Abstract

Piña cloth, or textile woven from the delicate fibers of the pineapple plant used to be the epitome of luxury and high fashion in mid-nineteenth century Philippines. The weaving and wearing of piña experienced a rapid decline largely caused by the influx of British cotton textiles so that by the last half or the 20th century it had all but disappeared. This article analyses the history of reviving piña and its afterlives. It argues that reviving piña resulted in re-inventing new blended forms of the textile (with silk, cotton, and linen), and creating new ones such as piña shifu. Because these blended varieties are cheaper and faster to make, piña has been democratized. The revival process has caused a re-thinking of piña to make it “modern” and “chic”—from adding color to it (as traditionally it was worn in its natural ecru color), turning it into casual or everyday wear, and painting on it to make it wearable art. Finally, the revival project has also altered the status of weavers and challenged gender norms.

Introduction

Piña cloth, or textile woven from the delicate fibers of the pineapple plant used to be the epitome of luxury in mid-nineteenth century Philippines (Roces Citation2013). It was worn by the elite class as the symbol of high fashion at the time. However, the weaving and wearing of piña experienced a rapid decline in the late 19th century and by the last half or the 20th century it had all but disappeared. Piña was invented by Filipinos and was very much associated with Filipino national identity so in the mid-1980s, individuals and NGOs began the process of reviving the industry, and eventually the Philippine government also came on board with the Philippine Textile Research Institute (hereafter PTRI), the Department of Trade and Industry, and the Department of Agriculture joining the crusade.

This article analyses the history of reviving piña and its afterlives. This is a massive endeavor because the production of this textile relies on contributions from the agricultural sector, the scientific sector, and the creative sector. This ranged from farmers who grow the red pineapple variety, the scrapers who scrape the leaves by hand to access the fiber, the knotters who painstakingly tie the threads together in preparation for weaving, the weavers themselves, the embroiderers, and the fashion designers. (I use the term fashion designer instead of couturier because this term embraces both designers and couturiers; some of the interviewees only do ready to wear whereas some do made-to-order and the majority do both. In addition, the Philippine government gives a national artist award for the category of “fashion design/designer” so I use this term to be compatible with the national discourse). In addition, scientists from the PTRI have also been important in “modernizing” the industry through changing looms (such as the four-harness loom, traditionally it is the two-pedal loom), developing natural dyes, and from 2021 developing QR codes that identify which weaver wove the cloth.

I argue that reviving piña is also about re-thinking and re-inventing piña as the popularity of new forms of piña blends such as piña-seda (piña with silk), piña-shifu (paper thread made from pounded piña bastos fiber), piña-cotton, and piña-linen now surpasses that of pure piña (liniwan). In addition, fashion designers have initiated the project of re-thinking piña not just as a textile used for formal wear or national dress, but as everyday fashion and high fashion. While the weaving of the combination of piña and silk, and piña and cotton have been noted by foreign traveler’s accounts in the mid-nineteenth century, these weaving blends were no longer being practiced by the late 20th century (Bowring Citation1859: 364–4, Loney to Farren Citation1857: 228). But since the blended varieties of piña are cheaper and faster to produce, they have been popularized by weavers and fashion designers so that they now dominate the market in what I label the “democratization of piña” (see also Milgram Citation2005: 241). I also argue that piña’s close association with national dress makes it difficult to imagine it as everyday modern fashion. Hence, the quandary for those involved in the piña industry is that promoting it as a national fabric and associating it with Filipino nationalism and identity seems like a logical strategy to legitimize its revival, but on the other hand, its’ close association with national dress means that it is difficult for buyers to see the cloth outside the parameters of the Barong Tagalog (national dress for men) and Filipiniana dress for women. Fashion designers who are in the forefront of the campaign to modernize piña fashion, are encouraging the use of piña in its blended forms as everyday wear or at least as not-so-formal wear. The result is that fashionable piña today (2024) is not likely to be made of pure piña.

This article is a deep dive into the ways piña was transformed by the revival process. It argues that the revival process has given birth to a re-thinking of piña itself—from adding color to it, to suggesting that it be used for casual rather than formal occasions, and even painting on it and turning it into wearable art. Hence, this article is as much about how artisans and fashion designers have begun the process of re-thinking piña, as it is about reviving piña. Finally, this project of reinventing and re-thinking piña has been able to alter the status of weavers and challenge gender norms.

Sources for this article include both archival research and interviews. The archival data includes travelers accounts of 19th century Philippines, the consular reports of Nicholas Loney, British Vice Consul to Iloilo, his published letters, and parliamentary reports of British Vice Consul Shelmerdine of Iloilo. I have conducted interviews (in Taga-lish, a mixture of Tagalog and English language) with: (1) weavers of four weaving companies, (2) 5 fashion designers who work with piña, (3) the Chief Scientist at the Philippine Textile Research Institute who had a huge role in inventing natural dyes for piña, (4) two embroiderers who work on piña, and (5) the former governor of Aklan Florencio Miraflores. I also used data from India Dela Cruz-Legazpi’s presentation to the Special Committee on Creative Industry and Performing Arts Conference on July 29, 2021.

Piña history

The Philippines became a Spanish colony in the sixteenth century. The pineapple plant was introduced to the Philippines through Spanish contact (Montinola Citation1991: 83, 132). In her pioneering book on the history of piña, Lourdes Montinola pointed out that Iloilo, Capiz, Antique, and Aklan in central Philippines were the main centers of piña production (Montinola Citation2005: 70). The actual process of producing piña was extremely labor intensive from start to finish. There were four traditional ways of extracting the fibers from the leaves of the pineapple plant, namely scraping, hand-stripping, retting, and decorticating (Montinola Citation1991: 52, Madrid Citation2023a). The most common method was scraping. First the prickles of the leaves were carefully removed. Then the epidermis and the pulp on both sides of the leaf were removed with a dull knife and then the split leaf was put on a wooden board where the pulp was scraped off with the smooth edge of a broken porcelain plate. When the fibers appeared they were removed in one motion from the scraped leaf. Two types of fiber became exposed: a coarser one (called bastos) used for making twine and wigs for icons or dolls, and a finer one which was used for weaving piña cloth (liniwan). Pineapple leaves produced 75 percent of bastos and 25 percent of liniwan.

Hand-stripping involved inserting a strip of the pineapple leaf into the opening of a bamboo device and pulling it down the base to the tip. Only strong fibers could withstand this pressure and the rest were discarded. The retting process involved the immersion of pineapple leaves in water for a period of time that allowed bacteria or fungus to dissolve the plant gums and facilitate the separation of the fibers. The leaves were then split into narrow strips using the hand-stripping method. Finally, decortification or the removal of the cover, husk, or plant tissue, was done by a motorized decorticating machine. There is still no existing machine for pineapple fibers so to obtain spinnable fibers the decorticated or retted pineapple fibers need further reduction of gum content, which is done through chemical degumming (Montinola Citation1991: 53–4).

After the fibers were extracted and the threads washed and dried, the next excruciating task was joining the pineapple threads together end to end to make a continuous filament (La Piña 2005: 54). The task of “knotting the fine piña fibers as close to the end as possible so as not to waste fiber is an ordeal to the uninitiated” (Montinola Citation1991: 63). Weaving was another labor intensive process. Even today (2023) weaving pure piña would only produce ¼ meter of cloth per day. Women were the weavers, as Nicolas Loney, British Vice Consul to Iloilo observed in the mid-nineteenth century: “all the female population appears to be employed in weaving” (Loney to Nanny 1856: 63). Finally, intricate embroidery was also a distinctive feature of piña. Techniques included calada or drawn thread work, “in which threads are pulled out of the fabric to create openwork, or drawn together to form a design” (Montinola Citation1991: 109, Madrid Citation2023a).

Piña cloth signaled the epitome of luxury, refinement, and wealth in 19th century Philippines. The wearing of piña was synonymous with speaking Spanish, gentility, wealth, refinement, urbanity, and the manners of a romantic era. Weaving piña, embroidering piña, and wearing piña, were most clearly associated with the mestizo race (Spanish-Filipino and Chinese-Filipino)—the group that in the mid-nineteenth century imagined themselves to be “Filipino” (Roces Citation2013).

Scholar Linda Welters who examined how piña was collected as souvenir by travelers to the Philippines in the nineteenth century, demonstrated convincingly that in the middle of that century, it was the central Philippines province of Iloilo in the island of Panay which was best known for its textile industry including piña production (Welters Citation1997). Loney’s report revealed that in 1857 there were about 60,000 looms (though his letter to his sister in 1856 said that he heard that the estimated number of 50,000 looms was “rather off the mark” (Loney to Nanny 1856: 62), exporting about $400,000 (of “mixed piña stuffs” –ie “piña, silk, hemp & other manufactures” in his classification) (Loney to Farren Citation1857: 229–231). But by 1887 a report by Vice Consul Shelmerdine to the British parliament disclosed that the textile industry had so greatly declined that its importance shrunk to less than half of what it used to be (Shelmerdine Citation1887: 2). He blamed the sudden demise of the textile industry on the importation of cotton cloth from Manchester and Glasgow (Shelmerdine Citation1887:2). Historian Randy Madrid who published the most recent book on the history of piña (building on Montinola’s pioneering book) claimed that “the impact of textile importation from England was devastating to the native textile industry despite provincial Chinese efforts to sustain it. After 1877, the Iloilo textiles never regained their former status as one of the prime export goods of the province” (Madrid Citation2023b: 237).

Reviving piña weaving in Aklan province

The trajectory of piña’s decline continued well into the twentieth century. Although Montinola and Madrid explained the decline primarily due to the influx of British cotton imports, I argued elsewhere that another reason for its decline was that the advent of the new colonial ruler (from 1902) created an Americanized elite whose tastes differed from the Europeanized elites who wore piña (Roces Citation2013). As concepts of high-end luxury changed where piña no longer had a place, it lost popularity as fashionable dress and instead came to be seen as something to wear in occasions where one was required to perform Filipino national identity (Roces Citation2013, Milgram Citation2005). In the late 20th century, it seemed that no one was weaving piña blends anymore (so that when weaving the blend of piña and silk was revived in the 1980s, two of my interviewees claimed they introduced it). By the 1980s, the supply of piña dwindled in quantity so much that it was considered almost rare by the select few who wanted to buy it. The owner of Filipiniana store Tesoros for example, confided to her daughter-in-law, fashion designer Patis Tesoro, that it was so difficult to find piña that she kept the little she had in a safe (Tesoro Citation2021). Then in the mid-1980s, when Tesoro went to Kalibo with Lourdes Montinola and Ado Escudero, she discovered that it was very hard to find, and that hardly anyone could tell them if the red pineapple was still being farmed. Concerned that the industry was dying, Tesoro and Escudero through their organization Patrones de Casa Manila (formed in 1988 to revive Filipino traditions including clothing), launched the initiative to try to revive piña. The project was financially supported by a government grant of ₱ 70,000 and ₱ 5 million (in 1988 the conversion was ₱35.61 to one US dollar) from the Coca-Cola Foundation and the Katutubong Foundation (a nonprofit organization founded to promote Filipino arts and culture with the First Lady Amelita Ramos as patron). To encourage the planting of the red pineapple species Tesoro organized a Piña contest in Aklan where the farmer with the most pineapple crowns was honored. The work involved liaising with the Aklan College of Agriculture which promoted the growing of the red pineapple species (Tesoro Citation2003). The First Lady at the time Amelita “Ming” Ramos (1992–1998) encouraged the populace to wear Filipiniana dress on Mondays (Dela Cruz-Legazpi Citation2022). She popularized piña worn as a kimona blouse during the Philippine centennial celebrations that commemorated the Philippine revolution against Spain (1996–98) (Moreno Citation2002).

Kalibo, Aklan province in Central Philippines was identified as the best site for reviving piña. In the 1980s there were still a handful of piña weavers in that area and there were still farmers who grew the red pineapple species. A handful of enterprising male and female entrepreneurs embarked on setting up family businesses from 1986 until 1998. I will analyze four key elements in the transformation of the piña production industry resulting from the advocacy to revive it from 1998 to the 2023. The first is the introduction of scientific and technological innovations that changed the way piña was woven, and introduced new blended forms of piña such as piña-seda, piña-cotton, piña-lino (linen) and piña-shafu, and pioneered the dyeing of piña in both natural and chemical dyes. But the popularity of the new blended forms which were easier and faster to produce meant that blended forms now dominate the market and finding pure piña is still rare. Secondly, the family companies that have built their business in this time of piña revival are thriving. Three out of the four weaving companies I interviewed came from humble beginnings but by 2023 they had transformed themselves into successful businesses. This was followed by the introduction of weaving centers for the very first time in the history of piña weaving. Thirdly, the advocacy to give status to weavers by awarding prizes and bestowing the best weavers with prestigious titles such as “Cultural Master” and inviting them to participate in textile conventions has empowered them and inspired the next generation of weavers. Finally, ten to fifteen percent of weavers are now male, as former construction workers and fishermen began to join the weaving labor force (Alan Tumbokon Citation2022, Citation2023, Eliserio Citation2023). Hence, reviving the piña industry resulted in a revolutionary change in gender norms. I will discuss each of these points in detail below.

Part of the credit for the success in the revitalization of this traditional textile is also due to the scientific sector. The PTRI taught weavers how to use looms not used before, and ran seminars on how to make natural dyes. According to Dr. Julius Leaño Jr. the Chief Science Research Specialist in PTRI, “the part that science plays in Philippine textiles has never been as huge as now” (Leaño Citation2021). The PTRI popularized the four-harness handloom which increased the speed of weaving. Alan Tumbokon, founder of La Herminia Piña Weaving credited the blossoming of his business in the short span of three years to the use of this new loom:

so noong ma-introduce ng PTRI iyong multi-harness niya, iyong four-harness handloom, doon ano, doon kami nag-ano, nag-develop ng product… kasi, di ba, product naming is barong. Pinag-aralan ko iyong technique kung paano ko ilagay doon lang sa gusto kong design… at doon nag-umpisa na makagawa kami ng barong na multi-harness na, four-harness na siya. at doon parang ang bilis… ang bilis lumago

[when the multi-harness or four-harness handloom was introduced, that was when we developed the product—because, isn’t it, our product is barong [Barong Tagalog, national dress for men], I studied the technique for how to put the design I wanted, and so that was when we began to make a Barong Tagalog using the multi-harness, using the four harness already, and then it took off, our business prospered very fast (Alan Tumbokon Citation2022).]

Scientific innovations also included the development of natural dyes. Leaño developed natural dyes because he believed that a textile as fine, delicate, and natural as piña deserved to be treated with natural dyes rather than subjected to unnatural harsher chemical dyes (Leaño Citation2021). Traditional pure piña was not dyed. The concept of dyeing piña was conceived to make it appealing to the younger demographic and to “modernize” the look of piña. PTRI gave seminars to businesses like La Herminia Piña Weaving, Raquel’s Piña Products, and Aklan Arts and Crafts transmitting the scientific knowledge to the industry (Eliserio Citation2022, Alan Tumbokon Citation2022, Dela Cruz-Legazpi Citation2021). The PTRI seminars on natural dyeing techniques inspired Carlo Eliserio to experiment with new types of naturally-sourced dyes from local plants (Carlo Eliserio Citation2023).

But the scientific interventions went beyond improving the technology behind producing pure piña to weaving combinations of threads to make new blended textiles such as piña-seda (piña with silk), piña-sinamay (piña-abaca), piña-cotton and piña-linen (piña-lino). The term piña-seda was coined by India Dela Cruz-Legazpi who told me in an interview that she popularized this new textile – which is also known as piña-jusi and piña-cocoon. She used the word “seda” instead of silk in order to make the Spanish terminology consistent since piña is already a Spanish word (Dela Cruz-Legazpi Citation2023). PTRI has also been developing sericulture in the Philippines to give weavers access to locally produced silk in order to encourage the weaving of piña-seda (Leaño Citation2021). British accounts in the 19th century revealed that piña textiles were already being mixed with silk (Bowring Citation1859: 336), and a photograph of a shawl in a book on Philippine see-through textiles in the Intramuros museum collection showed a piña shawl with silk accents in the design (Escobar Citation1990: 61, Plate No. 53). Dela Cruz Legazpi’s innovation was to blend piña with silk in a 50–50% combination (Dela Cruz-Legazpi Citation2023). In my interview with her she confided that the competition between pure piña weavers in Aklan motivated her in 1987 to try a different blend:

Ang sabi ko, what I will do if I will enter into weaving piña I should go into a different blend. Kasi para hindi ako mag-compete sa 100% piña that time [so I do not compete with those producing 100% piña at that time]. So nag-develop ako ng piña-seda to lower the price [so I developed piña-seda to lower the price.] (Dela Cruz-Legazpi Citation2023)

Weaving pure piña would only produce ¼ meter of cloth per day. A prize-winning weaver such as Ursulita Dela Cruz could only produce 2 centimeters a day (with suksuk (brocading weft) design introduced in the weaving process) working for about 4 or 5 hours a day. The weavers of Raquel’s Piña products can only produce 20–50 cm a day and less than 50 meters per month (Dela Cruz-Legazpi Citation2022). Multi-award winner Raquel Eliserio can produce one and a half meters per day of pure piña (Eliserio, Raquel 2023). In contrast weaving piña-seda would increase the production to 2 meters a day since the silk breakage in the warp seldom happens (Dela Cruz-Legazpi Citation2022) (silk was used for the warp and piña liniwan for the weft).

The advantage of the blended varieties of piña was that they were faster to make making supply easier and cheaper. Hence, given these practical considerations and the weaver’s own preference to focus on piña-seda and other blends, Dela Cruz-Legazpi underscored that “piña production is vibrant but not focused anymore on weaving 100% piña” (Dela Cruz-Legazpi Citation2022). An examination of the percentage of pure piña now produced per weaving company compared to piña-seda clearly demonstrated the preference for the blended version. In 2023, La Herminia Piña Weaving only produced piña-seda. Raquel’s Piña Products (100 weavers) produced 60% piña-seda and only 30% pure piña (Eliserio Citation2022). Only Dela Cruz House of Piña, the smaller company with only 15 weavers, focuses on pure piña.

A new textile was created from processing the bastos piña fiber into a paper form—and then slicing that into threadlike strips –called piña-shifu. This was a very welcome invention because it was sustainable; using the 75% of the fiber that was only used for pillow stuffing or as hair for religious icons (since liniwan or pure piña used only 25% of the fiber extracted from the leaf). This “new” textile was welcomed by fashion designers such as Gabbie Sarenas because it endowed the usually limp piña with volume (Sarenas Citation2021a).

It was not just the practice of weaving piña that was revived. Weavers also revived some of the traditional embellishments introduced into the textile in the weaving process with some also adding new twists to the traditional woven-in design methods. For example, La Herminia Piña Weaving revived the tablero rengue (rengue is a woven-in design that produces an open-work effect, while tablero refers to a checkered pattern (Madrid Citation2023a, Citation2023b: 105)) and added double-surfaced pockets to the pocket nips design (Alan Tumbokon Citation2022, Citation2023).

The second key element I analyze here is the flourishing of the weaving companies and the establishment of weaving centers. I attribute the success of these companies to the scientific and technological advances introduced to the traditional process and to the development of the piña blends. When India Dela Cruz-Legazpi of Aklan Heritage and Crafts introduced piña-seda her weaving business grew from 2 weavers in 1988, to 240 weavers across 27 barangays (the smallest town/village unit) by 1998 (Dela Cruz-Legazpi Citation2023). Alan Tumbokon’s family business began with only one weaver in 1996—Alan’s mother Herminia, but in three years’ time it grew to 130 weavers and 300 knotters (the ratio is that one needs 3–5 knotters per weaver) (Alan Tumbokon Citation2022). By the turn of the 21st century the business was large enough to run three weaving centers: 1 in Kalibo, one in Balete, Barangay Fulgencio, and one in Apga, Tangalan; all in Aklan province (Alan Tumbokon Citation2022). In addition, Alan’s sister Arlyne runs the marketing side from an office in Manila (Alan Tumbokon Citation2022, Arlyne Tumbokon Citation2022).

Dela Cruz House of Piña started the business with 2 weavers (a mother and daughter), and by 2023 employed 15 weavers. But this company is unique because it is the only one that focuses on pure piña (Dela Cruz and Sulangi Citation2022, Citation2023). Raquel Eliserio had to sell all her livestock (a total of two pigs) in order to raise the capital to launch Raquel’s Piña Products. In my interview with her, she tearfully recalled the early years of struggling to get her company going with very little capital. When EN Barong, a clothing brand approached her to supply them with the textiles for their Barong Tagalogs, the business blossomed with son Carlo Eliserio in the lead (Eliserio Raquel Citation2023). In 2022, the company had grown to include 300 artisans composed of farmers, knotters, warpers, and weavers. In 2023 their weaving center employed 100 weavers (Eliserio Citation2022). The establishment of weaving centers transformed the production of piña from a one-person business venture that was located in the domestic sphere (the home), where work hours were built around the daily routine of managing domestic chores and child or elderly care, to a professional occupation with regular hours at a workplace outside the home.

The third key element of the revivalist movement was the elevation in the status of weavers. In 1999 the first annual Aklan Piña and Fiber festival was launched. The event included a textile competition. In April, 2004 on the initiative of India Dela Cruz-Legazpi, it featured an Aninag Fashion Festival (aninag means sheer or see-through in the local language, referring to the transparent nature of piña cloth) (Dela Cruz-Legazpi Citation2023). Governor Florencio “Joven” T. Miraflores (governor for three terms, 1995, 1998, and 2001) supported this fashion show with a ₱ 1 million (in 2004 the conversion rate was ₱35.73 to 1 US dollar) grant to cover the costs of the fashion designers, the clothes and the professional models (Miraflores Citation2023).

On her 90th birthday, Lourdes Montinola asked friends to donate to HABI Philippine Textile Council instead of gifts, and the donations were used to initiate a piña weaving competition named after her, which she continues to fund from 2018 with an attractive prize money of ₱100,000 for the winning weaver (Montinola Citation2022, Madrid Citation2023a: 216) (in 2018 the conversion rate was P52.7 to 1 US dollar). This competition stood out because not only did it give status to the weavers, it also encouraged innovation and complex weaving designs since one of the criteria was for “quality of innovation and use of imagination,” and there was a special category for innovation (Madrid Citation2023a: 216–18). Entries to this competition required the weavers to give titles to their submissions elevating the textile produced to the status of the work similar to that of visual artists who give individual titles to each of their paintings. The 2018 first prize went to India Dela Cruz-Legaspi’s “Handwoven Piña-Seda Fabric with Tablero Rengue,” The 2019 first prize went to Raquel Eliserio’s “Handwoven Piña Liniwan-Seda Shawl with Full Suksok and Rengue,” the 2020 first prize went to Rowena Regusta’s (from La Herminia Piña Weaving) “Piña-Seda with Multicolor Tablero, Ringue, and Sinuksok,” and the 2022 first prize went to Ursulita Dela Cruz’s “Kahel” (the local word for orange) (), while the 2022 first prize for innovation went to Carlo Eliserio’s “Iñigo” (Madrid Citation2023a: 219–234). There was even an “outstanding young weaver award” which went to 12 year old Delara (Darlene) Eliserio (Raquel’s daughter and Carlo’s sister) for “Sampaguita” (the Philippine national flower) in 2021 and “Sorbetes” (Ice Cream) in 2022 (Madrid Citation2023a: 233).

Figure 1 “Kahel,” first prize Lourdes Montinola piña weaving competition for 2022, piña liniwan (with suksuk design), woven by Ursulita Dela Cruz, from Dela Cruz House of Piña, Photo by Thea Sulangi.

An analysis of the evolution of the titles revealed that at first weavers’ entries described the techniques they used for weaving the cloth but by 2021 and 2022 they realized that like Picasso’s Guernica, they could give their one-of-a-kind, carefully woven cloth a literary name much like artists did for their paintings. Hence the weavers themselves embraced their elevated status as solo artists recognized for their craftsmanship, as opposed to anonymous artisans. In 2021 the PTRI lobbied to have QR Codes for each weaver which could be stamped into the cloth giving them the same brand and status as designers (Leaño Citation2023). In this case, when this happens, (in June 2024 they were in the optimization phase of the photoluminescent security inks with the aim to have the technology launched by the end of 2024) (Berces email correspondence June 25, Citation2024) weavers will no longer be anonymous.

Fashion designer Len Cabili has also introduced the Filip + Inna Innovation award named after her fashion brand from 2021, and the Nadres family of EN Barong Filipino also gave an award for Outstanding Young Weaver under 30 also from 2021 (Madrid Citation2023a: 226, Cabili Citation2023). Raquel Eliserio was given the prestigious national award of Cultural Master for Weaving Piña awarded by the National Commission for Culture and the Arts tasked with transmitting the craft to the next generation in the School of Living Traditions. In 2021 she won an international prize (the Global Eco Artisans Awards in the textile category by eco-artisanal fashion brand AGAATI) where she competed with 31 countries. Her entry took her two months to weave (Soliman Citation2021).

Finally, the piña revival project also altered constructions of gender. Whereas in the 19th century weaving was almost exclusively a woman’s occupation, since the 1990s that is no longer the case. In 2023, about ten percent of 100 weavers working for Raquel’s Piña Products, were men (Eliserio Citation2022). La Herminia Piña Weaving had a similar gender percentage (Alan Tumbokon Citation2022). According to Alan Tumbokon the men (most of whom were the husbands of women weavers) preferred to weave piña because it provided a more stable income compared to fishing which is seasonal, and was perceived to be a better alternative occupation to construction work which involved hard physical labor in the hot sun. In 1996 when piña commanded good prices, they could earn a good salary of between ₱8000–10,000; making it an attractive occupation (Alan Tumbokon Citation2022) (in 1996 the exchange rate was ₱35.75 to one US dollar). (Since then, the competition brought prices down). My interviews with two male weavers of La Herminia Piña Weaving confirmed this. Richard Saligumba worked in the labor force of the construction industry in Kalibo and Roli Arboleda was a fisherman before Alan Tumbokon taught both men to weave (Arboleda Citation2023, Saligumba Citation2023). According to both men, Alan was a good role model for them—since they could see that another man could weave, they did not feel embarrassed about taking on an occupation linked to cultural constructions of the feminine (Arboleda Citation2023, Saligumba Citation2023). As more men became weavers and earned a good living from it, this caused a revolutionary change in gender ideals (Alan confided that male weavers produce a tighter weave than women—considered a better quality (Alan Tumbokon Citation2022)). Their skills were recognized also by prizes: Roli Arboleda won a prize for weaving abaca (rather than piña) in the Louise Hizon Abaca Competition (Arboleda Citation2023).

Rethinking piña through couture and embellishment: can piña be chic?

Fashion designers were also crucial players in the project of reviving piña. In this section, I will analyze how designers have embarked on the project of rethinking piña from formal wear to everyday wear, and from traditional wear to contemporary fashion. It will discuss designers’ response to these two crucial questions: (1) How can piña be modern? and (2) Can piña be chic? Designers also had to cope with the problem of the shortage of supply (Tesoro Citation2021, Sarenas Citation2021a, Tan-Gan Citation2021, Citation2023). According to Leaño a P100,000 supply of 10 yards of piña liniwan may appear in the market for a buyer but one may have to wait another six months for the next supply (Leaño Citation2021) (in 2021 the conversion was 51.1 Philippine pesos to one US dollar). Designer Lulu Tan-Gan complained that accessing piña liniwan was unpredictable: if she ordered 60 yards, and was promised it would take a month, three months later she would only be presented with 20 yards, one third of the original order (Tan-Gan Citation2021). A solution to this practical problem of lack of supply was to concentrate on blended piña. These blended forms that dominate the market democratized piña and displayed the possibilities for transforming piña into modern Filipiniana fashion, luxury fashion, and as everyday fashion. Here, I will also focus on how designers have embraced piña blends, and introduced the innovations to popularize the textile. Finally, this section will also examine the way designers have embellished the clothing to accentuate its status as luxury wear or underscore its potential as “the Prada of the Philippines” (Dela Cruz Citation2021).

Gabbie Sarenas, one of the younger established fashion designers involved in popularizing piña lamented: “Why do most people view the material piña as old or limited to formal occasions?” (Sarenas quoted in Bride Magazine Citation2020). Fashion designer Lulu Tan-Gan echoed this sentiment when she complained: “why does piña always have to look traditional? (Tan-Gan Citation2021). According to Leaño, the stereotype image among the youth was that piña was a textile worn only by their grandmothers (or for weddings), a perception confirmed by Thea Sulangi (Ursulita’s niece) of Dela Cruz House of Piña who lamented that “people will only buy piña if there is a wedding” (Leaño Citation2021, Sulangi Citation2022). Designer Renee Salud pointed out that “those who are invited to be ninangs [godmothers] in weddings, they said that their uniform is the piña embroidered gowns” (Salud Citation2023). Godmothers are usually prominent or respected women of a senior age.

This perception comes from piña’s association with the 19th century elites who first popularized it – so that in the turn of the twenty first century, piña evoked feelings of nostalgia for this historical past (Roces Citation2013). Fashion designers were faced with the major challenge to answer the question “how can piña be chic”? (San Juan Citation2020: C2). The strategies they used to achieve this rethinking of piña fashion included: the popularization of piña blends, the use of piña in different colors or dyes, and introducing the notion that piña can be used not just as formal wear but also as casual-chic. The incentive to introduce color to the piña was to give it a new modern look and to explore its potential as everyday fashion wear ( and ).

Figure 2 Raquel Eliserio wearing a piña-seda with suksuk weave modern jacket over piña-seda casual chic dress.

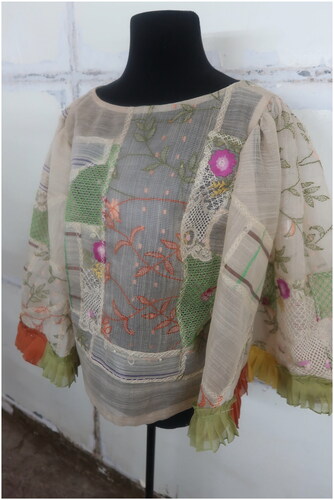

For designer Lulu Tan-Gan known as the “Queen of Knitwear,” it was logical for her to think about combining piña with knits—as both are hand woven and both are sustainable (Tan-Gan Citation2021). Tan-Gan was attracted to piña because it was luxurious and ethereal, and she aspired to give piña a more “modern feel” by introducing the innovative concept of using piña as the sheer garment that formed the outer layer for modern knit wear worn underneath it (Tan-Gan Citation2021, Citation2023) (). Designer Gabbie Sarenas uses piña-shifu since shifu is still considered luxurious because of the expense (Sarenas Citation2021a). She used piña linen and pina shifu (in colors such as black) giving piña the volume not associated with its traditional look. This innovation according to one journalist described Sarenas’ work as “Piña Made Chic” (San Juan Citation2020: C2, Sarenas Citation2021b). Since designer Len Cabili of the brand Filip + Inna showcased Philippine craftsmanship from artisans all over the country (and particularly from Mindanao, Southern Philippines, her birthplace), it was a natural choice for her to do work with piña. Cabili used piña in blue and embellished the neckline with seed pearls and or shell beads. She also experimented with piña blends such as piña with abaca and silk. She continues to be a regular customer of Dela Cruz House of Piña’s liniwan cloth (Cabili Citation2023) ().

Lulu Tan-Gan is a designer that primarily produces ready to wear clothing rather than made to order. To appeal to the younger clients who perhaps cannot afford the most expensive piña and to make piña wear more modern she focused on design: “the design is important because design means—design comes with function… for me to make this relevant is really the design” (Tan-Gan Citation2023). She confided that her secret to giving the clothing a contemporary look and feel is: “I use motifs that are Filipino-related. like this is a motif from the Inabel [Ilocano] blanket, but you don’t really think its Filipino, right? So that is how I get away with being contemporary. hindi masyadong literal [it is not too literal]” (Tan-Gan Citation2023). Tan-Gan sews her piña wear by hand including the seams to maintain the delicate, ethereal quality (Tan-Gan Citation2023).

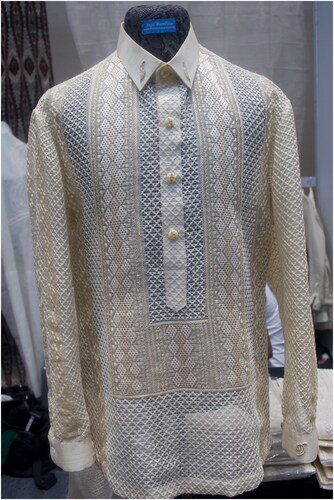

Designers also chose to embellish the clothing to accentuate its status as luxury cloth. Two ways of embellishing piña include (1) through designs produced in the weaving process and (2) through embroidery. There are several types of designs introduced in the weaving process: suksok (brocading weft), rengue (open work), and tablero (checkered patterns of alternating sections of open work and plain weave) (Madrid Citation2023a: 91–105). There are four types of embroidery used on woven piña: tapado (“embossing the design with a foundation of simple back stitches”), calado or “pulling threads to make small perforation” which looks like lace, sombrado or shadow embroidery (“worked on the reverse of the fabric employing herringbone stitch”), and filete (finishing in the edges) (Madrid Citation2023a: 121–123). Calado is the more popular technique favored today. Weaving companies tell me that they usually outsource the embroidery to Lumban, Laguna province or Taal, Batangas province—both in northern Philippines (). The embroidery motifs have a wide range: from leaves, flowers, traditional motifs to elaborate one-one-of a kind symbols such as the ones Salvador Yasona (considered by my interviewees to be the best embroiderer in the country) made for the Ambassadors to the Philippines, Filipino politicians and leaders of the state bureaucracy that featured garuda (for HE Wutipong Chaisang, the Minister of Science and Technology of Thailand), the Thai national flower or the Golden Shower Tree (for Mr. Poonsuk Pongpat, the Thai Deputy Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Science and Technology Thailand), as well as baybayin (the pre-colonial Filipino writing script) for the Director of Advanced Science (Bombasi Citation2023, Yasona Citation2023, Leaño and Malabanan Citation2009, Leaño Citation2023).

Embroidery work is extremely labor intensive. It takes 3 days of a 14-hour workday for Yasona to complete the embroidery for one regular Barong Tagalog and 10 days of around 12 hours a day to finish a complex calado embroidery. As Taal embroiderer Angel Bombasi lamented “hindi biro ang magburda” (literally meaning embroidering is not a joke, attesting to the hard work involved) (Bombasi Citation2023). Gabbie Sarenas confides that it takes two days to embroider 40 sampaguitas (the Filipino national flower) (Sarenas Citation2021a). The prices of the garments reflect the labor of love required. Yasona quoted me the price of ₱5000 for a Barong Tagalog he embroidered that took him ten days to finish. Some of the ones he embroidered for Filipino American designer Anthony Legarda cost from ₱8000–10,000 (in 2023 the exchange rate was PHP55.6188 to one US dollar) (Yasona Citation2023). The most elaborate Barong Tagalog displayed at the front of Bombasi’s booth (for the Taal Batangas province based family company Bordado ni Apolonia) at the Likha Textile Convention in Manila on June 2023 was completely embroidered (that is; every single part of it had embroidery), took months to do and cost P30,000 (a regular one would cost P5000 and a fully embroidered, one could cost between P10,000–30,000) (Bombasi Citation2023) ().

Much embroidery referenced Filipino national symbols: Gabbie Sarenas’s signature icon is the sampaguita (the Filipino national flower), La Herminia Piña Weaving uses the calesa (horse drawn carriage), the jeepney, a coconut tree with fruit, and the pineapple fruit, and Lulu Tan-Gan’s trademark is the langgam (Filipino ant) (Sarenas Citation2021a, Tan-Gan Citation2021, Alan Tumbokon Citation2022). Hence, perhaps it is not surprising that piña cloth is still very much connected to Filipino national identity and national dress despite the current project to modernize it. Canadian anthropologist Lynne Milgram examined the connections between piña and nationalism in the Philippines (Milgram Citation2007, Citation2011). Using the work of Aklan designer Carol Albay, she demonstrated convincingly how Philippine Centennial celebrations in 1996–1998 which marked the 100-year anniversary of the Philippine Revolution against Spain further endorsed this link between piña and nationalism (Milgram Citation2005). However, since the turn of the twentieth century, the use of color as well as changing the structure of the Barong Tagalog (from a shirt that has no buttons) has also modernized it. The Barong Tagalog can now be worn in colors other than white or ecru, and it has been given buttons at the front ( and ). Designer Renee Salud argued that to make piña “youngish-looking”:

Figure 10 Carlo Eliserio wearing a piña-seda Barong Tagalog with buttons in the front at the Likha 2023 festival Taguig June 13, 2023.

you could make piña very colourful… you could cut it to pieces and then sewing it together, and it creates another. of fabric. it’s just a matter of texturing it. it’s just a matter of putting a lot of cuttings… and the silhouette matters a lot, that makes it young. you could combine it with other fabrics. you could pin-tuck it, you could pleat it, but pleats by hand, because the … does not stay (Salud Citation2023).

Designer Gabbie Sarenas is fond of using piña-shifu and she used it to make aprons (Hindrika Bouquet Apron) and bibs which can be worn to accessorize modern everyday wear (Sarenas Citation2021b). Yet, in Sarenas view the use of piña-shifu still sends the message of luxury and elegance as she said in my interview with her: “I consider it luxury, mahal siya eh” [I consider piña shifu a luxury because it is expensive] (Sarenas Citation2021a).

The designer most known for her piña embellishment experiments was Patis Tesoro. She used a lot of beads and embroidery combined with appliqué, and patchwork (or “sewing together patches of piña fabric with indigenous cotton textiles to form a new ensemble”) (Madrid Citation2023a: 152). Her designs which appeared also in international exhibits included not just formal wear but also bandanas, “minis, short shifts, jackets, and palazzo pants” (Madrid Citation2023a: 152). Tesoro’s clothes bore her distinct style of embellishment—with beads, embroidery, and appliqué in both contemporary and her own versions of modern national dress (Tesoro Citation2023) (). She believed that blended piña was more attractive and practical as everyday contemporary fashion:

You will see now that I mix, mix, a lot of piña with other fabrics like cotton and abaca, because you just can’t have pure piña, pure embroidery, all by itself. It’s just too expensive. And people want something that’s more wearable, and so to mix it with cottons and other fibers would be for me today, today’s way of living. (Tesoro Citation2021).

Finally, fashion designers and weavers are now also painting on piña; an innovation introduced by Aklan weaver and artist India Dela Cruz-Legazpi. After graduating from college in 1971, India enrolled in Chinese painting under Professor Chen Bing painting on silk cloth (Madrid Citation2023a: 57). She started to paint on piña cloth after her grandmother gave her the last 10 meters of piña that she owned. Painted in scarfs and shawls, piña then becomes wearable art (). Others have taken inspiration from her. Carlo Eliserio has also been experimenting on painting on woven piña textile () and Lulu Tan-Gan uses silk printing as well as digital printing in her designs (Tan-Gan Citation2023).

The project of rethinking piña as modern and contemporary is still an ongoing one. Interviews with La Herminia Piña Weaving and Raquel’s Piña Products reveal that weaving companies claim that the main market for the cloth is national dress—or more specifically—a high end, luxury version of national dress. The dimensions of the woven cloth already correspond to the couture requirements for the Barong Tagalog and Filipiniana dress: for example, Raquel’s Piña Products weaves the dimension of 30 inches since Barong Tagalog requires four yards of 30 inches of fabric while the Filipiniana or terno (national dress for women with butterfly sleeves) requires a minimum of five yards of the 30-inch width of the same cloth (Eliserio Citation2022). Most of the piña woven by La Herminia Piña Weaving will be made into Barong Tagalog. As Carlo Eliserio put it: “it takes the labor of 13 people to produce one Barong Tagalog over two years from the pineapple plant, to the finished product” (Eliserio Citation2022). And it would cost P15,000 (for one Barong Tagalog) (in 2022 in was P55.73 pesos to one US dollar) which Eliserio says does not adequately compensate the labor involved. The more embellishment of course, the higher, the price, the more luxurious the dress.

A dress embellished with embroidery and beads by designer Patis Tesoro would be on the higher end costing about ₱100,000 -150000 (Tesoro Citation2021) (the exchange rate was ₱51.182 to one US dollar in 2021). She confided that ₱250,000 did not cover all the costs for an elaborate wedding dress. Embellishment was always part of piña’s trademark as luxury fashion since the 18th -19th centuries (Roces Citation2013, Montinola Citation1991, Madrid Citation2023a). While embroidery techniques have not radically changed, designers now added beading, applique, and painting in the project of re-thinking piña textile as “chic” or modern high fashion.

Conclusion

The revival of the piña industry achieved some success with the peak occurring in 2004–2008 (Arlyne Tumbokon Citation2022). In my interview with her in 2003, Patis Tesoro said it was then possible to buy a thousand yards of piña; a supply that one could not possibly acquire fifteen years earlier (Tesoro Citation2003). La Herminia Piña Weaving grew from one weaver in 1996 to 300 weavers in 1998, but it started to decline and struggle from 2021 onwards with only 60 weavers in 2022 (Alan Tumbokon Citation2022). On the positive side, weaving centers have been established (traditionally weavers wove at home). Some weaving designs were revived. The PTRI revived the double weave design, and Alan Tumbokon of La Herminia Piña Weaving innovated this double weave design by introducing pockets (Alan Tumbokon Citation2023). La Herminia Piña Weaving also revived the Tablero Ringgue weaving design on the cloth (Alan Tumbokon Citation2023). But although the statistics of the number of weavers in piña weaving companies look optimistic for the revival industry, this needs to be qualified with the caveat that the majority are no longer weaving pure piña and instead are weaving a blend of piña with another textile – usually silk.

The advocacy to revive piña has been able to give status to weavers and designers. My interviews with five prize winning weavers (Raquel, Carlo, and Darlene Eliserio, Ursulita Dela Cruz, and India Dela Cruz-Legazpi), and one prize winning weaving company (La Herminia Piña Weaving) conveyed to me that the status of prize winner had given them the incentive to continue to weave despite the challenges. Designers who worked on piña and other Philippine textiles were also honored in the pop-up events such as Artefino (festival to celebrate Filipino artisanship) and Ternocom (which celebrates the terno or national dress for women with butterfly sleeves) (Tan-Gan Citation2023).

Since weaving was traditionally performed by women, Julius Leaño of PTRI proclaimed that “when we empower weavers, we empower our women” (Leaño Citation2021). And indeed, some of the women weavers have been empowered. When designer Patis Tesoro went to Kalibo for the purpose of reviving piña weaving in the mid-1980s, she visited Susima Dela Cruz’ (late matriarch and founder of Dela Cruz House of Piña) house and purchased her entire supply of pure piña (liniwan) (Tesoro Citation2021, Citation2023). Tesoro confided to me that she noticed during her visit Susima was not even able to entertain her visitor with a cup of coffee because of her humble situation (Tesoro Citation2021, Citation2023). Tesoro noted this in the late 1980s, but now the Dela Cruz House of Piña company has two mansions in Kalibo! When I visited in June 2023, the newer one has a café and a bed and breakfast attached to it as well as a fabulous pina showroom that looked like a textile museum.

An unexpected outcome of the revival movement was the change in gender norms. Because weavers were paid relatively well and because there were now successful male role models in the industry, (such as Alan Tumbokon founder of La Herminia Piña Weaving and Carlo Eliserio of Raquel’s Piña products, both men with degrees in engineering), men are now becoming weavers of fine piña cloth. I should qualify that most male weavers were husbands of female weavers since the most common way to learn to weave was to be taught by a family member or in the case of La Herminia Piña Weaving, by the owner of the weaving company. I also noticed this pattern in the embroidering of piña. Salvador Yasona told me in my interview with him that his late father who founded the family embroidery business endured taunts that he was “bakla” (the Tagalog word for gay or transwoman)—because embroidering was gendered female. His father succeeded in erasing some of the stigma by proving that it was a lucrative job and now his son is currently considered by designers and Aklan weavers as the best embroiderer in the country (Yasona Citation2023).

While the revival project has been largely a success, piña production continues to face challenges. The labor-intensive process means that fewer weavers want to work with the cloth. Many opt to weave piña combined with silk, linen, or cotton (with silk being more popular), because it is faster and cheaper. Fashion designers have introduced the concept of piña as contemporary fashion. At the moment (2024), its close association with national dress has meant that it is mostly worn in very special occasions for which both national dress and contemporary couture are required. Wearing piña in national dress is still considered luxury attire especially when it has been designed by a top fashion designer. La Herminia Piña Weaving for example supplied the piña-seda for the Barong Tagalogs worn by the APEC delegates in 2015 designed by well-known fashion designer Paul Cabral (Alan Tumbokon Citation2022, Arlyne Tumbokon Citation2022). Politicians and their spouses walk the red carpet in couture forms of national dress for the annual President’s State of the Nation Address (SONA) (Roces Citation2023). The choice of piña for their “catwalk” appearance ensured that their fashionable choice was both nationalistic and luxurious (Roces Citation2023). It is in these landmark “moments,” or occasions that piña and fashion in the contemporary period dovetails with its nineteenth century semiotic equivalent.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mina Roces

Mina Roces is a Professor of History at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia. She is the author of 5 books, the most recent being: The Filipino Migration Experience: Global Agents of Change, (Cornell University Press, 2021, winner of the 2022) NSW Premier's General History Book Prize, and Gender in Southeast Asia (Cambridge University Press, 2022). In 2019 she received the Grant Goodman Prize of Excellence in Philippine Historical Studies given by the Philippine Studies Group of the Association for Asian Studies. In addition, she was co-editor of several anthologies including The Politics of Dress in Asia and the Americas (Sussex Academic Press, 2007) and in 2022 she edited a Special Issue on Dress as Symbolic Resistance for the International Quarterly for Asian Studies, 53 (1). Her research interests lie in twentieth century Philippine history particularly women's history, and Filipino migration history, as well as the history of dress. In 2016 she was elected fellow of the Australian Academy of the Humanities. E-mail: [email protected]

References

- Arboleda, Roli. 2023. “Interview with Author, Likha Convention, Taguig Metro Manila.” June 13.

- Berces, Marie Antonette V. 2024. “Email Correspondence with Author on the Status of QR Codes for Weavers.” June 25, Berces is the Science Research Specialist 1 in PTRI.

- Bombasi, Angel. (aka Jason Calamag Catapan). 2023. Interview with author. Likha Convention, Taguig, Metro-Manila, June 13.

- Bowring, Sir John. 1859. A Visit to the Philippine Islands. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Cabili, Len. 2023. “Interview with Author.” Metro Manila, June 20.

- Dela Cruz, Fats. 2021. “Facebook Post in La Herminia Piña Weaving Facebook Page.”

- Dela Cruz-Legazpi, India. 2021. “Piña, Abaca, Raffia and Silk Weaving Industry in Aklan.” Presentation to the Special Committee on Creative Industry and Performing Arts Conference (via Zoom). July 29, 2021. Accessed May 2022. https://www.facebook.com/HouseofRepsPH/Videos?853988028866062.

- Dela Cruz-Legazpi, India. 2022. “Interview with Author.” Zoom. April 4.

- Dela Cruz-Legazpi, India. 2023. “Interview with Author.” Kalibo, Aklan Province. June 7, 2023.

- Dela Cruz, Ursulita, and Thea Sulangi. 2022. “Interview with Author.” November 21.

- Dela Cruz, Ursulita, and Thea Sulangi. 2023. “Interview with Author.” Kalibo, Aklan Province. June 6.

- Eliserio, Carlo. 2022. “Interview with Author.” Zoom. May 18.

- Eliserio, Carlo. 2023. “Interview with Author.” Balete, Aklan Province. June 4.

- Eliserio, Raquel. 2023. “Interview with Author” Balete, Aklan Province. June 4.

- Escobar, Vicenta Mendoza. 1990. Nipis: An Exhibition of Philippine Fabrics Organized by the Museum Division, Intramuros Administration, November 23-December 29, 1990. Manila: Intramuros Administration.

- La Piña: El Tejido del Paraíso. (exhibition catalog). 2005. Madrid: Vive La Moda.

- Leaño, Julius. 2021. “Interview with Author.” Zoom. October 27.

- Leaño, Julius. 2023. “Interview with Author.” Taguig, Metro Manila. June 21.

- Leaño, Julius L., and Jenice P. Malabanan. 2009. Bahaghari Colors of the Philippines. Taguig City: Philippine Textile Research Institute.

- Loney, Nicholas. 1856. “Letter to Nanny, Iloilo, November 23, 1856.” In A Britisher in the Philippines or the Letters of Nicholas Loney, 58–67. Manila: National Library.

- Loney, Nicholas. 1857. “Loney To Farren”, April 1857. PRO F.O. 72/927, Published in Robert MacMicking.” In Recollections of Manila and the Philippines. Manila: Filipiniana Book Guild.

- Madrid, Randy M. 2023a. Piña Futures. Weaving Memories and Innovations. Manila: Far Eastern University & HABI: The Philippine Textile Council.

- Madrid, Randy M. 2023b. “The Provincial Chinese and the Progress of Iloilo Textile in Nineteenth-Century Philippines.” China and Asia 4 (2): 220–242. https://doi.org/10.1163/2589465X-04020003.

- Milgram, B. Lynne. 2005. “Piña Cloth, Identity and the Project of Philippine Nationalism.” Asian Studies Review 29 (3): 233–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357820500270144.

- Milgram, B. Lynne. 2007. “Entangled Technologies: Recrafting Social Practice in Piña Textile Production in the Central Philippines.” In Neo-Craft: Modernity and the Crafts, edited by Sandra Alfody, 137–154. Halifax: NSCAD University Press.

- Milgram, B. Lynne. 2011. “Recommunitizing Practice, Refashioning Capital: Artisans and Entrepreneurship in a Central Philippine Textile Industry.” In Textile Economies: Power and Value from the Local to the Transnational, edited by Walter E. Little and Patricia McAnay, 223–243. Landham, MD: Altamira.

- Miraflores, Florencio ‘Joven’. 2023. “Interview with Author.” Kalibo, Aklan province, June 8.

- Montinola, Lourdes R. 1991. Piña. Metro-Manila: Amon Foundation.

- Montinola, Lourdes R. 2005. “The Queen of Philippine Fabrics.” In La Piña: El Teijido de Paraiso (exhibition catalog), 70–72. Madrid: Vive La Moda.

- Montinola, Lourdes, R. 2022. “Interview with Author.” Zoom, May 26.

- Moreno, Jose. Pitoy “” 2002. “Interview with Author.” Metro Manila, July 10.

- Roces, Mina. 2013. “Dress, Status, and Identity in the Philippines: Pineapple Fiber Cloth and Ilustrado Fashion.” Fashion Theory 17 (3): 341–372. https://doi.org/10.2752/175174113X13597248661828.

- Roces, Mina. 2023. “Gender, Nation, Fashion, and Modernities in the Asia-Pacific, 1900-Present.” In The Cambridge History of Global Fashion, Vol. 2, From the Nineteenth Century to the Present, edited by Christopher Breward, Beverly Lemire and GiorgioRiello, 1091–1122. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Saligumba, Richard. 2023. “Interview with author.” Likha Convention, Taguig, Metro Manila, June 13.

- Salud, Rene. 2023. “Interview with Author.” Zoom, September 11.

- San Juan, Luis Carlos. 2020. “Gabbie Sarenas: Piña Made Chic.” Philippine Daily Inquirer Lifestyle. March 13, 2020, C2.

- Sarenas, Gabbie. 2020. “Bride Magazine, Article about Her in Gabbie Sarenas.” Facebook posts.

- Sarenas, Gabbie. 2021a “Interview with Author.” Zoom, August 2, 2021.

- Sarenas, Gabbie. 2021b. www.gabbiesarenas.com/hindrika-bouquet-apron. accessed March 10, 2024

- Shelmerdine, Vice-Consul. 1887. “Report by Vice-Consul Shelmerdine Respecting the Native Cloths Manufactured in the District of Iloilo.” Foreign Office Miscellaneous Series No 48. Report on the Native Manufactures of the Philippine Islands.

- Soliman, Michelle Anne P. 2021. “Piña Weaver Wins Global Prize.” Business World Online. March 22. Accessed August 8, 2023. https://www.bworldonline.com/editors-picks/2021/03/22/351683/pina-weaver-wins-global-prize/.

- Sulangi, Thea. 2022. “Interview with Author.” Zoom, November 21.

- Tan-Gan, Lulu. 2021. “Interview with Author.” Zoom, September 21.

- Tan-Gan, Lulu. 2023. “Interview with Author.” Makati City, June 15.

- Tesoro, Patis. 2003. “Interview with Author.” Pasig City, September 2.

- Tesoro, Patis. 2021. “Interview with Author.” Zoom, August 30.

- Tesoro, Patis. 2023. “Interview with Author.” San Pablo, Laguna Philippines, June 16.

- Tumbokon, Alan. 2022. “Interview with Author.” Zoom, February 14

- Tumbokon, Alan. 2023. “Interview with Author.” Kalibo, Aklan province, June 5.

- Tumbokon, Arlyne. 2022. “Interview with Author.” Zoom, February 21.

- Welters, Linda. 1997. “Dress as Souvenir: Piña Cloth in the Nineteenth Century.” Dress 24 (1): 16–26.

- Yasona, Salvador. 2023. “Interview with Author.” Muntinlupa Metro Manila, June 17.