ABSTRACT

This paper considers the position of Further Education (FE) in the light of the analysis undertaken by Geoff Mason (this issue). It argues that despite great optimism as to the potential of FE to raise productivity and enhance social mobility this has not been achieved due to underfunding and the current system of governance. Without bold moves in both the funding and governance of FE, the sector is likely to languish.

Invoking the importance of her own time at a college, former Conservative education minister Justine Greening (Citation2020, 23) wrote in response to the current Covid-19 crisis that the Further Education (FE) sector:

has a pivotal role to play for this country over the next two years. It must be allowed to respond to demands from existing students and those arriving into the system – and it must be able to help hundreds of thousands of people to reskill.

In a similar tone, David Goodhart (Citation2020) produced a paper subtitled How the Covid-19 response can help sort out Britain’s training mess proposing that FE colleges receive ‘a badly needed injection of cash, and national purpose’ to provide new vocational courses (Goodhart Citation2020, 11). The Covid-19 crisis may be focusing minds on FE but long before the current predicament similar demands for FE to address national social and economic priorities have been common from across the political spectrum. They often use remarkably similar language, too. In 2005, for example, Bill Rammell, the Labour minister of state for Higher Education and Lifelong Learning asserted (LSC (Learning and Skills Council) Citation2005, 1) that ‘Further Education is the engine room for skills and social justice in this country’. Six years later writing for the right-of-centre think tank Policy Exchange, Hartley and Groves (Citation2011, 6) claimed that FE colleges could be, ‘An engine for widening participation and social mobility’. The writers of the current Conservative government’s Independent panel report to the Review of Post-18 Education and Funding, known as the Augar Review, had a vision that FE colleges would ‘maintain strong relationships with employers and act as engines of social mobility and inclusion’ (Augar Citation2019, 138). Despite these high expectations, the metaphors have changed as little as the overall weak position of FE. In this article I describe the current state of FE and how its tenacious capacity to cope has left it ill-prepared to address the nation’s social and economic problems; and I examine whether the current combination of factors, including the Augar Review (2019) and a mooted reversal of incorporation and a return to public control of colleges, will mean fundamental transformation for FE. As the sector once again finds itself tasked with aiding economic development and social mobility, is it really different this time for FE?

The FE system in the UK evolved from similar origins but colleges in the four home nations are now following different paths. This paper concentrates on FE colleges in England which are attended by 2.2 million students. Among the total of 244 colleges in the FE sector (including sixth-form and specialist colleges) the largest proportion of students are studying at 168 General FE (GFE) colleges. These colleges are characterised by very diverse curricula including many academic courses but they mainly offer vocational programmes. The mission of an average FE college is far wider than that of a school or university and consequently, that mission is harder to define and to defend. Stanton et al. (Citation2015, 69) commented ‘that it is the very diversity of the FE curriculum offer that simplifies the life of school sixth forms and universities by enabling them to keep their more focused missions’. Nevertheless, 34% of English 16–18 year-olds are at FE and Sixth Form Colleges, compared with 24% at state-funded schools and 1.4 million adults attend courses in FE colleges (all figures from AoC Citation2020). The FE sector may have been repeatedly overlooked by ministers in the past but it is a very significant element of mainstream education in England.

Despite its size and importance, the FE system in England has become an exemplar of policy failure (see Norris and Adam Citation2017, 3). Since the early 1980s, there have been 28 major pieces of legislation that affected the FE sector and there have been over 50 secretaries of state with responsibility for FE (ibid., 5). As each reform failed to deliver all that it promised, so another was laid on top of the remains of the previous one leading to a further need for centralised intervention as that new one, too, failed to deliver (Fletcher, Gravatt, and Sherlock Citation2015, 172). The Institute for Fiscal Studies has described a ‘near-permanent state of revolution’ in the English FE sector (Belfield, Farquharson, and Sibieta Citation2018, 38). This pattern of policy churn is set to continue as the publication of a new White Paper has been announced for later this year, which, it has been reported, will propose taking colleges back into some kind of regional ‘public ownership’ almost 30 years since the incorporation of colleges removed them from the control of local authorities (Linford Citation2020, 6). No doubt, this White Paper will once again emphasise the enormous but latent potential that the FE sector has to aid economic development and promote social mobility. These are familiar tropes in policy for FE in England. Applying another persistent metaphor, the ‘technical side of education’ has been referred to as Cinderella since at least 1935 (Petrie Citation2015, 2), again most recently in the Augar Review (2019, p5). That is a very long time to wait for a prince to arrive to save the sector. Meanwhile, as discussed below, FE remains chronically underfunded and vulnerable to the caprice of policy. This weakness reflects its position and perception within society, which Hodgson and Spours (2015, p205) expressed succinctly:

It is impossible … to understand the position of GFEs without taking

into consideration the dominance of academic over vocational education in the perception of politicians and the wider public. Broadly speaking, the middle classes do not send their children to GFEs and vocational education still struggles for recognition and esteem.

One consequence of this is that studying on three-year bachelor degrees at university has won recognition and esteem to become the conventional aspiration of school-leavers. At the same time, the numbers taking higher-level sub-bachelor degree (level 4 and 5) vocational courses such as Higher National Certificates (HNCs) or Higher National Diplomas (HNDS) at colleges have dropped. Enrolments on these levels 4 and 5 courses reduced by 63% between 2009–10 and 2016–17 (from around 510,000 to around 190,000) (Foster Citation2019, 3). A proportion of this reduction may be explained by the rapid expansion of Level 4 and 5 apprenticeships to over 50,000 since their introduction in 2006/7 (Foley Citation2020, 15). In contrast to the drop in HNCs and HNDs, however, enrolments on full bachelor degrees in England rose over the same period (HESA Citation2020).

In this Special Issue, Mason identifies two serious imbalances in the UK’s education and training system that are reflected in those figures and in what Hodgson and Spours described above. Firstly, Mason noted that public spending on initial education and training is heavily weighted in favour of HE over spending on FE and VET more generally; and secondly that public spending provides only weak support for continuing education and training compared to initial education and training for new entrants to the workforce. Transforming VET in England would mean addressing those imbalances in the FE sector, which will be hampered by the position and perception of FE as well as how the sector is currently funded. Fletcher et al (Citation2015, 163) noted that the ‘constant froth of reform has made it difficult to assess the movement of the underlying tides’ in the English FE sector. Beneath the froth, the reversal of incorporation might help to bring about the major improvement of the sector that has so frequently been predicted.

As noted above, incorporation in 1992–3 brought FE colleges in England out of the control of local government and granted them freedom away from the strictures of local councils. This was a form of privatisation resulting from a policy of marketising education that led to fierce competition between colleges for students (Lucas and Crowther Citation2016). Though much was made of this apparent new freedom for colleges, it was always constricted. Fletcher, Gravatt, and Sherlock (Citation2015, 170) concluded ‘that incorporation and the subsequent policy choices made by government have given colleges the freedom to fail but not the freedom to succeed’. Ruth Silver, a principal of a large London college during incorporation, had a similar evaluation. In a recent interview, she described the freedom that colleges gained through their removal from local government control as being like that of a provider for Marks and Spencer; ‘every product has to cost the same and look the same’ because central government still tightly controlled the sector, above all through how courses or students were financed. Consequently, the freedom that incorporation brought was, for Silver, ‘a myth’ (Staufenberg Citation2020, 21).

Silver’s account exemplifies how funding has been the lever most frequently pulled to enforce the implementation of policy in English FE since incorporation (Steer et al. Citation2007). Colleges have adapted to rapidly comply with government regulations that were implemented through operating levers associated with finance as well as inspection and audit. This consistent compliance with government policy is central to explaining why colleges have operated similarly across England despite their legal independence and despite their being little coherent national strategy for FE, at least since 2010 (Lucas and Crowther Citation2016, 592). This shared acquiescence to regulation also means they suffer from the same problems (Fletcher, Gravatt, and Sherlock Citation2015, 174), which then leads to the current suggestion that colleges should be returned to public ownership. Some large colleges have been forced into financial administration, with many others colleges struggling financially. As these problems become more widespread, the government is concerned at being unable to comprehensively intervene or to protect public money from mismanagement (Linford Citation2020, 6). So, now even the myth of independence may be removed from FE colleges.

If colleges were to return to public control, it would be a major reversal of policy for FE, which has been characterised since 1992 by the idea of a market in the sector, as well as in HE. That education market has led to the marginalisation of VET, especially at sub-bachelor degree level (level 4 and 5), despite the explicit intention of policy that competition would enhance that provision, which is mainly delivered in FE colleges. Among the ‘key market failures’ identified by Zaidi et al (Citation2019, 14) in their review of the Level 4–5 qualification and provider market for DfE, were weak ‘brand awareness’ of qualifications at that level and, partly in consequence, low demand for these courses from prospective students. Even the government’s own Augar Review recognised market failure. While describing the ‘important role’ competition has played in ‘creating choice for students’, Augar (2019, p8) makes the case that tertiary education ‘cannot be left entirely to market forces’ if it is to ‘deliver a full spectrum of social, economic and cultural benefits’. That is a substantial shift in the rhetoric, which if met by a similar shift in policy would be significant for colleges, but perhaps not as significant as an overhaul of their funding.

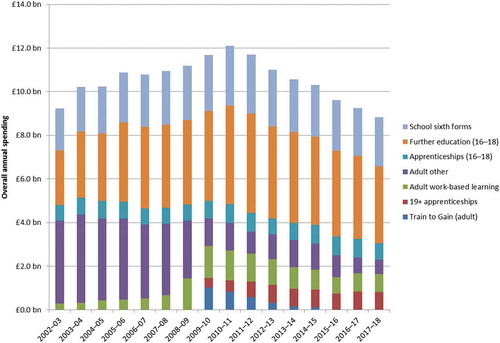

Figure 1. Total spending on further education and skills, 2002–03 to 2017–18 (acl consulting for DfE 2020: 22)

Though there may be poor financial management in some FE colleges, what is certain is that the sector as a whole is underfunded. shows how overall government spending on further education and skills, including but not limited to FE colleges, has been cut since 2010–11. Spending on the adult continuing education courses has been particularly squeezed, as Mason also highlighted. Total spending on adult education (excluding apprenticeships) fell by 47% between 2009–10 and 2018–19 (Britton, Farquharson, and Sibieta Citation2019, 60). A decade of annual cuts in overall spending has left the whole FE sector in 2018–19 with a smaller real terms income than it had in 2002–03 (Acl Consulting Citation2020, 22). In practical terms, this means that FE colleges cannot compete with industry employers on salaries for experienced engineers who may otherwise be interested in teaching. Colleges are currently struggling to recruit and retain teachers of technical subjects now, let alone being able to expand that provision at higher levels (Hanley and Orr Citation2019).

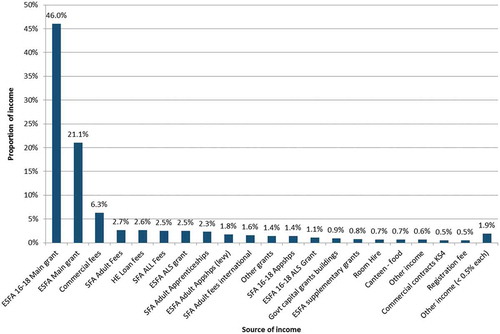

Not only has the funding of colleges been reduced, managing that funding is also complicated because it derives from so many different sources. shows the income of an anonymised FE college, which has 20 different income streams diminishing in size. As well as demonstrating the convoluted finances of a college, this figure indicates specifically how income for the higher-level continuing education that Mason emphasised comprises only a marginal element of overall income for this typical college. This complexity of funding necessitates a burdensome bureaucracy, which the Augar Review found impeded course development (Augar Citation2019, 126):

It is possible for one classroom to contain students studying the same qualification, who are funded in four different ways, with four different funding rates and four different criteria for funding. This materially affects the quality of the offer the college can make to students and employers, and the flexibility it has to put on new provision responding to demand.

Figure 2. Sources of income, percentages, a multi-site GFEC (Acl consulting Citation2020, 55)

This imbalance and complexity of funding are significant factors in the relegation of higher-level vocational education in FE, which is often more expensive to deliver (Augar Citation2019, 46). In 2018–19 only 2.25% of the certificates awarded in vocational subjects at all institutions in the English FE and skills sector were awarded at sub-bachelor degree level 4 or 5 (130,985 certificates out of a total of 5,815,045 at all levels) (Ofqual Citation2020). England’s proportion of these sub-bachelor or short-cycle higher education students on vocational courses is half that of Germany (Augar Citation2019, 35). The government’s 2017 Green Paper on industrial strategy identified this as a particular weakness for the UK.

We have a shortage of high-skilled technicians below graduate level. Reflecting the historic weakness of technical education in the UK, only 10% of adults hold technical education as their highest qualification, placing us 16th out of 20 OECD countries

(HM Government Citation2017, p38; original emphasis)

Yet, evidence for this shortage of technical skills among employers may be ambiguous. A report published by the former HE funding council for England (HEFCE) found evidence:

of considerable confusion in the marketplace as to what intermediate technical skills are, how they are of value in the current economy, and, perhaps most importantly, how they will be of value in the future.

Employers and stakeholders – but mainly the former – exhibit uncertainty as to what intermediate technical education is, and what its value is to them.

(Pye Tait Consulting/HEFCE 2016, p10)

Though skills shortages are frequently declared as an obstacle to economic development (for example, Augar Citation2019, p33), that kind of confusion among employers about the value of technical skills provides a weak incentive for FE colleges to expand their level 4 and 5 provision as the government and Augar wish. HNDs and HNCs have the best wage returns among vocational qualifications but these returns are still considerably less than for bachelor degrees (McIntosh and Morris Citation2016, 31). Individuals weighing up the costs and benefits of these courses may also, therefore, lack incentive to select them over degrees, especially while the costs of study are comparable (see Britton, Farquharson, and Sibieta Citation2019). Important to note, though, that there has been a rapid reduction of the average graduate premium in the UK, which may yet render shorter intermediate level qualifications like HNCs more attractive to individuals (HESA Citation2019).

Yet despite all these headwinds of policy churn and precarious funding, and despite their very broad mission, FE colleges in England continue to serve their students and their communities, successfully for the most part, as they have done for over a century. While discussing their weaknesses, the capacity of FE colleges to tenaciously provide courses that people want to take should not be disregarded and that capacity may also provide a route to expansion. FE colleges have endured their difficulties because they are ‘highly innovative and entrepreneurial’ (Keep Citation2016, 42), especially in how they adapt to provide what individual students wish to pursue. Yet this remarkable capacity of FE colleges to adapt is the flipside of their incapacity to determine or challenge the changes imposed on them (Orr Citation2018). Colleges are very good at absorbing change and coping with instability but, as Keep (2016, p42) argues, they are less ‘proficient at carving out their own visions, priorities and establishing the means to deliver these – either on their own or in partnership with others’. Having to adapt to frequent reform and cope with chronic underfunding has, paradoxically, left many English colleges in a state of stasis (Hodgson and Spours 2019, p230) and poorly prepared to expand to meet new demands. Arguably, that stasis has helped to prevent the sector from collapse during a period of intense instability, of course. The current concatenation of events may, however, be enough to overcome that stasis and improve the fortunes of FE. To summarise, those events are: the need to repair the economic and social effects of Covid-19; the recommendations of the Augar review specifically in relation to the unintended consequences of competition; and the concern of government to be able to intervene in colleges with failing finances through bringing colleges back into some form of public control.

In his article in this issue, Mason makes the case for abolishing tuition fees for all FE courses up to Level 5 as well as for community learning courses and other courses which do not necessarily lead to formal qualifications. This would address the two imbalances he identified in England’s VET system: that public spending on initial education and training favours HE over FE and VET; and that public spending on continuing education and training is weak compared to initial education and training for new entrants to the workforce. As noted above, the market to which FE colleges have always been most responsive is that driven by what individual students choose to study. Despite repeated calls for colleges to serve the needs of their particular local economies, the courses that colleges offer align most consistently with student demand not employer demand (Bailey and Unwin Citation2014, 457). Abolishing tuition fees would have the effect of making technical courses, such as HNCs and HNDs, more appealing to individuals and especially those already in work seeking to study part-time. Government needs to ensure that VET courses are more attractive to individuals than they currently are, especially in comparison to bachelor degrees. Augar recognises this problem, but the recommendation for ‘a single lifelong learning loan allowance for tuition loans at Levels 4, 5 and 6, available for adults aged 18 or over, without a publicly funded degree’ (Augar Citation2019, 40) does not address it. Offering loans has not proved to be attractive enough, which Mason identified in his analysis of the 2017 Adult Participation in Learning Survey (APLS). Take-up of formal loans to pay for fees among ALPS participants who were on courses ranged from 11% of students aged 25–34 to 3% of those aged 35–44, 4% of those aged 45–54 and 1% of those aged 55 or older. Mason’s recommendation to make higher level VET courses free would encourage more individuals to enrol and would consequently encourage the FE sector to develop these courses. Such a move would also strengthen the sector’s mission as distinctive from schools and from HE. Changing the mechanism for funding these courses alone will not alone transform FE, however.

The mooted reinstatement of public control of FE may entail more collaboration between colleges so they can strategically assert their own priorities as a more coherent sector. It may also enable what Hodgson and Spours have consistently described and supported: that FE colleges be ‘a strategic part of local and regional learning and skills systems’ that they refer to as High Progression and Skills Ecosystems (Hodgson and Spours 2019, p226 see also Hodgson and Spours Citation2015; Citation2016). This approach would enhance the role of FE colleges in leading VET within their regions, especially post-19 and at higher levels. In the current situation, colleges too often concentrate on tactics to cope, not a strategy for VET to thrive. Importantly, enhancing their strategic role for adult and continuing VET, if it is properly funded, does not mean abandoning colleges’ role in 16–19 education or their wider role in social inclusion.

The Augar review diagnosed many of the problems with the FE sector and above all, like Mason, how VET has been marginalised in an education market that favours HE. Properly managing the social and economic crisis caused by Covid-19 will require new approaches, so the current juncture could prove to be different from others and lead to lasting reform for the sector. Making VET and other courses free up to level 5 as Mason suggests would be politically bold as would bringing back public control of colleges at regional level but these moves are far from outlandish. The adult education budget for Greater Manchester has already been devolved to the Combined Authority, for instance. This government has recently driven through skills policy that it has favoured: the new technical qualifications for students aged 16–19 (T levels) have been hastily implemented by the government despite even a public warning from the most senior civil servant in the DfE (Slater Citation2018). Without bold moves FE will not thrive but, to be clear, it is also unlikely to collapse. The sector is currently like a limpet on a rock: it is resilient but it has no control over the tides that regularly threaten to wash it away. Resilience is admirable but it is not a strategy for the development of VET. Yet, the current crisis will mean a greater need in England for what FE provides. If there is political will and political understanding of how the sector is positioned and how it operates, then maybe the FE sector’s time really has come.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Acl Consulting. 2020. Costs and Cost Drivers in the Further Education Sector Research. London: DfE. report February 2020.

- AoC (Association of Colleges). 2020. “College Key Facts 2019-2020.” Accessed 22 June 2020. https://www.aoc.co.uk/sites/default/files/AoC%20College%20Key%20Facts%202019-20.pdf

- Augar, P. 2019. Independent Panel Report to the Review of Post-18 Education and Funding (Augar Review). London: HMSO.

- Bailey, B., and L. Unwin. 2014. “Continuity and Change in English Further Education: A Century of Voluntarism and Permissive Adaptability.” British Journal of Educational Studies 62 (4): 449–464. doi:10.1080/00071005.2014.968520.

- Belfield, C., C. Farquharson, and L. Sibieta. 2018. 2018 Annual Report on Education Spending in England. London: Institute for Fiscal studies. Accessed 15 June 2020. https://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/13306

- Britton, J., C. Farquharson, and L. Sibieta. 2019. 2019 Annual Report on Education Spending in England. London: Institute for Fiscal Studies. 15 June 2020. https://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/14369

- Fletcher, M., J. Gravatt, and D. Sherlock. 2015. “Levers of Power: Funding, Inspection and Performance Management.” In The Coming of Age for FE? Reflections on the past and Future Role of Further Education Colleges in the UK, edited by A. Hodgson, 155–177. London: IOE Press.

- Foley, N. 2020. “Apprenticeship Statistics. House of Commons Briefing Paper 06113.” 2 June 2020. https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/researchbriefings/sn06113/

- Foster, D. 2019. “Level 4 and 5 Education, House of Commons Briefing Paper Number 8732.” 2 June 2020. https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-8732/

- Goodhart, D. 2020. A Training Opportunity in the Crisis: How the Covid-19 Response Can Help Sort Out Britain’s Training Mess. London: Policy Exchange.

- Greening, J. 2020. FE Has a Pivotal Role over the Next Two Years (And There Is No Time to Lose). FE Week, Edition. 319: 5.

- Hanley, P., and K. Orr. 2019. “The Recruitment of VET Teachers and the Failure of Policy in England’s Further Education Sector.” Journal of Education and Work 32 (2): 103–114. doi:10.1080/13639080.2019.1617842.

- Hartley, R., and J. Groves. 2011. Vocational Value: The Role of Further Education Colleges in Higher Education. London: Policy Exchange.

- Higher Education Statistical Agency (HESA). 2019. “New Research Shows Reduction in the ‘Graduate Premium’.” 2 June 2020. https://www.hesa.ac.uk/news/22-10-2019/return-to-degree-research

- Higher Education Statistical Agency (HESA). 2020. “Where Do HE Students Come From?” 10 May 2020. https://www.hesa.ac.uk/data-and-analysis/students/where-from

- HM Government. 2017. “Building Our Industrial Strategy: Green Paper.” 23 March 2020. www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/611705/buildingour-industrial-strategy-green-paper.pdf

- Hodgson, A., and K. Spours. 2015. “The Future for FE Colleges in England: The Case for a New Post-Incorporation Model.” In The Coming of Age for FE? Reflections on the past and Future Role of Further Education Colleges in the UK, edited by A. Hodgson, 199–221. London: IOE Press.

- Hodgson, A., and K. Spours. 2016. The Evolution of Social Ecosystem Thinking: Its Relevance for Education, Economic Development and Localities A Stimulus Paper for the Ecosystem Seminar, the Centre for Post-14 Education and Work. London: UCL Institute of Education.

- Keep, E. 2016. The Long-term Implications of Devolution and Localism for FE in England. London: Association of Colleges.

- Linford, N. 2020. Government to Take Ownership of Colleges. FE Week, Edition..

- LSC (Learning and Skills Council). 2005. Learning and Skills- the Agenda for Change: The Prospectus. Coventry: LSC.

- Lucas, N., and N. Crowther. 2016. “The Logic of the Incorporation of Further Education Colleges in England 1993–2015: Towards an Understanding of Marketisation, Change and Instability.” Journal of Education Policy 31 (5): 583–597. doi:10.1080/02680939.2015.1137635.

- McIntosh, S., and D. Morris. 2016. Labour Market Returns to Vocational Qualifications in the Labour Force Survey: Research Discussion Paper 002. London: Centre for Vocational Educational Research.

- Norris, E., and R. Adam. 2017. All Change: Why Britain Is so Prone to Policy Reinvention, and What Can Be Done about It. London: Institute for Government.

- Ofqual. 2020. “Annual Qualifications Market Report Academic Year 2018 to 2019 (Table 13: Vocational & Other Qualifications - the Number of Certificates by Qualification Level for the past 5 Years).” 18 June 2020 https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/annual-qualifications-market-report-academic-year-2018-to-2019

- Orr, K. 2018. “FE Colleges in the United Kingdom: Providing Education for Other People’s ChildrenFE Colleges in the United Kingdom: Providing Education for Other People’s Children.” In Handbook of Comparative Studies on Community Colleges and Global Counterparts, edited by R. Latiner Raby and E. Valeau, 253–269, Springer International Handbooks of Education. Cham: Springer.

- Petrie, J. 2015. “Introduction: How Grimm Is FE?” In Further Education and the Twelve Dancing Princesses, edited by M. Daly, K. Orr, and J. Petrie, 1–12. London: IOE Press.

- Pye Tait Consulting. 2018. “Perceptions of Vocational and Technical Qualifications.” 20 June 2020. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attacment_data/file/743401/Perceptions_Survey_2018_-_FINAL_-_26_September_2018.pdf

- Slater, J. 2018. “T Levels: Ministerial Direction; Letters Requesting and Confirming a Ministerial Direction Relating to the Implementation of T Levels.” 18 June 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/t-levels-ministerial-direction

- Stanton, G., A. Morris, and J. Norrington. 2015. “What Goes on in Colleges? Curriculum and Qualifications.” In The Coming of Age of FE? Reflections on the past and Future Role of Further Education Colleges in the UK, edited by A. Hodgson, 68–88. London: IOE Press.

- Staufenberg, J. 2020. Incorporation: The End of an Experiment or the End of a Myth? FE Week, Edition.

- Steer, R., K. Spours, A. Hodgson, I. Finlay, F. Coffield, S. Edward, and M. Gregson. 2007. “Modernisation’ and the Role of Policy Levers in the Learning and Skills Sector.” Journal of Vocational Education & Training 59(2): 175–192.

- Zaidi, A., S. Beadle, and A. Hannah. 2019. “Review of the Level 4-5 Qualification and Provider Market: Research Report;” February 2019 DfE. 25 May 2020 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/782160/L4-5_market_study.pdf