Has a crisis point been reached in what is currently taken as psychotherapeutic knowledge? There are, for example, an ever-increasing number of continuous professional development (CPD) courses offering to help therapists with everything from abandonment to maternal deprivation. Could such CPD, which might be typical of psychotherapy trainings, that assumes some form of diagnosis and treatment, be usefully challenged if we were to consider that:

● to start with theory can be a form of violence?

● a primacy should be given to practice?

● a reliance on empirical research get’s us starting from the wrong place?

From a critical existential-analytic psychotherapeutic perspective, the answer to all three of these assertions is ‘yes’. This perspective, therefore, may be fundamentally different from what psychological therapists are increasingly purporting to do, though there may be less divergence, in albeit a decreasing number of cases, with what is actually their practice. (It may also be that this newly created generic term of ‘psychological therapist’ is as different to the various ‘therapists’ it collectively now represents as, it will shortly be considered, ‘phenomenological research’ is from ‘phenomenology’).

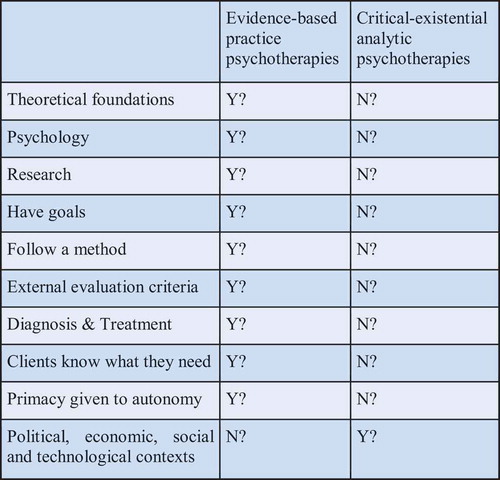

This fundamentally different approach is explored more in a forthcoming publication (Loewenthal Citation2020a) where the aspects listed in are considered further. However, now, rather than comparing, as in the book, existentialism with post-existentialism, I compare evidence-based psychotherapies with critical existential-analytic psychotherapies:

Figure 1. A comparison of aspects of evidence-based psychotherapies with critical existential-analytic psychotherapies.

The above figure indicates the fundamental different potential implications of the approach advocated here. Space does not permit an examination of each aspect; instead, consideration is given here to start to explore what might be meant by ‘critical existential-analytic psychotherapies’? In one sense they are an attempt to be clearer with another person about his or her meanings and experiences. However, doesn’t the therapist then have to work with each client’s unique, though culturally influenced, language and interpretation? Further, whilst for the therapist there are such questions as those of judgement (and timing) isn’t psychotherapy less about acquiring new skills and more attempting to be clearer how our clients and we are in our beings?

To take each of the terms of ‘critical existential-analytic psychotherapies’: there are several influences on the notion of ‘critical’ (Loewenthal, Citation2015a). Psychotherapists could be critical of their theories (and indeed of theory itself). Unfortunately, when it comes to psychotherapy trainings, they usually appear to be based on their various gurus each claiming to have the only truth and it is rare for any of the hundreds of them to encourage being questioned, yet evidence-based research is not necessarily the panacea. It also appears rare for such trainings to have substantial, if sometimes any, critical concerns, for example, in terms of the social consequences of psychotherapy, how psychotherapy constructs sexual difference and/or is used to promote class and national interests, the politics of psychotherapeutic truths, etc. (Loewenthal & Campbell, Citation1998). A further sense of ‘critical’ comes from the Frankfurt School of critical theory (see Gaitanidis, Citation2015), which can also be seen more broadly, and sometimes alternatively, in terms of the social, economic and ideological conditions which can cause people’s wretchedness. The lack of such explorations is all too common in the various therapeutic trainings which appear not to consider they have a responsibility to educate trainees in such influences; instead, many can be seen as only considering psychotherapy assisting in terms of perhaps a liberal type of ‘hand up rather than hand out’ New Deal that in 1933 − 39 was Roosevelt’s response to what was economically (and could have psychologically been) named the ‘Great Depression’.

Regarding ‘existential’: Aspects such as being in despair or anxious one are going to die are often taken as existential concerns but surely that shouldn’t mean this can only be expressed and explored in what might be seen as at best some nostalgic existential 1950s/60s self-centred modernistic straight jacket! Thus, as has been argued elsewhere (Loewenthal, Citation2017); existential psychotherapy and counselling have become stuck and are less likely to have the ‘astonishing and ‘changing’ (J. Heaton, Citation1990) essences of existentialism and far more likely to be apolitical.

Hence, the suggestion of the notion ‘post-existentialism’ (Loewenthal, Citation2011) where the implications of thinkers such as Heidegger and Merleau-Ponty might be considered, but together with other possibilities including those that argue for the privileging not just of autonomy but being subject-to, for example, ethics, language, writing and an unconscious through, for example, Levinas, Lacan, Derrida and Freud.

Indeed in referring to Freud, the next term in our editorial title is ‘analytic’. This not only refers to existential practices claiming that they are also ‘analytic’ but psychoanalysis itself. What is regarded as important here is that existential concerns come first: they are privileged over psychoanalytic ones. There are also such questions as whose psychoanalysis, to what extent, and how? As well as sometimes difficult questions as to when is psychoanalysis unnecessary and a violence and when are we at best sanitising psychoanalysis because of our own defences as psychotherapists?

The last term in our title is ‘psychotherapies’. Here we are influenced by, for example, Plato’s concern that whilst science and technology are important we have to be continually reminded that therapeia is primarily about the resources of the human soul (Cushman, Citation2001). Thus, whilst therapy involves a conversation that can’t be had elsewhere, it is nevertheless a conversation and as Gadamer (Citation2013) points out: you can’t plan a conversation. Also, the term ‘psychotherapies’ is deliberately given in the plural as it is acknowledged there can be many different ways of privileging the implications of the assertions at the start of this editorial. Such perspectives have very different assumptions about practice, theory and research. Again to consider each of these in turn.

It has been suggested that Freud, Klein, et al. (J. Heaton, Citation2013; Loewenthal, Citation2011; Wittgenstein, Citation1998) tended more to discovering practices from which they subsequently tried to construct theories. Yet most trainings expect their resulting therapists to start from a theoretical place and apply knowledge derived increasingly, and more often exclusively, from empirical research. Thus, such CPD events as working with abandonment may be unhelpful if considered as an application of theory.

Whilst we are interested in theory not least for the possibilities it can open up, it is different if it comes to mind as implications but not if we start with it as applications. Merleau-Ponty’s (Citation1962) notion of phenomenology being about what emerges in the in-between can be helpful here. Further, if one also accepts that therapeutic knowledge is more about a tacit dimension (Polyani, Citation1966) which cannot be so much taught and learnt but sometimes might be imparted and acquired, a more sceptical (J. M. Heaton, Citation1993) notion of theory is considered healthier. Nevertheless, theories are very important in being able to open up different possibilities for our practices. For example, if one were to consider the job description of a psychotherapist through what has been attributed to Ricouer (Citation1965) as the ‘hermeneutics of suspicion’, this opens up possibilities for the psychotherapist to interpret what could be seen as cover stories that imprison our clients sexually, morally and through capitalism with the help of the likes of Freud, Nietzsche and Marx. To which we might now add therapeutic imprisonment by the state (Loewenthal et al., Citation2020).

Overall, hasn’t research in the psychotherapies moved from any attempt at thoughtful practice to previously being theory driven to currently being based on false notions of evidence-based practice (see, for example, the introductory debate in Loewenthal & Avdi, Citation2019)? The above would suggest a different approach to psychotherapy to that currently purported by those that wish to be totally reliant on so-called evidence-based practice. To give an example (which is explored further in several articles of this special issue), a more liberally minded evidence-based practitioner might be interested in what is termed ‘phenomenological research’; but, isn’t this a misnomer?

For those who privilege practice, phenomenology has provided its own theoretical implications. Leaving aside a question of whose phenomenology, for example, Husserl’s, Heidegger’s, Merleau-Ponty’s, Levinas’s, or Montaigne’s, etc., in our current more ‘evidence-based’ era, phenomenology is primarily considered through what it is argued is a misnomer ‘phenomenological research’. For example, the descriptive phenomenological psychological method (Giorgi & Giorgi, Citation2017), Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (Smith et al., Citation2009), Heuristics (Moustakas, Citation1990), etc. Here, various individual accounts are through these different techniques, brought together in an attempt to find common phenomena. Yet even if this is possible, can it really help other psychotherapists? Even more importantly, this psychologising of phenomenology, doesn’t it unhelpfully takes away from the original notions of phenomenology: surely phenomenology is research? (Loewenthal, Citation2015b). Yet it is currently increasingly unlikely that students of the psychological therapies will consider an aspect of interest being explored/researched in the style of, for example, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Montaigne, Heidegger, etc. Perhaps even more calamitous is that the phenomenological description arising from a single case study, which we might call psychotherapy’s traditional approach to research stemming from phusis/physis (it’s the natural and what comes out itself), is no longer allowed. This is because trending consumer legislation means that case studies can no longer just be anonymised, but instead, the client/patient has to give written consent for the actual article, beyond what is common for ethics approval and for unspecified publication. Hence, the client/patient has to read the to be published account of his/her therapist and agree that it has been appropriately anonymised. In actuality, this means that most previously trained psychotherapists are unlikely to consider it ethical or therapeutically helpful for their client/patient. Thus, the lifeblood of psychotherapy has lost being able to show publicly what has been its own way of doing research. It has been taken away and driven underground. There is an argument that ‘effective’ psychotherapy should be on the edges of our culture; but, we have then to accept being far less able directly to influence it.

A further related catastrophe is the current fashion in psychotherapeutic research which has moved from considering the implications, for example, of what certain existential philosophies might have made of a particular researcher’s question. Rather, theory is primarily used to justify concepts (increasingly as technologies) by showing how its application can be empirically evidenced. In fact, it would increasingly appear that the tail is wagging the dog, in that only those theoretical ideas that would appear to be able to be researched, usually more quantitatively than qualitatively, will be considered.

It is argued that in this way, questions of practices, theories and research have been increasingly thrown out of alignment, with what might otherwise be taken as the nature of therapeutic knowledge including its tacit dimensions, despite some attempts elsewhere through the likes of Lave (Citation1991) and Lave and Wenger (Citation1991) to return to it. What if anything can be done? One possibility is provided by this special issue, but first before introducing the papers, a brief word as to how this particular publication was initiated.

This special issue came about because of an unprecedented, in the previous 21 years of the European Journal of Psychotherapy and Counselling, processing crisis. As a result, I very much brought forward this project which otherwise might have become after a few years gestation a book. Instead, my colleagues and doctoral and masters students, all who are involved in our critical existential-analytic psychotherapy training (SAFPAC.co.uk), immediately rallied round. Consequently, my apologies for being so self-centred. It hopefully hasn’t been perceived as my usual practice over the last 21 years and won’t be in the future. My thanks also to our three published respondents and especially the ejpc editorial team: Evrinomy Avdi, Anastasios Gaitanidis, Jay Watts and David Winter and to our departing Assistant Editor Laura Scott-Rosales as their assistance with this special issue went far beyond their usual ‘beyond the call of duty’! Further thanks for their invaluable assistance with this special issue to Gauri Beecroft, Christian Buckland, Linda Finlay, Sacha Lawrence, Seth Osborne, and Sally Parsloe.

I have tried, with particular reference to existentialism and psychoanalysis, to outline here some ways in which psychotherapies might be able to move away from the crisis mainly caused by what is currently wrongly being taken in terms of ‘evidence based practice’ as the nature of psychotherapeutic knowledge. In summary, I have suggested instead: a primacy being given to practice, considering theories having implications rather than applications, and privileging thoughtfulness with notions of research being seen more as cultural practices. I would now like to introduce the accompanying papers of this special issue.

Our first article is by Onel Brooks, entitled, Looking Like a Foreigner: foreignness, conformity and compliance in psychoanalysis. As one reviewer commented “this is a stimulating paper, I found it of particular interest that it appeared to challenge the notion of psychoanalysis as a science, therefore the analyst having superiority over the analysand and others …. The personal examples of foreignness were illuminating, especially in the light of one being a client example and one being from the author’s, personal, lived experience”.

The next paper is Language as Gesture in Merleau-Ponty: Some implications for method in therapeutic practice and research by Julia Cayne. As another reviewer commented, ‘a very interesting and well thought through piece … . I really enjoyed your interpretations of in-between Lacan and Merleau-Ponty … [and] the parallels between Merleau-Ponty’s and Winnicott’s notions of the “spontaneous gesture”’.

This is followed by The private life of meaning – some implications for psychotherapy and psychotherapeutic research by Anthony McSherry (as lead author), Del Loewenthal and Julia Cayne. This paper explores questions arising from a study concerning how mental health nurses are therapeutic. As a reviewer commented, ‘I found it extremely interesting and refreshing to read about the author’s reflections … and this relates to phenomenology and truthfulness. I specifically enjoyed the author’s openness and the exploration surrounding dispelling one’s own assumptions and beliefs in order to reduce the possibilities of closing something important down and for people to sit with the uncomfortable feelings attached to not knowing’.

Regarding our next paper by Elizabeth Nicholl (as lead author), Del Loewenthal and James Davies Finding my voice: Telling stories with heuristic self-search inquiry, a reviewer has commented: ‘it is well written. a particular strength of the paper is in its innovative methodology, as well as the fact that it provides an engaging and experience-near account of the first author’s transformative and later painful experience of disclosing her diagnosis in therapy during her psychotherapy training’.

Our fifth paper, When working in a youth service, how do therapists experience humour with their clients?, by Patricia Talens has been described as ‘well written and fascinating’. The reviewer further comments ‘this article begins with a thoughtful story in literature regarding therapeutic practice and follows . [with an] . exploration of how the author conducted their research and ends with an honest critique.’

Our final paper before introducing the published respondents is What Gets in the Way of Working with Clients Who Have Been Sexually Abused? By Yana Trichkova (as lead author), Del Loewenthal, Betty Bertrand and Catherine Altson. This paper is further described by a reviewer as one that ‘presents a study using heuristic inquiry which was stimulated by the primary researcher’s experiences of working with clients who have been sexually abused’. In fact our first published respondent described it as

That first respondent is Manu Bazzano who might be seen as coming from a more existential perspective. In his paper Immaculate Conceptions Manu considers the series of papers both provide a refreshing ambivalence at the heart of psychoanalysis and are effective in opening explorations to post qualitative investigations.

Our second respondent is Laura Chernaik who might be seen as coming from a more psychoanalytic perspective. Her review is entitled The Pictures You Paint in the Stories You Tell, A Response. Laura is interested in ‘intention’ and argues for approaching critique heterotopically, with an emphasis on other worlds and the relation of these to subjectivity and the unconscious.

Our third and final published response is from Steen Halling who might be seen as coming from a more phenomenological perspective. Steen’s review is entitled Reflections on the Tensions between Openness and Method in Experientially Oriented Research and Psychotherapy. Here, Steen addresses issues around the challenges of using phenomenological methods and studying phenomena systematically while retaining an attitude of humility.

Of course there are very likely to be those who would insist on the approaches influenced by the assumptions given in this editorial should first be researched as to whether they are evidence-based practices; but, that depends on what one takes to be the nature of psychotherapeutic knowledge!

References

- Cushman, R. (2001). Therapeia: Plato’s conception of philosophy (new ed.). Transaction.

- Gadamer, H.-G. (2013). Truth and method. Bloomsbury Academic.

- Gaitanidis, A. (2015). Chapter 6: Critical theory and psychotherapy. In D. Loewenthal (Ed.), Critical psychotherapy, psychoanalysis and counselling: Implications for practice (pp. 95–107). Routledge.

- Giorgi, M., & Giorgi, B. (2017). Phenomenological psychology. In Willig, & Rogers (Ed.), The sage handbook of qualitative research in psychology (pp. 165–178). Sage.

- Heaton, J. (1990). What is existential analysis? Journal of the Society for Existential Analysis, 1(1), 2–6.

- Heaton, J. (2013). The talking cure: Wittgenstein on language as bewitchment and clarity. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Heaton, J. M. (1993). The sceptical tradition in psychotherapy. In L. Spurling (Ed.), From the words of my mouth: Tradition in psychotherapy (pp. 106–131). Routledge.

- Lave, J. (1991). Situated learning in communities of practice. In L. B. Resnick, J. M. Levine, & D. Teasley (Eds.), Perspectives on socially shared cognition (pp. 63–82). American Psychological Association.

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

- Loewenthal, D. (2011). Post-existentialism and the psychological therapies: Towards a therapy without foundations. Karnac.

- Loewenthal, D. (2015a). Critical psychotherapy, psychoanalysis and counselling: Implications for practice. Routledge.

- Loewenthal, D. (2015b). What have current notions of psychotherapeutic research to do with truth, justice and thoughtful practice? European Journal of Psychotherapy & Counselling, 17(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642537.2014.1003457

- Loewenthal, D. (2017). Existential psychotherapy and counselling after postmodernism: The selected works of Del Loewenthal. Routledge World Library of Mental Health.

- Loewenthal, D. (2020a). ‘ Chapter 9 ‘ Therapy as cultural, politically influenced practice’. In D. Loewenthal & S. Shamdasani (Eds.), Towards transcultural histories of psychotherapies (pp. 134–148). Routledge.

- Loewenthal, D. (2020a). Existential therapeutic practice after post-modernism. In M. Bazzano (Ed.), Re-visioning existential therapy: Counter-traditional perspectives. Routledge.

- Loewenthal, D., & Avdi, E. (2019). Introduction. In Loewenthal, & Avdi (Ed.), Developments in psychotherapeutic qualitative research (pp. 1–11). Routledge.

- Loewenthal, D., & Campbell, R. (1998). The contest of European meaning. European Journal of Psychotherapy, Counselling and Health, 1(2), 177–181.

- Loewenthal, D., Ness, O., & Hardy, B. (2020). Beyond the Therapeutic State. Routledge.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. (1962). The phenomenology of perception. Routledge.

- Moustakas, C. E. (1990). Heuristic research: Design, methodology, and applications. Sage Publications, Inc.

- Polyani, M. (1966). The tacit dimension. Doubleday.

- Ricouer, P. (1965). History and truth. Northwestern University Press.

- Smith, J., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative phenomenological analysis. Sage.

- Wittgenstein, L. (1998). Culture and value ( P. Winch, Trans.; 2nd. ed.), G.H. von Right, in collaboration with Heikki Nyman, revised by Alios Pichler. Oxford.