ABSTRACT

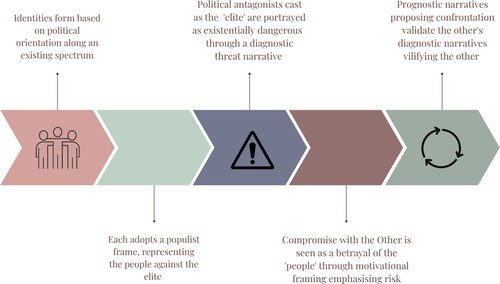

Populism has often been considered to thrive on polarisation. By identifying a ‘people’ and an ‘elite’, populist political actors encourage a dichotomy between self and other; further, placing political opponents outside the lines of normative national identity promotes a praxis discouraging compromise and indicting those who seek to understand the other. At the same time, populists come to prominence during times of grievance. The simplified discourses they espouse offer culprits and straightforward explanations for disillusioned citizens. What occurs when two polarised populists advance narratives addressing similar grievances? In this article, I engage in a frame analysis of the discourses advanced by Tunisian populist actors from 2019-2021: Itilaf al-Karama and the Parti Destourien Libre, who fall on opposing ends of the Islamist-secularist spectrum. I argue that these two populisms have an intensifying effect upon polarisation by substantiating the threat discourses advanced by their opposition.

Introduction: Tunisia’s democratic trajectory, from success story to crisis

The 2019 elections in Tunisia were marked by the dramatic ascent of political actors adopting populist narratives. News outlets and analysts reported on this phenomenon, calling attention to the popularity of anti-systemic figures and the relative decline of more institutionally established parties (e.g. Ghanmi Citation2019; Grewal Citation2019). Part of this shock stemmed from the disconnect between the apparent smoothness of Tunisia’s democratic transition and its present state of discontent. In 2014, a Guardian editorial boldly praised Tunisia’s post-revolutionary trajectory: ‘one nation stands as an exception in the Arab world for having peacefully completed a democratic electoral process’ (The Guardian Citation2014). By 2019, however, it reported instead on an electoral ‘shock victory for political outsiders’ and alluded to widespread societal disillusionment (Beaumont Citation2019).

Much of the early attention was given to the presidential race, in which political newcomers Kais Saied and media mogul Nabil Karoui competed to lead the country. However, the parliamentary elections of 2019 also witnessed the rise of political outsiders like Itilaf al-Karama (the Coalition of Dignity), a party which combined a strong Islamist stance with purporting to defend the revolution, winning 21 seats. On the other side, the Parti Destourien Libre (Free Constitutional Party) – the resurrection of the Rassemblement Constitutionnel Démocratique (Democratic Constitutional Rally), the ruling party in the pre-revolutionary era – also witnessed a surprising electoral success, gaining 17 seats.

Both the Parti Destourien Libre and Itilaf al-Karama adopted populist themes addressing grievances which, since 2014, had become widespread. For much of the Tunisian populace, the revolution had failed to bear fruit: the economy had failed to improve, the political class remained detached from the everyman, and the country stayed divided between centre and periphery, between privileged and underprivileged. The narratives advanced by each actor, however, fell on opposite ends of the Islamist-secularist polarisation spectrum that had influenced Tunisia’s politics to varying degrees since the revolution.

How did the emergence of two parallel opposed populisms impact the general character of polarisation within the country? In this paper, I compare the frames of Itilaf al-Karama and the Parti Destourien Libre to derive a theory through which to conceptualise the relationship between polarisation and two populisms occupying opposing ends on the political spectrum. I find that the frames advanced by both political actors address similar grievances: namely, the foundational elite compromise of Tunisia’s democratic transition. The dialogue between these two polarised populist actors, however, comes to centre around the other, who are cast as existentially threatening to the well-being and sovereignty of the country. In time, each narrative’s resonance depends on the frames of the other to substantiate this threat construction. At the same time, this escalation ensures that the original grievances remain unaddressed.

Materials and methods: framing and counter-framing grievance

To address this project, I adopt a frame analysis in order to assess the dialectic between the rhetoric of Itilaf al-Karama and the Parti Destourien Libre. Benford and Snow define frames as constituting a process of ‘meaning construction’: through representation in a frame, situations and events are made sense of, and an effective frame that aptly and poignantly addresses contemporary circumstances rouses support for a social movement or political actor (Benford and Snow Citation2000, 614). Frames can be separated into diagnostic, prognostic and motivational components (615). Diagnostic frames identify and describe a problem; prognostic frames offer a plan to resolve these grievances and motivational frames inspire action. Comparing the frames advanced by two polarised actors, each adopting populist rhetoric, allows for a comparison of what grievances are being addressed, who is implicated, and what action is encouraged. This enables a closer analysis of how populist actors opposed on an ideological spectrum engage with the rhetoric of the other.

The post-2019 Tunisian political landscape offers an insightful case study for this analysis. The Islamist-secularist polarisation threatening the initial post-revolutionary political transition appeared to have been addressed through civil society initiatives emphasising consensus, leading to what was widely praised as a highly successful democratic outcome. The resurgence of this polarisation, however, coupled with a wider embrace of populist narratives, challenged this analysis. The increasingly co-constitutive relationship between polarisation and different forms of populism provides an insight into this puzzle. As political identities solidified in mutually opposing categories – pitting the ‘revolution’ against ‘Bourguibism’, ‘Islamism’ against ‘secularism’ – the feud between the Islamist Itilaf al-Karama and the secularist Parti Destourien Libre gained increasing visibility and attention, furthered by a plethora of contentious interactions between the parties’ leaders and members (e.g. Kapitalis Citation2021; Dejoui Citation2020).

The sources I draw upon for my frame analysis derive from content posted directly on each party’s social media page between 2019-2021, as well as social media content posted on the pages of prominent members. I also examine news articles where figures from Itilaf al-Karama and the Parti Destourien Libre were interviewed. Assessing a varied array of public primary source content allows for an exploration of how these political actors managed the complex role of speaking directly to their base, attracting potential supporters, and addressing the accusations of their opponents. I adopt a comparative frame analysis as the basis for forming a theory explaining how polarised populist actors’ narratives become fundamentally intertwined.

A theoretical framework: exploring the interactions between populism and polarisation

While competition between ideologically opposed actors may seem natural, the literature on Islamist-secularist alliances in the MENA region in fact provides several instances of cross-ideological cooperation. Nadine Sika discusses how socioeconomic grievances spurred the use of frames by opposition groups that were neither secular nor religious (Sika Citation2012). It is true that party or group ideology can present several ‘red lines’ with regards to cross-ideological participation, where certain issues are not subject to compromise (Clark Citation2006, 540). However, as a whole, ideological difference on its own rarely prevents bipartisan alliances from forming, particularly when this cooperation is performed in service of a specific grievance or project (Buehler Citation2018, 129–136). Studies have rather shown that more relevant factors conditioning whether Islamists and secularists may cooperate are actors’ relationships to the ruling regime (Masbah Citation2014), where political exclusion may incentivise rapprochement between an ideologically diverse opposition (Casani Citation2020, 1184). Based on the Moroccan case study, Wegner and Pellicer’s (Citation2011) tripartite model of factors influencing cross-partisan cooperation or competition considers ideology, the amount of support each party believes it can mobilise, and the ruling regime’s approach to managing its opponents. The geographical distribution of support for particular parties may also play a role: in his comparison of the Tunisian, Moroccan and Mauritanian cases, Buehler (Citation2018) suggests that the social bases of both the regime in question and the opposition can intersect to promote or dissuade Islamist-leftist cooperation.

These explanatory mechanisms, however, pertain primarily to an authoritarian or pseudo-democratic setting, where parties are subjected to constraints and, in a kind of prisoner’s dilemma, must calculate whether their opposition might engage in reconciliation with the ruling regime at their expense. One of the central explanatory mechanisms in Buehler’s model, for example, concerns the possibility of regime co-optation of key opposition figures (Buehler Citation2018, 3–6). If groups are not competing for regime favour within an autocratic setting, the question then emerges: why, when faced with similar grievances surrounding political exclusion and marginalisation, did anti-systemic Islamists and secularists – like Itilaf al-Karama and the Parti Destourien Libre, respectively – not form a temporary alliance based on these grievances against the political ‘elite’?

I advance the idea that a populist stance adopted by one or both ideologically polarised parties can invest ideology with a divisive quality, rendering cross-ideological cooperation impossible. In this sense, populism functions as both a political style and an adaptation of an existing ideological stance. Populism constitutes a master frame or ‘thin’ ideology (Blassnig et al. Citation2019, 1111) adopted by those who purport to be political outsiders working in the name of the ‘people’, even while populist leaders may be distinguished by their charisma or transcendence (Mudde Citation2004, 559–560). As Cas Mudde argues, populism centres a struggle between a ‘people’ and an ‘elite’ (543). This involves a Manichean attribution of moral attributes: the authentic, trustworthy ‘people’ of a nation are juxtaposed against the corrupt, self-interested ‘elite’, who have infiltrated the political, cultural and economic realms. This division can easily be grafted onto pre-existing ideological spectra.

The entry of populist actors impacts how polarisation manifests. The concept of ‘polarisation’ can refer to either ideological polarisation or affective polarisation, which may be only loosely related (Lelkes Citation2018, 68). The former considers the actual depth of disagreement with regards to socio-political issues (Wilson, Parker, and Feinberg Citation2020, 223). The latter refers to the loyalty they express towards their political position and the antipathy directed towards their opponents (Lelkes Citation2018, 68–69). The dualistic moral dichotomy introduced by populism shares an elective affinity with the distrust inherent to affective polarisation. As political opinions become integrated into coherent identities according to which individuals assign ethical values, political opponents become not just misinformed but immoral; populism allows them to be further classified as ‘elite’ and detached from the concerns of the people. Polarisation can become self-perpetuating through geographic sorting, the phenomenon in which individuals with partisan political stances spatially gravitate towards those perceived to share the same political identity, leading to majoritarian political strategies and disincentivising compromise (McCoy, Rahman, and Somer Citation2018, 21–26).

In such a situation, populism can become a useful way for political actors to capitalise on widespread affective polarisation. Zsolt Enyedi (Citation2016) has explored the tendency of political actors from different ideological traditions in post-communist Hungary to adopt competing populist frames. Essentially, he finds that this manifests in a contestation over who constitutes the ‘people’ and which political actor is best situated to define this category: he labels this phenomenon ‘populist polarisation’ (217). As competition ensues, populism becomes ‘self-sustaining’ and increasingly entrenched within the political space, with little incentive for majority parties to offer concessions or compromises to competitors (218).

Competition between political actors across the political spectrum frequently manifests in a series of contentious events (Tilly and Tarrow Citation2015, 39). Over the course of years, claims and grievances advanced by different actors metamorphise and inspire protests and counter-protests (40). Indeed, movements often incentivise the formation of counter-movements; mobilisation in turn incites counter-mobilisation. Meyer and Staggenborg (Citation1996) explain that when a group is faced with a countermovement, the strategies, decisions and narratives adopted by one necessarily influence and compel responses on the part of the other. For example, one group’s perceived success can reinvigorate their opponents (1638). Equally, a new strategy adopted by a movement is often, at least in part, echoed by its countermovement (1649). The embrace of populism by a social movement on one side of a political spectrum thus encourages its opposition to adopt similar tactics. This adaptation involves the formulation of specific frames to explain the roots of contemporary grievances and how they can be addressed.

Results: a consensus among whom?

Tunisia’s post-revolutionary political background

The emphasis on consensus among Tunisia’s political class has been linked to the initial success of its democratic transition (e.g. Masri Citation2018, 295). Indeed, a willingness to cooperate across the political spectrum dates to the Ben Ali era, when neither the Islamist nor the secularist opposition were permitted to form independent political forces. Many political actors agitating for political reform across the ideological spectrum went into exile, where they then began to collaborate. Tunisia’s main Islamist actor, Ennahda, had significantly adjusted its demands to align with liberal democratic norms prior to the revolution, in several instances of cross-ideological compromise to find what Monica Marks considers something of a Rawlsian ‘overlapping consensus’ (Marks Citation2018, 114). While polarisation spurred a series of crises after 2011, the issue was seemingly resolved when the Ennahda-led Troika government voluntarily ceded authority to a technocratic government in 2014, assisted by civil society organisations through an organisation called the National Dialogue Quartet, and regular elections with real handovers of power were implemented. This development was initially viewed with optimism. As Matt Buehler views it, the Troika’s dissolution was proof of the country’s successful democratic transition, in that it ‘derived from [the parties’] desire to defeat each other in fair, competitive elections that had become a normal, ingrained feature of political life’ (Buehler Citation2018, 165). Ennahda’s later coalition with Nidaa Tounes, at the time the most prominent secular political party, seemed to bear further witness to a continued bipartisan spirit of compromise characterising Tunisia’s new political future.

This alliance marked a new beginning for the political class, but for many citizens, it obscured some of the most important issues that had initially spurred the revolutionary protests which, as Haugbølle and Cavatorta note, were not led by traditional political parties (Haugbølle and Cavatorta Citation2011, 339–340). As the political transition progressed and political parties assumed power, however, revolutionary youth saw their demands dismissed or marginalised. Revolutionaries within Tunisia had previously been proponents of transitional justice to hold perpetrators of crimes under the former regime accountable, an initiative also originally supported by the Troika. In 2013, the Truth and Dignity Commission was founded to develop official processes and procedures towards this end. However, by the time its final report was published in 2020, political elites’ momentum and enthusiasm for the process had halted. Ennahda, which had previously supported an ‘Immunisation of the Revolution’ law to prevent Ben Ali-era politicians from holding political office, allied with Nidaa Tounes; the latter’s ranks included many stalwarts from the former regime. Former president and Nidaa Tounes leader Beji Caid Essebsi was even posthumously alleged by the Truth and Dignity Commission’s report to have partaken in torture (Ahmed Citation2019). The cost of this new consensus had been the abandonment of transitional justice for national healing. Nidaa Tounes and Ennahda together supported the Economic Reconciliation Act, which pardoned those accused of economic misconduct under the former regime. According to Amel Boubekour (Citation2016), the Nidaa Tounes-Ennahda alliance was an indicator of the closure of political sphere to outsiders and the institutionalisation of an elite class. For certain Islamists and secularists, it represented an ideological betrayal (Marks Citation2018, 103; Meddeb Citation2019, 14, 19). Trust in politicians declined; in 2019, the International Republican Institute’s poll found that 55% of Tunisians expressed ‘a great deal’ of distrust for political parties (International Republican Institute Citation2019, 49).

An even more pressing grievance was the state of the economy. The original spark of Tunisia’s 2010–2011 Jasmine Revolution may have been police corruption and brutality, but the movement quickly came to encompass a wide range of economic grievances, including the marginalisation of the interior, high youth unemployment and poverty. By 2019, however, the condition of most of these issues had failed to improve or even deteriorated. According to the Tunisian Institute for Strategic Studies, the percentage of middle-class families had declined between 2010–2018 from 70% to 55% (The Arab Weekly Citation2020). 72% of Tunisians by 2018 had come to see the national economic situation as ‘fairly bad’ or ‘very bad’ (Meddeb Citation2018, 2). Youth unemployment remained high (33.2% in 2018, compared to 26.7% in 2010), which was most acutely experienced in already marginalised regions (Mouley and Elbeshbishi Citation2021). Overall preferences for democracy sharply declined between 2013 and 2018 (Meddeb Citation2018, 2). In 2020, the overwhelming majority of Tunisians reported experiencing the effects of corruption (Yerkes and Mbarek Citation2021).

In the context of this disconnect between revolutionary expectations and the contours of the post-revolutionary reality, Itilaf al-Karama and the Parti Destourien Libre came to political prominence. The frames advanced by each actor spoke to endemic popular disillusionment surrounding the elite bargain that had bought stability at the price of systemic change.

Islamist populism: Itilaf al-Karama

Itilaf al-Karama (henceforth IK) was formed in 2019. Its stated mission was to correct the revolutionary trajectory, which the coalition argued had been stalled and led astray. The coalition was headed by Seifeddine Makhlouf, a lawyer whose controversial career had included the provision of legal representation to individuals accused of terrorism, acquiring the nickname ‘the lawyer of terrorists’ (‘l’avocat des terroristes’) (Lafrance Citation2019). Other prominent personages included Islamist blogger Maher Zid, former preachers Rida al-Jawadi and Mohamed al-Afas, and Imed Dghij, a former regional leader for the Leagues for the Protection of the Revolution, a grassroots revolutionary organisation.

The coalition’s performance in the 2019 parliamentary elections – having won 21 seats – was impressive for political newcomers. It can be explained in part through the IK’s blend of conservative identity politics with revolutionary fervour. Receiving endorsements from conservative Salafi religio-political actors and revolutionary groups like the Leagues for the Protection of the Revolution (Ḥizb Jabhat al-ʾIṣlāḥ al-Ṣafḥah al-Rasmiyyah Citation2019; I’tilāf al-Karāmah al-Ṣafḥah al-Rasmiyyah Citation2019f), the coalition directly addressed the compromises and capitulations given by institutionalised political Islamic actors like Ennahda towards the secular current. Its diagnostic frame presented a continuous history from Tunisia’s colonial past to a present marked by theft and exploitation, its prognostic frames urged rejecting the politics of consensus in favour of decisive action, and its motivational frames emphasised the risk assumed by the coalition’s members as they defended the Tunisian people at great personal cost.

Diagnostic frame

The present disillusionment experienced by Tunisians was contextualised within a larger historical narrative in Itilaf al-Karama’s diagnostic frame. The coalition emphasised the humiliation and exploitation persisting from colonialism into the post-independence era. This targeted Habib Bourguiba, Tunisia’s first president, and the modernist project that he spearheaded. Makhlouf argued against Bourguiba’s glorification, stating that the former president’s true legacy was having made Tunisia an ‘underdeveloped country’ (Business News Citation2019); other IK members stated that they considered the country ‘semi-occupied’ even after independence (I’tilāf al-Karāmah al-Ṣafḥah al-Rasmiyyah Citation2019h). Active contracts over Tunisia’s resources dating from before independence were condemned as exploitation (Lafrance Citation2019). France presented as a particular target of this frame, but vitriol was similarly assigned to Tunisian authorities considered complicit; IK members excoriated post-revolutionary politicians for acting in self-interest at the expense of the people (I’tilāf al-Karāmah al-Ṣafḥah al-Rasmiyyah Citation2019b).

In addressing the post-revolutionary political situation, IK’s diagnostic frames emphasised the danger stemming from further degradation of the country’s national sovereignty and its citizens’ rights through institutional corruption. IK members articulated reminders that the former regime and its destabilising tendencies remained a strong threat (I’tilāf al-Karāmah al-Ṣafḥah al-Rasmiyyah Citation2019e). Clampdowns on Islamist mobilisation in the wake of terrorist attacks were cast as pretexts for restrictions on freedom (Galtier Citation2019). The coalition frequently warned of plots designed to target its activities (I’tilāf al-Karāmah al-Ṣafḥah al-Rasmiyyah Citation2020d). The Parti Destourien Libre formed a particular target in IK’s diagnostic frames, where it was portrayed as an actor working for Emirati or Egyptian interests by ‘targeting the glorious Tunisian revolution’ (I’tilāf al-Karāmah al-Ṣafḥah al-Rasmiyyah Citation2020b). The mainstream media was also considered to exhibit deep biases against IK and was therefore unable to be trusted (I’tilāf al-Karāmah al-Ṣafḥah al-Rasmiyyah Citation2020c).

Prognostic frame

Facing this dire situation, IK argued in their prognostic frame for the participation of political outsiders who had already proven their commitment to Tunisia’s religious identity and sovereignty (e.g. I’tilāf al-Karāmah al-Ṣafḥah al-Rasmiyyah Citation2019g; I’tilāf al-Karāmah al-Ṣafḥah al-Rasmiyyah Citation2019k). The individuals on IK’s electoral roster were valorised for their disinclination towards institutional politics. Abdullatif al-Alawi, an IK MP, wrote that he had defended the revolution for years, yet now felt a ‘duty’ to wade through the political ‘mud’ to accomplish its goals (I’tilāf al-Karāmah al-Ṣafḥah al-Rasmiyyah Citation2019a). Needed were politicians external to the entrenched political class, immune to the temptations of power and privilege. As Al-Alawi reminded, ‘there is no success for any democratic project, nor any plan of development, nor any cultural flourishing without a comprehensive project for national liberation’ (I’tilāf al-Karāmah al-Ṣafḥah al-Rasmiyyah Citation2019h).

The role that the coalition assumed was one of raising awareness, as well as providing defence and protection. IK MP Habib Bensidhom expressed the historic significance of Makhlouf’s public demands for France’s accountability; he analogised leaving colonial legacies unresolved to looking into a woman’s eyes ‘you know you are unable to protect’ (I’tilāf al-Karāmah al-Ṣafḥah al-Rasmiyyah Citation2019i). For IK, this protection entailed direct action both within and without the Assembly of the Representatives of the People (ARP). IK responded to the PDL’s sit-in at the International Union of Muslim Scholars by engaging in a counter-mobilisation to defend the Union (Al-ʿArabī al-Jadīd Citation2021). The coalition also confronted security forces preventing a woman from travelling under terrorism-related restrictions at Tunis-Carthage airport (L’Economiste Maghrébin Citation2021). Indeed, confrontation – rather than compromise – was exalted within IK’s prognostic frames to achieve revolutionary goals and so disrupt Tunisia’s long history of elite exploitation (I’tilāf al-Karāmah al-Ṣafḥah al-Rasmiyyah Citation2019j). As IK MP Maher Trabelsi argued in response to those calling for more accommodationist measures, ‘history says that this path did not succeed in the last sixty years of our history’ (I’tilāf al-Karāmah al-Ṣafḥah al-Rasmiyyah Citation2019j).

Motivational frame

IK drew upon an elite-people populist narrative for its motivational frame, where the people were defined through the predation and oppression which they had experienced. Dignity, the coalition’s name, became juxtaposed with humiliation and theft. In IK’s rhetoric, dignity was the antithesis to the current landscape of corruption and inequality; it entailed a state of being where the country’s wealth and resources were protected, religious identity received respect and citizens would be spared the current ‘humiliation’ they faced at security centres (I’tilāf al-Karāmah al-Ṣafḥah al-Rasmiyyah Citation2019d). In contrast, the coalition defined itself as ‘Tunisian Arab Muslims, wholeheartedly proud of our religion, our language and our country’ (I’tilāf al-Karāmah al-Ṣafḥah al-Rasmiyyah Citation2019c). This was cast as a rebirth, with the coalition’s political programme defined by one member as a ‘restoration’ in the tradition of those who ‘built the message of Islam to serve humanity’ (I’tilāf al-Karāmah al-Ṣafḥah al-Rasmiyyah Citation2020a).

The entry of IK into the political scene heralded a new kind of politics. Criticisms levelled at IK members like Makhlouf for being emotional were presented as points in his favour. In fact, Trabelsi questioned the expectation that one should remain unemotional in the face of inequity, and exalted Makhlouf for proudly representing the country’s Muslim identity (I’tilāf al-Karāmah al-Ṣafḥah al-Rasmiyyah Citation2019j). The norms of elite politics were thus framed as a means by which to conceal injustice – which, the coalition implied, should incite strong feelings and preclude compromise.

Anti-Islamist populism: the Parti Destourien Libre

The direct predecessor to the Parti Destourien Libre (henceforth PDL), the Destourien Movement, was established after the revolution by former Prime Minister Hamed Karoui. It had been unsuccessful in the 2014 elections, as it was outperformed in anti-Islamist sentiment by Nidaa Tounes (Wolf Citation2020). Its subsequent rebrand offered a new name – the Parti Destourien Libre – and centred its charismatic new leader, Abir Moussi, a lawyer notorious for having unsuccessfully mounted a legal defence on behalf of the former ruling party, the RCD, against dissolution (Wolf Citation2020). After a series of internal crises within Nidaa Tounes, the 2019 elections saw the PDL gain 17 seats in the ARP.

The Parti Destourien Libre took its name and anti-Islamist orientation from Bourguiba’s modernist project. Under Moussi, the party sought to rehabilitate the nation’s Bourguibist past in contradistinction to its post-2011 trajectory. This came to focus significantly on the post-2011 rise of Islamism, which Moussi argued had destabilised the country and impoverished its citizens. The politics of spectacle adopted by Moussi – such as bringing a megaphone into Parliament or donning a bullet-proof vest and helmet to highlight the danger she claimed to operate under – bolstered her diagnostic threat frames. In return, the prognostic frame she advanced vowed to restore security through expelling the so-called Islamist menace. Her motivational frames emphasised her selflessness in defence of the country’s sovereignty and her determination to restore its glorious past.

Diagnostic frame

The PDL’s rhetoric blamed the revolution for Tunisia’s troubles. In Moussi’s words, ‘[t]he average Tunisian now finds himself worse off than he was before’ (Yee Citation2021); she called the current nation a ‘beggar country that lives on a drip’ (Lahbib Citation2021). The 2010–2011 revolt, which she dubbed a ‘fake revolution’, was implicated in degrading living conditions and national sovereignty (Moussi Citation2019a). In her view, this was no mere correlation: Moussi portrayed the revolution as a Qatari-Turkish plot hatched to destabilise the country (Luck Citation2020). The Troika government was blamed for incurring debts which crippled the middle class and, by becoming beholden to foreign powers, imperilled national sovereignty (Moussi Citation2019b). She further accused the Islamist party, Ennahda – without substantiation – of being legalised under false pretenses, sacrificing the country’s interests to the agendas of foreign funders and maintaining connections with terrorists (Naar Citation2020; Moussi Citation2019c; Moussi Citation2020c).

Itilaf al-Karama also played a prominent role within PDL discourse. Moussi accused the coalition of acting as the violent apparatus of the Muslim Brotherhood, as she calls Ennahda (Moussi Citation2020b). In her view, the coalition was guilty of spreading takfiri discourse (a term referring to the act of pronouncing another Muslim an apostate, often functioning as a prelude to violence (Beutel et al. Citation2017, 3–4)). She warned that parties had already begun to divide along the lines of ‘infidel and Muslim’, which could spiral into a civil war (Al-Shāriʿ al-Maghāribī Citation2020).

It was not only Islamists targeted by the PDL’s diagnostic frames. All institutions in the post-revolutionary era were seen as corrupted by their influence. Moussi placed herself in ‘total opposition’ to almost every aspect of how the country was governed (Lahbib Citation2021). Moussi claimed that Turkish, Qatari and Libyan Islamists’ agendas had infiltrated the ARP and excoriated the elected assembly for issuing the ‘laws of terrorists’ (AW Staff Citation2020; Parti Destourien Libre Citation2021b). Those who sought compromise with Islamists were viewed scarcely more favourably. The National Dialogue, which brokered the 2014 transfer of power from the Troika to a technocratic government and helped participate in normalising the policy of consensus, was criticised for even engaging with Islamists (Lahbib Citation2021). In Moussi’s view, those working for any less than the exclusion of political Islam betrayed the nation (Moussi Citation2021a).

Prognostic frame

As a prognostic frame, Moussi called for an ‘Enlightenment Revolution’ entailing the exclusion of religious political parties, amongst other governmental reforms (Tunis Now Citation2020). Essentially, this amounted to a restoration of the Bourguibist state-centric modernisation project, instilling ‘respect for the law’ (Lahbib Citation2021). The Tunisia she wanted to recreate would be ‘prosperous, sovereign and respected’ (Lahbib Citation2021).

In the meantime, like Itilaf al-Karama, she promised a politics of contention and disruption. On one level, this action was materially aimed to stall Islamists’ political goals, as Moussi acknowledged that with its current numbers, her party could not legislatively cripple the Islamist agenda (Lahbib Citation2021). Another aim was to publicly discredit and smear her opponents; she openly claimed that Ennahda benefitted from foreign funding sources (Naar Citation2020). The PDL’s sit-in against the Union of Muslim Scholars, which IK counter-protested, formed part of a larger campaign against Islamists’ alleged foreign funding and promotion of terrorism, as did its call to classify the Muslim Brotherhood as a terrorist organisation (Parti Destourien Libre Citation2020a; Parti Destourien Libre Citation2020b; Parti Destourien Libre Citation2021a; Moussi Citation2021c).

Motivational frame

Moussi portrayed her party as representing the desires of the ‘people’ who rejected political Islam and yearned for prosperity. The people did not want Islamist leadership, she argued (Lahbib Citation2021). Instead, her motivational frames lionised the Bourguibist project and valorised the pre-revolutionary era for its celebration of national pride and its state of security. She frequently lauded Bourguiba’s fight for national independence (e.g. Moussi Citation2020a); the RCD, the former governing party which Moussi defended, was partially rehabilitated as the ‘heir of the Destourien movement’ which ‘liberated Tunisia and built the national state’ (Lahbib Citation2021). Her rhetoric invoked a sense of historical scale: she claimed that the PDL could restore the country’s ‘glorious history’, with the post-revolutionary period elapsing to merely a ‘parenthesis’ (Moussi Citation2019d). Her vision, she reminded, was a ‘dream that can be achieved, not a false dream’ (Al-Shāriʿ al-Maghāribī Citation2020). However, for its realisation, the present moment was both urgent and pivotal. She warned that ‘history will not show mercy’ to those who failed to act and thus cost Tunisia the chance of salvation (Moussi Citation2019c).

Threats and urgency formed significant components within her motivational frames. Moussi frequently claimed that she specifically was targeted by Islamist violence. She alleged the existence of assassination plots against her and stated that she was being tracked and singled out in particular due to her gender (Arabi21 Citation2020; Moussi Citation2021b; Lahbib Citation2021). In the face of this danger, her role as the voice of the people was cast as especially heroic: ‘they can kill me, there will be thousands of other Abir Moussis’, she declared (Business News Citation2020a).

Discussion: a theory of polarised populist reinforcement

When addressing the political discontent and disillusionment commonplace amongst the Tunisian populace by 2019, there emerged two ways to explain the frustration of revolutionary aims. One was to posit the revolution as a positive project which had been sabotaged by elite machinations, and the other was to portray the revolution itself as a plot contrived by enemies of the country. Itilaf al-Karama adopted the former explanation, and the Parti Destourien Libre claimed the latter.

Despite being diametrically opposed ideologically, these two narratives hold remarkable similarities. Both Itilaf al-Karama and the Parti Destourien Libre invoke the spectre of an elite-driven plot in their diagnostic frames. However, their orientation on the Islamist-secularist spectrum lead them to implicate the other as the culprit. Itilaf al-Karama blames the secular forces of the former regime for derailing the revolutionary project; the Parti Destourien Libre indicts the Islamist-linked 2010–2010 revolution. As such, their prognostic frames argue for a direct confrontation with their political opponents, with no compromise permitted. The motivational frames adopted by each actor in turn emphasise the risk assumed by their side for the sake of the nation, implying that the other is dangerous as well as corrupt in their quest to destabilise the country ().

What led to this development? Previous literature on why Islamists and secularists compete might suggest that they held different incentives to ingratiate themselves with more institutionally powerful actors. It is true that Itilaf al-Karama did engage in forming a government with the more mainstream Islamist party, Ennahda, and might have been incentivised to act as a more ideologically inflexible counterpart to larger, more accommodating Islamist party. However, Itilaf al-Karama’s confrontational, controversial political style ran counter to the conciliatory face that Ennahda sought to present as part of its own moderation strategy. Similarly, the Parti Destourien Libre’s deliberate self-marginalisation by excoriating all parties who accepted Islamist political participation damaged its chances of forming a political alliance. In facing political marginalisation, the existing literature on Islamist-secularist relations would rather suggest that this background provides an opportunity for cooperation. Instead, the scapegoating that each actor sought to employ in its threat framing implicating the Other seemed to be a more direct response to partisan disillusionment resulting from the perceived ideological betrayals of the 2014 Islamist-secularist Ennahda-Nidaa Tounes alliance, instrumentalising prior lines of polarisation rather than seeking to contest or transcend them .

Table 1. A table comparing the common themes shaping the diagnostic, prognostic and motivational frames of Itilaf al-Karama and the Parti Destourien Libre.

In this context, each party’s threat frames become mutually reinforcing. Together, they co-constitute the dynamic which pits Bourguibist secularism against revolutionary Islamism. Both Itilaf al-Karama and the Parti Destourien Libre begin their political trajectory by basing themselves on opposing ends of an ideological spectrum. Itilaf al-Karama epitomises the religio-revolutionary extremity; the Parti Destourien Libre is its Bourguibist secularist counterpart. In adopting populist themes, however, their threat narratives implicating the other sharpen. Criticisms of political opponents’ issue positions morph into accusations of foreign collaboration which threaten the country’s sovereignty. As such, confrontation is advanced in prognostic frames, with actors who do seek to compromise dismissed as misguided or even maligned. Motivational frames emphasising the risks each populist actor assumes warn of the ruthlessness of the other, who refuses to commit to norms of politics or even basic morality and normative patriotic duty. The embrace of disruption encoded in each populist actor’s prognostic frame lends succour to the diagnostic narratives of the other that posit their opponents as derailing the country’s well-being .

At its core, this competition gradually entails a contestation over who could define the ‘people’, and concurrently who possesses the epistemic authority of assigning blame for the current socioeconomic and political grievances. The frames advanced by Itilaf al-Karama and the Parti Destourien Libre contribute to the formation of two mutually contradictory worldviews. Itilaf al-Karama positions the revolution as a step in a longer anti-colonial struggle for sovereignty and dignity. In contrast, the Parti Destourien Libre glorifies the pre-revolutionary past. The divergence in political positions correlates to a widening divergence in how historical memory is experienced. Was the pre-revolutionary era – and the Bourguibist legacy – a time of prosperity and security, or a continuation of colonial oppression? As the polarisation process progresses, there remains little room for overlap or nuance between these mutually exclusive worldviews.

The dialogic process between these two polarised populisms confirms and strengthens the entrenched worldview of each actor. The diagnostic frames of each polarised populist may emanate from real discontent over the distance between political elites and the populace, but the accelerating proceedings of actions and counteractions lead to further alienation across the political spectrum. In initially identifying and responding to similar grievances, these parallel frames do not bring rapprochement, but rather invite an intensification of exclusionary rhetoric normalising contention as a political mode.

Acknowledgments

An earlier draft of this paper was presented at the 2021 Amsterdam Graduate Conference in Political Theory; I thank all participants who offered thoughtful commentary and suggestions. I also thank my supervisor, Dr Adham Saouli for his feedback on a prior version of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ahmed, Nada. 2019. “An Uphill Battle: The Truth and Dignity Report and Transitional Justice in Tunisia.” The Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy, 21 August. https://timep.org/commentary/analysis/an-uphill-battle-the-truth-and-dignity-report-and-transitional-justice-in-tunisia-2/.

- Al-ʿArabī al-Jadīd. 2021. “Tūnis: iqtiḥām maqarr ittiḥād al-ʿulamāʿ al-muslimīn yuthīr makhāwif min tanāmī al-ʿunf.” Al-ʿArabī al-Jadīd, 10 March. https://www.alaraby.co.uk/politics/تونس-اقتحام-مقر-اتحاد-العلماء-المسلمين-يثير-مخاوف-من-تنامي-العنف.

- Al-Shāriʿ al-Maghāribī. 2020. “Al-Munastīr: ʿAbīr Mūsi taftatiḥ “thawrat al-tanwīr” wa taṭraḥ nafsahā li-qiyādat mawjat al-ghaḍab al-shaʿbī.” Al-Shāriʿ al-Maghāribī, 19 December. https://acharaa.com/غير-مصنف/المنستير-عبير-موسي-تفتتح-ثورة-التنوي/.

- Arabi 21. 2020. “Man hiya ʿAbīr Mūsi allatī takhṭaf al-ʾaḍwāʾ fī Tūnis?” Arabi 21, 15 June. https://arabi21.com/story/1278369/من-هي-عبير-موسى-التي-تخطف-الأضواء-في-تونس.

- The Arab Weekly. 2020. “Tunisia’s atrophying middle class swells ranks of the poor.” The Arab Weekly, 7 September. https://thearabweekly.com/tunisias-atrophying-middle-class-swells-ranks-poor.

- AW Staff. 2020. Ghannouchi’s contacts with Turkey, Qatar stir controversy in Tunisia. The Arab Weekly, 8 May. https://thearabweekly.com/ghannouchis-contacts-turkey-qatar-stir-controversy-tunisia.

- Beaumont, Peter. 2019. “Tunisian exit polls suggest shock victory for political outsiders.” The Guardian, 15 September. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/sep/15/its-all-lies-tunisia-heads-to-the-polls-amid-widespread-disillusionment.

- Benford, Robert D., and David A Snow. 2000. “Framing Processes and Social Movements: An Overview and Assessment.” Annual Review of Sociology 26: 611–639.

- Beutel, Alejandro, William Braniff, Bria Ballard, and Christopher Lee. 2017. “Debates among Salafi Muslims about use of violence.” START: National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, Summary Report. Accessed 15 May, 2022. https://www.start.umd.edu/pubs/START_DebatesAmongSalafiMuslimsAboutViolence_SummaryReport_May2017.pdf.

- Blassnig, Sina, Nicole Ernst, Florin Büchel, Sven Engesser, and Frank Esser. 2019. “Populism in Online Election Coverage.” Journalism Studies 20 (8): 1110–1129.

- Boubekour, Amel. 2016. “Islamists, Secularists and Old Regime Elites in Tunisia: Bargained Competition.” Mediterranean Politics 24 (1): 107–127. doi:10.1080/13629395.2015.1081449.

- Buehler, Matt. 2018. Why Alliances Fail: Islamist and Leftist Coalitions in North Africa. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press.

- Business News. 2019. “Seif Eddine Makhlouf: Bourguiba a fait de la Tunisie un pays sous-développé!” Business News, 3 November. Available at: https://www.businessnews.com.tn/seif-eddine-makhlouf–bourguiba-a-fait-de-la-tunisie-un-pays-sous-developpe,520,92461,3.

- Business News. 2020. “Abir Moussi: si on m’assassine, des milliers d’autres Moussi prendont la relève!” Business News, 17 January. https://www.businessnews.com.tn/abir-moussi–si-on-massassine-des-milliers-dautres-moussi-prendront-la-releve,520,94502,3.

- Casani, Alfonso. 2020. “Cross-Ideological Coalitions under Authoritarian Regimes: Islamist-Left Collaboration among Morocco’s Excluded Opposition.” Democratization 27 (7): 1183–1201. doi:10.1080/13510347.2020.1772236.

- Clark, Janine A. 2006. “The Conditions of Islamist Moderation: Unpacking Cross-Ideological Cooperation in Jordan.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 38 (4): 539–560. doi:10.1017/S0020743806412460.

- Dejoui, Nadia. 2020. “Abir Moussi vs Seifeddine Makhlouf, qu’en pensent les observateurs?” L’Economiste Maghrébin, 5 October. https://www.leconomistemaghrebin.com/2020/10/05/abir-moussi-vs-seifeddine-makhlouf-quen-pensent-les-observateurs/.

- Enyedi, Zsolt. 2016. “Populist Polarization and Party System Institutionalization.” Problems of Post-Communism 63 (4): 210–220. doi:10.1080/10758216.2015.1113883.

- Galtier, Mathieu. 2019. “Tunisie: la coalition al-Karama, un mistigri islamiste au Parlement.” Middle East Eye, 29 October. https://www.middleeasteye.net/fr/reportages/tunisie-la-coalition-al-karama-un-mistigri-islamiste-au-parlement.

- Ghanmi, Lamine. 2019. “Tunisia faces aftershocks of populists’ triumph in presidential election.” The Arab Weekly, 21 September. https://thearabweekly.com/tunisia-faces-aftershocks-populists-triumph-presidential-election.

- Grewal, Sharan. 2019. “Political outsiders sweep Tunisia’s presidential elections.” Brookings, Accessed 9 May, 2022. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2019/09/16/political-outsiders-sweep-tunisias-presidential-elections/.

- The Guardian. 2014. The Guardian view on Tunisia’s transition: a success story. The Guardian, 26 December. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/dec/26/guardian-view-tunisia-transition-success-story.

- Haugbølle, Rikke Hostrup, and Francesco Cavatorta. 2011. “Will the Real Tunisian Opposition Please Stand Up? Opposition Coordination Failures Under Authoritarian Constraints.” British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 38 (3): 323–341. doi:10.1080/13530194.2011.621696.

- International Republican Institute. 2019. “Public Opinion Survey: Residents of Tunisia, January 25-February 11, 2019.” Center for Insights in Survey Research, Accessed 10 May, 2022. https://www.iri.org/wp-content/uploads/legacy/iri.org/wysiwyg/final_-_012019_iri_tunisia_poll.pdf.

- I’tilāf al-Karāmah al-Ṣafḥah al-Rasmiyyah. 2019a. “Wa-naḥnu ʿalā ‘aʿtāb maḥaṭṭah jadīdah fāriqah fī masīrat thawratinā al-mutaʿtharah […]” Facebook, 10 April. https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid = 353498385284032&id = 323675788266292.

- I’tilāf al-Karāmah al-Ṣafḥah al-Rasmiyyah. 2019b. “Lam ‘ataraddad wa law lil-laḥẓah wāḥidah”. Facebook, 11 April. https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid = 353978505236020&id = 323675788266292.

- I’tilāf al-Karāmah al-Ṣafḥah al-Rasmiyyah. 2019c. “I’tilāf al-Karāmah […]” Facebook, 21 April. https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid = 358126411487896&id = 323675788266292.

- I’tilāf al-Karāmah al-Ṣafḥah al-Rasmiyyah. 2019d. “‘Akhī al-tūnisī, ‘ukhtī al-tūnisiyyah […]” Facebook, 12 May. https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid = 368382467128957&id = 323675788266292.

- I’tilāf al-Karāmah al-Ṣafḥah al-Rasmiyyah. 2019e. “Bayān.” Facebook, 30 May. https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid = 377010759599461&id = 323675788266292.

- I’tilāf al-Karāmah al-Ṣafḥah al-Rasmiyyah. 2019f. “ʿAn munāḍilī al-rābiṭah al-waṭaniyyah li-ḥimāyat al-thawrah.” Facebook, 15 June. https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid = 385733472060523&id = 323675788266292.

- I’tilāf al-Karāmah al-Ṣafḥah al-Rasmiyyah. 2019g. “Al-’ustādh al-shaykh Riḍā al-Jawādī ra’īs qā’imat Sfāqs 1 li-’tilāf al-Karāmah […]” Facebook, 15 July. https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid = 401656077134929&id = 323675788266292.

- I’tilāf al-Karāmah al-Ṣafḥah al-Rasmiyyah. 2019h. “Baʿḍ al-nās ẓannū ‘anna inṭilāq ḥamlatinā min ‘amām maqarr al-muqīm al-ʿām al-faransiyy kānat mujarrad ḥarakah diʿā’iyyah […]” Facebook, 3 September. https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid = 427039101263293&id = 323675788266292.

- I’tilāf al-Karāmah al-Ṣafḥah al-Rasmiyyah. 2019i. “Ha’uwalā’ alladhīna turabbū ʿalā falsafat al-gharb lā yaḥtaramūn ʿadwan ḍaʿīfan […]” Facebook, 4 September. https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid = 427456187888251&id = 323675788266292.

- I’tilāf al-Karāmah al-Ṣafḥah al-Rasmiyyah. 2019j. “Hādhā baʿḍ mā yuqāl ʿannā. Wa hādhā raddunā.” Facebook, 11 September. https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid = 431921274108409&id = 323675788266292.

- I’tilāf al-Karāmah al-Ṣafḥah al-Rasmiyyah. 2019k. “Al-tārīkh ‘aʿdal qādin fī zaman al-nikrān […]” Facebook, 13 December. https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid = 499226104044592&id = 323675788266292.

- I’tilāf al-Karāmah al-Ṣafḥah al-Rasmiyyah. 2020a. “‘Tawḍīḥāt ḥawl I’tilāf al-Karāmah […]’” Facebook, 9 March. https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid = 559282601372275&id = 323675788266292.

- I’tilāf al-Karāmah al-Ṣafḥah al-Rasmiyyah. 2020b. “Bism Allāh al-Raḥman al-Raḥīm.” Facebook, 17 July. https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid = 640347646599103&id = 323675788266292.

- I’tilāf al-Karāmah al-Ṣafḥah al-Rasmiyyah. 2020c. “Tataʿraḍ kutlat I’tilāf al-Karāmah ‘ilā ḥamlah ‘iʿlāmiyyah sharsah wa munaẓimah wa mumanhajah […]” Facebook, 9 September. https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid = 677291062904761&id = 323675788266292.

- I’tilāf al-Karāmah al-Ṣafḥah al-Rasmiyyah. 2020d. “Taḥrīd ʿalā al-ʿunf min ṭaraf qiyādāt ittiḥād al-shaʿl […]” Facebook, 13 December. https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v = 563277577965055.

- Ḥizb Jabhat al-ʾIṣlāḥ al-Ṣafḥah al-Rasmiyyah. 2019. “Bism Allāh al-Raḥmān al-Raḥīm.” Facebook, 15 June. https://www.facebook.com/360973397278612/photos/pb.100064541206138.−2207520000../2991917487517510/?type = 3.

- Kapitalis. 2021. “Violence au Parlement: Abir Moussi porte plainte contre Seifeddine Makhlouf.” Kapitalis, 1 February. https://kapitalis.com/tunisie/2021/02/01/violence-au-parlement-abir-moussi-porte-plainte-contre-seifeddine-makhlouf/.

- Lafrance, Camille. 2019. “Tunisie: Seifeddine Makhlouf, <<l’avocat des terroristes>> devenu l’un des nouveaux acteurs du Parlement.” Jeune Afrique, 20 December. https://www.jeuneafrique.com/870594/politique/tunisie-seifeddine-makhlouf-lavocat-des-terroristes-devenu-lun-des-hommes-forts-du-parlement/.

- Lahbib, Hella. 2021. “Abir Moussi, Présidente du Parti Destourien Libre et députée, à La Presse: .” La Presse, 19 May. https://lapresse.tn/97459/abir-moussi-presidente-du-parti-destourien-libre-et-deputee-a-la-presse-la-tunisie-est-un-pays-mendiant-qui-vit-sous-perfusion/.

- L'Economiste Maghrébin. 2021. “Seif Eddine Makhlouf provoque un scandale à l'Aéroport Tunis-Carthage.” L'Economiste Maghrébin, 15 March. https://www.leconomistemaghrebin.com/seif-eddine-makhlouf-provoque-un-scandale-a-laeroport-decarthage/.

- Lelkes, Yphtach. 2018. “Affective Polarization and Ideological Sorting: A Reciprocal, Albeit Weak, Relationship.” The Forum 16 (1): 67–79. doi:10.1515/for-2018-0005.

- Luck, Taylor. 2020. “Pandemic-fueled populism stresses Tunisia’s fragile democracy.” The Christian Science Monitor, 22 December. https://www.csmonitor.com/World/Middle-East/2020/1222/Pandemic-fueled-populism-stresses-Tunisia-s-fragile-democracy.

- Marks, Monica. 2018. “Purists and Pluralists: Cross-Ideological Coalition Building in Tunisia’s Democratic Transition.” In Democratic Transition in the Muslim World, edited by Alfred Stepan, 91–119. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Masbah, Mohammed. 2014. “Islamist and Secular Forces in Morocco: Not a Zero-Sum Game.” Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, German Institute for International and Security Affairs: 1-8. https://www.swp-berlin.org/publications/products/comments/2014C51_msb.pdf.

- Masri, Safwan M. 2018. Tunisia: An Arab Anomaly. New York: Columbia University Press.

- McCoy, Jennifer, Tahmina Rahman, and Murat Somer. 2018. “Polarization and the Global Crisis of Democracy: Common Patterns, Dynamics, and Pernicious Consequences for Democratic Polities.” American Behavioral Scientist 62 (1): 16–42. doi:10.1177/0002764218759576.

- Meddeb, Youssef. 2018. “Support for democracy dwindles in Tunisia amid negative perceptions of economic conditions.” Afrobarometer, Dispatch No. 232: 1-12. https://afrobarometer.org/sites/default/files/publications/Dispatches/ab_r7_dispatchno232_support_for_democracy_dwindles_in_tunisia_1.pdf.

- Meddeb, Hamza. 2019. “Ennahda’s Uneasy Exit from Political Islam.” Carnegie Middle East Center, Series on Political Islam: 1-23. https://carnegieendowment.org/files/WP_Meddeb_Ennahda1.pdf.

- Meyer, David S, and Suzanne Staggenborg. 1996. “Movements, Countermovements and the Structure of Political Opportunity.” American Journal of Sociology 101 (6): 1628–1660.

- Mouley, Sami, and Amal Nagah Elbeshbishi. 2021. “Addressing Youth Unemployment through Industries Without Smokestacks: A Tunisia Case Study.” Brookings, AGI Working Paper 38. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Tunisia-IWOSS_final.pdf.

- Moussi, Abir. 2019a. “Ghadan ʿīd “thawratihim” al-muzayfah..[…]” Facebook, 13 January. https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid = 1968609150109624&id = 1967823173521555.

- Moussi, Abir. 2019b. “Nujaddid al-tamassuk bi-mawqifinā al-mabdaʾiyy […]” Facebook, 17 January. https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid = 1970483136588892&id = 1967823173521555.

- Moussi, Abir. 2019c. “Risālah ilā man yuhājimūn al-ḥizb al-dustūrī al-ḥurr […]” Facebook, 17 August. https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v = 220263222248704.

- Moussi, Abir. 2019d. “Ṣabāḥ al-khayr tūnis al-ḥabibah..[…]” Facebook, 14 November. https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid = 2157236194580251&id = 1967823173521555.

- Moussi, Abir. 2020a. “#Al-dhikrā_68_lil-thawrah_18_jānfī_1952.” Facebook, 14 January. https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid = 2212377455732791&id = 1967823173521555.

- Moussi, Abir. 2020b. “#Al-ʾamn_al-riʾāsiyy_masʾūl_ʿalā_ʾamn_al-barlamān.” Facebook, 30 June. https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid = 2337935266510342&id = 1967823173521555.

- Moussi, Abir. 2020c. “#Risālah_ilā_quwā_al-madaniyyah_allātī_ʾassasat_hayʾat_18_ʾuktūbir_2005_maʿ_al-ʾikhwān: […]” Facebook, 18 October. https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid = 2427554184215116&id = 1967823173521555.

- Moussi, Abir. 2021a. “Man yaʿlam ḥaqīqat al-Khwānjiyyah wa yaʿrif khuṭūratahum wa jarāʾimahum […]” Facebook, 21 January. https://www.facebook.com/AbirMoussiOfficielle/videos/249225676673664/.

- Moussi, Abir. 2021b. “#Nuqṭat_tanwīriyyat al-jumuʿat 16 ʾAfrīl 2021.” Facebook, 16 April. https://www.facebook.com/AbirMoussiOfficielle/videos/564124381230715/.

- Moussi, Abir. 2021c. “Al-ḥamd Allāh waḥdahu.” Facebook, 8 December. https://www.facebook.com/AbirMoussiOfficielle/posts/469824654500816.

- Mudde, Cas. 2004. “The Populist Zeitgeist.” Government and Opposition 39 (4): 541–563. doi:10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x.

- Naar, Ismaeel. 2020. “Tunisian party leader Abir Moussi: Muslim Brotherhood members receiving foreign funds.” AlArabiya, 16 June. https://english.alarabiya.net/News/north-africa/2020/06/16/Tunisian-party-leader-Abi-Moussi-Muslim-Brotherhood-members-receiving-foreign-funds.

- Parti Destourien Libre. 2020a. “Al- ḥamd lillāh waḥdahu.” Facebook, 8 June. https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid = 3230138497018165&id = 586691098029598.

- Parti Destourien Libre. 2020b. “Al-ḥamd li-lāh waḥdahu.” Facebook, 20 July. https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid = 3345812685450745&id = 586691098029598.

- Parti Destourien Libre. 2021a. Facebook, 12 March. https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid = 4021615517870455&id = 586691098029598.

- Parti Destourien Libre. 2021b. Facebook, 17 March. https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid = 4034743896557617&id = 586691098029598.

- Sika, Nadine. 2012. “Dynamics of a Stagnant Religious Discourse and the Rise of New Secular Movements in Egypt.” In Arab Spring in Egypt: Revolution and Beyond, edited by Bahgat Korany, and Rabab El-Mahdi, 63–82. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press.

- Tilly, Charles, and Sidney Tarrow. 2015. Contentious Politics. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Tunis Now. 2020. “ʿAbīr Mūsi takshif tafāsīl mubādarat “thawrat al-tanwīr”.” Tunis Now, 24 December. https://tunisnow.tn/عبير-موسي-تكشف-تفاصيل-مبادرة-ثورة-التن/.

- Wegner, Eva, and Miquel Pellicer. 2011. “Left-Islamist Opposition Cooperation in Morocco.” British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 38 (3): 303–322. doi:10.1080/13530194.2011.621690.

- Wilson, Anne E., Victoria A. Parker, and Matthew Feinberg. 2020. “Polarization in the Contemporary Political and Media Landscape.” Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 34: 223–228. doi:10.1016/j.cobeha.2020.07.005.

- Wolf, Anne. 2020. “Snapshot – The Counterrevolution Gains Momentum in Tunisia: The Rise of Abir Moussi.” POMED, 18 November. https://pomed.org/snapshot-the-counterrevolution-gains-momentum-in-tunisia-the-rise-of-abir-moussi/.

- Yee, Vivian. 2021. “In Tunisia, Some Wonder if the Revolution Was Worth It.” The New York Times, 19 January. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/19/world/middleeast/tunisia-protests-arab-spring-anniversary.html.

- Yerkes, Sarah, and Nesrine Mbarek. 2021. “After Ten Years of Progress, How Far Has Tunisia Really Come?” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 14 January. https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/01/14/after-ten-years-of-progress-how-far-has-tunisia-really-come-pub-83609.