ABSTRACT

Worldwide, educational policies increasingly focus on students’ intercultural competency development (ICD). But educational institutions struggle with its implementation due to difficulties concerning 1) explicating educational goals for ICD and 2) developing teaching, learning and assessment activities that foster this development. The paper describes the development of the Rubric ICD and two interlinked studies aimed to explore how this tool can help to explicate intercultural competence development in (higher) vocational curricula in the Netherlands. The first study, combining five teacher group interviews (n = 15), explores how the Rubric ICD helps to identify challenges and possibilities for explicitly integrating ICD in vocational curricula. The second study, involving 116 students going on international internships, examines if the Rubric ICD helps to explicate and examine students’ thinking about ICD before and after their international internships. The studies showed that ICD is still mostly implicit in vocational curricula and students’ learning. The Rubric ICD was found helpful for explicating ICD in various elements of vocational curricula and for reflecting on and coaching students’ intercultural learning. The studies also revealed that teachers’ professional development regarding ICD is needed and that the Rubric ICD could be helpful in that respect as well.

Introduction

Worldwide, increased attention is paid to students’ intercultural competencies. Intercultural competence is seen as a ‘21st century skill’, which refers to a broad set of knowledge, skills, work habits, and character traits that are believed to be key success factors in today’s world (Ananiadou and Claro Citation2009). Global organisations like UNESCO and the OECD are addressing the importance of intercultural competence for all people and for education in specific (OECD Citation2016). The increased diversity of societies and the globalisation of economies, require from employees and citizens to be able to show effective and appropriate behaviour and communication in intercultural situations by developing targeted knowledge, skills and attitudes (Deardorff Citation2006).

Given its importance in today’s society, workplaces and internship places stress the importance of intercultural working (MacDonald, O’Regan, and Witana Citation2009), in some countries intercultural competence is incorporated in national qualification profiles (MacDonald, O’Regan, and Witana Citation2009), and educational institutions have incorporated intercultural competence development as a focal point of their education. At the same time, institutions struggle with the actual implementation due to difficulties concerning 1) explicating educational goals with respect to the ambiguous and multifaceted concept of intercultural competence and 2) developing teaching, learning and assessment activities and pedagogies that foster its development (Popov, Brinkman, and van Oudenhoven Citation2017; Deardorff Citation2015).

To start with the first, there are multiple terms for ‘intercultural competence’ that are often used interchangeably, like ‘global competence’ or ‘cross-cultural competence’, accompanied by different definitions and the identification of different component skills, like behavioural flexibility, communicative awareness, and empathy among others (MacDonald, O’Regan, and Witana Citation2009). This diversity and ambiguity regarding the concept of intercultural competence leaves education with a challenging assignment. A recent literature review (Popov, Brinkman, and van Oudenhoven Citation2017) shows that education institutions struggle with translating the ambiguous concept into explicit learning objectives. Regarding the second difficulty, teaching, learning and assessment activities explicitly stimulating students’ intercultural competence development are lacking as well (Popov, Brinkman, and van Oudenhoven Citation2017; Cornelius and Stevenson Citation2018; Vande Berg, Paige, and Hemming Lou Citation2012). These studies show that merely providing students with international experiences, like international internships or study abroad, is not enough to foster intercultural competence development. Exposing students to these kinds of experiences without proper preparation can even have negative learning effects (Trede, Bowles, and Bridges Citation2013). Preparation requires explicit goal setting, coaching and reflection before, during and after intercultural experiences. The question remains how intercultural competence development can be operationalised in education programmes in terms of learning objective, teaching, learning and assessment activities resulting in fostering students’ intercultural competence development (Vande Berg, Paige, and Hemming Lou Citation2012). Our study aims to operationalise intercultural competence development in various elements of vocational curricula in the Netherlands by using a rubric for teacher discussions and analysis of students’ intercultural learning experiences.

Research questions related to this overall aim are: (1) how is ICD currently embedded in (higher) vocational curricula, (2) how can the Rubric ICD help to make ICD more explicit in various elements of vocational curricula, (3) in what way does the rubric ICD help to identify students’ intercultural learning experiences before and after going on international internships? The next sections first describe the practical and theoretical rationales behind this study. The practical rationale originates from Dutch vocational education policy and practices showing the relevance of this explorative study. In the theoretical section, we elaborate on several challenges for operationalising intercultural competence development (ICD) in vocational curricula. Building on the practical and theoretical perspectives, we finally delineate how we created the Rubric ICD as an instrument to help grasping and explicating intercultural learning in vocational curricula. This rubric was the starting point for two interlinked explorative studies. A qualitative study among teachers using the Rubric ICD to illuminate the problems with and possibilities for explicitly integrating ICD in various elements of (higher) vocational curricula (study 1). A cross-sectional study uses the rubric ICD as a tool for students to explicate their intercultural experiences before and after an international internship. (study 2).

Dutch vocational education as a study context

Dutch vocational education in this context refers to (1) senior secondary vocational education educating students of about 16 to 20 years old for specific occupations (e.g. educational assistant, florist) at the EQF level 4, and (2) higher vocational education, also referred to as universities of applied sciences (De Bruijn, De, Billett, and Onstenk Citation2017), educating students of about 17 to 23 years for certain occupational fields (e.g applied biology, facility management) at EQF level 6. Both types of vocational education are characterised by educating students for competent performance of core occupational tasks, in contrast to a higher, academic education that firstly aims at developing academic thinking and research skills.

This study originates from several developments that recently took place in the Netherlands in the context of vocational education. First, the increase of societal problems that are related to differences in cultures (e.g., the inflow of refugees and immigrants, increase in a number of terroristic attacks, etc.). Second, the advice of the Dutch Council of Education to pay more, explicit, and structural attention to the development of graduates who are internationally competent (Dutch Education Council Citation2016). Third, an increase in explicit attention and additional funding from the Ministry of Education for the internationalisation of vocational education. For example, from 2015 onwards, the ministry has been providing additional funding for vocational students to go on internship or study abroad. Fourth, since August 2016 ICD has been incorporated in the national qualification profiles for senior secondary vocational education, obliging vocational institutions to incorporate ICD in their curricula. These developments make the question of how ICD can be operationalised in educational curricula even more pressing and relevant.

Theoretical framework

Deardorff (Citation2011, Citation2015) has done extensive research on intercultural competence development and identified several challenges in this field, including the absence of consensus on the terminology around intercultural competence (IC), how to foster the process of developing IC and related issues concerning the assessment of IC. These challenges hamper operationalising ICD in educational curricula. We build on these three main challenges to elaborate five theoretical underpinnings for the development of our Rubric ICD as a tool to help explicating ICD in vocational curricula. First, the numerous definitions of intercultural competence, as identified in Deardorffs first challenge, are generally too vague and abstract to guide instruction, teaching, or assessment. This makes operationalising IC in educational curricula difficult. In this respect, Deardorff (Citation2015) questions if we should be looking for one accepted definition of IC, implying that this defines what, and to what level, all student should be developing. She suggests to embrace a developmental perspective on IC that views ICD as a process that differs per person and his/her type, extent and quality of engagement with different cultures. Hammer (Citation2015) aligns with this perspective, describing ICD as a developmental process that is never finished and differs depending on the kinds of intercultural experiences of a student and the way this student uses these experience to learn and develop. Second, the process of developing ICD requires experiential learning in a variety of intercultural situations (such as study abroad, service learning, and so on) as this type of learning is critical for ICD (Yamazaki and Kayes Citation2004). Thus, educational programmes should offer ample opportunities for this type of learning. Third, ICD will not happen by experiential learning alone. It requires explicit reflection on intercultural experiences in the light of a students’ own learning goals (e.g. Jackson Citation2015; Vande Berg, Paige, and Hemming Lou Citation2012) which in turn requires educational institutions to optimise the guidance and coaching of students’ individual intercultural competence development (Deardorff Citation2011). Fourth, to foster intercultural competence development, or any other kind of competence for that matter (see, for example, entrepreneurial competence; Kamovich and Foss Citation2017), a strong alignment of teaching, learning and assessment for intercultural competence is required (Biggs Citation1996). Only paying attention to intercultural competencies in one or two of these areas might hamper students’ ICD (Trede, Bowles, and Bridges Citation2013). Fifth, definitions or models of ICD increasingly include behaviour or attitude related elements (Matsumoto and Hwang Citation2013; Perry and Southwell Citation2011), like adapting and adjusting to a variety of intercultural situations. However, initiatives incorporating ICD in educational curricula mainly operationalise ICD in cognitive outcomes, such as the mastery of cultural information, and assess them by self-report questionnaires (Matsumoto and Hwang Citation2013; McGury, Shallenberger, and Tolliver Citation2008). These initiatives mostly take place in higher, academic, education in which cognitive development is often the main focus. In vocational education, which is the context of this study, much more emphasis is placed on competent performance in authentic, real-life and professional situations (De Bruijn, De, Billett, and Onstenk Citation2017), including intercultural behaviour that is expected in VET internships or future workplaces (MacDonald, O’Regan, and Witana Citation2009)

Considering these challenges, we argue that a rubric could be a suitable tool to help explicating ICD in various aspects of vocational curricula and the challenges going along with making ICD an explicit part of their educational programmes (Tractenberg and FitzGerald Citation2011). The following section will elaborate on the features of the rubric that was used in our studies.

The rubric intercultural competence development (ICD)

A rubric is an instrument that clearly articulates performance expectations and proficiency levels. When designed properly (Dawson Citation2017) it allows for defining learning goals at curriculum level as well as individual student level, or for designing learning tasks and assessment tasks at different levels (e.g., throughout a curriculum). It can describe multiple facets of intercultural competence in observable and interactive behaviour and thereby offers ample opportunities for qualitative feedback, coaching, reflection on and assessment of individual students’ experiences (Gulikers and Oonk Citation2019). As such, a rubric fits a developmental, performance-oriented perspective on ICD. Our Rubric ICD is built on previous research on rubrics in ICD – mostly guided by the work of McGury, Shallenberger, and Tolliver (Citation2008) – and input from the national qualification framework used in Dutch vocational education. From 2016 onwards, this national qualification framework explicitly incorporates intercultural objectives regarding: 1) ‘researching own and others’ culture’; 2) ‘researching own intercultural sensitivity’; 3) ‘making and maintaining contacts with other people from other cultures, and 4) ‘working together with other cultures’ (www.kwalificatiesmbo.nl). For the purpose of developing a tool that is most likely to foster critical reflection on ICD operationalisation in education curricula, alignment to these national requirements was crucial. Moreover, the rubric categories should describe observable behaviour and be understandable for both senior secondary and higher vocational students as well as their teachers. This is different from most IC rubrics developed previously which were mainly developed in the context of higher, academic education (Deardorff Citation2006; Perry and Southwell Citation2011).

McGury and colleagues’ (Citation2008) work was chosen to guide our study as they also stress actual intercultural behaviour instead of cognitions. They describe six competence domains relevant for intercultural competence, that is 1) cultural difference; 2) personal identity; 3) global citizenship; 4) perspective; 5) globalisation, and 6) transferability. For these six domains, they have developed rubrics describing intercultural behaviour. Three of these six domains were in line with the requirements of the Dutch qualification framework for vocational education: cultural difference, personal identity and perspective. The other three domains were not referred to in this qualification framework, described more thinking/reasoning processes than intercultural behaviour, and seemed to connect more to a higher, more academic level of education. We decided to not include these three domains as we wanted to develop a rubric that was describing intercultural behaviour and directly recognisable for teachers, also VET teachers, in terms of the qualification profile. Cultural difference is about the extent to which the student is willing to learn about, is open to and actively creates opportunities for learning from other cultures. Personal identity relates to using interpersonal encounters, either with people whose culture is very different or similar to one’s own, to try to understand oneself and one’s reactions in these situations. This competence relates to the observation that one’s sense of self and identity is often more fully understood and refined in interaction with others. The perspective competence is about the ability to understand a situation through the lens of a person with a different culture, worldview, values and perspective. It is about empathy in the fullest sense, and relies on openness to other ways of being and knowing (McGury, Shallenberger, and Tolliver Citation2008).

The operationalisations of McGury and colleagues were used to develop performance indicators and proficiency levels in terms of observable behaviour for the four core tasks of the national qualification profile (See ).

Table 1. Justification of the Rubric Performance Indicators

This resulted in a first version of the rubric ICD with seven performance indicators described at four proficiency levels. This version was discussed with a group of seven international internship coordinators working in one higher and six senior secondary vocational education institutions to validate if this version 1) was understandable and 2) reflected their ideas of what ICD in vocational education and during international internships should be about and as a result could be useful for reflecting on ICD in vocational curricula with teachers and students. It was concluded that indeed the rubric was understandable and had the potential to help explicating and coaching intercultural competence development. The only changes made were some slight rephrasing of several words and the deletion of the lowest proficiency level. Participants felt this described such a minimal level that it was not meaningful to include. The final rubric described seven performance indicators described at three proficiency levels (A-B-C) (see for an example).

Table 2. Example of Rubric

Study 1: the utility of the Rubric ICD for explicating ICD in vocational curricula

This study addressed the first two research questions: 1) How is ICD currently embedded in (higher) vocational curricula and (2) how can the Rubric ICD help to make ICD more explicit in various elements of vocational curricula.

Methodology

Participants

Five focus group meetings with in total 18 teachers and international internship coordinators from nine senior secondary and higher vocational education were undertaken. One focus group consisted of eight teachers and/or international internship coordinators of five different educational institutions and one representative of the Council of Vocational Education (from now on called the ‘mixed-group meeting’). The other four focus groups consisted of teachers and international internship coordinators from the same institution: One senior secondary vocational institution for life sciences (n = 2) and one for hospitality (n = 3); one higher vocational institutions for international business (n = 2) and one for management and international development studies (n = 3).

Instruments

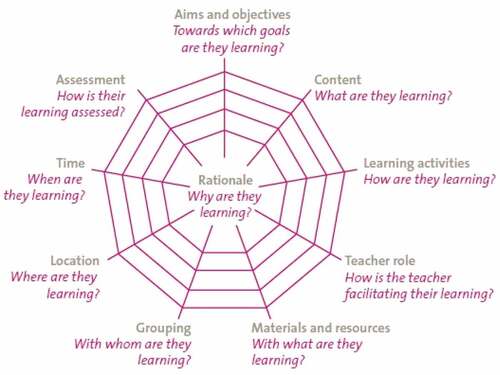

The focus groups were semi-structured, using two tools: first, the ‘Curricular Spiderweb’ of van den Akker (Citation2003) was used to explore how ICD is currently embedded in vocational curricula (question 1). The curricular spiderweb is a model that describes 10 critical elements of a curriculum () and is thereby a helpful model to structure the interviews and afterwards the data to answer research question 1. We examined how ICD was addressed in the 10 aspects of curricula: Rationale or vision (why are we learning?), learning objective, content, learning activities, learning material, a grouping of students, location, assessment, time, and student/teacher roles. Then, the rubric ICD was introduced in the focus groups to explore how this tool can help to make ICD more explicit in these curricular aspects (research question 2).

Figure 1. The curricular spider web (Van den Akker Citation2003)

In the mixed-group meeting also quantitative data were collected, next to the qualitative focus group data, concerning the perceived usefulness of the Rubric for explicating ICD in teaching, learning and assessment (question 2). A short evaluation questionnaire asked participants individually to rate the usefulness of the Rubric ICD for (1) explicating and discussing the meaning of ICD at school and teacher team level; for (2) coaching ICD in (a) international internship experiences; (b) study abroad, and (c) intercultural experiences at home; for (3) coaching ICD (a) before; (b) during, and (3) after intercultural experiences, and for (4) assessing ICD (a) formatively and (b) summatively. These questions were scored on a three-point scale (Yes!; ‘Yes, but’, and ‘No’) and could all be elaborated with additional qualitative remarks.

Data analysis

All five focus group meetings were audiotaped. Additionally, the researchers independently made notes during the meetings that they combined into detailed minutes immediately after the meetings. The minutes were sent to all participants for a member check for refining, elaborating or adjusting. Per meeting, the findings were clustered in themes that were, in turn, linked to the aspects of the curricular spider web (, question 1) or participants’ perceived use of the rubric ICD for explicating ICD in their teaching, learning, and assessment (question 2). This clustering was first done by two researchers independently and in a collaborative discussion combined into final agreed-upon documents per focus group meeting and across meetings (Miles and Huberman Citation1994). Aspects mentioned at least in three of the five interviews were taken up as typifying themes in the final summary, in which statements from individual interviews were kept as well to support the final findings.

Frequency scores one the usefulness of the Rubric ICD were counted from the quantitative evaluation questionnaire and supported by individual qualitative remarks (question 2).

Results

This section first addresses how ICD is currently addressed in the curricula and, secondly, if and how the rubric ICD can help to operationalise ICD more explicitly in vocational curricula structured along with the aspects of the curricula spider web. The main themes, that also refer to aspects of the curricula spider web, are in italic.

How is ICD embedded in (higher) vocational curricula?

All participants of the mixed-group meeting univocally reported that within their institution, intercultural development did not yet have an explicit place in their curricula and that it was not yet institutionalised. All participants reported a huge increase in attention to this topic within their institutional vision and a stronger focus on international internships (i.e., learning activities/location). This was shown, for example, in the appointment of ‘internationalisation coordinators’ with the task to operationalise the increased focus on internationalisation and interculturalisation in the curricula. Not one of the participants reported to be aware of explicit learning objectives for ICD nor explicit coaching or assessment of ICD.

The findings from the four school-based focus groups were more or less in line with the findings from the mixed-group meeting. More specifically, three of the four educational institutions (being the two senior secondary vocational institutions and one higher vocational institution) had no official vision or policy for ICD. Above that, when asked during the interview, participants were unable to explicate a clear vision on why and what they want to achieve with respect to intercultural development and how to accomplish that.

Only one of the higher education institutions had officially documented the desired learning objectives of ICD education. This set of learning objectives was developed in response to a previous visit from the Accrediting Body that evaluated this school’s learning objectives on this topic as insufficient. The other institutions could not hand over or explicate clear and shared learning objectives for intercultural development. They were all implicit and ‘in the heads of individual teachers’.

Attention for ICD was ‘scattered’ in the educational trajectories. Both higher vocational education institutions indicated that although at several points in the curriculum attention was being paid to intercultural competencies via learning activities or internships, structured and continuous attention to the topic was missing (no continuous learning paths). Moreover, ICD was no explicit part of any kind of assessment in all four institutions, also in the institution that had explicit learning objectives for ICD. The senior secondary vocational institutions argued that this was mainly due to the fact that, until now, intercultural competence development had never been an aspect of the national qualification framework. Until August 2016, schools were not obliged to pay attention to it, neither would they be reviewed by an external body on this issue. Corroborating the mixed-group findings, all four school-based interviews showed that the attention for and coaching of ICD before, during and after international experiences was very much dependent on the teacher or coach involved. The coaching sessions that were put in place were most often individual meetings (i.e., a student with his/her mentor) and paid most attention to practical internship issues.

With respect to student and teacher roles, all five focus groups interviews illuminated teacher professional development to be the most important first step towards more ICD in the curriculum. An international coordinator from one senior secondary vocational institution said:

when I ask individual teachers how they address ICD in their courses they really have no clue. They cannot articulate an understanding of ICD, don’t see it as their responsibility, or feel not capable of discussing ICD related issues with their students.

To get teachers and students more involved, a theme that came out of the interviews was the importance of linking ICD to the specific vocational context and content of the students and teachers (e.g. animal studies or hospitality). Participants argued that teachers and students in vocational education have a passion for their specific profession and internationalisation activities should be linked to that. For example, what do you learn about how farmers in Spain handle their animals compared to how we do that here at home?

A final theme that came up in all interviews related to where and when in the curriculum ICD should be placed? This related to the content, teacher role, and time aspects of van den Akker (Citation2003). All interviews paid attention to questions like: Who should be responsible for coaching and stimulating reflection on ICD? Should this be an integral part of all classes, courses and study years, and thus of all teachers, or should there be a specific course/mentoring trajectory that pays attention to this and thus be the responsibility of one mentor/coach? And when and how much time should be devoted to this issue? Should it already be addressed in the first year or left to the time when students go on international internship or study abroad? In all interviews, teachers felt that ICD should not be limited to the context of international experiences, but also linked to ‘interculturalisation at home’:

‘in current society, we are confronted with intercultural issues every day in the news. Think about refugee problems or all the terrorist attacks, shouldn’t we be discussing these issues in our classes on a regular basis?’ (teacher, senior secondary vocational institutions)

How can the rubric ICD help explicating ICD in the curriculum?

reports the mixed-group participants’ evaluations of the usefulness of the Rubric ICD for various purposes. Apart from the summative assessment purpose, they felt the tool to be valuable for all the other evaluated purposes.

Table 3. Evaluation and Frequencies of the Usefulness of the Rubric ICD for Various Educational Purposes

The five focus group meetings resulted in various ideas concerning the usefulness of the rubric ICD for explicating ICD in the curriculum. These ideas were also related to the van den Akker (Citation2003) curriculum aspects and can be found in . The table shows that all the curriculum aspects of the curricular spiderweb are touched upon to a more or lesser extent, suggesting that the rubric ICD helps to explicate the role and relevance of ICD in various aspects of the curriculum.

Table 4. Ideas on how to use the Rubric ICD in the curriculum

In the end all interviewees perceived the rubric as very helpful for teacher professional development. The rubric is now primarily focused on students. However, participants argued that it should first be used as teacher professional development instrument. Teachers currently have too little idea of what intercultural competencies are and how they should be addressed and reflected on in vocational curricula. A representative quote of one of the international coordinators of a senior secondary vocational institution was: ‘our teachers have not yet developed practical knowledge and resulting teaching strategies for dealing with intercultural situations and competency development.’

Conclusion

In conclusion, study 1 showed that ICD is still largely implicit in (higher) vocational curricula (research question 1). There is a dearth of explicit learning activities, coaching and assessment of ICD, even in the institution that has explicit ICD learning objectives. Teachers are lacking vocabulary to explicitly address ICD in learning, coaching, a reflection of assessment activities and it is unclear who is responsible for ICD teaching and coaching. The combination of curricular spiderweb and the Rubric ICD during the interviews helped to structurally visit all curricular aspects in relation to ICD. These instruments helped to give words to implicit knowledge or to wishes concerning ICD in the curricula. Participants felt that the Rubric ICD was a useful tool in making ICD more explicit in various elements of their curricula like vision, learning goals, formative assessments, coaching sessions (before, during and after international experiences) and that it might help students to reflect on their intercultural experiences (research question 2). All participants perceived this to be critical first steps towards stimulating students to develop this intercultural competencies. Only with respect to using the Rubric for summative purposes, the participants were still ambiguous. A final, but the important result of this study was that all participants felt the Rubric ICD should first be used for teacher professional development purposes, as a prerequisite for embedding ICD more in their curricula.

Study 2: the rubric ICD in practice: explicating students’ learning experiences regarding ICD

The previous study showed that the Rubric ICD helped teachers to make ICD in their vocational curriculum more explicit. The aim of this last study is to answer the third research question: in what way does the rubric ICD help to explicate and typify vocational students’ intercultural learning experiences before and after going on international internships? If the rubric can offer some insights in how the students think about their intercultural experiences and what they learned from it, this can help teachers and educators to more explicitly prepare and coach individual students to learn from intercultural experiences (See quote Bennett Citation2004).

After years of observing all Kinds of people dealing (or not) with cross-cultural situations, I decided to try to make sense of what was heppening to them. I wanted to explain why some people seemed to get a lot better at communicating across cultural boundaries while other people didn’t improve at all, and I thought that if I were able to explain why this happened, trainers and educators could do a better job of preparing people for cross-cultural encounters.

Bennett (Citation2004, 62)

The Rubric ICD was used to let students formulate learning goals before going abroad and arguments for their development after coming back.

Methodology

Participants

A total of 116 students from two higher vocational higher education institutions and three senior secondary vocational institutions participated by filling in the rubric before and after going on an international internship. shows the kind of internships and countries of the students.

Table 5. Number and Distribution of Students who Filled in the Rubric

In all five participating educational institutions ICD was prioritised but implicitly present in the curriculum, comparable to the situation reported in study 2. There were no explicit ICD learning objectives, coaching activities, reflection sessions or assessments. All students had an ‘international internship coach’ but how they understood and fulfilled their job was up to the respective coach.

Instruments

Two versions of the Rubric ICD were developed: A learning goal version to be filled in before going on international internship and an argumentation version to be filled in after coming back from the international internship. Students assessed themselves on all seven performance indicators using the proficiency levels and either described a learning goal per indicator (before) or provide a specific example of their intercultural experience as an argument for their proficiency level (afterwards) (See ).

Data analysis

While we collected both quantitative (proficiency levels) and qualitative data (i.e. the learning goals and arguments), the main analyses focused on the qualitative data. Ticking of a proficiency level was a means to the end of stimulating students’ thinking about learning goals and arguments. The qualitative data were entered in Excel and displayed per student group, per educational level, and per time slot (before or after internship).

The qualitative data were analysed along with the following steps: The three authors first independently reviewed students’ answers (i.e. their learning goals and arguments together) using open coding to identify trends in these answers. After that, they compared their findings and together developed a list of characteristics typifying students’ answers (i.e. learning goals and arguments). This resulted in a list of seven characteristics. A second reflection session amongst the researchers was required to link the characteristics to existing research and theory on intercultural competence development. This session aimed to develop both theory and data-grounded themes that could be instrumental for teachers to more optimally coach students in the context of their international internship (i.e., before, during and after their internship). This second session resulted in clustering the seven characteristics into three dimensions that could typify students current thinking about ICD.

Results

The research question asked how the Rubric ICD stimulated students to explicate their thinking about ICD before and after going on an international internship, and by means of what characteristics this thinking can be typified. This section first describes some general observations regarding how the rubric stimulated students to explicate their thinking. Then, we dig deeper into salient variations that were found in students’ answers.

General observations

The degree to which the seven performance indicators of the rubric stimulated reflection differed. For instance, the indicator ‘explores own personal convictions and shows the ability to draw the line’ yielded more specific examples than indicator ‘identifies different perspectives and identifies own perspective’ (see ).

The answers differed between groups of students across and within the educational level. This might be due to the way students were prepared, as this differed across student groups, depending on their respective teacher/coach. The answers of students from senior secondary vocational education, overall, were less concrete and elaborate than those of students from higher vocational education. However, the learning goals of students from institution B, who all went to Ethiopia (see ), were overall more specific than the learning goals of students from the other two secondary vocational education institutions.

The data suggest that the more differences between the mother- and host-culture, the more reflection on intercultural competence was generated, reflected in students providing a higher number and more specific learning experiences and arguments in their post-internship-rubric.

Dimensions describing students’ thinking about ICD

The collaborative analyses of students’ answers suggested that students were not used to explicating learning goals and arguments regarding ICD. Many of their learning goals were shallow, not specific, not concrete, not action directed and their argumentations were mostly not linked to concrete experiences showing their competency level. However, students’ answers could be distinguished by means of dimensions that are also recognised in theoretical perspectives on ICD: the extent to which students’ learning goals and arguments were specific, profound, and ethnorelative. shows specific student responses that reflect both sides of the dimensions.

Table 6. Examples of Student Responses on the Three Dimensions

Specificity

Students differed in the degree to which they were specific in describing the learning goals or arguments, rather than using generic words and expressions. Generic answers used expressions like ‘I want to understand the other culture’ or ‘learn more about the culture’, versus answers that specified what activities students report to undertake to get a better understanding of the host culture or which aspects of the host culture they are specifically interested in (see ). A recent literature research reveals that the formulation of specific learning goals by students is an important factor contributing to more effective international mobility programmes (Popov, Brinkman, and van Oudenhoven Citation2017). Therefore, the first dimension is called ‘specificity’.

Profoundness

In students’ answers, we saw a salient variation on the aspects students used to describe their intercultural experiences. Some students mainly used surface characteristics to describe their learning goals or experiences. They described visible symbols like food, clothes, appearance or rituals like greetings, festivals, or sport activities. Other students also referred to invisible aspects by describing underlying norms or values. This finding relates to the visible and invisible aspects of a culture as described in the well-known iceberg model (Oberg Citation1960) or the ‘onion’ model described by Hofstede, Hofstede, and Minkov (Citation2010). In line with these theoretical models, the second dimension identified in students’ answers is called ‘profoundness’. This dimension relates to the profoundness of students’ thinking about intercultural experiences shown in the use of visible and/or invisible cultural aspects reported in students’ answers.

Ethnorelativism

A third variation found in students’ answers was the degree to which students saw the other culture as interesting, positive and something to learn from versus something that is difficult, negative, not relevant or to be ignored. This dimension closely links to Bennetts Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity (Citation1993, Citation2004) which makes a distinction between people with a more ethnocentric attitude versus people with a more ethnorelative attitude. This third dimension found in students’ answers was called ‘ethnorelativism’. This dimension is about whether the learning goals and described experiences reflect a negative or passive attitude, not geared towards new learning experiences, or a positive and active attitude, geared towards the recognising and understanding of the host and own culture and wanting to learn from it.

Conclusion

This second study aimed to examine if and how the rubric ICD helped the student to explicate their ICD development before and after returning from international internships. This study showed that the Rubric ICD helped the students to explicate learning goals and arguments for their ICD and that this differed per performance indicator, host country and institution, probably depending on the level of preparation offered by this institution. While many learning goals and arguments were shallow, vague and not concrete, showing that students were not used to explicate their intercultural learning, the answers elicited by the rubric allowed to identify differences in students’ thinking about their ICD in terms of specificity profoundness and ethnorelativism.

Discussion

The political and societal context led all vocational institutions participating in our study to have intercultural development high on their agendas. But implementing this into their curricula is fraught with difficulties. Our studies aimed to explore these difficulties and identify if and how the Rubric ICD can help vocational institutions to make ICD more explicit in their curricula. Our first study disclosed that the operationalisation of intercultural development within their curriculum was highly implicit and that alignment in the different elements of the curricular spider web was largely missing. Even the institution with explicit ICD learning objectives was unable yet to translate these into explicit teaching, learning and assessment activities. In all teacher meetings the importance of using the rubric for teacher professional development was stressed, as the participants revealed that many teachers have not yet developed practical knowledge (Verloop, Van Driel, and Meijer Citation2001) of what this ICD actually means in their own teaching practice (De Bruijn and Leeman Citation2011; Windschitl Citation2002).

Our second study supported the assumption that the Rubric ICD could help students to explicate their learning goals and arguments for their ICD. As intercultural competence development was still so implicit in most institutions in our study, students were not focused nor coached on developing intercultural competencies during intercultural experiences. This very likely influenced the answers we found with respect to students’ reported learning goals and arguments. This is opposite to, for example, the results of Cornelius and Stevenson (Citation2018) investigating trainee vocational educators’ learning and experienced boundaries during international online collaboration. The Finnish and Scottish participants reported on valuable sociocultural learning experiences, because assignments about this aspect were incorporated in the research project.

The data-driven dimensions of specificity, profoundness and ethnorelativism that we identified in the rubrics that students filled in could be grounded in leading theories about intercultural competence development (e.g., Popov, Brinkman, and van Oudenhoven Citation2017; Bennett Citation1993; Hofstede, Hofstede, and Minkov Citation2010). We argue that these dimensions can give teachers a lens for reflecting on students’ reported intercultural experiences and in turn help teachers to more explicitly coach students’ intercultural competence development within the zone of proximal development (see quote Bennett Citation2004): teachers can assist in making the learning goals and arguments more specific, facilitate reflection on the deeper levels of the goals and arguments (what are underlying norms and values) and/or start a discussion about ethnocentrism or ethnorelativism.

In conclusion, the Rubric ICD and the three dimensions seems to offer a vocabulary for both teachers and students, and ample opportunities for more conscious and deeper discussions and reflections on ICD. Actually, a preliminary finding of a follow-up pilot project in which we used the rubric ICD to guide students’ reflection on intercultural experiences, instead of using a more general reflection format (i.e., ‘describe what you learned from being in and working with other cultures’), resulted in significantly more specific reflections on their intercultural learning with a trend of being more profound and more ethnorelative (Fortuin and Brinkman Citation2017).

The findings of these studies are limited by some issues: the participating institutions varied with respect to various variables like their level and field of education, there was a great variation in internships of the students (different countries, length of stay, type of activities, etc.), and the pre-departure instructions varied per institution. Moreover, the Rubric ICD is developed to fit the Dutch VET context and qualification framework, and as such, we will not argue that this instrument fully and reliably covers the whole spectrum of intercultural competencies. However, this study is explorative in nature and meant to help Dutch (higher)VET institutions to critically think about ICD in their curricula. This study shows that the generic Rubric ICD, in the sense that its performance indicators are not geared towards a specific disciplinary or vocational content, can successfully fulfil this function for a variety of (higher) vocational institutions.

Practical implications and further research

While we felt the generic nature of the rubric was a positive aspect of the tool, the vocational teachers in our study stressed the importance of linking the generic intercultural performance indicators to specific discipline- or vocation-oriented content. So for example, what kind of cultural boundaries can you be confronted with when working with animals in another country (e.g., addressing the different ways that animals are treated in different countries)? By doing this, both teachers and students might realise the importance of and feel more responsible for intercultural competence development. This might be an important suggestions as the issue of ‘ who is responsible for ICD’ was raised in all teacher meetings (study 1). Interesting future studies would be to evaluate the effectiveness of the more generic rubric versus a more vocationally contextualised rubric for coaching and stimulating students’ intercultural learning.

Another suggestion by the participants was that optimal use of the Rubric ICD in the teaching and learning process first requires teacher professional development. Using the current generic Rubric ICD as a template and developing more contextualised versions together with teachers, and possibly students, might be a crucial professional development activity for vocational teachers and students to develop shared understanding and vocabulary.

The Rubric ICD was initially developed and used by students in the context of international internships. The participating teachers and international coordinators, however, saw multiple opportunities for using the Rubric ICD for other than international internship experiences, like study abroad and internationalisation at home. While perhaps not one-on-one translatable to every other educational or occupational context, we feel that both the Rubric ICD and the resulting dimensions, which differentiate students’ learning goals and arguments, can stimulate the reflection of teachers or curriculum development teams in other educational institutions struggling with operationalising and coaching ICD.

Interesting other avenues for future research would be to study if using the Rubric ICD indeed makes intercultural learning more explicit for both students and teachers: does the Rubric ICD offer vocational teachers more handles to explicitly coach students ICD before, during and after intercultural experiences? And 2) does this result in more conscious intercultural competence development of students with more specific, profound and ethnorelative learning goals and arguments?

Finally, it was encouraging to experience the enthusiasm with which the Rubric ICD and discussions were taken up in this study. However, this does not guarantee an actual uptake by educational institutions, let alone, a sustainable change in the vocational curricula with respect to intercultural competence development. Research on the actual effects of using the Rubric ICD for teacher professional development and student coaching would bring us a step closer towards sustainably changing educational practices towards incorporating intercultural competence development into 21st century proof vocational curricula. The current political and social climate certainly call for this.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Akker, J. V. D. 2003. “Curriculum Perspectives: An Introduction.” In Curriculum Landscapes and Trends, edited by J. van Den Akker, W. Kuiper, and U. Hameyer, 1–10. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Ananiadou, K., and M. Claro 2009. “21st Century Skills and Competences for New Millennium Learners in OECD Countries.” OECD Education Working Papers, No. 41, OECD Publishing.

- Bennett, M. J. 1993. “Towards Ethnorelativism: A Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity.” In Education for the Intercultural Experience 2nd ed, edited by R. M. Paige, 21–71. Yarmouth, ME: Intercultural Press.

- Bennett, M. J. 2004. “Becoming Interculturally Competent.” In Towards Multiculturalism: A Reader in Multicultural Education 2nd ed, edited by J. Wurzel, 62–77. Newton MA: Intercultural Resource.

- Biggs, J. 1996. “Enhancing Teaching through Constructive Alignment.” Higher Education 32: 347–364. doi:10.1007/BF00138871.

- Cornelius, S., and B. Stevenson. 2018. “International Online Collaboration as a Boundary Crossing Activity for Vocational Educators.” Journal of Vocational Education & Training. doi:10.1080/13636820.2018.1464053.

- Dawson, P. 2017. “Assessment Rubrics: Towards Clearer and More Replicable Design, Research and Practice.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 42: 347–360. doi:10.1080/02602938.2015.1111294.

- De Bruijn, E., S. De, Billett, and J. Onstenk. 2017. “Vocational Education in the Netherlands.” In Enhancing Teaching and Learning in the Dutch Vocational Education System, edited by E. de Bruijn, S. Billett, and J. Onstenk, 3–36. Dordrecht: Springer.

- De Bruijn, E., . D., and Y. Leeman. 2011. “Authentic and Self-directed Learning in Vocational Education: Challenges to Vocational Educators.” Teaching and Teacher Education 27: 694–702. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2010.11.007.

- Deardorff, D. K. 2006. “The Identification and Assessment of Intercultural Competence as a Student Outcome of Internationalization at Institutions of Higher Education in the United States.” Journal of Studies in International Education 10 (3): 241–266. doi:10.1177/1028315306287002.

- Deardorff, D. K. 2011. “Assessing Intercultural Competence.” New Directions for Institutional Research 149: 65–79. doi:10.1002/ir.381.

- Deardorff, D. K. 2015. “Intercultural Competence: Mapping the Future Research Agenda.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 48: 3–5. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2015.03.002.

- Dutch Education Council. 2016. Internationalising with Ambition. The Hague: Dutch Education Council.

- Fortuin, K., and D. Brinkman 2017. “How to Foster Students’ Intercultural Competence.” Presentation Teachers Day Wageningen University. https://sharepoint.wur.nl/sites/TeachersDay2017/SitePages/Home.aspx

- Gulikers, J., and C. Oonk. 2019. “Towards a Rubric for Stimulating and Evaluating Sustainable Learning.” Sustainability 11 (4): 969. doi:10.3390/su11040969.

- Hammer, M. R. 2015. “The Developmental Paradigm for Intercultural Competence Research.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 48: 12–13. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2015.03.004.

- Hofstede, G., G. J. Hofstede, and M. Minkov. 2010. Cultures and Organizations. Software of the Mind. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Jackson, J. 2015. “Becoming Interculturally Competent: Theory to Practice in International Education.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 48: 91–107. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2015.03.012.

- Kamovich, U., and L. Foss. 2017. “In Search of Alignment: A Review of Impact Studies in Entrepreneurship Education.” Education Research International 2017: 1–15. doi:10.1155/2017/1450102.

- MacDonald, M. N., J. P. O’Regan, and J. Witana. 2009. “The Development of National Occupational Standards for Intercultural Working in the UK.” Journal of Vocational Education & Training 61: 375–398. doi:10.1080/13636820903363600.

- Matsumoto, D., and H. C. Hwang. 2013. “Assessing Cross-cultural Competence: A Review of Available Tests.” Journal of Cross-cultural Psychology 44: 849–873. doi:10.1177/0022022113492891.

- McGury, S., D. Shallenberger, and D. E. Tolliver. 2008. “It’s New, but Is It Learning? Assessment Rubrics for Intercultural Learning Programs.” Assessment Update 20 (4): 6–9.

- Miles, M. B., and A. Huberman. 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publishers.

- Oberg, K. 1960. “Culture Shock: Adjustment to New Cultural Environments.” Practical Anthropology 7: 177–182. doi:10.1177/009182966000700405.

- OECD. 2016. “Global Competency for an Inclusive World.” https://www.oecd.org/pisa/aboutpisa/Global-competency-for-an-inclusive-world.pdf

- Perry, L. B., and L. Southwell. 2011. “Developing Intercultural Understanding and Skills: Models and Approaches.” Intercultural Education 22: 453–466. doi:10.1080/14675986.2011.644948.

- Popov, V., D. Brinkman, and J. P. van Oudenhoven. 2017. “Becoming Globally Competent through Student Mobility.” In Competence-based Vocational and Professional Education. Technical and Vocational Education and Training: Issues, Concerns and Prospects, Vol 23, edited by M. Mulder, 1007–1028. Cham: Springer.

- Tractenberg, R. E., and K. T. FitzGerald. 2011. “A Mastery Rubric for the Design and Evaluation of an Institutional Curriculum in the Responsible Conduct of Research.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 37: 1003–1021. doi:10.1080/02602938.2011.596923.

- Trede, F., W. Bowles, and D. Bridges. 2013. “Developing Intercultural Competence and Global Citizenship through International Experiences: Academic’s Perceptions.” Intercultural Education 24: 442–455. doi:10.1080/14675986.2013.825578.

- Vande Berg, M., R. M. Paige, and K. Hemming Lou. 2012. Student Learning Abroad. What Our Students are Learning, What They’re Not and What We Can Do about It. Virginia: Stylus Publishing.

- Verloop, N., J. Van Driel, and P. Meijer. 2001. “Teacher Knowledge and the Knowledge Base of Teaching.” International Journal of Educational Research 35: 441–461. doi:10.1016/S0883-0355(02)00003-4.

- Windschitl, M. 2002. “Framing Constructivism in Practice as the Negotiation of Dilemmas: An Analysis of the Conceptual, Pedagogical, Cultural, and Political Challenges Facing Teachers.” Review of Educational Research 72: 131–175. doi:10.3102/00346543072002131.

- Yamazaki, Y., and D. C. Kayes. 2004. “An Experiential Approach to Cross-cultural Learning: A Review and Integration of Competencies for Successful Expatriate Adaptation.” Academy of Management Learning & Education 3: 362–379. doi:10.5465/AMLE.2004.15112543.