ABSTRACT

Historically, non-Indigenous researchers have contributed to colonisation by research based on Western positivistic philosophical frameworks. This approach led to disembodying knowledge from Indigenous people’s histories, worldviews, and cultural and social practices, thus perpetuating a deficit-based discourse which situates the responsibility of problems within Indigenous peoples and ignores the larger socio-economic and historical contexts in which problems are rooted. Rectifying this position requires decolonising Western positivistic research by shifting to basing research on social constructionist paradigms that lead to strength-based approaches. Based on our experiences gained exploring disaster risk reduction perspectives with two remote Indigenous communities in Australia and Pakistan, we suggest in this conceptual paper that a synergy of systems theory and symbolic interactionism offers an appropriate philosophical lens to non-Indigenous researchers for gaining a more comprehensive and deeper understanding of Indigenous holistic and relational perspectives, experiences, interpretations and actions/interaction. Research based on these philosophical worldviews promotes a strength-based approach that aligns with and empowers Indigenous ways of facilitating health and wellbeing. We offer our experiences of utilising these two frameworks and of how they could assist other non-Indigenous researchers to discover valuable insights into Indigenous perspectives and interpretations that might otherwise be ignored or neglected.

Introduction

Historically, knowledge about IndigenousFootnote1 peoples has been collected, documented and disseminated based on positivistic philosophical worldviews that led to using research approaches that not only imposed Western frameworks on Indigenous peoples but also disembodied and separated knowledge from Indigenous people’s histories, worldviews, and cultural and social practices (Datta, Citation2018; Kukutai & Walter, Citation2015; Nakata, Citation2007). Such research paradigms, contexts and practices ignore social construction of Indigenous realities and impose social hierarchies, linearity, abstraction and objectification, and convert knowledge into numerical values to measure them objectively in ways that are inconsistent with and obscure traditional socio-cultural knowledges, beliefs and practices (Nakata, Citation2007; Walter, Citation2015). Once realities are converted into numerical data, Indigenous worldviews, experiences and actions/interactions are limited to objective aspects, caught in a number-bind, and that come to always being viewed through a deficit lens (Walter & Andersen, Citation2013). Deficit discourses narrowly situate problem causality within affected individuals or communities and ignore the larger socio-economic and historical contexts in which problems are rooted (Kukutai & Walter, Citation2015).

Rectifying this position and to facilitate movement towards decolonising Western positivistic research, it is important to shift from a deficit discourse, that emphasises what Indigenous peoples do not know or cannot do, to a strength-based approach which purposefully utilises worldviews, knowledges and capabilities of Indigenous peoples (Kukutai & Walter; Walter, Citation2015). To develop Indigenous strength-based research, the approaches adopted must be capable for facilitating an appreciation of the interdependent relationships between peoples, land, environment, history, collective agency, Indigenous languages and traditions which support Indigenous health and wellbeing by holistically including the spiritual, emotional, and ecological aspects implicit within these processes (Smith et al., Citation2018).

In addition to enhancing the cultural validity and utility of research with Indigenous peoples, culturally inclusive research has important theoretical implications, including its use in supporting the critical exploration of the cultural universality of theories (Matsumoto & Juang, Citation2008; Norenzayan & Heine, Citation2005). As introduced above, this understanding cannot be pursued using mainstream positivist and postpositivist approaches. While the magnitude of cultural differences between most Western researchers and Indigenous peoples makes it challenging to develop a comprehensive understanding of diverse Indigenous cultures (Matsumoto & Juang, Citation2008), it may be possible to facilitate a gradual shift towards increasing the understanding by drawing on Western research traditions that support this bridge-building. This approach can be further supported by Western researchers collaborating with Indigenous co-researchers. These approaches are the subject of this conceptual paper, which commences with identifying frameworks we have found useful for bridging worldviews.

We propose that non-Indigenous researchers can draw upon two social constructionist Western philosophical frameworks, systems theory and symbolic interactionism, to decolonise research and promote research with Indigenous peoples and communities in ways that value Indigenous spiritual, ecological, sociocultural, historical and political contexts through a strength-based lens. Systems theory and symbolic interactionism can assist non-Indigenous peoples to gain a more comprehensive and deeper understanding of the relational and holistic dimensions of Indigenous perspectives, experiences, interpretations and actions/interactions.

We argue that the basic philosophical assumptions of systems theory and symbolic interactionism share aspects with the Indigenous holistic and relational ontologies and epistemologies. Specifically, and importantly, both frameworks highlight how reality is co-constructed through iterative dualistic interactions between and within human and ecological systems. Consequently, gaining an understanding of the philosophical assumptions these frameworks suggest can enable researchers to respect and appreciate diverse Indigenous contexts, prioritise geographic and cultural diversity, ensure local Indigenous spatiality, facilitate other ways of knowing, and promote Indigenous participation in Indigenous research, consistent with a decolonising research agenda.

We integrated these two frameworks in our research to holistically, contextually and temporally explore and identify the historical and contemporary factors and processes that influence disaster risk reduction beliefs and practices in two remote Indigenous communities – one in Australia, and one in Pakistan. We aimed to develop a comprehensive and in-depth understanding of Indigenous-grounded community-based disaster risk reduction and recovery specific to the Australian and Pakistani contexts. This paper unveils the unique but unexplored potential of both frameworks to facilitate creating an interface between Indigenous and non-Indigenous ontologies, epistemologies and methodologies that afford a space for learning and enrichment for academics from both cultures (Gray & Oprescu, Citation2016; Nakata, Citation2007).

We start our discussion by locating and positioning ourselves in Indigenous research. We then briefly provide an overview of the holistic, relational, emergent and adaptive aspects of Indigenous worldviews. The discussion then turns to how systems theory and symbolic interactionism share some common ontological and epistemological aspects with Indigenous worldviews. Next, we elaborate how utilising a synergy of systems theory and symbolic interactionism assisted us in gaining a unique perspective to understand how holistic Indigenous worldviews, knowledges, experiences and actions/interactions influence disaster risk reduction in the two Indigenous communities we researched with.

Researchers’ positionality

In Indigenous research methodology, it is essential for researchers to question systems of oppression and to identify the values and experiences that guide them to undertake the research (Kovach, Citation2010). The primary author, Tahir Ali, comes from Pakistan, a developing country formerly part of the Indian Sub-Continent and a British colony which gained its independence in 1947. With this background, Tahir identifies himself as a ‘colonised other’, who suffered European colonisation and still experiences its impacts similar to Indigenous peoples and communities (Chilisa, Citation2012). Hence, Tahir’s experiences are grounded in discrimination, racism, and underprivileged conditions as neo-colonial practices in his country. The neo-colonial and ‘colonised other’ experiences of Tahir enabled him to relate to and better understand the nuances of the participant communities and their perspectives and experiences embedded in colonisation processes in both countries.

However, Tahir’s non-Indigenous background constrained his understanding of the worldviews and knowledge systems Indigenous participants in both communities shared. To address this limitation, Tahir used several strategies including extensive reading on Indigenous worldviews; having Indigenous supervisors, Elaine Lawurrpa Maypilama from Australia and Noor Jehan from Pakistan, leading the research process; having non-Indigenous supervisors with extensive experience working with Indigenous peoples in different countries; living in each Indigenous community for several weeks (twelve weeks in Pakistan and six weeks in Australia); working together with local Indigenous co-researchers in each community; being trained by Indigenous supervisors in culturally responsive research (including local Indigenous communication and research protocols), recruitment, interpretation, data collection and analysis; discussing the findings with the communities (member checking); attending seminars pertaining to Indigenous studies; and in-depth study of the National Health and Medical Research Council Australia (Citation2018) and The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (Citation2012) guidelines for Indigenous research.

Maypilama is a Yolŋu elder and belongs to Warramiri clan from Galiwin’ku community, in Northern Territory of Australia. She is an award-winning Indigenous researcher with over 40 years’ experience with different institutions and organisations Australia wide. Her areas of research experience include nutrition, child and maternal health, hearing loss, sign language, chronic disease, intercultural communication, child development and linking health and education. Noor is a Pukhtun elder, belongs to the Marwat tribe from Karak, Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa (KPK), Pakistan. Noor is the first woman professor from KPK and is the Director of the Centre for Disaster Preparedness and Management in University of Peshawar, Pakistan. Both Indigenous supervisors led the process of co-designing the project based on relationship and participatory research approaches to decolonising research with Indigenous communities (Chilisa, Citation2012; Denzin & Linclon, Citation2008; Kovach, Citation2009; Kurtz, Citation2013). Through participation and dialogue between researchers and community members, the project honoured a respectful commitment for ongoing knowledge development and sharing that benefits the lives of Indigenous peoples (Kovach, Citation2009; Kurtz, Citation2013).

The non-Indigenous supervisors, Petra Buergelt, Douglas Paton and James Smith are German, Scottish and Australian respectively. Petra and Douglas have been living and working in Australia for over 20 years. Petra has been adopted by Yolŋu. She deeply relates to Indigenous peoples in many ways as she grew up in nature and in a collectivistic social system (East Germany) that was colonised by capitalist West Germany, thinks holistically and is spiritual. She has been working with diverse Indigenous communities in Australia and Taiwan using a synergy of the salutogenic paradigm, systems theory, symbolic interactionism and narrative theory as philosophical lens and a merger of Indigenist, participatory action research, ethnography and grounded theory as methodologies. Petra and James possess extensive Indigenous social, health, and education research experience in Australia and worldwide. Their research experiences are grounded in Indigenist and decolonising research approaches, primarily using participatory action research methods alongside Indigenous peoples. Petra, Douglas and James deeply value and respect Indigenous worldviews and work with Indigenous researchers to support their efforts to overcome ensuing colonial oppression and liberate themselves.

Indigenous worldviews

Across histories and cultures worldwide, Indigenous peoples hold metaphysical, unified and egalitarian worldviews that are holistic, relational, emergent and adaptive, and that comprise inter-dependent ecological/environmental, physical, emotional and spiritual elements (Chilisa, Citation2012; Kovach, Citation2009). These worldviews regarding the origin and nature of the universe, reality and knowledge differ fundamentally from the prevailing totalitarian, positivistic, rationalist, mechanist and reductionist Western worldviews (Buergelt et al., Citation2017; Datta, Citation2018). For Indigenous peoples, all creatures arise from the essential creative life force or spirit and share the universal consciousness of the primary creative force (Buergelt et al., Citation2017). Thus, while all creatures are unique visible manifestations of the primary creative life force, they all are one, equal, intertwined and related in Indigenous worldviews. These creatures in the form of physical visible and spiritual invisible are linked inextricably and continuously interact to influence Indigenous worldviews (Chilisa, Citation2012; Poonwassie, Citation2001). Hence, Indigenous worldviews are socially constructed. These worldviews continuously transform, evolve, adapt and expand through the development of new understandings and perspectives thus making Indigenous realities emergent, subjective and adaptive (Chilisa, Citation2012).

The intimate relationship and connectedness of Indigenous peoples experience with nature as a result of their worldviews promote eco-centric beliefs. Indigenous peoples feel responsible for living in harmony with nature and creating a culture that reciprocally protects and nourishes life in all its forms (Buergelt et al., Citation2017; Poonwassie, Citation2001). Because of their eco-centric belief systems, Indigenous peoples see themselves as custodians of knowledge that promote harmony between humans and all other creatures. Indigenous worldviews, knowledges and cultural practices are crucial roles in healing the damage caused by contemporary Western worldviews and linked anthropocentric practices (Buergelt & Paton, Citationin press; Buergelt et al., Citation2017).

The intimate relationship Indigenous peoples have with nature, and their continuous interactions in and with the natural environment in everyday life, form the basis of Indigenous lived experiences (Berks & Berks, Citation2009). Based on this interconnected worldview, every Indigenous community member – including elders, women, men, youth, and children – hold and contribute towards Indigenous knowledges. This knowledge continuously transforms, evolves and adjusts as it passes from generation to generation. Collective, skilful, diligent and systematic observing, experiencing, reflecting and learning through trial and error over at least some 50,000 years in the case of Australian Indigenous peoples make Indigenous knowledges and practices an adaptive learning process that is continuously refining sophisticated knowledge systems (Berks & Berks, Citation2009). These adaptations to changing environments and contexts change the narratives of Indigenous peoples, revealing how Indigenous worldviews are socially constructed (Stewart, Citation2009). For example, Berks and Berks (Citation2009) quote an example from the Arctic region, where Northern Indigenous peoples adjust their lifestyles based on their observations about abnormalities in animal behaviours due to climate change. Reality from an Indigenous viewpoint, therefore, is not generalisable into one common reality as it is socially constructed through a dynamic process; subjective, mind-dependent; specific to the context, time and space; and changes over time in response to dynamic environmental conditions (Chilisa, Citation2012).

Historically, the holistic, relational, adaptive and subjective Indigenous worldviews have largely been ignored by non-Indigenous researchers, who have commonly used Western positivistic linear, static, objective, inflexible and individualistic research approaches especially surveys and experiments (Gray & Oprescu, Citation2016; Wilson, Citation2008). However, a more overt movement towards Indigenous empowerment and self-determination has challenged non-Indigenous researchers to think and act differently when conducting Indigenous research, and to accept emerging fields of Indigenous inquiry as valid and legitimate within themselves (Gray & Oprescu, Citation2016). There is now a growing body of literature advocating to decolonise Western research to prioritise Indigenous worldviews, knowledges and practices, and learn from Indigenous peoples (Shahid et al., Citation2009) – a process generally referred to as the ‘decolonising research approach’ (Chilisa, Citation2012; Denzin & Linclon, Citation2008; Smith, Citation2012; Wilson, Citation2008).

Decolonising research approach

A central focus of decolonising research is the exposing and dismantling of colonial research practices to ensure that Indigenous peoples’ perspectives are not examined through Western hegemony and ideology (Denzin & Linclon, Citation2008; Smith, Citation2012). Most Western research uses positivistic philosophical frameworks and methodologies and methods for collecting, analysing and representing findings which suppress and misrepresent other perspectives, knowledges and practices especially those of Indigenous peoples (Chilisa & Tsheko, Citation2014: Smith, Citation2012). The exposing and dismantling colonial research interrupts and destabilises power imbalances inherent in colonially oriented research and promote Indigenous peoples’ worldviews, knowledges, practices, rights and data sovereignty (Datta, Citation2018; Smith, Citation2012).

To decolonise Western positivistic research, Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers have started using critical, more democratic and social justice oriented Western philosophical frameworks to better understand and liberate Indigenous holistic and relational worldviews, perspectives and knowledges (Chilisa, Citation2012). Diverse critical and emancipatory Western social constructionist philosophical paradigms are assisting with the reviving and strengthening of Indigenous worldviews and approaches to knowledge (Buergelt & Paton, Citationin press; Denzin & Linclon, Citation2008; Foley, Citation2003). These philosophical frameworks facilitate non-Indigenous researchers’ ability to perceive reality, including Indigenous reality, as being historically bound and constantly changing depending on social, political, cultural and power-based influences (Chilisa, Citation2012). These philosophical worldviews can facilitate non-Indigenous researchers accessing Indigenous approaches to knowledge (Foley, Citation2003) and conducting research with Indigenous peoples in culturally respectful and responsive ways (Smith et al., Citation2018).

Systems theory and symbolic interactionism are two of these critical and emancipatory philosophical paradigms. Systems theory is an interdisciplinary philosophical paradigm which approaches every system in nature and society ‘as a whole’ by focusing on the interactions and interrelationships among all elements of its subsystems (Mele et al., Citation2010). Systems theory was utilised in diverse research fields that developed specific conceptualisations of systems theory, including behavioural systems theory, adaptive systems theory, developmental systems theory, family systems theory, and ecological systems theory. For our research, we adopted the ecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979). According to ecological systems theory human beings are embedded in multiple nested systems and human development is the result of the complex interactions between and within these systems over time (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979). However, systems theory does not specify how exactly these interactions occur.

Symbolic interactionism (Blumer, Citation1969) sheds light onto the specific nature of the interactions within and between systems. Blumer suggests that human beings subjectively construct the meaning of what they experience and then act based on these meanings. These meanings arise from the interaction of interpretive, reflective processes and linguistic and behavioural interactions with and between other people within the diverse systems people live in and constantly interact with. Interpretations and social interactions interact in a dialectic, reciprocal and transactional process over time. That is, people continuously construct society and society continuously constructs peoples’ perceptions and their experiences.

Synergising ecological systems theory and symbolic interactionism in our research guided our exploration of the diverse factors and processes influencing Indigenous disaster risk reduction at different levels of the system and interactions between and among them over time. Specifically, the synergy suggested the benefits of examining how the diverse factors played out in the lived experiences of Indigenous peoples over time, how Indigenous peoples interpreted these experiences, what factors influenced these interpretations, how interpretations changed over time, and how the interpretations influenced disaster risk reduction over time.

Using and synergising both philosophical paradigms enabled us to develop a comprehensive Indigenous disaster risk reduction theory that identified a wide range of factors and processes which interacted two-way over time within and across the diverse systems levels to influence the Indigenous disaster risk reduction perception, experiences and actions/interactions in both communities. These factors included individual (e.g., worldviews, knowledges, skills, health), household (socio-economic status, health, educational, spiritual/religious views), community (community organizations, local institutions, traditional knowledges, social capital), societal (role of governments, NGOs) and place/ecological (energy disparities, area of attachment, deforestation, infrastructure issues).

Ultimately, the utility of both frameworks in our Indigenous research led to the co-production of knowledge which expands and challenges Western scientific theories enriching Western disaster risk reduction conceptualisation. Our cultural-integrative efforts also diverted the focus from Western-Indigenous or white-black-binary classification to privileging Indigenous voices and lived experiences, and exploring and uncovering diverse and interconnected Indigenous discourses regarding histories, knowledges, practices, politics, economics, and technologies that enhance our limited Western understanding of disaster risk reduction in highly valuable ways (Buergelt & Paton, Citationin press; Buergelt et al., Citation2017; Nakata, Citation2007).

To further understand the value of the systems theory and symbolic interactionism in Indigenous research, we now turn to elaborate in more detail how both philosophical paradigms assisted us individually and combined in gaining this holistic understanding.

Systems theory and symbolic interactionism in Indigenous research

In view of their perceived compatibility with Indigenous holistic worldviews, systems theory and symbolic interactions are of great value to be used in Indigenous contexts such as Indigenous disaster risk reduction. Both frameworks complement each other in ways that facilitate developing a more comprehensive and deeper understanding of the diverse aspects of how Indigenous knowledges can proactively contribute to reducing the risk of disasters in Indigenous communities. Consequently, we decided to use these two social constructionist Western frameworks in our research to gain a holistic understanding of Indigenous disaster risk reduction and to ensure a decolonising research approach.

The holistic Indigenous worldview reunites body-mind-spirit and recognises that health and wellbeing consist of and is influenced by diverse inter-related aspects including connections to ancestors (spiritual), country (ecological), physical/biological, emotions, family and kinship, community, culture, country, and spirituality (Buergelt et al., Citation2017; Smith et al., Citation2018). Systems theory and symbolic interactionism provide a useful lens for gaining a comprehensive and in-depth understanding of complex and changing interactions within and between the various levels of the system that influence health and wellbeing over time. That is, both frameworks facilitate moving beyond the reductionist approach used by positivistic Western research approaches that constructed Indigenous health as an individual problem consisting of poor health indicators to be solved through targeted, short-term Western service delivery strategies towards systematically uncovering and drawing attention to the structural and systems inequalities both inside and outside of the health sector that are at the root of Indigenous health (Hernandez et al., Citation2017).

Similarities between Indigenous worldviews and systems theory

Indigenous philosophical worldviews suggest that every creature is an interconnected part of one universal system or web, that every creature contributes to the function of the system and that each is critically important for all parts of the whole to be in balance principle (Buergelt & Paton, Citationin press; Buergelt et al., Citation2017; Poonwassie, Citation2001). Thus, the strong focus of systems theory on understanding the connections that affect, and are affected by, interactions within the web, represent an appropriate framework for examining and understanding both the relationships between Indigenous people and their ecology, and the meanings they attribute to these relationships (Heke et al., Citation2019). Importantly, understanding the nature of the relationships through the lens of systems theory can help non-Indigenous researchers to see the value of engaging in co-creating together with Indigenous peoples culturally appropriate activities and strategies that facilitate Indigenous empowerment through strength-based approaches (Heke et al., Citation2019).

A major argument for adopting systems theory derives from how holistic, relational, interactional, and process-nature Indigenous ontologies and epistemologies resemble the tenets of systems theory. Systems theory contrasts the atomistic and mechanistic approaches from philosophers like Descartes, Newton and Galileo, who advocated that knowledge can be derived by breaking the complex phenomena into their smaller components and studying them individually to understand the whole (Spruill et al., Citation2001). In contrast, systems thinking, which can be traced back to Aristotle, suggested that knowledge of a phenomenon prioritises an understanding of the whole entity over an understanding of its individual components (Aristotle holism) (Spruill et al., Citation2001).

As a scientific paradigm, systems theory was originally conceptualised by Australian biologist Bertalanffy (Citation1968). The key proposition of systems theory is that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts, and the parts of a system are open, interact with each other, and can only be understood as a complete entity (Carey & Crammond, Citation2015). A fundamental notion of the theory is its focus on the interactions and relationships of the elements within the system. The interactions and relationships change the behaviour of single, individual and autonomous elements when they interact with others (Mele et al., Citation2010). These features of systems theory are similar to the views of Indigenous ontologies and epistemologies which build on holistic, relational and temporal worldviews by linking people, earth and life on earth as interconnected parts of a complex greater web of life which functions on the principle of balance in the system (Smith et al., Citation2018).

The focus on the principles of harmony among the elements and processes of a system for maintaining their state and trajectory (Bertalanffy, Citation1968) renders systems theory an appropriate approach for Indigenous research because ensuring harmony or balance among physical, mental, emotional and spiritual dimensions is fundamental to Indigenous life and health (Poonwassie, Citation2001). From the Indigenous perspective advocating that all life functions as open systems, Indigenous worldviews, knowledges and cultural and social practices are ongoingly created and evolving through an adaptive process as a result of the interdependences with other systems in their ecology, including the systems of family, community, country, land, animals, plants and nature (Berks & Berks, Citation2009; Wallace, Citation2016). The continuous exchanges between systems contribute towards adapting actions in ways that create harmony/balance of the system.

The Indigenous principles of relationality, reciprocity and holism align with the assumptions of systems theory regarding open systems and how they interact dualistically to exchange energy with their environment. Systems theory distinguishes between open systems and closed systems and suggests that most systems are open systems. Closed systems do not interact with the outer environment and cease upon consumption of their elements (e.g., extinguishing of a candle in an airtight jar). Open systems interact two-way with their environment exchanging information, matter and energy (Barile & Polese, Citation2010). This exchange enables internal processes and transformation of elements within the system giving them the ability to adapt to the changes in their environment and thus to attain the state of balance and equilibrium (Barile & Polese, Citation2010; Mele et al., Citation2010). Mirroring the assumptions of the theory, the continuous interactions and exchanges of input and output between Indigenous systems contribute towards action, change, balance, adaptability and evolution in Indigenous worlds (Wallace, Citation2016). sums up the relational parallels of Indigenous worldviews with systems theory assumptions.

Table 1. Parallels between Indigenous worldviews and systems theory (Adopted from McKenzie & Morrissette, Citation2003)

From a research perspective, the systems-based methodology provides a means to understand human behaviour also as a function of the environment and to unpack the underlying systemic complexities within and between systems that contribute to the outcomes we experience (Carey & Crammond, Citation2015). Applied to our disaster risk reduction research, the systems Approach drew our attention to exploring holistically how factors at the Indigenous microsystems level (e.g., psychological, spiritual) and meso, exo and macro levels (e.g., natural/ecological and built environment, spiritual, social, cultural, and economic) interact over time (historically to present time) to influence the disaster risk reduction (Buergelt & Paton, Citation2014). Systematically developing an appreciation of the complexities and dynamics of influencing factors within and between the various systems can help developing individual and social system-wide transformations required for long-term and sustainable reduction of the risk of social and natural disasters (Durham et al., Citation2018).

As a systems approach aligns well with Indigenous relational and holistic worldviews, systems theory can provide an appropriate and useful framework for understanding the Indigenous perceptions and views which underpin their beliefs, functional relationships and actions. Indigenous perspectives and behaviours are the product of the interaction of diverse dimensions over time including individual, historical, natural, political, social, economic, spiritual, religious, natural and geographical at different levels, such as the individual, family, community, local or national levels (Buergelt & Paton, Citationin press; Buergelt et al., Citation2017; Smith et al., Citation2018). Therefore, a simple linear cause-effect approach cannot provide a holistic picture of Indigenous perspectives, but it can be aided by systems thinking. For example, our research identified some of the unique factors at different ecological levels of the system, such as spiritual/religious views, land connections, traditional knowledge, the role of local institutions, gender-roles, local skills and social capital which strengthen the disaster risk reduction of the Indigenous peoples. These findings indicate that Indigenous peoples have a wealth of sophisticated individual and collectivistic capacities and that exploring, supporting and strengthening these capacities holistically would greatly reduce the risk of disasters and enhance the health and well-being.

The Bronfenbrenner (Citation1979) ecological systems theory applied in our research, which builds on systems thinking, provided a valid approach for examining different ecological levels of Indigenous worlds. Ecological systems theory’s assumption that a person’s development is resulting from dialectical interactions of the person and the surrounding environment over time (chrono level) (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979) is consistent with Indigenous relational viewpoints. Bronfenbrenner termed this environment ecological system and divided it into five different levels; micro (e.g., interactions with family and peers), meso (e.g., interaction with extended family, tribe, community), exo (e.g., interactions with government services), and macro (e.g., interactions with culture, values and beliefs).

The microsystem and mesosystem led to us exploring and identifying strong extended kinship systems and reciprocity as aspects that are important for local disaster risk reduction strategies. Applying the exo-system construct enabled us to uncover Western cultural, social, religious, economic, political, educational and legal aspects increase the risk of disasters and how they increase the risk. The macrosystem construct facilitated analysing how Indigenous cultures, beliefs, norms and the values of spirituality and relationality represented important components of systems used to predict and respond to and regenerate from extreme natural events.

The chronosystem construct facilitated exploring and understanding how Indigenous worldviews, knowledges and practices made interdependent contributions to reducing and even preventing disasters and how historical and the diverse forms of historical and contemporary colonisation created a host of interacting factors within and across the diverse systems that increase the risk of disasters.

In sum, using systems theory provided us with a philosophical lens that facilitated holistically exploring and making explicit the value of Indigenous worldviews, knowledges and practices for reducing the risk of disasters and how colonisation increases the risk of disasters. This knowledge extends current disaster risk reduction knowledges in critical ways, indicating that using systems theory as a philosophical paradigm for research with Indigenous peoples can be used to respond to calls from Chilisa (Citation2012), Denzin and Linclon (Citation2008), Nakata (Citation2007), and Smith (Citation2012) for culturally appropriate Indigenous research. The use of an ecological approach is also more aligned with the holistic ‘whole community’ approach advocated by Aboriginal Community Controlled Organizations (ACCOs) for research with Indigenous communities (Smith et al., Citation2018).

However, what ecological systems theory cannot afford an understanding of is how different systems in Indigenous ecology interact dualistically and how Indigenous people interpret these interactions, which in turn influences their actions. We propose that developing the necessary complementarity in this context can be made possible using symbolic interactionism.

Similarities between Indigenous worldviews and symbolic interactionism

Relationships with, and interactions among and between peoples and country, are central to Indigenous worldviews and influence Indigenous meaning-making, knowledge-creating and actions/interactions processes (Rose & Robin, Citation2004). These meanings, knowledges and actions/interactions evolve and adapt in interaction with the changes in relationships among people and with the environment. Compared with their Western counterparts, such interactions are substantially more frequent, complex and nuanced in Indigenous communities due to their relational philosophy. The interactions with other systems in the environment are highly symbolic as people use these symbols to interpret their environment and decide their actions based on their interpretations (Charon, Citation2007). Thus, a better understanding of these interactions is one of the keys to exploring the world through the eyes of Indigenous peoples and being able to effectively collaborate. We suggest that symbolic interactionism can provide non-Indigenous researchers with a valuable philosophical lens for better understanding Indigenous peoples ways of being, knowing and doing.

George Herbert Mead (Citation1934) suggested that both self and society are integral to each other, and that, consequently, human behaviour can only be appreciated by understanding the dynamic relationships between humans and societies. Mead proposed that an individual’s sense of self emerges from the interactions with others and that the interactions among several selves create societies. Blumer’s (Citation1969) development of Mead’s thinking culminated in developing symbolic interactionism and its three core premises. First, human beings act towards things based on the meaning that the things have for them. Second, the meanings of such things arise from the social interaction that people have with others. Third, these meanings are handled and modified through an interpretative process. The theory ultimately proposes that humans and societies are in a continuous state of interaction and that through these interactions, humans learn and interpret symbols and attach meaning to those symbols based on their interpretations (Blumer, Citation1969). Humans use these symbols to interact with others; clusters of these interactions provide the foundation of society (Charon, Citation2007).

Symbolic interactionism’s focus on interactions among selves as a base of a society, and continuity of these interactions for the survival of a society, complements the Indigenous relationality principle. Indigenous societies, as collectivistic cultures, thrive on strong social interactions and relationships that derive from the ‘I/We’ thinking as opposed to ‘I/You’ in non-Indigenous, culturally individualistic, societies (Chilisa, Citation2012). The Indigenous philosophy of, commonality, unity, collectivity, plurality and social justice underpins the ‘I/We’ thinking in Indigenous world, with this ‘I/We’ philosophy promoting ‘I am we’, ‘I am because we are’ and ‘a person is because of others’ relationships (Chilisa, Citation2012, p. 21). To this social interdependence, Graham (Citation1999) proposes that Indigenous relationships build on two additional principles.

The first principle concerns relationships between land and people, with land or nature being perceived as sacred and providing a foundation for law based on ecological principles. The second principle embodies social relationships underpinned by knowing that one is not alone in the world. These relationships form the basis of Indigenous kinship systems with other people and creatures. Indigenous peoples’ identity is located in these relationships (Graham, Citation1999; Stocker et al., Citation2016). Therefore, the two principles of Indigenous relationships are central to understanding Indigenous meaning-making processes, actions/interactions and knowledge (Rose & Robin, Citation2004). These understandings and meanings alter, re-alter, evolve and adapt with the changes in relationships among people and between people with their environment, and therefore require an interpretative lens to understanding Indigenous reality construction processes, worldviews and knowledge systems.

Symbolic interactionism provides this integrative opportunity for co-constructing understanding with Indigenous people’s holistic interpretive theories because it assumes the kinds of emergent and multiple realities, indeterminacy, facts and values being inextricably linked, truth as provisional and social life as procedural (Charon, Citation2007) found in Indigenous cultures. This makes the interpretative approach offered by symbolic interactionism an appropriate one to facilitate the understanding of social behaviour of people in cultures where the characteristics introduced above are implicit, as well as how this behaviour changes – it affords ways to more clearly understand the unpredictable and unique to each social encounter (Carter & Fuller, Citation2015). Against this backdrop, symbolic interactionism thus affords more appropriate ways to examine interactions among socio-cultural, historical and local contexts that underpin how Indigenous people interpret these interactions and apply these interpretations to their interactions with their social and natural environments.

Symbolic interactionism is particularly beneficial when seeking to understand the processes behind observed behaviours and actions. That is, it affords ways to look beyond surface cultural characteristics to understand deeper socio-cultural meanings and processes and how these change over time (see above). The latter derives from understanding the constant processes people use to create and recreate their experiences through repeated interaction that are central to the theory (Carter & Fuller, Citation2015). The understanding of the philosophy of Indigenous acts through symbolic interactionism can thus play a vital role in analysing Indigenous-specific (emic) attitudes, behaviours, minds and methods in local contexts. Just as non-Indigenous research seeks to understand diversity, so too must research into Indigenous beliefs, knowledges and actions.

Although Indigenous societies around the world share common fundamental beliefs, such as an intimate relationship with nature and extended interconnected kindship systems, they also differ as a result of their interactions with their specific local environments including local land (and the benefits and challenges this environment poses to life and livelihood), knowledge, stories, histories and traditions (Stocker et al., Citation2016). These varied characteristics make Indigenous societies and their respective knowledges highly heterogeneous and local (Walter, Citation2015; Walter & Andersen, Citation2013). Recognising and upholding this reality through symbolic interactionism represents another contribution this paper makes to this emerging literature.

Indigenous heterogeneity and the role played by locality have commonly not been considered in Western epistemologies which generally promote cultural and political homogeneity (Sium & Ritskes, Citation2013). To rectify the implications the ensuing assumptions create for Indigenous research, symbolic interactionism can be utilised to respect the specific and diverse Indigenous histories and interpretations (Sium & Ritskes, Citation2013) and to focus on local narratives, experiences and histories (Willis, Citation2007). That is, symbolic interactionism serves to elucidate key facets of Indigenous socio-cultural diversity and represents a more appropriate foundation of Indigenous theory building. Using symbolic interactionism as a philosophical lens in research with Indigenous peoples suggests exploring, gaining an understanding of and articulating the complex Indigenous ways of knowledge-creating and sharing via stories, ceremonies, rituals, paintings, and dance.

Among all the symbols, Mead (Citation1934) considers words as the most powerful symbols to bestow humans the capacity to express an idea or interpretation through a spoken word that produces the same meaning in another person. Thus, language is seen as an important way through which people interact symbolically (Mead Citation1934). The role of local Indigenous languages is of substantial importance in Indigenous knowledge systems (Maypilama & Adone, Citation2013). Indigenous languages embody the past and the future and carry unique and irreplaceable values and spiritual beliefs that connect Indigenous people to their ancestors and country and enable them to take part in cultural ceremonies (Verdon & McLeod, Citation2015).

Indigenous languages are vital for maintaining and transferring philosophical worldviews and knowledge among generations through kinship, song-lines, stories, metaphors, proverbs and totems (Chilisa, Citation2012). In this sense, Indigenous languages are not only a source of communication but also well-being, self-esteem, representation and sense of identity (Verdon & McLeod, Citation2015). The forced Indigenous language oppression during colonisation has caused severe loss of Indigenous knowledges that were created over millennia (Maypilama & Adone, Citation2013). Use of symbolic interactionism in Indigenous research enables the acknowledging, legitimizing, valuing, reviving and revitalizing of Indigenous languages as a source to describe Indigenous culture (Verdon & McLeod, Citation2015).

Using symbolic interactionism in Indigenous research can also privilege the Indigenous ways of storytelling and yarning circles to share and transmit knowledge (Bessarab & Ng’andu, Citation2010; Kovach, Citation2009). Through storytelling, people narrate their day-to-day experiences, which underpin their perspectives and worldviews (Kovach, Citation2009; Sium & Ritskes, Citation2013). Yarning is an informal and relaxed conversational data collection method in which researchers and one or more participants develop a relationship and journey together through telling stories regarding the topics of research (Bessarab & Ng’andu, Citation2010). Both storytelling and yarning as data collection methods also enable tracing the long and historical processes of Indigenous erasures, dislocations, land struggles and many other atrocities that inflicted pain throughout colonisation (Sium & Ritskes, Citation2013). Symbolic interactionism lens, with its focus on life experiences and human biographies, can help to understand people’s perspectives from their experiences embedded in their stories.

Storytelling and yarning provide holistic, interconnected, collaborated, spiritual and respected aspects of indigeneity (Datta, Citation2018; Kovach, Citation2009) and help facilitate in-depth discussions that provide detailed insights into the processes and experiences of under-researched phenomena in Indigenous research (Bessarab & Ng’andu, Citation2010: Datta, Citation2018). These narratives can also take the form of small-scale ethnographies, in-depth interviews, historical analysis and textual readings of culture in Indigenous research through qualitative, interpretive and symbolic interactionism lens (Willis, Citation2007). summarizes the similarities between the Indigenous knowledge systems and symbolic interactionism.

Table 2. Parallels between Indigenous worldviews and symbolic interactionism

Synergy of systems theory and symbolic interactionism: a passageway for non-Indigenous researchers understanding Indigenous worldviews

The synergy of systems theory and symbolic interactionism can serve as a passageway for non-Indigenous researchers to start developing an understanding of Indigenous worldviews, knowledges and practices as they share key features with Indigenous paradigms. Although both theories emerged roughly 30 years apart, the basic ontological and epistemological assumptions of both are similar. Both theories propose that humans and environments interact two-way in complex ways over time within and across diverse and nested open systems ranging from the individual and local to the social and global. They position that, on the one hand, peoples’ experiences and behaviours are affected by diverse factors in the environment they live in. The meanings people assign to their experiences are a result of previous interactions and experiences and influences how they respond to their experiences. However, people are, at the same time, agents who can construct new meanings. The way people respond determines future experiences. The individual and collective actions and interactions ongoingly create the environment. The interactions are symbolic and predominately linguistic.

The combination of both theories creates a paradigm that can provide a useful philosophical lens when researching with Indigenous peoples as they guide researchers to consider Indigenous affairs as a whole complex and dynamic system including socio-historical and political contexts from the perspectives of Indigenous peoples. This paradigm can enable non-Indigenous researchers to engage with Indigenous community members in ways that afford opportunities for their developing understanding of unique Indigenous ancient worldviews, knowledges and practices, how they influence the way Indigenous peoples act and interact and develop research in ways that are culturally valid and informative.

The paradigm also can assist researchers critically exploring and uncovering how the interaction of complex factors during historical and contemporary colonisation has and remains a source of the multitude of inequalities Indigenous peoples suffer and the existential crisis humanity is experiencing. Furthermore, a combination of both provides an interpretive lens that shows non-Indigenous researchers how focusing on exploring the dialectical interactions between all dimensions and levels of the system, especially the socio-cultural-ecological levels, can lead to understanding reality in the lived and empirical world in a local context (Shahid et al., Citation2009).

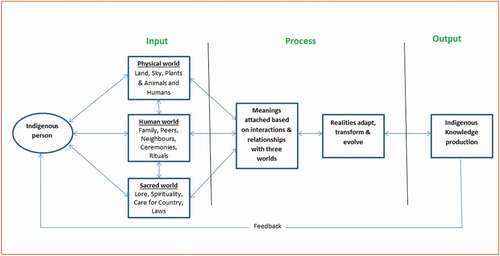

The synergy of both theories, as shown in , can infer that a human is a system and that social interactions, the key to the symbolic interactionism, occur between and within different systems. From a systems theory perspective, Indigenous peoples, communities, agencies, governments, lands, plants and animals are the interacting sub-systems of the greater cosmos. From a symbolic interactionism perspective, the social interactions which occur between and within these subsystems, and thus create symbols and meanings, can be considered interactions within these systems. The continuous interactions or exchanges of inputs or outputs within and between the subsystems are critical feedback that creates emerging, changing and evolving meaning-making processes of symbols and situations (Wallace, Citation2016).

Conclusion

Holistic, relational, contextual, emergent and adaptive Indigenous worldviews require an interpretive lens in Indigenous research. Such theoretical lens can inquire the spiral-like dualistic interactions between lived experiences, how Indigenous peoples interpret these experiences, the factors that influence these interpretations, and how these interpretations influence their actions. We propose that synergy of systems theory and symbolic interactionism may offer such an interpretive approach to non-Indigenous researchers involved in Indigenous research. The assumptions of both theories – that humans are the products of their environment – are parallel to Indigenous relational and holistic philosophy. Understanding the synergy of both in Indigenous research can draw attention to the importance of nature-human relationships and contextual influences and allow for the identification of the interaction of individual and contextual variables that influence Indigenous perceptions and actions from micro to macro levels from their perspective.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. The term Indigenous in this paper refers to the non-dominant but autonomous peoples and groups of society who have unique spirituality, bounded relationships to lands, local languages, cultures and beliefs, and contextual social, economic and political systems (Foley, Citation2003; Moreton-Robinson, Citation2014).

References

- The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. (2012). Guidelines for ethical research in Australian Indigenous studies. Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. https://aiatsis.gov.au/sites/default/files/docs/research-and-guides/ethics/gerais.pdf

- Barile, S., & Polese, F. (2010). Smart service systems and viable service system: Applying systems theory to service science. Service Science, 2(1–2), 21–40. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1287/serv.2.1_2.21

- Berks, F., & Berks, M. K. (2009). Ecological complexity, fuzzy logic, and holism in Indigenous knowledge. Futures, 41(1), 6–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2008.07.003

- Bertalanffy, L. V. (1968). General system theory. Braziller.

- Bessarab, D., & Ng’andu, B. (2010). Yarning about Yarning as a legitimate method in Indigenous research. International Journal of Critical Indigenous Studies, 3(1), 37–50. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcis.v3i1.57

- Blumer, H. (1969). Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and methods. Prentice Hall.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). the ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press.

- Buergelt, P. T., & Paton, D. (2014). An ecological risk management and capacity building model. Human Ecology, 42(2014), 591–603. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-014-9676-2

- Buergelt, P. T., & Paton, D. (in press). Facilitating effective DRR education and human survival: Intentionally engaging the transformation education-paradigm shift spiral. In H. James (Ed.), Risk, resilience and reconstruction: Science and governance for effective disaster risk reduction and recovery in Australia and the Asia Pacific. Palgrave MacMillan/Springer.

- Buergelt, P. T., Paton, D., Sithole, B., Sangha, K. K., Prasadarao, P. S. D. V., Campion, O. B., & Campion, J. (2017). Living in harmony with our environment: A paradigm shift. In D. Paton & D. Johnston (Eds.), Disaster resilience: An integrated approach (pp. 289–304). Charles C Thomas.

- Carey, G., & Crammond, B. (2015). Systems change for the social determinants of health. BMC Public Health, 16, 662. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1979-8

- Carter, M. J., & Fuller, C. (2015). Symbolic interactionism. Sociopedia.isa 1(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/205684601561

- Charon, J. M. (2007). Symbolic interactionism. Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Chilisa, B. (2012). Indigenous research methodologies. Sage Publication.

- Chilisa, B., & Tsheko, G. N. (2014). Mixed methods in Indigenous research: Building relationships for sustainable intervention outcomes. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 8(3), 222–233. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689814527878

- Datta, R. (2018). Traditional storytelling: An effective Indigenous research methodology and its implications for environmental research. AlterNative, 14(1), 35–44. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1177180117741351

- Denzin, N. K., & Linclon, Y. S. (2008). Introduction: Critical methodologies and Indigenous inquiry. In N. K. Denzin, Y. S. Lincoln, & L. T. Smith (Eds.), Handbook of critical and Indigenous methodologies (pp. 1–20). Sage.

- Durham, J., Schubert, L., Vaughan, L., & Willis, C. D. (2018). Using systems thinking and the Intervention Level Framework to analyse public health planning for complex problems: Otitis media in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. PLOS One, 13(3), 1–20. http://clok.uclan.ac.uk/14387/1/14387_Maypilama_40571.pdf

- Foley, D. (2003). Indigenous epistemology and Indigenous standpoint theory. Social Alternatives, 22(1), 44–52. https://search.informit.org/doi/https://doi.org/10.3316/ielapa.200305132

- Graham, M. (1999). Some thoughts about the philosophical underpinnings of Aboriginal worldviews. Global Religions, Culture, and Ecology, 3(2), 105–118. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1163/156853599X00090

- Gray, M. A., & Oprescu, F. I. (2016). Role of non-Indigenous researchers in Indigenous health research in Australia: A review of the literature. Australian Health Review, 40(4), 459–465. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1071/AH15103

- Heke, I., Rees, D., Waititi, R. T., & Stewart, A. (2019). Systems thinking and Indigenous systems: Native contributions to obesity prevention. Alter Native. An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 15(1), 22–29. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1177180118806383

- Hernandez, A., Runao, A. L., Marchal, B., San, S., & Miguel, F. W. (2017). Engaging with complexity to improve the health of indigenous people: A call for the use of systems thinking to tackle health inequity. International Journal for Equity in Health, 16(26), 1–5. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-017-0521–2

- Kovach, M. (2009). Indigenous methodologies: Characteristics, conversations, and contexts. University of Toronto Press.

- Kovach, M. (2010). Conversation method in Indigenous research. First Peoples Child & Family Review, 5(1), 40–48. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7202/1069060ar

- Kukutai, T., & Walter, M. (2015). Recognition and indigenizing official statistics: Reflections from Aotearoa New Zealand and Australia. Statistics Journal of the IAOS, 31(2), 317–326. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3233/sji-150896

- Kurtz, D. L. M. (2013). Indigenous methodologies; Traversing Indigenous and Western worldviews in research. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 9(3), 217–229. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/117718011300900303

- Matsumoto, D., & Juang, L. (2008). Culture and psychology. Thompson/Wadsworth.

- Maypilama, E., & Adone, D. (2013). Yolŋu sing language: An undocumsnted language of Arnhem Land. International Journal of Learning in Social Context, 13, 37–44.http://australianhumanitiesreview.org/2004/04/01/the-ecological-humanities-in-action-an-invitation/

- McKenzie, B., & Morrissette, V. (2003). Social work practice with Canadians of Aboriginal background: Guidelines for respectful social work. In A. Al-Krenawi & J. R. Graham (Eds.), Multicultural social work in Canada: Working with diverse ethno-racial communities (pp. 251–282). Oxford University Press.

- Mead, G. H. (1934). Mind, self and society. University of Chicago Press.

- Mele, C., Ples, J., & Polee, F. (2010). A brief review of systems theory and their managerial applications. Service Science, 2(1–2), 126–135. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1287/serv.2.1_2.126

- Moreton-Robinson, A. (2014). Towards an Australian Indigenous women’s standpoint theory. Australian Feminist Studies, 28(78), 331–247. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08164649.2013.876664

- Nakata, M. (2007). The Cultural Interface. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 36(S1), 7–14. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ622699.pdf

- National Health and Medical Research Council Australia, (2018). Ethical conduct in research with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples and communities. National Health and Medical Research Council. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/resources/ethical-conduct-research-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-peoples-and-communities

- Norenzayan, A., & Heine, S. J. (2005). Psychological universals: What are they and how can we know? Psychological Bulletin, 131(5), 763–784.https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/des/article/view/19626/16256

- Poonwassie, A. (2001). An Aboriginal worldview of helping: Empowering Approaches. Canadian Journal of Counselling, 35(1), 63–73. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ622699.pdf

- Rose, D. B., & Robin, L. (2004). The ecological humanities in action: An invitation. Australian Humanities Review, 31–32.http://australianhumanitiesreview.org/2004/04/01/the-ecological-humanities-in-action-an-invitation/

- Shahid, S., Bessarab, D., Howat, P., & Thompson, S. C. (2009). Exploration of the beliefs and experiences of Aboriginal people with cancer in Western Australia: A methodology to acknowledge cultural difference and build understanding. BioMed Central, 9(60), 1–8. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1471–2482-9-1

- Sium, A., & Ritskes, E. (2013). Speaking truth to power: Indigenous storytelling as an act of living resistance. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 2(1), 1–10.https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/des/article/view/19626/16256

- Smith, J. A., Bullot, M., Kerr, V., Yibarbuk, D., Olcay, M., & Shalley, F. (2018). Maintaining connection to family, culture and community: Implications for remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander pathways into higher education. Rural Society, 27(2), 108–124. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10371656.2018.1477533

- Smith, L. T. (2012). Decolonising methodologies: Research and Indigenous people (2nd ed.). Zed Books.

- Spruill, N., Kenny, C., & Kaplan, L. (2001). Community development and system thinking: Theory and perspective. National Civic Review, 90(1), 105–116. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/ncr.90110

- Stewart, S. (2009). Family counselling as decolonization; Exploring an Indigenous social-constructivist approach in clinical practice. First People Child & Family Review, 4(1), 62–70. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7202/1069330ar

- Stocker, L., Collard, L., & Rooney, A. (2016). Aboriginal worldviews and colonisation: Implications for coastal sustainability. Local Environment, the International Journal of Justice and Sustainability, 21(7), 844–865. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2015.1036414

- Verdon, S., & McLeod, S. (2015). Indigenous language learning and maintenance among young Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. International Journal of Early Childhood, 47(1), 153–170. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-015-0131-3

- Wallace, C. L. (2016). Overcoming barriers in care for the dying: Theoretical analysis of an innovative program model. Social Work in Health Care, 55(7), 503–517. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00981389.2016.1183552

- Walter, M. (2015). Data politics and Indigenous representation in Australian statistics. In T. Kukutai & J. Taylor (Eds.), Indigenous data sovereignty: Toward an agenda (pp. 79–98). ANY Press.

- Walter, M., & Andersen, C. (2013). Indigenous statistics: A quantitative methodology. Left Coast Press.

- Willis, J. (2007). Foundations of qualitative research. Sage.

- Wilson, S. (2008). Research in ceremony: Indigenous research methods. Fernwood.