ABSTRACT

This study employs social network analysis (SNA) to identify influential individuals and their communication patterns within Chinese schools in Wenzhou. The research also aims to reveal communication and advice-seeking patterns that significantly impact the overall distributed leadership structure and practices within the schools. The study employed a multistage random sampling method to select eight Chinese schools from Wenzhou, Zhejiang province. A total of 276 teachers completed a Social Network Survey (SNS) questionnaire, and UCINET Software was utilised to analyse the network data. The study found that each school exhibited a unique centrality, density, and reciprocity, leading to different key actors. Network properties demonstrated some associations with leadership distributions, with centrality being particularly prominent. Limited communication between principals and teachers was observed, which could potentially impact the distribution of leadership. This study provides valuable insights into the social dynamics of key players and groups within the network of the selected schools in China. The research introduces social network analysis as an alternative method for identifying the leadership practice structure in the school domain. By measuring the overall cohesion and fragmentation of the network, the study reveals the flow of information and influence between individuals.

Introduction

The adoption of collaborative and network-oriented approaches to educational leadership is imperative for successfully addressing the intricate challenges that schools confront and meeting the demands of evidence-based learning practices for all students (Chestnutt et al. Citation2023; Leithwood et al. Citation2023). This approach to educational leadership underscores the significance of the network and the individual actors comprising it, as the strength and quality of the connections and relationships between network actors are necessary for effective leadership practices (Tipurić Citation2022). Additionally, understanding social networks requires recognising the interdependence of individuals and their actions, the potential for information and resource diffusion through relational ties, the impact of relationship patterns on collaboration, and the structure of social network models (Carolan Citation2014). Previous studies (eg de Jong et al. Citation2022; Knaub, Henderson, and Fisher Citation2018; Sinnema et al. Citation2020; Von Mering and Citation2017) have shown that social network theory provides a useful perspective for understanding the dynamic impact of social processes and improving organisational efforts. Therefore, it is crucial to move beyond traditional organisational models with simplistic notions of school leadership and observe leadership through a network-oriented lens to empower effective leaders.

Balkundi and Kilduff (Citation2006) argue that effective leadership involves a comprehensive understanding of the connections and relationships among individuals, the strength and quality of these connections, the contributions and benefits of each individual within a network, and the presence of any divisions or separations within the network. Despite the persistence of traditional hierarchical leadership in contemporary school systems, which dominated from the late 1930s to the early 1980s, distributed leadership, emphasising various forms of collaboration and networking, presents a more intricate approach to school organisation (Harris, Jones, and Ismail Citation2022). This model enables leaders to re-examine their practice and consider the interdependence of organisational structures and forms (Harris, Jones, and Ismail Citation2022; Spillane Citation2006). In this study, we aim to identify influential individuals within the school network and analyse the patterns of internal networks to reveal strengths and weaknesses in the school’s leadership structure. We adopt the theoretical foundation of distributed leadership perspective and the social network theory to inform our investigation.

Distributed leadership perspective

The literature on school effectiveness and reform widely agrees that leadership is crucial to achieving successful school change (Fullan Citation2004; Heck and Hallinger Citation2014; Leithwood et al. Citation2023). Traditionally, leadership has been understood in terms of spatial positions within an organisation, where vertical hierarchy promotes control over subordinates, thereby facilitating school change. However, limiting leadership to a vertical hierarchy poses restrictions (Harris, Jones, and Ismail Citation2022). Leadership can also be horizontal, with employees or colleagues taking charge and guiding others in the right direction. Grint (Citation2010) argues that leaders, regardless of their vertical rank, engage in collaborative change without formal authority, aligning with the distributed leadership perspective. This perspective expands the sources of leadership beyond the principal to include multiple individuals, such as classroom teachers and administrators, without formal authority. The leadership practice is shaped by the actions and interactions of all those involved in problem-solving and developmental work (Mullick, Sharma, and Deppeler Citation2013). According to Harris (Citation2005), distributed leadership has three key features: it focuses on the practice itself rather than leadership functions or outcomes, emphasises relationships and interactions among people, and concentrates on the contextual conditions in which schools operate, as these factors shape and influence how distributed leadership manifests in schools.

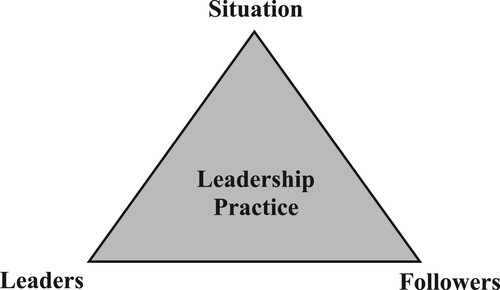

Spillane (Citation2006) proposes that the distributed leadership framework encompasses three core components: leader, follower, and situation, all of which are critical for analysing leadership practices (see ). It is important to note that understanding leadership from a distributed perspective does not diminish the influence of top leaders; rather, it elucidates the contributions of non-leadership employees in facilitating an organisation’s goal attainment. Distributed leadership, as an alternative framework, highlights both vertical and horizontal leadership processes and recognises the importance of contributions derived from both formal and informal roles (Spillane Citation2006). Such an approach enhances the sophistication of leadership analysis by acknowledging the complexity of leadership dynamics within organisations. According to Mullick, Deppeler, and Sharma (Citation2012), distributed leadership and social network theory complement each other by offering valuable perspectives and methodologies to explore the complexities of leadership structures and practices within an organisation. It indicates that the link between distributed leadership and social network theory lies in their shared emphasis on understanding the importance of relationships, interactions, and communication channels in shaping leadership practices within an organisation.

Figure 1. Distributed leadership framework (adapted from Mullick, Sharma, and Deppeler Citation2013).

Social network theory

According to Social Network Theory, individuals are not independent entities but are interconnected through various types of relationships, including self-chosen connections such as friendships, environmental ties, kinship, or departmental colleague bonds (Knaub, Henderson, and Fisher Citation2018). These relationships can positively or negatively influence individuals’ behaviour in networks (Hangul and Senturk Citation2019). Actors within social networks, whether they are people, groups, or organisations, can be analysed in terms of the interactions they have with one another, and a wealth of information can be gleaned from such analyses (Caduff et al. Citation2023). Thus, social network theory offers a sophisticated framework for understanding the complex social dynamics that underpin human behaviour and social structure.

The structure and quality of relational ties, along with their influence and constraints on larger social structures, constitute a central aspect of social networks (Borgatti and Foster Citation2003; Cross, Borgatti, and Parker Citation2002). This framework can also explain how individuals acquire, utilise, and are influenced by relational resources (Degenne and Forse Citation1999). Visual representations of social networks depict the connections between individuals within an organisation. A dense network structure indicates that actors have multiple connections with each other, leading to smooth and efficient flow of information and resources (Burt Citation1995). In contrast, a sparse network structure suggests that actors are less connected, resulting in a slower and delayed transfer of resources (Burt Citation1995). Actors occupying a central position within a network tend to have more ties to other actors, offering them more opportunities to mobilise resources (Burt Citation1995). While actors in marginal or isolated positions have limited options, actors in dense networks are more likely to be constrained by group norms and expectations. Therefore, Liou and Daly (Citation2018) contend that social network theory presents a valuable perspective and a robust set of methodologies for better comprehending the dynamic impact of social processes and providing relevant insights for organisational improvement efforts.

In the context of social network theory and its application to develop a research methodology, Social Network Analysis (SNA) has gained considerable popularity as a research approach across diverse fields and applications (Hoppe and Reinelt Citation2010). SNA highlights the significance of informal organisational structures, where influences and tasks are realised through friendships and contacts (Hill and Martin Citation2014). This implies that SNA acknowledges the interaction and overlap between formal and informal groups within an organisation, where the same members can belong to both types of groups. Therefore, the natural organisation emerges to fulfil socio-emotional needs that the bureaucratic structure cannot address, fostering a sense of belonging, trust, and understanding among employees (Hangul and Senturk Citation2019). However, the widespread adoption of SNA has resulted in an abundance of network-related data and findings, posing a significant challenge for researchers: how to interpret this wealth of information and draw meaningful conclusions.

In response to this challenge, scholars like Bender-Demoll (Citation2008) have undertaken the task of synthesising and consolidating a wide spectrum of SNA research. Through this endeavour, they aim to extract common themes and trends from numerous individual studies, offering valuable insights into the dynamics of social networks. Similarly, Kilduff and Tsai (Citation2003) conduct an in-depth exploration of the science of SNA and undertake a more extensive synthesis of SNA research, with a particular emphasis on organisational networks. Through their comprehensive analysis, they go beyond individual study results and explore the theoretical and methodological underpinnings of SNA.

Using SNA to study leadership practices in K-12 education

In the context of K-12 education reform, social networks have become vital for educators to communicate and seek advice, providing access to new ideas and perspectives that can enhance their work (Alexiev et al. Citation2010). Networks are believed to foster a positive campus climate and improve student outcomes (Daly et al. Citation2014). Informal social networks demonstrate typical communication patterns, such as social gatherings, private exchanges, and social media platforms like WeChat, as opposed to formal, structured meetings. These models facilitate the establishment of long-term interpersonal relationships, enabling the transfer and exchange of tacit knowledge and complex information crucial for organisational learning and innovation (Finnigan and Daly Citation2012; Tsai and Ghoshal Citation1998). Therefore, in addition to individuals with clearly defined roles critical to organisational effectiveness, attention should be given to the informal network formed by spontaneous relationships among colleagues sharing common interests. These relationships can promote mutual understanding and enhance the overall functioning of the organisation (Cross, Borgatti, and Parker Citation2002; Schermerhorn et al. Citation2002).

When applied to studying leadership practices in schools, SNA allows researchers to diagnose the school’s current operational state by examining the network’s shape, structure, density, and location (Chestnutt et al. Citation2023; Quardokus Fisher et al. Citation2019). SNA also reveals the informal organisational structure within the school and identifies who occupies the central position in the social network and thus has a greater influence on other faculty members. This approach facilitates the formation of a more cohesive and collaborative environment that harnesses a broader range of resources, leading to the transformation and development of the school (Sinnema et al. Citation2020). That means by applying social network analysis to the study of distributed leadership, researchers and practitioners can gain valuable insights into how information, authority, and decision-making flow through the network of staffs of a school (Chestnutt et al. Citation2023). In response to the need to understand how information, authority, and decision-making flow through the school network in China, the present study investigates the following research questions:

Who are the influential individuals within the school networks of Chinese schools in Wenzhou, and how do their leadership roles and contributions differ from other actors?

What are the communication patterns between influential individuals and other actors in the schools, and how do these patterns influence the overall leadership practice structure?

How do centrality, density, and reciprocity within the social network of Chinese schools in Wenzhou impact the distribution of leadership roles among key actors?

Methodology

Research procedure and measurements

This study employs SNA as its research method, utilising a Social Network Survey (SNS) specifically designed for this purpose. The approach aims to explore leadership in a distributed manner and identify individuals responsible for managing and leading an organisation with significant influence over its members. To achieve this, the Social Network Questionnaire used in the study was adapted from Pitts and Spillane (Citation2009) and the School Staff Social Network Questionnaire developed by Mullick, Deppeler, and Sharma (Citation2012). To incorporate the unique Chinese school background and culture, the questionnaire was translated into Chinese and pilot-tested in a school to ensure clarity and eliminate any language that might cause confusion.

The SNS comprised inquiries designed to comprehend connections between members of school communities and potential influences. Participants were first asked to identify individuals they typically sought help from when encountering teaching and non-teaching complex problems in their day-to-day working life, emerging collaborative leaders in their school, and types of leadership communication used in their schools. Next, each participant identified the primary benefit they currently receive from the organisational leadership network functioning, as shown in . Specifically, respondents were queried regarding how their colleagues aided and supported them in their work, the value of the information provided, and how often such individuals furnished helpful information (ie ‘very frequently,’ ‘often,’ or ‘occasionally’). Additionally, respondents were asked to identify the person(s) they most frequently consulted for guidance when making significant school-related decisions during the past six months and from whom they sought advice and suggestions when implementing new education and teaching policies during the same period.

Table 1. Functions in organizational leadership network.

Sample and data collection

A multi-stage method was employed to select schools for the research sample in this quantitative study. Specifically, the study targeted four districts covering eight schools (five primary schools and three middle schools) located in Wenzhou, Zhejiang Province. Schools A and B (ie alphabets used as pseudonyms) were selected randomly from Ouhai District, while School C was chosen from Taishun County. Schools D and E were from Longwan District, and Schools F, G, and H were selected from Ruian City. The researchers adhered to ethical guidelines established by their affiliated university and the Bureau of Education in Wenzhou when approaching all teachers in the selected schools to participate in the study. A total of 276 samples were administered, indicating that this study concentrated on the participation of at least 50% of the teachers and school leaders. Data were collected in Chinese using a Chinese online survey application called ‘Wen Juan Xing’ (Questionnaire Star). The demographic characteristics of the samples (see ) indicate two prominent similarities: the majority of teachers hold a bachelor’s degree, and the proportion of female teachers is relatively high across all schools. The study also highlights three significant distinctions among the schools: years in the current position, years of work experience, and the age of teachers.

Table 2. Sample characteristics.

Data analysis

As mentioned above, the study employed a comprehensive methodology to analyse social network patterns among participants across multiple schools. This study used UCINET Software to analyse social networks. Organising relational information about network participants into a matrix that detailed how each participant was related to other participants in a particular position and how often they sought help and advice from each other determined the network’s centrality, density, and reciprocity. This data was plotted using UCINET (Borgatti, Everett, and Freeman Citation2002) to calculate the complex relationships and communication patterns among teachers, teacher leaders, and leaders within and between different schools. By identifying influential and connected participants within the leadership network, the analysis offers strategies for improving communication and collaboration among participants in different organisational positions.

Findings

Visual analysis of social network

SNA is a comprehensive framework comprising theories, tools, and processes aimed at elucidating network relationships and structures (Hoppe and Reinelt Citation2010). Within a network, nodes represent employees in schools or can symbolise events, ideas, objects, and more. The links between nodes denote the relationships connecting them. Line lengths and node positions in the social graph reflect connection frequency, with closely located nodes connected by shorter lines indicating stronger relationships and more frequent communication among workers (Brandes and Erlebach Citation2005). Bridgers, who play a crucial role in leadership networks, are often overlooked due to the invisibility of their significant ties when merely counting the number of relations. Detecting Bridgers is an essential SNA application, as they serve as valuable key informants during evaluations, possessing access and knowledge of the broader network. Bridgers are typically identified using the betweenness centrality calculation (Freeman Citation1978), which highlights their vital role as relay points between other network members. Additionally, SNA metrics such as density, the number of links in a network divided by the maximum possible number of links (Hoppe and Reinelt Citation2010), and degree centrality, commonly used to study team leadership (Carson, Tesluk, and Marrone Citation2007), are crucial in the analysis. It is important to note that this paper’s SNA metrics assume that the network’s number of nodes and links is known, and the maximum possible number of links in an undirected network is N(N−1)/2, while for a directed network, it is N(N−1).

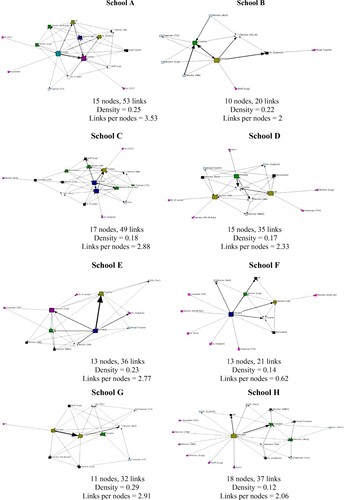

Position, communication and function

In , the network analysis of different schools’ leadership structures reveals that School A’s principal and teacher occupy significant positions in the network, with key communication from the vice-principal, director of academic affairs, subject group leader, director of political and educational affairs, and staff logistics. However, the Teacher Union chairperson has limited communication, and other staff members are at the periphery, indicating a need for increased contact with the principal and teacher. In School B, the principal and teachers have considerable influence, with reciprocal relationships observed with the subject group leader, director of academic affairs, and director of students’ affairs division. Nevertheless, the head teacher’s peripheral position indicates the necessity for more interaction with the principals and teachers frequently with the vice-principal, director of school affairs, teachers, director of academic affairs, and director of political and educational affairs. The teacher shows the highest connection degree, suggesting the need for better communication with other members.

In School D, the principal, vice-principal, and director of school affairs hold pivotal positions, while other members are peripheral, calling for improved communication. Similarly, in School E, the principal and director of logistics are crucial, and reciprocal relationships exist between the principal and the vice-principal, head teacher, and director of school affairs. School F highlights the principal as the core member with the most decisive influence, and the principal has the closest connections to various positions. In School G, the principal and vice-principal significantly influence the organisation, with the vice-principal closely connected to the director of academic affairs. The network diagram suggests a stable relationship among all members, though the youth leagues require more communication. Finally, in School H, the principal holds the central position, exercising the highest level of influence and control, while the secretary of the party committee needs more communication with the principal.

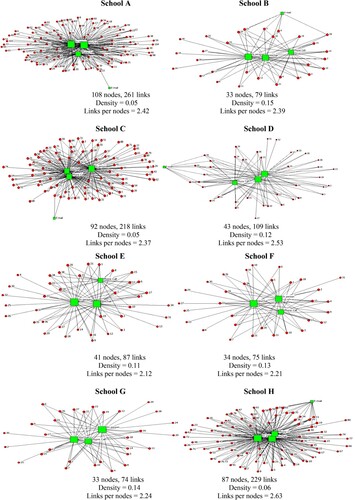

Based on the findings presented in , the analysis of ‘school personnel interactions’ reveals the communication methods employed by school personnel when reaching out to individuals they interact with most frequently. Notably, schools E, F, and G show a tendency to refrain from using email for such interactions, and although other schools do use email, its usage remains infrequent. Instead, most schools prefer utilising WeChat and engaging in face-to-face interactions more frequently, with phone calls being another commonly adopted mode of communication. Furthermore, schools A and C exhibit the lowest density, indicating sparse or infrequent connections between nodes within their networks. Conversely, school B stands out with the highest density, signifying more frequent and complex relationships between nodes. School H, on the other hand, boasts the highest number of links per node, suggesting that this may lead to a greater frequency of intricate information exchange and interaction within the network.

In , the analysis of ‘function’ illustrates the primary benefits obtained by school personnel. Across all schools, most school personnel receive fewer benefits from access to decision-makers that allow them to advance their plans and diplomatic support that enables plan advancement. However, schools B, F, and H exhibit a more even distribution of benefits across the seven aspects. Schools A and C have the lowest density, indicating sparse or infrequent connections between nodes within their networks. On the contrary, school B stands out with the highest density and the most significant number of links per node, indicating frequent and complex relationships between nodes. This likely leads to more frequent and intricate information exchange and interaction within the network.

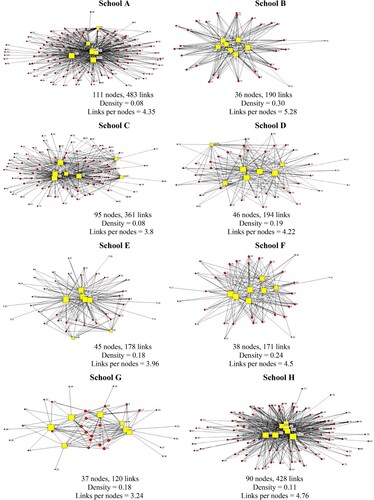

Centrality analysis

The centrality networks of School A and H were selected as samples to investigate school structures in this study. Upon analysing the centrality network measures for School A (see ), it was observed that the principal held the highest out-eigenvector, while the teacher had the highest in-eigenvector, indicating that both wield significant influence within the school network. As explained by Kolleck (Citation2016), centrality measures the extent to which an actor or group controls power or influence within a network by assessing their level of control. In the context of networks, Degree Centrality quantifies the amount of information an actor receives from others (see ).

Table 3. Social network analysis indicators.

In contrast, Betweenness measures how often an actor assumes connecting positions between actors who are not directly connected. Closeness, on the other hand, assumes that a node’s centrality is determined by its distance from other nodes. Additionally, Eigenvector measures influence based on the central value of an actor’s contacts. Furthermore, the principal demonstrated the highest out-degree, implying that they are more attentive to other individuals in the school network and possess strong communication skills. As a leader, the principal can gather more information from other participants to benefit the school’s development. Conversely, the teacher exhibited the highest in-degree, suggesting that they are the most engaged and invested members within the network. The teacher’s higher betweenness centrality than the principal indicates a greater activity as an intermediary. Moreover, the principal’s highest out-beta centrality implies their ability to influence others in the network and assume distributed leadership roles ().

Table 4. Centrality properties school (A).

Upon analysing the centrality network measures for School H () above, it was found that the principal held the highest out-eigenvector, while the teacher had the highest in-eigenvector, indicating that both play significant and influential roles in the school network. Furthermore, the principal’s highest out-degree and betweenness centrality suggest that they prioritise the well-being of others in the school network and contribute to the school’s overall growth. However, the highest in-degree was observed for teachers, implying that they are the most attentive and involved network members. Additionally, the principal’s highest out-beta centrality highlights their ability to influence others in the network and assign leadership roles.

Table 5. Centrality properties school (H).

Reciprocity analysis

Reciprocity measures how much individuals in a network recommend each other for giving or receiving advice (see ). Among all schools, School B demonstrates the greatest level of reciprocity, while School F has the lowest. Specifically, 33% of participants in School B had mutual connections with all other participants, indicating a greater consistency in staff giving and receiving advice. In contrast, only 5% of participants in School F had reciprocal connections, suggesting disparities in the number of staff members who gave or received advice from one another.

Table 6. Reciprocity properties.

Density analysis

The data from the eight schools exhibit a range of network connectivity, varying from low to high. Additionally, with the exception of School E, all schools had participants with a density of zero, suggesting that they were only connected to one other participant in the school network and occupied peripheral positions in the network (see ). A comparison of the overall network density across the eight schools reveals that participants in School H are less interconnected, while those in School G are more tightly linked.

Table 7. Density properties.

Discussion

While the focus of mapping the leadership structure includes various positions, the analysis of communications and functions within Chinese schools via SNA clarifies that certain schools are in the early stages of implementing distributed leadership, emergent teacher-leader roles, or mutual communications within a flat school structure in this study. The findings also reveal that some schools are in the early stages of implementing distributed leadership, emergent teacher-leader roles, or mutual communications within a flat school structure. However, a significant number of schools continue to adopt the traditional vertical design with top-down communications. These results align with previous research, indicating the pivotal role of highly central staff members within a school’s leadership team (Chestnutt et al. Citation2023; de Jong et al. Citation2022), particularly those formally appointed to perform primary counseling functions, placing them at the centre of the school’s counseling network (Knaub, Henderson, and Fisher Citation2018; Ortega, Thompson, and Daniels Citation2019).

To determine the influence of actors in a particular information flow, we need to consider their relative position (Kolleck Citation2016). Research results have shown that the principals of the eight schools have the highest contribution. Representative principals have extensive social contacts in six schools and are the best group to provide external advice. Among them, schools A and B, C, D, E, and H have the highest principal beta centrality, proving the most substantial influence of this position and the most crucial facilitator (Storey et al. Citation2021). On average, principals occupy more central roles in informal networks. This suggests that the post is a significant source of collaboration for others seeking to interact and holds the knowledge and information that teachers and other staff desire to improve their practice (Mowrey Citation2021). Therefore, central actors are influential actors who possess the experience, expertise, and characteristics to control the transfer and flow of information and resources, which are intrinsic to professional learning, teaching reform, and implementing reform (Hangül and Şentürk Citation2022).

Generally, to evaluate the influence of actors in information flow, their relative positions within the network were considered, with a specific emphasis on central actors (Sinnema et al. Citation2020). Following the same process, this study identified principals as the most influential actors among the eight schools under examination. Representative principals exhibited extensive social contacts across six schools, making them valuable sources of external advice and support. Notably, schools A, B, C, D, E, and H stood out, as their principals displayed the highest principal beta centrality, indicating their significant influence and critical facilitation role (Storey et al. Citation2021). The central position of principals within informal networks underscores their role as key collaborators, facilitating interaction and knowledge exchange among teachers and staff. Principals possess the experience, expertise, and characteristics necessary to control the transfer and flow of information and resources, which play a crucial role in supporting professional learning, implementing teaching reforms, and effectively executing educational changes (Hangül and Şentürk Citation2022; Quardokus Fisher et al. Citation2019).

Upon analyzing the suggested network, an intriguing finding emerged, revealing that school principals designated as leaders for schools F and G displayed lower beta centrality. This observation suggests a potential perception among school staff that these principals are heavily occupied with school affairs, leading them to seek advice from alternative positions. Additionally, the presence of less connected actors at the fringes of the network indicates a crucial need for improved access to information. Addressing the isolation of these actors becomes imperative in enhancing overall connectivity and fostering collaborative efforts within the school community (Hangul and Senturk Citation2019). Implementing strategic measures, such as organising staff into teaching-focused teams and enhancing dialogue levels, can effectively mitigate isolation and cultivate a more cohesive and efficient school environment (Harris, Jones, and Ismail Citation2022). Emphasising the refinement and reform of teaching practices emerges as a pivotal approach towards accomplishing this objective (Woodland and Mazur Citation2019).

In this study, the analysis of the network’s density table also reveals noteworthy findings regarding the communication patterns within schools. Schools C, D, F, and H demonstrate lower densities, indicating a lower frequency of seeking advice among individuals. In these schools, advice may have been primarily sought from a single individual, and there were instances where no advice-seeking behaviour was observed (Rigby, Andrews-Larson, and Chen Citation2020). In contrast, Schools A, B, E, and G exhibit higher densities, signifying more connections and better access to resources, with multiple redundant access points to the same resources. Moreover, an analysis of the overall reciprocity data reveals that School F exhibits the lowest reciprocity, implying the necessity for more reciprocated aid relationships. Prior research studies have demonstrated that increased interaction among various actors fosters a denser and more reciprocal network, contributing to a positive and cooperative school climate characterised by mutual respect and shared responsibility (Chestnutt et al. Citation2023; de Jong et al. Citation2022; Ortega, Thompson, and Daniels Citation2019).

Moreover, upon analysing the overall reciprocity data of each school, a noteworthy observation emerges – School F exhibits the lowest reciprocity, indicating a higher need for reciprocated aid relationships. Prior research has convincingly demonstrated that schools tend to favour increased interaction among various actors, and a denser and more reciprocal network is associated with a positive and cooperative school climate characterised by mutual respect and shared responsibility (Ortega, Thompson, and Daniels Citation2019; Sinnema et al. Citation2020). Notably, the social network graph is significantly influenced by staff demographics, including factors such as tenure, education, age, and gender. As a result, staff members keenly observe and evaluate their colleagues’ personalities, receptiveness to dialogue, willingness to offer assistance, level of expertise, and overall competence. According to Hangül and Şentürk (Citation2022), relationships among colleagues may be shaped by diverse criteria, including teaching subject, organisational position, availability, expertise, occupation, or even the school affiliation.

The survey responses prominently underscore the proactive involvement of school employees in providing information, guidance, and support to their colleagues, thereby facilitating collaborative problem-solving and the seising of opportunities. Moreover, the research comprises both rural and urban schools, where the reliance on formal or informal networks is influenced by the size of the school. Smaller schools exhibit a higher frequency of interactions among educators, resulting in less-established traditional structures (Liou and Daly Citation2018). In contrast, larger schools in this study manifest diverse relational patterns and professional cultures, guided by established legal systems. Smaller schools tend to place greater emphasis on informal conversations, while larger schools rely more heavily on formal structures to govern relationship development and network dynamics (Mowrey Citation2021). Despite these disparities, an imperative to examine the social network structure remains universal, as it facilitates the identification of areas for improvement and fosters enhanced collaboration among stakeholders, ultimately contributing to improved overall school performance.

Conclusion

In this study, UCINET network graphs were employed to visualise the network structure and position distributions of each school, facilitating social network analyses and the development of relevant expertise to design campaigns and communities that equitably engage a broad range of actors in meaningful and urgent change (Quardokus Fisher et al. Citation2019). Simultaneously, the examination of each network graph’s centrality, density, and reciprocity revealed specific characteristics in greater detail (Caduff et al. Citation2023). The findings of this study carry both theoretical and practical implications. The study aimed to bridge the gap in understanding the impact of network relationships, collaboration, and knowledge dissemination in schools, particularly in the context of distributed leadership practices and their influence on school and student outcomes. By recognising leaders with and without formal designations and assessing the intensity of their influence in improving instructional practices and student performance, this research offers valuable theoretical insights. Additionally, this study sheds light on distribution patterns that may exist within schools, thus contributing to the theoretical understanding of school network dynamics.

From a practical perspective, the study’s findings hold significant value for school management and policymakers. The research reveals that decentralised networks with a high degree of reciprocity can effectively promote the exchange of knowledge and skills among members involved in the network. The visual presentation of social network analysis simplifies its comprehension for school leaders, minimising potential obstacles in grasping the underlying principles of the data. Policymakers, in particular, can leverage the study’s findings to understand the social embeddedness of actors in schools and their influence in specific problem domains. This understanding can inform the development of relevant expertise and the design of campaigns to foster positive change and equitable school reforms.

However, this study also faces certain limitations that require acknowledgment. First, the investigation solely explores advisory networks and leadership within eight schools, each possessing its unique social environment and context. Second, the sample size of the questionnaire survey was limited, and response rates in some schools were below 50%, potentially constraining the generalizability of research findings and making cross-school comparisons challenging. Therefore, future studies with larger and more diverse samples are essential to corroborate the generalizability of these findings across a broader range of educational contexts. Moreover, exploring other factors that may influence the functioning and structure of school networks, such as the socioeconomic status of the community or the type of school, could provide valuable insights to enrich the understanding of school network dynamics.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jahirul Mullick

Jahirul Mullick is an Assistant Professor of Educational Leadership at the College of Education and also serves as Director of the LEAD Research Institute at Wenzhou-Kean University, China. With nearly two decades of experience, Dr. Mullick has made significant contributions to the field of education through teaching and research studies in Australia, Bangladesh and China. His primary areas of expertise include educational leadership and management, inclusive education, behavior analysis, positive behavior support, and teacher development. Currently, Dr. Mullick is engaged in international studies focusing on inclusive school leadership, distributed leadership practices, parental perspectives on educating children with additional needs, and inclusive STEAM pedagogy.

Qiusu Wang

Qiusu Wang is a doctoral student and Graduate Research Assistant at Wenzhou-Kean University's LEAD Research Institute, focusing her research on inclusive education and educational leadership practices. She holds a Bachelor of Science in Economics and Statistics and a Master of Science in Applied Economics and Predictive Analysis, both from Southern Methodist University in the United States. In addition, she expanded her academic qualifications with a Master of Science in Education from Johns Hopkins University. Prior to commencing her EdD studies, Ms. Wang acquired valuable teaching experience in mathematics at a primary school in the United States.

Midya Yousefi

Midya Yousefi is an assistant professor in the Ed.D. & MA programs at Wenzhou-Kean University. She earned her Ph.D. in Educational Leadership and Management and MEd in Educational Administration and Management from the Research University of Science Malaysia. With nine years of teaching experience, she has instructed students from various countries from Asia and Africa. She has taken on leadership roles as the program leader for the MSc. in Education Management and the Head of the Centre for Leadership & Development in Malaysia. Dr. Yousefi is skilled in quantitative research and has conducted statistical software workshops on statistical software like SPSS, AMOS, and SmartPLS in Malaysia, the Middle East, and China. She has also supervised Ph.D., MA, and DBA students in their dissertation work.

References

- Alexiev, Alexander S., Justin J. P. Jansen, Frans A. J. Van den Bosch, and Henk W. Volberda. 2010. “Top Management Team Advice Seeking and Exploratory Innovation: The Moderating Role of TMT Heterogeneity.” Journal of Management Studies 47 (7): 1343–1346. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.00919.x.

- Balkundi, Prasad, and Martin Kilduff. 2006. “The Ties that Lead: A Social Network Approach to Leadership.” The Leadership Quarterly 17 (4): 419–439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2006.01.001.

- Bender-Demoll, Skye. 2008. “Potential Human Rights Uses of Network Analysis and Mapping A Report to the Science and Human Rights Program of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.” Skyeome.net. 2008. http://skyeome.net/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2008/05/Net_Mapping_Report.pdf.

- Borgatti, Stephen P., Martin G. Everett, and Linton C. Freeman. 2002. UCINET for Windows: Software for Social Network Analysis. Harvard, MA: Analytic Technologies.

- Borgatti, S. P., and P. C Foster. 2003. “The Network Paradigm in Organizational Research: A Review and Typology.” Journal of Management 29 (6): 991–1013. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-2063_03_00087-4.

- Brandes, Ulrik, and Thomas Erlebach. 2005. “Introduction.” In Network Analysis: Methodological Foundation, edited by Ulrik Brandes and Thomas Erlebach, 1–6. Berlin: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-31955-9_1.

- Burt, Ronald S. 1995. Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition. London, UK: Harvard University Press.

- Caduff, Anita, Alan J. Daly, Kara S. Finnigan, and Christina C. Leal. 2023. “The Churning of Organizational Learning: A Case Study of District and School Leaders Using Social Network Analysis.” Journal of School Leadership 33 (4): 355–381. https://doi.org/10.1177/10526846221134006.

- Carolan, Brian V. 2014. Social Network Analysis and Education: Theory, Methods & Applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Carson, J. B., P. E. Tesluk, and J. A. Marrone. 2007. “Shared Leadership in Teams: An Investigation of Antecedent Conditions and Performance.” Academy of Management Journal 50 (5): 1217–1234. https://doi.org/10.2307/20159921.

- Chestnutt, Hannah, Trista Hollweck, Nilou Baradaran, and María Jiménez. 2023. “Mapping Distributed Leadership Using Social Network Analysis: Accompaniment in Québec.” School Leadership & Management 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2023.2198551.

- Cross, Rob, Stephen P. Borgatti, and Andrew Parker. 2002. “Making Invisible Work Visible: Using Social Network Analysis to Support Strategic Collaboration.” California Management Review 44 (2): 25–46. https://doi.org/10.2307/41166121.

- Daly, Alan J., Nienke M. Moolenaar, Claudia Der-Martirosian, and Yi-Hwa Liou. 2014. “Accessing Capital Resources: Investigating the Effects of Teacher Human and Social Capital on Student Achievement.” Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education (1970) 116 (7): 1–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811411600702.

- Degenne, Alain, and Michel Forse. 1999. Introducing Social Networks. London, UK: SAGE Publications.

- de Jong, W. A., J. Brouwer, D. Lockhorst, R. A. M. de Kleijn, J. W. F. van Tartwijk, and M. Noordegraaf. 2022. “Describing and Measuring Leadership within School Teams by Applying a Social Network Perspective.” International Journal of Educational Research Open 3:100116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedro.2021.100116.

- Finnigan, Kara S., and Alan J. Daly. 2012. “Mind the Gap: Organizational Learning and Improvement in an Underperforming Urban System.” American Journal of Education 119 (1): 41–71. https://doi.org/10.1086/667700.

- Freeman, Linton C. 1978. “Centrality in Social Networks Conceptual Clarification.” Social Networks 1 (3): 215–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-8733(78)90021-7.

- Fullan, Michael. 2004. Leadership & Sustainability: System Thinkers in Action. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Grint, Keith. 2010. Leadership: A Very Short Introduction: A Very Short Introduction. London, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Hangul, Sükrü, and Ilknur Senturk. 2019. “Analyzing Teachers’ Interactions through Social Network Analysis: A Multi-Case Study of Three Schools in Van, Turkey.” New Waves 22 (2): 16–36.

- Hangül, Şükrü, and İlknur Şentürk. 2022. “Una investigación de las redes de asesoramiento docente y el liderazgo emergente a través del análisis de redes sociales.” European Journal of Education and Psychology 15 (1): 1–27. https://doi.org/10.32457/ejep.v15i1.1641.

- Harris, Alma. 2005. “Reflections on Distributed Leadership.” Management in Education 19 (2): 10–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/08920206050190020301.

- Harris, Alma, Michelle Jones, and Nashwa Ismail. 2022. “Distributed Leadership: Taking a Retrospective and Contemporary View of the Evidence Base.” School Leadership & Management 42 (5): 438–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2022.2109620.

- Heck, Ronald H., and Philip Hallinger. 2014. “Modeling the Longitudinal Effects of School Leadership on Teaching and Learning.” Journal of Educational Administration 52 (5): 653–681. https://doi.org/10.1108/jea-08-2013-0097.

- Hill, Robert M., and Barbara N. Martin. 2014. “Using Social Network Analysis to Examine Leadership Capacity within a Central Office Administrative Team.” International Journal of Learning Teaching and Educational Research 6 (1): 1–19.

- Hoppe, Bruce, and Claire Reinelt. 2010. “Social Network Analysis and the Evaluation of Leadership Networks.” The Leadership Quarterly 21 (4): 600–619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.06.004.

- Kilduff, Martin, and Wenpin Tsai. 2003. Social Networks and Organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Knaub, Alexis V., Charles Henderson, and Kathleen Quardokus Fisher. 2018. “Finding the Leaders: An Examination of Social Network Analysis and Leadership Identification in STEM Education Change” International Journal of STEM Education 5 (1): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-018-0124-5.

- Kolleck, Nina. 2016. “Uncovering Influence through Social Network Analysis: The Role of Schools in Education for Sustainable Development.” Journal of Education Policy 31 (3): 308–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2015.1119315.

- Leithwood, Kenneth, Jingping Sun, Randall Schumacker, and Cheng Hua. 2023. “Psychometric Properties of the Successful School Leadership Survey” Journal of Educational Administration 61 (4): 385–404. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-08-2022-0115.

- Liou, Yi-Hwa, and Alan J. Daly. 2018. “Broken Bridges: A Social Network Perspective on Urban High School Leadership.” Journal of Educational Administration 56 (5): 562–584. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-01-2018-0010.

- Mowrey, Sascha C. 2021. “Triangulating Social Networks and Experiences of Early Childhood Educators in Emergent Professional Cultures.” Early Childhood Education Journal 49 (3): 527–537. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-020-01096-8.

- Mullick, Jahirul, Joanne Deppeler, and Umesh Sharma. 2012. “Leadership Practice Structures in Regular Primary Schools Involved in Inclusive Education Reform in Bangladesh.” The International Journal of Learning: Annual Review 18 (11): 67–82. https://doi.org/10.18848/1447-9494/CGP/v18i11/47819.

- Mullick, Jahirul, Umesh Sharma, and Joanne Deppeler. 2013. “School Teachers’ Perception About Distributed Leadership Practices for Inclusive Education in Primary Schools in Bangladesh.” School Leadership & Management 33 (2): 151–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2012.723615.

- Ortega, Lorena, Ian Thompson, and Harry Daniels. 2019. “School Staff Advice-Seeking Patterns Regarding Support for Vulnerable Students.” Journal of Educational Administration 58 (2): 151–170. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-12-2018-0236.

- Pitts, Virginia M., and James P. Spillane. 2009. “Using Social Network Methods to Study School Leadership.” International Journal of Research & Method in Education 32 (2): 185–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437270902946660.

- Quardokus Fisher, Kathleen, Ann Sitomer, Jana Bouwma-Gearhart, and Milo Koretsky. 2019. “Using Social Network Analysis to Develop Relational Expertise for an Instructional Change Initiative.” International Journal of STEM Education 6 (1): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-019-0172-5.

- Rigby, Jessica G., Christine Andrews-Larson, and I-Chien Chen. 2020. “Learning Opportunities About Teaching Mathematics: A Longitudinal Case Study of School Leaders’ Influence.” Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education (1970) 122 (7): 1–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146812012200710.

- Schermerhorn, John R., James Hunt, Richard N. Osborn, and Mary Uhl-Bien. 2002. Organizational Behavior. 11th ed. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

- Sinnema, Claire, Alan J. Daly, Yi-Hwa Liou, and Joelle Rodway. 2020. “Exploring the Communities of Learning Policy in New Zealand Using Social Network Analysis: A Case Study of Leadership, Expertise, and Networks.” International Journal of Educational Research 99:101492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2019.10.002.

- Spillane, James P. 2006. Distributed Leadership. London, UK: Jossey-Bass.

- Storey, Kate E., Jodie A. Stearns, Nicole McLeod, and Genevieve Montemurro. 2021. “A Social Network Analysis of Interactions About Physical Activity and Nutrition among APPLE Schools Staff.” SSM - Population Health 14:100763. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100763.

- Tipurić, D. 2022. The Enactment of Strategic Leadership: A Critical Perspective. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-03799-3.

- Tsai, W., and S. Ghoshal. 1998. “Social Capital and Value Creation: The Role of Intrafirm Networks.” Academy of Management Journal 41 (4): 464–476. https://doi.org/10.2307/257085.

- Von Mering, Martha H. 2017. “Using Social Network Analysis to Investigate the Diffusion of Special Education Knowledge within a School District.” PhD diss., University of Massachusetts Amherst. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/983/.

- Woodland, Rebecca H., and Rebecca Mazur. 2019. “Examining Capacity for “Cross-Pollination” in a Rural School District: A Social Network Analysis Case Study” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 47 (5): 815–836. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143217751077.