ABSTRACT

Although public opinion research has gained prominence in the Middle East and North Africa region since 2011, data on electoral behaviour and political attitudes are scarce and rarely have a comparative focus. This research note introduces a new post-election survey conducted after the 2019 Tunisian elections. The project contributes to the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES) database. In its 26-year history no country other than Israel was ever part of the CSES from the Middle East and North Africa region. Tunisia is the first Arab country to be covered in the CSES. We introduce this new research resource, its methodology, and its themes. We also provide some preliminary results from the main topic of the CSES between 2016 and 2021: populist attitudes. Using a three-dimensional model, we find that people who score high on the populist attitudes measures do not necessarily have a higher preference for populist parties or candidates. Contrary to consistent results from advanced industrial democracies, we also find that people who endorse nativism are more likely to support left-wing parties. This research note illustrates the importance of such datasets and how they contribute to a specific topic: understanding populism across multiple contexts.

Introduction

Since Tessler’s statement about the scarcity of public opinion research in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, scholars of the area have come a long way (Citation2011). In the aftermath of the 2011 mass uprisings, there has been a significant surge in public opinion research. Scholars have published innovative data and insights on a broad spectrum of topics, from protest behaviours and preferences for regime type to political attitudes (Doherty & Schraeder, Citation2018; Hoffman & Jamal, Citation2014; Ketchley & El-Rayyes, Citation2021; Nugent, Citation2019). Employing both observational and experimental methods, a number of these studies concentrate on the individual differences underpinning core political values, views, and beliefs (Blackman & Jackson, Citation2021; Grewal et al., Citation2019; Hoffman & Jamal, Citation2012). Comparisons have also been drawn among MENA countries (Beissinger et al., Citation2015; Hoffman, Citation2020). However, compared to the wealth of survey research conducted in Western nations, particularly the United States, studies of Middle East politics tend to be less plentiful. There is a marked dearth of research calling for comparative insights that facilitate cross-regional comparisons, especially on themes paramount to political scientists. Notably, while there’s access to significant comparative resources like the Arab Barometer, the World Value Survey, and the International Social Survey Programme, these resources broadly focus on social, political, and economic issues of ordinary Arab citizens rather than concentrating on electoral behaviour and turnout.

This note introduces the first Arab contribution, a 2019 election survey of Tunisia, to the most detailed focus on electoral behaviour project – the Comparative Study of Election Systems (CSES).Footnote1 Since its 1996 launch, the CSES has become the primary coordination hub for nationally representative post-election surveys from over 50 countries. CSES inclusion standards ensure that national election studies produce publicly available, high-quality, cross-country comparable survey data on political attitudes and behaviours and a 5-year rotating module of salient thematic political subjects with global importance.Footnote2 This Tunisian survey contributes to the 5th module of the CSES (2016–2021) thematically focused on populism (Hobolt, Citation2016).

The data detailed in this research note enables scholars to study diverse political topics. It offers researchers the opportunity to explore and compare Tunisia, which at the time of the data collection, was the most successful electoral democracy in the Arab world. No existing (publicly available) survey contains questions measuring people’s populist attitudes and not party- or country-level data (Plaza-Colodro et al., Citation2023). To demonstrate the utility of such data, we analyse the CSES Module 5 core themes’ impact on political preferences and voting behaviour. We find that people who score high on the populist attitudes do not prefer populist parties or candidates.

CSES in Tunisia

Overview and survey design

The parliamentary elections in Tunisia took place on 6 October 2019. It was also sandwiched between the two rounds of the presidential election on 15 September and 13 October. After delays due to COVID, the Tunisian post-election survey was fielded between 18 July and 30, 2020. The computer-assisted face-to-face survey was administered by One to One for Research and Polling in Tunisian Arabic.Footnote3 The CSES source questionnaire was translated in line with the CSES protocol, including translation, back-translation into English, and expert review before finalization.

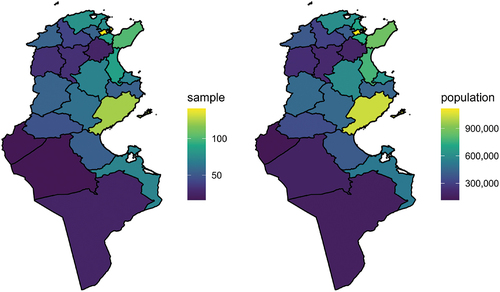

Tunisia is divided into 24 governorates, 264 delegations, and 2,084 sectors. For survey sampling, first, Tunisia was divided into 46 primary sampling units, an urban and rural area of all governorates (Tunis and Monastir are all urban, yielding 46 total instead of 2 × 24 = 48). These were then sampled with the population proportional to size method, from which 188 sectors were selected the same way. The 2084 sectors of Tunisia break down to 27,466 blocks of 400, yielding the total adult citizen population. One such block was chosen for each of the 188 sampled sectors, where eight interviews were conducted using a random walk procedure. Within households, respondents were selected using the Kish table procedure (Kish, Citation1949), alternating between the selection of men and women. Failed interviews were reconducted following the same procedure within the block. This sampling frame ensured good coverage of the entire population.Footnote4 Of the 1504 sampled individuals, 1477 interviews were kept after data quality checks by the CSES team. Only Tunisian citizens aged 18 or above were interviewed.Footnote5

The contents of the CSES data

The CSES Tunisia data has both a micro and a macro component. The micro-component includes topics such as political preferences (like-dislike for parties and leaders), voting behaviour,Footnote6 political interest, party rankings on ideological dimensions, political ideologies, and module-specific thematic topics. The survey also includes a list of socio-demographic variables: gender, age, education, social class, occupation, income, religiosity, ethnicity, rural or urban residence, primary electoral district, and marital or civil union status and metadata such as the interviewer ID, gender, and time to complete the questionnaire. In addition to the survey data, CSES country teams file macro-level information, including country experts’ evaluation of political parties, politicians, and the electoral system. These macro reports are valuable resources for country comparisons.

Populism

The central theme of Module 5 of the CSES is the study of populism (consisting of populism’s diverse components of anti-elitism, people-centrism, attitudes towards representative democracy, and authoritarian support for a charismatic leader), perceptions of outgroups such as immigrants and minorities, and nativism. With the rise of populists in Europe, Latin America, and other parts of the world, political scientists are increasingly worried about the future of democracies (Mudde, Citation2013). Mudde defines populism, in its ideational form, as a worldview where the ‘good’ and ‘pure’ people are being exploited by a corrupt and conniving elite (Citation2004). This ideational definition is suited to study populism both from a supply perspective (parties, candidates – see Mudde & Kaltwasser, Citation2017; Urbinati, Citation2014) and from the demand side (general attitudes – see Akkerman et al., Citation2014; Castanho Silva et al., Citation2020; Hawkins et al., Citation2012). Alternative definitions of populism focus on organizational structures of populist movements or leadership styles (see Kefford et al., Citation2022, for a recent exception).

In Europe, populism often goes hand-in-hand with radical right ideology. For this reason, populist attitudes were expanded with two additional dimensions: attitudes towards the outgroups such as immigrants and minorities, and nativism. Mudde and Rovira-Kaltwasser (Citation2013) distinguished between inclusionary (usually Latin American left-wing) and exclusionary (right-wing) forms of populism where the ‘people’ are defined in more or less inclusive ways. For example, at the core of Latin American populist success is enfranchising ethnic minorities and natives who were previously detached from political participation. Whereas European populists tend to exclude immigrants and minorities, and succeed through the mobilization of disgruntled lower classes less tolerant of these groups taking their jobs and privileges that previously were exclusive to those at the core of society. Outgroup attitudes, the perception of, and the (potentially nativist) definition of the people are at the core of understanding populism and the challenges it poses.Footnote7

To demonstrate the power of the CSES and the importance of contributing data from the MENA region to such comparative survey projects, we examine the predictability of these measures and shed light on their significance in Tunisia. Throughout the 2019 Tunisian elections, analysts and journalists have been associating the shifting political landscape with the rise of populist actors globally. This unique dataset allows us to empirically test the following research question: do populist, exclusionary, and nativist attitudes predict populist party preferences and populist vote in Tunisia the way the CSES Module 5 team hypothesizes and the way it has been shown in advanced industrialized democracies? To test the three-dimensional attitudinal model’s applicability to Tunisia, we first apply an exploratory factor analysis (EFA). Then to test how the dimensions relevant to Tunisia predict party and candidate preferences, political participation, and vote choice, we apply Ordinary Least Squared (OLS) regressions and logistic regressions. We conclude by discussing how the results match theorization from advanced industrialized democracies.

Results

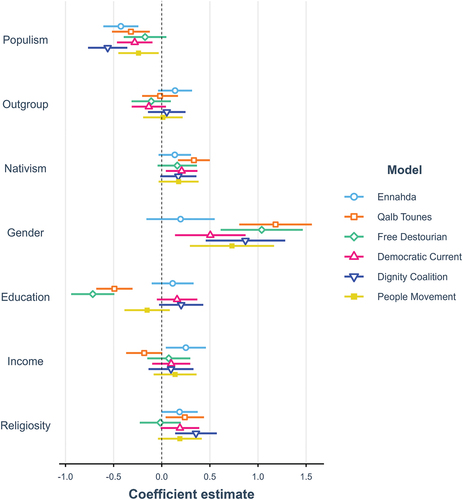

As expected, EFAFootnote8 results reveal three dimensions. The populism subscale is mostly described by anti-elitism items, whereas the outgroup subscale captures the items where illicit harm is caused by immigrants. All nativism items are relevant for the nativism subscale. Keeping only the survey items that the factor analysis deemed relevant for the subscales, we operationalized the populist, outgroup, and nativist dimensions,Footnote9 by computing the mean across the items. The support for parties and political leaders is regressed on the three dimensions using OLS regression. It was measured using an 11-point scale (0 to 10) by asking how much the respondent likes or dislikes each party and party leader. The regression model controls for gender, education, income, and religiosity (measured by religious service attendance). Populist attitudes’ predictive power of populist support is well established in advanced democracies (Hawkins & Littvay, Citation2019; Van Hauwaert & Van Kessel, Citation2018). Parties competing in the 2019 Tunisian election considered populist by scholars (Meddeb, Citation2020; Mohamad Shukri & Smajljaj, Citation2020) and the media are Qalb Tounes party (Grewal, Citation2019), Dignity Coalition (Lorch & Chakroun, Citation2020), and the Free Destourian party (Wolf, Citation2020). Some scholars coined new terms to distinguish between two types of populism in Tunisia: ‘secular populism’ refers to the Free Destourian party and its leader Abir Moussi, while ‘Islamist populism’ refers to the Dignity Coalition Party (Brumberg, Citation2021). This is somewhat like the Spanish case where both left-wing (Podemos) and right-wing (Vox) populist parties exist. Results in show that the findings from the literature from advanced industrial democracies do not stand.Footnote10

A higher level of populism, or as it is better conceptualized in Tunisia – anti-elitism is not predictive of the support for any of the parties. Anti-elitism predicts party support negatively for all parties, and this result is statistically significant for two of the three so-called populist parties: Qalb Tounes and the Dignity Coalition. Rejection of outgroups is not associated with support for any of the parties. Finally, those who endorse the nativist sentiments are more likely to support parties considered left-wing: Qalb Tounes and the Democratic Current.

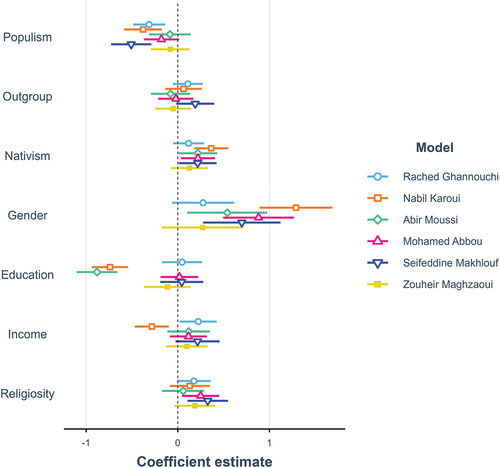

To check whether these results,Footnote11 are specific to parties or can also be validated for political candidates, we test the same models using the support for the parties’ leaders presented in . The regression model yields similar results for people with low anti-elitism supporting most of these leaders.Footnote12 Attitudes towards the outgroup are not significantly associated with support for any leaders. Finally, people who endorse nativist attitudes tend to be more likely to support the left-wing candidates (Nabil Karoui, Abir Moussi, and Mohammed Abbou) and the right-wing candidate Seifeddine Makhlouf.

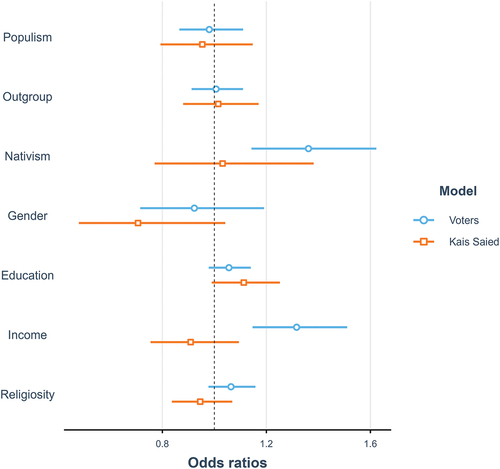

We additionally test the predictive power of CSES Module 5 themes by investigating their impact on voter participation and voting behaviour.Footnote13 Logistic regression results () show no significant differences in populist or outgroup attitudes between those who voted and those who did not. However, nativist attitudes are a significant predictor of voting. A point increase on the 5-point nativism scale increases the odds of voting by 36 per cent.

Figure 3. Odds Ratios (95 per cent CI). Voters are compared to non-voters, and voters of Kais Saied are compared to all other presidential candidates.

Finally, we look at these themes’ impact on vote choice. Kais Saied, elected to become the president of Tunisia, was an outsider candidate from academia. Journalists and scholars have repeatedly labelled Kais Saied a populist leader because of his speeches and main slogan – ‘the people want!’ (Brumberg, Citation2021; Lakhal, Citation2022). Theoretically, this constitutes the cleanest test of vote choice from a Tunisian context. Using another logistic regression model, we empirically test if those with populist, anti-elitist attitudes vote for Kais Saied vs. other candidates in the first round of the presidential elections.Footnote14 Interestingly, none of the three dimensions included in Module 5 predict voting for Kais Saied ().

General discussion

This note mainly aims to introduce the CSES project in Tunisia and highlight its importance. To illustrate this, we test the capacity of populist, outgroup, and nativist attitudes to explain party and candidate support, political participation, and vote choice. The factor analysis highlights that people-centric and authoritarian components of populist attitudes do not go hand in hand with anti-elitism, suggesting populism is not such a coherent concept in Tunisia as elsewhere. And responses to anti-out-group sentiments are consistent only in items where harm is involved. Only the items on nativism behave in line with what is seen in advanced industrial democracies, but nativism’s prediction of the left-wing candidate and party support deviates from the expectations of the classical voting behaviour literature (Anderson, Citation1991; Dunn, Citation2015; Rydgren, Citation2007). Populist attitudes in Tunisia are not predictive of populist party or candidate support, nor is it tied to the selection of a populist candidate. In fact, it seems that a lack of anti-elitism is what’s more important to support any of the political parties or candidates on offer. Only nativist sentiments predict political participation suggesting that those high on nativism care more about politics.

To explain these findings, we argue that the support for parties and leaders in the 2019 Tunisian elections was not primarily driven by populism at the individual level. While some politicians were labelled ‘populist’, other factors were more crucial in shaping political attitudes and vote choices. During the 2019 elections, several successful parties and candidates had no previous political involvement, such as the Dignity Coalition and Kalb Tounes. Apparently, the public was motivated by newcomers. The negative association between anti-elitism indicators and support for all parties, and four out of six leaders suggests that Tunisians generally hold negative perceptions about the political elite, regardless of their populism. Should we refrain from labelling these actors as populist? We contend that it may not be inaccurate to classify them as populist, particularly according to the commonly accepted definition. Nevertheless, it is crucial to acknowledge that Tunisians do not chose based on their populist attitudes or the parties’ populist label.

The outlined Tunisian deviations from the theoretical expectations are not unique when measuring populist dimensions. Castanho Silva et al. (Citation2020) also pointed to the authoritarian rule by a charismatic leader item in the CSES as a problematic indicator of populist attitudes in multiple contexts they explored. Jungkunz, Fahey and Hino (Citation2021) show how the CSES populism scale does not predict populist vote in some contexts, namely when populists are in power (see also Todosijević et al., Citation2022). But the deviations presented in the case of Tunisia go well beyond these findings, especially when highlighting nativist support for left-wing parties and politicians (see similar results in Mehrez, Citation2023).

The purpose of this note was not to make a substantive contribution to how populism functions in Tunisia, though the findings presented here could easily spawn entire comparative research agendas for more in-depth qualitative or quantitative analyses. It was to demonstrate the utility of high-quality post-election surveys that are useful for comparative research. These findings are only scratching the surface of populist attitudes research across contexts. Questions on political interest, political news consumption, political efficacy, corruption perception, policy preferences, government performance, economic performance evaluations, satisfaction with democracy, representation quality, ideology, partisan attachment, and additional demographics available in the CSES dataset remained untapped in the analysis presented. Comparisons with countries quite different from Tunisia, like the industrial advanced democracies, or ones closer in religious and cultural heritage such as Turkey and Albania, comparisons with third wave democratization countries, not to mention culturally divergent MENA countries like Israel, can offer a wealth of research possibilities. It is our hope that the region will see not only the continued exercise of meaningful elections but also a growing interest in comparative electoral research along the lines represented by the reviewed Tunisian CSES study.Footnote15

Acknowledgement

Special thanks go to the CSES team and the CSES secretariat for their unwavering support, offering valuable feedback and guidance throughout the duration of the project. Our gratitude also extends to CEU for generously providing the funding for this survey. An earlier version of this research note was presented at the Psychology of Authoritarianism Workshop held at Princeton University in December 2022. We extend our appreciation to both the discussants and all attendees, whose contributions were instrumental in enhancing the quality of this paper. Lastly, we express our deep appreciation for the constructive input from the reviewers, which significantly elevated the quality of this research note. The data and replication materials are available at: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/KYUNQX

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The project was funded by CEU’s Research Support Scheme’s grant to CEU’s MENAS research group.

2. More details about the CSES project and data are available at: https://cses.org/ (accessed on 03.08.2023). Micro and macro level reports can be accessed here: https://cses.org/data-download/cses-module-5–2016–2021/

3. One to One for Research and Polling is a survey firm with regional coverage who is also the partner for the Afro barometer, the Arab Barometer and projects like the UNICEF CAP survey. For more info visit www.121polling.tn

4. In addition to descriptive statistics, a choropleth map is also provided in Appendix B to compare the population to the survey sample distributions.

5. Response rate of the survey reached 63.8 per cent and the average duration of an interview is about 21 minutes.

6. In the parliamentary election, the recorded turnout rate was approximately 41.7 per cent, while the survey data indicated a slightly lower figure of 33.6 per cent. For the first round of the presidential election, the turnout stood at around 49 per cent based on official records, whereas the survey reported a turnout of 48.9 per cent. In the second round of the presidential election, the actual voter turnout reached about 54 per cent, whereas the survey data showed a turnout of 50.4 per cent. Other comparisons between the survey sample and the census data can be found in Table 11 in Appendix B.

7. See Appendix A for a full list of the items in the module.

8. Full results of the EFA can be found in Appendix C. Bolded items are the ones kept for the analysis.

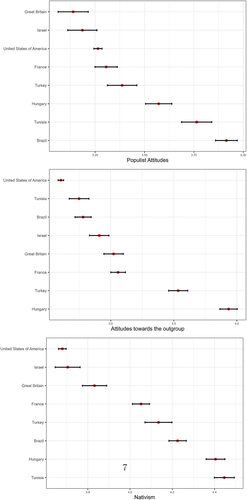

9. The distribution of items from each subscale can be found in Appendix B. Additionally, comparisons of the averages on each subscale has been conducted in seven other countries from the CSES and included to Appendix B.

10. Full results can be found in Appendix B.

11. We also run the same models for parties/leaders support by subsetting only the voters from the sample. The results mostly remain the same. (Appendix E, Tables E1 and E2).

12. Result is still negative but not statistically significant for Abir Moussi and Zouheir Maghzaoui. Full results can be found in the online Appendix D.

13. Full results can be found in the online Appendix E.

14. This analysis excluded non-voters.

15. See our collaborative platform on Arab Elections studies: https://arabelections.com/, accessed on 03.08.2023

References

- Akkerman, A., Mudde, C., & Zaslove, A. (2014). How populist are the people? Measuring populist attitudes in voters. Comparative Political Studies, 47(9), 1324–1353. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414013512600

- Anderson, B. R. O. (1991). Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism (Rev. ed.). Verso.

- Beissinger, M. R., Jamal, A. A., & Mazur, K. (2015). Explaining Divergent Revolutionary Coalitions: Regime Strategies and the Structuring of participation in the Tunisian and Egyptian Revolutions. Comparative Politics, 48(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.5129/001041515816075132

- Blackman, A. D., & Jackson, M. Gender Stereotypes, political Leadership, and voting behavior in Tunisia. (2021). Political Behavior, 43(3), 1037–1066. Article 3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-019-09582-5

- Brumberg, D. (2021). As 2021 begins, rival populisms menace Tunisia’s democracy. Arab Center Washington DC. https://arabcenterdc.org/resource/as-2021-begins-rival-populisms-menace-tunisias-democracy/

- Castanho Silva, B., Jungkunz, S., Helbling, M., & Littvay, L. (2020). An Empirical Comparison of seven populist attitudes scales. Political Research Quarterly, 73(2), 409–424. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912919833176

- Doherty, D., & Schraeder, P. J. (2018). Social Signals and participation in the Tunisian Revolution. The Journal of Politics, 80(2), 675–691. https://doi.org/10.1086/696620

- Dunn, K. (2015). Preference for radical right-wing populist parties among exclusive-nationalists and authoritarians. Party Politics, 21(3), 367–380. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068812472587

- Grewal, S. (2019, September 16). Political outsiders sweep Tunisia’s presidential elections. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2019/09/16/political-outsiders-sweep-tunisias-presidential-elections/

- Grewal, S., Jamal, A. A., Masoud, T., & Nugent, E. R. Poverty and Divine Rewards: The electoral Advantage of Islamist political parties. (2019). American Journal of Political Science, 63(4), 859–874. Article 4. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12447

- Hawkins, K., & Littvay, L. (2019). Contemporary US populism in comparative perspective. Elements in American Politics. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108644655

- Hawkins, K., Riding, S., & Mudde, C. (2012). Measuring populist attitudes.

- Hobolt, S. B. (2016). The Brexit vote: A divided nation, a divided continent. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(9), 1259–1277. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1225785

- Hoffman, M. (2020). Religion and Tolerance of Minority Sects in the Arab world. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 64(2–3), 432–458. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002719864404

- Hoffman, M., & Jamal, A. (2012). The Youth and the Arab Spring: Cohort differences and Similarities. Middle East Law and Governance, 4(1), 168–188. https://doi.org/10.1163/187633712X632399

- Hoffman, M., & Jamal, A. Religion in the Arab Spring: Between two Competing Narratives. (2014). The Journal of Politics, 76(3), 593–606. Article 3. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381614000152

- Jungkunz, S., Fahey, A. R., Hino, A., & Daoust, J.-F. (2021). How populist attitudes scales fail to capture support for populists in power | PLOS ONE. PLoS One, 16(12), e0261658. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261658

- Kefford, G., Benjamin, M., & Werner, A. (2022). Populist attitudes: Bringing Together ideational and Communicative Approaches—Glenn Kefford, Benjamin Moffitt, Annika Werner, 2022. Political Studies, 70(4), 1006–1027. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321721997741

- Ketchley, N., & El-Rayyes, T. (2021). Unpopular protest: Mass Mobilization and attitudes to democracy in post-Mubarak Egypt. The Journal of Politics, 83(1), 291–305. https://doi.org/10.1086/709298

- Kish, L. (1949). A procedure for Objective Respondent selection within the Household. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 44(247), 380–387. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1949.10483314

- Lakhal, M. (2022). The ghost people and populism from above: The Kais Saied case. Arab Reform Initiative. https://www.arab-reform.net/publication/the-ghost-people-and-populism-from-above-the-kais-saied-case/

- Lorch, J., & Chakroun, H. (2020). Salafism meets populism: The Al-Karama Coalition and the malleability of political Salafism in Tunisia. Middle East Institute. https://www.mei.edu/publications/salafism-meets-populism-al-karama-coalition-and-malleability-political-salafism

- Meddeb, H. (2020). Tunisia’s Geography of Anger: Regional Inequalities and the rise of populism. Carnegie Middle East Center, 19, 201–13.

- Mehrez, A. (2023). When right is left: Values and voting behavior in Tunisia. Political Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-023-09879-6

- Mohamad Shukri, S. F., & Smajljaj, A. (2020). Populism and Muslim democracies. Asian Politics & Policy, 12(4), 575–591. https://doi.org/10.1111/aspp.12553

- Mudde, C. (2004). The populist Zeitgeist—Mudde—2004—government and Opposition—Wiley online Library. Government and Opposition. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x?casa_token=Wy0jXdkCFN0AAAAA:smbLjcFuykQ0Yz0BsJ_9FXmCYpEb1zSk97Tlkk7y2JOnJYORdY1kFijI2M9PIzqmbdqTeb76wGefBQ

- Mudde, C. (2013). Three decades of populist radical right parties in Western Europe: So what?: Three decades of populist radical right parties in western europe. European Journal of Political Research, 52(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2012.02065.x

- Mudde, C., & Kaltwasser, C. R. (2017). Populism: A very short introduction. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/actrade/9780190234874.001.0001

- Mudde, C., & Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2013). Exclusionary vs. Inclusionary populism: Comparing Contemporary Europe and Latin America. Government and Opposition, 48(2), 147–174. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2012.11

- Nugent, E. R. (2019). New innovations in public opinion research in the broader Mediterranean region. Mediterranean Politics, 24(3), 376–383. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2017.1419811

- Plaza-Colodro, C., Tomé-Alonso, B., & Miranda, N. (2023). Islamist populism? Exploring the MENA region from a comparative and empirical perspective. Mediterranean Politics, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2023.2203562

- Rydgren, J. (2007). The Sociology of the radical right. Annual Review of Sociology, 33(1), 241–262. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.33.040406.131752

- Tessler, M. (2011). Public opinion in the Middle East: Survey research and the political Orientations of Ordinary citizens. Indiana University Press.

- Todosijević, B., Pavlović, Z., & Komar, O. (2022). Measuring populist ideology: Anti-elite orientation and government status. Quality & Quantity, 56(3), 1611–1629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-021-01197-5

- Urbinati, N. (2014). Democracy Disfigured opinion, Truth, and the people. Harvard University Press.

- Van Hauwaert, S. M., & Van Kessel, S. (2018). Beyond protest and discontent: A cross-national analysis of the effect of populist attitudes and issue positions on populist party support. European Journal of Political Research, 57(1), 68–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12216

- Wolf, A. (2020). The Counterrevolution Gains Momentum in Tunisia: The rise of Abir Moussi. POMED, 7.

Appendix A

PopulismDo you strongly agree, somewhat agree, neither agree nor disagree, some- what disagree, or strongly disagree with the following statements?

POP1 What people call compromise in politics is really just selling out on one’s principles

POP2 Most politicians do not care about the people

POP3 Most politicians are trustworthy

POP4 Politicians are the main problem in Tunisia

POP5 Having a strong leader in government is good for Tunisia even if the leader bends the rules to get things done

POP6 The people, and not politicians, should make our most impor- tant policy decisions

POP7 Most politicians care only about the interests of the rich and powerful

OutgroupsDo you strongly agree, somewhat agree, neither agree nor disagree, somewhat disagree, or strongly disagree with the following statements?

OGR1 Minorities should adapt to the customs and traditions of Tunisia

OGR2 The will of the majority should always prevail, even over the rights of minorities

OGR3 Immigrants are generally good for Tunisia’s economy

OGR4 Tunisia’s culture is generally harmed by immigrants

OGR5 Immigrants increase crime rates in Tunisia

NativismSome people say that the following things are important for being truly Tunisian. Others say they are not important. How important do you think the following is for being truly Tunisian: very important, fairly important, not very important, or not important at all?

NAT1 To have been born in Tunisia

NAT2 To have Tunisian ancestry

NAT3 To be able to speak Tunisian Arabic (Derja)

NAT4 To follow Tunisia’s customs and traditions

Appendix B

Table B1. Comparison between population estimates and unweighted survey distribution on key variables: age, education, and gender.

Table B2. Descriptive statistics of some key variables from the CSES dataset.

Appendix C

Table C1. Exploratory factor analysis using the 16 items from the CSES module 5 scales (N = 1477). Items with loading 0.3 bolded and retained for the next analysis. Model fit indices: RMSEA = 0.04, CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.93, SRMR = 0.019. Factor rotation used: Geomin.

Appendix D

Table D1. Regression models for political parties: Entries are regression coefficients with standard errors in parentheses.

Table D2. Regression models for leaders of leaders: Entries are regression coefficients with standard errors in parentheses.

Appendix E

Table E1. Regression models for voters among political parties’ supporters: Entries are regression coefficients with standard errors in parentheses.

Table E2. Regression models for voters among party leaders’ supporters: Entries are regression coefficients with standard errors in parentheses.

Table E3. Logit regression models: standard errors in parentheses. The reference category for model (1) are non-voters in the presidential elections. The reference category in model (2) are all other presidential candidates.