ABSTRACT

The ELSA intervention was designed to build schools’ capacity to support pupils’ emotional wellbeing needs from within their own resources. A wide-ranging research base spanning over 10 years has grown around the ELSA intervention. This scoping review was commissioned by the ELSA Network to systematically identify and map the current composition of the ELSA research body, including the purpose, methods and range of research available. Guided by Arksey and O’Malley’s five-stage framework, 53 studies met the inclusion criteria and were reviewed; including 9 published studies, 31 doctoral or student studies and 14 local authority evaluation reports. When used alongside practice-based evidence, findings provide a basis to inform practitioners’ selection and use of intervention. Mapping of ELSA research indicates a tendency towards qualitative approaches, perhaps reflective of challenges measuring an adaptive intervention. Through identifying gaps related to topics, designs and participant voices, recommendations for future research are suggested.

Introduction

The ELSA intervention was designed to build the capacity of schools to support children and young people’s (CYP’s) emotional wellbeing needs from within their own resources (Burton Citation2008). Teaching assistants (TAs) become Emotional Literacy Support Assistants (ELSAs) by attending a five or six day course, delivered by ELSA-trained Educational Psychologists (EPs), before registering with their local Educational Psychology Service to access twice termly professional supervision. Though not a protected title in law, the title of ‘ELSA’ is only endorsed by the ELSA network where TAs access this continual programme (ELSA network Citation2020). Training and supervision aims to support ELSAs to develop psychological knowledge, whilst facilitating practical and relational skills in a variety of areas, including: emotional awareness and regulation, self-esteem, resilience, social communication skills, friendship skills and bereavement (Shotton and Burton Citation2018). Rather than following a set curriculum, ELSAs develop and deliver individualised interventions to meet the emotional needs of CYP in their care. Within their interventions, ELSAs aim to create three therapeutic conditions (empathy, congruence and unconditional positive regard) to foster emotional literacy skills within a supportive relationship (Burton and Okai Citation2018). The intervention is now widely implemented by local authorities across Britain (ELSA Network Citation2020).

A research base spanning over 10 years has grown around the ELSA intervention, and supports a general view of a positive impact (e.g. Atkin Citation2019, Balampanidou Citation2019, Barker Citation2017, Blackwell, and Claridge Citation2020, Harris Citation2020, Krause, Osborne and Burton Citation2014, Leighton Citation2015, Miles Citation2015, Wilding and Claridge Citation2016, Wong et al. Citation2020), with reported increases in ELSA’s self-efficacy, trait-emotional intelligence, their understanding of CYP’s emotions, and their confidence planning and delivering programmes and discussing needs with colleagues and parents (Dodds, Blake, and Garland Citation2015, Leighton Citation2015, Rees Citation2016). ELSAs also report that supervision has given them the opportunity to access emotional support and explore and improve their skills, knowledge and understanding around casework, and helped the majority feel better able to support pupils (Osborne and Burton Citation2014, France and Billington Citation2020, Ridley Citation2017). Miles (Citation2015) compared the ELSA-pupil relationship to the relationship between therapists and clients, with successful ELSAs demonstrating empathy, respect for children as individuals, listening skills and solution-focused approaches. Alongside relational support, ELSA research has found pupils also value the taught element of interventions, which enables them to develop strategies for use outside of the intervention and beyond the therapeutic relationship (Balampanidou Citation2019, Krause, Blackwell, and Claridge Citation2020, Purcell, Kelly, and Woods Citation2023, Purcell and Kelly Citation2023, Wong et al. Citation2020). CYP and staff perceive the supportive and collaborative relationship established in the ELSA intervention to create positive change, impacting multiple aspects of pupil wellbeing, including managing feelings and relationships (Hill, O’Hare, and Weidberg Citation2013, Krause, Blackwell, and Claridge Citation2020, Wong et al. Citation2020).

Rationale and aim

Research exploring and evaluating the ELSA intervention covers wide-ranging topics and has been conducted from varied perspectives, including by those who developed and/or implemented the intervention, and by trainee EPs or other students (e.g. Osborne and Burton Citation2014, Leighton Citation2015, Purcell, Kelly, and Woods Citation2023). The body of research grew organically as the use of the intervention developed (Rogers Citation2022). The current study was commissioned by the ELSA Network via the University of Manchester’s Doctorate in Educational and Child Psychology research commissioning model. ELSA Network research priorities have previously been explored (Rogers Citation2022). This scoping review was then commissioned to systematically identify, organise and map ELSA’s emerging body of literature, supporting practitioners to navigate and use the body of research to inform practice (Peters et al. Citation2015, Tricco et al. Citation2016). The review also aims to provide a clear overview of existing research in order to further identify research gaps in the field.

Methodology

Arksey and O’Malley’s (Citation2005) five-stage framework guided the review, along with recommendations by Levac, Colquhoun and O’Brien (Citation2010). Scoping reviews form an iterative process, meaning the stages below were revised and overlapping throughout (Levac, Colquhoun and O’Brien Citation2010). As scoping reviews aim to provide an overview of the existing research base irrespective of quality, methodological quality was not assessed (Peters et al. Citation2015).

Stage one: identify the research question

The following research questions (RQs) were generated iteratively and reviewed with the commissioners:

RQ1: What is the composition of the current body of ELSA research?

RQ2: How can the body of ELSA research inform practitioners use of ELSA?

RQ3: What are the research gaps in the field?

Stage two and three: identify relevant studies and study selection

Between July 2022 and May 2023 literature searches were carried out using the following databases: Web of Science, OVID: Psych Info, Education Resources Information Centre, British Education Index, Google Scholar, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global, and EThOS: E-Theses Online Service. The key search terms were ‘emotional literacy support assistant’ and ‘ELSA’. For some databases ‘ELSA’ was not an effective search term, due to producing a vast amount of irrelevant results. All results were screened when using the term ‘emotional literacy support assistant’ and sample of 200 titles of ‘ELSA’ results were screened. Screening suggested that all relevant results were captured by the ‘emotional literacy support assistant’ search term. Reference harvesting and Google Scholar citation checks were carried out for all relevant studies. The ‘Research’ and ‘Evaluation Reports’ areas of the ELSA Network website were also searched. Following searches, the author consulted with the ELSA Network Steering Group and ELSA Network members, who provided additional studies which had not been found through databases (Arksey and O’Malley Citation2005).

An adapted Preferred Reporting Items for Systemic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA; Moher et al. Citation2009) framework was used to identify relevant papers (see ). The literature search was not limited by country or date, but was limited to studies written in English. Six hundred and thirty-six papers were initially sourced, of which 550 were excluded after removing duplicates and screening titles and/or abstracts for relevance. All remaining 86 papers were from the UK. Five papers were excluded due to the author being unable to access them upon request. Eighty-one full texts were therefore screened by the first author and inclusion criteria was iteratively developed (see ). Regular discussion took place between the authors around the appropriateness of the studies in relation to the scope and purpose of the review, and eight papers were read and discussed fully to ensure inter-rater agreement. Twenty-eight papers were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria, leaving 53 to be included in the review.

Figure 1. Adapted PRISMA (Moher et al. Citation2009) flow diagram.

Figure 2. Inclusion criteria flow diagramFootnote1.

Stage four: charting the data

The following information was extracted from the included papers and recorded in a charting table:

The type of literature (e.g. published articles, doctoral theses, local authority evaluation reports)

The epistemological approach

The purpose of the paper (including any stated aims or research questions)

The methods and research design used

The participants included

The main topics covered (e.g. the intervention, training, supervision)

How it met the inclusion criteria

Stage five: collating, summarising and reporting results

Individual studies were analysed to identify key issues and themes relevant to the research questions. Viewing the data within the charting table allowed the author to consider comparisons and patterns across the literature. An iterative process of sorting and grouping the literature was carried out and research question one was further broken down into three sub-questions which further examine the approaches taken to the exploration and evaluation of the ELSA intervention:

RQ1a: Whose views have been sought about their own and others’ outcomes/experiences of ELSA?

RQ1b: What topics have been explored with participants?

RQ1c: What research designs have been used?

map the composition of ELSA research and the approaches taken to evaluate and explore the intervention. Frequent discussion and review of groupings were carried out and criteria were iteratively developed to clarify decisions and ensure consistency, with five papers read and discussed fully to ensure inter-rater agreement. For and participant lists were used to categorise those who had taken part in the studies. Interview or focus group schedules and questionnaires were used to ascertain studies’ main topics and to understand whose experiences or outcomes participants were asked to describe. Where copies of schedules or questionnaires were unavailable, the author extracted this information from reading the study’s aims, methods and findings. Within and studies could be included in more than one box when meeting the criteria for multiple categories. For example, Bravery and Harris (Citation2009) included both ELSAs and school staff as participants (see ), with both groups asked to describe their own experiences of the ELSA intervention, as well as the wider school and contextual implementation (see ).

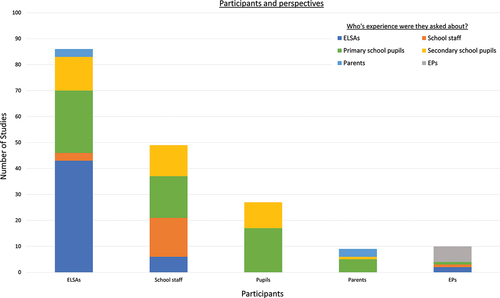

Table 1. Participants and perspectives. Numbers in brackets indicate the number of studies included within each cell and numbers in the final row indicate the total number of studies within each column.

Table 2. Participants and topics.

Table 3. Purpose and design.

Studies were grouped according to their primary aim and design (see ). Where a clear description of aims was not provided the author considered the methods and findings sections to ascertain the primary area of focus and the main approach used. Aims to explore experiences and/or evaluate impact were considered in relation to all stages and aspects of the ELSA programme, including training, supervision and the intervention itself. In terms of study designs, the University of Manchester Educational Psychology Critical Appraisal Review Frameworks (Woods Citation2020a, Citation2020b) were used to establish a criteria to categorise as ‘mainly evaluative’ or ‘mainly exploratory’ designs, which were also grouped into quantitative, qualitative and mixed methodologies. In order to be ‘mainly evaluative’ studies needed to include an element of comparison, for example pre and post measures or questions used to assess change following the intervention. ‘mainly exploratory’ studies were those focused on exploring meaning, concepts and experiences. Though some studies included both evaluative and exploratory approaches, the table represents their main design according to this criteria.

Member-checking was carried out with the ELSA Network Steering Group to evaluate ways of analysing the literature, with presented and discussed. Recommendations for future research were collaboratively identified from the presented body of literature.

Findings

The 53 included papers were made up of 9 published research studies, 30 doctoral or student studies and 14 evaluation reports produced by local authorities. refer to RQ1a, RQ1b, RQ1c.

: Participants and perspectives

RQ1a: Whose views have been sought about their own and others’ outcomes/experiences of ELSA?

and visually map the groups of participants included in ELSA research and summarise whose experiences these participants were asked about. Unsurprisingly, most participants were asked about their own experiences of the ELSA intervention. The majority of studies (45 of 53) included ELSAs as participants, with 43 asking about the ELSA’s own experiences. ELSAs were also asked about the experiences of primary school pupils in 24 studies and about the experiences of secondary school pupils in 13 studies. This included being asked what they perceived to be the impact of the intervention on pupils or how they perceived pupils to have experienced the intervention. School staff, parents and EPs were also asked about pupils’ experiences in 19 studies. 17 studies asked primary school pupils about their own experiences and 10 asked secondary school pupils. Parent and EP voices were least sought, with only five studies including parents and six including EPs.

: Participants and topics

RQ1b: What topics have been explored with participants?

summarises the main topics that different groups of participants were asked about within ELSA research. ELSA research spans a wide range of topics, including the intervention’s relationship with the wider school and its contextual implementation, and various perspectives on the experience and impact of the intervention, training and supervision. Much diversity exists within these overarching topics, including: exploration of the ELSA-pupil relationship (Ball Citation2014, Miles Citation2015, Peters Citation2020, Russo Citation2022, Wong et al. Citation2020), ELSA and self-efficacy (Grahamslaw Citation2010, Rees Citation2016), ELSA’s use of storytelling (Harris Citation2020), ELSAs working with children who have experienced Domestic Abuse (Eldred Citation2021) and the ELSA intervention during and post the COVID-19 pandemic (Endersby Citation2021, Russo Citation2022).

In terms of the relationship between participants and topics, ELSAs, school staff and EPs have been asked about all four topics, though to varying degrees. Aside from EPs who were most often asked about ELSA supervision, all participant groups have most often been asked about the intervention itself. However, a significant number of studies also asked ELSAs about training (16 studies), supervision (15 studies) and the wider school and contextual implementation (14 studies). Unsurprisingly, pupils and parents have not been asked about ELSA training and supervision and only two studies asked school staff about these topics. Though nine studies asked school staff about the wider school and contextual implementation, pupils have only been asked about the topic in one study and EPs in two studies, with parental voices missing on the topic.

Studies covered the topic of ‘the wider school and contextual implementation’ within to varying extents. Though 19 studies included the topic, this was often related to exploring facilitators and barriers to perceived impact. The topic was sometimes covered through single questions within questionnaires or interviews (e.g. Atkin Citation2019, Bowerman and Davies Citation2018, Endersby Citation2021, Osborne and Burton Citation2014) and was considered to be the primary focus of five studies (Dodds, Blake, and Garland Citation2015, Fairall Citation2020, Leighton Citation2015, Nicholson-Roberts Citation2019, Robertson Citation2021).

: Purpose and design

RQ1c: What research designs have been used?

presents the approaches that have been taken to researching ELSA. Overall, 17 studies primarily aimed to explore experiences, 12 aimed to evaluate impact and 24 set out to do both. In total, 23 studies adopted a qualitative approach, 29 adopted a mixed-methods approach and 1 adopted a quantitative approach. Of the 29 mixed-methods studies, 9 used only bespoke questionnaires, which included open and closed questions and rating scales. Nine used bespoke questionnaires or scales alongside interviews and/or focus groups. Three studies used other forms of data alongside interviews or surveys, including Q-sorts (Atkin Citation2019), observations (Butcher, Cook, and Holder-Spriggs Citation2013) and service-level reports (Thomas Citation2022). Eight studies employed standardised measurement tools (see appendix A; supplementary materials) alongside bespoke questionnaires or scales, interviews and/or focus groups. One quantitative study used only standardised measurement tools.

For most studies, exploratory or evaluative aims were matched to designs. It is noted that most published research took an exploratory approach (six of nine studies), with most using qualitative designs (six of nine). Most doctoral or student studies primarily aimed to explore experiences (14 of 30) or both explore experiences and evaluate impact (13 of 30), with 3 (of 30) aiming to evaluate impact. Unsurprisingly, most doctoral or student studies (20 of 30) therefore used mainly exploratory designs, with 10 employing mainly evaluative designs. By contrast, one local authority evaluation report primarily aimed to explore experiences, with eight aiming to evaluate impact and five aiming to do both. As a result, 2 evaluation reports used a mainly exploratory design, with 12 using a mainly evaluative design.

Discussion

This scoping review aims to understand the current composition of the ELSA research body through identifying the purpose, methods and range of research available (Peters et al. Citation2015). Findings from the visual mapping of the ELSA research base will be discussed in relation to the scoping review’s aims of orientating practitioners to the research informing ELSA practice, whilst also systematically identifying research gaps.

The composition of the current body of ELSA research

There is a tendency towards qualitative approaches within the current ELSA research body, with 52 of 53 studies employing some form of qualitative methodology within their designs. Most studies (29 of 53) adopted mixed-methods designs, and these tended to include more qualitative approaches than quantitative. Only one study adopted a fully quantitative approach. Further quantitative studies would have been expected to use a ‘mainly evaluative’ design, with the primary aim of evaluating impact, representing a gap in the literature. A pattern was identified in the purpose and corresponding designs of different types of ELSA studies; most local authority evaluation reports focused more on employing mixed methods, mainly evaluative designs to evaluate impact, or both explore experiences and evaluate impact, whereas most doctoral theses, student studies and published research tended to use more qualitative, mainly exploratory designs to explore experiences or both evaluate impact and explore experiences.

A significant amount of studies (41 of 53) aimed to explore experiences of the ELSA process, using qualitative approaches to gain insights into the perspectives of stakeholders. Where studies also aimed to evaluate impact alongside exploring experiences (24 of 41), they often used specific questions within semi-structured interviews, questionnaires or focus groups to understand how participants perceived change as a result of the intervention, training or supervision. Some evaluative interview questions were guided by scaling (Leighton Citation2015) or frameworks, for example Krause, Blackwell and Claridge (Citation2020) applied the wellbeing components of the Seligman’s (Citation2011) New Economics Foundation (NEF) and Positive Emotions, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning and Accomplishment (PERMA) model. Reflective journals and diaries were also used to gain insight around experiences of change as a result of ELSA (Leighton Citation2015, Peters Citation2020).

Where standardised measurement tools were used (nine studies; see appendix A; supplementary materials), they were usually triangulated with qualitative data (eight of nine studies). Individual targets, goal-based outcomes and curriculum data were also used as bespoke measures of progress. Regarding implementation and evaluation of interventions, Fox (Citation2011) and O’Hare (Citation2015) highlight the value of triangulating wide sources of practice-based evidence in this way, which may include practitioner experiences, service-user perceptions, contextual information and both efficacy and effectiveness research. Additionally, Pickering et al. (Citation2019) highlight the challenge of using measurement tools to evaluate the impact of the ELSA programme due to its adaptability. Though a core curriculum and standards around training and supervision exist, the ELSA Network accepts the need for training content to be flexible to reflect the needs of diverse contexts (ELSA Network Citation2023b). ELSAs are also supported to deliver bespoke sessions tailored to individual needs within real-world context (Burton and Okai Citation2018). It is therefore difficult to separate variables both within and outside of the intervention to ascertain a measurable impact, a challenge which is reflected in the current composition of the research body. Purcell and Kelly (Citation2023) highlight the need for measures sensitive enough to capture the nuanced and potentially incremental progress of CYP taking part in ELSA. Such measures also need to reflect ‘intended and valued outcomes’, tailored to individual CYP, as well as being appropriate for use in real-world school settings (Purcell and Kelly Citation2023, 214). Though the findings of the current study demonstrate a research gap around evaluative studies using quantitative designs, there is a need for methodologies not only to be robust, but also sensitive and relevant to the adaptable nature of the ELSA intervention within real-world context (Barkham and Mellor-Clark Citation2003).

In terms of participant perspectives, though 22 papers included CYP, the extent to which their voices have been heard within studies varies. Sixteen studies used interviews to gain an in-depth understanding of CYP’s views, sometimes supported by visual tools such as rating scales (Krause, Blackwell, and Claridge Citation2020), a Diamond Nine ranking resource (Purcell, Kelly, and Woods Citation2023) and drawing activities (Hills Citation2016, Krause, Blackwell, and Claridge Citation2020, McEwan Citation2019, Peters Citation2020, Wong et al. Citation2020). Five studies used bespoke questionnaires, one used a focus group and one used diaries kept by CYP. Three studies gained CYP’s perspectives exclusively through standardised pupil-rated measurement tools, whereas three used measurement tools alongside other forms of data, including interviews or questionnaires. Additionally, two papers stated that CYP were involved in their studies, though this constituted school staff and parents completing measures about CYP. The extent to which pupil voices were heard tended to be linked to the purpose and design of studies, with studies using exploratory approaches to gain insight into experiences more likely to gather pupil voice than those using evaluative approaches to assess impact. The importance of CYP having the opportunity to express their views on matters which directly affect them is reflected in legislation, including The Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND) Code of Practice (DfE Department for Education and DoH Department of Health Citation2014) and Article 12 of the Conventions on the Rights of the Child (UNICEF Citation2010). Numerous ELSA researchers have recognised this need, with Hill, O’Hare and Weidberg (Citation2013) recommending that CYP are included as co-researchers and Pickering et al. (Citation2019) and Purcell, Kelly and Woods (Citation2023) highlighting the need to understand what CYP themselves value about ELSA interventions when aiming to evaluate impact.

How the body of ELSA research can inform practitioners use of ELSA

As part of the process of using evidence-based practice when implementing interventions within schools, it is important for practitioners to be orientated to ELSA research (Lilienfeld et al. Citation2012), which may inform implementation alongside practitioner experience, information from those impacted and information from the local context (O’Hare Citation2015). Sedgwick (Citation2019) recognises the complexity of integrating science and practice within real-world context. Given the adaptable and contextual nature of the ELSA intervention, research plays a role in informing its selection as an intervention as well as its nuanced applications. Practitioners may draw from wide-ranging ELSA research to gain a deeper understanding and wider perspectives around topics of interest. For example, to understand ways to: foster the ELSA-child relationship (e.g. Ball Citation2014, Miles Citation2015, Peters Citation2020, Wong et al. Citation2020), work effectively with parents of children receiving ELSA support (e.g. Barker Citation2017, Wilding and Claridge Citation2016), facilitate positive change in the wider school through ELSA work (e.g. Dodds, Blake, and Garland Citation2015, Robertson Citation2021), understand facilitators and barriers to ELSA implementation in primary (e.g. Hill, O’Hare, and Weidberg Citation2013, Fairall Citation2020) and secondary (e.g. Nicholson-Roberts Citation2019) settings and to support effective ELSA training (e.g. Bland and Macro Citation2018, Edwards Citation2016, Gaffney et al. Citation2020) and supervision (e.g. Atkin Citation2019, France and Billington Citation2020, Osborne Citation2012, Osborne and Burton Citation2014). Having easy access to an overview of the ELSA research base, alongside orientation to specific areas, may therefore support practitioners to integrate research-based evidence with practice-based evidence underpinned by their experience and expertise, to support effective contextual implementation (Fox Citation2011).

Research gaps in the field

Research gaps have been identified based on the findings of the current study. In terms of participant voices, further research involving EPs, CYP (particularly of secondary school age) and parents is needed. Given the role of EPs in training and supervising ELSAs and supporting their linked schools to implement the intervention, their perspectives on topics including training, supervision and implementation are valuable. Though the ELSA intervention is centred on CYP, their voices are lacking within the literature (particularly for secondary age pupils). CYP need to be included in more research studies to avoid an over-reliance on adult perceptions in ascertaining the value and experience of the intervention (Pickering et al. Citation2019, Purcell, Kelly, and Woods Citation2023). In addition to supporting the need for CYP’s views, legislation also supports the need for parent participation, with Children and Families Act (Citation2014) emphasising the importance of parent’s views, wishes and feelings being central to decisions about their child’s provision in school.

In terms of research foci, there is a need for further studies with a primary focus on the wider school and contextual ELSA implementation. Studies covering the topic often asked one question about the wider school or context when exploring facilitators, barriers and perceived impact of the intervention, training and supervision. For example, when seeking ELSAs’ views on the nature, quantity, quality and impact of supervision, Osborne and Burton (Citation2014, 18) asked ELSAs to rate the impact ELSA supervision had on their ‘school as a whole’, which constituted one of 32 questionnaire questions. When exploring ELSAs’ experiences during the pandemic, Endersby (Citation2021, 159) asked ‘Can you describe how others (e.g. school staff/parents) related/interacted with you as an ELSA from the start of the pandemic onwards?’, which constituted one of nine interview questions. There is therefore a need for exploration of how the ELSA intervention interacts with the context of the wider school in greater depth and from varied perspectives.

Studies using quantitative approaches to evaluate the impact of the intervention are also needed, though this is linked to a need to develop sensitive, relevant and usable measures of ELSA outcomes. Finally, given the large number of papers included with the aim of mapping the composition of the ELSA research body, it was beyond the scope of the current study to chart research findings. Therefore, this study potentially lays the foundation for future reviews which synthesise key findings within the ELSA research body, to further inform practice e.g. Purcell and Kelly (Citation2023).

Limitations

A limitation of the study relates to the keywords used for the data-base searches; given that ‘ELSA’ was not an effective search term, it was not possible to screen the vast amount of results. Screening a sample of large results, harvesting references, carrying out citation checks and consulting with the ELSA Network was carried out to support the inclusion of all relevant studies, though it is recognised that some relevant studies may not have been found, or may have been completed following the author’s searches.

Conclusion

ELSA is an adaptable and nuanced intervention, used to support the emotional wellbeing of CYP within their school context. This scoping review has sought to orientate practitioners to the ELSA research body and support the use of research as one strand of evidence, alongside practitioner experiences, service-user perceptions and contextual information. The review provides a basis to inform why the intervention may be selected in a particular school, and to gain a deeper understanding of particular aspects of the intervention and how it may be used.

Findings indicate that the ELSA research body is composed of published literature, doctoral/student studies and local authority evaluation reports. Exploratory or evaluative aims are generally matched to research designs, with most (24) studies aiming to both explore experiences of the ELSA process and evaluate impact, 17 aiming to explore experiences and 12 aiming to evaluate impact. Linking to their aims, a pattern exists whereby most published and doctoral/student studies use exploratory approaches whereas most local authority reports use evaluative approaches. ELSA research has a tendency towards qualitative approaches, perhaps reflective of measurement challenges, though some studies have included measures and scaling questions. Identified research gaps include: studies to hear the voices of EPs, CYP (particularly of secondary age) and parents, research focusing on the wider school and contextual implementation, studies employing quantitative approaches (which is linked to a need to develop sensitive measures of ELSA outcomes) and reviews to synthesise key findings within the ELSA research body.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Helena Rogers

Helena Rogers is a Trainee Educational Psychologist studying at The University of Manchester. Her research interests include social, emotional, and mental health needs, and interventions to support the well-being of children and young people.

Catherine Kelly

Catherine Kelly is the Service User Engagement and Social Diversity Director on the Doctorate in Educational and Child Psychology at the University of Manchester. She is also a Senior Educational Psychologist for Bury Metropolitan Council.

Notes

1. Where more than one study using the same data set was found only the most recent paper was included.

References

- Arksey, H., and L. O’Malley. 2005. “Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework.“ International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8 (1): 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616.

- Atkin, L. 2019. “Support and Supervision for Emotional Literacy Support Assistants (ELSAs): Gathering ELSAs Views About the Support Offered to Them.“ Doctoral thesis submitted for the degree of DEdCPsy, The University of Sheffield.

- Balampanidou, K. 2019. “Emotional Literacy Support Assistant (ELSA) Programme: Child-Centred Approach, Building Trust, Listening and Valuing Children’s Voices: A Grounded Theory Analysis.“ Doctoral thesis submitted for the degree of Professional Doctorate in Child, Community and Educational Psychology, The University of Essex.

- Ball, L. 2014. “Doctoral Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctorate in Educational Psychology.“ The ELSA-Child Relationship: An Analysis of Context and Impact. University College London.

- Barker, H. 2017. “The Emotional Literacy Support Assistant Intervention: An Exploration from the Perspectives of Pupils and Parents.“ Doctoral thesis submitted for the degree of Doctorate in Applied Educational Psychology, The University of Newcastle.

- Barkham, M., and J. Mellor-Clark. 2003. “Bridging Evidence-Based Practice and Practice-Based Evidence: Developing a Rigorous and Relevant Knowledge for the Psychological Therapies.” Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy 10 (6): 319–327. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.379.

- Bland, S., and E. Macro. 2018. “Gloucestershire Educational Psychology Service: ELSA Training: Impact on Thinking and Practice.” Research project submitted for the degree of Doctorate in Educational Psychology. University of Bristol.

- Bowerman, E., and L. Davies. 2018. “The Impact of the Emotional Literacy Support Assistant (ELSA) Programme on Children in Care: Evaluation Report.” Cheshire West and Chester. Accessed August 17, 2022. https://www.elsanetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Impact-of-ELSA-on-Children-in-Care-Spring-2018.pdf.

- Bravery, K., and M. Harris. 2009. “Emotional Literacy Support Assistants in Bournemouth: Impact and Outcomes.” Educational Psychology Service, Bournemouth Borough Council. Accessed December 15, 2021. https://www.elsanetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/ELSA-in-Bournemouth-Impact-and-Outcomes.pdf.

- Burton, S. 2008. “Empowering Learning Support Assistants to Enhance the Emotional Wellbeing of Children in School.” Educational and Child Psychology 25 (2): 40–50. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpsecp.2008.25.2.40.

- Burton, S., and F. Okai. 2018. Excellent ELSAs: Top Tips for Emotional Literacy Support Assistants. Dorset: Inspiration Books Ltd for ELSA Network.

- Butcher, J., E. Cook, and J. Holder-Spriggs. 2013. “Exploring Impact of the Emotional Literacy Support Assistant (ELSA) Intervention on Primary School Children Using Single-Case Design.” Research project submitted for the degree of Doctorate in Educational Psychology, University of Southampton.

- Children and Families Act. 2014. c19–83. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2014/6/contents/enacted.

- DfE (Department for Education) and DoH (Department of Health). 2014. Special Educational Needs and Disability Code of Practice: 0 to 25 Years.

- Dodds, J., R. Blake, and V. Garland. 2015. Investigation into the Effectiveness of Emotional Literacy Support Assistants (ELSAs) in Schools. Accessed January 7, 2022. https://www.elsanetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/ELSA-Report-Investigation-into-the-Effectiveness-of-ELSA-in-Schools_Plymouth.pdf.

- Edwards, L. 2016. The Emotional Literacy Support Assistant (ELSA) Programme Evaluation Report, September 2016. Cheshire West and Chester. Accessed August 17, 2022. https://www.elsanetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Cheshire-West-Chester-Evaluation-Report-Sept-2016.pdf.

- Eldred, K. C. 2021. “‘My EP Is a Safety net’: An Exploration of the Support Educational Psychologists Can Provide for Emotional Literacy Support Assistants Working with Children Who Have Experienced Domestic Abuse.“ Doctoral thesis submitted for the degree of Doctorate in Educational Psychology, University College London.

- ELSA Network. 2020. About ELSA. Accessed May 22, 2023. https://www.elsanetwork.org/about/.

- ELSA Network. 2023. National ELSA Network Training and Supervision Standards. Accessed May 22, 2023. https://www.elsanetwork.org/free_resource/national-elsa-network-training-and-supervision-standards/.

- Endersby, K. 2021. “‘It Was a Time for ELSAs to Come alive’: Exploring Experiences of the Emotional Literacy Support Assistant Role in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic.“ Doctoral thesis submitted for the degree of Doctorate in Applied Educational Psychology, The University of Nottingham.

- Fairall, H. 2020. “The ELSA Project in Two Primary Schools: Reflections from Key Stakeholders on the Factors That Influence Implementation.“ Doctoral thesis submitted for the degree of Doctorate in Educational Psychology, University College London.

- Fox, M. 2011. “Practice-Based Evidence: Overcoming Insecure Attachment.” Educational Psychology in Practice 27 (4): 325–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2011.615299.

- France, E., and K. Billington. 2020. “Group Supervision: Understanding the Experiences and Views of Emotional Literacy Support Assistants in One County in England.” Educational Psychology in Practice 36 (4): 405–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2020.1815179.

- Gaffney, J., C. Brockbank, and J. Davies. 2020. A Qualitative Evaluation of the Emotional Literacy Support Assistant (ELSA) Initiative in West Cumbria from the Perspective of ELSAs. Cumbria County Council. Accessed August 18, 2022. https://www.elsanetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/ELSA-Evaluation-Report-2018-19.pdf.

- Grahamslaw, L. 2010. “An Evaluation of the Emotional Literacy Support Assistant (ELSA) Project: What Is the Impact of an ELSA Project on Support Assistants’ and Children’s Self-Efficacy Beliefs?.“ Doctoral thesis submitted for the degree of Doctorate in Applied Educational Psychology, The University of Newcastle.

- Harris, P. 2020. “An Exploration of Emotional Literacy Support Assistants’ Understanding of Emotional Literacy, and Their Views on and Use of Stories and Storytelling.“ Doctoral thesis submitted for the degree of Doctorate in Educational Child and Community Psychology, The University of Exeter.

- Hill, T., D. O’Hare, and F. Weidberg. 2013. ”He’s Always There When I Need him’: Exploring the Perceived Positive Impact of the Emotional Literacy Support Assistant (ELSA) Programme.” Research project submitted for the Degree of Doctorate in Educational Psychology. University of Bristol.

- Hills, R. 2016. “An Evaluation of the Emotional Literacy Support Assistant (ELSA) Project from the Perspectives of Primary School Children.” Educational and Child Psychology 33 (4): 50–65. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpsecp.2016.33.4.50.

- Krause, N., L. Blackwell, and S. Claridge. 2020. “An Exploration of the Impact of the Emotional Literacy Support Assistant (ELSA) Programme on Wellbeing from the Perspective of Pupils.” Educational Psychology in Practice 36 (1): 17–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2019.1657801.

- Leighton, M. K. 2015. “ELSA: Accounts from Emotional Literacy Support Assistants.“ Doctoral thesis submitted for the degree of DEdCPsy, The University of Sheffield.

- Levac, D., H. Colquhoun, and K. O’Brien. 2010. “Scoping Studies: Advancing the Methodology.” Implementation Science 5 (69). https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69.

- Lilienfeld, S. O., R. Ammirati, and M. David. 2012. “Distinguishing Science from Pseudoscience in School Psychology: Science and Scientific Thinking as Safeguards Against Human Error.” Journal of School Psychology 50 (1): 7–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2011.09.006.

- McEwan, S. 2019. “The Emotional Literacy Support Assistant (ELSA) Programme: ELSAs’ and Children’s Experiences.” Educational Psychology in Practice 35 (3): 289–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2019.1585332.

- Miles, N. S. 2015. “An Exploration of the Perceptions of Emotional Literacy Support Assistants (ELSAs) of the ELSA-Pupil Relationship.“ Doctoral thesis submitted for the degree of Doctorate in Educational Psychology, The University of Cardiff.

- Moher, D., A. Liberati, J. Tetzlaff, and D. G. Altman. 2009. “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement.” Physical Therapy 89 (9): 873–880. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/89.9.873.

- Nicholson-Roberts, B. R. 2019. “‘A Little Pebble in a pond’: A Multiple Case Study Exploring How the Emotional Literacy Support Assistant (ELSA) Project Operates in Secondary Schools.“ Doctoral thesis submitted for the degree of Doctorate in Educational Psychology, University College London.

- O’Hare, D. P. 2015. “Evidence-Based Practice: A Mixed Methods Approach to Understanding Educational Psychologists’ Use of Evidence in Practice.“ Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctorate in Educational Psychology, The University of Bristol.

- Osborne, C. 2012. “Feedback on Emotional Literacy Support Assistant (ELSA) Supervision.” Hampshire Research and Evaluation Unit. Accessed August 18, 2022. https://www.elsanetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/ELSA-supervision-evaluation-2012.pdf.

- Osborne, C., and S. Burton. 2014. “Emotional Literacy Support Assistants’ Views on Supervision Provided by Educational Psychologists: What EPs Can Learn from Group Supervision.” Educational Psychology in Practice 30 (2): 139–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2014.899202.

- Peters, S. 2020. “Exploring the Experience for Young People of the Emotional Literacy Support Assistant (ELSA) Intervention: Case Studies in Secondary Schools.“ Doctoral thesis submitted for the degree of Doctorate in Applied Educational Psychology, University College London.

- Peters, M. D. J., C. M. Godfrey, H. Khalil, P. McInerney, D. Parker, and C. B. Soares. 2015. “Guidance for Conducting Systematic Scoping Reviews.” International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare 13 (3): 141–146. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050.

- Pickering, L., J. Lambeth, C. Woodcock, and J. Greene. 2019. “The Emotional Literacy Support Assistant (ELSA) Programme: Can You Develop an Evidence Base for an Adaptive Intervention?” DECP Debate 1 (170): 17–22. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpsdeb.2019.1.170.17.

- Purcell, R., and C. Kelly. 2023. “A Systematic Literature Review to Explore Pupils’ Perspectives on Key Outcomes of the Emotional Literacy Support Assistant (ELSA) Intervention.” Educational Psychology in Practice 39 (2): 201–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2023.2185208.

- Purcell, R., C. Kelly, and K. Woods. 2023. “Exploring Secondary School Pupils’ Views Regarding the Skills and Outcomes They Gain Whilst Undertaking the Emotional Literacy Support Assistant (ELSA) Intervention.” Pastoral Care in Education 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643944.2023.2265390.

- Rees, C. 2016. “The Impact of Emotional Literacy Support Assistant Training on Teaching Assistants’ Own Trait-Emotional Intelligence and Self-Efficacy and Their Perceptions in Relation to Their Future Role.“ Doctoral thesis submitted for the degree of Doctorate in Educational Psychology, The University of Cardiff.

- Ridley, N. 2017. “What Is Really Going on in the Group Supervision of Emotional Literacy Support Assistants (ELSAs) – an Exploratory Study Using Thematic Analysis.“ Doctoral thesis submitted for the degree of Professional Doctorate in Child, Community and Educational Psychology, The University of Essex.

- Robertson, H. 2021. “Can Emotional Literacy Support Assistant (ELSA) Interventions Support Positive Change in the Wider School?.“ Doctoral thesis submitted for the degree of Doctorate in Applied Educational Psychology, The University of Newcastle.

- Rogers, H. 2022. “A Participatory Exploration of the ELSA Steering group’s Hopes and Needs for Future ELSA Research.” A Doctoral Assignment Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Educational and Child Psychology. The University of Manchester.

- Russo, I. 2022. ‘It’s a Strategic toolkit.’ How Can the Emotional Literacy Support Assistant (ELSA) Programme Be Used to Support Children and Young People Post-Lockdown?” Research project submitted for the degree of Doctorate in Educational Psycholog, University College London.

- Sedgwick, A. 2019. “Educational Psychologists As Scientist Practitioners: A Critical Synthesis of Existing Professional Frameworks by a Consciously Incompetent Trainee.” Educational Psychology Research and Practice 5 (2): 1–19.

- Seligman, M. E. P. 2011. “Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Wellbeing.” Policy 27 (3): 60–61.

- Shotton, G., and S. Burton. 2018. Emotional Wellbeing: An Introductory Handbook for Schools. 2nd Ed. Oxon: Routeledge.

- Thomas, A. M. 2022. “A Content Analysis Evaluating the Emotional Literacy Support Assistants Program in Wales.” A Dissertation in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Clinical Psychology. University of South Wales.

- Tricco, A., E. Lilie, W. Zarin, K. O’Brien, H. Colquhoun, M. Kastner, D. Levac, et al. 2016. “A Scoping Review on the Conduct and Reporting of Scoping Reviews.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 16 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-016-0116-4.

- UNICEF. 2010. “Convention on the Rights of the Child.” Accessed May 23, 2023. https://downloads.unicef.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2010/05/UNCRC_PRESS200910web.pdf?ga=2.112113409.483055817.1552743423-375513767.1552743423.

- Wilding, L., and S. Claridge. 2016. “The Emotional Literacy Support Assistant (ELSA) Programme: Parental Perceptions of Its Impact in School and at Home.” Educational Psychology in Practice 32 (2): 180–196.

- Wong, B., D. Cripps, H. White, L. Young, H. Kovshoff, H. Pinkard, and C. Woodcock. 2020. “Primary School Children’s Perspectives and Experiences of Emotional Literacy Support Assistant (ELSA) Support.” Educational Psychology in Practice 36 (3): 313–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2020.1781064.

- Woods, K. 2020a. Critical Appraisal Frameworks: Qualitative Research Framework. The University of Manchester (Education and Psychology Research Group).

- Woods, K. 2020b. Critical Appraisal Frameworks: Quantitative Research Framework. The University of Manchester (Education and Psychology Research Group).