ABSTRACT

The prominence of Hindu-Buddhist mythology, imagery, and religiosity in Islamic Java has puzzled observers. The shadow play with its Mahābhārata- and Rāmāyaṇa-derived subject matter is a prime example. Another is the late 18th-century ‘renaissance’ of Old Javanese literature in the Islamic kingdom of Surakarta, which produced classics still celebrated today. Beyond a misguided assumption that the Javanese were so strongly disposed to syncretism that blatant doctrinal clashes did not bother their intellectuals, the factors that animated this enterprise remain obscure, despite its critical consequence for the development of Javanese religiosities. I scrutinize several unstudied manuscripts and piece together information from hitherto unconnected scholarship to try to understand these factors, with reference to pressing circumstances, living theories, as well as people who think, feel, and hope. First I examine Javanese theoretical ideas about the relationship between the Hindu-Buddhist and Islamic traditions and the connection between epic narratives and the present and future of Java. Against this background I consider the initiative, in 1778, to reinterpret the ancient epic heritage, beginning with the Arjunawiwāha (composed c. 1030). Focal points of interest in the Islamic hermeneutics of this poem were a quest for inner potency and the resulting external power of violence, knowledge and revelation, and future kingship.

Javanese religiosity is syncretic, so the theory goes. As the most influential 20th-century scholar of Javanese religions, Clifford Geertz, stated, the ‘religious tradition of Java, particularly of the peasantry, is a composite of Indian, Islamic, and indigenous Southeast Asian elements’ (Citation1973: 147). The historical overlaying of animistic traditions with first Hinduism and Buddhism from India, and later Islam, resulted in ‘a balanced syncretism of myth and ritual in which Hindu gods and goddesses, Moslem prophets and saints, and local spirits and demons all found a proper place’ (Citation1973: 147).

Van den Boogert (Citation2015) demonstrates that the idea of syncretism has characterised European descriptions of religion in Java since at least the 17th century. But some of the questions it raises have not been addressed. A fundamental question is historical and anthropological at the same time. Javanese in the past, too, were endowed with powers of analysis. How did Javanese theorists deal with a complex religious situation in which different and partly incompatible traditions met? Did they too conceive of it as a historical process of cultural accretion that yielded a religious mixture? Most importantly, what meanings did their own theories infuse into their religious practices and artefacts?

In this article I examine an intriguing cross-religious encounter that occurred in 1778 in Surakarta, Central Java. Within their Islamic culture and alongside their vast Islamic textual repertoire, Muslim princes and scholars faced a Hindu-Buddhist textual heritage. As princes and scholars, they cherished it; for them as Muslims, it was suspect. They found fascinating ways to come to terms with it. The encounter was productive, and consequential for the further religious history of Java.

A small number of poems in the Old Javanese or kawi language, composed in Java’s middle ages, circulated at the early modern Muslim courts of Kartasura (1680–1745) and its successors Surakarta (1745–) and Yogyakarta (1755–). These poems, known as layang kawi (kawi books) or kakawin, were held in high regard.Footnote1 This even led to what has been styled a ‘renaissance’ of Old Javanese literature, as several of them, possibly all that could still be found in Central Java, were reinterpreted in Modern Javanese language and verse, in what became, in hindsight, a veritable programme. This began with five epic kakawin at the court of Surakarta in the last decade of the reign of Paku Buwana III (1749–1788) and into that of his son Paku Buwana IV (1788–1820). The programme resonated in Yogyakarta as well and continued for almost 70 years. In the early 20th century several more kakawin adaptations were added to the repertoire.

In effect, only a single explanation has been put forward to account for this phenomenon. It is simplistic and, in view of the religious situation at the eighteenth-century courts, improbable. The Bible translator J.F.C. Gericke (Citation1844: vii–viii) wrote:

It may be regarded as a noteworthy sign of the revival of the old spirit among the Javanese, a spirit that had been extinguished by Mohammedanism, that in a later period people have begun to admire the works of the ancestors, to feel their loss, and to save as many as possible and preserve them for posterity. With this aim a number of learned Javanese among whom some (if insufficient) knowledge of kawi was still to be found, have endeavoured to render several still extant works from kawi into Javanese.Footnote2

Where Gericke, thinking along Enlightenment lines, ascribed this undertaking to an antiquarian desire to save and preserve an all but lost heritage, cultural politics in early modern Surakarta were oriented very differently. The Javanese palaces tend to be considered the epitomes of the Hindu-Buddhist strand in Javanese culture. But Nancy Florida (Citation1997: 195) has demonstrated that palace literature ‘extends well beyond the palace walls and is thoroughly Islamic in character’. This accords with the first-hand historical information, unearthed by Ann Kumar (Citation1980a, Citation1980b, 1997: 47–110) from a verse journal written by a woman soldier, about public religious life at the Surakarta princely courts in 1781–1791, and especially the religious practice of the rulers. Kumar (Citation1980b: 107) noted ‘a perhaps surprising amount of evidence of the dominant place of Islam as an organizing principle in at least one Javanese court; and on the other hand, no evidence of the currency of pre- or non-Islamic “Javanist” philosophies’. The Hindu-Buddhist ideologies of the Old Javanese texts must have raised eyebrows among the intelligentsia, not least among Islamic experts. Gericke passed over the issue in silence. Neither did later academics who adopted the idea of an Old Javanese literary revival or renaissance (including Pigeaud Citation1967 and Drewes Citation1974), or even those who questioned it (most prominently Ricklefs Citation1974: 219–226, 1978: 152–156, 212–220, and to a certain extent McDonald Citation1983, Citation1986) inquire into the religious politics at play.

Old Javanese (kawi) classics at the courts

In the religious worldmaking that took place in palace circles throughout the 18th century, Islam was hegemonic. This is evident from texts written in and sometimes describing this milieu, from literary works patronised by powerful nobles in the 1710s to 1730s (Ricklefs Citation1998b: 28–126) to the 1781–1791 journal of the female soldier. Sufism was a given. This form of Islam was ideologically oriented towards the Javanese royal dynasties, and the Muslim world outside Java, especially the Middle East. A remarkable figure in this religious environment has been portrayed particularly by Ricklefs: Ratu Mas Blitar, later named Ratu Paku Buwana (c.1657–1732), spouse of Susuhunan Paku Buwana I and progenitrix of princes and rulers. She patronised a body of literature in which, alongside dynastic history (Kouznetsova Citation2008), explicitly Islamic works took pride of place. These ranged from a monumental poetic rendition of the epic of Amir Hamza copied in 1715 to stories about prophets of Islam copied in 1729 (Ricklefs Citation1998b: 53–88). Ratu Paku Buwana may have been an adept of one or more Sufi orders (Fathurahman Citation2018: 59–61).

Meanwhile for princes in these courts – possibly not for women, as reference to female patronage of this genre is lacking – another kind of texts held key significance too. They were the kakawin or layang kawi, ‘kawi books’. Crafted in 9th- to 16th-century Java, these superb poems are awash with Hindu-Buddhist religiosity. Despite the public invisibility of pre- and non-Islamic philosophies in the late 1700s noted by Kumar, there is incontestable evidence of court patronage of these works. Throughout the 18th century, beautifully illuminated manuscripts of several kakawin using costly European rag paper were produced from time to time for princes (Arps and van der Molen Citation1994: xxix–xxx). According to Raffles – quoting an obscure Javanese text presumably from the 18th century – they were considered part of noblemen’s civilised upbringing:

It is incumbent upon every man of condition to be well versed in the history of former times, and to have read all the chiríta (written compositions) of the country: first, the different Ráma, the B’rata yúdha, Arjúna wijáya, Bíma súchi …

(Raffles Citation1817, I: 255)

The earliest known kakawin manuscript from Central Javanese aristocratic circles is a copy of the 14th- or 15th-century Shivaite expository poem Dharmaśūnya. This manuscript was written personally by Prince Dipanagara, a son of Paku Buwana I, in November 1716Footnote3 – one year after his father’s queen commissioned her Amir Hamza manuscript. There are copies of the Dharmaśūnya in the collection of palm leaf manuscripts in archaic script that in the 18th century formed the library of a hermit named Windusana in a remote settlement on Mt Mĕrbabu (Wiryamartana and van der Molen Citation2001). But from the courts, no other manuscripts seem to have survived. It is unknown where Dipanagara obtained the Dharmaśūnya or what were his motivations for copying it, but he was remembered later as a collector of kawi texts.Footnote4 Dipanagara rebelled against his father in 1718 (in a manner that may relate to his involvement in kawi letters, as discussed briefly below). He was captured by the United East India Company (VOC) and banished to the Cape of Good Hope in 1723 (Brandes Citation1889: 370–372).

Another kakawin that has survived in a beautiful Kartasura-period paper manuscript is the epic narrative of Arjunawijaya (‘Arjuna’s Victory’) or Lokapala (‘The World-Protector’, a protagonist’s epithet). Originally composed in the late 14th century by Mpu Tantular, its prologue invokes the Divine King of the Mountains (most likely Shiva-Buddha, possibly Shiva) who is ‘the very image of Buddha, the supreme reality’, and its epilogue ‘lord Wiṣṇu, who is regarded as Buddha in His visible form’ (Supomo Citation1977, II: 181, 281; cf. Zoetmulder Citation1974: 342–345). This particular manuscript was inscribed between 1681 and c.1725 (Arps and van der Molen Citation1994: xxiii). The similarity of script and illumination to Dipanagara’s Dharmaśūnya suggests that this Arjunawijaya manuscript, too, hails from Kartasura princely circles, possibly from Dipanagara. It seems to have remained in the family (until it was acquired by a colonial scholar). A later copy of the Lokapala was completed for the heir apparent of Surakarta in early to mid June 1783, using as the exemplar, a descendant of this specific manuscript (Arps and van der Molen Citation1994: xxx–xxxiii, xxxv).

On 18 May 1783, when he was aged 15, this prince, who was later to be Paku Buwana IV, was married to a princess from Madura. Florida (Citation2012: 205–208) proposes that at least two other kakawin manuscripts, both splendidly illuminated, were created on the occasion of the wedding. One is the Rama, that is the Old Javanese Rāmāyaṇa datable to the 9th century. It has a Shivaite background while its hero Rāma is an incarnation of Vishnu (Acri Citation2016: 457–458; cf. Zoetmulder Citation1974: 233). The crown prince’s copy was completed on 11 April 1783. On an unspecified date, a copy was also made for him of the Bratayuda (Bhāratayuddha), a Shivaite-Vishnuite kakawin dated 1157, authored by poets Sĕḍah and Panuluh (Zoetmulder Citation1974: 272–273), which describes the final battle of the other great Indian epic, the Mahābhārata. The Lokapala, completed shortly afterwards, must have been part of the same set. Another Rama manuscript had been inscribed in 1753 for the then crown prince of Surakarta (Arps and van der Molen Citation1994: xxx),Footnote5 and Florida (Citation2012: 205) points to yet another copy of the Rama made for a crown prince – the later Paku Buwana V – in 1798. It appears that under Paku Buwana III and IV, the heir apparent should possess Old Javanese kakawin, but where their relevance lay is an open question.

As Dipanagara’s Dharmaśūnya shows, other princes too owned kakawin texts. Purbaya, a brother of Dipanagara (and likewise exiled, in his case to Sri Lanka in 1738), was not a crown prince either. A collection of texts written for him in 1736 and 1737 (Ricklefs Citation1998b: 200–204) contained the Old Javanese Nītiśāstra. Possibly assembled in the 15th century, this versified collection of aphorisms on political ethics is dedicated to Vishnu (Poerbatjaraka Citation1933: 21). Purbaya’s version contains stanza-by-stanza paraphrases in Modern Javanese.

For certain other kakawin manuscripts from this period the patronage is indistinct or unknown, and more than once the texts are incomplete. One especially revealing manuscript was copied or compiled by, or for a member of the Yogyakarta court in the late 1760s.Footnote6 Notes in the margin identify its one-time owner as Mas Cakrawijaya; in one note he is said to have received the text in question from his father.Footnote7 As Cakrawijaya and his father’s titles indicate, he was a member of the lower nobility, probably a grandson or great-grandson of a king. It is tempting to identify him with the person whom Prince Mangkubumi, about to become Sultan Hamĕngku Buwana I of Yogyakarta, made his head scribe (lurah carik) as part of a wave of official appointments upon the creation of the sultanate in 1755. This man was renamed Cakrawijaya with the middle-level rank of ngabehi (Yasadipura Citation1938c: 69). Cakrawijaya’s earlier name had been distinctly Islamic: MuhyidinFootnote8 (Muḥyi’d-Dīn ‘Reviver of the Faith’), an appellation of two celebrated medieval Sufi scholars, ‘Abdul Qādir al-Jīlānī and Ibn ‘Arabī, that had also been borne, among many others across the Islamic world, by a scholar in western Java who transmitted Shaṭṭāriyya teachings in the early 18th century (Florida Citation2019: 157). Before his promotion, Muhyidin had been a commander (lurah) of Mangkubumi’s suranata corps of armed Islamic officials. In this capacity, he had served his prince as letter-writer and courier (Yasadipura Citation1938a: 75, Citation1938b: 17). Alongside their military tasks the suranata were ‘responsible for the preparation of offerings and the reciting of incantations (both Javanese and Arabic-Islamic) for the metaphysical well-being of the king, royal family, and realm’ (Florida Citation1995: 168).

If the manuscript’s owner and the Sultan’s head scribe were the same person, the situation was absolutely fascinating. To be sure, Mas Cakrawijaya’s volume contains – or rather, used to containFootnote9 – at least two Muslim poems, the Sewaka and a dialogue of Muhammad and the Devil. But, surprisingly, it also contains a miscellany of non-Islamic lore (archaic texts on the Javanese writing system, synonyms, ornithomancy, and more) and material from several kakawin, including a large part of the Bratayuda. At the beginning of a few cantos, the verse form name is given, showing that it was written to be recited, i.e. sung. The manuscript also used to contain the Bima Suci, a poem possibly from the 15th century, recounting the quest of Bhīma, the Mahābhārata’s hero, for the purifying water at the command of his guru Drona. And it contains the first two verse lines of Bratayuda with interlinear glosses in Modern Javanese, and a canto and a half of the Wiwaha (the early 11th-century Arjunawiwāha), also with glosses.

The manuscript that once belonged to Mas Cakrawijaya is mostly written in Javanese characters (in several hands). But its Bratayuda and Wiwaha contain stretches in archaic letters. In the manuscript itself this script is called ‘mountain writing’ (sastra prawata, f. 17r). Scribbles on the flyleaf and loose characters in the margins suggest that the writer was practising it as he was copying the text. A rather untrained variety of these letters was also used in part of Mas Cakrawijaya’s name in several ex-libris inscriptions, presumably playfully as a kind of cryptography. The fact that people at the court of Yogyakarta used this script, intimately associated with palm leaf manuscripts, mountain hermitages, and the remnants of Hindu-Buddhism, suggests that there was a tradition of teaching it in the sultanate, or that some people were in contact with mountain-based scholars, perhaps studying with them.

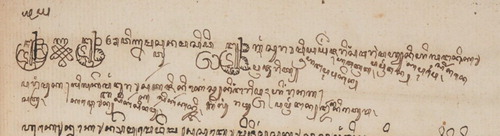

The Old Javanese Nītiśāstra with paraphrases in Purbaya’s manuscript and elsewhere, Mas Cakrawijaya’s Bratayuda fragment with glosses, and his partial Wiwaha with paraphrases demonstrate that in the 18th-century courts, alongside interests in singing and writing kakawin and enhancing their beauty by using precious materials and adding splendid illumination, there was also an interest in apprehending and understanding their archaic kawi language and their contents which were ‘buddhic’ (buda, that is to say non-Islamic, extra-Islamic, or pre-Islamic).Footnote10 The Bratayuda glosses are interlinear, written in slightly smaller characters than the main text, and most slant downwards beginning under the kawi word they explain (see ). This textual layout is not unique. It mirrors a typically Islamic form employed in Arabic treatises with interlinear glosses. These texts are known, after the graphic impression their lines make, as ‘bearded books’ (kitab jenggotan; van Bruinessen Citation1990: 235). The form is in evidence in Java since at least 1624 (Gallop with Arps 1991: 100). There are three main formal contrasts between such Islamic treatises and this Bratayuda fragment: (1) the written text and glosses of a kitab run from right to left, those of this Bratayuda in the opposite direction; (2) the language of a kitab is Arabic, that of the Bratayuda was kawi; and (3) a kitab begins with the basmala ‘In the name of God, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful’, while this Bratayuda begins with a buddhic invocation ‘May there be no hindrance, homage to the Perfect’.Footnote11 Yet these contrasts occur within formal sameness, created by the jenggotan model. This is Islamic. Moreover in either case the glosses are in Modern Javanese, the medium of Muslim everyday life in the 18th-century lowlands. The jenggotan format of laying out text on paper connotes a method of teaching and learning textual interpretation as well. This too is Islamic. Students in religious schools would come to a teacher with a manuscript containing an Arabic text with ample interlinear spacing. The teacher would orally provide glosses in Javanese, which the students would scribble obliquely between the lines (Gallop with Arps 1991: 101). Given the hand and ink, which are the same for main text and glosses, it is unlikely that the Bratayuda fragment was really produced in this way. But this way of processing the discourse was signified by the textual form.

Figure 1. Two verse lines from the Old Javanese Bhāratayuddha with interlinear glosses in Modern Javanese (British Library MSS Jav 8, f. 88r top. Courtesy of the British Library Board)

In the late 1770s, under Paku Buwana III at the Surakarta court, from the tradition of copying, reciting, and interpreting kakawin on paper and probably orally too, a programme of rewriting in Modern Javanese language emerged, employing Modern Javanese verse forms (tĕmbang macapat). As Day (Citation1981: 53) has argued, ‘only this form provided the right conditions for the exercise of Modern Javanese kinds of vocal ornamentation and for the creation of Modern Javanese poetic charm’.Footnote12 The Wiwaha was adapted in this fashion in 1778, the Lokapala or Arjuna Wijaya, partially at least, later in the same year, the Rama (probably partly) in 1785, the Bratayuda at an unknown date but reputedly under Paku Buwana III (1788 at the latest), while an adaptation of the Bima Suci was begun under Paku Buwana III and completed under Paku Buwana IV, probably in 1788 or 1789 (and certainly before 1793). Data on authorship stem from later tradition; these works are all attributed to legendary court poet-scholar Yasadipura I (1729–1803).Footnote13 Thus far their patronage, too, is known largely from later oral tradition.

But why, in this milieu and at this point in time, were Old Javanese works not only copied, recited, and studied, as they had been for several generations (at least), but recomposed in Modern Javanese? The patrons, writers, owners, readers, and audiences of these pervasively buddhic texts were Muslims; some seem to have been Islamic professionals, a few were even poised to rule Islamic realms, bearing titles like ‘Servant of The Compassionate’ (Abdurahman) and ‘Arranger of the Religion’ (Panatagama).Footnote14 How could these people’s involvement in heathen texts and thought-worlds be consistent with their faith and the hegemony of Islam?

Theoretical ideas (1): left and right religious cultures

Theoretical ideas were afoot in 18th-century central Java that justified the study of Hindu-Buddhist texts alongside Islamic ones. What is more, they showed such study to be wise. These ideas concerned religious orientations and the structural relations between them, historical eras, and envisioned futures. Here I review the ideas, glimpsed from miscellaneous references.Footnote15

The first and fundamental idea was that two traditions should be distinguished within Javanese culture. Early modern practices and ideologies of categorisation in the realm of religious culture, including its nomenclature, will have varied locally. In the Islamised lowlands, particularly at the courts, a distinction was made between ‘the left-sided’ (pangiwa) versus ‘the right-sided’ (panĕngĕn). In most respects panĕngĕn corresponded to ‘Islamic’ or ‘Muslim’, and pangiwa to ‘buddhic’. The left-right binary was manifest in select cultural domains. In pre-1775 textual sources I have found it applied to writing systems, expert knowledge and teachings, and genealogies of rulers.Footnote16 It may well have featured in other realms too, including that of ritual practice, in respect of two super-categories of ancestral or divine figures to whom (Islamic) ritual meals could be dedicated.Footnote17

Although the distinction seems to be purely structural, a particular temporality and location is implied by it. Alternative designations drawing partly the same contrast included mukmin (‘believer’) or Islam ‘Islam(ic)’ versus kafir (‘infidel’),Footnote18 and as mentioned, Islam versus buda. Kafir was timeless but condemnatory, and the condition could in principle be remedied (by conversion, reform, or death). Buda was more neutral but typically distant: in the past or the mountains. Pangiwa, while rooted in the past or mountains, is here and now, like its opposite panĕngĕn.

Pangiwa is a relational term. As it must have a counterpart, it connotes a system. Its expression is therefore part of a theory. While in many contexts it may have remained implicit or minimalist, this theory was expounded orally in esoteric teaching situations.Footnote19

The classification is decidedly binary. It concerns Javanese religious traditions and does not take account of Christianity, even if the VOC’s Calvinism was a mighty force in Javanese history.Footnote20 Also, despite the variety of Hindu-Buddhist orientations recognised a century or two earlier (witness, for instance, the texts edited by Pigeaud Citation1924 and Swellengrebel Citation1936), pangiwa appears as an undifferentiated whole. The panĕngĕn category is likewise unitary.

The opposition may have had Hindu-Buddhist antecedents. A binary contrast referred to elsewhere as left-right is thematised in the Javanese Korawāśrama. This is a pre-16th-century collection of religious teachings framed in a prose narrative of how the Korawa party, revived after the Bhāratayuddha, consult deities and perform asceticism (tapa) to gain power to destroy the Pāṇḍawa brothers, who have also been revived (Swellengrebel Citation1936). The Korawāśrama does not refer to the opposing parties as left and right, but these designations do play an important role in today’s tradition of Balinese shadow theatre, which recounts Mahābhārata-derived stories. The members of the dramatis personae belong to either the right- or the left-hand party across the genre’s entire repertoire or variably, depending on the play. Consequently, they are supposed to enter from and stand on either side of the screen (Hinzler Citation1981: 53, 59). As the contrast between right-hand and left-hand shadow-play characters (wayang tĕngĕn and wayang kiwa) was also a theme of the prominent 17th or early to mid 18th century Javanese Suluk Wujil (‘Mystical song of the dwarf’), referring to the Pandhawa and Korawa, respectively (Poerbatjaraka Citation1938: 159), it is likely to be of considerable age in Java.

Binaries feature in Islamic thought too. A contrast between people of the right- and left-hand side is drawn in several places in the Qur’an.Footnote21 In the Suluk Wujil, the shadow play’s left-right opposition is interpreted metaphorically as the equivalent of the Islamic contrast between negation and affirmation (Ar:. nafy wa-ithbāt, Jav:. napi isbat), a theme of philosophical discussion with respect to the profession of faith (Drewes Citation1968: 215–217; cf. Chittick Citation1989:113 et passim). This theme is prominent already in one of the earliest surviving Javanese treatises on Islam (Drewes Citation1969). In India, it plays a role in Sufi meditational practice (Buehler Citation1998: 125–130, Citation2000: 353, 355), as presumably it did in Java. But irrespective of their provenance, the opposition of left-sided and right-sided traditions, and the left-right contrast that lies at its basis, were invoked in a self-conscious Muslim context.

The second central notion in the theory of Javanese religious cultures circulating in the 18th century was that of counterbalance (timbangan). Buddhicism was not just a companion to hegemonic Islam, but its necessary counterpoise. This idea occurs in the central Javanese dynastic histories since at least 1750, when the mythical left-sided genealogy they begin with mentions the first-ever kings of Java. As formulated in a manuscript of 1764, possibly from Yogyakarta:

God Tunggal’s son was Guru / And Guru’s children were five in number / [ … ] / Wisnu was the last-born of them / He was to reign as king / Ruling in the land of Java / For he was made to counterweigh the religion / Of Islam in Arabia.Footnote22

If the counterweighing categories exist to create equilibrium, at a certain level of abstraction they must be the same. The dwarf Wujil, a central personage of the Suluk Wujil, reminds his learned guru:

As you explained when revealing the unity of scripts / The pangiwa and the panĕngĕn / Exhibit no disparity / For they are fashioned in the form of song / And they are uttered aloud / Such are both of them.Footnote23

The equivalence of left- and right-hand sides was asserted, argued, and demonstrated, but it will not have come naturally. Left and right were not neutral, wholly formal opposites. They were qualitatively unequal, for the terms were evaluative. Left connoted bad, wicked, sinister, inherently condemnable. Right was good, virtuous, praiseworthy. The contrasting of pangiwa and panĕngĕn thus implicated the higher level argument just demonstrated. In the relevant writings, the assertion is indeed almost always stated explicitly: pangiwa and panĕngĕn are in balance despite the fact that, as the very terms ineluctably signify, they are not.

Theoretical ideas (2): the yuga epochs in left-sided history

Considering Javanese Islam as essentially syncretic bypasses Javanese theory and the living social understandings of religious culture it abstracted and simultaneously engendered. But certain powerful modes of thought assigned to the pangiwa cultural tradition did colour the lived experience of Islam. One of these is key to the perception of the Old Javanese epic classics. It is the schema of four epochs (yuga) that characterises historical awareness throughout Hindu and Buddhist South and Southeast Asia. This schema comprised a recurrent cycle of four aeons (caturyuga): Kṛtayuga, Tretāyuga, Dvāparayuga, and Kaliyuga. Depending on the theory, a yuga lasted thousands or even millions of years, but they tended to be successively shorter and, importantly, more degraded morally. The current age is typically a Kaliyuga and degenerate.Footnote25 The Sanskrit epics and their Javanese retellings were linked to this schema; they were taken to recount events in the most recent round, particularly in transition periods between yugas (Drewes Citation1925: 158–159). This left-sided way of conceiving history circulated in 18th-century Java. Islamic temporality was incorporated into it, and modified it as well.

In Purbaya’s collective manuscript from 1736–1737, a stanza of the kakawin Nītiśāstra is paraphrased as follows in Modern Javanese:

The Old Javanese stanza itself merely lists the women who caused strife in each of three yuga and concludes cynically (though in tune with the Nītiśāstra’s overall cultural pessimism) that ‘all women at epoch’s end desire(d) to be the cause of terrifying war’.Footnote27 The stanza thus proposes a peculiar way of conceiving these epic wars. Except perhaps in the case of the Rāmāyaṇa, seeing them as primarily struggles for a woman is eisegesis. This is culturally meaningful; I will return to it. The paraphrase expands on the viewpoint of the original stanza, specifies durations for the yuga and in the case of the Sangara age, for its concluding war, and prophesies that the Sangara’s war will be about an ascetic’s daughter. However, not reflected in the paraphrase is the exemplar’s observation that the war in the Dopara age was the Bhāratayuddha, the suggestion that each war marked an epoch’s end (yuganta), and the cynicism of the conclusion. The partial lack of correspondence suggests that the paraphrase quoted perceptions circulating more widely.Footnote28 That the second war was the conflict in the Rāmāyaṇa between Rāma and the monkey army versus Rāwaṇa and his demons, and the third, the Bhāratayuddha, will have been obvious to those familiar with shadow play or left-sided epic literature, although the identity of Naruki and her war may have been unclear, as she only features in a little known episode.Footnote29 The fourth war was also mysterious, of course, as it was still to occur – giving certain power-holders reason for concern, and others grounds for hope.

The idea of a yuga historical schema was not restricted to Old Javanese texts and their study. It was acknowledged in public, at least at the courts – witness its presence in the opening recitative of a dance drama from the Yogyakarta sultanate that appears to pre-date 1781.Footnote30 The performance genre is identified as ringgit prawaraga ‘embodied ringgit of (classical) antiquity’, in which ringgit is a synonym of wayang, i.e. shadow play or epic performance more broadly; prawa is a variant of purwa ‘antiquity’ that also retains a vestige of its Old Javanese etymon parwa ‘book (of the Mahābhārata in particular)’; and raga is a poetic word meaning ‘human body’. With the invocation ‘May there be no hindrance, homage to the Perfect’, the play script presents itself, like the genre overall, as buddhic.Footnote31 After sketching the remarkable image of ‘a leaf-bud of the universe’ (pupusing alam) that has broken off, is inscribed with writing (sastra), and looms up in the east and the west,Footnote32 the recitative explains that ‘the narratives of wayang prawa’ (kandhane wayang prawa) encompass five counterbalances (the familiar titimbangan) and four ‘plays’ (lampahan). Here the counterbalances are social and ethical rather than denominational: ‘servant and lord, big and small, old and young, male and female, evil and good’.Footnote33 The first three plays named are the Gujinggaprawa (set in the Kĕrtayuga, under King Sahasrabau, about a war in which demons fought other demons, contending over a woman named Citrawati), the Utarakandha (in the Tirta age, under King Ramadewa, in which demons fought monkeys over Sinta), and the Utarayana (set in the Dupara age, in which Krĕsna battles with his son Boma over Tisnawati). As in the Nītiśāstra, the yuga system is linked to epic narratives viewed as stories about wars arising from rivalry over a woman. Except perhaps in the case of Rama and Sinta (Rāma and Sītā), again such an interpretation is strained. It appears to have had the cultural status of a dogma. The first and third narratives have unknown titles, and the second does not exactly match the title given, but the stories themselves are familiar from epic kakawin: the Arjunawijaya, Rāmāyaṇa, and Bhomāntaka. Differences in the names of protagonists, discrepancies between a story’s reported and actual contents, and possibly also the mysterious titles may result from oral transmission in the context of storytelling or shadow play.

After identifying Tisnawati as the Utarayana’s object of contention, the text continues:

Arjuna’s embarrassment which leads him to practise ascetic discipline (atapa) is not recounted in the Bhomāntaka; it too may derive from oral or wayang versions of the story. Of course, Wiwaha is the Modern Javanese title of the Old Javanese Arjunawiwāha. Apart from the fact that Supraba was not really contended for by Arjuna and Niwata Kawaca (although both wanted her, and Arjuna gained her in the end), its summary accords with the kakawin. The kakawin also recounts the preceding tapa by Arjuna.Beginning a wayang performance by stating a connection between the genre’s repertoire and literary texts was an established tradition with a centuries-long pedigree. The exordium of Balinese shadow play likewise refers to parwa (Zurbuchen Citation1987: x, 268). But the details are different, and no yuga are mentioned. That the details varied is unsurprising in the living, context-sensitive, and adaptable traditions of shadow play and danced drama. The information given in each tradition presumably resonated with issues considered relevant in the socio-political environment of the time. In the wayang exordium from the 18th-century Yogyakarta sultan’s court, the critical categories included the five social and ethical counterbalances and certain historical-narrative concerns. These were the yuga epoch, the ruling king,Footnote34 the nature of the opponents in the war that concluded the epoch and heralded in the next, as well as the relationship between these opponents, and the identity of the female object of strife. Seeing that it was read stubbornly into each of the narratives said to form the wayang’s repertoire, the ‘women as objects of destructive rivalry at epoch’s end’ pattern must have been a cultural theme. An authoritative textual source for this perspective on inter-group warfare was the Nītiśāstra, which continued to be copied and studied at the 18th-century courts. The exordium mentions only instances of this pattern in the mythic past, but the Nītiśāstra paraphrase predicts one for the future as well.

A critical element of the epochal system was the Kali age of degeneration. In the paraphrase of earlier stanzas in the Nītiśāstra, the Kaliyuga is predicted to end with male authority figures – kings, pandits, pandit-kings, and fathers – losing their power. ‘Base people will reign as kings.’Footnote35 The perks of kingship will move out of reach of the current ruler: ‘Later in the Kaliyuga this world will shake and sway, the king will lose his wealth and kingdom.’Footnote36 This prediction will have been dreaded in the royal families of Java. It was in their interest to be prepared for the prophesied social upheaval and conflict. Some were well advised to prevent it if possible, others might want to take advantage. Most of the wayang exordium’s internecine wars are assigned to books that by the 1770s were lost or imagined. But then there were the kakawin. The classics of Old Javanese epic literature (as well as core plays in the shadow theatre) actually recounted these wars. Hence understanding these kakawin might be not only pleasurable but useful. They could help to appreciate historical events of cosmic import, which in in turn would yield vital information about events of similar magnitude that were still to happen.

Theoretical ideas (3): the yuga epochs in Islam

The yuga epochal system, learned though it was, circulated and was professed in public performance, at least within the palace. Yet it was pangiwa. How could these left-sided ideas about the longue durée be reconciled with the fundamentally different historical sensibility of Islam, the entrenched religion in lowland Central Java when the Nītiśāstra and its paraphrase were copied for Prince Purbaya, and when the wayang text was written?

A small but significant token that conceptual rapprochement had taken place is the use of the Arabic-derived term jaman ‘age, period, times’ (Ar. zaman) in addition to yuga to refer to these universal epochs, in the Nītiśāstra paraphrase, the wayang exordium, and elsewhere. Bigger answers from 18th-century Java are difficult to obtain, though an admittedly still indefinite picture can be pieced together from miscellaneous sources. In the South and Southeast Asian region there had been other milieus where Islam met Hindu-Buddhist cultures. Writing in 1631/1632 at the court of Mughal emperor Shāh Jahān, Sufi scholar ‘Abd al-Raḥmān Chishtī incorporated the yuga system into Islamic historical thinking, adopting it as his encompassing framework (Alam Citation2015). That something analogous happened in Java (where Chishtiyya Sufism seems to have enjoyed little or no adherence) is suggested by an Islamic compendium of notes in a 19th-century manuscript studied by Drewes (Citation1925). One of its texts, a historico-prophetic survey of the duration, life expectancy, food, weapons, etc. of all four yuga, is undated but its central ideas are known to have circulated in the 18th century.Footnote37 After the Kaliyuga, it says, there will be an age of Destruction (Sangara), in which people will be like cattle unaware of their pen, children do not care about parents and vice versa, and likewise with gurus and pupils (Drewes Citation1925: 164–165; cf. Add MS 12316, f. 37v). In what seems to be an appended remark, the birth and death of the Prophet (Muḥammad) are located in the Kaliyuga. So while in the wayang exordium the jaman Sĕngara was in the mythic past, here it lies in the future, as in the Nītiśāstra paraphrase.

Another undated text in the same compendium presents a detailed historico-prophetic scenario to which Islam is integral. The Universal Period of Treta (or ‘of the Water’; Alam Tirta) was before the Creation and the formation of order (Drewes Citation1925: 166). After Creation there was an era (of 7,777,777 years) during which Adam lived. The prophets Idris and Noh (Noah) are placed in the Universal Period of Kĕrta (or ‘of Prosperity’; Alam Kĕrta), Abraham and Moses in the Universal Period of Dopara (Alam Dopara), and in the Kaliyuga lived Jesus and Muḥammad, several royal lines of Java, and the legendary bringers of Islam (wali sanga or ‘nine saints’). This will be followed by the Universal Period of Destruction (Alam Sangara), in which Java will be ruled by a king who is a merchant-sailor (ratu nakoda), when royal justice will vanish, there will be no more pandits, the earth will turn infertile, and women will lose all shame (Drewes Citation1925: 165–166). In the narrative economy of late 18th-century Java, the ratu nakoda figure is associated first and foremost with Europeans; witness especially the Book of Sakendher (Ricklefs Citation1974: 377–413, Kouznetsova Citation2007). In the present text, ratu nakoda thus probably alluded to the VOC. Alongside Islam, the text brings colonial history into the picture as well.

A prophesy that a new king will thereupon emerge from the Ka‘ba in Hijri 1200 suggests that this text was formulated in 1785 CE at the latest. After years of practising asceticism on various mountains, this king will attempt to put an end to the fighting. But general chaos and symbolic inversion will reign, with servants pretending to be kings, and thieves and robbers being successful. Still later the Mahdi – the eschatological redeemer of Islam – will appear in Mecca. In Java, once the infidels have been subjected, a golden age will begin. The end of times will be 607 years later (Drewes Citation1925: 166–167). The idea that the Kaliyuga will be followed by Destruction is in itself not Islamic as it occurs in Old Javanese texts (Drewes Citation1925: 157–158), so what we see here is Islamic eschatology given a narrative structure – particular types of protagonists, events and circumstances, settings, and sequence – that employs macro-categories from the yuga epochal system and posits early-modern colonial Java as the vantage point.

The sources for the above picture of notions in Javanese historico-prophetic theory are not indubitably pre-1778. Historically we are on firmer ground with the curious short text Story from the Book of Mysteries (Carita saking Kitab Asrar), edited by Brandes (Citation1889) on the basis of a manuscript in archaic ‘mountain’ characters from Windusana’s library (Setyawati et al. Citation2002: 157).Footnote38 It lists successive royal dynasties from the first king of Java into the future. Brandes (Citation1889: 347) dated the text between 1645 and 1715. The Story from the Book of Mysteries (henceforth: Story) bears a broad resemblance to the two historico-prophetic texts just mentioned. But while the approach of the first is anthropological, and the second concerns the histories of prophets and kings in both the Middle East and Java, the Story presents an eastern Java-centric view (Brandes Citation1889: 379–380). It encompasses Java, Bali, Sumatra, and the Malay Peninsula (Brandes Citation1889: 386), but does not allude to the colonial presence. Although it does not mention prophets or Arabia either, the text’s outlook is Islamic. It notes that at a certain time ‘Java was still a land of infidels.’Footnote39 It employs the Islamic months, Javano-Islamic years, and a Hijri year. Its textual context is Islamic as well; other texts in two of the manuscripts containing the Story include a History of the Prophets from the Creation, and information on the ritual prayer (Brandes Citation1889: 373, Setyawati et al. Citation2002: 115, 157).

Unlike the other texts discussed, the Story is not structured into four ages plus Destruction. Though without using the name, it does describe a situation of upheaval and miscommunication typical of the Kaliyuga (Brandes Citation1889: 383–384, 386). It also states that after the 100-year reign of a new king, a descendant of a Friend of God (Waliullah) who will appear in Java in the year 1200, ‘the times will revert to a condition like the Trita’.Footnote40 This shows that the notion of a Treta age – the age that preceded the Creation in several of the texts studied by Drewes (Citation1925: 165) – was self-evident. The silent assumption of the yuga’s relevance implies that they were commonplace in historico-prophetic thinking in Muslim Java around 1700.Footnote41

In addition, these historico-prophetic texts reveal that the yuga schema was not only embraced to account for a Muslim past, present, and future, but also naturalised to the Muslim sense of the longue durée. The difference may be difficult to discern on the surface, but it is radical. Unlike in Hindu India and probably ancient Java, in early modern Java the yuga did not form recurring cycles but were singular periods, segments of a historical time that runs in linear fashion from the Creation to the end of times.Footnote42 In fact the same had been argued in 1631/1632 Agra by ‘Abd al-Raḥmān Chishtī (Alam Citation2015: 122–123).

Buddhic and Islamic ideas about history were felt to be compatible in another important way as well. The dogmatic proposition about the cause of all yuga-ending wars in the Nītiśāstra and its paraphrase resonated with a right-sided idea about the very origins of violent human conflict that went round in Java. As recorded in the Qur’an, the first death in human history was the killing of Abel by Cain. According to the Javanese mythological Book of Stories (Sĕrat Kandha) this primal murder was triggered by their rivalry over a woman.Footnote43 Indeed Malay and Javanese versions of the Stories of the Prophets (Qiṣaṣ al-Anbiyā’) related that Kabil (Cain) desired the wife of Abil (Abel), who was more beautiful than the wife he had been allotted by their father Adam (Gerth van Wijk Citation1893: 264–265).

The yuga and the historico-prophetic scenarios they framed were more than a schema for making sense of the past and managing apprehension about the future; they were a model. As Brandes has shown, when in 1718 Prince Dipanagara had taken up arms against his father Paku Buwana I, a fellow rebel leader crowned him ruler under the name of Erucakra. Now according to the Story, the king with the status of Friend of God (ratu jnĕng Waliullah), who would appear at the end of a (Kaliyuga-like) period of upheaval and confusion in Java, to replace the kings of Sundha Rowang (that is to say Mataram, the house of which Paku Buwana I was the incumbent), would be called Erucakra. Also in other respects Dipanagara fulfilled the prophesy of this text. It may not be a coincidence that he was deeply familiar with at least one kakawin manuscript (having copied it himself in 1716) and possibly more. As noted, Dipanagara did fail (Brandes Citation1889: 370–372, 380, 384, 386).

That vying for a woman could have dramatic and far-reaching consequences was also observed by Javanese historical commentators. Not only had this pattern occurred at the outset of right-sided history (after all it was the reason for Abel’s murder by Cain), in the decades-long chain of events that preceded Dipanagara’s uprising there had been several sensational love affairs and scandalous breaches of propriety in princely circles. They had led to cruel executions, mortal combat, and above all, further conflict.Footnote44 No doubt these cases were distressing to the powers that be.

The assorted ideas I have spotted signal the existence in the 18th century of a Javanese intellectual framework recognising four or five eras of universal moral and religious history-and-future, connected where the distant past was concerned to the canonical epic narratives, and partly corroborated by notorious events in the more recent past. The driving force of this temporal sensibility was Islam(ic), but it was consciously counterweighed by a buddhic antithesis. These theoretical notions taken together provided good reason to study the left-sided classics. If current kingship was bound to be challenged in the Kaliyuga or the imminent Age of Destruction, the epic kakawin could reveal what had catalysed the transformation in earlier eras, who the contestants had been, how it had unfolded, and how rulers, rebels, and others had dealt with the situation. Certain schematic and rather dogmatic ideas circulated about these matters in wayang and oral tradition. Differences between these ideas and the actual contents of the Old Javanese texts were easy to discover once one actually sat down to interpret those texts. Finding such discrepancies may have piqued readers’ curiosity even more.

The king’s Wiwaha paraphrase: recognition and the beginning of a programme

What occured at the Surakarta court in 1778 was not mere perusal of the kawi classics. It went deeper, and yielded interpretations that would last and spread. Judging by the available information, the initiative to reinterpret the epic kakawin in contemporary poetic form was taken by the ruler of Surakarta, Paku Buwana III. Between 21 June and 4 October 1778, he personally wrote out and possibly personally versified an interpretation of the Old Javanese Arjunawiwāha (‘Arjuna’s nuptials’), producing the Modern Javanese Wiwaha Jarwa, the ‘Wiwaha Paraphrased’ (Wiryamartana Citation1990: 242–246). Paku Buwana III’s Wiwaha was not a direct adaptation of the kakawin. It was a rendition in tĕmbang macapat of an already existing Modern Javanese gloss. This paraphrase, in prose, had been produced at an unknown time but probably in the 17th century or earlier, and in an unknown place, possibly eastern Java (Wiryamartana Citation1990: 218–227). There are signs that it was available at the Central Javanese court by the early Surakarta period (Wiryamartana Citation1990: 219).

The colophon, short but packed with meaning, that was appended to the new poem reveals not only that the narrative of the Arjunawiwāha was prized by the king, but also that it had been subjected to Islamic scrutiny. This is remarkable. The Arjunawiwāha is undeniably of Shivaite persuasion and permeated with a religiosity that contradicted the tenets of Islam. At a high point in the story the protagonist even pronounces a hymn in praise of Shiva.Footnote45 Paku Buwana III’s step thus appears revolutionary.

What motivated it has not been recorded, but there is circumstantial information. We can infer that the time was right. As Ricklefs (Citation2018: 236) has stressed, royal Javanese histories describe drastic changes in the fortunes of kingdoms and capitals (both called kraton in Javanese, a word that also means ‘kingship’) with the arrival of a new century in the Javanese calendar. Anno Javanico 1700 began in March 1774, and Ricklefs (Citation2018: 236) suggests that the three Central Javanese rulers of the moment, including Paku Buwana III, ‘might all feel threatened by the changes which this cycle predicted’. He notes further that ‘[a]s the potentially threatening period AJ 1700–1703 came to an end in January 1778, there had been no change of kratons as the century cycle predicted’ (Citation2018: 264). A precarious period had passed eventlessly. Perhaps it was time for a fresh look at what the court’s textual heritage had to offer for the future, which remained uncertain.

The yuga theory as well as the pangiwa-panĕngĕn system condoned, even stimulated study of the kakawin, which took place inevitably from a Muslim standpoint. Indeed, the Arjunawiwāha had been subjected to Islamic readings before. Glossaries on it found in Windusana’s library refer to prominent Islamic concepts. Kurniawan (Citation2017), who studied them, mentions tohid (Ar. tawḥīd), ‘oneness, singularity’ [of God]. This is the principal tenet of Islam. It is used in a glossary in an explication of Old Javanese paramārtha, ‘the highest reality’ (cf. Robson Citation2008: 38–39). The notion of pĕrang sabil, ‘struggle on the path [of God]’, is adduced in another glossary to characterise the ‘unending praise’ (puji tanpa pĕgatan) prioritised by the narrative’s hero Arjuna (Kurniawan Citation2017: 9–10).Footnote46 As Wiryamartana (Citation1990: 392–394) has shown, in the interpretation of the kakawin laid down in the paraphrase that formed the basis of Paku Buwana III’s poem, the Deity’s will and His love are represented as key conditions for man’s very being and interaction with the Deity. Using theological terminology, Wiryamartana (Citation1990: 392) refers to a conception of the Deity that is more transcendent than immanent. Although he does not identify it as such, this was an Islamic (more precisely, Ashari) conception. Nevertheless, whilst the Arjunawiwāha had been considered from a Muslim perspective and this was reflected in the text versified by Paku Buwana III, neither the yuga nor pangiwa–panĕngĕn theory suggests that kakawin should be held up to the light of Islamic law. On the contrary, the theory of left- and right-sided traditions placed them outside Islam.

As will become apparent below, the hinge of the matter was the ascetic practice known as tapa. Since at least the 16th century this term had been used in Java to refer to Islamic asceticism (witness its use in Drewes Citation1954, Citation1969, Citation1978). Tapa was a major motif in important court texts, such as the allegorical-legendary narrative Jayanglĕngkara and the Sufistic Book of doing service (Layang Sewaka).Footnote47 But it was also key in kakawin and other Old Javanese writings. Tapa thus stood astride the buddhic–Islamic dichotomy. And as it happened, tapa was emblematised in Javanese discourse by the Wiwaha’s image of Arjuna practising asceticism in his cave on a mountain, surrounded by celestial nymphs tempting him to break his concentration. Finally, tapa as a means of maintaining dominion over land is thematised in the archaic Yogyakarta wayang exordium, referring to the Wiwaha narrative. Apparently connecting tapa to the preservation of political power was part of a hermeneutic tradition with regard to this narrative. Preservation of power was also a major point of interest in the yuga framework. Paku Buwana III may have decided to investigate whether this interest was legitimate from an Islamic viewpoint.

The Wiwaha’s colophon concludes canto XXVII:

These stanzas merit attention. I take it that the Wiwaha’s religious knowledge or wisdom – the sense of ngelmu (Ar.: ‘ilm) in the present context – is considered valid because despite its buddhicism it displays Islamic values where it matters. Line 19e’s remarkable term batal (corresponding in meaning to Arabic bāṭil) denotes ‘null and void’ with regard to acts of devotion like prayer and pilgrimage (Wensinck Citation2012). And in an early 20th century (or older) Javanese text about the doctrines of the legendary bringers of Islam, there is mention of mystical knowledge being batal because it is incomplete or imperfect (Zoetmulder Citation1935: 340–341, cf. Drewes Citation1969: 20). But based on the use of al-bāṭil in the Qur’an, where it occurs with the sense of ‘untruth, falsehood’, in 17th-century Mughal India bāṭil was also used to characterise marvellous storytelling (Khan Citation2015: 201–202).Footnote51 Dadi, which the knowledge in the Wiwaha is subsequently said to be, means inter alia ‘to succeed, turn out as expected’.

Consequently, the Wiwaha was ‘recognised’ (19c, d, f), presumably by the king and his circle, following certification by persons with the authority to declare it ‘not void/false’. The semantic range of the words that I have translated ‘recognise’ (panganggĕpe, inganggĕp) covers ‘accept, value, embrace, believe, trust’ (e.g. Gericke and Roorda Citation1901, I: 224). The qualification ‘with great delight’ suggests that there had been hope that the value traditionally accorded to the Wiwaha (as one of the kakawin patronised by princes) would be justified, but also a certain anxiety that it might not be.

An issue insistently problematised in accounts of the yuga and given further significance by a right-sided tradition about the roots of violent conflict in early human history, is what I have called the ‘women as objects of destructive rivalry at epoch’s end’ pattern. The 1778 Wiwaha colophon mentions a simple method of avoiding this issue, along with many other problems.Footnote52 It is making ‘patience, composure, a bent on peacefulness’ into a ‘fortress’ ‘for shutting away the inner drives’ (18e–h). This strategy seems banal but judging by Javanese historical lore, nobles often failed to employ it. In the context of the Wiwaha narrative, this refers to Mintaraga (the name of Arjuna as ascetic) resisting the celestial nymphs including Supraba, the lead nymph who was identified in the Yogyakarta wayang exordium as the object of strife in the pertinent yuga’s war. In the kakawin, averting the conflict was out of the question; rather quite the opposite as it was key. But it did not result in universal destruction and, perhaps most importantly, Arjuna was victorious.

As noted, Paku Buwana’s poem highlighted the importance of the Deity’s will and His love for the human being. This understanding is expressed pointedly in the colophon. Arjuna could be victorious because his tapa and his general attitude and behaviour brought him immense grace (nugraha gung, 18j). That this is grace from God is so obvious that it does not have to be stated. Arjuna’s opponent Niwata Kawaca, too, was granted power as a nugraha, in this case from Rudra (the demonic form of Shiva) who was moved by Niwata Kawaca’s self-mortification, also in the paraphrase on which Paku Buwana III’s poem was based (Wiryamartana Citation1990: 385). In the corresponding passage in the Old Javanese, the deity is kawĕlasĕn ‘moved to compassion’ by Niwata Kawaca’s ascetic practice (Robson Citation2008: 98). Tapa did not yield the desired results mechanically, but it persuaded a higher power. In this crucial field, the adaptor will have found remarkable parallels between Islamic perceptions and the buddhic representations of the Old Javanese.

Lines 19c–e focused on the validity and effectiveness of left-sided or buddhic matters in their capacity as ngelmu. This was clearly a concern for 18th-century thinkers. Line 19f signals the second key element in the Wiwaha’s acceptability: affairs of state and kingship. That these matters and kakawin were somehow connected is tangibly clear from the production of valuable manuscripts for and by heirs apparent, other princes, and high officials throughout the 18th century. Here, finally, we see an articulation of the nature of the relevance.

The kingdom (19f) is immediately characterised as the location of the wahyu, followed at once by an expression of concern that the wahyu should remain where it is. Wahyu is a gift from God that, to put it very simply, has two sides. One is an exceptional and desirable quality, in the present case that of kingship. The other is a revelation. (Arabic waḥy means ‘revelation’, for instance that of the Qur’an to the Prophet Muḥammad, who then revealed it to humankind.) The two senses are connected.Footnote53 Where the wahyu of kingship should remain was, of course, in the ruler. These statements in the colophon (addressed to ‘His Majesty’s children and grandchildren’, 18a) respond to the perennial uncertainty about the future of authority laid down in yuga theory. As I have argued, there was hope that the kakawin could provide useful information in this field. Indeed the Wiwaha turns out to promote a means of wahyu acquisition and preservation, which was evidently effective in Arjuna’s case: tapa. A remedy to the risk that in the Kaliyuga, the reigning kings would lose their dominion, was holding on to kingship’s wahyu, a grace from God. A wahyu was right-sided and therefore superior to anything in yuga theory. Any challenge to it therefore had to be in terms of the Mahdi, a panĕngĕn figure. This is the logic that Prince Dipanagara had endeavoured to translate into action 60 years earlier.

The colophon ends by thematising two kinds of what in English is called power. In late 18th- and early 19th-century Javanese, sĕkti (19i) and its derivative kasĕkten denoted ‘inner supernatural, miraculous power, potency’. It can be ‘brought out’, particularly for application in conflict. This form of power is often generic but can be specific too, for instance the ability to psychologically enter other persons and things. Those that possess it are typically people and supernatural beings, but weapons are also said to have sĕkti. Given its etymology (the Sanskrit word śakti), Javanese sĕkti might seem to suggest something exclusively un-Islamic, but that conclusion would be mistaken. It occurs unproblematically in thoroughly Islamic texts, for instance the Caritanira Amir (Gallop with Arps Citation1991: 77) of around 1600, where sakti is an attribute of a professional burglar (alternating with aguna ‘supernaturally skilled’) and Amir Hamza’s trusted companion Umarmaya is said to possess kasakten.Footnote54

Prabawa in 18th-century Javanese was primarily ‘energy, magical power, force (sometimes vehement), violence’. It is a property of the same kinds of personages and weapons as sĕkti, but it emerges from them into the world, where it is active, radiates, and, in extreme cases, rages and creates havoc.Footnote55

Wiryamartana (Citation1990: 383) stresses that in the Wiwaha paraphrase used for Paku Buwana III’s text, Arjuna’s sĕkti is linked strongly to tapa, far more so than in the Old Javanese. Indeed Arjuna’s kasĕkten is thematized prominently in Paku Buwana’s poem. It is the idea with which, after a characterisation of the Old Javanese author, the story proper begins (Gericke Citation1844: 4, stanza I.13). The fact that Arjuna receives supernatural abilities from the gods, as a grace (nugraha), is emphasised in passages of Paku Buwana III’s poem that were not in the paraphrase (Wiryamartana Citation1990: 404–406). The theme of sĕkti recurs in the colophon. It literally frames the narrative in the king’s manuscript of 1778.

The physical method of striving after inner potency by subduing the senses is described in detail in the king’s text, with use of amongst others, the term yoga (which in the paraphrase that was the exemplar was equated with tapa; Wiryamartana Citation1990: 389). Borrowing from the gloss (Wiryamartana Citation1990: 384), the poem describes the posture and gestures of the meditating Mintaraga and reproduces their Old Javanese name (Gericke Citation1844: 24–25). The corresponding scene in the kakawin (Robson Citation2008: 48) is much shorter and lacks the detailed clarification which the macapat borrowed from the gloss. Clearly the practice of meditation, and even its technical terminology, was of interest in early modern Java.

It is a subject of repeated discussion in the poem whether for a prince the goal of tapa should be superior strength in battle or, like for a pandit, release. It becomes clear that Arjuna chooses – indeed, must choose – the former. A major point of the narrative is then how Arjuna, through tapa, is granted the power to oppose and defeat Niwata Kawaca. The inner potency and power of violence that bring the text to its conclusion are central to the story. They were also valuable to Javanese kings and princes who wanted to hold on to sovereignty, or gain it. Muslims could learn about sĕkti and prabawa and their means of acquisition from the Wiwaha.

Conclusion: the programme

The surprising acceptability and superior features of the Wiwaha seem to have whetted the king’s appetite for Islamically valid texts from the buddhic literary canon. A modernised version of the Old Javanese Arjunawijaya was inscribed and probably composed at Paku Buwana III’s behest, also in 1778. According to his son Yasadipura II, who was 22 years old when he observed this, the adaptation was made by Yasadipura I. He set to work just one day before the king finished writing the Wiwaha. At His Majesty’s urging, he finished the adaptation in haste (Arps and van der Molen Citation1994: xxxiv, McDonald Citation1983: 60). It is implausible that the correspondence of dates is a coincidence. After the Wiwaha the king wanted more, and he wanted it quickly.

As noted, the Old Javanese Rāmāyaṇa, Bhāratayuddha, and Bima Suci, reputedly also commissioned by Paku Buwana III and ascribed to Yasadipura I, followed over the course of the next decade. In retrospect, these adaptations of five epic kakawin formed only a first batch. In 1798 the Nītiśāstra followed, in the archaic verse forms called tĕmbang kawi (‘kawi verse forms’) or tĕmbang gĕdhe (‘big verse forms’). This was succeeded in the early years of the 19th century by several reversifications of kakawin in the same kawi verse forms, but on the basis of the earlier renditions in macapat (McDonald Citation1983). These are attributed to Yasadipura but without specifying the elder or younger. In the mid to late 1810s there was a new batch in tĕmbang macapat, attributed with certainty to Yasadipura II (1756–1844) and dedicated to the crown prince, who later became Paku Buwana V. In 1815 Yasadipura II adapted the Dharmaśūnya for the first time, in 1819 he reworked and completed his father’s Lokapala, and also made new renditions of the Nītiśāstra (Sudewa Citation1991), and possibly added to other earlier kakawin adaptations as well. After several decades there came another installment of the series of modern works that went back to kakawin, in Surakarta in 1846. This was a rendition (not the first) of the Old Javanese Bima Suci in archaic verse forms (Prijohoetomo Citation1934: 145). In the early 1900s several versified renditions were made of other Old Javanese texts that had recently been studied by philologists (examples in Florida Citation2012: 211–212). It must be assumed that the motivations for these interpretations changed with time and context. They should be investigated.

I have tried to make a start for the first kakawin to be adapted. The Wiwaha’s colophon identifies a complex combination of buddhic knowledge compatible with Islam, divine grace, kingship, inner potency, and power of violence. The colophon also describes a logic behind this combination, centred on tapa. Coupled with theoretical ideas about the buddhic heritage, the colophon and marked features of the adaptation suggest that the programme of reinterpreting the Old Javanese epic kakawin, as it began in 1778, was about a quest for inner and external power, knowledge and revelation, and future kingship. It needs to be explored whether these broad themes were indeed among the focal points of interest in the Islamic hermeneutics of the other epic kakawin in the ensuing decade.

Acknowledgements

For critique, questions, and references I thank Edwin Wieringa, Els Bogaerts, Nancy Florida, Ronit Ricci, Tony Day, Willem van der Molen, and the other members of the research group New Directions in the Study of Javanese Literature at the Israel Institute for Advanced Studies (2018/2019). My membership was co-funded by the IIAS and the Marie Curie Actions, FP7, in the framework of the EURIAS Fellowship Programme. Andrea Acri, Verena Meyer, and an anonymous referee helped to remove clutter and sharpen the argument.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Note on contributor

Bernard Arps is fascinated by worldmaking through performance, texts, and media, particularly in religious contexts in Southeast Asia. Currently Professor of Indonesian and Javanese Language and Culture at Leiden University, his most recent book is Tall tree, nest of the wind: the Javanese shadow-play Dewa Ruci performed by Ki Anom Soeroto; a study in performance philology (Singapore: NUS Press, 2016). Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 See Ricklefs (Citation1978: 153, 1993: 364); McDonald (Citation1983); Gallop with Arps (1991: 86–87); Arps and van der Molen (Citation1994).

2 My translation from the Dutch.

3 See Ricklefs (Citation1978: 153 n. 12; 1993: 364 n. 56).

4 As noted in a version of the Book of Cabolek (Sĕrat Cabolek), set in the 1730s. The oldest dated Cabolek manuscript in which this recollection is mentioned is DFT S 240/280-18 (p. 74), written in 1839 (Ricklefs Citation1998a: 322), although the text in this manuscript may, of course, be older. The passage in question is not in Soebardi’s edition (Citation1975), a composite from different versions. It does occur in Jayasubrata (Citation1885: 75–76). The Cabolek gives a fascinating account of discussions around kakawin in the Kartasura court (Ricklefs Citation1998b: 127–162), but because the text has several as yet unextricated versions, and to the extent that it is datable, it seems to present a perspective formulated in late 1788 or 1789, I have not used it for my reconstruction of ideas about religions in the first three quarters of the 18th century.

5 This crown prince was probably Prince Buminata, Paku Buwana III’s uncle, appointed to the position in 1749. He left the court and rebelled in early 1753 (Ricklefs Citation2018: 126).

6 The codex, MSS Jav 8 in the British Library, contains two manuscripts. The first, the latter half of which is severely damaged, ends with f. 135v. It is this manuscript that is of interest here.

7 MSS Jav 8, ff. 18r, 29r, 36v, 38v, 40v. On f. 40v the addition, in archaic script, ‘from his father the venerable noble Sir’. A name is lacking. My reading saking ikang rama Kajĕng Kiyai Riya is tentative.

8 Or Muhyadin and Mukyadin, common Javanese spellings of variants of the same Arabic name.

9 For reasons unknown, the second half of the manuscript which contained the Bima Suci, Sewaka, Wiwaha, and other texts has been ripped out.

10 The term buda designates a property of writing (buda mĕliking sastra ‘the writing’s sparkle [i.e. characteristic?] was buddhic’) in a narrative in an East Javanese manuscript dated 1738 (Schoemann II 18 f. 100v; described in Behrend Citation1987: 40, 45), a historical period (duk ing buda ‘in buddhic times’) in the Wiwaha versified at the court of Surakarta in 1778 (Gericke Citation1844: 1), a religion viewed historically (agamane maksih buda ‘the religion will still be buddhic’) in a 1795/1796 manuscript of a mythological narrative (Add MS 12316, f. 43v), and a religious system (agamane tata buda ‘their religion was of the buddhic system’) in the same text (f. 44r) as well as another version (MSS Jav 71 in the British Library, f. 23r) datable on circumstantial evidence to 1782 or earlier, although the manuscript is probably from 1812 (Weatherbee Citation2018: 93). Buda is an adjective. Etymologically, its substantival counterpart means ‘(the) Buddha’. In Old Javanese, the adjective was boddha, ‘Buddhist’.

11 Awignam astu namas siddhi (MSS Jav 8, f. 88r). Siddhi is likely to be a variant of sidhĕm (from Sanskrit siddham); cf. footnote 31.

12 Day discussed Javanese poetic values in the early 19th century, but I believe this principle was followed also at the courts in the 1770s.

13 Ricklefs (Citation1997) has emphasised that there is no contemporary evidence of Yasadipura I’s authorship of these (and other) works.

14 These are appellations of the susuhunans of Kartasura and Surakarta and the sultans of Yogyakarta.

15 A broad-stroked but comprehensive theory of religions was composed from these notions (possibly in 1777 in Yogyakarta, definitely before 1796) in the shape of a narrative (inter alia in Add MS 12316). Lack of space compels me to leave this for later discussion. It possibly became known in Surakarta only when the kakawin adaptation programme was well underway.

16 Some sources are as follows. The distinction is stated or implied with regard to aksara ‘script, characters’ and wisik ‘secret instructions’ in the Suluk Wujil (Poerbatjaraka Citation1938: 148). At the Kartasura court in 1730/1731 there was a pangiwa specialist with duties such as observing omens and portents, divination, and protective magic (Arps Citation2016: 520). For left-sided and right-sided noble genealogies see de Graaf Citation1970 and Kouznetsova Citation2006 (both of whom identified them as ‘secular’ versus ‘spiritual’), and Mangku Nagara I’s historical notes of 1769–1771 (Ricklefs Citation2018: 246–247).

17 As implied in Sêrat Cênthini (Citation1986: 160). However, among the dedications documented in the diary studied by Kumar (Citation1980a: 15–16), only Islamic figures appear, and some living ones who were presumably Muslims.

18 For instance in the 16th-century text edited by Drewes (Citation1969: passim) and several of Ratu Paku Buwana’s texts written in 1729–1730 (Ricklefs Citation1998b: 68–69, 80, 82, 85, 111).

19 Left-right theory remained prominent into the 19th century. See especially Kumar’s discussion of Yasadipura II’s Sasana Sunu (Pedagogic Precepts), composed in 1819/1820 (Kumar Citation1997: 404–405).

20 In the alternative contrasts involving kafir in the 18th century, Christianity could be given a place (e.g. Ricklefs Citation1998b: 68–69).

21 As gracefully noted by an anonymous reviewer. See especially Qur’an 56: 9, 41 and 90: 19.

22 Sang Yyang Tugal Guru putranekī Guru ika apuputra lilima [one supernumerary syllable, BA] / [ … ] / Wisnu wuragilira / Kang jumnĕng ratū Angadĕg ing tanah Jawa [/] Pan kinarya titibanganing agamī Islam nagareng Arab (MSS Jav 33, ff. 9r–9v). The phrasing in the Babad Kraton from Yogyakarta, written 1777–1778, is similar (Add MS 12320, ff. 8r–9v). Judging by Gordijn’s Dutch translation, the nature of the balance differed somewhat in the Sajarah Raja Jawa manuscript that Gordijn bought from his aged Javanese teacher Sutrapana in Surakarta, 1750 (van Iperen Citation1779: 135). Here Wisnu was the first king of the divinities (‘alle de Dewas, of Heiligen’) and equal to the Islamic king of Arabia (van Iperen Citation1779: 139–140).

23 [ … ] / Jarwaning wisik aksara tunggal / Pangiwa lan panĕngĕne / Nora na bedanipun / Dene maksih atata gĕndhing / Maksih ucap-ucapan / Karone puniku (Poerbatjaraka Citation1938: 148). Both buddhic and Islamic texts were read aloud, the versified ones with melodies.

24 Isbat iku pon asal nafi / Nafi pon asal isbat / Musbat kang denrĕbut (Poerbatjaraka Citation1938: 159).

25 In ancient India, texts about the yuga self-presented as predictions regarding the present and recent past but hailing from a distant past (Pollock Citation2006: 70–71). In Java in the 18th century (and the 19th century; see Florida Citation1995) some of them functioned as predictions of the present’s future.

26 Baksaha is not a known numeral. It may be a slip of the pen for laksa ‘10,000’.

27 sakwehning waniteng yuganta kaharĕpnya mangka karanani prang atbuta (Ms. Or. fol. 402, p. 41). Poerbatjaraka’s edition reads almost identically (1933: 48) whilst Drewes (Citation1925: 164) translates away the cynicism.

28 The same is suggested, for a later period, by the fact that the translation from Raffles (Citation1817, I: 264–265), of the same stanza, invokes yet other elements not in the Old Javanese.

29 Van der Tuuk (Citation1897: 699, 500) identifies her – under the names of Reṇukā or Aniruka – as an object of strife in an episode preceding the Rāmāyaṇa, mainly on the basis of the Old Javanese Caṇṭakaparwa, a compendium of mythic lore and Old Javanese lexicography known from Bali and Lombok, and the kakawin Rāmawijaya. This was possibly composed in Bali (Zoetmulder Citation1974: 402–404).

30 The text, written on Javanese paper, is in MSS Jav 27. There is a note in another codex also taken from the Yogyakarta court in 1812 that a play script written on Javanese paper was copied onto European-made paper (MSS Jav 19, f. 68r), while the datings of the preceding script (on European paper) in the same codex suggest that this happened in 1781/1782 (ff. 49r, 67v). The play script of MSS Jav 27 contains several archaic elements that corroborate an early dating.

31 Awignam astu nama‹s› sidhĕm (MSS Jav 27, f. 69v, likewise in false starts on ff. 67av and 68v). Other dance-drama scripts from the 18th-century Yogyakarta court also begin with variants of this invocation (e.g. MSS Jav 4, f. 74v).

32 An image of considerable antiquity, evoked in different form in the exordium of Balinese shadow play (Zurbuchen Citation1987: ix, 268). The Javanese and Balinese traditions of shadow play probably lost direct contact in the 1500s. A similar image occurs in Old Javanese and Old Sundanese texts from the 16th century and earlier (Gunawan Citation2017: 10).

33 kawula gusti, gĕdhe cilik tuwa anom, lanang wadon ala bĕcik (MSS Jav 27, f. 69v). Note that left and right are not included, unsurprisingly, as this is a left-sided text. While gĕdhe cilik means ‘big and small’, it is often used to indicate social hierarchy: ‘noble and common’ or ‘high and low’.

34 Named explicitly in two cases and comfortably taken for granted in the other two.

35 wong ala jumnĕng bopati (Ms. or. fol. 402, p. 40). This is part of the paraphrase of stanza IV.7 in Poerbatjaraka’s edition (1933: 44). The order of stanzas is partially different and the manuscript contains fewer stanzas.

36 benjing Kaliyoga buwana iki gonjing-gonjinge Sang Ratu ilang kadunyane tka karatone (Ms. or. fol. 402, p. 40), from the paraphrase of Poerbatjaraka’s stanza IV.8 (1933: 44–45).

37 Key characteristics ascribed to the different yuga in this text also occur in a 1795/1796 Yogyakarta copy of a mythological narrative, although without the reference to the Prophet (Add MS 12316, ff. 35r–37v).

38 Other manuscripts in Windusana’s library also contain the same text or part of it. None of them is dated (Setyawati et al. Citation2002: 115, 177, 198).

39 Punika nusa Jawa, makseh kapir (Brandes Citation1889: 383).

40 jaman iku muli [sic] kadi ing Trita (Brandes Citation1889: 385, 387). For the year the manuscript reads sewu wongatus (Brandes Citation1889: 384), an error that Brandes (Brandes Citation1889: 387) emends into sewu wolung atus (1800). The occurrence of Hijri 1200 in the second text treated by Drewes (see above) makes sewu rongatus (1200) more plausible.

41 Perhaps more so than the schema’s explicit utilisation, which may have had the purpose of pushing a new or marginal idea.

42 Despite the apparent contradiction, the Story’s prediction that ‘the times will revert to a condition like the Trita’ actually confirms this.

43 Serat Kandha Citation1985:1. Ras (Citation1992:293) dates this work to the period 1700–1710.

44 I am thinking of the romances centred on Princess Lĕmbah in the 1690s and events involving the Lord of Madura Cakraningrat III’s daughter and wives in 1718. These are described in Babad Kraton, the former in extensive detail (Ricklefs Citation1993: 118–121, 172).

45 See Robson Citation2008: 68–71. Paku Buwana III’s versified paraphrase – which refers to Shiva as Sang Hyang Siwah (Gericke Citation1844:61) – and a Dutch translation are in Berg Citation1933: 212–217 (cf. pp. 220–225 for a comparison with the Old Javanese original).

46 Kurniawan (Citation2017: 10) does not identify the locus in the Arjunawiwāha to which the latter explication pertains. Was this XII.2–3 (Robson Citation2008: 70–71)?

47 Both texts are in Prince Purbaya’s collective manuscript of 1736/1737 (Ms. or. fol. 402).

48 The chronogram her muksa gora-goraning bumi (‘the water vanished as the earth was roaring’) denotes 1704 AJ (1778 CE). Kuruwĕlut is one of 30 seven-day cycles (wuku), which in 1704 fell in early October 1778.

49 Wiryamartana (Citation1990: 407–408) interpreted lines 19c–g as predicates to a generic person of high standing rather than to the Wiwaha which is actually thematised in 19b.

50 The reading ora bakal ‘won’t’ is odd syntactically and semantically, unlike ora batal ‘not void’ in another copy of the text (Wiryamartana Citation1990: 240).