ABSTRACT

Social contracts have recently re-emerged as a field of research. They can stabilize the relationship between state and society by establishing some predictability about the mutual deliverables between actors - especially if they are flexible for modifications to take account of changes in the framework conditions, the positions and preferences of their parties, and prevailing norms, values and ideologies. The question is, thus, when, why and how social contracts change. We argue that they change more continuously in countries with institutionalized mechanisms of renegotiation, such as parliamentary debates, open public discourse and interest group lobbying. These are more often democratic countries even if changes in democratic countries can also happen suddenly and unexpectedly. Autocratic countries, though, tend to be more resistant to regular change because they lack the procedures and mechanisms. This includes most countries in the Middle East and North Africa. Here, significant changes usually only take place if something unforeseen happens, such as a price shock, a pandemic, an earthquake or an invasion by a foreign country. At these ‘critical junctures’, at least one key actor in a country – often but not always the government – must react. This actor can, but does not have to, change its previous course.

1. Introduction

The role that social contracts play in the stability of countries and the well-being of people has recently re-emerged as a field of research. Social contracts can be defined as the total set ‘of explicit or implicit agreements between all relevant societal groups and the sovereign (i.e., the government or any other actor in power), defining their rights and obligations toward each other’ (Loewe et al., Citation2021). ‘Implicit” means that social contracts can be accepted or at least tolerated tacitly without formal expression of consent.

The literature on social contracts has focussed mainly on their scope, substance and temporal dimension rather than the reasons for and moments of change. Some authors have compared different social contracts over time (e.g., Cassani (Citation2017) for China; Hinnebusch (Citation2020) for the Arab world; Feldmann and Mazepus (Citation2018) for Russia) and across countries (e.g., Kaplan (Citation2017 for fragile countries, Vidican Auktor and Loewe (Citation2022) for Arab countries). Others have described their development (e.g., Rutherford (Citation2018)) or analysed how social contracts can and should change in order to achieve certain goals and how they might ideally look (e.g., McCandless (Citation2018) or World Bank (Citation2004)). Little research has been conducted on why, when and how social contracts change, that is, when the parties’ rights and obligations are modified.

This special issue focusses on the following two questions. What are the important drivers of change for social contracts? And when do social contracts change at all? This introductory article serves as a conceptual framework for the various thematic and contextual explorations of these questions provided by the other articles in this special issue.

These questions are important from both an academic and a policy-making perspective. We see that social contracts change perpetually, gradually and incrementally in some countries while they remain almost the same for many years in other countries, only to change unexpectedly and radically at some point in time. An example of the latter are the changes that occurred in some Arab countries after the 2011 uprisings. Of course, it is interesting to know the underlying factors of such unexpected change. However, for both domestic and foreign policy-makers and other actors of political change, it is also helpful to know when social contracts may change in order to modify the path of such change or accelerate it.

In this introductory article, we argue that social contracts establish a degree of certainty in the expectations of all involved parties about what they must give and receive. Thereby, social contracts create trust between the parties and stabilize the relationship between society and the state. Nevertheless, social contracts occasionally need to be modified to take account of changes in the framework conditions. The more flexible and adaptive a contract is, the more stability it provides to its country in the medium and long term. Our starting point is that social contracts change habitually in some countries with institutionalized and inclusive mechanisms of renegotiation, such as parliamentary debates, open public discourse, free debates in the media, interest group lobbying and political associations – provided that these mechanisms have an impact on political decision-making. However, in other countries that lack these mechanisms and often have a very uneven distribution of power among the contracting parties, major change happens more sporadically. The articles in this special issue illustrate this idea in different countries of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA).

This introductory article proceeds as follows. Section 2 introduces our understanding of the social contract. Section 3 discusses what change in social contracts means. Section 4 analyses which actors can initiate gradual reforms and when their initiatives tend to be successful. Section 5 argues that change can also happen unexpectedly and more abruptly when key actors in a country are forced to react to changes in the framework conditions, unforeseen events or foreign interventions and, thus, face ‘critical junctures’ in their decision-making processes. Section 6 concludes with policy recommendations.

2. Conceptualising social contracts

2.1. Normative and non-normative conceptualizations

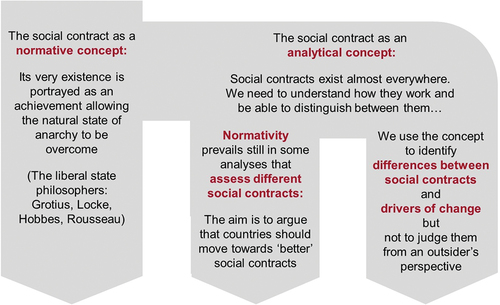

The concept of the social contract was coined by the liberal state philosophers (Hobbes, Citation1651; Locke, Citation1689; Rousseau, Citation1762). They portray the social contract as something that is good or even necessary to overcome the natural state of anarchy and to establish property rights and security or distributive justice in a society. More recently, the term ‘social contract’ has been applied in a non-normative way (e.g., Cook & Dimitrov, Citation2017; El-Haddad, Citation2020; Heydemann, Citation2021, Hinnebusch, Citation2020; Kaplan, Citation2015; Kinninmont, Citation2017). These authors argue that social contracts exist in every state and that their existence as such is neither good nor bad. Rather, the terms of the social contract determine how desirable it is for its parties.

Another strand of literature propagates specific kinds of social contracts on the basis of established theories and ideologies. These authors (e.g., Al-Razzaz, Citation2013; Devarajan, Citation2015; World Bank, Citation2004) call for ‘new’ social contracts to increase economic competition, improve distributive justice or strengthen political participation (see ).

In contrast to this, we argue that only the parties involved can say whether their social contract is ‘good’ or ‘not good’ for them, and how it should be improved. Contrary to what some may expect, for instance, in Egypt, Tunisia and Lebanon, many people would give priority to the provision of economic and social services over their own political participation if they had to choose (Loewe & Albrecht, Citation2023). Even if we use the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as an internationally endorsed framework of orientation, we cannot assess the quality of social contracts in an objective way. This is due to the numerous trade-offs between the 17 SDGs and the fact that people subjectively prioritize some SDGs over others.

Therefore, we suggest assessing social contracts based on a system-immanent logic: by their functionality. Their function is to stabilize state-society and intra-society relations. On the one hand, a social contract provides certainty about the mutual deliverables of all its parties. Thereby, they relieve the contracting parties of renegotiating their mutual obligations all too often. On the other hand, as explained above, social contracts must remain flexible and be adjusted when the contracting parties wish. If one side becomes dissatisfied, the social contract becomes dysfunctional; it creates grievances, destabilizes polity and society and negatively affects social cohesion (Leininger et al., Citation2021, p. 3). In the most extreme cases, this can lead to a revolution, putsch or civil war.

Nevertheless, neither the acceptance of a social contract nor its renegotiation has to be explicit. A social contract exists and can be renewed even if some or all of its parties consent only tacitly (Locke, Citation1689, p. II, §119). For example, citizens tolerate the existing social contract or its reform by not rebelling against the government, paying taxes and using the services provided by the state (Stone, Citation2014). In other words, their options are ‘exit, voice, and loyalty’ (Hirschman, Citation1970). Given that ‘exit’ and ‘voice’ tends to come with costs in terms of money, time, reputation and even physical security, less powerful groups often have limited alternatives to ‘loyalty’. They may thus consider the contract to be unfair or even immoral, but it is still effective.

2.2. The three dimensions of social contracts

We argue that social contracts vary in (i) their scope, (ii) their substance (the deliverables exchanged between societal groups and the government) and (iii) their temporal dimension (Loewe et al., Citation2021).

Scope: Social contracts involve the ruling actor (i.e., the government or other type of authority) and the most influential groups of society. Of course, neither the government nor the societal groups are typically homogeneous ‘blocs’, and foreign actors can have similar or equal relevance to the local contracting parties, or at least considerably influence them. In the Occupied Palestinian Territories, for example, Israel is a relevant party; similarly, Russia and Iran are influencing the social contract in Syria. The scope of a social contract is, thus, determined by its acceptability for the different actors in a state and society (and the government’s ability to enforce the social contract for all other actors) rather than by official national borders.Footnote1

Substance: Social contracts can require the government to provide three kinds of deliverables to the different societal groups: protection (collective and individual security), provision (infrastructure, social protection, education and other social and economic benefits) and participation (in political decision-making at national and local levels). In exchange, citizens – and society at large – are expected to accept the government in power, pay taxes and invest in public goods (engage with the local community or school, do social work, limit pollution, etc.). This give-and-take lends the government legitimacy, thereby reducing the need for authoritarian regimes to use repression in order to stay in power. Of course, the level of protection, provision and participation granted by the government varies according to the negotiating power of the contracting partners. Some governments feel powerful enough to provide only one or two of these three ‘Ps’, but such disenfranchisement risks backlash, as the Arab uprisings and the 2022 protests in Iran have shown.

Time: Social contracts endure as long as they meet their parties’ expectations. Permanent adaptation is crucial to take account for change in these expectations or in the framework conditions. Otherwise, a social contract can be questioned and replaced by a new one as occurred in Tunisia in 2011.

The social contract has often been criticized for being a rather abstract model but at least its substance – that is the deliverables of the state and the societal actors – can be measured as we show elsewhere (Loewe et al., Citation2024.

3. The changing nature of social contracts

One set of rules may not be acceptable forever – at least not for all parties of the social contract. Society may ask to get more from any of the three Ps or be less willing to pay taxes – and the government may demand higher taxes, or it may want to deliver less protection, provision or participation. Changes in social contracts, thus, can be understood best through changes in their substance: the amount, nature and distribution of the deliverables given by the contracting parties. Often, however, these changes affect the scope of social contracts as well. Typically, they strengthen some actors and weaken others and, thereby, may alter the composition of the group of contracting parties. For example, the government may fade out the preferential treatment of a specific societal group and instead favour a different one. This happened in Egypt during the 1990s and 2000s when the government replaced the urban middle class with crony capitalists as their main ally in society (El-Haddad, Citation2020), and again more recently when the military regime started to reorient towards other groups of the population again (Rutherford in this special issue). Likewise, the government may increase the preferential treatment of a specific group to an extent that other societal groups hardly receive any state deliverables any longer. This was the case in Syria after 2011, when the al-Asad regime increasingly ostracized (alleged) members of the opposition (Sudermann & Zintl in this special issue). The geographical scope of social contracts can also change if, for example, a government attempts to extend its borders (as Russia did in Crimea and the Donbas) or when a government tries to influence and provide resources to social groups in other countries (such as Iran in Lebanon) or when a government stops providing services to some parts of the country (like the al-Asad regime did after the civil war in Syria).

In the following, we discuss how and for what reasons social contracts may change.

3.1. Reasons for change

Several factors may call for a change in social contracts:

Changes in the political, economic or environmental framework conditions are typically beyond the control of the contracting parties but can affect the functionality of social contracts (Kinninmont, Citation2017; Mahoney & Thelen, Citation2010). For example, a natural disaster may severely affect the income of farmers, thus, fuelling unrest of often already marginalized groups. Economic sanctions (such as those imposed by the US on Iran during the 2010s) can trigger inflation thereby diminishing the purchasing power of the population. The involvement of foreign powers in a domestic war (like in Iraq, Libya or Yemen) or in the government’s political decisions can also change the attitudes of nationals towards the social contract (Rutherford in this issue). War in a neighbouring country and a high number of refugees can put domestic resources under strain and question whether and to what extent refugees have access to the state’s protection, provision and participation (Abedtalas in this issue). Digitalization can ease the delivery of protection, provision and participation by the government but also the surveillance and repression of citizens (Zintl & Houdret in this issue).

The relative distribution of power between the contracting parties can shift and, hence, allow some to alter the social contract to their benefit (Mahoney & Thelen, Citation2010). Often, such change is due economic factors such as a significant increase or decrease of revenues by the government or key societal groups. For example, increasing revenues from oil and gas exports enabled MENA governments in the 1970s to expand the provision of social and economic services and thereby buy additional legitimacy. Thereby, they established what has become known as ‘populist-authoritarian provision pacts’ (Hinnebusch, Citation2020). When their revenues decreased again after 1985 due to declining energy prices, the governments had to curtail the existing social contracts: They raised taxes and focused the provision of social and economic benefits on strategically important social groups (Weale, Citation2013; Yousef, Citation2004). As a result, crony-capitalist ‘unsocial social contracts’ (El-Haddad, Citation2020) emerged throughout the MENA region. Citizens can accept such changes by paying the higher taxes and not raise their ‘voice’ (Hirschman, Citation1970) or ‘exit’ (for instance by migrating). However, society does not always agree on higher taxes without better services in return or more participation of the parliament in political decision-making.

3.1.1. The relative distribution of power between the contracting parties can shift

Geopolitical shifts can also impact the distribution of power between the contracting parties. In Iraq under Saddam Hussein, for example, the Arab Sunni minority had preferential access to public sector jobs and economic opportunities. Since the US military toppled the Ba’ath regime in 2003, the Shiite majority has enjoyed these opportunities.

Digitalization is a less visible factor. The increase in surveillance in the region for example has substantially increased regime power in relation to citizens even without major economic or geopolitical changes (Zintl & Houdret in this issue).

In many cases, changes in the distribution of power can even affect the composition of the groups of relevant actors (Mahoney & Thelen, Citation2010) and, thus, affect the scope of the social contract. A reduction or increase in economic or military support by foreign actors can weaken, or in some cases strengthen, the state vis-à-vis society (Sudermann & Zintl, Rutherford, both in this issue).

A key party can neglect its contractual obligations or interpret them differently than before. The phenomenon is particularly common when there is a generational turnover in one of the contracting parties (Mahoney & Thelen, Citation2010). As a result, other contracting parties can become upset when they realize that the social contract has become less beneficial for them. Such was the case in 2010 and 2011, when people took to the streets in Arab countries to protest that their governments were no longer delivering enough provision (social and economic services) and at the same time not allowing any tangible political participation (Rutherford in this issue).

People’s awareness of the effects of their social contract can change. One party or more may be ‘seriously unhappy with what they are getting’ (Khan, Citation2017) because of new information showing that the social contract in their country is less beneficial for them than previously thought. Dissatisfaction may arise from, for example, the discovery that a government intervention is benefiting the rich rather than the poor. Widespread digital technology can enlighten citizens to their plight. Social media, especially, enable locals to interact closely with people elsewhere and compare their economic situations and levels of participative governance (Zintl & Houdret in this issue). Such cross-border comparison is especially likely if there is a sizable diaspora with close relations to relatives and friends who stayed behind.

Changes in norms, values, ideologies or official narratives can also have an impact (Green, Citation2016, pp. 47-68; Sztompka, Citation1993; Sudermann & Zintl in this issue). Nasserism and socialism, for example, spread across the MENA region during the 1950s and 1960s and pushed even conservative monarchies like Jordan and Oman to provide free public education and health services to the population (Loewe et al., Citation2021). Likewise, Islamism became popular during the 1970s and 1980s and put several governments under pressure to alter their cultural and family policies and laws.Footnote2 In contrast, the protests in Iran against discrimination of women indicate that many Iranians have changed their opinion about how authorities should interpret Islamic rules of conduct.

3.2. Types of change

Changes in social contracts can be formal, such as a new constitution, or informal and it may even be visible only in retrospect. An example is the slow but steady reduction in public sector employment in many MENA countries from the 1980s through to the 2000s. These changes were not popular but they were tacitly accepted (they led to protests but to only some changes in the social contracts of the region).

Likewise, changes can have small-scale or more far-reaching impacts.Footnote3 A reduction in educational expenditure or property tax rates, for example, may have only small-scale effects, whereas the nationalization of all farming land has more far-reaching consequences. In the latter case, it may be difficult to say whether the existing social contract has changed significantly, or been replaced by a different one (see Streeck & Thelen, Citation2005). However, the beginning of a (new) social contract could also be determined by formal criteria. For example, the declaration of an entirely new constitution could be considered a clear sign of a new social contract, at least if the constitution is based on a participatory public deliberation process.

There is also no clear line between small-scale and large-scale change, rather there is a broad continuum. The following three questions provide some orientation as to whether change in a social contract has smaller or larger impacts:

Change in the government’s priority of the 3Ps: Has the delivery of protection, provision or participation merely decreased or increased, or has there been a clear change in the priority given to the three Ps? In the latter case, the government may no longer be reliant on, for example, provision to legitimize its rule, but increasingly on protection only, as has been the case in Egypt under President Al-Sisi (Rutherford, Citation2018).

Change of the government in prioritising recipients of the 3Ps: Has the emphasis of the government in delivering protection, provision and participation merely shifted somewhat from one government programme or service to another, or has the government’s focus shifted from one societal group to another?

Change in society’s needs for the 3Ps: Is there a change in society’s readiness to accept the government’s rule and to pay taxes and fulfil other duties? Have grievances evident in the form of protest or rebellion in society increased? Are there new demands from particular social groups that were not included in existing social contracts, such as demands for digital connectivity or inclusion of populations living abroad in political decision-making?

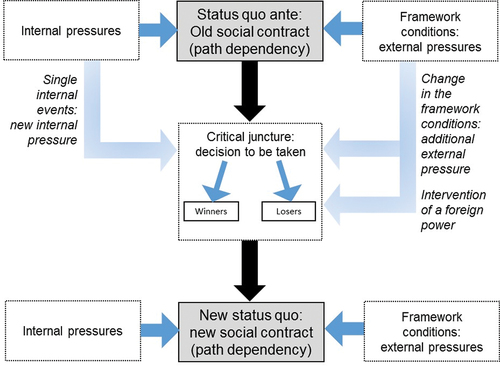

Finally, it makes sense to distinguish between continuous and gradual changes and changes that come suddenly and are all-encompassing (see ). Gradual change is the norm in countries with institutionalized and inclusive mechanisms of explicit social contract renegotiation such as parliamentary debates, open public discourse, free debates in the media, interest group lobbying, and political associations (Streeck & Thelen, Citation2005). In contrast, it is less common in countries without such mechanisms or in countries where different actors have uneven negotiating power. Here, the dominant actor – often the government – can refuse any amendment, and even neutral moderators may find it difficult to facilitate a dialogue. Typically, only unexpected events that challenge the dominant contracting party can bring about change, which is then often sudden and all-encompassing.

In any case, the reform of a social contract cannot always fully restore its functionality. Social contracts can degenerate or be replaced with less binding or less comprehensive ones, which do not stabilize state-society relations in the same way as before. There is a risk of decay, erosion and revolution, resulting in instability, conflict or even civil war, but also a chance of improvement, expansion and functional upgrading, which enhances the parties’ adherence to the contract.

4. Gradual change

Gradual change is likely if the parties of a social contract agree to change it, because one party is no longer satisfied with its substance.

4.1. Initiation of gradual change

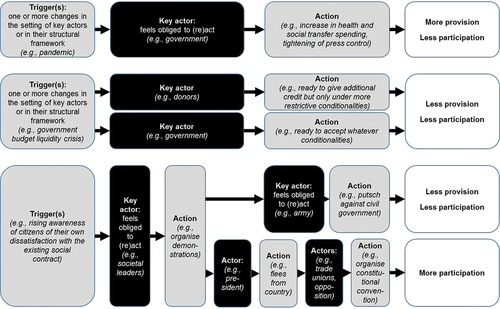

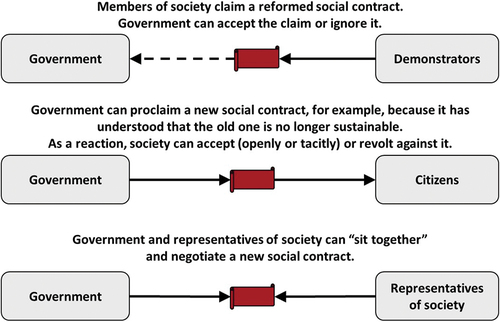

The renegotiation of a social contract can be initiated by any of its parties (see ):

Figure 3. Actors that can initiate the reform of a social contract.

Members of society can demonstrate or protest and call for amendments in the three Ps. The government can then accept the claims or at least some of them (Tunisia, see Weipert-Fenner, Citation2023) or ignore them and thereby take the risk of a revolution or civil war (Syria, see Sudermann & Zintl in this issue).

The government can unilaterally proclaim a new social contract with a new constitution, legal reforms or other major reforms such as the decrease or increase of subsidies or social transfer payments, improvements in the public health or education systems or a revision of the election law. In this case, society can revolt against the new social contract or accept it (Jordan and Morocco since 2011, see Houdret & Furness in this special issue). Therefore, the government sometimes does not admit that its reforms are effectively replacing the old social contract with a new one, which has in a way been the case in Egypt under President Sisi (see Rutherford in this issue). So far, large parts of the Egyptian society have – under conditions of harsh repression – tacitly accepted the recent transformations. However, the process is ongoing and it is too early to know whether Egyptians will continue tolerating their situation, or rather raise their voice or exit.

The government can hold talks with representatives of societal groups on a new, possibly more stable social contract (like in Tunisia after the revolution regarding trade unions, human rights and lawyers’ organizations; Mahmoud & Súilleabháin, Citation2020). The talks can be suggested by the government or society and take place in formal meetings (such as a constitutional convention), or more informal debates in the media, or through intermediary institutions (Houdret & Furness in this issue). Sometimes, the talks involve only parts of society, for instance, organized labour, in the effort to conclude a closer social dialogue (like in Tunisia, see Weipert-Fenner, Citation2023) or at least to fulfil international calls for such a social dialogue (like in Lebanon, see Madi in this issue). In any case, to be effective, talks require institutions of free expression of opinion. Governments can also seek to deepen exchange with parts of the population that are not usually or fully considered contracting partners like refugees or nationals living abroad (see Abedtalas in this special issue).

4.2. Conditions for gradual change

In many countries, however, negotiations do not take place, or they fail to generate a compromise between the different contracting parties. This can be due to three reasons:

Internal spoilers who are afraid to lose from reform (Mahoney & Thelen, Citation2010). In authoritarian contexts in particular, the spoiler is often the government, which believes that it is possible to refuse amendments in the social contract, backed by its belief to win any power struggle against society (Egypt or Algeria).

Diversity of interests within society or within the government inhibit the contracting parties in finding a compromise that is acceptable for all of them. Neither government nor society are monolithic blocs, with the effect that it is difficult to distil joint claims from the different and often diverging interests of the sub-groups on both sides. This is particularly true in countries with separatist movements (such as, in different forms, in Sri Lanka, the Berber movement in Algeria, or the Kurds in the Iraqi-Syrian-Turkish border triangle). Likewise, after civil wars, it is often challenging for the former combatants to identify common denominators in their negotiations (Anderson & Choudhry, Citation2015). However, there can also be insufficient readiness to make compromises in other contexts. For example, the political parties in Tunisia failed to develop a shared vision of the future after the 2011 revolution (Mahmoud & Súilleabháin, Citation2020).

External spoilers can have a strong influence and prevent successful negotiation of social contract reform. For example, Iran exerts considerable power in Iraq, as do Russia and Iran in Syria, and Egypt in Libya.

The question is, thus, when social contracts are renegotiated at all? Renegotiations rarely succeed when the most important contracting parties still approve the existing contract. If all parties want a change – especially if they agree on the direction of change (Mahoney & Thelen, Citation2010) – renegotiations are likely to achieve an inclusive result. These two ‘easy’ constellations are, however, the exception. More often, one party or a coalition of parties requests a reform that at least one other party does not want. Here, there are five scenarios in which a change in the social contract is still possible:

Finding a compromise: Parties can find a compromise that accommodates the interests of all, for example, by only implementing some elements of the requested reform.

Giving in: The requested reform does not have significant negative impacts on any relevant party, so even opponents can accept it for the sake of keeping peace.

Compensation: The reform has a significant negative impact on at least one party, but the parties that desire it can compensate ‘reform losers’.

Outvoting: The reform hurts one actor significantly more than the others, but the losing party is not powerful enough to thwart renegotiations. It is outvoted and has to render in the end.

Surrender: One or more parties object the reform, but even together they are significantly weaker than the proponents and must, therefore, surrender.

If the government asks for reforms, all five scenarios are possible. (i) Compromises are possible if the government understands which parts of a reform are more acceptable than others. The Iranian government, for instance, announced in December 2017 that the richer half of the population would no longer receive cash transfers; however, when massive popular protests erupted, only the richest third of all households was removed from the group of transfer recipients. (ii) All societal groups accept the change suggested by the government because they understand that it has mainly positive effects for everybody, for example, increased spending on education and employment or the introduction of e-government in processes of state-business and/or state-society relations (Zintl & Houdret in this issue). (iii) All contracting parties accept the change because those who face significant negative impacts (e.g., the reduction of energy and food subsidies) are compensated). In Morocco (2010) and Iran (2010), households accepted energy subsidy cuts because the government explained well its budgetary pressure to citizens and offered direct social cash transfers instead (Vidican Auktor & Loewe, Citation2022). (iv) Governments implement reforms (e.g., the construction of a large river dam) because they have no significant negative effects on societal groups except the group of households that have to be resettled. This group is, however, relatively small and can be outvoted. (v) If the changes are refused, authoritarian governments often implement reforms against broad societal opposition using intimidation and force. The military in Egypt, for example, removed elected President Morsi from office in 2013 and suspended the constitution. Large numbers of people from very different societal groups protested, but the army dispersed the demonstrations, killing hundreds of protesters and jailing thousands more. Since then, the government has been able to implement unpopular reforms, such as the devaluation of the Egyptian Pound, without major objection (Rutherford in this issue). The protracted Syrian conflict is another case in point. Faced with large-scale protests in 2011, the al-Asad government reacted with violent repression and a revanchist narrative that shaped further developments and, together with outcomes on the battlefield, forced critical voices to accept a second-class citizenship or leave (Sudermann & Zintl in this issue).

More often in democratic contexts than in authoritarian ones, society (or single societal groups) can also ask for changes in social contracts without fear of sanctions; these are expressed in speeches or reform initiatives in parliament, public talks, media articles, manifestations, online petitions, riots, strikes and other means (Khan, Citation2017). The result is often a compromise that satisfies parts of the initial demands (such as in Tunisia in 2013, Mahmoud & Súilleabháin, Citation2020) while authoritarian governments more often just try to ignore the protests such as in Morocco (Bogaert & Emperador, Citation2011) or to use a ‘mix of concessions, cooptation and containment’ (Abdalla, Citation2023, p. 15). This was the case in Egypt, where the claims of independent labour unions for a different labour law have long been delayed (Abdalla, Citation2023).

Authoritarian governments often unilaterally impose an official narrative (Sudermann & Zintl in this issue) and, thus, lack most of the means that societal actors need to express their dissatisfaction without fear and have an inclusive discourse with the government. Therefore, societal demands are often ignored until the people take to the streets against the government.

At that point, the government has a second chance to accept the reforms. Sometimes, authoritarian governments give in – possibly because they want to avoid losing too much reputation internally or externally (like in Egypt in 1977 when President Sadat withdrew subsidy cuts after heavy bread riots). Alternatively, they are afraid to eventually lose the struggle (like in Sudan in July 2019 when the army agreed with demonstrators on the creation of a joint military-civilian council to head the state). Sometimes, governments prefer to focus on other issues such as Egypt’s President Al-Sisi, who gave in to the demands of demonstrators to raise the public sector minimum wage before holding a referendum that allowed him to rule the country for another 20 years (El-Haddad, Citation2019). Moreover, governments sometimes initiate and promote policy reforms to address demands, but fail to deliver (Houdret & Furness in this issue).

Quite often, though, authoritarian governments refuse even modest demands just to demonstrate their own power. If the demands are less modest, they are likely to refuse them anyway. Governments must see good reasons to change social contracts (Unsworth, Citation2003). In most cases, they ignore even mass protests and strikes (like in Jordan where demonstrations took place weekly near the prime minister’s office for almost a year and were tolerated by the regime), crack down on them (like in Iran in 2009, where large demonstrations called for a recount of the presidential election ballots) or increase general repression like in Bahrain after the 2011 uprisings (Josua & Edel, Citation2021).

5. Sudden change

If gradual change does not work, social contracts change only if something happens that shocks the entire system, for example, a significant change in the framework conditions, an unforeseen event or a foreign intervention. Events of this kind force at least one key actor in the country to react – most often the government – which sometimes even enjoys unusual freedom in deciding how to react – a situation considered by historical institutionalists as a critical juncture.

This holds for both democratic and authoritarian countries (Mahoney & Thelen, Citation2010). Russia’s war against Ukraine is an example of such an unforeseen event and its large impact on countries irrespective of their political system. In addition to forcing deep changes to the social contract in Ukraine, the war has brought about a radical turn in the defence, arms exports and energy policy of many European countries, and in the readiness of Poland and other countries to host refugees.

In authoritarian contexts, however, unforeseen events are more important for the change of social contracts because manifold obstacles hamper tangible gradual change. In some contexts, social contracts change only if something unexpected happens. Turkey’s constitutional reform in 2000, for example, came about only because of strict conditionality set by the IMF for a new loan. The government of Mozambique introduced a democratization process only after the end of the Soviet Union, which had backed the government for decades in its fight against the armed opposition.

Scholars working in the historical institutionalist tradition argue that sudden changes of this kind can happen even after long periods of structural continuity. During these periods, no party has sufficient freedom or interest in the revision of their previous decisions (Capoccia, Citation2016; Hall & Taylor, Citation1996; Pierson, Citation2004; Sanders, Citation2008; Steinmo, Citation2008). Every now and then, however, an event or a series of events – most often exogenous – change the options of one or more of the relevant actors (Capoccia & Keleman, Citation2007). For a limited time, they may have more freedom in their decision-making or face new pressure that forces them to react (Fiedler et al., Citation2020; Møller, Citation2013). These moments are, thus, windows of opportunity, in which the actors can influence the trajectory of their country (Capoccia, Citation2015). Governments can choose to reform or not, while societal actors can continue acting like before (e.g., acquiescing) or differently (e.g., protesting the government in order to improve their position in the social contract) (Khan, Citation2017). Israel and the Palestinians, for example, started peace talks in Oslo in 1993 only after the United States and Russia had put both sides under pressure in the aftermath of the Gulf War with Iraq. The pressure provided both with legitimation to take a step that they would never have taken otherwise.

Social contracts can change at these moments, but they do not have to. If they do, the change is often irreversible. Historical institutionalism associates the term critical juncture with these moments (Capoccia & Keleman, Citation2007). Mahoney defines critical junctures as ‘choice points that put countries (or other units) onto paths of development that track certain outcomes – as opposed to others – and that cannot be easily broken or reversed’ (Mahoney, Citation2001, p. 7).

Critical junctures are characterized by contingency, which brings about three problems. First, it is rarely possible to anticipate them because they arise typically from unforeseeable events. We usually learn about their existence at the earliest when a country has arrived at one of them. Second, we may fail to identify a critical juncture even if a country is in the midst of it. At these moments, any of the relevant actors may take an unexpected decision, for example, suddenly change its course, but it may also continue to act like before. Third, even if we know that a country has arrived at a critical juncture, we have difficulties predicting how the relevant actors are going to deal with it, because we lack information about their options for action, their preferences (Pierson, Citation2004) and their relative power position.

Critical junctures can come about by significant changes in the framework conditions, single events (sometimes with seemingly little meaning), the intervention of a foreign actor or a combination of these factors. A project funded by the former British Department for International Development funded project (2002–2005), which was meant to identify typical ‘drivers of change’ in different contexts, has found that these factors are in fact among the most common drivers of change (Leftwich, Citation2006; Unsworth, Citation2003):

A change in the framework conditions: The trigger can be (i) an external economic crisis as expression of in-built interdependencies and vulnerabilities in the globalized economy (e.g., a global energy or food price hike, a global interest rate jump, a sudden slump in important economic sectors such as tourism), (ii) an internal economic crisis (e.g., a bad harvest, collapse of the national currency), (iii) a pandemic, (iv) a natural disaster (earthquake, drought, river flood) or (v) an important event in a neighbouring country (such as Tunisia’s Yasmin Revolution that encouraged people in other Arab countries to protest).

The combination of a change in the framework conditions and a single event: Sometimes, structural factors trigger change in social contracts only in combination with a single event, which can be related or unrelated to the structural factor, as was the case in the Sudanese and Tunisian revolutions.

After 2011, Sudan was suffering severely from the secession of South Sudan, which had previously been the main source of foreign currency and energy on account of its large oil reserves. Per-capita income declined while energy and food prices exploded. And yet, the revolution happened only after the government devalued the local currency in 2018 – a decision taken in response to the structural economic problems of the country.

In Tunisia, in turn, changes were brought about by structural factors and a single, unrelated event. The country had been suffering for decades from declining real income levels and rising unemployment. However, the revolution broke out in late 2010 only after a street vendor – Mohamed Bouazizi – set himself on fire in response to the confiscation of his wares and the humiliation inflicted on him by municipal officers.

Single events alone: In other cases, social contracts change because of one single event. After Turkey’s failed coup in 2016, for example, President Erdoğan blamed the Muslim cleric Fethullah Gülen and his followers for the coup. Tens of thousands of people from the army, courts, the administration and academia were dismissed on the grounds of alleged sympathy with the Gülen movement; journalists and writers were imprisoned, newspapers and TV channels were closed. Since then, Turkey’s government relies not only on the social contract, but also on increasing repression to defend its rule (Kirişci & Sloa, Citation2019).

Sometimes, such single events appear at first to have no significance (Leftwich, Citation2006; Unsworth, Citation2003). Such an event can be a drought (e.g., fuelling the revolution in Syria in 2011) or the suicide of a single person (e.g., triggering the revolution in Tunisia in 2010).

At other times, significant events take place that are widely expected to drive change, but end up not having any major impact. The Beirut port explosion in August 2020 is an example in that regard. The tragedy was widely attributed to weaknesses in Lebanon’s social contract, and national and international figures stepped up to promise change. Thus far, Lebanon’s political elite have ridden out the initial pressure for change and continue to benefit from the status quo (Gabriel, Citation2022).

Intervention of a foreign actor: Change in social contracts can also arise from (i) military interventions (such as the US American invasion of Iraq), (ii) sanctions (such as the US sanctions against Iran) or (iii) credit conditionality (e.g., when the IMF forced Turkey in 2000 to better adherence to human rights standards and the privatization of state-owned enterprises). Lobbying of international organizations – a softer example of foreign intervention – can also trigger changes in social contracts if there is already a window of opportunity (Madi in this issue).

Each of the factors listed above can force one or more key actors to react. However, even at critical junctures, there are outer limits to the leeway of their decisions, as both historical institutionalism and the political settlement literature (e.g., Khan, Citation2017) stress. The latter, especially, suggests that the distribution of material and immaterial resources within a country is a key determinant of power relations. It impacts not only the outcome of negotiations between the main contracting parties, that is, the contents of the existing social contract, but also the rules of the game, that is, the negotiation process itself.

Therefore, the government reacts in most cases first. Sometimes, just one part of the government reacts – for example, because the president has died or fled (like in Tunisia in 2011). Quite often the army believes that it must react – sometimes for good reason (e.g., in order to protect public order) but more often to protect its privileges – and then either returns power quickly to a civilian government or seizes power itself (e.g., Nordlinger, Citation1976).

In many countries, the societal actors do not have enough power to react in the first place. However, the government might also not allow them to take decisions (even in democratic contexts) because it fears losing control of the speed or direction of change. Exceptions include separatist movements; very strong organizations, like the Tunisian General Labour Union (UGTT) in Tunisia; and political parties with strong backing, such as the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt until 2014.

In reaction to the above-mentioned factors, the key actor typically decides to decrease or increase the supply of one or more of its deliverables and, thus, changes the substance of the social contract. The government can decide to deliver more or less protection, provision or participation – which may affect the trust of society in the government and the readiness of people to pay taxes and invest in public goods. If, however, societal actors have the possibility to react first, they can express the decline of their loyalty to the government by street protests, open violence, the looting of shops (like in Iran in May 2022) or the refusal to pay taxes and fees.

In many cases, critical junctures involve also more than just one reaction. They trigger multi-stage processes in which sometimes even foreign powers get involved. If, for example, food prices rise steeply on world markets, such as after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, governments can react by liberalizing bread, rice and sugar prices as subsidies are no longer affordable. Society may react to this by demonstrating or looting, the government could crack down on the protests, and the international community may condemn the suppression of the protests, which encourages societal actors again to apply even more radical forms of resistance.

Likewise, several actors can react in parallel. shows that these processes are substantially different from the implicit and explicit negotiations described in Section 4, which lead to gradual changes in social contracts. While the negotiations are geared towards finding a new compromise, the reactions taken in response to unexpected, often negative exogenous shocks are unilateral decisions, which can easily lead to an escalation of conflict and a loss of control over the change process.

When no actor has reason or sufficient resources to react or re-react anymore, the country has reached a new equilibrium. This is when a new social contract can be said to have formed. From then on, all contracting parties will think twice before challenging the new arrangement, which implies that a new period of continuity and path dependency has begun (Mahoney, Citation2000) (see ).

6. Contributions to this special issue

The other articles in this special issue discuss in more detail when and why social contracts have changed in different MENA country contexts and what this means for the social contract concept as such.

Zintl & Houdret focus on digitalization as a driver of change in all elements of social contracts across the MENA region. Digitalization affects the deliverables of the state (e.g., increasingly efficient provision of services, better possibilities of participation and protection but also increased threats to security because of cyber criminality and digital surveillance) and the scope of social contracts (e.g., actors outside the country and previously marginalized actors within the country can be included). In any case, digitalization fundamentally alters not only the types of deliverables exchanged, the scope and actors of the social contract, but also the modes of interaction, which leads to changes in power relations relevant to the (re)negotiation of social contracts. Digitalization is thus a driver of change that may be less visible than other drivers, but nevertheless has potentially far-reaching impacts on the contract and related power-relations.

Rutherford argues that Egypt’s social contract changed significantly after General Al-Sisi’s rise to power in 2013. The government reduced both the substance and the scope of the social contract. This development raises several questions: Why was the al-Sisi regime able to alter the social contract in a manner unfavourable to society? And, why has this change not provoked widespread public anger and protests that would lead to rejection of the contract and, possibly, its revision? The answers lie in a change in the balance of power within the state in favour of the military, which has altered the elite coalition that underlies the regime; the segmentation of Egypt’s labour market into core insiders (the military and military-related firms), legacy insiders (state workers in the civil service and the public sector), and outsiders (in the informal sector); increased repression; new technologies to monitor society and dominate the public sphere; and robust international support. The most likely driver of future modifications to the social contract is change in the distribution of power within the military or between the military and the internal security apparatus.

Houdret & Furness analyse the potential of intermediary organizations as drivers of gradual change to the social contract in a society where the government is conscious of the need to carefully control reforms. Intermediary organizations created or revived by the Moroccan government in response to the claims expressed during the 2011 uprisings have varying mandates for articulating the need for governance reforms. The article shows that the Moroccan state has empowered intermediary organizations to act as conduits for change in specific areas, but it also retains the option to withdraw or restrict their mandates. This does not, however, prevent intermediary organizations from exploring the boundaries of their mandates, and taking opportunities or even risks to drive gradual change. In Morocco’s neo-patrimonial, bureaucratic and corporatist political system, informal networks are at least as important drivers of change as formal mandates. From an international cooperation perspective, intermediary organizations are an underutilized level of influence.

Sudermann & Zintl explore to what extent national narratives drive the renegotiation of social contracts and change them on both the national and the local level, sometimes even in a way that is unfavourable to society. This is definitely the case in war-affected Syria, where the social contract in the al-Asad-controlled territories systematically excludes parts of the population. Yet, the social contract is surprisingly stable and tacitly accepted by most of those who have not ‘exited’ it. The authors argue that this false stability is facilitated by a revanchist narrative that entails the adoption of exclusionary housing, land and property policies. Hence, newly codified norms authorize post-war destruction and subsequent reconstruction of entire neighbourhoods formerly held by supporters of the opposition, end up displaced from the social contract. As there are fewer recipients, the shrinking resources suffice to provide a minimum of state deliverables to loyalists and thereby stabilize a somewhat degenerated social contract.

Madi argues that social dialogue in Lebanon and Tunisia took diverging routes leading to a more participatory social contract in Tunisia, but not in Lebanon. The respective governments both faced a critical juncture and were more prone to act on international organizations’ calls for closer labour-state consultations. Yet, the Tunisian Labour Confederation pushed for a tripartite system and functioning social actor participation largely in line with International Labour Organization suggestions, while the Lebanese organized labour did not undergo such developments and only superficially acted on demands from the EU. In Tunisia, the national social dialogue institution was redesigned with the goal of boosting social actors’ participation in policymaking; in Lebanon, it was restored without addressing its structural shortcomings. The main explanatory factor is that the legacy of state-labour relations prior to the critical juncture shaped the role of labour after it. More specifically, the political intervention to neutralize labour differs between the two countries. Tunisia’s local unionists were less affected by the political intervention and became more independent post-2011, while unionists in Lebanon stayed part of sectarian and clientelist politics and, thus, were not actively pushing for further changes.

Abedtalas discusses whether and to what extent refugees’ entrepreneurship can be a driver of change in social contracts. Presenting the case of Syrian refugees in Iraqi Kurdistan, he argues that refugee entrepreneurs push for de-facto changes, especially for a de-clientelization of the social contract and how its deliverables are distributed. Yet, at several points they hit a glass ceiling and cannot achieve de jure change. While being a refugee limits one’s ability to influence change, being an entrepreneur opens up new opportunities to do so. Being both a refugee and an entrepreneur allows a person to navigate between the formal and informal rules of the game.

7. Conclusion

Social contracts are meant to provide a reasonable degree of certainty as to the expectations of government and societal actors regarding their respective rights and obligations towards each other. However, they need to be adjusted every now and then to take account of changes in the framework conditions, the relative strength of their parties, the expectations of these parties and the prevailing norms, values and ideologies. These adjustments can occur through explicit or implicit negotiations between the contracting parties or through an unexpected trigger. In the former scenario, change tends to be more controlled and gradual while in the latter it comes more abruptly: At least one contracting party is placed under so much pressure by a changes in the framework condition, an unexpected event, the intervention of an external power or a combination of these that it must react by either reinforcing the existing social contract or consciously deviating from it. In the follow-up, other actors may have to react to the first reaction, which may finally result in a cascade of reactions that can escalate conflicts.

In some authoritarian contexts, the first type of change is rare because there are no established mechanisms of social contract renegotiation. As a result, the second type of change is more common because the government has more negotiating power and can by fiat and repression reject the desire of society to alter the existing social contract. In addition, authoritarian countries often lack the institutions needed for a more explicit renegotiation of the social contract.

This analysis has implications for external actors willing to ease change in social contracts. They have three options. The first is to start a dialogue with the parties involved in a social contract, present the advantages of a gradual and Pareto-improving change, facilitate the negotiations between the parties, strengthen the negotiation positions of all and suggest policy fields where reform might be easy and beneficial for everybody. In these fields, they can underpin local priorities with international expertise.

The second option that foreign actors can take – if they have enough power – is to change the framework conditions of a country. Such pressure can be coercive, such as that induced through trade sanctions or military intervention, with the intention of opening critical junctures where the national actors must react. Alternatively, it can be supportive, such as the provision of food assistance, medical care or emergency relief, diplomatic or even military assistance (e.g., to governments facing external threats) or tailored support for potential agents of change within a country.

Third, once change is underway, external actors can provide incentives for all relevant domestic actors to continue and intensify their reform efforts. Examples are to formulate conducive conditionality for loans or to promise financial support after the finalization of legal or structural reforms. For external actors, the challenge is to understand quickly that a specific country is about to reach a branching moment in which political transformation is possible for a limited time.

First and foremost, however, external and domestic actors alike need to understand that a social contract’s stability depends on its ability to meet the expectations of all its contracting partners to the best possible degree.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. There can also be sub-national social contracts (like in Iraqi or Syrian Kurdistan), transnational social contracts (such as the so-called Islamic State ruling over parts of Syria and Iraq for a while) and supra-national social contracts (such as the European Union).

2. Egypt, for example, amended its constitution in 1980 and announced, ‘Sharia is the principal source of legislation’, cf. Berger and Sonneveld (Citation2010). Likewise, Sudan Islamized its legislation in 1983, as did Malaysia between 1984 and 1994, cf. Köndgen (Citation2010).

3. Other authors distinguish between parametric and systemic changes and between reformative and transformational changes (e.g., Sztompka, Citation1993, pp. 19–20).

References

- Abdalla, N. (2023). The social contention over a new labour law in post- 2014 Egypt: Understanding regime choices and strategies, mediterranean politics, online first. Retrieved May 1, 2023 from https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2023.2207432

- Al-Razzaz, O. (2013). The treacherous path towards a New Arab social contract. Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs. Retrieved January 17, 2024, from https://www.aub.edu.lb/ifi/Documents/public_policy/other/20131110_omar_razzaz_paper.pdf

- Anderson, G., & Choudhry, S. (2015). Constitutional transitions and territorial cleavages. International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance. https://www.idea.int/sites/default/files/publications/constitutional-transitions-and-territorial-cleavages.pdf

- Berger, M., & Sonneveld, N. (2010). Sharia and national law in Egypt. In J. Otto (Ed.), Sharia incorporated: A comparative overview of the legal systems of twelve Muslim countries in past and present (pp. 51–88). Leiden University Press.

- Bogaert, K., & Emperador, M. (2011). Imagining the state through social protest: State reformation and the mobilizations of unemployed graduates in Morocco. Mediterranean Politics, 16(2), 241–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2011.583741

- Capoccia, G. (2015). Critical junctures and institutional change. In J. Mahoney & K. Thelen (Eds.), Advances in comparative-historical analysis (pp. 147–179). Cambridge University Press.

- Capoccia, G. (2016). When do institutions “bite”? Historical institutionalism and the politics of institutional change. Comparative Political Studies, 49(8), 1095–1127. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414015626449

- Capoccia, G., & Keleman, D. (2007). The study of critical junctures. World Politics, 59(3), 341–369. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0043887100020852

- Cassani, A. (2017). Social services to claim legitimacy: Comparing autocracies’ performance. Comtemporary Politics, 23(3), 348–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2017.1304321

- Cook, L., & Dimitrov, M. (2017). The social contract revisited: Evidence from communist and state capitalist economies. Europe-Asia Studies, 69(1), 8–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2016.1267714

- Devarajan, S. (2015). An exposition of the new strategy: Promoting peace and stability in the Middle East and North Africa. The World Bank. Retrieved January 17, 2024, from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/23773

- El-Haddad, A. (2019). The minimum wage curse: Why El-Sisi’s decision to raise Egypt’s minimum wage is not such a good one! German Development Institute. Retrieved January 17, 2024, from https://www.idos-research.de/uploads/media/German_Development_Institute_El_Haddad_15.04.2019.pdf

- El-Haddad, A. (2020). Redefining the social contract in the wake of the Arab Spring: The experiences of Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia. World Development, 127, 104774. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104774

- Feldmann, M., & Mazepus, H. (2018). State-society relations and the sources of support for the Putin regime: Bridging political culture and social contract theory. East European Politics, 34(1), 57–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2017.1414697

- Fiedler, C., Grävingholt, J., Leininger, J., & Mross, K. (2020). Gradual, cooperative, coordinated: Effective support for peace and democracy in conflict-affected states. International Studies Perspectives, 21(1), 54–77. https://doi.org/10.1093/isp/ekz023

- Gabriel, E. (2022). After two years, Lebanon has done nothing in response to the port of Beirut blast. Wilson Center. Retrieved January 17, 2024, from https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/after-two-years-lebanon-has-done-nothing-response-port-beirut-blast

- Green, D. (2016). How change happens. Oxford University Press.

- Hall, P., & Taylor, R. (1996). Political science and the three new institutionalisms. Political Studies, 44(5), 936–957. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.1996.tb00343.x

- Heydemann, S. (2021). Rethinking social contracts in the MENA region: Economic governance, contingent citizenship, and state-society relations after the Arab uprisings. World Development, 135, 105019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105019

- Hinnebusch, R. (2020). The rise and decline of the populist social contract in the Arab world. World Development, 129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104661

- Hirschman, A. (1970). Exit, voice and loyalty. Responses to decline in firms, organizations and states. Harvard University Press.

- Hobbes, T. (1651). Leviathan. Penguin Books, reprint 1985.

- Josua, M., & Edel, M. (2021). The Arab uprisings and the return of repression. Mediterranean Politics, 26(5), 586–611. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2021.1889298

- Kaplan, S. (2015). Fixing fragile states: A country-based framework. Norwegian Peacebuilding Resource Centre. Retrieved January 17, 2024, from https://www.shareweb.ch/site/DDLGN/Documents/2e81146a49414991579d841ab4a44532.pdf

- Kaplan, S. (Ed.). (2017). Inclusive social contracts in Fragile States in transition: Strengthening the building blocks of success. Institute for Integrated Transitions. Retrieved July13, 2024, from https://ifit-transitions.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Inclusive-Social-Contracts-in-Fragile-States-in-Transition-Strengthening-the-Building-Blocks-of-Success.pdf

- Khan, M. (2017). Political settlements and the analysis of institutions. African Affairs, 117(469), 636–655. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adx044

- Kinninmont, J. (2017). Vision 2030 and Saudi Arabia’s social contract: Austerity and transformation. Chatham House. https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/publications/research/2017-07-20-vision-2030-saudi-kinninmont.pdf

- Kirişci, K., & Sloa, A. (2019). The rise and fall of liberal democracy in Turkey: Implications for the west, policy brief. Brookings. Retrieved January 17, 2024, from https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/FP_20190226_turkey_kirisci_sloat.pdf,

- Köndgen, O. (2010). Shari‘a and national law in the Sudan. In J. Otto (Ed.), Sharia incorporated: A comparative overview of the legal systems of twelve Muslim countries in past and present (pp. 181–230). Leiden University Press.

- Leftwich, A. (2006). Drivers of change: Refining the analytical framework. University. Retrieved March 6, 2023, from https://www.gsdrc.org/docs/open/doc103.pdf,

- Leininger, J., Burchi, F., Fiedler, C., Mross, K., Nowack, D., von Schiller, A., Sommer, C., Strupat, C., & Ziaja, S. (2021). Social cohesion: A new definition and a proposal for its measurement in Africa. German Development Institute. https://www.idos-research.de/uploads/media/DP__31.2021.v1.1.pdf

- Locke, J. (1689). Two treatises of government. Yale University Press, reprint 2003.

- Loewe, M., & Albrecht, H. (2023). The social contract in Egypt, Lebanon and Tunisia: What do the people want? Journal of International Development, 35(5), 838–855. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3709

- Loewe, M., El-Haddad, A., & Zintl, T. (2024). Operationalising social contracts: Towards an index of government deliverables. IDOS Discussion Paper 8/2024. German Institute of Development and Sustainability (IDOS). https://doi.org/10.23661/idp8.2024

- Loewe, M., Zintl, T., & Houdret, A. (2021). The social contract as a tool of analysis: Introduction to the special issue on “framing the evolution of new social contracts in Middle Eastern and North African countries”. World Development, 145, 104982. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.104982

- Mahmoud, Y., & Súilleabháin, A. (2020). Improvising peace: Towards new social contracts in Tunisia. Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding, 14(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/17502977.2019.1629377

- Mahoney, J. (2000). Path dependence in historical sociology. Theory & Society, 29(4), 507–548. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007113830879

- Mahoney, J. (2001). The legacies of liberalism: Path dependence and political regimes in Central America. John Hopkins University Press.

- Mahoney, J., & Thelen, K. (2010). A theory of gradual institutional change. In J. Mahoney & K. Thelen (Eds.), Explaining institutional change: Ambiguity, agency, and Power (pp. 1–37). Cambridge University Press.

- McCandless, E. (2018). Forging resilient social contracts: A pathway to preventing violent conflict and sustaining peace. United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved January 17, 2024, from https://socialcontracts4peace.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/RESILIENT-SOCIAL-CONTRACTS-FINDINGS-30-Sept-2018.pdf,

- Møller, J. (2013). When one might not see the wood for the trees: The ‘historical turn’ in democratization studies, critical junctures, and cross-case comparisons. Democratization, 20(4), 693–715. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2012.659023

- Nordlinger, E. (1976). Soldiers in politics: Military coups and governments. Prentice Hall.

- Pierson, P. (2004). Politics in time: History, institutions, and social analysis. University Press.

- Rousseau, J.-J. (1762). Du contrat social ou principes du droit politique. Retrieved January 17, 2024, from http://classiques.uqac.ca/classiques/Rousseau_jj/contrat_social/Contrat_social.pdf

- Rutherford, B. (2018). Egypt’s new authoritarianism under al-sisi. The Middle East Journal, 72(2), 185–208. https://doi.org/10.3751/72.2.11

- Sanders, E. (2008). Historical institutionalism. In S. Binder, R. A. W. Rhodes, & B. A. Rockman (Eds.), The oxford handbook of political institutions (pp. 39–54). Oxford University Press.

- Steinmo, S. (2008). What is historical institutionalism? In D. Della Porta & M. Kaeting (Eds.), Approaches in the social sciences (pp. 150–155). Cambridge University Press.

- Stone, P. (2014). Social contract theory in the global context. Law, Ethics and Philosophy, 2(15) , 177–189. https://www.raco.cat/index.php/LEAP/article/view/297565

- Streeck, W., & Thelen, K. (2005). Introduction: Institutional change in advanced political economies. In W. Streeck & K. Thelen (Eds.), Beyond continuity: Institutional change in advanced political economies (pp. 1–39). Oxford University Press.

- Sztompka, P. (1993). The sociology of social change. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Unsworth, S. (2003). Better government for poverty reduction: More effective partnerships for change. Department for International Development. Retrieved January 17, 2024, from http://www2.ids.ac.uk/gdr/position%20papers/Unsworth.pdf

- Vidican Auktor, G., & Loewe, M. (2022). Subsidy reform and the transformation of social contracts: The cases of Egypt, Iran and Morocco. Social sciences, 11(2), 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11020085

- Weale, A. (2013). Democratic justice and the social contract. Oxford University Press.

- Weipert-Fenner, I. (2023). Budget politics and democratization in Tunisia: The loss of consensus and the erosion of trust. Mediterranean Politics, 1–21. Retrieved May 10, 2023, from https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2023.2207429

- World Bank. (2004). Unlocking the employment potential in the Middle East and North Africa: Toward a new social contract. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Yousef, T. (2004). Development, growth and policy: Reform in the Middle East and North Africa since 1950. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 18(3), 91–116. https://doi.org/10.1257/0895330042162322