ABSTRACT

This longitudinal study aims to create in-depth knowledge about the phenomena of middle-leadership and career in school by identifying (1) driving forces for seeking and maintaining middle-leading positions, (2) opportunities and difficulties in maintaining the middle-leading role over time, and (3) underlying thoughts of career disclosed in the respondents’ expressions. Five different reasons for seeking middle-leading positions are identified and driving forces for maintaining the position are categorised as either internal reward/non-observable outcomes or external reward/observable outcomes. Furthermore, the results show that different types of difficulties arise in distinct phases and that middle-leaders’ needs for support therefore vary over time. Additionally, the complexity of teachers’/middle-leaders’ career thinking clearly emerges, and implications for practice are discussed.

Introduction

Increasingly, the phenomenon of teacher leadership/middle-leadershipFootnote1 as a key component in school reform has gained attention as a plausible means by which instructional improvement can be achieved (Harris and Jones Citation2017; Wenner and Campbell Citation2017). Behind this lies an assumption that leadership distributed over those who still have a practical foundation in the activities they are intended to lead will have a direct and positive impact on practice. Moreover, based on arguments for the importance of attracting and retaining high-quality teachers in the profession, it is assumed that career paths are important. Appointing teachers as leaders of development processes at local schools is regarded as a way of making the teaching profession more attractive (Wenner and Campbell Citation2017). In Sweden – the context of the present study – a reform introducing a new career path for teachers was launched in 2013, and from then onwards, approximately 15,000 Swedish teachers have received formal, relatively well paid, middle-leading positions, often entailing responsibility for leading local school-development processes and assignments as supervisors of colleagues (Swedish Ministry of Education Citation2012; SNAE [Swedish National Agency for Education] Citation2017).

An underlying logic in reports underpinning such reforms is that career opportunities appeal to teachers (see e.g. OECD Citation2005, Citation2015; Swedish Ministry of Education Citation2017). However, the very concept of career often remains unproblematised, and little account is taken of the fact that research within the career field has revealed that career as both concept and phenomenon has been subject to profound changes during the twenty-first century (Bergmo-Prvulovic Citation2015). Moreover, still little is known about how teachers imagine and perceive career-making, or what it means to have middle-leading positions in terms of challenges over time entailed by the changed division of labour. In Sweden, as well as in many other countries, the division of labour between teachers has traditionally been characterised by an egalitarian norm (Brosky Citation2011; Hjalmarsson and Löfdahl Hultman Citation2016), which, we argue, is challenged when the frequency of teachers in middle-leading positions increases.

Drawing on the empirical questions below, this longitudinal study aims to create in-depth knowledge about the phenomenon of middle-leadership in school from a career perspective:

What driving forces are described by teachers for seeking and maintaining middle-leading positions?

What underlying thoughts and ideas of career are disclosed in teachers’ expressions?

What opportunities and difficulties in relation to maintaining the middle-leading role become visible over time?

Conceptual framework

This study is framed by the activity-theoretical understanding of the concept division of labour, comprising both a horizontal and a vertical dimension; that is, the division of labour determines the work tasks and powers of the members in a community. Here, the horizontal dimension refers to the distribution of tasks and assignments between middle-leaders and other teachers, while the vertical refers to changes in status and power vis-à-vis colleagues that the middle-leading position entails (Engeström Citation2001; Hirsh Citation2013).

The meaning of career – an elusive concept

In everyday life, people seem to have a tacit agreement about the meaning of career (Collin Citation2007). Career is commonly described as a person’s continuous advancement and promotion within a certain vocational area, often with emphasis on the success related to promotion (Savickas, Citation2008). However, in the broad field of career studies, the meaning is not so easily defined. The field, with its different orientations, exhibits internal differences with respect to emphasis as well as interpretation (Collin Citation2007; Kidd Citation2006). The labour market orientation emphasises a rational matching perspective; the career guidance orientation emphasises individuals’ needs, dreams and goals; and the business and organisational orientation emphasises organisational needs (Bergmo-Prvulovic Citation2017, Citation2018). Alongside these contrasting orientations to career, people in everyday life tend to refer to career in line with both a personal meaning, referring to personal values, dreams and goals, and a social meaning (see cf. Bergmo-Prvulovic Citation2013), referring to the dominant metaphor of career as ‘climbing the ladder’ (Savickas Citation2008).

The transition to a globalised knowledge society has led to a gradual transformation in the understanding of the meaning of the career concept, with attempts to replace the traditional meaning of career with conceptions such as ‘protean careers’ (Hall Citation1996) and ‘boundaryless careers’ (Arthur and Rousseau Citation1996). Accordingly, new ways of speaking about career with the intention to transform its meaning to better fit a changing society have influenced both public debate and European Union (EU) policy texts concerned with career (see e.g. Bergmo-Prvulovic Citation2015). Such attempts contain expressions emphasising personal responsibility for shaping one’s career and keeping oneself employable and flexible, rather than expressions referring to the traditional view of career as hierarchical climbing.

Career as social and professional representation

The interpretative analysis of underlying thoughts and ideas of career in the current study is informed by a framework of career as social and professional representations (Bergmo-Prvulovic Citation2015) derived from social representations theory.

Moscovici (Citation1973) describes social representations as a

system of values, ideas and practices with a twofold function; first, to establish an order which will enable individuals to orientate themselves in their material and social world and to master it; and secondly to enable communication to take place among members of a community by providing them with a code for social exchange and a code for naming and classifying unambiguously the various aspects of their world and their individual and group history. (p. xiii)

Thus, the theory is concerned with how beliefs are constructed and become everyday knowledge among people. Professional representations (Ratinaud and Lac Citation2011) are regarded as a specific category of social representations that develop in professional interaction by those whose professional identities they form. Ratinaud and Lac argue that professional activities are regulated by professional conceptual maps that represent ideas that are common within a certain professional group. In that way, they represent a professional reality. Moscovici (Citation2001) claims that social (and professional) representations function as a tool of thought, if there is consensus about the representations. However, when a group and/or the thoughts about a certain phenomenon that is shared within the group undergo change, peoples’ everyday commonly shared knowledge – that hitherto was taken for granted – is challenged. In this study, it is assumed that the implementation of the above-mentioned career-teacher reform from 2013 represents changing conditions that might challenge what has hitherto been taken for granted in the professional group of teachers.

The framework of career as social and professional representations (Bergmo-Prvulovic Citation2015) was initially developed based on studies of how the concept and phenomenon of career was understood by (a) a group of people (with different professional backgrounds) who had recently undergone or were currently undergoing work-related changes, and (b) a group of career guidance professionals. The studies revealed that the first-mentioned were bearers of social representationsFootnote2 and that the group of career guidance professionals were bearers of both social and professional representationsFootnote3. The social representations that commonly appeared and were stable in both groups were career as individual project and self-realisation and career as social/hierarchical climbing. The first group, who were undergoing work-related changes, also expressed the representation career as a game of exchange. Within the representation career as a game of exchange, several pairs of opposites were revealed, suggesting a two-sidedness to the representation. In particular, the pairs of oppositesFootnote4 expressing expected effort–expected outcome and internal reward–external reward showed how the respondents understood career as a mutual exchange between themselves and the employing organisation (Bergmo-Prvulovic Citation2017).

Since this study concerns the professional group of teachers, it is assumed here that they are bearers of social representations, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, professional representations that specifically derive from their professional identity as teachers.

Literature review

A changed division of labour in school – difficulties and opportunities

In their research review on teacher leadership, York-Barr and Duke (Citation2004) conclude that teachers in middle-leading positions tend to feel isolation and conflict when the division of labour changes from primarily horizontal to somewhat vertical, and they argue that this is a consequence of traditional professional norms of egalitarianism, individualism and isolation in the profession. Similarly, in a more recent research review, Wenner and Campbell (Citation2017) point out that relationships with colleagues are often affected negatively when teachers enter middle-leading positions because of disruption of the egalitarian norm typically seen in schools. There are numerous examples in research of resentment and resistance taking the expression of peers deliberately trying to counteract the success of those taking on middle-leading roles (see, e.g. Brosky Citation2011; Hirsh and Segolsson Citation2017; Hjalmarsson and Löfdahl Hultman Citation2016; Margolis and Doring Citation2012). Brosky (Citation2011) and Chamberland (Citation2009), moreover, imply that some teachers in middle-leading positions are so strongly influenced by the traditional horizontal structures in the profession that it is hard for them to maintain the middle-leading role.

There is, however, also research pointing out that teachers in middle-leading positions are positive about their assignment and describe themselves as highly motivated, empowered and professionally satisfied with their work (Alvunger Citation2015; Wenner and Campbell Citation2017). Recognition strongly contributes to middle-leaders’ sense of empowerment and satisfaction, both in the form of monetary compensation (Borchers Citation2009) and through appreciation shown by colleagues and the principal (see e.g. Hirsh and Segolsson Citation2017). Furthermore, the study by Hirsh and Segolsson (Citation2017) showed that the changed division of labour, where middle-leaders had special responsibilities for demanding and time-consuming tasks in analyses of instruction, was crucial for the possibility to engage all teachers at the studied school in ‘collaborative learning’.

Motivation and aspiration

Studies exploring logics behind people’s decisions to become teachers in the first place (Kyriacou and Coulthard Citation2000; Moran et al. Citation2001) suggest that motivation can be related to altruistic factors (teaching as socially worthwhile; a desire to help; a calling), intrinsic factors (interest in the activity of teaching and/or in a specific subject), and extrinsic factors (length of holidays, level of pay, status, etc.), where the altruistic and intrinsic motivators are the most prominent in the Western world (Ganchorre and Tomanek Citation2012; Moreau Citation2014).

Corresponding studies about what leads in-service teachers to become middle-leaders or about whether and how the role as a leader of colleagues in school-development processes is perceived as a career step are harder to find. York-Barr and Duke briefly mention in their review (Citation2004) that teachers who are drawn to leadership positions are generally achievement and learning oriented, are typically in mid-career and mid-life, and have significant teaching experience. Wenner and Campbell’s review (Citation2017) touches upon the issue when motivating why research into teacher leadership is important in relation to the challenge of teacher attrition. Donaldson (Citation2007) and Donaldson et al. (Citation2005) suggest that one reason for teachers leaving the profession is a perceived lack of challenges in their career trajectory. Edwards Groves and Rönnerman (Citation2013) claim that ‘a will to do good’ for children/students and colleagues motivated the teachers in their study to maintain the function of leaders of development processes at their schools and pre-schools.

In a study of teachers’ aspirations in general for development in their profession, Avidov-Ungar (Citation2016) distinguishes between their aspirations for lateral development (expansion of knowledge, skills and responsibilities) and for vertical development (climbing the hierarchical ladder). She identifies teachers’ professional development motivation as either intrinsic or extrinsic and their aspirations as either lateral or vertical. Based on this, she discusses four professional development patterns, referred to as hierarchically ambitious, hierarchically compelled, laterally ambitious and laterally compelled. In another study, Avidov-Ungar and Arviv-Elyashiv (Citation2018) studied 663 Israeli teachers’ aspirations specifically for vertical development (i.e. promotion and hierarchical advancement) during the implementation of a new reform involving the creation of a number of new middle-leading positions. Included participants were all taking part in a continuous professional development initiative (studying for a masters in education degree). Results show that as many as four-fifths of the teachers desired a promotion to a leading position.

Contextualising the present study

A new clause was added to the Swedish Education Act in 2013 stating that school facilitators should seek to establish a career step for particularly skilled teachers titled ‘lead teachers’. In a 2012 memorandum (Swedish Ministry of Education Citation2012), the reform is described as a way to strengthen the quality of instruction and as a way to make the profession attractive, thus also counteracting teacher attrition. To be considered for a lead teacher position, one must have shown particularly good ability to improve students’ academic performance and a strong interest in developing instruction. It is emphasised that lead teachers largely continue to work as regular classroom teachers but have specific, additional responsibility for, for instance, development projects and supervision of colleagues. The lead teacher position is accompanied by a relatively large wage increase, which distinguishes it from already existing middle-leading positions among teachers, where wage increases have been considerably smaller and of rather symbolic significance.

Sweden has never had so many teachers in formal middle-leading positions as in the period following the lead-teacher reform. Due to its novelty, however, there is still limited research-based knowledge of various implications of the reform. Existing research and evaluations (see, e.g. Alvunger Citation2015; Öhman et al. Citation2016; SNAE Citation2014, Citation2015) carried out at an early stage of the reform’s implementation point to problems such as great uncertainty about the role and tasks of lead teachers, which can be linked to the very novelty of the reform.

We suggest that the rather drastic changes in the division of labour entailed by middle-leadership in schools, in Sweden and internationally, motivate further studies. Research located at the intersection of the teacher-leadership field and the career field is potentially important for several stakeholders within the area of education (e.g. national and local policy makers, school principals, teachers, and those involved in teacher training) as well as for stakeholders within the area of human resources (e.g. those working with processes of attracting, recruiting, retaining and rewarding professionals).

Method and materials

The school where the respondents work is a secondary school with approximately 800 students and 70 teachers. Over the course of two school years (autumn 2015 to spring 2017), the school’s principal and all teaching staff worked in a school-development project aimed at improving teachers’ classroom practices in the context of formative assessment and adaptive instruction. The work in the project was planned and led by a development group consisting of the school’s principal and lead teachers. At the start of the project, the teachers had held their lead-teacher positions for one year, during which the school had attempted to work with a few shorter, school-based initiatives in which the lead teachers served as moderators in subject-specific dialogue groups. During that initial year, the lead teachers received meta-supervision regarding their experiences of being moderators for groups of colleagues.

Prior to the autumn of 2015, the school’s principal decided that the school should engage in a long-term, school-development project, one that would continue for longer than previous projects had done. The content of the project was the desire of the entire teaching staff, while the forms for it were suggested and elaborated by the development group. The planning phase of the project lasted one semester, and the operational phase lasted three semesters. During the operational phase, the lead teachers (i.e. the respondents in the current study) functioned as leaders and supervisors in peer groups consisting of seven to nine colleagues. Two researchers followed the work in the project over the two years of the planning and operational phases.

From here on, we will use the term middle-leaders when referring to the lead teachers.

Participants and data collection

Data consisted of individual interviews with the middle-leaders on three occasions during the project and continuously written self-reflections by all of them. In their self-reflections, participants could express anything related to how the work in the project proceeded, but they were instructed to pay special attention to describing their leading role and their feelings associated with that role as well as situations and periods when they experienced frustration or flow.

Up until the summer of 2016, there were 10 middle-leaders at the school, but by the start of the autumn semester in 2016, 1 of them (Teacher A in ) left her job to work at another school. The rest of the respondents remained for the whole project.

Table 1. Participants of the study.

Below, participants () and collected data () are described in detail.

Table 2. Data collection.

Data analysis

All data were analysed, on both manifest and latent levels, following Hällgren Graneheim and Lundman’s (Citation2004) qualitative content analysis approach. The entire data set was considered the unit of analysis in which meaning units were sought. Meaning units are here understood as content areas identified with little interpretation (manifest level), shedding light on specific areas of content responding to the research questions. The meaning units were subsequently condensed – that is, shortened while still preserving their core meaning – and labelled with codes. The codes from interviews and self-reflections were sorted into groups sharing a commonality, resulting in various categorisations.

Lastly, the meaning units were explored in a final (latent) step for the purpose of revealing underlying thoughts and ideas of career or career development. This part of the analysis was guided by the analysis question What expressions refer to assumptions about career or career development, either directly or indirectly, and informed by the previously described framework of career as social and professional representations (Bergmo-Prvulovic Citation2015). A social representation theory approach suggests that a social/professional representation is formed by its constitutive elements (cf. e.g. Abric Citation1995; Moscovici Citation2001), such as sets of utterances by people which reveal characteristics and symbolic or iconic expressions that contribute to the formation of the social/professional representations of the object concerned (here career). The content analysis serves as a base for the search of such constitutive elements, where an inductive exploration of common elements among the codes resulted in constitutive elements. The content in these elements was finally explored, throughout the utterances and codes, in terms of socially and professionally shared knowledge, which finally generated the resulting social/professional representations.

Results

The results section is divided into four parts, the first two of which concern research question 1. The third part concerns research question 2, while the fourth part deals with research question 3. As previously described, the empirical analyses made in relation to research questions 1 and 3 are on a manifest level, meaning that our ambition has been to search for patterns and create descriptive categories, based on an inductive analysis of the data material. Categorizations and figures created to illustrate categorizations are spun from empirical patterns found rather than theory. In the case of research question 2, on the other hand, where underlying (latent) thoughts and ideas of career were sought, the analysis has been informed by the framework of career as social and professional representations.

Driving forces behind seeking a middle-leading position

In the first set of interviews, nine out of 10 respondents described that they had felt hesitant about applying for a middle-leading position. Some expressed scepticism about the reform as such as well as the title ‘lead teacher’, while others expressed doubts because they perceived the position to be vaguely defined. All nine described that they felt ambivalent due to fear of colleagues’ reactions:

No, but it was kind of … something new, that we hadn’t seen before in school … that some teachers were to be chosen as more skilled than others. … I predicted that it might create conflicts among the teaching staff … and that some colleagues might react negatively … [with] jealousy and bitterness … and because of that, I really hesitated before applying. (Teacher B)

All of them, however, subsequently chose to apply. In the categorisation of the respondents’ statements, five reasons for applying for a lead-teacher position emerge, as described in . Some respondents indicate more than one reason: for example, both curiosity and a need to be challenged.

Table 3. Reasons for applying for a middle-leading position.

Driving forces for maintaining the middle-leading position

At the school studied, no extra time was allocated for the middle-leading assignment; instead, the respondents performed it in addition to working as regular classroom teachers on a full-time basis. The following part of the results concerns issues of what motivates them to make the extra effort.

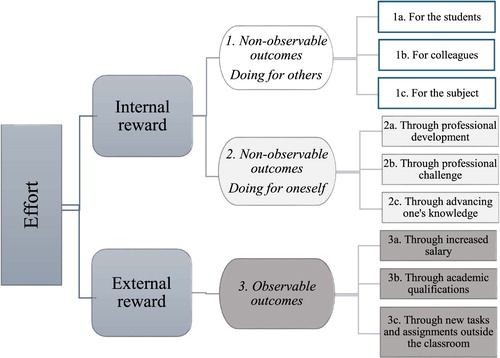

The analysis shows that they feel rewarded for their work in several ways. As a first step, we drew a dividing line between internal reward/non-observable outcomes and external reward/observable outcomes. The category of internal reward was then further divided into two distinct subcategories, based on statements about doing good for others and statements about doing good for oneself. Lastly, the 3 subcategories (1, 2 and 3 in ) were sorted into a second level of subcategories (1a/b/c, 2a/b/c, 3a/b/c).

As shown in , the second-level subcategories capture more specific aspects of the observable and non-observable outcomes that emerge from the manifest data analysis. In each of the subcategories is illustrated by a quote.

Table 4. Subcategories of non-observable and observable outcomes.

Underlying thoughts and ideas of career

As mentioned previously, a basic assumption in the present study is that the 10 respondents, all of whom belong to the same professional group, are bearers of both social representations of career on the one hand, and professional representations that derive from their professional identity as teachers on the other. In order to reveal underlying thoughts and ideas of career, we undertook an inductive search for common and constitutive elements in the data material. The content in these elements was subsequently explored in terms of socially and professionally shared knowledge, which, in turn, generated one overriding social representation, and three professionally shared representations.

Based upon the categorisation and the expressions presented in the results above, the social representation of career as a game of exchange (Bergmo-Prvulovic Citation2013) appears to be the overriding representation of career guiding the teachers’ thoughts and ideas. The middle-leading assignment involves extra effort, and participants’ motivations vary. Entering and upholding the role ‘pays off’ through a number of rewards, which are expressed in various ways by the respondents as important. Moreover, the categories of internal reward and external reward also reveal three different professional representations (see Ratinaud and Lac Citation2011) of career in this specific group. Under the category of internal reward and its first subcategory of non-observable outcomes, we identify a professional representation of career as a mission carried out for others. The second subcategory reveals a professional representation of career as inner professional satisfaction. As for the category of external reward, a professional representation of career as visible professional recognition emerges. Consequently, we observe an interplay between the social representation of career as a game of exchange and the three professional representations identified within this specific community of teachers.

Developing in one’s role – opportunities and difficulties

In the current study, the respondents were followed for two school years, during which they certainly developed in their role as leaders of colleagues in school-developing processes. (below) is our way of capturing and illustrating this longitudinal process. The initial stage of having middle-leading assignments was described at the first interview round, where respondents looked back on their first year in their new role. In the second interview round, six months later, it was clear that the respondents described their role in a different way, interpreted by us as mirroring a progression. At the last interview round, another nine months later, the respondents’ descriptions generally show that the assignment and the role have begun to be consolidated.

All respondents describe a challenging and difficult initial stage. The total data set, however, indicates that after two years, all except two appear to at least have reached what is referred to as the progressing stage and are approaching the consolidating stage (see ).

Teacher J, even though she stayed in her middle-leading position, never articulated feeling confident or claiming her role; and teacher A left her assignment before reaching the progressing stage. In her last self-reflection she wrote:

I think I said this in the interview already, but it has become even clearer to me now. It’s not the salary that motivates me, nor the possibility of career, and I really don’t think I’m better than anyone else. It’s obvious that what drives me is the desire to help students grow. Therefore, I will move on to another job now, which only involves teaching and no lead-teacher role. (Teacher A)

The struggles in the initial stage are linked to a certain extent to the fact that the middle-leading assignment is not clearly defined and given. Instead, it is being shaped and refined over time. Largely, however, initial difficulties and struggles described by most respondents relate to colleagues’ resentment and resistance:

The worst part of this is comments from colleagues; they are painful sometimes … . it’s like bullying among adults. … Once I took a bowl of candy with me to my group, just to be nice … then one colleague said ‘Wow, some of us have so high salary that they can afford to buy candy for others’. (Teacher D)

At the second and third interview round, it is obvious among most respondents that development has taken place:

It is very comforting to have the other lead-teachers to talk to and to have had the meta-supervision sessions … . It helps you to sort of develop an armour against these resentful comments. … The comments are fewer now. They probably see that we are doing a lot of work … and as we learn more we also become more confident in our roles. (Teacher B)

I’ve developed a lot … and that’s because the assignment is so much clearer now than before. Initially, it was very unclear what my mission was. … I sort of had to try to shape it on my own. … With this project, it has become clear, and now I dare to really take on the lead-teacher role. I sort of feel that I have the mandate now. … And the fact that we are taking this course now, about school development, it’s a perfect combination. It gives me so much food for thought and makes me feel much more comfortable in my role. (Teacher E)

In the beginning, I was quite nervous and stiff as a group leader. I was very particular about the outer structures, like keeping to the time frames exactly and such things … . Now I have sort of internalised the structure … . I feel more in situ and listen better to what others say. … Before, my focus was mostly on ‘Am I doing the correct thing now?’ and ‘What’s the next point on the agenda?’. (Teacher C)

Based on analysis of the whole data set, it is possible to argue that diverse types of challenges arise at the various stages and that middle-leaders’ needs for support therefore vary over time. Appearing as important in the initial stage are the principal’s outspoken support and the clarification of what the middle-leading role means. At this stage, most of the respondents also talk about the importance of meta-supervision. During the progressing stage, input in terms of courses and in-depth knowledge is frequently mentioned. Here, the respondents also articulate the need for a different kind of support from the principal; while they wanted more active support and directions in the beginning, they gradually seem to move towards an appreciation of ‘supported autonomy’. Being part of a peer group of middle-leaders, where experiences can be shared, appears as equally important throughout. Towards the end of the project, there are indications in some self-reflections of a need for further challenges and a need to have time to use all new knowledge to develop the middle-leading assignment even more:

I have gained so much knowledge through courses, and really taken on this assignment. It scares me a bit that, starting next semester we won’t be offered any more courses. … I want to use my advanced knowledge and to continue to learn and work for school development … get new challenges that sort of match my new knowledge. … I also think it’s important now that time is set aside for us to continue and refine what we have started. (Teacher E)

Concluding discussion

The aim of this longitudinal study has been to create in-depth knowledge about the phenomenon of middle-leadership in school by focusing on identifying (1) driving forces for seeking and maintaining middle-leading positions and (2) opportunities and difficulties in relation to maintaining the middle-leading role. Moreover, we strove to reveal underlying thoughts of career disclosed in the respondents’ expressions. Five different reasons for seeking a middle-leading position in the first place were identified and driving forces for maintaining the position were categorised as either internal reward/non-observable outcomes or external reward/observable outcomes. Furthermore, the results show that different types of difficulties arise in distinct phases and that middle-leaders’ needs for support therefore vary over time. Additionally, the importance of understanding the complexity of teachers’/middle-leaders’ career thinking clearly emerges. In the brief discussion that follows, we further problematise some key points from the results that have implications for practice.

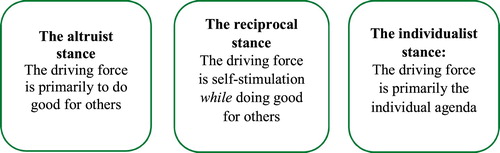

Previous research (Brosky Citation2011; Chamberland Citation2009) suggests that some teachers are so strongly influenced by traditional horizontal structures in the profession that it is hard for them to maintain a middle-leading role. It could be argued that our study, in a sense, confirms that. In our data set, there is a certain correspondence between reasons given for (1) seeking and (2) maintaining the middle-leading position. Based on this it is possible to tentatively discuss a number of ‘middle-leader stances’. We recognise that a typology of stances, in a sense, represent a simplified picture of reality and that it is difficult to provide absolute definitional boundaries between them. Yet, a typology is often pedagogically useful as a conceptual tool for simplifying a myriad of empirical possibilities and for bringing clarity to a field (see Hirsh Citation2015; Holton Citation2003). The typology illustrated in should be understood as a conceptual tool for discussing aspects of the lead teacher phenomenon.

Rather than suggesting that an individual has one stance, in a static way, we assume that one adopts more or less of the different stances and that an individual’s dominant stance may vary over time and according to circumstances. We interpret the fact that 9 out of 10 respondents in our study clearly expressed doubts about seeking a middle-leading position and that several of them initially questioned the reform as such and/or their new professional title as a sign of the respondents being bearers of social/professional representations of teaching as an egalitarian profession. With reference to Moscovici’s (Citation2001) argument about how consensus around representations is challenged in times of change, we argue that we clearly see signs of that in our longitudinal data material. Hitherto prevailing professional representations of the division of labour in a community of teachers, in terms of the horizontal distribution of tasks as well as the vertical distribution of power and status, are challenged and renegotiated when a career reform such as the Swedish lead-teacher reform is introduced.

Teachers A and J consistently articulated an aversion to observable outcomes and very seldom talked about doing good for themselves, wherefore they can be positioned foremost in the altruist stance in the typology. Teachers B, D, E, F, G, H and I, however, increasingly articulated during the period studied that, as teachers and professionals, they need both the aspects categorised under doing for oneself and external reward. Yet, that does not seem to mean that doing for others is less important to them. Instead, they appear to embrace (and increasingly articulate) a reciprocal stance, where the driving force is a non-conflicting combination of an individual agenda (doing for oneself and external reward) and doing good for others. Teacher C is the only respondent that we would position in (or very close to) the individualist stance based on consistent articulations of salary and status as primary driving forces and very few articulations of doing good for others.

Based on our results and the tentative typology above, we suggest that the teachers who manage to successfully maintain their roles as middle-leaders are those expressing a reciprocal stance towards their mission. They seem to embrace their middle-leading assignment with all three of the professional representations, with interplay between them: that is, their assignment is carried out for others, for inner professional satisfaction and for visible professional recognition. Teachers who take on the task of leading colleagues in school-development processes need to embrace the fact that the role entails (partly) different responsibilities than those of their colleagues. At the same time, it is reasonable to argue that leaders of collaborative and collective school development ought to be guided (at least partly) by the professional representation of a mission carried out for others, which the teacher representing the individualistic stance in this study does not express.

Another key point in our results concerns the fact that different types of opportunities and difficulties related to maintaining the middle-leading position arise at distinct phases and that, therefore, middle-leaders’ needs for support vary over time. Research and evaluations of the Swedish lead-teacher reform (see e.g. Alvunger Citation2015; Öhman et al. Citation2016; SNAE Citation2014, Citation2015) carried out at an early stage of the reform’s implementation revealed problems such as great uncertainty about the role and tasks of lead teachers/middle-leaders that can be linked to the very novelty of the reform. For principals and school facilitators, our study contributes with important knowledge, as it shows that aspects such as role definition and clarity, as well as the principal’s expressed support and firm guidance, are important in the initial phase but that another type of support seems to be needed in the progressing and consolidating stages. Towards the end of the studied period, moreover, some respondents expressed anxiety about possible stagnation also in the middle-leading role. This, we argue, is not sufficiently elaborated in current debate on career reforms and the problem of teacher attrition in school, where the focus is on entering a new role rather than on the continuous need for development and the challenge in maintaining it.

Career seems to be regarded foremost as a destination in current school debate, and we argue that it would be better understood as a continuous process of exchange than as a destination. There is a potential danger in understanding career as a destination, given that career reforms aim to attract and retain high-quality teachers to/in the profession. The risk that skilled teachers leave the profession remains if career is not understood as a process of continuous knowledge building and increasing complexity of challenges. The understanding of career as a continuous process of exchange captures the aspects of the professional representations revealed in this study – something that the dominant metaphor of career as climbing the ladder fails to do.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. In this study we refer to our respondents as middle-leaders, in line with the definition by Grootenboer, Edwards Groves and Rönnerman (Citation2015, 509), who describe middle-leaders as ‘those who have an acknowledged position of leadership in their educational institution but also have a significant teaching role’.

2. For a full illustration of the social representations that appear in the study, see Bergmo-Prvulovic (Citation2013).

3. For a full illustration of career guidance professionals’ representations, see Bergmo-Prvulovic (Citation2015).

4. For a full list of the pairs of opposites that appear in the study, see Bergmo-Prvulovic (Citation2013), .

References

- Abric, Jean-Claude. 1995. “Metodologi för datainsamling vid studiet av sociala representationer [Methodology for data collection in the study of social representations].” In Sociala representationer. Om vardagsvetandets sociala fundament, edited by Mohamed Chaib and Birgitta Orfali, 97–120. Göteborg: Daidalos AB.

- Alvunger, Daniel. 2015. “Towards New Forms of Educational Leadership? The Local Implementation of Förstelärare in Swedish Schools.” Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy 2015 (3). doi:10.3402/nstep.v1.30103.

- Arthur, Michael B., and Denise M. Rousseau, eds. 1996. The Boundaryless Career: A New Employment Principle for a New Organizational Era. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Avidov-Ungar, Orit. 2016. “A Model of Professional Development: Teachers’ Perceptions of Their Professional Development.” Teachers and Teaching 22 (6): 653–669. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2016.1158955

- Avidov-Ungar, Orit, and Rinat Arviv-Elyashiv. 2018. “Teacher Perceptions of Empowerment and Promotion During Reforms.” International Journal of Educational Management 32 (1): 155–170.

- Bergmo-Prvulovic, Ingela. 2013. “Social Representations of Career: Anchored in the Past, Conflicting with the Future.” Papers on Social Representations 22 (1): 14.1–14.27.

- Bergmo-Prvulovic, Ingela. 2015. “Social Representations of Career and Career Guidance in the Changing World of Working Life.” PhD dissertation study, Jönköping University, Sweden.

- Bergmo-Prvulovic, Ingela. 2017. “Karriär utifrån ett ansträngnings- och belöningsperspektiv.” [Career from an Effort and Reward Perspective]. In Att Ta Tillvara Mänskliga Resurser: Human Resources; Making Use Of Human Resources, edited by Helene Ahl, Ingela Bergmo-Prvulovic, and Karin Kilhammar, 76–96. Lund: Studentlitteratur AB.

- Bergmo-Prvulovic, Ingela. 2018. “Conflicting Perspectives on Career: Implications for Career Guidance and Social Justice.” In Career Guidance for Social Justice: Contesting Neoliberalism, edited by Tristram Hooley, Ronald Sultana, and Rie Thomsen, 143–158. London: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. chapter 9.

- Borchers, Bruce. 2009. “A Study to Determine the Practices of High School Principals and Central Office Administrators Who Effectively Foster Continuous Professional Learning in High Schools.” PhD dissertation, University of Minnesota. https://conservancy.umn.edu/bitstream/handle/11299/58218/borchers_umn_0130e_10789.pdf?sequence=1.

- Brosky, D. 2011. “Micropolitics in the School: Teacher Leaders’ Use of Political Skill and Influence Tactics.” International Journal of Educational Leadership Preparation 6: 1–11.

- Chamberland, Lori. 2009. “Distributed Leadership: Developing a New Practice; An Action Research Study.” (PhD dissertation, University of California at Santa Cruz. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. https://search.proquest.com/openview/a1627de566358687d8e47ff92d2dcdab/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y.

- Collin, Audrey. 2007. “The Meanings of Career.” In Handbook of Career Studies, edited by Hugh Gunz and Maury Peiperls, 558–565. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Donaldson, Morgaen. 2007. “To Lead or Not to Lead? A Quandary for Newly Tenured Teachers.” In Uncovering Teacher Leadership: Essays and Voices From the Field, edited by Richard Ackerman and Sarah Mackenzie, 259–272. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

- Donaldson, Morgaen, Susan Moore Johnson, Cheryl Kirkpatrick, William Marinell, Jennifer Steele, and Stacy Szczesiul. 2005. “Angling for Access, Bartering for Change: How Second-stage Teachers Experience Differentiated Roles in Schools.” Teachers College Record 110 (5): 1088–1114.

- Edwards Groves, Christine, and Karin Rönnerman. 2013. “Generating Leading Practices Through Professional Learning.” Professional Development in Education 39 (1): 122–140. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2012.724439

- Engeström, Yrjö. 2001. “Expansive Learning at Work: Toward an Activity Theoretical Reconceptualization.” Journal of Education and Work 14 (1): 133–156. doi: 10.1080/13639080020028747

- Ganchorre, Athena, and Debra Tomanek. 2012. “Commitment to Teach in Under-Resourced Schools: Prospective Science and Mathematics Teachers’ Dispositions.” Journal of Science Teacher Education 23: 87–110. doi: 10.1007/s10972-011-9263-y

- Graneheim Hällgren, Ulla, and Britt-Marie Lundman. 2004. “Qualitative Content Analysis in Nursing Research: Concepts, Procedures and Measures to Achieve Trustworthiness.” Nurse Education Today 24 (2): 105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001

- Grootenboer, Peter, Christine Edwards-Groves, and Karin Rönnerman. 2015. “Leading Practice Development: Voices From the Middle.” Professional Development in Education 41 (3): 508–526. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2014.924985

- Hall, Douglas. 1996. “Protean Careers of the 21st Century.” Academy of Management Executive 10 (4): 8–16.

- Harris, Alma, and Michelle Jones. 2017. “Middle Leaders Matter: Reflections, Recognition, and Renaissance.” School Leadership & Management 37 (3): 213–216. doi:10.1080/13632434.2017.1323398.

- Hirsh, Åsa. 2013. “The Individual Development Plan as Tool and Practice in Swedish Compulsory School.” PhD dissertation study, Jönköping University, Sweden.

- Hirsh, Åsa. 2015. “IDPs at Work.” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 59 (1): 77–94. doi: 10.1080/00313831.2013.840676

- Hirsh, Åsa, and Mikael Segolsson. 2017. “Enabling Teacher-driven School-development and Collaborative Learning: An Activity Theory-based Study of Leadership as an Overarching Practice.” Educational Management, Administration & Leadership, 1–21. doi:10.1177/1741143217739363.

- Hjalmarsson, Maria, and Annica Löfdahl Hultman. 2016. “Det är inte jag som hartillsatt mig själv på posten: Motstånd och ironi i relationer mellan förstelärare och deras kollegor.” [I Did Not Put Myself in This Position: Resistance and Irony in Relations between Lead Teachers and Their Colleagues]. Kapet 12 (1): 76–94.

- Holton, Robert. 2003. “Max Weber and the Interpretative Tradition.” In Handbook of Historical Sociology, edited by Gerard Delanty and Engin F. Isin, 27–39. London: Sage Publications.

- Kidd, Jenny. 2006. Understanding Career Counselling: Theory, Research and Practice. London: SAGE Publications.

- Kyriacou, Chris, and Melissa Coulthard. 2000. “Undergraduates’ Views of Teaching as a Career Choice.” Journal of Education for Teaching 26 (2): 117–126. doi: 10.1080/02607470050127036

- Margolis, Jason, and Anne Doring. 2012. “The Fundamental Dilemma of Teacher Leader-Facilitated Professional Development: Do as I (Kind Of) Say, Not as I (Sort Of) Do.” Educational Administration Quarterly 48: 859–882. doi: 10.1177/0013161X12452563

- Moran, Anne, Rosemary Kilpatrick, Lesley Abbot, John Dallat, and Billy McClune. 2001. “Training to Teach: Motivating Factors and Implications for Recruitment.” Evaluation & Research in Education 15 (1): 17–32. doi: 10.1080/09500790108666980

- Moreau, Marie-Pierre. 2014. “Becoming a Secondary School Teacher in England and France: Contextualising Career ‘Choice’.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 45 (3): 401–421. doi: 10.1080/03057925.2013.876310

- Moscovici, Serge. 1973. Foreword to Health and Illness: A Social Psychological Analysis, edited by Claudine Herzlich. London: Academic Press in cooperation with the European Association of Experimental Social Psychology.

- Moscovici, S. 2001. Social Representations: Explorations in Social Psychology. New York: New York University Press.

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). 2005. “Teachers Matter: Attracting, Developing and Retaining Effective Teachers.” Report. http://www.oecd.org/education/school/34990905.pdf.

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). 2015. “Improving Schools in Sweden: An OECD Perspective.” Report. http://www.oecd.org/education/school/Improving-Schools-in-Sweden.pdf.

- Öhman, Anne, Christina Ehneström, Per-Erik Ellström, and Lennart Svensson. 2016. Karriärtjänster för lärare – möjlighet eller hinder för skolutveckling? [Career Paths for Teachers: Possibility or Obstacle for School Development?]. Report from the University of Linköping. https://www.skolverket.se/polopoly_fs/1.258001!/Link%C3%B6pings%20universitet%20och%20Stockholms%20stad.pdf.

- Ratinaud, Pierre, and Michel Lac. 2011. “Understanding Professionalization as a Representational Process.” In Education, Professionalization and Social Representations: On the Transformation of Social Knowledge, edited by Mohamed Chaib, Berth Danermark, and Staffan Selander, 55–67. London: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Savickas, Mark L. 2008. “Helping People Choose Jobs: A History of the Guidance Profession.” In International Handbook of Career Guidance, edited by James A. Athanasou and Raoul Van Esbroeck, 97–113. Dordrecht: Springer Science Business Media.

- SNAE (Swedish National Agency for Education). 2014. Vem är försteläraren? [Who Is the Lead Teacher?]. Stockholm: SNAE.

- SNAE (Swedish National Agency for Education). 2015. Vad gör försteläraren? [What Does the Lead Teacher Do?]. Stockholm: SNAE.

- SNAE (Swedish National Agency for Education). 2017. “Uppföljning av Karriärtjänster bidragsåret 2017” [Following Up on Career Assignments for the Grant Year 2017]. Report 2017:0035. Stockholm: SNAE.

- Swedish Ministry of Education. 2012. “Karriärvägar m.m. i fråga om lärare i skolväsendet” [Career Paths etc. for School Teachers]. Promemoria U2012/4904/S. http://www.regeringen.se/49b726/contentassets/b0c754e5bd4e406d97c167167de6feaa/karriarvagar-m.m.-i-fraga-om-larare-i-skolvasendet.

- Swedish Ministry of Education. 2017. “Samling för skolan – Nationell strategi för kunskap och likvärdighet” [Call for a National Strategy for Knowledge and Equity in School]. Public report SOU 2017:35. http://www.regeringen.se/rattsdokument/statens-offentliga-utredningar/2017/04/sou-201735/.

- Wenner, Julianne, and Todd Campbell. 2017. “The Theoretical and Empirical Basis of Teacher Leadership: A Review of the Literature.” Review of Educational Research 81 (1): 134–171. doi: 10.3102/0034654316653478

- York-Barr, Jennifer, and Karen Duke. 2004. “What Do We Know About Teacher Leadership? Findings From Two Decades of Scholarship.” Review of Educational Research 74 (3): 255–316. doi: 10.3102/00346543074003255