ABSTRACT

Graduate unemployment has increasingly been the topic of research interest as it grows in many countries. In many such contexts, the massification of higher education and the global economic recession of the late 2000s explain the challenge. The situation differs in South Africa. Graduate unemployment rates are low owing to the high demand for skilled labour. However, certain groups of graduates continue to struggle to find employment. While previous research has described which graduates are more vulnerable to unemployment, few studies have assessed the reasons for their struggle. We address this gap by presenting data from a mixed methods study, which included a sub-sample of unemployed graduates, on the barriers these graduates face. The findings show that lack of relevant work experience, limited information about an efficient job search, low social capital, and high costs of work-seeking create obstacles to securing work. We reiterate recommendations from prior research that calls for better integration of qualifications with practical work experience, but also contend that accessible work-seeker support can mitigate the negative effects of the identified barriers. Such investments are critical to ensuring that significant investments in post-secondary education and training on the part of both the state and the individual graduate are realised.

Introduction

I was applying online, like I said, I’m always going online and applying, keep applying, keep applying, keep applying … blah, blah, blah.

(Mpho, male graduate, National Diploma in Human Resources Management)

Table 1. Profile of interview participants, including employment status.

Mpho’s story reflects those of a number of graduates in South Africa where the supposed challenge of graduate unemployment has received a great deal of media attention. However, there is debate as to whether graduate unemployment is, in fact, a challenge in South Africa. Some evidence shows that graduate unemployment is not a crisis in South Africa with graduates facing very low unemployment rates when compared to their non-graduate counterparts (Van der Berg & Van Broekhuizen Citation2012; Van Broekhuizen & Van der Berg Citation2016). Other evidence suggests that while graduate unemployment is low, it has been increasing (Pauw, Oosthuizen, and Van Der Westhuizen Citation2008; Van Rheede Citation2012; Reddy Citation2016). Unlike countries such as Sri Lanka, Egypt, Morocco, Algeria, Taiwan, Greece and China, which are contending with large and increasing graduate unemployment levels (Samaranayake Citation2016; Stewart Citation2015; Joshua et al. Citation2015; Li, Whalley, and Xing Citation2014; Broecke Citation2013; Wu Citation2011; Livanos Citation2010), South Africa’s degree graduates face only an 8% risk of being unemployed as compared to those with only a school-leaving certificate who have a 55% likelihood of being unemployed (Van der Berg and Hendrik Citation2012; van Broekhuizen and Berg Citation2016). One of the main reasons for this is the skills mismatch in the labour market. In South Africa, there is a premium on skills in the labour market because where growth in jobs has occurred, this has been in the tertiary sector, which requires higher levels of skills (Banerjee et al. Citation2007). This, in turn, means that there is more demand for graduates in the labour market; a situation that is fundamentally different to other developing contexts where there has been the massification of higher education, without the requisite growth in jobs that demand higher skills levels to absorb graduates (Mok Citation2016).

However, the low graduate unemployment rate masks the fact that graduates in South Africa are not a homogenous group. Rates of unemployment vary for different groups of graduates, and there are marked differences in their transitions to the labour market. Some graduates find employment shortly after graduating, others experience chronic unemployment (defined as unemployment longer than 12 months) despite their qualifications (Kraak Citation2010). These nuances are often overlooked in the literature on graduate unemployment.

In this article, we argue that, while graduate unemployment is not necessarily a major challenge when compared to international trends or the national youth unemployment challenge, it is important to consider that different kinds of graduates experience the transition to work differently and that particular groups might face different challenges in finding and securing work. In a context of high youth unemployment generally, addressing such barriers is critical to smoothing pathways to work for graduates, and may point to challenges that non-graduates face too. South Africa has very low rates of participation in higher and further education – only 8% of young people between the ages of 15 to 24 are enrolled in either a university or a college programme (Branson and Hofmeyr Citation2015). Given this low rate and the fact that labour market outcomes are positive for those with both college and university qualifications, we consider both groups as ‘graduates’ for the purposes of this study.

There is ample literature on the profile of graduates and which groups are more affected by unemployment in South Africa. This article aims to go a step further by providing insights into what factors affect the transition to the labour market, making it a protracted one for particular groups of graduates. We provide evidence on the household and community level barriers that serve to effectively ‘lock’ certain graduates out of the labour market.

The article presents data from a mixed-methods study of young people who participated in youth employability programmes. We present evidence from a subsample of a survey conducted with 1 986 youth employability programme participants, in which questions about their demographic and educational backgrounds as well as their employment and work-seeking experience were asked. In the overall sample, over a third of programme participants (35%) had obtained a post-secondary qualification – either a certificate, diploma or degree – and are referred to collectively for the purposes of this article as graduates. This article focuses on this sub-sample of participants in order to understand their demographic backgrounds and what barriers they face in securing employment. In-depth interviews were also conducted with 12 of these participants, to better understand their education to work trajectories.

Contextualising graduate unemployment

The structural or systemic drivers of graduate unemployment internationally are well documented. Globally, graduate unemployment is attributed to the global economic recession of 2008 and the expansion of access to higher education (Bai Citation2006; Wu Citation2011; Jonck Citation2014). The rapid expansion of higher education over time, it is argued, contributes to high graduate unemployment due to an over-supply of skilled labour that is not met by an increase in demand. Another recurring contributing factor to graduate unemployment in the literature is a systemic skills mismatch between the education system and the economy (Livanos Citation2010; Joshua et al. Citation2015; Mogomotsi and Madigele Citation2017). The argument is that the education system does not adequately prepare graduates for future jobs and market demands and that employers are reluctant to hire young people or graduates because of the costs associated with upskilling them. These issues are pertinent to explaining graduate unemployment globally. But the situation differs considerably in South Africa.

Graduate unemployment in South Africa

Graduate unemployment should be understood within the broad context of high levels of unemployment in South Africa. More than a quarter (28.8%) of the labour force is unemployed according to the strict definition (Statistics South Africa Citation2018). Black Africans and Coloureds, women, people in rural areas, those without post-secondary education, and youth bear the brunt of unemployment. Just under half (43.2%) of labour market active 15–24-year-olds are unemployed according to the expanded definition of unemployment (Statistics South Africa Citation2018).

The skills mismatch and youth unemployment in South Africa

There is a myriad of factors that shape the disproportionately high levels of unemployment among youth in South Africa, but one of the major features is what is termed the skills mismatch in the labour market. Demand-led drivers emanate from the high technology-driven growth path followed in the post-apartheid era, which gives preference to high skill levels (Seekings and Nattrass Citation2005; Banerjee et al. Citation2007). Sectors that demand higher skills, like the financial services sector, are experiencing employment growth, whereas sectors, such as agriculture that favour entry-level skills, have been contracting (Banerjee et al. Citation2007). This is within a context where there is an oversupply of low, entry-level skills (Reddy Citation2016). This skills mismatch ensures that there is a premium on qualifications in the labour market and that in part explains why graduates in South Africa have better employment outcomes than youth with no post-secondary education and training.

The oversupply of work-seekers with low skills levels is an outcome of failures in the education system. Although the democratic government celebrates gender parity and almost universal enrolment in primary school (Statistics South Africa Citation2016a), skills shortages persist. These skills shortages are exacerbated by poor quality basic education (Spaull Citation2013, Citation2015), high rates of dropout in secondary school (Weybright et al. Citation2017), and enduring barriers to accessing higher education (Branson and Hofmeyr Citation2015; Perold, Cloete, and Papier Citation2012). Dropout in basic education is pronounced in quintile 1 to 3, poorer schools, still primarily attended by Black African and Coloured learners (Isdale et al. Citation2016). This means that large proportions of young people do not qualify for university studies. Although they could complete their schooling via the Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) colleges, participation rates in these institutions remain low (Statistics South Africa Citation2015). Overall, despite government’s increasing financial investments in post-secondary education, national participation rates at universities and TVET colleges remain low when compared to other middle-income countries, which may also explain the relatively lower graduate unemployment rates when compared to other countries. In fact, in many other countries, high levels of graduate unemployment are often attributed to the massification of higher education (Bai Citation2006; Wu Citation2011; Li, Whalley, and Xing Citation2014; Samaranayake Citation2016; Mok and Neubauer Citation2016).

Differences in returns to higher education in the South African labour market

The benefits associated with higher levels of education are well established. Individuals in the South African labour force with less than matric are seven times more likely to be unemployed than those with post-secondary education. Those with matric are five times more likely to be unemployed than ones with tertiary education (Reddy Citation2016). Graduates also tend to earn more (Bhorat, Mayet, and Visser Citation2010; Livanos Citation2010). However, the benefits of higher education are not equally shared and graduates are not a homogenous group.

Graduates with degrees remain better off than those with diplomas (Pauw et al. Citation2006; CHEC Citation2013; Jonck Citation2014; Baldry Citation2016). One in every five diploma graduates (20%) are unemployed as opposed to 9% of degree graduates (Development Policy Research Unit Citation2017). Kraak (Citation2010) reports higher levels of unemployment among diploma graduates who studied Business, Commerce and Management courses compared to diploma graduates who studied Physics, Mathematics, Computer and Life Sciences. The Cape Higher Education Consortium (CHEC Citation2013) attributes higher rates of unemployment among diploma graduates to employers’ increased interest in employing degree holders. Similarly, Pauw et al. (Citation2006) argue that employer perceptions of the quality of education offered at TVET colleges may be another reason for the poorer employment prospects of diploma and certificate graduates compared to degree graduates. Limited opportunities for work-integrated learning is a possible contributing factor to higher unemployment among students from TVET colleges and universities of technology (Kraak Citation2010). The implication is that students are unable to graduate, and their chances of finding employment are reduced because of the incomplete qualification.

In addition to differences by type of qualification, there is also evidence that race shaped employment outcomes for graduates. Evidence demonstrates that unemployment rates among black graduates are significantly higher than for white graduates (Van Rheede Citation2012; CHEC Citation2013; Baldry Citation2016; Mncayi and Dunga Citation2016; Rogan et al. Citation2015). In addition, unemployment and often chronic unemployment is prevalent among black graduates (Baldry Citation2016; Mncayi and Dunga Citation2016). Some researchers assert that discrimination in employer recruitment practices that favour white graduates may be another contributing factor to differential employment rates among black and white graduates (Kraak Citation2010). Pauw et al. (Citation2006) note that employers perceive differences in the quality of education received by black and white graduates, especially where black graduates previously attended socio-economically disadvantaged schools. Nevertheless, unemployment remains higher among black graduates regardless of the type of institution and the nature of qualification (Bhorat, Mayet, and Visser Citation2010). Black graduates from HWIs with Science, Engineering and Technology (SET) qualifications were most likely to be unemployed compared to their white counterparts who studied the same qualification at the same institutions (Bhorat, Mayet, and Visser Citation2010). Moleke (Citation2005) found that white graduates secure work almost immediately after graduation, regardless of the field of study, while other race groups take significantly more time to access work. White graduates’ greater access to social networks benefits their transitions to the labour market (Bhorat, Mayet, and Visser Citation2010; Kraak Citation2010).

The nature of job search strategies used emerges as another reason for varying employment prospects for white and black graduates. Several studies (Kraak Citation2010; CHEC Citation2013; Rogan et al. Citation2015) report that white graduates find employment mainly through social networks, whereas black graduates make use of ineffective methods, such as responding to newspaper adverts, because they lack social capital. Graduates from low socio-economic backgrounds, from rural areas and who live with unemployed household members are more prone to unemployment (Baldry Citation2016).

The type of institution that one graduates from also emerges as a feature that shapes employment prospects. Some studies found that graduates from historically black institutions (HBIs)Footnote1 take a prolonged time to transition to the labour market and experience higher unemployment than their counterparts who graduated at historically white institutions (HWIs) (Moleke Citation2005; CHEC Citation2013; Oluwajodu et al. Citation2015; Rogan et al. Citation2015). Findings suggest that studying at an HWI shields graduates against unemployment regardless of race. Unemployment is lower among black graduates from the University of Witwatersrand (HWI) compared to black graduates from the University of Fort Hare (HBI) (Bhorat, Mayet, and Visser Citation2010). Similarly, Rogan et al. (Citation2015) found higher unemployment among graduates at Fort Hare University (HBI) compared to their counterparts at Rhodes University (HWI), regardless of race. According to Moleke (Citation2005), this phenomenon may be due to employer perceptions of the quality of education offered at the various institutions or, HBIs producing an over-supply of students who graduate in fields with lower employment prospects (i.e. Humanities, Arts and Education). In a study that investigated unemployment among graduates in the banking sector in South Africa (Oluwajodu et al. Citation2015), recruitment managers for the banks admitted that they mainly recruit graduates from HWIs because they perceive them to have high educational standards.

There are also particular gender trends. Unemployment is highest among female graduates (CHEC Citation2013; Mncayi and Dunga Citation2016), which could be attributed to higher unemployment rates among females in general. However, Moleke (Citation2005) notes that the field of study plays a role with females who acquired qualifications in fields like humanities and law taking a longer time to find employment after graduation than those who graduated in fields with a specialised focus like medicine or engineering, where males were more likely to be represented.

The literature is divided on the association between field of study and graduate (un)employment. Some studies cite a significant association between field of study and employment (Moleke Citation2005; Baldry Citation2016; Mncayi and Dunga Citation2016) with unemployment highest among graduates who studied general courses, like humanities, and lowest among those who studied professional-oriented courses, such as medical sciences and engineering. Livanos (Citation2010) found similar findings among graduates in Greece with higher unemployment among graduates who studied sociology, librarianship, arts and humanities as opposed to those who studied medicine or law. However, other studies did not find evidence of an association between field of study and graduate (un)employment (Van der Berg and Van Broekhuizen Citation2012; Rogan et al. Citation2015).

Cosser (Citation2003) found that insufficient numbers of youth obtain career guidance at school or while studying at further or higher education. This, he argues, influences their choice of studies, which in turn influences their labour market outcomes. Mncayi and Dunga (Citation2016) found a significant association between use of career guidance services and employment with more than half of unemployed graduates confirming that they did not access this service while studying. Other studies have found a weak or no association between receipt of career guidance services and employment outcomes (Baldry Citation2016; CHEC Citation2013).

There is also a significant association between age and employment with unemployment highest among younger graduates (Pauw et al. Citation2006; CHEC Citation2013); Oluwajodu et al. Citation2015; Carnevale and Cheah Citation2015). This finding corresponds with unemployment trends in general and may be because younger graduates lack work experience.

The above discussion has revealed the factors that are associated with higher levels of unemployment among certain groups of graduates, but there is very limited literature on how graduates experience unemployment and work-seeking, and specifically on how household and community level factors (as opposed to demographics) shape their employment outcomes. This is a gap that the current study aims to address.

Methodology

In this article, we report on the findings for a sub-sample of a wider study of participants of youth employability programmes in South Africa. In the full sample, 1 986 young people who were entering youth employability programmes participated in a survey in which data were collected through a self-completed questionnaire, the completion of which was facilitated by experienced fieldworkers who were available to clarify questions and guide the completion of the questionnaires. The questionnaire covered demographic information, education background, household profile information, including household income, and employment and unemployment experiences.

The participants were drawn from eight youth employability programmes, each offering a combination of technical and general workplace (soft) skills. Across the eight programmes, there were 48 training sites. Although there were training sites in all provinces, there was a concentration of training sites in urban areas, and particularly in the main economic centres of Cape Town and Johannesburg, meaning that there is an over-representation of urban participants. Youth employability programmes do have entry criteria. Most had matric as an entry-level requirement with only two of the programmes accepting young people with less than a matric. Young people also self-select into the programmes meaning that they are likely to be young people who take initiative. They are therefore not representative of the broader youth population.

Of the full sample, 587 participants were young people who had some form of post-secondary qualification ranging from certificates to degrees and were unemployed at the time of the survey. We grouped these participants together as unemployed graduates and in this article, we report on the findings for this group only. We do so in order to better understand some of the household and community level barriers facing these young people – a focus that the review of literature has revealed as a knowledge gap. The data were analysed descriptively for this sample.

In addition, we conducted in-depth interviews with a purposively sampled group of the participants who had completed the survey. They were interviewed nine months after completing the youth employability programme. From the sample of unemployed graduates surveyed as they entered the youth employability programme, we sought to conduct in-depth interviews with those who were at different phases of their transition to the labour market, post-completion of the programme. We therefore purposively sampled 11 participants, six of whom were unemployed at the time of the follow-up interviews. There were six females and five males in the sample for the in-depth interviews, and while we sought an even spread between urban and rural youth, the majority of those sampled were located in urban areas, having moved to these centres in search of work. The interviews focused on their experiences after completing the training and how they explain the process of work-seeking, working or not working. The interviews were analysed thematically. The provides an overview of the in-depth interviewees.

Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from The University of Johannesburg Faculty of Humanities Ethics Committee. Participants were provided with detailed information about the study before volunteering to participate. They signed an informed consent form if they were willing to participate. They were advised that they did not need to answer questions that they felt uncomfortable answering. Surveys were conducted at the sites of their training, thus ensuring that they incurred no costs for participating in the survey. They were interviewed at a convenient location for them for the in-depth interviews and reimbursed for their travel costs. There were no adverse consequences if they chose not to participate. They were guaranteed confidentiality and, as such, their names have been changed in the reporting of the findings in this article.

The reliability and validity of the research were enhanced in a number of ways. We conducted validation interviews during the piloting phase of the survey. This involved asking the survey questions and then interviewing pilot participants about what they understood by the questions. This process ensured that there was a high level of internal validity. We also used standardised measures where possible to further enhance the internal validity of the instrument. Experienced fieldworkers were trained on the purpose of the research, ethical procedures, data collection procedures and the questionnaire. All data were quality assured by experienced fieldwork supervisors.

The authenticity and credibility of the qualitative component of the study were enhanced by piloting the interview guide prior to interviews being conducted, ensuring that only experienced interviewers were involved in the data collection, conducting check-backs with participants to ensure that their comments were interpreted as intended, and a process of team analysis to limit bias in interpretation of the transcripts.

Findings

Overview of the youth employability programmes

Although the purpose of this article is not to assess the outcomes of the programmes, some of the recommendations arising pertain to programme content, and it is therefore important to provide an overview of the training that the programmes provide. All of the programmes provided a combination of technical and soft skills training. Technical skills training across the programmes included information technology technical support, call centre operations, retail skills and welding. Soft skills training included self-assessment, learning to work within a team, conflict resolution and basic workplace skills including computer processing. Some of the programmes also included information on how to put one's CV together, and how to prepare for an interview although for most programmes this was ad hoc and not documented as part of their curricula. Two of the programmes included workplace learning as part of the curricula. Only two of the eight organisations facilitated interactions with potential employers and were demand-led (that is, they trained young people based on what employers were looking for).

Demographic and educational profile of the sample

Of the graduates in the sample, the majority had completed certificates (43%) or diplomas (39%). Less than a fifth (17%) had attained a degree or higher. The participants’ levels of education were higher than that of their parents. This is consistent with other studies in South Africa, which show that today’s youth have higher levels of education than their parents (South African Labour & Development Research Unit (SALDRU) Citation2016).

In addition to their formal qualifications, they were attending a youth employability training programme at the time of the survey. Further, over half of the participants (60.7%) had previously attended other, mainly short-term skills training programmes. This demonstrates that the transition to employment for this group of graduates is a protracted one and that unemployed graduates are moving into and out of training programmes as a way of attempting to enhance their skills profile, but evidently with limited success.

Graduates in the study were mainly younger (18–24 years) (71%). This is because employability programmes target younger youth as early intervention is key to prevent chronic unemployment. The remainder of the sample fell into the older age group (25–35 years) and the mean age of the sample was 24 years.

The employability programmes through which the graduates were recruited target those who are most vulnerable to unemployment. As a result, the majority of the study graduates were black (96%) or Coloured (2.9%). The majority of the sample was female (64.6%). This is a feature of over-representation of females in the programmes, rather than an indication that females are more likely to pursue formal education after secondary school.

The fact that these young people managed to complete post-secondary studies is remarkable given that most of them were living in very vulnerable households. What follows is a description of the average type of household the participants originate from.

Household profile

Participants typically came from households with a low average per capita household income of just R695 per month, placing them below the upper bound poverty line of South Africa (Statistics South Africa Citation2017). Households spent on average 61% of the average monthly household income on groceries, confirming that they are poor households. Previous research has shown that poor households spend a substantially larger proportion of their monthly income on food compared to wealthy households (de Wet et al. Citation2008).

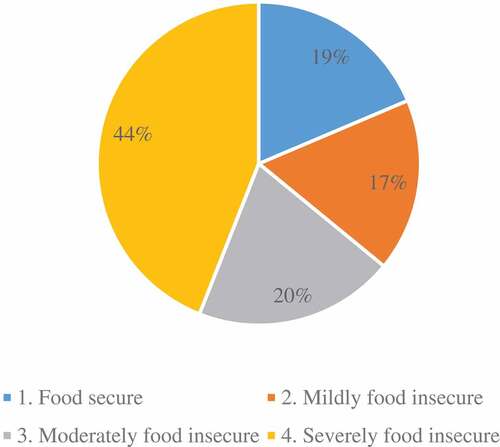

Despite this expenditure, the households the graduates come from are typically food insecure. Using the Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (Coates, Swindale, and Bilinksy Citation2007), we ascertained that the majority of graduates (64%) lived in households that experienced food insecurity, ranging from moderate to severe levels as is shown in . Severe food insecurity means that the graduate or another adult household member had gone to bed without a meal more than once in the month that preceded the study.

In addition, graduates lived in households that had experienced on average three household shocks in the 12 months prior to the study. These included severe shocks, such as illness or death of a household member or loss of household income. These kinds of shocks have detrimental impacts on the financial resources of these households, which are characterised by limited income and asset ownership.

Financial poverty among graduates is to an extent offset by access to basic services; however, gaps persist in the delivery of water and sanitation services to these households. Most graduates lived in formal housing and had access to electricity. Although most had access to piped water inside their dwelling (51%) or on-site (21.5%), about a fifth (21.3%) accessed water at a public or communal tap. Almost half of the graduates (49.0%) used a flush toilet inside the house, while over a quarter (28.8%) had to use a flush toilet outside the house.

The above analysis demonstrates that these graduates come from mainly low-income, food insecure households. They have managed to attain a post-secondary qualification within a national context where only a small proportion (14%) of matriculants ultimately qualify for university (Spaull Citation2015) and, where participation rates in further and higher education are low and racialised (Statistics South Africa Citation2016), and where completion rates at universities and technical vocational and education training (TVET) colleges are generally very low (Branson and Hofmeyr Citation2015). Given these factors, these graduates are remarkable in their resilience to complete a post-secondary qualification.

Experiences of employment and unemployment

Despite their achievements in the face of such vulnerability, the graduates continued to face unemployment. The average length of time that the graduates in the sample were unemployed for was 12.8 months, indicating that many of them were facing chronic unemployment (defined as unemployment for 12 months or longer). They were therefore not giving up on employment to participate in the programme, but rather participating in the programme because they were unemployed.

Their unemployment status is despite a large proportion of graduates (60%) having prior work experience. These graduates had an average of two previous jobs. In terms of previous work, graduates mainly gained work experience in the sales sector (31%). About a fifth gained experience as technical or skilled workers and service workers, respectively.

The average net pay earned in their previous job was R2 518 per month. The average wage reported was slightly higher than the national average of R2 166 per month for black youth aged 18–24 years with a matric as reported in the Quarterly Labour Force Survey quarter 1 of 2016Footnote2 (Statistics South Africa Citation2016b). Previous jobs were typically formal, as evidenced by a signed contract in 59% of the cases, and mainly short term in nature. The mean duration of a job was 11.2 months. The case of Mpendulo demonstrates the short-term nature of jobs. He was self-employed as a plumber at the time of the follow-up interviews, but prior to this had been employed in several different positions ranging from being a driver, a call centre operator, and a field worker. Similarly, Blessing notes this about her previous work experience:

‘But I have had a few jobs which were short-term jobs that did not last long.’

The findings on employment demonstrate that these graduates experience unemployment despite their education levels and the fact that they have work experience. What then are the other barriers to the labour market that they experience?

Barriers to the labour market during work-seeking

Graduate unemployment status was not as a result of lack of work search activity on their part. Job search activity was high with the majority of graduates (86%) having engaged in work seeking in the three months prior to joining the programme. During this time, these work-seekers had applied for an average of 12 jobs (or four jobs per month). The findings show that there are four key barriers that limit the ability of these young graduates to find work despite their profile and their job search activity: lack of relevant work experience, lack of information about how to look for work, limited social capital, and the high costs of work-seeking. The latter three can be attributed to their socio-economic backgrounds.

Lack of relevant work experience

As discussed above, a large proportion of the unemployed graduates in the survey sample had prior work experience. This work experience was typically short term in nature and not necessarily relevant to the jobs that they were looking for after completing their training. The in-depth interview participants noted this as a critical barrier for them, explaining that the majority of the jobs they wanted to apply for required a certain number of years of experience.

‘It’s complicated to get a job if you do not have experience even if you have a degree whether it is a master’s degree. There are many of my friends that I know who have degrees but are unemployed because of lack of experience.’ (Mandla)

‘I think that the prospects are very low because companies want experience which graduates don’t have.’ (Thabisa)

The interviewees were also adept at explaining that there was a difference between having a qualification and having the requisite skills for a job. In their understanding, skills were derived from practical experience and not having this experience meant that they did not have the skills required.

‘There is a competition between graduates and people with skills because most of graduates are academics without skills, while companies always search for people with experience. I think that is the challenge graduates face.’ (Amahle)

‘Basically what the universities are doing, they are giving the students the theoretical side of things, whereas when it comes to companies, they want people with experience such experience that the person will just enter into the job post and be able to do what’s required of them.’ (Siyabonga)

Limited experience is certainly a feature of youth unemployment globally (International Labour Organisation (ILO) Citation2015) and explains why youth unemployment levels are higher than adult unemployment levels. However, youth typically age into the labour market as they build up experience. Limited work experience is thus an issue that potentially affects all graduates. But these graduates face additional barriers in the labour market, including the fact that they have limited information about work search and job application processes, which are tied to their socio-economic profile.

Limited information

A key barrier to the labour market is that the graduates typically had limited information about how best to look for work. They attributed this largely to the areas in which they live, where information poverty was a reality.

‘Some of us will be coming from bad backgrounds and you don’t even know anything, most people here don’t even know about the internet. So, you don’t know even where to start when looking for a job or certain things.’ (Blessing)

As a result, they typically use inefficient job search mechanisms. They mainly apply for jobs that are widely advertised on the Internet (70%) or in newspapers (44%) as is explained by interview participants in response to a question about what strategies they have used to look for work.

‘I posted my CVs online (you know) but unfortunately, I didn’t get a job.’ (Mandla)

‘I am searching through Internet. I am also looking at the newspaper.’ (Lerato)

‘I do online, my brother works so he sends my applications from his office, using the Internet there.’ (Mpendulo)

In addition to the high data expenses that they incur, this strategy likely means that they are competing with a large pool of candidates for the same jobs. Far fewer graduates used more effective jobs search strategies, such as consulting their social networks (27%) or applying through employment agencies (22%) when searching for jobs – strategies that are more frequently used by graduates from a wealthier background (Rogan et al. Citation2015). Further, they were typically using limited kinds of work-seeking strategies. On average they used only two job search strategies suggesting that they were not diversifying their work-search efforts. This may be because they lack information about how best to apply for work and general information poverty that they experienced growing up as was described by Blessing above.

The limited information they experience extends to worries and concerns about how to prepare for job interviews if one is a successful applicant.

‘I remember one of my friends who is a graduate, she was called for an interview and she had no idea of what to expect, the questions they might ask or how she must answer or how to present herself.’ (Amahle)

Lack of information is compounded by the fact that most graduates had few people within their social network that they could turn to for advice and support on employment. Limited social capital, therefore, emerges as an additional barrier.

Limited social capital

In South Africa, there is evidence to show that social capital is a critical resource for finding work (Altman Citation2007; Mhlatseni and Rosbape Citation2009; Kraak Citation2010; Rogan et al. Citation2015). Bonding social networks are theorised to play an important role in emotional support but are usually not particularly productive for making connections to work opportunities. Bridging social capital – defined as networks of acquaintances that connect the individual with people outside of their bonding networks – are usually viewed as being more productive in terms of accessing opportunities (Putnam Citation2001).

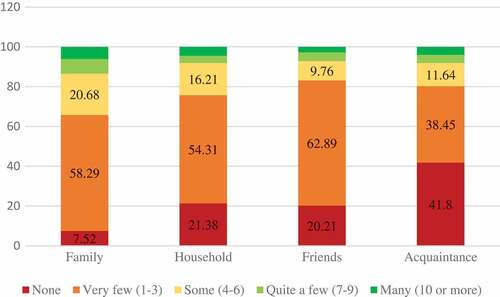

shows that graduates in this study reported high levels of bonding social capital with more than half reporting that they had on average three people that they could consult in the household or among family or friends. They reported relying predominantly on these networks for advice and support when searching for jobs and other opportunities as is reflected in this quote from Blessing when she responded to a question about how she was looking for work.

‘I am spreading the word through family and friends that if they hear anything, they let me know,’ (Blessing)

While the participants had strong bonding social networks, they had very limited bridging social capital. Four in every 10 graduates (42%) did not know any acquaintances that they could consult regarding work or other opportunities and a further 37.6% of participants had very few acquaintances.

The graduates who were interviewed were very aware that social networks were the way to find work and that most people found jobs through people they knew, and they expressed disillusionment with being outside of these networks of patronage, which some saw as blatant nepotism.

‘They still hire through nepotism and all those things, yes, nepotism, that’s the word, yes … They failing because of nepotism, people working on labour brokers are referring the opportunity to their family and that is how they are failing.’ (Dumisani)

‘Most of graduates do get jobs but not most of the time because people get jobs by knowing someone.’ (Lerato)

‘I would see the adverts in the newspapers like the Daily Dispatch and know that even if I apply I might not get the job, but I keep on applying. You apply but you find that every department has nepotism. You would go to an interview but they already have someone for that job.’ (Zodwa)

A lack of bridging social networks that include people who are employed therefore emerges as a clear barrier to finding work opportunities. This experience stands in stark contrast to wealthier graduates who typically find work quickly through their parents’ social networks (Seekings Citation2012)

Costs of work-seeking

A further barrier to employment is the immense cost of work-seeking. Recall that the average per capita household income for the sample was R676 per month. Yet, graduates reported spending on average of R616 per month on transport to look for work. In addition, graduates spent an average of R446 per month on application fees, printing, copying, data bundles, scanning and agents’ fees, bringing the total average monthly cost of job search to R1 062.

This was a theme that emerged consistently across the interviews:

‘Yes, financial challenges in the case of going to drop my CV so I have been asking my mum even my husband (family and friends) to drop my CV for me on my behalf on their way to work to save on costs, rather than me taking a taxi and going to drop my CV.’ (Blessing)

Challenge number one money, money, money.’ (Siyabonga)

‘What’s challenging is that when I need to go to point A to B for marketing and stuff like that, it is costing me because I need to get to that place. For example, if I need to get to Joburg, I need finances from my pocket.’ (Dumisani)

‘From July to December, I tried applying for schools and work but unfortunately at this point I had ran out of money.’ (Hlengiwe)

‘I had financial problems, like when I had to travel long distances it was difficult for me, at times I couldn’t afford money to go type my CVs.’ (Nelisiwe)

The survey data show that job search costs exceed the average per capita household income of graduates and, on average, over a third of household income is potentially contributed to such costs. It also emerged in the interviews as a critical barrier. Job search is thus potentially a poverty exacerbating process and significantly constrains these graduates’ ability to access the labour market.

Discussion

Consistent with the literature on who is most vulnerable to unemployment in South Africa, unemployed graduates in this study were mainly black African, younger, from poor socio-economic backgrounds and graduated with a certificate or diploma. In addition to post-secondary qualifications, most of them had work experience and had participated in various training programmes. These are all factors that should improve their employability and their chances of finding employment. Despite this, they remain unemployed, often chronically unemployed; and, the pathway to employment for this group is staggered and protracted – representing a loss on investments in their education for themselves, their households and the state.

The findings presented above demonstrate that although many faced chronic unemployment, the unemployment state is not a static one. Rather, these graduates face periods of searching for jobs, despite exorbitant costs, participating in multiple training programmes, and moving into and out of employment that is mainly temporary in nature, all in an attempt to improve their employability. These processes all offer opportunities to provide support that can enable such graduates to transition more smoothly to longer-term work.

The findings presented above demonstrate that despite positive education outcomes, and securing some work experience, graduates from poor backgrounds face additional challenges when attempting to secure work. These challenges are directly related to their community and household socio-economic contexts and give rise to recommendations for interventions that can better support these young people.

In the first instance, they felt that their training did not adequately prepare them for the workplace in that it left them without practical experience and relatedly, practical skills that are required in the workplace. Most explained that work experience was a key to the labour market door. While most had some form of work experience, it was not always in the relevant field. Their concerns point to the need for training that provides some practical experience. Current research in South Africa, for instance, shows the value of work-integrated learning options in assisting young people to secure work (Kruss et al. Citation2012; Jonck Citation2014). While such training options are not always viable, short-term job placements and volunteering in relevant fields are critical options for improving employment outcomes of graduates, particularly those who face additional household and community level barriers to the labour market.

A community and household level barrier that this group of graduates faced was a lack of information about how best to search for work. They typically used limited work search strategies, and the strategies they did use were those with the least chance of success. Limited social capital emerges as a further constraint to securing employment. As mentioned above, access to productive social capital is key to securing work in South Africa as has been evidenced by multiple studies. The fact that these graduates come from homes where they have limited bridging social capital limits their ability to find work and to access information about finding work. Costs of work-seeking emerge as a fourth crucial barrier to looking for and securing work. In fact, at the rates reported, work-seeking can become a poverty exacerbating process that moves young people into debt. These are barriers that can easily and affordably be addressed through investments in locally accessible and youth-friendly work-seeker support interventions.

In South Africa, investment in work-seeker support is very low when compared to countries like Brazil (Bhorat Citation2012). Aiding young people generally, and graduates in particular, with work-seeker support, which includes advice on how best to look for work, how to complete one’s CV, and how to put together a job search strategy and commitment is, therefore, a critical emerging recommendation. Recent research demonstrates that such support offered at Labour Centres in South Africa is showing positive returns (Burger Citation2016; Abel, Burger, and Piraino Citation2017). Similar initiatives at university or in easily accessible community settings are therefore crucial to addressing information barriers to the labour market for graduates who face the above mentioned household and community level barriers. Such initiatives can also stand in for the lack of social capital that these young people face. In the absence of information and contacts through social networks, employment support programmes offer opportunities to provide such information and referral networks. They also reduce the costs of work-seeking for young people. If graduates are able to easily access community or university and college resources to search for work, this limits the travel and data cost burden that they currently carry.

Youth employability programmes, such as those through which the graduates in this study were recruited, also offer important connection points to support young people as they transition to work (Dieltiens Citation2015; Graham et al. Citation2016). Many such organisations provide the kind of work-seeker support recommended above, as well as technical skills training. Certain organisations also make deliberate attempts to connect young people with employers through work placements. These initiatives have the potential to expose young people to the much-needed bridging social capital that could unlock labour market opportunities.

Conclusion

Graduate unemployment levels are low in South Africa when compared to overall and youth unemployment in the country, as well as graduate unemployment rates in other developing contexts. However, there are still groups of young graduates that continue to struggle to find work. While previous literature has concentrated on the demographic and educational profiles of unemployed graduates, this article contributes insight into what some of the community and household level barriers to the labour market are. It shows that the journey to work is not a smooth one for this group of graduates from poor backgrounds. Rather, it is staggered with graduates gaining some work experience in relatively low paying jobs, engaging in additional training programmes, and periods of unemployment with intensive work search activity. Their situation is not for lack of effort, but rather points to the fact that not all graduates exit university or college with the same suite of tools to find work as others. The graduates in this study, all from poor economic backgrounds, had limited information about how to find work, lacked bridging social capital they could leverage for access to work opportunities, and faced very high costs of work-seeking relative to their household income. All of these issues are relatively easy to address through university, college or community-based work-seeker support interventions. Investments in work-seeker support for vulnerable graduates emerge as a critical recommendation if investments by the state and the individual graduates and his or her family are to be realised.

The article has shown that graduates are not a homogenous group. Rather, they come from diverse backgrounds with some having fewer opportunities. Nevertheless, they demonstrate remarkable resilience and agency in having completed post-secondary education, secured work experience, and continued to search for work or better their profile through additional training. Yet, the system fails them by providing inadequate work-seeker support. Such support is crucial if we are to address not only their needs but those of the millions of young people that remain unemployed.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Lauren Graham

Lauren Graham is a Development Sociologist with an interest in young people’s transitions to adulthood and specifically to the labour market.

Leilanie Williams

Leilanie Williams holds a Masters in Community Psychology and has a research interest in interventions to support vulnerable youth.

Charity Chisoro

Charity Chisoro holds a Masters degree in Social Impact Assessment and is interested in transitions to the labour market for graduates.

Notes

1. In South Africa, under apartheid, places of education were racially segregated with universities serving Black and Coloured students receiving considerably lower government funding than those serving primarily White students. Although the racial segregation ended with apartheid, the consequences of this model have left inequalities in the institutions in terms of prestige and the ability to attract funding.

2. This quarter was the closest quarter to the data collection point.

References

- Abel, M., R. Burger, and P. Piraino. 2017. “The Value of Reference Letters.” Working Paper. http://localhost:8080/handle/11090/882

- Africa, Statistics South. 2016. Education Series Volume III: Education Enrolment and Achievement. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa, http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/Report%2092-01-03/Report%2092-01-032016.pdf

- Altman, M. 2007. Youth Labour Market Challenges in South Africa. Pretoria: HSRC.

- Bai, L. 2006. “Graduate Unemployment: Dilemmas and Challenges in China’s Move to Mass Higher Education.” The China Quarterly 185: 128–144. doi:10.1017/S0305741006000087.

- Baldry, K. 2016. “Graduate Unemployment in South Africa: Social Inequality Reproduced.” Journal of Education and Work 29 (7): 788–812. doi:10.1080/13639080.2015.1066928.

- Banerjee, A., S. Galiani, J. Levinsohn, Z. McLaren, and I. Woolard. 2007. “Why Has Unemployment Risen in the New South Africa.” Working Paper 13167. National Bureau of Economic Research. http://www.nber.org/papers/w13167

- Bhorat, H., N. Mayet, and M. Visser. 2010. “Student Graduation, Labour Market Destinations and Employment Earnings.” In Student Retention & Graduate Destination: Higher Education & Labour Market Access & Success, edited by M. Letseka, M. Cosser, and M. Breir, 97–124. Cape Town: HSRC Press.

- Bhorat, H. 2012. A Nation in Search of Jobs: Six Possible Policy Suggestions for Employment Creation in South Africa. DPRU Working Paper Series No 12/150. Cape Town: Development Policy Research Unit, University of Cape Town.

- Branson, N., Hofmeyr, C., Papier, J. and Needham, S. 2015. “Post-School Education: Broadening Alternative Pathways from School to Work.” In The South African Child Gauage 2015, edited by A. De Lannoy, S. Swartz, L. Lake, and C. Smith, 42–50. Cape Town: Children’s Institute.

- Broecke, S. 2013. “Tackling Graduate Unemployment in North Africa through Employment Subsidies: A Look at the SIVP Programme in Tunisia.” IZA Journal of Labor Policy 2 (July): 9. doi:10.1186/2193-9004-2-9.

- Burger, R. 2016. “The Role of Reference Letters in Finding First Time Employment for Youth.” Panel presentation presented at the Accelerating Inclusive Youth Employment Conference, Stellenbosch, September 26.

- (CHEC) Cape Higher Education Consortium. 2013. Pathways from University to Work: A Graduate Destination Survey of 2010 Cohort of Graduates from the Western Cape Universities. Cape Town: CHEC.

- Carnevale, A. P., and B. Cheah. 2015. “From Hard Times to Better Times: College Majors, Unemployment, and Earnings.” Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED558169

- Coates, J., A. Swindale, and P. Bilinksy. 2007. “Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for Measurement of Food Access: Indicator Guide.” Version 3. Washington, DC: Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project, Academy for Education Development.

- Cosser, M. 2003. “Graduate Tracer Study.” In Technical College Responsiveness: Learner Destinations and Labour Market Environments in South Africa, edited by M. Cosser, S. McGrath, and A. Badroodien, 27–56. Cape Town: HSRC Press.

- de Wet, T., L. Patel, M. Korth, and C. Forrester. 2008. Johannesburt Poverty and Livelihoods Study. CSDA Monograph. Johannesburg: Centre for Social Development in Africa, University of Johannesburg.

- Development Policy Research Unit. 2017. “Monitoring the Performance of the South African Labour Market: An Overview of the South African Labour Market for the Year Ending 2016.” Monitoring report. Employment Promotion Programme. Cape Town: Development Policy Research Unit, University of Cape Town.

- Dieltiens, V. 2015. “A Foot in the Door: Are NGOs Effective as Workplace Intermediaries in the Youth Labour Market?” Econ 3×3 (blog). http://www.econ3x3.org/article/foot-door-are-ngos-effective-workplace-intermediaries-youth-labour-market

- Graham, L., L. Patel, G. Chowa, R. Masa, Z. Khan, L. Williams, and S. Mthembu. 2016. “Youth Assets for Employability: An Evaluation of Youth Employability Interventions (Baseline Report).” Research Report. Siyakha Youth Assets. Johannesburg: Centre for Social Development in Africa, University of Johannesburg.

- International Labour Organisation (ILO). 2015. “Global Trends in Youth Employment.” http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—dcomm/—publ/documents/publication/wcms_412015.pdf

- Isdale, K., V. Reddy, L. Winnaar, and T. Zuze. 2016. “Smooth, Staggered or Stopped? Educational Transitions in the South African Youth Panel Study.” http://www.lmip.org.za/document/smooth-staggered-or-stopped-educational-transitions-south-african-youth-panel-study-0

- Jonck, P. 2014. “The Mitigating Effect of Work-Integrated Learning on Graduate Employment in South Africa.” Africa Education Review 11 (July): 277–291. doi:10.1080/18146627.2014.934988.

- Joshua, S., I. Biao, D. Azuh, and F. Olanrewaju. 2015. “Multi-Faceted Training and Employment Approaches as Panacea to Higher Education Graduate Unemployment in Nigeria.” Contemporary Journal of African Studies 3 (1): 1–15.

- Kraak, A. 2010. “The Collapse of the Graduate Labour Market in South Africa: Evidence from Recent Studies.” Research in Post-Compulsory Education 15: 81–102. doi:10.1080/13596740903565384.

- Kruss, G., A. Wildschut, D. J. van Rensburg, M. Visser, G. Haupt, and J. Roodt. 2012. “Developing Skills and Capabilities through the Learnership and Apprenticeship Pathway Systems.” HSRC DPRU Department of Labour.

- Li, S., J. Whalley, and C. Xing. 2014. “China’s Higher Education Expansion and Unemployment of College Graduates.” China Economic Review 30 (September): 567–582. doi:10.1016/j.chieco.2013.08.002.

- Livanos, I. 2010. “The Relationship between Higher Education and Labour Market in Greece: The Weakest Link?” Higher Education 60 (5): 473–489. doi:10.1007/s10734-010-9310-1.

- Mhlatseni, C., and S. Rosbape. 2009. “Whi Is Youth Unemployment so High and Unequally Spread in South Afica?” Development Policy Research Unit. http://hdl.handle.net/123456789/7553

- Mncayi, P., and S. H. Dunga. 2016. “Career Choice and Unemployment Length, Career Choice and Unemployment Length: A Study of Graduates from A South African University, A Study of Graduates from A South African University.” Industry and Higher Education 30 (6): 413–423. doi:10.1177/0950422216670500.

- Mogomotsi, G. E. J., and P. K. Madigele. 2017. “A Cursory Discussion of Policy Alternatives for Addressing Youth Unemployment in Botswana.” Cogent Social Sciences Edited by John Martyn Chamberlain 3 (1): 1356619. doi:10.1080/23311886.2017.1356619.

- Mok, K. H. 2016. “Massification of Higher Education, Graduate Employment and Social Mobility in the Greater China Region.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 37 (1): 51–71. https://0-doi-org.ujlink.uj.ac.za/10.1080/01425692.2015.1111751

- Mok, K. H., and D. Neubauer. 2016. “Higher Education Governance in Crisis: A Critical Reflection on the Massification of Higher Education, Graduate Employment and Social Mobility.” Journal of Education and Work 29 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1080/13639080.2015.1049023.

- Moleke, P. 2005. Inequalities in Higher Education and the Structure of the Labour Market. Cape Town: HSRC Press.

- Oluwajodu, F., D. Blaauw, L. Greyling, and P. J. K. Ewert. 2015. “Graduate Unemployment in South Africa : Perspectives from the Banking Sector : Original Research.” SA Journal of Human Resource Management 13: 1–9. doi:10.4102/sajhrm.v13i1.656.

- Pauw, K., H. Bhorat, S. Goga, L. Mncube, M. Oosthuizen, and V. D. W. Carlene 2006. “Graduate Unemployment in the Context of Skills Shortages, Education and Training: Findings from a Firm Survey.” Education and Training: Findings from a Firm Survey (November 2006). DPRU Working Paper.

- Pauw, K., M. Oosthuizen, and C. Van Der Westhuizen. 2008. “Graduate Unemployment in the Face of Skills Shortages: A Labour Market Paradox1.” South African Journal of Economics 76 (1): 45–57. doi:10.1111/j.1813-6982.2008.00152.x.

- Perold, H., N. Cloete, and J. Papier, eds. 2012. Shaping the Future of South Africa’s Youth: Rethinking Post-School Education and Skills Training in South Africa. Wynberg: Centre for Higher Education and Transformation.

- Putnam, R. D. 2001. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. 1st ed. New York: Touchstone Books by Simon & Schuster.

- Reddy, V. 2016. “Skills Supply & Demand for South Africa.” Accept AE: Labour Market Intelligence Partnership (LMIP).

- Rogan, M., J. Reynolds, U. Du Plessis, R. Bally, and K. Whitfield. 2015. “Pathways through University and into the Labour Market Report on a Graduate Tracer Study from the Eastern Cape.” LMIP REPORT 18. Labour Market Intelligence Partnership (LMIP).

- Samaranayake, G. 2016. “Expansion of University Education, Graduate Unemployment and the Knowledge Hub in Sri Lanka.” Social Affairs: A Journal for the Social Sciences 1 (4): 15–32.

- Seekings, J. 2012. “Young People’s Entry into the Labour Market in South Africa.” Presented at the Strategies to Overcome Poverty and Inequality: Towards Carnegie III Conference, Cape Town: University of Cape Town, September 3–7.

- Seekings, J., and N. Nattrass. 2005. Class, Race, and Inequality in South Africa. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- South African Labour & Development Research Unit (SALDRU). 2016. “Wave 4 Overview: National Income Dynamics Study 2008-2016.” Research Summary Report. Cape Town: NIDS.

- Spaull, N. 2013. South Africa’s Education Crisis: The Quality of Education in South Africa, 1994-2011. Johannesburg: Centre for Development and Enterprise.

- Spaull, N. 2015. “Schooling in South Africa: How Low Quality Education Becomes a Poverty Trap.” In The South African Child Gauge 2015, edited by A. de Lannoy, S. Swartz, L. Lake, and C. Smith, 34–41. Cape Town: Children’s Institute.

- Statistics South Africa. 2015. General Household Survey 2015. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa.

- Statistics South Africa. 2016a. Education Series Volume III: Education Enrolment and Achievement. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa.

- Statistics South Africa. 2016b. “Quarterly Labour Force Survey: Quarter 1 2016.” Statistical Release P0211. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa. http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0211/P02111stQuarter2016.pdf

- Statistics South Africa. 2017. “Poverty Trends in South Africa: An Examination of Absolute Poverty between 2006 and 2015.” Statitistical report 03-10–06. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa. https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/Report-03-10-06/Report-03-10-062015.pdf

- Statistics South Africa. 2018. “Quarterly Labour Force Survey: Quarter 2 2018.” Statistical Release P0211. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa. http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0211/P02112ndQuarter2018.pdf

- Stewart, V. 2015. Made in China-Challenge and Innovation in China’s Vocational Education and Training System. Washington, DC: National Center on Education and the Economy. http://ncee.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/CHINAVETFINAL1.pdf

- van Broekhuizen, H., and S. V. D. Berg. 2016. “How High Is Graduate Unemployment in South Africa? A Much-Needed Update.” Econ 3×3 (blog). http://www.econ3x3.org/article/how-high-graduate-unemployment-south-africa-much-needed-update

- Van der Berg, S., and V. B. Hendrik 2012. “Graduate Unemployment in South Africa: A Much Exaggerated Problem.” Working Paper 22/2012. Stellenbosch University, Department of Economics. https://ideas.repec.org/p/sza/wpaper/wpapers175.html

- Van Rheede, T. J. 2012. “Graduate Unemployment in South Africa: Extent, Nature and Causes.” Thesis, University of the Western Cape. http://etd.uwc.ac.za/xmlui/handle/11394/4497

- Weybright, E. H., L. L. Caldwell, H. (Jimmy) Xie, L. Wegner, and E. A. Smith. 2017. “Predicting Secondary School Dropout among South African Adolescents: A Survival Analysis Approach.” South African Journal of Education 37 (2): 1–11. doi:10.15700/saje.v37n2a1353.

- Wu, C.-C. 2011. “High Graduate Unemployment Rate and Taiwanese Undergraduate Education.” International Journal of Educational Development 31 (3): 303–310. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2010.06.010.