ABSTRACT

The musical dimensions of the Moroccan Protectorate invite us to rethink certain tenets of colonial history, especially lingering nineteenth-century attitudes about ‘indigenous’ populations as ‘savage’. By the mid-twentieth century, efforts to comprehend Moroccan music were far less motivated by domination and submission than other agendas, beginning with ‘cultural protection’ to justify French presence, the Protectorate's priority since arrival. Publications and promotion of Moroccan music reflected French desire for long-term impact on the region. This enterprise depended on Moroccan as well as European support, addressing local needs and creating alliances with both urban and rural elites with their own political agendas. Offering archival evidence of the French Protectorate's institutional involvement in renovating Andalusian music – never before examined, yet so important in post-colonial Moroccan identity – and, despite colonial occupation, Moroccan musicians’ agency, this article focuses on the interactions between French administrator Prosper Ricard, Algerian-born musician/ethnographer Alexis Chottin, and Moroccan musicians equally concerned about their music's future. Many are here given voice for the first time. Drawing on these stakeholders’ expertise and experiences, they co-created new musical knowledge despite power asymmetries, sustained the musical practices of urban and rural populations, and encouraged traditional, hybrid and modern identities. In their newly-created Conservatory of Moroccan Music, music festivals, and Radio-Maroc, relationships shaped through shared responsibility for outcomes emerge as significantly more complex than between ‘superiors and subalterns’, reaching parity at the Fez festival (1939). Their multifaceted work continues to influence knowledge and praxis today. To understand this requires a new paradigm for colonial scholarship.

Today, who would imagine that two volumes on Moroccan music – published in 1931 and 1933 by a French settler, Alexis Chottin – take up more than a foot of bookstore shelf space in Rabat? () As a local professor of ‘Andalusian music’ recently explained to me (Harrate Daoudi Citation2016), these are still being studied and taught in Moroccan conservatories, especially the musical transcriptions. They document the voices and music of some of the most important musicians of the colonial period, inaccessible elsewhere. Given such demand, a facsimile version from Casablanca appeared in 1987, reissued numerous times through 2012. An Arabic translation of Chottin's magnum-opus, Tableau de la musique marocaine (1939), is currently underway. Similarly, Moroccans continue to consult the work of his collaborator, the colonial administrator Prosper Ricard, who commissioned, directed and prefaced Chottin's Corpus de musique marocaine. Ricard's multi-volume Corpus de tapis marocains (1923–1934) was republished between 1975 and 2001, digitised in 2020.

Ongoing interest in this research years after Moroccan independence (1956) suggests that the colonial heritage lingers on when Moroccans consider this legacy useful. In the political sphere, alongside the ongoing, contentious conflict over what language should dominate classrooms after ‘arabisation’ of the educational system in Morocco began in the 1980s, the Parliament on 22 July 2019 returned to allowing foreign languages (principally French) to be taught, especially in sciences and technology. Proponents argued for its utility: French still dominates professional life in Morocco and is believed by some as better suited in these domains than Arabic or Amazigh/Tamazight (earlier referred to as Berber) (Amrani Citation2019). On 18 September 2019, following the King's ‘directives to protect cultural heritage and preserve historical monuments of the kingdom’, the Ministry of Culture allocated 11 million MAD ($1,140,500) to renovation projects, such as the medieval Chellah, a Muslim necropolis built on a Phoenician site and an ancient Roman colony (Hatim Citation2019). Restoration of its mosque began under the Protectorate in 1915.Footnote1

If we wish to understand better the impact of the colonial past, we need to return to history but not, the Algerian historian Mohand-Amer implores, as ‘instrumentalisation of the past’ for today's political or ideological ends. Rather we should be looking for ‘blind-spots’, examining history's local and individual dimensions. Turning away from mythologies that have shaped conflicting memories of the colonial period, he calls for greater access to archives in North Africa, more scientific methodologies, and ‘less dependence on issues of power and ideology’ (Citation2020, 36–37, 41; Citation2021).Footnote2

This article addresses Mohand-Amer's concerns. It focuses on musical practices (rarely of concern to historians), individuals, and local ‘mechanisms of colonialism’, contesting contentions that they were dictated from the metropole and settlers inevitably ‘denigrated’ the colonised as ‘incomplete and atavistic’ (Trumbull IV Citation2009, 149) and claimed ‘a monopoly of knowledge and technical skill’ (El Mechat Citation2009, 13–22). Such assumptions have led to silencing North African voices and denying the importance of their contributions. Reiterating Laâbi's Citation1966's ‘call for rediscovery of our heritage’, it draws attention to Moroccans’ participation in the production and advancement of musical knowledge under colonialism, many here given voice for the first time, thanks to little-known sources and Ricard's extensive archives, recently acquired by the Archives Nationales du Maroc (ANM). We also learn here that what is now known as Arabo-Andalusian music grew and thrived under the Protectorate, expanding from the private salons of Andalusian descendants to the public sphere. While rooted in the pre-colonial past and contributing to a distinctive identity later embraced by nationalists (Shannon Citation2015, 90), this music was not, in general, a ‘marker of cultural resistance’, as Marouf (Citation2014) posits, rather of cultural cooperation. Some have concluded that the concept of ‘Andalusian music’ itself arose under colonialism, signalling connections with medieval Iberia (Shannon Citation2015, 95–96). Writing of this in colonial Algeria, Miliani Citation2018 importantly asks, ‘Who is the legitimate protector’ of this musical heritage, ‘its practitioners or those who value it?’

To address these paradoxes, I examine colonial cultures as what the Caribbean poet-philosopher Edouard Glissant calls a two-way ‘Relation’ wherein native and settler populations were mutually, if unequally, transformed. As he points out, ‘decolonisation will have done its real work when it goes beyond’ notions of identity as ‘primarily ‘opposed to’ the coloniser. Every identity is ‘extended through a relationship with the Other’, every Relation ‘newness’ (Glissant Citation1997, 11, 17, 177). Methodologically, this article follows in the tradition of scholars who argue similarly that history is the study of ‘organic relationships’ (Chikhaoui Citation2002, 17) and coloniser and colonised were ‘mutually shaped in intimate engagement’ (Cooper and Stoler Citation1997; Cooper 2005). In Moroccan craft culture, Irbouh Citation2005 acknowledges that ‘reforms emerged from a negotiated process’ and ‘new alliances’ between French and Moroccans. To understand this ‘variegated reality’, he advises ‘analysis’ over ‘advocacy’. However, without examining the Protectorate's considerable archives, now at ANM, Irbouh was unable to identify those who participated in such alliances and the nature of ‘political cooperation’ that enhanced ‘stability and order in the medinas’ (22, 54, 68). In this article, I show how musical practices enabled and embodied such relationships, more complex and unpredictable than ‘the dichotomy of superior and subaltern’. Like post-colonial Moroccan critic Khatibi, I prefer ‘the risk of plural thought’ to binary oppositions (Rice Citation2009, 116). Close study of these archives has allowed me to document not only the actions of French settlers in a domain long ignored by scholars, but also, significantly, the power, agency and contributions of specific Moroccan musicians, despite whatever conditions were imposed on them.

The Relations here discussed anticipated those dominating applied research on knowledge production today, from science and technology to climate change, health and other public services. Such research not only acknowledges multi-faceted contextual issues, but also involves dynamic interactions with local participants, addressing what is relevant and important to them. That is, ‘partners recognise that the key change agents are not the programme ‘makers and shakers’ and the strategies they introduce, but rather the agents on the ground and how they respond to the opportunities afforded by the programme’ (Heaton, Day, and Britten Citation2015, Table 1). I have found similarly that whereas, traditionally, knowledge-producers rarely involve those who ‘commissioned, provided, or used’ their work, Ricard, Chottin and Moroccan musicians came together as policy maker, scholar and practitioners to co-produce musical knowledge.Footnote3 What linked them was concern for and interest in the future of Moroccan music.

Table 1. Hybrid Concerts in Morocco (1936–1938).

To understand what the Moroccan Protectorate wished to accomplish with music, we begin with its cultural agendas, especially ‘cultural protection’ of the Moroccan heritage. How did it come to be, for example, that the 2011 Moroccan constitution included the Andalusian tradition as integral to current North African national identities?Footnote4 Scholars have written excellent studies seeking to explain al-Ala, some delving into its origins (e.g. Shiloah Citation1995; Guettat Citation2000; Davila Citation2013; Chaachoo Citation2016; in Morocco, Aydoun Citation1995; Cherki Citation2011).Footnote5 Without addressing this under colonialism, Chelbi Citation1985 in Tunisia and Bouzar-Kasbadji Citation1988 in Algeria have suggested that music and political history should be understood as ‘mutually constitutive’. Glasser (Citation2016) and Miliani (Citation2018) studies of revival efforts in Algeria have largely left aside their colonial implications.Footnote6 Guettat (Citation2000) presents Tunisian efforts in the 1930s to ‘save this music, ‘revalorise’ and ‘spread it’, as if resisting French policies rather than echoing them (240–241). Likewise, under the Moroccan Protectorate, Chottin and Ricard played important roles in the study, promotion, and dissemination of Andalusian music. For this, they drew support from elites sharing interest in its renovation. We need to understand better the relational nature of French and Moroccan investments in this tradition and how it came to unify the country and connect Moroccans with other North Africans.

To further reinforce Laabi's Citation1966's ‘call for rediscovery of our heritage’, I also examine the Protectorate's support for publications, performances and recordings of other musical traditions, likewise largely left out of post-colonial discourse. Through these, Chottin and Ricard drew attention to the diversity of Moroccan music – Black, blind and female musicians; dancers, actors and clowns; amateurs as well as professionals from throughout the country, none more important, from a colonial perspective, than rural Chleuh. After catastrophic losses from war in the northeastern Rif mountains (1925–1926) and the widely unpopular 1930 Berber Dahir that legally separated Berbers from Arabs, the French sought to ‘win souls’ through ‘peaceful’ means. But, to subordinate the rest of the country by 1934, they cozied up to the Glaoui family (al-Glāwī) of Chleuh descent, which dominated the Atlas region. In return for siding with the French, this clan obtained free reign to exert tyrannical power there, fanning its political ambitions. Chottin's and Ricard's engagement with Chleuh music and dance took place in this context, arguably far more important than Chleuhs’ tourist appeal. Their work, lying at the crossroads of musical currents in mid-century Morocco, serves as historical testament to who was given voice, in what contexts, and for what purposes, from military domination before 1934 to recognition of rural Berbers as integral to the nation thereafter.

Ricard, Chottin and Moroccan musicians facilitated the co-production of knowledge as ‘plural thought’ through collaboration.Footnote7 While we cannot examine the often invisible role played by their distinct backgrounds, beliefs, interests, strengths and motivations, archival sources document how they shared their expertise and other modes of agency, suggesting mutual respect, work toward common purposes, and, despite power asymmetries, co-responsibility for outcomes. Although a musical outsider, Ricard brought local research experience, connections with Moroccan elites, and the State's power. He had worked with artisans in Algeria before General Hubert Lyautey, Resident-General (1912–1925), lured him to Fez where, for economic and cultural reasons discussed below, he was charged with renovating Moroccan crafts. Beginning in 1920, when he took interest in Moroccan music, Ricard became responsible for informing his superiors on musical matters, making policy, giving subsidies and promoting musical renaissance. Algerian-born Chottin, who earned his living as professor of Arabic in Moroccan schools, had Western musical training, studied Moroccan musical traditions with openness and curiosity, and enacted these policies. Both pursued educational goals, seeking to attract, inform, and produce advocates among both insiders and outsiders to the Moroccan heritage. As ‘informants’, Moroccans assured the credibility of their scholarship. However, co-production of scientific knowledge is different if the sources are practitioners. Performance gives participants a voice. Moroccan musicians like Si Omar Jaïdi, Si Mohammed MBirkô, and Raïs Hadj Belaïd were highly-respected master musicians and, thus, valuable partners.

Their collaborations produced knowledge in four ways – through identities, discourses, institutions and representations.Footnote8 These involved musical practices, what Feld (Citation2015) calls ‘knowledge-in-action’, examined here in music education, concerts, festivals, recordings and radio. Such contexts provided Moroccan musicians with opportunities for self-development and access to the public sphere where they could build careers and sustain Moroccan music over time. How exactly this music evolved through such collaborations remains for specialists to ascertain, the article laying a foundation. Even if aligned with colonial agendas, their contributions to musical life offered opportunities for Moroccans and Westerners to listen to one another, itself a ‘hermeneutic act’ (Barthes Citation1991), especially in hybrid forms that allowed people, through music, to move between identities, experiencing them both. Challenging divisions within Moroccan society, Protectorate officials presented diverse Moroccan musical traditions and sought to involve ‘all classes of [Moroccan] society’ as teachers, pupils, performers and listeners (Ricard Citation1930, 28). This article seeks to help us better understand the legacy of such Relations, encouraging a multi-dimensional approach to colonial scholarship.Footnote9

Agendas of the Moroccan Protectorate

‘Cultural Protection’

In today’s focus on the domination/submission paradigm, we often miss differences from one colonial context to another and the larger agendas underlying cultural policies.

From Indochina to the Maghreb, the notion of ‘protection’ was an essential aspect of French colonial discourse and cultural action. Anxious over the impact of building bridges, ports, railroad lines and modern buildings in their colonies (Ricard Citation1931b, 3), the colonial administration wished to ‘protect’ historical monuments: they communicate, not only collective memory of their heritage, but also a people's aspirations and pride. ‘Protection’ implies intentionality, directed at achieving certain purposes, including the symbolic and the political. ‘Protection’ in a colonial context signified a paternalist relationship between coloniser and colonised that served as military and cultural justification for conquest. It implied providing something that could be perceived by the colonised as desirable. Underlying this was the Protectorate's need for recognition of the value of such ‘protection’, through the public display and promotion of its actions, to support its continued presence in the region.

As Chikhaoui (Citation2002, 18) points out, the ‘Moroccan system’ had long been based on ‘eternal return to the past to legitimise and permeate the actions of those in power’. Understanding this, soon after Morocco became a French protectorate in 1912, Lyautey, a Monarchist with an ‘absolute respect’ for religion and the ‘continuity of traditions’, created an agency charged to ‘protect and restore the Moroccan heritage’, its monuments falling apart (Ricard Citation1919b, v-vi). Placing Antiquities, Historical Monuments and Fine-Arts within the same administration, Lyautey did not seek to duplicate French ideas and institutions, but to create new ones. From 1915 to 1920, it renovated mosques in Rabat and Fez; the Sultan's palaces in Marrakech, Rabat and Fez; the famous Quranic schools (medersas) in Fez and Marrakech;Footnote10 and the Kasbah des Oudayas in Rabat, today a UNESCO World-Heritage site. In the 1920s, this included old city medinas where Moroccans lived and a law preventing European constructions that ‘compromised the picturesque’.

Since 1900, colonial administrators in Algeria had taken special interest in the history of Arab civilisation, particularly its Andalusian-inspired monuments and art, as in Tlemcen (Oulebstir Citation2005). Coming in three waves from Spain during the Reconquest, this tradition defied strict distinctions between East and West. Since the Andalusian period came to represent ‘la belle époque arabe’, protecting its traditions across North Africa became integral to French colonial policy. The deterioration of Andalusian music, as in architectural ruins, was a driving force in the French call for its protection.Footnote11 From Tlemcen, professor of Arabic and Berber in Oudja, Ben Smaïl (Citation1919, 43) advocated inclusion of Andalusian music in the project to ‘restore, reconstitute, and bring back to life architectural wonders and Arabic plastic arts’. In 1921 he created a musical ensemble, L’Andalousia (Djam’iyya al’Andalusiyya), the first of its kind in Morocco to receive public subsidy.

Two institutions, founded in Rabat in 1920, complemented this agenda: the Institute of Advanced Moroccan Studies and the Service of Indigenous Arts (SIA), an administration inspired by an Algerian precedent with no French equivalent. Under Lyautey's direction and with support from the Sultan, Georges Hardy, Director of Public Instruction, created the former as a school for colonial administrators, not following the model of learned societies in France, instead promoting ‘disinterested research’, starting with geography, history, antiquities, Moroccan medicine, language dialects, poetry and songs (Hardy Citation1920, 6) – ethnographies needed to understand Moroccans. Early members included two Algerians, Azouaou Mammeri and Ben Smaïl, and music teacher, Marie-Thérèse de Lens. The Institute produced a Bulletin, scholarly journal, Hesperis, and annual congresses.

At its first congress, Mlle de Lens addressed Moroccan music, noting that the Andalusian tradition ‘strongly influenced’ Western music during the Middle Ages and ‘shines light on the origins of our music’. But worried about the impact of Western progress, she noted that as Lully's orchestras with modern violins pushed aside the viola da gamba, the old lute and the rebab were disappearing in Morocco, played by only a few masters. After describing such instruments and transcribing musical excerpts, she asserted that, if one could form ‘perfect’ Moroccan orchestras that Europeans would admire like the old medersas, one could ‘save this music from eternal oblivion’ (Lens Citation1920, 137, 151–152).

The SIA, attached to Public Instruction, opened that year in Rabat's Kasbah des Oudayas. In some ways, its policies echoed those of ‘cultural protection’. To help Moroccan artisans thrive and compete more effectively, this administration was charged with collecting, conserving, categorising, describing useful models, and promoting these arts in exhibitions, local and foreign (DG Citation1931, 18–19, 23). Echoing nationalists’ call in 1938 to take inspiration from ‘the spirit of entrepreneurship’ and ‘hard work’ in ‘civilised nations’ (Hajji Citation2007, 236), Ricard Citation1941 notes that ‘entrepreneurs and producers’ who ‘transmit an art, a skill, a tradition, a culture’, ‘teach the meaning of and taste for work well-done, train apprentices, are disciplined and able to adapt to modern life’. In this, musicians could share much with artisans. In 1925, after approving the statutes of L’Andalousia, Hardy asked the SIA to develop an official policy to support ‘indigenous music’, in 1926 contributing 3000 francs (DG Citation1931, 27). This window of opportunity opened the possibility of research and cultural action not only for, but also with Moroccans.

Renovation in the ‘Indigenous Arts’: Prosper Ricard

Prosper Ricard (1874–1952) was trained at the Ecole Normale in Algiers and learned Arabic and Kabyle (Tamazight). Besides directing professional schools for artisans in Tlemcen and Oran, Algeria (1900–1909), he published studies of their work. In 1915, Lyautey hired him to serve as Inspector of Indigenous Arts in Fez and Meknes. On his first visit, Ricard encountered Marguerite Bel, wife of curator of Tlemcen's Andalusian museum; she had just started a project to restore the local embroidery tradition in Meknes. Inspired by her and after collaborating with Alfred Bel on a book about Tlemcen's wool industry (1913), Ricard published 15 articles on Fez's artisanal arts. In a quasi-fictional conversation with a Fassi artisan, he hinted that, underlying these publications, was his desire, however paternalist, to educate Moroccans about their own past (Ricard Citation1919a).

As SIA's first director (1920–1935), based in Rabat, Ricard aimed to encourage arts and crafts across the Protectorate. In him, ‘colonial epistemology, practice, and policy often intersected’ (Mokhiber Citation2013, 268). He not only collaborated with artisans, he shaped State policy. As political intermediary between artisans and settlers, first in Algeria, then Morocco, later Tunisia, he was responsible for articulating to both the State and the public the advantages of collaboration and investment in these industries. He aimed to bring Moroccan and French interests into alignment, with political and artistic implications for the future.

Ricard began by visiting workshops throughout the country to identify key actors and build partnerships in Moroccan decorative arts. There, he took interest in the role of geography, sex, and social status in their history, diversity and originality. Ricard made drawings of representative models as prototypes, documented and catalogued artisans’ work, offered advice, promoted employment and encouraged women's collaboration, such as when men made slippers and belts and women embroidered them (Ricard Citation1948). After opening SIA branches in Fez, Meknes and Marrakech, he created regional museums where his work samples could ‘facilitate the reeducation of adult artisans and initiate new generations to the country's arts’ (DG Citation1931, 18). In addition, Ricard assisted artisans with foreign markets, leading to stable jobs and greater professionalism.

Ricard also promoted artisans’ work widely. Beginning in 1916, publishing many accessible articles on Moroccan culture in the newspaper, France-Maroc, Ricard advocated protection and revival of Moroccan arts and crafts. He also praised Fez's magnificent architecture, Arab monuments across the country, Berber kasbahs, and Moroccan aesthetics, returning to these later in radio broadcasts. These, his lectures at the Institute (1925–1938), and articles in Hesperis laid the groundwork for his major publications and Guide bleu, in four editions by 1930. Ricard also carried his messages abroad, speaking at major exhibitions in Paris, London and Chicago.

At the same time, following the lead of Hardy and advice from Moulay (Mūlāy) Idriss ben Abdelali El Idrissi, a singer and intellectual whom he met in 1925, Ricard turned to music, the next focus of the Protectorate's cultural protection. This was a natural progression. Sometimes artisanal and musical activities took place in the same spaces, their practitioners artisans by day, musicians by night. In Algeria, the tar designated both a percussion instrument and a weaver's movement, the m’allem, a master of both apprentices and music (Marouf Citation2014, 419). Showing respect for Moroccan traditions, Ricard acquired insights into not only the interests and tastes of urban elites, but also the closed, intimate spaces of Moroccan society.

Ricard's attention to Andalusian music began in 1907 when the Algerian government sent him on a mission to study the architecture and monuments of Andalusian Spain. Later, like Ben Smaïl and Mlle de Lens, he understood that its musical tradition, as practiced in North Africa, had suffered ‘decadence’ from

lack of direction, lack of teachers, lack of appropriate instruction, lack of written documents, … and lack of generosity because the professionals, miserly and difficult to learn from, were very little interested in passing this on to others, including future competitors, and so Moroccan music became more and more impoverished each day.

Ironically, it was not modern European music that most concerned Ricard, rather the growing taste for popular song from Egypt, independent since 1922. In 1930, he explained, ‘North Africa has its eyes turned towards Egypt whose every thought, every form of art, especially music, is avidly absorbed by the North African Muslim elite, as if the only spiritual nutrition worthy of its aspirations’. ‘Foreign airs’ on recordings from the Arab world, he contended, were ‘marked by a dubious modernism and made with a commercial purpose’ from which ‘Andalusian music derives no benefit’. Ricard feared a loss of its originality, ‘an imminent collapse [of the genre] precipitated by bad use of the gramophone and the radio, adopted with enthusiasm in all Moroccan milieux’. The ‘local heritage’ risked disappearing, along with its lingering European legacy. This would justify the utility and allure of ‘recovery’ by the Protectorate (Ricard Citation1930, 92; Citation1931a, ii; Citation1931b, 10; Citation1932c, 20, 24; Pasler Citation2015).

In systematically organising his action in the decorative arts, Ricard explained, ‘collecting, conserving, and describing old works is not enough. We must produce new ones. For this, we must contact people, decide on the most capable to accomplish this’, then ‘make an inventory, study, and revive the past: such is the programme we have pursued from the beginning’ (Ricard Citation1930, 26; Citation1931b, 6, 8). Similarly, his musical agenda – teaching old airs, performing them, making recordings, and creating a Museum of Moroccan Music with instruments and poetry anthologies – would make musical renovation possible, a compelling argument for cooperation. Crucial was finding Moroccans with similar interests.

Alexis Chottin’s Musical Pluriactivity

Born in Algiers, Alexis Chottin (1891–1975) grew up around Spanish immigrants enamoured of Andalusian music. He played in the local wind-band and studied music, various instruments, and composition at Algiers’ Ecole Normale. His first teaching position was in an Arab town in Nador where he collected Kabyle songs (Chabot, de Citation1929). Moving to Morocco in 1920, he taught at Franco-Arabic elementary schools (introducing singing into the curriculum), Collège Moulay Youssef (Fez), Lycée Gouraud (Rabat), Ecole musulmane des fils de notables (Salé, beginning in 1922, as professor of Arabic and director), and later Collège des Orangers (Rabat). In 1928, he wrote the ‘official hymn of the Protectorate's Muslim schools’, Chant des jeunes marocains. During this time, Chottin devoted his spare time to studying Moroccan music. From 1923 to 1927, he collected, transcribed, and published songs from Fez. Asked to compose something for his College's awards ceremony c. 1921, he wrote two of what would later become twelve choruses for his Salé pupils, Le Muezzin (1930), to be sung in French and Arabic. These were inspired by listening to Koranic singing classes and street beggars, soon recorded by Pathé. In its introduction, he admits to bringing his own imagination to the project: ‘It's Arab and Berber music, but pondered over, digested, or, if you wish, ‘reacted to’ by a Western sensitivity’. Chottin hoped these choruses could bridge differences, ‘a source of spiritual communion between French and Muslim people’ (Chottin c. Citation1930b, i). Not surprisingly, such hybridities, encouraged by the Protectorate, elicited both admiration and criticism (Pasler Citation2012, Citation2015).Footnote12

Chottin was Ricard's first and most important musical collaborator. Garnering attention for his Fez transcriptions and at the request of Si Mohamed Tazi, Pacha of Fez, in 1927 Chottin received 5000 francs to report on ‘the state of music in Morocco’ and make recommendations for its ‘methodical study, conservation, and renovation’ (Ricard Citation1932b; Le Courrier du Maroc, May 7, 1939). To enact these recommendations, in Citation1929 Chottin received another ‘mission’ to assist in this process. Like Ricard, who worried that outside influences could lead to ‘parasitic ornaments’ – a reference to the ‘parasitic constructions’ attached to archaeological ruins – Chottin was concerned about not so much loss as accretions over time. Following Ricard's example, he sought to collect, notate, and preserve ‘melodies and rhythms before they changed in reaction to foreign influences’, that is, the oldest music available (Ricard Citation1931a, ii; Chottin Citation1928, 16).

In this spirit, on advice of Moulay Idriss, and seeking collaborations with Moroccan musicians, Ricard created the Conservatory of Moroccan Music (CMM).Footnote13 While colonial officials across the French empire were beginning to advocate study of ‘indigenous music’, colonial support for training Moroccan musicians in their own traditions was virtually non-existent.Footnote14 With funding from Jean Gotteland, director of Public Instruction, Fine-Arts and Antiquities, CMM began in October 1929 as a Cercle musical in the SIA premises at the Oudayas, then under Chottin as director. Teaching Arabic to Moroccan elites’ sons for years had not only assured Chottin a stable job and local credibility, this language proficiency undoubtedly helped in communicating with Moroccan musicians.

Aiming to participate in the ‘general work of reconstruction undertaken by Marshall Lyautey’ (Chottin Citation1934), Chottin not only organised and administered CMM's classes, but also collaborated with Moroccan colleagues on research to ‘determine the diverse musical genres and their relationships with dance and popular theatre, notate the music, realise well-chosen recordings, and assemble documents to serve the history of music’ (Ricard Citation1935b, 19; Citation1932c, 21, 23). This led to wide recognition. In May 1931, the Académie française awarded him a medal for ‘all his work, particularly his contributions to music education in Morocco’. That same month, the Parisian Ménestrel reproduced his 1928 lecture on Moroccan music and its publisher, Editions Heugel, issued the first volume of his Corpus de musique marocaine: Nouba de Ochchâk, a study and transcription of Andalusian music in contemporary Morocco (Chottin Citation1931) – see . La Revue musicale du Maroc reminded readers of ‘all that Moroccan music owes to him’ (N.A. Citation1931, e.g. Chottin 1923 to 1931). Later in 1939, Chottin's synthetic Tableau de musique marocaine was published by the most important Orientalist press in France, Editions Geuthner, also publisher of Prosper Ricard's four volumes of Moroccan rug designs and Baron d’Erlanger's monumental six-volume La Musique Arabe, similarly reprinted in 2001. The Tableau, widely reviewed in press, won the Prix du Maroc in 1938.

Yet, Chottin's pursuits as a respected, albeit self-taught, ethnographer and scholar of Moroccan music do not tell the whole story. His life was characterised by ‘pluriactivity’, several simultaneous and successive types of work.Footnote15 Over the years, he composed symphonic poems, melodies, Arabic songs, and variations on Moroccan themes, some of these ‘transcriptions, translations, and harmonizations’ of Moroccan music he had collected. As music critic and Moroccan correspondent for Ménestrel (1930–1939), his reviews of Western music concerts – from visiting Parisian soloists, such as Alfred Cortot, Wanda Landowska, Pierre Bernac and Francis Poulenc, to the children of French settlers – built Westerners’ trust in Chottin, perhaps leading to the publication of his Moroccan music ethnographies in France. Moreover, in his essays on Moroccan music,Footnote16 Chottin used his cross-cultural sensitivities to explain Moroccan musical concepts to Westerners. In trying to describe the five-beat rhythms of Berber music, rare in French music, he asked French listeners to remember an air from Gounod's Mireille (Chottin Citation1928). He proposed that this five-beat pattern is ‘nothing other than the peonic ‘genre’ of the Greeks from twenty centuries earlier, used to accompany dances on Crete’, also found in the Basque mountains (Chottin Citation1936, 67). His articles on Moroccan music helped illuminate this tradition for many audiences.

Traditional Identities in Discourse and Practice

Urban vs. Rural Traditions

Western scholars have long reiterated Lyautey who, to divide and conquer, pointed to distinctions between urban Arabs and rural Berbers, as with Viets and mountain tribes in French Indochina. However, the often-cited antagonism between ‘bled-el-Makhzan (land of government)’ and ‘bled-es-siba (land of dissent)’ did not map neatly onto urban vs. rural or Arabs vs. Berbers. Even before colonialism, dissent by Arab artisans in urban guilds was directed against the Sultan, rural tribes could be Arab or Berber, and the latter long had their own ‘strong legal tradition’ (Chikhaoui Citation2002, 14–15, 63–65).

Such binaries impacted colonial discourse in Morocco significantly, but call for critical analysis. When it came to music and poetry, Berber scholar Robert Montagne contrasted the ‘imaginative Arabs’ with Berbers’ ‘absence of imagination and poverty of invention’, albeit capacity for ‘adaptation’ and ‘acquisition’ (Citation1931/1986, 33). However, Ricard and Chottin organised their research into frames defined by context more than race: two life styles, nomadic and sedentary, whether Arab or Berber; the influence of ‘two civilizations, urban and rural’, the former including popular, classical, and Jewish music; ‘the Makhen tendancy and the Siba mentality’ as ‘two states of mind’ (Chottin Citation1924, 225; Citation1928, 4); and later ‘classical’ music, associated with cultivated urban elites, that of ‘popular allure’, embraced by artisans in cities and the countryside, and Saharan music, with Black influences (Ricard Citation1932d).

Significantly, Ricard and Chottin took care not to overstate these generalisations. In the category of Arabs, Chottin includes those who ‘returned from Spain’, ‘berberized Arabs as well as arabized Berbers’ (Chottin Citation1928, 7). They also acknowledged paradoxes and intracultural hybridity. Ricard (Citation1918a, 7) explains that he encountered mountain tribes known for their Arab origins, yet producing work with a Berber character. Chottin (Citation1932, 351n) points out, ‘Popular songs use all genres, sacred and profane, urban and rural. They are simultaneously an original substratum and the residue of cultivated, learned music.’Footnote17

Right from the beginning, Ricard found that the repetitive geometric patterns of ‘peasant’ or ‘rural’ art, never representing nature, differentiated themselves from the more complex patterns of ‘urban art’, often inspired by vegetation and designs from Asia Minor. The latter, with its multiple influences, were also harder to define (Ricard Citation1917, Citation1918a, Citation1918b, 10). When it came to music, while admitting that there could be a third kind that results from ‘their interpretation, their mixing’, Ricard similarly distinguished between ‘rural’ music’ – peasant, primitive, as varied as the contours of the soil that changes so much’ from the mountains to the Sahara – and ‘urban’ music–’learned and refined, from Andalusian memories that recall the Reconquest, quite unified and more or less classical … often performed in bourgeois gatherings’ (Ricard Citation1931a, ii, v). Chottin connected the binaries mentioned above to two kinds of ‘aural education’, the first defined by rhythm, its ‘primitive’ nature linked to rural people's closeness to nature, the second by melody, associated with ‘the civilised, the refined’ aspects of city life. Moreover, as he explained, whereas rural Berber music – older and more varied – was performed outdoors, in public, and accompanied by dance, urban Andalusian music – a classical art with its own ‘monuments’ – was played indoors, in private, and by highly trained musicians (Chottin Citation1928, 4–7).

With important differences, this discourse recalls long-standing divisions in Europe between city and countryside, predating colonial strategies of domination, and French approaches to folk music. Ricard's and Chottin's use of ‘refined’ and ‘civilised’ for urban Andalousian music, ‘peasant, primitive’ for rural Chleuh music, recall the importance of class in such divisions in Europe. While, in Europe, they connoted written vs. oral communication, with folk songs composed collectively and ‘usually disseminated anonymously’, in Morocco, urban art music was also an oral tradition and Chleuh master musicians were widely recognised. More pertinent than Scottish and German traditions (Gelbart Citation2007) are French predecessors. In the 1880s Bourgault-Ducoudray allied ‘primitive music’ with ‘primitive races’ taking refuge from outside influences in the mountains, thus synonymous with racial origins. Similarly, Berbers retreated to the mountains with the Arab invasion. Julien Tiersot looked to ‘melodic types’ of the French chansons populaires as ‘the remaining debris of the primitive art of our race’ (Pasler Citation2007, 156–157), but there were many races in Morocco. Embraced and idealised, ‘primitive’, meaning developmentally early, was also applied in France to certain art music, e.g. Palestrina's early polyphony, popular in the 1890s. But, unlike Western art music, fixed by written notation, the ever-changing nature of chansons populaires, characterised by variations in melodic formulae and rhythms over time and space, suggest the effects of not only oral transmission, but also acclimatisation, i.e. adaptation to context, and assimilation – key elements in French imperialism as well as Chleuh music. Finding these variants across France suggested a shared tradition, capable of signifying the nation not through ‘purity’ or nature, as Gelbart identifies elsewhere, but omnipresence. Likewise, Chleuh groups’ extensive tours around Morocco, one over 31 months, undoubtedly contributed to trans-regional connections through music (Tiersot Citation1894; Ricard Citation1933a; Pasler Citation2007). To the extent that understanding rural Moroccan music was pursued by a cultural outsider, Chottin resembles Tiersot, a Parisian, and other Europeans, except that Berber society was not ‘dying’, the ‘salvage’ of its music did not depend on the outsider, and Chottin integrates analysis of dance as essential to this tradition (Gelbart Citation2007, 1–13, 114, 167–171; Williams Citation1973; Chottin Citation1933b). Also unlike in Europe, Moroccan national identity increasingly was tied to its art music, even if linked to its origins in Syria and Spain.

Arguably more important than these European resonances were local political needs, especially alliances with urban elites. The Andalusian refugees in Morocco settled largely in Fez and Rabat. The 1917 Dahir had left the ‘hierarchies of the pre-colonial order untouched’ (Miller Citation2013, 94), including municipal councils with local elites. Having lived in both towns, Ricard and Chottin recognised that their music was sophisticated as well as ‘healthy distraction’, ‘recreation’ they could ‘perform for one another’, and ‘entertainment that keeps them away from political chitchat’. It is important to note that, for Chottin, Andalusian music expressed values colonisers wished to support: ‘the quasi-religious respect for tradition, submission to the rules received from the ancients, defiance in face of all innovation.’ Meanwhile, it recalls not only the connection to medieval Spain, but also bidirectional influences over the centuries between European and Moroccan music. The Western sonata form, Chottin noted, was ‘probably an adaptation of the Arabic nūba’ from Grenada (Chottin Citation1928, xiii, 14,16; Citation1929a, 32, 38, 39; Citation1931, xiv).

Ricard's and Chottin's early publications support these urban/rural distinctions. Volume 1 of Ricard's Corpus de tapis marocains (Citation1923), written ‘under orders of the Residence-General’ for the SIA, reproduces rug designs from Rabat. As Ricard notes in his introduction, these carpets were the ‘prototype’ for all other urban carpets in Morocco ‘of which the oldest seem to go back to the 18th century.’. This Corpus was assembled to codify and legislate which designs should be used in carpets exported abroad (Ricard Citation1923, vii, 5). Likewise, volume 1 of Chottin's Corpus de musique marocaine, ‘published under the direction of Prosper Ricard’ for the SIA, transcribes an urban Andalusian nūba from Rabat, based on a text in the al-Haïk compilation (1786), itself an earlier ‘restoration’ (Chottin Citation1931, xiii). Like Ricard's urban rug designs, this nūba was meant to serve as a model to be studied, used in teaching, and emulated or, as Ricard later put it less prescriptively, as ‘typical examples of classical urban music’ (Ricard Citation1935b, 19).

In the next volumes of his Corpus (1926, 1927), Ricard focuses on rug designs from rural areas of the Moyen and Haut Atlas, but without the intention of having these used as models since rural genres were always changing.Footnote18 Then in 1928 Resident-General Théodore Steeg requested that cultural renovation should spread to the tribes of the plains and the mountains and include music. In 1932, Ricard wrote on the arts and music of Souss and asked Chottin to turn next to music of the Chleuh, ‘a very important part of the Moroccan population, larger than that of all the cities put together (Ricard Citation1933a, 5). With regions the Chleuh inhabited largely remaining outside the Protectorate until 1934, it was looking to incorporate them, political interests underlying musical choices.

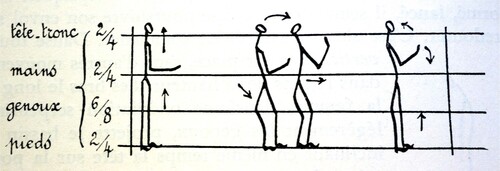

Chottin's Corpus II (Citation1933b) focuses on Chleuh music and dance from the Haut Atlas, Anti-Atlas and Souss. The Chleuh, chosen for their musical talent and ‘suppleness in terms of assimilation’, were known for their ‘pastoral isolation’, recalling the French folk. Ricard wrote a preface and introduction to Chottin's analysis. He presents the major practitioners and troupe members by name, their instruments, poetry, performing tours and three-partite spectacles – an instrumental prelude, song, and dance. Just as Chottin's volume 1 follows the model of Rouanet/Yafil's Répertoire in terms of monodic transcriptions with rhythms notated on separate staves and texts in both French and Arabic, volume 2 presents musical transcriptions of short tunes in various musical modes. These were organised geographically and acknowledging tribal ethnicities or by performance group. The rest, refuting the lack of invention Montagne saw as characteristic of Berbers, focuses on notation of the composite rhythms, gestures, and dance movements accompanied by Chleuh music, including foot patterns, bodily positions, and group configurations, This volume – first of its kind – thus ties musical fragments and their rhythms to dance steps. Photographs of performers with instruments and in dance positions bring the notations to life. In Chottin (Citation1939), the author further explores its rhythmic complexity. To show the four parts of the body enacting Chleuh musico-choreography, he developed another innovative notation consisting of a four-line staff, each with its own meter (e.g. 2/4 and 6/8) ().

Figure 2. Choreographic notation. Alexis Chottin, Tableau de musique marocaine. Paris: Geuthner, 1939.

There were also other reasons to focus on the Chleuh, largely sedentary people. Their music suggested that North Africans had common origins with not only the Middle East and Europe through Arabo-Andalusian music, but also ancient Greece. Whereas folklorist Louis Bourgault-Ducourday had identified Greek scales in Brittany, Salvador Daniel and Rouanet in Algeria, Chottin compared Chleuhs’ sung and danced Ahidus (Aḥidūs) with the ‘Corinthian dithyramb’, their mixed chorus arranged in a circle (Pasler Citation2007; Chottin Citation1929a, Citation1930a). At an ‘indigenous soirée’ in Marrakech, organised by Si Mammeri, a local reviewer, impressed with Chleuh rhythms and dance, heard the timbre of feet beating as ‘ancient, perhaps the origin of poetry or the longs and shorts of the Phoenicians or Homer, maybe to show Stravinsky what people did four thousand years ago’ (L’Atlas, June 9, 1929). On another occasion, Boutet Citation1930 agreed, the Chleuh could ‘help us understand what Sophocles and Euripides must have borrowed from shepherd games in Thessaly’. If North African Berber music could be a potential source of knowledge about ancient Greek music, then knowledge of the Other was capable of enhancing knowledge of the Self.

Chottin surmised that Berbers’ music may have predated that of the Greeks, having ‘borrowed and borrowing nothing from anyone’. Following an article in Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Musikwissenschaft suggesting parallels among Asian and Berber music, Chottin wrote that Chleuhs ‘never brag about preserving an old traditional folklore’. While they constantly assimilate other music, the ‘Cheulh personality’ imposes ‘its manner of listening, its rhythms, its modes of expression that continue over time with remarkable unity’ (Chottin Citation1933c, 11, 12).

The democratic nature of the Chleuh and the original character of their music led to widespread fascination among French settlers and urban Moroccans, few of whom knew it. Chleuh musicians, and the festivities to which they contributed, were frequently featured in the press and news clips. By January 1932, Ricard claimed, with remarkable hubris, that the ‘prosperity’ of these artistic groups was ‘a consequence of our presence in Morocco’, overlooking the fact that the increase in Chleuh groups from 3 or 4 to around 20 in past decades may have been due to Raïs Hadj Belaïd (Hāj Bilaīd), who claimed that 37 of his former musicians were now touring on their own (Ricard Citation1933b, 14). To the extent that French support for Chleuh music and dance won the ‘hearts and minds’ of a population which had resisted French domination, it may have helped in the Protectorate's conquest of the rest of Morocco. As French ambitions grew, Chottin claimed, ‘we will attempt to predict what the future evolution of this art could be and in what direction official action should be taken to save its distinctive characteristics and its cultural value’ (Chottin Citation1939, 54).

Thus, while Ricard and Chottin understood urban arts as ‘more advanced’ than rural ones, they recognised the latter's inherent qualities and political importance, including, as suggested in their music, their capacity for assimilation. Ricard and Chottin also acknowledged ‘reciprocal influences between Arabs and Berbers’ (Chottin Citation1929a, 39). In giving substantial attention to both traditions, their work led to the conclusion that urban and rural art, each with a long history, were integral, valued parts of the Protectorate, a history they intended to shape.

Co-Producing Knowledge and Music

We’ve seen how important was Chottin's collaboration with Prosper Ricard. The latter commissioned Chottin's reports on Moroccan music. He ‘directed’ and contributed long introductions to Chottin's Corpus I and II, and much more. Their respect was mutual and they seemed to have shared many fundamental values, especially a commitment to the Protectorate's agendas. Still, the success of their endeavours depended on investment in and partnership with Moroccans, particularly those with shared interests. Earlier in Rabat, Resident-General Steeg, who began his career as a radical socialist, opened the 1928 Congress of the Institute noting, ‘Our coming together will result not from constraints and resignation, but from reciprocal esteem. This will give rise to the collaboration of these two peoples aware of their respective originality’ (N.A. Citation1928). The 1931 International and Intercolonial Congress on Native Society in Paris called on Westerners to ‘act upon the native and promote him, in human terms’, through ‘tolerance’ and ‘collaboration’ (Wilder Citation2005, 239).

Focus on artisans arose out of the need to counteract the inevitable impact of modern imported goods — ‘unemployment and misery touching the majority of artisans in urban centers’ — and help them compete successfully with rivals in other countries (Ricard Citation1931b, 3, 4). To ‘protect’ their jobs as well as the ‘local character of their industries’, at first the Protectorate created official workshops in major cities. To encourage production of carpets in the traditional manner and their sale abroad, it established a stamp guaranteeing a rug's authenticity, quality, and ‘indigenous character’ and deleting the customs tax. Ironically, this could include ‘acceptably authentic’ innovations, including adaptations to remove foreign influence or suit market demands (Mokhiber, 270–271; see also Girard Citation2006).

Ricard preferred study and ‘indirect supervision’ (Ricard Citationn.d.b). During his visits around the country, he asked local leaders and military officers to identify the best artisans who then filled out detailed questionnaires about themselves and their production, its typologies and fabrication methods. Ricard published their answers and his analyses in his multi-volume Corpus (1923-1929). But reviving local industries relied most of all on collaborating with Moroccans, including their urban guilds (corporations). Recognising practitioners’ individual needs, Ricard likewise supported private initiative, allowing artisans to remain in their homes, form their own corporations, and sell their products. To train the next generation, including women, the SIA also opened schools.

In Andalusian music too, collaboration was defined as shared work on its revival and renovation. Here too, the presumption of authenticity played a role, but which tradition, from which people, in which place? Refugees came from various cities in Andalousia. What has been the role of ‘communal memory’ and practice in reconstituting it and of external influences over time? And how should this be captured, represented, and promoted? On the methodology of folk music collecting, Stokes (Citation1994, 7) and Walden (Citation2013) have argued that ‘authenticity is a discursive construct, rather than a property inherent in music, and it is always subjective and mutable’. In Europe, preoccupation with authenticity often focused on folk music as emblematic of national origins (Gelbart Citation2007; Pasler Citation2007, 159–160). However, in the twentieth century, questions of authenticity arose in classical art music for both Westerners and North Africans. Whether Wanda Landowska and European early music societies or proponents of Andalusian music, they sought continuity with musical traditions of the distant past. In North Africa, this included ties to certain families with ‘purity of blood’. According to a contemporary Algerian, ‘people think of authenticity as residing in individuals rather than the music itself’. As such, master musicians could ‘withhold or distort knowledge’ (Glasser Citation2016, 27, 39, 164).

Like Ricard, Chottin worked with locals in this pursuit of musicians and their knowledge of tradition. Aware of problems inherent in the oral tradition, he sought those who were ‘above all, respectful of the tradition and in a way incapable of changing a single note’. As he tells it, when it came to who and what to transcribe, ‘Moroccans themselves took charge of choosing for us the master that we needed in the person of Si Omar Jaïdi, originally from Fez and personal musician of his Majesty the Sultan’. In his introduction, Chottin explains:

We took care not to influence this informant … . He performed for us (dicter) what he calls the root (el-asl) of the song, that is, the fundamental melody stripped of its ornaments (zuak), very often parasites … . These ornaments are one of the most original characteristics of Andalusian music, what leads the artist to improvise, to the need to create. Among the embellishments, some are used so often that they became obligatory … our informant always pointed them out. But he took care not to imitate the pseudo-virtuose who mask their ignorance under the pretext of ornamenting the melody and end up distorting and corrupting it.Footnote19

If Chottin's contacts in Rabat helped him gain access to the Sultan's musician, similarly Ricard and the Pacha of Marrakech, Thami El Glaoui – cosmopolitan son of a slave and close collaborator of the French in their ‘pacification’ (conquest) of the mountains and desert – most likely introduced Chottin to Cheulh musicians. Glaoui had his own reasons to collaborate with the French and facilitate access to Chleuh musicians – his ambition to depose the Sultan and take his place. Ricard first encountered their spectacles in Marrakech on his first trip to Morocco in 1913, later at Glaoui's palace. Afterwards, he invited them to perform in Rabat and paid Odéon to record them. In his substantial introduction to Chottin's Corpus II, Ricard refers to four major Chleuh Raïs (maestros) from different regions, the size and makeup of their troops, a typical programme, and twelve recordings he commissioned of their songs. Chottin explains that most music in Corpus II comes from what he gathered from Raïs Mohammed Sasbou (Muhammad Sasbū). His troop of 16–18 members, with 12 dancers, performed all over the country, including in Casablanca and Rabat where they most likely collaborated on this volume. Some transcriptions are of Sasbou's ‘favourite songs’, some adaptations of European military band music, recorded by Odéon. Chottin also includes music and dance by Raïs Brahim's ensemble and a spectacle by Raïs Hadj Belaïd. This elderly poet-composer who spoke both Arabic and Berber, a kind of ‘official’ artist, ‘often proclaimed the benefits of the Moroccan state and its representatives’. Glaoui considered Belaïd the most famous of the period. Ricard first met him in Marrakech, where his troop performed at a wedding. Apparently Ricard invited his musicians for a ten-day residency at the CMM where he interviewed the Raïs for his introduction to Chottin's Corpus II (Ricard Citation1933a, 13–15).

CMM offered Chottin an ideal context for teamwork with Moroccan colleagues. Beginning in October 1929, he hired the best local musicians who could both teach and serve as ‘informants’ in his research. Two of them, El Hadj Abdesselem ben Youssef (al-Hāj ʻAbdassalām bin Yūssif) and Si Mohammed MBirkô (Muḥammad Mbirqū), were among the Moroccan delegation to the Congress of Arabic Music (Cairo, 1932). With his phenomenal memory, Ben Youssef, a singer, could dictate an entire nūba and identify the melodies on over 50 recordings. MBirkô, rebec and lute performer, could notate his lessons. The singer Moulay Idriss, hired later, could dictate six classical songs, including their variants, and produced a song collection for use in teaching, 200 copies of which Chottin purchased for CMM in 1935.

Like artisans who shared specimens of their best work for Ricard's rug Corpus, these colleagues enabled Chottin to notate important musical repertoire. Their collaborations produced enough material for three more volumes of his Corpus, sadly unrealised, including transcriptions of 26 pieces from another nūba, Hagaz El Mecherci (Hijāz al-Mašriqī). These restitutions required great effort from colleagues and repeated performances (Ricard Citation1932b). Chottin also collaborated with CCM professors on one song that, although having an ‘oriental filiation’, had degraded over time in terms of its rhythms and melodic shape. Yā Asafā, he explained, was neither an Andalusian sana (ṣanʻa) nor a griha (ġīida), but an ‘intermediary’, the best known lament inspired by nostalgia for Andalousia. After translating and analysing its five stanzas of text and rhyme schemes as well as its free use of the modes, Chottin asked Moroccan colleagues to play it for him so that he might transcribe their performance. MBirkô accompanied himself on the rebec, singing in unison with it, Ben Youssef on the tar, Mokhtar Loudiyi (Muktār Lūdiyi), who arrived in October 1931, on the lute (Chottin Citationn.d.).

These performances resulted in three distinct versions of Yā Asafā, embodying collaborators’ different talents and styles of performance. MBirkô played the melody in a bare way, as his rebec did not lend itself to virtuosity; Ben Youssef used hesitation in his delivery to elicit desire for the melody, perhaps coming from the parlando he employed in performing qacidas (qcîda/qaṣīdas); full of irregularities and involuntary syncopations, Loudiyi's singing resembled his playing as a left-handed musician. In transcribing these, Chottin wished to show that, ‘transcriptions can bring to light not only variations related to the oral tradition, but also individual aspects of the ornamented style.’ Although he never published these nor his complete score with accompanying instrumental parts, Chottin made a simple version of the first three stanzas, reproduced in his article on the CMM to exemplify their collaborative work (Ricard Citation1932b, 28; Chottin Citation1934). Chottin also composed his own rendition of Yā Asafā for piano and voice, respecting variations in the repeats, verses and refrain. As in Tiersot's transcriptions of chansons populaires, he added rich harmonies and instrumental interludes, likely for Western audiences, the second with a habanera rhythm, later the last movement of his Chants arabes d’Andalousie (Paris: Dupuis, 1938).

Co-producing these works endowed them with intelligibility, legitimacy and meaning. Not only did this process define and stabilise certain musical pieces and variants through written notation, some widely accessible through publications, it rendered them aural through performances. Sharing these with the public was a domain wherein Chottin wielded considerable power. In 1934, he organised the CMM's first public concert at the Oudayas museum. CMM performers played excerpts from six nūbas, including Nouba de Ochchâk, and Yā Asafā – works Chottin had transcribed. Balafreij improvised and Moulay Idriss sang bitain and moual (muwâl/mawâl) with French translations for the mixed audience. Chottin then introduced and conducted his Franco-Arabic choruses, Le Muezzin. While such concerts were useful in demonstrating their accomplishments to the Protectorate, the musicians showcased their talents. In sponsoring this one, attended by director of Public Instruction Gotteland, the Pacha of Rabat, and many Muslim and European elites, the SIA hoped to stimulate formation of a ‘Franco-Muslim association, the Friends of Moroccan Music’ (Ricard Citation1934a). With the Protectorate now in power throughout Morocco, was this a model for how it envisaged culture contributing to political stability?

Public Action, New Institutions and the Music Business

Other significant collaborations were based in the public sphere: specifically three new institutions created by the Protectorate – CMM, music festivals, and Radio-Maroc. Here the Protectorate's engagement in cultural protection, promotion of Arab and Berber culture, and commitment to collaboration gave rise to new jobs for Moroccans, regular salaries, and new markets for their products. This allowed them to make a living that was ‘interesting from both an artistic and financial perspective’ (Ricard Citation1931b, 6). Although supervised by Frenchmen, Moroccans could express their creativity and grow as artists, spurring unprecedented expansion in the music business, including for women.Footnote20 These three institutions also stimulated public interest in Moroccan music and facilitated the formation of a coherent aesthetic, with implications lasting well beyond the Protectorate.

Institutionalising Musical Knowledge at the Conservatoire de Musique Marocaine

Beginning in 1930, the SIA budgeted 20,000 francs per year to support the CMM in Rabat and, with the help of Pathé and Odéon, a library of recordings, musical instruments, and books. It would be a ‘laboratory for Moroccan music where performers come together several times a week at fixed hours throughout the year to work seriously on perfecting their technique and developing their musical culture.’ CMM's curriculum focused on urban music, predominantly the Andalusian classical tradition. It also taught popular genres, qacidas drawing on this tradition and aïtas (aytas/ayṭa), ‘long scorned’.Footnote21 Lessons for ‘pupils asking for instruction as well as amateurs [non-professionals] or professionals wanting to improve’ would help ‘save traditional techniques from oblivion and give them new life’ (Ricard Citation1930, 21; Citation1931a, iv; Citation1932a; Citation1936).

Unlike traditional apprenticeships wherein pupils studied with one teacher, this new institution, recognising multiple ways of knowing and doing, offered instruction from various teachers. Chottin's credibility as director came from not only his conservatory training, but also his publications, research connections with Moroccan musicians, sincerity, and enthusiasm. Ricard charged him to ‘look after the company’, ‘interact with it daily’, and ‘guide it in its exercises and teaching’ (Ricard Citation1936). But putting together a faculty proved difficult. The CMM needed well-known artists, but most lived in Fez or Marrakech. Ricard's relationship with Rabati elites and ‘bourgeois’ Moroccans opened doors, though many musicians in these contexts were amateurs.

The first teachers, its ‘founders’, resembled the traditional Andalusian orchestra, with Ben Youssef on the tambourine (tar), MBirkô on rebab (rebâb) and lute (ûd), Mohammed Guedira on violin (kamanja/kemân-gäh). Although vocal genres receive little attention in Moroccan scholarship, Chottin considered bitaïn (bitayn/batayn) and moual important enough to hire one singer for each. Both knew Ricard, had encouraged creation of the CMM, proven themselves on Rabat's 1928 festival and Radio-Maroc, and made recordings for Ricard in 1929 (see below). Si Abdesselam Balafreij (Abdassalām Bilfraj), aged 25 and bourgeois, entered in 1929 as pupil, becoming teacher in 1930. It took Ricard until January 1931 to persuade Moulay Idriss, like Balafreij an ‘amateur’, to join as bitaïn teacher. More ‘cultured’ than other Conservatoire colleagues, the latter later functioned as associate director, remaining on staff through 1939. Four additional lutenists were hired in 1931–1932, Si Omar El Ouali, bitaïn singer and concierge, and two more violinists, Mohammed El Aoufir and Si Mohammed Bel Khadir (Bilqādir/Bin Khidir), in 1934.

With instruction free and open to all, ‘regardless of origin, age or culture’, with or without an instrument, the selection of students reflected French desire for wide accessibility, not just children of elites. This presented serious challenges. All Moroccans, they came from various social classes with different habits, not always available at the same hours. Chottin thus scheduled lessons adapted to their schedules, usually after sunset. From 1929 to 1934, CMM had 31 students. The first group of 14 ranged in age from 17 to 30, including artisans (two in leather, one in wood), a hairdresser, chauffeur, student, property owner and journalist. Their musical backgrounds were equally varied. Two considered themselves music ‘professionals’, five ‘amateurs’ already playing in private concerts (one with MBirkô, another with Belaïd), and five ‘still pupils’. Those admitted from 1931 to 1934 were also artisans (painter, shoemaker, tanner, hosier, draftsman), mostly 15–20 years old (Ricard Citationn.d.a, Citation1936) ().

Figure 3. Students at the Conservatory of Arabic [Moroccan] Music, Chottin, director. In L’Afrique du nord illustrée (11 October 1936).

![Figure 3. Students at the Conservatory of Arabic [Moroccan] Music, Chottin, director. In L’Afrique du nord illustrée (11 October 1936).](/cms/asset/562db7ae-df91-4274-a858-112931a3d176/fnas_a_2099844_f0003_oc.jpg)

Given that some professors and students were illiterate and there was no Moroccan form of musical transcription, Ricard and Chottin rejected European teaching methods. Echoing his resistance to foreign influences, Ricard felt that solfège ‘responds in no way to the needs of Arab music’ and ‘would be dangerous for Arab music’. Ironically, ‘almost unanimous’ student demand led to starting each class with a short solfège exercise, suggesting a tension between French desire for an authenticity needing protection and Moroccan attraction to the advantages or allure of modernity. As with Ricard's hands-off approach to working with artisans, ‘no unusual intervention would disturb the traditional manner of oral transmission’, no ‘interference intended to perfect the teacher's pedagogical procedures’ (Ricard Citation1935a). Students learned by listening, including to recordings. As in traditional music apprenticeships, class entailed the teacher's performance of a piece, analysis of its principal characteristics, then students’ recital and repetition of fragments until memorised. Separating beginners from those with some knowledge, Chottin created three groups: preparatory concentrating on rhythmic and melodic types, middle-level learning instruments, advanced studying repertoire (Ricard Citation1931a, iv; Chottin Citation1934). As noted in Cairo (see below), Ricard expected pupils to take greater care with the quality of sound production than in traditional practices (Ricard Citation1932c). Among other new procedures were ‘advance study of the poetic text, rhythm exercises, singing and intonation exercises, study of the instrumental melody and, together, a san’a (singing a poetic stanza, including vocalises and ornaments)’ (Chottin Citation1931, 13–14; Citation1939, 222.) Curricular decisions were thus shared, though Moroccans controlled their pedagogy.

Weekly concerts were a regular part of CMM, practice integral to knowledge production and training in public performances. Each Saturday professors played together for an hour, introducing pupils to what their classes would study the following week (Ricard Citation1932c, 25). Moulay Idriss helped plan the programmes. Open to the public, these attracted a substantial audience, including Gotteland and visiting artists. Besides its concerts for the SIA, an ensemble of faculty and students also played at Moroccan and French receptions and Radio-Maroc, bringing new audiences to the CMM and enhancing its status. Regional music schools, inspired by CMM, soon opened in Fez, Meknes and Marrakech.Footnote22

Music Festivals, 1928–1939

Beginning with the Franco-Moroccan Exhibition in Casablanca (1915), decorative arts fairs in Paris (1917, 1925), colonial exhibitions in Marseille (1922), Strasbourg (1924), and Paris (1931), the Granada festival (1931), and the Cairo congress (1932), the Protectorate supported the participation of Moroccan artisans and musicians. Such efforts also took the form of music festivals devoted to Moroccan music. To attract large mixed audiences, they were programmed alongside other major cultural events. In 1928, Rabat's festival coincided with the Institute's annual Congress (with Ricard on its organising committee and as speaker), the Muslim ‘Mouloud’ Festival, and the Fair where crafts were exhibited and sold and Radio-Maroc had a booth. The Institute's 1933 Congress in Fez took place alongside its Fair. And in 1939, the largest of these in Fez again took place during the artisanal Fair and ‘Mouloud’ Festival. Such synchronicity brought Moroccan music into larger intellectual debates as well as religious and commercial contexts, underlining music's multi-faceted importance and meaning in Moroccan society. Festivals thus established the state of Moroccan music, not just Andalusian, but also Berber and popular genres. Over time, festivals also increased Moroccans’ agency in their organisation and research presentations, reaching parity with Europeans in 1939, stimulated reflection on local distinctions, and fostered respect in national and international contexts.

Rabat

To help them identify Moroccan musicians and build partnerships, in April 1928 Ricard, together with Public Instruction director Gotteland, sponsored ‘Three Days of Moroccan Music’. Ricard and Chottin assembled 50 Moroccan musicians, including the 22-member music society from Oujda, L’Andalousia, the Sultan's musician Jaïdi, and various ensembles. As they studied the current state of Moroccan music, they reflected on how to move forward with its renovation. The first day presented the overall situation, with diverse musical examples; the second, traditional Moroccan music; the third, modern Moroccan music. Concerts in the French-designed garden of the Oudayas and on the patio of the Residence were free. Alongside many dignitaries, almost 3000 Europeans and Moroccans attended.

The challenge was to create concerts that were both inclusive and coherent, most likely Chottin's responsibility. Ricard had advertised this as the first time musicians from all regions of Morocco would perform together – in reality, most were from near Rabat. On the first day, after Ricard's introduction, Chottin (Citation1928) addressed urban and rural, mystical and secular music and instruments of popular and art genres. He illustrated the discussion with an Ahidus air, sung and danced by three Berbers, as well as ‘urban music’ – ghaïta (ġayṭa) airs on the tebol (ṭbal), qacidas and moual sung by women (hadarat [ḥaḍarāt] and chikhate [šiḵāt]) and men (chiakh [šiaḵ]), Andalusian airs and an overture. Day two focused on ‘traditional music’, with L’Andalousia from Oudja and an orchestra of musicians from Fez and Rabat, including Jaïdi, performing Andalusian airs. Audiences also heard songs by eight Berbers from Zemmour (100 km from Rabat), ghaïta airs by musicians from Salé, and qacidas by six female chikhates from Rabat.Footnote23 ‘A very original interlude by a Negro clown from Marrakech’ provided contrast (Ricard Citation1928, 9).

Day three's concert turned to Moroccan and European, choral and instrumental, classical and modern, old and new music by young and established performers. These juxtapositions called for comparative listening in the French tradition of using concerts to promote understanding of differences (Pasler Citation2009). This time the concert began and ended with Chottin's Moroccan-inspired compositions, as if modern day Morocco should be framed by a French standpoint. The local military band opened with his warrior march, Dans l’Atlas, based on Berber themes, a reference to France's ongoing attempts to subdue the region. Chottin's popular school choruses, Le Muezzin, performed by his pupils, ended the concert. Between his Berceuse mauresque and Danse nègre came three Andalusian pieces by L’Andalousia. In this context, traditional Moroccan music contrasted with modern hybridity, memory and nostalgia with contemplation of the future.

Chottin got his start as Ménestrel's ‘correspondent’ with his long, evocative review of its 1929 successor, again coinciding with the ‘Mouloud’ festival (Citation1929b). This time, besides he and Ricard, Mohammed Ben Ghabrit (Muhammad Bin Ġabrit), Si Azouaou Mammeri from Marrakech, and the director of the publicity agency Havas organised a concert at the Oudayas. The blind musician Si Mohamed Krombi opened with musettes from the upper remparts of the Kasbah. Ben Ghabrit presented an orchestra of the ‘best musicians from Rabat and Salé’, including a rebab player and Black lutenist. Although not professional, Ben Ghabrit conducted them ‘as if an ensemble worthy of our symphonic phalanxes’ in performances of two nūbas in different modes. Two troops of female chikhate from Rabat and Marrakech followed, together with the master (mâllema) Khadidja in well-received performances of popular qacidas, moual, and aïtas. Chottin (Citation1929b) reached out to Westerners, describing ‘sophisticated aïtas’ as ‘invocations that develop into a kind of Italian overture’. Overall, ‘the sweet and melodious voice of the singers, those from Marrakech especially, made a good impression on listeners’. Chottin devoted substantial space to describing the clown, Hommâne ben Guir, ‘star’ of the show, a real ‘revelation’. Ben Guir could imitate various people ‘with an acute sense of observation’ and a talent for the ‘burlesque and profound that recalls Molière's Scapin’. Finally, a dance-choral troop from Souss, most likely Chleuh, presented ‘raucous’ melodies, danced rhythms, and an orchestra he found ‘both primitive and refined’, the latter otherwise associated with Arab classical music. The ‘enormous fig trees with twisted trunks harmoniously arranged around the terraces’ set the scene for performances of ‘rare charm’ for an audience of ‘thousands’.

On May 24, 1929, the SIA sponsored a Berber festival at the Oudayas. After an Ahidus with 70 Zaïr performers at the base of the remparts, singers, flutists, mimes, and comics from Zemmour, Rabat, Salé, Marrakech, and Meknes performed, each part ending with a danced spectacle from Souss. In 1930 and 1931, the SIA contributed 10,000 francs to support two additional festivals with ‘spectacles analogous to our medieval farces’ and three troops of Chleuh musicians and dancers from Souss, each with 12–15 members (Ricard Citation1931a, iii–iv). Here Moroccan artists became ‘more self-conscious and surpassed themselves,’ eliciting admiration and respect (Ricard Citation1930, 28). Such events likely facilitated Chottin's work on Corpus II.

Cairo

Ricard, leading the delegation, and Chottin, CCM director, also took part in Cairo's Congress of Arabic Music (March 14-April 3, 1932) which aimed to grant ‘official consecration’ to this genre and study future directions (Chottin Citation1933a, 3, 21; Ricard Citation1932d).Footnote24 Patronised by King Fouad of Egypt, it brought together c. 50 ‘Orientalist’ scholars from Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East and c. 100 ‘Oriental artists’ from Iraq, Syria, Turkey and North Africa, the latter, in Ricard's view, ‘conscious of the stagnation of their art’. Representing Morocco were Kaddour Ben Ghabrit, Algerian-born minister and representative of the Sultan, invited by King Fouad, his brother Mohammed Ben Ghabrit, and seven musicians: Jaïdi, CCM professors MBirkô and Ben Youssef, three master musicians from Fez, and the Palace mounchid. Egyptian reviewers found Chottin ‘more or less the only Arabic music specialist among the French delegation’ (W.S. Citation1932). Member of the Recording Committee, he lectured on diverse genres of Moroccan music, Ben Ghabrit on how he learned music, and Ricard on musical renovation at the CCM.

Moroccans’ exposure here to various Arabic music stimulated reflection on their own practices. La Bourse égyptien praised the Conservatoire de musique marocaine as a model, ‘in sum, what the Egyptian government is currently requesting for Egyptian music’ (W.S. Citation1932). But, when the Congress's Education Committee recommended that ‘elements of solfege’ (Tonic-Solfa) be taught to children at all levels, eventually replaced by traditional [Western] notation, Ricard and Chottin pushed back. At the CMM, they had largely rejected solfège and piano in training Moroccan musicians (Ricard Citation1932c, Citation1935a). Debates in Cairo did not change their minds. Moreover, while colleagues recognised that Morocco's traditional repertoire was rich, albeit using the diatonic scale, unlike in Egypt, some found Moroccan performances lacking the nuances and precision of Egyptian ones (Chottin Citation1932). Moroccans’ three concerts illustrating Andalusian tradition seemed ‘outdated and anachronistic’ to Egyptians, the 30-minute pieces ‘too long’, leaving them ‘visibly weary’ (Chottin Citation1933a). Ricard agreed that, even if Moroccan musicians ‘make a strong impression and can provoke a somewhat deep ecstasy’, they don't listen enough to one another and are indifferent to the quality of voices and instruments’. Ricard and Chottin left determined to address this criticism. Furthermore, Ricard felt that ‘Moroccan musicians better understood the goal and meaning of our efforts and returned even more disposed to collaborate on the task of renovation undertaken by their country’ (Ricard c. Citation1932b, Citation1936; see also Benabdeljalil Citation2018).

Fez

In 1933 the Institute held its annual congress in Rabat and Fez (April 13–21), featuring concerts of Andalusian and Chleuh music and, in a village near Sefrou, a Berber spectacle with 500 performing. Chottin notated two improvisations. The global economic crisis interrupted plans to invite many Europeans, including Manuel de Falla. Nonetheless, Bencheneb, from Algiers, spoke on Arabic theatre; Ricard, Baldoui, Jeanne Jouin and two others addressed Moroccan arts there for the first time; Chottin analysed rhythm and meter in Andalusian music in Morocco, Robert Lachmann, from Germany, the state of music in the Near-East. The latter's participation led to publication of Ricard's review and Chottin (Citation1933c) on Moroccan singing in Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Musikwissenschaft.