Abstract

The paper explores the use of country-related stereotypes associated with Italian identity in the social media communication of 21 Italian fashion brands on Instagram. Focusing on the concept of “made in Italy”, the research employs image content analysis to identify how the selected sample of brands communicates Italian identity globally. The theoretical framework emphasizes the importance of the Country of Origin (COO) concept, indicating that “made in Italy” extends beyond a manufacturing label to encompass cultural, historical, and esthetic dimensions. The analysis reveals Italian fashion brands’ deliberate use of stereotypes, iconic objects, and cultural references to shape and reinforce Italian identity in their digital communication. It highlights the intertwining of these elements, contributing to a multifaceted narrative that extends beyond product promotion. Moreover, it underscores the role of social media, particularly Instagram, in enabling brands to project their Italian identity globally, perpetuating esthetics associated with the concept of “dolce vita”. The study emphasizes the importance of holistic brand communication and the powerful role of Instagram in shaping and reinforcing the global image of “made in Italy”. It also offers insights on utilizing stereotypes and cultural symbols to enhance brand identity, aligning with perceptions associated with Italian cultureFootnote1.

Introduction

The “made in” label is crucial in fashion consumption, especially within the realm of luxury. In the case of nations like Italy, the country of origin typically assures consumers of their long history of craftsmanship and the quality of the products they produce (Rech, Noris, and Sabatini Citation2023). However, the perception of “made in” is often intertwined with preexisting cultural imaginaries (Carini and Mazzucotelli Salice Citation2023), and with the idea of national stereotypes linked with the concept of italianness (Noris and Cantoni Citation2024).

With the advent of digital technologies, particularly through social media, Italian companies have significantly expanded their reach and have started to communicate globally (Noris and Cantoni Citation2022). By showcasing their expertise on international social media platforms, companies in the Italian textile and footwear sector contribute to constructing an Italian identity, perpetuating esthetics reminiscent of the “dolce vita” and embracing a series of stereotypes associated with Italian culture (Adamoli Citation2017: 61). These narratives often serve as responses to market inquiries outside of Italy, projecting an image of Italian culture with an autonomous capacity to use stereotypes or overpowering cultural heritage to create competitive advantages (Balicco Citation2015; Paris Citation2020).

This research, through an image content analysis of 21 brands headquartered in Italy, aims to investigate how Italian fashion brands utilize stereotypes related to Italian identity in their social media communication, particularly on Instagram. Additionally, the study identifies which stereotypes are most frequently employed, how companies communicate their know-how and esthetics, and how they strategically leverage cultural imaginaries to form part of an effective communication strategy.

Research context

Country of origin and “made in”

The Country of Origin (COO) concept, tracing its roots to the aftermath of the First World War, originally denoted the “made in” label to products from defeated nations as a warning signal (Cecere, Izzo, and Terraferma Citation2022; Munjal Citation2014). The economic exploration of COO started in Citation1965 (Diamantopoulos and Zeugner-Roth Citation2010; Herz Citation2013), with Schooler’s (Citation1965) empirical demonstration that identical products can be perceived differently based on their country of origin (Cecere, Izzo, and Terraferma Citation2022). In today’s globalized landscape, where consumer choices span the globe, COO holds considerable significance (Al-Sulaiti and Baker Citation1998; Usunier Citation2006). It encompasses not only the image, reputation, and stereotypes associated with a country’s products but also the set of beliefs consumers hold about the countries themselves (Cecere, Izzo, and Terraferma Citation2022; Kotler and Gertner Citation2002; Nagashima Citation1970; Roth and Romeo Citation1992; Segre Reinach Citation2015; Strutton, True, and Rody Citation1995). The COO construct manifests in consumers’ evaluations of the intrinsic qualities of a specific product based on its origin, shaping their perceptions and attitudes toward associated brands (Cecere, Izzo, and Terraferma Citation2022: 28). Moreover, the concept of the “label of origin” does not adhere to a rigid framework; instead, it possesses the adaptability to align with contemporary trends and consumer demands. Nonetheless, consumers have acquired the ability to discern a distinct identity, such as that embodied by the “made in Italy” label, which emerges from the creative process and it is intertwined with specific stylistic elements, commercial interactions, as well as cultural, economic, and historical contexts (Segre Reinach Citation2015).

COO is considered an extrinsic feature, alongside the brand, providing additional assurance in purchases of unfamiliar products (Cecere, Izzo, and Terraferma Citation2022; Josiassen and Harzing Citation2008). The COO concept deeply intertwines with the idea of “made in”, which encompasses several meanings, among them: the guarantee of craftsmanship and quality and the trust in manufacturing status (Pavlek Citation2015).

Examining the perception of “made in” Italy, De Nisco and Mainolfi (Citation2016) underscore the foreign perspective associating Italy and its products with the cultural heritage of the Italian country brand. This perception is intricately tied to cultural attributes, stereotypes, and product categories such as food, leather goods, design, and home furnishings (Giumelli, Citation2016). As reported by Giumelli, a KPMG (2011) study reveals that foreigners commonly link the label “made in Italy” with values like appearance, beauty, luxury, well-being, passion, and creativity, often overlooking technological and innovative aspects. KPMG, in collaboration with Google, revealed that there has been a steady increase in online searches for “made in Italy” from 2006 to 2010. The most sought-after terms included cars, fashion, tourism, and food. Google even recognized this heightened interest by establishing a dedicated portalFootnote2—an unprecedented global initiative—to better showcase and promote these Italian “excellences” (in Giumelli, Citation2016). Moreover, more recently, Amazon (in Giumelli, "Amazon: Made in Italy re delle ricerche web", La Repubblica, October 5, 2015. Accessed via: https://www.repubblica.it/economia/2015/10/05/news/amazon_tasse_made_in_italy-124378294/) also acknowledged the significance of “made in Italy” by stating that the term was the most sought-after term in their search, further emphasizing the growing global interest in Italian products (in Giumelli, Citation2016).

In fashion, place of origin and “made in” serve as a competitive advantage, especially if a brand’s country or region is recognized for specific expertise (Colombi Citation2020) and the values linked to the country of origin are embodied in a country’s image and origin effect, as seen in luxury labels which emphasize “made in Italy”, “made in France”, “made in Switzerland”, to represent local industry heritage and expertise (Gravari-Barbas and Sabatini Citation2023; Paulicelli, Manlow, and Wissinger Citation2021; Rech, Noris, and Sabatini Citation2023).

“Made in” in the Italian fashion

Fashion is a pivotal creative sector and industry for Italy, acknowledged not solely for its economic impact but also esteemed as a cultural phenomenon enriched with historical and anthropological dimensions (Segre Reinach Citation2015). In Italian fashion, the concept of “made in Italy” transcends its static label, portraying itself as an open system characterized by adaptability and vitality. The concept includes the Italian industry’s resilience and capacity to evolve while upholding a distinctive identity, surpassing mere product development to embrace conceptual evolution and strategic positioning. Segre Reinach (Citation2015) “made in Italy” perspective advocates for a comprehensive analysis of the nuanced meaning of the concept considering the intricate interplay between cultural, economic, and historical roots, thereby surpassing conventional assessments based solely on commercial success. The perception of “made in Italy” is intricately woven with preexisting cultural imaginaries, influencing how Italian brands communicate their italianness on a global stage. Crane and Bovone (Citation2006) state that through substantial investments in advertising, Italian fashion brands have effectively linked specific values to their products, which consumers have globally embraced.

Brands construct an Italian identity by perpetuating esthetics reminiscent of “la dolce vita” and leverage stereotypes and cultural heritage to their advantage (Balicco Citation2015; Krim Citation2023; Paris Citation2020). The phenomenon of reviving those concepts emerged especially during moments of social uncertainty when the paradigm of nostalgia reached its peak (Morreale Citation2009). Characters, objects, songs, or even iconic brands that have left an imprint on the collective imagination reappear as essential reference points for “disoriented and hypercritical consumers” (Morace Citation2004: 99).

To explore such stereotypes further, Studia Imagologica (Beller and Leerssen Citation2007) elucidates the emergence and impact of national stereotypes, revealing their connections to historical, ideological, and cultural circumstances. Five dimensions that characterize Italianness are presented (i) magnificent ruins and ancient statuary; (ii) religion; (iii) Italians’ passion for fine arts, encompassing renowned painters, architects, and musical virtuosos; (iv) iconic landscapes associated with modern tourism; and (v) the composite image of the Italian individual, encapsulating diverse qualities and stereotypes, ranging from genius to laziness (Bollati Citation1972). Such stereotypes, as Vincenzo Gioberti (Citation1844) suggested in the XIX century, portray the Italian people as a desire rather than a factual reality, contributing to the complex narrative surrounding “made in Italy” in the realm of fashion. Expanding upon the stereotypes delineating Italianness and the Italian national stereotype as proposed by Beller (Citation2007), Noris and Cantoni (Citation2024) in a research related to the use of national stereotypes within fashion movies introduce two additional dimensions: (i) the notion of perfection illustrated by the emphasis on flawless experiences and settings; and (ii) the indeterminacy of time, portrayed through the belief that in the pursuit of perfection, time becomes an inconsequential factor for Italians.

Research gap

From a scientific viewpoint analyzing “made in Italy” is challenging in terms of production operations and social meanings. The sectors of Made in Italy—defined by Fortis and Carminati (Citation2016: 193) as the 4 F’s of Italian excellence: Fashion and cosmetics; Food and wine; Furniture and ceramic tiles; Fabricated metal products, machinery, and transport equipment are often studied in isolation, missing the synergies between them.

Despite differing products, these sectors share commonalities, especially in expert human capital (Brusco and Paba Citation2014). Few recent studies have started to examine how Italian fashion integrates communication strategies (Brambilla et al. Citation2023; Noris and Cantoni Citation2024) through the Country Image (CI) - defined as the overall image shaped by stereotypes and generalized opinions about a specific country (Bursi et al. Citation2012: 48) – and aligned with other national production sectors and clusters. Such studies often focus on consumer perspectives based on Country of Origin (COO) without detailing the unique elements of Italian brand communication, particularly on social media (Pucci et al. Citation2017; Cappelli et al. Citation2019).

This study aims therefore to fill this research gap in understanding the cultural and social-historical elements that brands use to broadcast their identity on social media.

Methodology

This study aims to answer the following two research questions:

To what extent do Italian fashion brands employ stereotypes associated with Italian identity in their social media communication, specifically on Instagram?

How do Italian fashion brands strategically utilize cultural imaginaries as part of their communication strategy on Instagram?

To address them, a visual content analysis of 498 Instagram posts was conducted using template analysis. This method, as outlined by King (Citation2004), is highly flexible, with minimal specified procedures, enabling researchers to customize it according to their research requirements.

Template analysis, as described by King (Citation2004), facilitates the generation of a list of codes or “templates” representing identified themes in the text. The reliability of coding is not assigned a specific value; instead, elements such as the researcher’s introspectiveness, consideration of different perspectives, and the richness of the description produced are deemed crucial. In this method, the researcher compiles a list of codes (a “template”) representing themes identified in the textual data. While some themes are predefined, they are adjusted based on the researchers’ reading and interpretation of the texts.

A priori codes were identified through the literature of Beller and Leerssen (Citation2007) and Noris and Cantoni (Citation2024), providing insights into how stereotypes emerge and about factors influencing them, whether historical, ideological, cultural, literary, or discursive. Instagram has been chosen to examine how Italian brands communicate their “Italianness” and the concept of “made in” since it is a very popular global social media, widely utilized by fashion brands (Dewan Citation2021; Noris and Cantoni Citation2021a; Noris and Cantoni Citation2021b). Two experienced coders analyzed the images manually from April 13 to June 30 2023. The manual analysis was supported by AI and OCR tools, such as Google Lens, when for research purposes this was needed.

Italian brands were selected from multiple sources and references, encompassing diverse international brand rankingsFootnote3 such as “The Top 30 Most Valuable Italian Brands 2022” (Kantar Citation2022a) and “The Kantar BrandZ Top 10 Italian Luxury Brands 2022”(Kantar Citation2022b) from the Kantar BrandZ Most Valuable Italian Brands report. Additionally, selections were made based on “Q3 2022 Hottest Brands” from The Lyst Index (Citation2022), “Which brands dominated social media during Milan Fashion Week (2023)” from Nss Magazine (Citation2023), and “Top 100, FY2021” from the Global Powers of Luxury Goods report published by Deloitte (Citationn.d.).

A final list of the most popular and significant brands was compiled, excluding the beauty and eyewear sectors. The final list comprised 20 brands, including Bottega Veneta, which however has been excluded from the analysis due to its absence from social media. To further strengthen the sample identified through nonacademic ranking methods, two additional brands (Caruso and Velasca Milano) were purposely added. The researchers deemed these brands suitable for the research goal based on their previous investigations and expertise, resulting in a final sample of 21 labels.

As a first step, Instagram posts of the selected brands were collected within a specified timeframe March 12 to April 12, 2023. It has been decided to analyze only images. Videos, posts related to events, reels and other content were excluded from this research. Furthermore, only the first image has been considered for posts containing multiple images (e.g. in the carousel).

For each analyzed post, the following content elements were collected and archived: image, caption, hashtags, tags, and location (when available). The preliminary analysis of the visual content of the selected images was conducted, gathering initial data based on existing literature and complementing it with online research and Google Lens. In a subsequent phase, the purely visual analysis of the images was expanded by considering all other qualitative contents such as captions, hashtags, tags, and location (when available).

Results

Results are presented along the two research questions.

Research Question 1:

To what extent do Italian fashion brands employ stereotypes associated with Italian identity in their social media communication, specifically on Instagram?

A preliminary analysis of the visual content of 498 images identified how frequently italianness was referred to; further on, prevalent themes have been analyzed.

Below is the list of brands and the number of analyzed posts, as well as the number of post related to COO and CI both in the picture and both in the text, hashtag and tags ():

Table 1. The list of brands and the number of posts analyzed.

Specifically, 92 posts (18.47%) reference both COO and CI, and 31 images (6.2%) explicitly reference Italian identity, categorized into four main templates (). It is clear that not all brands distinctly highlight their Italian heritage. Therefore, while the communication strategies examined here are just one of many possible approaches, they effectively convey the diverse messages each brand seeks to communicate. Although this investigation does not quantitatively assess references to Italian identity within individual brands, the findings confirm that utilizing Country Image (CI) is part of the strategies employed by fashion brands.

Table 2. List of identified templates.

Research Question 2:

How do Italian fashion brands strategically utilize cultural imaginaries as part of their communication strategy on Instagram?

The analysis highlights how Italian fashion brands leverage cultural heritage and craftsmanship, emphasizing iconic objects to convey a narrative of quality, tradition, and the Italian lifestyle. It identifies a recurring theme of slow living, rural esthetics, and luxury tourism in the visual communication of Italian fashion brands to reinforce a narrative of timeless elegance and craftsmanship. It emphasizes skills related to craftsmanship rooted in the traditions of workshops and regional artisanship, capable of transcending geographical boundaries and spanning various productive sectors. Moreover, the research reveals how Italian food, materials and decorations, as well as the idea of perfection emerge as powerful tools for brand communication, with fashion brands using related stereotypes to align with the rich gastronomic, craftsman and textile heritage of Italy. The analysis of Instagram posts results in the following four templates:

Inspirational Locations and the Idea of Indeterminacy of Time

Materials and Decorations and the Idea of Perfection

Culinary Delights

Iconic Objects

Other themes have not been grouped either because they were numerically insignificant orbelong to excluded product categories; however, if one had to expand the sample, they might be considered. In this direction, the category related to the “composite image of the Italian individual” (Beller and Leerssen Citation2007), which could be found in the use of local film celebrities as in promotion of Italian fashion brands, observed only in the case of the Italian actor Alessandro Gassman for Bulgari, was not considered for this analysis.

Each theme is presented in detail below:

Inspirational locations and the idea of indeterminacy of time

Locations play a role in Italy’s communicative apparatus and the concept of being Italian (Gravari-Barbas and Sabatini Citation2023). Focusing on tourist or historical-artistic destinations, the analyzed fashion brands emphasize the stereotype of slow and timelessness, indeterminacy of time, long vacations, and rural living.

As observed in one of the analyzed images posted by Furla, bags are depicted amidst water and an olive tree, accompanied by the caption “Pastel colors and elegance. Enjoy the timeless Italian savoir-faire with Furla Genesi”Footnote4.

The notion of time, as illustrated in the quote from Furla, is a common leitmotif that fashion houses utilize in reference to nostalgic elements where time and place hold significant symbolic value. Merlo and Perugini (Citation2015) explain that brands often use the concept of nostalgia to evoke values of high-quality craftsmanship and timeless prestige, thereby invoking a sense of a simpler, more reassuring past. Noris and Cantoni (Citation2024) further discuss this leitmotif by adding the notion of indeterminacy of time, which refers to the absence of specific temporal references. This aspect is mainly associated with the idea of timelessness, suggesting a detachment from conventional notions of time typical of Western countries. Despite emphasizing the correlation between locations related to rural society and the historical craftsmanship of Italy, including textile activities, the historian Daniela Calanca (Citation2002: 74) suggests that this idea of the “indeterminate” time contrasts with the fashion industry’s adherence to precise timing and rapid transformations, leading to a narrative of romanticized time detached from industrial conventions (Evans and Vaccari Citation2019). Merlo and Perugini (Citation2015) adds that consumers often idealize the past as a perfect society, suggesting that previous eras were superior to the present, paving the way for nostalgic branding, which attracts consumers by projecting an authentic aura of trustworthiness and genuineness, underpinned by craftsmanship and expertise.

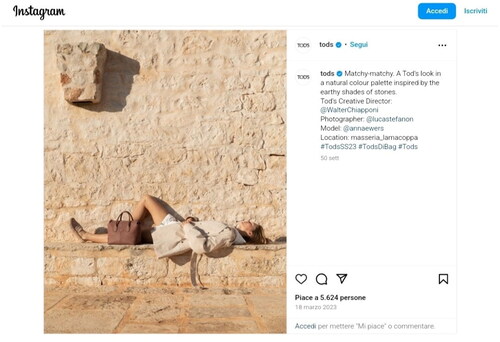

Puglia (Monopoli and the farmhouses – the so-called “masserie”), Sicily, and the Ligurian Riviera are the most prominent locations that were found in the analysis.

Ornella Cirillo (Citation2021) highlights the significance of short films dedicated to leisure time in promoting Italian tourist destinations. These films frequently employ stereotypes to endorse a lifestyle centered around well-being (Cirillo Citation2021). This is particularly evident in the D&G campaign, where a model is depicted standing near the port of Monopoli, accompanied by an unequivocal caption: “The longing for warmer days, friendship, and play captured at sunset, in the south of Italy” ().

Image 1 @dolcegabbana via Instagram. April 11 2023. Accessed via: https://www.instagram.com/p/Cq5ZHDLu2s-/.

Since the 19th century until the present day, Liguria has undergone a transformation in tourism, transitioning from the location for elites to a mass tourism destination, particularly propelled by films funded by the Marshall Plan, which promote well-being, consumption, work, and leisure (Gravari-Barbas and Sabatini Citation2023; Mangano, Piana, and Ugolini Citation2020). In the context of this research, images from Liguria serve as inspirational references to convey the brand’s association with a destination that is widely recognized internationallyFootnote5. Vernon Lee (Citation1908), who extensively documented her travels in the early 20th century, posited that the profound affection for certain locations is not merely due to external attributes, but is instead a reflection of internal desires and emotions. She contended that these places “are the stuff of dreams and must be brooded over in quiet and void. The places for which we feel such love are fashioned, before we see them, by our wishes and fancy; we recognize rather than discover them in the world of reality” (Lee, Citation1908: 4).

In contrast to Liguria, Puglia experienced a surge in inbound tourism only since 2018, indicating a notable increase in tourist arrivals (Potito Citation2020). This growth is attributed to the emergence of “luxury farmhouses” a term that may seem an oxymoron, yet refers to historic farmhouses in Southern Italy that have transformed into luxury brands capable of conveying exclusivity (Sestino, Colella, and Amatulli Citation2021). However, despite their portrayal by fashion brands, these farmhouses depict a rural lifestyle far removed from the everyday reality of most Italians.

Once again, cinema serves as the primary source for depicting the freedom or leisurely pace that rural life can offer. Consider, for instance, the wedding of Gradisca in “Amarcord” or the bride among dry stone walls (muretti a secco) in “Mine vaganti” both films showcasing aspects of rural life. These same dry-stone walls are featured in Tod’s social media campaign (), showcasing a Puglian farmhouse, specifically the Masseria Lamacoppa, serving as the background for some of the analyzed images.

Image 2 @tods via Instagram. March 18 2023. Accessed via: https://www.instagram.com/p/Cp76ocQsOyv/?igsh=MWpwcnRoNHI2b2E1Mw%3D%3D.

The combination of fashion and peculiar locations (and artistic heritage) aims, therefore, to convey fashion through iconic places (Gravari-Barbas and Sabatini Citation2023; Tosi and Cantoni Citation2023) associated with lightness, more tourist destinations that convey multiple imaginaries stemming from initiatives like ModaMare Capri (1967–77) and concepts of luxury and slow living, craftsmanship, and rural life that connect well with the sustainability issue from a brand communication perspective. Indeed, as proof of this approach resulted from the research, that intertwines fashion with the (re)discovery of destinations, there is the recent trend we are witnessing: the shift of fashion shows and campaigns from the traditional hub of Italian fashion, Milan, to alternative locations fosters the communication of a fresh concept of luxury. This is exemplified by events such as D&G Siracusa, D&G Alberobello, Gucci Castel del Monte, and even Tod’s social media advertising campaign “Italian Garden”. All contribute to creating an almost ancestral idea of luxury explicitly tied to the South, a focal point of interest for the entire Creative Industries and entertainment sector: from fashion to cinema, from the natural cosmetics sector to the wedding planning industry.

Materials and decorations and the idea of perfection

Among the recurring symbols and images used by the analyzed fashion brands, we mention references to decorative motifs and materials that contribute to further investigation of those elements that are involved in the construction and communication of Italian identity and the idea of perfection.

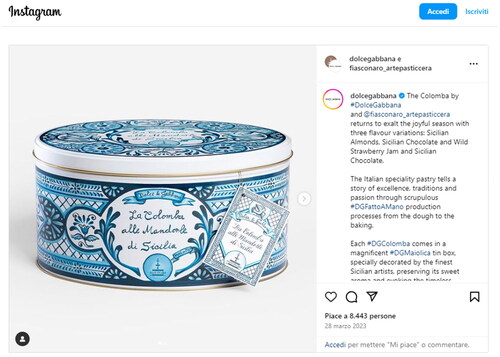

First of all, when referring to decorative motifs, there is a significant emphasis on the extensive use of (maiolica) ceramics and colors such as white, red, blue, and yellow. Beyond the considerations regarding the use of colors as a mere evocation of other Italian symbols, as later presented in the section dedicated to food, the use of maiolica is directly connected, on one hand, with the desire to highlight Italian artisanal skills, especially in the production of ceramic wares where motifs like maiolica are recurrent, as seen in the traditions of Faenza in Emilia Romagna, Caltagirone in Sicily, and Grottaglie in Puglia. On the other hand, the reference to artistic and handmade elements is directly linked to Italy’s relationship with the arts and the idea of beauty and perfection. As Lisa Hockemeyer (Citation2014) explained, Italian ceramic production is part of those centuries-old artisanal traditions, heterogeneous across different Italian regions, which experienced a positive momentum following the Second World War. American buyers played a significant role in the growth of Italian maiolica production, following a massive importation of this craftsmanship. Americans contributed to providing a national identity to this type of ceramics introducing maiolica into museums and shops as the “major forms of promotions” (Hockemeyer Citation2014: 129).

The idea of perfection associated with the artifacts of Italian brands appears to have ancient roots that evoke the creative process of “made in Italy”. As emphasized by Caianello, “the perfection (which was) attributed by the ancient peoples is closely linked to an image of nature (original)” (Caianiello Citation2005: 11). The continuous search of perfection emerges from the present analysis precisely in relation to the manual production of ceramics, particularly the Maioliche. This representation reinforces the contrast between artisanal work, considered perfect, and industrial products, deemed mundane or inauthentic (Dorfles Citation1984). Moreover, the idea of perfection is also evident in the representation of natural raw materials, such as straw, which characterizes the historic production of some fashion brands included in the analyzed sample, such as Loro PianaFootnote6.

Within the examined sample, references to maiolica ceramics are evident, such as on the packaging of culinary products offered by fashion brands. For example, D&G collaborated with Bialetti, a historic Italian brand specializing in coffee machine production. In an Instagram post, the fashion designers infused their esthetic into the iconic coffee product, incorporating patterns reminiscent of the “carretto siciliano” along with coffee cups presumably made of ceramics from Caltagirone ().

Image 3 @dolcegabbana via Instagram. March 12 2023. Accessed via: https://www.instagram.com/p/CpskuEmtJ8E/.

This leads to a reflection on the ongoing relationship between fashion and other leading sectors of the Italian industry. What characterizes “made in Italy” production, and its communication is indeed a blend of factors that can be summarized through an expression taken from the title of a book written by Mauro Ferraresi’s (Citation2014): “the beautiful, good, and well-made”.

Equally important are the materials and the elements that compose and characterize Italian fashion products, which over time have become not only iconic pieces but also peculiarities allowing for rapid recognition of the Italian brands globally. This is particularly evident in the example of Tod’s, which widely bases its communication on the exaltation of a single detail: the rubber pebble, a symbol of its loafers, the brand’s flagship productFootnote7. Over time, the brand has become a symbol of Italian style, making the shoe an iconic object, with its peculiarities that embody meanings of high symbolic value. Firstly, the brand embodies the know-how in the Italian footwear sector, especially in the Marche region, characterized by a high level of expertise and sedimentary heritage (Offidani Citation2021: 164), capable of embracing the best innovations. Secondly, the brand communicates its product beyond the immobile value of the loafer (Offidani Citation2021), understood as footwear that has endured both geographically and temporally with very few changes, focusing instead on the single detail that at first glance manages to be a defining element for the company and for the Italian factor. The rubber pebbles, i.e. The dots placed on the sole of the loafer are synonymous with the success of a company history that began in the 1970s, just when the concept of modern “made in Italy” began to take its first steps before dramatically growing in the subsequent decade. Tod’s rubber pebbles, now reintroduced with emphasis in the brand communication, indicate how a single element of the company’s heritage can serve as a means to convey the brand’s image, especially abroad. This element ensures to Tod’s a certain notoriety that can express different meanings in terms of value: from constant research to craftsmanship (a concept that returns in many of the analyzed images), to the idea of the perfect shoe that manages to withstand the spirit of time and changing trends. In this direction, Courault (Citation2005) argues exceptional levels of creativity in the Italian fashion system can be attributed to the multitude of small, local companies in the industry. These companies are filled with highly creative artisans and skilled workers who produce high-quality materials and products (Crane and Bovone Citation2006).

Culinary delights

A special mention is deserved to the template Culinary Delights. Since the Middle Ages, Italian cuisine, alongside art, literature, and other cultural products, has stood as a symbol of Italian identity (Montanari Citation2017). Traces of Italian gastronomic culture reveal how Italy has been historically perceived and represented worldwide. This aligns with an identity perspective; for instance, spaghetti and pizza belong to a heritage spread across the globe, immediately recognizable by all, representing Italian craftsmanship and the Italian image (Capatti and Montanari Citation2003). This is one reason why Italians have often been stereotyped as food-obsessed in terms of consumption and preparation (Wong Citation2017). Furthermore, the imagery surrounding the idea of the Italian meal ritual, coupled with the Italian family, has been fueled not only by real-life situations but especially by the media. For example, in Andrea Camilleri’s series of detective novels, meal descriptions in the narrative suggest expressions of Sicilian authenticity. Ferzan Özpetek, in all his films, “utilizes all aspects of Italian food culture to challenge and probe cultural norms about what it means to be Italian” (Eckert and Nowak Citation2017: 126; Eckert Citation2017). Hollywood cinema has employed food as a tool to contribute to the construction of an identity that is more Italo-American, effectively recognizable (Parini Citation2019). Italian food, through its manifestations in public discourse and media, has therefore grown rapidly in terms of cultural and social prestige, both in Italy and abroad, transforming into an international icon from the 1960s to the present day (Parasecoli Citation2019; Sassatelli Citation2019).

Food therefore becomes a cultural artifact shaped by the interactions between different geographical environments and the interplay between reality and fiction, influenced by cinema and other media. In this context, the notion of authenticity faces growing challenges due to global influences, as the continuous blending of diverse cultures disrupts traditional ideas of originality (Giannone and Calefato Citation2007: 112). This is evident in the concept of “Italianicity,” which has, for instance, evolved within the Italo-American community (Cinotto Citation2019).

Moreover, the “made in Italy”, crafted from a complex set of symbols can recreate a meaningful partnership with fashion and food in constructing Italian identity (Rabbiosi Citation2019). In Italian fashion brands, this translates into two communication strategies. The first one involves playing with the quintessential stereotypes, such as pasta, pizza, moka coffee, incorporating these elements as explicit references to Italian identity. The second references food co-branding to reinforce the concept of being Italian.

As noted in the analysis, D&G’s collaboration with Bialetti () reflects the vibrant decorations of the “carretto siciliano” while the packaging of Easter Bread () takes inspiration from the Sicilian maiolica. The D&G post presented below shows the packaging of the traditional Italian Easter Bread, further exemplifying this trend:

Image 4 @dolcegabbana via Instagram. March 28 2023. Accessed via: https://www.instagram.com/p/CqV_Vlztg7R/.

The Colomba by #DolceGabbana and @fiasconaro_artepasticcera returns to exalt the joyful season with three flavour variations: Sicilian Almonds, Sicilian Chocolate and Wild Strawberry Jam and Sicilian Chocolate.

The Italian speciality pastry tells a story of excellence, traditions and passion through scrupulous #DGFattoAMano production processes from the dough to the baking.

Each #DGColomba comes in a magnificent #DGMaiolica tin box, specially decorated by the finest Sicilian artists, preserving its sweet aroma and evoking the timeless beauty of the islandFootnote8.

Venturini (Citation2020) adds that in the D&G case pastry products or pasta crafted in collaboration with the excellence of Italian food craftsmanship are utilized by the brand to symbolize the blend of tradition.

Iconic objects

The following template presents a series of objects that have been identified as “iconic”. On this occasion, these objects pertain to personal modes of transportation and/or brands within the automotive sector that have effectively conveyed Italy’s image, particularly abroad. These objects are imbued with sociocultural significance and contribute to the definition of national identity. In these specific cases, to be detailed in the subsequent paragraphs, they represent modes of transportation that characterized various periods of economic prosperity in Italy. For instance, as elucidated by Lucia Savi, in the postwar period, Italy experienced a strong influence of Americanization (alongside funds provided by the Marshall Plan), and this connection was particularly evident in the modernization of handmade artisan products and contemporary artifacts, such as Fiat products (Savi Citation2023: 22).

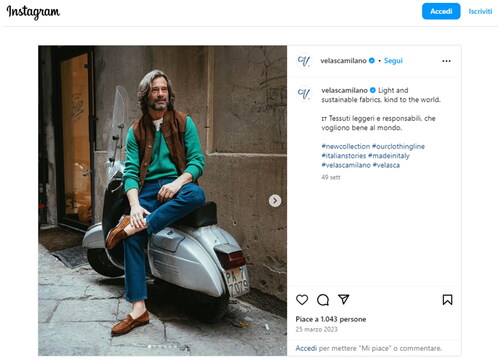

The brand Velasca Milano utilizes images that likely constitute an inspirational board. This aspect already suggests the need of the brand to create a narrative consistent with its proposal, but more importantly, to communicate the lifestyle that characterizes the brand. In this case, accompanied by the hashtags #ITALY and #FEELITALIAN, Velasca chooses to convey its Italian identity through a photograph of a Ferrari 400 SuperamericaFootnote9, as confirmed by image recognition with Google Lens and as verified by an expert car connoisseur. The sports car designed by Pininfarina is not just an iconic car; it is, in fact, one of the emblems that convey the imagery of an Italian lifestyle. In the early 1950s, Enzo Ferrari established a connection between his cars and film stars, notably the Ferrari 400 Superamerica driven by Vittorio Gassman in the 1967 film “Il tigre” directed by Dino Risi (Ferrari, Citationn.d., via Wikipedia). Analyzing more recent posts from the Velasca brand, a car frequently featured in reels is from the Alfa Romeo automaker. Also in this case, the historical significance of the Italian car company based in Milan is undeniable, showcasing the brand’s internationalization capabilities, once again tracing it in iconic movies: from “Un bellissimo novembre” with Gina Lollobrigida, an icon of Italian cinema and fashion, to “The Graduate”, with the iconic scene of Dustin Hoffman aboard a stylish Alfa Romeo.

The image evoked by the Italian style of automobiles has been solidified through partnerships with cinema, and Italian excellence, in both film and automotive production, has contributed to reinforcing the perception of “made in Italy” globally, shaping the imagery related to Italian identity (Bertolotti Citation2016). That’s why brands often employ the combination of cars and fashion. Among other cars featured in Italian brand advertisements, there’s an interesting resurgence of the Fiat Panda. Among the analyzed images, D&G chooses to include a glimpse of it to strengthen a highly evocative image of the imagination that characterizes the perception of Southern Italy (in a photo shoot in Monopoli where the “Fiat Panda” is part of the pictureFootnote10, in Bari province).

Another iconic object identified in our findings is the Vespa scooter from Velasca Milano ().

Image 5 @velascamilano via Instagram. March 25 2023. Accessed via: https://www.instagram.com/p/CqODoXiN5g1/?img_index=1.

The Vespa scooter, an icon of youth culture in the sixties (Rosati Citation2017), has found a place in international youth culture, especially in the British scene, becoming a symbol alongside Twiggy’s style and the Rolling Stones’ music (Rosati Citation2017). The communication of “made in Italy” embodies the history of Italian craftsmanship capable of communicating internationally and in the Italian collective imagination. The Vespa Piaggio also quickly became an indispensable prop in cinema. Once again, the cinema-vehicle pairing is crucial for sculpting the collective imagination of Italian identity. A symbol of social customs appears in “Roman Holiday” Audrey Hepburn and Gregory Peck, aboard a Vespa, cruise through Rome, becoming one of the symbols of the capital’s tourism (Rogolino Citation2023). Furthermore, as Thomas Brandt (Citation2014) argues, the Vespa motorcycle is intricately tied to a series of initiatives spearheaded by Piaggio that heightened the perception of Italians abroad. For instance, the establishment of the Italian Vespa Club in 1949 aimed to cultivate the stereotype of “well-behaved, gentle, and disciplined” Vespa owners (Brandt Citation2014: 274), thus playing a pivotal role in shaping the perception of the “good Italian”.

It can therefore be stated that Italian fashion brands strategically utilize cultural imaginaries to enhance their brand identity and engage with a global audience by:

Leveraging Historical and Artistic References: By featuring images of historical and artistic locations, brands connect their products with Italy’s rich cultural heritage. For example, brands use images of iconic places like Puglia’s farmhouses and the Ligurian Riviera to evoke a sense of luxury and timelessness.

Highlighting Artisanal Craftsmanship: Brands emphasize materials and decorations that showcase Italian artisanal skills, such as maiolica ceramics and hand-crafted products. This approach highlights the quality and uniqueness of their products and ties them to the broader narrative of Italian perfection and beauty.

Incorporating Food Culture: By integrating culinary delights into their marketing, brands tap into the global fascination with Italian food. Collaborations with food brands and the use of food-related imagery create a multifaceted Italian identity that resonates with international audiences.

Using Iconic Objects: Featuring well-known Italian vehicles and other iconic objects in their imagery, brands associate themselves with symbols of Italian innovation and style. This appeals to a sense of nostalgia and positions their products within a broader cultural context that is recognized and admired worldwide.

Through these strategies, Italian fashion brands effectively leverage cultural symbols and narratives to build a compelling and distinctive brand identity on social media platforms like Instagram. These cultural imaginaries allow brands to stand out in a competitive market, creating a strong emotional connection with their audience and enhancing their global appeal (Sacco and Conz Citation2023). These cultural imaginaries are represented both visually, through carefully selected imagery, and textually, through captions and hashtags that reinforce the connection to Italian identity (Fortis and Carminati Citation2009).

Discussion

The present analysis sheds light on the strategic use of Italian identity and cultural stereotypes by fashion brands on Instagram, providing significant insights into the interplay between national identity and brand communication in the digital era. In this context social media plays a crucial role in engaging users and leveraging competitive advantages related to cultural heritage. The findings suggest that Italian fashion brands, when they utilize Italian cultural imaginaries, do not merely sell products; they offer a narrative imbued with cultural and historical connotations that resonate with both local and international audiences. This strategic deployment referencing timeless locations, artisanal perfection, culinary heritage, and iconic objects, underscores the brands’ efforts to craft a unique and appealing identity and goes beyond mere fashion, highlighting the fact that the Italian fashion system is (partially) influenced by the country’s rich legacy (Mora Citation2004). The research highlights how Italian fashion companies capitalize on Taplin’s assertion that their success is rooted in Italy’s rich cultural history, the high value consumers place on esthetics, and their deep-seated commitment to style and beauty, which permeates many aspects of daily life (Taplin Citation1989, p. 418).

The identification of four key templates enhances the comprehension of the relationship between Italian fashion brands, country-related identity, and the use of stereotypes in social media communication. Moreover, it provides new insights to the existing literature and extends previous studies through the following templates:

Inspirational Places and the idea of the Indeterminacy of Time: emphasis on inspirational places such as Puglia and Sicily, along with an exploration of the indeterminacy of time, offer perspective on how Italian fashion brands create visual narratives that evoke culture, craftsmanship, and Italian tourism destinations. This category extends previous research by uncovering the role of location-based storytelling in strengthening brand identity.

Materials and Decorations and the Idea of Perfection: exploring materials, decorations, and the pursuit of perfection as brand communication tools showcases how Italian fashion brands draw on the country’s artisanal traditions to generate narratives of quality and craftsmanship. The materials and details that epitomize an ideal of Italian perfection, such as Italian ceramics and Tod’s rubber pebbles, complemented by materials like straw and cork are intertwined with the ability of Italian companies and districts to innovate during times of crisis providing customers with an experience that blends nostalgia with the assurance of purchasing a product with a longstanding reputation for quality. In addition, these materials and details are closely related to the revival of centuries-old artisanal skills. These skills seamlessly connect fashion, craftsmanship, art, and lifestyle, showcasing Italy’s rich cultural heritage and its commitment to excellence. This template further contributes to previous research by clarifying how brands use stereotypes related to materials and by explaining search of perfection pursuit by brands to align with Italian craftsmanship and textile heritage, strengthening their positioning and differentiation in the global market.

Culinary Delights: examining the use of Italian food as a brand communication tool, this template highlights the importance of culinary heritage in shaping the perceptions of Italian fashion brands. It builds on existing literature by emphasizing the intertwining between fashion and gastronomy and on how brands use stereotypes related to culinary delights to align with Italian enogastronomic heritage. Here, scents and perfumes constitute the perfect bridge in-between the two worlds.

Iconic Objects: by emphasizing the use of stereotypes related to iconic objects such as pieces of design (e.g.: luxury cars and Vespas), this template offers a nuanced understanding of how Italian fashion brands construct and communicate the concept of “made in Italy”. It further explores how brands use cultural symbols to convey Italian narratives and lifestyle, enhancing brand appeal and recognition on an international level.

Impact on brand communication strategies

The findings of this study can have significant implications for brand communication strategies, particularly in the context of globalized digital platforms like Instagram. The use of visually rich, culturally evocative content helps brands to stand out in a crowded symbolic market, creating a solid emotional connection with their audience. This approach does not only enhance brand loyalty but can also broaden a brand’s appeal by tapping into the universal admiration for Italian culture. Brands that effectively use cultural imaginaries can differentiate themselves from competitors, creating a distinctive identity that is both aspirational and relatable. As noted by Crane and Bovone (Citation2006) by effectively communicating on digital platforms, the Italian fashion system continues to enhance local artisanal production by emphasizing product quality and esthetics. It maintains a balance between exclusivity and “democratization”, distinguishing itself from other national systems. This approach allows the Italian fashion industry to preserve its identity and authenticity while continuing to play a significant role in the country’s culture and economy.

Advancing the understanding of country of origin use in the digital era

The study advances the understanding of how national identity is constructed and communicated in the digital era. The strategic use of cultural symbols by Italian fashion brands illustrates how national identity can be both preserved and reinterpreted in a globalized context. The digital era offers brands unprecedented opportunities to reach global audiences, but it also demands a nuanced understanding of how to communicate cultural identity in a way that might resonate universally. This research highlights the importance of authenticity and cultural depth in digital brand communication, suggesting that successful brands are those that can seamlessly integrate their national identity into their global messaging.

Conclusions

This research offers rich insights concerning the intricate relationship between Italian fashion brands, national identity, and the use of stereotypes in their social media communication, with a focus on Instagram. Through a thorough analysis of 21 leading Italian fashion brands, the study reveals how these selected samples strategically employ stereotypes related to Italian identity, iconic objects, and cultural imaginaries to construct and communicate the concept of “made in Italy” to a global audience.

Implications for fashion theory

This study enhances fashion theory by showing how modern fashion branding goes beyond traditional advertising methods, embedding itself deeply within cultural narratives and identity constructs. This approach aligns with the concept of “cultural branding” where brands transform into cultural icons by integrating themselves into the cultural fabric and collective memory of societies (O'Reilly Citation2005; Grenni, Horlings, and Soini Citation2019). By drawing on Italy’s historical, artistic, and cultural references, Italian fashion brands engage in cultural preservation and promotion, positioning themselves as storytellers of Italian heritage and culture. This integration emphasizes that fashion is not merely a commercial venture but also a cultural artifact that reflects and shapes societal values and identities (Noris and Cantoni Citation2022).

The research underscores the importance of the Country of Origin (COO) concept, particularly in the fashion context. Specifically, “made in Italy” extends beyond a manufacturing label to encompass cultural, historical, and esthetic dimensions, shaping consumer perceptions (Segre Reinach Citation2015). By examining imagery from Italian fashion brands, the study highlights the intentional use of stereotypes, iconic objects, and cultural references to construct and reinforce Italian identity, contributing to a complex narrative transcending mere product promotion (Ettenson, Wagner, and Gaeth Citation1988; Pike Citation2013).

Furthermore, the research underscores the role of digital technologies in general and social media in particular in enabling Italian fashion brands to globally project a curated Italian identity, perpetuating esthetics associated with “la dolce vita”. From an academic perspective, this study provides new insights into the intersection of fashion, culture, and online media, enriching the discourse on cultural branding and identity construction, offering a framework for understanding how brands can use COO narratives to enhance their identity and connect with audiences on a deeper level. Additionally, it opens avenues for exploring how other national brands incorporate cultural elements into their digital communication strategies, offering a comparative perspective on global branding practices.

Implications for practitioners

For practitioners, particularly those in the fashion and marketing industries, this study emphasizes the critical role of cultural relevance and storytelling in brand communication. The findings suggest that brands which effectively leverage their cultural heritage and present it compellingly on digital platforms can establish a strong, distinctive brand identity. This research offers valuable insights into the relational processes that shape brand communication. The findings indicate that national identity plays a crucial role in understanding the communication dynamics between brands and consumers, thereby influencing the renegotiation of meanings. Additionally, the research offers valuable guidance on how Italian fashion brands can strategically utilize stereotypes and cultural symbols to enhance their brand identity (Bellanca and Canitano Citation2008). By aligning with the positive perceptions associated with Italian culture, these brands can create a unique and appealing global image. Results underscore the importance of holistic brand communication that goes beyond product features (Van Assche, Beunen, and Oliveira Citation2020), in this way brands can integrate cultural elements, iconic objects, and narratives of craftsmanship into their communication strategies to create a resonant and engaging brand story.

Practitioners could also note the critical role of media platforms in highlighting local characteristics, particularly in the “made in Italy” context and of the industrial districts and Italian craftsmanship. The study emphasizes the influence of media on these districts’ current dynamics, underscoring social media’s potential as a tool for cultural storytelling. Brands can leverage these insights to effectively craft and communicate their cultural narratives, enhancing audience engagement and inspiration.

Limitations and future research

It should be considered that the research has some limitations, while the study focused on 21 Italian fashion brands, a more diverse sample could offer a more comprehensive understanding of companies’ practices. The analysis considered static images and was conducted within a specific timeframe, while trends in brand communication may rapidly evolve. Future studies could consider encompassing in the analysis also video/reels and utilizing a longitudinal approach to capture changes over time, especially in response to societal changes or global events. This would provide a more comprehensive and dynamic perspective on the adaptation of identity narratives. Future studies could also explore consumer perceptions and reactions to the use of stereotypes by Italian fashion brands, providing insights into how global audiences interpret and respond to these cultural cues. A comparative analysis with fashion brands from other countries could offer a broader perspective on the role of national identity in brand communication, contributing to cross-cultural understanding of how different cultures use stereotypes in the fashion industry.

Another limitation is the potential for rapid changes in brand strategies and consumer engagement on social media, which may not be fully captured within the specified timeframe. This study reflects the current strategies of the sampled brands, particularly in the luxury sector, which must balance their cultural heritage with digital technologies (Gupta, Hushain, and Mathur Citation2024). During the examined period, consumer engagement was significantly influenced by emotional factors. As suggested by Pereira, Silva, and Casais (Citation2024), brands’ value is perceived through their emotional impact on consumers, highlighting that marketing campaigns fostering emotional connections can enhance brand engagement and strengthen relationships.

While the study offers valuable insights into how Italian brands use Instagram to convey their “Italianness” and the “made in Italy” concept, it has limitations due to the dynamic nature of social media and the selection criteria based on brand rankings. Future research addressing these limitations could improve the robustness and comprehensiveness of the findings. Relying on brand rankings for sample selection ensures a focus on prominent brands but may introduce bias toward well-established and visible brands, potentially overlooking smaller, emerging brands that could provide different perspectives on Italian identity and “made in Italy” communication.

In conclusion, this research enhances our understanding of the role of cultural identity in brand communication, providing insights for brands aiming to leverage their cultural heritage in the digital age. Through this analysis, the paper contributes to knowledge on how Italian fashion brands navigate the intersection of national identity, stereotypes, and global communication. It underscores how cultural aspects and authenticity can help build a global brand reputation by highlighting the strategic use of cultural imaginaries.

The paper emphasizes a complex set of symbols, connecting fashion with cinema, food, and tourism. These symbols play a significant role in constructing Italian identity, perpetuating positive stereotypes and reinforcing the cultural narrative. Overall, this comprehensive analysis contributes to the fields of fashion theory and marketing, underscoring the enduring impact of cultural storytelling in brand communication.

Finally, findings provide practical considerations for both academics and practitioners within the dynamic landscape of fashion branding and globalized markets. They illustrate how social media platforms can effectively reach a diverse international audience and reinforce the image of “made in Italy”.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Flavia Piancazzo

Flavia Piancazzo holds a PhD in Sociology of Cultural and Communication Processes in July 2024 from the Department of Science and Culture of Well-Being and Lifestyles at the University of Bologna, with a thesis on Eurocentrism in fashion. She is Adjunct Professor in the Master’s degree program in Fashion Studies at the University of Bologna, where she teaches Media Communication and Fashion Analysis. Previously, she taught Fashion History at the Milano Fashion Institute. Flavia’s research interests center around social and cultural sustainability issues within the cultural industries, with a particular focus on cultural appropriation and stereotypes in fashion. Moreover, after a visiting period at the Digital Fashion Communication Centre at the Università della Svizzera Italiana in Lugano (CH), she is exploring the use of imaginaries in fashion and media communication. She also serves as a Junior Fellow at the CFC, Culture Fashion and Communication International Research Centre, Department of the Arts, University of Bologna. [email protected]

Alice Noris

Alice Noris holds a PhD in Communication Sciences from the Institute of Digital Technologies for Communication, Faculty of Communication, Culture and Society from Università della Svizzera italiana (Lugano, Switzerland). She is currently working as researcher at SUPSI, the University of Applied Sciences and Arts of Southern Switzerland and as post-doctoral researcher at ESCP Business School. Her research interests are centered on the digital transformation of communication and marketing, with a particular focus on the luxury sector.

Nadzeya Sabatini

Nadzeya Sabatini holds a PhD in Communication Sciences. She is Assistant Professor in Digital Transformation at Gdansk University of Technology (Gdansk, Poland). Nadzeya is Senior Lecturer and Academic Coordinator of MSc in Digital Fashion Communication, with a double degree from USI-Università della Svizzera italiana (Lugano, Switzerland) and Universite’ Paris 1 Pantheon-Sorbonne (Paris, France). She is Group Leader in Digital Fashion Communication Research at the Institute of Digital Technologies for Communication (USI). Nadzeya’s research interests are in the digital transformation of communication in fashion and luxury domains. Nadzeya has been Visiting Researcher in Hong Kong, the UK, New Zealand and Portugal thanks to the excellence research scholarships of the Swiss National Science Foundation.

Lorenzo Cantoni

Lorenzo Cantoni, PhD (1997), USI – Università della Svizzera italiana (Lugano, Switzerland), is the director of the Institute of Digital Technologies for Communication and holder of a UNESCO Chair in ICT to develop and promote sustainable tourism in World Heritage Sites. [email protected]

Notes

1 This article was collaboratively discussed and structured by four authors. During the drafting phase, Alice Noris curated the first chapter on the research context, while Flavia Piancazzo focused on the chapter presenting the results. The chapters on methodology, discussion, and conclusions were co-authored by Alice Noris and Flavia Piancazzo. Lorenzo Cantoni and Nadzeya Sabatini contributed to the research protocol and in analyzing the images, oversaw the research and helped revising the final text.

3 Lists of brands from various rankings available online:.

Kantar BrandZ Most Valuable Italian Brands.

“The Top 30 Most Valuable Italian Brands 2022” (pp. 19–20) https://www.kantar.com/it/inspiration/brands/kantar-brandz-italia-2021.

“The Kantar Brandz Top 10 Italian Luxury Brands 2022” (pp. 30–35)https://www.kantar.com/campaigns/brandz/italy.

The “Q3 2022 Hottest Brands” from the website The Lyst Indexhttps://www.lyst.com/data/the-lyst-index/q322/.

“Which brands dominated social media during Milan Fashion Week (2023)” from Nss Magazine; https://www.nssmag.com/en/fashion/31162/five-leading-brands-mfw

“Top 100, FY2021” from the report Global Powers of Luxury Goods, published by Deloitte.https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/fi/Documents/consumer-business/gx-global-powers-of-luxury-goods-report.pdf

4 See @furla via Instagram. Post published on April 1st 2023. Accessed via: https://www.instagram.com/p/CqfUlZ0vZDJ/.

5 See @velascamilano via instagram. Post published on March 29 2023. Accessed via: https://www.instagram.com/p/CqXmTOfMf0y/?img_index=1

6 See @loropiana via instagram. Post published on March 26 2023. Accessed via: https://www.instagram.com/p/CqQkF-_KYmR/?img_index=1

7 See @tods via instagram. Post published on March 22 2023. Accessed via: https://www.instagram.com/p/CqGAE0AJmHF/.

8 See @dolcegabbana via Instagram. Post published on March 28 2023. Accessed via: https://www.instagram.com/p/CqVqmUlt1Df/.

9 See @velascamilano via Instagram. Post published on April 1st 2023. Accesse via: https://www.instagram.com/p/CqfVHx0t5aG/.

10 See @dolcegabbana via Instagram. Post published on April 10 2023. Accessed via: https://www.instagram.com/p/Cq20UB5urOR/.

References

- Adamoli, G. 2017. “The Slow Food Movement and Facebook: The Paradox of Advocating Slow Living Through Fast Technology.” In Representing Italy Through Food, edited by K. E. Elgin, N. Peter, N. Zachary. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Al-Sulaiti, K. I., and M. J. Baker. 1998. “Country-of-Origin Effects.” Marketing Intelligence & Planning 16 (3): 150–199. https://doi.org/10.1108/02634509810217309.

- Balicco, D. 2015. Made in Italy e cultura: Indagine sull’identità italiana contemporanea. Città di Castello (PG): G.B. Palumbo Editore.

- Bellanca, N., and G. Canitano. 2008. “Il Made in Italy Come Immaginario Collettivo. Un Modello Degli Investimenti in Stereotipi.” Journal of Industrial and Business Economics - Economia e Politica Industriale 3: 155–179.

- Beller, M. 2007. “Italians.” In Imagology, edited by M. Beller, and J. Leerssen, 194–200. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

- Beller, M., & Leerssen, J. (Eds.). 2007. Imagology. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

- Bertolotti, A. 2016. “Sì Viaggiare…: Auto Sportive e Mito Italiano Nel Cinema Della Golden Age.” Memoria e Ricerca, Rivista di Storia Contemporanea 2/2016: 283–302. https://www.rivisteweb.it/doi/10.14647/84244.

- Bollati, G. 1972. L'italiano. In Storia d‘Italia. I. I: Caratteri originali, edited by C. Vivanti, and R. Romano, 951–1022. Torino: Einaudi. https://www.uniba.it/docenti/brunetti-bruno/attivita-didattica/StoriadItaliaBollatiG.pdf.

- Brambilla, M., H. Badrizadeh, N. Malek Mohammadi, and A. Javadian Sabet. 2023. “Analyzing Brand Awareness Strategies on Social Media in the Luxury Market: The Case of Italian Fashion on Instagram.” Digital 3 (1): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3390/digital3010001.

- Brandt, T. 2014. “A Vehicle for ‘Good Italians’: User Design and the Vespa Club in Italy.” In Made in Italy. Rethinking a Century of Italian Design, edited by G. Less-Maffei, and K. Fallan. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Brusco, S., and S. Paba. 2014. Towards a History of the Italian Industrial Districts from the End of World War II to the Nineties. Working paper, DEMB WORKING PAPER SERIES, Dipartimento di Economia Politica - Università di Modena e Reggio Emilia, 2014. https://doi.org/10.25431/11380_1190674.

- Bursi, B., B. Balboni, S. Grappi, E. Martinelli, and M. Vignola. 2012. “Italy’s Country Image and the Role of Ethnocentrism in Spanish and Chinese Consumers Perceptions.” International Marketing and the Country of Origin Effect: The Global Impact of 'Made in Italy', 45–64. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Pub.

- Caianiello, S. 2005. Scienza e tempo alle origini dello storicismo tedesco. Napoli: Liguori.

- Calanca, D. 2002. Storia sociale della moda. Italia: B. Mondadori.

- Capatti, A., and M. Montanari. 2003. Italian Cuisine: A Cultural History. New York Chichester, West Sussex: Columbia University Press.

- Cappelli, L., F. D’Ascenzo, R. Ruggieri, F. Rossetti, and A. Scalingi. 2019. “The Attitude of Consumers towards “Made in Italy” Products. An Empirical Analysis among Italian Customers.” Management & Marketing Challenges for the Knowledge Society 14 (1): 31–47. https://doi.org/10.2478/mmcks-2019-0003.

- Carini, L., and S. Mazzucotelli Salice. 2023. “Made in Italy? Images and Narratives of Afro-Italian Fashion.” In Fashion Communication in the Digital Age. FACTUM 2023, edited by N. Sabatini, T. Sádaba, A. Tosi, V. Neri, L. Cantoni. Springer, Cham: Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-38541-4_11.

- Cecere, R., F. Izzo, and M. Terraferma. 2022. “Country of Origin, Products from Different Countries and Cultural Backgrounds in the Cosmetic Industry: A Literature Review.” International Journal of Economic Behavior 12 (1): 27–44. https://doi.org/10.14276/2285-0430.3194.

- Cinotto, S. 2019. “Italian Diasporic Identities and Food.” In Italians and Food, edited by R. Sassatelli, 43–70. Palgrave Macmillan. https://www.google.it/books/edition/Italians_and_Food/UhWZDwAAQBAJ?hl=it&gbpv=1&dq=Italians+and+Food,+edited+by+R.+Sassatelli,++Palgrave+Macmillan&printsec=frontcover.

- Cirillo, O. 2021. “A “Special Ambience” for Fashion and Tourism: From Capri to Positano.” ZoneModa Journal 11 (2): 91–116. https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.2611-0563/13816.

- Colombi, M. 2020. “Understanding the Luxury Industry’s Marketing and Communications Strategies: A Case Study on the Watchmaking Industry.” Master Thesis, Université Genève.

- Courault, B. 2005. “Les ModèLes Industriels de la Mode: une Confrontation USA, Italie, France.” In: La mode. Une économie de la créativité et du patrimoine à l‘heure du marché La Documentation Francaise, edited by C. Barrière, and W. Santagata. France: Documentation Française.

- Crane, D., and L. Bovone. 2006. “Approaches to Material Culture: The Sociology of Fashion and Clothing.” Poetics 34 (6): 319–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2006.10.002.

- De Nisco, A., and G. Mainolfi. 2016. “Competitiveness and Foreign Perception of Italy and Made in Italy on the Emerging Markets.” Rivista Italiana di Economia, Demografia e Statistica-Italian Review of Economics, Demography and Statistics 70 (3): 15–28.

- Deloitte. n.d. Global Powers of Luxury Goods: Top 100, FY2021. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/fi/Documents/consumer-business/gx-global-powers-of-luxury-goods-report.pdf

- Dewan, A. 2021. “Detecting Organic Audience Involvement on Social Media Platforms for Better Influencer Marketing and Trust-Based e-Commerce Experience.” In Data Analytics and Management. Lecture Notes on Data Engineering and Communications Technologies, edited by A. Khanna, D. Gupta, Z. Pólkowski, S. Bhattacharyya, and O. Castillo, Vol. 54. Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-8335-3_51.

- Diamantopoulos, A., and K. P. Zeugner-Roth. 2010. “Country-of-Origin as Brand Element.” In Wiley International Encyclopedia of Marketing, edited by J. Sheth, and N. Malhotra, Vol. VI, 18–22. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/9781444316568.wiem06004.

- Dorfles, G. 1984. “Presentazione" In Decorazione ceramica, edited by N. Caruso. Milano: Hoepli.

- Eckert, E. K. 2017. “Inspector Montalbano a Tavola: Food in Andrea Camilleri’s Police Fiction.” In Representing Italy Through Food, edited by P. Naccarato, Z. Nowak, and E. K. Eckert, 95–110. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Eckert, E. K., and Z. Nowak. 2017. “In Cibo Veritas: Food Preparation and Consumption in Özpetek’s “Queer” Films.” In Representing Italy Through Food, edited by P. Naccarato, Z. Nowak, and E. K. Eckert, 125–138. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Ettenson, R., J. Wagner, and G. Gaeth. 1988. “Evaluating the Effect of Country of Origin and the ‘Made in.” Journal of Retailing 64 (1): 85.

- Evans, C., and A. Vaccari. 2019. Il tempo della moda. Italia: Mimesis Edizioni. https://www.google.it/books/edition/Il_tempo_della_moda/vujrDwAAQBAJ?hl=it&gbpv=1

- Ferraresi, M. 2014. Bello, buono e ben fatto: il fattore made in Italy. Milano: Guerini Next.

- Ferrari. n.d. Wikipedia. https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ferrari_400.

- Fortis, M., and M. Carminati. 2009. “Sectors of Excellence in the Italian Industrial Districts.” In The Handbook of Industrial Districts, edited by G. Becattini, M. Bellandi and L. De Propris. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Fortis, M., and M. Carminati. 2016. “Development Profiles of the Italian Industrial System and its Export from the Unification of Italy to the Present: The Case of Mechanical Engineering.” In The Pillars of the Italian Economy: Manufacturing, Food & Wine, Tourism, edited by M. Fortis, 171–218. Springer International Publishing. https://www.google.it/books/edition/The_Pillars_of_the_Italian_Economy/xuZmDQAAQBAJ?hl=it&gbpv=1&dq=fortis±2005±4f&pg=PA193&printsec=frontcover

- Giannone, A., and P. Calefato. 2007. Manuale di comunicazione, sociologia e cultura della moda. Vol. 5. Roma: Meltemi editore.

- Gioberti, V. 1844. “Primato Morale e Civile Degli Italiani.” Bruxelles: Meline & Cans 2 (2): 105.

- Giumelli, R. 2016. “The Meaning of the Made in Italy Changes in a Changing World”. Italian Sociological Review 6 (2): 241. https://doi.org/10.13136/isr.v6i2.133.

- Gravari-Barbas, M., and N. Sabatini. 2023. Fashion and Tourism: Parallel Stories. Leeds: Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1571-5043202426.

- Grenni, S., L. G. Horlings, and K. Soini. 2019. “Linking Spatial Planning and Place Branding Strategies through Cultural Narratives in Places.” European Planning Studies 28 (7): 1355–1374. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1701292.

- Gupta, V., J. Hushain, and A. Mathur. 2024. “The Future of Luxury Brand Management: A Study on the Impact of New Technology and Relationship Marketing.”. In: AI in Business: Opportunities and Limitations. Studies in Systems, Decision and Control, edited by R. Khamis, and A. Buallay. vol. 515. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-48479-7_6.

- Herz, M. 2013. “The Country-of-Origin Concept Reassessed – The Long Path from the ‘Made-In’ Label.” In Impulse für die Markenpraxis und Markenforschung, edited by C. Baumgarth, and D. M. Boltz. Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-00427-9_7.

- Hockemeyer, L. 2014. “Manufactured Identities: Ceramics and the Making of (Made in) Italy.” In Made in Italy. Rethinking a Century of Italian Design, edited by G. Less-Maffei, and K. Fallan. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Josiassen, A., and A. W. Harzing. 2008. “Comment: Descending from the Ivory Tower: reflections on the Relevance and Future of Country-of-Origin Research.” European Management Review 5 (4): 264–270. https://doi.org/10.1057/emr.2008.19.

- Kantar. 2022a. Kantar BrandZ Most Valuable Italian Brands: The Top 30 Most Valuable Italian Brands 2022 (pp. 19–20). https://www.kantar.com/it/inspiration/brands/kantar-brandz-italia-2021

- Kantar. 2022b. Kantar BrandZ Most Valuable Italian Brands: The Kantar BrandZ Top 10 Italian Luxury Brands 2022 (pp. 30–35). https://www.kantar.com/campaigns/brandz/italy

- King, N. 2004. “Using Templates in the Thematic Analysis of Text.” In Essential Guide to Qualitative Methods in Organizational Research, edited by C. Cassell, and G. Symon, 256–270. New York: Sage Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446280119.n21.

- Kotler, P., and D. Gertner. 2002. “Country as Brand, Product, and beyond: A Place Marketing and Brand Management Perspective.” Journal of Brand Management 9 (4): 249–261. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.bm.2540076.

- Krim, S. 2023. “From Imaginaries to Synergies: Christian Dior Cruise Collections.” In Fashion and Tourism (Tourism Social Science Series, Vol. 26), edited by M. Gravari-Barbas and N. Sabatini, 107–132. Leeds: Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1571-504320230000026008.

- Lee, V. 1908. The Sentimental Traveller. London: John Lane.

- Mangano, S., P. Piana, and G. M. Ugolini. 2020. “Paesaggi, Percezione e Rappresentazione: lo Sguardo Del Turista in Liguria.” Bollettino Dell’Associazione Italiana di Cartografia 169: 82–102. http://hdl.handle.net/10077/32230.

- Merlo, E., and M. Perugini. 2015. “The Revival of Fashion Brands between Marketing and History: The Case of the Italian Fashion Company Pucci.” Journal of Historical Research in Marketing 7 (1): 91–112. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHRM-02-2013-0007.

- Montanari, M. 2017. “And at Last, the Farmers Win.” In Representing Italy Through Food, edited by P. Naccarato, Z. Nowak, & E. K. Eckert, 17–32. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Mora, E. 2004. “Introduzione. Moda e Società. Questioni Italiane (Introduction: Fashion and Society, Italian Questions).” In: Questioni di moda (Fashion Questions), edited by D. Crane, 9–24. Milano: FrancoAngeli.

- Morace, F. 2004. Estetiche Italiane, Italian Ways. Le sei tendenze del Made in Italy e la loro influenza nel mondo. Milano: Libri Scheiwiller.

- Morreale, E. 2009. L'invenzione della nostalgia: il vintage nel cinema italiano e dintorni. Roma: Donzelli Editore.

- Munjal, V. 2014. "Country of origin effects on consumer behavior." SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2429131.

- Nagashima, A. 1970. “A Comparison of Japanese and US Attitudes toward Foreign Products.” Journal of Marketing 34 (1): 68–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224297003400115.

- Noris, A., and L. Cantoni. 2021a. “COVID-19 Outbreak and Fashion Communication Strategies on Instagram: A Content Analysis.” In International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, edited by M. M. Soares, E. Rosenzweig, and A. Marcus, 340–355. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-78227-6_25.

- Noris, A., and L. Cantoni. 2021b. “Intercultural Crisis Communication on Social Media: A Case from Fashion.” In Fashion Communication, edited by T. Sádaba, N. Kalbaska, F. Cominelli, L. Cantoni, and M. Torregrosa Puig. Springer, Cham: FACTUM 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81321-5_19.

- Noris, A., and L. Cantoni. 2022. Digital Fashion Communication: An (Inter)Cultural Perspective. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004523555_002.

- Noris, A., and L. Cantoni. 2024. “The Good Italian”: Fashion Films as Lifestyle Manifestos. A Study Based on Thematic Analysis and Digital Analytics.” Fashion Theory 28 (2): 151–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/1362704X.2024.2323363.

- Nss Magazine. 2023. Which Brands Dominated Social Media During Milan Fashion Week 2023. https://www.nssmag.com/en/fashion/31162/five-leading-brands-mfw

- Offidani, E. 2021. “Dalla Cristallizzazione Storica All’innovazione. Il Distretto Calzaturiero Marchigiano e il Caso Emblematico Del Mocassino.” In Un mondo di scarpe: L’evoluzione storica del design calzaturiero, edited by A. P., Pascuzzi. Roma: tab edizioni.

- O'Reilly, D. 2005. “Cultural Brands/Branding Cultures.” Journal of Marketing Management 21 (5-6): 573–588. https://doi.org/10.1362/0267257054307336.

- Parasecoli, F. 2019. “The Invention of Authentic Italian Food: Narratives, Rhetoric, and Media.” In Italians and Food, edited by R. Sassatelli, 17–42. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Parini, I. 2019. “Spaghetti and Guns: Food in Hollywood Mafia Movies.” In Mediterranean Memories, edited by A. C. Vitti, and A. J. Tamburri, 65–81. New York: Bordighera Press.

- Paris, O. 2020. “Costruire un Mito: Marche, Prodotti e la Rappresentazione Dell’italianità Nel Mondo.” Filosofi(e)Semiotiche 7(1): 2531–9434.

- Paulicelli, E., V. Manlow, and E. Wissinger. 2021. The Routledge Companion to Fashion Studies. Oxon: Routledge.

- Pavlek, D. 2015. “Evolution through Creating Unique Value Proposition: The Case of the Business Transformation and Value Proposition Development of Swiss Watchmaking Industry.” Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. https://scholarworks.rit.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=10530&context=theses.

- Pereira, D., J. Silva, and B. Casais. 2024. “Consumer Brand Engagement Fostered by Cause-Related Marketing in Emotional and Functional Brands.” Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing: 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/10495142.2024.2329258.

- Pike, A. 2013. “Economic Geographies of Brands and Branding.” Economic Geography 89 (4): 317–339. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecge.12017.

- Potito, S. 2020. “Lineamenti Dell’economia Del Turismo in Puglia Nella Nuova Fase Della Globalizzazione.” Rivista Economica Del Mezzogiorno, Trimestrale Della Svimez 1-2 (2020): 217–247. https://doi.org/10.1432/97631.

- Pucci, T., E. Casprini, S. Guercini, and L. Zanni. 2017. “One Country, Multiple Country-Related Effects: An International Comparative Analysis among Emerging Countries on Italian Fashion Products.” Journal of Global Fashion Marketing 8 (2): 98–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/20932685.2016.1274666.