ABSTRACT

This article examines how a virtual case that prepares students for practical scenario training affects police students’ performance in a practical scenario training. This study included 69 Swedish police students at the Basic Training Programme for Police Officers – 35 assigned to a virtual police case (VCASE) and 34 assigned to a conventional teacher-led (CON) lesson. A questionnaire captured how students experience training conditions and a blind assessment by police officers evaluated the students’ performance in the practical scenario training. The results show that both the VCASE and CON participants thought that the training they received before the practical training was meaningful and motivating. However, to a significantly higher degree than the CON students, the VCASE students thought that their preparation helped them during the practical training. The expert assessment of one practical scenario (stopping a suspected stolen car) showed that the VCASE participants performed better than the CON participants in three out of five criteria. In conclusion, the VCASE and the CON training had different effects on the students’ performance in the practical scenario: compared to the CON training, the VCASE training seemed to more effectively help the police students solve the situations presented in the practical scenario training.

Introduction

In vocational training, including the training of police officers, there is a need to link education and professional practice in a relevant way to develop useful knowledge and skills (e.g. Blondin Citation2014; Rantatalo, Sjöberg, and Karp Citation2018; Jahreie Citation2010). Police education, which this study focuses on, includes several topics and skills such as weapons, tactics, communication, conflict management, self-protection, driving, and mental and physical preparation. To bridge education and professional practice, these practical skills are often taught using scenario training (cf. Gonczi Citation2013; Jahreie Citation2010). In police education, scenario training is a common and integral part of the curriculum (e.g. Phelps et al. Citation2016; Rantatalo, Sjöberg, and Karp Citation2018; Werth Citation2011). For example, scenario training is used to teach students how to deal with complex and risky situations, where knowledge on how to handle different situations in collaboration with others is crucial for safe and professional practice (e.g. Gonczi Citation2013; Reader et al. Citation2006; Werth Citation2011). Theoretically, the development of professional knowledge includes the acquisition of the embodied knowledge (know how) needed to handle real-life situations (knowing-in-action) (Argyris and Schön Citation1974; Schön Citation1983). This knowledge incorporates tacit experiential knowledge and skills that are gradually acquired through scenario training (cf. Kinsella Citation2009; Polanyi Citation1966). Scenario training simulates situations relevant to the profession (Dieckmann et al. Citation2009; Onda Citation2012). In these scenarios (e.g. gaining control over disturbed young people or planning a search for a missing person), students play ‘roles’ that include performing ‘duties’ and gathering ‘key information about the problems to carry out these duties without play acting or inventing key facts […] and do the best they can in the situation in which they find themselves’ (Jones Citation2013, 18).

Although a review of previous research shows that scenario training follows three phases (preparation, scenario, and debriefing), most studies focus on the actual scenario training (Nyström et al. Citation2016). In the medical field, where a great deal of research on practical training has been carried out, studies have evaluated the effects of a specific method such as team training (Ballangrud et al. Citation2014) and observations of peer actions (Bloch and Bloch Citation2015). In addition, studies have investigated performance through participants’ self-estimation (e.g. Krameddine et al. Citation2013) or using video recordings of a scenario (e.g. Eikeland Husebø et al. Citation2012). Fewer studies have generally been done in the field of policing and these, like the medical studies, have mainly focused on the scenario training itself (Bennell, Jones, and Corey Citation2007). For example, some researchers in the field of policing have focused on decision-making in critical incidents (Van den Heuvel, Alison, and Power Citation2014) or on how uncertainty in decision-making can be categorised through studying a simulated hostage situation (Alison et al. Citation2015). Other studies have examined the authenticity of simulated police interrogations (e.g. Stokoe Citation2013) or examined the effectiveness of shooting simulators (e.g. Davies Citation2015).

The few studies that have investigated the role of preparation in relation to a practical scenario training conclude that an effective preparation phase improves the effectiveness of practical scenario training (e.g. Dieckmann, Gaba, and Rall Citation2007; Hopwood et al. Citation2016). For example, a pre-scenario briefing provides information needed in the scenario training (Alinier Citation2011; cf. Jones Citation2013), impacts police students’ selective attention and actions in the scenario training (Sjöberg, Karp, and Söderström Citation2015), and helps health-care students understand the particular rules of the simulation in addition to instructing them about the technical aspects of the scenario (Rystedt and Sjöblom Citation2012). While acknowledging that this research in general has advanced our knowledge on learning through scenario training, it appears that the link between preparation and performance in practical scenario training is unexplored. Our study contributes to research on the preparation phase in police education by examining how two preparation conditions affect practical scenario training of Swedish police students.

In the large realistic practical scenario training in focus in this study, the students, playing the role of police officers, are presented with different situations to solve. In the practical scenario, students perform various police tasks such as how to handle a stolen car case or secure a building, scenarios intended to help them develop an understanding of these tasks based on the national basic police tactics manual (Polishögskolan Citation2005). This training includes not only how to act and solve situations individually and with colleagues but also how to report the incident and apply Swedish law. Normally, in the 2.5-year police education in Sweden, this practical training is preceded by a lesson where the teacher walks through equipment, routines, roles, etc., to prepare the students for their upcoming practical training. However, as this lesson was deemed to be insufficient for encouraging reflections that could be helpful for the practical scenario training, alternative ways of preparing students were developed. Research has concluded that the development of professional practical knowledge relates to learning from experience and that training that encourages problem-solving, experimentation, and inquiry processes should be central in any educational setting (Schön Citation1983, Citation1987; Wallin, Nokelainen, and Mikkonen Citation2019). One training form that has been found to encourage inquiry, reflection, and experimentation is computer-based training (Ingerman, Linder, and Marshall Citation2009; Söderström et al. Citation2014). Studies on computer-based training suggest that collaborative learning is beneficial for problem-based decision-making skills (e.g. Davies Citation2002; Rogers Citation2011), supporting the development of professional practical knowledge (e.g. Dorn and Baker Citation2005; Mooney et al. Citation2012) and learning professional skills (e.g. Häll Citation2013). To encourage students to experiment and reflect on tactical skills and decision-making based on the national basic police tactics manual, a virtual case (VCASE) scenario training module was developed to prepare students for their practical scenario training.

In this paper, we examine how a virtual case intended to prepare students for practical scenario training affects police students’ performance in a practical scenario training. By comparing the computer simulation training (VCASE) with the traditional teacher-led lesson (CON), we examine how the police students experienced these learning conditions and how these conditions influenced their performance in practical scenario training.

Design and methodology

Participants

Using a convenience sample, this study recruited undergraduate students from semester three at the 2.5 year Basic Training Program for Police Officers at Umeå University enrolled in a large realistic scenario training. The student class (70 students) that participated in the study were divided into base groups (five to six students in each group) at the start of their first semester. Dividing students into practice groups is always applied when new students start their police education in Umea. The comparative group design study consisted of 69 participants – 35 participants assigned to a virtual case training group (VCASE) and 34 participants (one student was missing) assigned to a teacher-led lesson (CON). A power calculation using G*Power version 3.1.9.3 (Faul et al. Citation2007) indicated that with a sample size of 35 and 34 in the groups and a power of 0.8 the study could detect effects of Cohen’s d = 0.7 or higher and reflect differences between the preparation conditions. Similar studies on computer-based training in police education appear to be largely missing, but research that has studied learning effects of computer-based training in comparison with traditional teaching in science education (Rutten, van Joolingen, and van der Veen Citation2012) found effect sizes ranging from 0.37 to 0.87.

In total, six base groups were assigned randomly to the VCASE and six base groups to the CON group. Both the VCASE (22 males and 13 females) and CON group (23 males 11 females) had an even gender composition and each consisted of five base groups with six students (four men and two women; one VCASE group with three women) and one base group with five students (three men and two women). There were no gender differences between the VCASE and CON group (t(67) = 0.412, p > 0.05). A majority of the 69 students in the class were between 22 and 30 years (M = 26.9) and 35% of them were women. The average age for the VCASE group was 26.7 years (range 22–42) and for the CON group 27.1 years (range 22–37). There were no age differences between the groups (t(67) = −0.356, p > 0.05). The two police student classes before and after the investigated class had similar average age and gender division (before M = 25.1 years (40% women) and 26.1 years (35% women); after M = 26.0 years (39% women) and 24.4 years (39% women)).

Study design

The VCASE group worked two hours with a virtual police case to perform two exercises (a stolen car incident and surveillance of a house). The CON group received a two-hour teacher-led lesson with the same content. A practical scenario training followed the VCASE and the CON training. Blind to group belonging, police officers assessed the students’ performance in the practical scenario training. A questionnaire was administered after training to collect students’ perceptions of the pre-training (VCASE or CON) in relation to the practical training. Participation was voluntary and participants provided written informed consent before the study. An outline of the design is presented in .

Table 1. Design of the study.

Pre-training sessions

The pre-training sessions for both the VCASE and CON groups focused on scenarios and situations that would be practised in the practical scenario training sessions. Both the VCASE and CON students worked in groups to simulate the real-world work conditions (police officers work in pairs), where they will be required to negotiate their actions.

The virtual case training

The virtual case was designed to help students working in groups perform specific practical techniques as well as help them make decisions and guide their actions according to the national guidelines (see Wallin, Nokelainen, and Mikkonen Citation2019 view of education that stimulates professional knowledge). In the program, students worked in front of the computer with storylines that consisted of images, videos, texts, and discussion questions that encouraged students to reflect about and solve police situations. The student base groups (5–6 students) worked for two hours with a virtual case that required them to interpret situations and execute strategies to solve the situations.

The students worked with different cases and discussed possible solutions to questions related to the cases, ways to handle the situations, and where they need to act. No correct answers were given; rather, the students worked together and discussed advantages and disadvantages for different solutions and decision-making. The students reflected on the communication in the group, stress management, and strategies in relation to national base tactics. In this paper, we focus on two scenarios: stopping a stolen car and observing/securing a house with suspects.

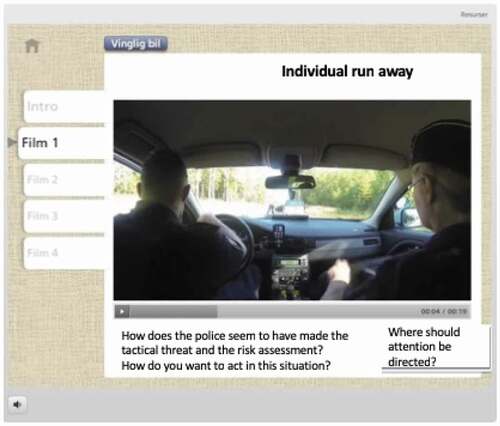

The stolen car scenario () included questions about where and when it is convenient or inappropriate to stop a car. For example, how should they stop a car? What should they be prepared for when they stop a car? What should they do if the person runs from the car? What should they consider while running after the suspect? How can police behaviour affect the situation? How should the police act and be prepared?

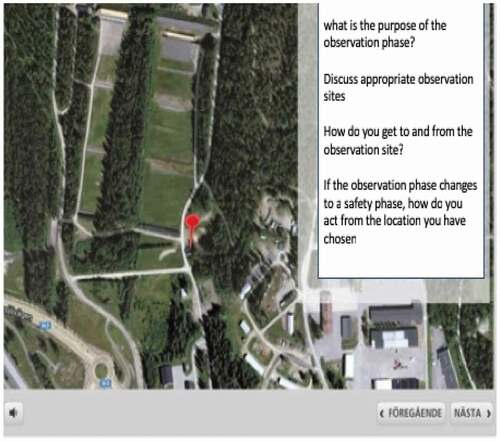

The observing/securing a building case () included questions about where they should place themselves, how they should communicate with each other, how they should get to the site without being detected, and how they should take care of someone on the spot.

The teacher-led lesson – conventional training

The CON base groups worked with similar scenarios and situations as the VCASE base groups. The CON groups used the scenarios to reflect on how to act in different situations. The lesson prepared the students for the scenario training and enabled the evaluation of their actions during the scenario training. For two hours, the students discussed ways to solve the situations. On the blackboard, the teacher wrote down discussion themes, scenarios (the vehicle stop and observing/securing buildings), and important issues that needed to be discussed. The students used the law book and the base tactics manual to inform their discussions of the different solutions presented and their decision-making. The students were asked to reflect on the communication in the group, stress management, and strategies in relation to national base tactics. The teacher helped the students reflect on problems and opportunities associated with the situations they might find themselves in during the scenario exercise. Tactical aspects in the stolen car case included the following questions: When is it appropriate or inappropriate to stop a car? How should they stop a car? What should they be prepared for when they stop a car? What should they do if the person runs away from the car and what should they consider when pursuing a suspect? How can police behaviour affect the situation? How should the police act and be prepared? In addition, the instructor guided the students in discussions about the observing/securing building scenario. These discussions included the following questions: Where should they place themselves? How should they communicate with each other? How should they get to the site without being detected? What should they do if they need to detain someone on the spot?

Practical scenario training

In the third semester of police training, a full-day practical scenario training is conducted where the students train for their prospective professional role and participate in a scenario derived from professional practice. These practical scenarios include several people (actors in secondary roles) who the police students respond to and handle on the basis of their professional role as a police officer. In the practical scenario training, students work in groups of two or three to enable sufficient practical training for each student. The practical scenario training was similar to the virtual cases they encountered during the computer simulation training and the content in the teacher-led lesson. The scenarios involved, for example, a vehicle with perpetrators that needed to be stopped without risking harm to by-standers and observing/securing a building without being detected.

Methods

Instruments used in this study include a questionnaire that was collected after the scenario training and blinded expert assessments of the performance of the practical scenario training.

Assessment of practical performance

Blinded to the students’ pre-training (i.e. CON or VCASE), police officers responsible for the specific practical scenario training assessed the performance of the students. The study was conducted within the framework of the regular teaching, which meant that each assessor assessed both the VCASE and CON groups but not the same individuals. The scenarios assessed were the same as the scenarios the students engaged during their pre-training – a stolen car scenario and observing/securing a building scenario. The stolen car scenario was built around the national base tactics for police work and included stopping a stolen car twice and assessing the students’ treatment of the driver and the passenger, their report of the incident, and their use of legal support to determine their actions. Because some groups did not have time to participate in ‘the observation and securing of a building’ scenario during the scenario training day, there were not enough performance assessment data to compare the VCASE and the CON group for this scenario. Therefore, the assessment data only concern the stolen car case. However, some police officers forgot to fill in their overall assessment in the protocol, so the number of individuals, in some cases, differed in the overall assessment of the performance. The expert assessment protocol was constructed by police officers using the following criteria: the extent to which students apply the national method for stopping a vehicle or for observing/securing a building including time to actions, adjustments of the tactics based on the specific situation, the reporting of the incidents (what to report based on the situation), attitude and conflict-reducing communication, and legal support for their actions. The areas of assessments included the performance of different aspects (e.g. time to action when the car they stopped drove away [fast/slow] and if the suspects had opportunity to speak to each other [yes/no]) in each criterion and an overall judgement of the above-mentioned criteria. The overall judgements were graded on a 5-point scale (from very bad to very good).

Questionnaire

The questionnaire was structured into different themes. To capture the link between pre-training and practical training, we relied on Schön’s perspectives about reflection on action, reflection in action, and knowing in action (Citation1983, Citation1987), Druckman and Ebner (Citation2008) questions about learning from and developing knowledge of an exercise, and Häll’s (Citation2013) questions about learning processes and computer-based training (e.g. problem solving and group work). The questions inquired into students’ opinions about how the pre-training prepared them for and guided their actions in the practical scenario training. The first theme concentrated on the participants’ perceptions of the meaningfulness of the pre-training task (VCASE vs. CON), their experiences of the group work (see Häll Citation2013), how the tasks contributed to the development of their knowledge, and how it prepared them for the practical scenario training (see Druckman and Ebner Citation2008). Furthermore, the theme also inquired into how they perceived the scenario training as a way to train police skills (cf. Druckman and Ebner Citation2008). The second theme focused on the participants’ perceptions of their practical training, e.g. discussed different possible solutions (Schön, reflection on action) and the students’ opinions about how the pre-training prepared for and guided their actions (Schön, reflection in action) in the practical scenario training. The questions in the theme were based on previously used questions in a small-scale study in which the participating police students had the opportunity to comment on the questions. They did not imply that the questions were difficult to understand or that they would not be relevant for the experiences of the practical training (Söderström, Lindgren, and Neely Citation2019). These questions were used here to query the students about whether they thought they and the group had sufficient knowledge to solve the tasks in the practical training, how confident they were of how they would act, and how well they believed they carried out the practical training (Schön, knowing in action). Questionnaires were completed individually and collected directly after the practical scenario training. Answers were given either by grading statements on a 5-point scale or by choosing one ‘best fit’ alternative (from strongly disagree to completely agree) and, in most cases, with the possibility of open-ended commenting.

Analysis

Independent t-tests were used to compare groups (VCASE and CON) with respect to the variables in the questionnaire and the assessment of the practical scenario training. Measures of effect size are reported using Cohen´s d (Lakens Citation2013). All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 24.0.

Results

We present the results in two steps. First, the VCASE and CON students’ experiences with the pre-training and the practical scenario training are described. Second, the assessment of their practical performance.

Experiences of the training

Pre-training

The results show that both the CVASE group and the CON group appreciated their respective pre-training. However, the VCASE group thought to significantly higher degree that the preparations were meaningful, engaging, and challenging ().

Table 2. Students’ opinions about their pre-training.

The students also found that their group work during the pre-training tasks was helpful. In both the VCASE and CON groups, nearly all the students stated they were motivated to do their best in the pre-training scenarios and that the collaboration in the group was good. However, the VCASE group agreed to significantly higher degree that the group performed well (t(66) = 2.01, p = 0.048, Cohen´s d = 0.48), that they discussed possible solutions for solving situations (t(66) = 4.44, p = 0.00, Cohen´s d = 1.08), and that they all agreed on scenario solutions (t(66) = 2.63, p = 0.011, Cohen´s d = 0.64).

The results show further that there are significant differences between how the CON and VCASE thought the scenarios supported their learning (). To a significantly higher degree, the VCASE group agreed that the pre-training scenarios improved their knowledge of police work, their understanding of how to solve police tasks, their theoretical preparation for the practical scenario training, and their ability to respond to situations.

Table 3. Students’ opinions of how the pre-training contributed to their learning and prepared them for the scenario training.

Experiences of the practical scenario training

Overall, the VCASE and CON groups agreed to a high extent that the practical scenario training improved their police knowledge and skills. There were no significant differences between how the VCASE and CON thought the practical scenario training helped them develop knowledge of police work, understand different ways of solving police tasks, and improve their skills of how to act in police situations.

Regarding how they experienced the group work during the practical scenario training the results show that a majority of the students in both the VCASE and CON groups agreed that the group work during the practical scenario training encouraged them to perform as good as possible in the scenarios, that the collaboration worked well, and that all the students contributed to creating a feeling of a police situation. However, to a significantly higher extent, the VCASE group thought that the group performed well (t(67) = 2.45, p = 0.017, Cohen’s d = 0.60), that they discussed different possible solutions for solving situations (t(67) = 2.93, p = 0.005, Cohen’s d = 0.70), and that all agreed on the scenario solutions (t(67) = 2.84, p = 0.006, Cohen’s d = 0.68).

The results show that in the stolen car case scenario there are differences between VCASE and CON students’ perceptions of how they acted in two out of the six items. shows that both groups agreed that they had sufficient knowledge to solve the task, performed well, played the role of a police officer and not a student, and that they were motivated to perform. However, to significantly higher degree, the students in the VCASE group agreed that they felt confident on how to act and felt sufficiently prepared.

Table 4. Students’ perceptions of carrying out the stolen car case.

There were, however, greater differences between the two groups regarding the students’ experiences with how they acted when observing/securing a building scenario (). In five out of six items, the VCASE group agreed to a significantly higher degree that they felt confident in how to act, had sufficient knowledge to solve the task, performed well, took the role of a police officer and not a student, and was sufficiently prepared.

Table 5. Students’ perceptions of observing/securing a building.

In summary, the results show that the VCASE students to a higher extent believed that their pre-training lesson contributed to their learning and prepared them for the practical scenario training. In addition, the VCASE students’ perceptions of carrying out the practical training also revealed that they, in both scenarios, to a significantly higher degree than the CON students´ felt confident in how to act and that they were sufficiently prepared for the practical training scenario.

Assessment of practical training

According to the police officers’ assessments of the practical training, the VCASE and CON groups performed differently in the stolen car case scenario. The overall assessment of the base tactics (five-grade scale) revealed that the VCASE performed better in three of the five criteria. shows that the VCASE group to a significantly higher extent responded faster to the second car stop, i.e. which officer chase after the driver, which officer take contact with passengers, and eventually taking control of the car. In addition, the VCASE group performed better on reporting to the officer in charge (e.g. if they found the car, stopped the car, and took action on site) and on treating suspects including whether the suspects were given the opportunity to give their version of the incident or talk to or threaten each other. For the two other criteria – stop 1 and legal support – there were no significant differences in the assessments made by the police officers.

Table 6. Police officers’ assessment of the practical scenario training stolen car case.

In summary, the police officers’ assessments of the practical training show that the VCASE students more stringently adhered to the base police tactics model they were assessed from.

Discussion

This study shows that VCASE and CON training had different effects on the students’ performance in the practical scenario. There was a stronger link between the virtual case training and the students’ perceptions about, for example, how the training influenced understandings of solving police tasks and guidance of how to act in the scenario training. To some extent, this self-evaluation was supported by the police officers’ assessments. For example, the police officer assessments revealed that the VCASE group performed better in three out of five areas (Cohen´s d 0.68–0.72) related to the national base tactics for police. In Dewey’s (Citation1938) language, the VCASE group received ‘experiences that were more helpful for […] dealing effectively with the situations which follow [the practical training in this case]’ (Citation1938, 44). Regarding the students’ opinions about their pre-training, the results show that the VCASE training had large effect sizes (Cohen´s d = 0.96–1.08) on items related to being active and level of participation (e.g. discussing possible solutions for solving situations) and reflective practice (e.g. demanded thinking). That is, the students in the VCASE groups used one another as resources for the learning process (exploring and exchanging views) not only during the preparation session but also during the practical scenario training (e.g. discussing and agreeing on solutions) (cf. Ludvigsen, Rasmussen and Säljö, Citation2010). The VCASE training also had large effect sizes (Cohen´s d = 1.41–1.46) on items about how the pre-training contributed to their learning and prepared them for the scenario training such as guidance for action and understanding of different ways to solve problems. A possible interpretation of the differences between the VCASE and the CON training may be that the virtual cases help the students to virtually experience a police situation, which encourages an inquiry process helpful for interpreting information and negotiating the complexities and challenges they are faced with in the practical training (Christopher Citation2015; cf. Johnson’s (Citation2010) view on transfer; Klein’s (Citation1989) view on pattern recognition). Based on the police officers’ assessment, this pre-training process seemed to better support situational awareness during the practical scenario training (cf. Söderström, Lindgren, and Neely Citation2019). Most likely, the problems to solve in the virtual cases encouraged the VCASE students to see a link between discussion and action, which may be one reason why they were more confident compared to the CON students in how to act and felt better prepared to handle situations.

The results from this study also raise second-order questions about teaching and instruction in vocational education that uses practical training. Practical training in vocational education for emergency services, such as police education and firefighter training, traditionally rests on an instruction paradigm led by a teacher who provides didactic instruction and demonstration (see Holmgren Citation2015 for firefighter training). The results from this study, however, partly challenges the view that students always need teacher-led instruction to learn practical skills. The VCASE students did not have any teachers who instructed them; rather, they relied on each other. Although research clearly points out the need for reflection to facilitate learning from the experience gained in the practical training, reflective teaching seem to be limited in the police educational practice. Bek (Citation2012) found that Swedish police teachers action review after the practical training was mostly done as a way to check how students experience their performance rather than as a way to encourage structured critical self-reflection. Similarly, Phelps et al. (Citation2016, 52) put forth that explicit reflection during and after action remains limited in Norwegian police education. What this study shows is that a well-designed tool for preparing practical training (which can be used irrespective of the presence of a teacher, time, place, and need for repetition) may offer possibilities for teachers to invest more energy and more time in action reviews (feedback and reflections) of the scenarios. This may increase police students’ possibilities to learn from practical scenario training and gradually acquire practical knowledge useful in the up-coming police work (Argyris and Schön Citation1974; Schön Citation1987; see also Roessger Citation2016).

Concluding remarks

This study has offered reflections on two methods for preparing students for practical scenario training and confirms previous assumptions of the importance of preparation for enhancing possibilities to learn through scenario training (see Diamond, Middleton, and Mather Citation2011; Nestel and Tierny Citation2007: Sjöberg, Karp, and Söderström Citation2015). The results from the study are also in line with other studies in other fields suggesting that computer-based training encourages reflection and has positive effects for learning knowledge and skills (e.g. Holzinger et al. Citation2009; Häll Citation2013; Silén et al. Citation2008). Due to the fact that the study was fully integrated in the ordinary teaching and that age and gender distributions were similar to previous and subsequent classes, it seems plausible that the results are valid and reliable with regards to police education at Umea University.

There are, however, a number of limitations with the study and we also need to express caution with regard to the results. Regarding the questionnaire, although questions were derived from previous research or have been used previously in a small-scale study in which the police students found the questions understandable and relevant, this study has uncertainties in how well the questions capture professional practical knowledge. Future work will aim at reducing those uncertainties. For example, by including experienced police officers in the validation of the questionnaire and to further test their relevance on police students, but also to explore which items that in a reliable way capture the link between pre-training and practical training.

Furthermore, the choice to not intervene, allowing ‘business as usual’, raises the question whether the police officers’ ratings of student performance were reliable. An analysis of the two police officers assessment shows that officer A rated the VCASE group significantly higher in criteria stop 2 and legal support, and officer B rated the VCASE group significantly higher in criteria stop 1 and reporting to the officer in charge and on treating suspects. Moreover, the police officers who were grading the students used the rating scales differently. With this small sample size, lack of observer reliability may have an effect on the results. To overcome these limitations when conducting research within the ordinary teaching, it is critical to emphasise how to use assessment protocols, including calibration of the assessment criteria and high interobserver reliability.

To further strengthen the validity of future research, larger samples are necessary and variables must be considered that may affect preparation and performance such as students’ prior knowledge, work experience, and study motivation. In addition, different police educational cultures, different ways of preparing the scenario, and different practical scenarios are also important to consider. Both quantitative and qualitative approaches need to be incorporated to increase knowledge of under what circumstances preparation is effective for practical training.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alinier, G. 2011. “Developing High-Fidelity Health Care Simulation Scenarios: A Guide for Educators and Professionals.” Simulation & Gaming 42 (1): 9–26. doi:10.1177/1046878109355683.

- Alison, L., N. Power, C. van den Heuvel, and S. Waring. 2015. “A Taxonomy of Endogenous and Exogenous Uncertainty in High-risk, High-impact Contexts.” Journal of Applied Psychology 100 (4): 1309–1318. doi:10.1037/a0038591.

- Argyris, C., and D. A. Schön. 1974. Theory in Practice: Increasing Professional Effectiveness. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Ballangrud, R., M. L. Hall-Lord, M. Persenius, and B. Hedelin. 2014. “Intensive Care Nurses’ Perceptions of Simulation-based Team Training for Building Patient Safety in Intensive Care: A Descriptive Qualitative Study.” Intensive and Critical Care Nursing 30 (4): 179–187. doi:10.1016/j.iccn.2014.03.002.

- Bek, A. 2012. “Undervisning och reflektion. Om undervisningens förutsättningar för studenters reflektion mot bakgrund av teorier om erfarenhetslärande.” dissertation, Umeå universitet: Pedagogiska institutionen.

- Bennell, C., N. J. Jones, and S. Corey. 2007. “Does Use-of-force Simulation Training in Canadian Police Agencies Incorporate Principles of Effective Training?” Psychology, Public Policy, and Law 13 (1): 35–58. doi:10.1037/1076-8971.13.1.35.

- Bloch, S. A., and A. J. Bloch. 2015. “Simulation Training Based on Observation with Minimal Participation Improves Paediatric Emergency Medicine Knowledge, Skills and Confidence.” Emergency Medicine Journal 32 (3): 195–202. doi:10.1136/emermed-2013-202995.

- Blondin, M. 2014. Övning ger färdighet? Lagarbete, riskhantering och känslor i brandmäns yrkesutbildning. Linköping: Linköpings Universitet.

- Christopher, S. 2015. “The Quantum Leap: Police Recruit Training and the Case for Mandating Higher Education Pre-entry Schemes.” Policing 9 (4): 388–404. doi:10.1093/police/pav021.

- Davies, A. 2015. “The Hidden Advantage in Shoot/don’t Shoot Simulation Exercises for Police Recruit Training.” Salus Journal 3 (1): 16–30.

- Davies, C. H. J. 2002. “Student Engagement with Simulations: A Case Study.” Computers & Education 39 (3): 271–282. doi:10.1016/S0360-1315(02)00046-5.

- Dewey, J. 1938. Experience and Education. New York: Touchstone.

- Diamond, S., A. Middleton, and R. Mather. 2011. “A Cross Faculty Simulation Model for Authentic Learning.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 48 (1): 25–35. doi:10.1080/14703297.2010.518423.

- Dieckmann, P., D. Gaba, and M. Rall. 2007. “Deepening the Theoretical Foundations of Patient Simulations as a Social Practice.” Simulation in Healthcare 2 (3): 183–193. doi:10.1097/SIH.0b013e3180f637f5.

- Dieckmann, P., T. Manser, M. Rall, and T. Wehner. 2009. “On the Ecological Value of Simulation Settings for Training and Doing Research in the Medical Domain.” In Using Simulations for Education, Training and Research, edited by P. Dieckmann. Vol. 3, (pp. 18–39). Berlin: Pabst Science Publishers.

- Dorn, L., and D. Baker. 2005. “The Effects of Driver Training on Simulated Driving Performance.” Accident Analysis and Prevention 37 (1): 63–69. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2004.06.005.

- Druckman, D., and N. Ebner. 2008. “Onstage or behind the Scenes? Relative Learning Benefits of Simulation Role-play and Design.” Simulation & Gaming 39 (4): 465–497. doi:10.1177/1046878107311377.

- Eikeland Husebø, S., F. Friberg, E. Søreide, and H. Rystedt. 2012. “Instructional Problems in Briefings: How to Prepare Students for Simulation-Based Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Training.” Clinical Simulation in Nursing 8 (7): 307–318. doi:10.1016/j.ecns.2010.12.002.

- Faul, F., E. Erdfelder, A.-G. Lang, and A. Buchner. 2007. “G*Power 3: A Flexible Statistical Power Analysis Program for the Social, Behavioral and Biomedical Sciences.” Behavior Research Methods 39 (2): 175–191. doi:10.3758/BF03193146.

- Gonczi, A. 2013. “Competency-based Approaches: Linking Theory and Practice in Professional Education with Particular Reference to Health Education.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 45 (12): 1290–1306. doi:10.1080/00131857.2013.763590.

- Häll, L. O. 2013. Developing Educational Computer-assisted Simulations: Exploring a New Approach to Researching Learning in Collaborative Healthcare Simulation Contexts. Umeå: Umeå University, Department of Education.

- Holmgren, R. 2015. Brandmannautbildning på distans, en het fråga: Om utmaningar, motsättningar och förändringar vid implementering av distansutbildning. Umeå: Umeå universitet.

- Holzinger, A., M. D. Kickmeier–Rust, S. Wassertheurer, and M. Hessinger. 2009. “Learning Performance with Interactive Simulations in Medical Education: Lessons Learned from Results of Leaning Complex Physiological Models with the HAEMOdynamics SIMulator.” Computers & Education 52 (2): 292–301. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2008.08.008.

- Hopwood, N., D. Rooney, D. Boud, and M. Kelly. 2016. “Simulation in Higher Education: A Sociomaterial View.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 48 (2): 165–178. doi:10.1080/00131857.2014.971403.

- Ingerman, Å., C. Linder, and D. Marshall. 2009. “The Learners´experience of Variation: Following Students´ Threads of Learning Physics in Computer Simulation Sessions.” Instructional Science 37: 273–292. doi:10.1007/s11251-007-9044-3.

- Jahreie, C. F. 2010. “Making Sense of Conceptual Tools in Student-generated Cases: Student Teacher Problem-solving Processes.” Teaching and Teacher Education 26 (6): 1229–1237. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2009.12.002.

- Johnson, S. 2010. “Transferable Skills.” In The Sage Handbook of Philosophy of Education, edited by R. Bailey, R. Barrow, D. Carr, and C. McCarthy, 353–368. London: Sage Publications.

- Jones, K. 2013. Simulations: A Handbook for Teachers and Trainers. London: Routledge.

- Kinsella, E. A. 2009. “Professional Knowledge and the Epistemology of Reflective Practice.” Nursing Philosophy 11 (1): 3–14. doi:10.1111/j.1466-769X.2009.00428.x.

- Klein, G. A. 1989. “Recognition-primed Decisions.” In Advances in Man-Machine Systems Research, edited by W. B. Rouse, 47–92. Vol. 5. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

- Krameddine, Y., D. DeMarco, R. Hassel, and P. H. Silverstone. 2013. “A Novel Training Program for Police Officers that Improves Interactions with Mentally Ill Individuals and Is Cost-effective.” Frontiers in Psychiatry 4 (9). doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00009.

- Lakens, D. 2013. “Calculating and Reporting Effect Sizes to Facilitate Cumulative Science: A Practical Primer for T-tests and ANOVAs.” Frontiers in Psychology 4: 863. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00863.

- Ludvigsen, S. R., A. Lund, I. Rasmussen, and R. Säljö, eds. 2010. Learning across Sites: New Tools, Infrastructures and Practices. London: Routledge.

- Mooney, J. S., L. Griffiths, M. Patera, J. Roby, P. Ogden, and P. Driscoll. 2012. “An Electronic Tabletop ‘eTable Top’ Exercise for UK Police Major Incident Education.” Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT) Proceedings 40–42. doi: 10.1109/ICALT.2012.14.

- Nestel, D., and T. Tierny. 2007. “Role-play for Medical Students Learning about Communication: Guidelines for Maximising Benefits.” BMC Medical Education 7 (3): 1–9. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-7-3.

- Nyström, S., J. Dahlberg, H. Hult, and M. Abrandt Dahlgren. 2016. “Enacting Simulation: A Sociomaterial Perspective on Students’ Interprofessional Collaboration.” Journal of Interprofessional Care 30 (4): 441–447. doi:10.3109/13561820.2016.1152234.

- Onda, E. 2012. “Situated Cognition: Its Relationship to Simulation in Nursing Education.” Clinical Simulation in Nursing 8 (7): 273–280. doi:10.1016/j.ecns.2010.11.004.

- Phelps, J. M., J. Strype, S. Le Bellu, S. Lahlou, and J. Aandal. 2016. “Experiential Learning and Simulation-based Training in Norwegian Police Education: Examining Body-worn Video as a Tool to Encourage Reflection.” Policing 12 (1): 50–56.

- Polanyi, M. 1966. The Tacit Dimension. New York: Doubleday.

- Polishögskolan. 2005. Nationell Bastaktik (National Base Tactics). Stockholm: EO Print.

- Rantatalo, O., D. Sjöberg, and S. Karp. 2018. “Supporting Roles in Live Simulations: How Observers and Confederates Can Facilitate Learning.” Journal of Vocational Education & Training 71 (3): 482–499. doi:10.1080/13636820.2018.1522364.

- Reader, T., R. Flin, K. Lauche, and B. Cuthbertson. 2006. “Non-technical Skills in the Intensive Care Unit.” British Journal of Anaesthesia 96 (5): 551–559. doi:10.1093/bja/ael067.

- Roessger, K. M. 2016. “Skills-based Learning for Reducible Expertise: Looking Elsewhere for Practice.” Journal of Vocational Education & Training 68 (1): 118–132. doi:10.1080/13636820.2015.1117522.

- Rogers, L. 2011. “Developing Simulations in Multi-user Virtual Environments to Enhance Healthcare Education.” British Journal of Educational Technology 42 (4): 608–615. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8535.2010.01057.x.

- Rutten, N., W. R. van Joolingen, and J. T. van der Veen. 2012. “The Learning Effects of Computer Simulations in Science Education.” Computers & Education 58 (1): 136–153. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2011.07.017.

- Rystedt, H., and B. Sjöblom. 2012. “Realism, Authenticity and Learning in Healthcare Simulations: Rules of Relevance and Irrelevance as Interactive Achievements.” Instructional Science 40 (5): 785–798. doi:10.1007/s11251-012-9213-x.

- Schön, D. A. 1983. The Reflective Practitioner. How Professionals Think in Action. New York: Basic Books.

- Schön, D. A. 1987. Educating the Reflective Practitioner. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Silén, C., S. Wirell, J. Kvist, E. Nylander, and Ö. Smedby. 2008. “Advanced 3D Visualization in Student-centred Medical Education.” Medical Teacher 30 (5): 115–124. doi:10.1080/01421590801932228.

- Sjöberg, D., S. Karp, and T. Söderström. 2015. “The Impact of Preparation: Conditions for Developing Professional Knowledge through Simulations.” Journal of Vocational Education & Training 67 (4): 529–542. doi:10.1080/13636820.2015.1076500.

- Söderström, T., L. Häll, T. Nilsson, and J. Ahlqvist. 2014. “Computer Simulation Training in Health Care Education: Fuelling Reflection-in-Action.” Simulation & Gaming 45 (6): 805–828. doi:10.1177/1046878115574027.

- Söderström, T., C. Lindgren, and G. Neely. 2019. “On the Relationship between Computer Simulation Training and the Development of Practical Knowing in Police Education.” The International Journal of Information and Learning Technology 36 (3): 231–242. doi:10.1108/IJILT-11-2018-0130.

- Stokoe, E. 2013. “The (In) Authenticity of Simulated Talk: Comparing Role-played and Actual Interaction and the Implications for Communication Training.” Research on Language & Social Interaction 46 (2): 165–185. doi:10.1080/08351813.2013.780341.

- Van den Heuvel, C., L. Alison, and N. Power. 2014. “Coping with Uncertainty: Police Strategies for Resilient Decision-making and Action Implementation.” Cognition, Technology and Work 16 (1): 25–45. doi:10.1007/s10111-012-0241-8.

- Wallin, A., P. Nokelainen, and S. Mikkonen. 2019. “How Experienced Professionals Develop Their Expertise in Work-based Higher Education: A Literature Review.” Higher Education 77 (2): 359–378. doi:10.1007/s10734-018-0279-5.

- Werth, E. P. 2011. “Scenario Training in Police Academies: Developing Students’ Higher-level Thinking Skills.” Police Education and Training 12 (4): 325–340.