ABSTRACT

In this paper, we investigate the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on vocational education and training in Germany. We exploit rich establishment-level survey data to estimate the causal effects of the pandemic by applying difference-in-differences estimation, contrasting trends in outcomes between establishments that suffered to varying degrees from adverse economic impacts after the first lockdown. We find that, due to the pandemic, establishments have not become more likely to leave the training market but hired less new trainees and retained less of their recent graduates in the first two years of the crisis, on average. We also compare these effects with the effects of the Great Recession on training and find that both are remarkably similar. Our findings foster concerns that the pandemic increases future skills shortage in the labour market and dampens young peoples’ career prospects.

Introduction

In Germany, as well as in other countries, the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has raised concerns that vocational education and training (VET) is being neglected during the crisis. Hubertus Heil, Germany’s Minister of Labour and Social Affairs, expressed these concerns by stating, ‘We cannot permit ourselves a Corona cohort’ (original: ‘Wir können uns keinen Corona-Jahrgang erlauben’; see Deutschlandfunk Citation2020). This statement reflects fears about skills shortage becoming more severe in the future and long-term career disadvantages arising for the ‘Corona generation’.

Neglecting VET during a crisis is potentially problematic for both young people and establishments alike. For young people, acquiring productive skills and a smooth transition from education into work are important steps for their career development. Negative long-term effects of youth unemployment on future labour market participation, employment status, earnings and work quality, so-called ‘scarring effects’, are often visible far into the working career, particularly for less skilled youth (cf. Gregg Citation2001; Manzoni and Mooi-Reci Citation2011; Nilsen and Holm Reiso Citation2014; Riphahn and Zibrowius Citation2016; Luijkx and Wolbers Citation2009; Schmillen and Umkehrer Citation2018; Stuth and Jahn Citation2020). Additionally, although VET systems have been described to generally smooth the school-to-work transition (cf. Achatz, Jahn, and Schels Citation2022; Brzinsky-Fay and Solga Citation2016), the literature frequently reports persistent career losses for young people being unfortunate to enter the labour market during a recession. For German apprenticeship graduates into the 1992–1996 recession, for instance, Umkehrer (Citation2019) finds substantial losses in real average earnings over the first 14 years after graduation. Oreopoulos, von Wachter, and Heisz (Citation2012) or Altonji, Kahn, and Speer (Citation2016) report similar findings for Canada or the USA, respectively. Strikingly, again these losses appear to be particularly pronounced for less skilled youth (see von Wachter Citation2020, for a summary of this literature). Not being able to start or complete VET during the pandemic might arguably have even more severe negative career effects, especially for disadvantaged young workers (Bell and Blanchflower Citation2011).

For establishments, long-term trends, like demographic (Bellmann Citation2022) and skill-biased technological change (Autor, Levy, and Murnane Citation2003), are likely to further increase the demand for skilled workers. VET is seen as one important pillar for establishments to cover this demand (Stevens Citation1994). Not investing in the training of young people during the crisis will probably increase skills shortage afterwards once the economy recovers.

In this study, we analyse how the COVID-19 pandemic affected establishments’ VET activities in the first two years of the crisis in Germany. The quasi-experimental setting of the pandemic, in combination with rich establishment-level survey data, enables us to identify causal effects primarily on the demand side (i.e. the training establishments) of the training market. Although the establishment data allow us to draw some conclusions about reactions of the supply side (i.e. the (potential) trainees), too, we are not aware of any sufficiently rich data on young workers that is currently available to analyse the supply side explicitly and therefore have to leave a more detailed study to future research.

From a theoretical point of view, the effects of an economic downturn on the amount of training are ex-ante ambiguous; see the discussion in Muehlemann, Pfeifer, and Wittek (Citation2020) and the references therein. On the one hand, declining productivity may lead to a decline in the demand for labour and therefore to a reduction in the number of trainees, especially in some occupations and industries (Eichhorst, Marx, and Rinne Citation2021), for instance. On the other hand, the less costly labour of trainees may be increasingly used to substitute for the more costly labour of regular employees and therefore the number of trainees may not drop or even increase during a downturn (Wolter and Ryan Citation2011). A further explanation for why training could increase during an economic crisis is reduced opportunity costs for instructors or limited outside options for trainees. Moreover, restrictions on the supply-side are possible, too. For instance, poor labour market entry conditions could discourage potential trainees from applying for a training position and make them more likely to pursue general (further) schooling or school-based vocational training instead (Clark Citation2011; Raffe and Willms Citation1989; Hillmert, Hartung, and Weßling Citation2017; Micklewright, Pearson, and Smith Citation1990). Ultimately, it remains an empirical question how vocational provisions react to the COVID-19 pandemic.

For our analysis of the causal effects of the pandemic on training, we draw on the IAB Establishment Panel, a large, representative and annually conducted survey of establishments in Germany. The 2020 survey was taken right after the first lockdown and contains information on the type and intensity of adverse economic impacts of the pandemic on the establishments. Declining demand is by far the most frequently reported type of impact. Closures ordered by authorities and personnel shortages, in turn, are less frequent. Moreover, the degree to which establishments were affected varies substantially. While 56% of the 7,516 training establishments participating in the 2020 survey responded that they experienced no, very weak, or weak adverse economic impacts due to the pandemic, the remaining 44% responded that they experienced medium strong, strong, or very strong adverse economic impacts.

We exploit this variation in economic affectedness after the first lockdown to estimate the effects of the pandemic on different training outcomes by applying a classical difference-in-differences (DiD) estimation strategy. Specifically, we contrast changes in outcomes before versus after the start of the pandemic between establishments that suffered to varying degrees from its adverse economic impacts. This is, we utilise less affected establishments to assess how training would have developed without the pandemic and explore how more affected establishments deviate from this counterfactual trend. Our strategy thus identifies causal effects under the assumption that outcomes in more affected establishments would have developed at the same rate in the absence of the pandemic as in less affected establishments. We carefully explore this assumption and provide evidence that it is very likely to hold in our setting.

Overall, we do not find establishments to cease training completely due to the pandemic in the first two years of the crisis, but there is some evidence that particularly small establishments have become more likely to leave the training market in the second year. Additionally, we find a negative effect of the pandemic on the hiring of new trainees and significant and sizeable reductions in the likelihood that current graduates from VET remained employed by their training establishment after graduation.

Throughout the paper, we provide evidence that our results are not driven by pre-trends, selectivity, spill-over effects, and policy interventions coinciding with the pandemic. Furthermore, we analyse effect-heterogeneity by location, industry sector or establishment size, discuss that restrictions on the side of the establishments are probably the main driver of our results in the short run while supply-side factors gain in importance in the medium run, and compare our estimates with those of the effects of the Great Recession on VET, documenting remarkable similarities between the two crises.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. In Section ‘Background and Data’, we provide background information and outline our data. In Section ‘Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on VET’, we describe the method and present results, including robustness checks. In Section ‘Discussion’, we discuss the results and compare them with findings from the Great Recession before we conclude in the last section.

Background and data

Germany’s VET system

The dual system of VET in Germany combines occupation-specific on-the-job training in an establishment with theoretical education in public vocational part-time schools (cf. Hippach-Schneider, Krause, and Woll Citation2007, for a short description). On the training market, establishments post vacancies, young applicants apply for a position and, ultimately, establishments and applicants conclude contracts for conducting the training. During the practical work, the trainees carry out productive tasks in their training establishment for which they receive a remuneration.

The VET system is strongly regulated by the Vocational Training Act and the Vocational Training Curricula for a given occupation. These define the conditions under which an establishment is eligible to train, the duration of training, the remuneration, and minimum standards for training. Although VET has a clear focus on a specific occupation, the skills acquired are transferable to a certain degree (Harhoff and Kane Citation1997; Fitzenberger, Licklederer, and Zwiener Citation2015; Winkelmann Citation1996). In Germany, about 300 different training occupations exist and training usually takes two to three years, depending on the occupation trained and individual performance. Training years start in August or September in the majority of sectors and professions. Access to training does usually not require a specific school-leaving certificate by law, although restrictions might apply for certain tracks or occupations (Protsch and Solga Citation2015). The dual system of VET plays an important role for skill formation in Germany and it is often seen as a successful way to tackle youth unemployment (Brzinsky-Fay and Solga Citation2016), especially in economic crises (Muehlemann, Pfeifer, and Wittek Citation2020; Eichhorst et al. Citation2015).

Establishments’ training motives

The literature identifies two main reasons why establishments provide VET: the production-orientated and the investment-orientated motive (Soskice Citation1994). Establishments with a production-orientated training strategy consider trainees as a source of cheap labour. The productive contribution made by trainees compared to the wages they receive is the main driver for these establishments to employ trainees (Lindley Citation1975; Wolter and Ryan Citation2011).

In establishments with an investment-orientated training strategy, in turn, the benefits of trainees during the training period itself are less important as they see training as a longer-term investment in their future workforce (Stevens Citation1994). These establishments are willing to bear the net costs during the initial training period because they expect their investment to amortise when taking on their trainees after graduation and under the assumption that it is less expensive to train and to retain trainees than to recruit and onboard skilled workers from the external labour market (cf. Blatter, Muehlemann, and Schenker Citation2012; Hillmert, Hartung, and Weßling Citation2017; Blatter et al. Citation2016; Mohrenweiser and Backes‐Gellner Citation2010; Muehlemann and Wolter Citation2021; Muehlemann, Pfeifer, and Wittek Citation2020).

There is evidence that the investment-orientated motive dominates the production-orientated motive for providing VET in the German system (Mohrenweiser and Backes‐Gellner Citation2010; Muehlemann et al. Citation2010; Schönfeld et al. Citation2020). If many establishments base their decision to train on longer-term considerations, this could contribute to a certain robustness of the training market with respect to temporary crises (cf. Hillmert, Hartung, and Weßling Citation2017), also in international comparison (cf. Scandurra, Cefalo, and Kazepov Citation2021).

Relevant literature

Our study contributes to the literature on VET in at least three ways. First, we add to the broad literature analysing employer-provided VET more generally; see, among others, Winkelmann (Citation1996) on the specificity of skills conveyed during training, Harhoff and Kane (Citation1997) for a comparison of the German system with the one in the USA (documenting that graduates from apprenticeship training in Germany occupy a similar position in the wage distribution as high school graduates in the USA), Acemoglu and Pischke (Citation1998) and Mohrenweiser and Backes‐Gellner (Citation2010) on employers’ training motives, Fersterer, Pischke, and Winter-Ebmer (Citation2008) on the returns to training, Dustmann and Schönberg (Citation2009) on the role of unions, von Wachter and Bender (Citation2006) as well as Fitzenberger, Licklederer, and Zwiener (Citation2015), Brzinsky-Fay and Solga (Citation2016), Dummert (Citation2021) and Achatz, Jahn, and Schels (Citation2022) on worker mobility and training-to-work transitions after graduation, and Muehlemann et al. (Citation2010) on investment decisions.

Second, we complement the literature analysing the cyclicality of VET. Relevant studies for Germany include Dietrich and Gerner (Citation2007), Muehlemann, Wolter, and Wüest (Citation2009), Baldi, Brüggemann-Borck, and Schlaak (Citation2014) as well as Bellmann, Gerner, and Leber (Citation2014). The two latter studies focus on VET during the Great Recession. Brunello (Citation2009) provides a review of results from earlier studies and Muehlemann, Pfeifer, and Wittek (Citation2020) summarise that the majority of empirical studies document that VET reacts moderately pro-cyclical.

Third, we are among the first to provide evidence on the causal effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on VET in Germany. To the best of our knowledge, until now only studies exist that forecast the effects of the pandemic using aggregated data. Muehlemann, Pfeifer, and Wittek (Citation2020) as well as Maier (Citation2020) utilise data on expectations about business cycle development or forecasts of GDP growth, respectively, to predict the likely reaction of the German apprenticeship market to the pandemic. In line with our findings, both studies predict a drop in the number of new training contracts in 2020 relative to 2019, by about 6%, depending on model assumptions. Ultimately, we are the first to provide causal estimates of actual developments in the first two years of the pandemic using establishment-level micro data for Germany.

Data, sample selection, and variables

The IAB Establishment Panel, a key database for the analyses of labour demand in Germany (cf. Ellguth, Kohaut, and Möller Citation2014), serves as our main data set for conducting the analysis of the causal effects of the pandemic on training. It is a multi-topic survey of nearly 16,000 establishmentsFootnote1 per year that has been repeated annually since 1993 for western Germany and since 1996 for eastern Germany. The sample is stratified by federal state, economic sector and establishment size. It is randomly drawn from the Establishment File of the Federal Employment Agency (BA), which contains the universe of German establishments with at least one employee subject to social insurance contributions. In addition to annually repeated core questions, such as on VET, the survey also includes changing focus topics. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic was one of these focus topics in the 2020 survey.

We begin our analysis in 2013 and therefore after the end of the Great Recession. The 2020 survey is crucial for our analysis because we use it to define treatment status (see next section). Its interviews were conducted from July to Mid-November, i.e. after the first lockdown in Germany, which ended in May, and before the second (partial) lockdown, which began in November. The survey responses in 2020 thus capture the state after the first lockdown.

For our analysis, we select all ‘training establishments’ from the IAB Establishment Panel. We define an establishment as training establishment if it either trains at least one trainee on June 30 of the current year (irrespective of how long the training has lasted already), trained at least one trainee on June 30 of the previous year,Footnote2 has concluded at least one new training contract in the current year, has offered at least one training position in the current year but could not fill it, or has graduates having completed training in the current year. We therefore sample establishments also if they are not themselves actively training right now but are generally willing to train, making sure to capture possible effects also at the extensive margin and thus to avoid sample selection issues.

Ultimately, we select 7,516 training establishments out of all 16,604 establishments of the 2020 survey into our estimation sample. For these training establishments, we merge observations from the 2013 to 2019 surveys, to estimate outcomes in pre-treatment years, and observations from the 2021 survey, to estimate effects in the second year of the crisis (see Section ‘Method’).

We analyse three outcome variables: i) the fraction of successful graduates in the current year who continue their careers in the training establishment (or in another establishment of the same company, if the training establishment is part of a multi-establishment company) among all successful graduates of that year, ii) an indicator variable for whether a training establishment trains at least one trainee in the current year, and, iii) an indicator variable for whether a training establishment has concluded new training contracts for the next training year. We refer to these outcomes as the take-over rate, the likelihood to train this year, and the likelihood to train new trainees, respectively. In the benchmark specification, we control for an establishment’s location, size (measured before the pandemic to avoid endogeneity with respect to potential effects of the pandemic), industry, and survey participation; see Section ‘Method’ for details. We describe our main treatment variable, the economic affectedness by the pandemic, in the next section.

In addition to the IAB Establishment Panel, we can also draw on another survey conducted by the IAB, the so-called ‘Establishments in the Covid-19-Crisis’ (BeCovid, hereafter) survey; cf. Bellmann et al. (Citation2022). BeCovid is a high-frequency establishment survey that was conducted in 24 waves between August 2020 and June 2022 to map the consequences of the COVID-19 crisis. It provides us with unique additional insights into how the German training market has developed during and in the aftermath of the pandemic.

Economic affectedness by the COVID-19 pandemic

The 2020 survey of the IAB Establishment Panel starts with the following questions: ‘Did or does the COVID-19 pandemic have adverse economic impacts on your establishment? If so: Which of the following negative impacts did or does the Corona pandemic have on your establishment (multiple answers possible)? To what extent did or does the COVID-19 pandemic negatively affect your establishment?’. We use this information to measure the economic affectedness of establishments after the first lockdown, which will serve as treatment variable in our DiD analysis.

The responses show that the pandemic affected establishments in Germany to quite varying degrees. Almost 39% of training establishments reported that they did not suffer from adverse economic impacts of the pandemic after the first lockdown in 2020. Five per cent reported only very weak and about twelve per cent weak impacts. In contrast, 23% faced medium strong, 13% strong and eight per cent very strong adverse economic impacts of the pandemic.

Furthermore, decreasing demand is by far the most frequent type of adverse economic impact of the pandemic (reported by 81% of negatively affected training establishments), followed by difficulties with supply chains (50%), personnel shortages (39%), liquidity shortages (38%), and establishment closure (30%).

Although this measure of affectedness relies on subjective assessments of the establishments, it captures the economic shock of the pandemic well. In 76% of training establishments that reported medium strong, strong, or very strong adverse impacts, sales declined between 2019 and 2020, while they declined for only 18% of establishments reporting no, very weak, or weak impacts. In the first group, sales declined by on average 24% while they increased by one per cent in the second group.Footnote3

Finally, having established that large fractions of establishments were either substantially affected in economic terms by the pandemic in 2020 or not at all, we now turn to characterising which establishments were more likely to be affected than others in a regression framework. We do this by estimating a linear probability model of experiencing medium strong, strong, or very strong adverse economic impacts of the pandemic. As explanatory variables, we include the location of the establishment (East/West), the establishment size in 2019 (three categories), and the industry (nine categories). We present the ordinary least squares estimates in .

Table 1. Which establishments are affected?

Strikingly, the location and the size of the establishment play no or only a minor role for the affectedness by the COVID-19 pandemic once the industry is controlled for. One explanation for this pattern is that the pandemic constitutes an unanticipated random shock that hits establishments of different size classes and at different locations within industry sectors in a quite similar way. However, contact limitations or supply bottlenecks during the lockdown affected industry sectors in quite different ways. The results in support this hypothesis by showing clear differences in affectedness across industries. For instance, establishments in the hospitality and transport and storage sectors were most likely to be moderately strongly to very strongly negatively affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, conditional on location and size. Training establishments in the hospitality sector were 73 pp and training establishments in the transport and storage sector were 43 pp more likely to be negatively affected than training establishments in the agriculture, forestry and mining sectors (the reference category), conditional on location and size. In contrast, agriculture, forestry and mining as well as construction were the least negatively affected industries, with no statistically significant differences in affectedness between them.

Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on VET

Preliminary descriptive evidence

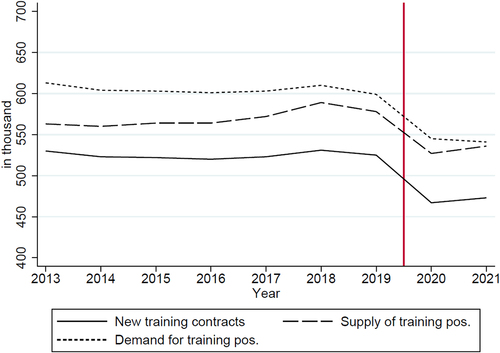

Descriptive evidence already suggests a negative impact of the pandemic on VET. According to official statistics of the BIBB (Citation2021), the number of newly concluded training contracts, the number of training positions supplied by establishments as well as the number of trainees searching for a position declined suddenly and significantly between 2019 and 2020. Compared to 2019, the number of new training contracts fell by 57,600, or 11%, to 467,500 contracts, which is a new low in Germany ().Footnote4 The largest decline of 13.9% was registered in industry and commerce (Oeynhausen et al. Citation2020). The supply of training positions declined by 8.8% between 2019 and 2020, from 578,200 to 527,400 positions in September, and the number of training position demanded decreased by 8.9% during the same period, from 598,600 to 545,400 positions. Compared to 2020, in 2021 the number of new training contracts and the supply of training positions increased somewhat by 1.2 resp. 1.7%, whereas the demand for training positions continued to decline slightly by 0.9% (BIBB Citation2021).

Figure 1. Number of newly concluded training contracts, supplied training positions and demanded training positions, 2013 to 2021, September.

Furthermore, the 2020 survey of the IAB Establishment Panel provides information on the personnel policy measures that establishments intended to implement in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in the area of VET. Nine per cent of the training establishments that suffered from medium to very strong adverse economic impacts of the pandemic stated that they intended to retain less of their graduates. Among the other training establishments, this share was only 1.5%. In addition, 19% of the affected training establishments intended to forego the planned filling of vacant training positions. By contrast, only four per cent of the other training establishments intended to do so.

However, solely relying on time-series comparison and intended personnel policy measures reported by establishments might yield a biased picture of the causal effects of the pandemic on vocational training. For instance, the BIBB assumes that at least a part of the decline in the number of newly concluded training contracts between 2019 and 2020 has taken place independent of the pandemic (Oeynhausen et al. Citation2020). Next, we describe our approach to identify causal effects of the pandemic.

Method

Our estimation strategy to identify the causal effects of the COVID-19 pandemic is to compare differences in training outcomes between establishments that are more negatively affected (the ‘treated’) and less negatively affected (the ‘controls’) by the pandemic after the first lockdown in 2020. We then follow these differences over time and investigate if treated deviate from control establishments after but not before the start of the pandemic. If training outcomes have followed the same trend in all establishments before the start of the pandemic and then suddenly diverge for the treated establishments afterwards, we argue that this is due to a causal effect of the pandemic.

We implement this DiD strategy by running ordinary least squares regressions separately for each outcome on three sets of indicator variables for i) the calendar year (2013–2021), ii) establishments that are negatively affected by the pandemic after the first lockdown in 2020, and iii) interaction terms between these indicators. We leave out 2019 because it will serve as reference year, such that all differences between treated and control establishments will be taken relative to the difference in 2019. Additionally, we apply the trend-adjustment procedure of Dustmann et al. (Citation2022) to account for possible pre-trends before the pandemic, control for observable characteristics, like region, size, and industry, and cluster standard errors at the industry-year level. This DiD methodology is described in detail in Online Appendix A.

We are most interested in the coefficients on the interaction terms between the years and treatment status. Estimates of these coefficients provide a measure of how the difference in a given outcome between treated and control establishments has changed relatively to 2019. If the identifying assumption – that treated and control establishments would have developed at the same rate in the absence of the pandemic – holds, these DiD estimates should be close to zero in the years before 2019 (we refer to this as ‘placebo’ tests) and estimates in the years 2020 and 2021 would capture a causal effect of the pandemic. In Section ‘Results’, we provide evidence that the assumption holds and, in Section ‘Robustness Checks’, we present results of a number of additional checks, further supporting its validity.

Results

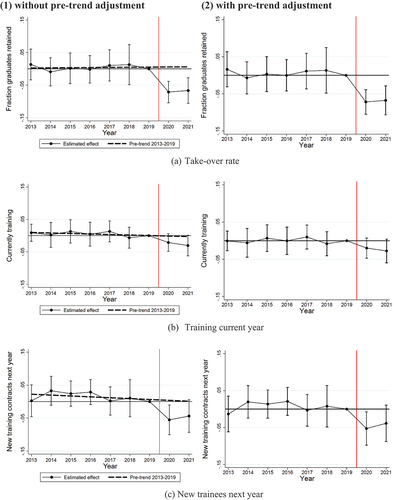

In , we present the DiD estimates for the three training outcomes: the take-over rate of recent graduates, the likelihood to train at least one trainee in the current year and the likelihood to train new trainees in the next training year.Footnote5 In column (1) of the figure, we depict the coefficient estimates before trend adjustment, together with the estimated trend, and in column (2) the trend-adjusted estimates. Control variables comprise indicator variables for federal state, establishment size measured before the pandemic (6 categories), industry (16 categories), and survey participation (81 categories).

Effect on takeovers

In the years before the pandemic, the average take-over rate evolved in a quite similar way between establishments that will be affected by the pandemic or not. This can be seen from the DiD estimates being close to zero and statistically insignificant for all years from 2013 to 2018, no matter whether we apply the trend-adjustment procedure or not. This is also true for the other outcomes, suggesting that our estimation strategy indeed identifies the causal effects of the pandemic and does not pick up some other differential developments between treated and control establishments.

In 2020, however, the average take-over rate declines suddenly and significantly for the treated establishments as compared to the control establishments (and relative to before the pandemic; see , panel (A)). The benchmark specification shows a reduction in the average take-over rate due to the pandemic by 7.2 pp. This effect is sizeable given that the average take-over rate was 74% in 2019 (before the pandemic). It persists also into the second year of the pandemic, where the reduction is still significant with 6.8 pp.

Effect on training in the current year

Next, we investigate if the pandemic induced establishments to leave the training market. In 2019, 76% of training establishments trained at least one trainee. The DiD estimates do not show a significant effect of the pandemic on the likelihood to train in 2020. The point estimates, however, are negative and increase, in absolute terms, from (minus) 2.0 pp in 2020 to (minus) 2.7 pp in 2021 (, panel (B)). The latter estimate is also statistically significant at the ten per cent level. Ultimately, in the short run, we find no evidence that the COVID-19 pandemic significantly induced establishments to cease training completely, yet at least some establishments appear to have become more likely to leave the training market in the medium run.

Effect on new training contracts for the next training year

As final outcome, we consider the likelihood that a training establishment has concluded new training contracts for the next training year, which was the case for 42% of training establishments in the 2019 survey of the IAB Establishment Panel. According to the benchmark specification, the COVID-19 pandemic reduced the probability to conclude new training contracts for the training year 2020/2021 by 5.3 pp (, panel (C)). This estimate is significant at the five per cent level. However, for 2021/2022 the effect weakens to (minus) 3.9 pp and is no longer statistically significant at the ten per cent level, suggesting some recovery of the hiring of new trainees over time.

To sum up, our benchmark estimates show that, on average, the COVID-19 pandemic did not lead establishments to exit the training market in the short run. However, it significantly reduced both the hiring of new trainees and takeovers of graduates in 2020. While the former effect tends to weaken over time, the latter effect persists into the second year of the pandemic.

Figure 2. Difference-in-differences estimates of training outcomes. (1) Without pre-trend adjustment and (2) with pre-trend adjustment.

Robustness checks

We’ve estimated different versions of our benchmark difference-in-differences regression model to test the robustness of our main findings with respect to a variety of potential confounding factors. Specifically, we’ve tested the robustness with respect to i) modelling potential pre-trends in alternative ways; ii) expanding or reducing the set of variables used to control for selective sorting into treatment status based on factors that are unrelated to the pandemic; iii) changing the composition of establishments in the control or treatment groups, respectively, to test if our results are sensitive to spill-overs of the effects of the pandemic to establishments in the control group (see Online Appendix C for details).

Overall, the results proof quite robust. Most importantly, there is no evidence that potential pre-trends, selectivity, or spill-overs lead us to overestimate the negative effects of the pandemic in the benchmark specification.

Effect heterogeneity

We’ve also explored if the effects of the pandemic vary across subgroups, specifically by location of the training establishment, industry sector, and establishment size (see Online Appendix D for details). Although the estimates by subgroup are sometimes imprecise and therefore have to be interpreted with some caution, three interesting patterns arise: First, there is evidence that the pandemic induced some establishments, particularly small establishments located in Western Germany, to leave the training market and this effect appears to increase over time. One reason why we do not see this effect in the East might be that small establishments in the East faced severe problems to fill vacant training positions already before the pandemic (Leber and Schwengler Citation2021). Vocational training might thus be of particular importance for those establishments that participate in the training market in the East.

Second, we find negative effects on takeovers in all groups of industry sectors and size, yet these tend to be stronger in the more affected sectors and in smaller establishments. Particularly the stronger effect on establishments operating in transport and hospitality is plausible as, during the lockdown, contact restrictions were most problematic for hospitality and supply bottlenecks should have played a particular role for transportation. Retaining former trainees might have been too costly especially for affected establishments in these sectors, graduates might have increasingly moved to other, less-affected sectors, or both.

Third, we do not find that very large establishments have stopped hiring new trainees due to the pandemic. We cannot rule out that they reduced the number of new training contracts, though.

Discussion

Demand versus supply

Are the negative effects of the pandemic on takeovers and new trainees that we find driven by demand or by supply side factors? As shown in , both the number of training positions supplied by establishments and the number of young people searching for a training position declined suddenly and significantly after relative to before the start of the pandemic. This suggests both channels to play a certain role.

Additional evidence from the BeCovid survey reveals that establishments’ decisions are of particular importance for the effects in the short run. In the seventh wave of this survey conducted in December 2020, establishments that planned to offer fewer or no training positions in response to the COVID-19 pandemic where asked for the reasons behind their decision. Almost all of these establishments reported that they plan to train less because of establishment-related reasons, like financial issues or insecurity about future business development. Further reasons were much rarer, including problems during the recruiting process because of contact restrictions (36%) and expected lack of suitable applicants (28%); cf. Bellmann et al. (Citation2021a).

This picture changes in the second year of the pandemic. In another wave of the BeCovid survey conducted in September 2021, the main reason for establishments to reduce the number of new training contracts was reported to be a lack of applicants, while pandemic-related restrictions on the side of the establishments were reported to play only a minor role; cf. Bellmann et al. (Citation2021b). These patterns suggest that supply-side factors have gained in importance since the end of the lockdown measures in early spring 2021. For instance, it appears plausible that young people increasingly decide against applying for training or working in establishments that suffered from strong adverse economic impacts of the pandemic.

Trends versus causal effects

It is well documented that the training market is subject to general trends that began long before the start of the pandemic. These involve not only declining supply of and demand for training positions but also increasing problems to match applicants to vacant positions (cf., among others, Matthes and Ulrich Citation2014; Dummert, Leber, and Schwengler Citation2019; Eckelt et al. Citation2020; Fitzenberger, Heusler, and Wicht Citation2023). If not controlled for, such trends could bias estimates of the causal effects of the pandemic on training (see Section ‘Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on VET’). Our estimation strategy solves this issue by comparing developments in affected and unaffected establishments, differencing-out any factors that are common to all training establishments. However, there might be effects of the pandemic that are unrelated to establishments’ affectedness and thus not picked up by our estimates. As an example, the pandemic might have induced more young people to opt for academic education instead of applying for vocational training in the dual system (cf. Raffe and Willms Citation1989; Clark Citation2011; Hillmert, Hartung, and Weßling Citation2017; Micklewright, Pearson, and Smith Citation1990). Our estimates would reflect such effects only to the extent that youths increasingly decide against training in adversely affected establishments and not in general. Although we are not aware of any evidence for such general effects so far, it should be kept in mind that the pandemic may have had effects on the training market going beyond the effects we document here.

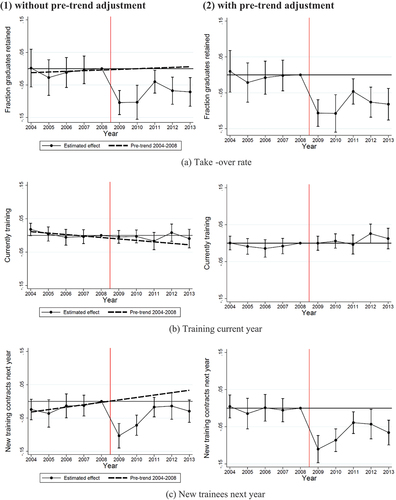

Pandemic versus great recession

Another important question is if the effects on vocational training that we find for the COVID-19 pandemic differ from those of other economic crises. Luckily, the IAB Establishment Panel allows us to produce similar estimates for the case of the Great Recession, which hit Germany in 2009.Footnote6 We show the corresponding estimates for our three training outcomes in (and Table B2 in Online Appendix B). Strikingly, in the first two crisis years, all three training outcomes responded in a very similar way to both crises: takeovers and new training contracts declined significantly, on average, but most establishments did not cease training completely. This finding is highly interesting because it provides evidence that our results are not only valid internally but also externally, which would imply that we can expect the training market to react in a similar way also in other economic crises in the future.Footnote7

Furthermore, the similar evolution of the estimates in the first two years of both crises suggests that the negative effects of the pandemic on the take-over rate and new trainees may weaken but may persist in the medium or even long run. Concerning establishments exiting the training market in response to the pandemic, however, it will be important to trace how this effect evolves as it appears to increase over time (particularly among small establishments in the West; see Section ‘Effect heterogeneity’). In the case of the Great Recession, in contrast, this effect remains flat around zero throughout.

Figure 3. Difference-in-differences estimates of training outcomes – case of the Great Recession. (1) Without pre-trend adjustment and (2) with pre-trend adjustment.

Role of other policy interventions

Finally, we discuss if our estimates of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic also pick up effects of policy interventions coinciding with the pandemic. In particular, the German Government introduced the Bundesprogramm ‘Ausbildungsplätze sichern’ (federal programme for securing training places). The programme rewards small- and medium-sized establishments that are negatively affected by the COVID-19 pandemic with financial premia if they maintain or even expand VET as compared to their pre-crisis level. The programme launched in August 2020 and might thus influence our findings. Unfortunately, with the data currently available, it is not possible to evaluate its impact directly. However, in the BeCovid survey wave from December 2020, merely 1.8% of all establishments eligible for providing training reported that they have received any kind of premia from the programme. One important aspect of this low fraction is that only 43% of those establishments responded that they do know the programme. Furthermore, only 44% of those who reported to know the programme did know its eligibility criteria (which are also quite complex). Ultimately, given these knowledge gaps and low fraction of supported establishments, we do not think that the programme plays a significant role for our findings.

Another policy intervention that might possibly influence our results is the new minimum wage for trainees in the dual system of VET that was introduced in 2020. All training contracts concluded on 1 January 2020 or thereafter are subject to a minimum remuneration of €515 per month. According to the IAB Establishment Panel, however, merely five per cent of establishments offering new training positions for the training year 2019/2020 (i.e. before the training minimum wage introduction) offered contracts remunerating less than this minimum. Moreover, we do not find that affectedness by the training minimum wage and affectedness by the COVID-19 pandemic are somehow associated. The fraction of offered training positions remunerating less than the minimum among all offered positions and the affectedness by the COVID-19 pandemic are not correlated significantly, no matter whether we look at the raw regression coefficient or add the control variables from our benchmark DiD model. We are therefore confident that the new training minimum wage plays no significant role for our findings.

Conclusion

In our study, we have estimated effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on VET in Germany. While we did not find that the pandemic induced affected establishments to exit the training market in the short run, on average, we found that it led to significant reductions in new training contracts. Additionally, we found that the pandemic reduced the average take-over rate. We also contrasted these estimates with estimates of the effects of the Great Recession on training outcomes and found that they are remarkably similar in both cases, which suggests that our results are valid not only internally but also externally.

Our findings show that the pandemic contributes to skills shortage in the near future. A declining number of new trainees intensifies the already difficult situation of lacking skills in the workforce, especially in occupations with already severe labour shortages. VET of young workers is important because it can contribute substantially to reducing this shortage and to securing the supply of skilled workers.

If young workers are unable to start an apprenticeship during the pandemic or are not taken over by their training establishment after graduation, this has potentially long-term negative effects on their career development, especially for disadvantaged youth. Although analysing these effects explicitly has to be left to future research, the available evidence suggests that programmes that foster on-the-job training and support the training-to-work transition during the COVID-19 pandemic (or crises in general) are advisable to avoid a ‘Corona cohort’.

Finally, the pandemic affects all countries worldwide and increasing skills shortage as well as negative career effects of entering the labour market in a recession are not specific to Germany, too. We therefore believe that our findings have broader implications for skill formation and individual career development during the COVID-19 pandemic in other industrialised countries and with other education systems.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (45 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank Bernd Fitzenberger, Ute Leber, Alexander Patzina, Dana Müller, Samuel Mühlemann, Brigitte Schels, and participants at the 6th international conference of the DFG Priority Program 1764, the First International Leading House Conference on the “Economics of Vocational Education and Training”, the annual conference of the Society for the Advancement of Socio-Economics (SASE) and the VfS annual conference 2022 for helpful comments and suggestions. We also thank our colleagues of the research department “Establishments and Employment” at the IAB for their support. We also thank the editor as well as the anonymous referees of this Journal and recognise their help and guidance. The usual disclaimer applies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820.2023.2280953

Notes

1. Establishments are defined as economically and regionally separate operational units. Several different establishments may belong to the same company.

2. Every year, the IAB Establishment Panel surveys the total number of trainees at the establishment on June 30 of both the current and the previous year.

3. Another potential problem of our affectedness measure is reverse causality, since the data were collected after the start of the pandemic. However, we are confident that potential reverse causality does not bias our results because the questions focus on economic impacts of the pandemic. It appears rather unlikely that the pandemic has significant negative effects on economic performance (the treatment) through its impact on vocational training activities (the outcomes) in the two years after the start of the pandemic. The contribution of trainees to added value is generally small and securing skilled personnel in the future is the main reason why establishments train in Germany (Schönfeld et al. Citation2020).

4. This drop is somewhat larger than the one observed during the Great Recession, where the number of new training contracts fell by 8.4% between 2008 and 2009 (Schuß et al. Citation2021).

5. The estimates are also displayed in Table B1 in Online Appendix B.

6. The specifications are not exactly identical. For the Great Recession, we have only four pre-treatment years available because we cannot measure outcomes consistently before 2004. The questions on the adverse economic impacts also differ somewhat. Most importantly, the affectedness by the pandemic refers to the first year of the crisis, 2020, while it refers to the second year, 2010, for the Great Recession. We therefore do not put too much emphasis on the point estimates but rather compare the overall patterns of the effects between the two crises.

7. Institutional particularities of the system, like the predominately longer-term investment-orientated training motive, as discussed in Section ‘Background and Data’, could have prevented more establishments from leaving the training market during both the Great Recession and the COVID-19 pandemic and thus could have helped to avoid even more severe adverse effects.

References

- Acemoglu, Daron, and Jörn-Steffen Pischke. 1998. “Why Do Firms Train? Theory and Evidence.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 11 (1): 79–119. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355398555531.

- Achatz, Juliane, Kerstin Jahn, and Brigitte Schels. 2022. “On the Non-Standard Routes: Vocational Training Measures in the School-To-Work Transitions of Lower-Qualified Youth in Germany.” Journal of Vocational Education & Training 74 (2): 289–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820.2020.1760335.

- Altonji, Joseph G., Lisa B. Kahn, and Jamin D. Speer. 2016. “Cashier or Consultant? Entry Labour Market Conditions, Field of Study, and Career Success.” Journal of Labour Economics 34 (S1): 361–401. https://doi.org/10.1086/682938.

- Autor, David H., Frank Levy, and Richard J Murnane. 2003. “The Skill Content of Recent Technological Change: An Empirical Exploration.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 118 (4): 1279–1333. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355303322552801.

- Baldi, Guido, Imke Brüggemann-Borck, and Thore Schlaak. 2014. “The Effect of the Business Cycle on Apprenticeship Training: Evidence from Germany.” Journal of Labour Research 35 (4): 412–422. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-014-9192-6.

- Bell, David N. F., and David G. Blanchflower. 2011. “Young People and the Great Recession.” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 27 (2): 241–267. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/grr011.

- Bellmann, Lutz. 2022. “Demand for Skilled Employees and the German Vocational Training System.” In The ‘Betrieb’ as Corporate Actor, 214–227. Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG. https://doi.org/10.5771/9783957103963.

- Bellmann, Lutz, Bernd Fitzenberger, Patrick Gleiser, Christian Kagerl, Eva Kleifgen, Theresa Koch, Corinna König. 2021a. “Jeder zehnte ausbildungsberechtigte Betrieb könnte im kommenden Ausbildungsjahr krisenbedingt weniger Lehrstellen besetzen.” IAB-Forum. https://www.iab-forum.de/jeder-zehnte-ausbildungsberechtigte-betrieb-koennte-im-kommenden-ausbildungsjahr-krisenbedingt-weniger-lehrstellen-besetzen/.

- Bellmann, Lutz, Margit Ebbinghaus, Bernd Fitzenberger, Christian Gerhards, Patrick Gleiser, Sophie Hensgen, Christian Kagerl. 2021b. “Der Mangel an Bewerbungen bremst die Erholung am Ausbildungsmarkt.” IAB-Forum. https://www.iab-forum.de/der-mangel-an-bewerbungen-bremst-die-erholung-am-ausbildungsmarkt/.

- Bellmann, Lutz, Hans-Dieter Gerner, and Ute Leber. 2014. “Firm-Provided Training During the Great Recession.” Jahrbücher für Nationalökonomie und Statistik 234 (1): 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1515/jbnst-2014-0103.

- Bellmann, Lutz, Patrick Gleiser, Sophie Hensgen, Christian Kagerl, Ute Leber, Duncan Roth, Matthias Umkehrer, and Jens Stegmaier. 2022. “Establishments in the Covid-19-Crisis (BeCovid): A High-Frequency Establishment Survey to Monitor the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Jahrbücher für Nationalökonomie und Statistik 242 (3): 421–431. https://doi.org/10.1515/jbnst-2022-0028.

- BIBB (Federal Institute for Vocational Education and Training). 2021. Neu abgeschlossene Ausbildungsverträge - Ergebnisse der BIBB-Erhebung zum 30. September 2021, Stand: 09.12.2021”. Accessed June 29, 2022. https://www.bibb.de/de/140900.php.

- Blatter, Marc, Samuel Muehlemann, and Samuel Schenker. 2012. “The Cost of Hiring Skilled Workers.” European Economic Review 56 (1): 20–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2011.08.001.

- Blatter, Marc, Samuel Muehlemann, Samuel Schenker, and Stefan C. Wolter. 2016. “Hiring Costs for Skilled Workers and the Supply of Firm-Provided Training.” Oxford Economic Papers 68 (1): 238–257. https://doi.org/10.1093/oep/gpv050.

- Brunello, Giorgio. 2009. “The Effect of Economic Downturns on Apprenticeships and Initial Workplace Training: A Review of the Evidence.” Empirical Research in Vocational Education and Training 1 (2): 145–171. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03546484.

- Brzinsky-Fay, Christian, and Heike Solga. 2016. “Compressed, Postponed, or Disadvantaged? School-To-Work-Transition Patterns and Early Occupational Attainment in West Germany.” Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 46 (Part A): 21–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2016.01.004.

- Clark, Damon. 2011. “Do Recessions Keep Students in School? The Impact of Youth Unemployment on Enrolment in Post‐Compulsory Education in England.” Economica 78 (311): 523–545. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0335.2009.00824.x.

- Deutschlandfunk. 2020. “Interview Hubertus Heil (SPD): Wir können uns keinen Corona-Jahrgang erlauben.” Accessed July 20, 2021. https://www.deutschlandfunk.de/bonus-fuer-ausbildungsbetriebe-hubertus-heil-spd-wir.694.de.html?dram:article_id=494210.

- Dietrich, Hans, and Hans-Dieter Gerner. 2007. “The Determinants of Apprenticeship Training with Particular Reference to Business Expectations.” Zeitschrift für ArbeitsmarktForschung 40 (2/3): 221–233.

- Dummert, Sandra. 2021. “Employment Prospects After Completing Vocational Training in Germany from 2008-2014: A Comprehensive Analysis.” Journal of Vocational Education & Training 73 (3): 367–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820.2020.1715467.

- Dummert, Sandra, Ute Leber, and Barbara Schwengler. 2019. “Unfilled Training Positions in Germany–Regional and Establishment-Specific Determinants.” Jahrbücher für Nationalökonomie und Statistik 239 (4): 661–701. https://doi.org/10.1515/jbnst-2018-0014.

- Dustmann, Christian, Attila Lindner, Uta Schönberg, Matthias Umkehrer, and Philipp vom Berge. 2022. “Reallocation Effects of the Minimum Wage.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 137 (1): 267–328. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjab028.

- Dustmann, Christian, and Uta Schönberg. 2009. “Training and Union Wages.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 91 (2): 363–376. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest.91.2.363.

- Eckelt, Marcus, Sabine Mohr, Christian Gerhards, and Claudia Burkard. 2020. Rückgang der betrieblichen Ausbildungsbeteiligung. Gründe und Unterstützungsmaßnahmen mit Fokus auf Kleinstbetriebe. Bonn.

- Eichhorst, Werner, Paul Marx, and Ulf Rinne. 2021. “IZA COVID-19 Crisis Response Monitoring: The Second Phase of the Crisis.” IZA Research Report no. 105. https://docs.iza.org/report_pdfs/iza_report_105.pdf.

- Eichhorst, Werner, Nuria Rodríguez-Planas, Ricarda Schmidl, and Klaus F. Zimmermann. 2015. “A Roadmap to Vocational Education and Training in Industrialized Countries.” Industrial and Labour Relations Review 68 (2): 314–337. https://doi.org/10.1177/0019793914564963.

- Ellguth, Peter, Susanne Kohaut, and Iris Möller. 2014. “The IAB Establishment Panel - Methodological Essentials and Data Quality.” Journal of Labour Market Research 47 (1–2): 27–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12651-013-0151-0.

- Fersterer, Josef, Jörn-Steffen Pischke, and Rudolf Winter-Ebmer. 2008. “Returns to Apprenticeship Training in Austria: Evidence from Failed Firms.” The Scandinavian Journal of Economics 110 (4): 733–753. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9442.2008.00559.x.

- Fitzenberger, Bernd, Anna Heusler, and Leonie Wicht. 2023. “Die Vermessung der Probleme am Ausbildungsmarkt: Ein differenzierter Blick auf die Datenlage tut not.” IAB-Forum. https://doi.org/10.48720/IAB.FOO.20230621.01. June 21, 2023.

- Fitzenberger, Bernd, Stefanie Licklederer, and Hanna Zwiener. 2015. “Mobility Across Firms and Occupations Among Graduates from Apprenticeship.” Labour Economics 34:138–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2015.03.008.

- Gregg, Paul. 2001. “The Impact of Youth Unemployment on Adult Unemployment in the NCDS.” The Economic Journal 111 (475): F626–F653. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0297.00666.

- Harhoff, Dietmar, and Thomas J. Kane. 1997. “Is the German Apprenticeship System a Panacea for the U.S. Labour Market?” Journal of Population Economics 10 (2): 171–196. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001480050037.

- Hillmert, Steffen, Andreas Hartung, and Katarina Weßling. 2017. “A Decomposition of Local Labour-Market Conditions and Their Relevance for Inequalities in Transitions to Vocational Training.” European Sociological Review 33 (4): 534–550. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcx057.

- Hippach-Schneider, Ute, Martina Krause, and Christian Woll. 2007. Vocational Education and Training in Germany: Short Description. Thessaloniki: European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training.

- Leber, Ute, and Barbara Schwengler. 2021. “Betriebliche Ausbildung in Deutschland: Unbesetzte Ausbildungsplätze und vorzeitig gelöste Verträge erschweren Fachkräftesicherung.” IAB-Kurzbericht 03/2021: 8,

- Lindley, Robert M. 1975. “The Demand for Apprentice Recruits by the Engineering Industry, 1951‐71.” Scottish Journal of Political Economy 22 (1): 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9485.1975.tb00043.x.

- Luijkx, Ruud, and Maarten HJ Wolbers. 2009. “The Effects of Non-Employment in Early Work-Life on Subsequent Employment Chances of Individuals in the Netherlands.” European Sociological Review 25 (6): 647–660. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcp002.

- Maier, Tobias. 2020. Auswirkungen der “Corona-Krise” auf die duale Berufsausbildung: Risiken, Konsequenzen und Handlungsnotwendigkeiten. Bonn: Bundesinstitut für Berufsbildung.

- Manzoni, Anna, and Irma Mooi-Reci. 2011. “Early Unemployment and Subsequent Career Complexity: A Sequence-Based Perspective.” Journal of Contextual Economics – Schmollers Jahrbuch 131 (2): 339–349. https://doi.org/10.3790/schm.131.2.339.

- Matthes, Stephanie, and Joachim G. Ulrich. 2014. ““Wachsende Passungsprobleme auf dem Ausbildungsmarkt“.” Berufsbildung in Wissenschaft und Praxis - BWP 43 (1): 5–7.

- Micklewright, John, Mark Pearson, and Stephen Smith. 1990. “Unemployment and Early School Leaving.” The Economic Journal 100 (400): 163–169. https://doi.org/10.2307/2234193. doi.

- Mohrenweiser, Jens, and Uschi Backes‐Gellner. 2010. “Apprenticeship Training: For Investment or Substitution?” International Journal of Manpower 31 (5): 545–562. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437721011066353.

- Muehlemann, Samuel, Harald Pfeifer, Günter Walden, Felix Wenzelmann, and Stefan C. Wolter. 2010. “The Financing of Apprenticeship Training in the Light of Labour Market Regulations.” Labour Economics 17 (5): 799–809. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2010.04.006.

- Muehlemann, Samuel, Harald Pfeifer, and Bernhard H. Wittek. 2020. “The Effect of Business Cycle Expectations on the German Apprenticeship Market: Estimating the Impact of Covid-19.” Empirical Research in Vocational Education and Training 12 (8). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40461-020-00094-9.

- Muehlemann, Samuel, and Stefan Wolter. 2021. “Business Cycles and Apprenticeships.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Economics and Finance. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190625979.013.655.

- Muehlemann, Samuel, Stefan C. Wolter, and Adrian Wüest. 2009. “Apprenticeship Training and the Business Cycle.” Empirical Research in Vocational Education and Training 1 (2): 173–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03546485.

- Nilsen, Øivind A., and Katrine Holm Reiso. 2014. “Scarring Effects of Early-Career Unemployment.” Nordic Economic Policy Review 1:13–46. https://doi.org/10.6027/US2014-416.

- Oeynhausen, Stephanie, Bettina Milde, Joachim G. Ulrich, Simone Flemming, and Ralf-Olaf Granath. 2020. “Die Entwicklung des Ausbildungsmarktes im Jahr 2020. Analysen auf Basis der BIBB-Erhebung über neu abgeschlossene Ausbildungsverträge und der Ausbildungsmarktstatistik der Bundesagentur für Arbeit zum Stichtag 30. September. Bonn: Bundesinstitut für Berufsbildung (BIBB).

- Oreopoulos, Philip, Till von Wachter, and Andrew Heisz. 2012. “The Short- and Long-Term Career Effects of Graduating in a Recession.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 4 (1): 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.4.1.1.

- Protsch, Paula, and Heike Solga. 2015. “The Social Stratification of the German VET System.” Journal of Education & Work 29 (6): 637–661. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2015.1024643.

- Raffe, David, and Douglas J. Willms. 1989. “Schooling the Discouraged Worker: Local-Labour-Market Effects on Educational Participation.” Sociology 23 (4): 559–581. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038589023004004.

- Riphahn, Regina. T., and Michael Zibrowius. 2016. “Apprenticeship, Vocational Training, and Early Labour Market Outcomes – Evidence from East and West Germany.” Education Economics 24 (1): 33–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/09645292.2015.1027759.

- Scandurra, Rosario, Ruggero Cefalo, and Yuri Kazepov. 2021. “Drivers of Youth Labour Market Integration Across European Regions.” Social Indicators Research: An International and Interdisciplinary Journal for Quality-Of-Life Measurement 154 (3): 835–856. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02549-8.

- Schmillen, Achim, and Matthias Umkehrer. 2018. “The Scars of Youth: Effects of Early-Career Unemployment on Future Unemployment Experience.” International Labour Review 156 (3–4): 465–494. https://doi.org/10.1111/ilr.12079.

- Schönfeld, Gudrun, Felix Wenzelmann, Harald Pfeifer, Paula Rislus, and Caroline Wehner. 2020. “Ausbildung in Deutschland – eine Investition gegen den Fachkräftemangel. Ergebnisse der BIBB-Kosten-Nutzen-Erhebung 2017/2018.” BIBB-Report 1/2020. https://www.add-on.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Kosten-Nutzenrechnung-duale-Ausbildung-2020_BIBB-Report_01_2020_barrierefrei.pdf.

- Schuß, Eric, Alexander Christ, Stephanie Oeynhausen, Bettina Milde, Simone Flemming, and Ralf-Olaf Granath. 2021. “Die Entwicklung des Ausbildungsmarktes im Jahr 2021. Analysen auf Basis der BIBB-Erhebung über neu abgeschlossene Ausbildungsverträge und der Ausbildungsmarktstatistik der Bundesagentur für Arbeit zum Stichtag 30. September. Bonn: Bundesinstitut für Berufsbildung (BIBB).

- Soskice, David. 1994. “Reconciling Markets and Institutions: The German Apprenticeship System.” In Training and the Private Sector. International Comparisons, edited by Lisa M. Lynch, 25–60. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Stevens, Margaret. 1994. “An Investment Model for the Supply of Training by Employers.” The Economic Journal 104 (424): 556–570. https://doi.org/10.2307/2234631.

- Stuth, Stefan, and Kerstin Jahn. 2020. “Young, Successful, Precarious? Precariousness at the Entry Stage of Employment Careers in Germany.” Journal of Youth Studies 23 (6): 702–725. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2019.1636945.

- Umkehrer, Matthias. 2019. “Heterogenous Effects of Entering the Labour Market During a Recession - New Evidence from Germany.” CESifo Economic Studies 65 (2): 177–203. https://doi.org/10.1093/cesifo/ifz003.

- von Wachter, Till. 2020. “The Persistent Effects of Initial Labour Market Conditions for Young Adults and Their Sources.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 34 (4): 168–194. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.34.4.168.

- von Wachter, Till, and Stefan Bender. 2006. “In the Right Place at the Wrong Time: The Role of Firms and Luck in Young Workers’ Careers.” The American Economic Review 96 (5): 1679–1705. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.96.5.1679.

- Winkelmann, Rainer. 1996. “Employment Prospects and Skill Acquisition of Apprenticeship-Trained Workers in Germany.” Industrial and Labour Relations Review 49 (4): 658–672. https://doi.org/10.1177/001979399604900405.

- Wolter, Stefan C., and Paul Ryan. 2011. “Apprenticeship.” In Handbook of the Economics of Education, edited by Eric A. Hanushek, Stephen J. Machin, and Ludger Woessmann, 3 521–576. Amsterdam: North-Holland.