ABSTRACT

The European Green Deal (EGD) marked the commitment of the European Union (EU) to a carbon-free, socially inclusive economic system. Even if conceived as an essentially domestic growth strategy, the EGD is inspiring EU diplomacy, as economic cooperation will be needed to realize the EGD’s ambitious vision. This profile aims to investigate and reflect on the potential implications of the EGD for the countries in the EU’s Southern Neighbourhood, especially in the energy sector, agriculture and food system, trade in raw materials, climate action, and circular economy. We expect the EGD to result in an increased investment in renewable energy, a reduction in emissions, green diplomacy, and funding opportunities for green projects and green infrastructures. The EGD brings with it attractive opportunities for a better cooperation on climate action and opportunities for job creation, green growth, and sustainable development. We believe that the EGD has the potential to be a win–win deal for the EU and its Southern Neighbours, with the EU goal to supply green inputs and of creating a market for green products.

The European Green Deal: Domestic or foreign policy?

The European Green Deal (EGD), an ambitious plan of action spanning the key policy areas of climate action, biodiversity, a sustainable food system, fisheries and agriculture, sustainable industry, smart mobility, clean and secure energy, energy-efficient construction, just transition, and renovation interventions, was introduced by the European Commission in 2019. While initially being intended as a domestic growth strategy, the EGD is set to take on a significant role in orienting development and regional policies. The EGD has also been reflected in the Regional Strategies, the most important of which are that for the Western Balkans, the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP), and that for Africa. In addition, the Neighbourhood, Development and International Cooperation Instrument (NDICI) sets a 25 per cent spending target for climate action and prospects priority areas of intervention in line with the policy areas specified by the EGD.

The European Union (EU) views the ENP as a crucial tool for implementing the EGD. In fact, the Renewed Partnership for the Southern Mediterranean contains a thorough economic strategy and seeks to make significant investments in a networked, hydrogen- and renewable-fuelled energy system. The text establishes a new Agenda for the Mediterranean towards ‘a green, digital, resilient and just recovery, guided by the Paris Agreement, the European Green Deal, and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development’ (EC, Citation2022). Among the key policy areas of the new agenda is the Green Transition, including climate resilience, energy, and the environment.

With this background in mind, this profile reflects on the potential implications of the EGD for the countries of the ENP-South, which includes Algeria, Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Palestine, Syria, and Tunisia. It focuses on the most important domains of economic interaction and related Green Deal targets. Overall, the purpose is to derive scenarios and differentiated policy recommendations for countries of the region on how to reap the benefits from the EU green transition while mitigating for (inevitable) backlashes.

This profile first presents the predicted impacts of the EGD within the main economic policy areas of energy, agriculture and food system, trade in raw materials, climate action and circular economy. Second, it summarizes the main outlooks that can be derived from this discussion to reflect on which ENP-South countries may stand out in which policy area. The profile then concludes with a more critical view on the EGD, trying to emphasize the political implications of the EGD for the countries of the region.

EGD and the ENP-South

A framework to analyse the major potential consequences of the EGD for the Southern Neighbours can be derived referring to the EGD’s main policy areas and how they are reflected in the EU’s development and investment plans for the region. Based on this, we examine the following main economic policy areas: energy, agriculture and food system, trade in raw materials, climate action and circular economy.

Energy

The EU is committed to supporting the development of renewable energy sources and improving energy efficiency in the region. This includes investing in wind and solar power, as well as supporting the development of energy-efficient buildings and industries. The EU is also promoting the use of green hydrogen as an alternative fuel, which could potentially provide new economic opportunities for the region. With its commitment to decarbonize the EU by 2050, the EGD is going to profoundly and rapidly change the energy sector and the patterns of energy demand from the Union.

In 2019, almost 38 per cent of European demand for crude oil was covered via imports from the Former Soviet Union (FSU); due to the sanctions imposed on Russia after the beginning of the war in Ukraine, the EU is now searching for new ways to secure its energy supply. According to the Registration of Crude Oil Imports and Deliveries in the European Union, while Saudi Arabia and Iraq make up for 15 per cent of oil deliveries to the EU, the oil-rich countries of the ENP-South supplied 11 per cent of crude oil imports in the EU in 2019. In particular, Libya and Algeria are important suppliers to the countries of the EU, delivering respectively 6.5 per cent and 3.5 per cent of total oil imports by the EU. The war in Ukraine is set to relaunch the importance of the Southern Neighbours as supplier of crude oil – as an example, in the second quarter of 2022, Libya delivered 7.7 per cent of total crude oil imports to the EU (Eurostat database).

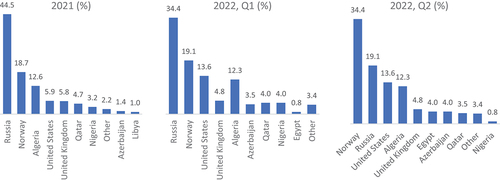

Natural gas, especially in the form of liquified gas and methane, is often recognized by the EGD as the transition fuel. Therefore, its demand can be predicted to expand in the mid-term. Also hereby, securing supply while diversifying sources of income are strategic issues. Within the ENP-South, Algeria is already an important supplier of natural gas to the EU – with a share of 7.9 per cent of EU imports, it was the third largest supplier of natural gas for the EU in 2019. In the fourth quarter of 2022, it delivered 9.1 per cent of natural gas import to the EU. As a consequence of the EU strategy to reduce dependency on Russian fuels (REPowerEU), Egypt ranked as 6th largest importer of natural gas to the EU in the second quarter of 2022 ().

Figure 1. Extra-EU imports of natural gas, shares (%) of main trading partners in 2021 and in 2022 (first and second quarter) (Data source: Eurostat database (Comext) and Eurostat estimates).

The EGD draws on plans to transform the Mediterranean into a gas hub, in which Egypt may play an increasingly important role alongside Israel and Cyprus. The sanctions placed on Russia are giving momentum to the significance of the Southern Neighbourhood as market for natural gas. The June 2022 trilateral agreement with Egypt and Israel on supplying Europe with LNG as part of the REPowerEU plan should be read in this context. However, the Mediterranean countries are also envisioned as a market for hydrogen, with the EU setting a target of importing 10 million tonnes of hydrogen from the region by 2030, and through this envisioning a creation of a significant hydrogen import route. The European Commission is working on the establishment of the Mediterranean Green Hydrogen Partnership between the EU and its Southern Neighbours. Furthermore, the significance of hydrogen is growing in the bilateral relations between the EU and both Egypt and Morocco, as exemplified by the initiation of the EU-Morocco Green Partnership.

The EGD is also linked to greater reliance on renewable energy. Due to its location in the sun belt, the ENP-South region holds immense potential for solar energy production, while certain countries within the region may also possess the capability to generate wind energy. The Agenda for the Mediterranean pledges to encourage investments in renewable energy and energy efficiency. Important EU goals include the generation of clean hydrogen and the integration of regional electricity markets.

The decrease in the cost of producing renewable energy and the rise in the proportion of renewables in the energy mix of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region’s countries are related trends that have been present since 2010. Being aware of the insufficiency of domestic green electricity and green hydrogen generation, the EU is watching these changes with interest and specifically cites electrical grid interconnections in its statements. Rising European demand for green electricity and green hydrogen will not be satisfied by domestic production alone. Thus, interconnected grids may enable importing solar and wind electricity, as well as hydrogen from the ENP-South.

Considering the possible effects of the EGD for the ENP-South, it must be emphasized that fuels and related products represent the big bulk of trade between the EU countries and the Mediterranean fuel exporters, such as Libya, Algeria, and Egypt. In general, the intention to decarbonize the economy will lead to a reduction in crude oil imports and in a temporary increase of demand for natural gas as transition fuel. However, the recent commitment to reduce dependency on Russian fuels will most probably result in an expedited increase of importance of fuel imports form the Southern Neighbours, meaning that it is currently difficult to predict what will be the net effect of this transition. Over the long term, however, the fuel-rich countries of the ENP-South will need to invest increasingly into electricity interconnection and green hydrogen, for which an international market with the EU is bound to be created.

In conclusion, navigating the contradiction between the short-term need for increased supply of fossil fuels and the long-term pathway to decarbonization in neighbouring countries is a significant challenge for the ENP. Adopting strategies focused on promoting energy efficiency, supporting the transition to renewable energy, encouraging regional cooperation, and promoting dialogue and engagement, may help the ENP-South – and especially Libya, Algeria, and Egypt – to address this challenge.

Agriculture and food systems

The Farm to Fork (F2F) strategy as the flagship EU agri-food policy within the EGD aims at creating a more sustainable and resilient food system in the EU. The F2F strategy aims to address challenges such as climate change, biodiversity loss, and public health by promoting sustainable food production, reducing food waste, and improving nutrition. For most of the ENP-South countries, the EU is also a significant trading partner regarding food items. Given the exclusion of agricultural products from the Euro-Mediterranean Association Agreements, bilateral agriculture protocols between the EU and several countries in the region were ratified. Adhering to the new agricultural standards will be a necessary step for the ENP-South to keep access to the EU market.

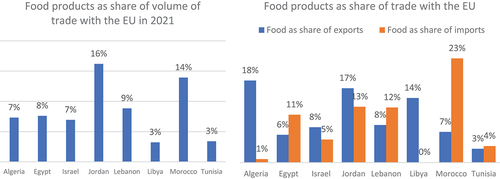

Food and drink items account for a sizable portion of trade between the EU and the countries of the ENP-South, although differences in patterns of imports from and exports to the EU market are notable. While Morocco, Lebanon, and Egypt export to the EU more than what they import in food products, the EU is a net exporter to Algeria, Israel, and Jordan ().

Figure 2. Food products and beverages as share of total volume of trade with EU-19 countries (Data source: Eurostat, Citation2023Footnote1).

Moreover, EU will need to make efforts to persuade its trading partners to increasingly adopt the new standards of organic farming, which may, at least temporarily, result in higher prices for consumers.

In an effort to promote organic agriculture and building integrated agri-food systems throughout the Mediterranean, the EU is financing networking initiatives and other projects. The EU’s Cross-Border Cooperation (CBC) initiative, which is carried out under the European Neighbourhood Instrument, is one of the major sources of funding for initiatives of this nature (ENI CBC Mediterranean Sea Basin Programme).

The EU has been in talks to transform the Association Agreements with Egypt, Morocco, Jordan, and Tunisia into Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreements (DCFTAs) since 2011 in response to the turmoil brought on by the Arab Spring. The DCFTAs’ objective is to establish a de facto free trade zone between the EU and its Southern Neighbours that includes agricultural and processed food goods, despite the fact that progress is varied.

On the positive side, the F2F strategy could provide new economic opportunities for ENP-South countries by promoting sustainable agriculture practices and increasing demand for organic and sustainably produced food. This could help to boost rural economies and create new jobs in the agriculture sector.

However, ENP-South countries may also face challenges in meeting the high standards and regulations set by the F2F strategy due to increased production costs.

The current general situation of the ENP-South countries in terms of the F2F strategy is mixed. Some ENP-South countries, such as Tunisia and Morocco, have made significant progress in promoting organic agriculture and increasing the area of land dedicated to organic farming. Tunisia ranks first in Africa and among the Arab countries in terms of certified area for organic farming, with almost all the organic production being exported (ProFound Advisers in Development, Organics & Development, Markus Arbenz, Citation2020). Other ENP-South countries, however, still face significant challenges in promoting organic agriculture, such as lack of infrastructure and support systems for organic farmers, including access to organic inputs, technical assistance, marketing channels, and access to fund.

Trade in raw materials

It is anticipated that demand for new essential raw materials like lithium, graphite, and cobalt will rise dramatically as a result of adopting green technology to become carbon free. The EU will need to import the minerals and metals required for the production of solar panels, wind turbines, li-ion batteries, fuel cells, and electric vehicles as there is a shift away from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources. There are few to no alternatives for certain minerals and metals, which have unique qualities. Among these are rare earths, of which China is the world’s top producer. By 2050, the European Commission projects a doubling of Europe’s consumption for raw materials. As a result, there is an increased risk to energy security due to the enormous increase in dependence on China. To avoid such an excessive reliance on China, the EU must endeavour to diversify its sources for rare earths and other commodities.

Raw material trade between the EU and the ENP-South accounts currently for a negligibly small portion of total commerce, barely reaching 5 per cent. Egypt, Tunisia, Morocco, and Lebanon are the countries that trade raw commodities with the EU in the largest quantities. An anticipated trend for the ENP-South may be an increase in demand for silicon and soda ash for solar panels and glass. Changes in the need for fertilizing raw materials, for which Morocco and Jordan are significant suppliers to the EU, are also to be anticipated. Most probably, however, as due to the limited availability in the ENP-South of the raw materials that will become critical for the green transition envisioned in the EGD, no dramatic changes in the patterns of trade in raw materials between the EU and its Southern Neighbours can be expected.

Climate action and circular economy

The EU is developing a coordinated strategy for sustainable growth and climate action in the region to raise climate ambitions in the partner countries and to streamline targets. There are initiatives on raising awareness, designing carbon pricing methods, and on climate action. International cooperation is envisioned as being viable in the area of financial instruments to promote the transition to green growth.

It is reasonable to expect that the ENP-South’s integration into European supply chains will be closely related to the adoption of common standards for a sustainable use of resources. The EU’s ambition to move towards a circular economy will inevitably lead to a new way of dealing with resources, reducing waste, and reintroducing them into the economic circulation.

Strengthening the EU’s leadership in the world is another objective of the EGD, as stated expressly by the Commission. If the EU adopts a proactive posture within the framework of the so-called Green Deal diplomacy, the aforementioned possible challenges for the ENP-South countries could be used as catalysts for the renewal of international alliances.

As a result, regarding climate action, we anticipate that the EU will participate in bilateral and multilateral negotiations to achieve climate goals, and that it will initiate negotiations at international conferences, encourage cooperation, and provide technical assistance to countries of the ENP-South to develop efficient mechanisms for green growth and climate governance, especially given that the region is particularly vulnerable to climate change. With funding programs like PRIMA and Horizon, science diplomacy is also being used to engage the ENP-South in climate action and the green transition.

In speaking about climate action, a special reflection is hereby due in regard to the Carbon-Border-Adjustment-Mechanism (CBAM). The system of carbon tariffs must ensure goods both from and outside of the EU are treated the same, it should avoid leakages (that is having emission intensive companies relocating to non-EU areas), and incentivize other countries across the world to also decarbonize. There are two problems with this. Since all emissions across the entire value chain must be taken into account, it is technically challenging to determine the emissions content of imports. Politically, trading partners can perceive this as an aggressive stance that violates WTO regulations and respond. There will likely be a range of responses – from support and potential policy replication, to opposition and tariff retaliation when the EU introduces a border tax on carbon emissions. Nonetheless, there are appeals to resist giving in to pressure and to work with other countries openly on such proposals.

In regard to the promotion of circular economy, the EU is making specific efforts in this area to quantify progress made by identifying and gathering indicators. A potential area of collaboration could be extending the proposed monitoring system to the surrounding countries. Also, the EU is committed to supporting the development of waste management systems in the Southern Neighbours and promoting the use of recycled materials. This could help to provide new economic opportunities in the recycling industry.

Outlook

The ENP-South countries have close trade links with the EU states chiefly because of their proximity to one another, among other reasons. Being the EGD, a comprehensive and articulated framework including different policy areas, the different countries of the ENP-South will be differently affected. Overall, the trade balance between the 19 members of the Euro area and the ENP-South is favourable to the latter when taken as a whole. To put it another way, the ENP-South region serves as a market for commodities imported from Europe.

The two biggest exceptions are Libya, from which EU members imported 6.5 per cent of their crude oil needs in 2019, and Algeria, which has only lately begun to play a significant role in the EU’s oil supply (EC, Citation2022). Those two countries, together with Egypt are going to be deeply affected by the reduction in EU demand for fossil fuels – the trend towards decarbonization needs to be taken seriously by these countries. However, as discussed, the transformation around energy will be far reaching – the EGD is exploring ways to substitute fossil fuels with other types of energy and the EU is actively seeking to create a supply network. Potentially, all the countries of the region are excellent candidates for renewable energy and green hydrogen production.

Regarding food systems, we are certain that the F2F strategy represents a significant opportunity for ENP-South countries to promote sustainable agriculture and improve the resilience of their food systems. In particular, the countries of the region should understand the chances of organic farming, which may enable them to find a profitable niche in accessing the EU market and increasingly specialize in higher-value horticulture products, as suggested by the OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook Citation2018. Tunisia, Morocco, as well as Lebanon and Jordan may have particularly good chances to invert the current trend towards stationary exports of agricultural products to the EU. Even though changing food prices have been often connected to social unrests in the whole region, we believe that an increase in prices due to organic farming adoption on a large scale coming from within the system will deal with the problem at its root. A significant challenge faced by agricultural producers in the region is the persistently low prices of agricultural products. Organic farming may enable producers to achieve more profitable gains while exporting their products, leading to increased income security also among farming communities. In addition, the entire Southern Mediterranean region is a net importer of cereals, the prices of which have already been rising due to the war in Ukraine. In this context, adopting organic farming may increase the resilience of the food systems in the ENP-South.

Despite the limited volume of trade in critical raw materials between the EU and the ENP-South, the changes associated with green technology adoption may also create chances for countries like Egypt, Tunisia, Morocco, Lebanon, but also for Morocco and Jordan. Silicon, soda ashes, and fertilizers may increase their importance in the trade with the EU. Interestingly, this may reflect into the creation of new jobs. Still, trade in raw materials is not expected to bring about a dramatic change in the economic outlook of the ENP-South following the EGD.

The southern Mediterranean countries are already hit by the effects of climate change, which are exacerbating income inequalities and migration trends. Investment into climate action and circular economy will help mitigating these negative effects and may lead over the long term to improved food security and reduced vulnerability.

Conclusion: the fine line between opportunities and political externalities

We believe that the ENP-South countries must consider the effects of the EGD given their closeness and tight economic, social, and political relations. The interests of these countries include anticipating potential effects of the EU action plan, being prepared to benefit from them, meeting newly established standards, and anticipating any potential short-term negative externalities.

The main conclusions of this profile are that the EGD will undoubtedly create and bring with it new potential for international collaboration and partnerships under the green agenda. However, it will also bring with it both opportunities and problems in the EU’s relations with specific ENP-South countries. We contend that through forging closer relationships and promoting economic stability, the EU may encourage the growth of hydrogen and renewable energy initiatives in partner countries. Nonetheless, a lack of considerate engagement with those countries can cause substantial losses and put a stop to global climate action.

Changing the EU’s energy system might have geopolitical ramifications on the EU energy balance and worldwide markets, on the oil- and gas-producing countries in the EU’s neighbourhood, on European energy security, and on global trade patterns. Finally, the new production patterns in the ENP-South countries resulting from the green transition initiated by the EGD will also have implications for the internal politics and political structures of the ENP countries, reinforcing or challenging those groups benefiting from the green transition. So, an important question for future research is how will the EGD and green transition reinforce or challenge authoritarian and democratic regimes in the South ENP?

We believe that by supporting the development of renewable energy sources and promoting energy efficiency, fostering the adoption of sustainable agriculture practices, investing in green infrastructure, and promoting circular economy and waste reduction, the EGD may help to create a more sustainable future for the ENP-South. The job creation that will be associated with these new investments may discourage migration and may be one of the main drivers of a more inclusive economic growth.

Encouraging regional cooperation, for example, through the creation of common markets for renewable energy, but also enforcing common production standards, the EGD may turn into an opportunity also in terms of promoting regional stability, dialogue and engagement among neighbouring countries.

However, there is indeed growing research confirming the need for a closer investigation of the political implications of the shift towards renewables. In fact, the ‘shifting towards renewables’ needs to be unpacked, and we must understand how the promotion, production, and contestations of renewables in the ENP-South will shape authoritarian practices. Renewable energy adoption may progressively erode the rentier nature of many countries of the region, reducing the power of traditional business elites and promoting competition. This process will be for sure characterized by some political frictions, as it is widely understood in the literature that such rentier nature of states is an obstacle to energy transition (Al‐Sarihi & Cherni, Citation2022; Emel et al., Citation2019). The argument is that the transition to renewable energy would undermine the core income of such governments – the rent – due to a decrease in export of natural resources. Nevertheless, new research is also analysing to what extent these governments may reproduce the centralized approach of rentierism in the green energy transformation, maintaining and reproducing in this way the authoritarian and rentier nature of their approach to natural resources (see the project of Schuetze ‘Renewable Energies, Renewed Authoritarianisms? The Political Economy of Solar Energy in the Middle East and North Africa’, as well as Schuetze & Hussein, Citation2023). On the other hand, it could be argued that the EGD is creating a market for green energy and increasing the opportunities for a green transition hand in hand with a democratization of the energy sector in such countries. The opportunities generated by the EGD transition may move even fuel rich countries of the region to embrace this trend. As a result, this may provide beneficial also towards a democratic transition of the region.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Due to the smaller size of trade flow with the EU, the figure does not include Palestine and Syria.

References

- Al‐Sarihi, A., & Cherni, J. A. (2022). Political economy of renewable energy transition in rentier states: The case of Oman. Environmental Policy & Governance, 2041. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.2041

- Databases

- EC. (2022). Fit for 55 the EU plan for a green transition, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/green-deal/fit-for-55-the-eu-plan-for-a-green-transition/

- Emel, A., Evrim, G., & Ö, S. (2019). (2022). Libya: Geopolitics, local dynamics, and external actors. Istituto Affari Internazionali.

- EuroStat Database. (2023). https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database

- OECD. (2018). The middle east and north Africa: Prospects and challenges. In OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2018-2027. Paris: OECD Publishing. 67–107. https://doi.org/10.1787/agr_outlook-2018-5-en

- ProFound Advisers in Development, Organics & Development, Markus Arbenz. (2020). Boosting Organic Trade in Africa, IFOAM – Organics International, Bonn/Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ). GmbH.

- Schuetze, B., & Hussein, H. (2023). The geopolitical economy of an undermined energy transition: The case of Jordan. Energy Policy, 180, 113655. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2023.113655