ABSTRACT

In this article, the focus is on a theoretical discussion about how to analyse masculinities and power in historical research based on imagery and visual sources from a material-discursive point of departure. The argument is that analysing photographs in sport and the material-discursive representation of men/masculinities could contribute to a broader understanding of men’s hegemony. The article adds to the field of visual literacy and connects research on visual materials, sports history and critical gender studies. The past of Swedish ice hockey constitutes the case, while the understanding of men/masculinities departs from research by Jeff Hearn, Raewyn Connell and other scholars within the critical studies on men and masculinities field. Using four specific photographs from the Swedish magazine Hockey, the analysis exemplifies how their materiality and discursivity relate to a broader cultural context of the hegemony of men and masculinities. For example, cultural dominance strategies, visual techniques that ‘activate’ a photographed (or objectified) male subject and entitlement are discussed, and how these include discursive and material meanings of masculinity, status, and domination and how such embodiments interconnect with a contextual configuration of the dominant hegemony of men.

Introduction: the popularity, potency and problem with photographed sports and men

In the seminal book Ways of Seeing, Berger (Citation1972) states that the social presence of women and men is portrayed differently. Conventionally, portraits of women include ‘attractiveness’, while portrayed men exude the embodiment of power or ‘action’. What Berger (Citation1972) points to is that the interpretation of embodiment is a gendered organising principle. For example, men’s relationships with their bodies are typically embodiments of masculinity (which are often associated with power). However, this does not mean that women are denied the potential of power, or that masculinity traits cannot be enacted differently in different situations (Connell Citation2005). When it comes to embodying and portraying gender, sport is one of the most influential arenas in many cultures. Here, for instance, men and boys discover and develop, whether in school or competitive forms, their ‘relationship’ and adaptiveness to certain ideal masculinities.

Some sports have a particular potential to portray influential ideals of masculinity and men (Kidd Citation1987). In one of her initial works, Connell (Citation1983, 18) writes about sport and argues that it teaches boys: ‘Force, meaning the irresistible occupation of space; skill, meaning the ability to operate on space or the objects in it (including other bodies)’. Taken together, the embodiment of force and skill constitutes the individual’s power in a sporting context, including a capacity to reach beyond that context. This echoes an argument developed by Young (, 146) in ‘Throwing Like a Girl: A Phenomenology of Feminine Body Comportment Motility and Spatiality’, in which she combines the work of Merleau-Ponty and de Beauvoir to describe the feminine movement as inhibited intentionality: ‘Typically, the feminine body underuses its real capacity, both as the potentiality of its physical size and strength and as the real skills and coordination which are available to it.’

The occupation of and operation in spaces thus link to gendered power, which according to Connell (Citation1983) should be interpreted as something productive and include dimensions of competition and pleasure, force and skill. Being able to carry out sporting actions with your body means that the body occupies a particular space, which in some sports is conditioned or limited by opponents’ endeavours to occupy the same area. How coaches and others interpret how well an athlete embodies this skill and force can either be understood in terms of social prestige (Berger Citation1972), or of becoming or portraying a gender or masculinity (Connell Citation1983). In other words, power and gender are relationally and socially constructed (between men and women/other men, or between masculinities and femininities/other masculinities) and are not essentially and exclusively anchored in men’s and women’s bodies (Young). I will return to the relationship between men and masculinities, or what Hearn (Citation2014) refers to as the material(-)discursive, later in the article.

One way of documenting, and also of reproducing, ideas of power, force and skill is through photography. A photograph can objectify but also activate ideals of how, for instance, masculinity skills and forces could or should be embodied. However, this way of seeing depends on the interpreter’s gaze (Edwards and Hart Citation2004). To capture this doubleness, the concept of ‘hegemonic masculinity’, as developed by Connell and colleagues, has been extensively used in studies of how sports are illustrated and presented in the media, with results revealing how men/masculinities dominate the media space (visually, temporally, etc.) and how women/femininities are relegated to subordinate roles (Smith Citation2014; Messner, Dunbar, and Hunt Citation2000). Men’s media exposure is sometimes explained by the broader interest in men’s sports, although at the same time it can be regarded as creating more popularity, which exemplifies how hegemonic power can help stabilise cultural conditions.

‘Hegemonic’ derives from the term ‘hegemony’, which figures in the Marxist-Gramscian thought tradition. By drawing attention to men as a social category constructed by a gender system, yet simultaneously as (dominant) individual subjects, Hearn (Citation2004) makes a point of using the term ‘hegemony of men’ instead of ‘hegemonic masculinity’. One key point in Gramsci’s analysis is that societal dominance can be maintained through cultural beliefs and strategies (and not necessarily through weaponised force), including ‘spontaneous’ consent with state coercive power if need be (Gramsci Citation2000, 306–7). That is, cultural conventions about how (sports) people are portrayed in the media influence and are influenced by more general perceptions of men/masculinities, women/femininities and reveal beliefs that can affect (and in turn are affected by) societal spontaneity and coerciveness. In other words, our interpretation of and gaze on embodiments in sporting are conditioned and permeated by learned cultural beliefs and perceptions. Alluding to Berger (Citation1972), seeing in this way could even precede words. According to hegemony theorists, these cultural beliefs always have the potential to reproduce the current power order in a society. Pointing to the importance of sport and gender, Connell (Citation2005, 54) writes that ‘ … men’s greater sporting prowess has become a theme of backlash against feminism. It serves as symbolic proof of men’s superiority and right to rule’.

An example of how sport and men/masculinities constitute cultural importance is the photographing of victory, mastery of force and skill. Every cultural context has photographs depicting this. In Swedish ice hockey, which is used as the cultural case here, Peter ‘Foppa’ Forsberg’s penalty goal in the 1994 Olympic ice hockey final between Canada and Sweden exemplifies this. Penalties determined the outcome, and in the last round, the Swedish player scored an unusual penalty goal, where the goalkeeper misjudged the situation and Forsberg shot the puck into the net with his hockey stick in one (back)hand (Peter Forsberg Lillehammer −94 avgörande straff+interwiev – YouTube). Illustrating the goal’s symbolic and cultural value, the replication of the penalty afterwards became a ‘Foppa’ hallmark and a goal that also inspired players to try the same penalty trick. On the one hand, this action illustrates how a decisive sporting moment can turn an athlete into an immortal hero, yet on the other shows how visual documentation, as a cultural artefact of national and cultural importance, can become a fostering act or, to use Peter Burke’s (Citation2014, 145) words, ‘historical agents’. In early 2022, the Swedish NHL player Elias Pettersson tried to mimic Foppa’s penalty, but it was actually Kent ‘Mr Magic’ Nilsson who slammed it into the net first when Sweden played against the U.S.A. in the 1989 World Hockey Championships (yosoo, Citation2023; Teus Citation2006).

Thus, photographs and other visual images are powerful sources of human communication that in turn intersect with materialities and discourses of knowledge and power (Edwards and Hart Citation2004). Not all photographs qualify for such status, although in more general terms, and when it comes to social media, Western culture can be said to be saturated with visual and photographic messages – in advertising, promotions, entertainment narratives and so on. Thus, photographs constitute a rich source of data for historians, even though their use also has pitfalls (Burke Citation2014; Huggins and O’mahony Citation2011). With their ability to depict, document and ‘immortalise’ decisive events and actions, photographs contain facts and norms or what can be described as informative and normative dimensions, a characteristic that potentially loads photographs with cultural relevance and social significance. As illustrated above, some photographs may even have an iconic function that contributes to national pride and cultural identity, thus ‘expanding’ their meaning both temporally and symbolically. Some scholars describe the focus on the social and representational meanings of imagery in more economic terms, such as visual currency or the visual economy of images (Poole Citation1997).

With inspiration from Critical Studies on Men and Masculinities (CSMM), the focus of this article is a theoretical discussion about how to understand sporting photography. The historical case builds on four photographs collected from the Swedish magazine Hockey.

Photography in (sport) history research

The capacities of photographs have been studied in several ways (Berger Citation1972; Dodge Citation2006; Kinsey Citation2011; Lisle Citation2011). As a photograph ‘speaks’ to the viewer in an immediate way (Berger Citation1972), its effectiveness as a propaganda and advertising tool has often been explored. Not surprisingly, photographs of objects advertising cars are often (strategically) associated with power, aggression and virility, symbolised by names like ‘Jaguar’ and permeated with ideal masculine connotations (Burke Citation2014, 95).

In the early 2000s, Osmond (Citation2008) stated that (sports) historians have tended to neglect a serious engagement with photographs, and Booth (Citation2005) was being critical of how sports historians have utilised visual material. Since then, the gap has steadily been filled. Visual sources are increasingly being used, and historians are developing visual methodologies (Huggins Citation2015). However, the theoretical achievements of interpreting how photographs interlink with contextual and cultural organising principles, and how photographed (sporting) men and masculinities connect to a broader context of cultural hegemony, still need to be explored. To achieve this, the article draws inspiration from the CSMM field, which, among other things, has identified sport as society’s key definer of masculinity and social status (Connell Citation1983, Citation2005; Messner Citation2012, Citation1992). Given the popularity and potential of such material to create heroes and heroines, and the impact that sporting institutions and individuals have had on contemporary societies, photographs of sports and sporting events are particularly interesting to study (Huggins and O’mahony Citation2011). This article thus adds to what Huggins and O’mahony (Citation2011, 1090) call ‘skills in “visual literacy”’.

In the article, the sport of Swedish ice hockey constitutes the cultural case. The analysis is developed from four photographs, which in turn are connected to a broader Swedish context beyond sports to contribute to a more critical understanding of men’s hegemony (Hearn Citation2004). However, before turning to the analysis, a theoretical discussion about (photographed) hegemony, men and power is in order.

Bridging the content and objects of photographs: the material-discourse as ontology and epistemology

In their introduction to the anthology Photographs, Objects, Histories: On the Materiality of Images, Edwards and Hart (Citation2004, 2) explain how ‘photographs have inextricably linked meanings as images and meanings as objects; an indissoluble, yet ambiguous, melding of image and form’. The authors point out that a visual methodology should not solely focus on the content of photographs, but also include their presentational form as a material object. The relation between an image’s content and its material form is dialectical, or a dialogue. In this sense, and to borrow Ray’s (Citation2020) words, a photograph is essentially ambivalent. Materiality functions as an anchor that transcends abstract and discursive content into time and space (Edwards and Hart Citation2004). Although a photograph’s materiality and discursivity are indistinguishably connected, some researchers only focus on its materiality (see, e.g. Osmond Citation2008), while others focus on the ‘pictorial turn’ and an image’s discursive content (see, e.g. Mitchell Citation1995).

This ambivalence has been well noted in photographic theory (Berger Citation1972; Edwards and Hart Citation2004; Mitchell Citation1995). Here I discuss how a photographic object and its content connect with the structural gender ideals and the current dominant cultural hegemony. The ambiguity of photographs echoes the debate about how a man, as a material or biological body of muscles and blood, connects to cultural or discursive understandings of masculinity, femininity and other forms of identity. The aim here is to theorise the connection between a photograph and the ideals of the dominant hegemony of men.

If we acknowledge a photograph’s inextricable ambivalence of ‘being’ an object and an imagination, a correlated epistemological and ontological understanding is inevitable. Here, I turn to Hearn’s (Citation2014) conceptualisation of a material-discursive approach to men and masculinities. Echoing Ray’s (Citation2020) description of an essential ambivalence, and recognising the difficulty of simultaneously considering materiality and discourse and challenging and reaching beyond this dichotomisation, Hearn’s (Citation2014) describes the ontology of the material-discursive as a ‘persistent uncertainty’. More specifically, Hearn’s (Citation2014, 8) writes that ‘ … the ontological includes the non-human, and is not only human, even if humanly constructed; the epistemological is (still) fundamentally human, even if the human is not a strictly separate category’.

Acknowledging a photograph’s materiality and discursivity also has consequences for how it is interpreted (an action that is dependent on a body’s materiality). In short, a photograph might be understood differently if the viewer looks at it in the Hockey magazine surrounded by other photographs and texts, vis-á-vis looking at a cut-out version digitally on a screen. Echoing Kant’s description of das Ding an sich (the thing a priori in itself) and das Ding für sich (the object a posteriori of experience), interpreting the pure content of a photograph is almost impossible, in that it involves experiencing a dimension of the thing. Even Edwards and Hart (Citation2004) maintain that experiencing an object beyond interpretation is impossible. When it comes to positioning the interpretation in the ambivalent and material-discourse paradigm, a central point for Hearn’s (Citation2014) and for Edwards and Hart (Citation2004) is that it opens up new possibilities of complexities.

The contextual meaning of a photograph is thus shaped by its materiality and the sociability of this materiality. This characteristic of how the material intersects with discourses of power (Edwards and Hart Citation2004) enables a connection between a photograph and society’s masculinity ideals of the dominating hegemony of men (Hearn Citation2004, Citation2014; Howson Citation2006).

How men’s power ‘travels’ through time: transcending photographed men and masculinities in place and time

Interpretation is always conducted in a particular situation, from a specific standpoint (and can say more about the interpreter than the interpreted), and masculinity per se is particularly problematic to define. Connell (Citation2005, 67) believes that the term ‘has never been wonderfully clear’ among researchers. Pure materialism, or essentialism, may advocate the existence of a certain type of maleness, such as facts, hormones or other aspects that can be measured and pointed at. Sex testing reveals that these views are widespread and deeply rooted in sports’ international organisations (Heggie Citation2010). Pure discursivity, or normativism, points to human bodies and gender as socially constructed or interpreted and in a continuous mode of doing or becoming (Butler Citation2004). Several sports also function like this by separating, defining, formulating and actualising appropriate and gendered performances. Finally, according to Connell, semiotic perspectives, or symbolisms, place masculinities in a system of symbolic differences (between men and women and between men and other men). This perspective characterises many cultural analyses and shows that multiple dimensions of masculinity(−ies)/femininity(−ies) change in ways that differ from essentialism. Partly as a critique against Connell’s work, Hearn’s (Citation2014) developed the combination of the material-discourse, where men/masculinity is not merely discursive but also material with physical aspects, such as bodies that age, hair that grows and becomes grey, and that these corporeal changes will be interpreted differently in different situations and contexts (see, e.g. Hearn Citation2014).

In this way, photographed men and masculinities (as objects and materiality) become important as social categories as discursive practices and structures, creating their connotations to societal power and status. This means that analytically and at a given moment, portrayed men and masculinities can be sorted into a social hierarchy in which certain bodies, characteristics and ideals are placed closer to or more distant from the most influential, status-loaded and powerful position – the masculinity ideals of the current dominant hegemony (Howson Citation2006). Conversely, other men/masculinities and women/femininities can be analytically categorised as marginalised or subordinated (Connell Citation2005), where the specific boundaries between these positions are challenging to show empirically. Connell (Citation2005) also launches a fourth position (entitlement/the entitled man/masculinity), which includes men who in some way benefit from the masculinity ideal(s) of the dominant hegemony without necessarily embodying them or sympathising with the hegemony themselves. As masculinity can be regarded as interpersonal material-discursivity, it activates dimensions of social power. How this power can be traced in visual literacy is of particular interest in this article.

The material-discursive ontology and epistemology also affect the relation between the present and the past. Even if a situation occurs in the present, it bears mnemonic traces of the past. The situation’s attachment in materiality causes this transcendence from the past to the present. In the same way, according to Ricœur (Citation2005), our interpretations work in a way that what is contemporarily regarded as influential or powerful also reflects a perception of the past. Traces of the past, for example, cultural traditions, contribute to the stability of a present hegemony. However, the present allows us to challenge, negotiate and question the hegemony (Howson Citation2006), which means that the past can only leave traces to the future (through traditions, path dependence and so on) and thus cannot entirely control it. This interpretive condition also characterises how individuals are perceived. For example, a portrayed individual’s past can enhance and affect their perception of themselves as objectified in a photograph or other situations. This is of interest to historians, in that it articulates hegemony’s ‘ability’ to stretch and move from one situation to another and from one time and place to another with traces of a retained social hierarchy. In this context, Connell (Citation2005, 72) introduces the concept of ‘configurations’, where ‘masculinity’ and ‘femininity’ are configurations of gender practices and, in this way link to processes ‘before’ or ‘surrounding’ a specific action in a given situation.

Historians have long been interested in the reproduction of power and how its ingredients and configurations can be connected to different situations that are more or less intertwined in chains of actions. This aspect is further discussed below in an analysis of how photographs representing men/masculinities in sports can contribute to understanding men’s hegemony in more general terms.

Interpreting a photograph: convention, context and complexity

Although the pure past (what Leopold von Ranke labelled as ‘wie es eigentlich gewesen ist’) is unreachable and in constant connection with a present discourse, interpreting photographs for a contextual and historical understanding (Dodge Citation2006) can be problematic. Burke’s (Citation2014) describes this as a problem of identifying the narrative’s convention, i.e. its discourse. This illustrates how photographs can contain multiple and sometimes conflicting discursive narratives. This complexity makes photographs such a potent source for historical studies (Huggins and O’mahony Citation2011).

From a more materialist perspective, a photograph can be decomposed into chemical or digital substances as an exposed relic to a certain amount of light (‘photography’ means writing with light). A traditional or analogical photograph literally carries the trace of light from the past and, in that sense, interconnects the past with the present. However, a photograph that illustrates the past is not the past but can be understood as a material relic experienced through a present discourse. Here, researchers take different positions on what can be summarised as a continuum between materialism and semiotics. While some interpret photography as a physical object with a social role that can be presented, distributed and consumed, others instead emphasise the content and interpretations of a photograph (Berger Citation1972; Osmond Citation2008; Edwards and Hart Citation2004).

A photograph is never value-neutral or taken from an eternal and objective standpoint. Rather, it is chronologically multifaceted and anchored in the time in which it was taken and interpreted. As a narrative source, it stands between the objectification of a past action and the experience of it. As Dodge (Citation2006, 352) writes, ‘We frame the past relative to our location in the present’. This (interpretative) action depends on the past and the present, experience and competence, object and identity, where the subject’s visual literacy constitutes the interpretive process and meaning-making. Dodge (Citation2006, 355) continues,

Representations of the real are tools for self-understanding, and, in the absence of any coherent metanarratives which structure, contain and provide the parameters of ways of being in the world, we seek answers through a therapeutic mode of existence, drawing on all available representations flowing from seemingly limitless sources.

In other words, we seek meaning in images and in so doing we try to work out who we are. This applies to the consumer of a photograph, the photographer and the function of a photograph (as in recording, narrating, selling, promoting, etc.). It is therefore important to be aware of the cultural context and the assumptions and (often tacit) agreements that prevail or prevailed when the photograph was taken. The Foppa hallmark exemplifies this. If he had shot the penalty home in any other game, its reception would likely have been different.

It is now time to turn to other photographs to show how they interconnect with the contextual ideals of the dominating hegemony.

Analysing photographs within the material(-)discourse

One of Gramsci’s central points is that social power not only works through economic activities but also through cultural channels. By studying and exposing how photographic or visual mechanisms, details and techniques contribute to presenting and promoting men/masculinities as the norm and as having a higher status than women (and other marginalised social groups), a critical analysis of social power and hegemony can be accomplished. Obviously, the step from analysing a photograph of a male ice hockey player to the consequence of maintaining patriarchal power structures is somewhat grandiose and abstract and, not least, constitutes an empirical challenge. The purpose of this article is not to prove this connection, but rather to discuss it and point out the connectedness. Below, five theoretical and methodological assumptions are discussed when photographs are used as data in historical analyses. The article then ends with some concluding reflections.

Capturing hegemony photographically – the epistemological and ontological condition

An initial condition for the argument put forward in this article is that men’s hegemony can be captured photographically. In line with Jeff Hearn’s work, it is stipulated that patriarchal power structures (the hegemony of men) and their dominating masculinities (Howson Citation2006) exist materially and discursively (Hearn Citation2014). From a visual methodological perspective, it requires that these power mechanisms can be portrayed, objectified or materialised in certain situations and then captured by a photographer. The photogenic capacities of economic and cultural power derive from their attachment to materiality. However, it is not only materiality that is captured, in the same way as a thing cannot be photographed and objectified merely a priori. The metaphor of the relation between the eye and its vision is useful here and indicates how materiality inevitably connects with discourse – without the material eye there would be no vision, and vice versa.

Capturing cultural dominance strategies and its complexity

Theoretically defining and empirically identifying and visualising ‘power’ and ‘masculinity’ is challenging. Combining a Gramscian understanding of power with feminist research, Connell (Citation2005, 77) defines ‘hegemonic masculinity’ as ‘the configuration of gender practice which embodies the currently accepted answer to the problem of the legitimacy of patriarchy, which guarantees (or is taken to guarantee) the dominant position of men and the subordination of women’. However, this (con)figuration and dominance is seldom obvious in visual documentation. Connell continues and writes that dominance can be maintained with the aid of several strategies where heterosexuality, whiteness, masculinity, economic income and social status are influential (Connell Citation2005). Therefore, such strategies are essential to look for when interpreting photographs, even if they also contain pitfalls. Hegemonic power, as a process and a historical yet complex, stability, can also form hybrid versions that sometimes incorporate attributes of marginalised or subordinated groups without disturbing the fundamental conditions of power distribution (Bridges and Pascoe Citation2014, Citation2018). Typical examples are men wearing earrings or other attributes that in Western culture are associated with marginalised groups. Since gender and power are complex, one could expect ice hockey men to be portrayed in different ways and in different situations. A consequence of this repertoire of possibilities is that they create entitlement and that the hybridity or complexity strengthens the hegemony’s overall stability.

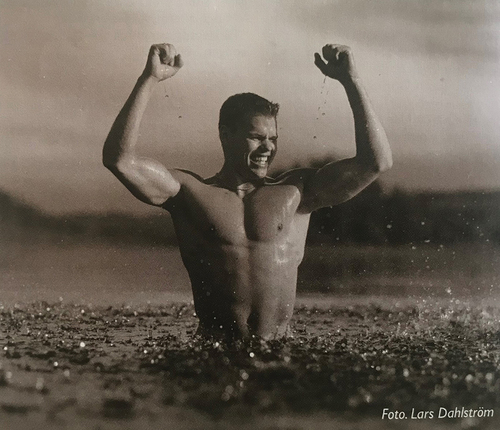

Capturing visual techniques that ‘activate’ the innate objective male protagonist

A photograph of a man means that he, as a social subject, has been materialised or objectified into a photographic image. Objectification is often associated with strategies aimed at marginalising or subordinating a social group or subject (Cooky, Messner, and Musto Citation2015). A photographic technique that ‘manages’ and attempts to ‘eliminate’ the objectifying nature of a photographed subject is to allow the portrayed person to be perceived as active and thereby create a narrative that alludes to the opposite of a passive object (Alsarve Citation2018). Metaphorically speaking, this is a discursive struggle over materiality. For example, if an ice hockey man is exposed shirtless, it risks objectifying and even ‘sexualising’ him (see ). By instead zooming in on his upper body, having the protagonist stretch his hands to the sky, symbolising winning and dominance, and tensing his torso and arm muscles, the objectifying (and sexualising) narrative strategically ‘disappears’ from the picture and guides the viewer into interpreting the subject as strong and successful (as though he has recently won or perceived something). At the symbolic level, the surrounding sea is also a typical metaphor, where the male subject’s struggle against and ultimate control of the sea recurs throughout history.

At an abstract level, the photograph represents a version of the dichotomy of culture and nature, where the muscular man (as culture) easily and happily ‘controls’ and plays with the water (nature). The protagonist’s gaze is focused on something in the distance, which gives the impression that he is busy, or that the situation might suddenly change. The camera angle is also crucial, since the ice hockey man’s head and arms are placed above the horizon, which is recognisable as a dark grey horizontal shadow in the background.

All photographs activate the stimulating ambivalence of materiality and discourse. The drops of water on the surface give the impression of someone splashing water onto the protagonist (a teammate or a friend?). The materiality of the seawater and the man’s body collide, causing a smiling face – the discursive consequence of enjoying the moment.

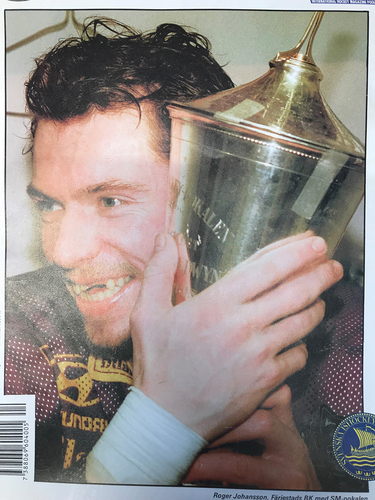

Capturing the symbols of power

Linked to the above flexing of muscles are techniques that allude to and symbolise power, status and influence. Here, one of the most classic symbols is a man smoking a cigar (think of Winston Churchill, for instance). Other symbols include holding a trophy, standing beside an exclusive car or simply wearing a national team shirt. The function of these symbols is to link the portrayed material (male) subject to discourses of power, successfulness and influence. Taking the image below as an example, it reveals that the portrayed situation involved some kind of past struggle in that the man holding the trophy has teeth missing (see ). Even though the subject appears to be passive, the trophy and the missing teeth reveal a struggle and success, thus dissolving the risk of being portrayed as purely inactive or objectified.

In this photograph, the protagonist’s right wrist is bandaged, which activates the materiality of pain and change. The smile and the steady gaze beyond the frame signal something about him, namely that he has overcome the pain and the ‘borders’ of his body’s materiality (Messner Citation2012). This discursive domination over materiality symbolises the player’s power and status. The photograph is on a cover of the Hockey magazine, which is also of symbolic importance. The missing teeth and the absent materiality echo his vulnerability, and thus add a dimension of complexity to the image: that even the most successful and status-loaded (discursive) subject is anchored in material fragility.

Capturing entitlement, such as heterosexuality and change/continuity

One important consequence when operating within the material-discursive paradigm is that ‘obvious’ material observations are often more complex than they seem at first glance. Above, Connell’s (Citation2005) and other scholars’ difficulties in defining ‘masculinity’ are mentioned, which shows how performing, or even embodying, masculinity traits is not exclusively conditioned by bodies with penises. A similar reasoning applies to skin colour, where not only bodies with a light pigment always embody whiteness. The relation between materiality and discourse is more complex with interconnected similarities and differences.

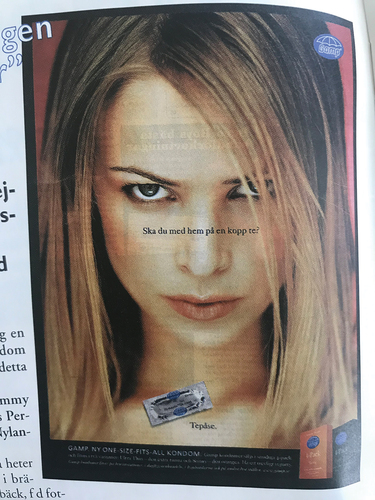

As a man, embodying masculinity and whiteness, which are often privileging traits and ideals, is a key factor in the formation of a dominant hegemony (Connell Citation1983, Citation2005; Howson Citation2006; Hearn Citation2015). Although now becoming increasingly contested by researchers (Anderson Citation2009), heterosexuality is still a powerful hegemonic discourse and materiality. Regarding the ability to be photographed, the materiality of heterosexuality in this article’s ice hockey case is rather more challenging to portray than ideal whiteness and masculinity. Most images show men’s camaraderie and men-only teams, which could signal a homosocial or homosexual presence. One of the best examples of the idealness of heterosexual desire is an advertisement for condoms in the Hockey magazine (see ). The brand of the condoms is called ‘Gamp’, and a new ‘one-size-fits-all’ condom is launched in the magazine. The company was run by three ice hockey players, which could explain the somewhat laddish term of ‘Gamp’, which is slang for umbrella. A man capable of producing seminal fluid that requires an umbrella for protection signals an extreme masculine potency. In the advertisement image, a woman’s face is portrayed with a come-hither look and the text ‘Do you want to come home for a cup of tea?’ This discourse typically includes a last dance after a night out and how to ask someone home for continued social intercourse. With humoristic intentions, a condom accompanied by the text ‘tea bag’ is placed underneath the woman’s face.

The image addresses a subject who uses a condom (probably a man) and alludes to a classic line of inviting someone home for something more intimate than a cup of tea. Although the photo frame mainly shows the woman’s face, the viewer could surmise that she is not wearing any clothes, given the exposure of a naked throat and upper part of the body. Again, absent materiality is interconnected with the invitational discourse in which the condom (as a symbol) is of material-discursive importance. Connecting a woman without clothes to a condom is, from a more critical perspective, a technique that objectifies and sexualises women/femininities.

Another example of heterosexuality as a norm is shown in the photograph below of two national team players walking on a street with their families in the city of Feldkirch in Austria (in front of Gasthof Lingg), where they live as professional ice hockey players (see ). Surrounded by buildings, the photograph shows the players’ two families in a public place with three, or possibly four people in the background. The wives are walking beside the players, with two children walking hand in hand in front of them, one player is carrying his youngest child and the other player’s wife is carrying their youngest child in her arms. Indicating heterosexual and, as they are smiling, happy relationships, this portrayal also includes some discursive complexity in that the players are seen as ‘just’ partners or fathers and not primarily ice hockey players. On the one hand, such photographs break with a typical image of an ice hockey player, although on the other hand confirm the heteronormativity of the dominant hegemony (cf. Allain Citation2008, Citation2011).

If this image is compared with the condom advertisement, we can, as a final analytical step, see how heterosexuality, as a norm, could include the discourse of men as monogamous as well as men being more loosely sexually active without stigmatisation.

Placing photographs in a cultural hegemony: conclusive discussion

Historically, ice hockey games have been known for their tough, intense and often violent ingredients (Lorenz Citation2015; Lorenz and Osborne Citation2006). It is, therefore hardly surprising that researchers have described ice hockey as a masculine and macho-like culture, where teams often form a homosocial camaraderie characterised by a laddish jargon (Alsarve Citation2021; Alsarve and Angelin Citation2020). In several places in the northern and western hemispheres, ice hockey (and other sporting) men and the masculinities they portray are regarded as important role models. The popularity of male (and even some female) players (even those who have retired) and the fascination of their skills, scars, and commitment reveals the culture’s significance (Alsarve Citation2021; Young and White Citation1995). However, ice hockey should not be considered an unambiguous or static culture. For example, training methods and tactics are continuously optimised for winning games; new arenas are designed to enhance the spectators’ experiences of the game; TV broadcasts are steadily developed with more cameras, unique angles and close-ups to attract viewers at home and so on. Rules and referees are also important elements in these commercial, professional, medial and optimising endeavours (Mason Citation2012; Scherer and Davidson Citation2011; Carlsson, Backman, and Stark Citation2020).

To reiterate, men who play ice hockey form a social material-discursive category that includes variations and contradictions (Allain Citation2008, Citation2011), albeit with the dominant hegemony’s chords of heterosexism, whiteness and masculinity as permeating edges. Variation and complexity also characterise the conditions for how the dominant hegemony changes. Photographically, superficial change or hybridity (Bridges and Pascoe Citation2014, Citation2018) is easier to capture over time, such as how haircuts, fashion, equipment, clothes and the like change. Ice hockey players holding a victory trophy will probably always be an important way of portraying them. Being associated with a victory trophy strengthens one’s status and is evidence of a successful striving for domination (Messner Citation2012, Citation1992). Similarly, it is also essential to see how material fashion and clothing choices carry meanings of discursive status.

Since the 1990s, some European countries host professional and highly commercialised leagues with ice hockey games broadcast each week. Some researchers argue that the sport has reached a hegemonic position in relation to other sports, which means that it (the professional leagues and their associated organisations) directs decisions and influence the national sports movement in general (Ahonen Citation2020). Professional ice hockey players as ‘stars’ thus symbolise cultural status and even national masculinity, so-called hegemonic ideals (Allain Citation2008, Citation2011). Still, at the same time, the distinct conditions for these ideals formed a thin line between (un)accepted behaviour. In more general terms, this shows how the construction of identity ideals is always complex and multifaceted. Expressed in more theoretical terms, the materiality of bodies and the discursivity of ideals create the potential for continuity, complexity and change.

This article has focused on a theoretical discussion about how to analyse masculinities and power in historical research based on imagery and visual sources from a material-discursive point of departure. Using four photographs from Swedish ice hockey’s past as examples, I have shown how they include discursive and material meanings of masculinity, status and domination, and how such embodiments interconnect with a contextual configuration of the dominant hegemony of men. In line with Gramsci and several CSMM scholars, the dominating hegemony’s ability to reproduce its power via cultural artefacts has been in focus. This power effectively transmits discursive values and material ideals, where photographs as cultural artefacts have a given place. Chronologically, a photograph of, for example, an ice hockey player scoring a penalty in a decisive tournament final ‘eternalises’ and transforms the situation into a material-discursive image, which then is possible to reproduce and share. But ideals of men and masculinities were also distributed in other and more subtle ways and these variations display the reproductive potential of hegemonic power.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Daniel Alsarve

Daniel Alsarve (PhD in history, docent in sport science) is a researcher in sport science at Örebro University, Sweden and Jyväskylä University, Finland. He recently finished a four-year project, ‘Ice hockey in change: Masculinity ideals and violence norms in Swedish hockey ca. 1965 until the present,’ funded by the Swedish Research Council for Sport Science. His research interests include sports, gender, violence, democracy, and historical change. He is currently involved in research projects about managing social sustainability in high-performance sports organisations in Finland, how the corona pandemic affected Swedish sports, and how the Swedish Sports Confederation organised this crisis. In 2021 Alsarve was rewarded the ‘Little Prize for Sports Science’ by the Swedish Central Association for the Promotion of Athletics.

References

- Ahonen, A. 2020. “Strong Entrepreneurial Focus and Internationalization – The Way to Success for Finnish Ice Hockey: The Case of JYP Ice Hockey Team.” Sport in Society 23 (3): 469–483. doi:10.1080/17430437.2020.1696531.

- Allain, K. A. 2008. “’Real Fast and Tough”: The Construction of Canadian Hockey Masculinity.” Sociology of Sport Journal 25 (4): 462–481. doi:10.1123/ssj.25.4.462.

- Allain, K. A. 2011. “Kid Crosby or Golden Boy: Sidney Crosby, Canadian National Identity, and the Policing of Hockey Masculinity.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 46 (1): 3–22. doi:10.1177/1012690210376294.

- Alsarve, D. 2018. “’Power in the Arm, Steel in the Will and Courage in the breast’ – a Historical Approach to Ideal Norms and Men’s Dominance in Swedish Club Sports.” Sport in History 38 (3): 365–402. doi:10.1080/17460263.2018.1496948.

- Alsarve, D. 2021. “Historicizing Machoism in Swedish Ice Hockey.” The International Journal of the History of Sport 38 (16): 1688–1709. doi:10.1080/09523367.2021.2022649.

- Alsarve, D., and M. Angelin. 2020. “‘It’s Freer and Easier in a Changing Room, Because the Barriers Disappear … ’ a Case Study of Masculinity Ideals, Language and Social Status Amongst Swedish Ice Hockey Players.” European Journal for Sport and Society 17 (1): 26–46. doi:10.1080/16138171.2019.1706239.

- Anderson, Eric. 2009. Inclusive Masculinity: The Changing Nature of Masculinities. New York: Routledge.

- Berger, John. 1972. Ways of Seeing: Based on the BBC Television Series with John Berger. London: British Broadcasting Corporation and Penguin books.

- Booth, D. 2005. The Field: Truth and Fiction in Sport History. London: Routledge.

- Bridges, T., and C. J. Pascoe. 2014. “Hybrid Masculinities: New Directions in the Sociology of Men and Masculinities.” Sociology Compass 8 (3): 246–258. doi:10.1111/soc4.12134.

- Bridges, T., and C. J. Pascoe. 2018. “On the Elasticity of Gender Hegemony Why Hybrid Masculinities Fail to Undermine Gender and Sexual Inequality.” In Gender Reckonings, edited by James W. Messerschmidt, Patricia Yancey Martin, Michael A. Messner, and Raewyn Connell, 254–274, New York: NYU Press.

- Burke, P. 2014. Eyewitnessing: The Uses of Images as Historical Evidence: Picturing History. London: Reaktion Books.

- Butler, Judith. 2004. Undoing Gender. New York: Routledge.

- Carlsson, B., J. Backman, and T. Stark. 2020. “Introduction: The Progress of Elite Ice Hockey Beyond the NHL.” Sport in Society 23 (3): 355–360. doi:10.1080/17430437.2020.1696518.

- Connell, Raewyn. 1983. Which Way is Up?: Essays on Sex, Class and Culture. London: Allen & Unwin.

- Connell, R. 2005. Masculinities. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Cooky, C., M. A. Messner, and M. Musto. 2015. “’it’s Dude Time!’: A Quarter Century of Excluding Women’s Sports in Televised News and Highlight Shows.” Communication & Sport 3 (3): 261–287. doi:10.1177/2167479515588761.

- Dodge, B. 2006. “Re-Imag(in)ing the Past.” Rethinking History 10 (3): 345–367. doi:10.1080/13642520600816122.

- Edwards, Elizabeth., and Janice Hart. 2004. “Introduction: Photographs as Objects.” In Photographs, Objects, Histories: On the Materiality of Images, edited by Elizabeth Edwards and Janice Hart, 1–15. London: Routledge.

- Gramsci, Antonio. 2000. “X Intellectuals and Education.” In The Gramsci Reader: Selected Writings, 1916-1935, edited by David Forgacs, 300–22. New York: New York University Press.

- Hearn, Jeff. 2004. “From Hegemonic Masculinity to the Hegemony of Men.” Feminist Theory 5 (1): 49–72. doi:10.1177/1464700104040813.

- Hearn, Jeff. 2014. “Men, Masculinities and the Material(-)Discursive.” Norma: International Journal for Masculinity Studies 9 (1): 5–17. doi:10.1080/18902138.2014.892281.

- Hearn, Jeff. 2015. Men of the World: Genders, Globalizations, Transnational Times. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Heggie, V. 2010. “Testing Sex and Gender in Sports; Reinventing, Reimagining and Reconstructing Histories.” Endeavour (New Series) 34 (4): 157–163. doi:10.1016/j.endeavour.2010.09.005.

- Hockey: officiellt organ för Svenska ishockeyförbundet [Official Mouth Piece of the Swedish Ice Hockey Association].Bjästa: CeWe-förlaget.

- Howson, R. 2006. Challenging Hegemonic Masculinity. London: Routledge.

- Huggins, M. 2015. “The Visual in Sport History: Approaches, Methodologies and Sources.” The International Journal of the History of Sport 32 (15): 1813–1830. doi:10.1080/09523367.2015.1108969.

- Huggins, M., and M. O’mahony. 2011. “Prologue: Extending Study of the Visual in the History of Sport.” The International Journal of the History of Sport 28 (8–9): 1089–1104. doi:10.1080/09523367.2011.567765.

- Kidd, Bruce. 1987. “Sports and Masculinity †.” Sport in Society 16 (4): 553–564. doi:10.1080/17430437.2013.785757.

- Kinsey, F. 2011. “Reading Photographic Portraits of Australian Women Cyclists in the 1890s: From Costume and Cycle Choices to Constructions of Feminine Identity.” The International Journal of the History of Sport 28 (8–9): 1121–1137. doi:10.1080/09523367.2011.567767.

- Lisle, B. D. 2011. “’we Make a Big Effort to Bring Out the Ladies’: Visual Representations of Women in the Modern American Stadium.” The International Journal of the History of Sport 28 (8–9): 1203–1218. doi:10.1080/09523367.2011.567772.

- Lorenz, S. L. 2015. “Hockey, Violence, and Masculinity: Newspaper Coverage of the Ottawa ‘Butchers’, 1903–1906.” The International Journal of the History of Sport 32 (17): 2044–2077. doi:10.1080/09523367.2016.1147431.

- Lorenz, S. L., and G. B. Osborne. 2006. “’talk About Strenuous hockey’: Violence, Manhood, and the 1907 Ottawa Silver Seven-Montreal Wanderer Rivalry.” Journal of Canadian Studies 40 (1): 125–156+253. doi:10.3138/jcs.40.1.125.

- Mason, D. 2012. “Expanding the Footprint? Questioning the Nhl’s Expansion and Relocation Strategy.” In Artificial Ice, edited by David Whitson, Richard Gruneau, and In Hockey, 181–200, Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Messner, Michael A. 1990. “When Bodies are Weapons: Masculinity and Violence in Sport.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 25 (3): 203–220. doi:10.1177/101269029002500303.

- Messner, Michael A. 1992. Power at Play: Sports and the Problem of Masculinity. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Messner, M. A., M. Dunbar, and D. Hunt. 2000. “The Televised Sports Manhood Formula.” Journal of Sport & Social Issues 24 (4): 380–394. doi:10.1177/0193723500244006.

- Mitchell, W. J. T. 1995. Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press.

- Osmond, G. 2008. “Reflecting Materiality: Reading Sport History Through the Lens.” Rethinking History 12 (3): 339–360. doi:10.1080/13642520802193205.

- Poole, Deborah. 1997. Vision, Race, and Modernity: A Visual Economy of the Andean Image World. Princeton, N.J: Princeton Univ. Press.

- Ray, L. 2020. “Social Theory, Photography and the Visual Aesthetic of Cultural Modernity.” Cultural Sociology 14 (2): 139–159. doi:10.1177/1749975520910589.

- Ricœur, P. 2005. Minne, Historia, Glömska [Memory, History, Oblivion], edited by Eva Backelin. Göteborg: Daidalos.

- Scherer, J., and J. Davidson. 2011. “Promoting the ‘Arriviste’ City: Producing Neoliberal Urban Identity and Communities of Consumption During the Edmonton Oilers’ 2006 Playoff Campaign.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 46 (2): 157–180. doi:10.1177/1012690210387538.

- Smith, L. R. 2014. “Up Against the Boards: An Analysis of the Visual Production of the 2010 Olympic Ice Hockey Games.” Communication & Sport 4 (1): 62–81. doi:10.1177/2167479514522793.

- Teus. 2006. ‘Kenta Nilsson Goal Vs USA’.

- yosoo. 2023. Elias Pettersson Forsberg Shootout Goal vs Hurricanes (Jan. 15, 2023) [Video]. Accessed 3 March 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yqw5jYZmR1w

- Young, Iris Marion. 1980. “Throwing Like a Girl: A Phenomenology of Feminine Body Comportment Motility and Spatiality.” Human Studies 3 (2): 137–156. doi:10.1007/BF02331805.

- Young, K., and P. White. 1995. “Sport, Physical Danger, and Injury: The Experiences of Elite Women Athletes.” Journal of Sport & Social Issues 19 (1): 45–61. doi:10.1177/019372395019001004.