Abstract

Purpose

To investigate bleeding profile satisfaction and pain and ease of placement with levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD in routine clinical practice.

Methods

Women who independently chose levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD during routine counselling were invited to participate in this prospective, multinational, observational study. Patient-reported pain and clinician-reported ease of placement were assessed. Bleeding profile satisfaction was evaluated at 12 months/premature end of observation.

Results

Most participants (77.8%, n = 878/1129) rated levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD placement pain as ‘none’ or ‘mild’ and most clinicians (91.1%, n = 1029/1129) rated placement as ‘easy’. Pain was more often rated higher in nulliparous compared with parous (p < .0001) and younger (<26 years) compared with older participants (p < .0001), although 67.7% and 69.0% of nulliparous and younger participants respectively reported ‘none’ or ‘mild’ pain. Bleeding profile satisfaction at 12 months/end of observation was similar in parous (72.9%, n = 318/436) and nulliparous (69.6%, n = 314/451) participants. Most participants irrespective of age reported bleeding profile satisfaction, ranging from 67.8% (n = 206/304) for 18–25 years to 76.5% (n = 218/285) for >35 years.

Conclusion

We observed high bleeding profile satisfaction regardless of age or parity with levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD and confirmed that device placement is easy and associated with no more than mild pain in most cases in routine clinical practice. Real-world evidence from the Kyleena® Satisfaction Study in routine clinical practice shows high bleeding profile satisfaction with levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD regardless of age or parity. IUD placement was easy and associated with little to no pain for most women.

摘要

目的:探讨临床常规放置19.5mg左炔诺孕酮宫内节育器(IUD)时的出血情况、满意度、疼痛及便利性。

方法:本研究为前瞻性、多中心、观察性研究。评估患者报告的疼痛和临床医生报告的放置轻松度。在应用12个月或观察提前结束时评估出血情况满意度。

结果:大多数参与者(77.8%, n=878/1129)将放置19.5 mg左炔诺孕酮 IUD疼痛评为“无”或“轻度”, 大多数临床医生(91.1%, n=1029/1129)将放置难易程度评为“容易”。未生育过的女性的的疼痛程度高于生育过的女性(p <0 .0001)及更年轻的女性(p <0 .0001), 尽管67.7%和69.0%的未生育过的女性和较年轻的女性分别报告“没有”或“轻度”疼痛。观察12个月或者研究结束时, 生育过的女性(72.9%, n=318/436)和未生育过的女性(69.6%, n=314/451)的出血情况满意度相似。大多数参与者(不论年龄)报告对出血情况满意, 18-25岁出血满意情况为67.8% (n=206/304), 35岁以上满意程度为76.5% (n=218/285)。

结论:我们观察到, 无论年龄或者是否生育过, 19.5 mg左炔诺孕酮节育器的出血情况都有较高的满意度, 并证实在常规临床实践中, 大多数情况下放置节育器很容易, 并且与轻度疼痛无关。来自常规临床实践Kyleena®满意度研究的真实世界结果表明, 无论年龄或是否生育过, 19.5 mg的左炔诺孕酮IUD的出血情况都有很高的满意度。放置宫内节育器很容易, 对大多数女性来说几乎没有疼痛。

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier::

Introduction

Hormonal levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine devices (IUDs) are well-established forms of contraception associated with high contraceptive efficacy, safety and satisfaction rates in clinical trials [Citation1–5]. IUDs, along with other long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs), are thus often recommended as the first-line option for contraceptive choice in clinical guidelines [Citation6–8]. Despite this, IUDs are not used as frequently as other user-dependent forms of contraception, such as oral contraceptive pills or barrier methods [Citation9–12].

There are several barriers to intrauterine contraceptive use that exist among both clinicians and patients and result in this lower user rate. These include a lack of awareness or knowledge about IUDs that can lead to concerns and misconceptions from both clinicians and women about their use [Citation13–18]. The most common reason that women give for not selecting intrauterine contraception is fear regarding pain at placement [Citation19,Citation20]. The potential initial changes to the bleeding profile may also be a reason for the reluctance of some women to use a levonorgestrel IUD [Citation21–24], as bleeding can be more frequent and/or prolonged for the first 3 months of use [Citation1,Citation4,Citation25–27].

In addition, there is a common belief among clinicians that intrauterine contraception is not suitable for young or nulliparous women [Citation13–17]. This is mainly due to concerns regarding potential pain and difficulty with placement of the device in this population, as well as misperceptions about infections and subsequent negative impacts on fertility. Many clinicians prescribe oral contraceptives instead of LARCs and providers other than obstetricians/gynaecologists may be uncomfortable with the IUD placement procedure due to a lack of experience and/or training [Citation16,Citation17].

In comparison with the widely used levonorgestrel 52 mg IUD, the levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD has a smaller T-frame and lower dose (and thus lower systemic concentrations) of LNG, and is associated with greater irregularity in bleeding patterns and a lower frequency of amenorrhoea [Citation28–30]. The Kyleena® Satisfaction Study (KYSS, NCT03182140) explores the use of the levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD in routine clinical practice. Previously published data from KYSS provide an insight into overall user satisfaction with levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD, with high satisfaction and continuation rates reported irrespective of age, parity, prior contraceptive method or reason for choosing levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD [Citation31,Citation32]. Here, we report further data on user satisfaction with bleeding profile, in addition to participants’ rating of pain at placement, clinicians’ rating of ease of placement, and the safety profile of levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD.

Materials and methods

KYSS (clinical trial registration number: NCT03182140) was a prospective, multinational, single-arm, observational study. The design and methodology have been described in detail previously [Citation31,Citation32]. Briefly, this study recruited participants from Belgium, Canada, Germany, Mexico, Norway, Spain, Sweden and the USA between July 2017 and December 2018, with a 12-month follow-up. The selection of countries and country-specific sample sizes were determined according to feasibility of recruiting. In order to avoid over-representation of any particular region, sites could enrol a maximum of 20 participants each. Approval from the independent ethics committee/institutional review board was obtained for all participating centres (see details in Supplementary Table 1).

Women attended routine visits with their clinician at participating study centres for an informed discussion about contraception. These discussions were not prompted or scripted and clinicians thus provided their routine contraceptive counselling, after which the women could decide to use any contraceptive method. Women who chose to use levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD were subsequently informed about the study and invited to participate. Participants included in the study could be new users or have used any other contraceptive methods prior to inclusion and there were no age restrictions. Exclusion criteria for the study included contraindications for levonorgestrel IUDs, mental incapacity to consent and participation in other clinical trials with interventions outside routine clinical practice. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Baseline characteristics and demographics have been previously described; briefly, over half of this population were nulliparous (584, 51.9%) and the mean age (± standard deviation) was 30.4 ± 8.9 years [Citation31,Citation32].

All participants attended an end of the observation/final visit that occurred after 12 months or at premature discontinuation if the participant chose to have the device removed before 12 months. Most participants also attended a visit at 4–12 weeks after placement; however, the study centres in Norway and Sweden did not conduct this visit as it is not part of their routine care. Thus, data at the 4–12-week time point were unavailable for the participants from these two countries.

The safety analysis set was comprised of all 1129 participants who had a levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD placement attempt. The full analysis set comprised of the 1126 participants who had a successful placement attempt (placement was unsuccessful in three [0.3%] of the 1129 participants) [Citation31]. In total, 210 (18.6%) of the 1129 participants in the safety analysis set ended observation before the planned final 12-month visit [Citation26]. The main reasons for premature end of observation were loss to follow-up (105 participants, 9.3%), removal due to adverse events (62, 5.5%), and removal due to wish for pregnancy (11, 1.0%).

This study assessed user satisfaction with levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD, satisfaction with the bleeding profile during levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD use, ease of placement and pain at placement, and the safety profile of levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD. Satisfaction ratings were based on a five-item Likert scale: ‘very satisfied’, ‘somewhat satisfied’, ‘neither satisfied nor dissatisfied’, ‘dissatisfied’ and ‘very dissatisfied’. Pain at placement of levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD was reported by participants as ‘none’, ‘mild’, ‘moderate’ and ‘severe’. The ease of levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD placement was assessed by clinicians using the observed categories ‘easy’, ‘slightly difficult’ and ‘very difficult’.

Participants were asked to assess their menstrual cramps or pain since levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD placement at the 4–12-week follow-up visit and for the 3 months prior to the 12-month follow-up visit or premature discontinuation. Dysmenorrhoea was rated as ‘none’, ‘mild’, ‘moderate’ and ‘severe’. Similarly, participants were asked whether they had experienced any bleeding since levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD placement at the 4–12-week follow-up visit and whether they had experienced bleeding during the previous 3 months at the 12-month/premature end of observation visit.

The primary reason for end of observation/study discontinuation (including participant loss to follow-up) was recorded. Data on adverse events were reported spontaneously by the participants or their health care provider. Adverse events were categorised and summarised according to the assessed relationship to levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD and seriousness of the adverse event. An adverse event was considered to be treatment-emergent if it occurred from the day of the first placement attempt until the end of the observation period (regardless of severity or relation to levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD use). An adverse event was considered to be treatment-related if it was judged by the investigator to be related to levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD use. The incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events was summarised descriptively by Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) System Organ Class and MedDRA Preferred Term.

Statistical differences in main population characteristics were analysed post hoc by chi-squared test. The influence of potential prognostic factors on satisfaction with the bleeding profile were investigated by multiple logistic regression analysis. The inclusion of population characteristics into the multiple logistic regression models was decided upon based on the univariate association of each parameter obtained from chi-squared test/Fisher’s exact test for categorical parameters and one-way analysis of variance for continuous parameters (Supplementary Table 2). A p-value of p < .2 was used as a cut-off for inclusion (although age was additionally included as a parameter). Multiple logistic regression analyses were calculated with adjustment for between-country variability by inclusion of country as stratum in multiple logistic regression models. All analyses were performed using SAS® software, version 9.4 (SAS System for Windows, Release 9.4. Statistical Analysis Systems Institute, Cary, NC) and generic macros [Citation33].

Results

Pain and ease of levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD placement

We investigated the differences in the perception of pain reported by participants (in the safety analysis set) and ease of placement reported by clinicians. These differences were evaluated according to age and parity (). Most participants (77.8%, 95% confidence interval [CI] 72.2–83.6%, n = 878/1129) rated the pain as ‘none’ or ‘mild’. Pain was more often rated higher in nulliparous participants compared with parous participants, with 32.3% (n = 189/586) of nulliparous and 11.2% (n = 61/543) of parous participants rating pain as ‘moderate’ or ‘severe’ (p < .0001). In addition, pain was more often rated higher in younger participants compared with older participants, with 31.0% (n = 133/429) of those aged <26 years and 16.7% (n = 117/700) of those ≥26 years rating pain as ‘moderate’ or ‘severe’ (p < .0001).

Table 1. Ease of placement of levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD, as assessed by physicians, and pain at placement of levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD, as assessed by participants (SAF).

Overall, 91.1% of clinicians (95% CI, 89.3–92.7%, n = 1029/1129) rated levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD placement as ‘easy’ (). There was no statistically significant difference in difficulty of placement between nulliparous and parous participants, with clinicians rating placement as ‘slightly difficult’ or ‘difficult’ in 9.9% (n = 58/586) and 7.7% (n = 42/543), respectively (p = .20). Likewise, there was no statistically significant difference in difficulty of placement in participants aged <26 years compared with those ≥26 years, with clinicians rating placement as ‘slightly difficult’ or ‘difficult’ in 8.4% (n = 36/429) and 9.1% (n = 64/700), respectively (p = .66).

Satisfaction with bleeding profile

Significant differences in the proportions of participants satisfied with their bleeding profile were evident when the 12-month/end of observation outcomes were compared between countries (p = .0004) (, ). A lower proportion of participants in Scandinavian countries were satisfied compared with those from other participating countries. It should be noted, however, that data on satisfaction with bleeding profile were unavailable for 239 participants at 12 months/end of observation due to loss to follow-up or to lack of collection of bleeding profile satisfaction at the routine visit.

Figure 1. Satisfaction with bleeding profile during levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD use at 12 months/end of observation by (A) country, (B) age and (C) prior contraceptive method. Note: Percentages have been rounded to one decimal place and thus may not total 100.0% exactly. Subgroups with <15 participants (natural family planning [n = 11], implant [n = 7], injectables [n = 6], transdermal HC [n = 2] and back-up contraception [n = 1]) have been excluded. Full analysis set, N = 1126. Data unavailable for 239 participants at 12 months/end of observation due to participant loss to follow-up or data on bleeding profile satisfaction not being collected. Satisfaction with bleeding profile during levonorgestrel 19.5 mg use at 12 months/end of observation by country: p = 0.0004. HC: hormonal contraception; IUD: intrauterine device; LNG: levonorgestrel.

![Figure 1. Satisfaction with bleeding profile during levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD use at 12 months/end of observation by (A) country, (B) age and (C) prior contraceptive method. Note: Percentages have been rounded to one decimal place and thus may not total 100.0% exactly. Subgroups with <15 participants (natural family planning [n = 11], implant [n = 7], injectables [n = 6], transdermal HC [n = 2] and back-up contraception [n = 1]) have been excluded. Full analysis set, N = 1126. Data unavailable for 239 participants at 12 months/end of observation due to participant loss to follow-up or data on bleeding profile satisfaction not being collected. Satisfaction with bleeding profile during levonorgestrel 19.5 mg use at 12 months/end of observation by country: p = 0.0004. HC: hormonal contraception; IUD: intrauterine device; LNG: levonorgestrel.](/cms/asset/c156e822-efa8-425a-a44f-a6c7b931ae4a/iejc_a_2136939_f0001_c.jpg)

Table 2. Satisfaction with bleeding profile during levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD use at 12 months/end of observation by country.

The majority of participants in all age subgroups were ‘somewhat’ or ‘very’ satisfied with their bleeding profile at 12 months/end of observation (, ). The youngest (≤17 years) and the oldest (>35 years) age groups had the highest proportions of participants reporting being ‘somewhat’ or ‘very’ satisfied with their bleeding profiles.

Table 3. Satisfaction with bleeding profile during levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD use at 12 months/end of observation by age.

When 12-month/end of observation results for satisfaction with bleeding profile were compared by parity, rates of satisfaction were similar in parous and nulliparous participants: 72.9% (95% CI, 68.5–77.1%, n = 318/436) of parous participants and 69.6% (95% CI, 65.1–73.8%, n = 314/451) of nulliparous participants reported being ‘somewhat’ or ‘very’ satisfied.

There was variation in user satisfaction with bleeding profile when stratified by contraceptive method used in the 3 months prior to initiating levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD use (, ). Notably, prior users of levonorgestrel IUDs or copper IUDs reported higher rates of bleeding profile satisfaction than users of most other methods.

Table 4. Satisfaction with bleeding profile during levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD use at 12 months/end of observation by prior contraceptive method.

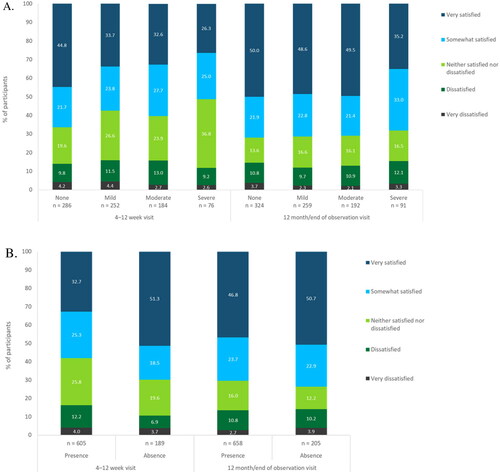

The severity of dysmenorrhoea correlated with participant satisfaction with bleeding profile: satisfaction was highest among those with no dysmenorrhoea (, ). Participants who rated their dysmenorrhoea as ‘severe’ were the least satisfied; however, even for this subgroup, 51.3% (95% CI, 39.6–63.0%, n = 39/76) reported being ‘somewhat’ or ‘very’ satisfied with their bleeding profile at the 4–12-week visit and 68.1% (95% CI, 57.5–77.5%, n = 62/91) reported this at the 12-month/end of observation visit. For all dysmenorrhoea severity subgroups, user satisfaction with the bleeding profile was higher at the 12-month/end of observation visit than at the 4–12-week visit. It should be noted that data on satisfaction with the bleeding profile at 4–12 weeks were unavailable for 305 participants because Sweden and Norway did not conduct a follow-up visit at this timepoint and due to loss to follow-up or lack of collection of bleeding profile satisfaction at the routine visit.

Figure 2. Satisfaction with bleeding profile at follow-up visits by (A) severity of dysmenorrhoea and (B) presence or absence of menstrual bleeding. Note: Percentages have been rounded to one decimal place and thus may not total 100.0% exactly. Full analysis set, N = 1126. Data unavailable for 305 participants at 4–12 weeks because Sweden and Norway did not conduct a follow-up visit at 4–12 weeks and due to participant loss to follow-up or data on bleeding profile satisfaction not being collected. Data unavailable for 239 participants at 12 months/end of observation due to participant loss to follow-up or data on bleeding profile satisfaction not being collected.

Table 5. Satisfaction with the menstrual bleeding profile at follow-up visits by severity of dysmenorrhoea.

Additionally, the absence of bleeding correlated with user satisfaction with bleeding profile. Those who reported an absence of bleeding had higher satisfaction rates than those who reported the presence of bleeding (, ). The difference between these two subgroups was larger at the 4–12-week visit than at the 12-month/end of observation visit. At the 12-month/end of observation visit, satisfaction had increased for both subgroups, and satisfaction for those reporting the presence of bleeding was almost as high as for those reporting absence of bleeding.

Table 6. Satisfaction with the menstrual bleeding profile at follow-up visits by presence or absence of menstrual bleeding.

Adverse events related to levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD use

summarises the TEAEs considered to be related to levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD use. The most common categories of levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD-related TEAEs were reproductive system and breast disorders (7.9%; n = 89/1129) and gastrointestinal disorders (2.6%; n = 29/1129). Of the reproductive system and breast disorders, vaginal haemorrhage was the most frequently reported levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD-related TEAE, reported in 21 (1.9%) participants, followed by lower abdominal pain in 16 (1.4%) participants. All other preferred term levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD-related TEAEs, including dysmenorrhoea, ovarian cysts and acne, were reported in ≤1.0% of participants.

Table 7. Levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD-related treatment-emergent adverse events occurring in >5 participants (SAF).

Discussion

Our data show that the majority of participants in this real-world study were ‘somewhat’ or ‘very’ satisfied with their bleeding profile during levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD use at 12 months/end of observation, regardless of parity, age or prior contraceptive method. An increase in bleeding profile satisfaction from the 4–12-week follow-up visit to the visit at 12 months/end of observation was observed when satisfaction rates were stratified by dysmenorrhoea severity and by presence/absence of bleeding. It is important to note that the 12-month/end of observation visit included those who discontinued prematurely and that those who discontinued prematurely were more likely to be less satisfied.

We report that levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD placement was easy and associated with little to no pain in most participants. Despite a higher rate of moderate-to-severe pain being reported in nulliparous or younger (<26 years) participants, the vast majority (almost 70%) of nulliparous and young participants experienced no or mild pain at placement. Additionally, we found that levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD-related TEAEs (including acne, ovarian cysts and those associated with bleeding, such as vaginal haemorrhage and dysmenorrhoea) were reported in few study participants.

Our real-world evidence reflects data from clinical trials showing that >70% of participants using levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD were ‘very satisfied’ or ‘somewhat satisfied’ with their bleeding profile across all age and parity subgroups [Citation3]. Furthermore, we confirm findings from previous clinical trials that placement of levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD is generally easy and associated with no to mild pain for most women [Citation2,Citation3]. These studies reported that the placement pain is substantially lower for levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD than for levonorgestrel 52 mg IUD [Citation3]. We show in this manuscript that the results from prior studies gathered in the strict environment of a clinical trial can be replicated in routine practice, which better emulates the diversity of patients, providers, health care systems and settings. This is highly encouraging and further supports clinical guidelines, which already approve of the routine use of levonorgestrel IUDs in nulliparous and/or young women [Citation8,Citation12,Citation34–36]. Pain regarding placement is a common concern and barrier to IUD use among both clinicians and women, particularly for young or nulliparous women [Citation13–19]. Our findings of low placement pain and high bleeding profile satisfaction suggest that levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD may therefore be a more suitable option for many women than levonorgestrel 52 mg IUD.

The safety profile of levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD has been similarly demonstrated previously in clinical trials, as well as in routine clinical practice [Citation1–4,Citation31]. Here our real-world evidence confirms low incidences of TEAEs considered to be related to levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD use. The incidences of levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD-related TEAEs were lower in this routine clinical practice study than incidences reported in clinical trials [Citation4]. This is to be expected because our observational study relied on spontaneous reporting from the patient and/or clinician rather than the rigorous follow-up and questioning in Phase 2 and 3 clinical trials.

We previously reported that levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD is well tolerated and associated with high overall user satisfaction and continuation rates irrespective of age, parity, prior contraceptive method or reason for initiating levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD use [Citation26]. However, overall satisfaction with levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD differed significantly between countries, with relatively lower proportions of participants from Norway and Sweden being ‘very satisfied’ [Citation31]. This observation was mirrored here when evaluating satisfaction with the bleeding profile during levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD use. It is not clear why the disparities in user satisfaction with the bleeding profile per country occurred; we could not exclude potential sources of bias, such as population variances and differences in routine counselling, which may influence satisfaction with bleeding profiles as well as overall satisfaction [Citation37,Citation38].

The longer duration of experience for Scandinavian countries with hormonal IUDs (specifically the levonorgestrel 52 mg IUD) may be a potential reason for the lower user satisfaction with their bleeding profile. If Scandinavian participants are familiar with levonorgestrel 52 mg IUD, they may be less tolerant of the slightly higher number of bleeding/spotting days with levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD use [Citation2,Citation26,Citation39].

A limitation of our study is that data on satisfaction with the bleeding profile were not available for all 1126 participants in the full analysis set. A major reason for this was participant loss to follow-up. As this was a study conducted in routine clinical practice, loss to follow-up was higher than rates observed in clinical trials. In our study, 210 (18.6%) of the 1129 participants in the safety analysis set ended observation before the planned final 12-month visit [Citation31]. Of these, half (105) were due to loss to follow-up rather than to discontinuation. Furthermore, data on bleeding profile satisfaction were not collected for all participants. Whereas clinical trials have rigorous data collection, the format of this observational study meant that some questions on bleeding profile satisfaction were neglected at the follow-up visits. In addition, data from the 4–12-week visit were unavailable for participants from Norway and Sweden as these countries do not conduct a routine follow-up visit at this time point. Therefore, data from the 4–12-week visit and user satisfaction trends over time should be interpreted with caution. Participants in Norway and Sweden were less satisfied with their bleeding profiles during levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD use and we recognise that this missing data may have influenced the bleeding satisfaction results from the 4–12-week follow-up visit and the user satisfaction trends over time.

Another limitation of our study is that some subgroups had a relatively small number of participants (e.g., the sample size for Mexico in comparison to the other countries, the ≤17-year age category, and several subgroups in the analyses on bleeding profile satisfaction stratified by prior methods of contraception). This means that there are too few participants to be certain of any conclusions drawn regarding these small subgroups.

Finally, we did not inquire about the number of deliveries, timing of the most recent delivery, or prior method of delivery (caesarean section versus vaginal) for parous participants. We recognise that these factors may impact IUD placement ease and pain, as well as the satisfaction with the bleeding profile during levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD use.

Conclusion

Most participants regardless of age or parity in this real-world study experienced no or mild pain at placement of levonorgestrel 19.5 mg IUD, and placement was reported as easy by the vast majority of clinicians. While bleeding changes are common with levonorgestrel IUDs, most participants in KYSS were satisfied with their bleeding profile independent of parity, age and prior contraceptive method.

For women or clinicians with concerns regarding IUD placement and bleeding profile changes (particularly in young or nulliparous women), these findings should provide reassurance and encourage the use of levonorgestrel IUDs.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (43 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the investigators for their participation and continued commitment to the study. The authors would also like to acknowledge funding from Bayer AG, Berlin, Germany, and to acknowledge Highfield, Oxford, UK, for providing medical writing assistance with funding from Bayer AG.

Disclosure statement

Gilbert Donders has been a member of a medical advisory board for Bayer Belgium since 2010, and his research centre has received fees for lectures and research from Bayer, Gedeon Richter, Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD), Medinova and Mycovia. Helena Kopp Kallner has received honoraria for lectures from Actavis, Bayer, Exeltis, Gedeon Richter, Merck, Mithra, Natural Cycles, Nordic Pharma and Teva, and teaches courses sponsored by Bayer, Merck and MSD; she has also provided expert opinion for Bayer, Evolan, Exeltis, Gedeon Richter, Merck, Natural Cycles, Teva and TV4, and is an investigator in trials sponsored by Bayer, Gedeon Richter, Mithra and MSD. Brian Hauck is on medical advisory boards for Allergan, Bayer, Merck, Pfizer and Searchlight. Anja Bauerfeind is a full-time employee of ZEG Berlin/Cerner Enviza, Berlin, Germany. Ann-Kathrin Frenz and Michal Zvolanek are full-time employees of Bayer AG, Berlin/Wuppertal, Germany. Dale Stovall has received honoraria from Bayer for educational lectures.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Nelson AL, Apter D, Hauck B, et al. Two low-dose levonorgestrel intrauterine contraceptive systems: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(6):1205–1213.

- Gemzell-Danielsson K, Schellschmidt I, Apter D. A randomized, phase II study describing the efficacy, bleeding profile, and safety of two low-dose levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine contraceptive systems and Mirena. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(3):616–622 e1-3.

- Gemzell-Danielsson K, Apter D, Hauck B, et al. The effect of age, parity and body mass index on the efficacy, safety, placement and user satisfaction associated with two low-dose levonorgestrel intrauterine contraceptive systems: subgroup analyses of data from a phase III trial. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0135309.

- Gemzell-Danielsson K, Apter D, Dermout S, et al. Evaluation of a new, low-dose levonorgestrel intrauterine contraceptive system over 5 years of use. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;210:22–28.

- Gemzell-Danielsson K, Kubba A, Caetano C, et al. Thirty years of mirena: a story of innovation and change in women’s healthcare. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021;100(4):614–618.

- World Health Organization. Family planning: a hand book for providers, Third Edition. 2018; [cited 2022 May 9]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/260156.

- Temple-Smith M, Sanci L. LARCs as first-line contraception – hat can general practitioners advise young women? Aust Fam Physician. 2017;46(10):710–715.

- Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology. Long-acting reversible contraception work group; eve espey, Lisa Hofler. Long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Practice bulletin no. 186. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(5):e251–e269.

- Joshi R, Khadilkar S, Patel M. Global trends in use of long-acting reversible and permanent methods of contraception: seeking a balance. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015;131(Suppl 1):S60–S63.

- Black A, Guilbert E, Costescu D, et al. Canadian Contraception Consensus (part 3 of 4): chapter 7 – intrauterine contraception. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2016;38(2):182–222.

- Agostini A, Godard C, Laurendeau C, et al. Two year continuation rates of contraceptive methods in France: a cohort study from the French national health insurance database. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2018;23(6):421–426.

- Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. FSRH clinical guideline: intrauterine contraception (April 2015, amended September). 2019; [cited 2021 Dec]. Available from: https://www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/documents/ceuguidanceintrauterinecontraception.

- Buhling KJ, Hauck B, Dermout S, et al. Understanding the barriers and myths limiting the use of intrauterine contraception in nulliparous women: results of a survey of European/Canadian healthcare providers. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;183:146–154.

- Potter J, Rubin SE, Sherman P. Fear of intrauterine contraception among adolescents in New York City. Contraception. 2014;89(5):446–450.

- Brima N, Akintomide H, Iguyovwe V, et al. A comparison of the expected and actual pain experienced by women during insertion of an intrauterine contraceptive device. Open Access J Contracept. 2015;6:21–26.

- McNicholas C, Madden T. Meeting the contraceptive needs of a community: increasing access to long-acting reversible contraception. Mo Med. 2017;114(3):163–167.

- Caetano C, Bliekendaal S, Engler Y, et al. From awareness to usage of long-acting reversible contraceptives: results of a large European survey. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2020;151(3):366–376.

- Laporte M, Peloggia A, Marcelino AC, et al. Perspectives of health care providers regarding the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2022;27(3):208–211.

- Asker C, Stokes-Lampard H, Beavan J, et al. What is it about intrauterine devices that women find unacceptable? Factors that make women non-users: a qualitative study. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2006;32(2):89–94.

- Gemzell-Danielsson K, Jensen JT, Monteiro I, et al. Interventions for the prevention of pain associated with the placement of intrauterine contraceptives: an updated review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2019;98(12):1500–1513.

- Dickerson LM, Diaz VA, Jordon J, et al. Satisfaction, early removal, and side effects associated with long acting reversible contraception. Fam Med. 2013;45(10):701–707.

- Weisberg E, Bateson D, McGeechan K, et al. A three year comparative study of continuation rates, bleeding patterns and satisfaction in Australian women using a subdermal contraceptive implant or progestogen releasing intrauterine system. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2014;19(1):5–14.

- Bahamondes L, Brache V, Meirik O, et al. A 3-year multicentre randomized controlled trial of etonogestrel- and levonorgestrel-releasing contraceptive implants, with non-randomized matched copper-intrauterine device controls. Hum Reprod. 2015;30(11):2527–2538.

- Diedrich JT, Desai S, Zhao Q, et al. Association of short-term bleeding and cramping patterns with long acting reversible contraceptive method satisfaction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(1):50.e1–e8.

- Goldthwaite LM, Creinin MD. Comparing bleeding patterns for the levonorgestrel 52 mg, 19.5 mg, and 13.5 mg intrauterine systems. Contraception. 2019;100(2):128–131.

- Beckert V, Ahlers C, Frenz AK, et al. Bleeding patterns with the 19.5 mg LNG-IUS, with special focus on the first year of use: implications for counselling. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2019;24(4):251–259.

- Frenz AK, Ahlers C, Beckert V, et al. Predicting menstrual bleeding patterns with levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine systems. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2021;26(1):48–57.

- Bayer AG. Kyleena Product Monograph. 2021; [cited 2022 Sept 11]. Available from: https://www.bayer.com/sites/default/files/2020-11/kyleena-pm-en.pdf.

- Hofmann BM, Apter D, Bitzer J, et al. Comparative pharmacokinetic analysis of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine systems and levonorgestrel-containing contraceptives with oral or subdermal administration route. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2020;25(6):417–426.

- Bastianelli C, Farris M, Rosato E, et al. The use of different doses levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS): real-world data from a multicenter Italian study. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2022;27(1):16–22.

- Stovall DW, Aqua K, Römer T, et al. Satisfaction and continuation with LNG-IUS 12: findings from the real-world Kyleena® satisfaction study. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2021;26(6):462–472.

- Beckert V, Aqua K, Bechtel C, et al. Insertion experience of women and health care professionals in the Kyleena® Satisfaction study. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2020;25(3):182–189.

- Liu Y, Nickleach DC, Zhang C, et al. Carrying out streamlined routine data analyses with reports for observational studies: introduction to a series of generic SAS® macros. F1000Res. 2018;7:1955.

- Lohr PA, Lyus R, Prager S. Use of intrauterine devices in nulliparous women. Contraception. 2017;95(6):529–537.

- Hardeman J, Weiss BD. Intrauterine devices: an update. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89(6):445–450.

- ACOG Committee Opinion no. 735: adolescents and long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(5):e130–e139.

- Ali MM, Cleland J, Shah IH. Causes and consequences of contraceptive discontinuation: evidence from 60 demographic and health surveys. 2012; [cited 2020 Jul 10]. Available from: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/family_planning/9789241504058/en.

- Modesto W, Bahamondes MV, Bahamondes L. A randomized clinical trial of the effect of intensive versus non-intensive counselling on discontinuation rates due to bleeding disturbances of three long-acting reversible contraceptives. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(7):1393–1399.

- Hellström A, Gemzell Danielsson K, Kopp Kallner H. Trends in use and attitudes towards contraception in Sweden: results of a nationwide survey. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2019;24(2):154–160.