ABSTRACT

In 2021, King Mohammed VI’s appointed commission released a new vision for Moroccan state-society relations: the New Development Model (Nouveau Modèle de Développement, NMD). Presented as a ‘national collective and federative project’, it entailed a social protection system called a ‘social pact’ or ‘social contract’. The King’s vision articulated in the NMD promises changes that many Moroccans have long been calling for. The government has created several intermediary organizations mandated to work on reforms, which reflect citizens’ expectations but keep the pace of change under control. From an international cooperation perspective, these bodies are potential partners for reforms and achieving common development objectives. This article addresses two related questions: what scope of action do Moroccan intermediary organizations have to press for changes to the social contract under the NMD? Do they require international support in fulfilling their roles as change makers? Our analytical framework is based on scholarship exploring political settlements and institutional mandates in neo-patrimonial political systems. We focus on three intermediary organizations relevant to the deliverables of the social contract and discuss the extent to which they push the limits of their mandates to facilitate change. We then turn to the support that international development cooperation could provide.

Introduction

In 2021, King Mohammed VI’s appointed commission released a new vision for Moroccan state-society relations: the New Development Model (Nouveau Modèle de Développement, NMD).Footnote1 The NMD was partially a response to discontent about the failure to implement reforms promised in 2011, when the Arab Uprisings brought down several governments across the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. The NMD presents the basis for a new social contract in Morocco: a ‘national collective and federative project’, entailing a ‘national development pact’ and an improved social protection system called a ‘social pact’ or ‘social contract’ (CSMD, Citation2021).

Intermediary organizations are key conduits for realizing the King’s vision. In Morocco’s centralized and authoritarian political system – which has been under pressure due to socio-economic inequalities and repression – intermediary organizations address state authorities’ need to legitimize top-down decisions. In some cases, they have the capacities and even the mandate to articulate bottom-up demands for change. Despite their key role in Morocco, the potential of intermediary organizations as partners for international cooperation has to date not been fully explored.

We understand intermediary organizations as official bodies with a bureaucratic structure and a mandate granted by a sovereign authority to coordinate between societal systems and channel dissent in a specific sector. We distinguish ‘organizations’ from ‘institutions’ (or ‘regimes’), which we understand as sets of rules and norms that govern behaviour (Young, Citation1986). We assess the scope for intermediary organizations to act as drivers of change in the implementation of the NMD and thereby to Morocco’s social contract. We focus on the levers of change and the Moroccan government’s and King’s interest in controlling the pace and the extent of change. We discuss the NMD’s international implications, particularly with regard to areas in which Morocco may benefit from partners’ support to deliver on the governance-related promises made in the NMD. In order to better understand the organizations’ potential for supporting change, we raise two questions:

What potential for facilitating change do intermediary organizations have in the context of Morocco’s NMD, and how do they exercise this role?

What potential is there for Morocco’s intermediary organizations to receive international support for fulfilling their mandates as change makers?

In order to address these questions, we develop an analytical framework based on historical institutionalist literature on incremental change and political settlements (Capoccia, Citation2016; Khan, Citation2017). We complement this with some observations from literature on neo-patrimonialist development models (Mkandawire, Citation2015) and state corporatism (Hinnebusch, Citation2015). These insights help us assess the scope for intermediary organizations in driving change in the social contract model as conceptualized by Loewe et al. (Citation2021, for further conceptualization see also the introductory article to this issue). In discussing the situation in Morocco, we draw on qualitative interviews conducted in autumn 2022 with 20 representatives from the three selected intermediary organizations, development agencies, think tanks and civil society organizations.Footnote2

Intermediary organizations fulfil an important role in the social contract: the state must deliver ‘3Ps’ – protection, provision and participation – to the population. In return, the people grant their loyalty, their taxes and their contributions to public life (Loewe et al., Citation2021). The state can empower intermediary organizations to act as conduits for change in specific areas, often as a response to social pressure. But it also retains the option to withdraw or restrict their mandates. This does not, however, prevent intermediary organizations from exploring the boundaries of their mandates, and taking opportunities or even risks to drive change (Khan, Citation2017). For citizens, intermediary organizations can protect their interests and security, provide services and create spaces for political participation.

Intermediary organizations have become an interesting, but underexplored, topic for research (Kjaer, Citation2015). The peacebuilding literature has analysed the important role of intermediary organizations in sustainably transforming state-society relations (Bächler, Citation2004; McCandless, Citation2018) and highlighted the mediation and conflict prevention capacities they can support in societies (Lederach, Citation2002). In development cooperation with authoritarian countries, cooperation with the central state can be difficult. Intermediary organizations can therefore provide for a viable option for support from international actors, particularly in cases where there is an interest in renegotiating aspects of the social contract (Paulo & Klingebiel, Citation2016).

The rest of this article is organized as follows. The next section sets out our understanding of the role of intermediary organizations in driving change in the social contract and of development cooperation in this context. The third section analyses the roles of three key intermediary organizations in Morocco, focussing on their roles as conduits between state and society, and their scope to act as changemakers: The Conseil Economique, Social et Environnemental (Council for Economic, Social and Environmental Affairs, CESE); the Instance Nationale de la Probité, de la Prévention et de la Lutte contre la Corruption (National Authority for Probity and the Prevention and Fight against Corruption, INPPLC); and the Conseil National des Droits de l´Homme (National Human Rights Council, CNDH). On this basis, we identify possible opportunities for, and limits to, external support. The final section concludes, returning to our two questions.

The role and scope of action of intermediary organizations in changing social contracts

This section outlines the ways in which intermediary organizations can influence state-society relations and their scope of action. We discuss their potential role in transformation processes in Morocco, and their relevance for international development cooperation.

Neo-patrimonial, corporatist political systems are resistant to change, even when they have complex bureaucracies and private sectors with varying degrees of autonomy (Hinnebusch, Citation2015). It is difficult to convince an established political elite to give up their power and privileges in favour of a more inclusive system, and virtually impossible for outsiders to incentivize change (Bodenstein & Furness, Citation2009; Schlumberger, Citation2008). As noted by Snyder and Mahoney (Citation1999), change in neo-patrimonial systems often results from popular protest or even revolution. Such events invariably unleash forces that are difficult to control, meaning that outcomes are highly uncertain and damage is difficult to repair (Loewe et al, this special issue).

Incremental change is nevertheless possible, even in authoritarian contexts (Mahoney & Thelen, Citation2009). Different state and non-state actors can play important roles in responding to pressure for reform. Government ministries, municipalities, central banks, regulators, business groups, trade unions, lobbyists, or civil society actors, may all contribute to political transformation. This is particularly true for organizations created by the state to perform a specific reform function at the interface of state and society (Khan, Citation2017). Often created by governments as a response to socio-political pressure, these intermediary organizations are institutionalized channels of interest articulation and, implicitly and to varying degrees, of negotiation between state and society. They can contribute to changing social contracts by shaping the ‘rules of the game’ and thereby influencing outcomes: the state’s deliverables (protection, provision, participation) and, in return, the government’s legitimacy (Loewe et al., Citation2021).

Research on social contracts in conflict-affected societies confirms the important role of intermediary organizations as ‘social contract-making mechanisms’ (McCandless, Citation2018), which should respond to core conflict issues such as social polarization and economic exclusion (Mahmoud & Ó Súilleabháin, Citation2020). In this context, intermediary organizations provide institutionalized forums and processes for interaction between state/government and society on the development and implementation of reforms. Intermediary organizations are responsible for specific sectors and can thereby influence change relating to one or more of the ‘3Ps’, and therefore the overall evolution of the social contract.

illustrates how intermediary organizations may moderate a changing state-society social contract. suggests that the social contract is the dependent variable. Intervening variables that can play a defining role include the Moroccan state and the King, the government, Moroccan society, and international actors. does not imply that the Ps are delivered exclusively via intermediary organizations. Many aspects of protection, such as policing, are delivered directly by the state. For our purposes, we situate the independent variable at the level of intermediary organizations, which in the Moroccan case are actors tasked by the government to advance the NMD. indicates that although the social contract is a national process, and central aspects are not decided by outsiders, international cooperation can create incentives and support processes and actors relevant to the 3Ps (Loewe et al., Citation2021). We are interested in two aspects: the extent to which intermediary organizations can be agents of change, and the extent to which international actors can influence/support them.

The scope of action of intermediary organizations

After outlining the potential role of intermediary organizations in changing social contracts, we now turn to factors that may influence their scope of action. The literature on political settlements, transformation, state corporatism and neo-patrimonial governance provides many entry-points for the analysis of intermediary organizations. Given our focus, two sets of factors discussed in the literature are relevant: the organizations’ ability to influence the ‘rules of the game’, and their ability to act as intermediaries between state and society.

The organizations’ impact on the ‘rules of the game’ indicates their influence on political transformation processes (Khan, Citation2017). This capacity is related to the organizations’ mandates and resources, which influence their capabilities and their ability to change resource allocation (both material and immaterial) (Li, Citation2022). One possibility for an organization to impact resource allocation is improving checks and balances, which affect the distribution of rents and power. Next to their official mandates and resources, intermediary organizations also require political backing from high-level authorities. In an authoritarian system especially, the most powerful actors must support a particular policy or institution, the mere existence of which is no guarantee of success.

Intermediary organizations are established for a particular purpose and are responsible for reaching outcomes in specific policy areas. In practice, intermediary organizations do not have clear cut mandates but rather overlap, meaning one intermediary organization may influence all three Ps, or several organizations may contribute to changes in one P. It is therefore likely that in carrying out their mandate, for example to set out ways in which more provision could be realized, an organization will point out that more protection and/or participation are also needed. In this way, intermediary organizations interact and reinforce each other in identifying, conducting and managing changes in the social contract.

A second set of factors determining the organizations’ impact is their ability to act as an intermediary between government and society. In periods of political transformation, intermediary organizations can be powerful change agents that negotiate and implement reforms (Kjaer, Citation2015). How intermediary organizations exercise their agency is a key factor in determining whether policies and regimes will be successful, and whether a window of opportunity will become a critical juncture in a change process or not. As discussed below, least three main factors influence the organizations’ ability to act as an intermediary: first, their ability to integrate different constituencies and build alliances; second, their ability to propose and implement processes and rules for state-society interaction; and third, their capacity to identify joint interests and identities based on shared norms and culture.

Intermediary organizations can become institutionalized channels of interest representation and thus help moderate the inevitable conflicts that change entails. As Mahoney and Snyder (Citation1999, p. 17) put it: ‘Political institutions are meso-structures that stand between actors and macro-level structures’. They are invariably close to the government and therefore usually not neutral mediators. Nevertheless, they cannot be considered proponents of the regime either, as the heads of such organizations are carefully selected in response to public protest and/or to integrate potential opponents. As Volpi (Citation2017) points out, long-term relations between political elites and the opposition are fundamental to understanding how authoritarian regimes in the region maintain power. In Morocco, while this strategy has a long tradition, these choices do not always lead to an ‘authoritarian upgrade’ (Heydemann, Citation2019). Outcomes are never certain and the organizations’ impact on political transformation varies from case to case and over time. One important factor is the organizations’ ability to integrate constituencies from both the state and society, which in turn target organizations as potential mechanisms for making changes (Lieberman, Citation2002; Rojas & King, Citation2018).

Intermediary organizations can help build alliances between popular protest and regime incumbents, for instance by elaborating rules and processes for their interaction. The organizations’ ability to identify joint interests and identities based on shared norms and culture play an important role in this regard (Snyder & Mahoney, Citation1999). The organizations’ task is thus not only about mediating between different interests and constituencies, but also entails mediating between different identities and contributing to elaborate a new joint vision (Snyder and Mahoney, Citation1999, p. 113). The text of Morocco’s NMD strongly reflects these normative elements when calling for and outlining the pillars of a new vision for state-society relations.

Why this framing is appropriate in the Moroccan context

Morocco’s political system is formally dominated by the King who, even in the post 2011-constitution, keeps direct control over several ministries, influential state institutions and important economic sectors (Mohsen-Finan, Citation2013). His power is embedded into what Hibou and Tozy (Citation2020) call a combination of governance modes including elements of both the imperial register and the nation-state. The monarchy draws on several sources of legitimacy – including the king’s official status as religious leader – which define the particular nature of Morocco’s patrimonial system beyond its formal and juridical aspects (Saaf, Citation2015).

The Moroccan monarchy has kept ahead of social tensions by making tactical reforms that promote greater prosperity and freedoms, but which do not affect levers of power in the country (Desrues, Citation2020). Even prior to the Arab Uprisings, external observers sometimes viewed Morocco as a successful example of change towards more democratic governance (D. Maghraoui, Citation2009). The transition from widespread street protests in early 2011 to the adoption of a new constitution later the same year was relatively smooth. However, the more participative governance structures promised in the constitution did not fully materialize (Akesbi, Citation2014), such as decentralization (Houdret & Harnisch, Citation2018) or citizen participation (Iraki & Houdret, Citation2021). Reforms even became instruments of more centralized, non-transparent and authoritarian governance (Bergh, Citation2017).

Throughout Morocco’s recent history, intermediary organizations have played an important role in reforms, although actors have played their roles differently. The strategy of political co-optation largely practiced in Arab countries (Bank, Citation2004) including in Morocco under late King Hassan II did not fundamentally alter the distribution of power and the monarch’s dominance, but it is considered as a trigger of change towards today’s multiparty system with changing coalitions (A. Maghraoui, Citation2001). In this tradition of inclusion and co-optation that dates back to post-colonial times (Hibou, Citation2006; Tozy, Citation1991), the monarchy regularly creates advisory councils that carefully mix personalities from public and private institutions, thereby blurring the lines between formal and informal modes of governance. After the Arab uprisings, King Mohammed VI created several commissions representing different social groups to elaborate reform proposals, such as the commission for the elaboration of a new constitution and the one for the NMD. The nomination of critical experts in these commissions may be seen as an aspect of the co-optation strategy.

The deterioration of human rights and press freedoms coincided with tight political control during the COVID 19-pandemic with emergency laws, extrajudicial tools and strengthened digital surveillance (Chahir, Citation2020). The already high inequalities between Morocco’s poor and rich citizens widened further during the pandemic with repercussions for education, health, and income. According to one estimation, seven years of progress in fighting inequality has been lost (HCP, Citation2022). The NMD was (unlikely by chance) presented at an appropriate moment for the announcement of a new vision and reforms, a few weeks before the 2021 general election and during a lull in the pandemic.

King Mohammed VI has subsequently praised the NMD in several speeches, but has not offered guidance on how it should generate a political transformation process (interview 6). What was to become a new social contract so far seems to be reduced to social protection reform. While it is still too early to know the outcome of this process, it is significant that the NMD report openly admits serious development constraints and governance deficits. Intermediary organizations will be key in addressing these issues. Their scope of action and potential role in political transformation is therefore of major importance to the Moroccan social contract, and to external support for change in the country.

Morocco’s new development model and the social contract: the role of intermediary organizations as potential change agents

This section discusses the importance of changes in state-society relations to the NMD and the potential role of the three selected organizations in facilitating change.

Social contract and social change in the NMD

The Commission appointed for the elaboration of the NMD consisted of its president and 35 members including high-ranking representatives from civil society, academia and business, former ministers, a former prime minister, a former adviser to the king, and well-known, critical intellectuals. Some of its members had already contributed to the elaboration of the 2011 Constitution. The NMD aims to support the 2011 Constitution, promising the right to health care, social protection and medical coverage, as well as equal access to these rights for all (CSMD a, Citation2021). The Commission’s report points out the need for a joint and inclusive approach by the whole nation, backed by a common identity rooted in culture and religion, and the leadership of King Mohammed VI. The report details the roles of different institutions and actors such as civil society, the private sector and the administration, and it frequently refers to the importance of rights and duties in the sense of a new social contract.

The Commission addresses the need for improved state-society relations, referring to better social cohesion and a renewed ‘social pact’. The report raises concerns about each of the social contract’s three dimensions of protection, provision and participation. It explicitly refers to the role of public administration and the need for citizens’ trust, and considers reform of the social security system as a key step. The authors openly point to governance deficits, deep frustration and public distrust:

Within the upheaval that the region has seen in 2011, the Kingdom was able to offer hopeful answers to popular and political expectations. However, as economic growth slowed down and inequalities continued to rise, a climate marked by deteriorating trust has since prevailed in the country. Many reforms announced at the highest level of the State (economic transformation, education and training, healthcare and social protection, preservation of natural resources or regionalization …) are lagging behind as resistance to change slows down the pace of progress. As a result, these reforms fail to produce the level of impact that is expected of them, leaving citizens’ hopes disappointed and feeding growing mistrust towards public action. (CSMD, Citation2021, p. 7)

A closer analysis of the reforms proposed in the NMD raises questions about the governance structure, its financing and implementation, and its democratic legitimacy. The text points out the need for a joint and inclusive approach by the whole nation but clearly highlights the leadership of King Mohammed VI. The parliament approved the NMD, written by an appointed but not elected commission, without debate. Some observers consider the NMD as a ‘safety net’ for the monarchy (Chahir, Citation2021), and the dominant role of the King in strategic decisions and oversight is anchored in the commission’s report (CSMD, Citation2021, p. 9). The report clearly points to the need for change in terms of the participation and inclusion of citizens, social justice, economic growth, sustainable development and education (addressing the 3 Ps). In many of these areas, intermediary organizations have mandates to contribute to reforms (Zine, Citation2021, interview 5).

The scope of action for intermediary organizations in Morocco

In order to analyse the roles and scope of action for intermediary organizations in changing the social contract, we focus on three agencies, each with its mandate in a particular sector:

The Conseil Economique, Social et Environnemental (Council for Economic, Social and Environmental Affairs, CESE);

The Instance Nationale de la Probité et de la Prévention et de la Lutte contre la Corruption (National Authority for Probity and the Prevention and Fight against Corruption, INPPLC)

The Conseil National des Droits de l’Homme (National Human Rights Council, CNDH)

The NMD report acknowledges the fundamental role of the 2011 Constitution for the model. It also refers explicitly to the contribution of all three intermediary institutions for its implementation (p. 69), even pointing out that reforms are needed if they are to function adequately.

All three intermediary organizations are close to the Moroccan state, in the sense that they are public institutions headed by well-known personalities with affiliations to and careers in the political system. They are, however, not state agencies. They have been created or revived in response to public grievances expressed on the streets, and thus have potentially important roles as intermediaries between state and society in facilitating political transformation. As such, they can contribute to developing and sometimes implementing new policies for more inclusive and transparent governance in different sectors, supporting a system of checks and balances, and thereby to shaping ‘the rules of the game’. They can also act as conduits for social movements that target organizations as potential mechanisms for making changes (Rojas & King, Citation2018). Consequently, these three intermediary organizations may be promising partners for international cooperation to support change processes.

The creation of the CESE was envisaged in the 1996 constitution, but only materialized after the 2011 protests. Its mandate is to provide evidence-based policy advice and to give voice to different segments of society, thereby creating space for an institutionalized state-society dialogue. CESE’s 105 members consist of five categories of persons: 24 experts (nominated by the king); 24 representatives of trade unions; 24 representatives of professional organizations and associations; 16 representatives of civil society, and 17 other representatives of key institutions such as other intermediary organizations including the CNDH, the National Bank or the National Planning Authority. The government can commission reports to CESE (32 at the time of writing this article), but CESE can also decide independently to work on a certain topic (74 ‘auto-saisine’ reports have been published at the time of writing this article). CESE has made extensive use of this option during periods where the government was reluctant to commission studies for various reasons, including party politics (interviews 4, 5). In addition, CESE’s uses its annual reports to highlight crucial reform needs. CESE is part of an international network of economic and social councils, and chair of the African Assembly of Councils. It is a well-resourced and equipped organization that does not receive any external financial support (interview 3). The council’s members are not remunerated, but the experts who produce the reports are paid for their research (interviews 3, 4).

CESE works on a broad range of topics including commissioned studies on economic and fiscal reforms, land and real estate, decentralization or rural development. Many of the topics the council itself chooses to work on focus on rights and the empowerment of marginalized groups. In some cases, the council has been asked to develop draft laws for topics it had published reports on, such as for the rights of people with disabilities, work accidents and youth integration, but also laws for the creation of new inclusive and participatory institutions such as for a National Council for Social Dialogue (interviews 4, 3). CESE has promoted dialogue platforms between different societal constituencies, including in the NMD. In 2018, former president Nizar Baraka called for a new social contract (CESE, Citation2018).

Given the range of topics CESE works on, its role cannot be limited to just one dimension of the social contract. Its work relates more to the deliverables of ‘provision’ (public services, economic development) and ‘participation’ (representation of different groups and their interests, suggestions for and implementation of national dialogue formats), than to ‘protection’. CESE has not focussed much on national security issues or on human rights, with the exception of rights-based approaches in the fields of gender, children, and people with disabilities.Footnote3 In the same year as the new constitution was enacted, the CESE published a concrete proposal for a new ‘social pact’ outlining rights and obligations on the basis of international norms (CES, Conseil Economique et Social, Citation2011). Its 2019 report on the NMD highlights Morocco’s successes but is also openly critical of its development path (CESE, Citation2019).Footnote4

CESE benefits from credibility acquired over time, and is able to articulate criticism towards public authorities and decision-makers while picking up topics of public concern (interviews 3, 4, 6). The use of digital tools in some cases enables participation by social groups underrepresented in public discourse, such as youth or the diaspora (see Zintl/Houdret in this issue). CESE’s reports are presented to a wide public audience, sometimes in the presence of ministers. The media pick up key messages and articulate claims for accountability towards the government. However, according to interviewees, such reforms could only be pushed when there was political momentum, for instance when CESE members moved to new functions in the government (interview 4, 5). CESE’s main strengths include its broad and diverse membership and thus its network, which can potentially mobilize support for reform in all three Ps. According to interviewees, CESE’s informal networks enable it to obtain the data it needs from public authorities for its analyses, even in difficult cases (interviews 3, 4).

CESE is a platform for negotiating interests that may contribute to creating political consensus on reforms. It has been quite influential in the design of reforms, such as the fiscal and pension reforms, the decentralization reform, or, more recently, the reform of the water sector. Nevertheless and despite its critical reports, CESE’s scope of action regarding the choice of topics, the design of the proposed reforms and the representation of stakeholders outside the political establishment are limited (interviews 4, 6, 8). Furthermore, CESE has only a consultative mandate, and although it has pushed intelligently for higher attention and related public pressure on the government, the scope and the implementation of reforms ultimately lies with the top levels of the state and government. According to interviews, the process via which CESE’s members are designated does not leave much room for critical voices (interviews 6, 8, 10). The civil society representatives, for example, are designated by elected bodies. CESE’s consensual approach may help developing feasible political recommendations, but also limits voices from outside the political establishment. As interviews confirmed, very sensitive topics, including some human rights issues or corruption in sectors controlled by the state elite, are (probably deliberately) not in CESE’s focus (interviews 6, 10); this may be linked to what Vairel (Citation2022) calls ‘self-limiting mobilization’, i.e., self-censorship.

The anti-corruption organization INPPLC was renamed in 2015, based on the Instance Centrale de Prévention de la Corruption created in 2007. Its activities increased after the 2011 protests and the promises for fighting corruption enshrined in the new constitution (El Mesbahi, Citation2013). Nevertheless, the necessary law for the functioning of the Authority was adopted only after two years of intense lobbying by the organizations’ president Bachir Rachdi (interview 10). Interviewees noted that Rachdi’s appointment in 2019 improved the INPPLC’s legitimacy after it had struggled for several years to fulfil its mandate (interviews 10, 15).Footnote5 In October 2022, more than three and a half years after Rachdi’s nomination, the King officially nominated the INPPLC’s council members and its Secretary General.

The Council is composed, in addition to its president, of twelve members chosen ‘among personalities enjoying experience, expertise and competence … and who are known for their integrity, their impartiality, their uprightness and their probity’.Footnote6 Four members are appointed by the king, four by the head of government, two by the President of the House of Representatives, and two others by the President of the House of Councillors, respecting the principle of parity.

NGOs have complained that the INPPLC’s mandate does not foresee any formalized interaction with civil society actors (Berrada, Citation2021, interview 10). Nevertheless, the INPPLC meets our definition of ‘intermediary organization’ as it is both embedded in governmental processes and interacts with society. The organization interacts with citizens via electronic platforms providing information and enabling people to raise their concerns. Citizens can submit legal claims, inform about corruptive activities, and submit whistleblower tips. Further channels for interaction include partnerships with the private sector and participatory events for the broader public, such as book fairs. A dedicated internal department ‘media, civil society and citizens’ is responsible for these activities. At the same time, INPPLC is involved in the implementation of government policies, such as the action plan of the Open Government Programme and the implementation of the right to access information. It also partners with other government institutions, including the High Authority for Audiovisual Communication, and organizes joint events to communicate relevant topics to society.

The INPPLC’s mandate includes initiating, coordinating, supervising and monitoring the implementation of anti-corruption policies, collecting and disseminating information, contributing to the moralization of public life, and consolidating the principles of good governance, the culture of public service and the values of responsible citizenship.Footnote7 Based on the constitution, the royal instructions and the law 46–19, the INPPLC contributes to the elaboration of laws and processes to combat corruption but also proposes new interactions between state and society (INPPLC, Citation2021). As per its mandate, the Head of Government and the Parliament are supposed to react to reports submitted by the INPPLC and explain their follow-up. Interviewees pointed out that the INPPLC has several international partnerships and is active in African, Arab and other networks of anti-corruption institutions (interviews 10, 6).

The belated activation of the INPPLC can be seen as a response to the NMD, which is particularly critical with respect to corruption:

(…) the sluggish pace of structural transformation of the economy, which is impeded by high factor costs and an environment that is not conducive to the entry of new players, thus restricting competition and innovation. These obstacles are associated with inefficient regulation … and [help] preserve particular interests, at the expense of the general interest (…). (CSMD, Citation2021, p. 7)

The INPPLC explicitly supports the NMD and proposes to back the creation of the monitoring and compliance mechanisms necessary for its implementation, including improved laws for prosecuting illicit behaviour (Ibriz, Citation2022). The slow pace of implementation of the INPPLC’s law and members was framed as a ‘transitional period’ by Rachdi. He made productive use of the time, producing several reports. One on illicit enrichment is particularly sensitive, exposing the misuse of public funds during the pandemic and illicit enrichment in the energy/petrol sector. Nevertheless, in his 2021 report, Rachdi complained that ‘(…) despite its continuing efforts, the reports, opinions and recommendations of the Instance are still only taken into account to a very weak degree, if at all’ (INPPLC, Citation2021, p. 3, translation by the authors).

Although the nomination of a well-respected president and, after a long wait, of the secretary-general and members, strengthened the INPPLC’s legitimacy, its scope of action remains limited. While it is supposed to act on a wide range of topics including the inner functioning of the state itself, a major legal impediment is built into the Instance’s status. The INPPLC may not examine files, denunciations and complaints relating to cases that have been submitted to the courts or that have already been the subject of a final court judgement or decision. Moreover, it is supposed to halt any investigation as soon as the matter has been submitted to the courts, even in cases involving preliminary investigations under the supervision of the Public Prosecutor’s Office. Given the judicial system’s widely criticized lack of independence, this regulation is a serious hindrance for the INPPLC’s work, leaving a large grey area and potential openings for deliberate action to stop investigations (interviews 6, 10). The INPPLC is not independent from government, but fulfils its intermediary role by actively cooperating with both state institutions and citizens. Strategic partnerships with international organizations (including the UN Office on Drugs and Crime; the OECD, and the World Bank), with institutions in other countries, and with Moroccan ministries, financial authorities and private sector federations, support its autonomy. The INPPLC’s critique of the government’s anti-corruption strategy in 2019 has been acknowledged as a substantial contribution by the OECD (Citation2023), illustrating how it uses its relative independence.

The Human Rights organization CNDH was also created in 2011, replacing the Conseil Consultatif des Droits de l’Homme. Its mandate has been extended from a purely consultative one before 2011 to a more active one after 2018, which includes the right to investigate, to act in cases of torture in prisons, to directly receive and examine complaints of human rights abuses, and to provide legal assistance to complainants. Besides submitting recommendations, proposals and reports on human rights to the Parliament, CNDH can formulate opinions on draft laws and proposals. It oversees the harmonization of laws with international human rights treaties to which Morocco is a signatory, and can organize training sessions for parliamentarians (interview 14). The Council has 12 regional representations across Morocco.

CNDH’s current president is the human rights activist Yasmina Bouayach, who has national and international recognition. The former president, Driss El Yazami, was also a prominent human rights activist and led the organization through a period of important changes after 2011. As with other presidents of intermediary organizations, president Bouayach’s profile includes both civil society activism and official positions nominated by the King, such as her posting as ambassador to Sweden in 2016 and her appointment to the commission on the reform of the Moroccan constitution in 2011.

The CNDH presented a detailed memorandum on the NMD in 2020, insisting that human rights and freedom are fundamental to development and should be the basis of a new social contract (Amine, Citation2020). Indirectly, the organization may influence discourses, as Natter (Citation2021) points out: ‘ … setting up institutions such as the CNDH (…) even if they might be façade institutions initially – can create institutional incentives and dynamics that were not originally planned’. For instance, the CNDH was influential in shaping past reforms of human rights legislation and policies (interviews 3, 14). These included migration policies and the right to asylum, supporting the politically sensitive creation of a human rights association for the Sahraoui people, or proposals for a right to abortion or to abolish child marriage (interviews 6, 10, 14). However, as interviewees noted, the council’s political scope of action is limited and the commitment of its members to question the regime’s ‘red lines’ is low (interviews 6, 10,11). Its suggestions are often not implemented due to a lack of political will, such as in the cases of women’s inheritance rights or child marriage, or when it is criticized for not supporting the rights of political prisoners (Hamoudi, Citation2019). The immunity of its members remains conditioned, and it is often accused for not following up on complaints against state authorities (Kadiri, Citation2017).

While interviewees were mostly supportive of the CNDH’s efforts, they were sceptical about the organization’s potential to push for greater participation on human rights issues (interviews 10, 11, 6). One interviewee considered that the quality of the CNDH’s reports is quite good, and that they have made a difference, for example on the death penalty, children’s rights and gender rights. However, the interviewee pointed out that these are all sensitive discussions and the CNDH is a public institution under a lot of control (interview 12). Reform of family law, for example, is heavily influenced by religious authorities, which move to block new laws. Another interviewee was blunter, pointing out that ‘Bouayach’s nomination was not an independent process. This means she becomes a puppet, in danger of being dismissed. She hasn’t been able to do much. She’s not talking about fundamental problems like freedom of expression or torture’ (interview 6).

The CNDH can take up concerns of human rights violations raised by citizens, for instance through its regional offices. It interacts with citizens when it carries out visits to places of detention and prisons, child protection and rehabilitation centres, hospitals specializing in the treatment of mental and psychological illnesses, and places of detention for irregular migrants. Eleven of its members are NGO representatives, and two are religious authorities, which also facilitates communication with society. The CNDH also includes NGOs in its ‘citizens’ platform to promote a culture of human rights’. The CNDH has nevertheless been heavily criticized for not being critical enough towards state institutions, for instance when exonerating Moroccan authorities of responsibility for the deaths of refugees at the Moroccan-Spanish border in 2022. Interviewees noted that other human rights organizations, such as the NGO Association Marocaine des Droits de l’Homme, have been more critical towards state institutions.

Of the three organizations discussed here, the CNDH is the one with the least political scope of action and independence, and with limited opportunities for interaction with civil society on certain topics. However, its embeddedness in the state apparatus and its interactions with society on some issues of concern potentially give it scope for broader action as an intermediary. Thus far, political control has hindered its independence.

The preceding discussion of the scope of Moroccan intermediary organizations illustrates their positions as conduits between state and society, but also the difficulties they face as changemakers in the NMD context. Three common features of regime policies towards intermediary organizations appear.

The first is the regime’s strategy of delaying implementation after the decision to create an intermediary organization. Various technical but highly political requirements for their work have been delayed for several years: their legal basis, the appointments of their members, and the mobilization of necessary resources. CESE was created in 1996, but became active only after 2011; INPPLC waited from 2018 till 2022 to be able to start working, CNDH’s more proactive role has only been approved in 2018 and is still limited, and the competition authority and institutions for citizen participation face similar challenges (Iraki & Houdret, Citation2021).

The second point is the control of the institution via the nomination of its members. Many members are nominated by the King himself. Nomination processes reflect a careful selection of candidates to ensure equilibrium between scope for change and support for the system. Senior individuals in intermediary organizations have had leading functions in the private sector, but were also members of CESE, ministers and ambassadors. Prominent civil-society leaders, such as the president of the CNDH, have been appointed to provide legitimacy. Such ‘co-optation strategies’ have long been features of the Moroccan political system (Santucci, Citation2006). Nevertheless, co-optation does not mean that appointed individuals and the groups they represent do not want change, even though it does limit their options (El Mnasfi, Citation2021).

Third, the mandates of intermediary organizations, after often long negotiations, are limited either officially, as in the case of the INPPLC, or unofficially, through the lack of follow-up mechanisms. For example, fraud investigated by the court of auditors is often not prosecuted, or the government simply does not respond to the INPPLC’s reports (INPPLC, Citation2021). The weaknesses of the judicial system, including capacity shortages and corruption, reinforce this problem.

These three regime policies towards intermediary organizations illustrate the structural problems of transparency and legitimacy in the Moroccan political system: the authoritarian role of the King and executive institutions in all political processes, which is also closely linked to the economic interests of the political elite (Gana et al., Citation2022); and the citizens’ fundamental lack of confidence in the system (AfroBarometer, Citation2023). Countless critical analyses of development and governance-related issues repeatedly stress the need for reform and improved checks and balances, but implementation is lacking and institutions are relegated to an advisory function. Irrespective of the role of intermediary organizations, the low political commitment for the NMD’s implementation has been captured in a detailed report analysing the consistency of the model and its integration in the government’s strategy (DAMIR, Citation2022).

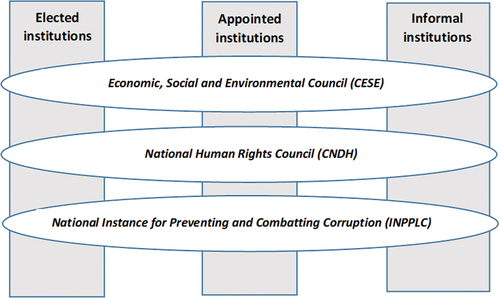

illustrates where intermediary organizations are situated in Morocco’s governance system. Broadly speaking, Morocco has two official ‘pillars’ of governance: elected officials and institutional actors (such as the parliament and local councils); and officials and institutional actors that are appointed by the King (including governors at all levels, heads of public institutions, ambassadors and others (Houdret & Harnisch, Citation2018, p. 944). In addition, a third pillar consisting of a web of institutions, individuals and rules with limited formal governance roles, exercises considerable influence. Morocco’s intermediary organizations link all three pillars, and their membership is drawn from them. Any actor aiming to push the limits of their mandates and facilitate change need to be able to work across the three pillars. This includes Morocco’s international cooperation partners.

International cooperation and support for Morocco’s intermediary organizations

For international cooperation and development policy, intermediary organizations are a growing area of focus (Wehrmann, Citation2016). This is especially the case regarding cooperation with authoritarian countries, where local government, sub-state public sector agencies, and local civil society are often preferred partners to central government (Berry, Citation2010). This raises the question of the agency and ability of intermediary organizations to enter into relations with external actors. Cooperation can provide channels for pursuing discrete interests in specific sectors, such as security, migration or access to resources. This leads us to expect that donors are likely to want to support intermediary organizations as change makers. They are, nevertheless, unlikely to willingly push them into areas that might lead to the loss of control over change processes on the part of the central authorities.

Although the NMD is a national process, the Commission has stressed the need to mobilize support from outside the country, especially with regard to finance (CSMD, Citation2021, p. 157). This became especially apparent with foreign support during the COVID-19 pandemic, and since the adoption of the social security sector reform announced in the NMD. Specifically on international support and partners, relations with the EU are highlighted in five points in the NMD, while relations with the Americas, the Gulf States and the African continent are limited to economic goals. Relations with China, Russia and India are also mentioned, primarily to incentivize investments (CSMD, Citation2021, pp. 160–1).

International interest in working in Morocco is very high (Majidi, Citation2021 and interviews). Morocco’s political stability, middle-income status, and strategic relevance for the security and migration concerns of European countries helps attract funding. Interviews conducted with several development donors in 2022 confirmed their commitment to several NMD objectives, for instance the promotion of good governance. Irrespective of the NMD, donors see potential both for financial cooperation (especially regarding renewable energy) and technical cooperation (especially in social policy areas, such as women’s empowerment, youth, education and social protection) (Sahnouny, Citation2023). Donor agency staff interviewed pointed out that Morocco offers possibilities to safely implement projects at local levels that can impact on people’s lives, to do satisfying work with local authorities, and to engage with communities.

International cooperation partners are nevertheless aware that certain lines are not to be crossed, such as discussing democratic reforms, some human rights issues, or the role of elite figures in key sectors of the economy. Interviewees also expressed frustration at the at the Moroccan government’s haphazard support to programmes in key areas such as healthcare and education. As one interviewee noted, ‘the more formal things get, the less the Moroccans cooperate’, illustrating the need to ‘navigate’ the three governance pillars outlined in .

Development donors are, in principle, interested in supporting all three intermediary organizations discussed in this paper. They are most aware of CESE, which as one interviewee noted, has been able to put pressure on the government. Many of the issues that fall within the mandates of CNDH and INPPLC are also priorities for donors, for example gender rights, the rights of migrants, or relations between civil society and the state. According to interviewees, donors are ready to support initiatives in all of these areas despite the practical and political challenges experienced by CNDH and INPPLC. France, for example, has worked with CNDH on a plea against the death penalty. Donors recognize the crucial role for intermediary organizations in realizing the NMD, if the government were ever to get serious about implementing it. There would, for example, be interest in providing technical and capacity-building support to CNDH and INPPLC, if interest in this were also to be shown on the Moroccan side.

Intermediary organizations’ interest in working with international partners is also contingent. CESE, for example, does not need financial support but is interested in international cooperation with similar organizations in other countries. An interviewee noted that CESE members need intellectual benchmarks and to be able to exchange ideas with peers, and to obtain information from outside to assist their own analyses. For example, CESE has cooperated with the OECD on citizen participation, where, according to interviews, the latter was able to provide guidance on methodology for cross-country comparisons.

The interest and preparedness of cooperation partners to support Morocco’s intermediary organizations is in line with their approach to cooperation with Morocco generally. While ready to support change when the Moroccans initiate it, donors are wary of pushing too hard and are careful to respect the government’s red lines. The country’s corporatist, neo-patrimonial political system sets boundaries for Moroccan and foreign organizations’.

There remains scope for donors to integrate intermediary organizations more explicitly in activities that shape discourses and provide platforms for negotiation, as well as in supporting decentralized structures for these organizations. This requires better understanding of Morocco’s triple governance structure, especially regarding access to high-level informal networks, for which intermediary organizations also provide potential conduits. It also requires clearer strategic thinking on balancing core interests in the security, migration and economic infrastructure sectors with cooperation in support of socio-political change.

Conclusions

This article has illustrated some links between the historical institutionalist, political settlements, state corporatism, and development studies literatures by discussing the role of intermediary organizations as potential drivers of change in social contracts. Given our focus on Morocco, our analysis is also relevant to debates on ‘authoritarian upgrading’, which captures regimes’ propensity to react to popular calls for change by co-opting protest movements or reform leaders and making cosmetic reforms to reduce tensions. The empirical analysis of the three intermediate institutions’ potential role in broader political change confirms other authors’ position regarding the need for combined approaches of agency and structure in the study of regime change (Thelen & Steinmo, Citation1992), and even ‘(…) viewing institutional structures as sites for agency that can potentially stimulate innovation and inspire creativity’ (Mahoney & Snyder, Citation1999, p. 26).

Returning to the first question posed at the outset, we have seen that the three intermediary organizations discussed in this article have limited opportunities to push for the changes envisaged by the NMD. Their existence nevertheless indicates that both the state and societal forces in a corporatist, bureaucratic and yet neo-patrimonial country recognize the need for intermediaries to facilitate the 3Ps. In a relatively stable governance system such as the Moroccan one, changes to the social contract are unlikely to come about through revolution or external intervention. They are likely to be incremental, but not institutionalized via democratic structures created to facilitate change. They require support from within the regime, which takes care to retain control over the process both in terms of substance, and the pace of change. Intermediary organizations operating between state and society can support change processes in periods of liberalization. This may open space for deeper and longer term transformations, even in the Moroccan context.

The NMD is a project for managing and controlling change to the Moroccan social contract. It is loosely defined, contains very few concrete promises, and its implementation needs approval by Morocco’s most powerful decision-makers. The NMD reflects the Moroccan regime’s long-standing strategy of recognizing when change is needed, making space for specific and peripheral reforms that do not affect the central levers of power in the country, and thus ensuring that change does not get out of hand. The fact that political authority tends (or at least attempts) to exercise control at every stage of decision-making and at every level of the public administration means that innovation is rare, conformity is normal and risk-taking is unlikely.

Governance in Morocco works as an uneven balance of power between appointed, elected and informal institutions and channels of influence. The lack of transparency in this structure means that there are few mechanisms in place for identifying or addressing abuses of power. In spite of Morocco’s development deficits, there is little interest in change that impacts on the core levers of power in the country: the royal court, the military and security services, the religious authorities and the judiciary. Intermediary organizations have opportunities to push their mandates but ultimately the political elite decides what will change and how fast this will happen.

With regard to our second question, there is little evidence that Western development donors in Morocco are committed to pushing for change. This is partly because they are interested in Morocco’s stability as a cornerstone of their own security and economic interests. More than a decade since the Arab Uprisings, international cooperation partners actions indicate that they prefer to work with stable autocracies that act as security allies. They are reluctant to offend the Moroccan government and to have to leave the country. Morocco is considered a country in which donors can work and where their programmes and projects can have some impact, especially on social security, gender equality, energy and migration. Within this rather narrow area of possibilities, the most effective focus for donors is to provide resources where there are clear interests and benefits on both sides, and where better outcomes for specific aspects of provision, protection and participation can be achieved. The potential for deeper cooperation between intermediary organizations and international development partners has been recognized even though concrete engagements have proved difficult to realize.

List of Interviews

International development agency representative

International development agency representative

Moroccan Intermediary Organization representative

Moroccan Intermediary Organization representative

Moroccan civil society representative

Moroccan civil society representative

International development agency representative

International researcher

International development agency representative

Moroccan researcher

Moroccan researcher

International development agency representative

International civil society representative

International development agency representative

Moroccan researcher

International development agency representative

International development agency representative

International civil society representative

Moroccan researcher

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The authors thank Azeddine Akesbi and the anonymous reviewers for their very useful comments on this article.

2. We are extremely grateful to our interviewees for their time and their insights on sometimes highly sensitive issues. We have not identified any interviewees or linked the specific insights they provided us to any organization, in order to protect their anonymity.

3. See CESE’s website.

4. CESE’s current president, Ahmed Reda Chami, was a member of the NMD Commission.

5. Rachdi, the former Secretary General of Transparency Maroc, was a member of CESE until his appointment at the IPPLC.

6. See the INPPLC’s website.

7. According to its website https://inpplc.ma/, translation by the authors

References

- AfroBarometer. (2023). Maroc Round 9 résumé des résultats. https://www.afrobarometer.org/publication/maroc-round-9-resume-des-resultats/

- Akesbi, A. (2014). La Constitution et sa mise en oeuvre : gouvernance, responsabilité et (non) redevabilité. In O. Bendourou, R. El Mossadeq, & M. Madani (Eds.), La nouvelle Constitution marocaine à l’épreuve de la pratique (pp. 339–365). La Croisée des Chemins/Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

- Amine, M. (2020). Le Conseil National des Droits de l’Homme plaide pour un nouveau contrat social, Challenge, 10 Août. https://www.challenge.ma/le-conseil-national-des-droits-de-lhomme-plaide-pour-un-nouveau-contrat-social-152549/

- Bächler, G. (2004). Conflict transformation through state reform. In A. Austin, M. Fischer, & N. Ropers (Eds.), Transforming Ethnopolitical Conflict (pp. 273–294). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Bank, A. (2004). Rents, cooptation, and economized discourse: Three dimensions of political rule in Jordan, Morocco and Syria. Journal of Mediterranean Studies, 14(1), 155–179.

- Bergh, S. I. (2017). The politics of development in Morocco: Local governance and participation in North Africa. I.B. Tauris.

- Berrada, M. (2021). Débat : lutte anticorruption, quelle place pour la société civile ? TelQuel, 19(Mars), 19–20.

- Berry, C. (2010). Working effectively with non-state actors to deliver education in fragile states. Development in Practice, 20(4–5), 586–593. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614521003763103

- Bodenstein, T., & Furness, M. (2009). Separating the willing from the able: Is the European Union’s Mediterranean policy incentive compatible? European Union Politics, 10(3), 381–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116509337832

- Capoccia, G. (2016). When do institutions “bite”? Historical institutionalism and the politics of institutional change. Comparative Political Studies, 49(8), 1095–1127. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414015626449

- CES, Conseil Economique et Social. (2011). Pour une nouvelle charte sociale. Des normes à respecter et des objectifs à contractualiser. Rapport du Conseil Economique et Social, auto-saisine. CES.

- CESE. (2018). Le capital immatériel : facteur de création et de répartition équitable de la richesse nationale. Conseil Economique, Social et Environnemental.

- CESE. (2019). Le Nouveau Modèle de Développement du Maroc. Contribution du Conseil Economique, Social et Environnemental.

- Chahir, A. (2020, May 29). Morocco’s coronavirus surveillance system could tip into big brother. Middle East Eye. Retrieved January 15, 2023, from. https://www.middleeasteye.net/opinion/risks-moroccos-coronavirus-surveillance-system

- Chahir, A. (2021). Maroc : le « nouveau modèle de développement », un filet de sauvetage pour la monarchie. Middle East Eye. Retrieved November 15, 2021, from. https://www.middleeasteye.net/fr/opinionfr/maroc-nouveau-modele-developpement-mohammed6-monarchie-revolte-sociale

- Commission Spéciale sur le Modèle de Développement (CSMD, a). (2021). Le Nouveau Modèle de Développement. Libérer les énergies et restaurer la confiance pour accélérer la marche vers le progrès et la prospérité pour tous. Rapport Général.

- Commission Spéciale sur le Modèle de Développement (CSMD, b). (2021). The new development model. Releasing energies and regaining trust to accelerate the march of progress and prosperity for all. Summary.

- DAMIR. (2022). Le programme gouvernemental 2021-2026 à l’aune du Nouveau modèle de développement. Etude comparative et éléments de mise en perspective sur les principaux défis structurels du Maroc. Le Mouvement DAMIR. Janvier.

- Desrues, T. (2020). Authoritarian resilience and democratic representation in Morocco: Royal interference and political parties’ leaderships since the 2016 elections. Mediterranean Politics, 25(2), 254–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2018.1543038

- El Mesbahi, K. (2013). La prévention de la corruption au Maroc, entre discours et réalité. Pouvoirs, n° 145(2), 83–97. https://doi.org/10.3917/pouv.145.0083

- El Mnasfi, M. (2021). Jeunes et dispositifs participatifs au Maroc. Usages du conseil des jeunes de la ville de Ouarzazate ». In Revue Sociétés Plurielles (Vol. n° 4, pp. 3–28). S’expatrier, Presses de l’INALCO.

- Gana, A., Oubenal, M., & Yankaya, D. (2022). Quelles nouvelles imbrications du politique et de l’économique après les « printemps arabes »? Introduction. Mondes en développement, n° 198(2), 7–18. https://doi.org/10.3917/med.198.0011

- Hamoudi, S. (2019). Securitization” of the rif protests and its political ramifications. Moroccan Institute for Policy Analysis (MIPA).

- HCP. (2022). Evolution des inégalités sociales dans un contexte marqué par les effets de la COVID-19 et de la hausse des prix. Haut Commissariat au Plan.

- Heydemann, S. (2019). No exit: Conflict, economic governance, and post-conflict reconstruction in fierce states. In L. Narbone (Ed.), Fractured stability. War economies and reconstruction in the MENA (pp. 14–25). European University Institute.

- Hibou, B. (2006). Maroc, d’un conservatisme à l’autre. In J.-F. Bayart, R. Banégas, R. Bertrand, B. Hibou, & F. Mengin (Ed.), Legs colonial et gouvernance contemporaine (Vol. 2, pp. 123–186). Fasopo.

- Hibou, B., & Tozy, M. (2020). Tisser le temps politique au Maroc: Imaginaire de l’État à l’âge néolibéral. Karthala.

- Hinnebusch, R. (2015). Change and continuity after the Arab uprising: The consequences of state formation in Arab North African States. British Journal of Middle East Studies, 42(1), 12–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/13530194.2015.973182

- Houdret, A., & Harnisch, A. (2018). Decentralisation in Morocco: A solution to the ‘Arab Spring’? The Journal of North African Studies, 24(6), 6, 935–960. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629387.2018.1457958

- Ibriz, L. (2022). Lutte anti-corruption, enrichissement illicite, protection des lanceurs d’alerte… le point avec Bachir Rachdi, Le360, 12/11/2022. Retrieved November 15, 2022, from. https://fr.le360.ma/politique/lutte-anti-corruption-enrichissement-illicite-protection-des-lanceurs-dalerte-le-point-avec-bachir-270223/

- INPPLC. (2021). Rapport Annuel 2021. Résumé Exécutif. Instance Nationale de Probité, Prévention et Lutte contre la Corruption.

- Iraki, A., & Houdret, A. (2021). La Participation Citoyenne au Maroc : Entre expériences passées et régionalisation avancée. Rabat/Bonn, INAU/DIE.

- Kadiri, M. (2017). The evolution of Morocco’s human rights movement. Arab Reform Initiative.

- Khan, M. (2017). Political settlements and the analysis of institutions. African Affairs, 117(469), 636–655. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adx044

- Kjaer, P. (2015). From corporatism to governance: Dimensions of a theory of intermediary institutions. In E. Hartmann & P. F. Kjaer (Eds.), The evolution of intermediary institutions in Europe: From corporatism to governance (pp. 11–28). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lederach, J. (2002). Building mediative capacity in deep-rooted conflict. The Fletcher Forum of World Affairs, 26(1), 91–100.

- Li, W. (2022). Party‐led innovation of state‐sponsored intermediary organizations in Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangdong of China: Effects and managerial strategies. Asian Politics & Policy, 14(2), 199–215. https://doi.org/10.1111/aspp.12634

- Lieberman, R. C. (2002). Ideas, institutions, and political order: Explaining political change. The American Political Science Review, 96(4), 697–712. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055402000394

- Loewe, M., Zintl, T., & Houdret, A. (2021). The social contract as a tool of analysis: Introduction to the special issue on “framing the evolution of new social contracts in Middle Eastern and North African countries”. World Development, 145, 104982. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.104982

- Maghraoui, A. (2001). Political authority in crisis: Mohammed VI’s Morocco. Middle East Report, (218), 12–17. https://doi.org/10.2307/1559304

- Maghraoui, D. (2009). Introduction: Interpreting reform in Morocco. Mediterranean Politics, 14(2), 143–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629390902983674

- Mahmoud, Y., & Ó Súilleabháin, A. (2020). Improvising peace: Towards new social contracts in Tunisia. Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding, 14(1), 101–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/17502977.2019.1629377

- Mahoney, J., & Snyder, R. (1999). Rethinking agency and structure in the study of regime change. Studies in Comparative International Development, 34(2), 3–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02687620

- Mahoney, J., & Thelen, K. (Eds.). (2009). Explaining institutional change: Ambiguity, agency, and power. Cambridge University Press.

- Majidi, Y. (2021). Comment Benmoussa veut vendre le nouveau modèle de développement aux diplomates étrangers. Tel Quel. Accessed June 16, 2021. https://telquel.ma/2021/06/16/comment-benmoussa-veut-vendre-le-modele-de-developpement-aux-diplomates-etrangers_1725871

- McCandless, E. (2018). Reconceptualizing the social contract in contexts of conflict, fragility and fraught transition. Working paper. Witwatersrand University.

- Mkandawire, T. (2015). Neopatrimonialism and the political economy of economic performance in Africa: Critical reflections. World Politics, 67(3), 563–612. https://doi.org/10.1017/S004388711500009X

- Mohsen-Finan, K. (2013). Changement de cap et transition politique au Maroc et en Tunisie. Pouvoirs, n° 145(2), 105–121. https://doi.org/10.3917/pouv.145.0105

- Natter, K. (2021). Crafting a ‘liberal monarchy’: Regime consolidation and immigration policy reform in Morocco. The Journal of North African Studies, 26(5), 850–874. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629387.2020.1800206

- OECD. (2023). Examens de l’OCDE sur la gouvernance publique : Maroc: Pour une administration résiliente au service des citoyens, Examens de l’OCDE sur la gouvernance publique. OECD Publishing.

- Paulo, S., & Klingebiel, S. (2016). New approaches to development cooperation in middle-income countries: Brokering collective action for global sustainable development. DIE discussion paper 8/2016.

- Rojas, F., & King, B. G. (2018). How social movements interact with organizations and fields: Protest, institutions, and beyond. The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Social Movements, 2, 203–219. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119168577.ch11

- Saaf, A. (2015). Changement et continuité dans le système politique marocain. In : Le Maroc au présent : D’une époque à l’autre, une société en mutation. Centre Jacques-Berque.

- Sahnouny, M. (2023). Morocco, EU to sign five cooperation programs worth €500 million. Morocco World News. 1 March 2023 Retrieved January 11, 2024, from https://www.moroccoworldnews.com/2023/03/354265/morocco-eu-to-sign-five-cooperation-programs-worth-euro-500-million

- Santucci, J.-C. (2006). Le multipartisme marocain entre les contraintes d’un « pluralisme contrôlé » et les dilemmes d’un « pluripartisme autoritaire ». Revue des Mondes Musulmans et de la Méditerranée, (111–112), 63–118. https://doi.org/10.4000/remmm.2864

- Schlumberger, O. (2008). Structural reform, economic order, and development: Patrimonial capitalism. Review of International Political Economy, 15(4), 622–649. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290802260670

- Snyder, R., & Mahoney, J. (1999). The missing variable: Institutions and the study of regime change. Comparative Politics, 32(1), 103–122. https://doi.org/10.2307/422435

- Thelen, K., & Steinmo, S. (1992). Historical institutionalism in comparative politics. In S. Steinmo, K. Thelen, & F. Longstreth (Eds.), Structuring politics: Historical institutionalism in comparative analysis (pp. 369–404). Cambridge University Press.

- Tozy, M. (1991). Les enjeux de pouvoir dans les ‘champs politiques désamorcés’ au Maroc. In M. Camau (Ed.), Changements politiques au Maghreb (p. 157). Editions du CNRS.

- Vairel, F. (2022). How self-limiting mobilization works in Morocco. Mediterranean Politics, 27(3), 344–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2020.1781476

- Volpi, F. (2017). Revolution and authoritarianism in North Africa. Oxford University Press.

- Wehrmann, D. (2016). The polar regions as “barometers” in the anthropocene: Towards a new significance of non-state actors in international cooperation? The Polar Journal, 6(2), 379–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/2154896X.2016.1241483

- Young, O. R. (1986). International regimes: Toward a new theory of institutions. World Politics, 39(1), 104–122. https://doi.org/10.2307/2010300

- Zine, G. (2021). Youssef Belal: le rapport de CSMD fait l’impasse sur la jonction entre Etat et société (Interview). Retrieved June 30, 2021, from. https://www.yabiladi.com/articles/details/110910/youssef-belal-rapport-csmd-fait.html