ABSTRACT

Activation policies are widely adopted to encourage labour market participation of unemployed youth, and yet they are poorly understood and monitored with regard to the causal mechanisms unfolding through their implementation. Activation schemes are often based on the carrot-and-stick logic informed by microeconomic job search theory, but activation occurs through processes which are far more complex and comprises elements of career identity and capability development, among others. This paper is the first to provide an in-depth exploration of the processes of attitudinal and behavioural change experienced by unemployed youth over the course of their participation in different activation programmes. Seven phases of change emerged from the analysis, namely vocational availability, self-testing, self-knowledge, self-confidence, goal-orientation, vocational activity and perseverance. For each of these phases, we identify drivers of change from both within and outside the intervention sphere, and discuss them in their implications for research and practice.

1. Introduction

Youth unemployment hinders both economic development and social welfare. Not only are unemployed youth unable to actively contribute to the economy, but they are also less satisfied and healthy, as well as more prone to social isolation and delinquent behaviour than those following a vocational activity (Wanberg Citation2012; Kingston and Webster Citation2015; Andresen and Linning Citation2016). Being unemployed at a young age increases the risk of long-term unemployment, mental health problems in later life and intergenerational dependency on welfare programmes (Konle-Seidl and Eichhorst Citation2008; Bell and Blanchflower Citation2011).

Structural barriers for the labour market entry of youth include skills mismatch, the lack of entry-level positions, and economic recessions which are particularly harmful for less experienced workers as they have more precarious jobs and fewer opportunities to access the labour market (Bell and Blanchflower Citation2011). At the individual ‘supply side’ level, the main risk factors preventing youth from joining the formal work force range from problems with parents and at school to personal barriers such as homelessness and mental health issues. Repeated failure and rejection can cause a vicious cycle of decreasing motivation and passivity, leading to even fewer opportunities to enter the workforce (Pohl and Walther Citation2007) – possibly culminating in a complete retraction and disengagement from any activity related to work, education, training or job search (Maguire Citation2015).

Active labour market policies (ALMPs) are designed to intervene in this cycle and improve the relation between supply and demand in the labour market (ILO Citation2003). One subgroup of those policies, which is prevalent in most modern welfare states, are activation policies (Eichhorst and Rinne Citation2015). These specifically aim at increasing the active participation of benefit-dependent individuals in the workforce (as opposed to other ALMP objectives, such as an increase in technical skills). Activation policies typically have both enabling and demanding elements – i.e. they provide support conditional on certain cooperative behaviour of their participants, and are focused on triggering a behavioural change of those participants towards an active and successful job search (Pohl and Walther Citation2007).

A vast amount of literature has studied activation policies’ objectives, mutual-obligation philosophy and implementation (for an overview see: Eichhorst, Grienberger-Zingerle, and Konle-Seidl Citation2008; Fromm and Cornelia Citation2008; Dinan Citation2019). Evidence on the effectiveness of those policies shows mixed results, with limited impact especially for the already long-term unemployed (Konle-Seidl and Eichhorst Citation2008; McGuinness, O’Connell, and Kelly Citation2014). However, little attention has been paid to how these policies are supposed to produce their effects, and what chain of mechanisms unfolds upon and during implementation. What makes some youth choose not to participate in the labour market in the first place? What are the attitudinal and behavioural mechanisms that successfully ‘activate’ this target group – i.e., make them step-up their job search and participate in a vocational activity? Why are some programmes successful while others are not? What kind of personal change enables participants to actively take part in vocational education, training or work?

This research aims to address this gap by tracing attitudinal and behavioural change processes of unemployed young participants of a variety of activation-oriented job training programmes in Germany. The study investigates personal change beyond the training context, taking a holistic perspective to processes and drivers of change experienced by participants. It then sheds further light on those aspects specifically relating to the intervention. Greater awareness of the different mechanisms of change underlying these programmes is paramount for the design of effective labour market initiatives to activate unemployed youth. Knowing what can trigger the desired change in attitudes and behaviours, and of how these changes unfold, is essential for the incorporation of these triggers in an intervention context. Our ability to do this is currently limited, as neither the academic nor the practice literature have investigated in depth the personal change processes, or the detailed theories of change of activation policies and programmes.

2. Perspectives on change mechanisms of activation policies

2.1. Activation policies

The concept of ‘activation’ in social policy does not have a formal definition and can, depending on the respective context, vary in purposes and target groups (Eichhorst, Grienberger-Zingerle, and Konle-Seidl Citation2008). Today, the European Union defines activation policies as ‘policies designed to encourage unemployed to step up their job search after an initial spell of unemployment, by making receipt of benefit conditional on participation in programmes’ (Eurostat Citation2019). The objective of making people actively participate in job search, training and/or work and thereby rapidly reduce their dependency on public welfare is a common feature of activation programmes (Pohl and Walther Citation2007). The underlying principle is based on a dynamic of ‘demanding and enabling’: The achievement of objectives is a shared responsibility between individual and state, which materialises in support and benefit reception being conditional upon the verifiable fulfilment of certain obligations by the unemployed – e.g. job search, participation in training and acceptance of job offers (Pohl and Walther Citation2007; Eichhorst, Grienberger-Zingerle, and Konle-Seidl Citation2008; European Commission Citation2018). Most modern industrialised countries nowadays comprise a range of activation programmes as part of their labour market policy (Eichhorst, Grienberger-Zingerle, and Konle-Seidl Citation2008; Dengler Citation2019). Nevertheless, little information can be found on how activation programmes are expected to reach their objectives, i.e. the theory of change of their practical implementation.

In Germany, the principle of welfare to work, based on activation and mutual obligation of the state and the unemployed (‘support and demand’), underpins the ALMP system (Ehrich, Munasib, and Roy Citation2018; Dengler Citation2019; Holzschuh Citation2019). Activation policies have the objective to strengthen the self-responsibility of those entitled to benefits who are fit for work, enable them to support themselves independently from the social security system, minimise their need for assistance, maintain, improve or restore their ability to work, and foster the uptake of gainful employment (§1 Social Code II, Section 2). The Social Code (§45 Social Code III), lists objectives such as access to the labour market, reduction/removal of personal barriers, enhancement of formal employment and entrepreneurship promotion – to be achieved through assessment of existing capabilities and circumstances, skills training, application training and job search counselling (Kopp Citation2019). Formal documents fail, however, to outline how those interventions are supposed to achieve their aims and what assumptions and theories inform their design. Interim targets are rarely formulated and tracked (Deeke and Kruppe Citation2003; Spermann Citation2015). Some which are commonly discussed (albeit rarely monitored) include participation in the programme (Harrer, Moczall, and Wolff Citation2020), adoption of a regular work rhythm as required by the labour market (Eichhorst, Grienberger-Zingerle, and Konle-Seidl Citation2008), and avoidance of withdrawal – which could lead to a condition of ‘discouraged worker’ (Hartig, Jozwiak, and Wolff Citation2008). The literature stresses the importance of improving capacity, employability and competitiveness through skills transfer, as well as increasing motivation and compliance through sanctions (mostly benefit cuts) (Deeke and Kruppe Citation2003; Oschmiansky Citation2010; Holzschuh Citation2019). Eichhorst, Grienberger-Zingerle, and Konle-Seidl (Citation2008, 5) refer to this strategy as ‘the conceptual and practical combination of demanding and enabling elements’.

2.2. Theoretical approaches to activation

The concept of activation as a means to achieve labour market integration is not covered explicitly by any theory in the social sciences. In the following sections, different theoretical frameworks are explored for their potential to explain change mechanisms of activation policies.

2.2.1. Classic microeconomic search models

According to classic microeconomic job search theory (Mortensen Citation1986), a rational individual will invest as much time and effort in searching for jobs based on the comparison between expected outcome and their value of leisure – specifically, until the marginal return to the search effort exceeds its marginal cost. Under this framework, activation programmes may have two effects: increasing the unemployed’s chances of receiving job offers and the willingness to accept them (Hujer, Thomsen, and Zeiss Citation2006). The first effect reflects the promoting elements of activation policies; support and skills transfer will lead to an increase in human capital and/or job search effectiveness, which in turn leads to a better matching with existing labour demand. The second effect reflects the compulsory aspects: sanctions and/or obligations attached to benefit reception are assumed to decrease the desirability of unemployment. The two effects would make the unemployed youth want to evade the situation, i.e. activating job search and encouraging the acceptance of job offers (Dengler Citation2019). Activation programmes should then be designed with a focus on incentivising the unemployed to quickly (re-)integrate in the work force by enhancing their skillset and/or moralising their behaviour (Bonvin Citation2008; Konle-Seidl and Eichhorst Citation2008).

This theoretical perspective has a range of limitations. Firstly, the only outcome of interest is quick labour market integration, which might happen at the expense of job quality and sustainability, thereby becoming more costly for the state in the long term. Secondly, its explanatory logic mainly revolves around search effort and wage. In modern labour markets, however, a more differentiated and multidimensional picture is needed to understand the factors entering decision-making processes. Furthermore, experimental evidence showed that the quality and efficacy of the chosen job search strategy might be of higher relevance than the mere search intensity (Arni Citation2015). Finally, the theory is based on the assumption of rationally acting individuals, while people often hold biased beliefs strongly influencing labour participation decisions (Arni Citation2015; Spinnewijn Citation2015). Unemployed youth’s personal backgrounds and individual circumstances might act as barriers through multiple pathways – for which the provision of cognitive tools and incentives is no silver bullet. In order to understand the heterogeneity of effects of activation programmes for this complex and diverse target group, and shape their design appropriately, in-depth understanding of specific abilities, needs and processes is crucial.

2.2.2. The capability approach

A different perspective is taken by the capability approach (Sen Citation1985). The outcome of interest is the expansion of people’s capabilities, intended as the‘ ability to do valuable acts or reach valuable states of being’ (Nussbaum and Sen Citation1993, 30). This approach intrinsically comprises the concept of empowerment: Individual endowments and contextual circumstances act as conversion factors determining the extent to which freedom and resources can be transformed into actual capacity to act (Sen Citation1985; Bonvin and Orton Citation2009). From this viewpoint, the final objective of activation policies should be to enhance participants’ capabilities, i.e. to grant them the freedom to perform a vocational activity that they value. Intermediate outcomes would comprise the appropriate equipment with skills and resources, as well as the creation of an enabling environment (Bonvin and Orton Citation2009).

This concept of activation is aligned with Anthony Giddens’ notion of a democratic, participatory relationship between individuals and the welfare state. According to this viewpoint, negotiation and agreements which recognise and foster the individuality of the unemployed are beneficial for activation, as opposed to external pressure (Giddens Citation1998).

Differently from microeconomic theories, the capability approach puts individuals and their idiosyncrasies at the helm of their own journey of change. Adequate freedom of choice, necessary resources and the capacity to use these resources would enable individuals to enter the labour market in the ways they value. The imposition of duties would be detrimental to the development of capabilities, as the freedom of choice in creating ones’ own path is paramount. While classic microeconomic search theory builds on the compulsion effect to increase responsibility (and consequent activation) of the unemployed, the capability approach maintains that freedom of choice and empowerment are essential pre-requisites for taking responsibility (Bonvin Citation2008), and equipping people with the means to enact their agency is crucial for genuine empowerment (Bonvin and Orton Citation2009; Sztandar-Sztanderska Citation2009). Activation thereby unfolds its effects through enabling empowered youth to act freely.

It should be acknowledged that taking control over one’s own personal process is not always feasible and/or desirable for some individuals, for example when they are not ready to do so due to physical or mental health issues (Van Hal et al. Citation2012). In addition, the approaches discussed above are unable to explain how activation schemes are supposed to address the heterogeneity of participants’ personal development processes.

2.2.3. Career development theories

Work psychology focusses on an individual’s career-related decisions and actions. A range of career theories analyse the subject of vocational choice, i.e. how and why people select a certain professional pathway (Super Citation1953; Holland Citation1959; Osipow Citation1968). Developmental theorists understand career decisions in the context of people’s overall human development (Super Citation1953; Ginzberg Citation1972; Savickas Citation2005). According to this perspective, career development starts with the development of a vocational self-concept taking place from childhood until the early teenage years, followed by a phase of exploration, skills acquisition and vocational choice until the mid-twenties, which later becomes fostered through work experience (Super Citation1953). Consequently, if individuals do not psychologically mature in their sense of self and in key abilities (e.g. the ability to delay gratification), their career development will be restrained (Osipow Citation1968). From this perspective, activation policies should focus on supporting the individual’s personal maturation process, for example through the provision of information enabling them to reach developmental outcomes which are crucial for appropriate decision-making (Super Citation1953; Osipow Citation1968; Savickas Citation2005).

2.3 Gaps in the activation literature

Career avoidance or vocational non-participation have received little explicit attention in the literature, despite being notable challenges for modern welfare states and being widely addressed through activation schemes. Peck and Theodore (Citation2000) see the roots of unemployment predominantly in behavioural aspects, and emphasise the need for ALMP to look beyond the classic employability-focused logic and concentrate on motivations and expectations of their beneficiaries. Similarly, Senghaas, Freier and Kupka (Citation2019) highlight the need to dedicate more attention to the emotional aspects of activation for frontline work. The theoretical frameworks discussed above can only provide indirect inferences on processes underlying vocational activation. They are unable to understand the diverse and complex cognitive-behavioural mechanisms that may keep the unemployed youth from actively participating in the labour market, and their implications for an effective functioning of activation policies. Similarly, the literature on activation in practice mostly focuses on the structural design features of the systems (Tergeist and Grubb Citation2006; Pohl and Walther Citation2007) and lacks a more profound engagement with theory of change and causal mechanisms.

From an empirical perspective, the impact of activation programmes has shown to be mixed and heterogeneous, without allowing for clear conclusions overall or for particular demographic subgroups (Eichhorst, Grienberger-Zingerle, and Konle-Seidl Citation2008; Konle-Seidl and Eichhorst Citation2008). For example, there is evidence that the impact on individuals who are long-term unemployed or have multiple personal barriers can be trivial (Harrer, Moczall, and Wolff Citation2020) or even negative (Fromm and Cornelia Citation2008). This is startling, considering that activation programmes particularly address those furthest from the labour market. There is some indication that activation policies can increase self-confidence and create enhanced opportunities through helping participants to tackle personal barriers (Fromm and Cornelia Citation2008). Persuasion and trust building have proved to be important strategies for job centre agents to achieve activation with clients (Senghaas, Freier and Kupka 2019).

A major gap in our knowledge concerns intermediate processes, which remain hidden in a ‘black box’. What is behind the ‘treatment effect’? Which attitude changes precede behavioural changes (e.g. increased search behaviour), and how can they be promoted through interventions? How can activation programmes enable unemployed youth to shape their own vocational path? Such questions can hardly be answered by the customary monitoring and evaluation excercises, which mostly focus on crude activity statistics (e.g. attendance, number of job applications) and labour market outcomes (European Commission Citation2018).

In order to understand how activation materialises in the practice of policy implementation for its ultimate beneficiaries, it is necessary to conduct in-depth qualitative research (Sztandar-Sztanderska Citation2009).

3. Methodology

3.1. Analytical approach

In the field of policy evaluation, there is increasing recognition that theory-based evaluation approaches are useful and necessary to understand the causal linkages between an intervention and its outcomes (White Citation2010). Especially in complex settings with a heterogeneous target group and a high likelihood of several ‘unobservable’ factors influencing programme effectiveness, it is necessary to unpack the causal mechanisms underlying the observed effects in order to understand how and why programmes work (Rogers Citation2008; Astbury and Leeuw Citation2010). Given the limited theoretical and empirical literature on the question of how activation policies bring about change for their beneficiaries, this study follows a mechanism-based approach of theory-driven evaluation. It aims at identifying the change processes young people experienced over the course of their participation in activation programmes and carving out which of those changes could be causally related to the intervention sphere, and why. Based on those insights, the objective of this study is to derive a more comprehensive theory of change with regard to these programmes.

3.2. Sample and data collection procedure

This study was part of a wider longitudinal research project on the mechanisms of ALMP effectiveness. The full sample of the study presented in this paper (n = 165) had participated in a baseline survey when starting different types of training in Berlin which included activation as part of their main targets. The study has been approved by the ethical board of the university to which the authors belong.

Due to the lack of sampling frame for training interventions for the unemployed in Berlin, a systematic sampling procedure was followed aiming at capturing the socioeconomic heterogeneity of the population of interest. We obtained the contacts of 39 organisations providing training for unemployed youth in Berlin, mainly through the lists of all contractual partners working with the two main funding sources for ALMPs in Germany. These were contacted via email and 18 of them agreed to collaborate. Selection criteria for study participation were 15–25 years of age, unemployed and about to enter an activation programme with a foreseen duration of 3–12 months. A total of 29 training interventions were selected, including classroom-based application training, technical skills training, personal job coaching, low-entry-level integration support, and several combined schemes. Informed consent was secured from all participants at baseline stage. Purposive sampling was then applied with training participants upon their programme finalisation, until data saturation was reached (Glaser and Strauss Citation1967; Saunders et al. Citation2018), in order to ensure maximum variation of the sample with regard to relevant criteria (e.g. training type and duration, gender, age, education, social status and unemployment duration, see ).

Table 1. Sample characteristics

In-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted face-to-face with all study participants after their programme exit between January and December 2017. Interviewees were openly asked to reflect on any personal change they experienced over the time of their training participation. Probing follow-up questions were asked to elicit illustrative examples of relevant attitudinal and behavioural changes, and how they were brought about. Interviewees were on average 19.6 years old and had an average unemployment duration of approximately one year. 43% were female, 40% percent came from a low socio-economic area and around half had no or only basic secondary school education.

Note: Socio-economic status was measured based on a classification of the respondents‘ residential districts according to the Social Index I (2013), which is composed of indicators of unemployment, reception of public benefits and health-related indicators in Berlin.

3.3. Data analysis

Data analysis was undertaken in three stages. After a detailed familiarisation with all answers, the second stage consisted of thematic content analysis. Supported by NVivo 11 Software, respondents’ original answers were coded in different themes within two macro-categories: (A) phases of personal change and (B) triggers to transitions in-between those phases. In the third stage, the identified codes were revised and re-structured into main themes and sub-themes for each of the A and B categories (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). In keeping with the objectives of this study, coding was performed inductively, letting themes arise from the data instead of following a pre-set theoretical framework. Repeated patterns or journeys of change emerged from this analysis, which eventually led to the 7-stage process model presented below.

4. Results

4.1. Results overview

The change processes derived from the thematic analysis can be summarised in seven main phases of change.

Vocational availability: The process from complete inactivity to general vocational availability, i.e. the willingness to participate in training, approach job search and set career-goals.

Self-testing: Once vocationally available, becoming ready to explore the labour market and one’s own skills through workshops, internships and placements.

Self-knowledge: Gaining greater awareness of one’s own personal strengths, weaknesses, barriers, interests, preferences, possibilities and career goals.

Self-confidence: The attitudinal change arising from improved self-knowledge, leading to a more positive outlook into the vocational future, including increased self-efficacy and hope with regard to the achievement of personal goals.

Goal orientation: The process of focusing one’s decisions and actions towards the achievement of self-set career goals, including the active addressing of previously identified personal barriers.

Vocational activity: The process of entering in concrete vocational action, such as active and effective job search, starting work, re-entering education or participating in specific programmes aiming at the removal of personal barriers to enter education or work.

Perseverance: The ability to continue the activities mentioned in the previous phase despite experiences of frustration, developing resilience to rejection.

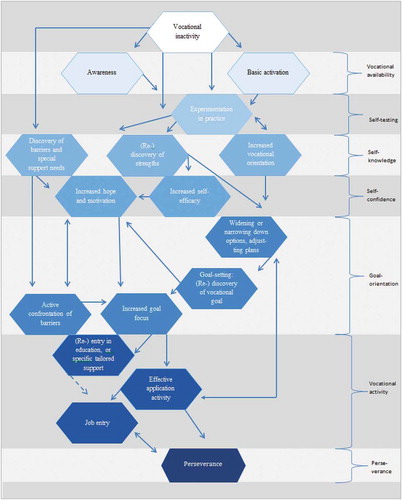

The seven phases do not necessarily unfold in a specific order. Some concern behavioural changes, while others relate to attitudinal changes or changes in (self-) knowledge. gives an overview of the individual change processes identified, their interactions and possible recursive patterns. It is important to highlight that each individual phase of change can directly lead to the final goal of vocational activity, without necessarily passing through any of the other phases (these connectors have been omitted in for the sake of expositional clarity). For example, for some participants the mere change from complete passivity to vocational availability (phase 1) might be sufficient to find a job.

Figure 1. Overview of the seven change processes from vocational inactivity to perseverant activation

The data analysis indicates that each phase comprises several elements – themes, sub-themes and triggers of change, as summarised in below.

Table 2. Overview of findings: seven phases of activation, their elements and drivers

4.2 Case study

For example, one 22-year old male described repeated past training dropouts as an experience of failure which shocked him (phase 1: awareness through repeated failure). This awareness boosted his willingness to work on himself, but also put strong pressure to succeed in the next endavour. In the job training programme he felt understood and listened to, and described conversations with staff as instrumental to recognising his previously lost self-worth. Through experimentation in workshops, his manual skills became evident, which staff positively mirrored back to him, while assigning increasingly challenging tasks to him. He described this experience as a key factor for him to dare more (phase 2: self-testing through encouragement, push, persistence and positivity). He described a process of increased focus, opening up to new professions, as well as improved self-worth and confidence as the development that eventually led him to secure an apprenticeship (phases 3–6: discovery of strengths and increased vocational orientation through positive feedback; improved hope and motivation; widening of vocational options; active and successful job search).

4.3 Detailed results

4.3.1. Vocational availability: basic activation and/or a change in awareness

4.3.1.1. Basic activation

The first phase of change relates to the transition from a state of paralysis or general vocational inactivity to being available for the labour market. This availability comprises two different elements: The first one is the mere willingness and ability to engage in any regular work-related activity, such as attending the intervention itself. Since they left school (often prematurely without accomplishing the envisaged degree), many youth have experienced periods where they did not engage in any kind of work or training. These ‘hanging out’ phases can last from a few months to several years, resulting in a decline in the ability to follow a regular daily structure and comply with attendance times and rules, which in turn increases barriers and hampers the chances to enter the labour market. Several respondents (n = 20) mentioned exiting from this ‘hangout’ phase and having a regular place to go to as a positive change resulting from the intervention, which consequently triggered them to re-engage with their professional orientation. One participant described:

It was a better feeling than just staying at home. (…) I used to go because I had to, but then I actually started enjoying it a bit (19-year-old male).

This ‘basic activation’ phase simply refers to young people leaving a domestic passive idleness and embrace a regular daily structure in preparation for the requirements of future employment. When asked for the triggers of this change, respondents mentioned obligations attached to the intervention, such as clear rules, set arrival times, a demanding schedule, as well as group cohesion for the compliance with those rules. More specifically, joint group rituals for starting and ending the day, as well as attendance and engagement rules followed by sanctions in case of non-compliance were highlighted positively. In contrast, many participants (n = 20) found the absence of clear rules or adherence to these rules by training staff and a laissez-faire attitude demotivating.

4.3.1.2. Change in awareness

The second aspect of vocational availability is related to a more general attitudinal change and represents one of the most important themes identified in this study. It can be labelled as ‘awareness change’. The respondents describing their experience under this theme (n = 16), referred to a change from a state of indifference/phlegm to an insight about the importance of work for their future, as well as the need to make an effort in order to progress professionally. This goes along with a shift of perception from a ‘quick win’ perspective and expectation towards long-term thinking. This realisation is often described as having a strong impact on beliefs and behaviour. The following four sub-themes were identified as contributing triggers to enter this phase.

4.3.1.3. Repeated failure and regret

The first trigger refers to the repeated experience of failure, recognised as self-inflicted, in the vocational sphere. This often comprises multiple dropouts of school and previous attempts to start apprenticeships, for example due to incompliance with the rules as a type of self-sabotage. As one respondent pointed out:

I still struggle, but I have learned my lesson. I know now the consequences if I don’t work on myself. The shock shook me up, even though it was predictable – I did not want to see it. The surprise was even bigger then. (22-year-old male)

Others applied low effort due to over-optimistic assessments of market requirements. The most recent experience of failure preceding the intervention was perceived the ‘last straw to break the camel’s back’ revealing that more effort is needed to achieve the desired outcomes and avoid future self-imposed experiences of failure.

4.3.1.4. Peer-comparison and time pressure

A second trigger is related to the youth’s perception of time and their personal development in comparison with their peers. Respondents described a feeling of being left behind, when they noticed similar-aged friends getting degrees and progressing in their careers. This perception can be amplified when a certain milestone age is reached (e.g. 18 years of age), which matches a change of legal or formal category. Related to this effect is the aspiration of tangible goals or goods which are associated with being a successful adult member of society, such as having a car, living independently and/or being able to provide for a future family. A 20-year-old female respondent illustrates this:

You become older and start thinking about the future. This is the aspect where I have understood a lot. You want a family one day, and be able to give them opportunities. I will turn 21 and do not yet have a degree. Age makes me ambitious to get things done now.

Peer-effects can also act as a threat or a scare. Over time, respondents observed some of their peers delving deeper into deviant behaviour, becoming criminal and/or not progressing personally and professionally, and they developed a desire to not follow the same pathway. A change of peer-group then often went along with a shift in perspective, with either one or the other coming first. This effect could also be triggered through peer-contact within the intervention, with several respondents observing others trapped in loops of repeated failure and demotivation.

4.3.1.5. Trustful conversations

Serious conversations with close well-trusted people emerged as another trigger for a change in awareness. This comprised family members (mostly siblings or uncles), as well as training staff, where a positive personal relationship prevailed. The following quote shows an example where the attitudinal change was supported through conversations with intervention staff:

I concentrate more on my work-life now, the trainer opened my eyes. This used to be a secondary matter in my life. Through the conversations with her, I see now how important that all is. My vocational choice itself has not changed, but my interest in the whole issue, and my will to do it. (16-year-old male)

4.3.1.6. Surge in responsibility and/or stroke of fate

A final mechanism leading to an increased awareness is rooted in life events that caused a major change in the youth’s private sphere, which either required a surge in responsibilities and/or triggered general consciousness. Among these occurrences are the death or illness of a family member, the divorce of parents, or the birth of a child. Young respondents described such events as triggering a leap in maturity, often related to care responsibilities and a shift in focus on what matters.

4.3.2. Self-testing: three P’s – push, positivity and persistence

A second type of change described by respondents was the transition from a rather ‘internal-theoretical’ occupation with their professional orientation (or none at all) towards ‘getting out there’. This includes testing their abilities and interests in practice, for example through engaging in internships and work placements, or manual workshops in the training environment. This step was sometimes taken proactively as a direct consequence of the previously described surges in awareness or basic activation, while in other occasions it was the result of further triggers, those being mostly situated in the intervention sphere. Participants described being challenged and pushed by trainers, in combination with feeling appreciated and recognised in their personal potential, as enticements to activation and self-experimentation. The following quote by a 17-year old male respondent illustrates an example of this experience:

My way of thinking has changed completely. I am only positive now; as soon as I arrive, I switch on the PC and start looking for internships. At the beginning, I was very lazy. Mrs Q caters to her trainees very well; she shows interest and also tries to establish a private connection. I am in good contact with her and also tell her private stuff. At the beginning she had to ‘kick my butt‘ a lot. That was good.

A close, personal and trustful relationship with the trainer was usually an essential basis for this mechanism to set in, with examples showing counterproductive effects of challenging participants without a sound relationship in place. In this context, positivity/optimism and constant persistence by trainers were frequently emerging themes. The combination of personal sympathy and interest with pressure made young people feel cared for and believed in, which positively affected their self-concept and motivation and, consequently, their decisions to approach the labour market. The following quote shows the importance of the perceived personal interest of the trainer:

She was very committed, she forced me to inform myself and approach people. She was behind it, saying that the company will kick me out if I don’t write applications. She really wanted me to find an apprenticeship. (20-year old male)

While some respondents highlighted the ‘push’ elements of this mechanism, others emphasised the persistence and positivity as the crucial factor, as the following quotes illustrate:

He just kept on going. He saw potential in me and did not give up; he pulled it off and stayed persistent. I found this admirable. (20-year old male)

Mr. X was very different. I only knew him for a couple of days, but he insisted so much that I finally searched for a job and found one. Due to him, I made an effort. (…) He annoyed me, every morning he came and made suggestions, gave me websites and brochures … . He wouldn’t let anything slip. I did not feel left alone. (20-year old male)

4.3.3. Self-knowledge: identifying barriers and strengths, adjusting options and forming goals

In this phase, young people experienced an increased understanding of their personal strengths, weaknesses, barriers, needs, interests, possibilities and, ultimately, career orientations. Three sub-themes emerged from the interview data.

4.3.3.1. Identifying barriers and special support needs

Considering the diversity of the population of unemployed young trainees, it is not surprising that many of them have special needs that require a different type of support than the one provided in the here contemplated programmes. This includes psycho-social support, such as therapeutic or debt advice, as well as more specialised sectoral training. The identification of those needs is crucial, not only in order to provide appropriately tailored support, but also as an important element of self-awareness for youth to shape their further vocational pathways. In this study, young people narrated about the discovery of personal limitations and specific support needs as an important milestone in their individual change processes. This was often initially an adverse experience, but eventually lead to an increase in hope, motivation, and to the identification of new opportunities and more suitable support modalities (see further phases of change below). The recognition of those needs sometimes took place as a direct result of the previously described self-testing phase, followed by an appropriate de-briefing on the insights gained from this phase. In other cases, it was a result of trainers mirroring their perceptions of participants’ abilities and needs. Occasionally, ability tests also helped to support this process.

4.3.3.2. (Re-) discovering own strengths

Similarly to the previous sub-theme, the identification of strengths emerged as an important part of the journey of change. It was often a direct result of the self-testing on the labour market, with internships and work experience providing important affirmation to the young participants. Another channel was the previously mentioned feedback on strengths by trusted trainers. Interestingly, several respondents described the insights gained in this phase as a re-discovery, remembering what they are good at from other spheres of (non-professional) life and/or previous times before they experienced repeated failures. A strong effect on the participant was often observed when a trainer showed both in-depth personal interest in understanding the participant’s underlying strengths, as well as the ability to mirror their impression back to the young person. As a 24-year-old female participant pointed out:

You just need to be woken-up and have a neutral counterpart who reminds you of who you really are.

4.3.3.3. Improved vocational orientation

Improved vocational orientation is another direct effect of the experimentation. It reflects the iterative process of testing and refining ideas and opportunities and gaining an increasingly clearer picture of one’s own position and interests in the labour market, or, in Super’s (Citation1953) terms, career self-concept. Without necessarily having a clear idea of their professional vision yet, this is still an important phase of change for unemployed youth towards setting a vocational goal.

4.3.4. Self-confidence

Increased self-confidence is an aspect of positive change described by a range of respondents. It materialises in reduced fear to take part in job interviews and speak to others, increased self-efficacy for the accomplishment of job search-related tasks, greater hope and optimism with regard to the possibility of achieving one’s goals, and higher resilience towards rejection. The improvement in self-efficacy was frequently described a result of the preceding phases of self-testing and (re-)discovering one’s own strengths. Furthermore, it could develop as a result of enhanced self-reliance and independence in the intervention, which forced participants to find own solutions (with a particular strong effect for those taking part in an internship abroad). This is a reflection of an empowerment experience where participants gained control over their professional process through an increase in self-knowledge and certain – even initially often unwelcomed – freedom. It constitutes an important interstation to subsequent phases of change, such as goal-orientation, which will be described in the following.

In conjunction with an increase in self-efficacy, young participants often also reported a surge in hope. New scenarios opened up, or existing ones appeared more achievable, which in turn boosted motivation. The hope subtheme also emerged as a result of the previously mentioned identification of barriers and special needs – some young people appeared to be stuck in loops of repeated failure without understanding the reasons. Unveiling personal barriers and identifying feasible strategies to tackle them could offer an entirely new horizon of options. In these cases, flexibility and comprehension by trainers were highlighted positively. One trainee reflected:

They showed empathy for fears, and we dealt with it together. For example, at the beginning, they took me a bit by the hand; even accompanied me to a job interview. I used to be very shy. When I had a really bad day, they also understood and left me in peace. Our problems were taken seriously. (22-year-old male)

4.3.5. Goal-orientation: finding a vocational goal and focusing on its achievement

The phase of goal-orientation comprises the adjustment of vocational visions, the specific identification of a vocational goal, as well as an increased focus on its achievement, including the active confrontation with previously interfering personal barriers.

4.3.5.1. Widening or narrowing down vocational options

A direct result of the identification of strengths and improved vocational orientation was often the adjustment of options for the individual’s professional pathway. Some young people found in their internships the vocation they wanted to follow further, or a new field to explore, while others found out what was not suitable for them and adapted their scope accordingly. This included the decision to go back to school as a result of not enjoying any practical activity, or the acknowledgement that a profession (or salary) of interest required a higher educational degree. In this context, the immediate practical insight into the requirements and conditions on the labour market (e.g. through job fairs, work experience or unsuccessful job search) was an important trigger for the adjustment of vocational options. This process could be supported by trainers providing professional guidance and nudging participants to consider a Plan B, while allowing them to maintain the autonomy over this process.

This autonomy aspect was crucial, as pushing youth too far away from their personal career visions – even though those were unfeasible – without counting on their ownership of this transition, repeatedly led to counterproductive effects such as complete rejection of the trainer and intervention. Allowing for gentle, accompanied experiences of failure in situations of unachievable visions was a more promising strategy than ‘dream-crushing’. In this phase, an improvement of self-knowledge in different aspects is the overarching theme, which resonates with the earlier presented career theories: The results reflect especially Super’s (Citation1953) career developmental approach that highlights the importance of the development of a career identity for taking appropriate vocational choices. Through identifying own strengths and barriers, participants gained more clarity on their ‘vocational selves’, which allowed them to take action towards an improved career orientation.

4.3.5.2. Goal-setting

A substantial share of interviewees (n = 34) identified a specific vocational goal for themselves over the course of programme participation. Two main pathways emerged as enabling this important milestone: Firstly, the above outlined process of self-testing and identification of strengths, resulting in improved vocational orientation and in the identification of a clear goal. The second pathway is not related to experimentation in practice and has a rather cognitive character, with young people coming to an insight of what they really want to do through reflection. Two subthemes arose from the interview data as triggers for this reflective insight: the first trigger consisted in trainers showing a profound interest in the participant’s passions and dreams, and listening to them. This was often positively emphasised in contrast to previous experiences in other interventions and/or with family members. Respondents under this subtheme repeatedly described being asked for their personal visions and being taken seriously as a unique experience, whereas they were used to others wanting them to find any job as quick as possible. A 20-year-old female trainee expressed this in the following way:

Mr. X worked with me in a way that we moved towards my wishes. It then made ‘click’ for me, and I thought, why did you actually waste your life so far? That showed me again what I actually want to do. As if someone had just nudged me from the back and said ‘just go and do it‘. (…) before that, nobody has ever asked what is my dream job.

The second trigger to finding a vocation was related to being in some situation of retreat or isolation, which gave the individual space to think, enter an inner dialogue on their personal visions and gain clarity within a confusing range of options and opinions. In this context, respondents referred to a combination of intervention- and non-intervention-related situations, such as the forced independence in foreign internships, the conscious own decision to detach from a debilitating peer-environment or partner, a reflective theatre role play in the intervention, and time in prison. One participant summarised it as:

I was being told all those different things and never knew what I wanted. When I reflected properly for the first time, I clearly knew that I wanted to go back to school and get my degree. (18-year-old-male).

These experiences can be interpreted in relation to the element of freedom, which is central to the capability approach. When respondents perceived the freedom to choose their professional path, either due to the mere absence of ‘background noise’ to their own inner voice, or due to an empowering interaction with trainers who offered the prospect of helping to convert this freedom in actual achievability of the goal, they successfully progressed in their goal-setting.

4.3.5.3. Confronting barriers

Actively tackling the previously identified barriers constituted another important change for several interviewees. It was part of them taking ownership of their future, acknowledging where they needed help and not being too proud and/or afraid to seek for it. While some participants immediately proceeded to looking for support after they acknowledged their personal barriers (e.g. by starting therapy, or seeking legal or financial advice), more commonly the step from acknowledgement to action was a substantial hurdle, accompanied by fear and resistance. Those who successfully overcame this hurdle mentioned similar triggers to their behavioural activation than the ones listed for phase 2 above: Push, positivity and persistence by trainers, on the basis of a close relationship determined by personal interest and care, trust, and feeling believed-in. A 20-year-old male with a history of repeated intervention dropout and debt problems remarked:

I did not want a debt advisor at all. Mr. X [the trainer] insisted for months on it, we discussed all pro’s and con’s upside down. At some point I just gave up to stop him bothering me … At the beginning I was very reluctant, but now I tell the advisor things I would have never expected … He really wanted me as a client, I noticed this.

4.3.5.4. Increased goal-focus

An increased focus on the active persuasion of their vocational goals was reported by a substantial share of interviewees (n = 31). This usually happened as a consequence of the previous phases, such as the change in awareness, the re-discovery of a vocational goal, the active confrontation of barriers, and/or an increase in self-efficacy and hope through self-testing and the identification of own strengths. A 20-year-old female who was about to re-enter formal education after having dropped out several times emphasised:

This time it will work out, because today this is more important for me and I take it much more seriously. Now I also know why I want to do it. Formerly, I did not know this, and I had so much other trouble … money problems and no stable home.

A young mother highlighted her change in perspective following an internship abroad:

I became more self-confident and optimistic. As I was all on my own, I got to know a different personality. Previously, I thought I would anyway not achieve my goals. Now I don’t care what others think, I will pull it through!

4.3.6. Vocational activity

A key phase of change. and the ultimate goal of most activation policies, is the process of the young unemployed entering in concrete interaction with the labour market – through active and effective job search and applications, starting work, re-entering education or participating in specific programmes aiming at the removal of personal barriers to enter education or work. An increased application activity was reported by a range of respondents as a result of the previously described processes. The decision to continue secondary education or enter a specific support programme was often taken as a result of the phase of self-knowledge. Respondents who found a job through the intervention did refer to more ‘tangible’ tools as positive promotors of this success, such as the transfer of application skills and contacts, support when developing their CVs and cover letters, as well as the rehearsal of job interviews. This finding relates to both classic microeconomic models, where an increase in human capital and search effectiveness constitute the enabling effects of activation policies, and to the capability approach, where skills and competences act as conversion factors to achieve the ultimate personal goals.

4.3.7. Perseverance

The seventh and final phase of change relates to an increased perseverance through the experiences of setbacks. This comprises both resilience to rejections during the application process, and the ability to persist on a chosen pathway (e.g. going back to school or starting an apprenticeship) without dropping out prematurely. As causal drivers for this attitudinal change, respondents often described having gained a wider horizon and a long-term perspective, with insights in the advantages of delaying gratification and exercising effort towards in favour of future benefits. Drivers for this perspective change are similar to those described above for a change in awareness, and relate to an increase in maturation. Triggers were both in the private sphere (e.g., due to a new relationship or the prospect of a family to look after), as well as in the vocational sphere (e.g., through the threatening effect of gaining insights into labour market conditions for the non-qualified, or a shock due to repeated failure). Also positive experiences with regard to the own skills and ability to persevere acted as triggers, leading to self-affirmation and increased confidence and motivation.

5. Discussion

The insights from this study show that the vocational activation of the unemployed youth can be a complex process, with a range of interdependent phases and drivers of change differing in importance depending on individual histories, characteristics and experiences. Some of the identified factors contributing to the different phases of attitudinal or behavioural change were located within the control sphere of labour market programmes, while others were embedded in larger processes of personal maturation. However, all identified phases of change comprised some drivers where the activation programmes had an immediate influence, such as the empowering effect of pushing and positively encouraging young participants, or the careful guidance on the inwards-bound journey of discovering their career self-concepts. When it comes to the design and implementation of interventions, being creative in stimulating also the more general triggers of personal change is paramount. For example, this study showed that processes of personal awareness and maturation could be triggered through the replication of real-life events in theatre and roleplay.

None of the discussed theories can provide alone a satisfactory framework for a comprehensive theory of change of activation policies. The classic ‘carrot and stick’ based microeconomic search models, on which activation policies in Germany and many other countries are based, proved too simplistic and could explain only a small part of the complex picture (namely, the basic activation at the very beginning, and the human capital increase at the very end of the here described chain of change mechanisms). The complex cognitive-behavioural processes that can materialise in-between or in parallel of those observed effects are unaccounted for. A broader perspective is therefore necessary to successfully activate unemployed young people, analyse career developmental phases and capabilities before and during the intervention in-depth, and design appropriate empowerment strategies to foster this change.

It is recommended to consider the seven phases for both the design and monitoring and evaluation of activation policies, thereby adopting a more appropriate holistic framework for the implementation of those programmes in practice. In this context, the capability, empowerment and career development approaches provide helpful elements for explaining some of the identified change processes: A major theme emerging from the data was indeed the development of a career identity, based on the careful facilitation of self-knowledge and the consequent successful conversion of this knowledge into action. Another crucial phase of change comprised the surge in awareness for the importance of career-related decisions and own responsibilities. Both phases were related to more general processes of maturation and personal development, as proposed by Super (Citation1953).

Translating those insights to an intervention strategy might comprise, for example, a tight combination of pushing and encouraging for some participants in order to help them develop the resources and conversion factors (e.g. self-efficacy) to gain control over their professional pathway, while a targeted provision of autonomy will be needed for others – or for the same individuals in a different phase of change. A thorough analysis and continuous monitoring through phases of change are therefore crucial to ensure the effective implementation of activation programmes. For this purpose, the goals of activation policies need to be set in a more granular way, capturing and monitoring intermediate outcomes, such as the identification and active addressing of barriers, an increase in self-efficacy, changes in the attitude to exercising on effort, vocational orientation and goal-focus, based on a thorough and holistic theory of change for those programmes. In this process, apparent setbacks or experiences of failure should not be judged negatively per se, as they might represent important adjustments in vocational orientation leading to more sustainable long-term labour market success. The current practice of gathering basic activity indicators, such as programme attendance, and employment status as a final outcome indicator omits the entirety of mechanisms of change that take place in-between those levels and keeps them hidden in a ‘black box’.

Outcome-based subcontracting of labour market programme delivery, as it is common in the USA, Australia and many European countries, is one strategy to shift the focus from programme activities to results. Making payments to providers at least partly conditional on the achievment of employment outcomes gives them more flexibility to tailor their services to participants’ changing needs, and reduces the administrative burden of programme implementation (European Commission Citation2012). However, these approaches also bear the risk of encouraging implementers to strive for short-term gains while minimising intervention costs, with potential detrimental effects for programme quality (Bonvin Citation2008; Sztandar-Sztanderska Citation2009). For example, while some participants need time and careful guidance in undergoing the phases of self-testing and self-knowledge, staff might be incentivised to push for their uptake of any available jobs. Another risk is the differential selection and treatment of participants – whereby more promising candidates would be cherry picked and receive more resources (e.g. ‘cream skimming’, ‘creaming’ and ‘parking’) (Finn Citation2010). These practices are likely to negatively affect the relationship of trust between participants and trainers, reduce motivation and (sustained) progress, and increase programme dropout for more disadvantaged participants. Including indicators relating to certain participant characteristics, job quality/earnings and sustainability of employment in the design of contracts and incentives have shown to be promising strategies to mitigate these risks (Finn Citation2010; Eichhorst and Rinne Citation2015).

Finally, another important aspect that deserves increased attention in both programme planning and evaluation relates to perseverance. Commonly, the vocational status of ALMP beneficiaries in Germany is being assessed at the end of their participation in an intervention, and 6 months later. As part of the results of this study, increased perseverance arose among the themes of change. Evidence from different spheres shows that this is an important attitudinal change with potentially transformative effects for professional and personal success (Duckworth et al. Citation2007; Credé et al. Citation2017). Changes in this trait, among others, and their longer-term effects on retention in subsequently started education or work should be considered when evaluating activation initiatives.

The focus on supply-side factors, i.e. the unemployed individuals and their behaviour, has to be acknowledged as a limitation of this study, which is occasionally criticised in the literature as ‘victim blaming’ (Van Hal et al. Citation2012). While choosing to concentrate on individual processes in this research, the authors recognise the importance of structural labour market features, such as labour demand, equal accessibility and the signalling effects of previous vocational histories, in order to holistically tackle youth unemployment. Furthermore, the exploratory nature of this study does not allow for a quantitative testing of the suggested framework. Further research is needed to assess the applicability of the here presented findings to other contexts.

This paper provides an important contribution to the literature of ALMP evaluation, especially addressing the call for more theory- and mechanism-based evaluation approaches (Astbury and Leeuw Citation2010; Strat et al. Citation2018); as well as to the strand of career development in work psychology, widening the focus of interest towards the increasingly important topic of career avoidance.

6. Conclusion

Tackling the challenge of youth unemployment is a high priority of many governments worldwide. Especially in wealthy economies with well-developed labour markets such as Germany, great emphasis is placed on how to instigate active participation of unemployed youth in work, education or training, preventing or mitigating the rates of vocationally inactive individuals. Activation policies are a widely implemented instrument for this purpose, aiming at driving a behavioural change in their beneficiaries through applying a combination of enabling and demanding elements. However, the detailed mechanisms of change of those programmes have been largely neglected by the social sciences and by the ALMP evaluation literature.

We conducted an in-depth qualitative field study in Germany, analysing the attitudinal and behavioural change processes of unemployed youth over the course of their participation in different activation programmes. The results showed that respondents underwent up to seven phases of change, namely vocational availability, self-testing, self-knowledge, self-confidence, goal-orientation, vocational activity and perseverance. Each of those phases comprised different elements and triggers of change, which were situated partly within and partly outside the intervention domain. The findings suggest that the classic microeconomic search models which build the basis for most activation schemes are not capturing the full complexity of the multi-stage change process, including interconnected and occasionally recursive causal factors triggering the different phases of activation for programme participants. Based on the findings from this study, a 7-stage framework is proposed as basis for a theory of change of activation policies, including aspects of the individual’s career and capability development.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Verena Niyadurupola

Dr. Verena Niyadurupola is a sociologist with a background in evaluation of international development projects. She received her PhD in 2020 with a thesis on the dynamics behind the success and failure of job training for unemployed youth. Her mixed methods research is situated at the intersection of work psychology, education and economics.

Lucio Esposito

Dr. Lucio Esposito is Associate Professor of International Development at the University of East Anglia, UK. He carries out theoretical and empirical research on welfare, inequality and education, using secondary data as well as primary data collected across Africa, Asia, Europe and Latin America. He enjoys engaging in interdisciplinary research and mixed research methods. He is Editor-in-Chief of Development Studies Research.

References

- Andresen, Martin A. and Shannon J. Linning. 2016. “Unemployment, business cycles, and crime specialization: Canadian provinces, 1981–2009.” Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology 49(3): 332–350.

- Arni, Patrick. 2015. “Opening the Blackbox: How Does Labor Market Policy Affect the Job Seekers’ Behavior? A Field Experiment.” IZA Discussion Paper Series (9617)

- Astbury, Brad and Frans Leeuw. 2010. “Unpacking Black Boxes: Mechanisms and Theory Building in Evaluation.” American Journal of Evaluation 31(3): 363–381

- Bell, David N. F., and David G. Blanchflower. 2011. “Young People and the Great Recession.” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 27 (2): 241–267.doi: 10.1093/oxrep/grr011.

- Bonvin, Jean-Michel. 2008. “Activation Policies, New Modes of Governance and the Issue of Responsibility.” Social Policy and Society 7 (3): 367–377. doi:10.1017/S1474746408004338.

- Bonvin, Jean-Michel and Michael Orton. 2009. “Activation Policies and Organisational Innovation: The Added Value of the Capability Approach.” International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 29 (11/12): 565–574. doi:10.1108/01443330910999014.

- Braun, Virginia, and Virginia Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2006): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Credé, Marcus, Michael C. Tynan, and Peter D. Harms. 2017. “Much ado about grit: A meta-analytic synthesis of the grit literature.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 113(3): 492–511.

- Deeke, Axel, and Thomas Kruppe. 2003. “Beschäftigungsfähigkeit als Evaluationsmaßstab? Inhaltliche und methodische Aspekte beruflicher Weiterbildung im Rahmen des ESF-BA-Programms.” IAB Werkstattbericht 1: 1–24.

- Dengler, Katharina. 2019. “Effectiveness of Active Labour Market Programmes on the Job Quality of Welfare Recipients in Germany.” Journal of Social Policy 4 (4): 807–838. doi:10.1017/S0047279419000114.

- Dinan, Shannon. 2019. “A Typology of Activation Incentives.” Social Policy&Administration 53 (1): 1–15.

- Duckworth, Angela L., Christopher Peterson, Michael D. Matthews, and Dennis R. Kelly. 2007. “Grit: perseverance and passion for long-term goals.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 92(6): 1087.

- Ehrich, Malte, Abdul Munasib, and Devesh Roy. 2018. “The Hartz Reforms and the German Labor Force.” European Journal of Political Economy 55C: 284–300. doi:10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2018.01.007.

- Eichhorst, Werner, Maria Grienberger-Zingerle, and Regina Konle-Seidl. 2008. “Activation Policies in Germany: From Status Protection to Basic Income Support.” In Bringing the Jobless into Work - Experiences with Activation Schemes in Europe and the US, edited by Werner Eichhorst, Otto Kaufmann, and Regina Konle-Seidl, 17–68. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

- Eichhorst, Werner, and Ulf Rinne. 2015. “Promoting Youth Employment Through Activation Strategies.” IZA Research Report 65.

- European Commission. 2012. Subcontracting in Public Employment Services: The Design and Delivery of ‘Outcome Based’ and ‘Black Box’ Contracts. Brussels: European Commission.

- European Commission. 2018. Employment and Social Developments in Europe. Luxembourg: European Union.

- Eurostat. 2019. Glossary: Activation policies. Accessed: 12 July 2021. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?

- Finn, Dan. 2010. “Outsourcing Employment Programmes: Contract Design and Differential Prices.” European Journal of Social Security 12 (4): 289–302. doi:10.1177/138826271001200403.

- Fromm, Sabine, and Cornelia Sproß. 2008. “Die Aktivierung Erwerbsfähiger Hilfeempfänger: Programme, Teilnehmer, Effekte im internationalen Vergleich.” IAB Discussion Paper: 1–152. 1/2008.

- Giddens, Anthony. 1998. The Third Way – The Renewal of Social Democracy. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Ginzberg, Eli. 1972. “Toward A Theory of Vocational Choice: A Restatement.” Vocational Guidance Quarterly 20 (3): 2–9. doi:10.1002/j.2164-585X.1972.tb02037.x.

- Glaser, Barney, and Anselm Strauss. 1967. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago: Aldine.

- Harrer, Tamara, Andreas Moczall, and Joachim Wolff. 2020. “Free, Free, Set Them Free? are Programmes Effective that Allow Job Centres Considerable Freedom to Choose the Exact Design?” International Journal of Social Welfare 29 (2): 154–167.

- Hartig, Martina, Eva Jozwiak, and Joachim Wolff. 2008. “Trainingsmaßnahmen: Für welche unter 25-Jährigen Arbeitslosengeld-II-Empfänger erhöhen sie die Beschäftigungschancen?” IAB-Forschungsbericht 6/2008.

- Holland, John L. 1959. “A Theory of Vocational Choice.” Journal of Counseling Psychology 6 (1): 35. doi:10.1037/h0040767.

- Holzschuh, Peter. 2019. “From Job Creation and Qualification Schemes to Activation Strategies: The History of Germany’s Labor Market Policy.” Labor History 60 (3): 203–216. doi:10.1080/0023656X.2019.1533743.

- Hujer, Reinhard, Stephan Thomsen, and Christopher Zeiss. 2006. “The Effects of Short-Term Training Measures on the Individual Unemployment Duration in West Germany.” ZEW Discussion Papers 6–65.

- International Labour Office. 2003. “Active Labour Market Policies”, Governing Body GB.288/ESP/2. Geneva: 1–12.

- Kingston, Sarah, and Webster, Colin. 2015. “The most 'undeserving' of all? How poverty drives young men to victimisation and crime.” The Journal of Poverty and Social Justice 23 (3): 215–227.

- Konle-Seidl, Regina, and Werner Eichhorst. 2008. “Does Activation Work?” In Bringing the Jobless into Work - Experiences with Activation Schemes in Europe and the US, edited by Werner Eichhorst, Otto Kaufmann, and Regina Konle-Seidl, 415–444. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

- Kopp, Joachim. 2019. “Aktivierungsmaßnahmen.: SGB Office Professional, ed. Haufe. Accessed 11 April 2019. https://www.haufe.de/sozialwesen/sgb-office-professional/aktivierungsmassnahmen_idesk_PI434_HI2109833.html

- Maguire, Sue. 2015. “NEET, unemployed, inactive or unknown–why does it matter?.” Educational Research 57(2): 121–132.

- McGuinness, Seamus, Philip O’Connell, and Elish Kelly. 2014. “The Impact of Training Programme Type and Duration on the Employment Chances of the Unemployed in Ireland.” The Economic and Social Review 45 (3): 425–450.

- Mortensen, Dale. 1986. “Job Search and Labor Market Analysis.” In Handbook of Labor Economics, Vol. 2, edited by Orley Ashenfelter and Richard Layard, 849–919. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science

- Nussbaum, Martha, and Amartya Sen. 1993. The Quality of Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Oschmiansky, Frank. 2010. ‘Das Ziel- Und Wirkungssystem Der Arbeitsmarktpolitik.’ Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. Accessed on 11 April 2019. http://m.bpb.de/politik/innenpolitik/arbeitsmarktpolitik/54943/ziele-und-wirkungen?p=all

- Osipow, Samuel H. 1968. “A Comparison of the Theories.” In Theories of Career Development, Edited by Osipow, Samuel H., pp.220–234. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Peck, Jamie, and Nikolas Theodore. 2000. “Beyond ‘Employability’.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 24 (6): 729–749. doi:10.1093/cje/24.6.729.

- Pohl, Axel, and Andreas Walther. 2007. “Activating the Disadvantaged. Variations in Addressing Youth Transitions across Europe.” International Journal of Lifelong Education 26 (5): 533–553. doi:10.1080/02601370701559631.

- Rogers, Patricia J. 2008. “Using programme theory to evaluate complicated and complex aspects of interventions.” Evaluation, 14(1):29–48.

- Saunders, Benjamin, Julius Sim, Tom Kingstone, Shula Baker, Jackie Waterfield, Bernadette Bartlam, Heather Burroughs, and Clare Jinks. 2018. “Saturation in Qualitative Research: Exploring Its Conceptualization and Operationalization.” Quality & Quantity 52 (4): 1893–1907. doi:10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8.

- Savickas, Mark L. 2005. “The Theory and Practice of Career Construction.” In Career Development and Counseling: Putting Theory and Research to Work, edited by Steven D. Brown and Robert W. Lent, 42–70. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

- Sen, Amartya. 1985. Commodities and Capabilities. Amsterdam and New York: Elsevier Science Pub.

- Senghaas, Monika, Carolin Freier, and Peter Kupka. 2019. “Practices of activation in frontline interactions: Coercion, persuasion, and the role of trust in activation policies in Germany.” Social Policy & Administration 53(5): 613–626.

- Spermann, Alexander. 2015. “How to Fight Long-Term Unemployment: Lessons from Germany.” IZA Discussion Paper Series 9134.

- Spinnewijn, Johannes. 2015. “Unemployed But Optimistic: Optimal Insurance Design With Biased Beliefs.” Journal of the European Economic Association 13(1): 130–167.

- Strat, Vasile Alecsandru, Laura Trofin, and Irina Lonean. 2018. “A theory based evaluation on possible measures which increase young NEETs employability.” Proceedings of the International Conference on Business Excellence 12(1): 931–941.

- Super, Donald E. 1953. “A Theory of Vocational Development.” American Psychologist 8 (5): 185–190. doi:10.1037/h0056046.

- Sztandar-Sztanderska, Karolina. 2009. “Activation of the Unemployed in Poland: From Policy Design to Policy Implementation.” International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 29 (11/12): 624–636. doi:10.1108/01443330910999069.

- Tergeist, Peter, and David Grubb. 2006. “Activation Strategies and the Performance of Employment Services in Germany, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom.” In:OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers 42.

- Van Hal, Lineke, Agnes Meershoek, Frans Nijhuis, and Klasien Horstman. 2012. “The ‘Empowered Client ’ in Vocational Rehabilitation: The Excluding Impact of Inclusive Strategies.” Health Care Analysis 20 (3): 213–230. doi:10.1007/s10728-011-0182-z.

- Wanberg, Connie R. 2012. “The individual experience of unemployment.” Annual Review of Psychology 63 (2012): 369–396

- White, Howard. 2010. “A contribution to current debates in impact evaluation.” Evaluation 16(2): 153–164