ABSTRACT

COVID-19 immediately and radically necessitated changes in the way we worked as social researchers; not only in terms of fieldwork, but also in terms of collaboration. In this paper, we outline the rationale, processes, and potential of a collective of 14 research teams both inside and outside of academia working together across the UK to synthesise findings on the experiences of over 4,000 families parents and carers living on a low-income during the pandemic. Drawing on an approach based on meta-ethnography, our collective body of work comprises novel evidence and insights generated with a major cohort of families living on a low-income, through which we examine the impacts of the pandemic, and implications for social policy. This paper focuses on the practical, ethical, and methodological learnings and reflections on the processes of research synthesis in the pandemic context, and beyond. We set out the underpinning principles that guided our collaborative efforts before we explore the possibilities and challenges of working together to produce coherent, timely, and relevant findings that were shared with policy makers and those in power. Finally, we emphasise the significant potential of working collaboratively, and stress the importance of continuing to do so in a post-pandemic context.

Introduction

Covid-19 immediately and radically necessitated changes in the way we worked as social researchers, not only in terms of fieldwork but also in terms of collaboration. In a global public health emergency, there is a clear moral imperative to meaningfully collaborate to produce the best possible evidence – in social science as well as in medicine. While Covid-19 created a vital requirement for research to understand the epidemiology and lived experiences of the pandemic, it was crucial to recognise that researchers themselves were also operating in a new, difficult context. Not only were researchers having to contend with lockdowns, school closures, and the widespread fear and anxiety that the pandemic brought, they were also facing a fast moving and changing policy context (both in the UK and globally), as well as immediate changes in the ways in which it was possible and ethical to conduct research. This made traditional ways of researching, and of engaging with policymakers and stakeholders, suddenly unsustainable. There was a parallel need to ensure that while there was a requirement to act quickly to embark on new research where needed (and appropriate), we also needed opportunities for the research community – both within and outside of academia – to share the burden by collectively thinking through this new context, ensuring that research responses were appropriate, ethical, and effective in providing policy relevant findings in a timely manner.

As social researchers, we were required to rapidly adapt our previous practices of carrying out research, particularly fieldwork, as a result of the social distancing measures and restrictions put in place due to the pandemic. As Nind et al. (Citation2021, p. 1) have observed, researchers had to ensure ‘that their research continues, and that it remains valid, relevant and ethical in the face of extreme challenges and huge social change’. Face-to-face interviews were no longer available as a method; instead, remote interviews via Skype, Zoom, or telephone had to be undertaken. Issues around digital exclusion and accessibility needed to be carefully considered (Coverdale et al., Citation2021). These important decisions and considerations were having to take place while we worked from home, often in highly pressurised, emotionally stressful, and socially isolated conditions. Covid-19 challenged us all, professionally and personally, as we had to adapt and respond to lockdowns, school closures, and the risk of ourselves and our loved ones falling ill. Against this extraordinary and novel context, working together alongside other social researchers seemed essential not only due to the immediate need to transform our research practices to ensure they were fit for purpose for the ‘new normal’, but also to provide a forum for peer support and solidarity. Working together facilitated the creation and holding of spaces to reflect upon decision-making against this new context, and to provide supportive feedback on approaches to managing the unprecedented change we were all experiencing. As Rahman et al. (Citation2021, p. 2) have described:

‘Importantly, we acknowledge that the Covid-19 pandemic and subsequent social distancing measures have placed significant stress on individuals’ lives, including those of researchers and participants. Our paper does not advocate continuing research during the pandemic or other crises merely for its own sake. Every researcher has to weigh the pros and cons of continuing research in crises, taking note of their physical and mental health as well as that of participants.’

A collaborative approach was also beneficial because it helped to avoid the duplication of efforts and unnecessary burdens on those taking part in research projects in the first place. Significantly, while it was Covid-19 that prompted this collaboration, the benefits that arise from it are not exclusive to pandemic or crisis contexts, as we will explore further below.

This paper outlines the rationale, processes, and potential of a collective of 14 research teams working together across the UK to adapt and respond to the Covid-19 research climate, synthesising findings on the experiences of poverty for families living on a low-income during the pandemic. We begin by detailing our methodological approach, and explain why an approach based on Noblit & Hare’s, Citation1988) seven-stage process of meta-ethnography was adapted. The underpinning principles that guided our collaborative efforts are then detailed, before we explore the radical potential of working together in order to produce and interpret coherent, timely and relevant findings to be shared with key policy makers and those in power. We then draw out wider lessons from the research synthesis process, especially around the significant potential (and challenges) of working collaboratively, and emphasise the importance of continuing to do so in a post-pandemic context.

Our methodological approach: research synthesis in times of crisis

As Howlett (Citation2022, p. 1) observes, ‘the Covid-19 pandemic has forced us to re-think our approaches to research’. Due to social distancing measures, and the ongoing uncertainty and risks presented by the pandemic, conducting in-person research was no longer possible. Instead, as researchers we needed to find new ways of documenting and understanding experiences during the pandemic. Researchers adapted their fieldwork quickly to adhere to social distancing measures, including sometimes in ways that fell outside of existing training and expertise (Howlett, Citation2022). The pandemic presented us with a requirement, but also an opportunity, to reconsider how evidence-making could be done differently, including the potential of methodological pluralism across disciplines (Lancaster et al., Citation2020).

We created a unique collaborative research synthesis approach that drew heavily on meta-ethnography, which involved spanning disciplinary boundaries and working across multiple methodologies both within and outside of academia. Feast et al. (Citation2018, p. 2) note how meta-ethnography has emerged as a useful method to synthesise and integrate both qualitative and quantitative data from different perspectives using a qualitative methodology. This process enables the drawing together of varied data sources guided by a framework based on key research questions, which also allows for emergent issues to be included and unpacked. Doyle (Citation2003, p. 322) has observed how ‘meta-ethnography not only offers possibilities as a method of inquiry, but also is a process for extending democratic principles’. The process ‘is an example of synthesis that moves toward reconceptualization’ (Doyle, Citation2003, p. 325). Findings are then drawn together and synthesised, creating new insights that might inform theoretical developments in the field (Noblit & Hare, Citation1988).

Noblit and Hare’s (Citation1988) seven-step process for conducting a meta-ethnography working with qualitative studies was adapted and employed within our study. Their seven-step process (getting started; deciding what is relevant to the initial interest; reading the studies; determining how the studies are related; translating the studies into one another; synthesising translations; and expressing the synthesis) was useful in beginning, conducting, and reflecting on the overall synthesis process across our collective. Our overall aim was to bring the 14 studies ‘into one another’ (Noblit & Hare, Citation1988, p. 25), developing new interpretations and conceptual insights through this process.

As we were working with a plurality of methodologies, we found that some stages of Noblit & Hare’s, Citation1988) process were more relevant than others. For example, getting started and deciding what was relevant involved the project leads initiating contact with, and organising the collective (described in further detail below). As we were not embarking upon an analysis of existing research projects’ findings, but rather emergent and ongoing findings, this stage was not applied in its strictest sense. Determining how the studies were related, and subsequently translating the studies into one another, and synthesising them, was a process that took time, meaningful collaboration, and consideration, and was explored via regular meetings, thematic mapping exercises, and virtual workshops. Finally, expressing the key overall messages from the synthesis was a continual and reflective process, as a later section details.

Much research describes processes of applying meta-ethnography to the synthesis of qualitative research (for instance, see Atkins et al., Citation2008; Britten et al., Citation2002; Lee et al., Citation2015). As our approach involved working with multiple methodologies across disciplinary and organisational boundaries, we also found Sandelowski et al.’s (Citation2006) mixed research synthesis, which incorporates the integration of results from both qualitative and quantitative studies in a shared domain of empirical research, to be relevant to our collective efforts. In mixed research synthesis – as in our approach – the data are the findings of primary qualitative and quantitative studies in a designated body of empirical research, rather than raw data itself. Our approach relied on what Sandelowski et al. (Citation2006, p. 8) term an ‘integrated design’, in which ‘the methodological differences between qualitative and quantitative studies are minimized as both kinds of studies are viewed as producing findings that can readily be transformed into each other’ (ibid.). Heyvaert et al. (Citation2013, p. 662) have commented that the integration of qualitative and quantitative studies at the synthesis level has ‘promising utility for research and practice, since the rationale for conducting mixed methods synthesis research lies in combining the strengths of qualitative and quantitative techniques and studies’. As Voils et al. (Citation2008, p. 23) have suggested, ‘the value of any synthesis method can be determined only by looking past idealized notions of what findings qualitative and quantitative methods ought to produce and directly at the findings themselves’.

Often, the practicalities and processes of synthesis are often not well-described. Feast et al. (Citation2018, p. 3) note that: ‘Methods for combining and synthesizing quantitative and qualitative data remain the least developed and poorly specified.’ Here, we outline practical, methodological, and ethical considerations for working together to synthesise findings on poverty and low-income family life during the pandemic. Below, we begin by outlining the processes of synthesis and collaboration that were co-created across 14 research teams working both within and outside of academia.

The ‘COVID-19 and families on a low income: researching together’ collective

The Covid Realities project is a major research programme funded by The Nuffield Foundation. It documented the everyday experiences of families with children on a low-income during the pandemic, through a collaboration including parents and carers with dependent children, researchers across two universities, and the Child Poverty Action Group (CPAG). There is a focus within the project on families’ experiences of social security, but also on wider everyday life, including how families navigated living through the pandemic. In this article, we focus on documenting a discrete element of the Covid Realities research programme, the ‘COVID-19 and families on a low income: Researching together’ collective, a collaboration between 14 different research teams, including academics and researchers from the voluntary sector, working with over 4,000 parents and carers across the UK.

Developing the collective

When devising the project in March 2020, we recognised that within the Covid-19 context it was vital we continued to document and understand the lived experiences of families living through poverty during the pandemic, while also increasing the policy reach and potential impact of the resultant data through processes of synthesis. A central element of our research programme was to work closely with research teams already undertaking fieldwork across with families in poverty in the UK, to support the generation of data specifically on the experiences of families on a low-income during Covid-19, and then to aggregate and disseminate the resultant data. We also wanted to create a space of support and solidarity for research teams to collectively think through how to adapt their methodologies for a rapidly changing context. Encouragingly, our idea to aggregate evidence bases was immediately popular within the research community, reflecting researchers’ desire to work together.

An underpinning belief of our collective was that we could make the clearest impact on behalf of families by working together. As such, from the outset we were committed to working ethically, robustly, and effectively to ensure that evidence was available about the particular needs of families in poverty, and that this evidence would be communicated to policymakers and other beneficiaries in a timely and accessible way. This novel and unique way of working that underpinned the collective runs counter to traditional academic approaches, which focus on ‘individualised incentives and performance targets, heralding new and more stringent conceptions of accountability and monitoring across the higher education sector’ (Olssen, Citation2016, p. 130). This new way of researching, which focused on collaboration over competition, felt especially suitable and welcome in the pandemic context, yet the processes, rationale, and outcomes of working in this way are not frequently discussed. For instance, Dewaele et al. (Citation2021, p. 1) have noted that:

‘there is little knowledge about how collaboration processes are experienced, how we can theoretically conceptualize them, and how in this way we can develop efficient collaboration methods that contribute to solving urgent societal problems.’

How did we work together?

Project leads (Ruth Patrick, Kayleigh Garthwaite, and Maddy Power) were initially cautious of approaching social researchers about taking part in the project, given the ethical considerations and sensitive nature of the incredibly challenging and rapidly changing situation, and the difficulties this placed on everyone involved. We did not want the proposed project to add to any of these pressures. Like Markham et al. (Citation2021, p. 1), we were guided by a ‘feminist perspective and an ethic of care to engage in open-ended collaboration during times of globally-felt trauma’. This was important in terms of participant wellbeing, but also with regard to our fellow researchers. Given the additional demands that working collaboratively could bring, we were wary of our collaboration resulting in greater burnout and stress for researchers.

In order to build the collective of research teams, first we (Ruth, Kayleigh, and Maddy) contacted people within our networks who we knew were conducting research in the areas of poverty and social security with families on a low-income to investigate the possibilities of working collaboratively. We then used a snowballing approach, asking our networks to recommend other potentially suitable projects and contacts. We also shared our invitation to collaborate via JISCMAIL lists, as well as contacting various organisations and scholars directly, in order to try and ensure we had representation across all four devolved nations in the UK. This was also an important step in ensuring we were working in the most open and collaborative way possible, and an attempt to go beyond our own previously known associations.

Unlike much academic research, our approach was open, rather than exclusive, aiming to include all relevant projects that were interested in being involved, while maintaining some boundaries to ensure that the project was achievable. We aimed to involve 10–15 research projects and teams in the synthesis process; too many projects could become unmanageable, and too few risked our efforts being unsuccessful. When approached, there was an enthusiastic response to our suggested way of working, which helped convince us that there was an identified and unmet need for this collaborative way of working. Despite the challenges and uncertainties brought about by the pandemic, it was evident that many research teams were keen to continue with their planned fieldwork, but there was uncertainty around how best to do this, given the crisis context. Providing a network and associated platform for support thus enabled researchers to collectively navigate the tensions of conducting fieldwork during the pandemic in terms of intellectual and emotional support, while also sharing best practice and lessons learnt. Between March 2020 and June 2020 we identified thirteen projects, both inside and outside of academia, who agreed to participate alongside Covid Realities.

As mentioned, our project partners are from within and outside academia, as we were keen to build connections and facilitate opportunities to collaborate with people beyond the ivory tower of Higher Education. The resultant ‘COVID-19 and families on a low income: Researching together’collective worked together as a Special Interest Group (SIG) of fourteen projects to support the generation of data specifically on the experiences of families on a low-income during Covid-19, and to synthesise and disseminate relevant findings to policymakers and other key audiences. Membership of the SIG was comprised of Principal Investigators and researchers across career stages, institutions, and organisations.

Despite restrictions on face-to-face fieldwork, our projects employed a diverse range of methodological approaches, including quantitative, qualitative, longitudinal, participatory, and arts-based approaches. Conducted online and via digitally mediated forms of communication, methods include online interviews (using Zoom/Skype); telephone interviews; diaries; national surveys, both postal and online; asset mapping; Zoom discussion groups with parents and carers living in poverty; and zine making workshops. Many of the projects also worked closely with community stakeholders and practitioners from national support organisations to understand the impacts of lockdown on the national support infrastructures. We documented the implications of the Covid-19 crisis for families experiencing poverty in the UK, explored the capacity of the social security system to provide sufficient support, and detailed gaps and problems with provision in the immediate crisis, its aftermath, and into the medium-term. As such, we collated a strong co-produced evidence base to draw on in order to offer insights into key issues facing parents and carers on a low-income during the pandemic.

Guiding principles for collaboration

Since our collective began working together in April 2020, we found a huge value in collaborating, and emphasising key findings across our diverse set of projects. However, this approach was not without its tensions and challenges. Shared concerns have inevitably risen over data ownership, outputs, and messaging. Academics, at whatever stage in their career, face very real pressures to have ‘world leading’, ‘impactful’ outputs, and these expectations are linked to job performance and progression in ways that inevitably influence possibilities, and perhaps place limits on, collaboration. It was therefore essential to think through and agree principles of joint working in advance; principles that were added to iteratively as our joint working continued.

Neale and Bishop (Citation2012) outline the stakeholder approach, which is based on an ethos of collaborative working and finding common solutions in the face of competing needs and interests. Important here is clarity and high-quality relationships that are built and maintained across the projects, from the outset and over time (Hughes & Tarrant, Citation2020; Tarrant, Citation2017). We recognised that we would be working within and outside of academia, across different methodologies and research contexts, with differing institutional and organisational pressures. Therefore, as a group we developed a core set of mutual values to underpin our collaborative work, which are described in the following section.

Communication, negotiation, and flexibility

The importance of successful communication, negotiation, and flexibility amongst the Special Interest Group (SIG) was vital from the outset. It is easier to presume shared meanings than to probe; as a result, we would repeatedly ask the collective – do we all mean the same thing? After all, our projects are drawn from outside academia in anti-poverty and charitable organisations, and within academia across the multiple disciplines of social policy, sociology, epidemiology, and human geography. We sought to strike an important balance between being available for regular and open communication, and investing time to enable this – but also being realistic and recognising that everyone is busy and had limited time, especially with the additional pressures of working at home, and juggling caring responsibilities as a result of the pandemic.

In practice, this meant ensuring that SIG members were given the opportunity to shape and construct any outputs, such as presentations, blog posts, journal articles, and so on. With this paper, for instance, it was co-authored by the project team who designed and facilitated the process of research synthesis. SIG members were invited to co-author the article, but chose to provide helpful feedback and insights instead, given the paper was documenting an approach designed by the Covid Realities project team.

Some projects had greater time, space, ability, and indeed desire to be more involved in the core group than others. Meetings were arranged via Doodle poll to ensure the greatest number of people could attend and input into SIG activities. Kayleigh also had one-to-one check-ins with individual projects throughout to provide support and offer guidance. However, this could mean that each month different members were present at SIG meetings, and sometimes points we had agreed on in one meeting would need to be revisited or rethought entirely.

A particular challenge was deciding on the ‘right’ time to synthesise findings and agree on joint policy recommendations. Following several discussions at our SIG meetings, this process emerged organically as we responded to parliamentary calls for evidence, and gave joint presentations. Being responsive to policy interests in this way enabled the identification of key themes and policy relevant recommendations, in real time.

Ethics

Our collaboration was deeply rooted in a commitment to thinking sensitively about how we adapted our research to the pandemic context. This included seeking to reduce additional burdens on people taking part in research; ensuring research efforts were not needlessly duplicated; and seeking to maximise the policy impact of our collective evidence base. Here, we were led by a feminist ethics of care that recognised the interdependencies and diverse needs of our fellow collaborators (Groot et al., Citation2019). This included emphasising the need for communication and self-care; particularly relevant as the pandemic was universally experienced, with impacts both on the professional and personal lives of researchers and participants. Here, the SIG functioned as a source of solidarity and support.

A key aim of the synthesis process was to ensure that the research complied with the highest ethical standards, was sensitive to the challenging context in which it was being conducted, and was respectful of the difficulties the ever-changing context would place on everyone involved in the project. Researching the experiences of families in poverty in ‘normal’ times raises significant ethical issues and considerations. It is an essential prerequisite that ethical research into the lived experiences of poverty commits to do more than simply ‘collect data’ from participants (Sime, Citation2008). However, in the context of a pandemic, ethical considerations become only more critical and difficult to work through. All researchers of poverty and social security needed to consider how to conduct fieldwork in the shifting ethical terrain, ensuring research that is carried out is sensitive in its duty of care, not only to families living in poverty themselves, but in its wider relationships with stakeholders.

Like Thomson and Berriman (Citation2021, p. 9), we were keen to generate a dataset that could be ‘shared with others in a way that would not compromise the privacy of participants’. For several key reasons, the decision was made to synthesise findings rather than raw data across our collective. Firstly, this was because initial consent from participants had not included a discussion of raw data being shared with researchers from other institutions and organisations. Researchers from each project would therefore need to go back to participants and seek consent for their data to be used in this way, which was neither a feasible nor desirable option. The ethical and General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) principles involved in synthesising raw data could be considered when preparing future research projects, as this way of collecting and analysing data could be fully explained and explored in ethics applications and consent forms, therefore setting up the building blocks for allowing data to be used in this way. Secondly, prioritising participant wellbeing (Coverdale et al., Citation2021) was a central concern for all participating projects. We were extremely cautious of overburdening participants, who were not only facing the difficulties of living on a low-income, and we were aware of how this were being exacerbated by the pandemic. This was something each individual project had to navigate themselves, but as a SIG we were mindful of not creating additional work for participants, instead choosing to work with synthesising the data we already had. As a result, we concluded that the synthesis of raw data would have been a messy and ambiguous process, and instead chose to synthesise our findings across the collective.

Not only did we have a duty of care to all participants, ensuring basic ethical principles of ensuring all shared findings would be anonymised, but we also had a duty of care to each other as researchers working in new and often difficult contexts. Brannelly (Citation2018) has recognised that an ethics of care approach values longer-term ongoing relationships over time, something that has developed through our work as a collective. A key part of this was using our collective as a space of solidarity, offering mutual support, understanding, and empathy (Pratt et al., Citation2020). The group also became a space for troubleshooting and sharing best practice. For instance, an ideas sharing workshop around digital technologies and remote interviewing was held in July 2020 where we shared ideas on what worked well (and what had not). We also arranged virtual writing retreat workshops to support one another during the writing of a SIG edited collection, which offered a supportive and welcoming space.

Conducting ethical research into poverty also creates a requirement to facilitate effective and impactful chains of policy making engagement and dissemination. We all recognised the importance of seeking to ensure that the evidence generated would help inform current and future policymaking. We sought to secure ongoing engagement with policy makers in real time in order to communicate how social security policy and the lives of families on a low-income were changing as a result of the pandemic. In this way, we aimed to lay the foundations for future interventions that more effectively recognise the challenges faced by families living in poverty, both during the crisis and in the future.

Developing processes of synthesis: ‘getting started’

A key consideration for our research synthesis was highlighting the core issues that were emerging across our diverse range of studies; to emphasise commonalities of experience; and to offer timely policy recommendations. Design and fieldwork was already well underway with the majority of projects across the collective when we began working together, and it is important to note that we were not working with a uniformity of data, as outlined previously. At the outset, we developed protocols with SIG members for publication, policy engagement, and sharing of data. These processes also confirmed any distinct parallels – or potential divergences – in the interpretive frames of the research teams; sufficient thematic linkage between studies; and that the studies were synchronic i.e. conducted in contemporaneous times (overlapping the global pandemic of Covid-19).

The analytical process included collating a repository of relevant research studies, including details on: i) populations and sample sizes, socio-demographic features, study designs, methods, timing, and frequency of data collection etc; and ii) domains and data being collected – copies of surveys, interview schedule etc.; and iii) aims, objectives and research questions. It also involved co-designing, with study leads, overarching research questions and analytic plans for synthesising findings. This process involved ensuring that the analysis would build upon and extend interpretations produced by the original research teams. For instance, some projects incorporated research question(s) that were used in other projects, and ways of working were shared in order to influence and shape best practice. It is important to note that our aim was not to homogenise the research field, but to explore commonalities of experience between studies, in order to emphasise what policy change was needed, and why. Working with a diversity of research teams from inside and outside the academy, across different methodologies, and geographical locations, proved to be a real strength of our collective, as we were able to demonstrate the extent and reach of the (in)adequacy of the social security system response; the realities of getting by in hard times; and the importance (and often lack of) support networks for families on a low-income (see, Garthwaite et al., Citation2022 for further details on our findings).

Drawing on the Timescapes Initiative, Bishop and Neale (Citation2012, p. 1) have commented that ‘descriptive case profiles and longitudinal case histories that condense complex data into manageable forms for primary and secondary analysis’ are helpful in thinking through how best to manage data. They note that the creation of descriptive, factual data about the sample is an important part of this process of documentation that can then provide a bridge to the analytical process. A series of recommendations for how to do this effectively have been made by the Timescapes secondary analysis team (Irwin & Winterton, Citation2011). To aid the synthesis process, we completed two rounds of conceptual mapping exercises that sought:

A description of the project, including title, research aims and questions, research design and methods, funders, details of research team, and start and finish dates;

A description of the dataset, including the number of participants, cases, waves, gathered over what time scales.

Following Irwin and Winterton’s (Citation2011) guidance, a thematic mapping document was created, which acted as a ‘live’ collaborative document where each project added information on demographics, original research questions, key themes, and emerging findings. Virtual thematic analysis workshops were held in November 2020, May 2021, and June 2021 to explore emerging cross-cutting themes and produce a synthesis of key temporal data and findings (Neale & Bishop, Citation2012). These workshops were used to explore key themes in more detail and depth, and offered the opportunity for contextual and thematic sharing (Hughes & Tarrant, Citation2020). Around the time of each workshop, each project recorded a brief summary in response to the following three questions: i) Who are the parents and carers your project is working with? E.g. number of children; gender; ethnicity; employment; social security; ii) What are the key issues facing parents and carers on a low-income during Covid-19? and iii) What one policy change would make a difference to the lives of parents and carers living on a low-income? Following these workshops, researchers could then return to datasets to mine for further related data as needed. Findings were drawn together and synthesised, rendering the ‘whole as greater than the sum of the parts’ (Noblit & Hare, Citation1988, p. 25), creating new insights and knowledge.

Working digitally allowed us to employ new techniques that facilitated the thematic analysis process (Hacker et al., Citation2020). For instance, we found Google Drive incredibly helpful in allowing resources to be shared across projects, while also adhering to ethical protocols with regard to data sharing. In June 2021, SIG member Anna Tarrant facilitated a secondary data analysis workshop and introduced us to the online digital whiteboard tool, Miro board. The key questions posed to researchers in this workshop were:

How and to what extent does your data speak to each theme?

What are the key emergent findings from your projects in relation to this theme?

What opportunities might there be for working across datasets in the future?

Given the data we have on this theme across these projects, are there still any obvious knowledge gaps that deserve further research/policy attention?

In what ways would you like to collaborate with other projects in the SIG?

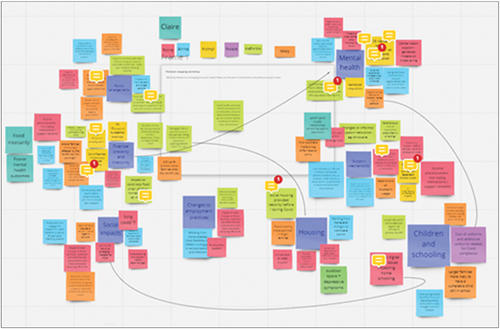

All working on the Miro board at the same time, each participating project had a different coloured sticky note and used these to add their key findings to the board (see ). Other people could add comments to these to show a connection to their own project findings. Eventually, we started grouping these around key emerging themes. As we did this live, the sticky notes kept moving around and being rearranged, looking a bit like worker bees moving around a space. While we were doing this, participants talked over Zoom, extending discussions as new thoughts popped up in response to the emerging research picture.

This way of working was inclusive and genuinely participatory, and led to not only a wider conversation around key interlinking themes and overlaps, but importantly also alerted us to gaps in our data and areas for future collaboration and exploration.

Dissemination

Feast et al. (Citation2018, p. 14) emphasise that the final stage of the synthesis process must prioritise the effective communication of findings. This is also stressed by Noblit and Hare, who state that ‘the worth of any synthesis is in its comprehensibility to some audience’ (Noblit & Hare, Citation1988, p. 82). When establishing guiding principles, we were also clear on the value of jointly agreeing on an approach to outputs that was fair and representative of involvement. This involved an inclusive mechanism for SIG members to propose analyses, other outputs, dissemination, and knowledge exchange activities, and was central from the beginning of the collaborative process. This involved sensitivity around publications, for instance, in terms of being careful to avoid ‘gazumping’ project teams by agreeing authorship in advance of analysis, and only publishing about shared sets of questions and analyses that constitute new forms of enquiry identified in the data synthesis process. Of significance here was timing; for instance, individual core projects published findings in various forms and at differing time points. Therefore, as a group we were careful to ensure that our joint work did not ‘clash’ with launches of key reports or outputs, and instead sought to amplify and share these within our own networks. This way of working was embedded within an ethos of collaboration over competition, or incidental co-operation over research, which is unusual in academic research and its inherent ‘publish or perish’ culture. This was an important guiding framework for our collaborative approach, but also a challenge to more dominant approaches and ways of working in academia.

Conducting ethical research into poverty and low-income, and particularly during the pandemic, meant we needed to try to create clear and effective chains of policymaking engagement and dissemination. A key value in synthesising our findings has been the ability to share key overall messages with policy and practice. As such, we recognised the need to maximise these opportunities and created a clear strategy for engagement. So far, we have contributed (and been invited to contribute) to several Parliamentary and think tank calls for evidence; given presentations to and attended meetings with Department for Work and Pensions staff; and produced joint statements on social policy issues, such as the suspension of the Universal Credit £20 uplift. Having an evidence base that represents over 4,000 parents and carers across the UK means that it is difficult for our findings to be dismissed as ‘one qualitative study’ or ‘a small sample size’. We built encouraging relationships with policy makers, who were interested in not only our findings, but also our virtual collaborative approach, and the possibilities afforded by this. We also worked closely with project partners CPAG to ensure our findings would be disseminated widely and effectively.

Learnings from our collaboration: thinking beyond the pandemic

Ultimately, this collaborative process of research synthesis has proved to be an important way of working together at a time when we needed to adhere to social distancing measures and were working remotely. It is clear that the values of our collaborative approach extend into the post-pandemic context, with significant scope to embed collaboration more firmly within academic contexts. Rethinking the way we conduct social research is of particular importance here. Digital participation enabled us to meet more frequently and across a broader geographical area than if we were working together in person, and also promoted more inclusivity in terms of the involvement of individuals for whom travel is difficult (for example, due to caring commitments or disabilities). In fact, working digitally enabled us to forge and nurture connections and a network that would likely not have been possible had we all been working in pre-pandemic times (Waizenegger et al., Citation2020).

In future collaborative efforts, recognising the importance of flexibility and responsiveness throughout is crucial. We learnt that it was essential to be mindful of the format of data that was coming in, and the original intentions of the research teams in collecting this data, to make sure we did not lose any vital details in the synthesis process. It was also necessary to identify the ‘right’ time to synthesise findings and agree on policy recommendations. This was a difficult balancing act and, following several discussions at our SIG meetings, ended up occurring in an organic way as we responded to parliamentary calls for evidence, and gave joint presentations, thus prompting us to identify key themes and recommendations organically.

It is important to emphasise that this collaborative approach has not been without its tensions or challenges. Urrieta Jr and Noblit (Citation2018, p. viii) neatly describe the potential realities of synthesising findings across several research teams:

‘Our colleagues went to work, and work it was, as synthesis is not all revelation. Rather it takes a dogged determination to search out all that can be found, to create decision rules about what to keep and what to set aside, to refine and reconceptualize what one is in fact addressing and what one is not, to read deeply and repeatedly, and then try to figure out what all the studies say as a group, and ultimately what one as a researcher thinks they say about the area of focus … Work, work, work. For all of us, though, all this work was worth it.’

Working with various research teams both inside and outside of academia requires a serious amount of planning, consideration, negotiation, and above all, time. The latter point of synthesis being time and resource intensive is emphasised by Davidson et al. (Citation2019) in synthesising projects as part of their ‘big qual’ approach. As we discussed earlier, much time was spent negotiating concerns around data ownership, outputs, and key messaging, which needed to be carefully thought through on an ongoing basis. It was important that we carefully managed this time intensive way of working to avoid potential burnout; this was particularly relevant given the crisis context of the pandemic.

Who is involved in collaborative research also needs to be considered. We were keen to go beyond academia, and beyond our own networks, to connect with researchers who might be interested in working together. However, there is a danger here of certain groups who are already marginalised in academia and social policy being underrepresented. For example, there is a growing and stringent critique of the whiteness of the academy (Arday & Mirza, Citation2018; Bhopal, Citation2018; Craig et al., Citation2019). This is inevitably tied to debates surrounding research on poverty, given that poverty disproportionately affects Black and minority ethnic households (Hall et al., Citation2017; Citation2021). Further, it is important to consider the potential difficulties of ensuring that early-career researchers (ECRs) can be meaningfully involved in collaboration. ECRs are often facing a casualised and precarious working environment (Jones & Oakley, Citation2018). Unrealistic workloads, fixed-term contracts and increased demands to demonstrate excellence across research, teaching, and impact can make calls to find time for collaboration seem unrealistic and unattainable, and as social researchers we must be mindful of these factors in any future collaboration.

Conclusion

Covid-19 forced us to significantly change the way we work as social researchers. Bringing the findings of our projects into conversation with one another has been enabled by digital platforms and tools, which allowed researchers from institutions and organisations across the UK to collaborate effectively and efficiently. Adapting Noblit & Hare’s, Citation1988) seven-stage process of meta-ethnography, we brought quantitative, qualitative, participatory, and creative methods into conversation with one another, in order to allow for a broader and richer understanding of the experiences of families living on a low-income during the pandemic. Flexibility, understanding, and communication have been key in ensuring that we conducted processes of research synthesis and dissemination in the most meaningfully collaborative way possible. This was achieved through developing a co-produced framework from the outset, exploring and forefronting the ethics of collaboration, and taking time to establish effective research relationships, while creating space for reflection and iteration of the collaborative approach. The solidarity and sense of community offered through the collective was welcomed by all as we navigated the difficulties brought about by Covid-19.

Ultimately, the pandemic encouraged us to make long overdue changes in academic practice, and has significantly changed the way we work as social researchers. Working collaboratively has had significant advantages in terms of communicating messages from our strong collated evidence base. In sharing our collaborative efforts with not only the wider research community, but also with practitioners, professionals, and those in positions of power, we hope to emphasise the possibilities, challenges, and importance of prioritising meaningful collaboration in researching poverty, beyond a crisis context. Our overarching ethics of care (to participants, and to our collaborators) allowed us to innovate and work in new ways, enabling us to rapidly generate impactful, policy-relevant research evidence. Collaborating in this way has meant that we were able to draw on each other’s networks, knowledge, and skills to communicate our findings effectively and meaningfully and to a broader audience than we might have been able to individually. As a result of working in this way, we gained a broader and richer understanding of the experiences of families living on a low income during the pandemic.

Going forward – and especially important in a post-pandemic context – we encourage researchers to seek opportunities to collaborate more, and for funders to support this work, creating spaces to do so. Alongside the strong ethical and practical reasons for doing so, there are also arguments that collaborative efforts can generate richer and more impactful knowledge bases. As suggested earlier, this is not without its difficulties; academia is wedded to neoliberal individual academic models that prioritise individual success and achievement, and these can be exclusionary for particular groups. These ways of working are especially ill-suited to poverty research, which should be more firmly orientated towards substantive policy improvement and improved knowledge bases, drawing upon participant-led expertise rooted in lived experience, rather than being contingent on individual career development.

The processes of collaboration, participation, and reflection detailed in this paper offer new ways of thinking not only about how we collect data, but also the legacy we would like our research to have. We would therefore emphasise the significant potential of working collaboratively to synthesise findings, spanning disciplinary boundaries and working across multiple methodologies, both within and outside of academia, and stress the importance of continuing to explore further opportunities for doing so in a post-pandemic context.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all members of the ‘COVID-19 and families on a low income: Researching together’ collective for their time, patience, collaboration, and solidarity during this project. Thanks also to all of the families involved in our respective studies for continuing to share their experiences during the incredibly difficult time of the pandemic. Additional thanks to Emma Davidson and Ros Edwards who gave up their time to provide invaluable expert methodological insights as part of a special advisory group. The Covid Realities research programme was funded by the Nuffield Foundation. The Foundation has funded this project, but the views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily the Foundation. Visit www.nuffieldfoundation.org

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kayleigh Garthwaite

Kayleigh Garthwaite is an Associate Professor in the Department of Social Policy, Sociology & Criminology, University of Birmingham. Her research interests focus on poverty and inequality, social security, and health, specifically investigating charitable food provision and food insecurity. She is the author of Hunger Pains: life inside foodbank Britain (Policy Press, 2016) and Poverty and insecurity: life in low-pay, no-pay Britain (Policy Press, 2012).She is a trustee of the Independent Food Aid Network.

Ruth Patrick

Ruth Patrick is a Senior Lecturer in the School for Business and Society at the University of York. Her particular interests include social citizenship and stigma, and the complex ways in which the shame associated with poverty and benefits receipt interacts with experiences and responses to financial hardship. Ruth led the Covid Realities research programme and is the author of For Whose Benefit: The Everyday Realities of Welfare Reform (2017, Policy Press).

Maddy Power

Maddy Power is a Research Fellow in the Department of Health Sciences, University of York. She currently holds a Welcome Fellowship. Her research interests centre around food aid and food insecurity in multi-faith, multi-ethnic contexts, including further research and publications on ethnic and religious variations in food insecurity. Her monograph ‘Hunger, Racism and Religion in Neoliberal Britain’ was published in 2022 (Policy Press). She is founder and former Chair of the York Food Justice Alliance, a cross-sector partnership addressing food insecurity at the local level, and Co-Chair of the Independent Food Aid Network.

Rosalie Warnock

Rosalie Warnock is a Research Associate in the School for Business and Society at the University of York. She works on the ‘Covid Realities’ and ‘Benefit Changes and Larger Families’ projects. Her research interests include: austerity, welfare bureaucracies, special educational needs and disability (SEND) support services, family life, care, and emotional geographies.

References

- Arday, J., & Mirza, H. S. (eds.). (2018). Dismantling race in higher education: Racism, whiteness and decolonising the academy. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Atkins, S., Lewin, S., Smith, H., Engel, M., Fretheim, A., & Volmink, J. (2008). Conducting a meta-ethnography of qualitative literature: Lessons learnt. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-21

- Bhopal, K. (2018). White privilege: The myth of a post-racial society. Policy Press.

- Bishop, L., & Neale. (2012). Data management for Qualitative Longitudinal researchers. Timescapes Methods Guides series. https://docplayer.net/11649704-Timescapes-methods-guides-series-2012-guide-no-17.html

- Brannelly, T. (2018). An ethics of care research manifesto. International Journal of Care and Caring, 2(3), 367–378. https://doi.org/10.1332/239788218X15351944886756

- Britten, N., Campbell, R., Pope, C., Donovan, J., Morgan, M., & Pill, R. (2002). Using meta-ethnography to synthesise qualitative research: A worked example. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 7(4), 209–215. https://doi.org/10.1258/135581902320432732

- Coverdale, A., Meckin, R., & Nind, M. (2021). The NCRM wayfinder guide to doing ethical research during Covid-19. National Centre for Research Methods. Retrieved from 5/July/21: /http://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/4401/

- Craig, G., Cole, B., & Ali, N. (2019) The missing dimension: Where is ‘race’ in social policy teaching and learning? Social policy association. Retrieved from 1/August/22 http://www.social-policy.org.uk/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/BME-Audit-Final-Report.pdf.

- Davidson, E., Edwards, R., Jamieson, L., & Weller, S. (2019). Big data, qualitative style: A breadth-and-depth method for working with large amounts of secondary qualitative data. Quality & Quantity, 53(1), 363–376. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-018-0757-y

- Dewaele, A., Vandael, K., Meysman, S., & Buysse, A. (2021). Understanding collaborative interactions in relation to research impact in social sciences and humanities: A meta-ethnography. Research Evaluation, 30(2), 179–190. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvaa033

- Doyle, L. H. (2003). Synthesis through meta-ethnography: Paradoxes, enhancements, and possibilities. Qualitative Research, 3(3), 321–344. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794103033003

- Feast, A., Orrell, M., Charlesworth, G., Poland, F., Featherstone, K., Melunsky, N., & Moniz-Cook, E. (2018). Using meta-ethnography to synthesize relevant studies: Capturing the bigger picture in dementia with challenging behavior within families. Sage Research Methods Cases. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526444899

- Garthwaite, K., Patrick, R., Power, M., Tarrant, A., & Warnock, R. (editors). (2022). Covid-19 collaborations: Researching poverty and low-income family life during the pandemic. Policy Press.

- Groot, B. C., Vink, M., Haveman, A., Huberts, M., Schout, G., & Abma, T. A. (2019). Ethics of care in participatory health research: Mutual responsibility in collaboration with co-researchers. Educational Action Research, 27(2), 286–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2018.1450771

- Hacker, J., Vom Brocke, J., Handali, J., Otto, M., & Schneider, J. (2020). Virtually in this together–how web-conferencing systems enabled a new virtual togetherness during the Covid-19 crisis. European Journal of Information Systems, 29(5), 563–584. https://doi.org/10.1080/0960085X.2020.1814680

- Hall, J., Gaved, M., & Sargent, J. (2021). Participatory research approaches in times of covid-19: A narrative literature review. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 20, 16094069211010087. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069211010087

- Hall, S., Mcintosh, K., & Neitzert, E. (2017) Intersectional inequalities: The impact of austerity on black and minority ethnic women in the UK. Women’s Budget Group and Runnymede Trust. Retrieved from 1/August/22: https://www.intersecting-inequalities.com/copy-of-report.

- Heyvaert, M., Maes, B., & Onghena, P. (2013). Mixed methods research synthesis: Definition, framework, and potential. Quality & Quantity, 47(2), 659–676. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-011-9538-6

- Howlett, M. (2022). Looking at the ‘field’ through a zoom lens: Methodological reflections on conducting online research during a global pandemic. Qualitative Research, 22(3), 387–402. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794120985691

- Hughes, K., & Tarrant, A. (eds). (2020). Qualitative secondary analysis. Sage.

- Irwin, S., & Winterton, M. (2011). Debates in qualitative secondary analysis: Critical reflections. Timescapes: An ESRC qualitative longitudinal study UK data archive. University of Leeds, London South Bank University, Cardiff University, The University of Edinburgh.

- Jones, S. A., & Oakley, C. (2018) The Precarious Postdoc: Interdisciplinary Research and Casualised Labour in the Humanities and Social Sciences: Retrieved from 1/August/22. https://hearingthevoice.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/WKPS_PrecariousPostdoc_PDF_Feb.pdf

- Lancaster, K., Rhodes, T., & Rosengarten, M. (2020). Making evidence and policy in public health emergencies: Lessons from COVID-19 for adaptive evidence-making and intervention. Evidence & Policy, 16(3), 477–490. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426420X15913559981103

- Lee, R. P., Hart, R. I., Watson, R. M., & Rapley, T. (2015). Qualitative synthesis in practice: Some pragmatics of meta-ethnography. Qualitative Research, 15(3), 334–350. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794114524221

- Markham, A. N., Harris, A., & Luka, M. E. (2021). Massive and microscopic sensemaking during covid-19 times. Qualitative Inquiry. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800420962477

- Neale, B., & Bishop, L. (2012). The Timescapes archive: A stakeholder approach to archiving qualitative longitudinal data. Qualitative Research, 12(1), 53–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794111426233

- Nind, M., Coverdale, A., & Meckin, R. (2021). Changing social research practices in the context of covid-19: Rapid evidence review. Project Report. National Centre for Research Methods. http://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/4398/

- Noblit, G. W., & Hare, R. D. (1988). Meta-ethnography: Synthesizing qualitative studies. SAGE.

- Olssen, M. (2016). Neoliberal competition in higher education today: Research, accountability and impact. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 37(1), 129–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2015.1100530

- Pratt, B., Cheah, P. Y., & Marsh, V. (2020). Solidarity and community engagement in global health research. The American Journal of Bioethics, 20(5), 43–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2020.1745930

- Rahman, S. A., Tuckerman, L., Vorley, T., & Gherhes, C. (2021). Resilient research in the field: Insights and lessons from adapting qualitative research projects during the covid-19 pandemic. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 20, 16094069211016106. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069211016106

- Sandelowski, M., Voils, C. I., & Barroso, J. (2006). Defining and designing mixed research synthesis studies. Research in the Schools: a Nationally Refereed Journal Sponsored by the Mid-South Educational Research Association and the University of Alabama, 13(1), 29. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2809982/

- Sime, D. (2008). Ethical and methodological issues in engaging young people living in poverty with participatory research methods. Children’s geographies, 6 (1), 63–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733280701791926

- Tarrant, A. (2017). Getting out of the swamp? Methodological reflections on using qualitative secondary analysis to develop research design. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 20(6), 599–611. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2016.1257678

- Thomson, R., & Berriman, L. (2021). Starting with the archive: Principles for prospective collaborative research. Qualitative Research, 14687941211023037. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F14687941211023037

- Urrieta Jr, L., & Noblit, G. W. (Eds.). (2018). Cultural constructions of identity: Meta-ethnography and theory. Oxford University Press.

- Voils, C. I., Sandelowski, M., Barroso, J., & Hasselblad, V. (2008). Making sense of qualitative and quantitative findings in mixed research synthesis studies. Field Methods, 20(1), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X07307463

- Waizenegger, L., McKenna, B., Cai, W., & Bendz, T. (2020). An affordance perspective of team collaboration and enforced working from home during covid-19. European Journal of Information Systems, 29(4), 429–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/0960085X.2020.1800417