ABSTRACT

In 2017 Scholl et al. highlighted a growing trend towards online courses in Psychotherapy & Counselling training. With the emergence of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, this growth has accelerated, with more training now taking place in an online setting. This study explored students’ experiences of remote learning on a Psychotherapy & Counselling training, with a particular focus on engagement and interaction in an online setting. A Thematic Analysis was carried out on the data and the central organising theme of Connection emerged. Three sub-themes were identified including, ‘Connection to Self’, ‘Connection to Others’ and ‘Connection to Lecturers’. Findings indicate that connection can be nurtured online through intentional and considered instruction. Findings also suggest that students miss the personal connections that face-to-face teaching affords with a preference for a blended approach to learning. The results are used to make specific recommendations for Counselling & Psychotherapy educators.

ABSTRAKT

Im Jahr 2017 wiesen Scholl et al. auf einen wachsenden Trend zu Online-Kursen in der Psychotherapie- und Beratungsausbildung hin. Mit dem Aufkommen der Coronavirus-Pandemie (COVID-19) hat sich dieses Wachstum beschleunigt, da nun mehr Schulungen in einer Online-Umgebung stattfinden (Helmcamp & Fox 2022, Lee et al 2022, Smith, 2022).

Diese Studie untersuchte die Erfahrungen der Studierenden mit dem Fernunterricht in einer Psychotherapie- und Beratungsausbildung, wobei der Schwerpunkt auf Engagement und Interaktion in einer Online-Umgebung lag. Anhand der Daten wurde eine thematische Analyse durchgeführt, und es kristallisierte sich das zentrale Leitmotiv von Connection heraus. Es wurden drei Unterthemen identifiziert, darunter “Verbindung zu sich selbst”, “Verbindung zu anderen” und “Verbindung zu Dozenten”

Die Ergebnisse deuten darauf hin, dass die Verbindung online durch bewusste und überlegte Anweisungen gepflegt werden kann. Die Ergebnisse deuten auch darauf hin, dass die Studierenden die persönlichen Verbindungen, die der Präsenzunterricht bietet, vermissen, da sie einen gemischten Lernansatz bevorzugen. Die Ergebnisse werden verwendet, um konkrete Empfehlungen für Beratungs- und Psychotherapiepädagogen zu geben.

RESUMEN

En 2017, Scholl et al. destacaron una tendencia creciente hacia los cursos en línea en formación en psicoterapia y asesoramiento. Con la aparición de la pandemia de coronavirus (COVID-19), este crecimiento se ha acelerado, y ahora se imparte más formación en un entorno online (Helmcamp y Fox 2022, Lee et al 2022, Smith, 2022). Este estudio exploró las experiencias de aprendizaje remoto de los estudiantes en una capacitación en Psicoterapia y Asesoramiento, con un enfoque particular en el compromiso y la interacción en un entorno en línea. Se llevó a cabo un análisis temático de los datos y surgió el tema organizador central de Conexión. Se identificaron tres subtemas: “Conexión con uno mismo”, “Conexión con los demás” y “Conexión con los profesores”. Los hallazgos indican que la conexión se puede fomentar en línea a través de una instrucción intencional y considerada. Los hallazgos también sugieren que los estudiantes echan de menos las conexiones personales que ofrece la enseñanza cara a cara con una preferencia por un enfoque mixto del aprendizaje. Los resultados se utilizan para hacer recomendaciones específicas para los educadores de Consejería y Psicoterapia.

ABSTRAIT

En 2017, Scholl et al. a souligné une tendance croissante vers des cours en ligne dans le domaine de la formation en psychothérapie et en counseling. Avec l’émergence de la pandémie de coronavirus (COVID-19), cette croissance s’est accélérée, avec davantage de formations désormais dispensées en ligne (Helmcamp & Fox 2022, Lee et al 2022, Smith, 2022). Cette étude a exploré les expériences d’apprentissage à distance des étudiants dans le cadre d’une formation en psychothérapie et conseil, avec un accent particulier sur l’engagement et l’interaction dans un environnement en ligne. Une analyse thématique a été réalisée sur les données et le thème organisateur central de Connexion a émergé. Trois sous-thèmes ont été identifiés, notamment « Connexion à soi », « Connexion aux autres » et « Connexion aux enseignants ». Les résultats indiquent que la connexion peut être entretenue en ligne grâce à un enseignement intentionnel et réfléchi. Les résultats suggèrent également que les étudiants ne bénéficient pas des liens personnels qu’offre l’enseignement en face à face et préfèrent une approche mixte de l’apprentissage. Les résultats sont utilisés pour formuler des recommandations spécifiques aux enseignants en counseling et en psychothérapie.

ΠΕΡΊΛΗΨΗ

Το 2017 ο Scholl και οι συνεργάτες του τόνισαν μια αυξανόμενη τάση προς τα διαδικτυακά μαθήματα κατά την εκπαίδευση στην ψυχοθεραπεία και τη συμβουλευτική. Με την εμφάνιση της πανδημίας του κοροναϊού (COVID-19), η ανάπτυξη αυτή επιταχύνθηκε, με περισσότερη εκπαίδευση να πραγματοποιείται πλέον σε διαδικτυακό περιβάλλον (Helmcamp & Fox 2022, Lee et al 2022, Smith, 2022). Η παρούσα μελέτη διερεύνησε τις εμπειρίες των σπουδαστών σχετικά με την εξ αποστάσεως μάθηση σε μια εκπαίδευση ψυχοθεραπείας και συμβουλευτικής, με ιδιαίτερη έμφαση στην εμπλοκή και την αλληλεπίδραση σε ένα διαδικτυακό περιβάλλον. Πραγματοποιήθηκε Θεματική Ανάλυση των δεδομένων και προέκυψε το κεντρικό οργανωτικό θέμα της Σύνδεσης. Προσδιορίστηκαν τρία επιμέρους θέματα, όπως «Σύνδεση με τον εαυτό», «Σύνδεση με άλλους» και «Σύνδεση με τους διδάσκοντες». Τα ευρήματα δείχνουν ότι η σύνδεση μπορεί να καλλιεργηθεί στο διαδίκτυο μέσω σκόπιμης και ενσυνείδητης διδασκαλίας. Τα ευρήματα υποδηλώνουν επίσης ότι οι φοιτητές χάνουν την προσωπική σύνδεση που προσφέρει η δια ζώσης διδασκαλία και προτιμούν μια μικτή προσέγγιση στη μάθηση. Τα αποτελέσματα χρησιμοποιούνται ώστε να παρέχουν συγκεκριμένες συστάσεις για εκπαιδευτές συμβουλευτικής & ψυχοθεραπείας.

Introduction

In March 2020, educators and students around the world were catapulted into an emergency remote teaching and learning situation due to the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. The training programmes under investigation here, which had traditionally been delivered face to face, were now delivered via Zoom. The core components of these programmes included Experiential Group Process (EGP), Counselling Skills and Theory. Given the nature of psychotherapy, where the qualities of relating and human connectedness are paramount the researcher was interested in exploring students’ experiences of teaching and learning during this time. There was a particular interest in ascertaining if the lack of face-to-face interaction impacted on engagement and relationship. With the sudden transition to remote teaching lecturers had little time for planning, preparation and design and had to rapidly develop the skills to work and teach remotely. The way in which a course structure facilitates the interaction and development of relationship is an important determinant of the success of online learning. Hence, the research was interested in examining what impact, if any, this transition had for participants.

Review of the literature

Research demonstrates that in remote learning environments, students report higher feelings of satisfaction when they feel connected and enjoy meaningful relationships (Snow & Coker, Citation2022; Chatterjee & Correia, Citation2020). Conversely, a lack of connection can lead to students feeling disconnected and alienated (Snow & Coker, Citation2022; Shin & Hickey, Citation2021) and ultimately dropping out (Helmcamp & Fox, Citation2022). Ozaydın Ozkara and Cakir (Citation2018) conducted a qualitative study exploring students’ experiences of methods that increase interaction and participation. The study involved 15 students working individually and 15 working collaboratively. Data were collated through interviews and reflective reports. The findings indicated that students who didn’t interact experienced feelings of loneliness and were more likely to drop out. Attrition rates are higher for online courses than face-to-face, which Murdock and Williams (Citation2011) attribute to a lack of connection. Greater interaction – both in and out of class – with peers and lecturers leads to more satisfying experiences of remote learning and higher retention rates (Lee et al., Citation2022; Sheperis et al., Citation2020).

A study by Toufaily et al. (Citation2018) examined perceptions of online learning via semi-structured interviews with 30 students enrolled in purely online, hybrid or face-to-face programmes. Findings indicate that students missed face-to-face interactions with their peers when studying online. Helmcamp and Fox (Citation2022) maintain that whilst online teaching may be more convenient and accessible, students miss the sense of community and personal connection that face to face classes provide.

In a study by Snow et al. (Citation2018) counsellor educators found it most challenging to consider how to transition traditional teaching styles to an online format. Hale and Bridges (Citation2020) conducted a phenomenological study amongst 6 counsellor educators across the USA to explore their experience of transitioning from classroom to online teaching. Data from semi-structured interviews was analysed and results showed that lecturers experienced difficulties in establishing interpersonal connection and an inability to engage students online. These findings correlate with those of Schreiber et al. (Citation2021) who contend that some instructors struggle with developing genuine connections when trying to engage psychotherapy students in experiential learning in a remote setting. Given that relationship is at the heart of psychotherapy – it is important to explore how connection can be facilitated in an online setting. This has the potential to provide much learning to help educators enhance connection when teaching remotely and to develop relational skills in the absence of face-to-face teaching.

Lee et al. (Citation2022) and Sheperis et al. (Citation2020) contend that much of the literature focuses on lecturers’ experiences of online education with a gap in literature focusing on the experiences of students. In the absence of such studies, this research aimed to understand students’ experience of engagement and interaction and ways in which this can be facilitated. In order to continue to develop, our understanding and choose the most effective approaches and pedagogy, whilst providing a meaningful experience for our students, it is important to look at students’ experiences.

Research methodology

Qualitative research provides a flexible and sensitive approach to exploring and understanding the subjective experience of the participants and how they make meaning (McLeod, Citation2011). Given the scope of this study, it was considered that a qualitative design could bring a deeper dimension of meaning to the topic under investigation as it is oriented toward discovery, developing our understanding further and following where the data leads (McLeod, Citation2011). The aim was to generate new insights and provide nuanced accounts (McLeod, Citation2011) into participants’ experiences.

Reflexive Thematic Analysis (RTA) (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, Citation2021) was used to identify and analyse patterns (themes) in meaning across the data set. It was considered a suitable approach as it offers a rigorous and systematic approach to data analysis and provides a clear set of steps to guide the researcher and to analyse a large body of data. Braun and Clarke (Citation2006, p. 77) claim that Thematic Analysis offers ‘an accessible and theoretically flexible approach to analysing qualitative data’ which can be utilized across a range of epistemologies and research questions.

RTA was particularly suitable in this instance as the researcher was interested in analysing patterns that were common to the participants. It also allowed for rich, contextualised research. An important component of RTA is acknowledgement of the researcher’s own position and it is considered an integral part of the process. The researcher’s experience and pre-existing knowledge is seen as something to be drawn upon as they influence and contribute to the research. The researcher was a lecturer on both programmes. This insider status (Brannick & Coghlan, Citation2007) gave her knowledge and insight into the programme along with a ‘lived experience’ of remote teaching on the programme thus positioning her well to gain an in-depth understanding of this topic. However, the researcher acknowledged that this insider status could also result in making assumptions or missing trends that were there. Keeping a reflexive journal along with research supervision provided the researcher with a forum whereby these blind-spots and biases could be highlighted and addressed. Participants were reassured that all experiences, both positive and negative, were valid and participation (or non-participation) didn’t impact their training status.

Participants

Purposeful sampling is particularly useful when the research requires participants who are knowledgeable or experienced in a particular phenomenon (Patton, Citation2002). As this research required participants to have knowledge and experience of both traditional classroom and remote learning, students on a BA Counselling & Psychotherapy and MA Integrative Psychotherapy program were selected. Both of these programs are delivered within an Irish University. Purposeful sampling was also considered a fit as the researcher wished to hear student’s in-depth accounts of their experiences of remote teaching.

Following approval from the University’s Ethical Board, all 41 students on the MA and BA programs were invited to partake in the study. Recruitment took place between January and March 2022. 4 students were from the BA program and 4 from the MA program responded to the invite. All 8 were interviewed, consisting of 1 male and 7 females. The average age was 50, with most of the contributors in their 40s and 50s and one in their 60s. Participants weren’t compensated for partaking in the study. None of the participants had any prior experience of remote teaching and learning. Whilst students on the BA and MA courses took different modules, experiential group, skills practice and theory were common to both programmes, hence ensuring a high level of homogeneity amongst identified themes. All of the participants were in individual psychotherapy and supervision online at this time.

Data collection and analysis

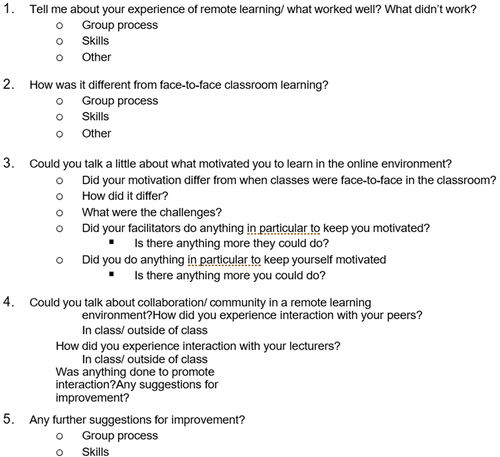

Data were collected via semi-structured interviews (SSIs) which were carried out over zoom. Each interview was recorded and lasted approximately 60 minutes. Appendix gives an overview of the interview questions.

The researcher followed Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006, Citation2021) systematic reflexive thematic analysis to explore participants’ experiences. The data were transcribed verbatim and transcripts read a number of times, making notes of observations, reflections and patterns that were striking. Each data item was given equal attention in the coding process. The coding process was thorough, inclusive and comprehensive and relevant extracts for each theme were collated and checked against each other and back to the original data set. This was an iterative process whereby the researcher constantly refined and revised earlier codes. Codes were clustered into possible themes or ‘Units of Analysis’. This was a very active phase whereby the researcher was actively engaging with the codes and attending to initial patterns and relationships that were evident across the range of codes. The researcher re-read the complete data set in order to ensure that the themes fitted and to code for any additional data that may have been overlooked initially. This stage also involved giving concise and accurate names to the emerging themes. Once a complete set of themes and sub-themes were identified the story of the data was written.

Findings

Following analysis of the data, Connection was considered to be the central organising concept. All data that related to this central theme were further analysed and yielded three themes as follows:

Connection to Self

Connection to Others

Connection to Lecturers

The following section will discuss these themes with a selection of transcript in italics.

Theme 1: Connection to self

Allowing oneself space to let things resonate is an important feature of group process, and this was considered to be easier to do when online. All participants enjoyed ‘the quiet time’ that was afforded them after an online class. They felt that being online allowed them more space to reflect on their own process as it necessitated having to ‘sit with stuff’ from which they could be more easily distracted when in the classroom. This in turn enhanced their interaction with others, with one participant describing it as ‘more selective and profound’. The majority of participants liked studying theory online and felt more connected to their own learning when online without the distractions of those around them. In the words of one participant: I sometimes get distracted by people, so the fact that my computer is in front of me and seeing the lecture notes in front of me I feel like as if I can really absorb myself in the information that’s coming. Being on their own in the online EGP group allowed them to stay with their own process, to stay grounded and connect to themselves. During the tea-break each participant tended to journal, reflect on what was happening for them or go for a short walk alone. If in the classroom students said they would immediately speak to someone they know or engage in chit-chat which tended to distract them from their own process.

Theme 2: Connection to others

All of the participants missed the camaraderie of being together in the same physical space and there was an awareness that whilst deep process work can take place when working online the physical presence of being together changes everything. The interpersonal interactions and the regulation that happens face to face was missed. When in the classroom students spend time together informally and this time is treasured. One participant described how the informal elements, the spontaneous being together, enhances the formal elements. Remote learning doesn’t allow for these informal interactions in the same way and this was considered to impact on the full experience. You don’t get this three or four minutes of meeting somebody in the corridor … the coffee, the cookies, the chats. One participant said she missed out on the physical presence when classes were online such as feeling energy in the room, and . sensing things that you’re not aware of when you’re on a screen. Because the social element was missing some students felt that they didn’t develop relationships in the same way they would have if they were in the classroom. Many participants reported that the connections they had made prior to lockdown sustained them and they found it easier to connect to the people they had already met face to face in the classroom. All students enjoyed the connection and the interaction which zoom breakout rooms afforded them. Breakout rooms were considered to be a vitally important medium through which students could connect with each other.

Some participants reached out and connected with each other in various ways – such as study groups and monthly Zoom meetings with a mixed response. There was much agreement that if such groups were organised by the College, students would feel more accountable and be more committed to showing up. Participants felt that if direction to attend isn’t coming from the college then we don’t have to be there … there’s kind of a looseness about it. Therefore, having a structure imposed on it by the College would facilitate it to work better. For remote learning, Participants felt strongly that it was important to integrate the social element into the fabric of the course.

Some of the participants described how disconnect can happen online, particularly once they turn their cameras off and are left on their own. One participant described how in the classroom they might make real eye contact with someone and how supportive this can be. Connecting, even for a brief moment with someone, looking to a friend for that connection, which cannot happen in the same way online. There was a sense that being physically together in the room calls for more interaction and it is easier to disconnect and hide behind the screen. One participant acknowledged that they were more inclined to ‘hang back a little bit’ which was easier to do online. Another participant admitted that it’s easier to opt out of communication with others when online.

Theme 3: Connection to lecturers

When studying remotely some students found they had little opportunity to talk privately or formally to lecturers. Most of the private conversations took place over email. Some participants had the opportunity to have private conversations or one-on-one sessions with their lecturer over the course of the year, and they found this very beneficial. The impact of these were felt keenly as described below:

Being one-on-one with a tutor that is something I find really motivating it’s feeling that someone is really interested.

So, at the end of third year … I actually had a chat with [lecturer] and it was so lovely. Genuinely so lovely, to just connect on a personal level. And I hadn’t realized how much maybe I had missed that prior.

Whilst students got feedback from their lecturers, they said they would have welcomed more formal check-in sessions from time to time. However, the majority said they are very reluctant to reach out to lecturers when working in a remote setting. Students described how beneficial break out rooms were to interact with the lecturers. One participant explained that because the lecturer ‘visited’ the rooms she didn’t lose out on the personal connection and felt that this interaction compensated for the loss of the physical presence of the lecturer.

Discussion

The overarching theme that emerged from the analysis was that of Connection. We know from the research that a sense of connection and community are linked with better learning outcomes and dynamic interactions lead to improved and deeper learning (Snow & Coker, Citation2022; Sheperis et al., Citation2020; Murdock & Williams, Citation2011). The following section will discuss the research question in light of these findings linking them with existing literature and exploring their implications for professional practice.

Being alone together

Findings indicate that remote learning afforded students more time to connect with their own process and offered them a distraction-free space for reflection and study. Being alone together (Kostenius & Alerby Citation2020, p. 6) facilitates students to connect more readily with self which is a crucial component of any psychotherapy training. Garrison (Citation2020) maintains that any valuable learning experience necessitates the fusion of reflection with discourse and is consistent with Ally’s (Citation2008) recommendations for successful online teaching by facilitating deep processing and promoting meaningful learning and interaction.

Alerby and Alerby (Citation2003) discuss the valuable role that silence plays in the process of reflection within teaching and learning. Ollin (Citation2008) promotes ‘Silent Pedagogy’ and maintains that silence offers broader and deeper learning, which in turn supports collaborative work. Affording students more time to think can promote deeper thought and encourage critical listening which in turn can have a significant impact on how people interact with each other. Zembylas and Michaelides (Citation2004, p. 205) state that ‘Educators have the responsibility to create a safe place for our students by valuing silence and by incorporating into our classrooms the time and space necessary to experience the pedagogical values of silence’. Unlike face-to-face classrooms where silence may need to be imposed on a group, silence can form the natural fabric of the online learning space. Silences can arise naturally at the beginning of class as the tutor waits for everyone to join the call, during break times and at the end when everyone turns off their microphones. Instead of viewing these silence as gaps in the teaching they could instead be embraced as an intentional strategy in online teaching, thus transforming the online environment into one where the silences and spaces are used to foster self-reflection and meaningful interactions thus laying the groundwork for a more collaborative approach.

Fostering social connection

It would appear that relationships developed online are not as deep as those formed in the face to face classroom. This is consistent with Toufaily et al. (Citation2018) report that students interacted more with their peers in offline settings and missed engaging and being with them when studying online. Given that learning is not just a cognitive but also a social process (Hodges et al., Citation2020) there is a responsibility on educators to focus not just on course content and delivery but also on the ways in which social connection and interaction is fostered. Consistent with the findings, research demonstrates that activities which promote connection with self, others and lecturers have a positive impact on engagement (Smith, Citation2022; Shin & Hickey, Citation2021; Chatterjee and Correia, Citation2020). The intentional use of such activities and interactions is critical in a remote learning environment to ward against feelings of disengagement, disconnection, isolation and alienation (Chatterjee & Correia, Citation2020; Scholl et al., Citation2017).

Without the physical presence of each other, there is more scope for disconnection when studying remotely. Garrison (Citation2020) fears that with the growth in online education, learners might isolate themselves by choice and reject shared thinking, challenge and critique. Rolins et al. (Citation2022) refer to videoconferencing fatigue as a new phenomenon experienced by individuals when interactions with others are minimal over a long period of time. It is important therefore that educators are attending to pedagogies that nurture relationship when designing courses. The effective use of instructional tools and promotion of a positive online culture are important elements of successful online learning (Harrington & Zakrajsek, Citation2017). Given that a reliance on online platforms is likely to continue into the future, efforts to improve online engagement and connection is paramount. Online programmes need to embrace instructional technology that promotes relationship-building activities in order to foster connection and engagement (Rolins et al., Citation2022).

Intentional engagement

The findings point to the importance of making an intentional effort to nurture student-tutor relationships. Activities and assignments that consistently promote interaction and connection need to be built into online training (Haddock et al., Citation2020). In order for optimal learning to take place in a remote teaching environment, intentional engagement and meaningful connections need to be established between students and their teachers (Hale & Bridges, Citation2020). An approach to teaching that intentionally responds to the learner in growth-producing ways are qualities that promote optimal online learning (Scholl et al., Citation2017, p. 208). Haddock et al. (Citation2020) point to the challenges that this can pose for lecturers who struggle with providing intentional and personalized instructional interactions. It requires additional and diverse approaches in order to promote connection and simply transferring material used in the face-to-face setting is not sufficient (Haddock et al., Citation2020).

Blended learning

The findings from this study correlate with the research which indicates that students report a more fulfilling online experience when they also have face-to-face contact with their peers (Helmcamp & Fox, Citation2022; Sheperis et al., Citation2020). This has very important implications for online and hybrid delivery in Counselling and Psychotherapy training going forward. Hybrid or blended learning is defined as learning that integrates both face-to-face and online teaching. Graham (Citation2019, p. 19) states that ‘evidence shows that many learners value both the richness of interactions in a face-to-face environment and the flexibility, convenience, and reduced costs associated with online learning’. This was certainly borne out in the current research with all participants recommending a blended approach to learning going forward. A blended approach can support learners by tapping into various learning styles and hence promoting successful teaching experiences for students (Harris, Citation2018). Through careful planning and implementation blended learning has the potential to create connected learning communities. The current research strongly supports the possibility for a robust blended teaching and learning experience within a Psychotherapy training.

Recommendations and limitations

The current research is not without its limitations. It was limited by the homogenous sample as all participants were from the same University and studying within the same department. Furthermore, the small sample size of eight means that the findings cannot be generalised. It would be very useful to expand this study to include other psychotherapy trainings to extend the findings beyond this context. The average age of participants in this study was 50, with the majority in their 40s and 50s which would skew the data older. Hence, it would be interesting to compare the findings in this study with the experiences and perceptions of remote learning within a younger cohort.

As we have moved into a post-pandemic era it would be interesting to explore students’ experiences of coming back into the classroom environment and enquire into how this transition has been. Given that the majority of participants agreed that a blended approach was the way forward more research is needed to assess best practice in blended learning. Whilst the longer-term impact of the pandemic has yet to be determined, in the short term it would appear that students adapted to this digital world. It would be interesting to follow up with students who completed their training exclusively online to explore what/if any implications this has had for their practice.

Conclusion

One of the most salient lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic is that just as the way in which we do therapy has changed so too has the way in which we teach it. Haddock et al. (Citation2020) and Sheperis and Nazzal (Citation2022). As we move forward, it is apparent that this shift to remote learning is not just an alternative to facetoface, but increasingly becoming part of what we do. In this constantly evolving space, educators are left to determine best practice in psychotherapy & counselling education and investigate the technology used, the pedagogy and the methods employed.

We now have the opportunity to develop the teaching methods and skills that best suit Psychotherapists of the 21st century. As borne out in this study, it is not just about the course content and delivery but also the social connection and interactions that are cultivated. The richness of face-to-face classroom interaction coupled with the affordances of an online learning environment make a blended approach to psychotherapy & counselling training a very appealing option. This research highlights the way in which a successful collaborative environment can be created through attention to connections, which are optimally attained in a hybrid setting. The focus must be on both instruction and the relational and social element and the overall educational environment needs to be designed with this in mind.

Acknowledgments

All participants signed a written consent form to participate.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

All documents and files are stored on a secure password-protected computer to which the researcher has sole access. These documents are available on request.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Geraldine Sheedy

Geraldine Sheedy is a Counselling Psychologist and Psychotherapist registered with the Psychological Society of Ireland and accredited with the Irish Association for Counselling & Psychotherapy. Geraldine completed her Doctorate in Counselling Psychology and Psychotherapy at Metanoia Institute in London. Geraldine is a senior lecturer on the Counselling & Psychotherapy training programme at Munster Technological University, Cork, Ireland. She has a particular interest in the training and education of Psychotherapists with a particular focus on pedagogy and best practice. Geraldine also runs a small private practice specialising in a body approach to Psychotherapy along with providing supervision and consultation

References

- Alerby, E., & Alerby, J. E. (2003). The sounds of silence: Some remarks on the value of silence in the process of reflection in relation to teaching and learning. Reflective Practice, 4(1), 41–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/1462394032000053503

- Ally, M. (2008). Foundations of educational theory of online learning. In T. Anderson & F. Elloumi (Eds.), Theory and practice of online learning (pp. 3–33). Athabasca University.

- Brannick, T., & Coghlan, D. (2007). In defense of being “native”: The case for insider academic research. Organizational Research Methods, 10(1), 59–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428106289253

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. SAGE Publications.

- Chatterjee, R., & Correia, A. P. (2020). Online students’ attitudes toward collaborative learning and sense of community. American Journal of Distance Education, 34(1), 53–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2020.1703479

- Garrison, D. R. (2020). From independence to collaboration. In M. F. Cleveland-Innes & D. R. Garrison (Eds.), An introduction to distance education: Understanding teaching and learning in a new era (pp. 13–24). Routledge.

- Graham, C. R. (2019). Current research in blended learning. In M. G. Moore & W. C. Diehl (Eds.), Handbook of distance education (4th ed., pp. 173–188). Routledge.

- Haddock, L., Cannon, K., & Grey, E. (2020). A comparative analysis of traditional and online counselor training program delivery and instruction. The Professional Counselor, 10(1), 92–105. https://doi.org/10.15241/lh.10.1.92

- Hale, N., & Bridges, C. W. (2020). The experiences of counselor educators transitioning to online teaching. Journal of Educational Research and Practice, 10(1), 145–160. https://doi.org/10.5590/JERAP.2020.10.1.10

- Harrington, C., & Zakrajsek, T. (2017). Dynamic lecturing: Research-based strategies to enhance lecture effectiveness. Stylus.

- Harris, C. A. (2018). Student engagement and motivation in a project-based/blended learning environment [ Publication No. 10827819. Doctoral Dissertation, Azusa Pacific University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

- Helmcamp, W., & Fox, T. (2022). Creating connection with online learners. Journal of Technology in Counsellor Education and Supervision, 2(2), 25–29. https://doi.org/10.22371/tces/0023

- Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T., & Bond, A. (2020). The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. EDUCAUSE Review. Retrieved January 05, 2023, from https.//er.educause.edu/articles/2023/3/the difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning

- Kostenius, C., & Alerby, E. (2020). Room for interpersonal relationships in online educational spaces – a philosophical discussion. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 15(sup1), 1689603. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2019.1689603

- Lee, J., Lee, D., Nam, S., Jeong, J., & Na, G. (2022). Dynamics of online engagement: Counseling students’ experiences and perceptions in distance learning. Journal of Technology in Counselor Education and Supervision, 2(2), 42–45. https://doi.org/10.22371/tces/0027

- McLeod, J. (2011). Qualitative research in counselling & psychotherapy. Sage.

- Murdock, J. L., & Williams, A. M. (2011). Creating an online learning community: Is it possible? Innovations in Higher Education, 36, 305–315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-011-9188-6

- Ollin, R. (2008). Silent pedagogy and rethinking classroom practice: Structuring teaching through silence rather than talk. Cambridge Journal of Education, 38(2), 265–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057640802063528

- Ozaydın Ozkara, B., & Cakir, H. (2018). Participation in online courses from the students’ perspective. Interactive Learning Environments, 26(7), 924–942. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2017.1421562

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Rolins, D., Herbert, L., & Wright, G. (2022). Logged in, zoomed out: Creating & maintaining virtual engagement for counselor education students. Journal of Technology in Counselor Education and Supervision, 2(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.22371/tces/0016

- Scholl, M. B., Hayden, S., & Clarke, P. B. (2017, October). Promoting optimal student engagement in online counseling courses. Journal of Humanistic Counseling, 56(3), 197–210. https://doi.org/10.1002/johc.12053

- Schreiber, Z., Herrick, R. J., & Lucietto, A. M. (2021). Active experiential learning at a distance. School of Engineering Education Faculty Publications, Paper 73. http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/enepubs/73

- Sheperis, D. S., Coker, J. K., Haag, E., & Salem-Pease, F. (2020). Online counselor education: A student-faculty collaboration. The Professional Counselor (Greensboro, N.C.), 10(1), 133–143. https://doi.org/10.15241/dss.10.1.133

- Sheperis, D., & Nazzal, K. (2022). The great pivot. The profession of counselling has changed. Has your pedagogy. Journal of Technology in Counsellor Education and Supervision, 2(2), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.22371/tces/0017

- Shin, M., & Hickey, K. (2021). Needs a little TLC: Examining college students’ emergency remote teaching and learning experiences during CORONA VIRUS (COVID-19). Journal of Further and Higher Education, 45(7), 973–986. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2020.1847261

- Smith, L. (2022). Creating meaningful connections in online counselor education. Journal of Technology in Counselor Education and Supervision, 2(2), 30–32. https://doi.org/10.22371/tces/0024

- Snow, W. H., & Coker, K. (2022). Distance counselor education: Past, present, future. The Professional Counselor, 10(1), 40–56. https://doi.org/10.15241/whs.10.1.40

- Snow, W. H., Lamar, M. R., Hinkle, J. S., & Speciale, M. (2018). Current practices in online counselor education. The Professional Counselor, 8(2), 131–145. https://doi.org/10.15241/whs.8.2.131

- Toufaily, E., Zalan, T., & Lee, D. (2018). What do learners value in online education? An emerging market perspective. E-Journal of Business Education and Scholarship of Teaching, 12(2), 24–39.

- Zembylas, M., & Michaelides, P. (2004). The sound of silence in pedagogy. Educational Theory, 54(2), 193–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0013-2004.2004.00005.x

Appendix

Semi-structured interview schedule