Early school leaving as a European challenge

Early School Leaving (ESL), also known as Early Leaving from Education and Training (ELET), or more generally as Early Leaving (EL), has become a key focus within Europe in recent years. According to the EU’s definition (European Commission Citation2015), Early School Leaving (ESL) is understood as the percentage of young people (aged 18 to 24) who leave education and training with only lower secondary education outcomes or less, and who are no longer in education and training. Across Europe ESL is viewed as a significant economic and social phenomenon for its impact on the individual, on society, and on the economy at large (Biemans et al. Citation2019; Brunello and De Paola Citation2014; European Commission Citation2015; Gerhartz-Reiter Citation2017).

It is well established that ESL is one of the most concerning educational indicators impacting on young people’s educational, social and labour inclusion. Labour market analysts have argued that youth transitions have become more precarious, complex and conditional within the 21st century, across many of the OECD nations (Symonds, Schwartz, and Ferguson Citation2011) where career paths frequently do not lead to progression, but rather are characterised as what could be termed ‘pinball transitions’ (Brozely, 2017 cited in SKOPE Citation2020:4) where young people ‘ping’ from job to job in a random, incoherent direction. Highlighting some of its most negative impacts, ESL is linked to unqualified workforce and unemployment, difficulty accessing job markets, poverty, poor health, poor self-esteem, poor emotional and psychological well-being, and social exclusion (Archambault et al. Citation2019; Cedefop Citation2016; D’Angelo and Kaye Citation2018; European Commission Citation2015; Gerhartz-Reiter Citation2017). That is, ESL deprives young people, who are early leavers or who are at risk of early leaving, of success in terms of personal development and well-being, job-related financial security and more general participation in society (Gairín and Suárez Citation2012; Olmos Citation2011). Continuation in education and achievement in educational outcomes are therefore fundamental to young peoples’ productive engagement in society, education and work (European Commission Citation2019a; Olmos Citation2014; Olmos and Mas Citation2013, Citation2017; Tomaszewska-Pękała and Wrona Citation2015). Remaining in education and training has, ‘benefits both for individuals and more broadly for societal development and economic growth’ (D’Angelo and Kaye Citation2018, 17), while ESL is one of the principal barriers to achieving equitable societies (European Commission Citation2019b).

Due to the above consequences – and considering that ESL is present among the EU Member States – tackling early school leaving has become a European policy challenge since 2008, when the strategic framework for European cooperation in education and training (known as ET 2020) adopted a benchmark objective to be achieved by 2020: the share of early leavers from education and training in the EU should be not more than 10%; with the exception of 15% for Spain (Eurostat Citation2020).

As part of the Europe 2020 strategy, the 27 EU Member States adopted national targets for ESL. According to latest data from Eurostat (Citation2020), the mean EU ESL rate for 2019 was 10.2%, which (pre Covid-19) could lead us to believe that the achievement of ET 2020 benchmark by Europe countries would have been possible. Nevertheless, interrogating the data, highlights that ESL rate is uneven across State Member (for instance, ESL ranged from 3% in Croatia to 17.3% in Spain). Furthermore, the data indicates that 16 of the Member States’ ESL rates were below their national target, however, the ESL rates of 11 Member States (and the UK) remained above their national target, hence, despite European achievements in improving early leaving rates, it is still a reality and a challenge for Member States, and for Europe as a whole. Indeed, there is good reason to believe that Early Leaving will become an even more prominent issue in the near future. The prominent Skills and Labour Market think tank SKOPE have speculated that post-Covid we should be preparing for a ‘deep and potentially long lasting recession’(SKOPE 2020:1) in Europe and elsewhere, where young people from known risk groups will become the ‘hardest hit’(ibid) in terms of becoming or remaining Early Leavers.

Among other contributions, four papers within this special issue draw upon findings generated from the EU Erasmus+ funded Orienta4YEL project, an international three-year research study that aims to understand and intervene on Early Leaving within 48 educational settings across key regions in five nations in Europe. All five countries involved in the Orienta4YEL projectFootnote1; Spain, Romania, Portugal, Germany and UK – currently a non-member country – remain among these 11 Member States. Focusing on the ESL rates for 2019 for these specific countries, Spain is at 17.3%; (the highest ESL rate in Europe although one of the countries that report the largest reduction – in percentage point terms – in the last five years) and Romania is at 15.3%; (this latest rate for 2019 was 4.0 percentage points higher than the target). These countries were furthest from the ESL benchmark by 2020. The three remaining nations hold comparable ESL rates, closer to the EU benchmark. These include; Germany at 10.3% (which reports increases of less than 1.0 points in the last five years); Portugal at 10.6% (which also reports the largest reduction – in percentage point terms – in the last five years as Spain) and the UK at 10.9% (although the UK uses the comparative indicator of young people not in Employment, Education or Training (NEET) which problematises easy comparison, as will be discussed in paper five of this issue). The differences among the countries involved in the Orienta4YEL study may be due to multiple causes and/or factors. For example, differences could be related to; countries’ smaller/greater levels of social differences and regional disparities; the effectiveness of educational systems in relation to dropout; the nature and effectiveness of dropout control systems; as well as educational systems – especially VET systems – being accused of being somewhat rigid and extremely school-based, skills mismatches.

In summary, ESL presents Europe with the challenge of further investing in tackling early school leaving, in order to reduce the risk of young people’s educational, social and labour exclusion. By no means an exhaustive list, intervention points that have been found to be effective include; improving learning outcomes at school, reinforcing orientation (guidance) mechanisms, increasing adult participation in learning, developing competences for future life and employment, preparing for fundamental change in the skills of its workforce, strengthening young people’s qualifications; improving young people’s labour market prospects, modernising vocational education and training, just to name a few (Cedefop Citation2016; European Commission Citation2019b, Citation2019a).

Theorising the risks to early school leaving

When policymakers speak of young people at risk of ESL, this is often framed in terms of individual competencies, values and orientations, while the sociological literature points to a number of socio-cultural groups or demographic characteristics, associated with young people’s disenfranchisement from society and the labour market. Such work has identified the following groups of young people as being particularly susceptible to Early Leaving; young parents and especially mothers (Maguire and McKay Citation2017; Holmes, Murphy, and Mayhew Citation2019); Traveller/Roma/Gypsy communities (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights Citation2018) and other disadvantaged minorities such as ethnic minorities (Van Praag et al. Citation2018); children, adolescents and young adults who are refugees and asylum applicants, immigrant and migrant children and young people (Koehler and Schneider Citation2019); young offenders (Bäckman et al. Citation2014); young people with some types of special educational needs and disabilities (Batini et al. Citation2017), including those with social, emotional and mental health difficulties (Rodwell et al. Citation2018; Holmes, Murphy, and Mayhew Citation2019); children identified for child protection, as well as those in care (Dickens and Marx Citation2020); young carers (Sempik and Becker Citation2014); children from service families; or children in poverty (Schoon Citation2014). While not an exhaustive list, the range of young people at risk situates an Early Leaver profile as conflating with more general indicators of vulnerability; taking into consideration the complexity of this concept that should be understood within a holistic, social-relational and social-ecological perspective (Olmos Citation2011). Vulnerability is a multidimensional and multifactorial concept and the condition of vulnerability – as a product of interrelated dimensions and factors – can disrupt individuals, social groups or communities (leading to problems for young people in developing their personal well-being and participating in social, economic, political, educational and cultural contexts) determining their sense of belonging and integration in the society (Gairín and Suárez Citation2014; Olmos Citation2011).

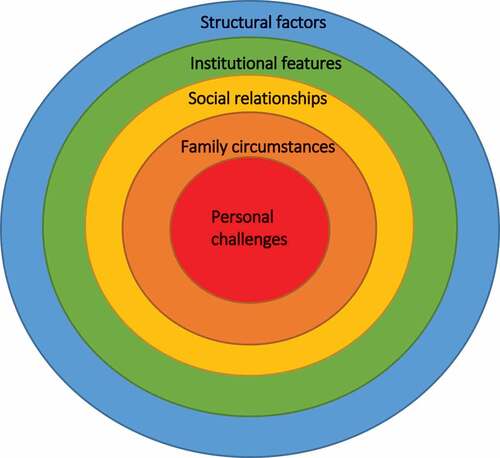

Consequently, one of the central challenges in developing a comprehensive approach to studying Early Leaving is that it requires a framework capable of capturing the broad spectrum of complexity for a near intractable issue. Though the last few decades of educational research into Early School Leaving and educational achievement for disadvantaged children have highlighted the cumulative nature of risk factors, there is limited work in relation to holistically theorising these risks. Whilst research has attempted to outline the risks of Early Leaving (Cedefop Citation2016; European Commission Citation2015, Citation2019b; González-Rodríguez, Vieira, and Vidal Citation2019; Olmos Citation2014; Salvà-Mut, Tugores-Ques, and Quintana-Murci Citation2018; Van Praag et al. Van Praag, et al., Citation2018) the theoretical focus has frequently been on (dis)/engagement (D’Angelo and Kaye Citation2018; Olmos, Mas, and Salvà Citation2020; Salvà-Mut, Thomás-Vanrell, and Quintana-Murci Citation2016; Tomaszewska-Pękała, Marchlik, and Wrona Citation2019; Wang and Amemiya Citation2019). What is still missing, however, is a theoretical perspective which can account for the social structuring of disadvantage across the key domains that inform school–work transitions. To address this gap in knowledge, we sought to develop a conceptual schema in which to map the multiple levels of human existence, including the; psychological, socio-cultural, material, environmental, structural and political arenas. By combining Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation1979) ‘ecological’ model with Brown’s (Citation2014) ‘binds of poverty’ theory, we devised a 5-tier model, which captures the discrete barriers or opportunities young people face in their pursuit of securing good life chances.

In this introduction, we begin by outlining Bronfenbrenner’s ‘ecological’ model and its strengths in relation to theorising the external forces that shape young people’s development. We then introduce Brown’s ‘binds of poverty’ theory, which complements (and addresses a limitation in) Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model (from the perspective of Early Leaving) by capturing the individual barriers disadvantaged young people face. From here, we integrate these two models into our 5-tier framework of risk for Early Leaving, unpacking the dimensions of personal challenges, family circumstances, social relationships, institutional features of school/work, and structural factors. We conclude with an outline and structure for this Special Issue.

A contextual analysis of child and youth development: Bronfenbrenner’s ecological system’s theory

Urie Bronfenbrenner’s work has attempted to theorise how the different aspects in children’s lives affect their development by adopting an ecological approach. As a Russian-born psychologist raised in America, he was arguably the first to integrate the complex layers of contextual influences; ‘from immediate through to social policy and culture – and the nature of their interactions with each other in the context of human development’ (Grace, Hodge, and McMahon Citation2017, 5–6). In the late 1970s (Bronfenbrenner Citation1979) Bronfenbrenner termed his developmental model, ‘ecological systems theory’, which he later developed over the period of three decades. In reaction to the dominance of developmental psychology and its emphasis upon the biological and universal stages of children’s development (e.g. Piaget Citation1934, Kolhberg Citation1984), Bronfenbrenner sought to incorporate a theorisation of the environmental and interpersonal impacts upon the child in directing the locus of attention to the child’s surroundings in which s/he is raised. It is dynamic in the sense that the ecological approach aims to conceptualise the constantly shifting social, physical and psychological terrain that the child concurrently navigates (Tudge, Gray, and Hogan Citation1997). As a holistic framework for directing a social science approach to childhood, the ecological system’s model has been applied across a number of fields of practice including Health (Aber et al. Citation1997), Social Work (Ungar Citation2002) and Youth Criminal Justice (Steinberg, Chung, and Little Citation2004) and Education (O’Toole Citation2016).

At the heart of Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation1979) model is the child as an individual in terms of his/her physiological and cognitive profile. Surrounding the individual are four key ‘levels’ that Bronfenbrenner (Citation1979) identified as nested layers of concentric circles indicating discrete contexts through which to construe the environmental developmental interaction, upon the child (see ). Each of these is located at a proximal range of distances from the young person’s daily lived experiences, and are termed, respectively, the micro, meso, exo and macro systems.

Figure 1. A visual model of the four levels to Bronfenbrenner’s ecological system’s theory.Footnote2

The sphere representing the settings which are situated at the closest proximal distance to the individual child, Bronfenbrenner defines as the ‘micro system’. He describes this level as;

[A] pattern of activities, roles and interpersonal relations experienced by the developing person [child] in a given setting with particular physical and material characteristics (p22).

Analysis of the micro level refers to the local-level physical and material settings in which the child participates in their routinised daily lives such as; the family home, school, the homes of friends and extended family, and, community-based religious or youth groups. Through the norms, values, routines and interpersonal relationships encountered in these core settings, the contextual impact of the micro level draws attention to the key institutions in which the young person is raised as instrumental in constructing psychological, ethical, and ideological dispositions and ontologies. For those at risk of Early Leaving this could include the forming of pro- or anti-schooling values, education and labour market aspirations.

The second sphere of Bronfenbrenner’s model, he names the ‘meso- level’. While the Micro-level refers to singular settings, Bronfenbrenner (Citation1979) defines the mesosystem as;

[T]he interrelations among two or more settings in which the developing person actively participates such as, for a child, the relations among home, school and the neighbourhood peer group; for an adult, among family, work and social life (p25).

This recognises the child as a fundamentally social being, and therefore the importance of considering values, practices and relationships that occur within the multiple social spheres in which the young person participates. This contextual lens recognises that values, norms and relationships are not constructed in a vacuum, and the interaction between different micro-settings can lead to both inclusion and exclusion in an educational sense, particularly through the alignment or discordance of values, norms, routines and practices between adults across the different settings. For example, the routinised and regulatory systems of schooling, such as rigid timetables, listening and engaging in didactic teaching, limited movement in the classroom, and individualised working, may be experienced variously by children of different home backgrounds. For the young carer used to significant autonomy and physical activity, schooling rhythms may be experienced as alien and discordant to their home life, while for the middle-class child used to set family mealtimes, a scheduled homework hour and structured extra-curricular activities, school is experienced as a familiar setting and values aligned environment, contributing to a sense of belonging and participation in schooling.

While the first two levels emphasise the environmental influences of the people and places in which the child interacts, the exo-system points to the influence of arenas that indirectly affect development. This includes;

… settings that do not involve the developing person as an active participant, but in which events occur that affect or are affected by what happens in the settings containing the developing person (p25).

The exo-level developmental context also applies to physical and material ‘local’ and bounded places, the key difference is that exo-level settings indicate those in which the child is not directly present as a social actor. Bronfenbrenner points towards, ‘the parent’s place of work [or job centre] a school class attended by another sibling, parents’ networks of friends [and] the activities of a local school board’ (p25). For the young person from a low-income family parental job loss could thwart their plans to enter higher education on leaving school in place of securing employment to contribute to the family income – studies as Cedefop (Citation2016) evidence this risk factor for early leaving.

The final level of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological system’s theory refers to ideological context in the form of socio-cultural systems;

The macrosystem refers to consistencies, in the form and content of lower-order systems (micro-, meso, and exo-) that exist or could exist, at the level of the subculture or the culture as a whole, along with any belief systems or ideology underlying such consistencies (p26).

In expanding on this he points to the broad difference in educational settings,- such as the school,- that exist between two nations (France and the US), which he refers to as a ‘set of blueprints’ (ibid) that organise and govern society. For young people at risk of Early Leaving the macro level includes educational, economic and labour market policy on a national level. However, the macro level also applies to sub-national units of socio-cultural organisation, what he refers to as ‘intrasocietal contrasts … [delineated by] … socio-economic, ethnic, religious, and other sub-cultural groups, reflecting contrasting belief systems and lifestyles, which in turn help to perpetuate the ecological environments specific to each group’ (p26). For example, national attitudes towards Traveller and Roma communities can frame a schooling ethos that fails to recognise Traveller culture, leading Traveller children to feel excluded and even experience bullying and persecution in school, therefore affecting the child’s educational outcomes and any aspirations to continue into higher or further education.

The strength of Bronfenbrenner’s theory for informing a framework to conceptualise the risk factors to Early Leaving, is in foregrounding the various contextual arenas that frame structural, social and cultural barriers for young people. However, it is important to recognise that the influence of the various micro, meso, exo and macro level contexts in creating barriers and opportunities for children are not absolute. Here, Bronfenbrenner (Citation1979): is careful to situate the child as an active mediator of these environmental influences;

A critical term in the definition of the micro system is experienced. The term is used to indicate that the scientifically relevant features of any environment include not only its objective properties but also the way in which these properties are perceived by the persons in that environment (p22).

For example, a child’s special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) such as profound significant physical or sensory impairment, will impact upon parents’ decisions about schooling and the school’s preparation and provision for post-schooling options. Similarly, the child can challenge and direct the environmental influence, as reflected in the English SEND code of practice (2014) which puts an emphasis upon the child’s choice and wishes over their educational provision. Furthermore, through his concept of ‘proximal processes’ (Bronfenbrenner Citation1979) Bronfenbrenner acknowledges that the child will orientate towards those settings, which chime with their own characteristics and ontological approach, and therefore influence, particularly, their own social settings.

In conclusion, Bronfenner’s work recognises the personal, while emphasising the environmental, political and relational barriers and opportunities for development. However, as we advanced earlier in this paper, Bronfenbrenner’s theorising is limited as a universal model for child and young people development, because it arguably misses the specific barriers or binds to education experienced by educationally disadvantaged children and young people, such as groups highlighted previously as at risk of Early Leaving. Within the early school leaving framework, it is necessary to consider both the disadvantages of children and of young people (Gairín and Suárez Citation2012) because barriers or binds experienced by educationally disadvantaged children could explain the problems that early leavers face. In order to focus our conceptual model more squarely upon the circumstances and challenges related to Early Leaving (e.g., schooling, educational and training for key groups of young people), we sought to integrate Bronfenbrenner’s insights with the theoretical insights from research into the schooling experiences of children facing material and economic hardship: Brown’s educational ‘binds’ of poverty (Bronfenbrenner and Morris Citation2006). This is particularly pertinent in view of recent work that has highlighted that young people from disadvantaged backgrounds are twice as likely to be NEET (Gadsby Citation2019).

The educational binds of poverty

While Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation1979) model recognises the psychological impacts of contextual forces upon the child’s development, the onus of his framework is upon the external social and structural forces. In contrast to Bronfenbrenner’s model, Brown’s framework was informed by a child-centred lens in following children over the course of five years including their transition from primary to secondary school. Considering children’s experiences of school as viewed through their own eyes enabled a close analysis of the actions and narratives children employed in attempt to make their school life meaningful. Drawing from over 30 years of qualitative research into the experience of school life for children in poverty,- including her own empirical research, -Brown (Citation2014) developed the ‘educational binds of poverty’ as a heuristic to analyse and explain children’s educational challenges. The concept of a ‘bind’, points to a particular form of barrier or challenge that obstructs educational success. In contrast to the policy assumption that children are unaware of or passive to such challenges, the ‘bind’ concept signals children’s agency in confronting and wrestling with the challenges they face, often through employing creative and ingenious strategies. Children’s efforts to break free of the bind serve only to make it more constrictive, in provoking tensions and trade-off in children’s experiences of school, such that while they may find ways of navigating social and inter-personal trajectories, this often comes at the expense of success in formal educational outcomes. Brown’s early work identities four binds in particular as the most difficult to circumnavigate, while more recent work has reflected on the prevalence of a fifth bind (Brown and Dixon Citation2020). Each of these four binds will now be reviewed.

The first bind that Brown identifies concerns the ‘the material necessities conducive to health and happiness [which are] are so compromised’ (p23) for children in poverty such as ‘poor health, poor housing, and fear and anxiety over unemployment, crime, and family income material’ (ibid). These influences have a direct impact on children’s readiness to learn in that children are more likely to start their day tired, hungry and anxious. There is also an indirect impact of material hardship. Examples may include: the perceived shame or embarrassment triggered by wearing ill-fitting or broken school uniforms; lacking the resources and commodities such as fashion, music and sport prized in youth culture across first world nations of Europe; and self-imposed exclusion from not participating in paid for school trips, residentials, or other social and extra-curricular activities.

Bind two refers to the ‘the reasons as to why, and ways in which, schooling pedagogies are alienating for children in poverty’ (Brown Citation2014, 28) such that there is a disjuncture between children’s experience of home and schooling cultures such as ‘the norms, routines, language used and expectations of children and adults in school, and to what extent these mirror or are in contrast with those out of school’ (ibid). This bind is well illustrated through the work of Annette Lareau (Citation2000) who found that the cultural advantage of participation in extra-curricular activities transferred into the social and interpersonal resources to achieve in school for middle class children;

[Middle class children] spent a great deal of time ‘performing’ in situations similar to school; as for example, at soccer practice, they lined up, followed directions, performed tasks upon the request of adults and demonstrated their skill in a public setting (p168).

In contrast, she found that those from low-income families were more likely to spend their free time caring for family members, carrying out domestic duties or participating in solitary unstructured leisure time, leading them to find the rigidity of school routines to be stifling to their autonomy.

Bind three refers to the social impact of poverty and its effects in constraining and promoting friendship cultures that vary in their orientation to schooling values. This indicates in that while finding it harder to access pro-schooling peer groups, many children in poverty are particularly reliant on their in-school friendships in order to generate a sense of self-value and inclusion in being largely socially, culturally or emotionally disenfranchised due to associated aspects of their vulnerability (i.e. being in-care, young carers, young offenders, young parents).

Bind four is particularly relevant for Early Leavers in signalling the educational, social and emotional impacts of irregular school transitions. Children from low-income backgrounds have been found to be twice as likely to experience turbulence due to labour market insecurity, rising house prices, austerity welfare measures, and policy impositions (i.e. availability of foster care, land rights for Traveller communities). Recent research has indicated that the impact on educational outcomes face is cumulative with subsequent school moves (RSA Citation2013).

In recent work, Brown has also speculated on the rising emergence of a fifth bind- the mental health bind of poverty in acknowledging the growing prevalence of mental health issues among school children in nations of the global north (Brown and Dixon Citation2020). Statistical evidence has suggested that approximately one in four children now experience mental health difficulties, while policy analysis has suggested that one of the reasons for this may be the institutional factors of schooling such as the impact of performative pressures and budget cuts on instructional mechanisms and children’s sense of anxiety and stress in school.

In summary, these five binds capture a range of barriers and hardships young people in schooling and education can face. As such, Brown’s ‘binds of poverty’ provide a suitable framework which can focus on the individual challenges Early Leavers contend with, as viewed through young peoples’ own experiential and conceptual lenses. In the following section, we integrate this more ontological perspective alongside Bronfenbrenner’s broader ecological perspective to develop a holistic framework of the risks to Early Leaving.

Integrating ‘ecological systems’ & ‘binds’ theory in developing a typography of risk to EL

While an ecological model (Bronfenbrenner Citation1979) can help to isolate the various contextual arenas through which risks are produced, a more focused lens upon children’s experiences of educational advantage can enable a more nuanced analysis of the processes through which the various contextual settings create these risks. Taken in conjunction, these theories led us towards an understanding of the various material, cultural, social, institutional and policy factors that frame distinct albeit inter-related risk factors to Early Leaving. In integrating the insights from these two theoretical perspectives we strived to develop a framework in which to categorise and organise the various risks to Early Leaving, which was sufficiently comprehensive to the empirical literature into Early Leaving, while amenable to conceptual distinction in a way that practitioners could engage with and apply. It was, therefore, important to avoid esoteric labels (i.e. micro, meso and exo level). As such we developed a framework of five distinct categories of risk factor; personal challenges, family circumstances, social relationships, institutional features of school and work, and structural factors of economic disadvantage, national policy, and the educational system.

Following Bronfenbrenner, we understood the various spheres to be nested and inter-dependent. We have organised each of these levels in terms of their proximal and temporal influence on the young person (see ). We are earnest to emphasise that in line with Bronfenbrenner and Brown, we recognise the social, structural and external constraints that each sphere exerts on the young person. However, we also recognise the agency with which young people will negotiate and navigate the risks presented in each of these spheres. We follow the ‘bind’ allegory (Brown Citation2014) in recognising the young person as invariably cognisant of the challenges they face in the pursuit of good life chances, and far from passive in their engagement with them. This enables us to consider the personal and agential risks to EL from a position that avoids a deficit model judgment on young peoples’ thoughts, beliefs and behaviours, as well as those of their families, peers and teachers and professionals. In contrast, we view the ontological dimension to these effects as both trade-offs and buffers which enable young people and those around them to ‘get by’ within very challenging circumstances. To illustrate this point, we may consider the ‘personal’ risk of ‘low aspirations’ which policymakers frequently point to as both the cause and solution to good life chances for young people. The policy view of ‘limited aspirations’ or low-expectations as inherently problematic fails to respect its function in buffering the disappointment, injustice and impact to self-worth, where compounding evidence highlights the uncertainty by which aspirations to succeed in higher education or the labour market can be realised.

Figure 2. A model for conceptualising the categories of risk factors to early leaving.Footnote3

Personal challenges

The first category of risk factors for Early Leaving we label ‘personal challenges’. In being positioned at the centre of the model this dimension of risk reflects the individual aspects of the child Bronfenbrenner’s points to, as unique to the physiological, psychological, emotional and cognitive characteristics of the child. As a category of risk, ‘personal challenges’ refers to the challenges related to the child’s personal circumstances that present barriers to educational and labour market trajectories. This include a number of aspects including:

health and ability (e.g. Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND), Mental Health difficulties (SEMH);

emotional and ontological aspects leading to a negative impact upon self-concept (e.g. low self-esteem and self-confidence, low aspirations, motivation and expectations, negative academic perception, fear of failure, stress and anxiety, low resilience);

aspects related to significant experiences or events (irregular school transitions, childhood abuse or neglect, trauma, denial of personal agency, isolation,)

behavioural aspects related to the young person’s responses to experiential challenges (e.g. absenteeism, communication difficulties, difficulty in trusting others, disengagement, school exclusion and young offending).

As is evident from this description, personal challenges include individual factors the child is born with (e.g. abilities), or acquires (mental health difficulties), but they also refer to the young person’s ontological outlook. The young person’s view of the world may be internally held, but it is also a product of the multiple contextual circumstances imposed or mediated by the other four contextual risk categories around the child. For this reason, personal challenges are situated at the very heart of the model because the ontological dimension to this risk category can be understood as a mediator for and expression of challenges within all other categories (e.g. low self-esteem, negative learner identity) which affords these aspects an overarching status and apposite point of intervention (see paper 7 of this special issue).

Family circumstances

The second category of risk applies to the family circumstances pertaining to the young person. We position this level next to the personal one in representing the first external sphere of challenge the child must navigate, in recognising the family as the primary social institutional the child usually experiences and the influence of which will extend through the lifespan. Following Brown (Citation2014), family circumstances include:

material circumstances (e.g. being raised in a low-income or workless household, young person having to support the family through caring or economic means);

cultural factors (e.g. family aspirations and expectations, parental value of education,)

social circumstances (e.g. dysfunctional family relationships and parenting difficulty)

physical, mental and emotional needs and availability of family members: (low family support, experience of alcohol/substance abuse in the family)

In being careful to avoid judging parents and families, we also recognise that risks that fall-under ‘family circumstances’ do not confer blame or responsibility on young people’s circumstances. In contrast, the complexity of these challenges recognises the difficult circumstances in which parents are raising their children, and we take the perspective that the significant majority of parents care about their children and want the best for them. We therefore highlight the nature of this risk category as being shaped by the other categories (for example parents’ aspirations for their child may be affected by the personal risk categories of the child’s SEND and SEMH needs).

Social relationships

The third category of risk we term ‘social relationships’, that we position at the second layer of separation from the young person. The influence of social relationships are particularly marked during adolescence (Reimer Sacks Citation2014) as a period in the life span where the young person is looking outside of the institution of the family in defining themselves as independent social actors. In playing a central role within both Bronfenbrenner’s and Brown’s theory the social and emotional dimensions of children’s lives are seen to be as underpinned by their relationships with those around them. For Bronfenbrenner, it was the through the child’s emotional attachments with other people that the microsystem wields its influence on the developing child (Bronfenbrenner Citation1979). For Brown (Citation2014) each of the four binds exerted a negative impact on children’s friendships and peer groups. The ‘Social relationships’ category of risk refers to relational challenges brought about through all types of relationships outside of the family including;

adults in a position of authority in school, work and training such as with employers and teachers (e.g. not feeling cared about by teachers, low expectations from employers and teachers);

the influence of the peer group (e.g. bullying, gang intimidation, peer pressure to take drugs, alcohol and smoke, low peer group expectations for the future)

friendships (e.g. not having friends, anti-education friendship cultures, poor friendship management skills, losing or difficulty retaining friends)

adults working in a support capacity (e.g. poor relationships with mentor, tutors, or learning support advisors).

threats from engagement in online or mobile technology and social-media platforms (e.g. cyber bullying, obsessive online gaming, vulnerability to grooming and social media pressure).

As with the previous categories, risks produced within ‘social relationships’ are interrelated with the other risk categories. For example, familial interactions with the school can impact on how teachers and other educators can perceive and engage with the young person, which are also shaped by personal factors such as the child’s ability and aptitude in school. Furthermore, the early friendships the child makes may be influenced by the friends of parents, as well as the school or neighbourhood in which the family home in situated. This category recognises that while we may be able to ‘choose our friends’ where we ‘can’t’ choose our families’, young people’s friendship choices and relational orientations are not unconstrained and must be reciprocated. As Brown’s (Citation2014) theory highlights, the friendship groups that children in poverty are able to gain access to are less likely to be pro-schooling, and are subject to gender and poverty mediated processes of inclusion and exclusion.

Institutional features of the school and work place

As the fourth sphere of our model () ‘institutional features of school and work’ recognise the school (college, VET or non-formal educational setting) and work place as micro-level cultural and social systems (Bronfenbrenner Citation1979) that provide structure and meaning to the daily life worlds that young people inhabit. Risks that fall under this category include:

Material or environmental aspects (e.g. classroom layout not inclusive, uncomfortable learning/work spaces, class or team size too big, absence of ‘safe spaces’ to access when needed.)

Organisational policies: (e.g. poor behaviour management or wellbeing systems, exclusion and attendance policies)

Norms regarding unofficial’ social regulatory systems on expectations and behaviour (e.g. institutional rigidity, relegated to the corridors to work during lessons).

Level and nature of support available (e.g. limited teacher resources or time, lack of career, personal, or academic guidance, lack of identification mechanisms for targeting support).

Risk factors under the ‘Institutional features of school and work’ category are inter-related with the other risk categories in ways such as; the personal needs of young people mean that they are more or less able to fit in with the social organisational structures of schooling, i.e. children with mental health difficulties may find it difficult to access full-time schooling; bullying from the peer group and exclusion from friends make young people more vulnerable to weakly defined or inconsistent behaviour management systems; a lack of routine or multiple demands on the young people within the family home may make it difficult to comply with highly structured and time-monitored routines of the school or workplace.

Structural factors of economic challenges, national policies, and the educational system

The final risk category we identify is that of structural factors of economic disadvantage, national policy and the education system. While there are different ways of conceptualising structural factors, our framing accords with the core components identified by the European Commission Citation2019b), which include political leadership and stability; labour market policies; socio-demographic factors, migration and population change; the legal framework for compulsory education; governance arrangements within education systems; equity and inclusion policies; quality and availability of early childhood education and care; and, quality of teaching and continuing professional development programmes.

As the category most far removed from the individual, ‘structural factors’ point to the external influences on the child that operate outside of their daily life worlds. This level is akin to Bronfenbrenner’s ‘macro’ level sphere in which he recognises that ‘the individual’s own development life course is seen as embedded in and powerfully shaped by conditions and events occurring during the historical period through which the person lives’ (Brofenbrenner Citation1995, 641). As the name suggests there are three key dimensions to this category:

Economic challenges at the local, regional or national level (e.g. crisis in funding to public services, and local authorities and schools, poor regional infrastructure and public transport services,)

The impact of national policies concerning school, education and work (e.g. raising the age of compulsory education and training to 18; changes in the grading systems of national examinations, requirement for post-16 maths and literacy, resourcing for national mechanisms to track Early Leaving)

Aspects of the educational system (e.g. exam pressure and performance targets, performance pressure on teachers, transition from school to vocational education and training (VET))

As with the other risk categories in this model ‘structural factors’ are closely interrelated with each other category. ‘Structural factors’ are positioned as the sphere furthest from the individual. This is because while they may exert an influence on the risks that fall under institutional, social, familial and personal challenges, this category of risk is the least likely to be impacted by the other factors, especially that of personal challenges, given the broad reach of risk factors that fall under this category, as well as their detachment from the effects caused on individuals, groups and individual institutions. Accordingly, an example of how structural factors may shape institutional factors can be seen in the effects of national performative and accountability requirements upon school policies and systems, for example, concerning the available resources schools have at their disposal and the working conditions of school staff. Structural factors can also be seen to shape risks raised within the social relationships risk category, for example, in shaping the learning/training cohorts in which young people are placed (i.e. regarding the requirement to continue in education and training until the age of 18). Structural factors can be seen to frame risks posed within familial circumstances through welfare provision, and labour market conditions and the opportunities and resources available to family members (e.g. insecure work contracts causing precarious residential and financial status). Risks that are produced in the Personal challenges category are also influenced by structural factors,for example, with regards to the resources and requirements specified by the government and policy influencing authorities (i.e. support for SEND in England is dependent upon reaching threshold criteria to be assigned an Education, Health and Care plan).

We argue that our model provides a valuable and original contribution to the literature on Early Leaving as a holistic framework that captures both individual and contextual aspects of young people’s lives, in terms that are readily accessible to practitioners. We believe this has value for planning and developing intervention strategies, in that while actions to tackle Early Leaving may be frequently targeted at single categories of risk (personal, family, social, institutional or structural) it is important to consider the ramifications and limits of such efforts within the context of the other categories of risk as a whole. The close interconnection between the micro categories of risk (family, social, institutional) and in their impact upon the personal challenges that young people face, points to the importance of individual support in the form of guidance that recognises that young people are concurrently navigating social, familial, and residential trajectories alongside their planned educational, training, and work journeys. However, efforts to target support at the micro level of family, social and institutional contexts must be considered alongside the overbearing influence of structural factors. This highlights the importance of political will and resourcing as fundamental in complimenting the dedicated work of practitioners who work in the micro settings of the home, school and community.

The framework advanced in this paper provides the underpinning structure that unites the following papers. Each of the empirical, and theoretical contributions in this special issue will signpost the respective, personal challenges, family circumstances, social relational, institutional features of school/work, and structural factors, where they apply to the various national contexts, in understanding and intervening on the risks to Early School Leaving in Europe.

Outline of the special issue

The conceptual framework for researching the risks to Early School Leaving that we have outlined above reflects the theoretical approach to researching ESL as part of the E.U. commissioned international study; the Orienta4YEL project.

The Orienta4YEL project, which is ongoing at the point of publication, is a three year study aiming to develop, implement and evaluate innovative methods and practices focused on mechanisms of orientation and tutorial actions to foster inclusive education for young people, who are at risk of - or affected by - early leaving, in formal and non-formal educational contexts. The goal is to provide educational institutions and involved educators across five European countries with a set of strategies to support their work in tackling young people’s risk of early leaving in each one of their specific contexts.

The first phase of the Orienta4YEL project (Work Package 2) involved developing the diagnostic and associated qualitative research tools used by project partners to research the regional, national and international risk factors to early leaving and the measures used to tackle early leaving within 48 educational settings across the five involved nations (Spain, Romania, Portugal, Germany and UK). This database of 144 interviews and focus groups with 711 educational stakeholders (members of the school leadership team and administration, educators/teachers/trainers and students/young people) provides the evidence base for four of the empirical papers included within this special issue. Along with this focus on understanding support mechanisms of ESL in-depth, the Orienta4YEL project also aims to establish learning networks about tackling early leaving through mechanisms of orientation and tutorial actions focused on prevention, intervention and compensation measures and identify the aspects of effective leadership in educational institutions that foster educational and social inclusion of young people.

The framework that we present in this paper also forms the structure by which we have organised this special issue; as such, the articles authored by the Orienta4YEL contributors unpack a range of issues in relation to our model; personal challenges, family circumstances, social relationships, institutional features of school/work, and structural factors.

Four of the papers included in this special issue engage in a comparative analysis defined in Green’s (Citation2003) terms as concerned with, ‘analysing the pattern of relationships between characteristics of societal or collective entities, whether they be at national or other levels’ (p92). In his seminal paper canvassing the future for comparative research in an era of globalisation, Green defends a focus upon ‘national’ education systems, arguing that unlike in higher education and despite the encroachment of privatised market forces, ‘school systems are still very national institutions’ (91). Accordingly, the three empirical papers included in this special issue place the national systems of education at centre stage in their analyses. However, mindful of his injunction to consider further units of analysis, these papers also reflect on the contextual specificities of the regions under investigation. Indeed, this is the core ambition of the policy analysis in paper five with respect to the four nations of the UK. In the two decades since Green’s paper, however, we have witnessed Whitty’s (Citation2002) predictions becoming reality regarding the privatisation of national schooling systems, in order to meet what Green argued to be national governments’ ‘double-bind’ to both ‘raise the demand for skills and qualifications whilst reducing state capacity to meet them’(p90). One of the key lenses guiding the empirical patterning of societal relationships’ is therefore the unique as well as the common ways in which neoliberal policymaking has shaped all five categories of risk for young people in contributing to the barriers they face.

In paper one by Brown, Diaz Vicario, Costas Batlle, and Muñoz Moreno, the framework for understanding the risks to Early Leaving advanced in this introduction is applied to data from the Orienta4YEL study in conducting a comparative analysis of Spain and England. In considering Early Leaving in the context of a high national level of EL (Spain) and low relative EL (England) key commonalities and differences in the data patterns are reflected upon according to the key risks that emerges within each of the five risk categories. Particular attention is given to the relationship between the risk category of Family circumstances, which emerged as the most significant risk category in Spain with the risk category of Structural factors, which emerged within England.

Paper two comprises a second empirical comparative analysis of Early Leaving in the context of Germany (a nation with low EL rates) and Romania (a nation with high levels of EL). Also drawing upon data collected as part of the Orienta4YEL study these two nations are apposite to consider in that familial circumstances and personal challenges emerged as the most significant risk factors in both nations. However, as the paper outlines there are some key differences in terms of key groups identified, as well as cultural, social and political factors which mediate the interrelationship between personal challenges and family factors, as well as with other risk categories developed within the theoretical model of risks to EL outlined in this introduction.

Paper three by Savvides, Mangas, Freire, Lopes, and Milhano is the third empirical papers to draw upon data from the Orienta4YEL project in the comparative analysis of Portugal and England, two nations with comparative Early School Leaving rates. Here, the focus is particularly upon the risk category of Structural factors, which emerged as a highly prominent category within both countries and particularly in the inter-relationship with institutional features of the school and work-place. This is significant in order to understand better the interrelationship between structural forces such as government policies and their impact upon institutional features of the school/work place. This analysis illuminates the knock-on impact of key risk factors across the different categories, as well as the similarities and differences in the risks that fall within these categories across two national approaches.

Paper four written by Psifidou from the European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training (Cedofop) considers the methodological challenges to researching and tackling risks to Early Leaving from the perspective of lifelong guidance in EU. It examines how national policies and practices of lifelong guidance in EU Members States support learners at risk and early leavers. The paper discusses and analyses information comparatively and reflects on: (a) what are the key characteristics of lifelong guidance policies and practices in Europe to support learners at risk and early leavers from education and training, and (b) what are the information gaps that need to be addressed in the EU future policy instruments and actions.

Paper five takes an in depth look at structural factors, in the form of national policy approaches to Early Leaving. Drawing on a recent policy review Maguire explores the Early Leaving measures used across the UK, which in contrast to the other nations in Europe have focussed upon reducing the number of young people who are NEET (Not in Employment Education or Training). Notwithstanding this focus, Maguire considers variations that exist between the four UK nations (England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland) in considering the significance of compulsory education age requirements; capturing and measuring the number of young people who are defined as NEET and crucially, equality of access to support and intervention. This analysis reveals that the four UK nations are increasingly pulling in different directions in terms of policy and practice and why it matters with regards to how Early Leaving is measured and acted on in Europe.

Paper 6 takes a comparative analysis in drawing upon empirical research within France and the UK with respect to a significant, and frequently overlooked group of Early Leavers; young women. Specifically, Guegnard considers the position of young women in the UK and France who are defined as not in education, employment, or training (NEET) and economically inactive. The experiences of young people,- and especially young mothers,- who are economically inactive in Europe are an under-researched group in the field of ESL, and in examining the unique challenges faced by this group, Guegnard’s paper provides a valuable lens upon the barriers to accessing employment that Early Leavers can face.

Finally, paper seven by Olmos and Gairín concludes the special issue with a discussion of the overall dataset across the five nations involved in the Orienta4YEL project. Empirical data is presented that supports the case for a focus upon the risk factors of personal challenges and social relationships as an appropriate mechanism for intervening on Early Leaving. The prominence of those two risk factors speaks to the purpose of the Orienta4YEL project: to identify orientation and tutorial actions which can be employed in educational settings to tackle Early Leaving. Consequently, this is an apposite paper to conclude the special issue given the risks of personal challenges and social relationships a) can be effectively addressed through orientation and tutorial actions, and b) are key mediators of the risks produced in the other three categories (family circumstances, institutional features, and structural factors).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1. Erasmus+ Orienta4YEL Project, Supporting educational and social inclusion of youth early leavers and youth at risk of early leaving through mechanisms of orientation and tutorial action. Project number: 604501-EPP-1-2018-1-ES-EPPKA3-IPI-SOC-IN, led by the EDO group from the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB).

2. The most frequently visited visual illustration of Bronfenbrenner’s model on google.co.uk search engine Available;https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ecological_systems_theory Accessed 22 June 2020.

3. Model produced as part of the Orienta4YEL project in developing the research diagnostic tools that underpin Work package 2. Published in press for this first time here. A research video developed for the purpose of training educators supporting young people at risk of Early Leaving is available here: https://vimeo.com/431748528

References

- Aber, J. L., N. G. Bennett, C. Dalton, and Jiali L. Conley. 1997. “The Effects of Poverty on Child Health and Development.” Annual Review of Public Health 18 (1): 463–483. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.18.1.463.

- Archambault, I., M. Janosz, M. Goulet, V. Dupéré, and O. Gilbert-Blanchard. 2019. “Promoting Student Engagement from Childhood to Adolescence as a Way to Improve Positive Youth Development and School Completion.” In Handbook of Student Engagement Interventions. Working with Disengaged Students, edited by J.A. Fredricks, A.L. Reschly, and S.L. Christenson, 13–29. Academic Press. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-813413-9.00002-4.

- Bäckman, O., F. Estrada, A. Nilsson, and D. Shannon. 2014. “The Life Course of Young Male and Female Offenders.” British Journal of Criminology 54 (3): 393–410. doi:10.1093/bjc/azu007.

- Batini, F., V. Corallino, G. Toti, and M. Bartolucci. 2017. “NEET: A Phenomenon yet to Be Explored.” Interchange 48 (1): 19–37. doi:10.1007/s10780-016-9290-x.

- Biemans, H., H. Mariën, E. Fleur, T. Beliaeva, and J. Harbers. 2019. “Promoting Students’ Transitions to Successive VET Levels through Continuing Learning Pathways.” Vocations and Learning 12 (2): 179–195. doi:10.1007/s12186-018-9203-5.

- Bronfenbrenner, U., and P. A. Morris. 2006. “The Bioecological Model of Human Development.” In Handbook of Child Psychology: Vol 1, Theoretical Models of Human Development, edited by R. M. Lerner and W. E. Damon, 793–828. West Sussex: John Wiley and Son.

- Bronfenbrenner, U.et al (1995). Developmental ecology through space and time: a future perspective. In P. Moen, G. H. Elder, and K. Luscher (Eds.), Examining lives in context: Perspectives on the ecology of human development (pp. 599–618). American Psychological Association.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. 1979. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Brown, C. 2014. Educational Binds of Poverty: The Lives of School Children. Oxon: Routledge.

- Brown, C, and J. Dixon. 2020. “Push on Through’: Children’s Perspectives on the Narratives of Resilience in Schools Identified for Intensive Mental Health Promotion.” British Educational Research Journal 1–20. doi:10.1002/berj.3583.

- Brunello, G., and M. De Paola. 2014. “The Cost of Early School Leaving in Europe. ” IZA Journal of Labor Policy (22). Accessed 10 March 2020 http://www.izajolp.com/content/3/1/22

- Cedefop. 2016. Leaving Education Early: Putting Vocational Education and Training Centre Stage. Volume I. Investigating Causes and Extent. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- D’Angelo, A., and N. Kaye, Ch.Timmerman. 2018. “Disengaged Students Insights from the RESL.eu International Survey.” In Comparative Perspectives on Early School Leaving in the European Union, edited by L. Van Praag, W. Nouwen, R. Van Caudenberg, and N. Clycq, 17–32. Milton: Taylor & Francis Group.

- Dickens, L., and P. Marx. 2020. “NEET as an Outcome for Care Leavers in South Africa: The Case of Girls and Boys Town.” Emerging Adulthood 8 (1): 64–72. doi:10.1177/2167696818805891.

- European Commission. 2015. Education & Training 2020. Schools Policy. A Whole School Approach to Tackling Early School Leaving. Brussels: European Union. Accessed 12 March 2020. http://ec.europa.eu/assets/eac/education/experts-groups/2014-2015/school/early-leaving-policy_en.pdf.

- European Commission. 2019a. Education and Training MONITOR 2019. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Accessed 12 March 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/education/resources-and-tools/document-library/education-and-training-monitor-eu-analysis-volume-1-2019_en.

- European Commission. 2019b. Assessment of the Implementation of the 2011 Council Recommendation on Policies to Reduce Early School Leaving. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Accessed 12 March 2020. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/72f0303e-cf8e-11e9-b4bf-01aa75ed71a1.

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. 2018. Second European Union Minorities and Discrimination Survey. Roma: selected findings.

- Eurostat. 2020. Early Leavers from Education and Training. European Commission. Accessed 12 March 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Early_leavers_from_education_and_training

- Gadsby, B. 2019. “Establishing the Employment Gap.“ Accessed 10 November 2021. https://impetus.org.uk/assets/publications/Report/Youth-Jobs-Gap-Establising-the-Employment-Gap-report.pdf

- Gairín, J., and C. I. Suárez. 2014. “Clarify and Identify Vulnerable Groups.” [Clarificar e identificar los grupos vulnerables]. In Vulnerable Groups at the University [Colectivos Vulnerables En La Universidad. Reflexión Y Propuestas Para La Intervención], edited by J. Gairín. 33–61. Spain: Wolters Kluwer.

- Gairín, J., and C.I. Suárez. 2012. “Vulnerability in Higher Education.” [La vulnerabilidad en educación superior]. In Academic Success of Vulnerable Groups in Risk Environments in Latin America [Éxito Académico de Colectivos Vulnerables En Entornos de Riesgo En Latinoamérica], edited by J. Gairín, D. Rodríguez-Gomez, and D. Castro. 39–62. Spain: Wolters Kluwer.

- Gerhartz-Reiter, S. 2017. “Success and Failure in Educational Careers: A Typology.” Studia paedagogica 22 (2): 135–152. doi:10.5817/SP2017-2-8.

- González-Rodríguez, D., M.J. Vieira, and J. Vidal. 2019. “Factors that Influence Early School Leaving: A Comprehensive Model.” Educational Research 61 (2): 214–230. doi:10.1080/00131881.2019.1596034.

- Grace, R., K. Hodge, and C. McMahon. 2017. “Child Development in Context.” In Children, Families and Communities, 3–25. South Melbourne, Victoria: Oxford University Press.

- Green, A. 2003. “Education, Globalisation and the Role of Comparative Research.” London Review of Education 1 (2): 84–97. July 2003. doi:10.1080/14748460306686.

- Holmes, C., E. Murphy, and K. Mayhew 2019. “What Accounts for Changes in the Chances of Being NEET in the UK?” SKOPE Working Paper No. 128, [The Centre on] Skills, Knowledge and Organisational Performance (SKOPE). http://www.skope.ox.ac.uk/?person=what-accounts-for-changes-in-the-chances-of-being-neet-in-the-uk

- Keep, E. 2020. “COVID-19 – Potential Consequences for Education, Training, and Skill“. SKOPE Issues Paper 36. Accessed 10 November 2021. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED607540.pdf

- Koehler, C., and J. Schneider. 2019. “Young Refugees in Education: The Particular Challenges of School Systems in Europe.” Comparative Migration Studies 7 (28). doi:10.1186/s40878-019-0129-3.

- Kolhberg, L. (1984) The Psychology of Moral Development: The Nature and Validity of Moral Stages, San Francisco: Harper and Row

- Lareau, A. (2000) ’Social Class and the daily lives of children: A study from the United States’, Childhood, 7(2)155-171

- Maguire, S, and E. McKay. 2017. Young, Female and Forgotten?: Final Report. Young Women’s Trust. https://www.youngwomenstrust.org/young-female-forgotten-2017. Accessed10 November 2021.

- O’Toole, L. 2016. A Bio-ecological Perspective on Educational Transition: Experiences of Children, Parents and Teachers.Doctoral Thesis, Technological University Dublin. doi:10.21427/D7GP4Z

- Olmos, P. 2011. “Orientation and Training to Vulnerable Young People’s Labour Integration.” [Orientación y formación para la integración laboral del colectivo jóvenes vulnerables]. PhD diss., Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

- Olmos, P., and O. Mas. 2013. “Youth, Academic Failure and Second Chance Training Programmes.” Revista Española de Orientación y Psicopedagogía (REOP) 24 (1): 78–93. doi:10.5944/reop.vol.24.num.1.2013.11272.

- Olmos, P., and O. Mas. 2017. “Perspective of Tutors and Companies on the Development of Key Competencies for Employability within the Framework of Basic VET Programmes.” [Perspectiva de tutores y de empresas sobre el desarrollo de las competencias básicas de empleabilidad en el marco de los programas de formación profesional básica.]. Educar 53 (2): 261–284. doi10.5565/rev/educar.870.

- Olmos, P., Ó. Mas, and F. Salvà. 2020. “Educational Disengagement Profiles: A Multidimensional Contribution within Basic Vocational Education and Training.” Revista de Educación 389: 69–94. doi:10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2020-389-455.

- Olmos, P. 2014. “Basic Skills and Perceptive Processes: Key Factors in Training and Guidance Processes of Young People at Risk of Educational, Social and Labour Exclusion.” [Competencias básicas y procesos perceptivos: factores claves en la formación y orientación de los jóvenes en riesgo de exclusión educativa y sociolaboral.]. Revista de Investigación Educativa 32 (2): 531–546. doi10.6018/rie.32.2.181551.

- Piaget J. (1932) The Moral Judgement of the Child, London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner and Co.

- Reimer Sacks, S. 2014. “Seeking the Right Fit: From Training Bras to Self-identity as Adolescents Search for Self.” In Adolescence in the 21st Century: Constants and Challenges, edited by F. R. Speilhagen, and P.D Schwartz. 3-21. Charlotte, NC: In formation Age Publishing.

- Rodwell, L., H. Romaniuk, W. Nilsen, J.B. Carlin, K.J. Lee, and G.C. Patton. 2018. “Adolescent Mental Health and Behavioural Predictors of Being NEET: A Prospective Study of Young Adults Not in Employment, Education, or Training.” Psychological Medicine 48 (5): 861–871. doi:10.1017/S0033291717002434.

- Royal Society of Arts.2013.“Between the Cracks: Exploring in-year transitions in schools in England.‘’ Available at https://www.thersa.org/reports/between-the-cracks Accessed 10th November 2021

- Salvà-Mut, F., C. Thomás-Vanrell, and Quintana-Murci. 2016. “School-to-work Transitions in Times of Crisis: The Case of Spanish Youth without Qualifications.” Journal of Youth Studies 19 (5): 593–611. doi:10.1080/13676261.2015.1098768.

- Salvà-Mut, F., M. Tugores-Ques, and E. Quintana-Murci. 2018. “NEETs in Spain: An Analysis in a Context of Economic Crisis.” International Journal of Lifelong Education 37 (2): 168–183. doi:10.1080/02601370.2017.1382016.

- Schoon, I. 2014. “Parental Worklessness and the Experience of NEET among Their Offspring. Evidence from the Longitudinal Study of Young People in England (LSYPE).” Longitudinal and Life Course Studies 5 (2): 129–150. doi:10.14301/llcs.v5i2.279.

- Sempik, J., and S. Becker, 2014. Young Adult Carers and Employment. Accessed10 November 2021. www.carers.orgwww.youngercarersmatter.orgwww.youngcarers.nethttp://professionals.carers.orgwww.carershub.org.

- Steinberg, L. H., L. Chung, and M. Little. 2004. “Re-entry of Young Offenders from the Justice System: A Developmental Perspective.” Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice 2 (1): 21–38. doi:10.1177/1541204003260045.

- Symonds, W.C., R.B. Schwartz, and R. Ferguson. 2011. Pathways to Prosperity: Meeting the Challenge of Preparing Young Americans for the 21stCentury. report issued by the Pathways to Prosperity Project. Boston, Mass: Harvard University, Harvard Graduate School of Education.

- Tomaszewska-Pękała, H., and A. Wrona. 2015. “Between School and Work. Vocational Education and the Policy against Early School Leaving in Poland.” Educação, Sociedade & Culturas 45: 75–95.

- Tomaszewska-Pękała, H., P. Marchlik, and A. Wrona. 2019. “Reversing the Trajectory of School Disengagement? Lessons from the Analysis of Warsaw Youth’s Educational Trajectories.” European Educational Research Journal. doi:10.1177/1474904119868866.

- Tudge, J., J. T. Gray, and D. M. Hogan. 1997. “Ecological Perspectives in Human Development: A Comparison of Gibson and Bronfenbrenner.” In Comparisons in Human Development: Understanding Time and Context, edited by J. Tudge, M. J. Shanahan, and J. Valsiner, 72–105. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Ungar, M. 2002. “A Deeper, More Social Ecological Social Work Practice.” Social Service Review 76 (3): 480–497. doi:10.1086/341185.

- Van Praag, L., W. Nouwen, R. Van Caudenberg, and N. Clycq, Timmerman, Ch. eds. 2018. Comparative Perspectives on Early School Leaving in the European Union. Milton: Taylor & Francis Group.

- Wang, M., and J. Amemiya. 2019. “Changing Beliefs to Be Engaged in School: Using Integrated Mindset Interventions to Promote Student Engagement during School Transitions.” In Handbook of Student Engagement Interventions. Working with Disengaged Students, edited by J.A. Fredricks, A.L. Reschly, and S.L. Christenson, 31–43. Academic Press. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-813413-9.00012-7.

- Whitty, G. 2002. Making Sense of Education Policy. London: Paul Chapman Publishing.