ABSTRACT

This brief report reviews some recent research on the politics of sea migration at the Southern European border, and in particular Italy, with two primary objectives. First, I seek to briefly illustrate how public attitudes towards migrants at sea in this region are neither monolithic nor unconditionally concentrated in certain areas; rather, public reactions correspond to a combination of emotional and utilitarian considerations that exist across many receiving communities and make public opinion sensitive to migrants’ life experiences. Second, I note the implications of sea migration events and their associated public reactions for policy and agenda setting. I hereby discuss how public opinion activation is fundamental for policy reactions, and why institutional responsiveness has been disrupted and limited.

1. Introduction

In 2023, Europe saw a new cycle of maritime migration from North Africa and the Middle East. Internationally renowned for its dangerous waters, the so-called Central Mediterranean route in particular was the focus of events connecting Libya, Tunisia, and Egypt to Southern Europe. In February, a boat with about 200 migrants sank amidst harsh weather conditions while trying to land on the coast of Cutro, Calabria. In June, an Italy-bound fishing trawler with about 750 migrants sank off the coast of Pylos, Greece. In August, two shipwrecks off Lampedusa killed at least 42 people.

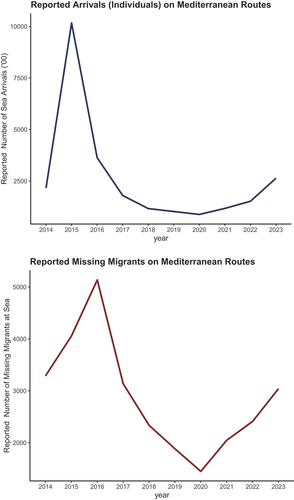

Migration in Southern Europe has been tracked for more than two decades, although it has also become more dangerous in recent years. While tragic sea migratory events have infamously peaked with the immigration crisis in 2015–16, their volumes have been high even in quieter years. Importantly, the trends have picked up again in 2022–23 (see ). These patterns lend themselves to important investigations such as how much the arrivals affect politics and how political debates transcend to institutions, shaping the discourse around immigration in national governments and the European Union. These questions have increasingly been addressed by data-driven research on how Southern Europeans feel about migrants (refugees) at the onset of these events, providing some answers to what shapes public reactions and the implications of public attitudes for domestic and European migration policy.

Figure 1. Trends in migration at sea in the Mediterranean Routes to Italy, Greece and Spain.

This note reviews some research on this topic, focusing in particular on studies employing surveys and observational research designs for the purpose of comparative research. The paper has two primary objectives. First, I briefly illustrate how public attitudes towards migrants at sea are neither monolithic nor unconditionally concentrated in certain areas; rather, public reactions correspond to a combination of emotional and utilitarian considerations that exist across many receiving communities, and make public opinion sensitive to migrants’ life experiences. Second, I discuss the implications of sea migration events and their associated public reactions for policy and agenda setting. I hereby discuss how public opinion activation is fundamental for policy reactions, and why institutional responsiveness has been disrupted and limited. I draw especially on research on Italy as an archetypal country where sea migration has steadily affected domestic and outwards looking foreign politics, whilst making connections with other European countries.Footnote1

2. Public opinion on sea migrants

Today, the policy community enjoys a robust theoretical and empirical debate on migration thanks to political science efforts to systematically trace its political causes and consequences. However, while much of this research has been focused on immigration in specific areas where abundant administrative and survey data exists (e.g., Scandinavia, Switzerland), the migration dynamics in other European regions have been equally salient for domestic and international politics. Europe’s Mediterranean border is one of such important yet under-researched areas. It is known that migration events in Southern Europe have sharply increased in recent years. However, it is still up to debate whether this trend may be cyclical (in addition to seasonal), and how under documented it might be. Against this background, some recent research has tried to explore the influence of these events in the framing of immigration politics up to the highest levels of European governance. In this section, I review what we know about public attitudes at the onset of sea migrants’ arrivals in this region, and what might drive the most noteworthy institutional reactions to date. I focus on attitudes in the most exposed and largest Mediterranean countries, while drawing on lessons from Europe at large. Empirically, the literature covered in this section refers to Spain, Greece and – in particular – Italy.

2.1 Assumptions and debates around public attitudes towards (sea) migrants

Theories of public attitudes towards migration suggest that Southern European communities most exposed to receiving immigrants will be less likely to mobilize in support of immigration. This is because of congenital economic and employment issues in Southern Europe, which tends to be poorer and with weak labour markets (Magni, Citation2022). Relatedly, the capitalization of migrants’ reception by chauvinist political forces decreases sympathy for migrants, as some evidence from Greece suggests (Dinas et al., Citation2019).

However, this may not be the whole story. Recent applied studies show that public opposition to migrants is neither uniform in Southern European countries nor is uniformly dictated by economic or cultural anxiety. Voters’ ideology often trumps other concerns, as several works have shown. Furthermore, some empirical research suggests that a significant section of Southern Europeans mobilize positively, as indicated by participation and contribution to NGOs working on local migrants’ welfare (Pulejo, Citation2021). Importantly, being geographically exposed to migrants’ arrivals is not per se a motivation for public backlash. In fact, it is increasingly evident that geographic proximity to migrants’ arrivals or, once arrived, immigration reception settlements, is not an explanatory factor of opposition in itself.

This may be for several reasons. The location where migrants are identified determines how physically close recipient communities are to incomers and therefore how direct their impact will be. Depending on the conditions of migration, this impact may not be one of social or economic competition. For example, the more (or less) disastrous conditions of travels of refugees, or whether many are deemed vulnerable at arrival, may activate more empathic emotions. Alternatively, a closer point of contact to migrants may even be a catalyst for solidarity of other ingroup regions.

2.2. Empirical evidence on public exposure to sea migrants

The complex, potentially mixed expectations derived from the theory emerge in the empirical literature, especially i new geographically targeted research. Research from receiving communities in Spain suggests that close territorial interactions with immigrants reduce prejudice but that this is not driven by the economic environment of the recipient, and therefore the immigrants (Rodon & Franco-Guillén, Citation2014). Work from Greece is even more mixed in that the increase in hostility in Greek communities following the contact with immigrants (Hangartner et al. Citation2019); however, these effects seem to be fundamentally related to the passage of immigrants on Greek islands then moving to other places, so it is hard to disentangle whether it is confounded by the transitional nature of migration in these communities.

Research from Italy suggests similar patterns of public reactions. According to a recent study, the geographic proximity of arrivals of sea migrants seems to generate proper empathy in cases in which loss of life is reported (Genovese, Citation2023). This suggests that, while geographic vicinity may have ambiguous effects on public opinion, it can have positive implications. Furthermore, the distribution of migrants on the recipient territory also causes variation in public reactions. In Italy, the low-scale concentrated distribution of migrants can cause more far right populist rallies, but at the same time the population near small immigration centres has frequently shown relatively little resentment to refugees (Genovese et al., Citation2022).

Experimental work further illustrates what geographic distance from migrants really means for recipient citizens (Genovese et al., Citation2022). Geolocated surveys fielded in Lazio, Lombardia and Sicily in 2018 and 2019 presented 1500 Italians with randomized vignettes of immigrants either in their geographic municipality (or not), either having arrived in distress (or not), or in a combination of these situations. The respondents were asked to select which immigrants they would have wanted to support through a (researcher-provided) donation. The results show that Italians are on average more likely to support the migrant with a more traumatic transit. At the same time, the closest migrant receives more support than the more physically distant migrant. This is particularly important given that past theories of immigration attitudes have suggested that migrants compete with locals for, e.g., labour market access. Clearly, this research suggests that geographical proximity either activates feelings of commonness or makes natives believe that migrants can spend the money received in their locality, possibly also through the concentration of NGOs and the related resources funnelled in reception centres, or the positive impact that low-skill labour can have in these regions (e.g., through care for seniors or manual work). This intuition points to the fact that geographic proximity of migrants may also be seen as an opportunity for capturing or redistributing monetary resources. This is consistent with findings from other studies that observe how municipalities in Italy and Spain have regularly intervened to lobby higher-level institutions, e.g., the European Commission (Alagna, Citation2023).

In summary, extant evidence suggests that Southern Europeans have a more sensible level of openness to immigration than often assumed, despite economic concerns and politically weaponized anxieties. Geographic proximity to migrants is not per se a deterrent to support for migration. Given certain controlled conditions, receiving Mediterranean societies are willing to engage with migrants’ arrivals and, provided the resources, accept their settlement in local communities. A further interpretation is that Southern Europeans are worried about immigration as a proxy for their own economic vulnerability and as a function of how they trust the national (and European) institutions to manage it.

3. The public’s relationship with the media, agenda setters, and policymakers

Against the landscape of public opinion delineated above, it is worth reflecting on how public attitudes may matter for agenda setting and policy making in the immigration political space in Southern Europe and, more generally, in the European Union context. The conjecture here is that sea migration shares some characteristics with other types of migration in terms of demographics and level of precarity.Footnote2 At the same time, I keep with the distinction of sea migration which is often more geographically contained than other types of migration, more identifiable, and therefore more amenable to media use and politicization (Berry et al., Citation2016; Genovese, Citation2023).

Against this background, this section speaks about the relationship between the public and the media on sea migration, on the one hand, and the responsiveness of domestic and European institutions, on the other.

3.1 Media framing around sea migrants and impact on immigration politics

In theory, the media in a democracy serves the role of representing the reactions of the public over various contemporary issues, including immigration. In practice, the link between public opinion and media coverage may not be this simple. There are many ways in which the media may frame immigration in ways that are disjoint from the public mood.

First and foremost, the media may selectively cover immigration news only when there is a guarantee that the stories will ‘sell’. This is of course a function of the mobilization of many actors. For example, rescue NGOs and their proactiveness (or lack thereof) influence the media framing of refugees (Cusumano & Bell, Citation2021) and, by proxy, the way citizens think of the pull versus push dynamics between migrants and domestic authorities (Cusumano & Villa, Citation2021). Similarly, more tragic stories that do not involve NGOs may receive more media attention as they are expected to be more shocking (Emeriau, Citation2023). Furthermore, the media may depict immigration through the ideological lenses of news outlets. So, at the onset of new arrivals, the media framing of migrants’ stories could be the product of the reactions of political leaders in tune with the media itself, and not necessarily the public. Accordingly, if immigration is especially an issue of far right parties, it is more likely to be covered by more far right media overall.

These characteristics of the media seem to effectively exist in Southern Europe. But this does not imply that the mainstream media is incapable of covering immigration through the eyes of the public. This is rather to say that, under certain conditions, the media is actually invested in showing communities’ genuine reactions, including the more positive ones, towards immigrants. In particular, this increased media engagement and representation of local public reactions seems to occur when shipwrecks occur on domestic shores (Genovese, Citation2023). This suggests two things.

First, it indicates that some form of trauma or, in the extreme case, loss of life is a fundamental condition for more media activation, which then becomes a catalyser for politicization and agenda setting. Along these lines, it was only after the mediatic indignation following the 800 deaths of the Lampedusa shipwreck in October 2013 that various important figures like Pope Francis decided to pay attention to refugees at the Southern European border. However, without loss of life, it appears that sea migrants’ arrivals tend to remain vaguely silent in the media, possibly feeding into public indifference and neglect.

Second, this observation implies that local media sources are best equipped to represent public reactions from the Mediterranean countries. That is, if local media exists or, at minimum, if national news have local headquarters in proximity of where arrivals and settlements occur. Unfortunately, these local media infrastructures are increasingly rare, in Southern Europe especially as a consequence of years of austerity and underfunding. Consequently, even if the Southern European press is best suited to report on refugees and migrants, the media enterprise in these countries as a whole is less likely to have the capacity to report as accurately as they should – therefore giving grounds to unfounded narratives and dangerous misinformation (Berry et al., Citation2016).

In short, while there is evidence that the media is capable of reporting on the full spectrum of public reactions to immigrants, in reality it tends to emphasize the most radical and extreme versions of public opinion, and only in the most dramatic of immigrants’ circumstances. This is a problem for how the public sees itself represented in the media, for the mobilization (and opportunism) of politicians around the issue, and – as I discuss below – for the health of Euro-mediterranean democratic institutions.

3.2 Policymakers’ reactions and the management of sea migration

The representation of public opinion at the onset of arrivals inevitably spills over into the way political offices and institutions respond to immigration and refugees. This is to say that the (mis)representation of public sentiments around immigration directly affects how policymakers perceive public opinion and, vice versa, how the public interprets the response from policymakers.

The risks of misrepresentation of public opinion can be traced in various ways in the politics of European immigration today. For example, the skewed coverage of migrants’ arrivals during shipwrecks and the problematic framing of recipient communities’ extreme reactions have affected the way the general public relates to other involved actors – for example, NGOs’ boats at sea. Because the media tends to overflow information only when masses of migrants arrive on domestic shores or when there is significant loss of life, a significant chunk of the European public seems to be convinced of the negative impact or – in the extreme version – opportunism of NGOs. As of today, conspiracy theories portray volunteering boats as ‘pull factors’. This depiction has influenced party politics as well. For example, in August 2023 Italian Prime Minister Meloni proposed to legally stop civil migrant rescues with a clampdown on charity ships.

The fixation with tragic events at sea has also influenced the way in which immigration in Southern Europe is now seen mainly with the lenses of crisis management and emergency. Since the 2015 refugee crisis, national governments have appeared to deal with political mobilization around immigration only in the aftermath of major shipwrecks. Take for example the case of Italy. Operation Mare Nostrum was a year-long naval and air operation commenced by the Italian government in October 2013, immediately following the Lampedusa migrant disaster. The European operation that superseded it, called Operation Triton, was doubled in size after the April 2015 Libyan shipwrecks that killed around 1500 people. Along these lines, the European Commission has regularly acted on immigration following the record highs of refugee waves. The Turkey–Greece containment agreement was signed as a follow-up to the 2016 Syrian humanitarian crisis. Similarly, at the dawn of a new record wave of sea migrants in the summer of 2023, the Commission announced 127 million Euros to give to Tunisia to collaborate on migration control.

These facts highlight how EU governments systematically use public attitudes towards migrants at the heights of emergency moments to extract political or economic gains. For example, it is usually in the aftermath of these events that member states request compensation from the EU institutions, and EU institutions commit to respond following these urgent requests. This short-sightedness of the policymaking cycle on immigration is in line with other areas in which EU institutions have operated lately, and a large literature on European politics has suggested the pitfalls of an EU that works only in a responsive mode. The EU immigration politics is further complicated by the institutional setup born from the Lisbon Treaty. The Dublin Regulation, which is the EU law through which a country in which an asylum seeker first entered is responsible for processing their asylum application, is a source of political contention. This legislation inherently puts administrative burdens on EU frontier countries, which have called for reforms to the system. The legislation has not yet changed; however, these characteristics of EU politics have made immigration a bargaining chip for Southern European governments against EU institutions.

In short, the electoral incentives and institutional conditions described in this section – tied together with a steady state of democratic backsliding and a cross-national rise in far right populist parties closely tied to nativist policies – contribute to a short circuit in which the public rarely feels fully represented during major migration inflows, and politicians feed the public concerns captured at these specific moments. Against this background, the EU mechanisms of refugee redistribution represent ideas of solidarity that are rarely realized. Consequently, the EU is often used opportunistically as a levy for new short-lived resources or, alternately, as a political scapegoat. This is an important finding for, on the one hand, it suggests the high level of trust that institutional actors have to build to provide the social conditions for immigration to occur in peace. On the other hand, it highlights the importance that voters attribute to institutional actors (e.g., their national representatives and European institutions) to handle immigration and make it more manageable; thus, as long as institutions own the issue, it can become a political area where elections can be fought on.

4. Conclusion

This note offered an overview of various elements of public life that have featured the politics of immigration – and, specifically, sea migration – in Southern Europe in recent decades. It started with a discussion of the nature and dynamics of public attitudes towards migrants at sea. As recent research suggests, public attitudes are neither static nor perfectly uniform. Contrary to common wisdom, there is a fair degree of (at least temporary) empathy among the public after tragic mass inflows. However, this empathy is neither always well captured by the media nor it is well represented by political leaders. Furthermore, it may be simply one of the two sides of polarization on this issue.

This piece also describes why the state of migration politics at the Southern European border is a function of a mix of resource scarcity concerns and opportunistic mentality. It highlights how this is a suboptimal yet steady equilibrium for policymakers, who are incentivized to think about short-run political management rather than long-run policy solutions. It also gives a brief analysis of how this suboptimal equilibrium is fed by EU institutions and laws

This picture spurs many questions on the future of the sustainable and democratic politics of immigration in Southern Europe. At the EU level, it seems obvious that the Dublin Regulation should undergo adjustments, yet reforms would require ‘consensus’ among Member States that is unlikely to be achieved anytime soon. It also seems sensible that EU institutions or domestic governments should abandon the emergency mode of dealing with refugees. Yet in the era of the so-called polycrisis it seems that the overwhelming disruptiveness of other emergencies will crowd out governments and their long-running plans. For similar reasons, it is unrealistic to expect that blocking migration at the source or forbidding the operation of NGO boats in the Mediterranean is a politically feasible – or morally right – set of solutions.

Perhaps more realistic and constructive, then, is the prospect of establishing a long-term view on immigration that takes the microfoundations of public attitudes and their local community implications more seriously. In other words, it may be worth thinking about how to (re)pivot the management of immigration at the local level, from the ground up. This is not necessarily a recommendation for decentralizing immigration policy; rather, it is a call to think harder about the geopolitical conditions of local recipient communities to understand how they may be most suited to handle immigration.

In conclusion, this short paper has presented evidence that supports the conjecture of place-based politics related to immigration that are tailored to the needs and, basically, the geographies of constituencies and communities. The empirical findings reviewed here provide in part an exhortation to recognize that some integration and migrants’ allocation policies will not work in small islands like they work in large urban centres, and vice versa. But this is also an invitation to think about how providing resources to local communities at the frontline of the Southern European borders may change the trajectory of politics on immigration. Bottom-up investment in local journalists and redistribution of material resources (e.g., labour integration programmes) may go a long way to manage migrants in the long run and, importantly, to restore the trust across public, media and policymakers that is so fundamental to manage the immigration crises of the future.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Of course sea migration does not need to be connected with sea arrivals, and immigration from coastal lands can also occur in other ways (for instance, by land to the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla in Northern Africa). In this article, I focus specifically on sea travels from Northern Africa and the Middle East as these are major sources of politicization and policy mobilization.

2. In terms of age, gender and other demographic traits, immigrants walking across the Balkans and Eastern Europe in 2015–16 were overall similar to immigrants crossing the Mediterranean by boat, despite the former coming mostly from East Asia and the Middle East while the latter from Sub Saharan states and Northern Africa.

References

- Alagna, F. (2023). Civil society and municipal activism around migration in the EU: A multi-scalar alliance-making, geopolitics. Geopolitics Forthcoming, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2023.2230902

- Berry, M., Garcia-Blanco, I., & Moore, K. (2016) Press coverage of the refugee and migrant crisis in the EU. UNHCR Report.

- Cusumano, E., & Bell, F. (2021). Guilt by association? The criminalisation of sea rescue NGOs in Italian media. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 47(19), 4285–4307. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2021.1935815

- Cusumano, E., & Villa, M. (2021). From “angels” to “vice smugglers”: The criminalization of sea rescue NGOs in Italy. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 27, 23–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-020-09464-1

- Dinas, E., Matakos, K., Xefteris, D., & Hangartner, D. (2019). Waking up the Golden Dawn: Does exposure to the refugee crisis increase support for extreme right parties? Political Analysis, 27(2), 244–254. https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2018.48

- Emeriau, M. (2023). Victim or threat? Shipwrecks, terrorist attacks and asylum decisions in France. American Journal of Political Science. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12829

- Genovese, F. (2023). Empathy, geography and immigration: Political framing of sea migrant arrivals in European media. European Union Politics, 24(4), 771–784. https://doi.org/10.1177/14651165231180758

- Genovese, F., Belgioioso, M., & Kern, F. (2022). The political geography of migrant reception and public opinion on immigration: Evidence from Italy.

- Hangartner, D., Dinas, E., Marbach, M., Matakos, K., & Xefteris, D. (2019). Does exposure to the refugee crisis make natives more hostile? American Political Science Review, 113(2), 442–455. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055418000813

- Magni, G. (2022). Boundaries of solidarity: Immigrants, economic contributions, and welfare attitudes. American Journal of Political Science, 68(1), 72–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12707

- Pulejo, M. (2021). Quo Vadis? Refugee centers and the geographic expansion of far-right parties. Journal of Political Institutions and Political Economy, 2(3), 347–364.

- Rodon, T., & Franco-Guillén, N. (2014). Contact with immigrants in times of crisis: An exploration of the Catalan case. Ethnicities, 14(5), 650–675. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796813520307