ABSTRACT

This paper explores the experiences of a small sample of girls in English schools at risk of permanent exclusion. A range of visual methods were used to collect data from girls in mainstream secondary schools and an alternative provision setting which formed the basis of subsequent interviews. Through an examination of extant research and the data from this study, it is argued that issues of visibility and voice continue to be prevalent for girls at the margins of education. This paper contends that within the current educational climate in England, girls’ experiences appear to have remained the same as, or deteriorated compared to their contemporaries 20 years ago. It concludes by suggesting some possible next steps and implications for schools and those supporting girls in educational settings.

Introduction and background

This paper will report on the results from a recent small-scale qualitative study on girls’ experiences of being at risk of permanent exclusion (PEX) from mainstream secondary schools in England and consider how the current English educational climate impacts on their experiences. It will begin with a brief contextual overview of the ‘English exceptions’ that present a challenge to inclusion for girls, as well as the current picture around exclusions in their various forms. The paper will then focus on two recurring themes: visibility and voice, using these as lenses to examine literature around girls and PEX and to analyse and discuss the data collected. It will conclude with some possible next steps and highlight some of the implications for those supporting girls at risk of PEX.

Permanent exclusion from school is a complex and wicked problem (Daniels, Porter, and Thompson Citation2022), which has a significant impact on both the student and the school (Murphy Citation2022). It is also a growing problem in England, with PEX now 60% higher than 5 years ago (Social Finance Citation2020; Thompson, Tawell, and Daniels Citation2021), with PEX in England continuing to significantly outweigh those of the other UK nations (Black Citation2022; Cole et al. Citation2019; McCluskey et al. Citation2019). Increasing rates of English PEX were highlighted in the landmark Timpson review (DfE Citation2019a, Citation2019c), with statistics showing that for the autumn term before the covid pandemic, PEX had increased by 5% (to 3200) compared to the same time the previous year (DfE Citation2021). Only legal exclusions are reported in DfE statistics, but it is suggested these may be the tip of the iceberg with schools removing pupils from their rolls and excluding them in a range of other alternate and illegal forms. Although there are clear guidelines around legal PEX, exclusion exists in other forms, such as self-exclusion through persistent absence or truancy, early exits, and managed moves where schools may discuss with parents/guardians enrolling the pupil at another school or having dual registration between two schools or settings. At their worst these become ‘off-rolling’ where a pupil is taken off one school’s roll without being registered elsewhere, but even where a pupil remains on a school’s roll, they may experience internal exclusion (IE) through their school’s behaviour policy, where they remain on-site but in isolation, sometimes for protracted periods, supporting arguments that;

In addition to the formal systems of school suspension and expulsion are a raft of practices that indicate that the scale of exclusion is much larger. (Daniels, Porter, and Thompson Citation2022, 7)

Ferguson (Citation2019, 2) argued the legal regulation of PEX was ‘in crisis’, with Osler (Citation2006, 575), who had highlighted the same issues over a decade earlier, noting pupil exclusion was contextual and largely informed by school-based factors. Illegal exclusions remain ‘chronically under-researched’ and only came to light in a DfE publication in 2008 (Whitehouse Citation2022), but studies suggest (Done and Knowler Citation2020, Citation2021) schools in England are increasingly engaging in illegal ‘hidden and strategic exclusions’ through ‘non-linear and unique’ practices that remove pupils from school, circumventing formal procedures (Done and Knowler Citation2022, 182).

Figures (FFT Education Datalab Jan 2023) suggest that the number of pupils leaving school rolls with no explanation is now higher than ever, in part due to a range of ‘perverse incentives’ to exclude pupils (Ferguson Citation2019; Social Finance Citation2020; Thompson, Tawell, and Daniels Citation2021). These incentives include an impetus for schools to be seen as competitive in the marketised landscape of education (Archer Citation2004; Thompson, Tawell, and Daniels Citation2021; Whitehouse Citation2022), creeping pressures of performativity and accountability (Cole et al. Citation2019; DfE Citation2023b; Perryman Citation2022) and funding issues, with students’ behaviour often requiring ‘costly’ interventions or support (Wright, Weekes, and McGlaughlin Citation2000, 20) at a time of austerity when school budgets are extremely stretched (Thompson, Tawell, and Daniels Citation2021). Some Multi Academy Trusts (MATs) have also adopted an increasingly strict behaviourist approach (Thompson, Tawell, and Daniels Citation2021; Whitehouse Citation2022) and even a culture of ‘flattening the grass’ (Hazell Citation2019; Perraudin Citation2019), and ‘hyper-behaviourism’ (xxx, 2023), where policies are inflexible, cover a large number of schools with different contexts and micromanage staff responses (Kulz Citation2018). There is also some evidence which suggests that the process of academisation has served to break down local knowledge between schools and authorities, thereby forcing a move away from ‘distributed expertise’ (Thompson, Tawell, and Daniels Citation2021). These pressures on schools and schools’ responses to them mirror the contradicting messages in DfE policy on the need to develop and support pupil (and staff) mental health (Brown Citation2018; DfE Citation2014, Citation2019) with simultaneous pressure to raise academic standards and enforce enshrined behaviourist ideals of ‘discipline, authority and respect’ (Armstrong Citation2014; DfE Citation2013, Citation2016, Citation2019b). The ‘unhelpful tone and content’ of policies which have led to a ‘change of tone in schools and a move to be less inclusive’ was noted by participants in Thompson et al.’s (Citation2021, 37) research.

Although PEX for boys continues to significantly outweigh those for girls, with boys three times more likely to experience PEX than girls (DfE Citation2021), there have been substantial increases in the number of girls PEX. In the autumn term 19/20 girls’ exclusions grew by 7.8% compared to 4.8% for boys (Agenda Citation2021), mirroring trends from 2012 to 2019 showing PEX for girls was increasing more rapidly than for boys (Agenda Citation2021; Black Citation2022; DfE Citation2019c; Mills and Thomson Citation2022). Despite this, there is a lack of recent, focused research considering girls’ experiences of being at risk of PEX. However, the limited number of extant studies that do exist suggests recurrent issues around visibility and voice, and this paper will now focus on these themes to continue to problematise the issues for girls at risk of PEX.

Visibility

Although the statistics showing increasing rates of PEX for girls are concerning, as discussed these may actually be underreporting the definitive number of girls excluded from school and obfuscating their visibility (Mills and Thomson Citation2022) because, as has been noted, exclusion is a ‘complex intervention’ (Daniels, Porter, and Thompson Citation2022) and also an ambiguous term. It has been suggested that girls are more likely to experience forms of ‘less visible exclusion and marginalisation’ (McCluskey Citation2008, 449) such as functional or self-exclusion (Agenda Citation2021; Arnot and Mac an Ghaill Citation2006), informal exclusion, ‘off-rolling’, early exits and managed moves (Porter and Ingram Citation2021). This follows Osler, et al.’s (Citation2002) definition of exclusion, which mirrors the comparatively broad references in academic literature in contrast to the narrow legal definition in England (Mills and Thomson Citation2022), it characterises exclusion as;

… feelings of isolation, disaffection, unresolved personal, family or emotional problems, bullying, withdrawal or truancy. (Osler et al. Citation2002, 3)

Osler et al.’s view and the definition this paper uses begin to acknowledge the ‘problematic’ (Daniels, Porter, and Thompson Citation2022, 7) nature of defining a practice that is a ‘multifaceted cultural and historical phenomenon or process and a complex intervention’. The DfE has acknowledged that exclusions take no account of pupils’ context focusing on behaviour as discrete and occurring in a vacuum (Graham, White, and Potter Citation2019; Murphy Citation2022). This runs contrary to studies noting the multiple, complex forms of disadvantage including poor mental health, abuse, discrimination and poverty (Tejerina-Arreal et al. Citation2020) girls at risk of PEX experience. Significant issues with mental health and further marginalisation have also been reported for girls during and after PEX, with 74% of girls in the youth justice system having been excluded from education (Agenda Citation2021; DfE Citation2019c). Girls’ behaviours can also often go unseen, with suggestions boys externalise behaviours whereas girls internalise, avoiding confrontation and withdrawing instead (DfE Citation2019c), being more likely to experience anxiety and depression than boys, which may contribute to self-exclusion by truanting or absenteeism (Fazel and Newby Citation2021). The collating of exclusion numbers therefore points to a lack of visibility for girls in formally reported DfE statistics and alludes to significantly more happening ‘behind the scenes’, suggesting that the full extent of girls’ exclusions, beyond the increasing formally reported ones, remains unseen and invisible. It has been reported that;

… girls are experiencing exclusion from education in distinct ways from boys, but also they are more likely to experience exclusions that lack formal accountability measures. (Social Finance Citation2020, 14)

This perpetuates a vicious cycle, where girls’ PEX remain absent from wider narratives around support and inclusion, and as a result, little consideration is given to approaches to support them. Pirrie and Macleod (Citation2009, p.193) noted a clear link between PEX and being ‘missing’ from education and/or being ‘hard to find’, with ‘traces of individual young people rapidly fading from view’ after PEX. Given the numbers of pupils currently not on roll and rising exclusions for girls, their lack of visibility in data and discussions presents a challenging and very worrying picture.

Conversely, much press has surrounded the issue of boys and exclusion, which has been the focus of DfE policy and school thinking for a number of years. As a result, ‘disaffection has been constructed as an almost exclusively male issue in much media and policy’ (Archer Citation2004, 101) with girls, who make up half of the school population, not being given such close consideration (Mills and Thomson Citation2022). The narrative that perpetuates is that girls are the ‘hard working majority’ (McCluskey Citation2008, 452), whose success comes at the detriment of boys (Osler Citation2006) and who operate in ‘girl-friendly’ school environments and, therefore, are less likely to experience behaviour difficulties (Osler Citation2010). This preconception is suggested to be so entrenched in thinking around girls that those who do not conform as an ‘emblem of success’ (Allard and McLeod Citation2007, 1) are perceived as ‘doubly dangerous’ (Nind, Boorman, and Clarke Citation2012, 664). Stereotypes may account for the lack of examination of girls’ experiences or focus on the issues they face, despite the substantial increases in rates of PEX. Girls continue to remain ‘invisible’ (Osler et al. Citation2002; Social Finance Citation2020) and ‘lost’ (Agenda Citation2021; Clarke et al. Citation2011) in thinking around, and reports of exclusion, because there is a pervading assumption, perhaps built on the invisibility of girls in government PEX figures, that they do not present a problem or require any additional support and that they usually excel in a system biased towards them.

This brief consideration of issues around girls’ visibility illustrates an interesting paradox; girls’ issues are not visible in externally reported statistics and therefore not visible in policy or wider educational discourses. As they are not visible, no additional support, services or research are provided or seen as required. This perpetuates inaccurate stereotypes which serve to further entrench girls’ invisibility.

Voice

It has been acknowledged that discipline and exclusion are perceived to be done ‘to’ pupils, with student voice largely absent from discussions around PEX (Mills and Thomson Citation2022). However, this is a chronic issue for girls who are systematically ‘silenced, marginalised and denied opportunities to express their views’, and particularly acute for girls at risk of PEX, who in the spectrum of ‘unheard voices’ were reported to have ‘the least represented views’ (Clarke et al. Citation2011, p.765). Concerns over girls’ voice are not new, with continuing beliefs that ‘girls are not a problem’ (Arnot and Mac an Ghaill Citation2006; Osler et al. Citation2002; Ringrose Citation2007). Osler et al. (Citation2002) reported girls were ‘an underestimated minority’ in discussions on behaviour and exclusions over 20 years ago and noted a ‘lack of interest’ in girls’ experiences from policymakers and research funding bodies (Osler and Vincent Citation2003). Archer (Citation2004) asserted that a ‘crisis of masculinity’ meant issues related to girls’ education had ‘fallen off the radar’ in a context described by Lloyd (Citation2005a) as one where a majority of male authors were emphasising boys’ experiences in their research.

The challenge of reporting girls’ voices when they do not represent the perceived norm highlights the ‘simultaneously normative and demonised’ (Allard and McLeod Citation2007) gendered views of girls’ expected behaviours (Carlile Citation2008; Russell and Thomson Citation2011), reinforcing the invasive stereotype of ‘bad boys’ and ‘good girls’. This can mean that girls who do not perform as ‘good’, transgress not only school rules but also gender norms, affording their actions a ‘double stigma’ (Lloyd Citation2005b, 2). Gendered views of what constitutes appropriate behaviour (Carlile Citation2008; Russell and Thomson Citation2011) have resulted in perceptions that some girls have used their voice in unacceptable forms which has worked against, rather than supported their inclusion (Nind, Boorman, and Clarke Citation2012).

This brief contextual review highlights two overarching themes impacting on girls’ experiences: voice and visibility. Visibility, as discussed, is an issue in reported data, girls’ physical visibility in school and the visibility of their problems. Hearing girls’ voice in research, policy and guidance on exclusion is rare, and opportunities for girls to be heard in school settings are also usually very limited (Osler and Vincent Citation2003; Osler et al. Citation2002; Russell and Thomson Citation2011). This paper will now share the data and analysis from a visual methods project which aimed to give girls at risk of PEX from mainstream secondary schools in England an opportunity to share their experiences.

Materials and methods

This project used visual methods and a feminist methodology which aimed to foreground girls’ voice and be open, flexible and engaging for participants. Once full ethical approval from the university, school and girls had been gained, the project collected data across three different settings using three different forms of data collection as shown in . For brevity, this paper will only report on the images and semi-structured interviews (for a detailed consideration of the ecomaps see E. Clarke Citation2023b). All participants were nominated by the school and were largely positive about taking part (not least because they had some time out of lessons). Only five participants decided not to continue once the tasks were explained (all Year 7), all other girls completed each element of data collection (image, ecomap and interview).

The age distribution of participants in this study reflects that statistics showing pupils are most at risk of exclusion in Year 10 and temporary exclusion in Year 9 (DfE Citation2023a), mirroring broader reported concerns about the impact of national assessments on schools and pupils (Cole et al. Citation2019; Education Select Committee Citation2018; Martin-Denham Citation2021). This suggests that the schools who nominated girls to participate, at least to some extent, are representative of many mainstream English secondary schools.

Visual methods, specifically photo-elicitation, were selected as they have been suggested to avoid traditional ‘malestream’ and ‘androcentric’ methods of data collection, which focus on gaining objective and concrete data and are ‘liable to oppressive use’ (Kohli and Burbules Citation2013, p.36). Given the issues discussed with girls’ visibility, considering ways to empower girls and support their voice in research were key, as Clarke et al. (Citation2010, 786) asserted, beginning to address the ‘missing pupil contribution compared to the dominance of professional discourses’. This aim shaped the data collection methods and methodology for this project. Alldred and Gillies (Citation2012) have argued that ‘women’s subjectivities come to be defined through masculinist knowledge structures’, an aspect that this project actively tried to avoid by using photo-elicitation which considers the;

… tension between the researchers’ control and participants’ voice … creating a comfortable space for discussion and involving participants in a way that does not limit their responses. (Bates et al. Citation2017, 461)

In photo-elicitation interviews, which this project used as a starting point for semi-structured interviews, participants control the agenda, effectively ‘altering the tone of the interview’ by mediating the images shared, creating dialogue to understand, rather than avoiding partiality (Bates et al. Citation2017). Overlaps between visual and feminist methodologies have been identified (Hernandez-Albujar Citation2007; Pink Citation2001) with ineluctable links between feminist methodologies and innovative approaches due to inherent commitments to empower participants (Ortega-Alcázar and Dyck Citation2012). Oliffe and Bottorff (Citation2007) argued even more forcefully that without considering alternatives, such as visual methods, researchers may inadvertently ‘perpetuate essentialised ideals’ about subjects – an aspect this study was keen to avoid.

Data collection comprised different tasks, including producing either a drawing or sourcing one from a website (pixabay), completing a list of challenges and resources and mapping these onto an ecomap, and participating in a semi-structured interview. Data was collected from all girls in the same sequence for each participant;

selecting/drawing an image

listing challenges and resources

adding these to a blank ecomap

followed by a semi-structured interview

It was made clear to girls that they could participate in some, all or none of the elements of data collection and procedures for withdrawing data after a ‘cooling-off’ period were explained, although no girls subsequently chose to do so.

The ecomaps (reported on in E. Clarke Citation2023b) is comprised of blank concentric circles, where girls were asked to position themselves in the ‘bulls’ eye’ of these circles and then map the impact of the challenges and resources they had listed, with those closest to the centre having the biggest impact, and those in the outer circles having lesser impact. Although informal and not quantitatively significant, the element of quantification led me to call them ‘weighted impact maps’ (E. Clarke Citation2023b) and afforded some indication of how significant the challenges and resources the girls listed were to them.

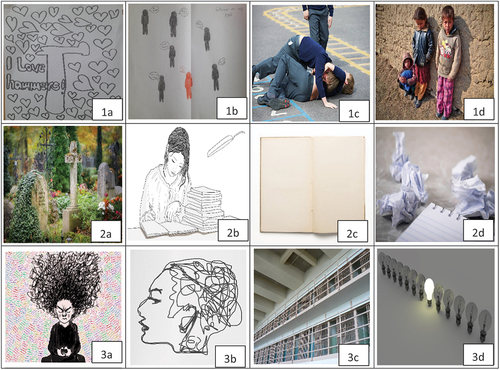

When considering an image, almost all girls chose to select an internet image, with only two drawing pictures. shows the images girls selected and/or produced after being prompted to;

‘Find/draw a picture that shows what school is like for you’.

Almost all girls, including those who chose to draw their own pictures, completed this aspect of data collection quickly, with girls who searched for images on-line being very decisive about what they wanted, even when looking at a range of similar pictures. The selection/completion of the image was followed by a photo-elicitation/semi-structured interview. The first question focused on their image:

‘Can you tell me about your image/picture?’.

For some girls this was a way into talking about their experiences of school more widely, while others remained tightly focused on their image. The only other two planned questions in the semi-structured interview were:

‘What do you wish teachers knew about girls’ experiences at school?’

‘What three things would you change to make girls’/your experiences of school better?’

In considering girls’ experiences when at risk of PEX this paper, as Hall (Citation1990, in Benjamin et al. Citation2003, 549) did, uses the concept of ‘strategic essentialism’;

… that can take account of the very real social and material consequences for individuals of belonging to particular groups but that does not assume that those consequences are fixed and unchanging, nor that they are a necessary condition of some individual, inherent characteristic or perceived lack.

This allows a discussion of ‘girls’’ experiences from an understanding that context, time and so on will all result in different experiences for different students, but allows a functional ‘grouping’ to consider shared, overlapping or similar experiences for particular individuals. This paper takes care not to suggest ‘all girls’ or ‘all girls at risk of PEX’; however, given that the recurring themes from this small-scale study reflect those in extant research, it would appear there are a number of persistent elements that girls who are at risk of PEX may experience. A discussion of these key themes will now follow.

Results

Thematic analysis was used to analyse the interview transcripts, and rather than content analysis of the images, similarities were sought between the themes that emerged from the interviews and the images. Although no girls explicitly used the terms ‘visibility’ or ‘voice’, the key themes they discussed can be suggested to revolve around these aspects, for example, Georgia, who had been placed in IE that morning contended ‘they’ve boarded up the windows and don’t listen to you’ which reflects issues of both visibility and voice. The results and discussion that follow will be grouped under these terms with key themes from images and interview transcripts used to exemplify them. Although voice and visibility have been chosen as themes for this study as they are present in the small body of extant research and also evident in the themes in the data analysis, they are not the only lenses that can be used to consider girls experiences. Nind et al. (Citation2012) noted how Charmaz’s (Citation2014, p.9) categories of ‘boundaries and barriers’ from her work on marginalisation could also be appropriate.

Visibility

Many of the images suggest a perceived lack of visibility. Research (Russell and Thomson Citation2011) has noted the importance of girls’ efforts to ‘influence and negotiate their position’, in schools, which is chronically and acutely challenging for girls who are either invisible or too visible to do so. Despite being able to select from millions of images, none of the participants picked any which mirrored them or of schoolgirls (with the possible exception of Unicorn) more widely. The images overall are absent of portrayals of individual voice or power, depicting instead unseen prisoners, unseen bodies, or unseen work, with images 2b, 2c and 2d all showing blank paper, something which was important to the girls who selected them. Participants’ interviews highlighted simultaneous feelings of being invisible and also too visible. Loller’s image illustrated how she felt ‘out place’ and ‘almost too different’ to her peers, with Topsy’s drawing mirroring this, ‘I’m the odd one out, it’s always me’ she noted, suggesting that teachers and ‘other people as well, people who don’t even know me’ singled her out for being different. Visibility was also highlighted by Unicorn who recounted ‘there’s lots of graffiti about me in the toilets’.

Peta suggested girls’ uniforms were particularly visible to teachers in ways boys’ were not, ‘they [teachers] don’t care about education it’s about earrings and that, they care more about jewellery than getting on with lessons’, noting different expectations for teachers which were very visible to her, ‘they [teachers] come in with loads of jewellery and we have to be over sixteen to wear it which is a bit mental’. Uniform was an aspect of visibility many of my participants found challenging, with teachers being perceived to enforce rules focussing on girls’ appearance. This reflects the teachers’ in Archer et al.’s (Citation2007) study 16 years ago, who reported girls’ focus on ‘looking the part’ was a distraction from their education. Girls in one school in my study visibly subverted staff expectations by wearing and showing more jewellery than was exemplified in the school policy, rolling their skirts up so they were shorter, and wearing non-regulation shoes. Staff in this school policed and reinforced uniform expectations in line with a new policy, resonating with Allard and McLeod’s (Citation2007) findings that girls who do not conform to stereotypes of gender were perceived as ‘dangerous’ and therefore ‘demonised’. Alicia recounted how she struggled to understand;

… how trainers and jewellery affect learning. They [teachers] are genuinely having a go for the slightest thing, it makes me lose my temper, I don’t like people having a go at me and shouting.

The focus on girls’ adherence to imposed dress standards also supports (Archer et al.’s (Citation2007), p.170) argument that the ‘ideal female pupil is … a specifically middle-class and de-sexualised’ one. Uniform served as a nexus of intervention from teachers and anger or lack of compliance for girls, yet it could be suggested that girls were attempting to balance challenging teachers’ (implicit) bias of what a ‘good’ or ‘correct’ girl looked like and ideas of what a ‘good’ or ‘correct’ girl looked like in their peer group. Ruby highlighted ‘it’s all around how you look’, supporting Archer et al.’s (Citation2007, 168) findings that ‘intricate negotiations around the markers of style’ and ‘successful performances’ of gender, such as being desirable but not too desirable, were rewarded with ‘status and approval’ from girls’ peer group. Being visible to peers in a way which girls in my study deemed acceptable by modifying their uniform may have been an opportunity to gain power and agency in a system and environment where they felt actively robbed of it;

As various feminist writers have noted … women’s investment in their (heterosexual) appearance constitutes one of the few available sites for the generation of symbolic capital. (Archer et al., Citation2007, p.169)

Teachers also featured consistently in girls’ comments relating to being visible, with Louise feeling staff ‘just follow me around and stare at me’, Georgia stated ‘teachers stand outside the toilets at lunch and break or put cameras in the toilet area so they can see who comes in and out of the cubicles’. She also felt very conscious about the possibility of being singled out and made visible in lessons ‘if a teacher picks on me to answer a question I just won’t come to the next lesson’. Louise indicated her image exemplified how school, and the possibility of teachers singling her out in lessons made her ‘anxious’ which was visible to others ‘my face goes all blotchy and I start shaking, it’s hard to breathe’. She noted that when this happens, she wants to leave to be less visible to others but then gets ‘put in IE (internal exclusion) for walking out of lessons’. Aimee felt that teachers’ stereotypes of gender made girls’ less visible, ‘certain teachers overlook the girls, they pin it on your hormones’. This idea of discounting, ignoring or refusing to ‘see’ girls’ behaviour as it was ‘simply hormones’ was also cited by participants in Cruddas and Haddock’s (Citation2005) study. Aimee’s stance was reinforced by others’ views about school’s pervasive sexism in relation to behaviour with ‘boys let off with so many things it doesn’t make sense, there’s no fairness between boys and girls’ (Neveah), and Unicorn identifying differences in the sanctions boys and girls received for the same behaviours. Topsy also noted ‘boys pick on you to make themselves look good’ reinforcing the position of girls in relation to their gender.

Girls often alluded to issues in relationships with teachers who they perceived did not care about them or know them as individuals and were not prepared to ‘see’ the context of their behaviour. Johnny illustrated how angry school made her in her image and how she felt ‘pressure’ from teachers who she felt did not ‘see’ her or what was happening to her, ‘teachers should know my problems before they shout at me’. Unicorn illustrated this in her wish that teachers should;

… not exclude me for swearing, ‘cos I’ll definitely say sorry and definitely apologise, I don’t think before I speak.

However, she argued that she did not feel teachers understood this, or knew her well enough to give her any flexibility around her behaviour. Alicia shared her wish that girls could ‘open up to teachers without them telling everyone’. Aimee also noted how she felt teachers should ‘take more notice of how you behave, there might be something behind it’. This was demonstrative of the complex lives many of the participants had both within and beyond school, and the pressure they felt to ‘conform’ (Loller) in the school system despite the other elements in their life that made this difficult. None of the images girls’ selected or drew included an adult or other figure who could be representative of a teacher. This may link to girls’ consensus that teachers had a negative impact on their experience of school. Unicorn suggested relationships with teachers were a key source of stress which was compounded;

… when I don’t get along with the teacher, then it [feeling stressed] escalates and I start screaming then I wander around the school.

Although Louise conceded that ‘some teachers know what they’re doing’ she felt almost all had a ‘massive problem with me’, a perception shared by all of the mainstream girls.

The girls’ images do not display any examples of friendship (with the possible exception of Aimee) and images either show a figure in isolation, fighting, or no figure at all. Positive relationships with friends were rarely mentioned (but did occur in the ecomaps), but tensions of being ‘seen’ by peers were a feature of the interviews, hinting at the porous nature of girls’ relationships and how issues out of school can bleed into school and vice versa, affecting feelings of exclusion and marginalisation. This was illustrated by Sara who shared how peer relationships outside school impacted on her experiences in school,

Sometimes school can be an unsafe environment and lower your self-esteem … some girls aren’t nice…they leak pictures, even nudes and all that, people call you a slag and bait you out, your face will be everywhere in the whole borough, a girl will hate you because she’s seen you on social media.

In their small-scale study of Year six students (10–11-year-olds) in England, Benjamin et al. (Citation2003) argued that inclusion/exclusion was ‘negotiated’ moment-to-moment by teachers and pupils, however,

… in classroom contexts framed by overlapping sets of micro-cultures: children’s and teachers’ micro-cultural worlds, and the struggle for power and prestige within those worlds, were key in producing moments of inclusion and exclusion for specific children and groups of children. (p. 547)

Issues of visibility appear to be akin to walking a tightrope, where girls need to balance being visible and invisible in different ways with peers and with teachers. My participants all noted this as a site of struggle and had difficulty being seen in ‘multiple terrains each with conditions of membership’ (Fields and Payne Citation2016).

Voice

When examining the images, none appears to show the figures or elements in the image selected speaking or using their voice. In her image of the graveyard, Ruby suggested she felt unheard and that ‘teachers should listen to pupils’ instead of girls ‘just going round in circles with teachers’ and experiencing the ‘same thing every day’. Georgia felt she was unable to have a voice either at school or at home as staff called her parents when her behaviour at school was challenging which resulted in her feeling ‘I have them [teachers] shouting at me here and then my mum shouting at me at home, no one listens’. The theme of being ‘listened to’ was pervasive throughout all the different forms of data collected and mirrored Cruddas and Haddock’s (Citation2005, 168) findings that ‘girls wanted to be listened to and treated as equals’. When discussing experiences that were helpful, Peta highlighted how important it was that teachers ‘make compromises and listen to what we say’. She noted how in some lessons the teachers were able to make pupils feel relaxed and ‘able to talk [on task]’, but that this was unusual and that ‘most people in the lesson don’t really like me, the teacher doesn’t like me, but I need someone to talk to in the lesson’.

Many of my participants noted a perceived lack of opportunities for their views to be heard or taken seriously by staff, with Ruby wishing staff could ‘treat us like adults not little kids’, Timmy noting teachers were ‘rude’ and Neveah wanting teachers to ‘treat girls how they would treat their daughters’. Aimee noted her wish for teachers to ‘actually listen and make time for things … not just for a week’, suggesting that she wanted ‘more people who can make more time for you’. Peta perceived her school did not treat pupils like ‘humans … we’re kids, it shouldn’t feel like a prison’ and that respect should be earnt rather than expected, arguing that teachers ‘think I should have respect for them when they can be shitty to me’. This lack of reciprocity was a common theme summed up by Georgia;

… when they shout it doesn’t mean we’re going to listen, we’re going to shout back, if they listen to me then I’ll listen to them.

My participants’ responses align with those in Nind et al.’s (Citation2012) study which noted marginalised girls had often experienced further marginalisation due to expressing themselves in ways schools found challenging and had found ‘power’ or voice ‘in ways which often worked against them’, failing to comply with the ‘gendered, classed and racialised and sexualised’ expectations from within dominant discourses’ (p.768).

Seeking acceptance and a ‘voice’ within their peer group was documented by Cruddas and Haddock (Citation2005, 169), noting how the ‘intense and complex’ friendships, girls in particular, tend to form can either ‘create networks that support or enable learning’ which was not raised in my participants’ interviews or ‘create an oppositional culture to the culture of learning’ which represented the examples participants shared in this study. Johnny asserted that having ‘someone for students to talk to, not a teacher, to know where you are and sit and talk with you’ was very important, yet supportive friendships were not a strong theme in my data. Despite Archer et al. (Citation2007, 153) noting peer group acceptance and ‘informal networks’ were a ‘vital aspect’ of schooling and one of the ‘most powerful and potent forces effecting change’ in young people, my participants largely discussed how relationships with peers were problematic. Timmy noted how ‘if they [girls] have something to say to you, they say it to your face’ and Sara highlighting ‘I’m not all about the drama but it happens to other girls and some of my friends’. Both girls were referring to physical and verbal aggression over what were often ‘stupid reasons’, where ‘it takes one second to get jumped, something happens after school or on-line’ (Sara). This follows Warrington and Younger’s (Citation2011, 154) view of exclusion and inclusion as ‘complex and elaborate processes, constantly under review, policed and renegotiated by students, both in school contexts and beyond’. Sara exemplified in her chosen image and her interview.

If you’re in the school corridor and bump into someone, their friends and your friends come and start a fight … it takes one second to get jumped, something happens after school or on-line …

It would appear from these comments that my participants not only feel they have no voice with staff who ‘protect their own’ (Peta) but also with peers who ‘just fight and get on to one another (Sara) and ‘target you all the time’ (Timmy).

Discussion and implications

As noted earlier, the research base on girls at risk of PEX is now dated, but there appears to have been very few, if any, improvements in the issues marginalised girls face with additional challenges for them, compounded by academisation, teacher recruitment and retention, austerity, school funding and marketisation (for a detailed discussion see E. Clarke Citation2023a). Girls’ lack of voice and visibility were highlighted in research two decades ago (e.g. Archer Citation2004; Lloyd Citation2005b; Munn and Lloyd Citation2005; Osler Citation2010; Osler and Vincent Citation2003; Osler et al. Citation2002) and many of the recommendations made two decades ago remain pertinent today.

Osler and Vincent (Citation2003) proposed schools should consider approaches to increase students’ voice in how the school runs, fostering ‘belonging’ (Martin-Denham Citation2021) to the school, highlighted as particularly important for girls (Porter and Ingram Citation2021). This marries well with another of their recommendations (Osler and Vincent Citation2003) which suggested approaches to support behaviour and pupils that were more democratic, focusing on systemic understanding of challenges at school, rather than maintaining beliefs that behaviour is an individual issue (Daniels, Porter, and Thompson Citation2022). In their research, Jones et al. (Citation2023, 13) highlighted how participants wanted ‘adults who listen, understand and collaborate’ and argued that focusing on ‘relational capacities’ could lead to more ‘inclusive and compassionate school cultures’. This focus on relationships can be seen from my data as beneficial for staff–girl relationships as well as girl–girl relationships and is supported by Scottish data which shows a significant reduction in PEX since policy recommended biopsychosocial, inclusive and relational approaches to supporting behaviour in schools (Kane et al. Citation2004; McCluskey et al. Citation2019).

What Cruddas and Haddock (Citation2005, 168) termed ‘friendship work’ would also seem pertinent for girls identified as at risk of PEX (and ideally long before), giving them opportunities to develop the skills to form and maintain ‘supportive’ rather than ‘sabotaging’ friendships. This could be done by revisiting elements of the Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning curriculum (SEAL) (Humphrey, Lendrum, and Wigelsworth, Citationn.d.) and the guidance in the now non-statutory PHSE curriculum (Tierney and Dowd Citation2000). This was also highlighted as potentially beneficial in Rose et al.’s (Citation2015) study of emotion coaching. This would require schools to set aside a space and place to develop these interventions which could also be supportive of Cruddas and Haddock’s (Citation2005, 168) findings that girls wanted ‘an opportunity to reflect on their emotions and have space to develop friendships and share problems with each other’. It would also begin to address some of the issues of girls’ voice and visibility giving them a ringfenced time to be heard and seen by each other and by staff while developing social and emotional skills. It may also support them more widely in using their voice in ways which are perceived as more acceptable to school cultures.

Improving girls’ voice and visibility in data and policy might be significantly easier than at school level where a range of sometimes intractable factors coalesce and present real challenges to making changes to the individual school system. Both of the mainstream schools where data were collected in this study belonged to large multi-academy trusts and had limited autonomy on school policy, including expectations around uniform, IE, sanctions and so on which were set centrally. Both schools, representative of schools more widely in England, had issues recruiting and retaining staff, resulting in serious ramifications for the girls who would have benefited from, and were advocating for teachers who ‘knew’ and ‘saw’ them and were able to listen to them. The relationships students were able to form with staff in the PRU were noted by both participants as a huge strength and significant difference to their mainstream settings.

Although in the current educational climate many schools have less autonomy than they had 20 years ago when many of the studies cited were conducted, it would seem profitable to use the opportunities they have to develop spaces and places for girls to engage in and develop SEAL and PHSE skills to support them in addressing many of the larger systemic issues that individual schools are unable to change.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Clarke Emma

After teaching in mainstream primary schools for almost 18 years, Emma Clarke now leads a primary PGCE course. Her interests include research methodologies, approaches to managing behaviour, and challenging behaviour in primary schools. Her PhD considered the tensions experienced by teaching assistants in mainstream primary schools when managing behaviour. She has presented her research nationally and internationally, as well as publishing both in books and peer-reviewed journals.

References

- Agenda. 2021. Girls at Risk of Exclusion: Girls Speak Briefing Sept 2021. https://weareagenda.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Girls-at-risk-of-exclusion-Agenda-briefing-September-2021.pdf.

- Allard, A., and J. McLeod. 2007. “Young Women “On the Margins”: Representation, Research and Politics.” In Learning from the Margins: Young Women, Social Exclusion and Education, edited by J. McLeod and A. Allard, 1–6. London: Routledge.

- Alldred, P., and V. Gillies. 2012. “The Ethics of Intention: Research As a Political Tool.” In Ethics in Qualitative Research, edited by J. Birch, M. Miller, T. Mauthner, and M. Jessop, 43–61, 2nd ed. London: Sage.

- Archer, L. 2004. “Extended Review.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 25 (1): 101–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142569032000155971.

- Archer, L., A. Halsall, and S. Hollingworth. 2007. “Class, Gender, (Hetero)sexuality and Schooling: Paradoxes within Working-Class girls’ Engagement with Education and Post-16 Aspirations.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 28 (2): 165–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425690701192570.

- Armstrong, D. 2014. “Educator Perceptions of Children Who Present with Social, Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties: A Literature Review with Implications for Recent Educational Policy in England and Internationally.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 18 (7): 731–745. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2013.823245.

- Arnot, M., and M. Mac an Ghaill. 2006. “Re)contextualising Gender Studies in Education.” In Gender and Education, edited by M. Arnot and M. M. an Ghaill, 1–15. London: Routledge.

- Bates, E., J. McCann, L. Kaye, and J. Taylor. 2017. ““Beyond words”: A researcher’s Guide to Using Photo Elicitation in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 14 (4): 459–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2017.1359352.

- Benjamin, S., M. Nind, K. Hall, and J. C. K. Sheehy. 2003. “Moments of Inclusion and Exclusion: Pupils Negotiating Classroom Contexts.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 24 (5): 547–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142569032000127125.

- Black, A. 2022. “‘But What Do the Statistics say?’ an Overview of Permanent School Exclusions in England.” Emotional & Behavioural Difficulties 27 (3): 199–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632752.2022.2091895.

- Brown, R. 2018. Mental Health and Wellbeing Provision in Schools. London: DfE.

- Carlile, A. 2008. ““Bitchy Girls and Silly boys”: Gender and Exclusion from School.” International Journal on School Disaffection 6 (2): 30–36. https://doi.org/10.18546/IJSD.06.2.05.

- Charmaz, K. 2014. Constructing Grounded Theory. 2nd ed. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Clarke, E. 2023a. Images from the Edges Girls’ Experiences of Being at Risk of Permanent Exclusion. Report Series: Learning for All. BERA: London.

- Clarke, E. 2023b. Understanding girls’ Experiences of Being at Risk of Permanent Exclusion: How Do We Get There?. London: BERA Blog.

- Clarke, G., G. Boorman, and M. Nind. 2010. “‘If They don’t Listen I Shout, and When I Shout They listen’: Hearing the Voices of Girls with Behavioural, Emotional and Social Difficulties.” British Educational Research Journal 37 (5): 765–780. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411926.2010.492850.

- Clarke, G., G. Boorman, and M. Nind. 2011. ““If They don’t Listen I Shout, and When I Shout They listen”: Hearing the Voices of Girls with Behavioural, Emotional and Social Difficulties.” British Educational Research Journal 37 (5): 765–780. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411926.2010.492850.

- Cole, T., G. McCluskey, H. Daniels, I. Thompson, and A. Tawell. 2019. “Factors Associated with High and Low Levels of School Exclusions: Comparing the English and Wider UK Experience.” Emotional & Behavioural Difficulties 24 (4): 374–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632752.2019.1628340.

- Cruddas, L., and L. Haddock. 2005. “Engaging Girls Voices: Learning As Social Practice.” InProblem Girls: Understanding and Supporting Troubled and Troublesome Girls and Young Women, edited by G. Lloyd, 161–172. London: Routledge.

- Daniels, H., J. Porter, and I. Thompson. 2022. “What Counts As Evidence in the Understanding of School Exclusion in England.” Frontiers in Education 7:1–7. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.929912.

- Department for Education. 2013. Behaviour and Discipline in Schools: Guidance for Governing Bodies. London: DfE.

- Department for Education. 2014. Mental Health and Behaviour in Schools. London: DfE.

- Department for Education. 2016. Behaviour and Discipline in Schools: Advice for Headteachers and School Staff. London: DfE.

- Department for Education. 2019a. Mental Health and Behaviour in Schools. London: DfE.

- Department for Education. 2019b. The Timpson Review of School Exclusion: Government Response. London: DfE.

- Department for Education. 2019c. Timpson Review of School Exclusions. London: DfE.

- Department for Education. 2021. Permanent Exclusions and Suspensions in England, Academic Year 2019/20. London: DfE.

- Department for Education. 2023a. Permanent Exclusions and Suspensions in England - Spring Term 21/22. London: DfE.

- Department for Education. 2023b. Secondary Accountability Measures. London: DfE.

- Done, E. J., and H. Knowler. 2020. “Painful Invisibilities: Roll Management or ‘Off-Rolling’ and Professional Identity.” British Educational Research Journal 46 (3): 516–531. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3591.

- Done, E. J., and H. Knowler. 2021. “‘Off-rolling’ and Foucault’s Art of Visibility/Invisibility: An Exploratory Study of Senior leaders’ Views of ‘Strategic’ School Exclusion in Southwest England.” British Educational Research Journal 47 (4): 1039–1055. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3709.

- Done, E. J., and H. Knowler. 2022. “Editorial.” Emotional & Behavioural Difficulties 27 (3): 181–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632752.2022.2129355.

- Education Select Committee. 2018. Forgotten Children: Alternative Provision and the Scandal of Ever Increasing Exclusions - Education Committee - House of Commons. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmeduc/342/34205.htm.

- Fazel, M., and D. Newby. 2021. “Mental Well-Being and School Exclusion: Changing the Discourse from Vulnerability to Acceptance.” Emotional & Behavioural Difficulties 26 (1): 78–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632752.2021.1898767.

- Ferguson, L. 2019. “Children at Risk of School Dropout.” In Oxford Handbook of Children and the Law (OUP 2019), edited by J. Dwyer, 635–664. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fields, J., and E. Payne. 2016. “Editorial Introduction: Gender and Sexuality Taking Up Space in Schooling.” Sex Education 16 (1): 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2016.1111078.

- Graham, B., C. White, and S. Potter. 2019. “School Exclusion : A Literature Review on the Continued Disproportionate Exclusion of Certain Children.” May, 117. London: DfE.

- Hall, S. 1990. Cultural identity and diaspora, edited by J. Rutherford. London: Lawrence and Wishart.

- Hazell, W. 2019, February 26. “Exclusive: Flattening the Grass ‘Frightening to watch’, Say New Sources.” The Times Educational Supplement.

- Hernandez-Albujar, Y. 2007. “The Symbolism of Video: Exploring Migrant Mothers’ Experiences.” InVisual Research Methods: Image, Society and Representation, edited by G. Stanczak, 281–307. London: Sage.

- Humphrey, N., A. Lendrum, and M. Wigelsworth. n.d. Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning (SEAL) Programme in Secondary Schools: National Evaluation. London: DfE.

- Jones, R., J. Kreppner, F. Marsh, and B. Hartwell. 2023. “Punitive Behaviour Management Policies and Practices in Secondary Schools: A Systematic Review of Children and Young people’s Perceptions and Experiences.” Emotional & Behavioural Difficulties 28:1–16.

- Kane, J., G. Lloyd, G. Mccluskey, S. Riddell, J. Stead, and E. Weedon. 2004. Restorative Practices in Three Scottish Councils Final Report of the Evaluation of the First Two Years of the Pilot. https://www.gov.scot/Resource/Doc/196078/0052553.pdf.

- Kohli, W., and N. Burbules. 2013. Feminism and Educational Research. London: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc.

- Kulz, C. 2018. “Race Ethnicity and Education Mapping Folk Devils Old and New Through Permanent Exclusion from London Schools.” Race Ethnicity and Education 22 (1): 93–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2018.1497961.

- Lloyd, G. 2005a. “EBD Girls” - a Critical View.” In Problem Girls: Understanding and Supporting Troubled Girls and Troublesome Women, edited by G. Lloyd, 129–146. London: Routledge.

- Lloyd, G. 2005b. “Introduction: Why We Need a Book About “Problem” Girls.” In Problem Girls: Understanding and Supporting Troubled and Troublesome Girls and Young Women, edited by G. Lloyd, 1–9. London: Routledge.

- Martin-Denham, S. 2021. “School Exclusion, Substance Misuse and Use of Weapons: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis of Interviews with Children.” Support for Learning 36 (4): 532–554. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9604.12379.

- McCluskey, G. 2008. “Exclusion from School: What Can “Included” Pupils Tell Us?” British Educational Research Journal 34 (4): 447–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920701609331.

- McCluskey, G., T. Cole, H. Daniels, I. Thompson, and A. Tawell. 2019. “Exclusion from School in Scotland and Across the UK: Contrasts and Questions.” British Educational Research Journal 45 (6): 1140–1159. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3555.

- Mills, M., and P. Thomson. 2022. “English Schooling and Little E and Big E Exclusion: What’s Equity Got to Do with It?” Emotional & Behavioural Difficulties 27 (3): 185–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632752.2022.2092273.

- Munn, P., and G. Lloyd. 2005. “Exclusion and Excluded Pupils.” British Educational Research Journal 31 (2): 205–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/0141192052000340215.

- Murphy, R. 2022. “How Children Make Sense of Their Permanent Exclusion: A Thematic Analysis from Semi-Structured Interviews.” Emotional & Behavioural Difficulties 27 (1): 43–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632752.2021.2012962.

- Nind, M., G. Boorman, and G. Clarke. 2012. “Creating Spaces to Belong: Listening to the Voice of Girls with Behavioural, Emotional and Social Difficulties Through Digital Visual and Narrative methods. International.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 16 (7): 643–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2010.495790.

- Oliffe, J. L., and J. L. Bottorff. 2007. “Further Than the Eye Can See? Photo Elicitation and Research with Men.” Qualitative Health Research 17 (6): 850–858. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732306298756.

- Ortega-Alcázar, I., and I. Dyck. 2012. “Migrant Narratives of Health and Well-Being: Challenging ‘Othering’ Processes Through Photo-Elicitation Interviews.” Critical Social Policy 32 (1): 106–125. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261018311425981.

- Osler, A. 2006. “Excluded Girls: Interpersonal, Institutional and Structural Violence in Schooling.” Gender and Education 18 (6): 571–589. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540250600980089.

- Osler, A. 2010. “Girls and Exclusion: Why Are We Overlooking the Experiences of Half of the School Population?” In Did They Get it Right? School Exclusions and Race Equality, edited by D. Weekes-Bernard, 27–29. London: Runnymede Trust.

- Osler, A., C. Street, M. Lall, and K. Vincent. 2002. Girls and Exclusion from School. https://www.jrf.org.uk/report/girls-and-exclusion-school.

- Osler, A., and K. Vincent. 2003. Girls and Exclusion: Rethinking the Agenda. London: Routledge.

- Perraudin, F. 2019, March 16. “Academy Trust Accused of Using Assemblies to Intimidate Students.” The Guardian.

- Perryman, J. 2022. Teacher Retention in an Age of Performative Accountability. London: Routledge.

- Pink, S. 2001. “More Visualising, More Methodologies: On Video, Reflexivity and Qualitative Research.” The Sociological Review 49 (4): 586–599. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-954X.00349.

- Pirrie, A., and G. Macleod. 2009. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties Locked Out: Researching Destinations and Outcomes for Pupils Excluded from Special Schools and Pupil Referral Units. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632750903073343.

- Porter, J., and J. Ingram. 2021. “Changing the Exclusionary Practices of Mainstream Secondary Schools: The Experience of Girls with SEND. ‘I Have Some Quirky Bits About Me That I Mostly Hide from the World.” Emotional & Behavioural Difficulties 26 (1): 60–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632752.2021.1900999.

- Ringrose, J. 2007. “Successful Girls? Complicating Post‐Feminist, Neoliberal Discourses of Educational Achievement and Gender Equality.” Gender and Education 19 (4): 471–489. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540250701442666.

- Rose, J., L. McGuire-Snieckus, and R. Gilbert. 2015. “Emotion Coaching - A Strategy for Promoting Behavioural Self-Regulation in Children/Young People in Schools: A Pilot Study.” European Journal of Social & Behavioural Sciences 13 (2): 1766–1790. https://doi.org/10.15405/ejsbs.159.

- Russell, L., and P. Thomson. 2011. “Girls and Gender in Alternative Education Provision.” Ethnography and Education 6 (3): 293–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457823.2011.610581.

- Social Finance. 2020. Maximising Access to Education: Who’s at Risk of Exclusion?. London: Social Finance Ltd.

- Tejerina-Arreal, M., C. Parker, A. Paget, W. Henley, S. Logan, A. Emond, and T. Ford. 2020. “Child and Adolescent Mental Health Trajectories in Relation to Exclusion from School from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children.” Child and Adolescent Mental Health 25 (4): 217–223. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12367.

- Thompson, I., A. Tawell, and H. Daniels. 2021. “Conflicts in Professional Concern and the Exclusion of Pupils with SEMH in England.” Emotional & Behavioural Difficulties 26 (1): 31–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632752.2021.1898769.

- Tierney, T., and R. Dowd. 2000. “The Use of Social Skills Groups to Support Girls with Emotional Difficulties in Secondary Schools.” Support for Learning 15 (2): 82–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9604.00151.

- Warrington, M., and M. Younger. 2011. “‘Life Is a tightrope’: Reflections on Peer Group Inclusion and Exclusion Amongst Adolescent Girls and Boys.” Gender and Education 23 (2): 153–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540251003674121.

- Whitehouse, M. 2022. “Illegal School Exclusion in English Education Policy.” Emotional & Behavioural Difficulties 27 (3): 220–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632752.2022.2092274.

- Wright, C., D. Weekes, and A. McGlaughlin. 2000. “Race”, Class and Gender in Exclusion from School. London: Falmer Press.