ABSTRACT

Online instructional videos have been presented as an efficient instructional method in workplace learning and vocational education and training (VET). Increasingly, public video-sharing sites like YouTube are used by firms, educators and learners to teach and learn about work practices, new work roles and skills. However, more knowledge is needed about what instructional videos exist and how they facilitate vocational learning. This article draws from online video research to explore vocational learning on YouTube for interactive service work. Focusing on connected service encounters in which transactions and customer service are intertwined through interaction with digital technologies, cashier work was used as the empirical case. With concepts from narrative and multimodal analysis, the theory of practice architectures was the framework for analysing 160 YouTube videos for cashier work. The article proposes a taxonomy of online instructional video types for VET and workplace learning comprising nine video types divided into two main categories: professional instructional videos and peer instructional videos (vlogs). It is found that transactions and customer service are instructed separately. Consequently, YouTube videos do not yet prepare learners for connected service encounters. Overall, the taxonomy can contribute to a more purposeful use of video in VET and workplace learning.

Introduction

Digitalisation, automation, disruption and crisis constantly transform firms, work, society and how people learn. As new work patterns emerge, employees must update their competencies to maintain their employability and contribute to innovation in their work organisations (Ifenthaler Citation2018). These changes necessitate continuous adaptations to the content and delivery of vocational education and training (VET) and workplace learning (Avis et al. Citation2021; Fischer et al. Citation2018). For instance, advancements in affordable digital technologies and expanding Internet and social media access in the past two decades have made learning spaces more flexible and changed the boundaries between learning spaces (Butcher and Ferguson Citation2021). Fischer and Barabasch (Citation2021) argue that new work conditions are conducive to creativity. Therefore, divergent thinking should be supported through creativity techniques in schools and workplace learning. For example, commercial clerks could use self-made videos to introduce employees to digital tools, and care specialists could create games guiding children through difficult situations (Fischer and Barabasch Citation2021).

However, the COVID-19 pandemic and global disruptions have revealed that the work and lives of service workers can change overnight. The digitalisation and automation of front-line service has accelerated the transformation of service encounters (face-to-face interactions) in the service sector (Larivière et al. Citation2017; Voorhees, Fombelle, and Bone Citation2020). Consequently, the organisation of workplaces and interactive service work (henceforth, service work) is changing. VET has been called upon to adapt to digital transformation and COVID-19 in addressing the educational needs of the most vulnerable, for instance in retail trade (Avis et al. Citation2021; OECD Citation2020).

This article explores digital VET for retail work in the connected service encounter through the lens of YouTube instructional videos for cashier work. Connected refers to service encounters involving interactions with digital technologies such as a modern point of sale (mPOS) system and the Internet (Arkenback Citation2022). POS is the place and time when a retail transaction is completed, and mPOS system refers to the digital retail management system or network comprising cloud-based software (e.g. POS, inventory, customer management) and hardware (e.g. scanner, card reader, square, laptop) used in the checkout transaction process.

The exponential expansion of online video production and viewing in the 2010s piqued the interest of researchers, educators and the public in using online videos for instructional purposes. Snelson and Perkins (Citation2009) and Bonk (Citation2011), amongst others, predicted that online instructional videos published on public video-sharing sites such as YouTube will transform teaching and learning. That is, learning content will be designed by ordinary people, learners and students, not formally authored by organisations or educational institutions. Nonetheless, little is known about how YouTube instructional videos correspond to changing frontline employee requirements and roles in service work. Furthermore, a review of related research suggested that online instructional videos have various names (see ). For instance, educational-, lecture-, explainer-, training- and tutorial videos were commonly mentioned, often interchanged, defined differently – and sometimes not defined at all. This raises questions about whether these terms refer to online methods for delivering VET and employee training and whether there are diverse types of videos with specific purposes.

Table 1. Examples of concepts for describing instructional videos in the literature.

This article draws from online video research to explore YouTube regarding vocational learning for cashier work. It is guided by these research questions:

What types of instructional videos concerning cashier work exist on YouTube?

How do different instructional video types mediate vocational skills and facilitate vocational learning for connected service encounters?

Herein, instructional video is an umbrella term encompassing videos that train, instruct, inform and orient learners towards a particular work practice, vocation, profession or work activity (cf. Carpenter Citation1953; Köster Citation2018). The article contains five components. First, it introduces online instructional videos for vocational learning and service encounters as concepts. Second, it elucidates the framework informing the analysis, namely the theory of practice architectures. Third, it delineates the research method and key analytical process. The fourth section summarises key results regarding YouTube instructional video types related to cashier work and proposes a taxonomy. The final section offers conclusions regarding vocational learning on YouTube related to the connected service encounter based on the taxonomy of video types. It also discusses the use of YouTube videos in VET, limitations and future avenues for research.

Online instructional videos for vocational learning

A plethora of public instructional videos are published on YouTube, such as tutorials for ‘do-it-yourself’ activities (Biel and Gatica-Perez Citation2011; Julian et al. Citation2020), clinical skills training videos for medical education (Topps, Helmer, and Ellaway Citation2013) and videos for blended e-learning in training organisations (Callan, Johnston, and Poulsen Citation2015). Callan and Johnston’s (Citation2020) study of social media adoption in Australian VET institutions demonstrated that YouTube’s features are compatible with institutional objectives and values aligned with more self-paced, collaborative and student-focused learning. Notably, teachers in trade programmes identified a preference for YouTube amongst apprentices to learn ‘hands-on practical skills’ and a ‘stage-like problem-solving process in delivering a skill and completing a task’ (Callan and Johnston Citation2020, 12).

Learning by observing and imitating professionals is fundamental for workplace learning (Billett Citation2014), and instructional films are based on observational learning, or modelling (Pieter, Tabbers, and Paas Citation2007). Learning motor and interpersonal skills by watching a video of people modelling desirable actions and behaviours has been a successful, well-researched instructional technique since the 1920s (Wiatr Citation2002). For instance, after World War II, corporations made human relations training films to shape managers’ and workers’ emotional lives, influencing their social behaviours and class identification within and beyond the workplace (Solbrig Citation2007). Such training films provide ‘a case study of how social science was transformed through media into social practice: first as fictional narratives to be absorbed by managers, ultimately as social scripts to be performed in the workplace’ (Solbrig Citation2007, 31). Hence, current online instructional videos for service work can be assumed to be shaped by historical instructional videos (Hediger and Vonderau Citation2009; Reiser Citation2001).

Increasing research has explored characteristics of online instructional videos in higher education settings and how to measure the effectiveness of video types and maximise student learning outcomes (e.g. Köster Citation2018). Despite more interest in using online instructional videos in workplace learning and VET, the field still understands little about how various online video types or styles can facilitate vocational learning (Dobricki, Evi-Colombo, and Cattaneo Citation2020; Köster Citation2018). Furthermore, many existing taxonomies are based on videos used for teaching theoretical subjects (Köster Citation2018). Such taxonomies commonly draw on features from three modalities, namely audio, text and visual (herein, external narrative characteristics). However, few studies have addressed internal narrative characteristics, such as purpose, narrative discourse and story, concerning the vocation and skills to be learned.

Service work: the service encounter

In post-industrial societies, service work evolved as a ‘game between persons’ (Bell Citation1973, 576), specifically service employees and customers, or professionals and clients. Originally, the service encounter was defined as ‘the dyadic interaction between a customer and a service provider’ (Surprenant and Solomon Citation1987, 87).

These interactions are driven by learned demeanours relevant to specific situations (i.e. roles) and formulated in the organisation’s service script (Solomon et al. Citation1985), a detailed guide for playing the employee role in this service game. Simultaneously, in the retail sector, the introduction of computerised cash registers and POS systems, barcodes and scanners automating transactions digitalised the service encounter (Basker Citation2016) and transformed service occupations (Webster Citation2004).

Research on the service encounter has developed in disciplines ranging from service, marketing, human resources management, service work and hospitality to organisational frontlines. However, it appears there have been few exchanges between fields. For instance, service work researchers have targeted service workers’ ‘emotional labour’ (Hochschild Citation2018) – work and skills that transcend their physical or cognitive duties – in service encounters (Ikeler Citation2016). Emotional labour is the process by which workers are expected to manage their feelings (i.e. conjure or repress specific emotions) in service encounters according to the employer’s rules and guidelines (Hochschild Citation2018). In recent work on workplace learning in service encounters, Arkenback (Citation2022) found the connected service encounter is ‘a game between the frontline employee, technology and customer’ characterised by ‘postdigital dialogue’, meaning it is neither organic nor digital; rather, it is both. Furthermore, frontline employees and technology were found to play new roles in the connected service encounter.

In practice and in service, management and marketing research, definitions of the service encounter and roles of frontline employees have radically changed since the 1980s. For example, since around 2000, digital technologies have substituted for and complemented frontline employees as service providers (Rust and Huang Citation2014). Organisational professionalism has replaced occupational professionalism based on client-centred values (Colley Citation2012). Increasingly, the service encounter as a dyadic interaction between a firm and a customer has been interpreted as a digital service ecosystem (Bowen Citation2016). From this perspective, frontline employees and customers are human actors in service systems structured around digital technologies (e.g. artificial intelligence, robots), multi-actor service systems and networks with multiple service providers (Larivière et al. Citation2017).

The literature’s image of the service encounter is fractured, with a lack of sustained research about learning to labour with feeling (Colley Citation2006; Benozzo, Colley, and Benozzo Citation2012) and training for technology-infused service encounters.

Analytical framework

The analytical framework for analysing video narrative characteristics encompasses the theory of practice architectures (henceforth only TPA) and concepts emerging from this theory (Kemmis et al. Citation2014; Kemmis Citation2019) combined with concepts from narrative research (Squire et al. Citation2014) and multimodal analysis (Bezemer and Jewitt Citation2010). The term ‘narrative’ is used in everyday life and research and has various definitions. Many narrative researchers use ‘narrative’ interchangeably with ‘story’. However, distinguishing the two terms is helpful ‘to contrast the “what” of “stories” (content) with the “how and why” of “narratives” (structure, context)’ (Squire et al. Citation2014). In this analytical framework, the concept of ‘story’ is employed to analyse the videos’ internal narrative characteristics. Furthermore, the instructional video story is conceptualised as a practice.

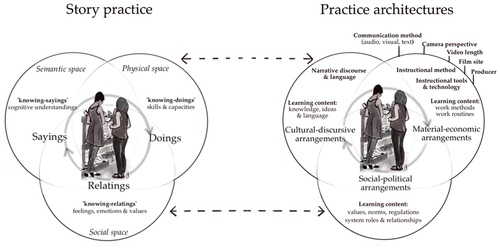

In TPA, the social world constitutes three overlapping dimensions, namely semantic, physical and social, wherein we encounter each other and the world in practices. Likewise, a practice is understood as a three-dimensional social encounter, composed of combinations of practitioners’ ‘sayings’, ‘doings’ and ‘relatings’ intertwined in the practice’s purpose (Kemmis et al. Citation2014). Theoretically, the video story comprises ‘sayings’, ‘doings’ and ‘relatings’, modelling the cashier’s knowledge and skills in work situations or activities. To consider and expand the characteristics of emotional labour skills (cf. Ikeler Citation2016), this article adopts Kemmis’s (Citation2019, 124) view that there are three kinds of knowledge, namely knowing-sayings, knowing-doings and knowing-relatings. With this understanding of vocational skills, the video story can mediate knowing-sayings (‘knowing that’; propositional knowledge) that are evident in the cognitive understandings of the practice communicated by the narrator and actors; knowing-doings (‘knowing how’; procedural knowledge) that are evident in the skills and capabilities demonstrated by the actors; and knowing-relatings (knowing how to position oneself in the social relations in a practice; relational, affective and emotional understandings: knowing how to relate to others in the social situation) evident in the feelings, values and relationships communicated in the story (see ).

Furthermore, TPA regards practices as evolving in relation to different conditions, or ‘practice architectures’, which are theoretically divided into ‘cultural-discursive’, ‘material-economic’ and ‘social-political’ arrangements found in or brought to a site (Kemmis et al. Citation2014). These arrangements enable and constrain participants’ sayings and doings, as well as how they relate to each other and the world through social practices. In this framework, the ‘how and why’ of the video narrative is conceptualised as the practice architectures forming the video’s story. For example, this encompasses the video producer’s understanding of the service encounter and cashier work (cultural-discursive arrangements), proper work methods (material-economic arrangements), and values, norms, attitudes and roles influencing the cashier’s service encounters (social-political arrangements). The video’s external narrative characteristics are conceptualised as the following material-economic arrangements: the producer, video length, film site, camera perspective and communication method (audio, text, visual).

Methodology

This study was conducted using online videos as the primary data source, referred to as online video research (Legewie and Nassauer Citation2018). Instructional videos related to service work involving transactions were gathered on YouTube between June 2018 and June 2021. The following five criteria guided the selection of videos: 1) educational purpose, meaning that the video must instruct, describe or demonstrate cashier skills relevant to tasks, situations or processes in cashiers’ work practice; 2) English or Nordic languages; 3) publisher and producer information; 4) videos produced in the 20th century, as historical videos can contribute valuable information about the narrative characteristics of contemporary online video types; and 5) public and views. Legewie and Nassauer (Citation2018) suggest that users’ expectations and the extent of online traffic are two measures by which to assess potential consent, privacy and confidentiality concerns in online video research. For example, a video that 100,000 people have viewed can be regarded as more ‘public’ than videos viewed by 100 people. This study established more than 1,000 views as a guideline for including videos produced in the 2010s. However, most videos in the sample had garnered over 30,000 views.

The sampling of videos was initiated by creating a private library on YouTube. Combinations of keywords related to cashier work and training (e.g. checkout, cashier, register, POS, training) were then used to search for videos. To fulfil the aim of including instructional videos produced in the 20th century in the data material, the keywords were combined with decades (e.g. ‘cashier pay desk training 1980s’). The sample selected for detailed analysis consisted of 160 instructional videos produced between 1917 and 2020 ().

Table 2. The data material.

Analysis process

The data material was analysed in a four-step process. In the first step, the videos’ external narrative characteristics were analysed. For this purpose, a template (1) was developed based on TPA and concepts from multimodal theory (see Appendix A). The date, title, producer, production year, video length, publication date, views and URL were documented in the template. Thereafter, each video was viewed iteratively, focusing on material-economic arrangements shaping the video (e.g. audio, visual, text, film site). Based on the results and previous research classifying online instructional videos (Köster Citation2018; Van der Meij and Van der Meij Citation2013) and YouTube videos (Biel and Gatica-Perez Citation2011), five tentative rubrics were constructed: training, lecture, tutorial, screencast and vlog. The videos were then recategorised accordingly and organised chronologically in the YouTube library.

In the second step, another template (2) based on TPA and narrative methods was developed to analyse the internal narrative characteristics, or the videos’ story (sayings, doings, relatings), and the practice architectures that shaped the story (see Appendix A). Seventy-five videos produced between 1917 and 2020 that represented the five categories were selected for detailed analysis. Each video was viewed iteratively, and complete sequences or segments of oral dialogue were transcribed verbatim and accompanied by screenshots. Subsequently, five sub-categories for vlogs were constructed: experience, tutorial, gaming, workday and lecture. The third step focused on analysing the knowledge (knowing-sayings, knowing-doings, knowing-relatings) mediated to understand the purpose of the video. Finally, the results were summarised in a taxonomy of YouTube instructional video types and assessed against the remaining 85 videos in the sample produced between 2010 and 2020, and some adjustments were made.

Results

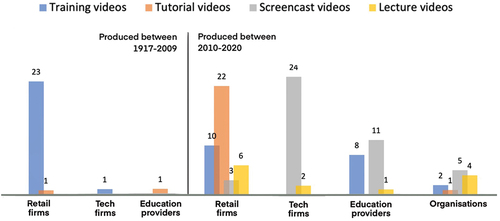

Two main instructional video categories were identified: professional and peer. Professional instructional videos (n = 125) were produced by retail firms, tech firms, education providers (universities, colleges, online corporate training, VET organisations) and organisations (municipal service, social service, employment service, trade unions). The analysis of the video narratives’ external and internal characteristics revealed four distinct professional video types: training, tutorial, screencast and lecture video; these are described in greater detail in the next section. The chart in illustrates that between 1917 and 2009, the training and tutorial video types dominated cashier training in workplace learning, which aligns with the video types identified in industrial film research (cf. Carpenter Citation1953; Solbrig Citation2007). In the 2010s, two new professional video types for cashier training appeared on YouTube: screencast and lecture. illustrates that retail firms are by far the greatest (52%) producers of professional instructional videos related to cashier work, while education providers only account for 16%. One characteristic distinguishing the training and tutorial videos from the screencast and lecture videos is that the former two model on-the-job situations and at-the-job activities. Thus, it can be assumed that the training and tutorial video types model the cashier’s role, skills and duties in the connected service encounter. A summary of the characteristics of professional online instructional videos for service work is provided in Appendix B.

Figure 2. Professional instructional video types for cashier work produced between 1917 and 2020 and published on YouTube.

The second instructional video category, peer instructional videos (n = 35), which emerged on YouTube in the 2010s, consists of one primary type, namely vlogs (video logbooks); these are produced and published by learners undertaking cashier training at a workplace and by experienced cashiers. However, no evidence indicates that these vlogs were produced within the context of VET. Furthermore, five vlog sub-types were identified, namely experience vlog, lecture vlog, workday vlog, tutorial vlog and gaming vlog; these are further described in the chapter’s last section. The narrative characteristics of vlogs for service work are summarised in Appendix C.

Professional instructional video types for cashier work

The training video was the oldest video type as well as the most extensive group (n = 44). Training videos were proven since 1917 to mediate the employer’s service script for the cashier’s service encounters. The training video story (i.e. sayings, doings, relatings) was characterised by the instructional method roleplay (cf. Butcher and Ferguson Citation2021) and a combination of persuasion and description to narrate the service script. Furthermore, since 1917, the most common exposition theme has been comparing, meaning that actors demonstrate the ‘do’s and don’ts’ in cashier work. The classic story involved a narrator instructing the learner about what to say and how to speak (knowing-sayings); how to act, behave and appear (knowing-doings); and how to relate to customers, the workplace and the retail company (knowing-relatings) in service encounters. Simultaneously, the actors modelled each step in creating excellent customer service (face-voice). Face-voice refers to actors’ spoken dialogues or displaying the narrator’s face and entire body. Face-voice and talking head (face and upper body) are video communication methods that create an impression of the narrator speaking directly to the viewer, thereby increasing the viewer’s engagement in the video (cf. Köster Citation2018). Notably, the ‘do’s and don’ts’ concerning the cashier’s attitudes (i.e. communication, appearance, behaviour and emotions), values and relations modelled in training video stories from the 20th century were the same as those from the 2010s.

The training video stories transformed in the 1980s, coinciding with computerised cash registers and POS systems becoming commonplace in retail (Basker Citation2016). Previously, training stories mediated the employer’s service script for service encounters involving two activities: transactions and customer service. However, from 1980 onwards, the training stories focused on mediating the script for customer service in the service encounter (cf. Wiley Citation1993). In training videos modelling cashier situations, technology merely served as props. The new focus on the cashier’s interpersonal skills and role in creating customer service coincides with the shift from a provider to a consumer perspective on customer value creation in service theory and practice (Bowen Citation2016). Moreover, the resilient practice traditions forming the internal and external video characteristics socialise learners into a gender stereotype based on domestic ideals (cf. Colley Citation2006; Solbrig Citation2007). This finding indicates that YouTube training videos for cashier work re-produce work patterns and roles associated with the low status of frontline service work.

The tutorial video (n = 25) has existed for the second longest; the sample contained a video about new cashier work methods produced by the University of Iowa in the 1940s. Furthermore, it shares several external narrative characteristics with previous definitions of tutorial videos (e.g.Van der Meij and Van der Meij Citation2013). What separated the YouTube tutorial for cashier work was that it was filmed at the workplace and commonly on the job. The tutorial story mediated ‘knowing-doings’ connected to material-economic arrangements forming the cashier’s service encounters, such as methods for bagging and handling value assets. Of the 23 tutorials produced in the 2010s, 19 concerned the cashier’s role in transactions at the fixed checkout, demonstrating how to operate the mPOS system in the transaction process. However, the transaction process in a service encounter was commonly divided into short videos (2–4 min) focusing on specific activities, such as ‘Closing Toast End of Night’ and ‘Counting change back’.

The instructional method characterising both the tutorial and screencast story was ‘go-to’ instruction combined with demonstration, which involved an instructor presenting step-by-step instructions (voice-over, talking head, face-voice) for how to perform a specific task; simultaneously, the narrator or an actor modelled the methods or routines forming the ‘knowing-doings’ to be learned (cf. Callan and Johnston Citation2020). Furthermore, the instructional and vocational language forming the sayings in tutorial and screencast stories mediating the operation of mPOS systems differed markedly from that in the training and lecture stories. It involved terms and spatial expressions related to computers, software programs and transactions, as illustrated by the following excerpt from a tutorial video filmed on the job:

To start a check transaction, press’ total.’ Then press ‘check,’ then it’s going to prompt you to enter the amount, and in this case, it’s $75, and then press the enter key. You are going to see another prompt that says ‘insert check’ … Sometimes the register can prompt you to ask for a customer’s ID. (Tutorial video, 2017)

The quote above also demonstrates that the verbal instructions in tutorials and screencasts only make sense if experienced alongside with the visual demonstration (knowing-doings). Furthermore, neither the tutorial nor the screencast story described or explained the transaction process nor how to operate and use digital devices and communication technologies in service encounters (cf. Van der Meij and Van der Meij Citation2013). As tutorial stories did not include the cashier’s role and emotional labour in creating customer service in the service encounter, vocational learning on YouTube requires the learner to view both training and tutorial videos for cashier work.

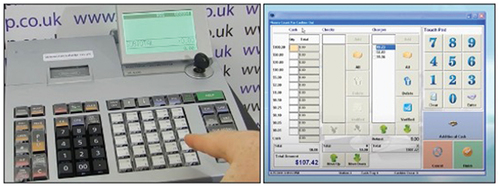

The screencast video (n = 43) showed a group expanding on YouTube in the 2010s, mediating methods for operating a specific mPOS software or application. Screencasts have been defined as a video type filmed by a computer equipped with a camera and screen-capturing software to record both the instructor and the computer screen (see, for example, Köster Citation2018). Most of the screencast stories for cashier work aligned with such a definition. However, several stories in the sample were shown to demonstrate the operation of former POS system generations by filming the register interface (see ). Therefore, in the taxonomy proposed in this article, screencasts for service work refer to a video type that instructs viewers about how to (knowing-doings) operate digital communication technologies by recording the technology interface out of context.

Furthermore, the analysis indicated that in comparison with the previous generation of computerised registers and POS systems, the mPOS systems in the 2010s grew increasingly complex. The cashier’s interactions with the system increased as the mPOS system was intertwined with more systems in the digital service ecosystem. Closing a sale of two items on an iPad demanded interaction with 20–30 windows and prompts on the screen.

The lecture video showed an unexpectantly small group (n = 13) considering it is the most frequent video type in formal education (cf. Köster Citation2018). In contrast to practice-based training, tutorials and screencast videos, the lecture video story can be described as theory-based. It could mediate cultural-discursive (e.g. vocational language, cognitive understandings), material-economic (e.g. methods, appearance) and/or social-political (values, norms, roles, attitudes) arrangements forming the cashier’s knowing-sayings and knowing-relatings in the service encounter with customers. For example, how to calculate change and handle invoices and payment forms. As the label ‘lecture video’ indicates, the story builds on instructional methods commonly used in classroom education, namely, an instructor (face-voice, talking head) or narrator (voice-over, machine-voice) using a classroom setting, whiteboard, laptop or slide show to teach about a topic. Common narrative discourses in the lecture videos were description, argumentation, definition process or combinations thereof, as the quote below from a lecture video for cashier work produced by a retail company illustrates:

In this training, you will learn how to be a successful cashier, someone who provides great service that will keep guests coming back time and time again and when that happens, everyone is a winner … approach every guest wearing a smile and making eye contact … before each shift check daily marketing and promotions coupons and other offers. (Lecture video, 2015)

The example above demonstrates that customer service is central in the lecture stories for cashier work. However, no evidence was discovered for the stories mediating the transaction process or operation of the mPOS system.

Peer instructional videos for cashier work

Vlogs for cashier work expanded as an instructional video group (n = 35) on YouTube in the 2010s, characterised by audio and visual modalities. Moreover, during the study (2018–2021), views increased long after the vlog had been published. In the analysis of the vlogs’ internal narrative characteristics emerged the story’s foundation is the instructional method logbook, and the main purpose of producing a vlog story about work and training is to attract and interact with followers, as illustrated by the following excerpt from a tutorial vlog regarding how to navigate the McDonald’s mPOS interface published in October 2017:

The biggest question I have ever received is how I use the McDonald’s computer system or the POS system, Point of Sales. I believe that’s what it’s called, Point of Sales something/ … /Like I said, if you have any questions, please, please comment them in the section below. I will respond to them as soon as possible. (2022-07-04: 399 970 views; 1 292 comments; most recent comment 2021-06-17)

The excerpt also illustrates another common vlog story characteristic, namely an everyday language for describing the cashier’s work. However, a deeper analysis of practice architectures forming the vlog stories revealed five vlog sub-types.

The experience vlog (n = 8) mediated the feelings, emotions and values (knowing-relatings) the vlogger had experienced as a cashier novice at the workplace or in workplace training. It was narrated (talking head, face-voice) using reflective and conversational discourse as if the vlogger is in a face-to-face encounter with the viewer. The experience stories described feelings of low self-esteem, anxiety, fear and mistakes connected to the checkout service encounter (i.e. interacting with customers and simultaneously operating the mPOS system efficiently and correctly and calculating the change in front of the customer). The stories ended by describing that the negative feelings disappeared when transitioning from the novice to the experienced cashier.

The workday vlog (n = 17) demonstrated the activities, routines, responsibilities, work processes and relationships characterising a workday at a particular workplace (knowing-doings). The workday story shared similarities with travel report TV shows, meaning that it was built upon repeating film sequences with the vlogger describing (talking head) what the viewer could expect to see and learn, followed by a video sequence demonstrating the workplace environment and on-the-job activities. The workday vlogs differed markedly from all other video types in the taxonomy, using a ‘hidden camera’ or ‘bottom-up’ perspective in on-the-job sequences. This perspective reveals that the recording smartphone is held in the palm with the hand kept low, placed in a bag, or as is illustrated in (), positioned below or behind the cash register filming the vlogger’s service encounters. Several workday vlog stories stated that it was necessary to plan how to record secretly, as it was forbidden to use a private smartphone at work.

Figure 4. Hidden camera perspective at the checkout (drawings by the author from screenshots of a workday vlog, 2020).

The tutorial vlog (n = 5) story mediated how to handle items and objects, use equipment and interact with digital technologies in the service practice. Similar to the professional tutorial videos, it was based upon ‘go-to’ instructions and demonstrations. Five tutorial vlogs had titles referring to how to navigate the mPOS system at a particular retail company (knowing-doings). As emerging from the analysis of tutorial vlog stories, the vlogger filmed the mPOS screen with one hand and used the other hand to demonstrate how to navigate the register interface while explaining symbols and abbreviations on the key buttons. However, none of the tutorial vlogs mediated how to operate the mPOS system.

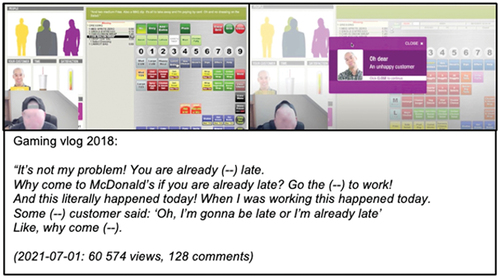

The gaming vlog (n = 7) story mediated the vlogger playing a computer-based checkout simulation or game used in cashier training at the workplace. The viewer is a spectator of virtual service encounters performed and commented on by the vlogger (). It emerged in the analysis of the gaming stories and vlog comments that digital simulations and games focusing on the operation of the mPOS system are used by some employers to train novices for the connected service encounter. The self-regulated training ends when passing the test in the virtual checkout practice after a few hours of ‘gaming’, and the cashier is expected to work the ‘real’ checkout independently.

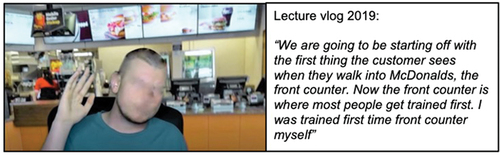

The lecture vlog (n = 2) emerged in the late 2010s, mediating routines, tasks and processes connected to employment, training, and the cashier’s role in service encounters at a particular workplace or retail company (knowing-sayings). The lecture vlog story, produced by the experienced cashier, was built using the same scenography as in the experience vlog but was characterised by a descriptive and conversational discourse. In contrast to the professional lecture video combining three modalities (audio, text, visual), the lecture vlog used audio (talking head) and visual (virtual background) as illustrated in ().

Conclusions and discussion

A significant contribution of this study is its examination of YouTube for vocational learning in service work, targeting the connected service encounter and the proposal of a taxonomy of online instructional video types for VET and workplace learning in service work. With concepts from narrative research and multimodal analysis, TPA was the framework for analysing 160 YouTube instructional videos for cashier work produced between 1917 and 2020. The taxonomy encompasses two main instructional video categories, namely professional and peer, five video types and five sub-types ().

Figure 7. A taxonomy of online instructional video types for VET and workplace learning in service work.

Professional instructional videos comprise four types – training, lecture, tutorial and screencast – which are consistent with video classification models concerning external narrative characteristics (e.g. Carpenter Citation1953; Köster Citation2018; Van der Meij and Van der Meij Citation2013). Peer instructional videos are composed of one video type, vlogs, and five sub-types: experience, lecture, workday, tutorial and gaming vlog. The proposed taxonomy will form the starting point for the discussion of using YouTube instructional videos for service work in VET.

Professional YouTube instructional videos in VET

Research has argued that digital technologies, such as social media, public online video-sharing sites, mobile devices and increasing access to affordable video production tools, will transform the delivery of VET and workplace learning (e.g. Callan and Johnston Citation2020; Ifenthaler Citation2018). Regarding service professions, medicine and healthcare education have designed and utilised training and tutorial videos for skills training for over 50 years. Online videos are considered valuable for teaching procedural skills, supervision, assessment, postoperative debriefing and feedback and promoting reflection (Komal, Chen, and Henning Citation2020; Topps, Helmer, and Ellaway Citation2013). Unlike clinical skills training videos, VET providers produced only 13% of public YouTube instructional videos regarding cashier work. Conversely, retail and tech firms made over half (58%) of the videos in the sample. Furthermore, no evidence was found that vlogs for cashier work were produced within a VET programme framework. Hence, YouTube has not yet become a site for vocational learning in VET for service work.

The finding that retail and tech firms dominate the production of instructional videos for cashier work published on YouTube is arguably advantageous and problematic. One advantage is that training and tutorial videos model on-the-job situations and activities concerning workplaces and firms, thereby preparing learners for work practices. Yet, the narrower focus on firm-specific service scripts and skills constrains learners to acquire broader portable emotional labour skills in retail service (cf. Avis et al. Citation2021). Nonetheless, YouTube training and tutorial videos for service work may serve as a source for VET teachers in critical classroom discussions regarding connections between the digital transformation of frontline service, service cultures, curricular goals, vocational skills and employers’ scripts for emotional labour in service encounters (cf. Ikeler Citation2016; Voorhees, Fombelle, and Bone Citation2020; Benozzo, Colley, and Benozzo Citation2012). More problematic is that no professional instructional video types on YouTube prepared learners for the new roles and emotional labour skills brought by the digital transformation of frontline service (Larivière et al. Citation2017). The division of employee training into transactions (tutorials, screencasts) and customer service (training videos), which emerged in 2010, indicates ignorance amongst employers, VET providers and organisations about the impact of digitalisation on service work intertwining digital and analogue interactions in service encounters (Jandrić et al. Citation2019; Voorhees, Fombelle, and Bone Citation2020).

An essential part of this discussion concerns beliefs about the personal service encounter. What contradictions exist between the ideas, values, norms and roles mediated by employers, tech innovators and VET providers? It was found that training videos produced in the 2010s still modelled the service encounter as a ‘game between persons’ focusing on the cashier’s display of emotional labour (Hochschild Citation2018; Solomon et al. Citation1985). In contrast, screencast videos mediated increasingly complex features of mPOS systems with a minimum of three options for performing transactions requiring employees’ skills development. Nonetheless, vlogs for cashier work discussed how one learns ‘postdigital dialogue’ characterising the connected service encounter (Arkenback-Sundström Citation2022). Interacting with customers while interacting with the mPOS interface and system in the service encounter evoked great fear and anxiety among learners. Combining customer service with transactions revealed an ongoing discussion between viewers and the vlogger and between viewers in the comments. These results suggest that new roles and skills associated with digitalising service encounters in modern retail workplaces must be addressed in VET.

YouTube vlogs in vocational learning

Snelson and Perkins (Citation2009) predicted that individuals would produce learning content on public video-sharing sites, such as YouTube. This work indicates such predictions were accurate, revealing a new form of vocational learning in YouTube communities outside the workplace and VET. There is emerging interest in the pedagogical applications of vlogs published on video-sharing sites that allow viewers to watch, comment and converse with the vlog’s producer and viewers. Recent studies have, for instance investigated vlogs regarding informal language learning (Codreanu and Combe Citation2019) and as a reflective tool in pre-service teachers’ school experience courses (Fidan and Debbağ Citation2018). The literature recognises apprentice logbooks, blogs and vlogs as learning tools that help identify the knowledge and skills required in work, including learning from errors, reflecting on work situations and planning how to contribute to work practices. The most significant feature of vlogs, according to Fidan and Debbağ (Citation2018), is that people form their own experiences and share them as videos.

This study demonstrated that most vloggers produced a series of vlogs mediating aspects of cashier work, employment and workplace training. The vlog sub-types in the proposed taxonomy mirror the roles the professional vlogger transitions between in the YouTube community (Bhatia Citation2018; Bonk Citation2011), namely the amateur expert (experience vlog, gaming vlog), the lecturing teacher (lecture vlog, tutorial vlog) and the peer socialising with viewers (workday vlog). Viewing vlog types in combination, they addressed the process of applying for employment to become an experienced cashier. Furthermore, they provided inside information about the workplace and cashier positions that was otherwise inaccessible to future employees. In the language of TPA, the ‘sayings’ in the vlogs and comments highlighted an ongoing dialogue between the vlogger and viewers and amongst viewers long after the video was published. These YouTube communities served as sites for gaining cashier experience without working as a cashier. For example, the learner developed ‘the cashier experience’ required for employment by repeatedly viewing vlogs concerning cashier work at McDonald’s. The steadily increasing number of views of vlogs about cashier work contrasts with the finding of Callan and Johnston’s (Citation2020), revealing that VET students’ videos were only viewed by fellow students.

The finding of five vlog types indicates that vlogs may support teachers in developing learner-produced videos in VET to address aspects of vocational learning, for instance, creativity and convergent thinking in service work (Fischer and Barabasch Citation2021). Numerous recent studies have noted that video is one digital boundary object that can integrate school- and work-based learning (e.g. Callan and Johnston Citation2020; Cattaneo, Gurtner, and Felder Citation2021; Ifenthaler Citation2018). However, the ‘hidden camera’ perspective in workday vlogs suggests it is necessary to develop ethical guidelines for why, what and how to film on-the-job situations involving interpersonal interactions.

Before this study, little was known about the characteristics of YouTube instructional videos for service work. The study’s strengths include the analysis of internal video narrative characteristics contributing to an enhanced understanding of how various video types facilitate learning concerning frontline employees’ connected service encounters. The use of YouTube for vocational learning is highly compatible with the objectives of lifelong learning (Jaldemark et al. Citation2021). However, the contemporary VET curriculum, workplaces and learning content on YouTube do not yet prepare individuals for the connected work practice in which the digital and analogue are intertwined (cf. Avis et al. Citation2021; Jandrić et al. Citation2018). Regarding the retail work associated with routinised low-skilled work and entry-level occupations (e.g. Brockmann Citation2013; Hastwell, Strauss, and Kell Citation2013), the longstanding focus on customer service and emotional labour skills in employee training identified in this study emerge as a constraint to the concept of lifelong learning in service work (cf. Colley Citation2012).

Vocational researchers can play an active role in discussing the use of social media and online instructional videos in VET and workplace learning. Moreover, researchers can connect employers, employees and teachers in studies on how to design and use online instructional videos for service work involving interactions with human and digital co-workers (e.g. artificial intelligence). Finally, the taxonomy of online instructional video types for VET and workplace learning in service work proposed here is based on analyses of public YouTube instructional videos respecting cashier work. Future research must investigate video types of other service occupations. Concerning the study’s analytical framework, a potential limitation is the theorisation of the video narrative as a practice.

Appendix_C._Peer_instructional_video_types_for_service_work.docx

Download MS Word (16.1 KB)Appendix_B._Professional_online_instrcutional_videos_for_service_work.docx

Download MS Word (17.9 KB)Appendix_A._Analysis_templates.docx

Download MS Word (254.7 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820.2023.2180423

References

- Arkenback, Charlotte 2022 . Workplace Learning in Interactive Service Work: Coming to Practise Differently in the Connected Service Encounter. University of Gothenburg. http://hdl.handle.net/2077/70217 .

- Arkenback-Sundström, Charlotte. 2022. “A Postdigital Perspective on Service Work: Salespeople’s Service Encounters in the Connected Store.” Postdigital Science and Education 4 (2): 422–446. doi:10.1007/s42438-021-00280-2.

- Avis, James, Liz Atkins, Bill Esmond, and Simon McGrath. 2021. “Re-Conceptualising VET: Responses to Covid-19.” Journal of Vocational Education & Training 73 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1080/13636820.2020.1861068.

- Basker, Emek. 2016. “The Evolution of Technology in the Retail Sector.“ In Handbook on the Economics of Retailing and Distribution, edited by Basker Emek, 38–53. UK: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

- Bell, Daniel. 1973. The Coming of Post-Industrial Society: A Venture in Social Forecasting. New York: Basic books.

- Benozzo, Angelo, Helen Colley, and A. Benozzo. 2012. “Emotion and Learning in the Workplace: Critical Perspectives.” Journal of Workplace Learning 24 (5): 304–316. doi:10.1108/13665621211239903.

- Bezemer, Jeff, and Carey Jewitt. 2010. “Multimodal Analysis: Key Issues.” In Research Methods in Linguistics, edited by Lia Litosseliti, 180–197. London: Continuum.

- Bhatia, Aditi. 2018. “Interdiscursive Performance in Digital Professions: The Case of YouTube Tutorials.” Journal of Pragmatics 124: 106–120. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2017.11.001.

- Biel, J-I, and Daniel Gatica-Perez. 2011. “VlogSense: Conversational Behavior and Social Attention in YouTube.” ACM Transactions on Multimedia Computing Communications and Applications 7S (1): 1–21. doi:10.1145/2037676.2037690.

- Billett, Stephen 2014. Mimetic Learning at Work: Learning in the Circumstances of Practice. Springer Cham. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-09277-5.

- Boldrini, Elena, and Cattaneo Alberto. 2013. Written Identification of Errors to Learn Professional Procedures in VET Journal of Vocational Education & Training 65 4 doi:10.1080/13636820.2013.853684

- Bonk, Curtis J. 2011. “YouTube Anchors and Enders: The Use of Shared Online Video Content as a Macrocontext for Learning.” Asia-Pacific Collaborative Education Journal 7 (1): 13–24.

- Bowen D E. 2016. “The changing role of employees in service theory and practice: An interdisciplinary view.“ Human Resource Management Review 26(1) :4–13. doi:10.1016/j.hrmr.2015.09.002.

- Brockmann, Michaela. 2013. “Learning Cultures in Retail: Apprenticeship, Identity and Emotional Work in England and Germany.” Journal of Education and Work 26 (4): 357–375. doi:10.1080/13639080.2012.661847.

- Butcher, Luke, and Graham Ferguson. 2021. “Harnessing ‘Play’ (Beyond Games) to Enhance Self-Directed Learning in VET.” Journal of Vocational Education & Training 1–20. doi:10.1080/13636820.2021.1989621.

- Callan, V J, and M A. Johnston. 2020. “Influences Upon Social Media Adoption and Changes to Training Delivery in Vocational Education Institutions.” Journal of Vocational Education & Training 74 (4): 1–26. doi:10.1080/13636820.2020.1821754.

- Callan, V J, M A. Johnston, and A L. Poulsen. 2015. “How Organisations are Using Blended E-Learning to Deliver More Flexible Approaches to Trade Training.” Journal of Vocational Education & Training 67 (3): 294–309. doi:10.1080/13636820.2015.1050445.

- Carpenter, C.R. 1953. “A Theoretical Orientation for Instructional Film Research.” Audiovisual Communication Review 1 (1): 38–52. doi:10.1007/BF02713169.

- Cattaneo Alberto AP, and Elena Boldrini. 2017. Learning from errors in dual vocational education: video-enhanced instructional strategies. JWL 29 (5) :357–373. doi:10.1108/JWL-01-2017-0006.

- Cattaneo, Alberto, Alessia Evi-Colombo, and Maria Ruberto. 2019. Video pedagogy for vocational education: An overview of video-based teaching and learning. European Training Foundation. Acessed 5 Mars 2021. https://www.etf.europa.eu/en/publications-and-resources/publications/video-pedagogy-vocational-education-overview-video-based.

- Cattaneo, Alberto, Jean-Luc Gurtner, and Joris Felder. 2021. “Digital Tools as Boundary Objects to Support Connectivity in Dual Vocational Education: Towards a Definition of Design Principles.” In Developing Connectivity Between Education and Work: Principles and Practices, edited by Eva Kyndt, Simon Beausaert, and Ilya Zitter, 137–157. London: Routledge.

- Chorianopoulos, Konstantinos. 2018. “A Taxonomy of Asynchronous Instructional Video Styles.“ International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning 19 (1). doi:10.19173/irrodl.v19i1.2920.

- Codreanu, Tatiana, and Christelle Combe. 2019. “Vlogs, Video Publishing, and Informal Language Learning.“ In The Handbook of Informal Language Learning, edited by Dressman Mark, and Sadler Randall William, 153–168. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi:10.1002/9781119472384.ch10.

- Colley, Helen. 2006. “Learning to Labour with Feeling: Class, Gender and Emotion in Childcare Education and Training.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 7 (1): 15–29. doi:10.2304/ciec.2006.7.1.15.

- Colley, Helen. 2012. “Not Learning in the Workplace: Austerity and the Shattering of in Public Service Work.” Journal of Workplace Learning 24 (5): 317–337. doi:10.1108/13665621211239868.

- Dobricki, Martin, Alessia Evi-Colombo, and Alberto Cattaneo. 2020. “Situating Vocational Learning and Teaching Using Digital Technologies - a Mapping Review of Current Research Literature.” International Journal for Research in Vocational Education and Training 7 (3): 344–360. doi:10.13152/IJRVET.7.3.5.

- Fidan, Mustafa, and Murat Debbağ. 2018. “The Usage of Video Blog (Vlog) in the “School Experience” Course: The Opinions of the Pre-Service Teachers.” Journal of Education and Future 13:161–177.

- Fischer, Silke, and Antje Barabasch. 2021. “Facets of Creative Potential in Selected Occupational Fields.” Journal of Vocational Education & Training 1–19. doi:10.1080/13636820.2021.2007984.

- Fischer, Christoph, Michael Goller, Lorraine Brinkmann, and Christian Harteis. 2018. “Digitalisation of Work: Between Affordances and Constraints for Learning at Work.“ In Digital Workplace Learning, edited by Ifenthaler Dirk, 227–249. Springer Cham. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-46215-8_13.

- Hastwell, Kim, Pat Strauss, and Catherine Kell. 2013. “‘But Pasta is Pasta, It is All the same’: The Language, Literacy and Numeracy Challenges of Supermarket Work.” Journal of Education and Work 26 (1): 77–98. doi:10.1080/13639080.2011.629181.

- Hediger, Vinzenz, and Patrick Vonderau. 2009. Films That Work: Industrial Film and the Productivity of Media. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Hochschild, Arlie Russell. 1983. The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. Berkeley: Univ. of California Press.

- Ifenthaler, Dirk. 2018. Digital Workplace Learning: Bridging Formal and Informal Learning with Digital Technologies. Springer Cham. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-46215-8.

- Ikeler, Peter. 2016. “Deskilling Emotional Labour: Evidence from Department Store Retail.” Work, Employment and Society 30 (6): 966–983. doi:10.1177/0950017015609031.

- Jaldemark, Jimmy, Marcia Håkansson Lindqvist, Peter Mozelius, and T. Ryberg. 2021. “Editorial Introduction: Lifelong Learning in the Digital Era.” British Journal of Educational Technology 52 (4): 1576–1579. doi:10.1111/bjet.13128.

- Jandrić, Petar, Jeremy Knox, Tina Besley, Thomas Ryberg, Juha Suoranta, and Sarah Hayes. 2018. “Postdigital Science and Education.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 50 (10): 893–899. doi:10.1080/00131857.2018.1454000.

- Jandrić, Petar, Thomas Ryberg, Jeremy Knox, Nataša Lacković, Sarah Hayes, Juha Suoranta, Mark Smith, et al. 2019. “Postdigital Dialogue.” Postdigital Science and Education 1 (1): 163–189. doi:10.1007/s42438-018-0011-x.

- Julian, A. K., Z. S. Farley, A. Beach, and F. M. Perna. 2020. “Do-It-Yourself Sunscreen Tutorials on YouTube.” Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention 29 (3): 693. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-20-0059.

- Kemmis, Stephen. 2019. A Practice Sensibility: An Invitation to the Theory of Practice Architectures. Springer Singapore. doi:10.1007/978-981-32-9539-1.

- Kemmis, Stephen, Jane Wilkinson, Christine Edwards-Groves, Ian Hardy, Peter Grootenboer, and Laurette Bristol. 2014. Changing Education: Changing Practices. Springer Singapore. doi:10.1007/978-981-4560-47-4.

- Komal, Srinivasa, Yan Chen, and Marcus A. Henning. 2020. “The Role of Online Videos in Teaching Procedural Skills to Post-Graduate Medical Learners: A Systematic Narrative Review.” Medical Teacher 42 (6): 689–697. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2020.1733507.

- Köster, Jonas. 2018. Video in the Age of Digital Learning. Cham: Springer International Publishing doi:10.1007/978-3-319-93937-7.

- Larivière, Bart, David Bowen, Tor W. Andreassen, Werner Kunz, Nancy J. Sirianni, Chris Voss, Nancy V. Wünderlich, and Arne De Keyser. 2017. ““Service Encounter 2.0”: An Investigation into the Roles of Technology, Employees and Customers.” Journal of Business Research 79: 238–246. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.03.008.

- Legewie, N., and A. Nassauer. 2018. “YouTube, Google, Facebook: 21st Century Online Video Research and Research Ethics.” Forum: Qualitative Social Research 19 (3): 1–23. doi:10.17169/fqs-19.3.3130.

- OECD. 2020. “COVID-19 and the Retail Sector: Impact and Policy Responses.” Accessed 5 Mars 2022. https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/covid-19-and-the-retail-sector-impact-and-policy-responses-371d7599/.

- Pieter, Wouters, Huib K. Tabbers, and Fred Paas. 2007. “Interactivity in Video-Based Models.” Educational Psychology Review 19 (3): 327–342. doi:10.1007/s10648-007-9045-4.

- Reiser, R A. 2001. “A History of Instructional Design and Technology: Part I: A History of Instructional Media.” Educational Technology Research and Development 49 (1): 53–64. doi:10.1007/BF02504506.

- Rust, R T., and M-H. Huang. 2014. “The Service Revolution and the Transformation of Marketing Science.” Marketing Science 33 (2): 206. doi:10.1287/mksc.2013.0836.

- Snelson, C., and R A. Perkins. 2009. “From Silent Film to YouTube™: Tracing the Historical Roots of Motion Picture Technologies in Education.” Journal of Visual Literacy 28 (1): 1–27. doi:10.1080/23796529.2009.11674657.

- Solbrig, Heide. 2007. “Henry Strauss and the Human Relations Film: Social Science Media and Interactivity in the Workplace.” The Moving Image 7 (1): 27–50. doi:10.1353/mov.2007.0030.

- Solomon, M R., Carol Surprenant, J A. Czepiel, and E G. Gutman. 1985. “A Role Theory Perspective on Dyadic Interactions: The Service Encounter.” Journal of Marketing 49 (1): 99–111. doi:10.2307/1251180.

- Squire, Corinne, Mark Davis, Cigdem Esin, Molly Andrews, Barbara Harrison, Lars-Christer Hydén, and Margareta Hydén. 2014. What is Narrative Research?. London, New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Surprenant, Carol F., and Michael R. Solomon. 1987. “Predictability and Personalization in the Service Encounter.” Journal of Marketing 51 (2): 86–96. doi:10.1177/002224298705100207.

- Topps, David, Joyce Helmer, and Rachel Ellaway. 2013. “YouTube as a Platform for Publishing Clinical Skills Training Videos.” Academic Medicine 88 (2): 192–197. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31827c5352.

- Van der Meij, H., and J. Van der Meij. 2013. “Eight Guidelines for the Design of Instructional Videos for Software Training.” Technical Communication 60 (3): 205–228.

- Voorhees, C M., P W. Fombelle, and S A. Bone. 2020. “Don’t Forget About the Frontline Employee During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Preliminary Insights and a Research Agenda on Market Shocks.” Journal of Service Research: JSR 23 (4): 396–400. doi:10.1177/2F1094670520944606.

- Webster, Juliet. 2004. “Digitising Inequality: The Cul-de-Sac of Women’s Work in European Services.” New Technology, Work and Employment 19 (3): 160–176. doi:10.1111/j.1468-005X.2004.00135.x.

- Wiatr, Elizabeth. 2002. “Between Word, Image, and the Machine: Visual Education and Films of Industrial Process.” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 22 (3): 333–351. doi:10.1080/01439680220148741.

- Wiley, Carolyn. 1993. “Training for the ’90s: How Leading Companies Focus on Quality Improvement, Technological Change, and Customer Service.” Employment Relations Today 20 (1): 79–96. doi:10.1002/ert.3910200111.

Appendix A.

Analysis templates

Appendix B.

Professional online instructional video types for service work

Appendix C.

Peer instructional video types for cashier work, vlogs