ABSTRACT

Previous research suggests that lower socioeconomic status (SES) adolescents bully more than their higher-SES peers. This paper tests whether aggression-related mindsets, defined as mindsets that theoretically influence aggressive behavior, explain the relationship between SES and bullying engagement among adolescents. Using a large and diverse dataset of survey responses from secondary students in the U.S. (N = 146,044 students, 30% White, 70% students of color from 5th-12th grade), this study applies structural regression modeling with complex survey data analysis. Results suggest that differences in aggression-related mindsets, including feelings of academic efficacy, feelings of purpose, global self-esteem, academic-status insecurity, school-related anger, and school-related happiness account for almost half of the relationship between SES and bullying. Students’ school-related anger is the strongest direct predictor of bullying (0.88 standard deviation), which suggests that strategies to reduce adolescent bullying are more effective if they teach anger-reducing skills or eliminate the root causes of students’ school-related anger.

Introduction

International research suggests that bullying behavior among students is a universal phenomenon (Lee Citation2012; Shaw Citation2012; Akiba Citation2010; Pepler et al. Citation2008; Wolke Citation2001) and is highly prevalent in schools (Musu-Gillette et al. Citation2015). All involved students, including bullies, victims, and bystanders can suffer harmful consequences (Twemlow and Sacco Citation2011), which include lower emotional well-being (Hyman Citation2006; Ross Citation1996; Olweus Citation1993; Rigby and Slee Citation1993), lower educational achievement, and lower educational attainment (Strøm Citation2013; Ponzo Citation2013; Crosnoe Citation2011; Mah Citation2009; Barth et al. Citation2004), among others. It is also well-known that some student groups bully more than others. Significant differences in bullying behavior have been found between racial, ethnic, gender, age, and socioeconomic status (SES) groups (Dietrich and Ferguson Citation2019; Fisher et al. Citation2015; Yeager and Dweck Citation2012; Schumann Citation2013; Graham and Juvonen Citation2002). However, knowledge about the causes of group-differences in bullying behavior is scarce, which creates the danger of stereotypical and genetic/racist theories filling the gap. To avoid such simplistic rationalizations, evidence-based research is required to find more plausible explanations for group differences in bullying and other negative behavior.

Research on the role of mindsets in bullying behavior shows promise to help fill this gap (Yeager and Dweck Citation2012; Dietrich and Ferguson Citation2019). It has focused on adolescents who tend to engage more in bullying behavior than other age-groups (Goldbaum Citation2007) and who are less responsive to conventional anti-bullying interventions (Yeager et al. Citation2015), which suggests that the causes of adolescent bullying behavior are still poorly understood. The main purpose of this study is to add on to mindset research and explore the hypothesis that aggression-related mindsets – i.e. mindsets that have been found or theorized to influence general aggressive behavior – account for group-differences in bullying among adolescents.

Mindsets and their impact on human behavior

Empirical evidence and theory support the idea that mindsets play an important role in bullying behavior among adolescents. Mindsets have drawn a lot of attention in the field of social-emotional development, because mindset-altering interventions have shown very strong results with comparatively little effort to implement (Jones Citation2016; Yeager et al. Citation2013). These studies have confirmed that a switch from fixed to growth mindsets – from the belief that academic outcomes are primarily the result of inert differences in ability to the belief that they are due to differences in effort – positively changes students’ long-term academic development (Yeager and Walton Citation2011; Yeager, Trzesniewski, & Dweck, Citation2013). The impressive results are attributed to students with growth mindsets ascribing academic failure to a lack of effort, which leads them to study more, which in turn leads to better academic outcomes (Yeager and Walton Citation2011). In contrast, students with fixed mindsets give up early, because they believe that academic failure reflects a lack of inert ability. Such students see no point in increasing their study effort. Hence, theory and empirical evidence suggest that mindsets partially explain individual differences in behavioral outcomes.

To date there is little empirical evidence for the transferability of these results to issues of group-differences in social-emotional development. The complexity of social, emotional and behavioral difficulties may be the main reason for this (Désbien and Gagné Citation2007; Zimmermann Citation2018). One way mindsets might impact human behavior is through their close link to emotions. Social Information Processing Theory suggests that both concepts are strongly interconnected in their impact on social behavior (Dodge and Rabiner Citation2004; Huesmann Citation1988). In practice, this makes it very difficult to draw a conceptual line between them; instead, mindsets and emotions might be better understood as strongly overlapping. Previous research suggests that emotions have a very strong impact on behavioral outcomes (Lemerise and Arsenio Citation2000). Therefore, both concepts are fundamental to understanding social-emotional development and behavior.

Mindsets impact bullying behavior

Empirical evidence on mindsets impacting bullying behavior is scarce, but several studies have found significant links. The strongest evidence comes from a randomized controlled trial study showing that teaching students a personality-growth mindset – i.e. the belief that personality traits are not fixed but can be changed – reduces bullying behavior over time (Yeager and Dweck Citation2012). The authors of this intervention study posit that a belief in malleable personalities increases the willingness of victims to respond to bullying and other negative behaviors with prosocial strategies, which interrupts the cycle of violence and revenge common in high-bullying school climates. In fact, a significant share of victims of bullying are also bullying themselves and referred to as bully-victims. Such students might profit most from a personality-growth mindset intervention, because their aggression towards others tends to be reactive (Salmivalli and Nieminen Citation2002). Personality-growth mindset interventions theoretically reduce reactive aggression, but not necessarily active and strategic forms of violence.

The results of another study suggest that feelings of insecurity impact bullying (Dietrich and Ferguson Citation2019). Specifically, two types of feelings of insecurity – academic-status insecurity and (a global) self-esteem – have been shown to mediate the link between socioeconomic status and bullying, and the link between academic achievement and bullying. Based on these results, the authors postulate that bullying is a compensatory behavior for academically stigmatized students who worry that they look unintelligent in front of their peers.

Several studies have found that narcissism significantly predicts bullying behavior (e.g. Reijntjes et al. Citation2016; Fanti and Henrich Citation2015). Narcissism needs to be conceptually distinguished from self-esteem, which is a general sense of self-worth (Du, King, and Chi Citation2017). In contrast, narcissism is defined as a fragile belief in one’s own superiority and grandiosity, combined with a desire for other people’s praise, attention and admiration (Ang et al. Citation2009). When narcissists are unable to satisfy their needs through prosocial means they experience feelings of humiliation and anger, which can lead to aggression.

Lastly, empathy has been found to reduce bullying behavior and motivate students to help victims of bullying. (Davis Citation1994). Empathy has both cognitive and emotional components, which include the cognitive ability to understand other people’s emotional states and the emotional ability to feel what others feel. Quasi-experimental evaluation studies suggest that two intervention programs with the purpose of increasing feelings of empathy among students – the Roots of Empathy and B.A.S.E. Baby Watching programs – have successfully reduced bullying behavior among children and adolescents (MacDonald et al. Citationn.d.; Lionetti, Snelling, and Pluess Citation2017).

Mindsets and aggressive behavior

The body of research on the relationship between mindsets and aggression is considerably more comprehensive than that of research on the relationship between mindsets and bullying. Hence, the central question of this research paper is whether and to what extent aggression-related mindsets (i.e. mindsets that are believed to impact aggression) can explain bullying behavior. For many aggression-related mindsets there is theoretical reason to believe that this is indeed the case.

It is not hard to imagine that approval of aggression, i.e. the personal conviction that aggressive behavior is a legitimate way to solve problems and typically leads to positive outcomes (Ang et al. Citation2009), can encourage adolescents to bully their peers. Similarly, a hostile attribution bias (Crick and Dodge Citation1994), i.e. the belief and feeling that other people tend to have bad intentions, might also increase the tendency to bully, particularly among bully-victims. This belief is particularly common among adolescents who grow up in dangerous neighborhoods, where mistrust is important for survival (Cook et al. Citation2014). Even in safe environments, people with a hostile attribution bias tend to misinterpret ambiguous social situations and react aggressively in ways that can be interpreted as bullying.

Counterintuitively, a belief in a just world (BJW) can lead to aggression, and might also lead to bullying (Almeida, Correia, and Marinho Citation2009). BJW is the prevailing belief that humanity lives in a just world, in which good things only happen to good people and bad things only happen to bad people (Lerner Citation1980). This mindset generally motivates people to act ethically, but it also results in contempt and aggression towards less fortunate people, because they are assumed to deserve their adversity. As a result, people with a BJW mindset might blame victims of bullying for their misfortune and they may even support bullies, because they assume their bullying is justified.

Kokkinos et al. (Citation2014) introduce the idea that different types of efficacy-beliefs impact bullying behavior. Specifically, they theorize that the belief in one’s own ability to control difficult social situations through prosocial means lowers the incentive to use anti-social strategies, such as bullying. Similarly, Crick and Dodge (Citation1996) suggest that students who feel efficacious in bullying will more readily engage in such behavior. As already mentioned, the fact that lower academic achievement predicts more bullying behavior, which is explained by differences in academic-status insecurity (Dietrich and Ferguson Citation2019), suggests that stronger feelings of academic efficacy should predict less bullying.

A sense of purpose, which Damon, Menon, and Bronk (Citation2003) define as a ‘stable and generalized intention to accomplish something that is at once meaningful to the self and of consequence to the world beyond the self’ (p. 121), might reduce bullying. Having a purpose in life has been shown to predict a variety of positive outcomes, including better emotional well-being, physical health, longevity, and higher incomes (Zika and Chamberlain Citation1992; Scheier et al. Citation2006; Hill and Turiano Citation2014; Hill et al. Citation2016). It is therefore plausible that people with a sense of purpose are less likely to experience negative emotions, such as frustration and anger, which in turn lowers their tendency for aggressive behavior, including bullying. However, a sense of purpose can also lead to more aggression if violence is considered an important strategy to reach one’s central goals, such as in violent extremism (Griffin Citation2004).

Moral disengagement is a mental process to justify actions that conflict with one’s own moral and ethical beliefs (Bandura Citation1986). It includes ‘euphemistic labeling, and advantageous comparison; diffusion or displacement of personal responsibility; distortion of consequences; and blaming or dehumanization of victims’ (Almeida, Correia, and Marinho Citation2009). Moral disengagement is the belief that ethical standards do not apply to oneself, thereby removing moral and ethical barriers to act aggressively. It has been found to predict aggression (Rubio-Garay, Carrasco, and Amor Citation2016), and is a common strategy among bullies (Twemlow and Sacco Citation2011).

Feelings of anger and happiness towards someone or something are theorized to impact aggressive behavior as well. Unsurprisingly, anger has been found to be a strong and positive predictor of a wide range of aggressive behaviors including bullying (Sullivan et al. Citation2017; Wyckoff Citation2016; Rubio-Garay, Carrasco, and Amor Citation2016). In contrast, results from research on the impact of happiness on aggressive behavior are mixed. One study found that happiness correlates negatively with aggressive behavior (Ronen et al. Citation2013). Thus, the authors’ propose that happiness serves as a protective factor against aggressive feelings. Another study, which utilized functional magnetic resonance imaging to measure feelings of happiness, found that aggressive behavior increases feelings of happiness whenever a provocative act preceded an act of aggression (Chester and DeWall Citation2016). Therefore, happiness might be both, a protective factor against aggression and bullying, and an outcome of such behavior.

Purpose of study

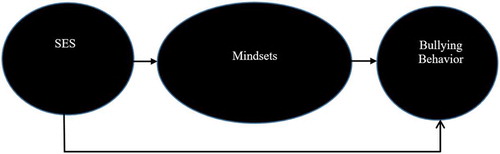

Based on previous evidence suggesting that mindsets can impact bullying behavior (Kokkinos et al. Citation2014; Damon, Menon, and Bronk Citation2003) and mediate the relationship between SES and bullying behavior among adolescents (Dietrich and Ferguson Citation2019), this study theorizes that aggression-related mindsets can explain SES-differences in bullying behavior. Hence, the study’s main hypothesis is the following: The relationship between students’ SES background and bullying behavior is partially mediated by aggression-related mindsets. shows the conceptual model of this hypothesis.

The main contributions of this study are (1) the provision of evidence for new potential predictors of adolescent bullying behavior and (2) new explanations why students from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds are more likely to engage in bullying.

Methods

Participants

This study uses de-identified survey data collected in middle and high schools in the United States by Tripod Education Partners, Inc. The Tripod survey’s main purpose is to evaluate teaching quality in classrooms, but it also gathers information on topics such as student behaviors, mindsets, and background characteristics. Surveys were conducted in public and charter schools in various school districts with students from grades five through twelve, thus providing a large and diverse sample (see ).

Table 1. Missing data.

Data are cross-sectional and from the academic years 2013–2015. They contain identifiers at the student-, classroom-, school-, and district-levels. Schools that conducted shorter versions of the Tripod survey were excluded from the sample due to a lack of essential survey items. The resulting dataset contains 146,044 students nested in 7,247 classrooms, 131 schools and 29 U.S. districts.

Procedures

Students in the analyses are those who attended school on the days the school administered the survey. In some cases, students who were absent completed the survey later. School personnel administered the survey school-wide during a designated period of the day and all responses were completely confidential. Those who responded on paper sealed the completed surveys in peal-and-stick envelopes before handing them in, while others responded online using personalized codes to log in.

Observed indices

The self-esteem index in the Tripod survey takes three items from the widely-used Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg Citation1965). An example item is ‘I feel like I am a person of worth, at least on an equal basis with others’. The index is measured on a five-point Likert scale ranging from ‘Never’ to ‘Always’. Its reliability and validity are well-established (Shorkey and Whiteman Citation1978; Rosenberg Citation1965; Silber and Tippett Citation1965), and it has a Cronbach’s alpha reliability of 0.79 in the present sample.

Feelings of academic efficacy is a three-item index and measures students’ beliefs that they will be academically successful. An example item is: ‘I’m certain I can master the skills taught in this class’. All items are measured on a five-point Likert scale ranging from ‘Never’ to ‘Always’. The index was drawn from the Patterns of Adaptive Learning Scales (Midgley et al. Citation2000), and has established validity and reliability (Midgley et al. Citation1998). Its Cronbach’s alpha reliability in the current sample is 0.80.

Sense of purpose is a single item index from the Tripod survey and reads ‘I have a clear purpose in my life – I know the types of things I want to achieve’. It is an original Tripod survey item.

Latent constructs

The bully outcome variable in this paper is a two-item index from the Tripod survey (‘Guide to Tripod’s 7Cs Framework’, 2016). It is measured on a five-point Likert scale ranging from ‘Totally True’ to ‘Totally Untrue’. The items read ‘Other students think I am a bully’ and ‘Some teachers seem afraid of me’. Construct validity will be confirmed via multilevel confirmatory factor analysis (ML-CFA). Because the construct is a measure of students’ self-perceived bully persona, not actual bullying behavior, this study conducts an additional criterion validity test. Specifically, it applies a simple regression analysis to evaluate whether the school-average of the bully index significantly predicts self-perceived victimization rates in schools (measured by a victimization index with two items reading ‘I get bullied at school’ and ‘Some of my friends get bullied at school’).

SES includes three items: the number of books at home, the highest educational level of a parent, and the number of computers at home. Books at home is a five-point Likert-scale item with five answer choices ranging from ‘0 to 10’ to ‘More than 250’. Parental Education is also a five-point Likert scale and reads, ‘Think of the adult at your home who went to school for the most years. This person: …’; it offers answer choices ranging from ‘Did not finish high school’ to ‘Finished a professional or graduate degree after college’. Computers at home is a four-point Likert scale item with answer choices ranging from ‘None’ to ‘Three or more’. Construct validity of SES will be evaluated via ML-CFA.

The academic-status insecurity index was created by Dietrich and Ferguson (Citation2019), and includes the following four items: ‘I worry about not looking smart’; ‘I worry that people think I am too serious about my schoolwork’; ‘I worry what other students think about me’; ‘In this class, I worry that I might not do as well as other students’. However, for this paper, the item ‘I feel out of place in this class, like I don’t really fit in’ replaces the item ‘I worry what other students think about me’, because the latter is no longer available in more recent Tripod data. ML-CFA will be used to confirm construct validity.

The measures for school-related happiness, which consist of ‘This class is a happy place for me to be’ and ‘This class feels like a happy family’, and those for school-related anger, which include ‘Being in this class makes me feel angry’ and ‘The way adults treat me at this school makes me angry’, are original Tripod survey items. ML-CFA will be applied to confirm the discreetness and construct validity of school-related anger and school-related happiness.

Analyses

To test the main hypotheses, the analyses use multilevel structural regression modeling (ML-SRM), which allows the development of complex multilevel path models, including observed measures and latent factors (Kline Citation2011). ML-CFA is used to test the construct validity of all latent factors, and all analyses are run on Mplus 8. To evaluate construct validity and model fit, this study reports χM2, SRMR, CFI, and RMSEA. Fit index cut-offs are based on the recommendations of Hu and Bentler (Citation1999) – i.e. <.08 for RMSEA and SRMR, and > .90 for CFI.

All endogenous variables of the models are tested for acceptable skewness (<2) and kurtosis (<7), which is a prerequisite for maximum likelihood estimation (Kline Citation2011), and the data are screened for Haywood cases and collinearity problems. ICCs indicate that for the bullying index there is significant variation at the classroom- and school-levels (6% and 4%, respectively). Hence, all models control for bias due to clustering via the multilevel modeling option of Mplus 8. For the analyses in this paper all items are treated as continuous.

Even though Preacher and Hayes (Citation2004) recommend bootstrapping to test the statistical significance of mediation effects, this study applies the more conservative normality approach because Mplus 8 does not support bootstrapping in combination with multi-level modeling. However, due to the large sample size, this shortcoming is negligible.

Alternative models with different pathways are compared to the initial model and the final model is chosen based on best fit statistics. In cases of comparable fit, preference is given to the most parsimonious model. displays the initial SEM-model. The SES-background of students predicts mindsets, i.e. sense of purpose, feelings of academic efficacy, self-esteem, academic-status insecurity, school-related anger, and school-related happiness. In turn, mindsets predict the bullying-outcome index.

Missing data

Most of the variables do not have more than 11% of values missing, with the exception of parental education, which has 45% missing data (see ). Multivariate regression analyses suggest that missing values are at random, thus, the analyses use Mplus 8’s full information maximum likelihood (FIML)-estimator.

Results

Construct validity

Bullying and socioeconomic status

For the calculation of model fit statistics CFAs need to be over-identified, which requires a minimum of four items. Hence, the bullying and SES constructs were evaluated together, with SES predicting bullying (see ). The ML-CFA model suggests adequate fit (χM2 = 81,165.159, RMSEA = .014, CFI = .999, SRMR = .012). All factor loadings are above 0.4 as recommended by Stevens (Citation1992): 0.649 for books at home, 0.580 for computers at home, and 0.658 for parental education on SES; 0.771 for bully and 0.660 for intimidation. Hence, the construct validity of SES and bullying are confirmed.

Similarly, the simple regression results support the criterion validity of the bullying index. The school-level bullying index (Cronbach’s alpha = .89) is a medium to large (r = .59 standard deviation, p < .001) predictor of the victimized index (Cronbach’s alpha = .94); overall model fit is R2 = .35.

Academic-status insecurity

The ML-CFA for academic-status insecurity (see ) suggests adequate fit (χM2 = 24,771.44, RMSEA = .051, CFI = .970, SRMR = .021). All factor loadings except one are above 0.4 as suggested by Stevens (Citation1992): 0.809 for ‘I worry about not looking smart’, 0.750 for ‘In this class, I worry that I might not do as well as other students’, 0.451 for I worry that people think I am too serious about my schoolwork”, and 0.368 for ‘I feel out of place in this class, like I don’t really fit in’. Overall, construct validity can be confirmed.

School-related anger and happiness

ML-CFA supports the partition of the four emotion-items into two discreet co-varying factors (see ): school-related happiness, and school-related anger. The model has acceptable fit (χM2 = 140,328.088, CFI = 1.000 and RMSEA = .021, SRMR = .005), and fits the data significantly better than a model that loads all four anger and happiness items on a single factor. Factor loadings were 0.841 for ‘Being in this class makes me feel angry’, 0.443 for ‘The way adults treat me at this school makes me angry’, 0.909 for ‘This class is a happy place for me to be’, and .698 for ‘This class feels like a happy family’, and therefore confirms the construct validity of school-related anger and school-related happiness as suggested by Stevens (Citation1992) (see ). The standardized correlation coefficient between the factors school-related happiness and school-related anger (r = −0.572) does not exceed the recommended cut-off of r = .90 suggested by Kline (Citation2011), which confirms discriminant validity.

The final ML-SRM

The initial ML-SR-model () does not have acceptable fit (χM2 = 526,624.907, RMSEA = .088, CFI = .802, SRMR = .088). In comparison, the fit of the final model () is acceptable (χM2 = 17,007.005, RMSEA = .035, CFI = .968, SRMR = .057).

The final model supports the hypothesis that mindsets mediate the path from SES to bullying behavior; in fact, model fit statistics suggest that the final model should omit a direct effect from SES to bullying. Feelings of academic efficacy is the only mindset/emotion directly predicted by SES (r = 0.25 standard deviation, p < .001). The total mediation effect from SES through academic efficacy (and all other mindset/emotion mediators) to bullying is −0.08 standard deviation (p < .001).

Academic efficacy predicts all other mindsets directly, with the strongest effect on school-related happiness (r = 0.47 standard deviation, p < .001), and the weakest on school-related anger (r = −0.09 standard deviation, p < .001). The total effect of academic efficacy on bullying is −0.32 standard deviation (p < .001).

School-related happiness (r = 0.53 standard deviation, p < .001) and school-related anger (r = 1.10 standard deviation, p < .001) are the strongest direct predictors of bullying. The positive path from school-related happiness to bullying is unexpected, because it suggests that more school-related happiness predicts more bullying, controlling for school-related anger, SES, and feeling of purpose. However, school-related happiness also predicts less school-related anger (−0.48 standard deviation, p < .001), which results in a total indirect effect of r = −0.53 standard deviation (p < .001) on bullying. The total (direct and indirect) effect of school-related happiness on bullying is not significant.

Neither self-esteem nor academic-status insecurity are direct predictors of bullying. Instead, the path from academic-status insecurity to bullying is entirely mediated by school-related anger, and the path from self-esteem to bullying is entirely mediated by school-related happiness, academic-status insecurity, and school-related anger. In other words, the paths from self-esteem to bullying and academic-status insecurity to bullying are entirely explained by school-related anger and happiness. The total effect of self-esteem on bullying is −0.13 standard deviation (p < .001), and the total effect of academic-status insecurity on bullying is 0.53 (p < .001).

Feelings of purpose predict bullying directly (−0.11 standard deviation, p < .001) and indirectly through self-esteem, academic-status insecurity, school-related happiness, and school-related anger (−0.04 standard deviation, p < .001), for a total effect of −0.15 standard deviation (p < .001).

Discussion

The results of the analyses support the main hypothesis: mindsets – including sense of purpose, feelings of academic efficacy, social status insecurity, self-esteem, school-related anger, and school-related happiness – explain the entire relationship between socioeconomic status and bullying behavior. Furthermore, they suggest that some mindsets, in particular school-related anger and school-related happiness, are much stronger predictors of bullying than others, which makes them more relevant for intervention purposes.

While school-related anger is a strong and positive predictor of bullying behavior, school-related happiness appears to have both positive and negative effects on bullying that cancel each other out. A total effect close to zero means that happy students bully as much (or as little) as unhappy students. Further research is required to explore this complex relationship. For example, it is possible that happier students are less likely to socialize and identify with victims of bullying, because victims tend to be much less happy. A lack of socialization and identification with victims of bullying might reduce feelings of empathy towards them, which in turn leads to more bullying behavior (Davis Citation1994).

Previous research has found that differences in academic-status insecurity and self-esteem explain bullying behavior among adolescents (Dietrich and Ferguson Citation2019). The current study results confirm this finding, however, it also suggests that the total effect of self-esteem on bullying is considerably smaller than the total effect of academic-status insecurity on bullying. This indicates that worrying about looking weak in front of others impacts adolescent bullying behavior more strongly than abstract feelings of self-worth.

The fact that the final model omits a direct path from SES to bullying implies that within-classroom differences in bullying between high- and low-SES students are entirely explained by the differences in bullying-related mindsets. This being said, the within-classroom difference in bullying behavior between high- and low-SES students is already small with approximately 0.1 standard deviation. Other studies might have found larger effects of SES on bullying, but these often do not distinguish within and between classroom effects. In fact, the relationship between SES and bullying in this study’s data (based on single-level simple regression analysis) is −0.45 standard deviation (p < .001, R2 = .20) when the distinction between within- or between-classroom effects are neglected. In other words, SES-differences in bullying behavior can be partially explained by the fact that low-SES and high-SES students tend to be found in different schools and classrooms. Future research needs to explore which factors might explain between-classroom and between-school differences in bullying, such as classroom and school climate effects.

Limitations

The strongest limitation of this study is its cross-sectional design, which prohibits hasty causal inferences. For example, school-related happiness negatively predicts bullying, but it is also possible that students who bully more feel happier as a result of their bullying. This being said, the directionality from SES to bullying can only be unidirectional, because it is highly unlikely that students’ socioeconomic status is somehow impacted by their bullying behavior at school; and the fact that mindsets mediate the entire relationship between both variables strongly suggests that what matters in terms of within-classroom bullying behavior is not socioeconomic status per se, but bullying-related mindsets that are more dominant among lower-SES students.

Second, the factors bullying, school-related anger and school-related happiness comprise of only two indicators each. Ideal are multi-item indices with three or more indicators (Kline Citation2011), which unfortunately are not available in the Tripod dataset. Nevertheless, strong results of the construct and criterion validity analyses build confidence in these constructs.

Third, even though the results suggest that mindsets are important mediators of the relationship between SES and bullying, they do not provide information on why lower-SES students have developed stronger bullying mindsets than higher-SES students. This question goes beyond the realms of this study. Bullying mindsets such as anger towards adults or peers fall within the definition of psycho-social difficulties, which are brought about by interactions of intrapsychic, interpersonal, and social conditions (Zimmermann Citation2018). Future research needs to explore interactions between these three dimensions in order to explain how SES-differences in bullying-related mindsets come about.

Implications

The results provide clues on what types of mindsets anti-bullying interventions should focus on in order to reduce adolescent bullying behavior. Specifically, interventions that reduce school-related anger might have the strongest impact on bullying behavior. In order to reduce school-related anger, schools could intervene with anger- and aggression-reducing group therapy programs, such as the highly successful Becoming a Man intervention program from Chicago (Cook et al. Citation2014). In addition, they can identify causes of students’ feelings of anger in school and try to eliminate them. For example, the results of this study suggest that poor relationships in school are among these causes, which means that professional development and other interventions need to focus on teachers’ and students’ social skills to establish and maintain respectful relationships. Other causes of students’ feelings of anger might be boredom in the classroom and confusion about learning material (Ferguson et al. Citation2015). Hence, professional training that improves teachers’ clarification skills might reduce bullying too.

Anti-bullying interventions are also well-advised to focus on reducing students’ fear of not looking smart in front of their peers. In comparison, attempts to increase students’ global self-esteem might be notably less effective. The results of this study also suggest that increasing students’ feelings of academic efficacy might be effective in simultaneously reducing academic-status insecurity and increasing global self-esteem. Practical strategies might include teaching students an academic growth mindset and providing them with additional support when they struggle academically (Dietrich and Ferguson Citation2019). The goal is to create a learning climate in which students focus on personal growth and effort, instead of ‘inert ability’.

Conclusion

Previous research suggests that mindsets influence adolescent bullying behavior, and that they might account for SES-differences in bullying as well. The results of this study confirm these hypotheses and suggest that aggression-related mindsets account for the entire relationship between SES and bullying behavior within classrooms. With regard to practical implications, the results suggest that anti-bullying interventions should focus on reducing students' feelings of school-related anger, in particular, by efforts that reduce academic-status insecurity and increase feelings of academic efficacy. Additional research is required to understand why lower-SES students are more likely to develop bullying-related mindsets, and to explore factors that explain between-classroom differences in bullying behavior.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support by the Open Access Publication Fund of Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Lars Dietrich

Lars Dietrich is a Research Associate at the Department of Rehabilitation Sciences at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. His research and teaching focus on adolescent bullying behavior, and social-emotional and academic development.

David Zimmermann

David Zimmermann is a Professor and head of the Psycho-Social Difficulties in Education Division at the Department of Rehabilitation Sciences at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. His research and teaching focus on SEBD, trauma, psychoanalysis in education, and teacher professional development.

References

- Akiba, M. 2010. “Bullies, Victims, and Teachers in Japanese Middle Schools.” Comparative Education Review 54 (3): 369–392. doi:10.1086/653142.

- Almeida, A., I. Correia, and S. Marinho. 2009. “Moral Disengagement, Normative Beliefs of Peer Group, and Attitudes regarding Roles in Bullying.” Journal of School Violence 9 (1): 23–36. doi:10.1080/15388220903185639.

- Ang, R. P., E. Y. L. Ong, J. C. Y. Lim, and E. W. Lim. 2009. “From Narcissistic Exploitativeness to Bullying Behavior: The Mediating Role of Approval-Of-Aggression Beliefs.” Social Development 19 (4): 721–735. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2009.00557.x.

- Bandura, A. 1986. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Barth, J. M., S. T. Dunlap, H. Dane, J. E. Lochman, and K. C. Wells. 2004. “Classroom Environment Influences on Aggression, Peer Relations, and Academic Focus.” Journal of School Psychology 42 (2): 115–133. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2003.11.004.

- Chester, D. S., and C. N. DeWall. 2016. “The Pleasure of Revenge: Retaliatory Aggression Arises from a Neural Imbalance toward Reward.” Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience 11 (7): 1173–1182. doi:10.1093/scan/nsv082.

- Cook, P. J., K. Dodge, G. Farkas, R. G. Fryer Jr, J. Guryan, J. Ludwig, and L. Steinberg (2014). “The (Surprising) Efficacy of Academic and Behavioral Intervention with Disadvantaged Youth: Results from a Randomized Experiment in Chicago (No. W19862).” https://static1.squarespace.com/static/543fe0e3e4b0f38ea7930575/t/544a7712e4b0ff95316c2287/1414166290135/Crime+Lab+pilot+study+paper_Match+Tutors+Chicago.pdf

- Crick, N. R., and K. A. Dodge. 1994. “A Review and Reformulation of Social Information-Processing Mechanisms in Children’s Social Adjustment.” Psychological Bulletin 115 (1): 74–101. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.115.1.74.

- Crick, N. R., and K. A. Dodge. 1996. “Social Information-Processing Mechanisms in Reactive and Proactive Aggression.” Child Development 67 (3): 993–1002. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01778.x.

- Crosnoe, R. 2011. Fitting In, Standing Out. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Damon, W., J. Menon, and K. C. Bronk. 2003. “The Development of Purpose during Adolescence.” Applied Developmental Science 7 (3): 119–128. doi:10.1207/S1532480XADS0703_2.

- Davis, M. H. 1994. Empathy: A Social Psychological Approach. Madison, WI: Brown & Benchmark.

- Désbien, N., and M.-H. Gagné. 2007. “Profiles in the Development of Behavior Disorders among Youth with Family Maltreatment Histories.” Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties 12 (3): 215–240. doi:10.1080/13632750701489964.

- Dietrich, L., and R. F. Ferguson. 2019. Why Stigmatized Adolescents Bully More: The Role of Self-Esteem and Academic-Status Insecurity. [ Manuscript submitted for publication].

- Dodge, K. A., and D. L. Rabiner. 2004. “Returning to the Roots: On Social Information Processing and Moral Development.” Child Development 75 (4): 1003–1008. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00721.x.

- Du, H., R. B. King, and P. Chi. 2017. “Self-Esteem and Subjective Well-Being Revisited: The Roles of Personal, Relational, and Collective Self-Esteem.” PloS one 12 (8). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0183958.

- Fanti, K. A., and C. C. Henrich. 2015. “Effects of Self-Esteem and Narcissism on Bullying and Victimization during Early Adolescence.” Journal of Early Adolescence 35 (1): 5–29. doi:10.1177/0272431613519498.

- Ferguson, R. F., S. F. Phillips, J. F. S. Rowley, and J. W. Friedlander (2015). “The Influence of Teaching - beyond Standardized Test Scores: Engagement, Mindsets, and Agency - A Study of 16,000 Sixth through Ninth Grade Classrooms.” Cambridge, MA: http://www.agi.harvard.edu/projects/TeachingandAgency.pdf

- Fisher, S., K. Middleton, E. Ricks, C. Malone, C. Briggs, and J. Barnes. 2015. “Not Just Black and White: Peer Victimization and the Intersectionality of School Diversity and Race.” Journal of Youth Adolescence 44 (6): 1241–1250. doi:10.1007/s10964-014-0243-3.

- Goldbaum, S. 2007. “Developmental Trajectories of Victimization: Identifying Risk and Protective Factors.” In Bullying, Victimization, and Peer Harassment: A Handbook of Prevention and Intervention, edited by C. A. Maher, 143. Florence, KY: Routledge.

- Graham, S., and J. Juvonen. 2002. “Ethnicity, Peer Harassment, and Adjustment in Middle School: An Exploratory Study.” Journal of Early Adolescence 22 (2): 173–199. doi:10.1177/0272431602022002003.

- Griffin, R. 2004. “Introduction: God’s Counterfeiters? Investigating the Triad of Fascism, Totalitarianism and (Political) Religion.” Totalitarian Movements & Political Religions 5 (3): 291–325. doi:10.1080/1469076042000312168.

- Hill, P. L., and N. A. Turiano. 2014. “Purpose in Life as a Predictor of Mortality across Adulthood.” Psychological Science 25 (7): 1482–1486. doi:10.1177/0956797614531799.

- Hill, P. L., N. A. Turiano, D. K. Mroczek, and A. L. Burrow. 2016. “The Value of a Purposeful Life: Sense of Purpose Predicts Greater Income and Net Worth.” Journal of Research in Personality 65: 38–42. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2016.07.003.

- Hu, L.-T., and P. M. Bentler. 1999. “Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indices in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives.” Structural Equation Modeling 6 (1): 1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118.

- Huesmann, L. R. 1988. “An Information Processing Model for the Development of Aggression.” Aggressive Behavior 14 (1): 13–24. doi:10.1002/1098-2337(1988)14:1<13::AID-AB2480140104>3.0.CO;2-J.

- Hyman, I. 2006. “Bullying: Theory, Research, and Interventions.” In Handbook of Classroom Management: Research, Practice, and Contemporary Issues, edited by E. Emmer, 855–884. Florence, KY: Routledge.

- Jones, S. 2016. H306 – Beyond Grit: Non‐Cognitive Factors in School Success. Cambridge, MA: Course Syllabus. Harvard Graduate School of Education.

- Kline, R. B. 2011. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling: Third Edition. New York, NY: Guileford Press.

- Kokkinos, C. M., P. Panagopoulou, I. Tsolakidou, and E. Tzeliou. 2014. “Coping with Bullying and Victimisation among Preadolescents: The Moderating Effects of Selfefficacy.” Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties 20 (2): 205–222. doi:10.1080/13632752.2014.955677.

- Lee, C.-H. 2012. “Functions of Parental Involvement and Effects of School Climate on Bullying Behaviors among South Korean Middle School Students.” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 27 (12): 2437. doi:10.1177/0886260511433508.

- Lemerise, E. A., and W. F. Arsenio. 2000. “An Integrated Model of Emotion Processes and Cognition in Social Information Processing.” Child Development 71 (1): 107–118. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00124.

- Lerner, M. J. 1980. The Belief in A Just World: A Fundamental Delusion. New York, NY: Plenum Publishing.

- Lionetti, F., S. Snelling, and M. Pluess (2017). “Babywatching Study – Full Report”. London, UK. http://www.base-babywatching-uk.org/download/38ee34b8-0968-11e7-8ab0-9f9d61ca85d1/

- MacDonald, A., M. McLafferty, P. Bell, L. McCorkell, I. Walker, V. Smith, and A. Balfour (n.d.). “Evaluation of the Roots of Empathy Programme by North Lanarkshire Psychological Service.” https://www.actionforchildren.org.uk/media/3262/roots_of_empathy_report.pdf

- Mah, R. 2009. Getting beyond Bullying and Exclusion PreK-5: Empowering Children in Inclusive Classrooms. New York, NY: Skyhorse Publishing.

- Midgley, C., A. Kaplan, M. Middleton, M. L. Maehr, T. Urdan, L. H. Anderman, … R. Roeser. 1998. “The Development and Validation of Scales Assessing Students’ Achievement Goal Orientations.” Contemporary Educational Psychology 23 (2): 113–131. doi:10.1006/ceps.1998.0965.

- Midgley, C., M. L. Maehr, L. Hicks, R. Roeser, K. E. Freeman T. Urdan, E. Anderman, et al. 2000. Manual for the Patterns of Adaptive Learning Survey (PALS). Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan.

- Musu-Gillette, L., R. Hansen, K. Chandler, and T. Snyder (2015). “Measuring Student Safety: Bullying Rates at School.” https://nces.ed.gov/blogs/nces/post/measuring-student-safety-bullying-rates-at-school

- Olweus, D. 1993. “Victimization by Peers: Antecedents and Long-Term Outcomes.” In Social Withdrawal, Inhibition, and Shyness in Childhood, edited by K. H. Rubin and J. B. Asendorpf, 315. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

- Pepler, D., D. Jiang, W. Craig, and J. Connolly. 2008. “Developmental Trajectories of Bullying and Associated Factors.” Child Development 75 (2): 325–338. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01128.x.

- Ponzo, M. 2013. “Does Bullying Reduce Educational Achievement? an Evaluation Using Matching Estimators.” Journal of Policy Modeling 35 (6): 1057. doi:10.1016/j.jpolmod.2013.06.002.

- Preacher, K. J., and A. F. Hayes. 2004. “SPSS and SAS Procedures for Estimating Indirect Effects in Simple Mediation Models.” Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers 36 (4): 717–731. doi:10.3758/BF03206553.

- Reijntjes, A., M. M. Vermande, S. Thomaes, F. A. Goossens, T. Olthof, L. Aleva, and M. Van der Meulen. 2016. “Narcissism, Bullying, and Social Dominance in Youth: A Longitudinal Analysis.” Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 44 (1): 63–74. doi:10.1007/s10802-015-9974-1.

- Rigby, K., and P. T. Slee. 1993. “Dimensions of Interpersonal Relation among Australian Children and Implications for Psychological Well-Being.” The Journal of Social Psychology 133 (1): 33. doi:10.1080/00224545.1993.9712116.

- Ronen, T., I. Abuelaish, M. Rosenbaum, Q. Agbaria, and L. Hamama. 2013. “Predictors of Aggression among Palestinians in Israel and Gaza: Happiness, Need to Belong, and Self-Control.” Children and Youth Services Review 35 (1): 47–55. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.10.015.

- Rosenberg, M. 1965. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Ross, D. 1996. Childhood Bullying and Teasing: What School Personnel, Other Professionals, and Parents Can Do. Alexandria, VA: Amer Counseling Assn.

- Rubio-Garay, F., M. A. Carrasco, and P. J. Amor. 2016. “Aggression, Anger and Hostility: Evaluation of Moral Disengagement as a Mediational Process.” Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 57 (2): 129–135. doi:10.1111/sjop.12270.

- Salmivalli, C., and E. Nieminen. 2002. “Proactive and Reactive Aggression among School Bullies, Victims, and Bully-Victims.” Aggressive Behavior 28 (1): 30–44. doi:10.1002/ab.90004.

- Scheier, M. F., C. Wrosch, A. Baum, S. Cohen, L. M. Martire, K. A. Matthews, and B. Zdaniuk. 2006. “The Life Engagement Test: Assessing Purpose in Life.” Journal of Behavioral Medicine 29 (3): 291–298. doi:10.1007/s10865-005-9044-1.

- Schumann, L. 2013. “Minority in the Majority: Community Ethnicity as a Context for Racial Bullying and Victimization.” Journal of Community Psychology 41 (8): 959. doi:10.1002/jcop.21585.

- Shaw, T. 2012. “The Clustering of Bullying and Cyberbullying Behaviour within Australian Schools.” Australian Journal of Education 56 (2): 142. doi:10.1177/000494411205600204.

- Shorkey, C. T., and V. Whiteman. 1978. The Rational Behavior Inventory: Initial Validity and Reliability. Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Service.

- Silber, E., and J. S. Tippett. 1965. “Self-Esteem: Clinical Assessment and Measurement Validation.” Psychological Reports 16 (3): 1017–1071. doi:10.2466/pr0.1965.16.3c.1017.

- Stevens, J. 1992. Applied Multivariate Statistics for The Social Sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Earlbaum.

- Strøm, I. 2013. “Violence, Bullying and Academic Achievement: A Study of 15-Year-Old Adolescents and Their School Environment.” Child Abuse & Neglect 37 (4): 243. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.10.010.

- Sullivan, T. N., R. C. Garthe, E. A. Goncy, M. M. Carlson, and K. L. Behrhorst. 2017. “Longitudinal Relations between Beliefs Supporting Aggression, Anger Regulation, and Dating Aggression among Early Adolescents.” Journal of Youth Adolescence 46 (5): 982–994. doi:10.1007/s10964-016-0569-0.

- Twemlow, S. W., and F. C. Sacco. 2011. Preventing Bullying and School Violence. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association Publishing.

- Wolke, D. 2001. “Bullying and Victimization of Primary School Children in England and Germany: Prevalence and School Factors.” British Journal of Psychology 92 (4): 673. doi:10.1348/000712601162419.

- Wyckoff, J. P. 2016. “Aggression and Emotion: Anger, Not General Negative Affect, Predicts Desire to Aggress.” Personality and Individual Differences 101: 220–226. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2016.06.001.

- Yeager, D. S., C. J. Fong, H. Y. Lee, and D. L. Espelage. 2015. “Declines in Efficacy of Anti-Bullying Programs among Older Adolescents: Theory and a Three-Level Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 37 (1): 36–51. doi:10.1016/j.appdev.2014.11.005.

- Yeager, D. S., and C. S. Dweck. 2012. “Mindsets That Promote Resilience: When Students Believe That Personal Characteristics Can Be Developed.” Educational Psychologist 47 (4): 302–314. doi:10.1080/00461520.2012.722805.

- Yeager, D. S., D. Paunesku, G. M. Walton, and C. S. Dweck (2013). “How Can We Instill Productive Mindsets at Scale? A Review of the Evidence and an Initial R&D Agenda.” A white paper prepared for the White House meeting on “Excellence in Education: The Importance of Academic Mindsets”, Washington, DC.

- Yeager, D. S., and G. M. Walton. 2011. “Social-Psychological Onterventions in Education: They’re Not Magic.” Review of Educational Research 81 (2): 267–301. doi:10.3102/0034654311405999.

- Yeager, D. S., K. Trzesniewski, and C. S. Dweck. 2013. “An Implicit Theories Of Personality Intervention Reduces Adolescent Aggression in Response to Victimization and Exclusion.” Child Development 84 (3): 970–988. doi: 10.1111/cdev.2013.84.issue-3.

- Zika, S., and K. Chamberlain. 1992. “On the Relation between Meaning in Life and Psychological Well-Being.” British Journal of Psychology 83 (1): 133–145. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8295.1992.tb02429.x.

- Zimmermann, D. 2018. “Pädagogische Konzeptualisierungen für die Arbeit mit sehr schwer belasteten Kindern und Jugendlichen.” Vierteljahreszeitschrift für Heilpädagogik und ihre Nachbargebiete 87 (4): 305–317. doi:10.2378/vhn2018.art35d.