ABSTRACT

The taboo of therapist self-disclosure and literature addressing disclosure and disability issues from a psychodynamic perspective is explored. Research on disclosure decisions among physically impaired practitioners is limited. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis qualitative research methodology was employed to understand the lived experience of psychodynamic practitioners with sight impairment to understand disclosure decision-making processes in a therapeutic setting. Six participants self-identified as sight impaired psychodynamic practitioners and were interviewed using a semi-structured questionnaire. Findings showed that the experience of working as a practitioner with sight impairment is a tenacious endeavour, requiring high levels of self-awareness and determination in navigating the minefield of self-disclosure, daring to be seen by others, holding the patient’s need to be seen and journeying through loss and acceptance of the changing self. Results showed that there is an inverse relationship between likelihood to self-disclose sight impairment and the extent to which practitioners work with unconscious process and transference. Ultimately, the capacity to reclaim disavowed parts of the self, defined therapists’ ability to make therapeutic disclosure decisions. Suggestions for future research, clinical and ethical implications are provided plus recommendations for impaired practitioners and those who work with difference.

ABSTRAKT

Das Tabu der Therapeuten-Selbstoffenbarung und Literatur, die sich mit Offenlegungs- und Behinderungsproblemen aus einer psychodynamischen Perspektive befasst, wird untersucht. Die Forschung zu Offenlegungsentscheidungen bei körperlich beeinträchtigten Praktikern ist begrenzt. Die qualitative Forschungsmethodik der interpretativen phänomenologischen Analyse wurde eingesetzt, um die gelebte Erfahrung psychodynamischer Praktiker mit Sehbehinderung zu verstehen, um Offenlegungsentscheidungsprozesse in einem therapeutischen Umfeld zu verstehen. Sechs Teilnehmer, die sich selbst als psychodynamische Praktiker mit Sehbehinderung identifizierten, wurden mit einem halbstrukturierten Fragebogen befragt. Die Ergebnisse zeigten, dass die Erfahrung, als Arzt mit Sehbehinderung zu arbeiten, ein zähes Unterfangen ist, das ein hohes Maß an Selbstbewusstsein und Entschlossenheit erfordert, um durch das Minenfeld der Selbstoffenbarung zu navigieren, sich zu trauen, von anderen gesehen zu werden und das Bedürfnis des Patienten, gesehen zu werden, zu berücksichtigen und Reisen durch Verlust und Akzeptanz des sich verändernden Selbst. Die Ergebnisse zeigten, dass es eine umgekehrte Beziehung zwischen der Wahrscheinlichkeit, eine Sehbehinderung zu offenbaren, und dem Ausmaß gibt, in dem Praktizierende mit unbewussten Prozessen und Übertragungen arbeiten. Letztendlich definierte die Fähigkeit, verleugnete Teile des Selbst zurückzugewinnen, die Fähigkeit von Therapeuten, Entscheidungen zur therapeutischen Offenlegung zu treffen. Es werden Vorschläge für zukünftige Forschung, klinische und ethische Implikationen sowie Empfehlungen für behinderte Praktiker und diejenigen, die mit Unterschieden arbeiten, gegeben.

RESUMEN

Se explora el tabú de la autorevelación del terapeuta y la literatura que aborda la divulgación y los problemas de discapacidad desde una perspectiva psicodinámica. La investigación sobre las decisiones de divulgación entre los profesionales con discapacidad física es limitada. Se empleó la metodología de investigación cualitativa del Análisis Fenomenológico Interpretativo para comprender la experiencia vivida de los profesionales psicodinámicos con discapacidad visual para comprender los procesos de toma de decisiones de divulgación en un entorno terapéutico. Seis participantes autoidentificados como profesionales psicodinámicos con discapacidad visual fueron entrevistados mediante un cuestionario semiestructurado. Los hallazgos mostraron que la experiencia de trabajar como practicante con discapacidad visual es un esfuerzo tenaz, que requiere altos niveles de autoconciencia y determinación para navegar por el campo minado de la auto-revelación, atreverse a ser visto por otros, mantener la necesidad del paciente de ser visto y viajar a través de la pérdida y la aceptación del yo cambiante. Los resultados mostraron que existe una relación inversa entre la probabilidad de auto-revelar el deterioro de la vista y la medida en que los profesionales trabajan con el proceso inconsciente y la transferencia. En última instancia, la capacidad de reclamar partes desautorizadas del yo, definió la capacidad de los terapeutas para tomar decisiones de divulgación terapéutica. Se proporcionan sugerencias para futuras investigaciones, implicaciones clínicas y éticas, además de recomendaciones para profesionales con discapacidad y aquellos que trabajan con diferencia.

RIASSUNTO

Viene esplorato il tabù dell’auto-rivelazione del terapeuta e la letteratura che affronta i problemi di divulgazione e disabilità da una prospettiva psicodinamica. La ricerca sulle decisioni di divulgazione tra i professionisti con disabilità fisiche è limitata. La metodologia di ricerca qualitativa dell’analisi fenomenologica interpretativa è stata impiegata per comprendere l’esperienza vissuta dai professionisti psicodinamici con disabilità visiva per comprendere i processi decisionali di divulgazione in un contesto terapeutico. Sei partecipanti auto-identificati come professionisti psicodinamici ipovedenti sono stati intervistati utilizzando un questionario semi-strutturato. I risultati hanno mostrato che l’esperienza di lavorare come professionista con disabilità visiva è uno sforzo tenace, che richiede alti livelli di autoconsapevolezza e determinazione nel navigare nel campo minato dell’auto-divulgazione, osare essere visto dagli altri, mantenere il bisogno del paziente di essere visto e viaggiare attraverso la perdita e l’accettazione del sé che cambia. I risultati hanno mostrato che esiste una relazione inversa tra la probabilità di auto-rivelare la compromissione della vista e la misura in cui i professionisti lavorano con il processo inconscio e il transfert. In definitiva, la capacità di recuperare parti sconfessate del sé, ha definito la capacità dei terapeuti di prendere decisioni di divulgazione terapeutica. Vengono forniti suggerimenti per la ricerca futura, implicazioni cliniche ed etiche e raccomandazioni per i professionisti disabili e coloro che lavorano con la differenza.

ABSTRAIT

Le tabou de divulgation de soi par le thérapeute et la littérature qui adresse la divulgation en ce qui concerne les problèmes d’invalidité de la perspective psychodynamique sont explorés dans cet article. La recherche sur la problématique des décisions sur la divulgation de soi parmi les pratiquants ayant des déficiences physiques est limitée. L’Analyse Interprétative Phénoménologique et la méthodologie qualitative de recherche sont employées pour comprendre l’expérience vécue des pratiquants psychodynamiques avec des déficiences visuelles. Ainsi que pour comprendre le processus décisionnel par rapport aux divulgations de soi dans le contexte thérapeutique. Six participants se sont auto-identifiés comme étant des pratiquants psychodynamiques ayant des déficiences visuelles. Ils ont participé à des interviews partiellement structurées. Les résultats démontrent que l’expérience de travailler en tant que pratiquant ayant des déficiences visuelles requiert de la ténacité, un haut niveaux de connaissance de soi et une détermination à naviguer les terrains minés qui aboutissent à la divulgation de soi, l’audace d’être vu par autrui, tenant en compte la nécessité du patient d’être vu et de voyager de pars la perte et l’acceptation d’un être en cours de changement. Les résultats démontrent une relation inverse entre la probabilité de divulguer une déficience visuelle et la mesure dans laquelle les pratiquants travaillent avec le processus inconscient et avec le transfert. En fin de compte, la capacite de récupérer des parties de soi désavouées, définie la capacité du thérapeute pour prendre des décisions thérapeutiques de divulgation de soi. Des suggestions pour la recherche future, les implications cliniques et les éthiques sont prévues ainsi que des recommandations pour les pratiquants et ceux qui travaillent avec la différence.

ΠΕΡΊΛΗΨΗ

Διερευνάτε το ταμπού της αυτο-αποκάλυψης του θεραπευτή και η βιβλιογραφία που εξετάζει θέματα αποκάλυψης και αναπηρίας από την ψυχοδυναμική οπτική. Η έρευνα σχετικά με τις αποφάσεις αποκάλυψης των επαγγελματιών με σωματική αναπηρία είναι περιορισμένη. Μια Ερμηνευτική Φαινομενολογική Ανάλυση ποιοτικής μεθοδολογίας χρησιμοποιήθηκε για την κατανόηση των διαδικασιών λήψης αποφάσεων αποκάλυψης στο θεραπευτικό πλαίσιο από την βιωμένη εμπειρία ψυχοδυναμικών επαγγελματιών με προβλήματα όρασης. Έξι συμμετέχοντες που αυτοπροσδιορίστηκαν ως ψυχοδυναμικοί ασκούμενοι με προβλήματα όρασης, πήραν μέρος στην συνέντευξη με την χρήση ημι-δομημένου ερωτηματολογίου. Τα ευρήματα έδειξαν ότι η εμπειρία της εργασίας ως επαγγελματίας με προβλήματα όρασης είναι μια επίμονη προσπάθεια, που απαιτεί υψηλά επίπεδα αυτογνωσίας και αποφασιστικότητας στην πλοήγηση στο ναρκοπέδιο της αυτο-αποκάλυψης, τολμώντας να ειδωθούν από τους άλλους, διατηρώντας την ανάγκη του ασθενούς να τον/την δουν, καθώς και ένα ταξίδι μέσα από την απώλεια και την αποδοχή του μεταβαλλόμενου εαυτού. Τα αποτελέσματα έδειξαν ότι υπάρχει μια αντίστροφη σχέση μεταξύ της πιθανότητας για αυτο-αποκάλυψη της βλάβης όρασης και του βαθμού στον οποίο οι επαγγελματίες εργάζονται με ασυνείδητες διαδικασίες και την μεταβίβαση. Τελικά, η δυνατότητα ανάκτησης των αποκηρυγμένων τμημάτων του εαυτού, καθόρισε την ικανότητα των θεραπευτών να λαμβάνουν αποφάσεις θεραπευτικής αποκάλυψης. Παρέχονται προτάσεις για μελλοντική έρευνα, κλινικές και ηθικές προεκτάσεις, καθώς και συστάσεις για επαγγελματίες με προβλήματα υγείας και για όσους εργάζονται με την διαφορετικότητα.

SCHLÜSSELWÖRTER:

PALABRAS CLAVE:

ΛΈΞΕΙΣ-ΚΛΕΙΔΙΆ:

We see the things themselves, the world is what we see […] But what is strange about this faith is that if we seek to articulate it into theses or statements, if we ask ourselves what is this we, what seeing is, and what thing and world is, we enter into a labyrinth of difficulties and contradictions. (Original italics)

(Merleau-Ponty, Citation1968 p. 3)

Self-disclosure in its broadest definition is so ubiquitous it is hardly noticed in everyday life. However, for the therapist and especially the therapist who is (in)visibly sight impaired (SI), questions of self-disclosure are considered deeply in terms of conscious and unconscious communication in psychodynamic practice.

Merleau-Ponty (Citation1968) thoughts on the nature of seeing, and Winnicott’s (Citation1971) comments on being seen in the ‘Mirror-role of Mother’ in Playing and Reality draw attention to the idea that seeing is a multifaceted process which was considered by Jacobs (Citation1998) in this journal over 20 years ago. Jacobs (Citation1998 p. 214) considers non-verbal communication in the context of seeing and being seen and notes that ‘visually impaired therapists or clients may have different experiences from those described below, which … would be of great interest to sighted therapists’

Since then, little research was found in the literature that considers the effect of a therapist’s sight impairment and how this connects with self-disclosure decisions. The desire to respond to Jacobs’ expression of interest initiated the question for this research.

The experience under investigation is how ‘being seen’ is altered when the therapist’s sight is impaired and observation skills are conceptualised differently. In these circumstances, non-verbal and verbal communication, including self-disclosures are taking place as in any therapeutic relationship (Hobson, Citation1989). The question that emerges is how do therapists with sight impairment decide whether to verbally disclose their (dis)ability – whether it can be seen or remains unseen by the client – and how is this experienced consciously and unconsciously by therapist and client from the therapist’s perspective?

The origin of the question and research aims

While there is guidance written by able-bodied therapists for counselling impaired clients (Segal, Citation1996, Citation2006; Wilson, Citation2003, Citation2006), literature for therapists who are impaired is scarce (White, Citation2011). Qualitative research involving participants with SI is sparse (Barr et al., Citation2012; Groneck, Citation2013; Thurston, Citation2010). The British Journal of Visual Impairment, Journal of Visual Impairment and Blindness, and Disability and Society have some contributors who consider issues of counselling people with SI and the experience of being sight impaired and some of those contributors disclose their own visual or other impairments (e.g. French, Citation1995; Shakespeare, Citation1994; Thurston, Citation2010; Thurston et al., Citation2013). Within psychotherapy literature, the quiet voice of therapists with impairments may reflect a broader phenomenon, conceptualised by Shakespeare (Citation1994) as ‘invasion’:

It is not only physical limitations that restrict us to our homes and those whom we know. It is the knowledge that each entry into the public world will be dominated by stares, by condescension, by pity and by hostility.

(Shakespeare., p. 288, quoting Morris)

The temptation, with non-obvious SI, is to ‘get away with it’ (Phillips, Citation2012) and not to be seen as impaired by others, a ‘disavowal’ of absence of sight (Freud, Citation1940) or ‘superblind’, as the SI community describe people with SI who function as if sighted (Borg, Citation2005). ‘Coming out’ (Kleege, Citation1999; O’Connell, Citation2011) is a disclosure that creates a tension against getting away with it. Is it necessary to say anything at all? What about remaining ‘neutral’ (Jacobs, Citation2004)? Would it ever be noticeable, and if no one said anything did that mean they hadn’t noticed, or did they notice and say nothing? Are clients unconsciously aware of everything anyway (Joseph, Citation1985)? Would disclosure or non-disclosure ‘disable’ the process (Segal, Citation1996)? Therapists in clinical practice find themselves precariously balanced on the threshold between being seen and not being seen. This liminal place is potentially a place of creativity, and is also defined by frustration and not knowing. Kuusisto (Citation1998, pp. 11–12) conceptualises this as being in the customs house ‘between the ocean of blindness and the land of seeing […] It’s a transitory place, its foundation shifting, its promise of stasis always suspect’.

This research seeks the assistance of visually impaired practitioners in thinking about the nature of seeing and being seen. Its purpose is to add to the literature on managing disclosure of therapist impairment in the counselling room. The hope is that something can be added to the debate on disclosure and impairment and that it might have wider implications for considering therapist illness, aging and other challenges to therapists’ perceptions of themselves as able.

This research aims to investigate two main aspects of therapist self -disclosure (TSD); the intersubjective process of how, why, when and what therapists decide to disclose to clients and in what circumstances, and how therapists disclose to themselves in order to engage in the intrasubjective process of therapeutic gain.

Literature review

A search of literature revealed no existing empirical or theoretical literature specifically exploring all elements of this research: TSD issues among psychodynamic practitioners with SI in the UK. Some studies partially explore these elements (Axelman & Kashani, Citation2009; Bottrill et al., Citation2009; Burke Valeras, Citation2007; Calonico, Citation1995; Carew, Citation2009; Hansen, Citation2008; Hernandez, Citation2011; Jeffery & Tweed, Citation2014; Mallinckrodt & Helms, Citation1986; Moore & Jenkins, Citation2012; O’Connell, Citation2011; Parker, Citation2011; Pizer, Citation2016; Shapiro, Citation1990; Stanley et al., Citation2011).

The starting point was the literature on self-disclosure and non-disclosure leading to the literature on disability and impairment in general. These two areas are then drawn together by reviewing the small body of literature which combines TSD and impairment.

Theoretical orientation and TSD: The debate for and against TSD

The debate about TSD is marked by controversy resulting in a dichotomized views based on theoretical schools of thought, cultural context, definitions and therapeutic effects (Wachtel, Citation2011). One aspect that doesn’t provoke conflict is the complexity and ill-defined nature of TSD. Bloomgarden and Mennuti (Citation2009), Farber (Citation2006), Henretty and Levitt (Citation2010), Maroda (Citation2010), Peterson (Citation2002) and Stricker and Fisher (Citation1990) are agreed that every therapist needs to reflect on their interventions and navigate the question of self-disclosure, based on their own circumstances, individual relationships with each client and with the interests of the client at the centre. Henretty and Levitt (Citation2010) point out, in their extensive qualitative review of over 30 predominately North American research studies, that 90% of therapists self-disclose at some point. However, TSD represents only 3.5% of all therapist interventions suggesting TSD is used by many but sparingly. Despite the vast body of research conducted, Henretty and Levitt (Citation2010 p. 64) conclude therapists are left feeling vulnerable and anxious about TSD because of ambiguity and contradictions in training, ethical guidelines, empirical findings and theoretical conceptualizations.

Pro-disclosure perspective

Sydney Jourard is credited with the first use of the term ‘self-disclosure’ when in 1964 he assessed people’s likelihood to disclose aspects of themselves to others (Cozby, Citation1973 p.73). In the 1950s, Rogerians were the first clinicians to adopt TSD in practice (Farber, Citation2006). Those from a humanistic tradition used TSD to communicate congruence, positive regard, authenticity, transparency and equalise the balance of power in the therapeutic relationship. Since then, client-centred therapists have argued that by cautiously modelling openness, strength, vulnerability and sharing intense feelings, the therapist invites the client to follow their lead. The outcome intended is the creation of trust though perceived similarity, credibility and empathic understanding (Bloomgarden & Mennuti, Citation2009; Henretty & Levitt, Citation2010). Segal (Citation1993 p. 13), who writes from a Kleinian perspective, also emphasises the importance of being client-centred but without necessarily modelling via TSD: “being ‘client-centred’ doesn’t mean doing everything the client wants you to do”.

Non-disclosure perspective

Though critics accuse Freud of breaking his own rules on anonymity, neutrality and abstinence (Lane & Hull, Citation1990), many of these infringements occurred during the early years of the development of psychoanalysis (Farber, Citation2006; Peterson, Citation2002). What remains in psychoanalytic tradition is the idea of remaining a neutral and anonymous medium, upon which patients can project transference distortions for the purpose of interpretation (Farber, Citation2006).

Freud’s comment on technique (Freud, Citation1912 p. 111) suggests the oft-cited use of ‘evenly-suspended attention’ and posture of the analyst as: ‘opaque to his patients and, like a mirror, should show them nothing but what is shown to him’ (Freud, Citation1912 p. 118). Less often quoted is what Freud writes next, that in practice ‘some suggestive influence’, which could be seen as Freud’s term for TSD, may be combined with analysis ‘in order to gain a perceptible result in a shorter time – as is necessary for instance, in institutions’ (Freud, Citation1912 p. 118). Freud concedes this is a valid method but cannot be called true psychoanalysis in his terms. A contemporary proponent of this is Coren (Citation2010, p. 162) who suggests that in short-term work, TSD can be effective in building alliance and short-circuiting clients’ defences.

It is on Freud’s definition of true psychoanalysis that perhaps the debate on self-disclosure seems to hang. Many quote Freud’s idea that disclosure begets disclosure. Jourard (Citation1971), for example, implies that client disclosure is the goal in and of itself. Freud (Citation1912 p. 118) suggests the patient may feel obliged to reciprocate with a confidence they are already aware of. The psychoanalytic aim is to discover what lies in the unconscious and cannot be accessed so readily. The focus on the unconscious is a ‘principle hypothesis of psychodynamic work’ (Jacobs, Citation2004 p. 11) and central to the debate about TSD. Examples of contemporary thinkers in line with Freud’s focus on the unconscious, and therefore on the non-disclosing end of the disclosure spectrum, include Langs (Citation1998), Lemma (Citation2003) and Segal (Citation1993). Maroda (Citation2010) and Bridges (Citation2001) integrate some of the differences outlined above.

Contemporary thinking on TSD is summarised by Billow (Citation2000 p. 66) after an extensive review of literature prior to 2000: ‘the rule is there are no hard and fast rules. One guideline is to consider whether they [TSD] work to open or close things up between patient and analyst’. The question is not whether to disclose or not but to reflect on how TSD affects the therapeutic process.

The literature suggests the decision to disclose to a client is a nuanced, non-binary decision dependent on theoretical orientation and differing perceptions of how client needs are met.

Impairment and sight impairment

Wilson (Citation2003 p. 12) suggests that the relative absence of psychoanalytic writing about disability and death anxiety suggests a link between the two and recommends that to work with disability requires resolution of death anxiety and awareness of defences, especially that of denial. A search of the Psychodynamic Practice and Counselling and Psychotherapy Research journals confirmed that since Wilson’s (Citation2003) comment, there is only a small body of literature in UK publications in the area of impairment and SI (Barr et al., Citation2012; Charmaz, Citation1995; Fitzerman, Citation1996; Segal, Citation1996; Spencer, Citation2000; Thurston, Citation2010; Thurston et al., Citation2013; Wilson, Citation2003, Citation2006).

The broad messages from the review are: 1) psychoanalytic theory is useful in constructing a model for thinking about impairment because it articulates integration of the individual’s internal and external world with society; 2) the role of ‘others’ (supervisors/employees) in the lives of therapists with impairments is critical in defining their experience of being impaired and working therapeutically.

Models of disability

Models of disability are constructs that frame thinking about disability and are a common starting point for many writers in Clinical Psychology, Sociology and Psychotherapy (Bickenbach et al., Citation1999; Fitzerman, Citation1996; Goodley, Citation2011; Olkin, Citation2002; O’Connell, Citation2011; Shakespeare & Watson, Citation2002; Watermeyer, Citation2012; Wilson, Citation2003). The medical, moral and society models conceptualize the differing ways in which others have viewed people with a disability (Olkin, Citation2002). Shakespeare (Citation1994), Goodley (Citation2011) and Watermeyer (Citation2012) make a case for the value of psychoanalytic thought in the society model by drawing together the role of society and the individual. Watermeyer (Citation2012 p. 171) cites Fanon’s concept of internalised oppression to suggest that a disabled person’s unconscious collusion with societal discrimination against the disabled body as an out-group will result in a ‘recapitulation of the status quo’. Watermeyer advocates for consciously processing these traumatic internalisations therapeutically.

Psychodynamics and impairment

Asch and Rousso (Citation1985) and Cubbage and Thomas (Citation1989) provide an overview of the relevance of Freud’s work for disability, argung for the inclusion of therapists with impairments in psychotherapeutic practice. Grzesiak and Hicok (Citation1994 p. 249) offer a brief history of psychotherapy and physical disability suggesting that there are no differences in working with those who have physical difficulties than with “so-called ‘ordinary people’”. They outline relevant areas of psychodynamic theory for impairment; mourning and loss, secondary gain, trauma, ego defences, castration anxiety and narcissistic injury. Wilson (Citation2003) reviews different psychodynamic approaches to working with impairment.

Goffman (Citation1963) is a Canadian sociologist referred to by many writers (Burke Valeras, Citation2007; Fitzerman, Citation1996; French, Citation1995; Hernandez, Citation2011; O’Connell, Citation2011; Vick, Citation2007). His seminal text on stigma and the ideas of ‘covering’ and ‘passing’ are made contemporary by Yoshino (Citation2007 p. ix). To ‘cover’ is to tone down a disfavoured identity to fit into the mainstream; to choose not to be known as different. ‘passing’ is to adopt a ‘don’t ask don’t tell’ attitude, where difference is known but ignored. While these are not psychodynamic theoretical ideas, they connect with the theory on disavowal (Freud, Citation1940) and provide routes into thinking dynamically about the stigma often associated with impairment.

Winnicott’s (Citation1971) elaborates on Lacan’s concept of the mirror phase, as a reflection of a child’s emerging self; a reflection of the baby in the mother’s eyes.

When I look I am seen, so I exist.I can now afford to look and see.I now look creatively and what I appreciate I also perceive.In fact I take care not to see what is not there to be seen (unless I am tired)

(Winnicott, Citation1971 p. 134)

In this paradoxical riddle, the notion of ‘being seen’ in the psychological sense is linked to the literal ability of the mother to see (Jacobs, Citation1998). An implicit fear of remaining unseen is the atrophy of creative capacity and a failure to find oneself reflected back by the environment (Winnicott, Citation1971 p. 131). Winnicott’s (Citation1971) draws attention to the idea that a mother will find other sensory ways of communicating her recognition of the baby if the baby is blind but doesn’t consider the effect of a care giver’s SI.

Issues of loss of body unity and loss of omnipotent feelings are associated with impairment. Charmaz (Citation1995, p. 357) suggests adapting to impairment means ‘struggling with rather than against illness’. Chernin (Citation1976) reflects that when he acknowledged his own omnipotent feelings, he could also accept his illness and limitations which released him from the guilt of leaving his patients in need.

Fitzerman (Citation1996) was the only author found who self-discloses a visible physical impairment and writes from a psychodynamic perspective. She suggests that anger is likely to be present, even if not acknowledged by an impaired client, and is a defence against depression and narcissistic injury. While acknowledging her impairment, the focus of her article is on clients not therapists with impairments.

TSD and impairment research

Miller (Citation1991 p. 348) reviews the literature before 1991 and considers both additive and subtractive points of view found in research assessing client response to therapist impairment. Miller suggests that therapists self-disclosing a disability at the beginning stage of the counselling process are ‘probably safe to do so’. O’Connell (Citation2011) researches TSD of therapists with visible physical disabilities and concludes that disclosure of disability-related material should be initiated by the therapist early in the therapeutic encounter and be phrased in an open-ended way that leaves room for future discussion (O’Connell, Citation2011 p. 74).

Methodology

Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) was chosen as disability and impairment are phenomena that are often generalised and individual experience is lost. This research adopts an ideographic qualitative approach because ‘no two people experience disability in the same way, just as no two people experience life in the same way’ (Wilson, Citation2003 p. ix).

The research inhabits ‘insider’ status (Smith et al., Citation2009 p. 42) describing the researcher’s eye condition in the recruitment letter for transparency when asking participants to discuss their eyesight in the research. By disclosing, the dynamic was set for the interview in a research frame, providing participants with the freedom to respond without the special conditions of a therapist-client dyad. Every effort was made to bracket the researcher’s response and experience as a therapist with SI, but it is inevitable that unconscious aspects of the researcher’s fore-concepts (Finlay, Citation1999) influence this work.

Ethical approval was received and participants were recruited by referral and through snowballing (Smith et al., Citation2009). Due to the nature of the research, careful consideration was given to accessibility and this was managed on a case-by-case basis according to the participants’ needs. Six, sixty minute interviews were conducted with psychodynamic practitioners with at least one year’s post qualification experience. All research participants self-identified as having SI, which might suggest a degree of similarity in the way that participants experienced ‘seeing’. However, each participant had an individual experience of sight loss and of working with SI. The physical eye conditions were described as: Lattice Dystrophy and Horner’s syndrome, Glaucoma, Sjogrens Syndrome, Retinopathy of Prematurity, Retinitis Pigmentosa, Retinopathy with Glaucoma and total blindness (cause not specified).

Co-created researcher/participant vignettes enable each individual’s circumstances to be known (names have been changed for anonymity)

Mary is 61, qualified as an integrative counsellor 16 years ago and works in student counselling and private practice. Her experience of sight change began as she was training. She has a fluctuating condition, which can change quickly, sometimes hour-to-hour, reducing access to sight significantly. When needed, Mary uses magnification devices and wears dark glasses.

Hazel is mid to late 50s. She has 30 years’ experience working as a psychodynamic counsellor and 14 years as a psychoanalytic psychotherapist in both education and medical sectors. Hazel lost 95% of her sight as a young adult and the remaining 5% six years ago. Her guide dog is present in her room for therapeutic sessions, unless clients ask for it to be removed. She uses a symbol cane and computer software, which translates written text to speech.

Georgia is in her mid 60s. She initially trained psychodynamically but now identifies herself as integrative, having additionally studied Play Therapy, Gestalt and Transactional Analysis. She is experienced in telephone and online counselling and has her own private practice. Georgia has two eye conditions: one, diagnosed 20 years ago, is degenerative but doesn’t influence the way she practices as yet, and the other, recently diagnosed (three years ago), results in eye watering/dryness. She manages her eye condition with eye drops which lubricate and reduce irritation. She also wears tinted and photochromic glasses to reduce the effects of light conditions. Georgia uses magnification devices for reading

Amanda is 53 and qualified as a psychodynamic counsellor two years ago. She works in private practice and for a health organisation. Amanda’s experience of sight change began 14 years ago. She has a fluctuating condition which can change quickly, reducing access to sight significantly. Her sight is currently better than it has been. Amanda uses magnification devices and a white stick when travelling. In the therapeutic setting she sometimes wears glasses with one frosted lens.

Elizabeth is in her early 70s and has been practising as a psychoanalyst for 30 years. She offers long-term analysis in private practice. Elizabeth’s eye condition has been evident for many years but developed life-changing consequences in 1988 when she stopped driving. It is a degenerative condition, resulting in a narrowed field of vision. She uses a white stick outside and is about to acquire a guide dog.

Steve is 63, qualified as a counsellor 12 years ago and works short- and long-term with couples and individuals. Steve was born unsighted but could perceive light/dark until a haemorrhage in his eyes as a young adult caused complete sight loss. Steve uses a Braille Notetaker in assessments as his pen and paper. When he had a guide dog, he didn’t take it into therapeutic sessions to avoid possible distraction.

Research results

Phenomenological themes

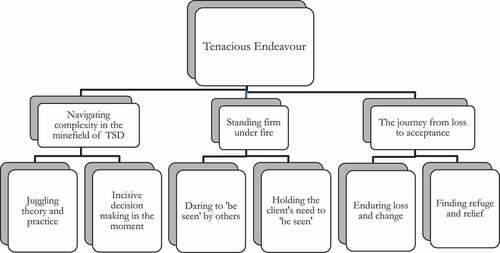

‘Tenacious endeavour’ defines the essential quality of all six participants’ experience of working as therapists with SI. Three master themes demonstrate how the phenomenon of ‘Tenacious endeavour’ is experienced in the therapeutic setting, in the world with others and internally.

Navigating complexity in the minefield of TSD: investigates the experience of engaging in the therapeutic process. ‘Self-disclosure, … is a real minefield. I would go very warily alongthat route’.

Standing firm under fire: explores the experience of working with others, clients’ and authority figures’ projections and prejudice. ‘I had (hesitating tone) major battles, in that the issue of disclosure came up … it was thought that my patients should be informed in advance that I was blind’.

The journey from loss to acceptance: considers the experience of the changing self. ‘When I got the first diagnosis, … it was quite a shock … I ran a thing about; “will I be blind within a year?” Calmed down … and had some extra therapy’

Nuanced and complex sub-themes emerged within master themes and they are reflected in the framework for results in .

Juggling theory and practice

Every participant discussed their approach to self-disclosure with reference to their training and theoretical model in terms that either distanced them from or kept them close to their original psychodynamic training. Each participant juggled theory and practice in different ways.

The sense of juggling comes from three elements that seemed to be perpetually in motion and sometimes in tension:

Implementing training and theoretical models in practice.

Assessing potential and unknown therapeutic outcomes of TSD.

Building the therapeutic relationship.

In order to conceptualise the different approaches to juggling these three elements, participants’ approaches are located on a spectrum from non-disclosure to pro-disclosure as: classic (non-disclosure), experimental and non-conformist (pro-disclosure).

Classic approach: Hazel and Elizabeth took the most faithful approach to classic psychodynamic theory with regard to TSDSI in inhabiting a predominately non-disclosing position. Non-verbal disclosures are acknowledged as inevitable and SI is grouped with all other non-verbal/factual disclosures. For Hazel, TSDSI is used therapeutically in the context of managing transference distortions. For example:

You can represent the impaired parent … I do have real empathy for [the client], if there’s been a sibling … or a parent whose been disabled. I’m very mindful that the transference can be very (emphasis) powerful … and possibly too powerful for the person … to tolerate.

In these circumstances, TSDSI is used to elevate painful and potentially unhelpful transference.

Experimental approach: Amanda and Mary were experimental in their approach to TSDSI, trying things out and then modifying their approach based on their eye conditions’ fluctuations and their experience with clients.

Amanda acknowledged that non-verbal disclosure makes a totally purist approach impossible. ‘I’m not a tabula rasa’ and experimented with factual TSDSI in the first session. Amanda acknowledges that ‘there are arguments about this and I’m not sure that there’s a right or wrong approach’. A client with cerebral palsy responded silently to first session TSDSI and changed the subject, but did not return. Amanda felt she had ‘made a mistake’ by taking something away from the client in disclosing SI:

I set up competition … she wasn’t coping very well and here was I, in her phantasy of me, I was okay, then I told her that I’ve got this disability

Based on experience, Amanda has shifted to a position where she waits for a natural moment to disclose her sight condition.

Non-conformist approach: Georgia and Steve, though starting with training that promoted non-disclosure, have moved to pro-disclosure positions. Georgia uses experience in her own therapy to develop her stance on TSD:

It’s the human edge where therapy works. I’m not just going to … behave like an automaton, I’ve experienced a few of those … it’s like there are certain religions … if you’re not with us you’re dammed (emphasis) forever and I think I’m one of the eternal “don’t knows”, … It’s their therapy not mine (pause) which is why when I’m in therapy I wanted it to be my therapy (sigh)

The need for therapeutic alliance takes precedence over the classical non-disclosing stance. However, Georgia was less pro-TSDSI, especially if SI is less obvious. At whatever point on the spectrum therapists were located, all were agreed on the importance of decisions being made for client benefit.

Incisive decision making in the moment

All participants were clear that TSDSI decisions were made on an individual basis and were dependent on client presentation and therapeutic goals. For example, Elizabeth commented that she wouldn’t use TSDSI with a borderline patient. Mary said she was less likely to use TSDSI with a short-term client. It was evident from the data that therapists thought deeply about when and why they would use TSDSI, as summarised by Elizabeth:

I don’t know whether I’d say, … ‘I don’t see things’, and I may say that meaning, I don’t see things literally or I don’t see things in a psychological sense, I’m not understanding something, and that the two would be concomitant really. Which I would take up, I can’t say categorically because I’d be playing it by ear.

Although participants had differing views, there was agreement that the timing of effective TSDSI is critical. This demonstrates the skill of holding back on opportunities for disclosure, in pursuit of precise and well-timed interventions necessary to make effective TSDSI for therapeutic gain.

Daring to ‘be seen’ by others

While taking a stand with colleagues and organisations invoked rage at the unnecessary nature of such battles, there was a willingness to stand firm against the hostile projections of others, in order to hold their need to ‘be seen’ as part of the therapeutic process using TSD where necessary.

All participants commented on times when they had been forced into a position of having to take a stand with a training organisation or employer/colleague in order to defend their ability or needs.

Hazel had ‘major battles’ with the training organisation’s policy of disclosing her blindness pre-first session:

I was really discouraged from challenging it [by supervisor], the feeling was that I would actually put my training at risk. I was told ‘don’t rock the boat’

Hazel felt individuals acted out prejudice in the organisation. She was successful on her own behalf but didn’t change policy for those who followed. Incidents of conflict have long-lasting effects on the internal world of those with impairments as acknowledged by Hazel at the end of the interview:

I think what I’ve realised is, that whole training experience still has raw edges, that really pissed me off (low voice).

Talking about the experience of 14 years ago activated rage still deeply felt and suggests that daring to be seen as impaired is costly but essential to gain access to professional therapeutic training.

Steve describes himself as a therapist who is blind rather than a blind therapist. He adapted this language to communicate his ability despite what others, his past employers in this case, might perceive as a disability.

I was aware that as a blind person you had to fight to get what you believed you could do … I didn’t want to appear as someone who had a chip on their shoulder but on the other hand I wanted to stand my ground if I believed in it.

Mary had the experience of being treated like everyone else when she needed to be treated differently. Personal printers were removed in favour of communal ones, making access to printed information complex:

it’s [SI] acknowledged at appraisals… it’s just when resources get squeezed everybody gets squeezed regardless, … .it’s so trivial but, … it can’t be understood can it really, how it affects us and what it means for us in terms of our life

Although Mary stood her ground and got through the necessary ‘red tape’, she was left with feeling unnoticed and misunderstood.

Holding clients’ need to ‘be seen’

There were rich examples of how therapists hold clients without seeing. The few represented here show both the creativity and challenge that therapists engage with in the task of holding the client.

All participants demonstrated ways in which they had adapted to SI and observed the client without seeing them, holding their clients’ need to be seen:

You can hear it in the voice … You can pick up when somebody is not making eye contact with you because the voice shifts … . You can hear the tears … . You can sense that they’re tucked into a corner or sitting on the edges of the seat

Amanda refers to her use of countertransference as a tool for observing:

I’ve always been very alert to countertransference, but I think this [SI] is another dimension to it that I’m aware of, and picking up on unconscious processes … may or may not be to do with [SI], but just the fact that there might be makes me tune in more.

All participants talked about the difficulty of dealing with client projections, the fear of death, association with vulnerability and loss that can be evoked by proximity to impairment:

I’ve had to deal with the hostility towards me because I’m blind or shall I say hostility towards me which got expressed around my blindness.

Hazel made sense of the experience of this hostility by outlining her view on where the hostility was coming from, summarized here as:

People are terrified that they too could lose their sight and a lot of the hostility is a projection of that fear.

They project their own vulnerability onto me, if they don’t want to face that vulnerability themselves; they want to get rid of me and thereby get rid of it.

I think it’s sometimes envy and attempting to spoil what I have.

Enduring loss and change

The journey from loss to acceptance is divided into two sub-themes: ‘enduring loss and change’, which considers therapists’ experience of coming to terms with the changing self; and ‘finding refuge and relief’, which outlines the places where therapists find relief from isolation.

Five participants talked about enduring ongoing losses that occurred after initial diagnosis. Georgia recognised the process of coming to terms with SI as a series of losses not a one-off experience:

it’s not just about the disability is it? It’s about how psychologically we deal with it, which can be very erratic. It’s not like you get the diagnosis and then you have the breakdown. It’s several years later you suddenly get that jerk which is ‘ooh my last test wasn’t as good.

For those with fluctuating conditions (three participants) the sight loss process was unpredictable and sometimes unbearable; the future is unknown and frightening:

The disease eats into the corneas … it’s unbearable, so I’ve had two grafts on the left eye, but they weren’t successful … didn’t get the vision back. So I just fear for the right eye when the time comes … . Err, (pause) that I won’t get vision back.

Five participants acknowledged the difficulty of enduring sight loss and could identify in themselves tendencies for disavowal, ‘Part of me wants to disavow the whole thing. I have to admit to that really’. There was a strong desire not to be noticed as different, ‘not to be seen to be vulnerable … . not to be seen to be out of the ordinary. Um, (slight pause) I’m getting less inhibited’.

The fear of being seen to be vulnerable was based on associations that were hard to own, ‘I don’t know whether you call it pride or a wish to be in a position of strength … when I articulate it, it sounds stupid in a way’.

The process of accepting the changing self requires in-depth reflection. Amanda found therapy a helpful place to process her changing sight, identity as a therapist and attitudes to TSDSI:

I made the decision that I wasn’t going to disclose because of how it was making me feel about my own sight loss … I think this is quite important to say, that I was almost apologizing for it.

Finding refuge and relief

Identifying places where therapists seek refuge and relief was not part of the question structure, but five participants mentioned at least one experience where they had found refuge and relief from the loneliness of facing the challenges of SI.

Therapists and supervisors were most often referred to as a place of refuge:

If somebody else can understand. I mean it’s just not something you want to talk about, or other people want to talk about is it? It’s good to talk to my supervisor, … to have an outlet of frustration and how it does affect me.

Clinical and theoretical implications

The aims of this research were to explore the lived experience of psychodynamic practitioners with SI and to understand their approach to TSDSI. The main finding runs implicitly throughout all result sections but is most evident in the phenomenon of ‘juggling theory and practice’. The research found that there is an inverse relationship between likelihood to use TSDSI and the extent to which practitioners work with unconscious process and transference. This is consistent with Carew’s (Citation2009) findings. Participants who work with the ‘classic approach’ tend to use TSDSI, only when relevant to transference and interpretation of unconscious communication, avoiding first session disclosure. The ‘non-conformist approach’ led participants to focus more on the therapeutic alliance and ‘being human’. TSD was used to facilitate the process of open communication especially in the early stages of therapeutic relationship development.

Three main factors are considered in making decisions about TSDSI:

How does TSDSI affect development of transference?

How will TSDSI contribute to building the therapeutic alliance?

What are the likely outcomes of TSDSI in relation to therapeutic goals?

Practitioners make TSDSI decisions by using a combination of their training and theoretical positions, experiences of working with SI, in-depth reflection and monitoring of the changing self. TSDSI decisions are tailored to the client’s unique circumstances and the intersubjectivity of each therapeutic dyad. The experience of sustaining this level of diligence in addition to the ordinary challenges of being a psychodynamic practitioner is interpreted phenomenologically as a tenacious endeavour.

Issues that drive the decision-making process for TSDSI are the client’s impairment stability and noticeability, the extent of client disturbance and type of disturbance, the therapist’s approach to transference and unconscious process and the likely therapeutic gain of TSDSI.

The nature of seeing and being seen

This research found that the notion of noticeability is a subjective construct in line with Merleau-Ponty’s (Citation1968) philosophy. Client observation skills are variable, determined by the client’s eyesight, preoccupation with his or her own concerns and natural observations skills. Therapist’s with SI grapple with how seen a client is in a literal sense, and how ‘seen’ the client feels, in the psychological sense. Participants spoke about times when clients had been unable to tolerate being unseen, in both versions of the meaning of ‘being seen’ and could also give examples of what a relief it might be for clients not to ‘be seen’. The results provided evidence that therapists endeavour to ensure that they are self-aware and reflective on a client-by-client basis and are creative and dedicated to the work of holding their clients’ need to ‘be seen’.

If literal seeing and psychological understanding become concomitant, Winnicott’s (Citation1971) notion of the primitive fear of not being seen can become activated. Underpinning any other therapeutic goals, the therapist with SI must embrace the association between the unseen and the need to be seen. For clients, It could be therapeutic to overcome primitive fear and recognise that it is possible to be seen psychologically without being seen literally. When the therapist is sight-impaired this is part of the work, either consciously via disclosure or through unconscious communication.

The results showed that disavowal is, at varying degrees of conscious recognition, an issue with which therapists must engage. Disavowal (Britton, Citation1994; Fitzerman, Citation1996; Shakespeare, Citation1994) is a defence that needs special consideration on the part of the therapists with SI. The results show that therapists with SI endeavour to unearth the areas that could ‘disable’ the therapeutic process, and engage with the desire to deny difficulty and avoid the issues raised by absent or limited sight (Segal, Citation1996). Some participants experienced a unique difficulty working with impaired clients consistent with Fitzerman’s (Citation1996) and Borg’s (Citation2005) observations of working with impaired clients who may feel competition and envy towards the impaired therapist.

Participants’ experience of ‘being seen by others’ were in line with Goodley’s (Citation2011) and Watermeyer’s (Citation2012) papers on the connection between societal oppression and internal oppression. Society’s impact on individual experience of the self as impaired can be disabling. Participants articulated ways in which they had ‘been seen’ by others in both helpful and less helpful ways. To varying degrees, participants acknowledged that the ability to ‘stand firm’ requires awareness of the need to resist introjected forms of society’s oppression. Participants’ experiences of ‘standing firm’ resonated with those of Kleege (Citation1999), Kuusisto (Citation1998) and Yoshino (Citation2007) and echoed themes of ‘getting away with it’ (Phillips, Citation2012), ‘covering/passing’ (Goffman, Citation1963) and ‘coming out’ (O’Connell, Citation2011).

Ethical aspects of working as a therapist with sight impairment

The results showed that participants struggled to self-disclose their disability to colleagues in organizations because of past negative experiences. Places where participants expected to find refuge and relief were sometimes places of difficulty and required tenacious endeavour to gain access to what they needed, exemplified by Mary’s printer battle and Hazel’s fight for training patients. In training organisations and employment settings, able-bodied individuals act out organisational, societal and personal defences against engaging with impairment which disable the therapist with SI. This forced participants to stand their ground and seek other places of refuge and relief with family, supervisors or therapists who can understand the traumatising nature of these experiences.

There is a difference between having a good disability policy in place and acting in the spirit of those policies in everyday life (Olkin, Citation2002). It seemed that it was in the every day ‘trivial(Mary)’ details of being trained or working that therapists with SI experienced difficulty and discrimination, which detracted from the primary task of working therapeutically with clients.

The BACP ethical guidelines (Bond et al., Citation2013) state that ‘practitioners should not allow their professional relationships with colleagues to be prejudiced by their own personal views about a colleague’s […] disability’ (Bond et al., Citation2013 p. 9). It is easy to agree with this on paper, while the experience of not allowing prejudice to encroach on the day-to-day lives of practitioners with impairments seems difficult to navigate. The logical corollary to this is how a therapist with impaired sight can respond to these ‘trivial’ yet prejudiced experiences. This will be considered in recommendations for practice.

While the research did not specifically focus on ethical guidelines and how participants thought about ‘fitness to practice’, it was evident from the interviews that practitioners considered their ability to work and continually monitored themselves in supervision.

Participants reported a mixed experience of working with supervisors ranging from a great level of comfort in discussing issues relevant to SI to a degree of discomfort. The supervisor’s ability to work with difference in terms of willingness and skill were central to participants’ experience in supervision. This is consistent with Spencer’s (Citation2000) thoughts on the need to develop potential space and provide proactive support.

Lifecycles of becoming

The phenomenon of ‘enduring loss and change’ attempts to capture the sense of the loss that endures over a long period and also bearing the weight of significant loss and change. Implicit in the research findings is the connection between the experience of becoming impaired and becoming a therapist. It has been argued that both processes involve coming to terms with loss; loss of a former self (Charmaz, Citation1995) or the loss of omnipotent feelings (Chernin, Citation1976). The experience of becoming sight-impaired before training (three participants) is a different experience to becoming qualified to practice first and then losing sight (two participants). There is a third experience where becoming a therapist converges with sight loss: only one participant represents this position. The adaption process for those who lose sight after becoming a therapist seems most challenging in TSDSI terms, as there is an accustomed way of working that needs to be adapted and integrated with the changing self. For those who trained as sight-impaired, SI had been integrated into the training process and a professional stance on TSDSI developed, based on an already changed self.

The results confirmed Wilson’s (Citation2006) comment on the sense that people with impairments must continually process the difference between Merleau-Ponty’s concept of the perfect ‘wished for body’ and the reality of the ‘body in the moment’ (Wilson, Citation2006 p. 178). Inhabiting the space between the wished for and real body creates a sense of being in ‘eternal transition’. Participants were at different stages in the process of negotiating the tension between these two bodies. The experience of this tension felt more active among those with fluctuating or degenerative conditions, where TSDSI decisions were continually navigated in day-to-day issues of the working lives of therapists with SI. While those with stable SI did not experience less difficulty, there was a sense of knowing what the difficulty would be each day, as they trained without sight and had been without sight for a long time.

Implications for practice and theory

The need to remain reflective and self-aware was strongly communicated by participants. The necessity of engaging in personal therapy if SI changes or develops for the first time when qualified is key to remaining fit to practice. Recognising potential areas of disavowal and processes of physical loss seem essential for practitioners to consider. An awareness of symbolism and the different ways in which clients may respond to SI given their history and experience is critical to remaining client-centred. The connection between SI and primitive fears of not being seen, feelings of omnipotence, anger and death anxiety are inevitably active in therapeutic work and need to be worked through in order to continue to provide effective therapy for clients.

Being unapologetic for impairment (Chernin, Citation1976) and embracing adaptation to the changing self (Charmaz, Citation1995) are important processes, as exemplified explicitly by Amanda who used personal therapy to become unapologetic and changed TSDSI practice in line with that internal shift. This echoes the writing of Watermeyer’s (Citation2012) who highlights the benefit of consciously working through unconsciously internalised oppression.

TSDSI decisions need to be weighed against therapeutic goals and the unique needs of each client. The therapist’s training and practice will determine how and when TSDSI are made, and while they are always made with the clients’ best interests at heart, the therapist’s view on beneficence will depend in part of their theoretical stance.

The degree of SI noticeability can affect the decision to disclose with a tendency towards increased use of TSDSI, the more noticeable the impairment. However, when noticeable, some therapists still decide not to self-disclose and wait for the material to lead them. Great attention needs to be paid to the material which clients present and SI is an additional layer that needs to be sought in the material.

Supervisors and therapists of sight-impaired practitioners need to equip themselves with knowledge and understanding of outcomes and issues for practice in order to proactively offer support for those with sight conditions, as underlined by Fitzerman (Citation1996) and Spencer (Citation2000), and in order to prevent their therapeutic relationships with impaired clients or supervisees becoming ‘disabled’ (Segal, Citation1996).

Supervisor training on difference could include more detailed research-based findings on working with impairment and specifically how to work through ethical issues of fitness to practice, with guidance on how to translate the principle of working without prejudice into the day-to-day trivial matters that cause therapists with SI to be misunderstood. The provision of reflective space within organisations could create an environment for inevitable issues of prejudice to be worked through in a group. If defences are predicted and thought through in an open, thinking team, client work is less likely to be contaminated by unresolved organisational dynamics.

Ethical guidelines with regard to fitness to practice are open to interpretation. The divergent experiences of therapists with SI in supervision suggest it would be interesting to research these issues at a deeper level, as the definition for ‘impairment’ in the BACP guidelines seems vague and perhaps deliberately so, giving practitioners the space to navigate this definition for themselves. How to equip practitioners to do this ethical thinking seems lacking in the available literature and initial training.

Olkin (Citation2002) highlights accessibility failures in training. ‘We are not training non-disabled psychologists to work with clients with disabilities, nor are we training many psychologists with disabilities. No wonder disabilities have been called the hidden minority’ (Olkin, Citation2002 p. 132). Training courses need to better equip therapists in general and impaired therapists on the issues, debates and conditions where disablism thrives and offer strategies for avoiding them. This may mean looking outside the psychotherapeutic literature and theory as it is currently an underdeveloped area in psychodynamic theory.

Recommendations for further research

Future research could consider taking a ‘case study approach’ (Smith et al., Citation2009 p. 52) to more deeply understand the lived experience of psychodynamic therapists’ disclosing and living with SI.

The use of a ‘triangulation approach’ (Smith et al., Citation2009 p. 53) would also be interesting to gain perspectives of impairment from the point of view of the client, therapist and/or supervisor or organisational representative. Such a study could investigate at deeper levels how difference and impairment were experienced from different perspectives and could include an analysis of how ethical guidelines are worked out in practice.

Ultimately this research concludes that an internal identity shift is needed to re-internalise disavowed parts. Being sight-impaired is to be ‘bi-abled’ like bi-cultural, an experience of living in two worlds able to adapt one’s identity to fit the situation and context (Burke Valeras, Citation2007 p. 54). Integrating the unable and able parts of the body and mind, known and unknown, in both those who identify as able bodied and as disabled, makes space for therapeutic client-focussed self-disclosure decisions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Laura Evers

Laura Evers has a MSt. in Psychodynamic Practice from Oxford University. She is a psychodynamic postgraduate course tutor at Oxford University, therapist and supervisor in private practice. She qualified in 2014 and has previous experience working in the secondary and tertiary education sectors counselling students, accredited by UKCP.

References

- Asch, A., & Rousso, H. (1985). Therapists with disabilities: Theoretical and clinical issues. Psychiatry, 48(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.1985.11024263

- Axelman, M., & Kashani, D. R. (2009). Issues faced by therapists with visible disabilities: The role of transference, anxiety, and the notion of otherness in the therapeutic relationship. Journal of Psychology and Counselling, 1(2), 30–38.

- Barr, W., Hodge, S., Leeven, M., Bowen, L., & Knox, P. (2012). Emotional support and counselling for people with visual impairment: quantitative findings from a mixed methods pilot study. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 12(4), 294–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733145.2012.663776

- Bickenbach, J. E., Chatterji, S., Badley, E. M., & Üstün, T. B. (1999). Models of disablement, universalism and the international classification of impairments, disabilities and handicaps. Social Science and Medicine, 48(9), 1173–1187. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00441-9

- Billow, R. M. (2000). Self-disclosure and psychoanalytic meaning: a psychoanalytic fable. Psychoanalytic Review, 87(1), 61–79.

- Bloomgarden, A., & Mennuti, R. B. (2009). Psychotherapist revealed: Therapists speak about self-disclosure in psychotherapy. Routledge.

- Bond, T., Griffin, G., Jamieson, A., & O’Dowd, J. (2013). Ethical framework for good practice in counselling and psychotherapy. BACP House.

- Borg, M. B. (2005). “Superblind”: Supervising a blind therapist with a blind analysand in a community mental health setting. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 22(1), 32–48. https://doi.org/10.1037/0736-9735.22.1.32

- Bottrill, S., Pistrang, N., Barker, C., & Worrell, M. (2009). The use of therapist self-disclosure: Clinical psychology trainees’ experiences. Psychotherapy Research, 20(2), 165–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300903170947

- Bridges, N. A. (2001). Therapist’s self-disclosure: expanding the comfort zone. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 38(1), 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.38.1.21

- Britton, R. (1994). The blindness of the seeing eye: inverse symmetry as a defense against reality. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 14(3), 365–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/07351699409533991

- Burke Valeras, A. M. (2007). To be or not to be disabled: Understanding Identity processes and self-disclosure decisions of persons with a hidden disability [ Ph.D.] Arizona State University.

- Calonico, L. D. (1995). Professional experiences of therapists with physical disabilities [ Ph.D.] California School of Professional Psychology.

- Carew, L. (2009). Does theoretical background influence therapists’ attitudes to therapist self-disclosure? A qualitative study. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 9(4), 266–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733140902978724

- Charmaz, K. (1995). The body, identity and self: Adapting to impairment. The Sociological Quarterly, 36(4), 657–680. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.1995.tb00459.x

- Chernin, P. (1976). Illness in a therapist—Loss of omnipotence. Archives of General Psychiatry, 33(11), 1327–1328. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1976.01770110055004

- Coren, A. (2010). Short-term psychotherapy: A psychodynamic approach. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Cozby, P. C. (1973). Self-disclosure: A literature review. Psychological Bulletin, 19(2), 73–91. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0033950

- Cubbage, M. E., & Thomas, K. R. (1989). Freud and disability. Rehabilitation Psychology, 34(3), 161–173. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0091722

- Farber, B. A. (2006). Self-disclosure in psychotherapy. Guilford Press.

- Finlay, L. (1999). Applying phenomenology in research: Problems, principles and practice. The British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 62(7), 299–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/030802269906200705

- Fitzerman, B. (1996). Anger - The hidden destroyer: A psychodynamic approach with the physically disabled. Psychodynamic Counselling, 2(3), 356–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/14753639608411285

- French, S. (1995). Visually impaired physiotherapists: Their struggle for acceptance and survival. Disability & Society, 10(1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599550023697

- Freud, S. (1912). Recommendations to physicians practising psycho-analysis. In J. Strechey (Ed.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 12, pp. 111–120). Vintage.

- Freud, S. (1940). Splitting of the ego in process of defense. In J. Strechey (Ed.), The Standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 23, pp. 271–278). Vintage.

- Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Penguin.

- Goodley, D. (2011). Social psychoanalytic disability studies. Disability & Society, 26(6), 715–728. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2011.602863

- Groneck, J. R. (2013). Hidden in plain sight: Ordinary and extraordinary experiences of vision loss. MA Communication, Northern Kentucky University.

- Grzesiak, R. C., & Hicok, D. A. (1994). A brief history of psychotherapy and physical disability. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 48(2), 240–250.

- Hansen, J. A. (2008). Therapist self-disclosure: Who and when. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B, Sciences and Engineering, 69(3–B), 1954.

- Henretty, J. R., & Levitt, H. M. (2010). The role of therapist self-disclosure in psychotherapy: A qualitative review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(1), 63–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.09.004

- Hernandez, M. (2011). People with apparent and non-apparent physical disabilities: Well-Being, acceptance, disclosure and stigma [ Ph.D.] Alliant International University.

- Hobson, R. F. (1989). Forms of feeling: The heart of psychotherapy. Routledge.

- Jacobs, M. (1998). Seeing and being seen in the experience of the client and the therapist. European Journal of Psychotherapy & Counselling, 1(2), 213–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642539808402310

- Jacobs, M. (2004). Psychodynamic counselling in action. Sage.

- Jeffery, M. K., & Tweed, A. E. (2014). Clinician self-disclosure or clinician self-concealment? Lesbian, gay and bisexual mental health practitioners’ experiences of disclosure in therapeutic relationships [online]. Counselling and Psychotherapy. Retrieved August 21, 2014, from https://doi.org/10.1080/14733145.2013.871307

- Joseph, B. (1985). Transference: The total situation. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 66(4), 447–454.

- Jourard, S. M. (1971). The transparent self. Van Nostrand Reinhold.

- Kleege, G. (1999). Sight Unseen. Yale University Press.

- Kuusisto, S. (1998). Planet of the blind. Faber & Faber.

- Lane, R. C., & Hull, J. W. (1990). Self-disclosure and classical psychoanalysis. In G. Stricker & M. Fisher (Eds.), Self-disclosure in the therapeutic relationship (pp. 31–44). Plenum.

- Langs, R. (1998). Ground rules in psychotherapy and counselling. Karnac Books.

- Lemma, A. (2003). Introduction to the practice of psychoanalytic psychotherapy. Wiley.

- Mallinckrodt, B., & Helms, J. E. Effect of disabled counselors’ self-disclosures on client perceptions of the counselor. (1986). Journal of Counseling Psychology, 33(3), 343–348. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.33.3.343

- Maroda, K. J. (2010). Psychodynamic techniques: Working with emotion in the therapeutic relationship. Guilford Press.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. (1968). The visible and the invisible: Followed by working notes. Northwestern University Press.

- Miller, M. J. (1991). Counselors with disabilities: A comment on the special feature. Journal of Counseling and Development, 70(2), 347–349. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1991.tb01613.x

- Moore, J., & Jenkins, P. (2012). ‘Coming out’ in therapy? Perceived risks and benefits of self-disclosure of sexual orientation by gay and lesbian therapists to straight clients. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 12(4), 308–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733145.2012.660973

- O’Connell, C. T. (2011). Self-disclosure and the disabled psychotherapist: an exploration of how psychotherapists with visible physical disabilities or differences speak to their clients about these issues. Massachusetts School of Professional Psychology.

- Olkin, R. (2002). Could you hold the door for me? Including disability in diversity. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 8(2), 130–137. https://doi.org/10.1037/1099-9809.8.2.130

- Parker, C. A. (2011). Religious self-disclosure in informed consent describing a pragmatic and pluralistic psychodynamic approach. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering, 71(9–B), 5801.

- Peterson, Z. D. (2002). More than a mirror: The ethics of therapist self-disclosure. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, Spring, 39(1), 21–31. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.39.1.21

- Phillips, A. (2012). Missing out: In praise of the unlived life. Hamish Hamilton.

- Pizer, A. (2016). Do I have to tell my patients I’m blind? Psychoanalytic Perspectives, 13(2), 214 229. https://doi.org/10.1080/1551806X.2016.1156435

- Segal, J. (1993). Against Self-Disclosure. In W. Dryden (Ed.), Questions and answers on counselling in action (pp. 10–14). Sage.

- Segal, J. (1996). Whose disability? Countertransference in work with people with disabilities. Psychodynamic Counselling, 2(2), 155–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/14753639608411271

- Segal, J. (2006). Working psychodynamically with people with physical illness or disability. Psychodynamic Practice, 12(2), 127–129.

- Shakespeare, T. (1994). Cultural representation of disabled people: dustbins for disavowal? Disability & Society, 9(3), 283–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599466780341

- Shakespeare, T., & Watson, N. (2002). The social model of disability: An outdated ideology? Research in Social Sciences and Disability, 2, 9–28.

- Shapiro, J. L. (1990). Parameters of self-disclosure among psychodynamic and humanistic therapists [ Ph.D.] Long Island University.

- Smith, J. A., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method and research. Sage.

- Spencer, M. (2000). Working with issues of difference in supervision of counselling. Psychodynamic Counselling, 6(4), 505–519. https://doi.org/10.1080/13533330050197115

- Stanley, N., Ridley, J., Harris, J., & Manthorpe, J. (2011). Disclosing disability in the context of professional regulation: A qualitative UK study. Disability & Society, 26(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2011.529663

- Stricker, G., & Fisher, M. (1990). Self-disclosure in the therapeutic relationship. Plenum.

- Thurston, M. (2010). An Inquiry into the emotional impact of sight loss and the counselling experiences and needs of blind and partially sighted people. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 10(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733140903492139

- Thurston, M., McLeod, J., & Thurston, A. (2013). Counselling for sight loss: using systematic case study research to build a client informed practice model. The British Journal of Visual Impairment, 31(2), 102–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/0264619613481777

- Vick, A. L. (2007). (Un)settled bodies: A visual phenomenology of four women living with (in)visible disabilities [ Ph.D.] University of Toronto (Canada).

- Wachtel, P. L. (2011). Therapeutic communication: Knowing what to say when. Guilford Press.

- Watermeyer, B. (2012). Is it possible to create a politically engaged, contextual psychology of disability? Disability & Society, 27(2), 161–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2011.644928

- White, A. (2011). There by the Grace of…. Therapy Today, 22(5), 10–14.

- Wilson, S. (2003). Disability, counselling and psychotherapy: Challenges and opportunities. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Wilson, S. (2006). To be or not to be disabled: The Perception of Disability as Eternal Transition. Psychodynamic Practice, 12(2), 177–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/14753630600655538

- Winnicott, D. W. (1971). Playing and reality. Tavistock.

- Yoshino, K. (2007). Covering: The hidden assault on our civil rights. Random House.