ABSTRACT

Medievalist video games are often embedded with complex modern militarism. Though the military-industrial-media-entertainment-network is a well-discussed issue in relation to video games, much of this work focuses on first-person shooters and representations of modern military combat. This same militarisation operates through more covert mechanics in medievalist video games – games set deliberately in a distanced, often fantastical, world – but the same logistical, schematic thinking and messaging is still hidden amongst the longbows and castles. This article analyses this phenomena using the 1991 Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves Nintendo video game as a case study text within which two distinct military temporalities operate simultaneously: the 1991 Gulf War and the medieval crusades. It examines the legacies of crusading medievalism but with particular concern for militarism and hypermediacy, exploring the way the American military context of the early 1990s resonates through this game text, particularly through its conceptions of violence and the body of the soldier. The rhetorical power of normalising militarised logistical thinking is significantly increased when it also coalesces with medievalism, and even seemingly simplistic games like Prince of Thieves form a crucial part of the legacy that today manifests in hyper-realistic shooter games that perpetuate racialized violence.

Video gaming occupies a complex position within militainment culture. Though the thematic prevalence of modern warfare and violence is well-covered ground, the same underlying militarisation also operates through more covert mechanics in video games inspired by the medieval world – a world deliberately distanced, often fantastically, from our own, but where the same logics and messages can be even more subtly hidden amongst longbows and castles. This extends beyond just the centrality of violence mechanics or warfare-themed settings and is more concerned with the way that particularly modern militarised logistical tendencies and ontologies shape the way we interact with virtual simulations of past worlds.

This article analyses this phenomena using the 1991 Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves Nintendo video game as a case study in which two distinct military temporalities operate simultaneously: the 1991 Gulf War and the medieval crusades. These two contexts are powerfully present in the game, wherein complex modern military thought, particularly around conceptions of violence and the body of the soldier, is embedded in within broad, often reductive, medievalisms. In her work on crusader medievalism, Kristin Skottki (Citation2018, 124) argues that open and ‘relentless historicization and contextualization’ is necessary to continue to resist and understand the ongoing appropriations of crusade history, a call taken up by Mike Horswell (Citation2022) in his analysis of Assassin’s Creed as a historical artefact in how it reflects its creator’s conception of the crusades. It is in this vein that I historicise the Prince of Thieves game amongst the technological and military contexts of Gulf War America, to demonstrate the need for further close integration of game and media studies theories about militainment into understandings of medievalism and crusading legacies. Lorenzo Servitjethe has similarly argued that the video game Dante’s Inferno represents a ‘violent rewriting of historical media via the computational logistics inherent to video games’ (Servitje Citation2014, 371). This consideration of the interplay between medievalism and militarised logistical tendencies is crucial for understanding the implicit and procedural meanings produced through crusade-themed video games. Though the narrative of the Prince of Thieves game is important, as I have analysed elsewhere (Watterson Citation2023), my analysis here focuses specifically on historicising the hypermediacy and mechanics of the game form itself as contributing to the game’s crusader medievalism. I first situate Prince of Thieves in the historical context of crusader medievalism in Gulf War America, then the concepts of militarised logistical thinking at play in the game, finally examining how these two factors manifest through key aspects of the game form.

Medievalism, that is the post-medieval construction of the idea of the Middle Ages, ripples throughout video games across time, place, and genre. The study of ludic medievalism is thus a rapidly growing field within medievalism and historical game studies (see, e.g. Kline Citation2014; Robinson Citation2008; Romera, Ángel Nicolás Ojeda, and Ros Velasco Citation2016). I refer here to the ‘medievalist’ crusades to foreground that I refer not to the past event of the medieval crusades, but specifically to the way these crusades have been imagined and reinvented throughout centuries of medievalism. It is similarly a useful shorthand to refer to games set in or inspired by the middle ages – medievalist games – that foregrounds their positioning within traditions of medievalism.

The 1991 Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves console game is a video game tie-in to the blockbuster film of the same name, released alongside the film and a range of other toys and paraphernalia. The game, as the film, broadly follows a crusader Robin returning home to England to fight for his land and people against the corruption of the new Sheriff of Nottingham. However, the game offers ‘more than just a remediated version of the same story’ (Watterson Citation2023, 50). As I have previously argued, the film to game adaptation here was shaped by ‘the history of the action adventure game genre, of franchise media, and of movie-adaptation games’, resulting in a ‘significantly different vision of the Middle Ages’ (2023, 50–51). In this article, I now expand on my previous argument that the film’s messages around warfare are significantly changed when adapted through the conventions of video game violence, by here applying, as Skottki suggests, a relentless historicization of these conventions as they were encountered by their contemporary audience in America at the time of the first Gulf War.

I thus begin with an anecdote from the Nintendo Power magazine that perfectly illustrates the way these entwined themes were encountered in this historical moment. The walkthrough article on Prince of Thieves in the July 1991 issue of Nintendo Power follows immediately after an article titled ‘A Strategic Victory for Game Boy’, which is a ‘letter to the editor’ style piece from a Gulf War veteran. In this article is the text of a short letter written to Nintendo, and their response, regarding a Gameboy device that survived the first Gulf War. The letter was from an Operation Desert Storm nurse, describing how his Game Boy (shown in two photographs) and some personal items were ‘the only casualties claimed by a fire while I was stationed in the Middle East’. Nintendo’s response refers specifically to ‘Stephen’s Game Boy from the Middle East’, and despite the device still working, they agree to replace the unit as a ‘special “Desert Storm” courtesy’. Even this short article plays on the language surrounding Gulf War violence, jokingly noting that there were no casualties other than technology. This short article is a poignant example of the complicated relationship in the video game industry between militarisation, entertainment (militainment?), pop culture and consumerism. It also demonstrates the media landscape within which Prince of Thieves was consumed – the Prince of Thieves walk-through was only a magazine page away from this article about Nintendo and the Gulf War.

Robin Hood, crusader medievalism, and the Gulf War

During the first Gulf War, the Bush administration’s anti-Iraq propaganda centred on legitimising the conflict as a moral crusade and a ‘just war’, frequently through rhetorics of crusader medievalism (see, e.g. Gutwein and Menache Citation2002, 388–9; Muscati Citation2002, 134–5). This rhetoric has then been consistently employed by the American government and media throughout America’s more recent history with Iraq and the Middle East (see, e.g. Gutwein and Menache Citation2002, 390; Kellner Citation1992; LaMay, FitzSimon, and Sahadi Citation1991; Richards Citation1999, 215). Through centuries of representations, ‘the Crusades have become an embattled theatre of operations for a mass-society intent on waging its wars of demagoguery over analogies between medieval and the contemporary “clash of civilizations”’ (Haydock Citation2009, 1; see also Horswell Citation2018, 11–12). According to Daniel Gutwein and Sophia Menache, the idea of the crusades is perpetuated in modern American society as a ‘manifestation of ongoing conflict’ at the heart of which is the narrative of a ‘campaign for a just cause, defending Western … values against … the barbarian East’ (Citation2002, 387). Adam Knobler (Citation2006) argues that in the nineteenth century the crusades became a way to romanticise and authorise warfare through the rhetoric of a historical true or just cause. He argues this was particularly significant at a time when ‘mechanisation made killing increasingly impersonal, [thus] it became all the more essential to justify its ‘rightness’ (2006, 324). The crusades are one of many ‘warrior brands’ or thematic clusters that have grown and compounded over centuries of militarism in medievalism (Lynch Citation2016, 144).

The crusader medievalism operating in the Prince of Thieves game is built on an image of a static Middle Ages that is a barbaric, unenlightened ‘Other’ to modernity. The Middle East is framed as the unenlightened Other to the advanced and enlightened West; in the case of the Gulf War, Saddam Hussein and Iraq were cast as a less-advanced enemy in a new techno-scientific discourse surrounding America’s superior techno-military capabilities. Haydock (Citation2009, 12–13) argues that war in the Middle East was marketed as ‘a long-delayed Enlightenment for a stubbornly “Middle” east’ in a way that collapsed the Middle Ages and Middle East, so that ‘wartime propaganda … skirted charges of racism and religious bias by changing race into religion and religion into time’. Haydock (Citation2009, 12–13) argues that this collapsing produced an idea of the ‘mid-evil’, wherein ‘Western demagoguery … combined medievalism and orientalism to construct a medieval Eastern enemy … to wage its war against the evils of an unregenerate past – note the widespread American pronunciation of the word (mid-evil)’.

Both the Prince of Thieves film and game begin with medieval outlaw hero Robin Hood as an English crusader escaping imprisonment in Jerusalem during the twelfth-century Third Crusade. As the setting of these opening scenes, the medieval crusades are established as a core historical framing mechanism for the texts, even though Robin soon leaves Jerusalem. The crusades are an important theme throughout the film, but are all but forgotten in the narrative of the game, especially as the character of Azeem is significantly minimised (see Watterson Citation2023, 57–8). Its connection to the film, however, and the prevalent tropes about the crusades and about Arab characters, still serve to connect the game’s medievalist representations to contemporary discourses about the Middle East (see Stock Citation2009, 99).

The use of the Robin Hood narrative further magnifies these rhetorics, as it features a figure who is popularly perceived as a paragon of anti-authoritarian outlawry, but whose narrative has, over time, also absorbed the paradox of an explicit positioning outside state structures, and a strict loyalty to a ‘good’ King. This allows Robin Hood media such as Prince of Thieves to critique systems of the state military control while also still bolstering their ultimate authority. Indeed, Leah Haught (Citation2022) argues that Robin Hood films often engender a sense of progressiveness through a Black, Muslim or non-European mentor or advisor figure who guides a white Robin’s critique of Western systems, but that this disguises the actual racism and Islamophobia in relegating the only non-white bodies to be tools supporting the construction of a timeless ‘Anglo-American identity that is … inherently heroic and unequivocally white’ (22). The crusades have become a very popular backdrop for Robin Hood depictions across media in the twentieth century, emerging out of the nineteenth century together with the gentrified once-yeoman version of Robin (Knight Citation2006). Most of the Robin Hood cinematic tradition includes a crusades plot device following the precedent set by the 1922 Douglas Fairbanks film and its use of the ‘Third Crusades as a speculum of the recent World War’ (Stock Citation2009, 104). Stock suggests that these representations of the crusades offer ‘distant mirrors’ (99) for contemporary issues, and indeed that Prince of Thieves also evokes the crusades as a distant mirror for a contemporaneous war: the first Gulf War (118). However, again, the game removes much of the complexity of the character of Azeem in the film, who there represents what Jack Shaheen (Citation2009) describes as a ‘reel good Arab’ – an Arab character with a heroic storyline as a dignified warrior, cast as a good Arab ally, like Kuwait. This plot device works as part of what Kathleen Biddick (Citation1998, 72–3) calls new Orientalism, ‘governed by a new imperialism that pits progressive Arabs against Islamic fundamentalists’. Robin Hood, a character remembered famously for defending the people against a corrupt and oppressive authority, lends further power to the good crusader narrative, and so much so that these meanings are inferred without extensive narrative representation. Simply by evoking the crusades setting in the beginning of the Prince of Thieves game, the developers draw on this strain of medievalism to enable a modern audience to engage in reductive modes of thought (see Weisl Citation2003, 3). Whereas the contemporary war in the Gulf was entangled with myriad political factors, the medieval crusades are imagined to offer simpler moral economies. That the hero-of-the-people Robin Hood was wrongfully imprisoned (for stealing bread) by Arabs in the Middle Ages, for example, offers a simple story of injustice. Drawing on a romantic evocation of the Middle Ages as a simpler time simultaneously with the Othering of a barbaric and ‘mid-evil’ enemy, medievalist video games can enable and even celebrate violence in their refusal to offer complex moral consideration.

The representation of the crusades in video games that employ militarised logics enhances the connection linking past and present conflicts between America and the Middle East. Popular media representations, including video games, reflect and shape this complicated legacy of the crusades (see, e.g. Phillips and Horswell Citation2018–Citation2022). The representation of the Middle East in video games, including as part of the military-entertainment complex, is not a new topic (see, e.g. Cox Citation2016; Hoglund Citation2008; Reichmuth and Werning Citation2006; Šisler Citation2008, Citation2014). My analysis here builds on the extensive literature around Orientalism and representations of Muslim and Islamic peoples in Western media (see, e.g. Gottschalk and Greenberg Citation2008). Vít Šisler has analysed the representation of the Arab or Muslim Other in Western video games specifically, including discussion in his article ‘Digital Arabs’ (Šisler Citation2008) of adventure or role-play games that produce a fantastical Middle East compared to action games (especially shooters) that render it a battleground for Western violence, always ‘schematizing Arabs and Muslims as enemies’ (214). Šisler argues that games often construct a ‘place without history’, colonially made static and historic to justify the intervention of Western modernity (207). Johan Höglund’s (Hoglund Citation2008) argues a range of modern war first-person shooter games that consistently reproduce the Middle East a space of ‘perpetual’ war. Oana-Alexandra Chirilă (Citation2021) analyses Assassin’s Creed as a case study for the Arabic Other and crusades in a historical video game, offering a close reading of the game’s narrative representations. Andrew B. Elliott and Mike Horswell (Citation2020) argue that crusades tropes, or ‘icons’, are isolated and reincorporated to ‘produce feelings of authenticity’ (150) in games. In his introduction to Playing the Crusades (Houghton Citation2021), Robert Houghton argues that though they hold significant educational potential, games often oversimplify the crusades into a binary Christian and Muslim conflict, dominated by violence and Eurocentric narratives. This extensive scholarship demonstrates the rhetorical power of crusader narratives in video games, especially the tropes and images replicated across AAA (Triple-A) and franchise games like Assassins Creed. With this context well established, the remainder of my article will thus focus on aspects of hypermediacy and militarised logistical thinking within that have been less examined in this context specifically in conjunction with medievalism in video games.

Video game and militarised logistical tendencies

The first Gulf War marked a shift not only in the enactment of war and violence, but the experience of war for its audiences back in America. Hugh Gusterson (Citation1991, 51) argues that the US Army General Schwarzkopf was able to claim to be

not in the business of killing [during the Gulf War] … largely because of the power of a system of representations which marginalizes the presence of the body in war, fetishizes machines and personalizes international conflicts while depersonalizing the people who die in them.

Video games and the military have a complicated, entwined history (see, e.g. Lenoir Citation2000). As Roger Stahl examines in his book Militainment Inc (Citation2010), the complexity of militarism in popular media captured by the new term ‘militainment’ is a concept with a long history. The concept of the military-industrial complex specifically refers to the relationship between a military and the industries that fund it, that is between capitalism and militarism. From this, the military-entertainment complex refers to the interrelationship between a military and entertainment media, particularly in the United States, and the ways in which popular media can operate as military propaganda, often due to the direct financial relationship between the military and media industries. James Der Derian then terms it a ‘military-industrial-media-entertainment-network’ (Citation2005, xi), but regardless of the exact arrangement of terminology, these few examples of a broad literature demonstrate that the saturation of US media with militarism, both overt and implicit, has deep roots and a significant impact on culture and society. Lenoir and Henry (Citation2005, 453) note that the military-industrial complex had been expected to fade with the end of the Cold War, but video games like America’s Army demonstrate that it has only reorganised and intensified.

Medievalist video games that centre their action on violence can be a particularly powerful instrument of this militarising discourse, as their setting makes them appear distant from modern warfare, enabling the embedded modern military values to thrive in discreet ways. Military procedural rhetoric in First Person Shooter (FPS) games and modern military games is often overt (see, e.g. Demers Citation2014; Draghici Citation2019; Hoglund Citation2008; Kontour Citation2011; Lin Citation2011; Reisner Citation2013; Schulzke Citation2013; Van Zwieten Citation2011), but the conceit of the distant past allows it to operate more covertly in other historical games too.

The key aspect of militarism in video games I explore here is the expectation of engagement through what Crogan (Citation2003) describes as a ‘logistical tendency to order and control contingent events’. That is, game processes largely employ a logistical schema based on a military use of modelling and simulation for the anticipation of future actions and thus expect players to interact in the (game) world through this scheme. This logistical tendency can structure perception in video game play and is about deeper modes of thought than the narrative representation. As Ted Friedman argues, games possess a ‘distinct power … to reorganize perception…. communicating not just specific ideas but structures of thought – whole ways of making sense of the world’ (Friedman Citation1999, 132–4).

Crogan draws on the work of Les Levidow and Kevin Robins’ Cyborg Worlds (Citation1989, 8), who explore the central role of the military guiding the development of infotech and influencing ‘entire models of social organisations and aspirations for the kind of society we consider possible, necessary or desirable’. Levidow and Robins describe the refitting of society into a cybernetic control model, wherein people are ‘human components’ (8) in a ‘world reduced to calculable, mechanical operations’ (159). This expands on Donna Haraway’s the concept of the Cyborg (Citation1990) as an ontology. Haraway (Citation1991, Citation1996) also argues that advanced technologies have become a central component of apparatuses of twentieth-century military strategies that operate through ‘military techno-scientific discourses’, revolving around ‘rapid massive deployment, concentrated control of information and communication, and high-intensity sub-nuclear precision weapons’ (Citation1991, 164). She argues that these apparatuses thus shape and (re)produce the discourses that surround the American military through a techno-scientific, or cyborg, epistemology (Citation1991). This control and application of information, also examined by Levidow and Robins, is the central process through which players must view and interact with game worlds. In a video game, Crogan argues, ‘information is the medium through which the gamer strives for control over the system – measured via achievement of the game goals’, and ‘knowledge … is conceivable as a product of information processing that maps out goal-directed pathways requiring decisions about how to proceed’ (Citation2003). The US military used computer-based war games to test predictive models for combat with exactly these logistical structures, even before the Gulf War (Lenoir and Henry Citation2005, 7–8). Even the relatively simple mechanics of Prince of Thieves demonstrate this system of militarised information processing, such as the organisation of resources in the game involves the collection and distribution of two types of item – health or attack, as I will explore further below.

The militarised logistical tendencies embedded in games are a different way of conceiving of people, actions, and spaces in the Middle Ages than the way these are experienced in other media representations such as film. Even if the game did involve the exact same plot as the film, the player’s engagement in these structures of thought still radically alters their experience of the narrative and thus of the past. In a video game such as Prince of Thieves, the experience of the past must translated into numerical data that affects the player-character’s ability either to survive (measured by depleting health points, or HP) or to fight (recorded in experience points, or XP). Even when the player is engaging in exploration of a past landscape, here Sherwood Forest, they are constantly expecting attack and are seeking three types of item (wealth, which is largely irrelevant in this game, or health related, or weaponry) which will assist them not in that moment but in future play. The logistical planning required to manage your character as a historical actor who is under constant threat shapes the historical knowledge the game produces. Games do render temporality malleable and enable experimentation with ideas about the past, but a game like Prince of Thieves also implicitly depends on and promotes modern militarised logistical thinking as the structure through which to organise this experimentation.

Depersonalisation and Technologies of War in Prince of Thieves

The most obvious resonance between Prince of Thieves and its historical context is the physical experience of viewing, or controlling, violence on a screen in the context of the ‘vision war’. The Gulf War was described as a technowar, partially because many of the soldiers deployed in the Gulf had been trained with simulation program SIMNET Close Combat Tactical Trainer system (Lenoir and Henry Citation2005, 13–18). As Der Derian summarises of Paul Virilio’s influential text Desert Screen, the Gulf War was marked by a ‘coeval emergence of mass media and an industrial army, where the capability to war without war manifest[ed] a parallel information market of propaganda, illusion, dissimulation’ (Der Derian Citation2005, viii). The conflict is also now described as the ‘vision war’, in reference to new vision technologies such as night vision, which Jose Vasquez (Citation2008, 87) argues had a significant impact on the depiction of the Gulf War. Vision technologies both served to make the ‘experience of war more intimate’ for those viewing it from their homes, and at the same time this techno perspective ‘generate[d] psychological distance between viewer and viewed’ (Vasquez Citation2008, 87; Robins and Levidow Citation1995, 120). Vasquez (Citation2008, 91) claims that ‘weapons equipped with visual technology … facilitate war crimes by dehumanizing the individuals being targeted and filtering the carnage these weapons produced’. The American public viewed the war as a media event, largely through the perspective of these vision technologies which were very similar to the view screen of video games (e.g. Hallin and Gitlin Citation1993; Stahl Citation2010, 3, 28; Muscati Citation2002, 131–2; Swalwell Citation2003)

Indeed, the images of the war produced through vision technologies were strikingly similar to the classic colouration of Gameboy devices, including that seen in Prince of Thieves (see ). The Gameboy colouration is immediately reminiscent of night vision technology and thus war in the Gulf, particularly as the Prince of Thieves player-character is immediately located as a western outsider in a hostile Middle East who must employ violence to protect his tortured friend. The hypermediacy of this technology, foregrounded in the player’s entire view of the history-play-space, is specific to games as animated texts with particular graphic design styles. The resonance this colouration produces is disguised by its incidental nature, as all Gameboy screens bear this colouration regardless of a game text’s connection to war and it is thus not a design choice. In historical context however, it would contribute to the mindset of a player who associates this visual style with video game play and watching war footage.

Figure 1. [Left] Screen capture of Prince of Thieve on Game Boy and [right] Photograph from Desert Storm coverage.

![Figure 1. [Left] Screen capture of Prince of Thieve on Game Boy and [right] Photograph from Desert Storm coverage.](/cms/asset/04c2d973-40a8-493a-947d-b58b394415ce/rrhi_a_2352318_f0001_oc.jpg)

An essential part of this new view of warfare was the depersonalisation of its victims, and even enactors. In Prince of Thieves, this operates simultaneously and paradoxically to the way that the narrative of war or motivation for warfare is personalised through the player’s embodied investment in a single heroic character, further reinforced by the use of the recognisable Robin Hood. The game constructs the player-character as the singular personality who is able to carry this storyline: a ‘chosen one’ with unique power. As the back of the game’s packaging states, ‘Now you are Robin Hood: Prince of ThievesTM, the only man with enough cunning, agility and courage … to free England from tyranny’, though you must ‘prove yourself worthy enough to lead’. The chosen one narrative is very common in video games as it provides motivation for the player as well as narrative justification for the considerable discrepancy in ability mechanics between the player-character and the other non-player-characters they must rescue or defeat. The story of the war in Prince of Thieves is also channelled through Robin’s personal quests to return to his home, defend his family land and threatened friends, and avenge his father’s death. Though offering a theoretically embodied experience of war in its narrative and player-character positioning, it is through its mechanics that it simultaneously marginalises the presence of the human body by shifting agency onto technology.

A core outcome of the military techno-scientific discourse employed during the Gulf War, according to Christina Masters (Citation2005, 113), was the ‘reconstitution and reproduction of American soldiers to fit into, operate and function in this ostensibly new information age’. Gusterson (Citation1991, 49) also notes that a remarkable distinctive element of Gulf War reporting was the depiction of bodies as ‘objects for mechanical enhancement’. It was not just that human bodies were inscribed ‘as the objects of power and knowledge’ (Masters, 124) but that technology itself becomes the subject of techno-scientific masculinity – the discourse had ‘fundamentally grafted military technology with agency and power’ (124). As Carol Cohn argues, a paradigm that holds weapons as the subjects have no linguistic space for human bodies, concerns, or crucially, human death (Citation1987, 711). Gusterson quotes a Newsweek article from 1991 (Thomas and Barry Citation1991, 38 quoted in Gusterson Citation1991, 49) that asked ‘who needs pilots when missiles have minds of their own?’ The portrayal of American soldiers by United States media focused on their possession of re-engineered, technologically enhanced bodies through their use of new war technologies, such as night vision goggles and thermal sights, chemical protection equipment, and drugs such as amphetamines (Thomas and Barry Citation1991, 38 quoted in Gusterson Citation1991, 49; Masters Citation2005, 113).

Simultaneously, video games inherited the mechanical concept from tabletop gaming wherein all bodies are understood as a series of numerical statistics that can be improved through experience or material objects. This type of system resonates perfectly with the way war reporting was fetishising technology as efficient agents of war. Through game mechanics, the body of Robin Hood in the Prince of Thieves game is moulded into a cyborg soldier appropriate to this contemporary discourse, and completely different than the Robin of the film. In the Standard Mode of gameplay, Robin’s pixilated body is static regardless of action in the game. Even if the player’s health is depleted from a total of 100 HP to 1 HP (the scale represents death at 0), Robin’s body appears the same and can perform the same actions as with full HP. The simplified and static nature of Robin’s body in a video game distances him from any real semblance of a biological human body.

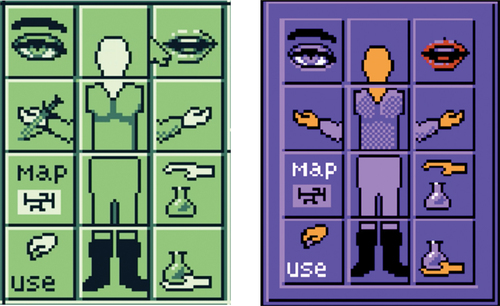

This is exemplified in the use of the paper doll equipment menu, where the player manages the resources of Robin and the other characters. It is shaded green (GB) or purple (NES), see . In GB, the body’s skin is also tinged green so even the tan colour used for Robin’s skin tone in Standard and Duel Modes is removed by the technological limitations of the console. The same ‘neutral’ body image is used to represent every character, so that they are de-individualised and the diversity of characters such as Azeem is further erased. The paper doll equipment screen has the character’s body depicted across a grid, broken into separate pieces wherein even the neutral body, with nothing equipped, already appears to be wearing body-armour-esque attire. The body is covered entirely except the face (and hands, which are then covered with a weapon when equipped). The player can collect superior weapons throughout the game, associating levelling up and advancement with increased destructive power.

By separating the eye and mouth images, to which the player drags objects for characters to either eat or inspect, the game removes and dissociates biological human needs from the weaponised body of the soldier Robin. Characters do not face limitations based on bodily needs (except death). For example, while you can eat in Prince of Thieves in order to gain health, you do not lose health if you never consume food. Robin is never seen to sleep, and there is no representation of the passage of time limiting when Robin can engage in action. Games that dispense with bodily functions do so because they are not exciting as ludic actions, and they are not perceived as useful or relevant to the character’s purpose (usually this purpose involves proficiency at violence), however in the context of the cyborg soldier’s media prominence, it conveys deeper incidental meanings. Prince of Thieves can thus imply that the ideal human body is one that is as efficient as a machine – essentially someone who is beyond human.

The management of food consumption as an HP mechanic demonstrates how these natural bodily needs are made into controllable actions in a particularly logistical schema. Players are encouraged to manage their food resources strategically depending on the health scores of the main characters and the (numerical) amount of HP that certain items restore. For example, some health potions restore 100 HP, while food restores smaller increments, but the maximum HP for that character remains a firm limit. An effective management strategy is to save potions until your health is very low, making their restorative value very high. The player can logistically manage the character’s consumption of resources in order to maximise HP as an individual or team. In the Melee Mode, allied NPCs that reach 0 HP during the battle will be revived at the end of the scene at 1 HP (excluding Peter in the catacombs), whereas the game is immediately over if the player-character reaches 0 HP. This encourages another pattern of resource management that privileges strategic management with concern for functionality rather than, for example, comfort or kindness. The player is taught to ignore fallen allies in combat scenes and focus only on maximising their own survival as the most logistical approach to succeeding in the game overall.

In both the Gulf War and in videogames, this techno-military discourse surrounding cyborg soldiers was also particularly gendered and racialized (Masters Citation2005, 112). As Tyson Pugh (Citation2010, 117–8) describes in his analysis of the film Robin and Marian, ‘[w]ar depends on the acceptance of masculine hierarchies’, that is, on the superiority of heroic masculinity, and often ‘lionize[s] martial masculinity as inherently triumphal’. The conscription of medievalist ideas about manhood and violence is ideal for modern military discourse, as the discourses of historical representation justify stereotypical gendered tropes that come under scrutiny when expressed in a contemporary context.

The cyborg soldier created by the player through a militarised logistical scheme is inherently superior to the enemies encountered throughout the gamescape. It must be technically possible for the player to defeat even the most difficult enemy, or the game can never be finished. Where the player enhances their abilities and equipment, the enemy NPCs are always inferior and simple bodies in Prince of Thieves. This resonates with the way that that subjecthood of soldiers in the Gulf was reconfigured through this modern militaristic vision so that successful performance of soldier masculinity depended on access to technologies. Crusades medievalism worked alongside a techno-military discourse that enabled a newly revitalised ‘Othering’ of enemies with less advanced technology. Masters (Citation2005, 124) describes how the language of the cyborg soldiers ‘[effects] a distance and disassociation from the other so that it can engage in practices of domination, subordination and subjugation’. This is the same behaviour often enacted in video games: the player can engage in fantasies of domination, subordination and subjugation due to the superiority ascribed to the player as cyborg soldier.

In both Standard and Melee Modes in Prince of Thieves, the bodies of the enemy soldiers are extremely simplistic, moving mechanically, with little to no characterisation beyond their identity as enemy soldiers. American Gulf War discourses collapsed the Iraqi enemy into the ‘character’ of Sadam Hussein, allowing war reporting to gloss over Iraqi bodies (Gusterson Citation1991, 49). Similarly, particularly in Robin’s escape from imprisonment as a crusader, all the guards Robin kills are collapsed into a singular evil persona of the enemy and devoid of their own personhood. The player can even wait in the catacombs of Jerusalem, in either green light or blue depending on platform, as a seemingly endless cohort of Arab guards spawn just beyond the field of vision and move to engage the player in combat. A very small number of these guards will leave a searchable corpse when killed, holding an object for the player’s (health or wealth) benefit, but most explode into a skeleton then disappear from the game world completely. In my own play-as-research, I was never able to exhaust this onslaught – the enemies would continue to spawn for as long as my Robin stayed in the catacombs, providing a limitless number of bodies for slaughter, almost all of which then vanish. There is no effective way measure the number of kills the player has performed, beyond keeping tally manually, as the XP rewards can vary. You, as the player, are not supposed to know how many faceless guards you have killed. René Glas (Citation2015, 32–36) examines the generic adversary as a well-established genre convention of action adventure games that draws on the broader trope of this expendable stock character. Glas (Citation2015, 42) agues that these characters are dehumanised to operate as indistinguishable enemy units through moral polarisation – hero is inherently good, thus their enemies must be unmistakably evil. The faceless Arab guards of the Prince of Thieves opening scenes are expected in this genre convention to be morally polarised and thus depersonalised, hence this is easily achieved in this case through their association with the barbaric or ‘mid-evil’ side of the crusades as a moral war.

The disappearing body of the faceless enemy soldiers in Prince of Thieves coincides with Gulf War media reporting in which body counts no longer had the impact they did in previous conflicts. The Vietnam War, as the first televised war, was characterised by the broadcasting of graphic violence in real time (Mandelbaum Citation1982, 157). Body counts were a primary measure of military success in the Vietnam War, and earlier the Korean War, but also sparked controversy, especially over increased violence produced by the need to measure ‘kills’ (Gartner and Myers Citation1995, 379–81, 388–89; Masters Citation2008, 163). Gulf War reporting shifted attention (and subjectivity) to technology and its effectiveness. Gusterson describes Gulf War reporting as defined by a ‘virtual absence of dead and wounded Iraqi bodies in public representations of a war where probably more than 100,000 Iraqis were killed in close proximity of about 1000 journalists in search of a story’ (50). The mechanism of XP in Prince of Thieves reflects these tensions – the numerical systems of XP and HP are technically based on a body count, that quantitatively measures and dictates your actions in the game, and yet this number is deliberately obscured. Neither the Arab nor castle guards in Prince of Thieves are treated as humans, but just as in Gulf War reporting, ‘soldiers were units, forces, assets, targets’ (Gusterson Citation1991, 49–51). The bodies of the soldiers almost always disappear, not even leaving a physical trace in the game world. When they leave a trace, it is only in the equipment they leave behind for the player to collect. Killing is thus sanitised and normalised.

The Prince of Thieves game world is defined by the neat boundaries of pixels, where it is much harder to produce the shadowy darkness that characterises the Prince of Thieves film. The film’s atmosphere and aesthetic of ‘dark, sinister, claustrophobic interiors’ (Morsberger and Morsberger Citation1998, 224) draw on an imagination of the Middle Ages as barbaric. The game world, conversely, is bright and colourful, the grey-browns of the film’s chapel battle replaced with bright red and green heraldry flags in a main hall. There is no representation of wounds or ailments on the bodies, and fatally wounded enemies simply disappear. The neat and controlled world of a video game is the metaphor that pervaded Gulf War media reporting, particularly with the vision technologies but also in the way the war space was sanitised. American violence was presented as clean, with an absence of bodies, whereas the depiction of Iraqi violence was rife with body mutilation (Gusterson Citation1991, 49–51). Americans were led to perceive the war as a ‘triumph not of one form of violence over another, but of decency over violence’ (Gusterson Citation1991, 52) through the depiction of American violence through technology efficient and effective. The medievalism of games like Prince of Thieves then conjure a vastly different vision of the period, which appears simultaneously more and less violent than representations in other media such as film.

The Prince of Thieves game also employs the medievalist genre expectation of personal violence, enabling it to simultaneously personalise and depersonalise war. The game does not directly feature the first-person perspective distance violence of the Gulf War, particularly the view-point of a projectile which is briefly and famously reflected in the film. Instead most of the violent action is melee – direct and personal, as is common for medieval video games. As Kim Wilkins (Citation2014, 121) notes, ‘there is a directness in our understanding of medieval violence … [that] signifies a bodily and brutal domination of objects and bodies in the medieval world and in medievalist digital space’. This personal violence seems at direct odds with the type of depersonalised, distance violence that dominated representations of the Gulf War. However, the player’s perspective on these violent encounters is still removed, usually seen from a birds-eye-view as though controlling pieces on a chess board, unlike the first-person violence of game genres like shooters. Furthermore, the Gulf War imaginary still has a powerful presence in the game through the sanitised neatness of video game violence in the context of the saturation of the Gulf War reporting with connections to videogaming. Therefore, regardless of the actual action being performed by characters in the game, the perspective of the player still produces a sense of distance from the consequences of violence and a birds-eye view of violence that corresponds with the particular visualisation of war accessible to the public in early 1990s America.

The game thus blends the idea of direct medieval violence with the sanitised safety of modern vision technology. This is designed to enable the player to feel emboldened by that ‘domination of objects and bodies’ both through medievalist direct violence, under the usual conceit that medievalist texts offer of a distant past, and through the sense of detachment the contemporary war rhetorics of technology enabled. The resonance of the idea of domination and violent control through both, albeit through seemingly opposite means, demonstrates how strategically well-paired medievalism and militainment are in games.

Conclusions

The mirroring of the Gulf War produced in Prince of Thieves can also be seen as a ‘Strategic Victory for Gameboy’. Games such as Prince of Thieves importantly reflect and (re)produce their historical context through more than just their narrative, as they are shaped so significantly by the complexity of gameplay and preceding history of video game development. Most of the elements discussed above play no role in the film: Kevin Costner was never intended to be a cyborg soldier, nor was the audience ever going to associate their viewing of the Middle Ages with seeing through night vision technology. These aspects are historically specific to the video game medium and the production of this game, and the transparency of these resonances in Gulf War America made it the perfect case study to illustrate the connections between medievalism and militainment in a text that many might dismiss as simplistic compared to modern war-themed video games.

By training players to interact with a medieval world through the same ludic systems they know from modern war simulation games, logistical schematic thinking is universalised and normalised. The rhetorical power of normalising militarised logistical thinking is significantly increased when it also coalesces with the potential of medievalism to ‘offer toxic ideologies a patina of tradition or timelessness that make them seem natural, correct, or inevitable’ (Kaufman and Sturtevant Citation2020, 5). In Prince of Thieves, this is compounded again by the specific identity of Robin Hood, an outlaw hero whose core narrative is violent actions undertaken for the greater good.

As a Robin Hood adaptation set in the twelfth century, the game’s medievalism is apparent and ever-present. Its militarism, however, is more subtle, hence the need for analytical work to provide this kind of relentless historicization. Though a game player is always aware of the technology through which they access a game’s story, most of the mechanics and structures discussed above are so normalised for video games that they often operate unseen. The player needs no reminder to identify the tropes of medievalism in the game due to their constant narrative foregrounding, but the way that the militarised mechanics of games underpin broader processes of thought in almost all game texts affords them potential invisibility unless highlighted and challenged.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tess Watterson

Dr. Tess Watterson is an early career researcher who specialises in medievalism, gender, and video games. She received her PhD from the University of Adelaide in 2023 for her thesis investigating witchcraft, gender, and persecution in medievalist fantasy video games. Her earlier research has been on medievalism and militainment in Robin Hood video games. Tess’s aim is to contribute to expanding pedagogical approaches for engaging with the past through experience and play.

References

- Biddick, Kathleen. 1998. The Shock of Medievalism. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Chirilă, Oana-Alexandra. 2021 “Show This Fool Knight What it Is to Have No Fear’: Freedom and Oppression in Assassins Creed (2007).” In Playing the Crusades: Engaging the Crusades, Volume Five, edited by Robert Houghton, 53–70. London: Routledge.

- Cohn, Carol. 1987. “Sex and Death in the Rational World of Defense Intellectuals.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 12 (4): 687–718. https://doi.org/10.1086/494362.

- Cox, Richard. 2016. “Crusades and Jihad: An Examination of Muslim Representation in Computer Strategy Games.” Honours diss., Middle Tennessee State University.

- Crogan, Patrick. 2003. “The Experience of Information in Computer Games.” Melbourne Digital Arts and Culture Conference, Melbourne: RMIT School of Applied Communication.

- Demers, David. 2014. “The Procedural Rhetoric of War: Ideology, Recruitment, and Training in Military Videogames”. Masters diss, Concordia University.

- Der Derian, James. 2005. “Preface.” In Desert Screen: War at the Speed of Light, vii–xiv. New York: Continuum.

- Draghici, Adalia Alexandra. 2019. “Remote War Fare, and Warfare Via Remote: Shifting Civil- Military Relations and Cultural Experiences of War in the U.S. from Vietnam to the Gulf.” PhD diss., Macquarie University.

- Elliott, Andrew B., and Mike Horswell. 2020. “Crusading Icons: Medievalism and Authenticity in Historical Digital Games.” In History in Games: Contingencies of an Authentic Past, edited by Martin Lorber and Felix Zimmermann, 137–155. Transcript Verlag

- Friedman, Ted. 1999. “Civilization and Its Discontents: Simulation, Subjectivity, and Space.” In On a Silver Platter: CD-ROMs and the Promises of a New Technology, edited by Greg Smith, 132–150. New York: New York University Press.

- Gartner, Scott Sigmund and Marissa, Edson Myers. 1995. “Body Counts and “Success” in the Vietnam and Korean Wars.” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History 25 (3): 377–395.

- Glas, René. 2015. “Of Heroes and Henchmen: The Conventions of Killing Generic Expendables in Digital Games.” In The Dark Side of Game Play : Controversial Issues in Playful Environments, edited by Torill Elvira Mortensen; Jonas Linderoth, and Ashley ML Brown, 33–49. New York: Routledge.

- Gottschalk, Peter, and Gabriel Greenberg. 2008. Islamophobia: Making Muslims the Enemy. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc.

- Gusterson, Hugh. 1991. “Nuclear War, the Gulf War, and the Disappearing Body.” Journal of Urban and Cultural Studies 2 (1): 51.

- Gutwein, Daniel, and Sophia Menache. 2002. “Just War, Crusade and Jihad: Conflicting Propaganda Strategies During the Gulf Crisis.” Revue belge de philologie et d’histoire Belgisch tijdschrift voor philologie en geschiedenis 80 (2): 388–389. https://doi.org/10.3406/rbph.2002.4622.

- Hallin, Daniel C. and Todd Gitlin. 1993. “Agon and Ritual: The Gulf War As Popular Culture and As Television Drama.” Political Communication 10: 411–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.1993.9963002.

- Haraway, Donna. 1990. “A Manifesto for Cyborgs: Science, Technology, and Socialist Feminism in the 1980s.” In Feminism/postmodernism, edited by Linda Nicholson. New York: Routledge.

- Haraway, Donna. 1991. Simians, Cyborgs, and Women. New York: Routledge.

- Haraway, Donna. 1996. Modest_Witness@Second_millennium. Female-Man_Meets_OncoMouse TM: Feminism and Technoscience. New York: Routledge.

- Haught, Leah. 2022. “Racialized Outcasts: Non-White Bodies and the Construction of the Outlaw-Hero in Modern Robin Hood Film.” In Negotiating Boundaries in Medieval Literature and Culture: Essays on Marginality, Difference, and Reading Practices in Honor of Thomas Hahn, edited by Valerie B. Johnson and Kara L. McShane, 21–48. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Haydock, Nickolas. 2009. “Introduction: “The Unseen Cross Upon the Breast”: Medievalism, Orientalism and Discontent.” In Hollywood in the Holy Land: Essays on Film Depictions of the Crusades and Christian-Muslim Clashes, edited by Nickolas Haydock and E. L. Risden, 1–30. Jefferson: McFarland & Company Inc. Publishers.

- Hoglund, Johan. 2008. “Electronic Empire: Orientalism Revisited in the Military Shooter.” The International Journal of Computer Game Research 8 (1). http://gamestudies.org/0801/articles/hoeglund.

- Horswell, Mike. 2018. The Rise and Fall of British Crusader Medievalism, C. 1825-1945. New York: Routledge.

- Horswell, Mike. 2022. “Historicising Assassin’s Creed (2007): Crusader Medievalism, Historiography, and Digital Games for the Classroom.” In Teaching the Middle Ages Through Modern Games: Using, Modding and Creating Games for Education and Impact, edited by Robert Houghton, 47–68. Berlin: de Gruyter.

- Houghton, Robert. 2021. “Introduction: Crusades and Crusading in Modern Games.” In Playing the Crusades: Engaging the Crusades, Volume Five, edited by Robert Houghton, 1–11. London: Routledge.

- Kaufman, Amy and Paul, Sturtevant. 2020. Devil’s Historians: How Modern Extremists Abuse the Medieval Past. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Kellner, Douglas. 1992. The Persian Gulf TV War. New York: Routledge.

- Kline, Daniel T. 2014. “Introduction: ‘All Your History Are Belong to Us’: Digital Gaming Re-Imagines the Middle Ages.” In Digital Gaming Re-Imagines the Middle Ages, edited by Daniel T. Kline, 1–14. New York: Routledge.

- Knight, Stephen. 2006. “Robin Hood and the Crusades: When and Why Did the Longbowman of the People Mount Up Like a Lord?” Florilegium 23 (1): 201–222. https://doi.org/10.3138/flor.23.012.

- Knobler, Adam. 2006. “Holy Wars, Empires, and the Portability of the Past: The Modern Uses of Medieval Crusades.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 48 (2): 293–325. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0010417506000120.

- Kontour, Kyle. 2011. “War, Masculinity, and Gaming in the Military Entertainment Complex: A Case Study of Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare.” PhD diss., University of Colorado.

- LaMay, Craig, Martha FitzSimon, and Jeanne Sahadi, eds. 1991. The Media at War: The Press and the Persian Gulf Conflict: A Gannett Foundation Report. New York: Gannett Foundation Media Centre.

- Lenoir, Tim. 2000. “All but War Is Simulation: The Military-Entertainment Complex.” Configurations 8 (3): 289–335. https://doi.org/10.1353/con.2000.0022.

- Lenoir, Tim, and Lowood Henry. 2005. “Theaters of War: The Military-Entertainment Complex.” In Collection - Laboratory - Theater : Scenes of Knowledge in the 17th Century, edited by Jan Lazardzig; Helmar Schramm, and Ludger Schwarte, 427–56. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter Publishers.

- Levidow, Les, and Robins Kevin. 1989. “Towards a Military Information Society?” In Cyborg Worlds: The Military Information Society, edited by Les Levidow and Kevin Robins, 159–177. London: Free Association Books.

- Lin, Philip. 2011. “Mediating Conflicts: A Study of the War-Themed First-Person-Shooter (FPS) Gamers.” The 3rd Global Conference on Videogame Cultures and the Future of Interactive Entertainment, Mansfield College, Oxford.

- Lynch, Andrew. 2016. “Medievalism and the Ideology of War.” In The Cambridge Companion to Medievalism, edited by Louise D’Arcens, 135-150. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mandelbaum, Michael.1982. “Vietnam: The Television War.” Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 111 (4): 157–169.

- Masters, Cristina. 2005. “Bodies of Technology.” International Feminist Journal of Politics 7 (1): 112–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461674042000324718.

- Masters, Cristina. 2008. “Body Counts: Reading Moments of US Militarism from the Margins of International Politics.” PhD diss., York University.

- Morsberger, Katherine M., and Robert E. Morsberger. 1998. “Robin Hood on Film: Can We Ever ‘Make Them Like They Used To’?” In Playing Robin Hood: The Legend As Performance in Five Centuries, edited by Lois Potter, 205–231. Newark: University of Delaware Press.

- Muscati, Sina Ali. 2002. “Arab/Muslim ‘Otherness’: The Role of Racial Constructions in the Gulf War and the Continuing Crisis with Iraq.” Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs 22 (1): 131–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/13602000220124872.

- Pugh, Tyson. 2010. “Queer Crusading, Military Masculinity, and Allegories of Vietnam in Richard Lester’s Robin and Marian.” Studies in Medievalism XIX: Defining Neomedievalism(s) (19) : 114–134.

- Reichmuth, Philipp, and Stephan. Werning. 2006. “Pixel Pashas, Digital Djinns.” ISIM review 18:46–47.

- Reisner, Clemens. 2013. ““The Reality Behind it All Is Very True”: Call of Duty: Black Ops and the Remeberance of the Cold War.” In Playing with the Past: Digital Games and the Simulation of History, edited by Matthew Wilhelm Kapell and Andrew B.R. Elliott, 247–260. New York: Bloomsbury.

- Richards, Jeffrey. 1999. “From Christianity to Paganism: The New Middle Ages and the Values of ‘Medieval’ Masculinity.” Journal for Cultural Research 3 (2): 213–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/14797589909367162.

- Robins, Kevin and Les Levidow. 1995. “Socializing the Cyborg Self: The Gulf War and Beyond’.” In The Cyborg Handbook, edited by C. H. Gray. New York: Routledge.

- Robinson, Carol L. 2008. “An Introduction to Medievalist Video Games.” In Studies in Medievalism XVI: Medievalism in Technology Old and New, edited by Karl Fugelso and Carol L. Robinson, 16: 123-124.

- Romera, César San Nicolás, Miguel Ángel Nicolás Ojeda, and Josefa Ros Velasco. 2016. “Video Games Set in the Middle Ages: Time Spans, Plots, and Genres.” Games and Culture 13 (5): 521–542. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412015627068.

- Schulzke, Marcus. 2013. “Serving in the Virtual Army: Military Games and the Civil-Military Divide.” Journal of Applied Security Research 8 (2): 246–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361610.2013.765342.

- Servitje, Lorenzo. 2014. “Digital Mortification of Literary Flesh: Computational Logistics and Violences of Remediation in Visceral Games’ Dante’s Inferno.” Games and Culture 9 (5): 368–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412014543948.

- Shaheen, Jack. 2009. Reel Bad Arabs: How Hollywood Vilifies a People. Massachusetts: Olive Branch Press.

- Šisler, Vít. 2008. “Digital Arabs: Representation in Video Games.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 11 (2): 203–220. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549407088333.

- Šisler, Vít 2014. “From Kuma\war to Quraish: Representation of Islam in Arab and American Video Games.” In Playing with Religion in Digital Games, edited by Heidi A. Campbell and Grieve, Gregory Price, 109–133. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Skottki, Kristin. 2018. “The Dead, the Revived and the Recreated Pasts: ‘Structural amnesia’ in Representations of Crusade History.” In Perceptions of the Crusades from the Nineteenth to the Twenty-First Century: Engaging the Crusades, Volume One, edited by Mike Horswell and Jonathan Phillips, 107–133. London: Routledge.

- Stahl, Roger. 2010. Militainment Inc. War, Media and Popular Culture. New York: Routledge.

- Stock, Lorraine Kochanske. 2009. “Now Starring in the Third Crusade: Depictions of Richard I and Saladin in Films and Television Series.” In Hollywood in the Holy Land: Essays on Film Depictions of the Crusades and Christian-Muslim Clashes, edited by Nickolas Haydock and E. L. Risden, 93–120. Jefferson: McFarland & Company Inc. Publishers.

- Swalwell, Melanie. 2003. “‘This isn’t a Computer Game You know!’: Revisiting the Computer Games/Televised War Analogy.” In Level Up: Digital Games Research Conference, and Published in the Proceedings, edited by Marinka Copier and Joost Raessens. Netherlands: Universiteit Utrecht/DIGRA.

- Thomas, E. and J. Barry. 1991, February. “War’s New Science.” Newsweek. 18: 38.

- Van Zwieten, Martijn. 2011. “Danger Close: Contesting Ideologies and Contemporary Military Conflict in First-Person Shooters.” DiGRA Conference: Think Design Play. Utrecht: Utrecht School of the Arts.

- Vasquez, Jose N. 2008. “Seeing Green: Visual Technology, Virtual Reality, and the Experience of War.” Social Analysis: The International Journal of Social and Cultural Practice 52 (2): 87. https://doi.org/10.3167/sa.2008.520206.

- Watterson, Tess. 2023. “‘Now You Are Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves™’: Intermedial Medievalism.” Adaptation 16 (1): 50–62. https://doi.org/10.1093/adaptation/apad002.

- Weisl, Angela Jane. 2003. Persistence of Medievalism: Narrative Adventures in Public Discourse. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Wilkins, Kim. 2014. “Awesome Cleavage: Gendered Body in World of Warcraft”.” In Digital Gaming Re-Imagines the Middle Ages, edited by Daniel T. Kline, 119–130. New York: Routledge.