Board of Health and Welfare. Abortion statistics in Sweden 2020. Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen; 2021. Available from: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/statistik-och-data/statistik/statistikamnen/aborter/

- Winner B, Peipert JF, Zhao Q, et al. Effectiveness of long-acting reversible contraception. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(21):1998–2007.

- Rose SB, Lawton BA. Impact of long-acting reversible contraception on return for repeat abortion. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(1):37.e1–37.e6.

- Cameron ST, Glasier A, Chen ZE, et al. Effect of contraception provided at termination of pregnancy and incidence of subsequent termination of pregnancy. Bjog. 2012;119(9):1074–1080.

- Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare. Induced abortions in the Nordic countries 2019. Helsinki: Finnish Ministry of Social Affairs and Health 2021. Available from: https://www.julkari.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/141157/Aborter_i_Norden_2019.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Emtell Iwarsson K, Envall N, Bizjak I, et al. Increasing uptake of long-acting reversible contraception with structured contraceptive counselling: cluster randomised controlled trial (the LOWE trial). BJOG. 2021;128(9):1546–1554.

- Bitzer J, Gemzell-Danielsson K, Roumen F, et al. The CHOICE study: effect of counselling on the selection of combined hormonal contraceptive methods in 11 countries. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2012;17(1):65–78.

- Kopp Kallner H, Thunell L, Brynhildsen J, et al. Use of contraception and attitudes towards contraceptive use in Swedish Women - A Nationwide Survey. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0125990.

- Hellstrom A, Gemzell Danielsson K, Kopp Kallner H. Trends in use and attitudes towards contraception in Sweden: results of a nationwide survey. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2019;24(2):154–160.

- Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of Web surveys: the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). J Med Internet Res. 2004;6(3):e34.

- Fiala C, Schweiger P. Österreichischer Verhütungsreport 2019. 2012. September, 2012.

- Statistics Sweden. Statistikdatabasen 2021. [cited 2022 June 16th]. Available from: statistikdatabasen.scb.se

- Peipert JF, Madden T, Allsworth JE, et al. Preventing unintended pregnancies by providing no-cost contraception. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2012;120(6):1291–1297.

- Guttmacher Institute. Adolescent pregnancy and its outcomes across countries. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2015. Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/adolescent-pregnancy-and-its-outcomes-across-countries

- Rosenstock JR, Peipert JF, Madden T, et al. Continuation of reversible contraception in teenagers and young women. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(6):1298–1305.

- Kavanaugh ML, Pliskin E. Use of contraception among reproductive-aged women in the United States, 2014 and 2016. F S Rep. 2020;1(2):83–93.

- Hognert H, Skjeldestad FE, Gemzell-Danielsson K, et al. Ecological study on the use of hormonal contraception, abortions and births among teenagers in the Nordic countries. BMJ Open. 2018;8(10):e022473.

- Moreau C, Bohet A, Trussell J, et al. Estimates of unintended pregnancy rates over the last decade in France as a function of contraceptive behaviors. Contraception. 2014;89(4):314–321.

- Bajos N, Leridon H, Goulard H, et al. Contraception: from accessibility to efficiency. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(5):994–999.

- Envall N, Emtell Iwarsson K, Bizjak I, et al. Evaluation of satisfaction with a model of structured contraceptive counseling: results from the LOWE trial. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021;100(11):2044–2052.

- Emtell Iwarsson K, Larsson EC, Bizjak I, et al. Long-acting reversible contraception and satisfaction with structured contraceptive counselling among non-migrant, foreign-born migrant and second-generation migrant women: evidence from a cluster randomised controlled trial (the LOWE trial) in Sweden. BMJ Sex Reprod Health. 2022;48(2):128–136.

- Mazza D, Watson CJ, Taft A, et al. Increasing long-acting reversible contraceptives: the Australian Contraceptive ChOice pRoject (ACCORd) cluster randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222(4s):S921.e1–S921.e13.

- Taft A, Watson CJ, McCarthy E, et al. Sustainable and effective methods to increase long‐acting reversible contraception uptake from the ACCORd general practice trial. Aus NZ J of Public Health. 2022. DOI:10.1111/1753-6405.13242

- Dinger J, Minh TD, Buttmann N, et al. Effectiveness of oral contraceptive pills in a large U.S. cohort comparing progestogen and regimen. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(1):33–40.

- Damm T, Lamvu G, Carrillo J, et al. Continuous vs. cyclic combined hormonal contraceptives for treatment of dysmenorrhea: a systematic review. Contracept X. 2019;1:100002.

- Edelman A, Micks E, Gallo MF, et al. Continuous or extended cycle vs. cyclic use of combined hormonal contraceptives for contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;29(7):CD004695.