ABSTRACT

A vivid regional and international debate on the significance of local politics and the respective actors came back to life after the Arab uprisings in 2011, which initiated decentralisation reforms in several MENA countries. Decentralisation advocates expect the reforms to foster democratisation, local autonomy and the overall socioeconomic situation, but Middle Eastern regimes also engage in decentralisation reforms for the sake of their own durability. This article assesses the potential of decentralisation reforms to develop mechanisms that contribute to authoritarian upgrading. We systematically include subnational politics and dynamics, as they are essential for deepening our understanding of the potential for reforms to uphold non-democratic regimes. Decentralisation is a promising test case, as the delegation of power away from the centre towards subnational actors and institutions affects the regime’s ability to control the polity. In our analysis, we focus on three salient aspects that influence the outcome of a decentralisation reform: (1) the legal outline of decentralisation, (2) its financial organisation as well as (3) the management of central, regional, and local elite networks. Subnational authoritarian upgrading via decentralisation reforms in Jordan and Morocco seem to focus on the satisfaction and containment of civil society as well as on the management and control of elites and oppositional actors.

Introduction

An analytical focus on the national regime level has dominated the mainstream of research on state, power, and politics in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) since the 1980s. The strong centralist orientation of contemporary political regimes in the region resulted in a scholarly neglect of politics beyond the capital. When in 2011 the Arab world’s protests first erupted in the nations’ peripheries, the blind spots of this central state bias became evident and stimulated research on politics from below (e.g. Hoffmann, Bouziane, and Harders Citation2013). A vivid regional and international debate on the significance of local politics and the respective actors came back to life, which helped initiate decentralisation reforms in several MENA countries. Western donors including the IMF and the World Bank, as well as local civil society activists encourage these reforms. They expect decentralisation to enhance local autonomy and the overall socioeconomic situation of a country. Moreover, the reforms are framed as a minimally invasive form of democratisation: They are believed to bolster the efficiency of local service provision, to increase regime accountability and good governance, and to create new opportunities for political participation. As Arab countries are amongst the most centralised in the world with an average 5% of public spending on local governance in 2008, in contrast to 35% in OECD countries, the benefits of decentralisation reforms are assumed to be especially high (Harb and Atallah Citation2015b; Kherigi Citation2017; United Cities and Local Governments Citation2009).

Initiatives to strengthen subnational governance systems as well as neoliberal reforms have been part of the political programme in MENA countries since the 1980s and 1990s, but the implementation is often characterised a ‘grand delusion’ (Kienle Citation2001). In this sense, compelling evidence for the merits of decentralisation is thus far scarce for most MENA countries. This leads us to the assumption that Middle Eastern regimes use decentralisation policies in a way that benefits authoritarian regime durability. Authoritarian regimes tend to choose a controlled top-down approach towards decentralisation. While they present the reforms as stepping stones towards regime change and subnational autonomy, the legislation is designed to enhance the central state’s limited control of politically relevant dynamics on the local and regional levels of government (Bergh Citation2017; Clark Citation2018; Harb and Atallah Citation2015a; Jari Citation2010).

We assess the potential of decentralisation reforms to develop mechanisms that contribute to authoritarian upgrading (Heydemann Citation2007; Hinnebusch Citation2012). Literature on authoritarian upgrading is mostly focusing on national politics, especially in the Arab world. We argue that broadening the focus of analysis by systematically including subnational politics is important in order to understand the dynamics of regime durability more comprehensively. After all, decentralisation as the delegation of power away from the centre towards subnational actors and institutions reflects a regime’s ability to control the polity.

In order to unveil the link between decentralisation reforms and authoritarian upgrading, this contribution starts with a critical assessment of the state of the art of decentralisation in the MENA region in light of the literature on authoritarianism and authoritarian upgrading. The analysis then focuses on three intertwined aspects that determine the outcome of a decentralisation reform: (1) the legal outline of decentralisation, (2) its financial organisation, and (3) the management of central, regional and local elite networks under the condition of neopatrimonialism (i.e. personalist patron-client-relations). As empirical cases, we choose to examine the extensive and still ongoing decentralisation reforms which Jordan and Morocco initiated in 2015. As ‘revolution survivors’, the kingdoms introduced ambitious decentralisation reforms in the course of their announced reform processes in the aftermath of 2011. The two countries share several similarities including a monarchical regime type and the kings’ religious legitimacy (Lucas Citation2004). Both monarchies are lower-middle income countries that managed to survive the Arab uprisings relatively unscathed, without being able to rely on the rentier system to soothe the protest movements. The decentralisation reforms illustrate an example for regime responsiveness, aiming to appease the population’s demands for political change and better socio-economic development. Our exploratory analysis of subnational elements of authoritarian upgrading in the (ongoing) decentralisation processes in Jordan and Morocco reveals an emphasis of the reforms on the satisfaction and containment of civil society as well as on the management and control of elite circles and the opposition. As of now, economic and efficiency gains of the reforms are hardly observable. Quite the contrary, in some areas the reforms even seem to impede possible gains, especially concerning administrative efficiency.

Decentralisation in the MENA region: potentials for authoritarian upgrading

Decentralisation: a panacea?

Decentralisation has become an almost ubiquitous, legitimacy-creating goal of state organisation in transitional and developing settings. It is also greatly encouraged by international donor organisations (Demmelhuber, Sturm, and Vollmann Citation2018). Decentralisation is the structural and organisational delegation of state tasks, competencies, and responsibilities from the centre to subnational actors and institutions. Since decentralisation moves politics and the decision-making process closer to the people, proponents of the reforms expect manifold positive implications: Democratisation effects result from additional possibilities of civic participation. The proximity and small-scale approach of politics should further increase accountability and good governance, as public control gets easier. Because local institutions can more accurately respond to the immediate needs of their citizens, administrative efficiency is believed to increase. Since territorial units compete with one another, advocates anticipate better political solutions, policy innovation as well as economic development. Soothing or balancing effects on regional disparities of ethnic and economic nature are furthermore attributed to a decentralised political order (De Vries Citation2000; Hutchcroft Citation2001; Kherigi Citation2017; Treisman Citation2007).

The normative arguments for decentralisation are compelling but may be misleading: States can implement decentralisation without seriously challenging the centre of power. In order to create some of the above-mentioned benefits, it is sufficient to deconcentrate administrative tasks without granting further decision-making competences to the subnational level. Moreover, if local entities are too small, the potential duplication of local service provision may also lead to increased inefficiency compared to a more centralised approach. A reform may cause competitive behaviour amongst subnational entities, which eventually leads to a deepening of regional struggles and imbalances. Furthermore, increasing local and regional autonomy in order to pacify heterogeneous conflicts could encourage separatist movements (Treisman Citation2007). Thus, despite all the good prospects, the outcome of decentralisation processes varies heavily across different countries and world regions (for further discussion see Demmelhuber, Sturm, and Vollmann Citation2018, 5–7).

Decentralisation and authoritarian upgrading

Decentralisation is not a one-size-fits-all approach. Depending on the intentions of the regime, the formulation and implementation of decentralisation within the specific context of a country may only generate some of the above-mentioned effects. Following the protests of 2011, MENA regimes that increased their commitment to decentralisation aroused scholars’ suspicions of focusing more on their stabilisation than on democratisation effects (Harb and Atallah Citation2015a). Ruling regimes can manipulate decentralisation by institutional design via a specific set of legal and financial provisions, as well as indirectly through the management of elites and opposition (Aalen and Muriaas Citation2018; Buehler Citation2018, 130–131). The implementation of decentralisation policies can therefore also function as a mechanism of authoritarian upgrading (Heydemann Citation2007). Authoritarian upgrading describes the use of certain regime strategies to encounter external or internal pressure for democratic change and liberalisation. Contrary to the assumption that authoritarian regimes mainly respond to these threats with different degrees of repression, the literature on authoritarian upgrading argues that their strategies are a lot more advanced and diverse. By complying with certain societal demands and implementing minor reforms, authoritarian regimes try to use shallow liberalisation (1) to satisfy and contain the civil society, (2) to manage the opposition and other (potentially) relevant elites, and (3) to profit from the benefits of selective reforms (especially concerning efficiency, development, and economic gains). In reality, the mechanisms of authoritarian upgrading can overlap and exist in varying combinations depending on the political sector and context under consideration (Heydemann Citation2007, 5).Footnote1 Contrary to the common presumption of an antagonism between (democratic) change and regime durability, the literature on authoritarian upgrading also hints at authoritarian regimes’ flexibility and consistency despite international and domestic pressure for change (for an overview see Rivetti Citation2015; Cavatorta Citation2015). Heydemann’s argument highlights the pressure coming from the international community as incentive and important addressee of authoritarian upgrading. Literature has already widened the international approach by adding the central state perspective to the research on authoritarian upgrading (Parolin Citation2015; Kohstall Citation2015). We contribute to the state of research by further developing Heydemann’s three aforementioned strategies in order to make them applicable to subnational political dynamics:

Societal demands for social, economic or political adjustments target a regime’s legitimacy. If rulers successfully manage to exploit or hijack such societal phenomena, they might not only contain them, but also benefit from them. Ways to cope with the challenges coming from within the civil society include the capture of societal demands via state-controlled institutions, commissions or selective reforms. The regime may (formally) accept the demands or it can counter them with its own legitimation narrative. Repression or the integration into regime-led commissions can discourage societal leaders from further protests. In addition, the creation of a pro-regime NGO system that hijacks the discourse of societal organisations falls under the umbrella of authoritarian upgrading. The multi-faceted expectations towards local governance reforms offer various possibilities to demonstrate responsiveness on subnational levels. Decentralisation reforms are framed as a means to fulfil societal demands (e.g. socioeconomic development, participation, and citizens’ rights). The regime portrays its own responsiveness and its ability to improve the situation of the populace as a classical means to legitimise its rule (Easton Citation1965; Gerschewski Citation2013; Vollmann and Zumbrägel Citation2018). However, if the respective local governance reforms are only partially implemented or delayed, if legal provisions remain vague, contradicting or subject to central approval, the regime can impede actual change beyond imitative institution building (Albrecht and Schlumberger Citation2004).

When speaking of controlling political contestation, the literature on authoritarian upgrading often focuses on the containment of electoral processes and the control of oppositional elites. We argue that coopted elites and potential regime allies are also targets of a regime’s attempt to ‘upgrade’ its rule. Reform processes offer incentives for different strata of relevant elites to engage with the political system and the political regime. Participation offers a way to gain positions of prestige and access to state resources that in turn can be redistributed within the own personal network. Participation may even provide a chance to influence policies. Lust (Citation2009) describes this strategy as ‘competitive clientelism’ on a national level. In addition, the systematic fragmentation and disorganisation of party systems as well as the repression of opposition parties belong to a regime’s repertoire of instruments (Albrecht Citation2013). Simultaneously, controlled spaces for political competition can appease and contain both the opposition and other elites without seriously endangering the status quo. The danger of eroding public trust regarding formalised participation including elections is imminent (i.e. notions that the ‘game is rigged’), however this affects not only the regime (via threats of societal boycott, new protests) but also the political contestants. The latter may be accused of engaging with cooptation and thus, lose their credibility as opposition. Decentralisation reforms offer additional incentives for political participation and contestation. However, the newly established competition may also be part of the regime’s strategy to balance power relations between elites on all levels of government as new struggles for influence and resource distribution between different institutions may emerge.

In addition to the containment of societal demands and the reinforcement of the regime’s relations with elites on different levels of governance, economic and administrative benefits of a decentralisation reform can further strengthen central rule. Certainly, provided that the central regime is able to increase the capacity, outreach, and economic performance of the state (Andersen et al. Citation2014) – and thus to gain power despite the fact that it is now sharing the power over specific issues with subnational institutions. The attraction of investments and international aid for a modernisation of subnational governance can lead to job creation and improve central expenditures – and thus diminish societal pressure (Hanson Citation2015). The employment within subnational state institutions is traditionally part of many MENA regimes’ patronage system and decentralisation reforms offer new possibilities in this regard.

Analytical perspectives and approach: laws in context, fiscal policy, and elite networks intertwined

In order to apply our analysis of strategies of authoritarian upgrading to decentralisation attempts, we focus on three analytical dimensions that are key to the outcome of decentralisation processes in MENA countries. An assessment of the chances and limitations of decentralisation reforms and their impact on authoritarian upgrading requires in-depth case studies and thus cannot be limited to the formal-legal analysis of legislation. While the influx of international financial aid is an important aspect to consider when analysing decentralisation reform projects in the MENA region, for the limited scope of this contribution we focus on domestic factors exclusively. The (1) legal aspects are preconditions of a decentralisation process. However, the outcome of decentralisation is largely subject to its (2) financial organisation and the (3) ability, structure, and agenda of central, local, and regional elite networks. Informal institutions play an important role for the relationship between the legal framework and the other aspects as they stand for the neopatrimonial character of politics (Helmke and Levitsky Citation2004). The following section discusses why these three factors are decisive for the analysis of decentralisation reforms in the MENA region and their potential contribution to authoritarian upgrading.

Firstly, it is necessary to look at both, the de jure framework and the de facto implementation and functioning of a decentralisation process: A coherent and adequate legal framework can lessen institutional insecurity and increase the chances for decentralisation to succeed (Houdret and Harnisch Citation2019, 6–7). Nevertheless, the scope of the reform relies on the will and the underlying motives of the regime to decentralise, which is also the link to a reform’s potential for authoritarian upgrading. A regime can implement modifications to the existing system of subnational governance without ever endangering the status quo, that is, central control over subnational issues. Hence, despite the formal changes, central institutions and actors continue to dominate and control significant decision-making processes and supervise socio-political dynamics within subnational institutions. Furthermore, formal-legal weaknesses of a reform such as vague wording, overlapping duties, and a hierarchical structure may incite conflict and competition amongst institutions and actors on all levels of governance, which eventually limits their power and effectiveness. The legal framework of a decentralisation reform may thus contribute to authoritarian upgrading by creating domestic and international recognition for the reform, but simultaneously maintain the pre-existing power balance between the centre and the periphery. It takes time until societal structures and the institutional landscape adapt to institutional change. The implementation of a major reform usually requires follow-up legislation to formalise details and procedures. Problems with financial regulations and administrative procedures may only appear after the broader reforms entered into force. From the beginning, the distribution of responsibilities amongst involved institutions and actors can be unclear. If this is the case, informal processes may fill the voids (Helmke and Levitsky Citation2004).

Secondly, decentralisation reforms usually aim at boosting economic development, improving fiscal relations between the centre and the periphery and, accordingly, budget generation and provision for subnational institutions. However, even a well-intentioned legal framework that comprises vast competences for subnational institutions is inefficient, if local and regional actors lack the financial means and capacities to act accordingly (Altunbaş and Thornton Citation2012; Demmelhuber, Sturm, and Vollmann Citation2018; Houdret and Harnisch Citation2019). Thus, the scope of fiscal decentralisation is decisive as subnational financial records hint at the political will of the regime to decentralise. If the reforms are accompanied by significant changes in subnational budget generation and spending, as well as the amount of capital transfers to the periphery, this might signal either a widening or a reduction of subnational autonomy. The more a regime commits itself to fiscal decentralisation and thus, to less central control over subnational budgeting, the more it is willing to decentralise. A successful implementation of such changes contributes to the appeasement of the domestic society and international organisations. But this is also where the link between fiscal decentralisation and authoritarian upgrading becomes visible: Even if subnational institutions are formally labelled as financially independent bodies, they may de facto have no real fiscal autonomy. The authority over budget distribution and spending may remain with central institutions despite the reforms, because it is in the interest of an authoritarian regime to keep subnational institutions financially dependent on the centre as additional control mechanism. Hence, regimes can benefit from economic and financial improvements of a decentralisation reform without losing their power to control subnational financial issues.

The composition of elite networks and their interactions within the different levels of government are key to analysing the de facto functioning of decentralisation. Ruling regimes in the Arab world are characterised by their dependence on neopatrimonial networks (personalist patron-client-relations) as a means to handle the socio-politically fragmented periphery. We build our research on Perthes’ broad definition of the politically relevant elite (PRE). The PRE includes all state agents holding executive powers as well as individuals, organisations and opposition figures with enough strategic significance to influence the political process. Moreover, the PRE also includes individuals and groups outside the political elite that have the power to influence the political process (Perthes Citation2004, 5–7). Depending on their composition and agenda, elite networks on all levels of government therefore shape the outcome of a decentralisation process. Nevertheless, a regime can significantly influence, manage, and control these socio-political dynamics via elite rotation, clientelism, and patronage. In this regard, decentralisation offers new incentives for strong subnational actors to engage with the centre by expanding the basis for subnational actors to gain a position within subnational institutions. This may strengthen central ties to the periphery and thus, contribute to authoritarian upgrading. A regime may also receive domestic and international credit for holding local and regional elections, but promote competitive clientelism at the same time to lower the risk of such elections. Moreover, a decentralisation reform can be designed to incite competition and conflict amongst elected as well as non-elected members of subnational state institutions, which may eventually lead them to mutually impede their power and influence in the overall political process.

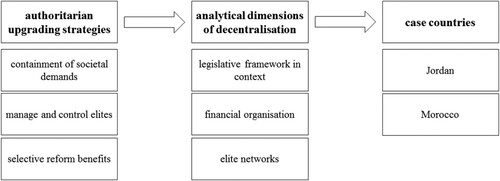

We suggest that these phenomena produce a number of reciprocal effects that – intentionally and unintentionally – contribute to authoritarian upgrading. For instance, legal changes can influence or provide incentives for local and regional actors to cooperate with the regime (Gandhi and Przeworski Citation2006), and the financial endowment of official positions can foster office-seeking motives of subnational elites and thus incorporate them into the status quo (Lust Citation2009). Our research is designed to analyse the occurrence of three main strategies of authoritarian upgrading (containment of societal demands; management of elites; gains of selective reforms) in three key dimensions of decentralisation reforms (legal framework in context; organisation of fiscal decentralisation; (re-)structuring of elite networks) in the two cases of Jordan and Morocco (see ).

Our argument draws on fieldwork in Morocco (April 2018–May 2018 and October 2018–December 2018) and Jordan (April 2018–May 2018, October 2018–November 2018 and January 2020–February 2020) where we conducted semi-structured interviews (n = 98) with politicians and state employees, civil society actors, researchers, journalists, and foreign observer organisations on the central, regional, and local government levels. We employed clusters of open questions in three blocks relative to the three analytical perspectives presented above. Since the interviews were conducted in an authoritarian environment, the safety of our interview partners has priority. Though decentralisation is not per se a ‘hot topic’ in relation to security interests of authoritarian regimes, special care is important when dealing with state-elite relationships, discrepancies between the text of laws and their implementation as well as country-specific red lines (for example the decentralisation process in Morocco is strongly connected to the king, the unsolved Western Sahara question, and even the protest movements in the northern Rif region). We thus decided to not specify the date of the interviews and the position of the interviewees.Footnote2

Decentralisation in Jordan and Morocco

The systems of subnational governance and administration in Jordan and Morocco show substantial differences. The Kingdom of Jordan had engaged in an ongoing reform process since the 1990s, which received an additional impetus after 2011 (Ryan Citation2018). A broad public debate on decentralisation, however, did not arise until 2005, when King Abdullah II officially announced plans for a decentralisation process (Ranko et al. Citation2017). The Law on Decentralisation finally came into effect in 2015 and two years later, following the 2017 first regional and local elections in Jordan, the new decentralised system was put in place. Jordan’s system is organised along two administrative tiers: On the regional (governorate) level, the kingdom is divided into twelve governorates, while the local level comprises 101 municipalities, including the Greater Amman Municipality (GAM). Traditionally, the governorate level functions as the extended arm of the Ministry of Interior (MoI) on the subnational level. Coordinated by an appointed governor, the governorate institutions are mainly concerned with security issues and the execution of regime decisions within its territorial boundaries. The decentralisation law of 2015 modified this system by establishing a partly elected governorate council within each governorate that is meant to contribute to its socio-economic development. In contrast, municipalities in Jordan traditionally elect a municipal council and a mayor, who operate under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Local Administration (MoLA)Footnote3 – except for GAM, which is directly managed by the Prime Minister. The law assigns several minor responsibilities to the municipalities that affect people’s everyday life, such as the construction of streets, urban planning, and waste management. As laid down by the Law on Municipalities of 2015,Footnote4 which accompanied the decentralisation law, each municipality now also has local councils within its boundaries (number and size as to be determined by the Minister of MoLA). Their main purpose is to identify the needs of their territory and to communicate them to the municipal council. However, as a consequence of this new institutional design, municipality councils are no longer directly elected. Rather, they now comprise the heads of the local councils (see the Jordanian Law on Municipalities from 2015).

During the first years after Morocco’s independence, local elites were a vital focus of the regime’s attention in order to balance out the strength of the Independence Party (Istiqlal). In the late 50s and 60s, the latter was engaged in a struggle with the monarchy over predominance in the newly established state (Clark Citation2018; Buehler Citation2018, 44–45). Today, local governance reforms are central to the regime’s reaction to widespread protests like the 20th February Movement in 2011. The advanced regionalisation process was incorporated in the new constitution of 2011 and became law in 2015 (especially the organic laws 111.14; 112.14; 113.14). Three subnational government tiers form the institutional backbone of decentralisation in Morocco as well as a form of organised participation on the national level via indirectly elected members of the second chamber of parliament. All decentralised institutions are under the auspices of the Ministry of the Interior. Decentralisation is, however, two-headed: An elected tier (directly or indirectly) accompanies an appointed tier of administrative control organs, which represents the state and the king. In 2018, the elected tier comprised 1503 municipalities (90% of which have less than 35.000 inhabitants), 63 provincial councils (rural), and 12 prefectural councils (urban), as well as 12 regional councils (until 2015: 16), whose members were directly elected for the first time in 2015. The appointed tier of decentralised institutions in Morocco forms a hierarchical chain of command that spans from the MoI down to its representatives on the subnational level: The wali controls the regions, and simultaneously governs one of the provinces and prefectures of the region. He is the nominal representative of the Moroccan king in the regions and controls the decisions of the regional council. The governors on the provincial and prefectural level hold the central position of state control as they control the provincial as well as the municipal council decisions (legal state control of elected subnational elites). The governor also controls the agents of state on the local level: The caid (rural) or pasha (urban) acts on the municipal level with close control over local security and local councils. Beneath them, the muqadeem (urban) or sheikh (rural) works as part of everyday administrative life in municipal districts.

Laws in context

To date, all decisive public service sectors in Jordan remain controlled by central state institutions, including defense, public security, economy, health, education, as well as housing and community services (OECD Citation2017). Several top-down administrative reforms implemented over the last two decades did not bring about profound change. The most recent modifications to the system came with the decentralisation law of 2015, whose focal point is the governorate level. The legislators decided not to strengthen the role of municipalities in the process because they are already only partially fulfilling their responsibilities due to their high budget deficits.

Hence, after more than a decade of debate, the core of Jordan’s decentralisation reform turned out to be the establishment of the first elected institution on the governorate level: The governorate council. These councils are involved in the process of issuing development and budget plans for their respective territory as a means to enhance the efficiency of central development projects in the periphery. Prior to 2015, the law provided the governor – as the representative of the central state in each governorate – with two councils in charge of handling the socio-economic development of each governorate: The executive council and the consultative council, both staffed with representatives of the regime. As a result, the central ministries de facto took all central state investment decisions for the governorates, such as the construction of hospitals or schools, on the basis of their personalist relations (interviews Jordan, May 2018; October 2018). The governorate institutions coordinated and executed the ministerial plans, but did not play a significant part in the decision-making process (Clark Citation2018). In the past, this has repeatedly led to miscalculated investments due to the central ministries’ personalist decisions and their lack of knowledge on the specific needs of each governorate (interviews Jordan, October 2018). With the new provisions of the 2015 decentralisation law, it is now the responsibility of the executive council and the partly elected governorate council – which replaces the former consultative council – to decide on the budget and development plans for each governorate. The main thought behind this modification is that the involvement of local actors will make the decision-making process on central development projects more transparent and thus, more effective. Although the Council of Ministers still appoints 15% of each governorate council’s members on the recommendation of the Minister of the Interior (see the Jordanian Law on Decentralisation from 2015), an elected institution on the governorate level constitutes a major change to Jordan’s subnational governance system. The kingdom now has elected institutions on all levels of governance: The parliament on the central level, governorate councils on the governorate level, and municipal and local councils on the local level.Footnote5

Nevertheless, a closer look at the legal dimension reveals instances of attempted authoritarian upgrading. The institutional changes coming with the decentralisation reform are hardly touching the existing power structures between the centre and the subnational levels of government. The presence of non-elected actors and institutions de jure and de facto limits the governorate council’s role and the legal framework sets clear limits to a broad devolution of state power. This instantly becomes obvious when looking at the heart of the reform, that is the drafting of the development and budget plans for each governorate. As laid down by the law, this task is assigned to the executive council, whose members are employees of central state institutions on the governorate level such as the directorates of the line ministries within each governorate. The executive council prepares the plans by taking into consideration local needs lists provided to them by each municipality within their territory (Law on Decentralisation 2015; Law on Municipalities 2015). The municipal councils, in turn, design these needs lists in collaboration with the local councils (Law on Municipalities 2015). After preparing the draft plans, the executive council submits the documents to the governorate council, whose sole responsibility is to discuss, and subsequently, to either approve or decline the plans.Footnote6 After the governorate council has given its approval, the central ministries take responsibility for the coordination and the implementation of the plans in cooperation with the directorates of the line ministries within the governorate, such as the Ministry of Health or the Ministry of Education, depending on the project in question. Governorate council members frequently report about the limited time frame they are given by the executive council and the governor – who is also the head of the council – in order to discuss the plans. Like this, central state representatives minimise the input of elected members and simultaneously widen the opportunities for central elites to influence the decision-making process on the basis of their personalist relations (interviews Jordan, October 2018; November 2018; February 2020). Hence, by making use of formal-legal as well as informal strategies, central control over the decision-making process on subnational issues remains dominant despite the decentralisation reform.

In addition to the already very complex layout of the decentralisation reform, the vague wording of the law leads to overlapping duties and tensions between the governorate councils and the municipalities.Footnote7 Consequently, arguments between the members of the two institutions are frequent in many places, limiting the potential for successful collaboration (interviews Jordan, May 2018; October 2018). At the central level, seven ministriesFootnote8 are involved in the decentralisation process and even the ministerial staff appears to be confused when asked who carries which responsibility. According to a wide range of interviews, this lack of transparency is one of the central issues that reduces the efficiency of the whole process (interviews Jordan, October 2018; November 2018). The legal framework of decentralisation thus contributes to paralysing the potential power of subnational institutions. In response to many complaints articulated by members of the governorate councils, activists, and observer organisations, a new legislation that unifies both, the decentralisation law and the municipality law, shall increase the efficiency of decentralisation. Thus, in February 2020, a draft law was submitted to parliament for discussion. However, if implemented in its current status, the effect of the new law on subnational autonomy will be marginal. Rather, it will further increase central control over subnational institutions (Karmel and Bohn Citation2020).

The Moroccan experience shows important similarities to the case of Jordan, though a major difference is that decentralisation builds on a long tradition of local governance reforms and a political vision relevant for national unity. It is central to the country’s approach toward the Western Sahara conflict. The heart piece of Morocco’s 2015 reform stems from the political project of advanced regionalisation (régionalisation avancée) that started as a strategy to increase international support for Morocco’s claim on the Western Sahara through enhanced regional autonomy (in a sense, selective gains of reform). Similar to Jordan, a strong focus on the regional level is the consequence. Although all three subnational levels were subject to reform in 2015 (lois organiques 111.14; 112.14; 113.14), the direct election of regional councils and new descriptions of competences for the regional level (vast though very broad) were core features of the reforms. The region is now responsible for economic development, (vocational) training, rural development, regional transport planning, culture, and environmental protection. The regional areas of action are wide though not very precise, especially since more competences can be transferred from the local level. The latter include the energy and water sectors as principal responsibilities of the municipalities. Procedures on interactions and cooperation, however, remain vague.

For Morocco, this is a shift away from the reforms’ traditional orientation towards the local level – and possibly at the cost of municipal influence. The vast competences of the regions after the 2015 legislation rival the competences of some municipal actors. Though no formal right of command between the different councils exists, this might change through the principle of subsidiarity established in the new constitution and in organic laws: The principle places state tasks at the lowest possible administrative level. The higher tiers of local government or the central state ‘inherit’ the responsibilities if a successful implementation cannot be guaranteed by the lower level. Subsidiarity is formally an autonomy-friendly provision, but it relies on sufficient funding for the decentralised institutions and on managerial training of the councillors. If these conditions are lacking, the influence of the lower-level councils diminishes. Furthermore, it remains unclear in the legislation if the lower or upper government tiers have the competence to invoke the principle.

Local councillors feel threatened by these changes, and the reforms have the potential to demote municipalities to more heteronomous institutions influenced by the broad strokes of regional development decisions (Bouabid and Iraki Citation2015; Houdret and Harnisch Citation2019, 17; interviews Morocco, May 2018; November 2018). Therefore, the reforms have the potential to control the opposition and other elites by creating competition between different institutions as a feature of authoritarian upgrading. These effects became even more significant as another important element of the legislative framework remained incomplete: the formal end of the principle of tutelle. The ‘stewardship’ of the agents of the state vis-à-vis the elected councils was – though mellowed by subsequent reforms over the last few decades – a strong ex ante control over local governments. After the 2011 constitutional reform and the 2015 reforms, this control mechanism is now mainly an ex post instrument: Strong formal veto powers by the administration persist, but are now put in place not before but after council decisions in order to guarantee their legality and compatibility with state security. This is a reaction to societal demands for good governance and against the corruption and dominance of ‘the administration’. In theory, the independence of subnational elected councils thus has greatly improved. However, strong de jure control remains and the de facto dominance of MoI representatives is reportedly unbroken – especially in rural areas where council capacities are weak (interviews Morocco, April 2018; May 2018, November 2018; December 2018). A new charter on administrative deconcentration was – after a long delay and heavily advocated by the palace – passed in December 2018. This new reform is presented as the next evolutionary step in the Moroccan regionalisation process. However, above all it is concerned with the creation of ministerial subnational branches in the regions and their relationship with the wali. The law’s impact is still unclear, but it refers more directly to increasing the efficiency and capacity of central state authority on the ground. This holds the danger of side-lining subnational councils. The authorities frame the new deconcentration approach as a way to appease core demands of the populace (increase of state efficiency, development, etc.) but it likely does not empower the (in-) directly elected representatives.

Overall, Morocco’s current reform process has produced – although with some delays – a relatively broad legislative framework for decentralisation, which is advanced compared to the Jordanian law. Nevertheless, in both cases subnational governance remains under strong central supervision in order to guarantee a controlled decentralisation process that does not seriously challenge the status quo.

Fiscal policy

In Jordan, one of the main reasons for the decision in favour of a more decentralised governance system was to overcome the unequal distribution of public investments to the periphery. As already discussed above, before 2017 it was the central ministries who decided on the amount and frequency of capital projects to the governorates. Over the decades, the overwhelming majority of public investments thus went to Amman, the capital and economic centre of Jordan, which is dominated by a Palestinian population (Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities Citation2005). In order to appease the Transjordanian population, the remaining budget for central investments privileged rural regions with a majority Transjordanian population such as Karak and Ma’an, thereby neglecting urban centres like Zarqa and Irbid with a more heterogeneous population and a high percentage of Palestinians (Clark Citation2018; Ministry of Finance Citation2017). In order to improve transparency, the decentralisation reform of 2015 assigns a fixed budget to the governorate level for each year, which is partitioned between the 12 governorates according to a specific calculation including socio-economic factors (Ad-Dustour Citation2017). For the first fiscal year of 2018, the General Budget Department (GBD) provided a total of 222.9 million JD (314.1 million U.S.-Dollar) – a 3% share of the general budget (General Budget Department Citation2018). Fixed guidelines for the budget calculation of each governorate is a positive development as reaction to societal demands expressed in the 2011 uprisings and afterwards. However, although the law describes them as ‘legal personality with financial and administrative independence’ (Law on Decentralisation, Article 6), the governorate councils are not authorised to manage and spend their budget autonomously. Until now, the line ministries and their directorates in the governorates manage everything related to budget expenditure and the implementation of the development projects (Ministry of Finance Citation2017). Central control over subnational spending thus remains prevalent and subnational elites are dependent on cooperation with the regime in order to fulfil their role. Moreover, since 2017 only a small number of projects was actually implemented. For instance, for the fiscal year of 2018, 20 million JD (28.2 million U.S.-Dollar) were allocated to the governorate of Zarqa, the third largest governorate in Jordan. However, only around 2 million JD (2.82 million U.S.-Dollar) had been spent on the projects of the governorate throughout the entire year (Karak Castle Center for Consultation and Training Citation2018). Governorate council members report about central ministries frequently bringing the projects to a halt by withholding the payments for the contractors or by simply refusing to start with the implementation. In addition, because the procedure follows a zero-based budgeting method, the completion of all projects that have not been fully implemented until the end of each year has to be financed with the budget of the following year, thus significantly cutting down the governorate council budget (interviews Jordan, October 2018; November 2018; February 2020). Nevertheless, the new mechanism of distribution also shows positive implications: Regions of less socio-political influence or with a history of strong oppositional work such as Tafilah, who had been disproportionately neglected by central investments for decades, are now experiencing a (tiny) socio-economic boost with the development projects (interviews Jordan, February 2020).

The regime’s official argument for Jordan’s surprisingly cautious steps towards fiscal decentralisation is the need to prepare the governorate councils prior to taking further steps towards their autonomy (Ministry of Finance Citation2017). This is linked to a distrust of the municipal system in Jordan. The municipalities’ reputation began to erode in the late twentieth century due to high levels of corruption, their incapability to fulfil their role as local service providers, and their failure to respond to the needs of the broader public as a consequence of strong clientelist networks (UNDP Citation2017). In contrast to the governorates, municipalities have at least some autonomy over their budget. Most of their budget comes from government transfers (50% of the fees and taxes on oil derivatives, 40% of the fees on vehicle licenses, Law on Municipalities 2015). Due to their largely inefficient system of tax collection, the MoF performs this task on behalf of most municipalities (Hallaj et al. Citation2015; OECD and UCLG Citation2016). In total, the municipalities receive an average 15% share of the yearly state budget (Ababsa Citation2013). In addition, the law permits the municipalities to collect local fees, the tax on property, and building permits within their territory. For every expenditure that exceeds 5000 JD, however, the municipality needs prior approval of the ministry (Clark Citation2018). Despite these provisions, municipalities are suffering from chronic budget deficits as they spend up to 80% of their budget on staff – the price of a clientelist and kinship based electoral logic – which leaves them with about 20% of their budget to fulfil their actual duties as defined by law (Hallaj et al. Citation2015). According to the official discourse, the legislators aimed at preventing similar developments on the governorate level by providing the governorate council members with enough time to adapt to their new role before putting them in charge of budget expenditure (interviews Jordan, October 2018). Regulations like these hold up strong central control while simultaneously orchestrating a widening of subnational financial autonomy.

The post-reform financial endowment of local governments in Morocco tells a story similar to the Jordanian experience, even though the progress and level of financial decentralisation is more advanced. The total Moroccan subnational government spending amounted to 4.2 billion U.S.-Dollar in 2018. In 2010, before the Arab uprisings, the kingdom spent 3.4 billion U.S.-Dollar on subnational governments. In the year of the principal decentralisation legislation in 2015, subnational expenditure had already risen to 3.7 billion U.S.-Dollar.Footnote9 A will to increase the financial capacities of subnational institutions is detectable.

Nevertheless, local and regional governance on all levels remains highly dependent on central government transfers even after the latest reforms: The regions were ‘upgraded’ by symbolism (régionalisation avancée as core frame of Moroccan development and democratisation), increased democratic legitimacy and new competences. Yet, the bulk of subnational governance spending (and income for that matter) is located at the local level. Two thirds of subnational governance expenditure were local in 2018, only 17% regional. The budget of the regional council of Casablanca-Settat (2016: 36.7 million U.S.-Dollar), though by far the largest among the Moroccan regions, is not even a third of the city of Casablanca’s (2018: 115 million U.S.-Dollar) (Tafra Citation2017, 13; 17). Therefore, the vast new competences of regional elected elites are of little consequence, as the relative lack of funding impedes their effective implementation.

Still, this marks a shift of attention from the municipalities towards the regional level. Before the Arab uprisings and the following reform steps, the regional level received only 7% of the state funding transferred to subnational entities (Ojeda García and Collado Citation2015, 54).

The disparities between urban and rural areas remain high: In 2015, more than half of the total expenditure was attributed to urban municipalities, and only 22% to the rural ones (Trésorie Générale du Royaume Citation2015). A redistribution of the already tight finances is unlikely to sufficiently back up the change of course introduced by the legal framework of the regionalisation reforms.

At first glance, the municipalities’ dependency on central funding – as an indicator of its independence – is relatively moderate in comparison to the other levels: In 2018, an average of 52.5% of municipal resources were central transfers. The regional budgets depended on the central state for 91.3% of their funding, the provincial level for 94% (Trésorerie Générale du Royaume Citation2018). The dependency of regional funds on the central state even increased since 2015, which is the year of the most profound reform (then 70% transfers) (Trésorerie Générale du Royaume Citation2015). However, as in Jordan, disparities between urban and rural areas are obvious. The National Treasury reported an average of 44.7% of central state transfers to the budgets of urban communities in 2015, while the rural mean was 77.7% – even slightly higher than the regional score (Trésorerie Générale du Royaume Citation2015) – newer statistics stopped disaggregating those indicators.

Therefore, the financial autonomy of all subnational entities in Morocco is low. Only some urban metropoles generate a significant portion of their funding from their own income (mainly business and habitation taxes as well as service fees) (Tafra Citation2017, 13). The budget plans of decentralised institutions are still subject to (ex post) approval by the agents d’état. Therefore, subnational councils under the current state of reform likely feel compelled to cooperate with the authorities. This reinforces co-optation and the management of co-opted and oppositional elites as an element of authoritarian upgrading.

Consumption costs also bind vast resources in the cities and villages (35.5% of its funds spent on staffing and 37.1% on equipment). This diminishes the autonomy of the local level, although especially the staffing costs are low in comparison to the percentage spent in Jordan. The provincial and regional councils are almost entirely dependent on national transfers and all three tiers of subnational entities are under strict financial control. The regional staffing is extremely limited (2.4% of regional funds), which causes problems with the implementation of regional policies and projects (82% of the funds are for investment) (Trésorerie Générale du Royaume Citation2018). Prestige projects of national importance are still solely implemented in multi-level cooperation under the dominance of the central ministries or the palace.

In both kingdoms, financial decentralisation is still far from guaranteeing independent and sufficiently funded execution of subnational tasks by local or regional representatives. Yet, the extents of this shortfall vary considerably between the two cases. Subnational financial autonomy in Jordan is severely limited, which puts into question the seriousness of the regime’s intention to decentralise. The Moroccan regime enhanced fiscal decentralisation progressively since 2011. However, the strong supervision by the MoI and financial planning that depends on central state transfers represent strict central control mechanisms.

Elite networks

Municipal councils in Jordan originate from the Ottoman municipal act of 1877 (Fraihat Citation2016). As part of the state building process in 1921, they were integrated into the Emirate of Transjordan. In the early twentieth century, the councils enjoyed full autonomy over their territory and high levels of legitimacy as elected institutions. Back then, they represented the traditional inhabitants of the area, the Transjordanian tribes, which have since been the backbone of the Hashemite’s rule (Alon Citation2009). Although the tribes have lost most of their autonomy to the centre over the years and the influx of Palestinian refugees has further complicated the picture, until today, mayors and municipal councils remain significant institutions that respond to their local population’s needs (Alon Citation2009). Thus, ever since their establishment, local elections have offered a playground for subnational elites because the membership in a municipal institution entails a certain degree of authority as well as the possibility to actively influence small-scale local politics. In addition, membership increases the chances of reaching higher positions in the administrative state apparatus and it opens up opportunities to get in contact with other high-ranking officials and representatives of the regime, e.g. the governor (muhafiz) or the district manager (mutasarrif). Over the last few decades, the Jordanian regime has been using this network to manage and control socio-political dynamics on the subnational levels (Al-Husban Citation2005).

The national elections of the Members of Parliament (MPs) follow a similar personalist logic. Although exceptions continue to exist, MPs represent influential tribes and families just like the majority of municipal council members do. Thus, MPs rather function as local service providers to their constituencies than as important watchdogs that monitor the government’s performance. This definition of their political role happens at the expense of political parties, whose relevance suffers from such a personalist system (Al-Attiyat, Shteiwi, and Sweiss Citation2005). Competitive clientelism is thus an integral element of Jordanian politics. In fact, one of the motives for the decentralisation reform was to break up this situation. According to official regime channels, the plan is to gradually transfer central responsibilities down to the governorate councils over the next few years. Jordanian officials expect this to reduce the MPs’ status as local service providers and to enhance their role in the overall political and law-making process (Kandah Citation2017).

De facto, the situation is moving into a different direction as of now. With the establishment of a (partly) elected institution on the governorate level, Jordan’s decentralisation reform offers an additional platform for subnational elites to compete with each other for influence. The first governorate elections in Jordan took place in August 2017. Jordanian authorities purposely scheduled the municipal council elections for the same date, because they feared voters would not take the governorate council elections seriously. Still, the voter turnout was relatively low with 32%. Dashing international and civil society organisations’ hopes that governorate elections would bring more diversity into the subnational governance system, independent tribal candidates won the great majority of seats (up to 85%) (Al Bawaba News Citation2017). Responding to the new incentives offered to them by the decentralisation reform, in many locations the elections further strengthened the same Transjordanian tribal structures that mirror those on the central level – thus offering new possibilities for cooptation on behalf of the regime. Both, voters and candidates, mostly perceived the governorate council elections as one more opportunity to extend their personalist networks. Despite that, the second biggest winner of the elections was the Islamists with the Islamic Action Front (IAF) as their most significant party (Al Bawaba News Citation2017). In the past, the Jordanian regime has often seised the opportunity to coopt oppositional actors whenever they had reached a certain level of influence and recognition. Whether the decentralisation process opens up further opportunities in this regard remains to be seen in the long run. But this incident also illustrates that a regime may not be capable of controlling all elite dynamics related to a decentralisation process.

Moreover, the decentralisation reform seems to affect the power relationship between elected institutions on all levels of government in Jordan – central, regional and local. Members of the traditional elected institutions are not hiding their discontent about this development: According to evidence from interviews, a vast majority of MPs as well as members of municipal councils are under the impression that decentralisation aims at transferring significant elements of their power and influence to the governorate councils (interviews Jordan, May 2018; October 2018). Interviewees report of frequent arguments between MPs and members of the governorate councils about their responsibilities and constituencies (interviews Jordan, November 2018). In addition, the legal framework of decentralisation as well as the presence of appointed representatives of the central state make it hard for the governorate councils to prove their new position within the administrative state apparatus. Governorates may vary on this, but elected governorate council members often complain about the amount of pressure they have to face in contrast to the appointed members. They feel directly responsible vis-à-vis the expectations of the population while 15% of the members were appointed to the council simply because of their personal networks. These 15% nonetheless receive the same salary as the elected ones (interviews Jordan, November 2018). Furthermore, candidates who ran for the 2017 election expected to obtain a high socio-political status equal to that of MPs. Thus, governorate council members were disappointed to find out that the council’s competences are de jure and de facto limited, leaving them unable to fulfil promises they had made to their voters during the election campaign (interviews Jordan May 2018; October 2018; November 2018). Empirical evidence shows that governorate council members occasionally pay for their constituencies’ demands out of their own pocket, as they are not authorised to access the governorate council’s budget (interviews Jordan, February 2020). In combination with the inefficiency of the project implementation process as argued above, this situation produces a discouraging effect on the current members as well as future possible candidates to run for governorate elections, well aware of the negative implications a position in the institution may have. Further, the relationship between governorate councils and central ministries is conflictual. Members across all governorate councils accuse the ministerial staff of not taking their work seriously (interviews Jordan October 2018; November 2018). Conflicts of interest between the governorate councils and the respective governor are also common. Governors mostly come from military backgrounds. Thus, they tend to focus on security issues instead of development plans for the governorate. Throughout 2018, several governors had to be replaced because of heavy tensions between them and the governorate council members (interviews Jordan, October 2018). This, however, is not unusual as governors are frequently replaced as part of the regime’s elite rotation system. To sum up, Jordan’s decentralisation reform has caused conflicts of interest, insecurities, and struggles between state institutions and elites on all levels of government, a phenomenon that significantly impedes the efficiency of the process.

In the last generations, the Moroccan Makhzen Footnote10 successfully managed local governance actors via appointed officials – especially the governors –, double mandates in parliament, subnational councils as incentive for local elites to engage with the central state, and the support of rural notables (Ojeda García and Collado Citation2015). The new reforms have not profoundly changed these patterns. Although its legislative framework is highly advanced in comparison to Jordan’s 2015 law, systematic deficits in elected officials’ management skills and training are observable. A rotating system of hierarchical ‘non-political’ agents of the state under the control of the Ministry of Interior flanks the elected elites. Their influence remains vast – especially in rural local councils – and it is sometimes not clear if their interference in council matters must even be considered a necessary corrective for lacking capacities (financial and human resources, management skills). Institutional failure of elected institutions is used to highlight the virtues of the palace’s supposed technocratic approach. Examples of this are the widespread rejection of the first wave of flawed regional development plans, political infighting in city councils or the suspension of the regional council of Guelmim-Oued Noun by the Minister of Interior in May 2018.

The new decentralisation framework balances elite networks and the political representation of different political levels. Direct elections and a growing focus on régionalisation avancée as the prime reform of a Moroccan-style model of development and democracy increase the legitimacy of the regional councils. Especially in the rural areas, the subnational elections were subject to intense courtship of local notables to integrate them into political party tickets (Desrues Citation2016). Official authorities reportedly also tried to influence the decisions of local notables with regard to their endorsement of political parties (Tritki Citation2015). The official turnout of the local and regional elections was relatively high with 53.7%, compared to 45% in the national election of 2011 and 43% in 2016. However, the turnout is a percentage of the registered voters, not of all eligible voters, and the number of invalid ballots is often very high in Morocco (e.g. 22.3% in 2011) (Sadiqi Citation2015; Zerhouni Citation2016).

Political parties in Morocco are politically relatively strong compared to those in Jordan and other MENA countries. As far as elected elites are concerned, political competition in Morocco takes place between the political parties but not against the monarchy. The urban-based and moderate Islamist Justice and Development Party (PJD) was widely believed to be the only ‘real’ opposition party in an otherwise co-opted party system. The decentralised elections led to widespread coalitions of so-called Makhzen parties against the PJD, thus reproducing regime-loyal elite networks subnationally. The PJD was the strongest political party in the local and regional elections of 2015. Its main political opponent, the Authenticity and Modernity Party (PAM), finished second. This royalist party keeps close ties to the regime and was established to counter the rise of the PJD. In stark contrast to PAM, the moderate Islamists tend to be underrepresented in terms of council presidents though they won every mayor position in the country’s major cities. An anti-PJD effect is also evident within indirectly elected institutions (Tafra Citation2017). PJD candidates were often successfully blocked by coalitions of other parties in the struggle for council presidencies. Those coalitions are often considered to impede ‘clear’ politics and to distort the electorate’s will (interviews Morocco, April 2018; May 2018). The vast institutional landscape of the elected tier of decentralisation is thus stronger represented by parties loyal to – or co-opted by – the regime.

This is of special importance because the Moroccan subnational councils are characterised by a strong focus on their leadership: Formal power as well as institutional practice favour the presidents as they officially execute all decisions, have a gatekeeper position, and keep the main responsibility for staffing. The reforms have increased incentives to participate in subnational institutions by increasing the executive council’s salaries on all levels – especially in the regions, where council presidents’ salaries rival those of national ministers. The increased executive dominance in all councils seems to be a viable instrument to control the oppositional potential of regular councillor without executive functions. In addition, the coalition building that is necessary to win council presidencies contributed to reinforcing regime-loyal coalitions against the PJD as (moderate) regime opposition party.

The effective powers of democratically legitimised subnational councils are also contested by civil society organisations: NGOs play a codified role in decentralisation as they participate in issuing mandatory local and regional development plans and are involved in the provision of public goods (such as water, electricity, sanitation, transport) (Bergh Citation2009, 2012). Thus, they share responsibilities with local governments. In many cases, the central state affects their funding and undertakes efforts to co-opt the civil society or council members who are also founders of NGOs (Clark Citation2018). Central state initiatives like the National Initiative for Human Development (INDH) condition their assistance on the acceptance of the rules of the game and thus promote the benefits of non-political or pro-regime associations (Bergh Citation2012; Clark Citation2018). This is a mechanism to disperse power and responsibilities between a plurality of political and non-political elites. It both enlarges the circle profiting from state funding (i.e. co-optation) and increases the obstacles for effective coordination amongst individual actors who could cooperate to pose potential regime threats.

Direct local and regional elections improve the opportunities for political participation and competition in Jordan and Morocco. However, political competition replaces clientelist networks only to a very limited extent. Additionally, in both kingdoms the dominance of the administration over elected elites remains strong – even after the decentralisation reforms.

Conclusion

The scholarly debate has led to substantial contributions on the international and national dimensions of authoritarian upgrading, but subnational aspects of the phenomenon remain largely unexplored. This article aimed at contributing to this discussion by shifting the focus on the importance of subnational politics for authoritarian regime durability. We modified three main strategies of authoritarian upgrading (containment of societal demands; management of elites; gains through selective reforms) to make them applicable for the analysis of three key dimensions that are salient for the implementation and outcome of decentralisation reforms in MENA countries (legal framework in context; organisation of financial decentralisation; (re-) structuring of elite networks).

The ongoing local governance reforms in Morocco and Jordan since 2015 provided fruitful instances for some initial empirical conclusions. Both decentralisation projects entail a de jure empowerment of the regional vis-à-vis the local level by either establishing (Jordan) or strengthening (Morocco) elected institutions on the regional level. In addition, both reforms further expand subnational financial capacities. At first glance, this seems to constitute an important step towards a strengthening of the subnational levels of government in each country. However, the reality is more complex and several aspects indicate that the reforms rather contribute to authoritarian upgrading. With the reform processes ongoing, both regimes seem to profit from the benefits of the reforms without taking the risk of major substantial institutional changes and a loss of central control in the periphery. Initial empirical insights reveal the reforms’ potential for the regime to engage with and contain societal demands and to manage elite circles on all levels of government. Surprisingly, significant economic or administrative gains of the reforms seem to be largely absent by the time of writing, except for an extensive engagement of international organisations and NGOs in the process.

Despite the official narrative, the scope for decentralisation in Jordan remains limited. The analysis of the legal aspects of Jordan’s decentralisation project has shown that although the new framework grants additional possibilities for participation on the governorate level, subnational autonomy lacks substantial administrative, financial, and executive powers. Even after the reform, the laws allow the Ministry of Interior, the Ministry of Local Administration, and other central state actors to closely guide and monitor the councils’ work. In addition, the vague wording of the laws spark competition between institutions on all levels, including governorate institutions, the municipalities, and parliamentarians. This creates an equilibrium that avoids contesting the power of the centre and thus contributes to authoritarian upgrading. Morocco’s 2015 reform is more advanced. A significant extension of regional competences and their formal execution by directly elected regional councils indicates a big step towards subnational empowerment. However, similar to Jordan, this has also led to uneasy reactions by members of municipalities who are now feeling subordinated to the regions. In theory, the reforms eased the traditionally strong and sophisticated administrative control by representatives of the Ministry of Interior, but their de facto impact remains strong in the sense of authoritarian upgrading. In both cases, the analysis indicates that the reforms are perpetuating the status quo and thus, strong central control over subnational institutions. Formal regulations contribute to preventing a serious challenge to the centralised grasp on power.

Despite the reform of 2015, subnational financial autonomy in Jordan remains limited. Subnational institutions are largely dependent on government transfers and the central ministries still manage and monitor everything related to budget generation and expenditure. The law moved the decision-making process regarding large governorate projects closer to civil society, but the power to regulate the implementation and financing of the projects remains with the ministries. Nevertheless, governorates of less socio-political significance or with a high record of oppositional activity are now experiencing a minor – yet noticeable – economic and developmental recovery after decades of being neglected by central state investments. Morocco holds the highest degree of fiscal decentralisation within the region and the regime further increased subnational funding since 2011. Consumptive costs are high, but still low in comparison to the Jordanian case, granting subnational actors more leeway in their decision-making. If this positive development continues, subnational service provision and efficiency might increase in the long run. However, financial decentralisation in Morocco is also characterised by a close monitoring process via central state institutions. Moreover, all political levels are heavily dependent on government transfers. Only a few major metropoles enjoy a certain degree of financial independence. The upgrade of the regional level’s role and competences are not sufficiently mirrored in the reform’s fiscal outline. Regional dependency on central government transfers has increased after the reforms and tight staffing impedes the potential for an autonomous implementation of projects. The de facto strong supervision by the Ministry of Interior represents strict central control mechanisms for the implementation of reforms. Overall, in both kingdoms the regime maintains control over subnational financial affairs even after the reforms of 2015.

In both cases, direct local and regional elections increase the potential for political participation and competition without seriously challenging the status quo. With a few exceptions, Jordan’s election results for the new governorate councils of 2017 further strengthened the already existing, mainly tribal-based clientelist networks that mirror the elite structures of the country. Furthermore, members of elected institutions on all levels of government are now in competition for influence with each other and are thereby mutually impeding their potential power. In Morocco, even after the extensive decentralisation reform of 2015, the tradition of political tutelage by the administration over subnational elected elites prevails, and it is likely that this will not change for a while. A frequent and well-intended inclusion of NGOs increases the already strong linkage of political, administrative, and central actors and thus leads to a diffusion (or even confusion) of subnational responsibilities. Scandals, failures, and a disdain for politics are used to frame the monarchy and state representatives as necessary correctives in the political process.

The regimes hijacked public demands for more political inclusion and transparency by applying top-down reforms that simultaneously widen and limit the competences of the subnational levels of government. Like this, decentralisation reforms were used to appease and contain civic aspirations and demands without losing central supremacy on the subnational levels. At the same time, international donors appreciate and support the decentralisation projects in their conformity with international demands for decentralisation of power and good governance. However, reforms may have helped to appease protesters and threats from the periphery for a while, but continuing public discontent and protest movements question the sustainability of civic containment if the regimes only implement incremental change. Furthermore, in both cases the reforms created new incentives for elites – even oppositional ones – to engage with the rules of the regime. New positions in state institutions with formal democratic legitimation and access to state resources foster competition among subnational elites. Moreover, a potential drive for change is hindered by a vast fiscal dependency of decentralised institutions on central state transfers, the enduring de jure and de facto control on behalf of the centre, as well as by the strong presence of subnational elite circles that are primarily mirroring central elite compositions. So far, the implementation of decentralisation reforms in Jordan and Morocco contributed to authoritarian upgrading rather than an empowerment of subnational autonomy in the sense of western donors’ and civil society activists’ expectations. In turn, this development may as well be part of the reason for the absence of distinct reform benefits such as economic development, administrative efficiency, or decreasing corruption rates. Similar characteristics in African decentralisation experiences (Aalen and Muriaas Citation2018) hint towards a more general applicability of our findings. However, Jordan’s and Morocco’s decentralisation reforms are strongly characterised by a monarchical state structure. Prior research already suggests a ‘monarchical exceptionalism’ concerning durability, legitimation strategies, and elite structures (Bank, Richter, and Sunik Citation2014; Derichs and Demmelhuber Citation2014; Kailitz and Stockemer Citation2015). It would be desirable for future research to examine (1) the strategies of authoritarian upgrading employed in other MENA regimes’ decentralisation processes and (2) possible similarities and differences between authoritarian monarchies and other non-democratic regime types for that matter.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to Julia Zimmermann for her research assistance as well as Katharina Nicolai and the participants of the ECPR Joint Session Workshop ‘Authoritarianism beyond the State’, Mons, 8–12 April 2019, for their helpful comments on earlier versions of this article. We are also indebted to the two anonymous reviewers for their excellent and constructive suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Heydemann (Citation2007, 5) further suggests the control over new communication technologies and the diversification of international linkages (e.g. fostering ties to countries that are not interested in the democratic condition of its partners) as features of authoritarian upgrading. For the purpose of this article, those are only of subordinated interest.

2 We recommend the work of Glasius et al. (Citation2018) for an extensive discussion of obstacles and techniques during fieldwork in authoritarian environments.

3 In the course of a cabinet reshuffle in May 2019, the former ‘Ministry of Municipal Affairs’ (MoMA) was renamed ‘Ministry of Local Administration’ (MoLA) (Al Bawaba News Citation2019).

4 The first Law on Municipalities was introduced in 1955. Since then it was revised several times, the latest being the Law on Municipalities of 2015.

5 For a more detailed discussion, see Karmel and Bohn (Citation2020).