ABSTRACT

With this paper we want to contribute to the debate on the usage of vocational training as a tool to promote the integration of disadvantaged groups. We focus in particular on programmes that target refugees and highlight the organisational and coordination challenges that must be addressed in order to develop such programmes. Relying on knowledge developed by scholars of collective skill formation and by those who have studied policy coordination, we develop a number of hypotheses that can account for the successful implementation of this type of programmes. We then test our hypotheses against an example taken from Switzerland, consisting of a one-year pre-apprenticeship dual training programme adopted in 2018. We argue that its win-win quality, the flexibility with which it was managed and possibly also the political salience of the issue of refugee integration at the time, were the key factors explaining its successful adoption.

1. Introduction

The labour market integration of refugees is a serious challenge for most destination countries. In general, even several years after migration, employment rates of refugees remain substantially lower than those of natives and of other migrants (see e.g. Bevelander Citation2016; Brell, Dustmann, and Preston Citation2020). This is understandable. Refugees are some of the most vulnerable individuals in our societies, they have often experienced war and persecution. In addition, they tend to come from countries with failing institutions and disrupted education systems. As a result, integration into labour markets or education and training in destination countries is often problematic. In order to deal with this issue, several countries have developed refugee integration policies that rely extensively on the provision of vocational education and training (VET) (see CEDEFOP Citation2019; for a critical view, Chadderton and Edmonds Citation2015).

Vocational training has the potential to play a big role in refugee integration especially in countries which have traditionally relied on collective skill formation systems, or dual VET, like Germany, Austria, Switzerland or Denmark. In these countries, vocational training is provided jointly by employers and vocational schools. Historically, these systems have proved rather successful in integrating youths into labour markets, and have some of the lowest youth unemployment rates in the OECD world (Ryan Citation2001; Busemeyer and Trampusch Citation2012).

As a result, it is not surprising that countries with collective skill formation systems have considered using VET as a tool for promoting the labour market integration of refugees. By involving employers, their vocational training system provides a strong integration potential. It is reasonable to expect that dual vocational training will also be a promising tool for the labour market integration of refugees, who will get formal training but also an opportunity to gain work experience and be socialised into the host countries’ written and unwritten workplace rules, habits, and expected behaviour.

While collective skill formation systems are a promising tool for the promotion of refugees’ labour market integration, these systems are also very complex machines. A collective skill formation system needs employers, the government and the trade unions to work together and agree on such diverse matters as the financing of the system, the content of the curriculum, how much apprentices are to be paid, how much time they can spend in school and in the workplace. Those who have studied collective skill formation systems have shown that their success hinges on a very delicate equilibrium and a strong inclination to collaborate as well as public policies that support cooperation (Busemeyer and Trampusch Citation2012; Culpepper Citation2003; Emmenegger, Graf, and Trampusch Citation2019).

In this article, we explore the organisational and coordination challenges involved in the provision of VET to refugees in Switzerland. How can the actors whose support is needed be convinced to collaborate and develop programmes that provide VET to refugees? What factors facilitate/hinder collaboration in this very specific policy field? We believe that these questions are relevant. In fact, the provision of VET in collective skill formation systems is a complex endeavour requiring a high capacity for coordination by state and private actors. But when the target group is refugees, we can expect complexity to increase even further, for a number of reasons. First, the policy community that needs to collaborate is larger, because it includes immigration authorities, particularly those in charge of the promotion of refugee integration. Second, many refugees come from countries with failing education systems and do not possess the cognitive and noncognitive skills needed in order to start an apprenticeship. In some cases, the distance can be substantial as some youths have never attended school (Manhica et al. Citation2019). Third, most refugees come from culturally distant countries, and are not familiar with the written and unwritten rules that govern the fields of education and employment in the destination country. This may make their integration in the training firms more difficult. Fourth, refugees may suffer from ethnic discrimination by employers, and find it difficult to find apprenticeship positions (see e.g. Zschirnt and Ruedin Citation2016; Protsch and Solga Citation2017).

Theoretically, our starting point is scholarship on the inclusive dimension of collective skill formation systems, which we complement with insights from the literature on policy coordination. Our research design is essentially deductive, but we are open to the possibility that factors not included in our theoretical framework will turn out to be relevant. We apply these theoretical perspectives to the adoption and implementation of a recent programme developed in Switzerland: a one-year apprenticeship preparation programme for refugees. The programme was initiated by the Federal government in 2016, in the midst of the refugee crisis, and was successfully implemented in 2018, with an initial intake of approximately 800 refugees. The provision of this programme required the collaboration of migration and vocational training offices, employers’ associations and several individual firms. How was this possible? What obstacles had to be overcome in order to make this happen?

The article is structured in the following way. The next section considers the theoretical implications of the research questions above, and formulates a number of hypotheses concerning the conditions that, on the basis of theory, can be expected to facilitate the adoption of this type of programmes. We then provide an empirical account of the development of the programme, paying particular attention to four specific coordination challenges that we identify. Finally, we discuss the findings and conclude by highlighting what we believe were the key factors that facilitated the adoption of the programme.

2. Theory

In order to address the questions outlined above, we rely on two different strands of literature: a rather recent but fast-growing literature on the integrative role of collective skill formation systems (e.g. Bonoli and Emmenegger Citation2020; Carstensen and Ibsen Citation2020; Durazzi and Geyer Citation2019); and a much more established literature on policy coordination in general (e.g. Trein, Meyer, and Maggetti Citation2019; Tosun and Lang Citation2017), which aims to identify the conditions that make successful policy coordination possible. The implications of these two strands of literature for our research questions are discussed next.

Using collective skill formation systems as social policy

Given the proven integrative capacity of collective skill formation systems, it is not surprising that governments have sometimes been tempted to use the VET system as a social policy tool. It is clear, however, that these attempts are generally met with resistance by some of the actors who have a stake in the collective skill formation system, above all by employers (Bonoli and Emmenegger Citation2020; Carstensen and Ibsen Citation2020).

In general, governments have attempted to increase the integrative capacity of collective skill formation systems by developing interventions that do not directly interfere with the functioning of the system itself, such as remedial education. These measures tend to be external to the system and help disadvantaged youths find an apprenticeship position without interfering with the VET system proper. In a way, these external measures are invisible to employers (Bonoli and Wilson Citation2019).

There are however some examples in which governments have pushed the social policy logic into the collective skill formation system. Such initiatives are risky, and on occasions governments have had to step back, as the Danish case shows. Denmark increased access for disadvantaged youth to an extent that the reputation of the VET system declined and employers withdrew. In 2015 the government introduced grade requirements for VET making the system more selective again (Carstensen and Ibsen Citation2020). An alternative way to promote the inclusiveness of a VET system are win-win solutions that, while facilitating access to VET, also take into account firms’ requirements. Austria’s introduction of public workshops for youths who fail to obtain an apprenticeship position is an example for this. Employers appreciate the workshop because youths who have already completed the first year of an apprenticeship are less costly to train for firms (Seitzl and Unterweger Citation2019).

Overall, the room for manoeuvre available to public authorities wishing to use a collective skill formation system as an integration tool is limited. In particular, we expect interventions requiring an active involvement by employers to take the shape of win-win solutions, which are attractive to firms as well as to the government. One possibility, is to target occupations in which there is shortage of local candidates. In this case employer involvement may reflect a need to attract more candidates to given occupations.

Policy coordination

We believe that in order to understand the complex forms of cooperation needed for the provision of vocational training to refugees, the knowledge developed by scholars on collective skill formation can be usefully complemented by insights from the literature on policy coordination. The question of coordination has kept busy public policy specialists for decades, and the relevant literature is as a result considerably large (for recent overviews see Peters Citation2006; Tosun and Lang Citation2017; Trein, Meyer, and Maggetti Citation2019). For our purposes, we focus on studies that try to identify the factors that facilitate successful cooperation among actors in the production of a public policy (Weiss Citation1987; Ansell and Gash Citation2007; Trein Citation2016; Candel and Biesbroek Citation2016). We focus on two institutional dimensions that are likely to determine how successful policy coordination will be: responsiveness and distinctiveness (Trein Citation2016). Responsiveness refers to whether or not actors adjust to the needs and requirements of the other actor(s). Indicators of high responsiveness include for example regular communication and mutual learning processes whereas the absence of responsiveness occurs in instances of conflicts between actors (Trein Citation2016, 4). Distinctiveness instead considers more formal aspects and refers to the actors’ affiliation to different organisational entities. Distinctiveness is high when the actors who need to collaborate are located in different ministries or at different levels of a federal state. Conversely, distinctiveness is likely to be lowest when the collaborating actors belong to the same ministry or government department.

The responsiveness/distinctiveness approach provides a broad frame that can be refined with the insights of the more empirically oriented studies and adapted to the specificities of the policy area covered in this article: the provision of VET to refugees. With regard to distinctiveness, important aspects concern the location of the different actors whose coordination is needed. Is the coordination with non-state actors needed? Are there informal connections, for example resulting from previous collaboration, that reduce the effective weight of distinctiveness (Ansell and Gash Citation2007, p. 553)?

With regard to responsiveness, we consider specifically two sub-dimensions: interest alignment and flexibility by the initiator. Government departments and other organisations will be more successful in their cooperation efforts if the policy they need to implement reflects the interests of all the parties involved. We can think of various degrees of interest alignment. Interests can be identical (strongest) they can be convergent, they can be compatible or they can be divergent. The stronger the alignment of interests the more likely we are to find responsiveness and hence successful cooperation (Ansell and Gash Citation2007, p. 550; Gieve and Provost Citation2012, p. 62; Candel and Biesbroek Citation2016, 218).

Responsiveness can also be enhanced if the various agencies needed for policy implementation dispose of a certain degree of leeway, so as to adapt the new activities to fit in their own established procedures. In multilevel polities, it is also quite common for higher level jurisdictions to allow some scope to ‘customize’ policy implementation (Thomann and Zhelyazkova Citation2017). We call this ‘flexibility by the initiator’, and believe that an open attitude by the initiator, i.e. the willingness to adapt to the rules and procedures of the implementer(s) is conducive to policy coordination.

Hypotheses

The two strands of literature considered in this study allow us to formulate four hypotheses with regard to factors that are likely to facilitate/hinder the development of a programme that promotes access to VET for refugees in a collective skill formation system. We notice some overlaps between the two strands of literature. This is the case of the notion of win-win solutions and interest alignment, which we subsume under one single hypothesis. More generally, however, the combination of these two strands of literature allows us also to develop a more comprehensive theoretical framework for identifying the factors that allow the development of a programme for refugees in a collective skill formation system.

We would expect a programme for the integration of refugees via vocational training to be possible if:

The programme is not imposed upon actors, particularly (organised) employers, but is negotiated and accepted, otherwise employers will simply not participate. This is one of the basic lessons of studies on the adoption of pro-inclusiveness measures, and we expect it to be confirmed also in this case (Bonoli and Emmenegger Citation2020; Bonoli and Wilson Citation2019; Carstensen and Ibsen Citation2020; Durazzi and Geyer Citation2019).

The programme can be characterised as a win-win game, in the sense that it allows the various actors to pursue their own interests, which of course may be different. This hypothesis is based on insights from both the literature on collective skill formation systems and policy coordination. The win-win quality helps understand why employers will not oppose a given pro-inclusiveness measure. Interest alignment, in the language of the policy coordination literature, is likely to increase the responsiveness of the various actors participating in the win-win game (Ansell and Gash Citation2007, 550)

The programme can be customised (to an extent at least) so as to fit in with the established procedures of the various relevant actors needed for the implementation. This allows greater responsiveness by the various actors involved (Thomann and Zhelyazkova Citation2017)

The programme can rely on pre-existing forms of cooperation, or, as Ansell and Gash put it, ‘a prehistory of cooperation’ (Ansell and Gash Citation2007, 553).

Next, we consider these four hypotheses against the evidence provided by the development of the INVOL programme in Switzerland. Even though we focus on only one programme, we have more than one unit of observation. The programme, in fact, was developed at the federal level but had to be implemented by the cantons and needed the active involvement of private actors. This particular set up generates a large number of instances where successful coordination is needed and where our hypotheses can be tested.

3. A small miracle: the INVOL programme

Like other European countries, in 2015–2016 Switzerland experienced a substantial increase in the number of asylum applications. In 2015 it received nearly 40,000 applications, or twice as much as the long-term average. The increase was less sharp than in other European countries, but still significant (SEM Citation2016). The policy reaction was essentially based on existing legislation and practices, which meant some important delays in the treatment of the applications. During this period, most applicants came from four countries Eritrea, Afghanistan, Syria and Iraq, and benefitted of a relatively high rate of protection in excess of 80% in 2017 (Parak Citation2020).

In Switzerland, refugees and provisionally admitted persons are distributed among cantons in proportion to the local population, where they are allocated to municipalities. Cantonal responses to the wave of refugees varied, but included the provision of housing and additional programmes to support municipalities in the integration of refugees. In the largest German-speaking canton of Zürich, the asylum organisation (Asylorganisation Zürich, aoz) supports municipalities. Refugees receive a cash allowance covering their basic needs, medical treatment and housing (Zürich Citation2020). Aoz provides housing for about half of the refugee population. Cantonal programs in Zürich include language training, and educational courses and personal coaching. Similarly, in the largest French-speaking canton of Vaud refugees are assisted by the Centre social d’intégration des réfugiés (CSIR). CSIR establishes individualised integration plans for refugees, helping them with the housing, language acquisition and job integration (Etat Citation2020).

In the context of the refugee wave of 2015–2016, federal authorities decided to use the VET system as a tool to facilitate their integration into the labour market. A new programme, called INVOL,Footnote1 was developed by the federal office responsible for migration (SEM), and was implemented by a large range of state and non-state actors located at the subnational (cantonal) level. While cantonsFootnote2 were under no obligation to join the scheme, the majority of them did (eighteen out of twenty-six). SEM, and the cantons, were also able to obtain the participation of a number of professional training organisations (PTOs)Footnote3 and the involvement of a sufficient number of firms. In the end, in 2018 some 800 refugees were able to start a pre-apprenticeship programme based in professional schools and firms (interview SEM, Bern, 11/12/2018). While at first sight this may look like a limited number, experts in the field consider this outcome a remarkable achievement. Philipp Gonon, a leading expert on vocational training in Switzerland, called it a ‘small miracle’ (personal communication, 21/06/2019). This is understandable, precisely because of the immense coordination effort it required from federal and cantonal authorities from different departments, and, perhaps even more crucially, up to 800 firms. The programme turned out to be highly successful, as about two thirds of the refugees continued into a regular VET programme upon completion in 2019 (Staatssekretariat für Migration (SEM) Citation2020).

Our empirical analysis focuses on the decision-making process at the federal level and on the implementation in six cantons. We interviewed officials at the federal State Secretariat for Education, Research and Innovation (SERI) in charge of VET and the State Secretariat for Migration (SEM), responsible for migration. On the cantonal level, we carried out interviews with VET authorities in chosen so as to maximise inter-cantonal variation on dimensions known to play an important role in vocational training (see ). The first dimension of variation is language, as vocational training is more prevalent in the German speaking part of the country. We selected three German-speaking cantons (St.Gallen, Zurich and Basle-City) and three French-speaking Cantons (Vaud, Geneva and Jura). Second, we decided to vary the prevalence of vocational training as an educational path relative to academic education. Three cantons (St. Gallen, Zurich and Jura) are among those in which vocational training is most common. Basel City, Vaud and Geneva, instead, tend to rely more on academic education (STAT-TAB, interaktive Tabellen Citation2018). In both federal offices, and most of the cantonal vocational education offices and PTOs, there was only one person responsible for the implementation of the program. We selected these persons for the interviews. We also conducted interviews with PTOs, implementing the programme. We asked all of our interviewees with whom they cooperated during the implementation, and what challenges had to be overcome. The interviews were transcribed, summarised and then coded according to the categories implied by our theoretical framework.

Table 1. List of interviews.

The set-up of INVOL

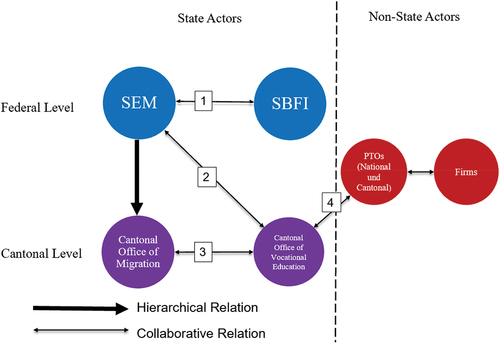

The implementation of INVOL required the collaboration of several actors. Training is provided in professional schools and by private or public employers. The curricula (content) of INVOL were designed by the PTOs. Professional schools belong to cantons or to PTOs. At the cantonal level, participants are pre-selected by the cantonal immigration authorities, but in most programs, employers choose their preferred candidates from within this preselection. The cantonal INVOLs are overseen by cantonal vocational training offices. shows the complexity of the programme.

The programme’s initiator, SEM, has very little direct control over actors whose collaboration is essential for the implementation of INVOL. In addition, the initiator is rather distant from the final implementers (essentially PTOs and firms). For the programme to be successful, the initiator needed to obtain the collaboration of all the actors involved. Of them, SEM has a hierarchical connection only to the cantonal offices for migration, based on the superiority of federal to cantonal law. The participation of all other actors needed to be obtained through persuasion.

Legend:

- SEM: Federal office responsible for migration

- SERI: Federal office responsible for vocational training

- PTOs: Professional training organisations

- CC.: Coordination challenge

In the following analysis, we break down this complex set-up into four distinct coordination challenges. The first three challenges involve one actor belonging to the migration policy field and one actor belonging to the field of vocational training. In the last challenge, we look at the involvement of private sector actors.

Coordination challenge #1 (CC1): The first challenge for the initiator (SEM) was to obtain the support or at least agreement for the development of the programme from SERI

Coordination challenge #2 (CC2): The second challenge refers to SEM obtaining the participation of the cantonal vocational training offices

Coordination challenge #3 (CC3): The third challenge takes place at the cantonal level and concerns the coordination among cantonal offices

Coordination challenge #4 (CC4): The fourth challenge concerns the involvement of private actors

Each of these four challenges required the involvement and agreement of at least two actors or two categories of actors.

Coordination challenge #1: the federal level (SEM and SERI)

The INVOL programme was approved by the federal government as a pilot for four years and equipped with CHF 54 million (approx. 50 million EUR). Upon the approval in December 2015, SEM was entrusted with the task of setting up a vocational training programme. This was not within their usual responsibilities. Vocational training is the responsibility of a different federal office, the ‘State secretariat of education, research and innovation’ (SERI). At first, SERI opposed the idea of a new, additional programme (interview SERI, Bern, 6/2/2019). SEM had proposed a programme leading to a nationally recognised diploma. At SERI, this was seen as a risk. If refugees could receive a vocational diploma through a shorter programme, this could reduce the value of the qualifications earned in the traditional programmes. The interviewee at SERI explained the risk in the following words:

The risk was a parallel programme to the regular vocational education tracks. A parallel programme, aimed at a specific group, that in the end should somehow be equivalent. (interview SERI, Bern, 6/2/2019).

SERI favoured the use of existing integration programmes (interview SEM, Bern, 11/12/2018, interview SERI, Bern, 6/2/2019). These were not specifically meant for refugees and as a result did not match the requirement by SEM to create a dedicated and clearly visible programme responding the political pressure to do something about the refugee crisis (interview SERI, Bern, 6/2/2010).

In September 2016, a compromise was reached between SEM, SERI, and the cantonal education directors (SBBK), as well as different PTOs (interview SEM, Bern, 11/12/2018). An additional one-year pre-apprenticeship programme was to be created, but without any formally recognised diploma at the end. The programme included an internship in a firm of at least eight weeks, a requirement that SEM considered non-negotiable (interview SEM, Bern, 11/12/2018). However, cantonal programmes were now also accepted, even though SEM had initially favoured national implementation (interview SEM, Bern, 11/12/2018). Cantons were also asked to complement the funding from SEM (CHF 13,000 per candidate/year) with own funds. Moreover, SERI obtained that candidates needed to fulfil certain language requirements before they could join a pre-apprenticeship (interview SERI, 6/2/2019).

How did SEM manage to overcome the initial opposition by SERI and obtain, if not SERI’s support, at least agreement for the programme? We can turn back to our framework. We expected private actors and particularly employers to be the main potential obstacle to attempts to use the VET system as an integration tool for refugees. In reality, employers did not need to mobilise at this early stage, and their interests were protected by SERI, the government office responsible for VET. Crucial aspects such as the protection of the value of VET degrees and the system’s reputation were key concerns of SERI who to an extent considers itself as the watchdog of the system (interview SERI, 6/2/2019).

Coordination challenge #2: SEM and cantonal vocational training authorities

At the federal level, SEM was responsible for convincing the cantons to participate. Eighteen out of twenty-six cantonal VET offices decided to implement the programme. However, initially the programme met with resistance from cantonal vocational education offices. Some of them were concerned that the programme would mean an easier track to a VET degree for refugees. Some cantonal offices also felt that INVOL did not fit well with the strategy they had already developed (interview SEM, Bern, 11/12/2018, interview SERI, Bern, 6/2/2019).

Two main factors played a role in convincing the cantonal VET offices. First, SEM was in the position to provide a financial incentive of CHF 13,000 (EUR 11,800) per candidate/year that was hard to ignore (interview SERI, Bern 6/2/2019, interview EHB, 01/04/2019). The requirement that each canton had to contribute matching funds was not strictly enforced. Similar programmes in the canton of St.Gallen cost around CHF 10,000 (EUR 9,050) per ten refugees per semester (interview St.Gallen, 9/4/2019). The impression is that INVOL was at least somewhat overfunded.

A second factor that was decisive in convincing cantonal VET offices to participate was the open attitude of SEM which allowed for customised implementation (Thomann and Zhelyazkova Citation2017). It showed willingness to accommodate cantonal differences. In particular, cantonal implementation differed along the main dimensions generally used to characterise vocational training systems: administration, type of skills taught and where these skills are taught. Such regional variation in pre-vocational education is quite common across different types of VET systems as a comparison of Scotland, Germany and Poland shows (Berger et al., Citation2012).

First, the cantonal programmes differ with respect to who runs them. The guidelines by SEM foresaw that the cantonal VET office be responsible for the implementation. This is the case for St.Gallen, Zurich, Geneva, Jura and Vaud, but not for Basel-City. In the canton of Basle-City the implementation of the programme lies with the cantonal office of social assistance (cantonal programme manager, Basle-City, 12/2/2019). The department of education had already expanded its programme portfolio in response to the wave of refugees and didn’t see the need for an additional programme. The office of social assistance, in contrast, saw the programme as a chance to further collaboration with other cantons, as well as with the private sector (cantonal programme manager, Basle-City, 12/2/2019).

Second, differences are considerable also with regard to the length of the practical training and the types of skills taught. Close to the guidelines by SEM are the programmes implemented in the cantons of Zurich, Vaud, Geneva and Jura. The apprentices work in a company for three days, and go to school during the rest of the week (cantonal programme managers, Zurich, 27/11/2018; Geneva, 20/04/2018; Delémont, 20/04/2018). St.Gallen’s implementation differs in that during the second semester, candidates work full time (cantonal programme manager, St.Gallen, 29/03/2018). Moreover, refugees are schooled in occupation-specific classes in certain cantons. In Zurich, St.Gallen, Basel, and Jura, refugees join a class only with candidates in the same occupational track. In contrast, in Jura, and Vaud, the classes are taught across occupations.

A third difference regards the actor who provides practical training. For some cantons where dual vocational education does not have a strong tradition, it was very difficult to convince private firms to provide practical training. Geneva has traditionally had a low rate of young people joining an apprenticeship after schooling, and these VET programmes are usually school-based, rather than dual. Against this background, Geneva implemented the INVOL-programme with 50% of the apprenticeship places in a public body responsible for the provision of social assistance and the integration of refugees (cantonal programme manager, Geneva, 2018).

Finally, one canton (Vaud), adopted a rather different version of the programme, consisting of a one-year extension of the standard three-year apprenticeship for the target group. Basically, eligible refugees have more time (2 years) to complete the first year of training and are then supposed to continue until they obtain the standard VET diploma. The programme was also given a different name in the canton of Vaud: ‘apprenticeship extension’ instead of ‘pre-apprenticeship’ (cantonal programme manager, Lausanne, 01/08/2018).

Cantons had much room for manoeuvre in deciding how to implement INVOL. The guidelines were not particularly stringent to start with. In addition, in the implementation, cantons were able to deviate from the guidelines, as long as the programme fit with the overall objectives of SEM. This flexibility was also a consequence of the salience of the topic. As SEM was under political pressure to adopt a new programme, it was arguably more responsive to cantonal needs.

Coordination challenge #3: cooperation across different cantonal offices

The third coordination challenge we examine is the cooperation between cantonal migration and VET offices. Cantons differed with respect to the degree of informal links between the two authorities. In the three German speaking cantons and in Jura, VET offices had expanded their provision for refugees before INVOL was launched. Links between cantonal migration and VET offices had already been established. In Vaud and Geneva, instead, INVOL generated new forms of collaboration.

Zurich had a pre-apprenticeship scheme for refugees in place before the national programme started. Planzer, a logistics company had initiated a one-year programme for refugees already in 2016. The programme had been established together with the national logistics PTO (ASVL) and a cantonal school specialised in the training of adults. For the implementation of the national programme relatively little additional coordination between the key actors was thus needed (cantonal programme manager, Zurich, 27/11/2018).

Similarly, in St.Gallen, the coordination between the VET and migration offices was established before the introduction of the national programme. At the peak of the migration wave in 2015, the cantonal migration office mandated the VET office to create programmes for refugees. In these programmes some coordination issues regarding work permits and salaries emerged and INVOL provided an opportunity to solve them (cantonal programme manager, St.Gallen, 29/03/2018).

In the French-speaking cantons, INVOL generated new forms of collaboration. While additional programmes to accommodate refugees had been created also in Jura, Geneva and Vaud, these did not involve firm-based training. Coordination between the VET offices and the migration offices was thus a new element.

In Geneva, the VET office and the cantonal office of migration worked together for the first time in the implementation of INVOL. Additional actors were the immigrant integration office, the PTOs as well as an organisation that provides career advice to adolescents (cantonal programme manager, Geneva 20/04/2018). Two dedicated bodies were created in order to oversee the programme: the steering committee, meeting three times a year to adjust the project, as well as a tripartite organisation including representatives of the cantonal government, employers and the trade unions.

In Jura, the coordination of INVOL was facilitated by a pre-existing programme that provided schooling to refugees. The school-based component in INVOL is provided by Avenir formation, a private school that had taught refugees already before (cantonal programme manager, Délémont, 20/04/2018). The coordination between the VET office and Avenir formation had thus already been established. For INVOL, two additional organisations were involved. The refugees are recruited by the cantonal association for the reception of migrants. Moreover, INVOL brought the population registry office as a new actor into the process. The coordination of all these actors required at least fifteen meetings.

In the three German-speaking cantons and, to some extent also in Jura, pre-existing collaboration facilitated the coordination necessary for the implementation of INVOL. However, in the French speaking cantons, especially Geneva and Vaud, coordination worked well despite the lack of such informal contacts. Pre-existing forms of collaboration facilitated the implementation of INVOL. This notion comes out very clearly form our interview data. However, the pre-existence of collaboration does not seem to be a necessary condition as two cantons where such collaboration was minimal or inexistent (Geneva and Vaud) managed to set up programmes within the same time frame and with a similar reach as the other cantons.

Coordination challenge #4: Cooperation with Non-State Actors

In order to implement INVOL, the involvement of the private sector was essential. Two types of private actors were needed: PTOs and individual firms. PTOs are a crucial actor in at least two respects: they are responsible for designing the curriculum of the various occupations covered by INVOL and they can play an important role in convincing individual firms to participate. Firms, finally, are also a crucial actor because that’s where a big part of the training must take place.

On paper, coordination challenge # 4 could have been the most difficult. It is the only coordination challenge that requires non-state actors to play a proactive role in the implementation of INVOL. As we saw above, non-state actors (i.e. employers and their representatives) are generally rather sceptical when governments want to use VET as a social policy. In reality, the opposite happened and the coordination between state authorities and private sector actors, particularly PTOs, proved rather unproblematic.

First, and perhaps rather surprisingly, in some cantons it was the PTOs or even individual firms who contacted the cantonal VET office with a proposal for involvement in the programme. This was the case in the larger cantons and in those which had a strong tradition of dual VET, like Zurich and St Gallen. In Zurich several PTOs approached the cantonal VET office and offered to develop a curriculum (cantonal programme manager, Zurich, 27/11/2018). The result was that Zurich provided INVOL in nine different occupational fields: logistics, automobile, maintenance, retail trade, gardening, catering, building technology, cleaning and rail construction. Similarly, individual firms started contacting the VET office in St.Gallen, offering individual training slots of the national programme (cantonal programme manager, St.Gallen, 29/03/2018). The VET office asked individual firms to join forces with other enterprises in their sector with the help of PTOs. Two sectors were able to do so: construction and catering. Both of these PTOs, in addition to developing a curriculum, provided help in finding training slots within individual member-firms. As the representative of a PTO active in the construction sector told us:

I have to reach many employers in the canton, so that we can place the refugees close to their home. Probably I’ll just have to call the 14 employers that happen to be where we need them and tell them: I presented the programme some time ago, now I have a refugee close to your business – take him in please (Interview with representative from Polybau, 13/3/2018).

In the other cantons, it was more difficult to find interested PTOs, because there is not a large tradition in dual vocational education, or because the cantonal economy is less apt to absorb low-skilled labour (cantonal programme manager, Basle-City, 12/2/2019). The canton of Basel-City is known for hosting some of Switzerland’s most renowned pharmaceutical companies. However, this industry is quite knowledge intensive, and did not see much interest in a programme targeting refugees. For the office of social assistance, it was therefore evident from the start that they would send refugees to other cantonal programs (cantonal programme manager, Basle-City, 12/2/2019). The development of the curricula and contacting the enterprises was done via the respective PTOs in the neighbouring cantons.

In Geneva, Vaud and Jura, cantonal offices were more active in developing curricula and recruiting firms. In Geneva, a canton with a less strong tradition in dual vocational training, it was the cantonal office of vocational training who started contacting PTOs, rather than the other way around. The curricula were developed predominantly in cooperation with cantonal PTOs. Similarly, in Vaud, the local employers’ association complemented the efforts of cantonal offices to motivate the firms to participate (cantonal programme manager, Lausanne, 01/08/2018). In the canton of Jura, the VET office developed the curricula itself, with the input of different enterprises. Umbrella associations of business, such as the local chamber of commerce, were important partners, as they promoted the programme among their members (cantonal programme manager, Delémont, 20/04/2018).

In the end, getting private actors on board turned out not to be so difficult. However, our case studies show that PTOs showed different degrees of enthusiasm for the programme. The PTOs providing training in occupations located at the lower end of the skill distribution, i.e. catering, cleaning, logistics, and construction were the most inclined to collaborate. These are occupations where it is more difficult to find suitable and motivated candidates locally. The inflow of refugees was arguably seen as an opportunity for firms of these sectors, hence the proactive role played by the PTOs. As the responsible person for a PTO in the construction sector put it:

I sell INVOL with reference to our responsibility to integrate, but also as an opportunity for our sector. There is nothing to lose here. If the refugees do not fit the requirements, then it doesn’t work, and if they are good, they can work for us. So, it is actually a win-win situation (Interview with representative from Polybau, 13/3/2018)

PTOs providing training in more intellectually demanding and popular fields, in contrast, for the most part declined to participate in INVOL. INVOL is not available in the most popular occupation, office clerk, nor ICT. Recruitment difficulties thus certainly played a big role in explaining the willingness of private actors to participate in INVOL.

In relation to the challenge of involving private actors, what seems to explain success relates very much to the notion of a win-win quality of the programme. The win-win quality was strong for occupations located at the low end of the skill distribution, where firms have difficulties recruiting suitable candidates locally. But then PTOs played an important role in persuading firms to join the programme.

Discussion and conclusion

Between 2015 and 2018 the federal and cantonal authorities together with professional training organisation and employers developed a one-year pre-apprenticeship programme meant to facilitate access to standard apprenticeships for refugees. The initiative was successful, as in 2018 some 800 refugees were able to enter the programme. At first sight, the adoption of INVOL contradicts much of what we know about the usage of collective skill formation systems as social policies (Bonoli and Emmenegger Citation2020). In fact, the measure is not external to the system as it requires the active involvement of employers, both when organised in professional training organisations and as individual firms needed to provide the practical part of the training. In addition, the programme targets a group, refugees, that is among the most difficult to integrate in the labour market. And finally, it requires the collaboration of a large number of actors, located within different government departments and levels of the federal state, as well as private actors. How was this possible?

In line with what we know about the way in which collective skill formation systems work, and with our first hypothesis, INVOL was not imposed. Cantons, PTOs, individual firms had the option to participate and were not penalised for not participating. A first version of the programme, that could have posed a problem to some of these actors, was de facto successfully vetoed by SERI, the federal office in charge of overseeing the good functioning of the whole VET system.

Our detailed account of how INVOL was eventually adopted reveals a number of factors that seem to have played a crucial role in making it possible. INVOL, when successful, was regarded as a win-win solution (second hypothesis). In several instances, when asked about the reasons for participating the actors we interviewed had some obvious reasons to do so. For some PTOs, it was difficulty to recruit locally. For some institutional actors, it was an opportunity to expand their reach beyond the usual policy fields. The subsidy, and the fact that the programme was probably overfunded, made it easier to convince cantonal actors and PTOs. The impression is that participating actors had different but equally strong reasons to join the programme.

Furthermore, the programme initiator (SEM), was extremely flexible with regard to the details of implementation, which, allowed for customised implementation (third hypothesis). This flexibility was visible in the initial phases, i.e. the negotiations with SEM, but also in the negotiations with the cantonal offices. As we saw above, the cantons could clearly benefit from customised implementation. The guidelines provided by SEM were rather broad to start with, and, on top of that, cantonal programmes that did not follow all the guidelines were nonetheless accepted. According to the interview evidence we collected, high flexibility was instrumental in getting the programme running in a majority of cantons.

Our fourth hypothesis, inspired from the literature on policy coordination (pre-existing forms of cooperation), did not find confirmation in our empirical study. INVOL developed in a similar way in settings which had collaborated before and in those with no such experience. This does not mean that the pre-existing cooperation did not facilitate the development of INVOL. On the contrary, many interviewees mentioned previous cooperation as an important facilitating factor. However, this factor does not emerge as a necessary condition.

While we adopted a deductive research design, we were open to uncover additional relevant factor emerging from the empirical analysis. On the basis of our interviews and on the reconstruction of the policy process, we were able to identify at least one additional important factor: political salience. As images of refugees coming to Europe were still vivid in people’s memory, many actors were under pressure to cooperate and contribute to the programme. While we can only speculate for lack of a suitable counterfactual, it is possible that such a successful cooperation would have been more difficult in the absence of strong political and media pressure to do something to integrate refugees.

These results were obtained in a country, Switzerland, that is characterised by some of the most decentralised governance structures, within the field of vocational training, but also in policy in general. As a result, one should be cautious in assuming that the observed effects will be present in other contexts as well. However, we expect at least some of the mechanisms we highlight to be relevant also in other countries with a collective skill formation system, such as Germany, Austria, Denmark and the Netherlands. In these countries we would expect the development of a refugee integration programme that requires the active cooperation of employers to face similar challenges.

In conclusion, this study confirms and refines the main findings of the literature on the pro-inclusiveness dimension of collective skill formation systems. What we observed confirms the view that pro-inclusiveness measures are viable only if they are external to the system or if they are seen as win-win games by the main actors, particularly by employers and their organisations. The first ideas that were floated, which included a parallel vocational track for refugees, would have been extremely challenging for the system. The programme that was eventually adopted, INVOL, was considerably less intrusive, but still required employers’ involvement. Employers saw a clear interest in participating, most likely related to difficulties recruiting locally. A generous subsidy was key to convince cantons, who then played an important role in getting PTOs on board.

Our study also shows that complex policy environments, like those that are called upon to produce integration measures within a collective skill formation system, can benefit from the knowledge developed by scholars of public policy coordination. More generally, we believe that scholarship on collective skill formation systems could be enhanced by including a focus on the mechanisms highlighted in the policy coordination literature.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Annatina Aerne

Annatina Aerne is a postdoc researcher at the Swiss graduate school of public administration University of Lausanne. She has worked on network analysis and on migration and vocational training.

Giuliano Bonoli

Giuliano Bonoli is Professor of social policy at the Swiss graduate school for public administration at the University of Lausanne. He is interested in the issue of access to VET for potentially disadvantaged groups. He has published some thirty articles in journals such as Politics & Society, Journal of European Public Policy, European Sociological Review, Comparative Politics, Comparative political studies. He is the author of The Origins of Active Social Policy: Active Labour Market Policy and Childcare in a Comparative Perspective (Oxford University Press, 2013).

Notes

1. Integrationsvorlehre (Integration pre-apprenticeship). For a presentation of the Swiss VET system, see Gonon Citation2002.

2. Switzerland is a federal country, made up of twenty-six member-states called cantons. Federalism in Switzerland is strongly decentralised, with the cantons having large competences in many policy areas such as education and social policy (Vatter Citation2014). Migration policy is a joint federal cantonal competence (Lavenex and Manatschal Citation2014).

3. Professional training organisations are collective associations of mostly employers that make a substantial contribution to the infrastructure of the Swiss vocational training system. They prepare the curricula of the various vocational training programmes, and in some cases run their own professional schools. Professional training organisations are known in Switzerland as Organisationen der Arbeitswelt (OdA)/Organisations du monde du travail (OrTra).

References

- Ansell, C., and A. Gash. 2007. “Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 18 (4): 543–571. doi:10.1093/jopart/mum032.

- Berger, S., R. Canning, M. Dolan, S. Kurek, M. Pilz, and T. Rachwal. 2012. “Curriculum-making in Pre-vocational Education in the Lower Secondary School: A Regional Comparative Analysis within Europe.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 44 (5): 679–701. doi:10.1080/00220272.2012.702223.

- Bevelander, P. (2016). “Integrating Refugees into Labor Markets”. “ IZA World of Labor no. 269.

- Bonoli, G., and P. Emmenegger. 2020. “The Limits of Decentralised Cooperation. The Promotion of Inclusiveness in Collective Skill Formation Systems.” Journal of European Public Policy, Forthcoming. doi:10.1080/13501763.2020.1716831.

- Bonoli, G., and A. Wilson. 2019. “Bringing Firms on Board. Inclusiveness of the Dual Apprenticeship Systems in Germany, Switzerland and Denmark.” International Journal of Social Welfare 28 (4): 369–379. doi:10.1111/ijsw.12371.

- Brell, C., C. Dustmann, and I. Preston. 2020. “The Labor Market Integration of Refugee Migrants in High-Income Countries.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 34 (1): 94–121. doi:10.1257/jep.34.1.94.

- Busemeyer, M., and C. Trampusch. 2012. The Political Economy of Collective Skill Formation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Candel, J. J. L., and R. Biesbroek. 2016. “Toward a Processual Understanding of Policy Integration.” Policy Sciences 49 (3): 211–231. doi:10.1007/s11077-016-9248-y.

- Carstensen, M. B., and C. L. Ibsen. 2020. “Three Dimensions of Institutional Contention: Efficiency, Equality and Governance in Danish Vocational Education and Training Reform.” Socio-Economic Review,in press.

- CEDEFOP. 2019. Creating Lawful Opportunities for Adult Refugee Labour Market Mobility. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- Chadderton, C., and C. Edmonds. 2015. “Refugees and Access to Vocational Education and Training across Europe: A Case of Protection of White Privilege?” Journal of Vocational Education & Training 67 (2): 136–152. doi:10.1080/13636820.2014.922114.

- Culpepper, P. 2003. Creating Cooperation How States Develop. Human Capital in Europe. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Durazzi, N., and L. Geyer. 2019. “Social Inclusion in the Knowledge Economy: Unions’ Strategies and Institutional Change in the Austrian and German Training Systems.” Socio-Economic Review 18 (1): 103–124. doi:10.1093/soceco/mwz010.

- Emmenegger, P., L. Graf, and C. Trampusch. 2019. “The Governance of Decentralised Cooperation in Collective Training Systems: A Review and Conceptualisation.” Journal of Vocational Education & Training 71 (1): 21–45. doi:10.1080/13636820.2018.1498906.

- Etat de Vaud (2020). “Améliorer l’intégration des réfugiés”. Retrieved from https://www.vd.ch/toutes-les-autorites/departements/departement-de-la-sante-et-de-laction-sociale-dsas/direction-generale-de-la-cohesion-sociale-dgcs/projets-et-actualites/news/11712i-ameliorer-lintegration-des-refugies/

- Gieve, J., and C. Provost. 2012. “Ideas and Coordination in Policymaking: The Financial Crisis of 2007-2009.” Governance: An International Journal of Policy, Administration, and Institutions 25 (1): 61–77. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0491.2011.01558.x.

- Gonon, P. 2002. “The Dynamics at Reform of the Swiss Vocational Training System.” In Towards a History of Vocational Education and Training (VET) in Europe in a Comparative Perspective, edited by Cedefop. Luxembourg: Cedefop, 88–99.

- Lavenex, S., and A. Manatschal. 2014. “Migrationspolitik.” In Handbuch der Schweizer Politik, edited by P. Knoepfel, Y. Papadopoulos, P. Sciarini, A. Vatter, and S. Häusermann, 671–694. Zurich: NZZ Verlag.

- Manhica, H., L. Berg, Y. B. Almquist, M. Rostila, and A. Hjern. 2019. “Labour Market Participation among Young Refugees in Sweden and the Potential of Education: A National Cohort Study.” Journal of Youth Studies 22 (4): 533–550. doi:10.1080/13676261.2018.1521952.

- Parak, S. 2020. La pratique en Suisse en matière d’asile, 1979-2019. Bern: Swiss state secretariat for migrations.

- Peters, G. 2006. “Concepts and Theories of Horizontal Policy Management.” In Handbook of Public Policy, edited by P. GPaJ, 115–138. London: Sage.

- Protsch, P., and H. Solga. 2017. “Going across Europe for an Apprenticeship? A Factorial Survey Experiment on Employers’ Hiring Preferences in Germany.” Journal of European Social Policy 27 (4): 387–399. doi:10.1177/0958928717719200.

- Ryan, P. 2001. “The School-to-Work Transition: A Cross-National Perspective.” Journal of Economic Literature 39 (1): 34–92. doi:10.1257/jel.39.1.34.

- Seitzl, L., and D. Unterweger (2019) Declining collectivism at the higher and lower end, “Workshop “Collective Skill Formation Systems in the Knowledge Economy” St Gallen”, 21-22 November 2019.

- SEM. 2016. L’asyle en chiffres 2015. Bern: Swiss state secretariat for migrations.

- Staatssekretariat für Migration (SEM). (2020). “Erfolgreicher Start der Integrationsvorlehren für Flüchtlinge und vorläufig Aufgenommene”. Retrieved from https://www.sem.admin.ch/sem/de/home/aktuell/news/2019/2019-05-27.html

- STAT-TAB, interaktive Tabellen. (2018). Retrieved from: https://www.pxweb.bfs.admin.ch/pxweb/de/px-x-1502020000_101/px-x-1502020000_101/px-x-1502020000_101.px/table/tableViewLayout2/?rxid=cd9a0069-e07b-486b-a41b-c965096fda75

- Thomann, E., and A. Zhelyazkova. 2017. “Moving beyond (Non-)compliance: The Customization of European Union Policies in 27 Countries.” Journal of European Public Policy 24 (9): 1269–1288. doi:10.1080/13501763.2017.1314536.

- Tosun, J., and A. Lang. 2017. “Policy Integration: Mapping the Different Concepts.” Policy Studies 38 (6): 553–570. doi:10.1080/01442872.2017.1339239.

- Trein, P. 2016. “A New Way to Compare Horizontal Connections of Policy Sectors: “Coupling” of Actors, Institutions and Policies.” Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice,19 (5): 419–434.

- Trein, P., I. Meyer, and M. Maggetti. 2019. “The Integration and Coordination of Public Policies: A Systematic Comparative Review.” Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice 21 (4): 332–349.

- Vatter, A. 2014. “Föderalismus.” In Handbuch der Schweizer Politik, edited by P. Knoepfel, Y. Papadopoulos, P. Sciarini, A. Vatter, and S. Häusermann, 119–144. Zurich: NZZ Verlag.

- Weiss, J. A. 1987. “Pathways to Cooperation among Public Agencies.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 7 (1): 94–117. doi:10.2307/3323353.

- Zschirnt, E., and D. Ruedin. 2016. “Ethnic Discrimination in Hiring Decisions: A Meta-analysis of Correspondence Tests 1990–2015.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42 (7): 1–19. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2015.1133279.

- Zürich, A. A. (2020). “Sozialhilfe für Asylsuchende und vorläufig aufgenommene Ausländer/innen”. Retrieved from https://www.stadt-zuerich.ch/aoz/de/index/sozialhilfe/fuersorge/asylsuchende.html