ABSTRACT

Digitalization has far-reaching yet under-researched impacts on state–society relations. This article addresses this gap and explores digitalization as a driver of change to social contracts. The conceptual framework explains how it changes (a) the state’s duty to grant protection, provision, and participation in exchange for legitimacy; (b) the modes of state–society interaction; and (c) the contracting parties with respect to their location and their relative power position. Based on a literature review and recent developments in digitalization, the article then discusses how this plays out in the MENA region. It shows that digital surveillance by authoritarian regimes often dominates over the states’ duty to protect their citizens. Spaces for political participation increase through social media and online platforms but often fail to translate into ‘offline’ mobilization. Digitalization can improve public service provision, but only for digitally-connected citizens. Thus, digitalization tends to enhance the relative power positions of MENA states even if states themselves partly depend on external actors for access to and control over digital technologies. Overall, digitalization is an important, structural driver of change to social contracts but pre-existing state–society relations and governance framework conditions lead to either more inclusive or rather more authoritarian social contracts.

Introduction

DigitalizationFootnote1 is a global megatrend that not only brings fundamental technical change but also has far-reaching societal implications. New forms of social organization via social media or digitalized administration are obvious – even more so since the COVID-19 pandemic – but the overall impact on state–society relations is much less visible. Also, the particular impacts on different world regions are seldom addressed. This paper aims to help fill this gap by focusing on two key research questions: which impacts does digitalization have on state–society relations as conceptualized in a model of the ‘social contract’? Which opportunities and risks does this entail for more inclusive social contracts? Beyond the theoretically motivated literature review, the second part of this article illustrates these dynamics with practical examples. In line with the general orientation of this special issue, these examples focus on the MENA region, where social contracts are currently being reshaped and renegotiated, inter alia by the effects of digitalization.

In the MENA region, the 2011 uprisings articulated a fundamental dissatisfaction with the established state–society relations. Recent crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic, food shortages due to Russia’s war on Ukraine; the Beirut port blast in 2020 the 2023 earthquake in Syria and Turkey and the reignited Israeli-Palestinian conflict have added to existing grievances. Social contracts in the region (i.e., the expectations and mutual obligations of governments and populations, but also between different social groups) are being negotiated in the different countries to a varying degree, redefining the rights and duties in state–society relations (Loewe et al., Citation2021). Simultaneously, the region has seen an important boost in digital connectivity and digital services in the past years, reaching 96 per cent mobile internet coverage and 51 per cent mobile internet usage in 2022; smartphone adoption is with 82 per cent (North Africa) and 85 per cent (Levant) of the population very high (GSMA, Citation2023). However, access to digital technologies varies considerably between countries and users, depending on the region, income, age, and gender. In 2019, MENA women were 21 per cent and rural population 37 per cent less likely to use mobile internet than their male respectively urban counterparts (GSMA, Citation2020). Likely, these two trends – the renegotiation of the social contract and the increasing usage of digital tools – reinforce each other. Yet, a more systematic approach with concrete examples to understand how digitalization underpins and drives changes in social contracts in the MENA region is missing from academic literature.

Based on a model of the social contract, we analyse ICT-related changes in the deliverables exchanged between state and society. In the following section, we explain how we use the concept of social contracts to understand state–society relations, and then discuss how ICT influences (i) the different deliverables, (ii) state–society interaction and (iii) the composition of the involved actors. Thereafter, we demonstrate that, in the MENA region, digital protection, participation and provisions unfold highly different dynamics for the renegotiation of social contracts. We thus illustrate digitally induced changes in the MENA region by focusing on the transformation of the contract’s deliverables, but we also show that, in each of these fields, digitalization affects the balance of power between actors and their ‘modes of interaction’. In the conclusion, we summarize the main findings, critically review the use of the social contract concept to analyse changes in state–society relations under the influence of digitalization, and point to further research needs.

Methodologically, we draw on literature from political science, technology and innovation, and media and communication studies. Empirically, we draw on examples from a variety of sectors focusing, in particular, on e-governance and social media activism, as grievances over insufficient governance have been a major trigger of protests in the MENA region, and digital activism provided important means to express these grievances. These examples are meant to illustrate the different ramifications and far-reaching impact digitalization has on heterogeneous social contracts in the region and thus abstains from selecting detailed case studies.

The existing literature on digitalization rarely explicitly addresses state–society relations nor provides a conceptual framework to study their complex causal interactions. Analyses on digitalization and governance issues often focus on ‘technocratic’ aspects relevant to management and administration, in some cases also linking the analysis of e-governance services to their effects on political attitudes (Bante et al., Citation2021). Other relevant streams of literature focus on the effects of digitalization on democratic governance, finding only a moderate positive correlation between e-governance and democratic governance (Suhardi et al., Citation2015), and point to the fundamental role of existing trust in state institutions for the trust in and use of e-governance tools (Teo et al., Citation2008). Confirming these concerns, Gasmi et al. (Citation2023) identify a correlation between digitalization and greater citizen participation in the MENA region, yet time-lagged by three years and moderating negative effects only up to a certain threshold level. However, state–society relations in the digital age are also marked by increased surveillance and control (Kharroub, Citation2022; Schlumberger et al., Citation2023).

This article systematically analyses digitalization’s manifold influences on state–society relations using the lens of the social contract concept by Loewe et al. (Citation2021) and incorporates findings on different policy fields, generally and in the MENA region. In contrast to Gasmi et al.’s (Citation2023) quantitative study based on the same concept, our goal is to capture causal mechanisms and generate further insights on shifting power relations and the opportunities and challenges for renegotiating political change.

Conceptual framework: Social contracts and digitalization

We conceptualize social contracts as ‘the entirety of explicit or implicit agreements between all relevant societal groups and the sovereign […], defining their rights and obligations toward each other’ (Loewe et al., Citation2021). In essence, state and society exchange a set of deliverables: the state ensures protection from physical threats, provision of public services in different fields and political participation to citizens. In exchange for these ‘3Ps’ (ibid.), citizens recognize the regime’s legitimacy and, as more visible signs of their allegiance, pay taxes, participate in voting or complete their military service. This recognition does not need to be made explicit by all members of society (as was assumed by the early state philosophers Hobbes, Locke and Rousseau) but social contracts are still valid if parts of society only tolerate them without expressing their consent (Loewe et al., Citationin press). Social contracts are mostly national but there may be ‘sub-contracts’ between the state and specific interest groups based on their ethnicity, geographical origin or other shared identity (Houdret et al., Citation2017). The main function of social contracts is to make state–society relations more stable and their outcomes predictable. If one side is discontent with the deal, or if structural or framework conditions change, for example through digitalization, social contracts need to adapt (Loewe et al., Citationin press). Social contracts can be implicitly reshaped though new rules and practices or explicitly renegotiated.Footnote2

Digitalization as a driver of change in social contracts concerns their deliverables in several ways, that is, their contents, modes of interaction and contracting parties. Accordingly, the following subsections conceptualize how digitalization shapes state–society relations through modifications in the deliverables’ contents (‘new rights and duties’), and how these modifications are further impacted by altered forms of interaction (‘new fora’) as well as by a reconfigured set of stakeholders and the area of the contract’s application (‘new actors’).

New rights and duties: Change in the deliverables

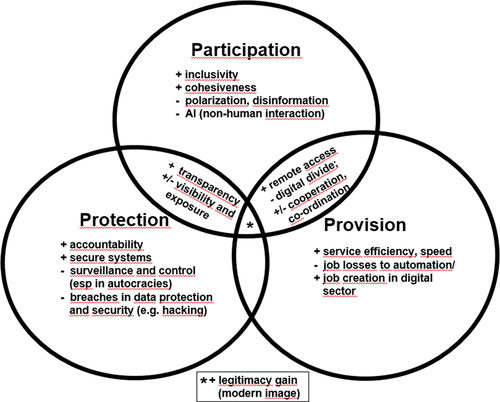

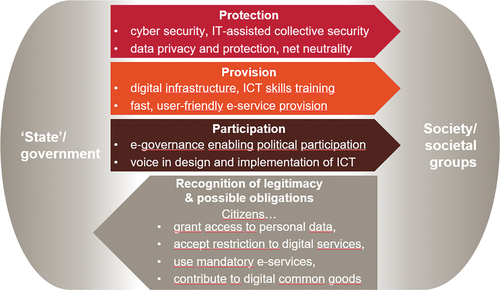

Internet access, e-health, e-education – an increasing share of the deliverables that governments provide to their citizens is digital or has digital components. Digitalization both alters the form of established public services (e.g., electronic forms replacing paper forms) and creates new goods and services to be exchanged. Digitalization thus results in ‘product innovation’ and new possibilities, and new or transformed rights and duties within existing social contracts. These new rights and duties span all above-mentioned 3Ps delivered by the state as well as citizens’ obligations and their expectations towards governments (see ). Subsequently, states need to

Figure 1. Digital deliverables in social contracts.

Protect society’s digital rights, defined as ‘human rights in online spaces’ (Roberts, Citation2021, p. 11) to take care of cyber security, data privacy, net neutrality as well as regulations concerning digital goods and services. This protection ideally spans from protecting against misuse by individuals or corporations, but also by state authorities themselves.

Provide digital infrastructure, such as internet coverage and public hard- or software equipment for poorer population groups, schools, etc., and training for ICT skills;

Let societal groups participate and give citizens a voice in how digital technologies and related infrastructure are designed and deployed, related laws developed, and new tools (such as crowd-funding or digital citizen science) used.

In turn, citizens need to recognize (or at least tolerate) the sovereign’s regulatory power also in the digital realm. This may include (i) granting state authorities the right to collect and store digital data, including for public administration and e-service provision; (ii) accepting restricted access to internet or digital services; (iii) using mandatory e-services (e.g., online filing of tax returns); and (iv) contributing to digital common goods in the context of humanitarian aid, early warning or economic development.

Savings in costs and efficiency are the main reasons why states switch to digital modes of governance. Goods and services can be exchanged much quicker, cheaper and to more recipients, even where transportation is scarce or where recipients are less mobile. The potential provisionary and participatory gains to be reaped from the digital transformation are thus significant but hard to measure. Available indices on states’ digital deliverablesFootnote3 address some of these interactions, but do not sufficiently capture related changes in state–society relations. Thereby, provisionary and participatory gains do not need to be reciprocal but there may be a trade-off, if certain actors have more access to state deliverables than others. Especially in authoritarian settings, such as in MENA, provision and participation tend to develop in a divergent way, as state–society relations are built on the co-optation of well-connected cronies and the repression of less politically connected actors (e.g., Schlumberger et al., Citation2023). Most of the new digital opportunities are evolving quickly, but related rights and duties relevant to social contracts often remain rather implicit than formalized in related laws or complaint mechanisms.

New fora: Change in the forms of interaction

Digital transformation’s impact on the deliverables is also reflected in the ways and channels through which state and society interact. This ‘process innovation’ creates new fora for exchange and decision-making. While we cannot fully analyse all aspects of these new modes of interaction, we consider their effects on the three key deliverables and on the balance of power between state and society:

First, digitalization challenges and transforms the state’s key function of protecting its citizens from internal and external threats. Digitalization can reinforce state capacities to protect citizens from criminal acts (e.g., by using closed-circuit television CCTV), abuse of power (e.g., through block-chain technology or more transparent processes and information) or external military threats (e.g., digital warfare, drones).

However, digitalization can also facilitate the abuse of state power and reinforce the protection of elite interests at the expense of the rights and security of the majority of the population, particularly if regulation and data protection are weak. Especially in authoritarian contexts, virtual spaces are controlled, securitized and prone to official propaganda just as ‘real spaces’ are controlled by digital surveillance. Roberts (Citation2021) comparative study of ten African countries identifies an autocratic toolbox of digital repression, including disinformation campaigns, shutdowns, surveillance and arrests.

In spite of an extensive use of ICT and social media, citizens often lack awareness about their digital rights. Despite a diffuse expectation that data privacy is important, users often do not follow up on data protection requirements (the so-called ‘privacy paradox’, Kokolakis, Citation2017) and thus do not claim digital protection towards the state. In this sense, social contract’s deliverables may change even if citizens do not demand these changes or actively consent to them.

Second, digitalization transforms the state’s key function of provision: it can improve public service provision, ranging from administrative processes (e-claims, billing, service monitoring, regulating cross-border e-commerce (de Melo & Solleder, Citation2022), etc.) to education and health (remote consultations, online information and data sharing and storage) and to basic infrastructure services (water, electricity, transport). Digital forms of state–society interaction can support more efficient, reliable and transparent services. Nevertheless, digital provision can restrict state capacities in providing economic security, since it remains unclear whether more employment opportunities are lost to automation than are newly created in the digital sector.

Third, digital state–society interaction changes participation – a phenomenon closely linked to the new opportunities created by (state-, private sector-, or citizen-led) digital provision. E-participation can be either state-led (e.g., through information and consultation platforms), or citizen-led. Citizen-led digital tools can increase information and data sharing and thus monitoring transparency and accountability. Technical innovations driving this change include instant messaging, voice calls, video chat and peer-to-peer file sharing, consumer-generated media or online platforms for classifying, rating and reviewing.

Technological progress, like big data computing and block-chain technology, improves the access to information on goods and services for a multiplicity of actors and thereby builds up pressure for more transparency. This generates new spaces for participation, but states, societies and companies need specific knowledge. They thus rely on international knowledge transfer, an exchange about benchmarks and best practices for instance in rating systems, but also international coordination about legal aspects.

Yet, if not regulated well, digital forms of interaction can also restrict participation to specific ‘digital bubbles’. These are spaces of often highly polarized debates within closed-online communities prone to disinformation or fake news, as they rely on social media and their pre-programmed algorithms and ‘likes’. Communities’ cohesion can suffer because digitalization reduces human face-to-face interaction. Algorithms, bots, Internet of Things and Artificial Intelligence all replace human interaction and make it more difficult to distinguish between trustworthy and ‘fake’ information which may lead to political disillusionment (Maati et al., Citation2023) and strengthen the tendency towards fragmented digital spaces or a ‘digital tribal society’ (Türcke, Citation2019).

As digitalization changes the forms of interaction in protection, provision and participation, the resulting new fora can be shaped and used in different ways by the state, societies and the private sector, with repercussions on the balance of power between state and society. States partly shape these interactions through laws and regulations, but automatized processes such as data collection and artificial intelligence increasingly influence governments’ policies and limit their scope as well as transparency and accountability of decision-making (Pasquale, Citation2015; Roberts, Citation2021). Societal groups have less codified means of shaping the interaction in their interest.

Thus, whether these changes in the forms of interaction improve or restrict protection, provision and participation largely depends on governments’ willingness to grant citizens a voice on how to shape these changes, and on their willingness and ability to control related private sector activities.

New actors: Stakeholders and areas of application

Digitalization’s impact on the deliverables of social contracts further changes the involved actors or the spatial extension of social contracts, which in turn can trigger a re-negotiation of states’ and societies’ rights and obligations. Thus, technological innovations are not ‘neutral’ as economists initially suggested but produce winners and losers (e.g., Brynjolfsson, Citation2022, p. 275).

First, digitalization can change the reach of social contracts within and beyond states’ boundaries. Spatial differences within countries (such as the rural-urban divide) depend on technical infrastructure like grid, connection and endpoint equipment. Moreover, digital forms of interaction, especially through social media, can make societies more active even across regional and national divides – or restrict this exchange to the above-mentioned ‘digital bubbles’. An increasingly transnational civil society uses digital platforms to build networks and share information, mobilize protests, and provide an alternative for government-controlled media (e.g., Karolak, Citation2020).

Thus, while a social contract’s point of reference remains first and foremost the nation state, actors’ digital international interlinkages influence its (re-)negotiation. Citizens can become aware of how their social contract compares to the situation elsewhere (Loewe et al., Citationin press). Diaspora communities, opposition groups, cyber criminals or internationally active private companies can gain influence on discourses or social mobilization. On the governments’ side, such interlinkages range from international development assistance in the liberal state system to authoritarian learning (Leenders, Citation2016) of intelligence and military services (e.g., Russia, China). External actors can affect power relations within states, depending on pre-existing ties to domestic players and on actors’ affinity to digital tools.

Second, digitalization can also change the parties’ relative power position in the contract, depending on the actors’ organizing ability and their digital skills. Marginalized groups are most affected by the digital divide: the rural-urban and gender gaps in mobile internet use remain substantial (GSMA, Citation2020). Positive effects of digitalization on inclusion thus depend on complementary, but not exclusively digital services which can then support and empower formerly marginalized groups such as women (Sreberny, Citation2015), youth (Monshipouri, Citation2021), or communities living in remote areas. Other groups may choose not to use digital technologies (because of concerns about data safety or reservations against technological progress) and are then marginalized.

Digitalization also influences the power positions of governments and of/among state agencies, which creates governance challenges at different levels: within the state, with respect to the private sector, and in the state’s interaction with society. First, within the state apparatus, different state entities may digitalize at a different pace, or specific authorities get new, powerful mandates related to digitalization. This affects the coordination between ministries and subordinated entities, for instance when formerly powerful ministries are supposed to share internal data with new authorities for digitalization. Too many parallel initiatives may lead to non-functional services, inconsistent and potentially overlapping activities (Paul et al., Citation2020), as well as ill-targeted investments or lacking data protection. And even if coordinated well, there is the danger that those actors who are most influential are not necessarily the ones with the most efficient or inclusive solutions.

A second governance challenge appears where state authorities may lose digital sovereignty because of their dependency on transnational technical providers. Digital equipment (e.g., hardware components) and service infrastructure (e.g., servers, undersea cables) are often beyond the reach of national authorities once they have been built and global value chains have been established. The world wide web and international leading tech providers are outside the jurisdiction of national governments (Mayer & Lu, Citation2022). Thus, state deliverables rely on technologies developed, owned and provided by third parties unconnected to the social contract.

The third governance challenge is that digitalization may alter the government’s position in the social contract and its interaction with society. While citizens need to recognize the sovereign’s digital regulatory power, governments can actively manage, but, given external influences, not fully implement their preferred regulatory framework (Lawrie, Citation2021). Transnational (civil) societies can partly escape digital control e.g., by relying on proxy servers. Democratic governments and international organizations also struggle over common regulatory standards, as the European Union’s Digital Services Act (DSA) and Digital Markets Act (DMA) show (Satariano, Citation2022).

In the digital age, the state’s relative power in the social contract therefore depends on its ability to coordinate and cooperate at all three levels: within and between state administrations, with the national and international private sector, and with its own citizens.

As discussed throughout the section, digital transformation entails several pitfalls and potentials for the renegotiation of social contracts, both for specific state deliverables or where they overlap (). Effects on state legitimacy are ambiguous: e-services and ‘digital by default’ are the epitome of a modern image and can boost governments’ legitimacy. Yet, they can also support a new variety of authoritarian upgrading (Heydemann, Citation2007), when emphasizing modern means while not changing exclusionary political processes (see also Schlumberger et al., Citation2023). Moreover, lacking citizen trust in governments often impedes their use of public digital services (Wood, Citation2022) so that chances to boost state legitimacy through digital means remain small. Maerz (Citation2016) shows that according to the type of authoritarian regime, e-government ‘simulating’ participation and transparency may strengthen either external or internal legitimacy. All this confirms that the above-mentioned opportunities of digitalization for increased and more representative participation depend on much more than solely technical infrastructure, namely digital literacy and a willingness to grasp digital opportunities, but also trust and governance.

Authors’ own design.

The next section showcases examples from the MENA region to illustrate potential opportunities and challenges of digitalization for changing social contracts that have been outlined in this conceptual framework.

Digitalization as a driver of change in MENA social contracts

E-governance and the governance of digitalization induce massive processes of change in the MENA region with potentially far-reaching impacts on societal relations. This section sheds light on how digitalization affects the three types of deliverables in the region’s social contracts. For each deliverable, we look at both product and process innovation, as well as changes of scope, actors, and balances of power to understand their (potential) effects on social contracts. As MENA countries are not homogeneous in their digital development and related policies, we highlight particularly informative examples of digitalization as a driver of change to social contracts with respect to digital surveillance (protection), social media activism during the so-called Arab Spring (participation) and e-governance experiences (provision). Rather than a comprehensive analysis of causal links between digitalization and change in social contracts, this section is meant to set the scene for more in-depth studies by outlining major trends and highlighting specific examples on how change can occur, and often already materializes.

Digital protection: Digitalization as driver of surveillance

As explained above, the field of protection illustrates the full scale of ambiguity with both potential negative and positive effects of digitalization on state–society relations. The following examples illustrate that overall in the MENA region, digital protection is weak where it should support the safety of individuals (and companies) against state or foreign control, but it is strong where autocratic regime maintenance can benefit from it. However, the strong influence of international players may also restrict or boost state power.

Regulative capacities on online activities are weak throughout the region. For instance, there are very few regulatory authorities overseeing secure digital payments or other services important to businesses as compared to other middle-income countries (Wood, Citation2022). This also negatively impacts investment and growth, as there are no digital markets acts, a fact that weakens innovation, growth and competitiveness (El-Darwishe & McPherson, Citation2022). Likewise, digital protection of individuals is also insufficient as ‘data protection laws are either very weak or [in over half of the countries of the region] non-existent’ in spite of the widespread use of data-heavy systems (Fatafta & Samaro, Citation2021). In global comparison, the ‘privacy paradox’ (Kokolakis, Citation2017; see above) seems to be considerable, as the average MENA citizen seems not to be overly concerned about the possible monitoring of online communication (e.g., ictQatar, Citation2014).

Even worse, MENA states not only fail to protect citizens from cyber-crime due to weak legislations and enforcement, but they additionally increase the threat by misusing digital tools and creating insecurity through digital surveillance. In a wicked way, digital surveillance can be framed as protecting general public order to the benefit of the general public against organized crime, even if it does not sufficiently take citizens’ rights into account but, in contrast, actually harms the citizen rights it claims to protect.Footnote4 Since 2011, Arab governments heavily invested in ‘surveillance, censorship, and manipulation of technologies with the primary aim of preventing challenges to their own survival’ (Kharroub, Citation2022). Especially since the COVID-19 pandemic, the deployment of digital surveillance tools has further increased, inter alia through spyware on health applications (Allouche, Citation2020). In Egypt, digital surveillance enables the state to shape public expectations of the social contract and related state performance (Rutherford, Citationin press: this special issue). Obligatory SIM card registration or imported AI-based surveillance (for Egypt: Roberts, Citation2021, p. 12) facilitate surveillance, as well as online participation tied to unique IP addresses and often to personalized accounts. Moreover, MENA internet sites are often censored in relation to domestic political, geo-political or religious issues (e.g., Noman, Citation2019).

While digitalization can potentially foster transparency and accountability, and thus protection, through data collection and exchange, most such attempts remained patchy and ineffective. The Open Government Partnership for instance is a tool to achieve this (Open Government Partnership, no year). Yet, implementation challenges in MENA partner countries (Jordan, Morocco and Tunisia) confirm that underlying governance problems need to be tackled first for its effective functioning. Digital governance reproduces existing governance failures including potential threats to the rights and security of the majority of the population, and especially political activists.

At the international level, collaboration with technology providers and manipulation by outsiders has affected the power of MENA governments and their delivery of ‘protection’. Lacking cyber-regulations puts citizens, companies and paradoxically also governmental data and political representatives themselves at risk. When MENA governments bought Pegasus spyware from Israel, not only journalists and activists were spied on both in their home countries and abroad, but also high-ranking government members and the Moroccan king (Lynch, Citation2022). This reveals how vulnerable governments and intergovernmental relations are to digitalization. In international comparison, MENA states are weak in their defence against cyber-attacks, for instance, there are very few secure internet servers in North African countries (Brach, Citation2020, p. 15). On the other hand, digital technology collaboration of Arab States with China, Russia and Israel has provided what Kharroub (Citation2022) calls ‘the tool kit for Arab digital authoritarianism’. MENA governments not only enlisted troll factories and twitter armies from Russia but also surveillance technologies from the United States, United Kingdom, Germany, and France (ibid.). Even ‘more innocuous Western firms such as Google and Twitter are also complicit in cooperating with autocratic governments, providing user data to them and censoring content upon request’ (Josua & Edel, Citation2021, p. 600; similarly; Kharroub, Citation2022). MENA governments primarily use these tools to control their populations, but in some cases also to support their geopolitical interests abroad through information manipulation (e.g., by Saudi Arabia and the UAE in Sudan, Libya, Qatar and the US; Bradshaw & Howard, Citation2019; Kharroub, Citation2022). Obviously, this foreign influence can have wide-reaching impact on national social contracts, their deliverables and their legitimation. Although civil societies have, under such conditions, little space for the negotiation of protection in the social contract, they actively engage in protecting their cybersecurity, as international alliances such as the New Middle East and North Africa Coalition to Combat Digital Surveillance demonstrate (Access Now, Citation2021).

Overall, these examples show that digitalization rather protects regime and elite interests than enabling citizens to renegotiate the social contract. Digitalization reinforces the need for more state protection of the citizens, of the private sector, but also of states seeking self-protection from dependency on foreign infrastructure and digital services and other countries’ geopolitical agendas. Inversely, geopolitical disagreements may also ‘create obstacles for meaningful cybersecurity cooperation’ (Douzet et al., Citation2022).

In sum These examples illustrate that digitalization enlarges the geographical scope of the social contract, sometimes even in unforeseen ways, for instance when foreign hard- and software dominate digital exchange within countries or reinforce geopolitical alliances. Without sufficient regulation, digital protection rather serves regime interests at the expense of citizens’ and private sector protection.

Digital participation: Driving online, not offline mobilization?

Digitalization has multiple implications for participation in social contracts – new thematic fields and new transnational actors appear, and the modes of interaction themselves change. In regional comparison, social media penetration in MENA is quite high (GSMA, Citation2020). During the Arab Uprisings of 2010–11, activists drew on digital means to reclaim their position in social contracts which did not give them any space to express their needs and get involved in policy making and implementation. The use of digital tools expanded the geographical and socio-political scope of the social contract and gave voice to different parties involved in its renegotiation. It influenced power relations between parties as it changed access to information and mobilization, and it impacted the interplay between online and offline mobilization illustrating the moving spheres of renegotiation.

Several scholars focused on the facilitating role of social media in the Arab Uprisings (e.g., Karolak, Citation2020). Social media not only enabled information-sharing and protest mobilization with sizable multiplier effects, emotionally appealing audio-visuals, and low transaction costs (e.g., Breuer et al., Citation2015). The geographical dispersion of activists across territory, even transnationally, was a strength, as it created visibility abroad. TV channels like al-Jazeera brought social media footage to Tunisians beyond the digitally connected elite (ibid.) and, in the early days of the protests, local communities without meaningful internet access took part in the protests (Charrad & Reith, Citation2019).

However, oppositional social media activists became more exposed and the protests were relatively swiftly met by state repression, including digital surveillance. Regimes reacted by banning websites and blocking access, such as during Egypt’s 5-day internet shutdown in January 2011, or by digital counter-propaganda (Al-Rawi & Iskandar, Citation2022; on the Syrian Electronic Army see; Al-Rawi, Citation2014).

While state authorities were taken by surprise in 2011, they afterwards built up their digital infrastructure to fend off social media activism and mobilization. Thus, in the longer run, the Arab Uprisings may burden, not accelerate digitally enhanced activism. Regimes invested in skills and technology as, ‘at times of potential protest diffusion, like during the Arab uprisings and their aftermath, such [authoritarian] learning may be assumed to help regimes build “autocratic firewalls”’ (Leenders, Citation2016, p. 17). Over time, Arab autocratic regimes’ counteraction to digital activism became not only standard repertoire (for ‘nightly internet curfews’ in 2019–20 Iraq, see Josua & Edel, Citation2021, p. 599) but also technically more sophisticated (e.g., pro-Saudi automated Twitter bots after the Khashoggi murder in 2018, see Kharroub, Citation2022).

Irrespective of autocratic repression, the geographical dispersion of online mobilization and fragmented organizational power often negatively affect meaningful collective action across online- and offline communities. Digitalization empowers particularly ‘youth with existing offline economic power and/or cultural capital’ (Banaji & Moreno-Almeida, Citation2021), but is only significant – and representative of larger societal trends – in combination with offline mobilization (Aouragh, Citation2016; Banaji & Moreno-Almeida, Citation2021; Charrad & Reith, Citation2019; Monshipouri, Citation2021). Any reflection on how digitalization affects the groups negotiating social contracts therefore needs to take the ‘offline-reality’ into account. Studying protests in Lebanon, Aouragh (Citation2016, p. 127) for instance laments that ‘[r]ecent analysis of online activism has tended to focus on visibility and digital connectivity at the expense of content, organization and political ideology’. Digital mobilization may therefore not only enable the renegotiation of social contracts but also adversely affect it if communities become fragmented and institutions lack shared norms and formal rules. This in turn can perpetuate instability instead of an ‘ordered renewal’.

Furthermore, though social media is quick and highly useful for advocacy and mobilization, it is prone to fake news and fragmentation. Wagner et al. (Citation2023) argue that online interaction within closed echo chambers is particularly strong in the region. Interview data from Jordan, Morocco, Tunisia and the UAE show that mistrust in digital communication and state authorities’ repressive action led to disillusionment with digital media (Moreno-Almeida & Banaji, Citation2019).

And still, in spite of mistrust and highly restricted space for political activism, different forms of digital participation thrive in the MENA. Ayish (Citation2018) observes that MENA youth show a ‘hybrid identity’ that helps to create a new civic public sphere bridging online and offline spaces. Moreno-Almeida (Citation2021) points to satirical pictures and videos as a creative indirect way of political participation working around state repression and civil society’s poor collective action. Citizen science may also potentially boost participation in particular policy fields (e.g., the Lebanese water sector; AUB, Citationn.d.).

Digital provision: Enabling more efficient governance, but for whom?

Digitalization can improve public services’ efficiency, create new digital deliverables, and bring along power shifts between existing and new actors. Examples from the MENA region show a highly diverse picture, between high connection rates and improved public services especially in the Gulf countries, and citizens’ exclusion from deliverables and thereby from (parts of) the social contract for groups with lower income and/or education levels or in remote or conflict-affected areas. This section gives insightful examples on these phenomena and analyses their potential as drivers of change to social contracts.

Studies on digitalization in the MENA region reveal challenges in ‘leaving no one behind’ and even large-scale e-governance deployments did not automatically increase interaction between the government and its citizens (for Jordan, see Kanaan & Masa’deh, Citation2018). Research points to three main reasons for the lacking adoption of e-governance/e-commerce services. First, citizens lack access (e.g., in Morocco’s ‘smart city’ initiative in Rabat, Mouttaki, Citation2021) often due to lacking digital literacy or internet connections. In Jordan, several e-services became mandatory (Alabdallat & Ardito, Citation2020) so that younger relatives or community centres needed to assist less tech-savvy Jordanians to file their e-tax return or pay public service providers (author’s interviews in Jordan, August 2019). Moreover, populations in conflict-affected areas are often cut off digital infrastructure, though potential gains are particularly high as e-services could connect across checkpoints and road closures and help to avoid unsafe transport options (for the Palestinian Territories, see GIZ, Citationn.d.). Second and third, the lack of independent regulatory agencies and, closely related to this, insufficient trust are key reasons for the low adoption of e-governance and e-commerce (Al-Kaseasbeh et al., Citation2019; Wood, Citation2022). For example, Syrian refugee women in a Jordanian refugee camp were highly sceptical about aid disbursement based on iris-scan and block-chain technologies because they considered these tools as ‘mish barakeh’ (‘not blessed’ by Islamic law; Cheesman, Citation2022, p. 25). Lacking trust in governmental e-services – a key concern in other countries (Teo et al., Citation2008) – is probably high in the MENA region, given authoritarian regimes’ electronic surveillance. In return, the use of digital services can also contribute to trust-building if they improve service performance and respond to citizens’ rather than governments’ priorities (like Jordan’s e-tax).

These examples show that the inclusive or exclusionary effects of digital provision on the social contract highly depend on the shaping of the other digital deliverables, i.e., protection and participation. Infrastructure, digital literacy, but also specific cultural needs need to be considered – depending as Gasmi et al. (Citation2023) state, on institutional reforms and investments in (digital) education. Conversely, when the regulation of e-services neglects marginalization effects, or where regimes abuse their digital power, this hinders trust in these new technologies. As Dhaoui (Citation2022, p. 2084) summarizes: ‘The huge public investment in ICTs, in the absence of a good governance framework that embodies accountable institutions, enlarges the voice of the elite which in turn can result in policy capture and greater state control’.

To be effective, investments in e-services for citizens or companies therefore need to be accompanied by offline governance reforms, especially since legal and institutional safeguards are particularly underdeveloped in many MENA countries (World Bank, Citation2022). Digital literacy and affordability of data services also need to be enforced (ibid). Moreover, state authorities themselves need to be better equipped and trained, both with respect to technical and to governance aspects, and to be better organized to avoid an overgrowth in digital bureaucracy (for Morocco see Zaanoun, Citation2023; Nachit et al., Citation2021). Overall, governance framework conditions irrespective of their digital aspects shape the effects of digital innovation on the social contract.

Furthermore, joint ventures or technology transfer for e-services often involve external actors and may thus widen the scope of the contract. The close cooperation between many MENA countries and China (Dotson, Citation2020) illustrates related opportunities and challenges. Chinese investments in MENA’s digital infrastructure contribute to the development of e-governance and economic development such as in smart agriculture, transportation and disaster relief (Aluf, Citation2022). But Chinese ownership of digital infrastructure and its massive data collection efforts also point to the geostrategic dimensions and China’s increasing power to control MENA countries and support their regimes. Again, the effects of foreign interference depend on adequate governance and transparent and accountable regulations. Governments’ failure in regulating private or governmental external actors may have unforeseen effects on their social contracts, for instance if external actors use their power to influence consumers’ behaviour or political attitudes.

These examples illustrate the potential of e-services for more efficient governance, but also the risk that digitalized provision in MENA’s social contracts continues to be shaped by the established, unequal patterns of power and interests. While technological developments create new opportunities for the renegotiation of social contracts, more comprehensive governance reforms and independent online and ‘offline’ regulation need to support this to be effective.

In sum, the effects of digitalization on all three types of deliverables in MENA social contracts are highly interdependent: E-governance (provision) gradually gains importance, but is torn between digital surveillance (protection) and digital activism (participation). This interdependency also has broader implications on digitalization as a driver of change: there are multiple links between the provision of digital tools and services and participation, but the outcome of their interaction can lead to more, but also to less opportunities for citizens to shape political life and renegotiate social contracts. Given the multiplicity of potential effects of digitalization on social contracts and their context-dependent outcomes (related, for instance to infrastructure and governance factors), it would require more empirical case-study research to make valid claims about causal relations. However, given the trends in the MENA region illustrated by the examples in this section, digitalization so far rather supports more exclusive and state-controlled social contracts than creating opportunities for inclusive renegotiation.

If MENA citizens primarily value digital provision,Footnote5 but do not actively call for better digital protection and are effectively held off digital participation, the ‘new’ digital social contracts of the region might be lower-cost versions of the ‘old’ populist-authoritarian social contracts (on the latter, see e.g., Loewe et al., Citation2021). In this view, the digital transformation would not lead to a change towards inclusive social contracts.

Conclusions

The impacts of digitalization on state–society relations are manifold and still evolving. The paper started by outlining how the ‘social contract lens’ helps to understand these effects to all elements of the social contract. It is a driver of change to the contract’s deliverables (‘the what?’), its modes of interaction (‘the how?’), as well as its actors and the geographical frames they operate in (‘the who and where?’). Focusing on changes in the delivered protection, participation and provision allowed to highlight inclusive and exclusionary effects on the contract and related trade-offs.

The paper’s second section on the specific situation in MENA illustrated that digitalization affects all three deliverables and that outcomes vary. Concrete effects of digitalization as a driver of change depend on how actively and successfully governments and societies shape it, and on the design and effectiveness of framework conditions such as infrastructure, budgets, education and, most importantly, governance. In the area of protection, MENA states seem to perform particularly badly when it comes to digital rights of citizens and the private sector, but also concerning their digital sovereignty. This lacking state performance on protection negatively affects economic development as well as the security of public infrastructure and citizens. In the MENA region like elsewhere, provision needs to include digital infrastructure accessible for all and related capacity development. The adoption of e-governance varies, but the available accounts on lacking regulation, transparency and accountability of digital services and policies reflects structural governance problems and often lead to low trust and use rates. Social media mobilization during the 2011 uprisings epitomized how digital tools provide new opportunities for participation in the region, but digital authoritarianism barred the way to potential benefits. Still, despite the crackdown on digital activism and difficulties to connect to offline mobilization, opposition movements are reorganizing themselves and constitute new also transnational alliances.

While digitalization is a potentially powerful driver of change for more participatory and inclusive social contracts, its influence in the MENA region seems to currently tilt towards more exclusive social contracts shaped by dominant actors. The relative power position of MENA governments who invested in digital surveillance overall increased. Due to repression and uneven digital skills, civil society’s organizational power and digital communication capacities could not compensate for lacking offline mobilization – particularly since the governments have much larger ‘offline capacities’, especially in the security sector.

Overall, the manifold effects of digitalization on state–society relations render the renegotiation of social contracts increasingly complex: faster, broader (due to new transnational and digital actors) and, overall, more erratic and unpredictable. Digital modes of interaction possibly lead to new changes or accelerate existing ones, but actors need to actively grasp the inherent opportunities and strategically shape their activities accordingly. As the MENA examples illustrated, in some cases, private domestic or foreign companies and other states have been much quicker in doing so than local governments, leading to another shift in power relations with unequal control over infrastructure, data, and communication.

Thus, digitalization can only be a driver of change towards more inclusive social contracts if it is actively shaped at the policy level. The impact of digitalization is impossible to shut out, so states and societies have to respond to these changes and need to understand and address how digitalization affects their respective social contract. The preservation of existing rights including Human Rights in the digital sphere, safeguards against the misuse of digital infrastructure by private companies, foreign states or criminals, and the development of digital infrastructure and literacy for all should be governmental priorities to fully reap the benefits of technological development for inclusive development. As this paper illustrated, opportunities in this sense are restricted where pre-existing governance conditions do not meet societies’ expectations.

Scientific research has a prominent role to play for better understanding the rapid evolution of social contracts under digitalization, as a basis for adequate policy responses. While a considerable body of literature exists on specific digital measures and their effects on individual policy fields, holistic approaches on digitalization as a driver of change to state–society relations and social contracts are much less developed. This paper also contributes to a better understanding of these relationships and thereby to elaborating what Glasius and Michaelsen (Citation2018, p. 3798) call the ‘political vocabulary to understand digital threats’. More research on the opportunities and challenges of these developments is needed, including, for instance, the interplay between online and offline activities and governance conditions. Furthermore, further research should systematically evaluate which of the above-identified effects of digitalization are particular relevant in which specific sector or policy area. As the positive and negative effects of digitalization also depend on pre-existing governance conditions and state–society relations (such as levels of trust in state authorities), further research should also look at reverse causality, that is, how the current state of a social contract influences the usage of digital tools and the digital transformation at large. Finally, research could also contribute to the development of better indicators, which account for not only the quantity but also the quality of provided e-services (similarly, Pirannejad et al., Citation2019). Such indices should rate e-services that allow for societal participation (e.g., user-generated content) rather than contingent services, only provided in return for loyal behaviour (‘social scoring’). Since digitalization has very different possible outcomes we need better analytic tools, like the social contract concept, to assess its dynamic impact on state–society relations. This is all the more important given the fast development of digital technologies and the unpredictable consequences of artificial intelligence. Just how transformative the impacts of digitalization will be, and how much social contracts will change also depends on pre-existing conditions and the extent to which contracting parties take it up for renegotiating their respective rights and duties.

Acknowledgements

We are most grateful to the participants of the workshop ‘Social Contracts in the MENA – Drivers of Change’ in summer 2022 and two anonymous reviewers for their very helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article. Research for this article was conducted in the project ‘‘Stability and Development in the Middle East and North Africa” funded by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ). The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not reflect the position of the BMZ.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. In contrast to the term digitization, which merely denotes the ‘creation of digital artefacts’ or turning analogue, paper-based information into digital bits and bytes, digitalization refers to much broader, also socioeconomic changes (e.g., Gradillas & Thomas, Citation2023). The term ‘digital transformation’ implies a mindset change and thus is still more encompassing than ‘digitalization’, but we use both terms interchangeably.

2. Please see the introductory article of this special issue for further details on the approach and its embedding into history and academic literature.

3. The Global Cybersecurity Index (GCI, developed by United Nations’ specialized agency for ICT) measures especially ‘the commitment of countries to cybersecurity at a global level’ (ITU, no year), thus ignoring protection on a (sub)national level. The Freedom House Internet Freedom Score fills this void by measuring obstacles to access, limits on content and violations of user rights. Relating to provision, the UN’s E-government development index (EGDI) measures online services, telecommunication infrastructure and human capital (but not in terms of digital skills). Concerning participation, the UN’s E-Participation Index (EPI) is highly contested (Pirannejad et al., Citation2019) as it measures only the quantity, not the quality of e-participation. It ignores civil society’s bottom-up e-participation, and is blind to authoritarian moves to use participative formats to rather control (e.g., through ‘social scoring’) than to enable societal e-participation.

4. In all social contracts, the use of digital surveillance needs to be negotiated, but misuse of it is most likely in authoritarian states, where it can gradually become one of the main, yet lopsided features of the protection deliverable.

5. A recent survey suggests that citizens in Egypt, Lebanon and Tunisia indeed prioritize provision over protection and participation (Loewe & Albrecht, Citation2021).

References

- Access Now. (2021). New middle east and North Africa coalition to combat digital surveillance, 8 July, Available at Retrieved May 5, 2023, from https://www.accessnow.org/press-release/new-middle-east-and-north-africa-coalition-to-combat-digital-surveillance/

- Alabdallat, W., & Ardito, L. (2020). Toward a mandatory public e-services in Jordan. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1727620

- Al-Kaseasbeh, H. M., Harada, Y., & Saraih, U. N. (2019). E-government services assessment from the perspective of citizens interaction and satisfaction in Jordan: Pilot study. International Journal of Research, 6(12), 50–60.

- Allouche, Y. (2020, August, 15). Coronavirus: Pandemic united Maghreb leaders in crackdown on dissent. MiddleEasteye. Retrieved May 12, 2023, from https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/maghreb-crackdown-dissent-coronavirus-algeria-morocco-tunisia

- Al-Rawi, A. (2014). Cyber warriors in the Middle East: The case of the Syrian electronic army. Public Relations Review, 40(3), 420–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2014.04.005

- Al-Rawi, A., & Iskandar, A. (2022). News coverage of the Arab spring: State-run news agencies as discursive propagators of news. Digital Journalism, 10(7), 1156–1177. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2021.1987946

- Aluf, D. (2022, November, 17). China’s tech outreach in the middle East and North Africa. The Diplomat. Retrieved May 5, 2023, from https://thediplomat.com/2022/11/chinas-tech-outreach-in-the-middle-east-and-north-africa/

- Aouragh, M. (2016). Online politics and grassroots activism in Lebanon: Negotiating sectarian gloom and revolutionary hope. Contemporary Levant, 1(2), 125–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/20581831.2016.1241399

- AUB (American University Beirut. (n.d.). Citizen science, Retrieved April 7, 2023, from https://www.aub.edu.lb/natureconservation/Pages/citizenscience.aspx

- Ayish, M. (2018). A youth-driven virtual civic public sphere for the Arab world, Javnost - the public. Journal of the European Institute for Communication and Culture, 25(1–2), 66–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/13183222.2018.1418794

- Banaji, S., & Moreno-Almeida, C. (2021). Politicizing participatory culture at the margins: The significance of class, gender and online media for the practices of youth networks in the MENA region. Global Media and Communication, 17(1), 121–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742766520982029

- Bante, J., Helmig, F., Prasad, L., Scheu, L. D., Seipel, J. C., Senkpiel, H., Geray, M., von Schiller, A., Sebudubudu, D., & Ziaja, S. (2021). E-government and democracy in Botswana. Observational and experimental evidence on the effects of e-government usage on political attitudes. (Discussion paper 16). German Development Institute/Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik.

- Brach, J. (2020). Security implications of emerging technological challenges in North Africa. NATO OPEN Publications, 4(1), 1–28.

- Bradshaw, S., & Howard, P. N. (2019). The global disinformation order: 2019 global inventory of organised social media manipulation. Oxford Internet Institute, University of Oxford.

- Breuer, A., Landman, T., & Farquhar, D. (2015). Social media and protest mobilization: Evidence from the Tunisian revolution. Democratization, 22(4), 764–792. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2014.885505

- Brynjolfsson, E. (2022). The turing trap: The promise & peril of human-like artificial intelligence. Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 151(2), 272–287. https://doi.org/10.1162/daed_a_01915

- Charrad, M. M., & Reith, N. E. (2019). Local solidarities: How the Arab spring protests started. Sociological Forum, 34(S1), 1174–1196. https://doi.org/10.1111/socf.12543

- Cheesman, M. (2022). Infrastructure justice and humanitarianism: Blockchain’s promises in practice [ PhD thesis]. Oxford Internet Institute, University of Oxford.

- de Melo, J., & Solleder, J. (2022). Structural transformation in MENA and SSA: The role of digitalization. ERF working paper 1547.

- Dhaoui, I. (2022). E-government for sustainable development: Evidence from MENA countries. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 13(3), 2070–2099. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-021-00791-0

- Dotson, J. (2020). The Beidou satellite network and the “space silk road” in Eurasia. China Brief, 20(12), 2–8.

- Douzet, F., Pétiniaud, L., Salamatian, K., & Samaan, J. (2022). Digital routes and borders in the Middle East: The geopolitical underpinnings of internet connectivity. Territory, Politics, Governance (6), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2022.2153726

- El-Darwishe, B., & McPherson, A. (2022). The digital services acts package and what it entails. PwC, Retrieved August 11, 2023, from https://www.pwc.com/m1/en/publications/documents/the-digital-services-acts-package.pdf

- Fatafta, M., & Samaro, D. (2021). Exposed and exploited: Data protection in the Middle East and North Africa. AccessNow. Retrieved May 12, 2023, from https://www.accessnow.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Access-Now-MENA-data-protection-report.pdf

- Gasmi, F., Kouakou, D., Noumba Um, P., & Rojas Milla, P. (2023). An empirical analysis of the social contract in the MENA region and the role of digitalization in its transformation. Toulouse school of economics working paper 1423.

- GIZ. (n.d.). Designing inclusive digital governance (INDIGO). E-Governance in Palestine and the MENA region, Retrieved November 12, 2022, from https://www.giz.de/en/worldwide/120433.html

- Glasius, M., & Michaelsen, M. (2018). Authoritarian practices in the digital age. Illiberal and authoritarian practices in the digital sphere — prologue. International Journal of Communication, 12, 3795–3813.

- Gradillas, M., & Thomas, L. (2023). Distinguishing digitization and digitalization: A systematic review and conceptual framework. Journal of Product Innovation Management. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12690

- GSMA. (2020). Connected society: The state of Mobile internet connectivity 2020.

- GSMA. (2023). The Mobile economy middle east & north africa 2023.

- Heydemann, S. (2007). Upgrading authoritarianism in the Arab world. Analysis paper of the Saban Center for Middle East policy No 13.

- Houdret, A., Kadiri, Z., & Bossenbroek, L. (2017). A new rural social contract for the Maghreb? The political economy of access to water, land and rural development. Middle East Law and Governance, 9(1), 20–42. https://doi.org/10.1163/18763375-00901003

- ictQatar (Qatari Ministry of ICT). (2014). The attitudes of online users in the MENA region to cybersafety, security and data privacy, report.

- ITU (International Telecommunication Union. (n.d.). Global cybersecurity index. Retrieved February 15, 2023, from https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Cybersecurity/Pages/global-cybersecurity-index.aspx

- Josua, M., & Edel, M. (2021). The Arab uprisings and the return of repression. Mediterranean Politics, 26(5), 586–611. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2021.1889298

- Kanaan, R. K., & Masa’deh, R. (2018). Increasing citizen engagement and participation through eGovernment in Jordan. Modern Applied Science, 12(11), 351–357. https://doi.org/10.5539/mas.v12n11p351

- Karolak, M. (2020). Social media in democratic transitions and consolidations: What can we learn from the case of Tunisia? The Journal of North African Studies, 25(1), 8–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629387.2018.1482535

- Kharroub, T. (2022). Mapping digital authoritarianism in the Arab world. Retrieved May 12, 2023, from https://arabcenterdc.org/resource/mapping-digital-authoritarianism-in-the-arab-world/,

- Kokolakis, S. (2017). Privacy attitudes and privacy behaviour: A review of current research on the privacy paradox phenomenon. Computers & Security, 64, 122–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cose.2015.07.002

- Lawrie, O. (2021). Western democracy in the information age: Online discourse and the infeasibility of regulation. The Greater European Journal, 3(1), 27–34.

- Leenders, R. (2016). Transnational diffusion and cooperation in the Middle East (pp. 16–20). POMEPS Studies 21.

- Loewe, M., & Albrecht, H. (2021). The social contract in the middle East and North Africa: What do the people want?. Paper Presented at the Virtual 55th Annual Meeting of the Middle East Studies Association, Tucson, AZ, USA, November 29–December 3.

- Loewe, M., El-Haddad, A., Furness, M., Houdret, A., & Zintl, T. (in press). Drivers of change in social contracts: Fundamentals of a conceptual framework. Mediterranean Politics. [In this special issue].

- Loewe, M., Zintl, T., & Houdret, A. (2021). The social contract as a tool of analysis: Introduction to the special issue on “framing the evolution of new social contracts in Middle Eastern and North African countries. World Development, 145, 104982. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.104982

- Lynch, J. (2022). Iron net: Digital repression in the middle east and North Africa, policy brief. European Council on Foreign Relations/ECFR.

- Maati, A., Edel, M., Saglam, K., Schlumberger, O., & Sirikupt, C. (2023). Information, doubt, and democracy: How digitization spurs democratic decay. Democratization.

- Maerz, S. F. (2016). The electronic face of authoritarianism: E-government as a tool for gaining legitimacy in competitive and non-competitive regimes. Government Information Quarterly, 33(4), 727–735. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2016.08.008

- Mayer, M., & Lu, Y. (2022). Digital autonomy? Measuring the global digital dependence structure. Center for Advanced Security, Strategic and Integration Studies.

- Monshipouri, M. (2021). Social transformation in a digital age: Youth social movements in the MENA region. IEMed.

- Moreno-Almeida, C. (2021). Memes as snapshots of participation: The role of digital amateur activists in authoritarian regimes. New Media & Society, 23(6), 1545–1566. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820912722

- Moreno-Almeida, C., & Banaji, S. (2019). Digital use and mistrust in the aftermath of the Arab Spring: Beyond narratives of liberation and disillusionment. Media Culture & Society, 41(8), 1125–1141. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443718823143

- Mouttaki, A. (2021). La digitalisation de Rabat au prisme de la participation citoyenne, Revue internationale animation, territoires et pratiques socioculturelles. Revue internationale animation, territoires et pratiques socioculturelles, 20(20), 27–44. https://doi.org/10.55765/atps.i20.1194

- Nachit, H., Jaafari, M., El Fikri, I., & Belhcen, L. (2021). Digital transformation in the Moroccan public sector: Drivers and barriers. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3907290

- Noman, H. (2019). Internet censorship and the intraregional geopolitical conflicts in the Middle East and North Africa. Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society Research Publication Series, Retrieved May 12, 2023, from https://cyber.harvard.edu/story/2019-01/internet-censorship-and-intraregional-geopolitical-conflicts-middle-east-and-north

- Open Government Partnership. (n.d.). Members. Retrieved November 11, 2022, from https://www.opengovpartnership.org/our-members/

- Pasquale, F. (2015). The black box society. The secret algorithms that control money and information. Harvard University Press.

- Paul, M., Upadhyay, P., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2020). Roadmap to digitalisation of an emerging economy: A viewpoint. Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy, 14(3), 401–415. https://doi.org/10.1108/TG-03-2020-0054

- Pirannejad, A., Janssen, M., & Rezaei, J. (2019). Towards a balanced e-participation index: Integrating government and society perspectives. Government Information Quarterly, 36(4), 101404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2019.101404

- Roberts, T. (Ed). (2021). Digital rights in closing civic space: Lessons from Ten African countries. Institute of Development Studies.

- Rutherford, B. (in press). Understanding change in Egypt’s social contract since 2011. Mediterranean Politics. [In this special issue].

- Satariano, A. (2022, April 22). E.U. Takes aim at social media’s harms with landmark New Law. New York Times. Retrieved May 15, 2023, from https://www.nytimes.com/2022/04/22/technology/european-union-social-media-law.html

- Schlumberger, O., Edel, M., Maati, A., & Saglam, K. (2023). How authoritarianism transforms: A framework for the study of digital dictatorship. Government and Opposition, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2023.20

- Sreberny, A. (2015). Women’s digital activism in a changing middle east. International Journal of Middle East Studies, 47(2), 357–361. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020743815000112

- Suhardi, S., Sofia, A., & Andriyanto, A. (2015). Evaluating e-government and good governance correlation. Journal of ICT Research and Applications, 9(3), 236–262. https://doi.org/10.5614/itbj.ict.res.appl.2015.9.3.3

- Teo, T. S. H., Srivastava, S. C., & Jiang, L. (2008). Trust and electronic government success: An empirical study. Journal of Management Information Systems, 25(3), 99–132. https://doi.org/10.2753/MIS0742-1222250303

- Türcke, C. (2019). Digitale Gefolgschaft. Auf dem Weg in eine neue Stammesgesellschaft. CH Beck.

- Wagner, K. M., Gainous, J., Warnersmith, A., & Warner, D. (2023). Is the MENA surfing to the extremes? Digital and social media, echo chambers/filter bubbles, and attitude extremity. International Journal of Communication, 17, 405–425. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc

- Wood, C. A. (2022). Chapter 11: Digital technology adoption in the Middle East and North Africa: Trust and the digital paradox. In F. Belhaj, R. Gatti, D. Lederman, E. J. Sergenti, H. Assen, R. Lotfi, & M. E. Mousa (Eds.), A new state of Mind; greater transparency and accountability in the Middle East and North Africa (pp. 205–222). MENA Economic Update (World Bank Group).

- World Bank. (2022). Leveraging data to foster development: Where does the MENA region stand?, insights from the world development report 2021.

- Zaanoun, A. (2023). Morocco: The impact of the digitization of public services. Arab Reform Initiative.