ABSTRACT

Since the 1990s, migration has featured prominently in Euro-Mediterranean relations. The EU migration policy has progressively shifted from a normative-comprehensive approach tackling the root causes of migration through development aid towards a control-oriented toolbox designed to immediately stop migration flows to Europe. This change has blemished the EU’s image as a normative power and contravened the region-building logic of the Barcelona Process. Contributing to the emotional turn in European Foreign Policy, this article argues that this shift corresponds to the behaviour of an actor under the grip of fear. The securitization of migration has permeated the EU institutions and contributed to the social construction of fear, leading to the emergence of fearful emotional practices. Based on the emotion discourse analysis of relevant EU documents, this article highlights the importance of fear as driver of policy change, triggering the EU to deviate from its own normative commitments in its external relations.

Introduction

Migration from the Mediterranean neighbourhood remains a challenge for the European Union (EU). In 2020, the European Commission (EC) proposed ‘a new Pact on Migration and Asylum’ to make the EU ‘a model of how migration can be managed sustainably and with a human approach, but effectively’. It is not the first EU’s attempt to balance efficiency and human rights protection in migration management. So far, however, the record has been mixed. Since the Barcelona Process (1995), the EU policy has shifted from a normative-comprehensive approach to tackle the root causes of migration through development aid towards a control-oriented toolbox (i.e., policing, surveillance, and militarized measures) aimed at immediately stopping migration flows to Europe. But why and how has this shift in the EU migration policy happened? Against the backdrop of rising populism in Europe, understanding the drivers behind this change is timely. Not only does ‘Fortress Europe’ blemish the EU’s image as a normative power and contravenes the region-building spirit of the Barcelona Process. The current migration policy also has detrimental implications on refugee protection, stability in sending and transit countries, and on the EU’s external relations.

This article explains the shift in EU migration policy towards the control-oriented approach by arguing that it corresponds to the behaviour of an actor acting under the influence of fear. Following the constructivist approach to emotions emphasizing their intersubjective and sociocultural character (Harré, Citation1986), we hold that the securitization of migration has permeated the EU institutions and contributed to the social construction of fear, leading to the emergence of fearful emotional practices at the EU level. Emotional fearful practices in the form of externalization of control betray a reflex of closure and overprotection typical of a fearful actor aiming at keeping the perceived threat at bay. Drawing on the emotional turn in IR, which conceives emotions as phenomena that drive decisions, motivate actions, and define relationships (Jeffery, Citation2012), this study reveals the link between the inherent social construction of fear in securitization processes and the adoption of a security-driven migration policy at the expense of the EU’s normative commitments. As such, it emphasizes the emotional component of securitization processes that has largely been overlooked.

This study makes a threefold contribution to the EU migration policy literature. First, conceptualizing the EU as an emotional actor contrasts with traditional views of the EU as either an ethical power, aspiring to be a force for good through the promotion of its norms and values (Manners, Citation2002) or as a rational actor pursuing material interests (Hyde Price, Citation2008). Contributing to the emotional turn applied to the EU (Pace & Bilgic, Citation2018; Smith, Citation2021; Terzi et al., Citation2021), we examine the under-theorized emotion of fear as a driver of policy change at the EU level, including its social construction through securitization and its impact in the form of fearful emotional practices. We show that the EU does not only respond emotionally to the violation of its norms by third parties. Negative emotions, like fear, can also lead the EU to violate its own norms. Secondly, while evidence about the securitization of migration in the EU abound (Huysmans, Citation2006; Léonard & Kaunert, Citation2022), less attention has been given to the emotional component inherent in this dynamic (except Sanchez Salgado, Citation2022; Van Rythoven, Citation2015). By putting the spotlight on the missing link(s) between the securitization of migration, the social construction of fear, and its impact on the EU policy response, we sharpen our understanding of the emotional mechanism at play in these framing endeavours. Empirically, rather than looking at specific events (Cassarino & Lavanex, Citation2012; Noutcheva, Citation2015), the article constitutes the first attempt to provide a comprehensive analysis of the evolution of EU migration policy towards the Mediterranean, spanning a period of 20 years, to highlight the persisting tension between the EU’s normative commitment and actions.

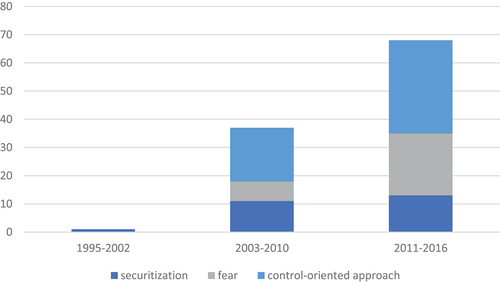

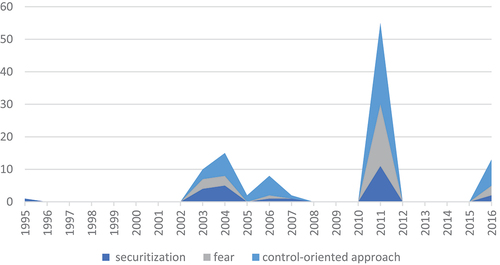

Methodologically, we scrutinize the EU migration policy towards the Mediterranean, as the Southern neighbourhood has posed significant migratory challenges, becoming the focus of numerous EU initiatives. Simultaneously, debates about migration in Europe have been emotionally loaded, turning this instance into a critical case (i.e., the most likely case to exhibit a given outcome) (Gerring, Citation2007, p. 247). We conducted an emotion discourse analysis (EDA) based on twenty-eight EU documents (including European Commission’s communications, European Council resolutions and press releases) outlining the EU migration policy in the Euro-Mediterranean context to unpack the link between securitization, its inherent emotional component related to fear and resulting emotional fearful practices. The timeframe (1995–2016) corresponds to a coherent period, starting with the launching of the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership (EMP) and covering milestones, such as the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) (2004), and the policy developments following the Arab Spring (2011), including the refugee crisis. By comparing the EU discourse and migration policy around these three turning points, we found that in the absence of securitization – and hence fear, the comprehensive approach to migration prevails. Conversely, the securitization of migration encapsulating expressions of fear affects the policy response through the enactment of fearful practices aimed at minimizing risks. Even when the EU attempts to revise its approach to match its own values, this reflex of closure persists, indicating that fear has been institutionalized at the EU level.

Section I reflects on the emotional turn applied to the EU and discusses the ways through which the EU has been conceptualized as an emotional actor. Section II draws on the IR literature on emotions and securitization to unpack the social construction of fear through securitization and its effects in the enactment of fearful emotional practices based on exclusion. Section III illustrates this argument through a comparative analysis of the EU migration policy in the Euro-Mediterranean context.

The EU as an emotional actor

More than two decades after Crawford’s (Citation2000) to consider emotions in IR, a consensus exists in the discipline that emotions matter. While the first wave of research lamented the discipline’s marginalization of emotions (Bleiker & Hutchison, Citation2008), the second wave has engaged the politics of emotions in numerous realms, from war to diplomacy through terrorism and humanitarian disasters (e.g., Hall, Citation2015, Koschut, Citation2020; Saurette, Citation2006). In all these areas, a turn to emotions provides insights as to why international actors respond the way they do. Embedded in social discourses and everyday practices, emotions shape policy outcomes but may also be triggered by international events, which produce different action tendencies, legitimate policies, and drive political reactions (Koschut, Citation2022). As Ringmar put it (2018: 33), ‘take away the emotions and there will be little international politics left’.

The possibility of assigning emotions beyond individuals to social collectives (i.e., nation-states, international organizations, or transnational groups) has generated disagreements. For sceptics, only individuals can have emotions as only individuals have living bodies (Ross, Citation2006). Conversely, proponents of the theorization of the state as an emotional actor insist that the state is a fully fledged psychological person, able to experience emotions, due to its being an intentional actor, possessing collective consciousness (Wendt, Citation2004). Others argue that a state experiences emotions as it constitutes a group of individuals that identify with each other emotionally (Mercer, Citation2014; Sasley, Citation2011). In sum, ‘states are not gigantic calculating machines; they are hierarchically organized groups of emotional people’ (Hymans, Citation2010, p. 462), including decision-makers, bureaucracies and the wider society.

But what about emotions at the level of international organizations? Initially, it seems counter-intuitive to think of the EU in emotional terms, given its image of a ‘civilized’ body capable of managing its emotions (Linklater, Citation2014, p. 574). The level of analysis debate is challenging, European politics being a multi-level game with influential actors spanning sub-national, national, and supranational levels. Not to mention the fact that the making of EU’s foreign policies involves a long process that may diminish the salience of emotions given their ephemeral nature (Smith, Citation2021). How then is it possible to assign emotions to such a complex institution? At what sites can these emotions be observed and with what effects?

The emotional turn applied to the EU has identified emotions in different EU institutions with significant consequences on EU policies, including the integration process (Palm, Citation2018), internal challenges like the financial crisis and Brexit (Capelos & Katsanidou, Citation2018; Manners, Citation2018), and its foreign policy (Terzi et al., Citation2021). For instance, relying on the emotional convergence mechanism, Smith (Citation2021) shows that emotions facilitated consensus-building in the European Council and Foreign Affairs Council during the 2014 Ukrainian crisis leading to collective action. Others have highlighted how emotion norms or feeling rules (i.e., appropriate emotional expressions) are discursively (re)-constructed by the EU, enabling or constraining policy outcomes (Sanchez Salgado, Citation2023; Terzi et al., Citation2021). The emotion-norm nexus has therefore featured prominently in the study of emotions in EU FP showcasing cases in which EU norms are being violated by a third party triggering emotional responses – anger and empathy, being the most scrutinized ones.

In contrast, we know little about the emotion of fear and its effects in the EU foreign policy context. The only notable exception is the study by Sanchez Salgado (Citation2022) that focused on the diverse array of emotions (i.e., fear, anger and compassion) expressed by European players during the refugee crisis (2015 and 2016–2018). Following her footsteps, we scrutinize the role of fear in the EU policy-making process in the Euro-Mediterranean context over a longer period (1995–2015) to better illustrate the gradual social construction of fear and its institutionalization in the EU migration policy towards the Mediterranean. We demonstrate that the fear – inherent in securitization processes – leads to fearful emotional practices that fundamentally violate EU’s normative commitments (i.e., defence of human rights). Whilst the EU is renowned for its emotions-action gap in FP (i.e., mismatch between emotional rhetoric and the EU’s response) (Smith, Citation2021), our study shows that the emotion-action gap is closing in the case of the EU migration policy towards its Southern Mediterranean neighbours under the influence of fear. We do recognize, however, that fear is not the only emotion expressed in the EU migration policy, empathy being another important emotion behind more balanced migratory policies (Sanchez Salgado, Citation2022). This is in line with recent research on emotions, showing that emotions and cognition do not exist in dichotomy or discontinuity (Damasio, Citation2000; McDermott, Citation2004); hence, any policy option is inevitably associated with certain emotions. Yet given the prevalence of the control-oriented approach in EU migration policy, we have decided to focus our attention to the social construction of fear, its institutionalization, and effects at the EU level.

The social construction of fear through securitization and its impact on migration policy

The conceptual slipperiness and elusive nature of emotions make their definition challenging. Rather than adhering to a pure definitional type, we subscribe to a hybrid approach to emotions, combining their cognitive and social aspects. We understand emotions as thought-ridden judgements rather than bodily states but hold that the social context in which they emerge matter. For cognitivists, ‘most emotions are elicited and differentiated by people’s evaluation of the significance of events for their well-being’ (Lazarus & Lazarus, Citation1994). What matters in this definition of emotion as a feeling associated with the perception that a desire is satisfied or not – is that it motivates subjects to react in a specific way. Importantly, the cognitive interpretations triggering emotions are themselves socially and intersubjectively constructed. Emotions are intrinsically linked to, and imbued within, the discourses and social structures that underpin societies and their politics. Individuals within a culture make appraisals and value judgements according to their past experiences and cultural knowledge (Harré, Citation1986).

On the origins of fear: A socially constructed emotion through securitization

Fear can also be understood through this hybrid cognitive and social constructivist lens. Fear is an emotional reaction to the perception of threat, defined as ‘displeasure about the prospect of an undesirable outcome’ (Barbalet, Citation1998, p. 151). Yet things that individuals fear and how they react to threats are culturally and politically defined (Crawford, Citation2014). While in medieval times, volcanic eruptions and solar eclipses were a source of fear (Furedi, Citation2005), it is today the fear of migrants, viewed as a threat to the economic, physical and even ontological security of European states that prevail (Bigo, Citation2002; Huysmans, Citation2000, Citation2006; Karyotis, Citation2011).

Securitization is one of the most powerful mechanisms through which the social construction of fear occurs, as it attributes the meaning of threat to any phenomenon both through discursive and practical moves. For the Copenhagen School, securitization corresponds to ‘an extreme version of politicization, meaning that an issue is presented as an existential threat, requiring emergency measures and justifying actions outside the normal bounds of political procedures’ (Buzan et al., Citation1998, p. 22). It insists that insecurity is not a fact of nature but must be written and talked into existence. The constitutive power of language follows from the fact that certain discourses carry particular connotations and historical meanings that they impart to social reality. Hence, language has both the capacity to integrate events into a wider network of meanings and to mobilize expectations regarding an event (Huysmans, Citation2006, p. 8).

Applied to migration, such rhetoric helps justify restrictive approaches to controlling migration, derogating from human rights and constitutional provisions. The distinguishing feature of securitization is a rhetorical structure, emphasizing survival, urgency and priority of action (Buzan et al., Citation1998, p. 26). Governments use and abuse numbers to suit their own interests. Statistics are quoted in ways that alarm rather than inform, and numbers are replaced by emotion-laden terms expressing the disproportionate extent of a phenomenon and loss of control, like ‘flood’ and ‘invasion’. These metaphors securitize without articulating how an increase in numbers endangers the existence of the political community (Huysmans, Citation2006, p. 48).

In contrast, the sociological approach to securitization (Balzacq, Citation2010; Bigo, Citation2002) privileges the role of practices. The security practices of bureaucracies and the technologies used contribute more to securitization processes than securitizing speech acts (Huysmans, Citation2004). Securitizing tools are ‘instruments, which by their very nature or functioning transform the entity they process into a threat’ (Balzacq, Citation2008, p. 80). While securitization tools are technical, the reasons they are chosen, how they operate, evolve and their consequences are political. The use of military guards to intercept migrants corresponds to such a securitizing tool, turning migrants into a security threat (Léonard & Kaunert, Citation2022). While analytically it makes sense to differentiate these approaches, in practice most studies engage in a balancing act between practices and discourses of securitization as a result of an increasing cross-fertilization among critical approaches (Balzacq et al., Citation2016, p. 499).

Be it in its discursive or practice-focused version, the securitization literature has neglected the emotional dimension inherent in securitization processes. Echoing Van Rythoven (Citation2015) who refers to the lack of theorization of the relationship between securitization and emotions as a problem of ‘ontological slippage’, we suggest that is the very process of securitization, involving both discursive and practical elements, which contributes to the social construction of the emotion of fear in the first place. We therefore suggest that the very process of securitization is by itself an emotional mechanism leading to the social construction of fear.

Proliferation of securitizing actors as “fear entrepreneurs”

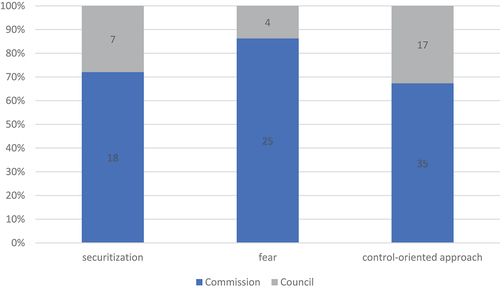

For securitization to be successful, securitizing actors must have the capacity to make socially effective claims about threats. As defenders of the national interest, political leaders are the main securitizing actors (Buzan et al., Citation1998, p. 31). In the EU migration context, the securitization of migration is uploaded from the national to the EU level, permeating EU institutions (Guiraudon, Citation2001; Lavanex, Citation2001). Migration management is a complex institutional undertaking, handled both by the Area of Freedom, Security and Justice and by the Common Foreign and Security Policy (Dimulescu, Citation2011, p. 161). Whilst the European Commission, European Council and European Parliament are all involved in the external dimension of migration (Boswell and Geddes, Citation2011: 62–66), migration policy is mostly dominated by the Member States’ Interior ministers. Through recurrent interactions, EU officials eventually internalize within their own sense-making the constraints of the MS who are reluctant to implement policies in accordance with a comprehensive understanding of migration, entailing a focus on long-term development (Geddes & Hadj-Abdou, Citation2018).

Security professionals act as epistemic communities: harbouring expert knowledge, they make sense of the world based of their self-understanding as those responsible for risk management. As such, they transfer the legitimacy gained from struggles against terrorists and counterfeiters to other targets, including migrants (Bigo, Citation2002, p. 63). FRONTEX, for instance, has supported the introduction of securitizing practices through EU border policing (Léonard & Kaunert, Citation2022).

Yet, the process of fear construction is not linear and follows the securitization of migration through ‘upwards and downwards spiraling’ (Bello, Citation2022). Through de-securitization (i.e., the unmaking of security problems) (Waever, Citation1995), threat perceptions and fear fade away. Desecuritizing actors, such as NGOs counteract the securitizing moves of fear entrepreneurs by offering alternative framings emphasizing refugees’ legal rights to protection and their common humanity (Mezzetti & Ceschi, Citation2015; Sanchez Salgado, Citation2021).

The impact of fear on migration policy: Fearful emotional practices

Fear has its origins in the construction of threat perception through securitization. But how does this impact the decision-making process and resulting policy response? By contrast to realists who equate discourse to cheap talk, proponents of the power of emotions argue that emotions built into the discourse have social effects. It is the socio-psychological link between cognitive and emotional categories that constitutes a motivational resource for collective action and intersubjectivity (Koschut, Citation2018, p. 287). It is therefore crucial to point to what emotions do in terms of stimulating certain behaviour and performances (Koschut, Citation2018, p. 280). Following appraisal theory, emotions shape cognitive predispositions and trigger action tendencies that crystallize in emotional practices.

Emotions change what we look for, what we see and how we think (Crawford, Citation2014). Fear – when excessiveFootnote1- involves uncertainty, a low sense of control, and a perception of negative events as unpredictable. This exacerbated sense of impotence contributes to the flawed perception of being at risk, leading to ‘hypervigilance’. Fearful actors thus feature a diminished risk-taking propensity (Lerner & Keltner, Citation2001; Lerner et al., Citation2015), overestimate the likelihood of negative events and underestimate the likelihood of positive events (Crawford, Citation2014). Engaged in a self-protective response, they prioritize the short rather than the long term, even if it is counterproductive (Crawford, Citation2000, p. 143).

For appraisal theory, the significance of emotions resides in the purposive behaviour they are amenable to prompt (Ariffin, Citation2016, p. 3). Action tendencies are states of action readiness to establish, maintain, or modify relationships (Frijda, Citation2007). In a fight-or-flight situation, the main action tendency is the neutralization of danger or threat removal. If the threat has a concrete referent object, then making the source of danger disappear or keeping it away is the priority (Frijda, Citation2007). Eventually, cognitive predispositions and related action tendencies influence the decision-making process by crystallizing in emotional fearful practices. If practices are ‘socially meaningful patterns of action, which in being performed, simultaneously embody, act and possibly reify our background knowledge and discourse in and on the material world’ (Adler & Pouliot, Citation2011, p. 4), then emotional fearful practices are performances resulting from, and cultivating the emotion of fear, manifesting a reflex of closure, overprotection, and rejection (Halperin & Pliskin, Citation2015). Granted, fear is often narrowly understood as a spontaneous and short-lived emotion in response to a specific event (Scherer, Citation2005). Yet emotions can be turned into an affective disposition and become institutionalized, implying that the action tendencies related to the emotion and the connected emotional practices become taken for granted (Crawford, Citation2014).

In short, the more fearful an actor is, the more risk-averse it will become, privileging precautionary policies having a direct impact on security threats. We therefore expect that the more securitizing indicators appear, the more fear is cultivated and emotional fearful practices likely to develop. The reluctance to take risks in migration management is translated into fearful emotional practices in the form of the externalization of control (‘to keep the source of the danger away’) and readmission agreements (‘to remove the threat’) (see ).

Uncovering the emotional dimension of EU migration policy towards the Mediterranean

Given our conceptualization of emotions as socially constructed phenomena, we focus on the representational and intersubjective communication of emotions within social spheres (Bleiker & Hutchison, Citation2008). EDA is thus the most suited approach to uncover the discursive articulation of cognition, affective arousals and action tendencies, impacting social behaviour (Koschut, Citation2018).

The first step of EDA consists of selecting appropriate texts across a coherent period. We collected twenty-eight EU documents (472 pages) (including Euro-Mediterranean agreements, European Commission’s communications, European Council resolutions and press releases) outlining the EU migration policy in the Euro-Mediterranean context over twenty years (from 1995 marking the launch of the EMP until 2016). We included in the analysis official documents whose primary focus is migration in relation to the European neighbourhood as well as documents related to Euro-Mediterranean policies with particular attention given to the migration section. These documents result from a contestation process among various actors shaping migration policy at the EU level (i.e., governmental and EU officials, NGOs, and EU agencies like Frontex, corresponding to both fear entrepreneurs and desecuritizing actors). While these actors may experience different fears in terms of authenticity and objects (Sanchez Salgado, Citation2021), we look here at the EU policy ultimately put forward by EU officials. Considering the EU as an aggregate actor, we seek to highlight how the securitization of migration, fear and the enactment of emotional fearful practices are intertwined at the EU level.

The following step of EDA consists in mapping emotions within texts. The aim is to analytically separate the descriptive meaning of words from their connotative emotional meaning (Abu-Lughod & Lutz, Citation1990, p. 5). Therefore, attention is given to linguistic features expressing emotions, like emotion terms, connotations, metaphors, comparisons, and analogies. The key here is the fact that certain words are affectively ‘loaded’ in the sense that their semantic utterance is linked to emotional meaning. For instance, affective terms – e.g., terrorist and genocide – carry a negative appeal because they refer indirectly to emotion concepts of disapproval, like anger, contempt or hate (Koschut, Citation2018, p. 284). Similarly, the words used to securitize migration, such as threat, risk, terrorist – implicitly refer to the emotion of fear.Footnote2 Hence, by contrast to frame and securitization analysis, EDA sheds light on the hidden emotional component of the process and therefore has the merit of making the assumed emotional meanings of relevant textual components more explicit to the reader than conventional discourse analysis.Footnote3

The third step of EDA states how emotional expressions have implications for social behaviour (Koschut, Citation2018, p. 294). As shown in , we focus on the EU’s policy measures and justification thereof – encapsulating the cognitive predispositions and action tendencies related to the given emotion (i.e., fear). EDA therefore helps reveal the link between securitization (as a security frame), its inherent emotional dimension (i.e., fear) and resulting emotional fearful practices. Secondary sources on the implementation of EU policies (e.g., FRONTEX activities) are also included to illustrate the unfolding fearful emotional practices.

Table 1. Operationalization of the theoretical framework.

Importantly, as any research method, EDA entails limitations. EDA does not work like an ‘emotional x-ray machines’ (Wilce, Citation2009, p. 35) and as such, does not allow to determine whether actors are truly experiencing fear. It claims no access to the inner emotional world of human beings but targets their intersubjective expression and collective representation (Koschut, Citation2018, p. 296). To compensate for this limitation, we incorporated insights from similar studies based on interviews. Geddes and Hadj-Abdou’s (Citation2018) shows that EU officials involved in the migration governance system internalize within their own sense-making the constraints as they see them imposed by domestic politics in MS. In the backdrop of anti-immigration sentiment and Euroscepticism, EU elite actors consider the fear of migrants constructed at the national levels, let it permeate the EU institutions and shape the institutional response to migration. Rather than being fearful of migrants, EU officials are most probably afraid of the fear of others (i.e., they fear European citizens’ and politicians’ fear of migrants and the associated rise of populism) and seek therefore to respond to their fears by institutionalizing fear in their own policy making.

The EMP: When normative power Europe was fearless

The EMP and its normative-comprehensive nature serve as benchmark to assess the evolution of the EU migration policy towards the Mediterranean. Launched in 1995, it forged a partnership between the then fifteen EU member states and twelve Mediterranean partner countries (MPCs), advancing the vision of a secure, stable, and peaceful Euro-Mediterranean space (European Union, Citation1995). This initiative reflected well the post-cold war Zeitgeist: more concerned by the weakness of their Southern neighbours than the strength of their adversaries in the East, European countries prioritized multilateralist comprehensive approaches to transnational problems (Boswell, Citation2003, p. 626; Jünemann, Citation2004, p. 5). The EMP’s value emanated from its normative dimension commensurate to the EU’s ambition to be a ‘force for good’ in the world (Smith, Citation2002). At its core laid a region-building logic aimed at achieving security through normative spillover and functionalist effects from the ‘inside of the EU to the outside of its borders’. Regional security was to be achieved through the dismantling of the political and socioeconomic causes of instability in the MPCs. Therefore, conditionality clauses were inserted into the Association Agreements, linking economic co-operation to institutional reforms, good governance and respect for human rights (Jünemann, Citation2004).

Migratory pressures were neither considered as a high priority issue nor as a security threat but rather as a problem whose root causes could be tackled through a comprehensive approach. In line with the region-building logic, the migration-development nexus prevailed: development assistance, trade and foreign direct investments were supposed to improve growth prospects and contribute to job creation in the MPCs (EU, Citation1995). The discourse recurrently captured the EU and MPCs ‘common wish to intensify the dialogue and co-operation on migration and human exchanges’ (European Union, Citation1997, Citation1998). The chain of connotations linking ‘migration’, ‘human exchanges’, and their emotional positive meaning contrasts with the fearful connotations associating migration to terrorism that will prevail down the line.

Back then, these long-term policy prescriptions were the preferred path because of the absence of securitization processes and related fear at the EU level (see in the appendix). Despite the prospect of continued migration flows as illustrated in this quote- ‘it is unlikely that in the short or medium term there will be a decrease in factors encouraging migration from the Southern Mediterranean basin to Europe’, EU officials favoured a comprehensive approach, considering migration as a ‘normal expressions of our integrating societies’ and recognizing ‘the need to examine the legitimate needs of Euro-Mediterranean partners, with regard to temporary forms of migration’ (European Union, Citation1999). Without having to deal with the fear of migrants conveyed by Member States, EU officials believed in the possibility of stemming migration by improving living standards for potential migrants. Importantly, migration experts and economists, who saw migration issues through the development lens, significantly contributed to high-level meetings in this period (European Union, Citation1999). Undaunted, the EU thus pursued this long-term strategy designed to alleviate push factors in origin countries even though it was considered riskier due to the migration hump and the uncertainty concerning the MPC’s performance in using development aid effectively (Boswell, Citation2003, p. 636).

The ENP: When fear creeps into the EU

While the ENP is often presented against the backdrop of the 2004 EU enlargement, its policy-formation process proceeded from 2001 in the 9/11 context and the ensuing ‘war on terrorism’ (Pace, Citation2007, p. 661). This partly explains why the ENP’s normative ambition to promote EU values has been overshadowed by security concerns. Securitization markers started appearing in the discourse, concomitantly creating fear, and leading to the adoption of exclusionary emotional practices. While the first explicit discursive securitizating move (linking under the same sub-heading the fight against organized crime, terrorism and cooperation on migration) appeared in the Presidency Conclusions of the Vth Euro-Mediterranean Conference of Foreign Ministers in Valencia back in April 2002, it became systematically embedded in the following statements – particularly so in the Commission proposals (see in appendix).

Originally, the ENP aspired to bolster the EU’s image as a ‘force for good’ while tackling common security issues with neighbouring countries (European Commission, Citation2004). Both the Union and ENP partners were supposed to benefit from the institutionalization of the external dimension of JHA, including migration management. The EU committed to offer assistance to enhance ENP partners’ border control capacity; support for reforms in judicial independence, police training and corruption reduction; and steps towards liberalizing the Schengen visa regime and facilitating travel to the EU (Barbé & Johansson-Nogués, Citation2008, p. 86). For EU Commissioner Ferrero-Waldner (Citation2006), these measures represented ‘a comprehensive and balanced approach, managing legal immigration while preventing and fighting illegal immigration […]’.

Despite this ambition, the EU discourse is replete with fearful markers associated with the threat construction inherent in securitization processes. The emphasis on illegal migration as of ‘key importance’ or ‘key issue’ (EC, Citation2004) creates a sense of urgency, instilling fear. The framing of migration as a ‘threat to mutual security’ and its discursive linkage to ‘environmental nuclear hazards, communicable diseases, human trafficking, organized crime, or terrorist networks’ (European Commission, Citation2003) equally generates fear through negative connotations. Even the facilitation of legal migration is discursively associated with security threats: ‘The EU is looking at ways of facilitating the crossing of external borders for bona fide third-country nationals living in the border areas that have legitimate and valid grounds for regularly crossing the border and do not pose any security threat’ (European Commission, Citation2003). This seemingly technical language is highly emotional, as it cultivates the perception of a dangerous environment in which vigilance is required towards ill-intentioned migrants.

In parallel, the prescription of fearful emotional practices, encapsulating the cognitive predispositions and action tendencies of fearful actors is striking. The preference for the short-term is reflected in the focus on illegal migration and border management at the detriment of legal migration. From the onset, the EU had envisioned that ‘border management was likely to be the priority in most Action Plans’ (European Commission, Citation2004), the goal being ‘to facilitate movement of persons, whilst maintaining or improving a high level of security’ (EC, Citation2004). The idea of protection implicitly carries the connotative emotional meaning of fear. Subsequently, problems warranting long-term investment were side-lined: ‘promoting the successful integration of migrants in any country is necessary but requires time and understanding’ (EC, Citation2004). Taking stock of the ENP, the EC unsurprisingly noticed, that ‘although co-operation with ENP countries on mobility and migration management is growing, the ENP has not yet allowed significant progress on improving the movement of partner country citizens to the EU’ (European Commission, Citation2006).

The second fearful emotional practice consists in keeping the perceived danger away through the externalization of migration control. Recognizing the difficulty of expelling migrants already on European territory because of the legal protection they enjoy, the remote-control approach policies external borders at a distance to ensure prospective migrants are sorted before their arrival (Lavanex, Citation2006). This approach involves the transfer of know-how and surveillance technologies to improve border management in third countries. Instead of aid programs and employment schemes, the EU privileges securitization tools (Balzacq, Citation2008, p. 79), most notably the militarization of migration control by deploying military forces and hardware to prevent migration by sea under the MS impulse (Lütterbeck, Citation2006).

Readmission agreements constitute another fearful emotional practice, designed to incentivize third countries to take migrants back (‘threat removal’). MPCs are co-opted into the ‘gendarmes of Europe’ in exchange for visa facilitation to the EU. Readmission agreements commit MPCs to take back not only those of their nationals in an unregulated situation within EU territory, but also all transiting persons originating in countries with which the EU does not have readmission agreements (Barbé & Johansson-Nogués, Citation2008, p. 90). These asymmetrical terms indicate the EU’s unwillingness to encourage legal migration and its departure from a comprehensive approach that reckons with the detrimental consequences of its policy on its partners’ economic situation. Readmission agreements further contradict the EU’s normative ambition, as migrants are being returned to countries with poor human rights records and inadequate refugee protection, which jeopardize both migrants’ rights and security (Mountz & Williams, Citation2016).

Eu’s migration policy post-Arab Spring: When fear is institutionalized

The political upheavals that started in early 2011 in North Africa and the unforeseen demise of regimes in Tunisia and Libya have had immediate repercussions across the region. The Arab Spring and the ensuing refugee crises challenged the EU migration regime and its professed value system. Policy-wise, the EU’s immediate response was the creation of ‘Dialogues for Migration, Mobility and Security with the Southern Mediterranean countries’ in line with the ‘Global Approach to Migration and Mobility’ (European Commission, Citation2011a). Despite the re-introduction of elements reminiscent of the comprehensive approach, the fearful discourse on migration and the reinforcement of emotional fearful practices persisted and significantly increased (see in the Appendix).

The analysis indicates that the securitization of migration has been spiralling upwards – simultaneously amounting to the discursive profusion of fearful markers. The Commission underlined that ‘EUROPOL has deployed a team of experts in Italy, to help its law enforcement authorities to identify possible criminals among the irregular migrants having reached the Italian territory’ (European Commission, Citation2011a), linking migration with criminality. Chains of equivalence associating migration, criminality and terrorism were introduced, even though EU officials acknowledged that ‘migration and terrorism were amalgamated too quickly’ and that they could not be ‘sure whether there are actual links between terrorism and migrant trafficking’ (Ivashenko-Stadnik et al., Citation2017, p. 29). Yet the corresponding security-oriented policy response was put forward – demonstrating another instance of over-reaction. Moreover, the flawed perception of a trade-off between enhanced mobility and security risks has been further cultivated along with the associated emotion of fear: ‘the EU should ensure that the need for enhanced mobility does not undermine the security of the Union’s external borders’ (European Commission, Citation2011a). Discursive moves based on alarmist estimations conveyed a sense of immediate and overwhelming threat, fostering fear: ‘massive flows of illegal migrants and to a limited extent, of persons in need of international protection’, and ‘thousands of people that have recently sought to come to the EU, are putting the protection and reception systems of our Member states under increasing strain’ (European Commission, Citation2011a). At that time, FRONTEX – as a fear entrepreneur – assessed that 500,000 migrants would cross the Mediterranean. Yet only 28,000 illegal migrants from Tunisia and Libya arrived in Europe, while 600,000 persons left Libya to Tunisia and Egypt dispelling the myth of a ‘biblical invasion’ (Economist, Citation2011). Despite this reality check, the Council called on FRONTEX ‘to continue to monitor the situation and prepare detailed risk analyses on possible scenarios’ (European Council, Citation2011b), displaying the fearful actor’s propensity to overestimate the likelihood of negative events.

The discourse conveys a sense of vulnerability, implicitly associated with the emotion of fear. Terms, like ‘a period of profound uncertainty’, ‘the vulnerability, the weaknesses of certain sections of the EU’s external border’, or the report that ‘the magnitude of the problem exceeds the existing facilities of the most exposed Member states’ express a lack of control over the events and hence fear (European Commission, Citation2011a). Resorting to more explicit emotionally loaded terms, the Commission argued that ‘citizens need(ed) to feel reassured that external border controls are working properly’ (European Commission, Citation2011b).

Against this emotional background, existing fearful practices reflecting action tendencies related to fear were reinforced, including the remote-control approach boosting border management co-operation with third countries (European Council, Citation2011b) and promoting the extraterritorial dimension of refugee protection (European Council, Citation2011a). This reflex of closure also introduced upgraded securitization instruments: as a ‘matter of priority’, EU external borders must become ‘smart borders’ equipped with new technologies (European Council, Citation2011a). Emblematic of the creeping militarization of migration policy, the European Border Surveillance System is the most ambitious example of such ‘smart remote control initiatives’ led by the EU to support Member States (Zaiotti, Citation2016). Finally, the fearful emotional practice consisting in ‘sending migrants back’ through readmission agreements re-gained momentum. The ‘EU-Turkey statement’ – whose authorship has legally been disputed – addressed migration from Turkey to the Greek Islands by allowing Greece to return to Turkey irregular migrants arriving after 20 March 2016. In exchange, EU Member States committed to increase resettlement of Syrian refugees in Europe, accelerate visa liberalization for Turkish nationals, and boost financial support for Turkey’s refugee population (European Council, Citation2016). UndeterredFootnote4 by severe shortcomings in the protection of HR in sending countries, the European Council signed a similar declaration with Libya to intercept migrants and return them to detention centres (European Council, Citation2017); a move condemned by UN High Commissioner for Human Rights for whom: ‘the EU’s policy of assisting the Libyan coastguard to intercept and return migrants in the Mediterranean [is] inhumane’ (UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, Citation2017).

The EU’s awareness of its over-emotionality

Acknowledging the over-emotionality surrounding migration, EU leaders have called to rectify EU migration policy in line with EU’s values. European Commissioner Ferrero-Waldner (Citation2006) recognized that migration is presented in simplistic, sensational terms, which do no justice to the complex factors behind it. … In uncertain times, when the forces of globalisation seem to be sweeping all in their path, it is understandable that our citizens are worried about employment and increased competition for jobs. But the prevailing view of migration is, unfortunately, based more on emotion than on fact. While one could argue that this criticism is first and foremost directed at the national governments and their citizens, there is no doubt that it also applies to the EU policy itself, akin to a lesson learnt: ‘In the last few years, we have developed a clearer understanding of migration, and of the policy we should implement. We need to move away from an approach which aims to reduce migratory pressures on the EU by keeping migrants out. (…) Fortress Europe is no longer an option’ (Ferrero-Waldner, Citation2006). Subsequently, the EC called to return to a more ‘rational’ and ‘balanced’ migration policy (EC, Citation2011a), by ‘deepening and refining the work on migration and development’ and emphasizing ‘the human dimension of migration and development policies’ (EC, Citation2011a).

Yet the control-oriented approach kept prevailing. The institutionalization of fear at the EU level has rendered the uprooting of emotional fearful practices challenging. Realizing that a less fearful migration policy entailed more channels for legal migration, ‘mobility partnerships’ were introduced as the cornerstone of the new dialogue between the EU and its partners in the ‘Renewed ENP’ framework. These were supposed ‘to bring together all the measures, which ensure that mobility is mutually beneficial’ (EC, Citation2011a). Despite this claim to novelty, the terms of co-operation remained the same: increased mobility via visa facilitation has been conditioned upon voluntary-return arrangements, the conclusion of readmission agreements, working arrangements with FRONTEX, and co-operation in the joint surveillance of the Mediterranean (EC, Citation2011a) – all these corresponding to institutionalized fearful emotional practices.

Similarly, the ‘EU’s Migration Partnership Framework’ (European Commission, Citation2020) has also strived to ‘sustainably manage migration flows’. Yet again, European governments and the EU have had difficulty developing new responses by making more effective links between migration, development, and trade policies (Geddes & Hadj-Abdou, Citation2018, p. 143). For Castillejo (Citation2017, p. 6), the MPF represents the most openly interest-driven EU’s migration initiatives, promoting short-term security goals and appearing furthest removed from principles of genuine partnership and protection of human rights, pointing to the persistence of fear at the EU level.

Conclusion

This article has uncovered the emotional dimension of the EU migration policy towards its Mediterranean neighbours. To explain the shift from a comprehensive to a control-oriented approach, we suggested that the socially constructed fear of migrants through securitization has led to the adoption of exclusionary emotional practices at the EU level. The externalization of migration control corresponds to exclusionary emotional practices, embodying the cognitive predispositions and action tendencies of a fearful actor. Urged to keep the source of danger away, the EU became risk-averse, prioritized the short over the long-term and eventually fenced itself off.

Moving beyond instances in which the EU responds emotionally to the violations of its norms by a third party, we showed that the EU may experience negative emotions that undermine its own norms. Despite the EU’s awareness of its emotionality and attempts to re-balance its migration policy, it keeps contributing to the securitization of migration by allowing the uploading of securitization from the national to the EU level, fuelling and institutionalizing fear. This process does not only stain the EU’s image as a normative power but also works to the detriment of refugee-protection concerns and constructive co-operation with third countries.

These insights can explain similar dynamics in other regions where the securitization of migration has led to unintended consequences, both in liberal democracies traditionally committed to human rights, like in the US, Canada, and Australia, but also beyond as in Asia (Curley et al., Citation2008; Watson, Citation2009). While the social construction of fear through securitization may vary due to different cultural contexts, the (universal) response to fear through the enactment of fearful practices arguably remains valid across geographical areas. More doubts persist regarding the applicability of the framework to other securitized issues (like the environment and climate change), which feature distinctive characteristics entailing a different security logic – and hence arguably different emotional fearful practices (Balzacq et al., Citation2016).

Going forward, the empirical scope of the study could be expanded considering the recent refugee crisis triggered by the Russia–Ukraine war and the remarkable turnaround in the European response. Similarly, the latest EU initiative ‘A New Agenda for the Mediterranean’ (European Commission, Citation2021) seems to re-prioritize inclusive socio-economic development, even though the visa facilitation/readmission agreement double-track approach characterizing the ENP remains untouched. Finally, it might be worth exploring the link between the institutionalization of fear in EUFP policy and the ensuing external perceptions of the EU. To what extent is the EU’s fearful response to migration seen as a sign of weakness, contributing to the ‘weaponization of migration’ by Turkey, Belorussia, Libya and potentially others? This question is all the more relevant as migration is expected to remain a key phenomenon of our turbulent times – both in the EU backyard and beyond.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. While fear can be a constructive force to overcome difficulties and ensure survival, we focus on excessive levels of fear and its negative effects, damaging one’s capacity to interact with the world (Moïsi, Citation2009, p. 155).

2. We refer to threat and risk interchangeably, as both terms are connotated negatively and associated with fear. Yet, a distinction exists in the literature between a threat as ‘a person or thing likely to cause harm’ and ‘risk’ which defines the ‘likelihood that something unpleasant or unwelcome will happen’ and ‘the consequence of that harm’ (see for instance Strachan-Morris, Citation2012).

3. For a discussion on the distinction between framing and securitization analysis and their combination, see Rychnovska (Citation2014); Watson (Citation2012).

4. For an in-depth legal discussion about the pseudo-authorship of the EU-Turkey statement, see Hillary (Citation2021).

References

- Abu-Lughod, L., & Lutz, C. A. (1990). Introduction. In C. A. Lutz & L. Abu-Lughod (Eds.), Language and the Politics of Emotions (pp. 1–23). Cambridge University Press.

- Adler, E., & Pouliot, V. (2011). International practices. International Theory, 3(1), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1017/S175297191000031X

- Ariffin, Y. (2016). Introduction: How emotions can explain outcomes in International relations. In Y. Ariffin, J. Coicaud, & V. Popovski (Eds.), Emotions in International Politics: Beyond mainstream International relations Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781316286838

- Balzacq, T. (2008). The external dimension of EU justice and home Affairs: Tools, processes, outcomes. SSRN Electronic Journal, Available at. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1337009

- Balzacq, T. (2010). Constructivism and securitization Studies. In M. D. Cavelty & V. Mauer (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of security studies (pp. 72–88). Routledge.

- Balzacq, T., Léonard, S., & Ruzicka, J. (2016). Securitization revisited: Theory and cases. International Relations, 30(4), 494–531. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047117815596590

- Barbalet, J. M. (1998). Emotion, social Theory and social structure: A macrosociological approach. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511488740

- Barbé, E., & Johansson-Nogués, E. (2008). The EU as a modest ‘force for good’: The European Neighborhood policy. International Affairs, 84(1), 81–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2346.2008.00690.x

- Bello, V. (2022). The spiralling of the securitisation of migration in the EU: From the management of a ‘crisis’ to a governance of human mobility? Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 48(6), 1327–1344. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1851464

- Bigo, D. (2002). Security and immigration: Toward a critique of the governmentality of unease. Alternatives: Global, Local, Political, 27(1_suppl), 63–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/03043754020270S105

- Bleiker, R., & Hutchison, E. (2008). Fear no more: Emotions and world Politics. Review of International Studies, 34(S1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210508007821

- Boswell, C. (2003). The external dimension of EU immigration and asylum policy. International Affairs, 79(3), 619–638. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.00326

- Boswell, C., & Geddes, A. (2011). Migration and mobility in the European Union. European Union Series (Palgrave Macmillan).

- Buzan, B., Waever, O., & De Wilde, J. (1998). Security: A New framework of analysis. Lynne Rienner Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781685853808

- Capelos, T., & Katsanidou, A. (2018). Reactionary Politics: Explaining the psychological Roots of ‘Anti’ preferences in European integration and immigration Debates. Political Psychology, 39(6), 1273–1290. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12540

- Cassarino, J. P., & Lavanex, S. (2012). EU migration governance in the Mediterranean region: The promise of (a balanced) Partnership?. IEMed Mediterranean Yearbook.

- Castillejo, C. (2017). The EU migration Partnership framework: Time for a rethink? Discussion Paper, No. 28/2017, Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), available at: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/199518/1/die-dp-2017-28.pdf

- Crawford, N. C. (2000). The passion of world Politics: Propositions on emotion and emotional relationship. International Security, 24(4), 116–156. https://doi.org/10.1162/016228800560327

- Crawford, N. C. (2014). Institutionalizing passion in world Politics: Fear and empathy. International Theory, 6(3), 535–557. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1752971914000256

- Curley, M., & Wong, S. L. (2008). Security and migration in Asia: The Dynamics of securitization. ( M. Curley & S.L. Wong Eds.) Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203934722

- Damasio, A. (2000). The feeling of what happens: Body, emotions and the making of consciousness. Vintage.

- Dimulescu, V. (2011). Migrants at the gates: The external dimension of the EU’s migration policy in the South Mediterranean. Interdisciplinary Political Studies, 1(2), 161–165.

- Economist. (2011). Fear of foreigners. 3 March, www.economist.com/node/18285932 (Retrieved June 11, 2023).

- European Commission. (2003). “Communication on wider Europe- Neighborhood: A New framework for relations with our Southern and eastern neighbors” COM(2003)104 final.

- European Commission. (2004). “European Neighborhood policy strategy Paper” COM(2004)373 final.

- European Commission. (2006). “Communication on strengthening the European neighbourhood” COM(2006)726 final.

- European Commission. (2011a). “Communication on a dialogue for migration, mobility and security with the Southern Mediterranean countries” COM(2011)292 3.

- European Commission. (2011b). “Communication on migration” COM(2011)248 final.

- European Commission. (2020). “Communication on a New pact on migration and asylum” COM(2020)609 final.

- European Commission. (2021). “Joint Communication with the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and security policy - renewed Partnership with the Southern Mediterranean“ JOIN (2021)2 final.

- European Council. (2011a). “Conclusions of the European Council” ( EUCO 23/11)

- European Council. (2011b). “Extraordinary Council of European Union Declaration” ( EUCO 7/1/11).

- European Council. (2016). “EU-Turkey statement”, Press release, 18 March 2016.

- European Council. (2017). “Malta Declaration on the external aspects of migration: Addressing the Central Mediterranean route”, Statement and remarks3-February.

- European Union. (1995). “Declaration of the Barcelona Euro-Mediterranean Conference”, 27-28 November.

- European Union. (1997). “Conclusions of the Second Euro-Mediterranean Ministerial Conference”, Malta, 15 April.

- European Union. (1998). “Concluding statementEuromed ad hoc ministerial meeting”, Palermo, 3-4 June.

- European Union. (1999). “Experts meeting in the field of migration and human exchange in the Euro-Mediterranean region” Social, Cultural and Human Affairs. The Hague, 1st March.

- Ferrero-Waldner, B. (2006). “Migration, external relations and the ENP”, Speech at the Conference on ‘Reinforcing the area of freedom, security, prosperity and justice of the EU and its neighboring countries’, Brussels, 24 January.

- Frijda, N. (2007). The laws of emotion. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Furedi, F. (2005). Politics of fear: Beyond left and right. Continuum International Publishing Group.

- Geddes, A., & Hadj-Abdou, L. (2018). Changing the path? EU migration governance after the Arab Spring. Mediterranean Politics, 23(1), 142–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2017.1358904

- Gerring, J. (2007). Case study research: Principles and practices. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511803123

- Guiraudon, V. (2001). Seeking New venues: The europeanization of migration-related policies. Swiss Political Science Review, 7(3), 101–107.

- Hall, T. H. (2015). Emotional diplomacy - official emotion on the International stage. Cornell University Press. https://doi.org/10.7591/9781501701139

- Halperin, E., & Pliskin, R. (2015). Emotions and emotion Regulation in intractable conflict: Studying emotional processes within a unique context. Political Psychology, 36(1), 119–150. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12236

- Harré, R. (1986). The social construction of emotions. Blackwell.

- Hillary, L. (2021). Down the drain with General principles of EU Law? The EU-Turkey deal and ‘pseudo-authorship’. European Journal of Migration and Law, 23(2), 127–151. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718166-12340097

- Huysmans, J. (2000). The European Union and the securitization of migration. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 38(5), 751–777. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5965.00263

- Huysmans, J. (2004). A foucaultian view on spill-over: Freedom and security in the EU. Journal of International Relations and Development, 7(3), 294–318. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jird.1800018

- Huysmans, J. (2006). The Politics of insecurity: Fear, migration and asylum in the EU. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203008690

- Hyde Price, A. (2008). A ‘tragic actor’? A realist perspective on ‘ethical power Europe. International Affairs, 84(1), 29–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2346.2008.00687.x

- Hymans, J. E. (2010). The arrival of psychological constructivism. International Theory, 2(3), 461–467. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1752971910000199

- Ivashenko-Stadnik, K., Petrov, R., Raineri, L., Rieker, P., Russo, A., & Strazzari, F. (2017) How the EU is facing crises in its neighbourhood: Evidence from Libya and Ukraine’ EUNPACK Working Paper D.6.1.

- Jeffery, R. (2012). Reason and emotion in International Politics. Cambridge University Press.

- Jünemann, A. (2004). Security-building in the Mediterranean after September 11. In A. Jünemann (Ed.), The euro-med relations after 11 September Frank Cass. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203498729

- Karyotis, G. (2011). The fallacy of securitization of migration: Elite rationality and unintended consequences. In G. Lazaridis (Ed.), Security, insecurity and migration in Europe (pp. 13–30). Ashgate.

- Koschut, S. (2018). Speaking from the heart: Emotion discourse analysis in International relations. In M. Clément & E. Sanger (Eds.), Researching emotions in international relations: Methodological perspectives on the Emotional Turn (pp. 277–301). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-65575-8_12

- Koschut, S. (2020). The power of emotions in world politics. Routledge.

- Koschut, S. (2022). Emotions and International relations. Oxford Research Encyclopedias, International Studies, April, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190846626.013.693

- Lavanex, S. (2001). The europeanization of refugee policies: Normative challenges and institutional legacies. Journal of Common Market Studies, 39(5), 851–874. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5965.00334

- Lavanex, S. (2006). Shifting up and out: The Foreign policy of European immigration control. West European Politics, 29(2), 329–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380500512684

- Lazarus, R. S., & Lazarus, B. N. (1994). Passion and reason: Making sense of our emotions. Oxford University Press.

- Léonard, S., & Kaunert, C. (2022). The securitisation of migration in the EU: Frontex and its evolving security practices. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 48(6), 1417–1429. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1851469

- Lerner, J., & Keltner, D. (2001). Fear, anger and risk. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 8(1), 146–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.81.1.146

- Lerner, J., Ye, L., Valdesolo, P., & Kassam, K. (2015). Emotion and decision making. Annual Review of Psychology, 66(1), 799–823. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115043

- Linklater, A. (2014). Anger and world Politics: How collective emotions shift over time. International Theory, 6(3), 574–578. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1752971914000293

- Lutterbeck, D. (2006). Policing migration in the Mediterranean. Mediterranean Politics, 11(1), 59–82. https:///doi.org/10.1080/13629390500490411

- Manners, I. (2002). Normative power Europe’: A contradiction in terms? Journal of Common Market Studies, 40(2), 235–258. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5965.00353

- Manners, I. (2018). Political Psychology of European integration: The (re)production of identity and difference in the brexit debate. Political Psychology, 39(6), 1213–1232. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12545

- McDermott, R. (2004). The feelings of rationality: The meaning of neuroscientific advances for political sciences. Perspectives on Politics, 2(4), 691–706. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592704040459

- Mercer, J. (2014). Feeling like a state: Social emotion and identity. International Theory, 6(3), 515–535. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1752971914000244

- Mezzetti, P., & Ceschi, S. (2015). Transnational policy networks in the migration field: A challenge for the EU. Contemporary Politics, 21(3), 323–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2015.1061243

- Moïsi, D. (2009). The Geopolitics of emotions - how cultures of fear, humiliation, and hope are reshaping the world. Doubleday.

- Mountz, A., & Williams, K. (2016). Rising tide: Analyzing the relationship between remote control policies on migrants and boat losses. In R. Zaiotti (Ed.), Externalizing migration management: Europe, North America and the spread of “remote control” practices (pp. 31–49). Routledge.

- Noutcheva, G. (2015). Institutional governance of European Neighborhood policy in the wake of the Arab Spring. Journal of European Integration, 37(1), 19–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2014.975987

- Pace, M. (2007). Norm shifting from EMP to ENP: The EU as a norm Entrepreneur in the south? Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 20(4), 659–675. https://doi.org/10.1080/09557570701680704

- Pace, M., & Bilgic, A. (2018). Trauma, emotions, and memory in world Politics: The case of the European Union’s Foreign policy in the middle East Conflict. Political Psychology, 39(3), 503–517. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12459

- Palm, T. (2018). Interwar blueprints for Europe: Emotions, experience and expectation. Politics & Governance, 6(4), 135–143.

- QSR International. 1999. Nvivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software (version 12). https://qsrinternational.com/nvivo/nvivo-priducts/

- Ross, A. (2006). Coming in from the cold: Constructivism and emotions. European Journal of International Relations, 12(2), 197–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066106064507

- Rychnovska, D. (2014). Securitization and the power of threat framing. Perspectives, 22(2), 9–31.

- Sanchez Salgado, R. (2021). Emotions in European parliamentary debates: Passionate speakers or un-emotional gentlemen? Comparative European Politics, 19(4), 509–533. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-021-00244-7

- Sanchez Salgado, R. (2022). Emotions in the European Union’s decision-making: The reform of the Dublin System in the context of the refugee crisis. Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research, 35(1), 14–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/13511610.2021.1968355

- Sanchez Salgado, R. (2023). Uncovering power dynamics: Feeling rules in European policy-making. Journal of Common Market Studies, 62(2), 526–544. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13387

- Sasley, B. E. (2011). Theorizing states’ emotions. International Studies Review, 13(3), 452–476. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2486.2011.01049.x

- Saurette, P. (2006). You dissin me? Humiliation and post 9/11 Global Politics. Review of International Studies, 32(3), 495–522. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210506007133

- Scherer, K. R. (2005). What are emotions? And how can they be measured? Social Science Information, 44(4), 695–729. https://doi.org/10.1177/0539018405058216

- Smith, K. E. (2002). European Foreign policy: What it is and what it does. Pluto Press.

- Smith, K. E. (2021). Emotions and EU Foreign policy. International Affairs, 97(2), 287–304. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiaa218

- Strachan-Morris, D. (2012). Threat and risk: What is the difference and why does it matter? Intelligence & National Security, 27(2), 172–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/02684527.2012.661641

- Terzi, O., Palm, T., & Gürkan, S. (2021). Introduction: Emotion(al) norms in EUropean Foreign policy. Global Affairs, 7(2), 93–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/23340460.2021.1953394

- UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. (2017) “UN HR chief: Suffering of migrants in Libya outrage to conscience of humanity.” https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2017/11/un-human-rights-chief-suffering-migrants-libya-outrage-conscience-humanity?LangID=E&NewsID=22393 (July 12, 2022).

- Van Rythoven, E. (2015). Learning to feel, learning to fear? Emotions, Imaginaries, and limits in the Politics of securitization. Security Dialogue, 46(5), 458–475. https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010615574766

- Waever, O. (1995). Securitization and desecuritization. In R. Lipschutz (Ed.), On security (pp. 46–87). Columbia University Press.

- Watson, S. (2009). The securitization of humanitarian migration: Digging Moats and sinking boats. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203876794

- Watson, S. (2012). Framing’ the Copenhagen School: Integrating the literature on threat construction. Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 40(2), 279–301. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305829811425889

- Wendt, A. (2004). The state as a person in International Theory. Review of International Studies, 30(2), 289–316. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210504006084

- Wilce, J. M. (2009). Language and emotion. Cambridge University Press.

- Zaiotti, R. (2016). Mapping remote control: The externalization of migration management in the 21st Century. In R. Zaiotti (Ed.), Externalizing migration management: Europe, North America and the spread of “remote control” practices (pp. 3–30). Routledge.

Appendix

Table A1. List of EU official documents included in the analysis.

Figure A1. References coded for securitization, fear and control-oriented approach to migration by institution.

Figure A3. Evolution of securitization, fear and control-oriented approach over time (according to three distinct periods).