ABSTRACT

This article analyses the ways in which leaders in Multi-Academy Trusts (MATs) in England work to develop shared improvement practices across the schools they operate. It draws on case study evidence gathered as part of a larger mixed methods study (Greany [2018]. Sustainable Improvement in Multi-school Groups. DfE Research report 2017/038. London: Department for Education). There are now more than 1200 MATs in England, operating anywhere between two and 50+ academies within a single organisational structure. A key question facing MAT leaders is whether, where and how far to seek integration between member schools, especially given the argument that such integration can ensure that teaching and learning practices are being consistently applied. The research reveals varying levels of standardisation, alignment and autonomy across different aspects of practice (assessment, curriculum and pedagogy). While some MAT leaders seek to standardise and regulate most areas of practice, others emphasise more organic or co-designed approaches to building shared norms and/or allow space for local contextualisation. Drawing on research into ‘Mergers and Acquisitions’ and Post-Merger Integration’ in organisational studies, we analyse the theories of action which underpin these leaders’ approaches and set out a typology aimed at strengthening understanding of MAT approaches to improvement.

Introduction

This article analyses the ways in which leaders in Multi-Academy Trusts (MATs) in England work to develop shared improvement practices across the schools they operate. It draws on case study evidence gathered as part of a larger mixed methods study by the authors (Greany Citation2018; Greany and McGinity Citationforthcoming).

A MAT is a charitable non-profit company with a board and Chief Executive Officer (CEO), which operates a number of academies via a funding agreement with the Secretary of State for Education (West and Wolfe Citation2018). By June 2020 there were around 1200 MATsFootnote1 operating around 7600 academies (i.e. more than a third of all schools, and educating about half of all pupils in England). The MAT board and CEO are responsible for all aspects of the operation and performance of member schools, so there is intense pressure on these leaders to demonstrate improvement in school quality, as measured in national tests, exams and Ofsted inspection outcomes (Ehren and Godfrey Citation2017). Since their initial development before 2010, the growth of MATs has been rapid and sometimes chaotic, representing a fundamental shift in the organisation, structure and operation of England’s school system (Greany and Higham Citation2018; Courtney and McGinity Citation2020; Thomson Citation2020). England’s 152 Local Authorities (LAs), which previously had responsibility for overseeing almost all state-funded schools, have been largely hollowed out, while the emergence of MATs and academies has created a more fragmented and less clearly place-based middle tier, with a stronger role for central government in educational delivery (Crawford et al. Citation2020; Greany Citation2020).

Various studies have sought to assess the performance of MATs, including in comparison with other schools nationally (Andrews, Citation2018; Andrews and Perera Citation2017; Hutchings and Francis Citation2017; Bernardinelli et al. Citation2018). These analyses show that there are wide variations in performance within the MAT sector, and that the sector as a whole is performing at or slightly below the national average.

Greany and Higham (Citation2018) argue that the growth of MATs has come about predominantly through a process of ‘mergers and acquisitions’ between existing state-funded schools, with only a minority of MAT-run academies opened as new (‘free’) schools. Clearly, there are distinctions between ‘mergers’ and ‘acquisitions’: while a merger can – in theory – be a partnership of equals, an acquisition is by definition a take-over. This distinction has parallels in the MAT sector, because a school can join a MAT in two different ways: higher performing schools can choose to convert to become an academy and can also choose whether to form or join a MAT,Footnote2 whereas schools that are judged to be ‘Inadequate’ by Ofsted will usually be forced (by the Secretary of State) to become a sponsored academy within a MAT. These differences inevitably affect how the school perceives its relationship to the MAT and vice versa – i.e. whether it feels closer to a merger or an acquisition. However, in both cases the academy is subsumed into the MAT and ceases to exist as a separate legal entity.

The issue of how to manage growth and how to integrate any new schools into the existing group’s culture and ways of working is a perennial challenge for MAT leaders (Hill et al. Citation2012; Ofsted Citation2019; Simon, James, and Simon Citation2019). These issues are compounded by the intense accountability pressures on MAT and school leaders, which require them to demonstrate rapid improvements in pupil outcomes and school Ofsted grades. These pressures are particularly acute in the case of sponsored academies, which tend to operate in deprived contexts and to perform less well on national benchmarks. Nevertheless, the Government has encouraged MATs to grow, based on an argument that this will increase their capacity, efficiency and effectiveness, with one minister claiming the ‘sweet-spot’ is 12–20 schools (Agnew Citation2017).Footnote3 Despite this encouragement, most MATs remain relatively small: for example, in June 2020, more than 80% of MATs had fewer than 10 schools and only 49 had more than 20 schools.

Whatever the size of the MAT, a key question is whether, where and how far to seek integration between member schools. Most MATs do appear to integrate some or all of their ‘back-office’ functions, such as finance, procurement and Human Resources, based on a view that this will increase efficiency and effectiveness through economies of scale (Davies, Diamond, and Perry Citation2019; Ofsted Citation2019). The focus here though is on MAT approaches to the integration of core school improvement related areas, particularly pedagogy, curriculum and assessment. Integration in these areas requires significant change for classroom teachers and school leaders, and can be fraught with difficulty when schools with very different cultures are forced to integrate and demonstrate rapid impact (Birks Citation2019).

As yet, other than the study reported here, relatively few researchers have explored these issues in depth. Ofsted’s (Citation2019) review of 41 MATs found wide variations in how MATs operate, from some that are highly centralised to others that are highly devolved. The report concludes that the level of centralisation relates to size, because ‘growth requires a measure of standardisation across a MAT, as well as the centralisation of a range of services and functions’ (Ofsted Citation2019, 13). Menzies et al. (Citation2018) assessed the ways in which MAT leaders develop their organisations as they grow, but found no clear links between specific strategies and levels of performance. The authors argue that MAT leaders should choose between preserving the autonomy of individual schools or achieving consistent teaching and pedagogy across the trust, with consistency achieved through either central direction or a process of ‘collaborative convergence’ (Menzies et al. Citation2018, 2). Menzies et al. also identify a series of ‘break points’, in terms of growth and size, at which they argue that MATs must reshape their approach, for example in terms of the scope and focus of the CEO role, the model of governance and the structure of the core team.

Despite the limited evidence in support of specific approaches to MAT improvement, the government has encouraged MATs to standardise practices across member schools. For example, the Department for Education’s (DfE) ‘good practice’ guidance for MATs (Citation2016, 30) states that ‘effective MATs have taken the opportunity to standardise effective teaching approaches … (which) has proven to be effective in improving pupil outcomes … (and) can also help reduce unnecessary work for teachers’.

Given these developments, our interest is in how MAT leaders conceptualise and approach the process of integrating new schools in terms of school improvement and teaching practices. Our particular focus is on why and how MAT leaders choose to try and standardise or align improvement related practices across member schools, or whether they grant schools autonomy to pursue distinctive approaches. We argue that such decision making reflects a theory of action for knowledge sharing and practice improvement across these MATs, even though these theories may not always be fully articulated or explicit.

The article is structured as follows. First we summarise key concepts and evidence from the Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A) and Post-Merger Integration (PMI) literatures in two areas – structural integration and knowledge transfer. Next we provide a brief summary of the methodology adopted by the main study (Greany Citation2018). We then set out the main findings in two sections: the first provides an overview of MAT approaches to school improvement, while the second focuses on structural integration and knowledge transfer, in particular through the use of standardisation, alignment and autonomy approaches. We conclude by discussing the implications, setting out a framework for categorising MATs and a typology of different approaches to improvement. Finally, we identify the significance and limitations of the article.

Lessons from the literature

This section is in three parts. The first provides a brief overview of the M&A and PMI literature and explains how this has been drawn on to inform thinking about the integration of new schools into a MAT, including the limitations of doing so. The second focusses on structural integration and the question of how far systems, processes and practices should be standardised or aligned, or left autonomous. It highlights the tendency for acquiring firms to impose systems and processes on the acquired firm, despite evidence that successful integration requires a more sophisticated and multi-stage process. The third part considers knowledge exchange, where various studies have shown that this inherently inter-personal process requires attention to issues of culture and trust as well as the ways in which knowledge is codified, exchanged and applied. These later sections emphasise the importance of leadership, in both the acquiring and acquired organisation, for facilitating mutual exchange and culture-building.

Overview

M&As are common in most sectors, including many parts of the public and voluntary sectors, although the bulk of research in this area has focused on the private sector. M&As are driven by diverse aims, from a need to achieve efficiency or economies of scale, through to entering new markets, eliminating competitors, and acquiring new technologies or forms of expertise. However, research over several decades shows that many M&As do not achieve their original aims (Caves Citation1989; Hawkins Citation2005): indeed, Martin (Citation2016, 1) states that ‘typically 70%–90% of acquisitions are abysmal failures’.

PMI involves the study of ‘the multifaceted, dynamic process through which the acquirer and acquired firm or their components are combined to form a new organization’ (Graebner et al. Citation2017, 1). Bodner and Capron (Citation2018, 2) highlight the range of issues involved in any merger, perhaps explaining why so many fail:

The PMI process typically comes up against obstacles related to capturing synergy, client disruption, structural integration, employee retention, loss of identity and/or independence, customer retention, emotional trauma, loss of status, and learning challenges.

Structural integration

A key issue which has pre-occupied PMI research and practice is whether and how to pursue structural integration between the acquirer and the acquired organisation. Structural integration and reconfiguration can take place in different ways and to differing extents across different parts of the merging organisations, but any level of integration will raise questions around how far systems, processes and practices should be standardised or aligned, or left autonomous – an issue that Bodner and Capron (Citation2018, 5) call the ‘coordination-autonomy dilemma’. The evidence does suggest that standardisation and alignment can enhance efficiency and effectiveness and can also support improved communication and knowledge flows across the newly combined organisation (Sarala and Vaara Citation2010). However, these benefits are far from automatic and it is clear that the process of securing standardisation or alignment can be challenging and can lead to unintended outcomes which might outweigh any benefits.

Haspeslagh and Jemison’s (Citation1991) ‘integration matrix’ differentiates two issues: how far the acquired and acquiring firm require strategic interdependence, and how far the acquired firm needs organisational autonomy. This gives four options, which Graebner et al. (Citation2017 , 5) describe as follows:

The “holding” approach involves virtually no operational changes, with the target firm remaining essentially independent. The “absorption” approach involves complete consolidation, resulting in dissolution of the boundary between acquirer and target … “Preservation” involves selective engagement in areas in which there are interdependencies or opportunities for learning, while the acquirer manages the target’s other functions at arm’s length. Finally, a “symbiotic” approach involves a gradual progression from autonomy to full “amalgamation,” in which the two organizations create a “new, unique identity”. (Haspeslagh and Jemison Citation1991, 231)

The ‘sense of superiority’ common among acquiring firms is symptomatic of a wider problem according to Martin (Citation2016, 1), who argues that ‘companies that focus on what they are going to get from an acquisition are less likely to succeed than those that focus on what they have to give it’. According to Martin, companies in ‘take’ mode are focused on what they can gain from the deal rather than the value they can add, but these companies often find they are unable to secure the expected benefits, such as reduced operating costs. By contrast, companies in ‘give’ mode are more focused on how they can improve and grow the acquired business, and therefore the partnership as a whole. Martin concludes that these acquirers ‘give’ by being better providers of capital, providing valuable managerial oversight, transferring skills or sharing valuable capabilities. His key point is thus that the merger must be seen – as far as possible – as a partnership of equals, rather than a takeover. Or, as Bodner and Capron (Citation2018, 17) conclude:

Merging firms, both acquirer and target, need to find internal alignment on the motivation behind an acquisition, such as leveraging knowledge or capabilities, and choose the level of integration accordingly, before defining the degree of structural integration.

Knowledge transfer

Analyses of knowledge transfer in PMI focus on socio-cultural as well as structural integration issues. Sarala et al. (Citation2016, 1235) define knowledge transfer as ‘the successful transmission of knowledge, including the sending or presenting of knowledge to a potential recipient and the absorption of knowledge by the recipient’. Empson (Citation2001, 843) notes that ‘knowledge transfer is above all an inter-personal process … Individuals cannot be compelled to share knowledge with others, but can only do so willingly’.

Part of the challenge is that so much professional knowledge is tacit and socially embedded, making it hard to transfer even within a single organisation, let alone between two recently merged organisations where shared norms and levels of inter-personal as well as inter-organisational trust are likely to be lower. Empson’s (Citation2001, 843) longitudinal research focussed on knowledge transfer in six professional services companies engaged in M&As, finding that ‘individuals will resist knowledge transfer when they perceive fundamental differences in the form of the knowledge base and the organizational image of the combining firms’ (Empson Citation2001, 857). The firms she studied differed in the extent to which they relied on formally codified or more tacit forms of knowledge, with each type of knowledge being seen to have pitfalls as well as benefits. While codified knowledge might be seen as ostensibly easier to exchange, the process of codifying it was seen by some employees to have reduced its value, making it overly simplistic or low level in their view. Equally, tacit knowledge, for example about the needs and preferences of a particular customer, was often seen to be valuable, making individuals reluctant to share if they thought that doing so might reduce their status. Empson (Citation2001, 857) concluded that two ‘fears’ – of exploitation and contamination – shape propensity to share knowledge, and that these are driven by ‘a complex combination of factors which encompass both organizational and individual, commercial and personal, and objective and subjective factors’.

In practice, similarly to structural integration, the tendency is for acquiring firms to impose their existing knowledge onto the acquired firm ‘regardless of its applicability’ (Graebner et al, Citation2017, 10). Such approaches appear to reflect Bodner and Capron’s (Citation2018, 7) observation that senior managers responsible for overseeing PMI processes often limit their potential due to their ‘bounded rationality, reflected in a tendency for local search, excessive use of previous templates, overreliance on routines, and limited appreciation of the M&A uniqueness’. However, such leadership approaches are not universal. Graebner’s (Citation2004) research in knowledge based technology firms found that leaders within the acquired firm can play a central role in successful PMI by ‘address(ing) employees’ emergent concerns … maintain(ing) productive momentum … and using their familiarity with their own firms’ knowledge and technologies to identify opportunities for resource redeployment and reconfiguration across the merging firms’ (ibid, 9). Of course, ‘acquired leaders were only able to perform this function if they were given cross-organizational responsibilities in the combined firm’ and if ‘the target’s knowledge is preserved rather than replaced’ (ibid, 9).

Sarala et al. (Citation2016) conclude that successful knowledge transfer in PMI contexts requires the strengthening of inter-firm linkages, including through effective and adaptive HR and governance approaches and the fostering of knowledge-sharing routines. Trust, which is reflected in the ‘willingness of employees to be vulnerable to the partner firm because they expect the partner firm to have positive intentions’ (Saraala et al. 2016, 1235), is an important precursor for knowledge-sharing and for overcoming the fear of exploitation and contamination. In addition, and in line with the finding from Birkinshaw et al. outlined above, a process of cultural integration is required to support alignment of ‘the assumptions, values, and norms of the merging firms through convergence (the firms become more similar along existing cultural dimensions) or through crossvergence (new cultural dimensions are created)’ (Birkinshaw et al. Citation2000, 1236).

Methods

The research involved twenty-three detailed MAT case studies, which form the core of the analysis in this article.Footnote4 These cases were purposively sampled to reflect a range of performance profiles (13 × ‘above average’, 5 × ‘average’ and 5 × ‘below average’ performers)Footnote5 and size bands (6 × small i.e. 3–6 schools; 9 × medium i.e. 7–14 schools; and 8 × large i.e. 15+ schools). In addition, we sought to achieve a balance in terms of trusts with different characteristics and working with schools in different phases, socio-economic circumstances and geographic areas.

Each case study visit lasted two days, visiting the MAT central office and two or three schools in most cases. In total, 231 semi-structured interviews were undertaken with a range of central and school-based MAT leaders, including the CEO, members of the central school improvement team, executive heads, school principals, deputy principals and middle leaders. Each case study was written up using a standard template and was then coded separately by two members of the research team using a combination of top-down and bottom-up codes. Cross-case analysis was undertaken separately by three members of the team to identify common themes, with emerging codes and themes agreed through an iterative process. These emerging findings were tested and refined through a workshop involving the full case study research team and a focus group with leaders from the case study sites.

The research also included a national online survey of MAT leaders (i.e. CEOs and other central team staff, n = 209) and MAT headteachers (n = 150), which informs the analysis here but is not drawn on specifically.

Ethical approval was secured from the UCL Institute of Education’s Research Ethics Committee.

School improvement in MATs

The research explored approaches to school improvement in MATs. It did not specifically focus on the integration of new schools into existing MATs, however all the case-study MATs had incorporated new schools in recent years and so the question of how to secure improvement in both existing and newly joined schools was a central theme of the research.

There was a diversity of contexts, approaches and outcomes across the sample. Approaches to the integration of school improvement ranged from highly centralised at one extreme, to largely de-centralised at the other. Even within some of the more centralised MATs, practices were rarely homogenous: for example, one medium-sized trust claimed to have developed a shared language for learning and common pedagogical approach across all its schools, but interviews within individual schools revealed mixed levels of take up and a degree of surface implementation.

A number of factors appear to influence how MATs conceptualise and operationalise their approach to integration and improvement, including: when and how the MAT was established; its size and rate of growth; the context and composition of its schools (including the mix of primary/secondary phases and performance on national accountability metrics); and the beliefs and values of its founding leader(s). The breadth of these factors helps to explain why MAT approaches are so diverse, although the findings do support some broad generalisations. These include that: MATs tend to be more prescriptive with sponsored academies and in ‘turnaround’ situations, while MATs made up of mainly converter academies tend to be more decentralised.

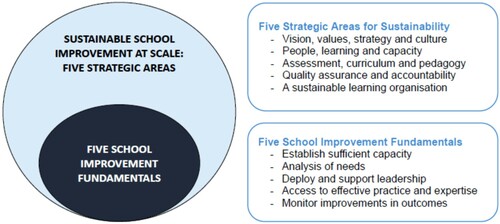

There were broad common areas of focus across all MATs in the sample. These are represented in the five ‘fundamentals’ and five ‘strategic areas’ shown in . The ‘fundamentals’ were identifiable in all the trusts visited, but were most apparent in MATs undertaking ‘turnaround’ work with newly sponsored and under-performing schools.

In practice, action on the five strategic areas was dynamic and inter-connected. For example, MAT leaders recognised that investing in ‘people, learning and capacity’ through MAT-wide professional development programmes was also a way of building staff commitment to a shared ‘vision, values, strategy and culture’. That said, relatively few MAT leaders could articulate a clear theory of action for how they were working to develop a coherent MAT improvement model for all schools. Rather, the focus tended to be on how to identify and address under-performance in specific schools. One notable exception was a CEO who explained how the MAT’s approach to improvement had evolved over time and as the trust grew. This had developed in three phases: in the first phase, when the trust included just three schools, support came from the founding school (‘the mothership’); as more schools joined this proved unviable, so the MAT adopted a ‘leadership+ model’, based on deploying excellent leadership into new schools, with some initial additional support from the Deputy CEO; phase 3 developed once the trust had nine schools and realised that it faced a shortage of excellent headteachers and that relying on these ‘heroic’ individuals was unsustainable, to it had started to build the capacity of its central team and to apply more standardised curriculum and pedagogical tools and approaches across all its schools.

Space does not permit a detailed exploration of all the related findings,Footnote6 but we highlight two aspects which have a bearing on how MATs approach the integration of new schools and how far they seek to standardise practices.

The first is ‘vision and values’, where we observed two broad approaches. One group of MATs had a relatively narrow, performance driven focus; for example, using Ofsted language to reflect their core mission (e.g. ‘Good or better every day’). The second group also focused on performance, but reflected a wider purpose as well: for some this was a faith-based ethos; others were committed to maintaining a comprehensive intake and inclusive approach; others adhered to a particular pedagogical or curriculum-related philosophy.

The second relates to the decision-making approach of the MAT CEO, where three distinct approaches were apparent. The first was directive; for example, one CEO in a small MAT explained ‘If you want to be in our trust, we’re the design authority’. The second was paternalistic; for example, leaders in several MATs referred to their schools as a ‘family’, with themselves clearly positioned as the head who set the culture and made decisions in the schools’ best interests. The third was more transparent; in these MATs, leaders would involve headteachers and other staff in decision-making, leading to defined and collectively owned principles, for example around how limited resources might be prioritised and allocated among schools.

Structural integration and knowledge exchange in MATs

MAT leaders were wrestling with many of the issues outlined above from the M&A/PMI literature, specifically in relation to the integration of schools and how best to ensure that professional knowledge and practices were shared and applied across the group.

Taking on new (particularly underperforming) schools was frequently described as part of the MAT’s ‘moral purpose’, although it was clear that MAT leaders also saw wider benefits, such as development opportunities for existing staff, additional income, and/or prestige (Simon, James, and Simon Citation2019). However, growth also carried risks, for example if the MAT did not have the capacity to support a new school, or if the costs involved in doing so would be prohibitive. Most of the below average performing MATs in the sample had clearly taken on too many challenging schools in the past, with too little attention paid to how they would integrate and support them. Over time, most MATs had developed more sophisticated approaches to ‘due diligence’, with staff spending time in any potential new school to assess its capacity, culture and improvement needs – ‘we pore over everything’ (MAT CEO).

In terms of structural integration, two of the case-study MATs had relatively flat structures, with the CEO facilitating shared decision-making among member-school principals. These two trusts were comprised of high-performing, converter academies, each of which retained significant autonomy and with few shared systems and processes across the trust. The remaining trusts operated more hierarchically, albeit to differing degrees: in these MATs the board and CEO retained central control, with a Scheme of Delegation identifying which decisions could be made at a local level. The most extreme example of hierarchical control was a CEO who had taken over a large, below average performing MAT. He explained that his ‘biggest and most important change’ had been to the Scheme of Delegation ‘to make clear that the CEO has overall accountability and responsibility’.Footnote7 He had also enforced what he called an ‘80/20 model’ across all the MAT’s schools – meaning that 80% of practices were standardised, while 20% could be adapted locally. In practice this meant that all ten secondary schools taught the same curriculum, to the same timetable, with a standardised lesson structure and a common assessment and reporting system. Examples given of local adaptation – i.e. the 20% – were limited to specific areas, such as how to introduce a lesson.

In order to assess how improvement work was structured in the case-study MATs, the research adopted the following definitions:

Earned autonomy – ‘Individual schools are largely autonomous and can decide their own approach, except where performance is poor’

School-to-school – ‘Most of the school improvement activity in our MAT draws on school-to-school support – the central team is small and plays a facilitating role’

Centralised – ‘The central team is the driving force for school improvement in our MAT and is where most of the capacity sits’.

Among the medium and larger-sized MATs in the sample there was a convergence of practice in most cases, with a core reliance on centrally employed staff, sometimes augmented through the use of centrally brokered school-to-school support and (at least for higher performing schools) some level of earned autonomy. In a large MAT, this might mean that a principal would have an Executive Head or Regional Director as their line-manager – with a remit to both challenge and support them (usually alongside an academy-level governing council). In addition, a group of subject and other specialists would be employed centrally and deployed (by the CEO or Executive Head) to support any schools that required additional capacity, for example because the school’s test results were poor or to prepare for an expected Ofsted inspection. In some cases, this central team capacity might be augmented by staff or leaders drawn from other, higher-performing schools in the group. Higher performing schools might be given more freedom to operate (i.e. earned autonomy), while lower performing schools would generally be subject to greater scrutiny and intervention.

The question of whether, where and how to standardise or align practices across a MAT was significant and often contentious. Most MAT leaders were concerned that imposed standardisation could reduce professional ownership and limit the scope for adaptation to the needs of different schools and contexts. However they also saw benefits in aligning or standardising practices, for example to provide comparable data on performance and so that effective practices could be shared and applied consistently.

The research focussed on the following definitions:

Autonomous practice – ‘each individual school being able to decide its own approach’

Aligned practice – ‘an agreed approach that is widely adopted, but on a voluntary basis’

Standardised practice – ‘a single required approach that all schools must adopt’

The vast majority of case-study MATs had either standardised or aligned practices in relation to pupil assessment and data reporting. In contrast, the majority of MATs – particularly the medium and large above average performing ones – were not adopting standardised approaches to the curriculum or pedagogical practices. A categorisation of the case study MATs in these two areas is included in Annex A. This shows that just three of the MATs had standardised most aspects of curriculum and pedagogy (including the ‘80/20’ MAT described above) while one additional MAT had standardised its curriculum, but the remainder (n = 19) remain either autonomous or aligned. The categorisation includes the MAT size and performance band, but suggests no clear patterns: for example, above average performing MATs appear in the autonomous, aligned and standardised boxes.

The process of aligning or standardising practices was challenging for leaders, particularly in MATs where the pre-existing culture was predicated on high-levels of school autonomy. A minority of leaders adopted a ‘bullish’ approach in driving through changes, whereas the majority worked in ways to achieve consensus. For example, one Regional Director at a large, above average performing MAT explained:

We celebrate the uniqueness of the schools, it isn’t a blanket “we’ll all do this” … In order for each school to thrive, it has to be owned by their own staff … we hold on to that, where is the balance between standardisation and autonomy, how much of this do we need to be adopted, how much can be adapted and how much are we going to allow the schools to fly in their own right?

The various strategies described in this section were applied in hybrid and often evolving ways in each MAT. However, certain combinations were common. For example, the MATs that were focussed on securing high-levels of standardisation in all areas tended to have a relatively narrow, performance-driven focus, a directive decision-making approach, a centralised structure and a roll-out approach to replicating practice. By contrast, the MATs that were seeking to develop alignment across schools tended to adopt more a consensual and transparent approach to decision-making and to rely on co-design or organic approaches to replicating practices. We develop our assessment of these combinations further in the following section, where we set out a typology of four MAT approaches to improvement.

Discussion

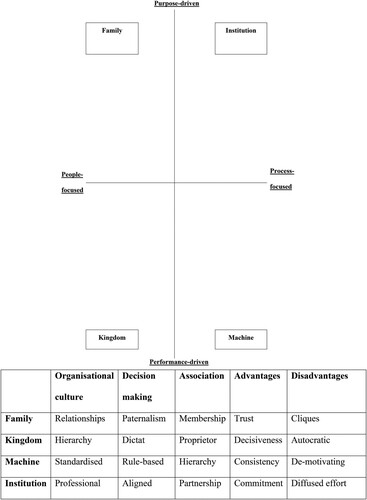

Direct comparisons between the M&A/PMI literature and MATs would be inappropriate, due to the distinctive context of publicly funded and regulated schooling. Furthermore, our study did not encompass the ‘back-office’ aspects of MAT operations and was not specifically focused on the integration of new schools, so we are not able to make comprehensive assessments of their structural integration. Nevertheless, as we outline below, the M&A/PMI literature can help to illuminate some of the strengths and weaknesses of MAT approaches to growth and knowledge exchange. We conclude by setting out a framework for categorising MAT approaches to improvement based on four dimensions – purpose, performance, process and people. This categorisation supports a typology of four distinctive approaches – family, kingdom, machine and institution – which we sketch out briefly.

Our findings indicate that MAT approaches to integration and knowledge transfer do reflect common assumptions and practices observed in other sectors. Thus, just as Mirvis and Marks (Citation1992, 97) identify a ‘sense of superiority’ in acquiring firms and Graebner (2017, 10) finds that acquirers tend to impose their existing knowledge onto new firms ‘regardless of its applicability’, so we see that MATs frequently require new schools to adopt existing models in relation to assessment, curriculum and pedagogy. This is particularly the case for sponsored academies, which are often assumed to be deficient in all areas. Yet in their study, Simon, James, and Simon (Citation2019, 7) found that for most sponsored academies ‘the difficulties they face reside in financial management rather than the core business of teaching and learning’, indicating that any assumption of a need to impose existing practices could be misguided. The MATs that had adopted standardised approaches to curriculum and pedagogy (see Annex A) were the most likely to impose their approach onto newly joined schools, but even in trusts that were less standardised overall it was still common to impose practices on these schools, albeit in a slightly more nuanced way. For example, the Primary Director in one large, above average performing MAT explained: ‘where a school is failing we will put in the curriculum, but we adopt different approaches to fit the school, we don’t do Stepford Wives’.

As we note above, MATs have become more focussed on and sophisticated in under-taking ‘due diligence’ exercises, through which they assess the needs of prospective new schools before taking them on. While these assessments might, potentially, identify strengths as well as weaknesses in these schools, we found no evidence that MATs were open to learning from the sponsored academies they took on, which were invariably described by MAT staff as ‘failing’ or ‘inadequate’. Thus it seems more likely that the MAT due diligence processes are closer to the PMI behaviours identified by Bodner and Capron (Citation2018, 7) – i.e. ‘bounded rationality, reflected in a tendency for local search, excessive use of previous templates, overreliance on routines, and limited appreciation of the M&A uniqueness’.

Turning to the issue of knowledge transfer, Graebner (Citation2004) found that leaders within the acquired organisation can play a central role in successful PMI and knowledge transfer, but only if they are given cross-organisational responsibilities. As we describe in detail in the main report (Greany Citation2018), the research found that most MATs were focused on developing and retaining staff and on identifying and developing leadership potential, often with sophisticated systems and processes for doing this. However, in the case of newly sponsored academies we heard that staff turnover was high, with more than 50% of existing staff often leaving within the first year after sponsorship. As we highlight in the ‘five fundamentals’ above, MATs tend to place their own leaders into newly sponsored schools. This finding is supported by Worth’s (Citation2017) statistical analysis of staff recruitment, retention and turn-over in MATs, which shows that MATs have higher levels of both recruitment and turnover than non-MAT schools and also higher levels of staff movements between schools, particularly at leadership level. This indicates that in the case of sponsored academies the opportunities for mutual knowledge transfer, with leaders in the acquired school being given cross-organisational responsibilities to support this, are extremely limited.

Turning to knowledge transfer between existing schools within MATs, the picture is more positive. The emphasis on aligning practices and investing in staff collaboration and development in many MATs suggests that these trusts recognise, intuitively, the findings relating to successful knowledge transfer outlined above: for example, that it is an inter-personal process which requires trust and the adoption of shared routines. An interesting question here is how far this knowledge transfer benefits from being codified (for example, into formal curriculum schemes or professional development programmes) or whether it might usefully remain tacit, allowing it to be shared informally between staff in collaborative cultures. The standardised and co-design models described above emphasise a codified approach, while the organic model could be seen to support more tacit forms of knowledge transfer. Assessing the applicability and impact of these different approaches is beyond the scope of this paper, but appears worthy of further study.

Successful knowledge transfer between schools in MATs is influenced by the wider structural and socio-cultural integration issues outlined above, and what Bodner and Capron (Citation2018, 5) call the ‘coordination-autonomy dilemma’. As we have shown, the MATs in the study have adopted different approaches, from highly centralised to largely distributed. We have also indicated the distinctive nature of the MAT sector, with differences between converter and sponsored academies and the pressures exerted by the national regulatory framework (i.e. to demonstrate rapid improvement, to grow and to standardise practices etc).

In order to illustrate the main areas that the MATs in our study were focused on and that differentiated their approach to these areas, we have developed the framework shown in , below.

The framework reflects a grounded attempt to theorise the issues and approaches we observed, but it is also informed by the wider M&A/PMI literature and Morgan’s (Citation2006) synthesis of the organisational literature, as we explain below. The framework includes four dimensions – purpose-driven, performance-driven, people-driven and process-driven. These dimensions reflect what we see as the main areas that MAT leaders focus on as they seek to develop and integrate their new organisations. Importantly, the four dimensions are not mutually exclusive. So, for example, we identified MATs with a strong faith ethos or commitment to a set of values (e.g. inclusion) that under-pinned their ‘purpose’, but these MATs invariably had a parallel focus on ‘performance’. Similarly, we identified MATs with a predominant focus on ‘performance’ (as measured through national tests and Ofsted grades), but these MATs would invariably claim they had a wider purpose (e.g. social mobility). In the same vein, some MATs prioritised ‘people’ issues while others were more clearly ‘process’ focused, but the two are not mutually exclusive.

In assessing the MATs that fall into each quadrant, we developed four descriptors – family, kingdom, machine and institution. These four descriptors are intended to provide broad heuristic devices aimed at characterising different MAT approaches and culture. The table in provides headline characteristics for each one, while Annex B provides more detailed descriptions and our own assessment of the strengths and weaknesses of each approach. As shown in , each of the four descriptors is associated with a quadrant of the framework, indicating that it reflects a dominant (but not exclusive) focus on two of the four areas (i.e. ‘purpose and people’ = family). In developing the descriptors for each quadrant we were inspired by Gareth Morgan’s (Citation2006) use of metaphors to characterise different perspectives on how organisations are conceived. Indeed, our use of ‘machine’ for the ‘performance and process’ quadrant reflects a similar Taylorist interpretation to Morgan’s. The other three names aim to capture the dominant areas of focus in each case as well as the values and cultures of the MATs we observed. In the case of ‘family’, we adopt language used by several interviewees, while the other two names reflect concepts from the wider literature: thus, ‘Kingdom’ MATs reflect the notion of Founder Syndrome (Block and Rosenberg Citation2002), while ‘Institution’ MATs reflect a focus on shared values and wider outcomes that chimes with the neo-institutional literature (Glatter Citation2017).

Conclusion

This article has explored the integration of new academies and knowledge exchange approaches in MATs, informed by M&A/PMI literature derived from other sectors.

In reflecting on the findings, we note that M&A scholars suggest that 70-90% of acquisitions in the private sector are ‘abysmal failures’ and the argument that acquiring companies should approach M&As in ‘give’ rather than ‘take’ mode (Martin Citation2016). The issue of MAT failures – either at entire MAT level or in terms of whether specific sponsorship arrangements succeed or not – has not been studied in depth. Robertson and Dickens (Citation2018) identified 91 MATs that closed or merged with another MAT between 2014 and 2018. This included some high profile cases of MATs that officially failed and were closed down by the government, while others have been ‘paused’ (i.e. prevented from growing) due to performance concerns (Greany and Scott, Citation2014). Many more individual academies have been re-brokered out of one MAT and into another, often as a result of formal intervention by the Department for Education. Allen-Kinross (Citation2019) reports that 307 academies moved to a new trust in 2018–2019, equating to 3.6 per cent of all open academies in England. This suggests that while M&As in the MAT sector are by no means always successful, the official ‘failure’ rate is nevertheless well below that seen in other sectors. Clearly, any such comparison requires caution, due to different measurement criteria between sectors: while ‘failure’ in the private sector might be assessed through profit and loss, in the MAT sector it appears to reflect only serious financial mismanagement or sustained poor performance on academic outcomes. Nevertheless, it seems fair to argue that most MATs take on under-performing schools driven by a desire to make a positive difference – in ‘give’ rather than ‘take’ mode.

Finally, we consider the significance and limitations of this article. Its contribution includes new empirical findings and an original framework for categorising MAT approaches, derived through a grounded approach but informed by wider organisational literature. Inevitably, the analysis also has limitations, some of which we discuss above relating to the limits of comparing M&A/PMI findings across sectors. Other limitations include the focus on approaches to school improvement, rather than wider structural integration, in the research, and the lack of opportunity to test and refine the categorisation framework with a wider pool of MATs.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Toby Greany

Toby Greany is Professor of Education and Convener of the Centre for Research in Education Leadership and Management (CRELM) at the University of Nottingham.

Ruth McGinity

Ruth McGinity is Assistant Professor in Educational Leadership and Policy and Head of Learning and Teaching in the Department of Learning & Leadership, UCL Institute of Education.

Notes

1 This figure includes all academy trusts with two or more schools – see https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/open-academies-and-academy-projects-in-development.

2 These decisions are subject to approval from the Secretary of State and require adherence to various official processes – see https://www.gov.uk/guidance/convert-to-an-academy-information-for-schools (accessed 22 July 2020).

3 This argument is challenged by Bernardinelli et al.’s (Citation2018) statistical analysis, which indicates that while smaller MATs (2–3 schools) make a positive impact on pupil outcomes overall, larger MATs (16+ schools) actually have a negative impact.

4 The research also included eight case studies of non-MAT collaborative structures, not drawn on here.

5 Using the Department for Education performance tables, which categorise MATs as ‘above average’, ‘average’ or ‘below average’, based on a number of variables. See: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/multi-academy-trust-performance-measures-at-key-stage-2-2018-to-2019.

6 Detailed findings are available in the main report (Greany Citation2018).

7 It is notable that he does not mention the board’s role here.

References

- Agnew, T. 2017. “By Working Together We Can Achieve So Much More.” North Academies Conference Speech. Accessed September 14, 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/lord-agnew-by-working-together-we-can-achieve-so-much-more.

- Allen-Kinross, P. 2019. “Academy Transfer Market Costs Hit £30 m as 300 More Schools Rebrokered This Year.” SchoolsWeek, July 18. Accessed September 14, 2020. https://schoolsweek.co.uk/academy-transfer-market-costs-hit-30m-as-300-more-schools-rebrokered-this-year/.

- Andrews, J. 2018. School Performance in Academy Chains and Local Authorities – 2017. London: Education Policy Institute.

- Andrews, J., and N. Perera. 2017. The Impact of Academies on Educational Outcomes. London: Education Policy Institute.

- Bernardinelli, D., S. Rutt, T. Greany, S. Rutt, and R. Higham. 2018. Multi-academy Trusts: Do They Make a Difference to Pupil Outcomes? London: UCL IOE Press.

- Birkinshaw, J., H. Bresman, and L. Hakanson. 2000. “Managing the Post-Acquisition Integration Process: How the Human Iintegration and Task Integration Processes Interact to Foster Value Creation.” Journal of Management Studies 37: 395–425.

- Birks, W. 2019. “To Compare the Creation and Development of School Culture in Amalgamated Schools and Multi-Academy Trusts from a Teacher Perspective; A Longitudinal, Mixed Methods Multiple Case Study.” Doctoral thesis. doi:https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.38972.

- Block, S. R., and S. Rosenberg. 2002. “Toward an Understanding of Founder's Syndrome: An Assessment of Power and Privilege Among Founders of Nonprofit Organizations.” Nonprofit Management and Leadership 12 (4): 353–368.

- Bodner, J., and L. Capron. 2018. “Post-merger Integration.” Journal of Organization Design 7: 3. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s41469-018-0027-4.

- Caves, R. 1989. “Mergers, Takeovers, and Economic Efficiency: Foresight vs. Hindsight.” International Journal of Industrial Organization 7 (10): 151–174.

- Courtney, S., and R. McGinity. 2020. “System Leadership as Depoliticisation: Reconceptualising Educational Leadership in a new Multi-Academy Trust.” Educational Management, Administration & Leadership. Published online https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143220962101.

- Crawford, M., B. Maxwell, J. Coldron, and T. Simkins. 2020. “Local Authorities as Actors in the Emerging “School-led” System in England.” Educational Review. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2020.1739625.

- Davies, P., C. Diamond, and T. Perry. 2019. “Implications of Autonomy and Networks for Costs and Inclusion: Comparing Patterns of School Spending Under Different Governance Systems.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143219888738.

- Department for Education. 2016. Multi-Academy Trusts: Good Practice Guidance and Expectations for Growth. London: DfE.

- Ehren, M., and D. Godfrey. 2017. “External Accountability of Collaborative Arrangements; A Case Study of a Multi Academy Trust in England.” Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability 29: 339–362. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-017-9267-z.

- Empson, L. 2001. “Fear of Exploitation and Fear of Contamination: Impediments to Knowledge Transfer in Mergers Between Professional Service Firms.” Human Relations 54: 839–862.

- Glatter, R. 2017. “Schools as Organizations or Institutions: Defining Core Purposes.” In School Leadership and Education System Reform, edited by P. Earley, and T. Greany, 17–25. London, UK: Bloomsbury.

- Graebner, M. E. 2004. “Momentum and Serendipity: How Acquired Leaders Create Value in the Integration of Technology Firms.” Strategic Management Journal 25: 751–777.

- Graebner, M. E., K. H. Heimeriks, Q. N. Huy, and E. Vaara. 2017. “The Process of Post-Merger Integration: A Review and Agenda for Future Research.” Academy of Management Annals 11 (1): 1–32. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2014.0078.

- Greany, T. 2018. Sustainable Improvement in Multi-School Groups. DfE Research report 2017/038. London: Department for Education.

- Greany, T. 2020. “Place-based Governance and Leadership in Decentralised School Systems: Evidence from England.” Journal of Education Policy. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2020.1792554.

- Greany, T., and R. Higham. 2018. Hierarchy, Markets and Networks: Analysing the ‘Self-Improving School-led System’ Agenda in England and the Implications for Schools. London: IOE Press.

- Greany, T., and R. McGinity. forthcoming. “Leadership and School Improvement in Multi-Academy Trusts.” In School Leadership and Education System Reform, pp170-186. 2nd ed., edited by T. Greany and P. Earley. London: Bloomsbury.

- Greany, T., and J. Scott. 2014. Conflicts of Interest in Academy Sponsorship Arrangements. London: House of Commons Education Select Committee.

- Haspeslagh, P. C., and D. B. Jemison. 1991. Managing Acquisitions. New York, NY: Free Press.

- Hawkins, D. 2005. The Bending Moment. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Hill, R., J. Dunford, N. Parish, S. Rea, and R. Sandals. 2012. The Growth of Academy Chains: Implications for Leaders and Leadership. Nottingham: National College for School Leadership.

- Hutchings, M., and B. Francis. 2017. Chain Effects 2017: The Impact of Academy Chains on Low Income Students. London: Sutton Trust.

- Martin, R. L. 2016. “M&A: The One Thing You Need to Get Right.” Harvard Business Review. Accessed September 14, 2020. https://hbr.org/2016/06/ma-the-one-thing-you-need-to-get-right.

- Menzies, L., S. Baars, K. Bowen-Viner, E. Bernardes, K. Theobald, and C. Kirk. 2018. Building Trusts: MAT Leadership and Coherence of Vision, Strategy and Operations. London: ASL.

- Mirvis, P. H., and M. L. Marks. 1992. Managing the Merger: Making it Work. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Morgan, G. 2006. Images of Organisation. NYC: Sage.

- Ofsted. 2019. Multi-academy Trusts: Benefits, Challenges and Functions. London: Ofsted.

- Robertson, A., and J. Dickens. 2018. “Hefty Bills for the Government as More Academy Trusts Close.” SchoolsWeek, November 16. https://schoolsweek.co.uk/hefty-bills-for-the-government-as-more-academy-trusts-close/.

- Sarala, R. M., R. Mirja, P. Junni, and C. Cooper. 2016. “A Sociocultural Perspective on Knowledge Transfer in Mergers and Acquisitions”. Journal of Management 42: 1230–1249. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314530167.

- Sarala, R. M., and E. Vaara. 2010. “Cultural Differences, Convergence, and Crossvergence as Explanationsknowlege Transfer in International Acquisitions.” Journal of International Business Studies 41: 1365–1390.

- Simon, C. A., C. James, and A. Simon. 2019. “The Growth of Multi-Academy Trusts in England: Emergent Structures and the Sponsorship of Underperforming Schools.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143219893099.

- Thomson, P. 2020. School Scandals: Blowing the Whistle on the Corruption of our Education System. London: Palgrave.

- West, A., and D. Wolfe. 2018. “Academies, the School System in England and a Vision for the Future: Executive Summary.” Clare Market Papers No. 23.

- Worth, J. 2017. Teacher Retention and Turnover Research Research Update 2 Teacher Dynamics in Multi-Academy Trusts. Slough: NfER.