ABSTRACT

This article examines the role of food and food-related activities in a Mentawai society on Siberut island (West Sumatra, Indonesia). In particular, it deals with gardening, the main Mentawai activity for producing food, and its relation to the construction of Mentawai personhood. Gardening is a set of activities through which the Mentawai produce and reproduce themselves and others. It is the principal activity within a total process of constructing valued persons and sociality, rather than merely being the production of material substances. Mentawai foodways, therefore, offer vital clues to personhood and illustrate that food and food-related activities are transformative agents in the process of social production and sociality.

Food, personhood, and sociality

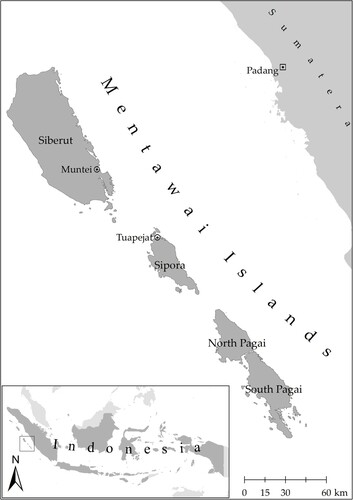

In the context of Southeast Asia and beyond, food is neither simply something to eat nor something to think with. Many studies have shown that food is a transformative agent in the process of generation and regeneration, actively involved in social transactions and exchanges as well as contributing significantly to a wider process of social production and reproduction (Mintz Citation1985; Carsten Citation1995; Fajans Citation1997; Janowski Citation2007b; Poser Citation2013; Chao Citation2021). This article aims to shows that food is an active agent and has ability to mediate human actions aimed at constructing themselves and generating sociality (Munn Citation1986; Fajans Citation1988; Carsten Citation1995). The article is based on ethnographic research with the Mentawai, an indigenous people living on Siberut island ().

The article moves beyond two established theoretical endeavours and approaches known in food studies: the materialist, which looks for causal explanations, and the structuralist, which is symbolic and interpretive (Mintz and Du Bois Citation2002; Counihan and Esterik Citation2012), to show that food is an active substance for social processes. Both materialists (Harris Citation1985; Harris and Ross Citation1987) and structuralists (Lévi-Strauss Citation1966, Citation1970; Douglas Citation1984; Kahn Citation1986) have provided brilliant analyses of the various roles food plays in human life. While these two approaches use opposing arguments about food and society, both share a basic assumption about the role of food. Firstly, they see food as a passive agent upon which human actions and intentions have little influence. In the materialist approach, human actions are responses to given ecological circumstance. The structuralist approach sees food as an abstract category that makes up a larger code of meaning. Secondly, both approaches have little time for the role of food as a life-giving substance that humans use to build, maintain, and change social relations; and they overlook the historical and processual aspect of creating social reality (Vayda Citation1987; Graeber Citation2001: 20).

The framework deployed in this article derives from an approach that focuses on human action (Ingold Citation1996, Citation2011). It has been termed value theory (Munn Citation1986; Graeber Citation2001). The main differences between this and the two abovementioned approaches lie in the centrality of human activities (Graeber Citation2001, Citation2013) and the importance of the material world in shaping human sociality (Ingold Citation1996). The focus on human activities and the role of food in constituting sociality offers a different lens through which to see the relations between food and humans. The structuralist and the materialist approaches start with a notion of ‘society’ and a ‘sociocultural system’ (Graeber Citation2001: 24–25), then ask how the availability of food or a mental map of food holds society together. However, a dynamic approach begins by asking how ‘society’ and ‘sociality’ is continually being constituted and transformed through the actions of different social actors (Ingold Citation1996: 47; Graeber Citation2001: 26). The emphasis on human actions and processes provides analytical tools for re-thinking and understanding the importance of food and food-related activities in social transformation.

This article deals with food-producing activities, primarily gardening, and their roles in the social relationships of the Mentawai. The ethnographic materials deployed here focus on people’s actions rather than the product of those activities. Thus, this article does not reveal what food ‘really is’ for the Mentawai. Instead, it explores how food enables them to mediate their relations with their surroundings through a wide array of imagined and intended actions: gardening, feeding animals and other humans, circulating, exchanging, keeping, and sharing. I argue here that producing sago or keeping pigs both construct social actors and embody social value, which in turn orient feeling and generate and motivate social actors to enact social relations. In other words, food is an active medium of sociality. It is part of ‘the process of relating to others through action’ (Sillander Citation2021: 2) in which human and non-human entities take part in the mutual process of becoming (Ingold Citation2000; Lounela Citation2021). Through food-producing activities, the Mentawai not only satisfy their material needs; but they also simultaneously produce themselves and others, and create social values (Munn Citation1986; Graeber Citation2001). Hence, food-related activities are all at once material, social, and imagined. The focus on human activities and the importance of food materiality will bring us closer to understanding the processual aspects of personhood construction, the dialectical procedure involved in creating social value and the dynamic aspect of sociality.

The site and the people

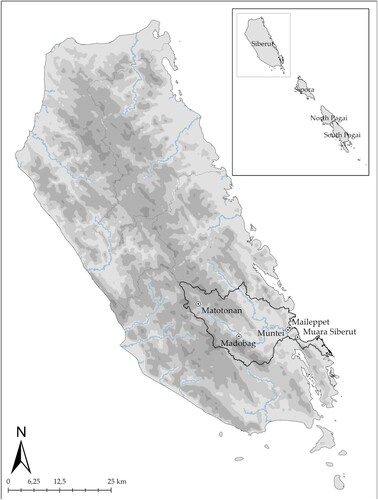

This article is based on 15 months of ethnographic research among the Mentawai living in the Siberut Selatan sub-districtFootnote1 that comprise five main villages. Muara Siberut, Maileppet and Muntei are villages located in the coastal zones, around the Sabirut river, while Madobak and Matotonan are situated upstream along the Rereiket river (). Siberut Selatan is home to around 9,500 people of whom the majority are indigenous Mentawai (8,000) while the rest are migrants from mainland Sumatra (Minangkabau, Batak and Nias) and Java who are almost all living in the enclave village of Muara Siberut and working as fishermen, traders, and civil servants (BPS Mentawai Citation2017). While there is a substantial number of migrants on the island, this article focuses on the indigenous Mentawai who are not homogenous. They have different sub-cultures (e.g. language dialects, rituals, housing) and live in varying landscapes (e.g. coastal areas, hinterland). However, these internal variations are insignificant in relation to the ways people produce food.

The Mentawai in South Siberut (hereafter the Mentawai) are socially organised in uma: autonomous, patrilineal, and exogamous groups that structure their religious rituals, political decisions, and land-owning units. Uma is a generic term for the Mentawai, equivalent to the anthropological term ‘kin group’ or ‘clan’. It connects group members, both living and dead, to each other, through bonds of bodily substances (most notably by blood) and through claims to land. An uma may consist of only one or dozens of nuclear families (lalep), totalling from two to a hundred or so individuals. Social relations within and between uma are strictly egalitarian. There is no hierarchy between members apart from variations based on skills or age. There are no political leaders and all decisions are ideally taken after reaching a shared decision. Every man and woman can perform the tasks necessary for making a living on the island. The only exception is the shaman (kerei), who performs specific tasks with respect to relations between humans and the way they deal with the spirit world. Traditionally, each uma lived on its land in a large communal house (also called the uma) along the banks of the main rivers that cut through the dense tropical lowland rainforest in the hilly landscape. However, over the last seven generations, they have largely lost any geographical autonomy they once had. Internal quarrels and migrations, exogamous marriage, the need to find places to grow cash crops and waves of external pressure (resettlement projects, government infrastructure) have caused uma and its members to disperse and settle in other territories (Tulius Citation2012; Darmanto Citation2016). They are all now living in government settlements while retaining important rituals and political autonomy.

The Mentawai obtain food from various gardening activities. Sago (Metroxylon sagu) has always been a staple while taro and bananas have contributed significantly to daily nourishment. They assert that all sago on the island is cultivated and claimed by a certain person or uma, and never grown spontaneously. Pigs and chickens are two essential sources of protein that are only served and consumed during communal rituals. Women collect small fish, shrimps, and mussels from surrounding freshwater areas and grubs from the sago gardens for daily protein. In the coastal villages, saltwater fish is available regularly in the market and is sold mainly by Minangkabau fishermen. Small mammals (squirrels, civet cats, flying fox) are other sources of protein hunted occasionally around gardens. Game animals both from the forest (primates, deer, feral pigs) and the sea (dugong, turtles) are desirable for their protein, but are now rarely obtained. Hunting activities have become rarer in recent times and are only organised after a very important ritual. Small amounts of cassava and taro leaves or the shoots of wild ferns are occasionally gathered for meals (especially if there is no meat), but in general vegetables are a rare sight in daily meals. Durians, jackfruit, langsat and mango are important fruits available seasonally from the forest and home gardens. There is evidence that demonstrates a common and widespread – if not identical and universal – pattern of food production throughout the Mentawai islands. The Mentawai continue to cultivate sago and taro, make forest gardens, tend pigs and possess cultural and social attributes that resemble the general features of other Mentawai communities as described in the past and in recent times (Loeb Citation1928; Nooy-Palm Citation1966; Schefold Citation1973, Citation1991; Persoon Citation1994; Bakker Citation1999; Reeves Citation2001; Hammons Citation2010; Tulius Citation2012; Eindhoven Citation2019; Darmanto Citation2020).Footnote2

There are some similarities between Mentawai cultivation and food production and those of their neighbours in mainland Sumatra and Austronesia, who are primarily rice cultivators (Blust Citation1976; Bellwood Citation2004), but there are also significant differences. The most important difference is that the Mentawai do not rely on rice or any other grain, but rather on tubers and sago as their staple starch food. Hence, the Mentawai have been and remain primarily vegetative rather than seed propagators. In the ethnographic literature, a sago or tuber agricultural regime is widely associated with notions of continuity between nature and culture (Coursey Citation1978; Ellen Citation1999), in contrast to rice cultivation that marks a sudden change of nature-culture relation and the ability of humans to transform nature (Barker and Janowski Citation2011: 7). The Mentawai place great practical and symbolic emphasis on sago palm which is, in their popular story, associated with the child. Such a view is reinforced by the highly dependable character of sago as a staple. Sago and tubers can compete with grass and weeds, provide a stable output, subject to little fluctuation, and are resistant to pests and disease (Flach Citation1977; Persoon Citation1992). Further, the Mentawai agricultural regime does not share the essential features of rice cultivation found throughout Southeast Asia, such as the need for cooperative labour (Bellwood Citation1996), the production of hierarchical status and social difference (Janowski Citation2007b; Barker and Janowski Citation2011) and the use of fire (Mertz et. al. Citation2009; Ellen Citation2012).

Another difference between them and ethnic groups on the mainland is that they do not have a bovine culture but what has been described as ‘a pig culture’ (Persoon and Iongh Citation2004: 141). For the Mentawai, pigs are the most important animal because they are only consumed at a ritual feast (along with chickens and wild game). Mentawai pig keeping is not intensive and ‘basically semidomesticated’ (Persoon Citation2001: 72), allowing the swine to freely roam around the sago garden, fruit garden, and forest, and only called when the owner feeds them once or twice each day with sago piths. Cosmologically, the origin of pigs came along with the origin of shamanism and the Mentawai cultural order (Hammons Citation2010: 39). Pigs enable humans to have reciprocal relations with the world of spirits. They are a source of social prestige and mark the status of a person. Pigs are the ultimate measure of one’s productive activities and become the means of one’s integration into his or her group as the individual consumption of pork is strongly prohibited (Schefold Citation1982). Live pigs are slaughtered and sacrificed and pork is eaten and offered to the spirits at communal feasts, integrating people into a contrastive totality (the uma). Interestingly, the Mentawai do not consume pork from wild or domesticated pigs as a complementary food to rice, as is common throughout Southeast Asia (Barker and Janowski Citation2011: 8), but only with taro and sago at ritual feasts.

As do many rice cultivators in the western part of Indonesia and beyond (Hanks Citation1972; Barker and Janowski Citation2011), the Mentawai rely on undomesticated spaces (especially forests) to create gardens, and on wild resources for food. Their food cultivation involves strong connections with ‘life forces’ from undomesticated and non-human entities. Like many rice growers who have maintained animistic and spiritual association with forest spirits, the Mentawai still depend on the forest, both on the spiritual and practical level. They also rely heavily on wild food sources to complement their staples – especially those gathered from undomesticated spaces such as small fish, shrimp, and various mussels and clams. However, wild plants and domestic vegetables are not an important part of the Mentawai diet. Only recently have they become side dishes in rice meals alongside seafood and imported spices like chilli. If fish or other types of meat are unavailable, they often eat rice with vegetables boiled in spiced coconut cream.

In the Mentawai cosmology, the Mentawai and rice-cultivating peoples on mainland Sumatra were originally siblings (Bakker Citation1999), forest cultivators and pork eaters, but a squabble over pork forced one sibling, the younger brother, to break away. He moved to a foreign land and learned how to read and cultivate rice, eventually forgetting how to keep pigs and work in the forest. Remaining in the forest, the older brother became the ancestor of the Mentawai while his brother became the ancestor of the mainland people of Sumatra. The mainland people have gradually settled in the homeland of the Mentawai since the early 20th century and have brought rice, sugar, as well as canned and instant foods.

Decades of external intervention from missionaries and the government, as well as intensive relations with the neighbouring Minangkabau, have contributed to the growing importance of rice in recent times. The Minangkabau grow and consume rice and have developed a sophisticated culinary tradition based on rice meals. For the Minangkabau, eating taro and sago is a symbol of backwardness and underdevelopment, while eating rice is evidence of their claimed cultural superiority (Persoon Citation2002: 446). The Mentawai describe rice as ‘tastier’, ‘cleaner’ and easier to prepare, but show little enthusiasm in following the Minangkabau and developing their own rice cultivation (Darmanto Citation2022). Some of the younger generation aspire to become rice growers, cultivating cash crops for export and abandoning sago cultivation and pig keeping. However, the majority of of the Mentawai see rice cultivation as requiring intensive labour, that is not suited to their social rhythm and cultural values. Thus, forest-based food production and an orientation towards gardening sago, taro and fruit trees remains intact and still underlies schemas and general patterns of Mentawai food production. In avoiding rice cultivation, the Mentawai aim to preserve their autonomy and egalitarian values, rejecting the hierarchy associated with rice cultivation throughout Southeast Asia (Barker and Janowski Citation2011).

Making gardens, defining humanity

The Mentawai are still primarily horticulturalists and cultivating the forest is central to the definition of their humanity. They differentiate themselves from animals and other entities (the spirits, trees, animal) by the fact that they create gardens from forests and produce their own food. Transforming forest into fruit gardens, sago and coconut groves is an activity that converts undomesticated space into socially and culturally transformed spaces. Human energy and time that go into a garden are central to their definition of work (galaijet). Gardening (mumone)Footnote3 is the immediate answer when the Mentawai are asked, ‘What do you do for a living?’ Gardening involves clearing an area of forest, slashing weeds, planting fruit trees, raising pigs and chickens, cultivating a combination of staple, cash, medicinal and ornamental and other useful plants. The result of mumone activities is mone, a cultivated area generally containing a combination of tubers, sago and fruit trees, domestic animals, or combination thereof. Physically, mone is a forest garden that is closer to the Indonesian term kebun or the English term ‘garden’ than to a field in which grain such as rice is cultivated.

While gardening is an activity directed at food and/or cash crop production, it also defines the relationship the Mentawai have with their environment. The Mentawai call themselves sipumone, which can be translated as ‘one who cultivates the forest’ as they carry out various activities to obtain food from the surrounding environment: gathering, fishing, foraging, and, in the recent past, hunting. They have specific terms for these activities.Footnote4 They do not, however, identify themselves as hunters or fishermen.

The main difference between gardening and other food production activities is the division of space. The Mentawai see the surrounding environment as a vast resource containing edible and non-edible animals and plants that can be extracted. All the land, rivers, caves, waterfalls, small lakes, mangroves, and other specific ecosystems have been occupied, named, claimed, and exploited. They developed those ecosystems and classified them into specific zones (human settlement, forest, fruit garden, sago grove, small islets, the sea), according to the objects or species cultivated or extracted from them, the aims and methods of appropriation, and their arrangement. Despite the diversity of all these productive zones, generally each zone consists of a series of dual components. Firstly, there is the distinction between a residential environment occupied by humans and an exploited environment containing resources extracted by humans. Secondly, there is the distinction between an intensive human-induced space and a diffuse human-induced space, which depends on the amount of human presence and activities. Thirdly, there is the distinction on the nature of their exploitation, between domesticated and non-domesticated zones. These dual components are parallel but not identical. The parallel of the residential, the intensive man-induced environment, and the domesticated, points to the constant presence of humans, the presence of residential places, and the intensity of human activities. The exploited, non-domesticated, and diffuse human-induced environments are characterised by the domination of undomesticated and exploited resources, the absence of houses, and by having less time and human activities spent on them.Footnote5

Mumone takes place in domesticated places (forest gardens, sago and taro gardens), while hunting, fishing, or gathering occurs in non-domesticated spaces (forest, rivers, the sea). Sago, taro, and forest gardens are bounded spaces where humans invest their labour and time in cultivation. With the regular presence of humans and constant cultivation activities, a forest or sago garden is not seen as a wild space. The garden is a place where humans socialise and interact. Hence, human actions and social activities that transform the spaces are key factors. In contrast, forest, rivers, or the sea are realms that have not yet been transformed by human activities. While these are an important spaces containing valuable food resources, they are not human spaces. They are considered to be the places of spirits and are strongly associated with death and danger (Reeves Citation2001). Forests belong to sikaleleu (the spirit of the forest), while everything in the water belongs to sikaoinan (the spirit of the water). Sikaleleu guard wild boar, deer, monkeys, and uncultivated plants while sikaoinan guard fish, turtles, dugongs, clams, mussels, and are associated with crocodiles (Schefold Citation2002). All resources in these spaces may be taken by humans, provided that a ritual asking for permission (panaki) from the spirits is first performed.

Despite people appearing to divide their spaces between domesticated and non-domesticated zones, natural and cultural sites, the place of humans and the place of spirits, these zones are defined not by a static dichotomy but in relative terms, according to the opposition and dynamics between their elements and crucially, the degree to which the spaces are transformed. The differences between domesticated and non-domesticated spaces are the human actions and social activities that transform them. Non-domesticated spaces are defined as realms that have not yet been transformed by human activities. Constant human intervention in undomesticated spaces transforms the natural world into a domesticated space.

The idea of gardening as essential work can be seen in how people perceive the labour invested, and the set of intellectual actions involved in the transformation of non-domesticated spaces into a domesticated one. Making sago and fruit gardens requires a set process of thinking, imagining and transforming spaces. Hunting and fishing, too, require acts of thinking and imagining. Planning and cooperation are important aspects of hunting rituals. In most cases however, hunting and fishing are carried out over a short time and in opportunistic ways. Moreover, even the result of a well prepared hunting expedition is unpredictable and unreliable as it is not solely dependent on human intentions and planning.Footnote6 Even in hunting rituals, the anticipated result is not always achieved and the expedition may differ from what was meticulously planned. More importantly, hunting and fishing are about taking something from nature without the need for much transformation of the environment. By contrast, the act of transforming undomesticated spaces into a domesticated one is crucial in the making of a garden. In the words of one of my informants from Muntei village:

We are human (sirimanua) and do not simply take something (maalak) from the forest and eat it. We are thinking about how to open the forest, how to cut the big trees before we actually cut the trees, slash the shrubs, and clear grass and weeds. We imagine everything (anai kapatuatmai). When we make gardens, [we make] the future. The spirits in the forest and the animals do not practice ‘gardening’. We do not know. The spirits have their own livestock. Deer, wild boar are theirs. But they do not feed them with sago and coconut. We are not like animals. Chickens and pigs just wander around forest taking grass and leitik (worms). It is important for humans that we eat what we produce.

The importance of gardening is evident in the similarity between the terms used to describe its products. Sago palms, fruits trees, pigs, and chickens in the gardens are generally called purimanuaijat (livelihood), a noun related to murimanua (to live) and sirimanua (human beings). The products of cultivation activities in the gardens (purimanuaijat) are an extension of sirimanua. Hence, plants and animals in gardens are not only seen as a source of livelihood for the human beings who cultivate them, but as an extension of their persons. People value their gardens highly and the food they produce reflects the importance of gardening activities. As gardening generates value, people consider any food in the garden to have a higher value than any food that is simply extracted from non-domesticated zones.

Fish and shrimp from the rivers and coral reefs are a desirable and vital source of daily protein. Wild ferns or cassava leaves are occasionally gathered from nearby forests or gardens. However, small fish, shrimps or vegetables are considered inferior and thus only consumed in the domestic sphere, never displayed on public occasions or offered during a lifecycle ritual such as a marriage or funeral. The low status of these kinds of food is due to the absence of any transformation of space. Freshwater creatures are obtained in undomesticated spaces; whilst other inferior food such as sago grubs and leaves are not intensively cultivated and do not require the constant labour investment required for pig and chicken husbandry. Small mammals and various species of birds are casually hunted, especially during the fruit season. However, these animals are not served as part of a ritual meal.

Domesticated and undomesticated; male and female; raw and cooked

The most desirable source of protein is in two groups: hunted game and domestic animals. Wild pigs, four species of primates and deer are hunted game obtained from the forests (iba-t-leleu) while dugong and turtles are the most important sources of meat from the sea (iba-t-koat). Culturally, they are the most important game animals, hunted exclusively by men to mark the end of a religious ritual. Hunting as part of rituals is a daytime pursuit, undertaken collectively. However, these animals are also hunted on an occasional basis when people encounter them around the gardens. Opportunistic hunting is flexible and can be done whenever signs of animals are seen. As with ritual hunting, the yields of individual hunting must be shared with group members and participants. The value of hunted game does not lie in the quality of the meat, but in its symbolic worth (Schefold Citation1982: 75). The meat obtained from non-domesticated spaces is a gift provided by spirits and a sign that humans have established successful exchanges with the spirits. Socially, the shared meat (otcai) represents the equality of the group (uma), while the sharing activities display the success of the hunting and of the ritual, expressing the sense of solidarity and cohesiveness of the group. When an uma is split and divided, people articulate the event as the moment when they did not have enough game to be shared equally (Schefold Citation1982).

Pigs and chickens are the most common domestic animals and the most important sources of meat. They are available throughout the year, but people do not consume them frequently. The consumption of these animals is reserved mainly for communal ceremonies and, more recently, for large gatherings at church.Footnote7 These domestic animals are valuable because the entire cycle of production and consumption is laborious and associated with many taboos and cultural sanctions. The importance of pigs and chickens, however, goes beyond their meat. Pigs and chickens are the most important gifts offered to spirits in religious rituals. It is believed that pigs and chickens can transcend the perspectives of the spirits of humans and non-humans (Schefold Citation1973; Hammons Citation2010).

Pigs and chickens are the ultimate measure of a person’s productive activities and thereby their importance. People regard their domesticated animals as expressions of their creative energies, skills and knowledge, and capacity as social persons. A chicken or a piglet can be exchanged by an individual for valuable imported goods. In this capacity, domesticated animal can produce social prestige for an individual in intersubjective relationships. However, when pigs are slaughtered their meat must be consumed communally. Here, domesticated animals represent and embody the ultimate social significance of a person’s activities; they become the means of his or her integration into the group. Pigs integrate people into a contrastive totality during the ritual feast or a social exchange with other uma. While having as many pigs as possible becomes the ultimate goal of individual actions, sharing pork to enact the unity of the group is the ultimate goal of uma. Pigs are the embodiment of value, the ultimate object of people’s desire.

Domesticated animals also give a hint of gender relations although this is not rigid. Pigs and chickens are animals that normally belong to men. Men are responsible for controlling the pigs and chickens and they therefore claim ownership of them. Nurturing piglets, moving sows, catching feral pigs and slaughtering pigs for ritual and cooking their meat – these are all performed by men. There is no prohibition on women having pigs of their own or taking care of pigs. A wife or a sister or a daughter may contribute to feeding and taking care of the pigs or chickens. However, she will not jointly own the animals with her husband, siblings, or father.

The complementarity of domesticated and non-domesticated food is important in ritual contexts, as is the complementarity of foods that are associated respectively with male and female. Both domestic animals and hunted game are called ritual meat ((iba-t-punen); however, they are also distinguished as complementary. To obtain hunted game, humans must sacrifice their domestic animals and offer them to the spirits. In return, successful hunting will allow them to succeed in raising pigs and chickens. The role of gender is also complementary. Women prepare food that comes exclusively from the gardens (sago and taro) while men provide pork and chickens and hunted meat. Men slaughter, wash, distribute and cook meat while women prepare the sago and taro. However, it should be noted that certain undomesticated foods are absent from ritual meals. People do not eat raw food (kop simatak) in a communal ritual. Neither do they serve small fish, shrimps, small mammals, or vegetables, all of which are termed ‘women’s meat’ (iba-t-sinanalep). Thus, it would appear that meat is marked as associated with men in ritual contexts, even though in everyday meals ‘women’s meat’ is regularly eaten.

The Mentawai have an elaborate culinary code, applied especially in communal rituals (Schefold Citation1982). This code, Schefold argues, informs and structures ‘the good’ and ‘the bad’ values associated with the ritual process. The mediating function of food is, I argue, both more creative and dynamic. Shared pork or hunting for meat does not merely symbolise or represent social value in a static sense (good or bad); rather, it generates, moves and transforms social value. Food enables humans to enact changes in themselves and in the world. Thus, the prohibition on consuming sour food such as unripe fruits may perhaps be associated with the sharpness of a hunting weapon used in ritual hunting (Schefold Citation1982: 78). This means that eating uncooked food can be dangerous to the hunter. However, my interpretation of the attitude to raw food is that it is linked to not transforming space and not creating complex social relations. Raw foods are easily consumed individually in undomesticated spaces while cultivated, hunted game and domestic animals are processed and consumed collectively in social spaces and require complex human labour. Only cooked food is served in communal rituals – and to some extent also in daily meals eaten together in every household. The whole range of activities involved in transforming raw food from unsocialised spaces (forest, garden) into cooked food in the most socialised space (the longhouse, house) defines the value of food, both for the producer who produces it and the consumers who eat it.

Producing food and the quality of persons

Gardening is the main form of labour that provides sustenance. The importance of gardening is linked to the way the Mentawai define the socially perceptible qualities of themselves as human beings. They commonly identify themselves using phrases such as ‘kai, si mattawai siurep sagu’ (we, Mentawai, are sago cultivators) or ‘kai sipumone’ (we are forest cultivators). They proudly define themselves through such activities as being in the garden, extracting sago, harvesting fruit, and tending domestic animals. Any person or family who does a combination of gardening and pig keeping is referred to as mattawai siburuk (an old Mentawai). This term implies a degree of social prestige and recognition and does not necessarily refer to an older person or only to men. The younger generation who live in the settlement but spend much of their time at school and then work in government service offices, and others who invest their creative energy solely in cash-crop production, are not referred to as mattawai siburuk.

The phrase ‘old Mentawai’ is perhaps more accurately translated as ‘people who are living with old customs’, or ‘people who are practising old activities’, and has the figurative meaning of a ‘genuine Mentawai’. An ‘old Mentawai’ has special attributes, such as a strong body, skills, and the knowledge required for gardening and making food. The quality of the body is the most perceptible quality of an old Mentawai. Having a strong body (kelak tubu) is a common qualification for a good gardener. Kelak tubu is achieved through years of clearing forest, planting tubers and bananas, and grating sago starch. Indeed, almost all substantial Mentawai food production requires hard physical labour. Kelak tubu is a product of active and continual work in the garden. The term kelak tubu is also associated with having a healthy body (marot tubu). A person with a healthy body (simarot tubu) eats good food and is therefore rarely attacked by disease or sickness. For women in particular, this physical quality of strength, which is considered the result of activities related to gardening, is important. Women with a strong physique (badagok) are highly regarded. There is also an association between badagok and reproductive ability and quality.

An ‘old Mentawai’ also possesses special knowledge and creativity. Creating a new garden and raising pigs, for example, not only requires heavy physical labour, but also specific skills and knowledge in order to carry out rituals and communicate with the spirits. Gardening requires experience and the ability to know the quality of soil, the terrain, and to be able to be aware of the perspective of the spirits. The process of clearing a part of the forest requires knowledge and skills to enable one to cut down giant trees, time ritual offerings correctly and ask for the blessing of the spirit of the forest. The process of pig keeping, for instance, requires a series of rituals – on the day the piglets are separated and taken to a new place, when a pig hut is erected, and when a boar is trapped, caught, and killed for ritual purposes.

The perceptible qualities of a body, knowledge, and gardening skills are intertwined with the qualities of a person. A very highly regarded person (simaeru) is referred to as a person whose body is continuously moving (majolot tubbu). A majolot tubbu person (simajolot tubbu) is active, independent, and capable of making his or her own decisions. A simajolot tubbu is always doing productive things, either in the house or in gardens. Another term of approval is mamoile kabei, which means ‘having hands that are always doing something’. A simamoile kabei is one who acts with initiative rather than be directed and is always busy making something; they never return home from the gardens empty-handed. The Mentawai distinguish between the quality of mamoile kabei and that of mangamang (diligence). Mangamang is applied to a person who is willing to work or is hardworking. A diligent person (simangamang) is a good one. However, simangamang does not always entail the quality of doing something voluntarily as such a person can be working hard under supervision or when seen or watched another person. Such a person does not always have the initiative or the creativity encompassed by simajolot tubbu or simamoile kabei. Being able to carry out a productive act at one’s own volition is the definition of an admirable or praiseworthy person. Here, willingness to do productive things independently is the quality that defines the difference between a very good (simaeru sigalai tubu) and a good person (simaeru).

In everyday conversation, the positive quality of being a ‘very good person’ is expressed in terms that are related to gardening. Simajolot tubbu and simamoile kabei are referred as simategle: those who are always using their machete. They are also called simakbokbok, referring to those who always have wounds or a sore body after working hard in the garden. Furthermore, simajolot tubbu is also referred to as simasabaet: one who is always looking for a new place to cultivate. Social judgements about a person revolve around their ability as a food producer: ‘He is a good person (simaeru). He has a large garden.’ or ‘She is a prospective wife because she spends most of her time in the garden.’ By contrast, a ‘bad’ person is someone referred to as being takmei tubbu (a still body/inert) and with an inactive body (mabeili). Takmei tubbu persons (sitakmei) are perceived as always sitting (mutobbou), eating (mukom) and sleeping (merep), all of which are associated with passivity. Someone who is sitakmei tubbu prefers to stay in the house and does not go to the gardens to do something productive. They have a soft body (mamekmek tubu) because they do not work hard or use their body for productive purposes. A sitakmei tubbu is not only associated with physical inertia, but also with the deactivation of will. Being inactive involves a minimisation of social activity and will, a condition that often results in subordination to others. Moreover, being lazy is considered shameful as it connotes a constant dependence on others.

(Re)producing men and women

There are different types of gardens divided along gender lines. Sago gardens are for men and taro fields for women. The importance of food, however, in the (re)production of women and men is not limited to the cultivation of taro or sago. The categories of men and women are continually produced through food production over the course of a lifetime, both symbolically and concretely. It starts when a human is in the womb. The Mentawai say there is no specific gender differentiation in foetuses and they are commonly called suruket (those who are in protected places and who must be protected). Gender is only assigned when a baby is born, and referred to with gender-specific terms: a baby boy is called kolik, a baby girl is called jikjik.

When babies start to walk, their parents take them into the surrounding environment. Until the age of four or five, boys and girls may still sleep with their mothers, but from about this age, they look for their own sleeping place although some boys still sleep next to their fathers. After that they may be taken to nearby gardens and begin to understand their position in society. As a toddler, a boy is called situt amanda, a person who follows his father. The boy spends most of his time with his father and observes what he is doing. Sometimes, a father takes his boys to the garden. At the same age, a girl is called situt mamaknia, a person who follows her mother’s steps. Girls stay close to their mothers and spend most of the time observing and watching what women do.

Gender difference becomes explicit around 6 to10 years of age. At this time, girls are taken to taro gardens and on fishing trips, although they do not necessarily fish by themselves. Boys accompany their fathers to the gardens. Once the children are familiarised with the different activities of men and women, a ritual may be enacted to mark and distinguish these gender roles. In coastal villages, this initiation ritual is called eneget, which is usually part of a larger ritual. This is the first time boys and girls are given manai, a kind of ornament worn by all participants in a religious ritual. Manai signifies that the children are strong enough to fully participate in all stages of rituals. The most important feature of eneget is that the head of the ritual gives a speech and the boys are permitted to touch a bow and use the machete, and the girls touch a fishing net. This symbolic act pronounces them to be male and female subjects. A boy is expected to go to the gardens or to hunt, and to be a producer of domestic animals for ritual. A girl must be a good taro gardener, gatherer of freshwater animals and provider of daily meat (iba-t-sinanalep) such as worm, mussels, clams, small fish etc.

The eneget ritual creates the basic template for gender roles for the rest of their lives. Men tend to be gardeners and engage in activities around the forest garden. They go to the forest and garden with a bow (rou-rou) and machete (tegle). Clearing a space in the forest, cutting sago, tending and slaughtering pigs, and performing rituals are all male activities. Men lead all gardening projects and initiate the harvesting of fruit trees. Recently, they have increased their time managing cash crops. Women, in contrast, tend to be gatherers. They go to their taro gardens with fishing nets to obtain small fish, clams and shrimp, and to collect sago larvae and other grubs and worms in and around their gardens.

It should be noted that men and women are both associated with domesticated and undomesticated spaces. Men are associated with sago and domestic animals as well as hunting in undomesticated areas. While women are symbolically associated with the taro gardens and domestic sphere, their activities are not limited to this area. In fact, women’s productive activities extend beyond the binary of domestic-undomesticated space. They go to the margins of the forest to collect wild vegetables or firewood and paddle their canoes to mangrove forests for crabs and fish.

Feeding the family: food, self-sufficiency, and autonomous social actors

The Mentawai emphasise that all humans are equal, with an equal voice and equal rights. Each person is made up of the same elements: a body (tubbu), spirits (simagre), emanating powers (bajou), and a mind (patuat) (Loeb Citation1928; Schefold Citation1973; Hammons Citation2010). However, people are not politically equal. Women and young people have less of a voice and less decision making power than men. Young people usually follow the decisions taken by adults in the family. Unmarried girls’ decisions and activities are occasionally directed by adult females, while young men’s decisions are guided by male and female adults. In fact, the main locus of political equality is the family, with the adult men as representatives of the family.

The family (lalep) is defined as a man, his wife, and their unmarried sons and daughters living in the same house. The core relationship within the family, therefore, is a couple working together to assert their equal position within their uma and to produce offspring for the next generation. It is organised by a principle of mutual dependency and co-productive work, and through relations between men and women from different groups and relations between parents and their children. The family is the core of domestic production. It has a dual function. The formation and expansion of the family produces not only the family itself, but also the most important products of the family i.e. children and food, both collectively important for the uma. The temporal form and spatial relations of the process of social production in the family thus relate to two cyclical processes of transformation: the natural cycle and the social cycle. Naturally, the unity of men and women in the family initiates the process of natural production and reproduction – sexual intercourse, pregnancy, birth, parenting. Socially and economically, the lalep is the starting point for a married couple to initiate a relationship as a coherent productive unit. Only through the family can an adult engage in structured and productive work and acquire properties (a garden, a house) to sustain and maintain the family institution. In the family, adult men and women are producers of natural products (children) and social products (mainly food) to transform the former into full-fledged social beings.

The connection between the social function of the family and the development of a social person lies in adult men and women’s abilities as producers. Having several gardens with food plants and animals is a fundamental means for adults to retain their independence and to raise their children as capable social actors. In turn, the children will eventually take over the position of their parents through their own marriages and the institution of the family, becoming social actors in the process. To be a full and proper social actor, a person must experience a series of social stages and a succession of physical and cognitive developments over time through various social processes within the family, and they must have a family of their own.

The gradual process of the development of the family as a cohesive social unit generates social status for adults. Parenthood is the source of social status. Only when they have their children and grandchildren do the men and women acquire status as fully respected social actors. This normally occurs around the age of 40. A man who has grown-up children and is about to be a grandfather can be called sikebbukat (the older one). The term is derived from the word kebbuk (older brother) and has the figurative meaning ‘the wise one’. The female partner of a sikebbukat can be called sikalabai (the adult woman). The term is derived from the word kalabai which has the figurative meaning ‘the experienced one’. The terms sikebbukat and sikalabai are reserved for adult men and women who have attained the social age and family status of a parent with grown-up children, at which stage they are ‘in the know’ and able to perform with the necessary level of mastery and influence, especially in terms of the socialisation of their children.

The status of sikebbukat and sikalabai connotes two domains at once: food sufficiency and status differentiation. Sikebukkat and sikalabai are a married couple who have children, can run a household, cultivate, possess food and cash crops, and feed their co-resident descendants. Having children and transforming them into social beings requires experience in producing food and maintaining reciprocal relations with kin, and to some extent, establishing a social exchange with members of other clans. Sikebbukat and sikalabai are persons who can make good decisions for themselves. Their independence means they can express themselves freely and are not constrained by other members of the uma. They are expected to play an important part in the affairs of the group, to be a voice of moral authority, and to ensure their children may also reach the same level one day. They have personal qualities that are associated with being independent, developed and manifested in the specialised performance of a variety of ritual actions, leadership, gardening, and other respected behaviours. All these experiences teach a man or a woman to assert their decision making and voice his or her perspective (patuat) in relation to others and to attain a sense of completeness, marking a man or a woman as a full social being and an independent social actor.

Exchanging food, creating intersubjective relations

The importance of food and gardens in the production of the social actor is not, however, only located in the family sphere, but also in interpersonal relations. Sago palms and fruit trees are important not only as comestibles, but also as living property that can be exchanged and circulated between persons across uma to develop intersubjective relationships. The importance of food resources and reserves is linked to the basic principle of intersubjective relationships: paroman.Footnote8 The term paroman is used to describe both the act of mutual social relations and the items involved in these relations. The relations are paroman when all the parties involved feel that they are fair: for example, in a mundane relationship, a coconut tree may be exchanged for a hen and chicks or a mosquito net; time spent clearing a garden may be exchanged for some uncooked pork or packets of cigarettes. Paroman always involves valuable objects, mostly in the form of food resources from the gardens (sago, pigs, fruit trees), together with commonly used items such as machetes and mosquito nets and labour. Whether a relationship is paroman or not depends on the activity involved, the value of the items exchanged, both parties’ subjective opinions, and the history of the parties’ past relations.

To achieve paroman, all persons and groups require a degree of knowing each other in a particular context. Thus, a social actor must be able to assert their intention and affect the other person’s attitude, perspective, or orientation. A successful paroman exchange happens when there is convergence in the thinking and perspectives of two parties and they agree upon the objects involved in the exchange (isese). The term isese means that the relationship involves both proper actions and proper objects of exchange; and that the parties accept that they will act according to the desires of the other person with whom they have come to a ‘meeting of minds’. People in fact say a successful paroman exchange happens when two social persons ‘have the same mind’ (makerek patuat) or when the intention and the will of two persons’ match each other (tuguruk patuat).

A person with many pigs or gardens has a greater chance of a successful paroman exchange. Possessing garden products generates social status and results in the power to influence the mind (patuat) of others and expand a person’s space and time. A man who owns many pigs and fruit trees can acquire social prestige and authority. He can expand his social influence when he contributes his food during clan affairs. People say that those with large gardens and many pigs are both wealthy (makayo) and ‘have a swagger’ (magege). The ones with swagger are not afraid to initiate social relations and make mistakes as they are always ready for social exchange because they have enough sago, taro, and pigs to mediate the possibilities. In contrast, persons without sago or fruit trees usually avoid social relations.

Garden products and other food resources are as important as the act of persuasion in any social exchanges. The number and quality of sago palms and pigs are subjects of the intertwined processes of remembering (repdeman) and promising (janjiake) in past and future intersubjective relationships. Possessing sago or pigs not only enables people to strengthen past paroman, but also to stimulate new ones. In the case of a new relationship or the re-establishment of an old paroman, each party will enthusiastically recall the sago, fruit trees, or machetes of their predecessors in past social exchanges and promise their own possessions to ensure their next exchange. People frequently remember special events or specific social relations in terms of the food resources involved in the transaction. Men speak of remembering their allies as regular donors of certain kinds of gifts or as partners of paroman exchanges. By remembering and promising food resources involved in social exchanges, people are obliged, in turn, to produce their own food for future exchanges and prevent sago, durian trees, and taro gardens from disappearing.

The Mentawai often say that they must have an abundant garden to strengthen existing relationships and anticipate social events. Adult men often talk about when their son might get married. They must be ready to hand over sago, pigs, and other valuable plants in the garden to the bride’s family. They also tell me that they must be ready for potential conflict with others or, if their children make a mistake, to pay compensation. Hence, almost all people have more than one plot of sago, taro, or orchard. These gardens are kept even though some of them may not be exploited. Despite having more than enough to sustain their needs, they are always making new gardens and cultivating new crops. This preparedness for social exchange with others in the foreseeable future is termed anai kakabei (‘we have it in our hand’).

Producing garden products and having food resources symbolise a person’s capacity and potential to assert political equality in the web of intersubjective relationships. Thus, garden products have an ‘invisible potency’ (Munn Citation1986: 53) because they can become many other things in the future. Food resources allow an individual’s identity to be distributed or expanded, as individual property is constantly circulated throughout the exchange network. Furthermore, exchanging sago palms or langsat trees constructs and maintains inter-subjective social relations, constructing and renewing social relations on an ad hoc basis. By exchanging these high value items, people create the web of social relationships that defines and binds them as a community.

Producing food, producing ‘others’

Producing food and maintaining gardens is not only important for preserving familial or intersubjective relationships, but also crucial to inter-ethnic relations. The Mentawai have long been in contact with non-Mentawai, whom they call sareu (‘those from afar’).Footnote9 Sareu is a broad category and can refer to a Nias shopkeeper, an Australian surfer, or a Dutch anthropologist. The term sareu can also, however, be used in a specific fashion to refer to the MinangkabauFootnote10.

The Mentawai see sareu primarily in terms of the kind of food they produce and the substances and practices that constitute and form their bodies. Sareu, in the sense that the term is used to refer to Minangkabau, are seen as rice producers and traders. They are people who keep cows, goats, and buffaloes as livestock. The Mentawai believe that the way people practice cultivation and carry out labour corresponds to the perceptible quality of their bodies. They quickly specify that sareu are dark-skinned (makotkot tubu) and have a soft physique (mamekmek tubu), the result of working in the coastal zone as fishermen or doing constant work to protect their paddy fields from pests. Both occupations require the sareu to work under the sun. The soft physique of sareu is associated with a lack of physical movement, for e.g. Minangkabau traders are seen sitting all day long in their shop and not partaking in intensive physical exercise.

Sago cultivation and pig keeping are the critical activities that define a Mentawai in contrast to a sareu. The bodies of the Mentawai are bodies that produce and digest the main products of gardening, sago and pork (see Delfi Citation2012). Aman Joni, a young father (aged 28) from Muntei village, once told me when I asked him what the main difference is between the Mentawai and the people from mainland:

[…] we are sago cultivators and pig producers. From birth to death, in health and in sickness, we need both of them. When we are silainge (teenagers), we learn everything about sago gardening and pig keeping. Our strong powers are constantly being used to cut sago palm, grate the pith, and bring pigs from the hut. Our bodies are developed by producing sago, pigs and eating pork. Our bodies are always asking for this food.

The way in which the term sareu is used to refer to the Minangkabau explains why the Mentawai feel themselves to have more affinity with the Batak and Nias people. These peoples have been a part of Mentawai social life for as long as the Minangkabau. They also occupy a social niche as as mediators in the relationship between the Mentawai and the state administration and regional economy. To a certain extent, they are thought to be as ‘cunning’ as the Minangkabau; however, the Mentawai insist that the Batak and Nias people are not entirely sareu. In their homeland, both are seen as pork producers and eaters. By producing pork, the Batak and Nias sareu share bodily activities and substance with the Mentawai. They are faraway people, but their bodies are not.

Producing non-Mentawai food is regarded by the Mentawai as being part of non-Mentawai personhood. People in Mentawai identify themselves as people from the forest, gardeners, and pig producers, while sareu are rice growers and traders and are intolerant of both pigs and pork.Footnote11 Food not only qualifies social relations between the Mentawai and sareu, but also brings about the differences between them. Forest gardening is the activity that identifies the Mentawai as distinct, while pigs and pork are the substances that distinguish their way of life. Identification as forest gardeners/rice cultivators, or, to use the term by Harris (Citation1985), ‘pig lovers/haters’, is an important element in constructing and manipulating ties with sareu. Thus sareu are identified as ‘other’, something that is born out of an acknowledged difference and contrasting values with respect to forest gardening, pig husbandry and pork consumption.

Conclusion: food, action, valued persons and sociality

My ethnographic description and analysis suggest that the importance of food for the Mentawai is not only symbolic or nutritional. The importance of food lies equally in its ability to mediate human actions. To be human, people must eat and cultivate food. Gardening requires energy that is produced by the consumption of food, which is, in turn, acquired by converting natural spaces and products into consumables through a set of social activities and transformative processes. Such an evolvement of natural products through cultivation and the processing of food resources into a meal defines a person’s humanity. Only humans can make this transformation.

The Mentawai share ideas and practices relating to the use of food as an active substance in the process of personhood construction with other societies in Southeast Asia and beyond. My ethnographic materials clearly illustrate that food is an ingested substance regarded as being produced primarily through human activities. The Mentawai barely touch upon the substantive qualities of food and food properties when they construct their personhood. Size, colour, shape, and the amount of food are certainly important, but to them it is the activities that produce a variety of food resources in the garden that bestow value, prestige, and personhood. How they value working in the gardens resembles how many other societies across the world do this (Janowski Citation2007a; Munn Citation1986; Fajans Citation1997; Tammisto Citation2018).

Producing food enables humans to develop themselves, thus constituting their bodies and identities (Fajans Citation1988; Mintz Citation1994; Oosterhout Citation2007). For the Mentawai, producing food defines the socially perceptible qualities of a person and is inseparable from the qualification of ‘person’. It also produces gender differentiation and is fundamental to the reproduction of family. Gardening is, furthermore, the means whereby intersubjective relations between individuals, between the individual and the group (uma), and between groups are created. Producing food is crucial for the process of self-identification and for construction of the ‘other’ that negatively defines the self. The importance of food in the production of self and the others (including the spirits and animal) in Mentawai culture evokes the way food mediates social relations between individuals, between an individual and a social group, between social groups (Young Citation1971; Meigs Citation1984; Fajans Citation1993; Janowski Citation2007a; Citation2007b), and between humans and more-than-human entities (Ingold Citation2000; Chao Citation2021).

The range of social activities in which the Mentawai engage daily to produce food is ultimately aimed at turning an individual into an independent, autonomous, and self-sufficient social actor. Hence, producing food is the concretisation of the value of human actions and the epitome of value in the context of the Mentawai sociality. Without food and gardens, an adult person or family or uma is negatively valued. With plenty of food and gardens, they are positively valued. Activities such as planting, tending animals, cooking, and especially gardening, are highly valued as they give a person sufficient food not only to nourish their own body but to form the basis of social actions within a social matrix where a person develops his or her sociality. Autonomy and equality are two central values for the Mentawai personhood since they give a person, as a social actor, political equality with other social actors. We can clearly see the parallel between the production of food, the production of persons, the reproduction of Mentawai social institutions (lalep, uma), as well as the links between them. Food is neither a mere symbol of nurturing nor a basic need for physical development, but a transformative agent in the construction of valued persons and social values.

Producing food is not only the production of materials that satisfy human needs as it is also part of the larger process of human and non-human production. Producing food involves a web of relations in which humans and non-humans alike take part in the process of becoming and where the capacity of humans to imagine, to plan and to reflect their actions is realised and recognised. My ethnographic sketch illustrates Ingold’s (Citation2011: 8) concept of sociality, in the context of which any intended human activities should be understood as being about ‘participating in the world’s transformation of itself’. Producing food is an arena where the Mentawai and non-Mentawai subjects (forest, sago gardens, hunted game, Minangkabau people, etc.) are continually and simultaneously co-produced and always in the process of ‘becoming’ (Ingold Citation2011). My ethnographic materials show that the Mentawai personhood and Mentawai social values are produced through human imagination, power and agency; they transform their physical environment and develop relations with non-human entities in order to establish their sociality. At the same time, the physical environment (forest), the materiality of more-than human entities (the spirit of the water for instance), also plays an important role in the continual process of the individual becoming a social person and the Mentawai becoming a society. Food production is a social landscape where the dialectical process of social value and sociality is produced. This is, I argue, the main reason why food is good to produce and must be continually produced. Food is a constitutive agent of human sociality and the fundamental material for the construction of sociality and social values.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Gerard Persoon, Tessa Minter, Monica Janowski and other anonymous reviewers for making valuable suggestions for the article. Monica Janowski also improved the text overall, which was copy-edited by Andy Fuller and proofread by Syahirah Rasheed.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Darmanto

Darmanto is a research fellow at the Oriental Institute, Czech Academy of Sciences, Prague. He was awarded his PhD (2020) by the Institute of Cultural Anthropology and Development Sociology, Leiden University. His undergraduate thesis won the Man and Biosphere (MaB) Award for young researchers and environmentalists and he later worked at UNESCO Jakarta Office’s Siberut Biosphere Project (2006–2011). During his years in Siberut, he established Perkumpulan Siberut Hijau (PASIH), a Siberut-based environmental NGO, and was its coordinator from 2006 to 2008. It also resulted in the publication of Berebut hutan Siberut: Orang Mentawai, kekuasaan dan politik ekologi (Disputes on the Siberut forest: the Mentawai, power and ecology politics; KPG, 2012). He was also a recipient of the Australian Award Scholarship (AAS) and the Louwes Fund for Research on Water and Food (Leiden University). His research interests include the human dimensions of environmental transformation and particularly, the multidisciplinary study of food, political ecology of nature conservation, indigeneity, and critical development. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 The term Mentawai is a collective term referring to all people who speak the Mentawai language, share an eponymous ancestor once living in a Simatalu village in the northwest of Siberut, and have a claim on land in the Mentawai Archipelago. I agree with Reeves’ argument (Citation1999) that the term ‘Mentawai’ or ‘Mentawaians’ has been constructed and constituted by colonial discourse and post-colonial development rhetoric. However, I reject his suggestion that we abolish the usage of the term, and his idea that an anthropologist is wrong for making generalisations about the Mentawai after working with people at a particular site.

2 Persoon et al. (Citation2002) have provided a major bibliography relating to the Mentawai Islands and other islands off the west coast of Sumatra.

3 The term is a verb derived from two words: the noun mone (lit. ‘an area of cultivation’) and the prefix mu meaning ‘doing something’ or ‘having something’.

4 For example, fishing with a hook around coral reef is called pangabli. Gathering small fish, crustaceans, and frogs in the small stream with a hand net in daylight is termed paligagra. Gathering fish at night with the help of a torch or lamp is called pangisou. Hunting animals with arrows or spears is called murourou. Casting a seine net for turtles in the sea is termed mujarik or muiba. While there is a specific term for certain ways of obtaining food, mumone is mostly referred as the way they produce food.

5 It should be noted, however, that these dualities are analytical categories as the boundary of each zone is not so neatly distinguished.

6 The blessing from the guardian of the forest or the sea is an important consideration in terms of whether the hunting expedition is a success or a failure (Schefold Citation1973; Citation1980). Hammons (Citation2010) also indicates that a successful ritual hunting is a returned gift from the spirits of the forest or the spirits of the ancestors in the context of a relationship of balanced reciprocity. However, the relationship between the blessing and the gift is always unpredictable.

7 The research area under study comprises predominantly Christians of various denominations and a small group of Muslims. During Christian celebrations (e.g. Easter or Christmas), the adherents would buy pigs collectively, slaughter, and divide the meat for individual buyers. For Muslims, although pork is prohibited some Mentawai Muslims, especially of the older generation, still practise traditional rituals in the form of sacrificing pigs and eating pork (Delfi Citation2012).

8 A paroman is a relationship involving different persons who normally have no kinship relations. It is a local variant of Marshall Sahlins’s concept (Citation1972: 19) of balanced reciprocity. In paroman exchange, a person does not necessarily immediately return the gift (items or labour) involved in the social relationship. However, exchanging sago or helping others in house construction generates a sense of obligation, which is paid off in the immediate future. For a discussion of paroman and other modality of exchanges, see Schefold (Citation1980) and Hammons (Citation2010), who provide a fuller discussion, especially in the context of ritual.

9 The term consists of sa (a prefix for a collective subject) and areu (afar), figuratively meaning people who come from other places and have no genealogical, land, or language relations with certain uma in the Mentawai archipelago.

10 The use of sareu specifically for Minangkabau people is part of a cultural and political repertoire in an asymmetrical and hierarchal ethnic relation. The Minangkabau are seen negatively as a coloniser (Eindhoven Citation2002: 364) who marginalise the Mentawai, taking advantage of the latter’s rich resources and returning nothing to the indigenous population.

11 The binary identification of the sareu-Mentawai is popularly enmeshed in a Mentawai story of two ancestral brothers, who were the progenitors of the western (white) people, the earlier mentioned sareu and the Mentawai. Laurens Bakker’s thesis (Citation1999: appendix) provides a full account of a version of the myth.

References

- Bakker, L. 1999. Tiele! Turis! The social and ethnic impact of tourism in Siberut, Mentawai. MA thesis, Leiden University.

- Barker, G. and Janowski, M. 2011. Why cultivate? Anthropological and archaeological approaches to foraging-farming transitions in Southeast Asia. In G. Barker and M. Janowski (eds), Why cultivate? Anthropological and archaeological approaches to foraging–farming transitions in Southeast Asia. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, pp. 1–16.

- Blust, R. 1976. Austronesian culture history: some linguistic references and their relations to the archaeological record. World Archaeology 8 (1): 19–43.

- Bellwood, P. 1996. The origins and spread of agriculture in the Indo-Pacific region: gradualism and diffusion or revolution and colonization? In D.R Harris (ed.), The origins and spread of agriculture and pastoralism in Eurasia. London: UCL Press, pp. 465–498.

- Bellwood, P. 2004. First farmers: the origins of agricultural societies. Oxford: Blackwell.

- BPS Mentawai. 2017. Kabupaten kepulauan Mentawai dalam angka [Mentawai archipelago district in numbers]. Tuapeijat: Badan Pusat Statistik Kabupaten Kepulauan Mentawai.

- Carsten, J. 1995. The substance of kinship and the heat of the hearth: feeding, person-hood and relatedness among Malays of Pulau Langkawi. American Ethnologist 22 (2): 223–241.

- Chao, S. 2021. Eating and being eaten: the meanings of hunger among Marind. Medical Anthropology 40 (7): 682–697.

- Counihan, C.M. and Esterik, Penny van. 2012. Introduction. In Carole M. Counihan and Penny van Esterik (eds), Food and culture: a reader. 3rd edn. New York: Routledge.

- Coursey, D.G. 1978. Some ideological considerations relating to tropical root crop production. In E.K. Fisk (ed.), The adaptation of traditional agriculture: socio-economic problems of urbanization. Development Studies Centre Monograph. 11. Canberra: Australian National University, pp. 131–141.

- Darmanto. 2016. Maintaining fluidity, demanding clarity: the dynamics of customary land relations among indigenous people of Siberut Island, West Sumatra. MA thesis, Department of Asian Studies, Murdoch University, Australia.

- Darmanto. 2020. Good to produce, good to share: food, hunger and social value in a contemporary Mentawaian society. PhD thesis, Leiden University.

- Darmanto. 2022. Ambiguous rice and the taste of modernity on Siberut Island, West Sumatra. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies.

- Delfi, Maskota. 2012. Sipuisilam dalam selimut Arat Sabulungan: penganut Islam di Siberut [Sipuislam and Arat Sabulungan: Muslim community in Siberut island]. Jurnal Al-Ulum 12 (1): 1–34.

- Douglas, M. 1984. Standard social uses of food: Introduction. In M. Douglas (ed.), Food in the social order: studies of food and festivities in three American communities. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Eindhoven, M. 2019. Products and producers of social and political change: Elite activism and politicking in the Mentawai Archipelago, Indonesia. PhD thesis, Leiden University.

- Eindhoven, M. 2002. Translation and authenticity in Mentawaian activism. Indonesia and the Malay World 30 (88): 357–367.

- Ellen, R. 1999. Forest knowledge, forest transformation: political contingency, historical ecology and the renegotiation of nature in Central Seram. In T.M Li (ed.), Transforming the Indonesian uplands. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers, pp. 131–156.

- Ellen, R. 2012. Studies of swidden agriculture in Southeast Asia since 1960: an overview and commentary on recent research and syntheses. Asia Pacific World 3 (1): 18–38.

- Fajans, J. 1988. The transformative value of food: a review essay. Food and Foodways 3: 143–166.

- Fajans, J. 1993. The alimentary structures of kinship: food and exchange among the Baining of Papua New Guinea. In Jane Fajans (ed.), Exchanging products, producing exchange. Sydney: University of Sydney.

- Fajans, J. 1997. They make themselves: work and play among the Baining of Papua New Guinea. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Flach, M. 1977. Yield potential of the sagopalm and its realisation. In K. Tan (ed.), Sago-76: Papers of the First International Sago Symposium: the equatorial swamp as a natural resource, 5–7 July 1976, Kuching, Malaysia. Kuala Lumpur: Kemajuan Kanji, pp. 157–77.

- Graeber, D. 2001. Toward an anthropological theory of value: the false coin of our own dreams. New York: Palgrave-Macmillan.

- Graeber, D. 2013. It is value that brings universes into being. HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 3 (2): 219–43.

- Hammons, C. 2010. Sakaliou: reciprocity, mimesis and the cultural economy of tradition. PhD thesis, University of Southern California.

- Hanks, L.M. 1972. Rice and man: agricultural ecology in Southeast Asia. Chicago: Aldine Atherton.

- Harris, M. 1985. Good to eat: riddles of food and culture. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Harris, M. and Ross, E.B. (eds). 1987. Food and evolution: toward a theory of human food habits. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Ingold, T. 1996. Key debates in anthropology. London: Routledge.

- Ingold, T. 2000. The perception of the environment: essays on livelihood, dwelling and skill. London: Routledge.

- Ingold, T. 2011. Being alive: essays on movement, knowledge and description. London: Routledge.

- Janowski, M. 2007a. Introduction. Feeding the right food: the flow of life and the construction of kinship in Southeast Asia. In M. Janowski and F. Kerlogue (eds), Kinship and food in South East Asia. Copenhagen: NIAS Press, pp.1–23.

- Janowski, M. 2007b. Being ‘big’, being ‘good’: feeding, kinship, potency, and status among the Kelabit of Sarawak. In M. Janowski and F. Kerlogue (eds), Kinship and food in South East Asia. Copenhagen: NIAS Press, pp. 93–120.

- Kahn, M. 1986. Always hungry, never greedy: food and the expression of gender in a Melanesian society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lévi-Strauss, C. 1966. The culinary triangle. Partisan Review 33 (4): 586–595.

- Lévi-Strauss, C. 1970. The raw and the cooked: introduction to a science of mythology. London: Jonathan Cape.

- Loeb, E.M. 1928. Mentawei social organization. American Anthropologist 30 (3): 408–433.

- Lounela, A.K. 2021. ‘Shifting valuations of sociality and the riverine environment in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia,’ Anthropological Forum 31 (1): 34–48.

- Meigs, A.S. 1984. Food, sex, and pollution: a New Guinea religion. New Brunswick NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Mertz, Ole, Padoch, C., Fox, J., Cramb, R.A., Leisz, S.J., Nguyen, T.L. and Tran, D.V. 2009. Swidden change in Southeast Asia: understanding causes and consequences. Human Ecology 37 (3): 259–264.

- Mintz, S. 1985. Sweetness and power: the place of sugar in modern history. New York: Penguin.

- Mintz, S. 1994. Eating and being: what food means. In Barbara Harriss-White and R. Hoffenberg (eds), Food: multidisciplinary perspectives. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Mintz, S. and Du Bois, C. 2002. The anthropology of food and eating. Annual Review of Anthropology 31 (1): 99–119.

- Munn, N. 1986. The fame of gawa: a symbolic study of value transformation in a Massim (Papua New Guinea) society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Nooy-Palm, H. 1966. The culture of the Pagai Islands and Sipora, Mentawei. Tropical Man 1: 152–241.

- Oosterhout, D. van. 2007. Constructing bodies, constructing identities: nurture and kinship ties in a Papuan society. In M. Janowski and F. Kerlogue (eds), Food and kinship in South East Asia. Copenhagen: NIAS Press.

- Persoon, G. 1992. From sago to rice: changes in cultivation in Siberut. In E. Croll, and D. Parkin (eds), Bush base, forest farm: culture, environment and development. London: Routledge, pp. 187–199.

- Persoon, G. 1994. Vluchten of veranderen: processen van verandering en ontwikkeling bij tribale groepen in Indonesië [Fleeing or changing: processes of change and development in tribal groups in Indonesia]. PhD thesis, Leiden University.

- Persoon, G. 2001. The management of wild and domesticated forest resources on Siberut, West Sumatra. Antropologi Indonesia 64 (1): 68–83.

- Persoon, G. 2002 Defining wildness and wilderness: Minangkabau images and actions on Siberut (West Sumatra). In G. Benjamin and C. Chou (eds), Tribal communities in the Malay world: historical, cultural and social perspectives. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

- Persoon, G. and Iongh, H.H. de. 2004. Pigs across ethnic boundaries. In J. Knight (ed.), Wildlife in Asia: cultural perspectives. London: Routledge Curzon.

- Persoon, G., Schefold, R., Roos, E. de and Marschall, W. 2002. Bibliography on the island off the west coast of Sumatra (1984–2002). Indonesia and the Malay World 30 (88): 368–378.

- Poser, A. von. 2013. Foodways and empathy: relatedness in a Ramu river society, Papua New Guinea. New York: Berghahn.

- Reeves, G. 1999. History and ‘Mentawai’: colonialism, scholarship and identity in the Rereiket, West Indonesia. Australian Journal of Anthropology 10 (1): 34–55.

- Reeves, G. 2001. The Suku: profiles and interrelations. Mentawai Culture & Societyt www.mentawai.org. <https://www.mentawai.org/anthropology-92-93/the-suku-profiles-and-interrelations/>. Accessed 15 July 2015.

- Sahlins, M. 1972. Stone age economics. Chicago: Aldine Press, pp.16 –19.

- Schefold, R. 1973. Religious conceptions on Siberut, Mentawai. Sumatra Research Bulletin 2 (2): 12–24.