ABSTRACT

The increasing sectarianization of the international relations of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) is a defining feature of the region’s contemporary politics. Iran has sought to increase its influence among Shi‘i populations of foreign countries, while Saudi Arabia and other Sunni regimes have moved to curtail it. In heterogeneous and polarized MENA societies, like Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq, where the Shi‘a constitute a sizable proportion of the population and compete for political power, it is natural to presume that sectarianization likely increases tension and prejudice against the Shi‘a. Yet, little is known about homogenous MENA societies, where the Shi‘a exist as an infinitesimal, uninfluential minority that does not seek political power. This topic is examined using an original, nationally-representative survey of 2,000 respondents in Morocco. We find that about 59 per cent of individuals express interpersonal prejudice against Moroccan Shi‘a, expressing discomfort at the prospect of having a Shi‘i neighbour. Such prejudice is counter-intuitive, given that Moroccan Shi‘a constitute a miniscule minority – less than .1 per cent of the population. We investigate three hypotheses concerning the sources of anti-Shi‘i prejudice, which locate them in social marginalization, religious beliefs and practices, and views about regional politics. The first two hypotheses are drawn from the existing literature, whereas the third is our unique theoretical contribution. Our results, which find support for the connection between individuals’ views about regional politics and anti-Shi‘i prejudice, advance scholarly understanding of religious diversity in the MENA, showing how international developments can trickle down into interpersonal relations to hinder the acceptance and tolerance of sectarian minorities.

An indisputably sectarian dimension exists in the international relations of today’s Mediterranean region, and also in the broader Middle East and North Africa (MENA). Vali Nasr’s (Citation2006, Citation2016) argument that the region’s politics would become increasingly dominated by a power struggle between Shi‘i (adjective; noun: Shi‘a) and Sunni Muslims following the U.S. invasion of Iraq appears vindicated. Proxy conflicts, including hot wars pitting Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Turkey, and other Sunni states against Iran and foreign Shi‘i militias are ongoing in multiple countries. Syria, Yemen, and Iraq are the most notable; civil wars have raged in all three for the last decade or longer (Leenders & Giustozzi, Citationin press; Darwich, Citation2020; Harding & Libal, Citation2019). Sectarian conflict has also occurred – albeit to a lesser extent – in Lebanon, where Iranian-allied Hezbollah confronts political parties aligned with Saudi Arabia (Fakhoury, Citation2019). In some countries of the northern shore of the Mediterranean, like Albania, Bosnia, and Bulgaria, Iran has sought to finance and recruit small cells to challenge elected governments of both Sunni and Orthodox Christian countries (Bardos, Citation2013, p. 60-66; Avramov & Trad, Citation2018; Ghodsee, Citation2009, p. 11). Iran has even sought to make inroads in influence in Greece, Italy, and France, via neighbourhoods of Muslim migrants (Triandafyllidou & Gropas, Citation2009, p. 962; Mirshahvalad, Citation2019; van den Bos, Citation2020, pp. 3–4). Perhaps most important, a regional power struggle persists between a Sunni bloc – Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, and others – and Iran regarding the latter’s nuclear programme (Calabrese, Citation2020). As Simon Mabon’s pathbreaking book (Citation2020, p. 237) insightfully observes, ‘the rejection of national identities, securitization of sectarian identities, and decision to view events through the lens of communitarian – or indeed sectarian interests – has created a political environment that contributes to the entrenchment and replication of division’.

The origins of sectarian conflict, domestic and international, are multifaceted. Some scholars suggest that the Sunni-Shi‘i rivalry could mask other, deeper cleavages in the MENA, like competition between monarchical and revolutionary regimes (Gause, Citation2019, pp. 576–578) or between client states of the great powers versus ambitious middle power countries (Saouli, Citation2019a). Others view it as a tool that autocratic regimes use to secure their survival (Gengler, Citation2017), particularly because it can help allied states coordinate against a common threat (Rubin, Citation2014; and, on leaders’ perception of threats, see Darwich, Citation2019). But its origins aside, the consequences of the sectarianization of international relations on ordinary citizens and for their everyday lives are under-studied.Footnote1 Little is known about how such international developments affect interpersonal relations between Sunni and Shi‘i populations.

Research on sectarianismFootnote2 – whether theoretically-oriented, focused on Middle Eastern societies, or countries in other regions – has examined both inter-sect and intra-sect relations (Horowitz, Citation2000; Bishārah, Citation2018; Crow, Citation1962; Binder, Citation1966; Suleiman, Citation1967; Khalaf, Citation1968; Nelson, Citation1984; Brewer, Citation1992; Hanf, Citation1993; O’Duffy Citation1995; Fearon & Laitin, Citation1966; van Dam, Citation1996; White, Citation1997; Zaman, Citation1998; Asmar et al., Citation1999; Nasr, Citation2000; English, Citation2003; Cammett, Citation2014; Abdo, Citation2017; Corstange Citation2016; Hashemi & Postel, Citation2017; Hoffman & Nugent, Citation2017; O’Leary, Citation2019; Haddad, Citation2020b). When it comes to the MENA, existing literature has focused predominately on already-polarized countries, in which Shi‘i factions either compete for or control political power over the state (Haddad, Citation2011; Matthiesen, Citation2013; Freer, Citation2019; Hafidh & Fibiger, Citation2019; Hinnebusch, Citation2020; Rizkallah et al., Citation2019; Saouli, Citation2019b).Footnote3 The general consensus is that tensions flare and relations become more fraught as the sectarian dimension’s salience in international relations increases.

Yet with sectarianism becoming so entrenched in regional politics of the Mediterranean, it may be necessary to shift the study of this topic beyond divided societies into societies where the sectarian dimension is not perceived as salient in domestic politics because society is homogenous. With the notable exceptions of Lebanon, Syria, and Turkey, where Shi‘a make up respectively about 28, 13, and 16 per cent of the local population, the remaining Muslim-majority countries of the Mediterranean – Albania, Algeria, Bosnia, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, Palestine, and Tunisia – are overwhelmingly Sunni. Indeed, Shi‘i individuals never constitute more than five percent of Muslims in any of these countries (Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life, Citation2009, pp. 39–41). To what extent do members of these societies – where Shi‘a represent a tiny, uninfluential minority – hold sectarian prejudices? What, moreover, are the underlying sources of this prejudice?

We investigate these questions, examining Morocco as a case study. Using an original, nationally-representative survey of 2,000 respondents, we assess the correlates of discriminatory attitudes towards Shi‘a. Little research exists on this topic utilizing original surveys in overwhelmingly Sunni states of the Mediterranean, with the exception of Steven Brooke’s pioneering research (Citation2017, pp. 849, 854–5), which documented considerable prejudice against Egypt’s tiny Shi‘i minority, estimated at less than 1 per cent of citizens. Echoing Brooke’s findings, our survey finds widespread discriminatory attitudes towards Morocco’s Shi‘a. Indeed, about 59 per cent of citizens express interpersonal prejudice against Moroccan Shi‘a, expressing discomfort with having one as a neighbour. Such individual-level bias against Moroccan Shi‘a from their fellow countrymen and –women is unexpected and counter-intuitive, given that this sectarian group constitutes an infinitesimal, uninfluential minority of less than .1 per cent of the total population.

We articulate and test three hypotheses that potentially explain the sources of prejudice against Shi‘a: socio-economic marginalization, religious beliefs and practices, and views about regional politics. The first two are derived from existing literature, while the third is our original theoretical contribution. Previewing the core survey results, this study finds that variation in Moroccans’ beliefs about Iran’s status in regional international relations and about the seriousness of the threat it poses, both ideologically and strategically, affect their levels of interpersonal prejudice towards fellow Moroccans adhering to Shi’ism. Respondents’ social marginalization – especially poverty and low educational attainment – also seems to correlate with anti-Shi‘a attitudes, but their religiosity does not seem to matter much.

Our findings advance research on religious diversity in the MENA because they demonstrate that international politics can trickle down into interpersonal relations to hinder the acceptance and tolerance of sectarian minorities. Our research thus illustrates the value of studying the region’s international and security affairs using the tools of survey research. It also underscores the need for research on questions of conflict and security in the region to continue to explore the interconnections between international and domestic politics. Disciplinary boundaries might appear to detach the study of domestic politics from the study of international relations in the MENA. Yet ‘outside-in’ as well as ‘inside-out’ dynamics are manifest across multiple questions, including the impact of global markets – particularly for oil and labour – on countries’ political institutions (Chaudhry, Citation1997; Cammett et al., Citation2015), foreign aid and autocratic survival (Brownlee, Citation2012; Yom, Citation2016), democratization (Jamal, Citation2012), democracy promotion (Bush, Citation2015), ruling parties’ production of legitimacy via foreign policy (Bank & Karadag, Citation2013), and the influence of international norms on political polarization and opposition to democracy (Zarakol, Citation2013). The ‘second image reversed’ school, which highlights the ‘international sources of domestic politics’ (Gourevitch, Citation1978), clearly maintains its relevance for the study of the MENA.

Our findings also carry an important implication for literature on the sectarianization of politics and sectarianism in polarized societies. Existing studies suggest that sectarianization in divided societies is often a constructed, inter-subjectively determined phenomenon, which stems from foreign powers exacerbating the influence of sectarian polarization on domestic politics in pursuit of their own national interests (Fawaz, Citation1995; Makdisi, Citation2000; Khalaf, Citation2002; Robson, Citation2011; Ismael & Ismael, Citation2015; Heydemann & Chace-Donahue, Citation2018; Valbjørn, Citation2019; Dodge, Citation2020; Haddad, Citation2020b; Hinnebusch, Citation2020). But if the presence of sectarian divisions in international relations cultivates popular prejudice not only in the region’s divided societies, but also in its homogeneous ones, then it may be even more challenging to mitigate than previously supposed. In other words, although scholars may assume that regional powers pursue their own interests by stoking anti-Shi‘i prejudice in divided sectarian societies, like Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq, evidence of its pervasiveness in homogenous ones, like Morocco, indicates that it may be a much more difficult phenomenon to overcome than hitherto presumed.

Sectarianism, inter-group relations, prejudice, and international politics

Starting from the premise that a struggle between rival Muslim sects for political power was an essentially omnipresent and inevitable fact of history, Vali Nasr (Citation2006, Citation2016) predicted that the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, by up-ending existing power relations between Sunni and Shi‘a in the MENA, would initiate a new phase of intensified sectarian conflict in the region. One principal dimension to the increasing salience of sectarian identityFootnote4 in regional politics was concern on the part of Sunni-led governments that ruled over Shi‘i populations (whether minorities, as in the case of Saudi Arabia, or majorities, as in the case of Bahrain) that the turn of events in Iraq could ‘embolden’ these populations to seize power (see, e.g., Byman, Citation2014, pp. 80–1). In other words, the survival of some of the region’s non-democratic regimes could be threatened. This was also possible through the strategic interference of regional powers in each other’s internal affairs, even if using the instruments of ‘soft power’, as in the competition between Iran and Saudi Arabia (Mabon, Citation2013). Whereas Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and their allies sought to stoke anti-Shi‘a sentiments among Sunni populations of neighbouring states, Iran simultaneously strove to encourage anti-Sunni attitudes among Shi‘i populations. These fears manifested particularly in Iraq, where a Sunni-led regime had been replaced by a Shi‘i-led one. This led the region’s status quo powers, all U.S. allies, to view Iran as a greater threat, with the possibility that now, aided by pan-Shi‘i solidarity, it could put together a larger revisionist bloc to oppose them.

The increasing salience of sectarian identity within and between states in the region therefore rested on Sunni governments’ perception of Shi‘i populations as potentially disloyal and of Iran as their principal international rival, which then reinforced their suspicions of Shi‘i populations serving as a potential ‘fifth column’ for Iran (Nasr, Citation2004, p. 19). In 2006, Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak summed up these two elements of the issue: ‘Definitely Iran has influence on Shias. Shias are 65% of the Iraqis … . Most of the Shias are loyal to Iran, and not to the countries they are living in’ (Al-Jazeera, Citation2006).

Recent literature on sectarianism and sectarianization (e.g., Haddad, Citation2020b; Hashemi & Postel, Citation2017; Zabad, Citation2017, p. 135-139; Mabon, Citation2013, Citation2020) shows how it is elite-driven. This literature emphasizes that elites have incentives to mobilize sectarian identity cleavages, particularly to secure their own political survival in the face of domestic opposition or electoral competition, and that regional inter-state competition and competition between transnational actors facilitate such mobilization.Footnote5 Scholars explain increasing tension between sects, or the risk thereof, as the result of political elites’ strategic choices, whether on policies or the deployment of securitizing language around sectarian identity (Lust, Citation2007; Gengler, Citation2013; Calculli & Legrenzi, Citation2016; Lord, Citation2019; Dodge & Mansour, Citation2020). In addition, the discourse of religious elites, presumably in service of political leaders’ goals, is thought to feed tensions when it emphasizes sectarian difference and denigrates the out-group (Darwich & Fakhoury, Citation2016).

The existing literature, moreover, mainly examines countries where sectarian affiliation is an issue, namely those countries with sizable Shi‘i minorities. The upshot is a focus on a kind of instrumental logic to sectarianism: sectarian identity is likely to become more salient in countries in which institutions and demography incentivize political organizing along sectarian lines, whether as a divide-and-rule strategy by autocratic rulers (e.g., Lust, Citation2007; Freer, Citation2019; Hinnebusch, Citation2020) or as a vote-getting strategy by competitors within a sect (Cammett, Citation2014, Corstange, Citation2016). In both situations, elites instrumentally create narratives about Shi‘i populations to help realize their interests.

Yet, how ordinary people in their everyday lives react to (or are likely to react to) elites’ instrumental attempts to activate sectarian identification is an under-studied area. It is also clear that the elite-driven perspective is but one part of the picture. Individuals’ identification may also occur independently of elites, or develop in complex interaction with it. For example, an alternative approach considers individuals’ responses to international events, focusing on how speech and images of such events proliferated via traditional and social media can mobilize and activate sectarian identities. Violent events in the news appear to make individuals more willing to endorse or reproduce language derogating members of another sect (Siegel, Citation2017). And, importantly, when the discourse of religious elites appearing in the media or social media emphasizes shared identity across sects, there is evidence that individuals become less willing to endorse or to reproduce language derogating members of another sect (Siegel & Badaan, Citation2020). Like the other literature reviewed above, these findings are largely based on evidence from countries with a substantial Shi‘i minority population. Moreover, it should be noted that, although sectarian mobilization via the instrumental actions of elites or via the independent reactions of individuals to events represent different schools of thought, nothing in either approach suggests that they are intrinsically mutually exclusive. Indeed, individual sectarian identification can be simultaneously activated both by elite cues and also international events viewed in the media.

At an individual level, then, why might someone already hold prejudice against Shi‘a or buy into elite anti-Shi‘i narratives, either developing new prejudice towards the Shi‘a or intensifying an already-held prejudice? The literatures on prejudice and inter-group conflict are vast (reviews include Hewstone et al., Citation2002; Green & Seher, Citation2003). We find two important categories of potential explanations within them, which we use to generate hypotheses.

First, scholars link prejudice to the deleterious psychological consequences of socio-economic marginalization. Genevieve Knupfer calls attention to the ‘psychological underprivilege’ that economic deprivation creates, which creates low self-esteem (Knupfer, Citation1947, p. 114). In his study of ethnic conflict, Donald Horowitz highlights ‘relationships among self-esteem, anxiety, and prejudice’. He explains, ‘Prejudice allows a discharge of hostility, thereby reducing anxiety. A correlation has also been found between lack of individual self-esteem and degree of hostility toward outgroups, and the same relationship should hold for group esteem’ (Horowitz, Citation2000, p. 179).Footnote6 A complementary behavioural perspective on marginalization sees the life experiences of the poor as generating fertile ground for prejudice. Seymour Martin Lipset explains that the poor are ‘more likely to have been exposed to punishment, lack of love, and a general atmosphere of tension and aggression since early childhood, experiences which often produce deep-rooted hostilities’ that can manifest in prejudice (Lipset, Citation1959, p. 495). These arguments find contemporary expression in accounts of ‘the politics of resentment’ (Cramer, Citation2016) and ‘identity politics’ (Fukuyama, Citation2018), in which the marginalized, the ‘invisible’, turn to prejudice as a way of allaying their status anxiety.Footnote7 Another way to describe this dynamic, as Kuziemko et al. (Citation2014) explain, is ‘last-place aversion’, whereby the marginalized use prejudice to identify and place certain social groups as lower than themselves on society’s totem pole.

Second, the strength of religious belief, degree of religious observance, and belief in religion being an important part of politics could be associated with prejudice towards members of religious out-groups. Prejudice might constitute an organizational tool to strengthen in-group bonds and identification by derogating the out-group (see Kalin & Sambanis, Citation2018). Prejudice might result from beliefs that categorize an out-group as a threat to in-group values (Ysseldyk et al., Citation2010). In-group members might even fear the out-group as an epistemological challenge to in-group beliefs and therefore direct prejudice towards it (Brandt & Reyna, Citation2010). Since there is ample evidence to suggest that religious belief can also reduce prejudice, it is therefore the content of individuals’ beliefs and the social and political setting that are likely to shape the direction of the effect of religion (Burch-Brown & Baker, Citation2016). Religiosity might therefore catalyse prejudice if it coincides with status anxiety or economic interests. In this vein, Fukuyama describes how ‘the religious partisan’ scapegoats members of a religious out-group. The religious partisan, Fukuyama explains, convinces co-religionists using the following logic: ‘You are a member of a great community of believers who have been traduced by non-believers; this betrayal has led not just to your impoverishment, but is a crime against God himself. You may be invisible to your fellow citizens, but you are not invisible to God’ (Fukuyama, Citation2018, p. 89). This type of scapegoating should be more commonplace and more vicious the more an individual believes that religion is an important part of politics (see also Ghobadzdeh & Akbarzadeh, Citation2015). Evidencing this point, Hoffman and Nugent (Citation2017) find that individuals’ participation in communal religious observance in Lebanon increases their support for the militarization of political parties at the individual level, but only within groups that already have an armed political party, while for those that do not, the effect is to decrease support for militarization.

Based on these two main categories in the literature, we hypothesize that:

H1: The higher an individual’s level of socio-economic marginalization, the greater the likelihood that s/he will express opposition to Shi‘i individuals.

H2a: The more religiously observant an individual, the more likely s/he will be to express opposition to Shi‘i individuals.

H2b: The more an individual supports Islamist parties, the more likely s/he will be to express opposition to Shi‘i individuals.

Since these hypotheses are based on observable implications of mechanisms of individuals’ psychology within the context of relationships in a multi-group society (H1) and inter-group relations (H2), we do not expect to find much, if any support for them from our Morocco-based survey. Indeed, Morocco’s Shi‘a constitute far too small a part of its society for the mechanisms to work as theorized.

We argue, however, that Iran’s activities in regional international relations are likely to play an important role in shaping how Sunni Moroccans view the Shi‘a. Not only do the activities of states in the international arena influence domestic structures and politics at home, but they can have trickle down effects on inter-ethnic (inter-sectarian) relations among individual citizens. Individuals, at a basic level, may see domestic Shi‘i populations as sympathizers of Iran and Iranian foreign policy. The more individuals oppose the ideology or foreign policy plans of the Iranian government, the more likely it is that they will express some prejudice towards Shi‘a, even though Morocco’s Shi‘i population has long-standing historical origins that precede the Iranian revolution. In particular, we expect two issues to be salient: the Iranian nuclear program as a threatening, security-related concern; and Khomeinism as a threatening ideology – either as a generalized threat to Sunni Islam, or as a specific threat to monarchies of the MENA. Therefore, we formulate a third hypothesis, for which we expect to find greater support from our Morocco-based survey than either H1 or H2:

H3. Sunni Moroccans who oppose the international actions of the Iranian government are more likely to express opposition to Shi‘i individuals than Sunni Moroccans who do not oppose the international actions of the Iranian government.

Case selection and background: A short history of Morocco’s Shi‘a and anti-Shi‘i bias

Morocco provides an ideal case in which to examine popular prejudice towards Shi‘a when they constitute an infinitesimal, uninfluential minority. Morocco’s Shi‘i population, though it constitutes only a small sectarian minority, has historical roots going back centuries. In other words, the community long predates the Iranian revolution and the Iranian regime’s efforts to expand its influence regionally. We should not presume, a priori, that respondents perceive fellow Moroccans who are Shi‘i simply as puppets of the Iranian government or a fifth column. Rather Moroccan Shi‘a have had a genuine role in Morocco’s historical and religious development. Thus, any of the three theories presented above could be viable explanations predicting higher levels of prejudice against Morocco’s Shi‘a, yet we need to conduct a survey in order to determine which one is borne out.

Generally, research on Morocco’s Shi‘i community is limited. Indeed, as Zweiri and König describe, this dearth of research derives from an almost ‘complete neglect of Shiite communities and culture in Morocco’, itself the result of the ‘lack of precise historical analysis of the developments that have led to the spread of Shiite Islam in the Maghreb’ (Zweiri & König, Citation2008, p. 518). Shi‘ism began to spread in Morocco in 788 AD after the arrival of Idris ibn ‘Abd Allah in 786, following previous waves of Ummayad and Abbasid control over Morocco. Idris, who hailed from the Arabian peninsula, fled to Egypt and then Morocco escaping persecution of the Abbasids after the failed uprising at Fakhkh, in which the descendants of Prophet Mohammed through his cousin and son-in-law Ali ibn ‘Abi Talib revolted seeking to gain political control over the Islamic caliphate. Upon arriving in Morocco, as Zweiri and König explain, Idris ‘won the support of dissident Berber tribes who embraced him as their Imam and mostly converted to Shiite Islam’ (518). The Idrisid dynasty, initially based in what is now Meknes province, expanded throughout northern Morocco and established the country’s first monarchical Islamic dynasty. The dynasty built a new capital by establishing the medieval city of Fez, which became a centre of Islamic learning and scholarship with the founding of numerous mosques and also al-Qarawiyyin University (which some claim is the world’s longest continually operating Islamic university). The Idrisid rulers expanded their influence and spread Shi‘i Islam throughout Morocco via conquest until 985, when proxies of the Sunni Umayyad Caliphate ousted them. Under Umayyad influence, Shi‘ism’s proliferation ceased and nearly all Moroccan Muslims became Sunnis, a trend in conversion which intensified under later Sunni dynasties. Even though few Moroccans today follow Shi‘ism, they continue to revere the Idrisid dynasty as the country’s first Islamic kingdom. Indeed, Idris ibn ‘Abd Allah’s mausoleum remains one of the country’s most important pilgrimage sites.

A very small number of Moroccans, approximately 2,000 to 8,000 individuals in total, adhere to Shi‘ism. Nearly all follow Twelver Ja‘fari Shi‘ism (Geunfoudi, Citation2019). These include both indigenous Moroccan Shi‘a, and also Moroccans who converted to Shi‘i Islam while working abroad, especially in Belgium (Lechkar, Citation2017a, p. 244). Today, about 8,000 to 10,000 Moroccans living in Belgium and Belgians of Moroccan descent likely ascribe to Shi‘ism, and acquired it through interaction with Iraqi and Iranian Imams based in Belgium and Europe in the 1970s and 1980s (Lechkar, Citation2017a, p. 245, Citation2017b). Some evidence also suggests that small numbers of Moroccan religious students drawn towards Shi‘ism studied at Shi‘i mosques in Iran, Syria, and Lebanon (Kenyon, Citation2009). Many of these individuals are connected with Belgian-based Moroccan Imam el-Ouerdassi, who converted to Shiism in 2009. More generally, factors like the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, Hezbollah’s success in driving Israel from south Lebanon in 2000, and the popularity of Shi‘i television stations – al-Manar and al-Kawthar – have motivated some Moroccans to adopt Shi‘ism (Lechkar, Citation2012, p. 12).

Morocco’s Shi‘i minority lives almost entirely in the country’s northern provinces, where the Idrisid dynasty was concentrated. The chronology of anti-Shi‘i prejudice in Morocco begins after the Iranian revolution. Although Iran’s Shah eventually gained asylum in Egypt, his first country of choice for exile was Morocco, where he arrived with his entourage in Marrakech in January 1979 as the Iranian revolution crescendoed. But the Shah was not a good houseguest. His penchant for ‘publicly drinking champagne’ and permitting his wife to ‘visit mosques in revealing clothing’ provoked such large protests that Morocco’s erstwhile king, Hassan II, had to ask him to leave (Pennel, Citation2000, p. 362). Thereafter, Hassan II began to develop concerns about Morocco’s Shi‘a, believing, as Jennifer Roberson details, that the ‘Iranian revolution demonstrated the danger of appearing to neglect religion as well as the real possibility that a monarch could be overthrown’ (Citation2014, p. 74). Indeed following the bloody 1984 riots in Morocco’s northern provinces, the regime initially placed blame on the country’s Shi‘a. In a live television broadcast, Hassan II blamed ‘Khomeinists’ for the riots and showed viewers ‘tracts bearing the portraits of the Ayatollah he said were seized on ringleaders’ (Hughes, Citation2001, p. 290). The 1984 riots were ultimately attributed to socio-economic angst, unrelated to Morocco’s Shi‘a. And while most Moroccan Islamists opposed Khomeinism during the 1980s, the regime expressed concerns about ‘a minority that did express fascination for the Iranian revolution’ (Benomar, Citation1988, p. 554).

In the 1990s and 2000s, the regime engaged in moderate levels of repression against Morocco’s Shi‘a. In the 1990s, several Shi‘i activists tried to formally establish religious organizations in Meknes and were subsequently arrested, though they were quickly released (Ablal, Citation2018). In 2009, about 300 Moroccans in Tangier and other northern provinces were detained and questioned for suspected Shi‘i sympathies (Kenyon, Citation2009). Such repressive actions have tended to follow diplomatic spats between Morocco and Iran, as in 2009 and 2018, when the Moroccan government broke off diplomatic relations with Iran (Fernández-Molina, Citation2016, p. 73). In the first instance, in 2009, Morocco alleged that Iran had engaged in Shi‘i proselytization within its borders. In the second instance, in 2018, Morocco accused Iranian-backed Hezbollah of providing weapons and urban warfare training to POLISARIO. The occurred in the context of escalating military tensions between Iran and Morocco, since the latter had sent 1,500 troops to fight against Iranian-allied militants in Yemen (Oxford Analytica, Citation2018).

Today, several small Shi‘i religious associations exist informally, the most influential among them run by Kamal al-Ghazali and Isam Hmaidan in Tangier (Geunfoudi, Citation2019). After several unsuccessful attempts to obtain permits for their association to operate as a civil society organization between 2012 and 2014, they eventually gained a commercial permit to operate as a legal publishing house. In effect, Morocco’s commercial court granted them a permit to function as a publishing house for Shi‘i religious books and other publications in 2015, which they named the Foundation of the Missionary Line for Studies and Publishing (Mu’asasat al-Khat al-Risālī li-l-Dirāsāt wa-l-Nashar). Although the Moroccan Shi‘i community generally seeks to avoid public attention, and thus stays out of domestic politics, it did speak out – alongside other Moroccan religious minorities, such as Christians and Baha’i – to advocate for greater religious tolerance and acceptance after Morocco’s new constitution was enacted in 2011, which they claim permits a greater level of personal religious freedom of belief (Geunfoudi, Citation2019). Yet emphasizing their disinterest in politics does not let Morocco’s Shi‘a fully escape repression, and one of its leaders – Abdou El Chakrani – was sentenced to one year in prison for ‘alleged financial improprieties’ in 2016. His supporters claim, by contrast, that he was ‘targeted for his religious beliefs’ and ties ‘with known Shia leaders’ (U.S. Department of State, Citation2017, p. 6).

Generally speaking, Morocco’s regime likely views its Shi‘i citizens as a potential domestic political threat. They may be less likely to accept the king’s divine right to rule over the citizenry as Commander of the Faithful (Amīr al-Mu’minīn), the cornerstone of the regime’s claim to legitimate rule (Waterbury, Citation1970; Hammoudi, Citation1997). More broadly, the regime may see them as ‘endangering the Sunnite identity of the country’ (Maréchal & Zemni, Citation2012, p. 230). Indeed, as Driss Maghraoui writes, the existence of Shi‘ism has been perceived as a threat to the regime’s capacity to sustain a ‘Moroccan moral order’ based on its control of official Sunni Islam (Citation2009, p. 197). In part, this explains why legal Islamist movements – such as the Justice and Development Party (PJD) and smaller Salafist groups – that recognize the king’s religious leadership have issued public statements and declarations to sensitize the public to the ‘sectarian Shi’ite invasion’ in Morocco (Laurence, Citation2017). The regime has also moved to promote this anti-Shi‘i discourse, using state television stations like 2M, Al Maghribia, and Al Aoula.

Empirical analysis

To assess the ability of the three hypotheses to explain why Sunni citizens express prejudice towards fellow citizens who are Shi‘i, even when the Shi‘a are a minute and uninfluential minority nationally, this study draws upon a survey conducted in Morocco in 2016. The authors collaborated with a Moroccan public opinion polling firm to organize and implement the survey of 2,000 respondents, which utilized randomized multi-stage sampling methods at all levels of sampling. The Online Appendix furnishes more information on survey sampling procedures and how one author oversaw the survey’s implementation during fieldwork in Morocco. Led by a Moroccan academic, the polling firm has extensive experience, implementing over 30 pervious nationally representative surveys in Morocco since its establishment over a decade ago. It is the main partner of most international survey initiatives working in Morocco, having completed four earlier survey waves on behalf of the Afrobarometer and three waves for the Arab Barometer. It has also done surveys for the World Bank, various foreign embassies (EU, French, U.S.), and also the Moroccan government’s Royal Institute for Strategic Studies.

Results from our survey allow us to determine which factors correlate robustly with Sunni Moroccans’ expressed opposition to Shi‘a. To preview the results, we find the most support for Hypotheses 1 and 3, concerning socio-economic marginalization and views about Iran. We do not find support for Hypothesis 2 regarding religiosity. In particular, variables derived from Hypothesis 3, regarding how much citizens perceive Iran to be both an ideological and strategic threat in regional international relations seem to shape variation in levels of their interpersonal prejudice towards Morocco’s domestic Shi‘i population.

Dependent variables

We analyse variation in respondents’ answers to questions regarding support or opposition to a family moving in next-door. The study includes three different dependent variables – a baseline outcome, the study’s main dependent variable, and a second dependent variable (included for comparative purposes). At each respondent’s doorstep, the survey enumerator began by reading the following prompt to the respondent: ‘Now, I am going to ask you about some things that sometimes bother some Moroccans. Tell me, would you oppose strongly, oppose, support, or support strongly the following family moving in next door?’ Then, the enumerator recounted three separate questions that were listed in the following order: First, as a baseline, the enumerator asked ‘A Sunni Family from Morocco’. Second, for our main dependent variable, the enumerator asked: ‘A Shi‘i Family from Morocco’. Finally, for comparative purposes, the enumerator asked: ‘A Shi‘i Family from Iran’. The response rate for these three dependent variable questions ranged from 94 per cent to 98 per cent each.Footnote8

The enumerator asked respondents to rank support or opposition to each type of neighbour on a four-point Likert scale when answering the question: strong opposition, opposition, support, or strong support. We coded a binary dependent variable from the responses to each question. For example, the main dependent variable, opposition to Moroccan Shi‘a, takes the value of 1 if a respondent expresses at least some opposition (strong opposition or opposition), and zero otherwise. Using this measure, about 59 per cent of Moroccans expressed prejudice against Moroccan Shi‘a. The two other dependent variables were coded similarly as binary outcomes, with respondents expressing at least some opposition (strong opposition or opposition) to either a Moroccan Sunni family or an Iranian Shi‘i family, respectively, taking the value of 1 (all other responses coded zero). As displayed in , these two dependent variables are labelled opposition to Moroccan Sunni(baseline) and opposition to Iranian Shi‘a.

Table 1. Moroccans’ anti-Shi‘i attitudes.

Independent variables

We use a series of independent variables to assess the hypotheses about the sources of anti-Shi‘i prejudice. Explanations of how each variable was coded are contained in the Online Appendix. For Hypothesis 1, on socio-economic marginalization, variables were generated recording a survey respondents’ level of economic insecurity (poverty) and also their level of education (low education at primary school or below). Hypothesis 2 – concerning religion and religious issues – utilizes several several questions from the survey that track respondents’ level of religiosity and their support for Islamist parties and social movements. Mimicking a question the Arab Barometer uses to measure respondents’ religiosity, we use a question about self-reported observance of the fajr prayer (which occurs around 4:00 AM). More religious Muslims tend to practice the fajr prayer on time, whereas less religious ones do it later in the morning or skip it altogether. Respondents who report doing the fajr prayer on time were coded as more religious. Hypothesis 3 is our hypothesis of interest. For it, concerning views about Iran, the survey included several questions to create independent variables to record respondents’ opposition to Iran’s main ideological framework (the political philosophy of the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, known as Khomeinism), beliefs that Iran has a military nuclear program for producing nuclear weapons, and general support for closer Iranian-Moroccan relations in international politics.

Several control variables were also incorporated. These variables do not derive from the above theories but could potentially still influence Moroccans’ levels of interpersonal prejudice against Shi‘a. In particular, control variables include tracking respondents’ levels of pro-Westernism and nationalism, respectively, and also the degree to which they follow the international news (i.e., how well aware are individuals of current events outside of Morocco). Since both Western states and Morocco’s regime oppose Iran in regional international relations, it is expected that those citizens who align more closely with Western states or with Morocco’s regime would express greater opposition to both domestic and foreign Shi‘i populations. These oppositional attitudes, however, may come simply from greater loyalty or affinity for Western states or Morocco’s regime and not, necessarily, particular bias or prejudice against Shi‘i populations. We also added a control variable documenting the degree to which the respondent believes that the Iranian government’s proselytization is a problem locally, which is an accusation often levied by Morocco’s regime against Iran in the media. Two separate tests demonstrated that the aforementioned independent variables do not suffer from multicollinearity. Maximum values on the variable inflation factor (VIF) tests fell below 2.0, which do not exceed the standard threshold of 5.0.Footnote9 The remainder of this section first surveys preliminary results in a baseline test. Subsequently, it presents the correlates of greater opposition to Moroccan Shi‘a and, finally, it compares the sources of prejudice against Moroccan Shi‘a with those of foreign (Iranian) Shi‘a.

Analysis and results

We estimate three logistic regression models. We begin by conducting a baseline analysis (see , Model 1). We identify variables correlated with opposition to neighbours, generally speaking, before examining which variables correlate with opposition to Moroccan Shi‘i neighbours. Certain individual characteristics of respondents may be related to dislike for all types of new neighbours, regardless of these neighbours’ sectarian affiliations. The baseline analysis helps us to separate variables that encourage opposition to all categories of neighbours from those that uniquely drive prejudice against Moroccan Shi‘a. In effect, the baseline helps to show that some respondents’ opposition to having a Moroccan Shi‘i neighbour does not derive specifically from active prejudice against Moroccan Shi‘a, but rather is part and parcel of these individuals’ opposition to all types of new neighbours.

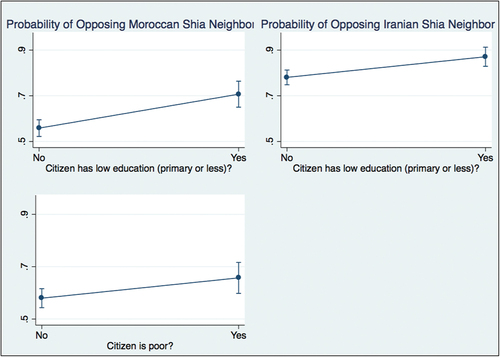

For the baseline analysis, we use the first dependent variable question on the survey, which asked about a Sunni Moroccan family moving in next door. Results (see , Model 1) confirm that, indeed, several variables are statistically significantly correlated with opposition to new neighbours, regardless of those neighbours’ sectarian affiliation. These findings are especially pertinent to the first and second hypotheses. Concerning Hypothesis 1, marginalized respondents are more likely to express anti-new neighbour attitudes. This was particularly true of respondents with lower education. Respondents with only a primary or lower level of education had about a .12 predicted probability of expressing opposition to having new Sunni Moroccan neighbours, but this dropped to .06 predicted probability for citizens with higher education levels. One potential explanation is that citizens who are marginalized due to lower education levels – who likely live more stressful lives with less knowledge, a narrower worldview, and likely greater material precarity – express negative attitudes towards all types of new neighbours, not only and exclusively Moroccan Shi‘a. Perhaps, they surmise that new neighbours drive up housing costs and the cost of living generally within the area; new neighbours presage gentrification. Since the late 1990s, after considerable neoliberal reforms and real estate redevelopment projects (like Rabat’s Bouregreg Valley), rent and the cost of living have increased dramatically for many Moroccans (Bogaert, Citation2018, pp. 16–24; Catusse, Citation2008; Cammett, Citation2007). Concerning Hypothesis 3, the results indicate that individuals who voice desire for friendlier relations with Iran also hold more welcoming attitudes towards having new neighbours, regardless of those neighbours’ sectarian affiliation. Specifically, respondents who opposed closer diplomatic relations with Iran had a .09 predicted probability of opposing new Moroccan Sunni neighbours, while this predicted probability dropped to .06 for those who supported closer Iranian-Moroccan relations.

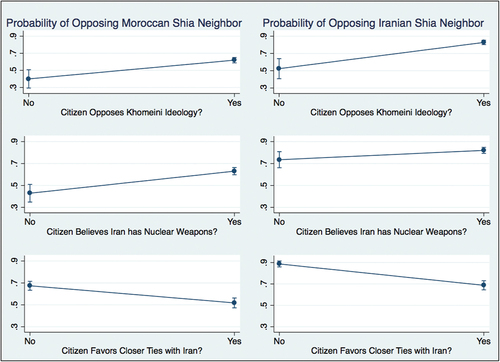

Next, we estimate models of opposition to new Shi‘i neighbours. Respondents expressed far greater opposition to having a new Moroccan Shi‘i neighbour (at about 59 per cent) than the baseline of a new Moroccan Sunni neighbour (about 7 per cent).Footnote10 (Model 2) presents the results for the dependent variable opposition to Moroccan Shi‘a. Consistent with the Hypothesis 3, respondents who oppose Iran’s Khomeini-inspired ideology and also believe it has a nuclear program for military purposes are more likely to express discriminatory attitudes than respondents who do not oppose Iranian ideology or respondents who do not believe the Iranian nuclear program has a military purpose. In addition, citizens who favour closer diplomatic ties with Iran exhibit also seem to exhibit less discriminatory attitudes. The findings are summarized in . Moroccans who express disagreement with Khomeinism had a .62 predicted probability expressing opposition to having a Moroccan Shi‘i neighbour, whereas those who did not disagree with it had a .40 predicted probability of expressing opposition (Left column, top graph). Similarly, respondents who affirmed a belief that Iran has an active nuclear program for producing nuclear weapons had a higher likelihood of expressing opposition to having Moroccan Shi‘i neighbours (.64 predicted probability) compared with those citizens who denied that Iran has a military nuclear program (.43 predicted probability) (Left column, centre graph).

These results support this study’s main original theory (Hypothesis 3): that Moroccans’ prejudice towards fellow Moroccans who happen to be Shi‘i is driven by the extent to which they perceive Iran as an ideological and strategic threat in regional international relations. Indeed, the variables connected closely to respondents’ perceptions of Iran’s status as an ideological and strategic threat – their beliefs about the dangers of Khomeinism and the presence of an Iranian nuclear weapons program – were not statistically significantly correlated with discrimination against Moroccan Sunni in the baseline analysis. This suggests that these variables help to explain why Moroccans hold discriminatory attitudes towards fellow countrymen and -women who are Shi‘i, and that the prejudice identified here is less likely to be derived from unrelated socio-economic attributes of respondents.

An additional result that is consistent with the above is that respondents who desire closer diplomatic relations with Iran expressed lower levels of opposition to having Moroccan Shi‘i neighbours (.56) when compared with respondents who did not desire closer diplomatic relations with Iran (.68 predicted probability). Yet, as the baseline analysis indicated, respondents who generally favoured warmer relations with all new neighbours, regardless of neighbours’ sectarian affiliation, also tended to favour closer relations with Iran. Thus, at its core, the negative correlation between support for closer diplomatic ties with Iran and prejudice towards Moroccan Shi‘a could stem from respondents’ tendency to favour peaceful and non-confrontational relations with ‘out-groups’, rather than a specific understanding of Iran’s role within the international relations of the MENA. We also find evidence for Hypothesis 1: Respondents who face greater marginalization – lower income and education – tend to express more discriminatory attitudes towards Moroccan Shi‘a. summarizes these results. Respondents who reported facing major or minor financial difficulties were more likely to oppose having a Moroccan Shi‘i neighbour (.66 predicted probability), than were wealthier respondents – those who reported few or no financial difficulties (.58 predicted probability) (see left column, bottom graph). Lower levels of education also correlated with greater discrimination against Moroccan Shi‘a. Respondents who reported having completed only primary school or below had a .71 predicted probability of expressing opposition to having a Moroccan Shi‘i neighbour, whereas those with more than a primary school education were less likely to voice opposition, at .56 predicted probability (Left column, top graph). Regarding religiosity, neither respondents’ level of observance nor support for Sunni Islamist parties and movements was correlated with prejudice against having a Moroccan Shi‘i neighbour. In short, the statistical effect of religiosity was null, disconfirming the predictions of Hypothesis 2.

As was the case of respondents who favoured closer Iranian-Moroccan relations, the baseline analysis indicated that lower education was correlated with more negative attitudes towards all new neighbours, without respect to neighbours’ sectarian affiliation. The positive correlation between low education and opposition to Moroccan Shi‘a might therefore be a byproduct of respondents’ underlying characteristics, rather than one uniquely attributable to their opposition specifically to Moroccan Shi‘a.

Next, we compare our main dependent variable, opposition to Moroccan Shi‘a, with the third dependent variable, opposition to Iranian Shi‘a, to gauge how the degree and sources of respondents’ discriminatory attitudes towards Shi‘a differ, contingent on whether the Shi‘i population is domestic or foreign. In other words, this analysis allows us to assess whether respondents’ prejudice changes in extent, intensity, and correlates, with the nationality of the new Shi‘i neighbour.

Although few Iranians live in Morocco, it is possible – hypothetically speaking – that an Iranian family could move in next door to a Moroccan family. Such neighbours could be an expatriate family working in commerce, diplomacy, or for an international organization, or be members of the Iranian diaspora produced by the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Morocco’s King Mohammed VI, for example, recently granted citizenship to a longtime Casablanca-based Iranian businessman, Muhammad Reza Nouri Esfandiari, who runs a brokerage firm facilitating overseas foreign direct investment in Morocco and West Africa.

The results show a clear difference in levels of prejudice towards Iranian Shi‘a compared with Moroccan Shi‘a, with far greater opposition to the former than the latter. Indeed, while nearly 59 per cent of respondents opposed having Moroccan Shi‘a as neighbours, this figure ballooned to almost 78 per cent for Iranian Shi‘a.Footnote11 Thus, although Moroccans generally express discriminatory views towards all Shi‘a, they deem Iranian Shi‘a far worse than Moroccan Shi‘a.

The greater level of opposition to Iranian versus Moroccan Shi‘a aside, the underlying drivers of prejudice appear similar. Variables correlated with respondents’ opposition to Iranian Shi‘a (, Model 3) were similar to those correlated with opposition to Moroccan Shi‘a. Variables showing support for both Hypothesis 1 and Hypothesis 3 – social marginalization and respondents’ views about Iran – similarly either increased or depressed opposition to Iranian Shi‘a. Like the results in Model 2, Model 3 shows that citizens who oppose Khomeinism and believe Iran has nuclear weapons are more likely to oppose having an Iranian Shi‘a neighbour (see the top and centre graphs in ’s right-hand column). Finally, like the baseline analysis and Model 2, Model 3 shows that respondents who desired closer diplomatic relations between Morocco and Iran were less likely to oppose having an Iranian Shi‘i neighbour (, bottom graph, right-hand column). Marginalization also mattered – respondents with lower education levels were more likely to oppose having an Iranian Shi‘i neighbour (, top graph, right-hand column).

In sum, comparing the results of Models 2 and 3 shows that nearly all of the variables that raised (or lowered) respondents’ opposition to Moroccan Shi‘a similarly raised (or lowered) their opposition to Iranian Shi‘a.Footnote12 This suggests that respondents discriminated against fellow citizens who were Shi‘i mostly because they feared the ideological and strategic threats that Iran represented to Morocco – the threat of Khomeinism and an Iranian nuclear weapon. Prejudice against Moroccan Shi‘a appears to stem from a concern that they are allies or under the influence of Iran, a link that is underscored by greater prejudice towards Iranian Shi‘a.

It is important to note that the connections we find between perceptions of Iranian ideology and foreign policy and prejudice towards Shi‘a can be explained by both of the two distinct approaches to the activation of sectarian identification reviewed above – instrumental elite-driven and independent individual reactions to events. At the theoretical level, the two need not be mutually exclusive and could operate simultaneously to generate sectarian mobilization. In the case of Morocco, we find some evidence that both approaches are at play. The survey data suggest that international events may indeed play a role, since news consumption is positively correlated with prejudice towards Iranian Shi‘a. At the same time, qualitative evidence, particularly the episode of the 1984 riots discussed in background on Morocco, above, suggests that elite cues are at work.

Conclusion

Drawing on a unique survey from Morocco, this study has found that Moroccans’ perceptions of Iran as an ideological and strategic threat are powerful predictors of variation in levels of prejudice against Moroccan Shi‘a. Respondents’ views about Iran’s role in regional international relations seem to carry over into their perceptions of fellow Moroccan citizens who follow Shi‘ism. Moreover, our results show that the rationale for respondents’ opposition to Moroccan Shi‘a parallels that for their opposition to Iranian Shi‘a. We did find that the extent to which respondents were marginalized – specifically, their poverty level – also correlated with anti-Shi‘i prejudice. But this variable seemed to carry less importance in explaining prejudice against Moroccan Shi‘a than did the variables capturing a respondent’s perceptions of Iran. In sum, how individuals perceive the seriousness of Iran’s threats to their country in international relations helps to predict their interpersonal prejudice against Shi‘i compatriots, even if the latter have no direct or observable ties to Iran.

Additionally, we found, contrary to expectations in the literature, that an individual’s personal religiosity had no effect on enhancing anti-Shii prejudice in Morocco. Some scholars contend that religious belief is an important, and even ‘overlooked’, driver of international politics in the MENA and Muslim countries more generally, compared to other regions (Fox, Citation2001). The findings from our survey stand in contrast to such claims, highlighting the importance of survey-based research on the region’s international relations.

More broadly, survey research’s ability to get at individual attitudes makes it an important tool for studying questions of international relations and security in the MENA. This is especially the case given ‘second image reversed’ connections between the realms of international and domestic politics. Our research demonstrates that it is feasible to study these connections in the MENA, and the importance of continued attention to such dynamics in future research.

An important limitation of this study is methodological. Inter-ethnic or inter-sectarian prejudice can be difficult to measure due to social desirability bias: respondents may not provide fully authentic responses to survey questions when such responses might violate a strong social norm on the topic in question. Previous studies utilized the item count technique to gauge prejudice in order to address this bias, particularly Brooke’s (Citation2017) application to anti-Shi‘i prejudice in Egypt. Our results may therefore understate the true amount of anti-Shi‘i prejudice pervading Moroccan society. Our study therefore underscores the need for future research on the topic, particularly new studies based on original surveys in the MENA. Future studies may be able to yield more precise estimates of prejudice using the item count technique and other methods designed to glean more accurate respondent answers due to potential social desirability bias (see Gingerich et al., Citation2016).

The increasing sectarianization of the international relations of the Middle East and North Africa over the past two decades is likely to continue to exert an influence on state-to-state interactions in the region and when it comes to the domestic politics of the region’s heterogeneous and polarized societies. Our study helps to round out the understanding of the consequences of sectarianization by investigating its effects on interpersonal prejudice in an overwhelmingly Sunni country, Morocco. We find a link between individuals’ perceptions of Iran in international relations and prejudice against Shi‘a, suggesting that the region’s international politics play out in the everyday lives of citizens, even in domestic settings in which we would not expect sectarian politics to matter. Our results raise the possibility of a feedback loop, which future research can investigate. Increasing mass anti-Shi‘i prejudice, itself the product of the international arena, may reinforce or push governments and heads of state to take harder line sectarian positions in international politics.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (22.2 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors thank the peer reviewers, participants in the Faculty Research Workshop at the Department of Political Science, University of Tennessee, and the Mediterranean Politics editors for helpful feedback and assistance. The authors also thank the University of Tennessee’s Howard H. Baker Jr. Center for Public Policy, Institute for Nuclear Security, and Department of Political Science for financial support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2021.1974198

Notes

1. Haddad (Citation2020a) provides a pivotal analysis of the problems of using the term ‘sectarianism’. In what follows, we recognize the term’s loose nature. We continue to use it out of necessity – previous studies that we build upon use it, and so to summarize the literature without imputing meaning to it, we find it preferable to describe it on its own terms. We agree with Haddad’s recommendation that ‘sectarianism’ should be replaced by the term ‘sectarian identity’, which can then be analysed with precision.

2. We also include here research on ethnic conflict and cooperation.

3. Ibrāhīm (Citation1994) is an important exception, examining problems of ethnicity and politics across Arab states. See also Rørbæk (Citation2019), which looks at the relationship between sectarianism and politics in the Middle East and North Africa using data on all countries in the region.

4. For important debates on the term ‘identity’, see Brubaker and Cooper (Citation2000).

5. That these two themes transcend studies’ theoretical orientations underscores the importance of Valbjørn’s (Citation2020) call for studies of sectarianism to move beyond proposing ‘third way[s]’ in putative debates between primordialist and instrumentalist theorization of sectarianism and instead focus on investigating empirical questions via scholars’ diverse theoretical approaches and on developing and refining those approaches further.

6. See also Green and Seher (Citation2003, p. 518), who mention the possibility of ‘displaced aggression during an economic downturn’.

7. Studies finding correlations between poverty or marginalization and prejudice include Wagner and Zick (Citation1995), Coenders and Scheepers (Citation1998), and Greaves et al. (Citation2020), on education; and Quillian (Citation1995), Coenders and Scheepers (Citation1998), and Sniderman et al. (Citation2004), on poverty and unemployment. The findings are complex, including non-linear effects and sometimes effects at the level of the country but not the individual.

8. Our survey included 2,000 respondents, yet the number of valid respondents decreased in the final models given non-response to some independent variable survey question items. Our final sample size of valid respondents (about 1,100 respondents) in the models was similar to that used in three recent Arab Barometer survey waves in Morocco, specifically 2006 (1,277 respondents), 2014 (1,116 respondents) and 2016 (1,200 respondents).

9. VIF tests were as follows: baseline model 1 (1.05 to 1.16), model 2 (1.05 to 1.15), model 3 (1.05 to 1.16). A second test also indicated that correlations among the independent variables were not high, falling between .004 and .26 for each model.

10. A t-test confirmed that these mean differences in responses were statistically significant (p < .001).

11. A t-test confirmed that these mean differences in responses were statistically significant (p < .001).

12. Three small exceptions emerge. First, poverty is not statistically significantly correlated with respondents’ opposition to having an Iranian Shi‘i neighbour, though it was correlated with prejudice against Moroccan Shi‘a. Second, more religious Moroccans were slightly more likely to express opposition to having an Iranian Shi‘i neighbour, but this variable did not affect their views about having Moroccan Shi‘i neighbours. Third, respondents who consumed international news more were more prejudiced against Iranian Shi‘a but not Moroccan Shi‘a.

References

- Abdo, G. (2017). The new sectarianism: The Arab Uprisings and the rebirth of the Shi’a-Sunni divide. Oxford University Press.

- Ablal, A. (2018, November 6). Religious pluralism in Morocco: Between the spontaneous change of belief and the creation of religious minorities. Heinrich Böll Stiftung report. https://lb.boell.org/en/2018/11/06/religious-pluralism-morocco-between-spontaneous-change-belief-and-creation-religious

- Al-Jazeera. (2006, April 10). Mubarak’s Shia remarks stir anger. https://www.aljazeera.com/archive/2006/04/200849132414562804.html

- Asmar, C., Kisirwani, M., & Springborg, R. (1999). Clash of politics or civilizations? Sectarianism among youth in Lebanon. Arab Studies Quarterly, 21(4), 35–64. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41858306

- Avramov, K., & Trad, R. (2018, December 10). Under the radar: Iran’s ‘stealth’ presence on the Balkans. The Globe Post. https://theglobepost.com/2018/12/10/iran-stealth-presence-balkans/

- Bank, A., & Karadag, R. (2013). The ‘Ankara moment’: The politics of Turkey’s regional power in the Middle East, 2007–11. Third World Quarterly, 34(2), 287–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2013.775786

- Bardos, G. N. (2013). Iran in the Balkans: A history and forecast. World Affairs, 175(5), 59–66. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43554740

- Benomar, J. (1988). The monarchy, the Islamist movement, and religious discourse in Morocco. Third World Quarterly, 10(2), 539–555. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436598808420071

- Binder, L. (ed). (1966). Politics in Lebanon. Wiley.

- Bishāra,‘ A. (2018). Al-Ṭā’ifa, al-ṭā’ifiyya, al-ṭawā’if al-mutakhayyala [Sect, sectarianism and imagined sects]. al-Markaz al-Arabī lil-Abḥāth wa-Dirāsat al-Siyāsāt.

- Bogaert, K. (2018). Globalized authoritarianism: Megaprojects, slums, and class relations in urban Morocco. University of Minnesota Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctt21c4tnr

- Brandt, M. J., & Reyna, C. (2010). The role of prejudice and the need for closure in religious fundamentalism. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(5), 715–725. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167210366306

- Brewer, J. D. (1992). Sectarianism and racism, and their parallels and differences. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 15(3), 352–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.1992.9993751

- Brooke, S. (2017). Sectarianism and social conformity: Evidence from Egypt. Political Research Quarterly, 70(4), 848–860. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912917717641

- Brownlee, J. (2012). Democracy prevention: The politics of the US-Egyptian alliance. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139198721

- Brubaker, R., & Cooper, F. (2000). Beyond ‘identity’. Theory and Society, 29(1), 1–47. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007068714468.

- Bos, M. E. W. V. D. (2020). Shiite patterns of post-migration in Europe. Islam and Christian–Muslim Relations, 31(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/09596410.2019.1667712

- Burch-Brown, J., & Baker, W. (2016). Religion and reducing prejudice. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 19(6), 784–807. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430216629566

- Bush, S. S. (2015). The taming of democracy assistance: Why democracy promotion does not confront dictators. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107706934

- Byman, D. (2014). Sectarianism afflicts the new Middle East. Survival, 56(1), 79–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2014.882157

- Calabrese, J. (2020). The Saudi-Iran strategic rivalry: ‘Like fire and dynamite’. In I. Mansour & W. R. Thompson (Eds.), Shocks and rivalries in the Middle East and North Africa (pp. 59–79). Georgetown University Press.

- Calculli, M., & Legrenzi, M. (2016). Middle East security: Conflict and securitization of identities. In L. Fawcett (Ed.), International relations of the Middle East (4th ed., pp. 218–235). Oxford University Press.

- Cammett, M. (2007). Globalization and business politics in Arab North Africa. Cambridge University Press.

- Cammett, M. (2014). Compassionate communalism: Welfare and sectarianism in Lebanon. Cornell University Press.

- Cammett, M., Diwan, I., Richards, A., & Waterbury, J. (2015). A political economy of the Middle East (4th ed.). Westview Press.

- Catusse, M. (2008). Le temps des entrepreneurs? Politique et transformations du capitalisme au Maroc. Maisonneuve & Larose.

- Chaudhry, K. A. (1997). The price of wealth: Economies and institutions in the Middle East. Cornell University Press.

- Coenders, M., & Scheepers, P. (1998). Support for ethnic discrimination in the Netherlands 1979-1993: Effects of period, cohort, and individual characteristics. European Sociological Review, 14(4), 405–422. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.esr.a018247

- Corstange, D. (2016). The price of a vote in the Middle East: Clientelism and communal politics in Lebanon and Yemen. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781316227169

- Cramer, K. J. (2016). The politics of resentment: Rural consciousness in Wisconsin and the rise of Scott Walker. University of Chicago Press.

- Crow, R. E. (1962). Religious sectarianism in the Lebanese political system. Journal of Politics, 24(3), 489–520. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381600015450

- Dam, N. V. (1996). The struggle for power in Syria: Politics and society under Asad and the Ba‘th party (3rd ed.). I.B. Tauris.

- Darwich, M. (2019). Threats and alliances in the Middle East: Saudi and Syrian politics in a turbulent region. Cambridge University Press.

- Darwich, M. (2020). Escalation in failed military interventions: Saudi and Emirati quagmires in Yemen. Global Policy, 11(1), 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12781

- Darwich, M., & Fakhoury, T. (2016). Casting the other as an existential threat: The securitisation of sectarianism in the international relations of the Syria crisis. Global Discourse, 6(4), 712–732. https://doi.org/10.1080/23269995.2016.1259231

- Dodge, T. (2020). Between wataniyya and ta’ifia: Understanding the relationship between state-based nationalism and sectarian identity in the Middle East. Nations and Nationalism, 26(1), 85–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/nana.12580

- Dodge, T., & Mansour, R. (2020). Sectarianization and desectarianization in the struggle for Iraq’s political field. The Review of Faith & International Affairs, 18(1), 58–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/15570274.2020.1729513

- English, R. (2003). Armed struggle: A history of the IRA. Oxford University Press.

- Fakhoury, T. (2019). Power-sharing after the Arab Spring? Insights from Lebanon’s political transition. Nationalism & Ethnic Politics, 25(1), 9–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/13537113.2019.1565173

- Fawaz, L. T. (1995). An occasion for war: Civil conflict in Lebanon and Damascus in 1860. University of California Press.

- Fearon, J. D., & Laitin, D. D. (1996). Explaining interethnic cooperation. American Political Science Review, 90(4), 715–735. https://doi.org/10.2307/2945838

- Fernández-Molina, I. (2016). Moroccan foreign policy under Mohammed VI, 1999-2014. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315757797

- Fox, J. (2001). Religion as an overlooked element of international relations. International Studies Review, 3(3), 53–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/1521-9488.00244

- Freer, C. (2019). The symbiosis of sectarianism, authoritarianism, and rentierism in the Saudi state. Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism, 19(1), 88–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/sena.12287

- Fukuyama, F. (2018). Identity: The demand for dignity and the politics of resentment. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Gause, F. G., III. (2019). ‘Hegemony’ compared: Great Britain and the United States in the Middle East. Security Studies, 28(3), 565–587. https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2019.1604987

- Gengler, J. (2017). The political economy of sectarianism: How Gulf regimes exploit identity politics as a survival strategy. In F. Wehrey (Ed.), Beyond Sunni and Shia: The roots of sectarianism in a changing Middle East (pp. 181–204). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190876050.003.0009

- Gengler, J. J. (2013). Royal factionalism, the Khawalid, and the securitization of ‘the Shī‘a problem’ in Bahrain. Journal of Arabian Studies, 3(1), 53–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/21534764.2013.802944

- Geunfoudi, M. (2019, February 5). Politicization of Moroccan Shiites? Between the state’s repression and the internal schism. Moroccan Institute for Policy Analysis, report. https://mipa.institute/6438

- Ghobadzdeh, N., & Akbarzadeh, S. (2015). Sectarianism and the prevalence of ‘othering’ in Islamic thought. Third World Quarterly, 36(4), 691–704. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2015.1024433

- Ghodsee, K. (2009). Muslim lives in Eastern Europe: Gender, ethnicity, and the transformation of Islam in postsocialist Bulgaria. Princeton University Press.

- Gingerich, D. W., Oliveros, V., Corbacho, A., & Ruiz-Vega, M. (2016). When to protect? Using the crosswise model to integrate protected and direct responses in surveys of sensitive behavior. Political Analysis, 24(2), 132–156. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpv034

- Gourevitch, P. (1978). The second image reversed: The international sources of domestic politics. International Organization, 32(4), 881–912. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002081830003201X

- Greaves, L. M., Rasheed, A., D’Souza, S., Shackleton, N., Oldfield, L. D., Sibley, C. G., Milne, B., & Bulbulia, J. (2020). Comparative study of attitudes to religious groups in New Zealand reveals Muslim-specific prejudice. Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online, 15(2), 260–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/1177083X.2020.1733032

- Green, D. P., & Seher, R. L. (2003). What role does prejudice play in ethnic conflict? Annual Review of Political Science, 6, 509–531. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.6.121901.085642

- Haddad, F. (2011). Sectarianism in Iraq: Antagonistic visions of unity. Oxford University Press.

- Haddad, F. (2020a). Sectarian identity and national identity in the Middle East. Nations and Nationalism, 26(1), 123–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/nana.12578

- Haddad, F. (2020b). Understanding ‘sectarianism’: Sunni-Shi‘a relations in the modern Arab world. Hurst.

- Hafidh, H., & Fibiger, T. (2019). Civic space and sectarianism in the Gulf states: The dynamics of informal civil society in Kuwait and Bahrain beyond state institutions. Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism, 19(1), 109–126. https://doi.org/10.1111/sena.12290

- Hammoudi, A. (1997). Master and disciple: The cultural foundations of Moroccan authoritarianism. University of Chicago Press.

- Hanf, T. (1993). Coexistence in wartime Lebanon: Decline of a state and rise of a nation. Trans. John Richardson. Centre for Lebanese Studies and I.B. Tauris.

- Harding, S., & Libal, K. (2019). War and the public health disaster in Iraq. In C. Lutz & A. Mazzarino (Eds.), War and health: The medical consequences of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan (pp. 111–136). New York University Press.

- Hashemi, N., & Postel, D. (eds). (2017). Sectarianization: Mapping the new politics of the Middle East. Oxford University Press.

- Hewstone, M., Rubin, M., & Willis, H. (2002). Intergroup bias. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 575–604. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135109

- Heydemann, S., & Chace-Donahue, E. (2018). Sovereignty versus sectarianism: Contested norms and the logic of regional conflict in the Greater Levant. In M. Aydin (Ed.), The Levant: Search for a regional order (pp. 16–47). Konrad Adenauer Stiftung.

- Hinnebusch, R. (2020). Identity and state formation in multi‐sectarian societies: Between nationalism and sectarianism in Syria. Nations and Nationalism, 26(1), 138–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/nana.12582

- Hoffman, M. T., & Nugent, E. R. (2017). Communal religious practice and support for armed parties: Evidence from Lebanon. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 61(4), 869–902. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002715590880

- Horowitz, D. L. (2000). Ethnic groups in conflict (2nd ed.). University of California Press.

- Hughes, S. O. (2001). Morocco under King Hassan. Ithaca Press.

- Ibrāhīm, S. al-D. (1994). Al-Milal wa-l-niḥal wa-l-a‘rāq: Humūm al-aqallīyāt fī-l-Waṭan al-Arabī [Peoples, sects, and ethnicities: Concerns of minorities in the Arab World]. Markaz Ibn Khaldūn.

- Ismael, T. Y., & Ismael, J. S. (2015). Iraq in the twenty-first century: Regime change and the making of a failed state. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315736631

- Jamal, A. A. (2012). Of empires and citizens: Pro-American democracy or no democracy at all? Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400845477

- Kalin, M., & Sambanis, N. (2018). How to think about social identity. Annual Review of Political Science, 21, 239–257. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-042016-024408

- Kenyon, P. (2009, May 18). Morocco campaigns against Shiite minority. National Public Radio. https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=104237288

- Khalaf, S. (1968). Primordial ties and politics in Lebanon. Middle Eastern Studies, 4(3), 243–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/00263206808700103

- Khalaf, S. (2002). Civil and uncivil violence in Lebanon: A history of the internationalization of communal conflict. Columbia University Press. https://doi.org/10.7312/khal12476

- Knupfer, G. (1947). Portrait of the underdog. Public Opinion Quarterly, 11(1), 103–114. https://doi.org/10.1086/265832

- Kuziemko, I., Buell, R. W., Reich, T., & Norton, M. I. (2014). ‘Last-place aversion’: Evidence and redistributive implications. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129(1), 105–149. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjt035

- Laurence, J. (2017, October 27). In Sunni North Africa, fears of Iran’s Shi‘a shadow. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-commentary-laurence-afterislamicstate/commentary-in-sunni-north-africa-fears-of-irans-shiite-shadow-idUSKBN1CV376.

- Lechkar, I. (2012). Modalités d’authentification parmi les chiites belgo-marocains. In B. Maréchal & F. E. Asri (Eds.), Islam belge au pluriel (pp. 113–126). Presses Universitaires Louvain.

- Lechkar, I. (2017a). Being a ‘true’ Shi‘ite: The poetics of emotions among Belgian-Moroccan Shiites. Journal of Muslims in Europe, 6(2), 241–259. https://doi.org/10.1163/22117954-12341349

- Lechkar, I. (2017b). The power of encounters and events: Why Moroccan Belgian Sunnis become Shia. In C. Timmerman, N. Fadil, I. Goddeeris, N. Clycq, & K. Ettourki (Eds.), Moroccan migration in Belgium: More than 50 years of settlement (pp. 367–380). Leuven University Press.

- Leenders, R., & Giustozzi, A. (in press). Whither proxy wars? Foreign sponsorship of pro-government militias fighting Syria’s insurgency. Mediterranean Politics. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2020.1839235

- Lipset, S. M. (1959). Democracy and working-class authoritarianism. American Sociological Review, 24(4), 482–501. https://doi.org/10.2307/2089536

- Lord, C. (2019). Sectarianized securitization in Turkey in the wake of the 2011 Arab Uprisings. Middle East Journal, 73(1), 51–72. https://doi.org/10.3751/73.1.13

- Lust-Okar, E. (2007). National and sub-national identities: State policies and implications in the context of regional instability. Quaderni di Relazioni Internazionali, 5, 14–25.

- Mabon, S. (2013). Saudi Arabia and Iran: Power and rivalry in the Middle East. I.B. Tauris.

- Mabon, S. (2020). Houses built on sand: Violence, sectarianism and revolution in the Middle East. Manchester University Press.

- Maghraoui, D. (2009). The strengths and limits of religious reforms in Morocco. Mediterranean Politics, 14(2), 195–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629390902985976

- Makdisi, U. (2000). The culture of sectarianism community, history, and violence in nineteenth-century Ottoman Lebanon. University of California Press.

- Maréchal, B., & Zemni, S. (2012). Conclusion: Analyzing contemporary Sunnite-Shiite relationships. In Maréchal & Zemni (Eds.), The dynamics of Sunni-Shia relationships (pp. 215–243). Hurst.

- Matthiesen, T. (2013). Sectarian Gulf: Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, and the Arab Spring that wasn’t. Stanford University Press.

- Mirshahvalad, M. (2019). Ashura in Italy: The reshaping of Shi‘a rituals. Religions, 10(3), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10030200

- Nasr, V. (2004). Regional implications of a Shi‘a revival in Iraq. The Washington Quarterly, 27(3), 5–24. https://doi.org/10.1162/016366004323090232

- Nasr, V. (2006). When the Shiites rise. Foreign Affairs, 85(4), 58–71, 73–4. https://doi.org/10.2307/20032041

- Nasr, V. (2016). The Shia revival: How conflicts within Islam will shape the future. W.W. Norton.

- Nasr, V. R. (2000). International politics, domestic imperatives, and identity mobilization: Sectarianism in Pakistan, 1979-1998. Comparative Politics, 32(2), 171–190. https://doi.org/10.2307/422396

- Nelson, S. (1984). Ulster’s uncertain defenders: Protestant political, paramilitary, and community groups and the Northern Ireland conflict. Syracuse University Press.

- O’Duffy, B. (1995). Violence in Northern Ireland 1969–1994: Sectarian or ethno‐national? Ethnic and Racial Studies, 18(4), 740–772. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.1995.9993889