ABSTRACT

This article discusses a new interdisciplinary, mixed-methods approach to using data from the first British Birth Cohort Study, the National Survey of Health and Development (NSHD, 1946). It emerges from a collaboration between two historians of postwar Britain and a mixed-methods life course studies researcher. Our approach brings together cohort-level quantitative data with less well-known qualitative data from a sample of 150 participants’ original NSHD interview questionnaires to generate new perspectives on how macro processes of social change were experienced at an individual level and varied across the life course. The NSHD school-age and early adulthood sweeps included a series of open-ended questions relating to education, work, and social identities, which offer a sense of how participants responded to and understood the social transformations of the postwar decades within their everyday lives. This article explains our methodological rationale, before focussing on the wider analytical possibilities of our approach in relation to social mobility.

In 1968, Betty,Footnote1 a twenty-two-year-old working-class woman from Scotland, filled out a questionnaire for the 1946 National Survey of Health and Development’s Age-22 sweep. As a cohort member she wrote in detail about her personal struggles in finding work to match her educational qualifications, after providing other information on recent hospital visits and the cost of living. She ended her response by asking her reader: ‘Are you bored? You must be if you’ve been reading 5,000 of these little bits of people’s life’s details. Never mind, I’ve finished.’ The three oldest British birth cohort studies – the 1946 National Survey of Health and Development (NSHD), the 1958 National Child Development Study (NCDS), and the 1970 British Cohort Study (BCS) – offer unparalleled granular insight into the lives of around 40,000 individuals who were born, went to school, came of age, and grew old in Britain after 1945 (Ferri et al, Citation2003; Pearson, Citation2016). Qualitative material, like Betty’s, can be found throughout each study but until recently has received little attention from researchers (Elliott, Citation2013; Tinkler et al., Citation2021). Although often pithy in content and delivery, this material has the potential to reveal new insights into how cohort participants understood the world around them as they offered their own perspectives in response to cohort researchers’ questions.

This paper presents a new, cross-disciplinary, mixed-methods approach for utilising this previously untapped material in the British birth cohorts. For those responsible for designing the cohort studies, it has always been a priority to keep the lives of individual participants out of sight. Questionnaire data has been collected with the intention that it would be coded, aggregated, and analysed through quantitative methods to provide insights into aggregate patterns and trends. Yet with a growing number of historians starting to work with the cohort data, more emphasis is being placed on the need to understand these studies as historically situated (e.g. Elizabeth & Payling, Citation2021). Recent work by both historians and sociologists has sought to bring the lives that stand behind aggregated data sets into sharper focus as a means of positioning individuals as active agents, rather than passive subjects, within wider social transformations. Life course researchers have conceptualised that trajectories and outcomes (at both individual and group levels) are shaped by the interaction of five key factors: location in time and place, social ties to others, personal agency, variations in the timing of key life events, and life-span (biological) development (Elder et al., Citation2003; Giele, Citation2009). Drawing on these insights, we returned to the original questionnaires of the cohort studies in order to generate new perspectives on how the experience of social change varied between individuals and across the life course.

Turning to the cohort studies and building on the work of mixed-methods life course researchers is key to meeting this ambition. We are an interdisciplinary team consisting of one qualitatively orientated life course researcher and two historians (working on the ESRC-funded research project, Secondary education and social change in the United Kingdom since 1945 [SESC]), drawn together by the obvious synergy between postwar social history and life course research. We have used this qualitative material, in combination with the cohort studies’ abundant quantitative data, to construct richly detailed narrative ‘pen portraits’ charting the educational, occupational, and class-related trajectories of approximately 150 purposively sampled members from the 1946 cohort.Footnote2 These pen portraits are not meant to be representative of the broader cohorts, but instead are designed to focus on key groups of interest within SESC’s wider research. The life trajectories we track shed valuable light on the relationship between education and macro-processes of social change, such as social mobility, which transformed British society in the decades after the Second World War and have formed the focus of much cohort research to date. In this paper, we outline our methodology and discuss the potential value of our approach, for both historians and life course researchers, to nuance our understanding of core social trends revealed by the cohort studies’ quantitative data. To illustrate these possibilities, we focus on the insights gained from our pen portraits into the relationship between rising education levels and social mobility.

Locating the lives behind aggregated data

Although much of the birth cohort data is quantitative, it is not without narrative potential, as Jane Elliott has argued (Elliott, Citation2005, Citation2022). Longitudinal researchers have long been interested in charting the individual lives underlying wider datasets by situating them within, and tracking them across, specific contexts of historical time and place (Elder, Citation1974), and understanding the interactions of life course factors such as agency, social ties, and the timing of events and transitions (e.g. Brannen et al., Citation2004; Elder et al., Citation2003). We would contend, as historians, that it is also essential to historicize the data itself and thus recognise the contingency that led to this particular information being collected in the first instance and, equally, what was not recorded. As Mike Savage and Helen Pearson have both skilfully plotted, the Birth Cohort Studies were products of new modes of social science thinking and enquiry after 1945 that argued by tracking a representative sample of individual lives over time, it would be possible to map macro social trends across the whole of British society (Pearson, Citation2016; Savage, Citation2010). When analysing longitudinal data, some researchers have adopted a person–centred rather than variable–centred approach, or have successfully combined these two approaches in mixed-methods studies to offer greater ‘breadth and depth’ in explaining life course outcomes (Clausen, Citation1993; Davidson et al., Citation2018) or to integrate subjects’ own perspectives on their life trajectory (Giele, Citation2009). Recently this has been deployed to help ensure policy makers are more attuned to the needs and priorities of specific groups (Morrow & Crivello, Citation2015; Tavener et al., Citation2016).

Assessing the contribution of quantitatively – derived ‘life history narratives’ to their understanding of family wellbeing in the British Household Panel Study, Sharland and colleagues suggest that they add explanatory richness and thus provide valuable insights into the contributing factors underlying otherwise counterintuitive findings (Sharland et al., Citation2017). Even so, Carpentieri and Elliott (Citation2016) have cautioned that, in the absence of qualitative material providing cohort members’ own evaluative reflections and perspectives, quantitatively – derived pen portraits or life histories are less narrative than chronicle: we see what happens in the cohort member’s life, but we do not get that individual’s own perspectives on how and why it happened, and what that means to them (Carpentieri & Elliott, Citation2014: 120–21). Without the subjective insight that comes from qualitative responses it remains incredibly difficult to assess the meanings that study members ascribe to their experiences, and to understand the narratives that individuals themselves construct to explain their life trajectories including the causal mechanisms and turning points involved (Brannen et al., Citation2004: 5–7).

Perhaps for this reason, the cohort data rarely features in histories of the postwar period. Instead, historians have turned to data sources such as Mass Observation [M-O] (a social investigation organisation founded in 1937 to gather material on everyday life in Britain), oral history sources (such as Paul Thompson’s 100 Families study), and most recently rich field notes and interview transcripts produced by community studies researchers from the 1940s to the 1980s (for example, Abrams, Citation2014; Hinton, Citation2010; Langhamer, Citation2018; Lawrence, Citation2019; Sutcliffe-Braithwaite, Citation2018). In many instances, the ‘social-science encounters’ that generated these testimonies expose deep dissonances between vernacular and expert accounts of social change, something which the qualitative material in the cohort studies also has the potential to reveal (Lawrence, Citation2013, Citation2014; Savage, Citation2005). Rather than dismissing ordinary voices – as contemporary researchers were prone to do when they ran counter to their hypotheses – Jon Lawrence has urged historians to take seriously the ways in which they illuminate the relationship between material change and broader discursive shifts in the postwar decades, which combined to challenge entrenched classed and gendered hierarchies (Lawrence, Citation2017). Even so, for all they offer in terms of depth of insight into different local contexts and sociological questions, the kinds of sources mentioned above are invariably limited in scope, both geographically (largely urban and suburban, often only England) and in terms of respondents’ broader representativeness. Indeed, this was one of the principal frustrations that drew social science researchers – several of whom had emerged from the community studies tradition themselves – towards more quantitative work with larger datasets that could provide a representative, national profile (Savage, Citation2010, pp. 210–12; cf. Bryman, Citation2008).Footnote3

The British birth cohort studies do not suffer from these limitations of scope or representativeness, and offer the opportunity to construct life histories that incorporate both quantitative and qualitative data, as we show below. Our methodology builds upon a longstanding, but underappreciated, tradition within British birth cohort research, which has demonstrated the value of mixed – methods approaches to understanding better how participants’ changing everyday lives affected, and were affected by, wider outcomes over time. Pilling’s (Citation1990) study of NCDS children categorized as ‘born to fail’, blended quantitative analysis of the cohort data with a series of interviews with participants around age-30 to explain their life trajectories using a mix of their own words and quantitative analysis (Pilling, Citation1990). More recently, qualitative biographical interviews have been conducted with subsamples from the 1946 (Elliott et al., Citation2011) and 1958 (Elliott et al., Citation2010) cohorts. These interviews sought to elicit detailed narratives from study members and have facilitated qualitative investigations across a broad range of topics (e.g. Ashby & Schoon, Citation2012; Carpentieri & Elliott, Citation2014; Elliott et al., Citation2014; Franceschelli et al., Citation2016; Parsons et al., Citation2012). Tinkler and colleagues’ recent work with a sample of female NSHD participants has shown how individual lives can be ‘recomposed’ by augmenting quantitative data from successive sweeps with ‘scavenged’ qualitative responses that to date have attracted almost no attention from cohort researchers (Tinkler et al., Citation2021). Bringing these two elements of the cohort data together has the potential to show, in Rachel Thomson’s elegant formulation, how participants’ lives unfolded along both expected and unexpected lines, and in so doing to start building a narrative framework in which individual portraits can be deployed alongside macro quantitative analysis (Thomson, Citation2009).

Tracking mobile subjects

To illustrate our methodological argument in the remainder of this article, we concentrate empirically on one process of social transformation that has generated a vast amount of sociological literature and is attracting growing attention from historians: social mobility. Although important to keep in mind the distinction between absolute and relative mobility (Goldthorpe, Citation2016), those in the 1946 cohort were prime beneficiaries of the so called ‘golden age of social mobility’ – lasting from the 1940s to mid-1970s – which saw unprecedented (and unrepeated) numbers experience upward mobility as they moved from manual into white-collar occupations (Bukodi & Goldthorpe, Citation2011; Bukodi, Citation2009; Mandler, Citation2016).

Since the 1950s, social science researchers have highlighted the relationship between educational opportunities, outcomes, and social mobility. For the first time following the passing of the 1944 Education Act, all 11-year-olds would attend secondary school until the age of 14 (raised to 15 in 1947 and 16 in 1972). Policy makers were confident that universal secondary education would become the engine of a more socially mobile society by extending ‘the educational ladder of opportunity’ further into the working classes (Mandler, Citation2020). Although the British government devolved responsibility for the organization of secondary education to local authorities, it recommended a tripartite system (in reality more often bipartite) in which primary school leavers were sorted between different types of secondary school based on academic ability as measured through an 11–plus exam (Chitty, Citation2002). While percentages varied depending on locality, around 24 per cent of pupils attended a grammar school, 6 per cent a technical school, and the remaining 70 per cent a secondary modern. Grammar schools quickly established a reputation as the gateways to white – collar careers and the rewards of upward social mobility, even as parents and sociological researchers warned that they entrenched existing social – class privileges (Floud et al, Citation1956; Douglas et al., Citation1968; Douglas, Citation1958; Halsey et al., Citation1980; Mandler, Citation2014, pp. 13–16). An emphasis on the perpetuation of social differentiation and inequality through the selective, ‘tripartite’ system has remained a central motif in the historical literature on postwar education (McCulloch, Citation1998; Spencer, Citation2005; Todd, Citation2014: 216–35), and a focus of quantitative longitudinal research (Burgess et al., Citation2020).

Like so many changes after the Second World War, social mobility at once disrupted and reconfigured established categories and structures. Assessed through either occupation or income, it measures the linear trajectory from origin to destination: that is, on an occupational scale (preferred by sociologists) the difference between an individual’s position at occupational maturity and their father’s occupation measured on the Hope – Goldthorpe scale; or on an income scale (deployed more by economists), an individual’s income at occupational maturity compared to their father’s. Mapping this society – wide phenomenon has depended upon the collection of vast datasets, including the birth cohorts, which have allowed researchers to uncover interactions between variables and compare between and within cohorts. Recently, scholars have deployed quantitative trajectory charts to map the different phases of social mobility across the life course (Bukodi & Goldthorpe, Citation2019, pp. 40–46Tampubolon & Savage, Citation2012).

What none of this data tells us, however, is how it felt to be socially mobile; or, as historians have recently started to ask: how did individuals understand this process beyond a crude movement between occupational or income strata (Mandler, Citation2019; Todd, Citation2021) ? Recent efforts to explore this question have emphasized the intensely personal nature of becoming socially mobile in postwar Britain, which could be at once profoundly liberating and disorienting (Moran, Citation2023; Todd, Citation2021; Worth, Citation2022). Even so, it has not proven easy to combine the representative breadth found in large, aggregated datasets with the textural depth required for qualitative case studies. In developing the latter, historians have used a range of techniques – spanning extensive archival research, oral history interviews, and family biographies – to situate detailed individual narratives within wider generational frameworks. Yet, as some quantitatively oriented sociologists have cautioned, such approaches can leave generational composition feeling arbitrarily drawn and provide an insufficient foundation from which to extrapolate broader conclusions (Goldthorpe, Citation2022).

In this respect, social mobility is an analytical category that starkly exposes the gap between qualitative and quantitative research agendas, but also one that offers rich potential for bringing them together. Recent interdisciplinary qualitative work has made important steps in historicizing the experience of social mobility to show its contingent and varied nature, even for those who were most mobile in the sociological sense (e.g. Bertaux et al., Citation2017). Using data from the NCDS Age–50 life interviews, Savage and Flemmen explore how participants conceived of their social mobility, and life course more broadly, as a series of jags and interruptions, placing greater emphasis on the break points associated with marriage, family, and serendipity than on straightforward economic or occupational advancement (Savage & Flemmen, Citation2019). Valerie Walkerdine, Eve Worth, and Helen McCarthy have all stressed social mobility’s deeply gendered dynamics, cautioning against the privileging of the male life course model as has been the case in much social science research (McCarthy, Citation2020; Walkerdine et al., Citation2001; Worth, Citation2019). Interested in the gradations within elite careers in the present, Sam Friedman and Daniel Lauriston have used a mixed – methods approach to map the ways in which economic, social, and cultural capital intersect in everyday contexts to condition opportunities for career advancement (Friedman & Laurison, Citation2019).

This qualitative work demonstrates the necessity of being attuned to the subjective dimensions of social mobility (Friedman, Citation2016; Walkerdine et al., Citation2001). Scholars have framed this idea using a range of concepts, although consistently stress that individuals not only experience social mobility differently, but their capacity to become socially mobile depends upon a range of subjective resources. One way this has been explained grew out of the work of American modernization theorists in the 1950s, which posited that for an individual to become socially mobile, they first had to become psychically mobile (Lerner, Citation1957). Education was identified as a key disruptive technology (along with print, film, and communication) that could open new perspectives for individuals (Lerner, Citation1958). Writing in the 1980s, the Italian sociologist Diego Gambetta repackaged and redeployed the idea of psychic mobility to explain why some school leavers chose or were pushed down pathways that would expand future opportunities, whilst others remained constrained within narrower limits (Gambetta, Citation1987). In both uses, psychic mobility is understood as a necessary precursor to physical and social mobility, but as Gambetta makes clear often comes at a ‘psychic cost’ for individuals negotiating the fracture between origin and destination (Gambetta: 98; see also Friedman, Citation2014; Skeggs, Citation1997; Walkerdine, Citation2015).

Yet while a sophisticated literature has developed exploring the psychic costs of social mobility, less has been written on the factors that condition psychic mobility in the first place and thus explain how individuals conceive of, and decide upon, future pathways. Where scholars have explored this theme, they persuasively highlight the reflexive relationship between agency and structure, and psychological and contextual factors. In part this flows from a late – twentieth century rethinking of the category of selfhood, in which theorists argued for a more fluid sense of self, increasingly detached from traditional identity categories of social class, family, and occupation (Bauman, Citation1999; Giddens, Citation1991). Nonetheless, few sociologists and historians working in British contexts have been willing to accept the unconditional pre-eminence of the individual over wider social structures and have instead sought new ways to explore the relationship between agency and structure (Bynner, Citation1997). In outlining their theory of careership, Hodkinson and Sparkes argue that school leavers make career decisions based upon their ‘horizons for action’, which are informed by a mixture of socio-economic context, individual choice, and ‘serendipity’ (Hodkinson & Sparkes, Citation1997).

Historians of postwar Britain have also become increasingly interested in the ways that new discursive patterns, shifting understandings of gendered and classed norms, and changing material contexts affected the ways in which young people from all social backgrounds imagined new futures for themselves or were energized to the challenge the status – quo (Robinson et al., Citation2017; Todd & Young, Citation2012). These methodological shifts onto the subjective experience of social change have facilitated exciting new insights through the reanalysis of existing social science data sets, but as Goodwin and O’Connor observe, need to be historicized, just as they seek to historicize older more structural interpretations of the same data (Goodwin & O’Connor, Citation2005).Footnote4

We draw on this work to consider how subjective factors interacted with and informed social mobility in the sociological sense. This is not driven by an ambition to assert the primacy of individual agency and individual experience over deeper structural forces and broader social patterns, but rather to situate the individual as a social being embedded within dense relational networks comprising family, friends, community, and increasingly the state. In terms of their mix of data, coverage across British society, historical specificity, and the model provided for generational comparison, the cohort studies provide an unparalleled resource to explore how individuals recorded the ways in which their lives were changing over time and amidst wider processes of social change. Sometimes the latter registered acutely, with participants articulating a clear perception in response to interviewers’ questions, while in other instances these changes occurred beyond an individual’s immediate horizon of awareness, even as they were hinted at within their qualitative responses. By combining the granular quantitative data with the qualitative reflections, while situating an individual within the wider cohort, our pen portraits have the potential to reveal the mechanisms and influences that allowed some to imagine a different future for themselves in preparation for becoming socially and physically mobile, while others remained more limited by their formative experiences and context.

Constructing the sample and developing the pen portraits

Our approach to our NSHD pen portrait sample construction was purposive and target-driven, building on the affordances provided by the cohort’s rich collection of quantitative variables, plus the relatively large (compared to the NCDS and BCS70) number of qualitative questions asked of this cohort. The NSHD’s qualitative questions gave us insights into cohort members’ own perspectives and reflections, while the richness of the quantitative dataset enabled a much more targeted sampling strategy than would be feasible in a typical qualitative study, where fewer variables are available. However, this did not mean that the sampling process was without challenge.

Our sampling targets included gender parity (50 per cent male, 50 per cent female), alongside a good representation of each of the three nations covered by the NSHD: England (target sample of 60 per cent), Scotland (20 per cent) and Wales (20 per cent).Footnote5 Another target was to achieve a good mix of four different subgroups each representing roughly 25 per cent of the final sample: upwardly mobile (in terms of intergenerational social class); downwardly mobile; achieved a Higher Education (HE) degree; and school leavers (those who left school at the statutory minimum school leaving age, which was age 15 for this cohort). These subgroups were not meant to be nationally representative in terms of their proportions, for example we were not trying to represent the actual percentages of upwardly mobile and downwardly mobile cohort members. Rather, they were designed to provide an analytically rich mix of cohort members within each subgroup, which aligned with SESC’s wider research themes.

Table 1. Stage 1 key questions used for sampling purposes.

We pursued these targets in three purposive stages. The first stage was to identify NSHD cohort members who had responded to the three key survey questions that were of particular relevance to our research focuses. As detailed in , these questions – two open, one closed – captured cohort members’ expectations and attitudes in their teenage years and mid-20s about: their future employment options (variable JOC59, age 13), opportunities to improve one’s life over time (variable JOPA, age 15), and the (im)permanency of social class over the life course (variable CCAPP, age 26).

In identifying respondents to these three questions, we encountered our main sampling challenge: the relatively limited numbers of Scottish and, in particular, Welsh respondents to all three questions. Of the 1303 NSHD study members who responded to all three questions there were 1,067 individuals from England, but only 158 from Scotland and 78 from Wales. (This overall figure of 1,303 is 24 per cent of the original cohort at birth and 35% of respondents in the age-26 sweep.) Our initial plan had been to limit our sample to respondents who had answered all three of our key survey questions. This strategy did not cause problems for our English sample: drawing on 1,067 individuals, it was easy to achieve all our subgroup targets; however, it was impossible to do so for Scotland and Wales, without relaxing our sampling criteria with regard to our three key questions. We therefore adopted the following strategy for Scotland and Wales: where possible, we chose our final sample from among individuals who had responded to all three of our key variables. When this was not feasible, we expanded our sample to cohort members in Scotland and Wales who had: (a) answered the first (and most important) key question (JOC59, ‘Job child thinks he [sic] will do when leaving school or university’) and (b) answered one of the other two key questions. This expanded our sample pools for Scotland and Wales from 158 and 78 respectively to 291 and 131 [see ].

Table 2. Stages 1 and 2 of the sampling process.

Our second stage was to limit the above samples to individuals for whom we had all the data required to construct four subgroups of: (1) upwardly mobile; (2) downwardly mobile; (3) HE graduates; and (4) school leavers. At this stage, we were confident that we would have a sufficiently large sample from each country, so we opted to enrich the dataset further (and thus contribute to pen portrait development) by including a small number of additional questions on employment and social class [see Appendix 1 for all variables included at this step]. shows the number of individuals who responded to the questions included in stages 1 and 2.

The third stage was the selection of the targeted 150 sample members from the above group of 780. This stage involved the creation of spreadsheets showing each individual’s responses to all questions outlined in stages 1 and 2. After each individual’s responses were read, that individual was categorised by nation and gender, and as upwardly mobile, downwardly mobile, HE graduate or school leaver. In constructing these subgroups, we did not strive for the (probably impossible) goal of mutual exclusivity – for example, the ‘HE graduate’ group included individuals who could have instead been placed into the ‘Upwardly mobile’ group, and vice-versa. Following this categorisation process, all individuals’ records were then re-read and final sample selections were made. As befitting a purposive sampling strategy, these final selections were made on a subjective basis by the research team, with the aim of creating as analytically useful a final sample as possible. For example, when deciding which five upwardly mobile Scottish males would be in our final sample, we looked closely at a range of variables, and also considered the degree of mobility that each cohort member had experienced on the occupational scales used in the relevant study sweeps when comparing childhood social class (variable CHSC, collected in multiple years) with the cohort member’s age–36 social class (variable sc1543). We also gave particular consideration to variable JOC59 (Job child thinks they will do when leaving school or university, age 13), so that we could select a mix of individuals who as teenagers had envisioned a contrasting range of future professions, such as teaching, sport, and shop assistant.

shows the constitution of our final NSHD sample. We did not strive for a perfect gender and/or national balance within each subgroup, but rather considered those two variables at full – sample level. Nor did we strive for statistical representativeness. However, we did adjust our initial sample targets to reflect more accurately the overall composition of the NSHD and that cohort’s experience over the life course – in particular, our ‘downwardly mobile’ subgroup was reduced in size to reflect the cohort’s experience of general upward mobility (which was approximately four times more common than downward mobility). Overall, we sought to create a final sample that offered as much analytic utility as possible, by depicting a wide and interesting range of trajectories and experiences while very roughly approximating overall trends for the entire cohort. Although our final sample was small in relation to the overall cohort (approximately 3 per cent), the richness of the data available to us meant we could purposively capture a varied array of individual cases within each of our subgroups, allowing us to construct highly detailed pen portraits which could facilitate a person-centred analysis of core trends within postwar education and social change (Dumais, Citation2005).

Table 3. Final sample.

Following the sample creation process, data collection for the NSHD was carried out at the MRC Unit for Lifelong Health and Ageing at UCL. The original NSHD questionnaires were viewed as digitized pdf files. We worked on the questionnaires for all school – age sweeps and young – adult sweeps up to 1972, which are especially rich in qualitative material. 101 key data points for each participant were recorded from the original interview questionnaires onto a data – collection spreadsheet to allow comparison within the sample (further details can be found in Appendix 2). We recorded all open question responses, marginalia, and interviewers’ comments that appear in the questionnaires (Edwards et al, Citation2017). After completing archival work on the questionnaires, we linked this data to other coded data from later NSHD sweeps to track individuals across their life course.

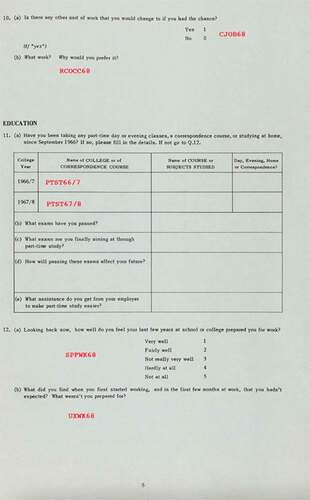

Figure 1. Page from NSHD H3 (1968) participant interview questionnaire. Participants were given freedom to offer open responses, but constraints were imposed through the space made available.

Ultimately, we were able to complete 144 of 150 NSHD pen portraits at the data collection stage due to metadata duplications. In piecing together these lives, we have been conscious of the need to protect cohort member anonymity (Wiles et al., Citation2008). The researchers did not know subjects’ names or contact details at the sampling stage, only their pseudonymised study ID numbers.Footnote6 When working with original interview questionnaires during the data collection stage all data was stored under pseudonymised ID numbers on secure servers and identifying information not recorded. The pen portraits were cleared by the LHA data team before release and all names used in this article are pseudonyms.

Pen portraits have long been used in person-centred research to give narrative structure to panel study data (Sharland et al., Citation2017; Sheard & Marsh, Citation2019; Singer et al., Citation1998). When constructing our pen portraits, we translated the 101 individual cells on the data collection spreadsheet into a document of written prose telling the life story of the individual in question. Twenty-six of the cells on the data collection spreadsheet were derived from purely quantitative variables and not directly transcribed, the remaining seventy-five cells contained transcribed qualitative material ranging from one line to a few paragraphs. In writing these pen portraits we are working against the traditional variable–centred, aggregate – focused logic of the cohort studies by disaggregating the data to draw out the people behind the variables (Pearson, Citation2016: 6–7).

The 144 completed NSHD pen portraits vary in length considerably, but the average word count of a pen portrait is 1355 words (range 801–2309 words). Their length is usually determined by how long the answers given to open questions were, which in our sample was not conditioned by class, gender, or educational background [see Appendices III & IV]. The open questions located on the back page of the 1968 and 1969 questionnaires are the most important source of subjective qualitative material in the pen portraits. These questions invited study members to write about themselves and their opinions on life in general.Footnote7 In our sample, women were more likely to answer these questions than men and they tended to write slightly longer answers.Footnote8

We are aware that the process of writing the pen portraits involved authorial choices. For example, a seemingly small decision such as choosing to use the word ‘felt’ (e.g. She felt she had much better opportunities than her parents because ‘there are more jobs about’Footnote9) introduces an emotional discourse that helps to underscore the distinction between questionnaire responses that were given subjectively by the respondent and ‘objective’ answers such as family size or test results (Daher et al., Citation2017). These authorial acts of interpretation were deliberately undertaken to highlight the subjective feelings involved in responding to the questionnaires and are used consistently across the pen portraits.

Care has been taken within the pen portraits to note whether answers were provided in written or spoken form, i.e. flowing directly from the pen of a study member or mediated through a third party. Mediated, spoken answers to quantitative survey questions also often produced instances of dialogue between the interviewer and study member, which are only revealed by returning to the original survey documents and by examining the paradata (for example, notes in the margins or participants’ annotations of fixed-choice questions) (Edwards et al, Citation2017: 1–5). These ‘social – science encounters’ were loaded with classed and gendered subjectivities (Lawrence, Citation2014). For example, we see this with Kevin’s interviewer who found him difficult to understand due to his ‘strong Tyneside accent coupled with a cold’.Footnote10 Interviewers also commented on the intrusion of family members, such as Daphne’s mother who sat in on her interview and, according to the interviewer, imposed a ‘Very marked parental Labour bias!… Finally I had to say that we did want [Daphne’s] views!’ These disturbances in the fiction of the neutral objectivity of quantitative responses are included in our pen portraits. They highlight the multiple, competing voices at work in the cohort data that are impossible to discern when aggregated.

We also hear from Youth Employment OfficersFootnote11 [YEO], teachers, and parents within the NSHD pen portraits. Structural choices made within the construction of the pen portraits allow us to arrange the data to point to significant harmonies and disharmonies between parental and children’s expectations of their educational outcomes. For example, when the NSHD study members were aged fifteen (in 1961) they were asked ‘What job would your parents like you to do?’.Footnote12 On a separate questionnaire in the same sweep parents were asked what job the child was going to take and what job they thought they were best fitted for and should do.Footnote13 Assembling these answers alongside one another in the pen portraits shows the degree to which parents and children were in (dis)agreement about future plans and how this changed over time.

Becoming socially mobile after 1945: the NSHD pen portraits

What do the 144 life stories contained in our NSHD pen portraits tell us about the experience of social mobility in Britain since 1945? Assessed either by occupation or income, this was an upwardly mobile cohort (Bukodi & Goldthorpe, Citation2019). Alongside the introduction of universal secondary education, the decades after 1945 saw the growth of white – collar positions in the expanding welfare state and political consensus around full employment. Subsequently, by the early 1970s, when the NSHD study members were in their mid – twenties, over 40 per cent of men worked in the salariat, compared to under twenty per cent before 1939 (Mandler, Citation2015: 5–6). But examining people’s experience of mobility in the 1946 pen portraits complicates this picture. Working closely with the qualitative material reveals that social mobility was subjective and contingent, framed by an individual’s active relationship with the survey and the historical circumstances under which they responded.

The NSHD was interested in finding out how participants understood changing class identities and the ways in which social mobility reframed family narratives. Cohort members’ qualitative responses, which have not featured in multivariate accounts of social mobility among the 1946 cohort, have the potential to thicken the conclusions we draw from the quantitative data in significant ways. In 1972, the study members were asked ‘Which social class would you say you were a member of? And which social class would you say your family were when you were young?’ The majority of our sample − 65 per cent (48 women and 46 men) – saw themselves as having stayed in the same social class since childhood. Only 24 per cent (17 women and 17 men) saw themselves as having achieved upwardly mobility. Yet according to quantitative measures, 53 per cent (77 cases) in our sample moved up at least one level on the seven – grade social class scale and only 25 per cent (36 cases) remained stable.

The qualitative responses help explain this gulf between objective and subjective descriptions of social mobility. Rather than conceptualising mobility in terms of the prevailing sociological model of social class, study members answered this question with reference to their own vernacular categories, which ranged from standard ‘middle class’ and ‘working class’ to answers such as the ‘the inbetween class’ and the ‘university class’. The 1972 questionnaire built upon these answers further by asking participants an open question (which was then backcoded): ‘What kinds of things would you say help people to “get on in the world”, nowadays?’ In response, 61 per cent (43 women and 45 men) in our sample mentioned education, training, qualifications, or school in some part of their answer. Indeed, the most frequently mentioned word in the answers was ‘education’. According to the original coding scheme, 58.8 per cent of all study members who answered this question mentioned ‘Education, training, travel, what you know’ as one of their ‘things’. This prevailing faith in education as the key driver of social mobility reflected longstanding assumptions within British society (Martin, Citation1954, p. 74).

Thus, despite the fact that in objective terms this cohort experienced upward social mobility not primarily through new educational opportunities but through a changing labour market (Bukodi & Goldthorpe, Citation2019), they predominantly saw themselves as a cohort whose class identities had not changed and whose hopes for ‘getting on’ lay in education. Our pen portraits help to explain this dissonance. They suggest how individuals managed social change across their life course by turning to local, familial, and personal resources (see also Goodwin & O’Connor, Citation2005). In particular, we can see the reflexive relationship between psychic and social mobility, and what brakes (and accelerators) were put on these processes by external factors, notably geography and gender. While these variables are available for purely quantitative research, the pen portraits disclose the study members’ own cumulative awareness and negotiation of these factors as their lives unfolded.

Building on long–recognised links between social and spatial mobility (Gunn, Citation2022), recent longitudinal research has highlighted how geographic advantage and disadvantage can ‘linger’ within individual trajectories (Brannen et al., Citation2004; Hecht & McArthur, Citation2022). Using quantitative methods, region has also been identified as decisive in the NSHD study members’ life courses (Murray et al., Citation2019). Within our sample, over half (55 per cent) of the study members made no move between age 13 and age 36, 12 per cent moved to an adjacent region in the same nation (i.e. England, Wales, Scotland), 6 per cent to another region in the same nation, 10 per cent moved to another nation, and 17 per cent were unknown.Footnote14 In general, women moved more than men, due to moving for their husbands’ work, and, reflecting wider trends, grammar school leavers were more likely to move further than secondary modern leavers, due to attending university and/or pursuing professional careers. Beyond these crude patterns, the pen portraits reveal the calculations made by study members as they became gradually aware of the impact of geography on achieving their interlinked educational and professional goals. The pen portraits capture study member subjectivities at each fixed moment, rather than in a retrospectively narrated process of becoming socially mobile.

Within the non – movers group (79 cases), 54 per cent were male and 46 per cent were female, 33 per cent were middle class and 67 per cent were working class. Daphne from County Durham, mentioned earlier for her pro – Labour mother, was one of the working – class women in this group. She attended a girls’ Catholic grammar school and left at age sixteen after failing several ‘O’ Levels. After four years of office work, Daphne began nursing training and at age 26 expressed satisfaction with her career choice, writing ‘I suppose I would like to marry if I met the right person, but at the moment I feel that my job comes first & is more important’. Daphne ultimately became a State Registered Nurse, a significant professional leap for the daughter of a domestic and sanitary worker. Yet at two separate junctures Daphne had the opportunity to take up more education or training (at age 16 for a place at a local College of Art and at age 24 she considered a postgraduate nursing qualification). But her pen portrait reveals that the cost and risk of living away from the parental home stopped her from pursuing these opportunities. In her late teens and early twenties, Daphne was consistently aware of her responsibility to ‘support the home’ and listed her daily bus fare as a significant expense. Her only complaint about nursing in 1968 was the wages, telling the survey one year later that she was looking forward to a 20 per cent salary hike. Despite further educational opportunities arising, Daphne’s psychic mobility was constrained by concrete material and gendered concerns that kept her in North East England. Daphne’s upward social mobility was ultimately derived from her grammar school place and nursing career. She continued to identify as working class and thought social class differentiation was ‘ … really a question of money. It’s certainly not the people themselves it’s what they’ve got behind them in capital’.

In contrast to Daphne, Brynn’s pen portrait shows how becoming psychically and physically mobile in his early twenties could facilitate upward mobility in spite of educational disadvantage. Born into a working – class family in semi – rural North Wales, Brynn left his mixed – sex, non – selective secondary modern school at fifteen (1961) with no qualifications and became a farm worker. By 1968, Brynn (age 22) was still doing farm work but wished he could change to ‘any trade’, something with ‘More security and not as boring as I would be forced to use my nut’ [i.e. his mind/brain]. Looking back, he wrote that if he had his time again, he would leave school at age twenty and attend a College of Art. He explained:

I didn’t think when I was 15 that I was capable of much except labouring but I have more confidence in myself now. I dought [sic] whether many young people of 15 do know what they want. I am quite satisfied with what I have but sometimes I get disapointed [sic] with myself for not taking advantage of the chances I had. I know I could have done a lot better for myself, and only have myself to blame.

Brynn associated his chances of progressing in life with his own emotional growth as much as with gaining educational qualifications, both of which he felt were constrained by his geographic immobility. Brynn also shared intimate details about his failure to make emotional connections with women. Soon after writing, Brynn enrolled in a vocational training course and got engaged. He left North Wales, following his fiancée to a city in the north west of England, where he subsequently pursued vocational training at a Polytechnic.

Brynn’s move was not uncommon in the 1960s, when labour migration from Wales to England represented a well – trodden path (Pooley & Turnbull, Citation1998: 51–192); however, it was more unusual in the sense that it precipitated a re – entry into education, which in turn supported future career progression. He was in the tiny minority of lower – educated men in our sample whose geographical mobility between age 13 and age 36 involved a move between nations, suggesting his psychic, geographical, and social mobility were profoundly interlinked. His growing frustration with the limits of his work and desire to disrupt his established life and emotional patterns nurtured his psychic mobility. Brynn was eventually able to turn his aspirations for a different type of life into reality by leaving his local area, with its constrained labour market, to somewhere that offered more diverse opportunities. In quantitative terms, Brynn’s social class position was four steps higher than his fathers (from 6. Semi-routine to 3. Intermediate). Yet his pen portrait captures the complexity of personal experience that this change entailed.

Joining the armed forces as a way of travelling and becoming geographically mobile features heavily in the pen portraits, especially for men. It was a more instant and culturally available resource for psychic mobility than Brynn’s gradual self–realisation. In the late 1950s, schoolboys knew that joining the Army, Navy, or Royal Air Force (RAF) would, in the words of 13-year-old Daniel, allow them to ‘see the world’ – a promise made in recruitment propaganda since the aftermath of the First World War. Coming of age at the very end of National Service recruitment, boys in the 1946 cohort would have grown – up expecting to undertake some form of military service (Vinen, Citation2014). Even after the end of National Service, a career in the armed forces could still hold an appeal that cut across class backgrounds. For those without qualifications, and often from working class homes, it could provide a pathway beyond the limits of familiar horizons (Parr, Citation2018: 27–57). While for middle – class boys, especially, the military represented a compensatory route to education, prestige, and travel when they had not achieved a grammar school place. We see this in the case of Ivan, who was born into a middle-class family in Yorkshire. Ivan went to a boys’ independent preparatory school until he was aged 13, after which he transferred to a mixed secondary modern school after failing to qualify for a grammar school. At age 13, he wrote of joining the RAF: ‘I think that it is a very exciting job. And you travel all over the world’. After leaving school at 16, Ivan took up an RAF apprenticeship and Technical College place, eventually relocating to the South West of England. Norman, a middle – class boy from Sussex who went to a mixed – sex secondary modern school was similarly able to realise his 13–year – old hopes for military service. He left school at age 15 and entered the Navy as a Junior Engineering Mechanic. At age 22, he looked back on his choices with mixed feelings. He wished he had gone to College before joining the Navy, thinking he had been ‘too keen’ to join. Yet he also listed all the countries he had visited, and wrote:

I feel that this has helped considerably in broadening my outlook on life and after learning to accept discipline in the navy I have found the life good. The course I’m on now leads to the highest rate on the lower deck, and there are openings enabling me to try for a commission if I want to.

In his own words, Norman linked his sense of personal growth to his geographical mobility, which had in turn been the driver of his educational and professional progression. Both Norman and Ivan were in our downwardly mobile sample subgroups based on the quantitative measures, yet their pen portraits bear no qualitative trace of this. They reached early adulthood hopeful, broadly satisfied in life, and both saw their chances of ‘getting on’ as better than their parents.

Such pathways were possible for women, too, but were much rarer. Vera, for example, used the military to carve out a professional career in nursing after attending a secondary modern school. But women, especially grammar – school leavers, were more likely to focus on learning languages or teaching as a route to geographical mobility. From their mid – twenties, several men and women also entertained fantasies of emigration, as a result of frustrations with ‘getting on’ in life in 1970s Britain (Smith, Citation2021). They all complained to the survey that working hard went unrewarded, especially for the young, yet few took the steps to convert this dream into a reality. Dennis, a working – class secondary modern leaver from the West Midlands, did achieve his goal of emigrating to Canada by 1972 (although he is classed quantitatively as a non – mover, because he had moved back to the West Midlands by mid – life). Dennis’s pen portrait is the longest in our sample (2309 words) precisely because he wrote in detail as these plans developed. He felt strongly that Britain offered inadequate educational opportunities and was haemorrhaging talent. Yet he also saw that he had made the best of a broken system for himself via an engineering apprenticeship and by 1968 Dennis even owned a sportscar, a status symbol that he acknowledged self – reflexively in two separate responses.

The possibility to read into conspicuous silences in the pen portraits is a further reason why such qualitative data is essential to understanding social mobility. Dennis’s pen portrait, with its long ruminations on the shortcomings of the British education system, underscores how ignorant male study members were of the deeply embedded gender inequalities within that system. The lack of ‘day release’ training for juvenile girls and apprenticeships in traditionally feminised sectors was an endemic problem in Britain’s postwar labour market that disproportionately affected working – class girls who attended secondary modern schools (Blackstone, Citation1976). In the pen portraits of women, we find much more awareness of this structural inequality, accumulating over time (Carter, Citation2023). Taken as a whole, the seventy-three female pen portraits underscore how gendered the experience of social mobility was for the 1946 birth cohort, in accordance with trends in the recent historical literature (de Bellaigue et al., Citation2022).

Working – class girls who attended grammar schools (17 cases in our sample) are perhaps the most salient group to examine in this respect. Marjorie, for example, was born in North East England to working – class parents, although her father had a skilled engineering job and they owned their own home. She secured a place at the girls’ selective, academic grammar school that her parents had hoped for. At age 15, she told the survey that she was hoping to get a job in pharmacy or industrial chemistry, explaining ‘I enjoy sciences and would like to work with them’. She felt she had much better opportunities than her parents because ‘there is more choice particularly for girls’. When asked by the survey to think intergenerationally, Marjorie’s psychic mobility was positively fuelled by gendered social change, but this expansion of choice for girls still operated within clear cultural limits. While this generation of female grammar school leavers tended to have more choice in terms of employment options and opportunities for further education than the one before them, many ran into the same structural barriers once they started families or began to progress towards higher status work roles (McCarthy, 227–59). Although she did well in her ‘O’ Levels, Marjorie was unable to take up a place at her chosen Redbrick university to read Chemistry because she failed her ‘A’ Level in Physics.Footnote15 Instead, she took an apprenticeship with a large pharmacy company that facilitated her to study for a BPharm degree at a Redbrick university in the Midlands.

By the end of her studies Marjorie had become frustrated with her degree course. She felt it should be reframed as a professional qualification but ‘a handful of academics wish to make into a degree course’. Indeed, she thought that her university was ‘trying to become another Oxbridge, e.g. gowns and rule about staying 3 nights per week in term’. It is estimated that there were fewer than one hundred female university graduates in the 1946 cohort as a whole, and they were all caught up in a ballooning university system that was poorly equipped to support them (Dyhouse, Citation2006).Footnote16 Within the pen portraits of the twenty-three women with degrees in our NSHD sample, six were critical of their university or course, six mentioned experiencing depression or nervous problems, and ten wrote about being on a path to self – discovery and maturity via higher education. Marjorie is therefore just one example of how women of her generation struggled to find satisfaction and fulfilment throughout the complex process of university – driven social mobility (Crook, Citation2020, p. 212; Mandler, Citation2015).Footnote17 As a working – class girl her aptitude for science was channelled away from male – gendered routes such as engineering, research, or medicine, into a vocational, applied scientific pathway. In 1966, the year after Marjorie started her degree, women accounted for c. thirty three per cent of all pharmacists and dispensers in England and Wales but only c. six per cent of chemists.Footnote18 Marjorie continued to view her educational journey through a gendered and classed vocational lens, and felt alienated by the middle – class academic culture that she instantly associated with ‘Oxbridge’.

Although Marjorie benefited from the key educational factors associated with the unprecedented opportunity for upward social mobility available to the 1946 cohort (grammar school, university), we see from her perspective how fraught that pathway could be for women seeking to find a place for themselves in this new landscape. Marjorie’s adulthood social class position was three steps higher than her father’s (from 3. Intermediate to 1. Professional), but at each stage her ability to capitalise on her hard work and to realise her psychic mobility was kept in check by her gender. Marjorie was engaged by the time she graduated and only worked as a pharmacist for a short period before getting married. By 1972 she was living in the South East of England, married with one child, and was not in paid work. The pen portraits of those women that retained their careers after marriage reveal a strained and delicate balance between home and work, with success hinging on access to childcare, supportive spouses, and the domestic labour of other women (Giele, Citation2009; McCarthy, Citation2020: 261–65). Others, like Marjorie, traded in their education for married life and reframed their hoped – for social futures around shared marital ambitions such as emigration or entrepreneurship.

This brief discussion of our pen portraits demonstrates how they can be used to significantly enhance our understanding of social mobility by using the subjective perspectives of study members themselves, only accessible because the NSHD includes a relatively rich array of qualitative open question material complementing the quantitative data. Geographical and gender advantage have long been acknowledged as crucial to social mobility (Brannen, Citation2003). It is therefore valuable to know how individuals negotiated these factors in their everyday lives. In our study, geography and gender have indeed emerged as decisive and formative factors impacting individual psychic mobility. Not only were study members aware of these factors, they made a range of calculations and took actions, or at least engaged in discourses, to mediate them. Their attempts were not always successful. But when they were, such as in the cases of Brynn and Dennis, it could result in new educational opportunities and upward social class mobility.

We also gain precise insights into ‘agency within structure’ (Diewald & Mayer, Citation2009, p. 8) in women’s lives in the pen portraits. For example, by capturing Marjorie’s distaste for her degree course, we get a sense of her own socially – mediated proclivities and interests, and are better able to understand the particular processes through which she herself self – reflectively enacts her own agency (Verd & Andreu, Citation2011). Meanwhile Daphne, whose vision of the British class system hinged on financial capital, fixated on the poor financial rewards of nursing, despite its cultural status as a prestigious profession for working – class women in postwar Britain. Even in the act of making disclosures to the survey, women were trying to shape their own lives within the constraints and opportunities available to them.

Person–centred research and social mobility

These pen portraits provide a window onto the rich complexity of cohort members’ lives, illustrating some of the ways that geography and gender interacted with education and employment to influence experiences of social mobility for the 1946 cohort. Crucially, they offer a means to break beyond a key limitation in much cohort research: in using educational and childhood experiences to explain adult outcomes, participants are often studied as ‘adults in the making’ rather than in a way that takes seriously how they ‘experience their lives in the here-and-now’ as children and young people (Elliott & Morrow, Citation2007, p. 4). Subsequently, the possible causative factors identified as explaining long term outcomes are typically limited to those which are measurable by quantitative means. By affording insights into the complex pathways and processes through which geography, gender, education, and employment have interacted in different individuals’ lives, the pen portraits are valuable to life course researchers as well as historians.Footnote19

A person–centred approach to life course data adds significant value for researchers seeking to develop a richer understanding of the individual pathways and processes underlying aggregate – level findings. When such an approach includes qualitative data, it also affords insights into cohort members’ reflections on those pathways and processes. Because we were able to draw on the cohort studies’ combination of open and closed survey questions, our work goes beyond etic or researcher – constructed understandings of study members’ experiences. By combining the British cohort studies’ quantitative data with cohort members’ own subjective reflections ‘from the inside’ (Thompson et al., Citation1990, p. 1), we are more fully able to realise the ‘narrative potential’ inherent in quantitative longitudinal studies (Elliott, Citation2005: 60–75).

Our approach thus offers contributions to life course theory by illuminating some of the ways in which the key elements of the life course framework – particularly historical time and place, social context and ties to others, and personal agency – interact. The material from the cohort studies is especially useful in providing intergenerational and relational perspectives. For example, drawing on Julia Brannen’s wider insights, we see how ambivalences with parental expectations often emerged once the study member started work at the point when they were asked to reflect upon their school leaving choices, rather than when they were deciding on future jobs (Brannen et al., Citation2004; Brannen, Citation2003). Such findings complement the cohort studies’ valuable quantitative literature by offering detailed insights into the intersection of the personal and the structural (Diewald & Mayer, Citation2009; Verd & Andreu, Citation2011; Wright Mills, Citation1959). Person–centred research may thus also contribute to the cohort studies’ policy value, by illustrating the concrete social and psychological processes through which individuals or groups respond to structural opportunities and constraints (McLeod & Thomson, Citation2009, p. 62).

Social and cultural historians have also long stressed the need to understand better the relationship between individual agency and wider structures in conditioning social change. In an effort to open up new perspectives on the everyday lives and contemporary thought worlds of a broader range of ‘ordinary people’ in the post-war decades, historians have started to reanalyse qualitative social science sources. This work has transformed how historians think about the reflexive relationship between collective experience (forged through broad categories of class, gender, age, and ethnicity) and individual subjectivity (people’s conception of themselves). It is perhaps surprising then that so few have turned to the cohorts when writing their own accounts of this period. In part, this can be explained through diverging disciplinary norms and ambitions (Panayotova, Citation2019: 1–28), but it also reflects a prevailing sense among many historians that the cohort studies are primarily quantitative resources, lacking the qualitatively rich personal narratives and testimonies that have provided powerful new insights into how individuals experienced and processed social change in the postwar period.

We have argued here that adopting an interdisciplinary, mixed – methods approach has allowed us to integrate the qualitative and quantitative material from NSHD to reconstruct the individual lives behind the cohort data. Our pen portraits add important subjective meaning to the wider processes of social change that are so central in historical and sociological accounts of postwar Britain. Prevailing explanations of social mobility as a historical phenomenon stress the relationship between origin and destination but, as this article makes clear, to comprehend both the transformative capacity and limits of social mobility, we must be as attuned to the journey in between. Drawing on Gambetta, Peter Mandler reminds us that a reoriented focus on the ‘historically specific, dense complex of mechanisms’ that made social mobility possible for some, but not others, can offer insights into causality that go beyond those obtainable by statistical analysis alone (Mandler, Citation2019, p. 104). Quantitative explanations of social mobility have tended to emphasise a causal link between education and upward mobility, or more recently separated them entirely; qualitative approaches allow us to decompose social mobility into its constituent dimensions.

By bringing the individual behind the data back into focus, the pen portraits allow this process to be mapped across the life course, plotting the moments in which horizons seemed to broaden but also when traditional constraints could draw them in again. Reconstructing the data in this way provides a multi – perspectival position that is rarely available when reanalysing static social surveys. The lifelong and life – wide perspective of the pen portraits allow us to zoom – in on individual moments in people’s lives (through the lens of the sociologist), but, crucially, lets us look forwards and backwards with them across time, to early – life origins and mid – and later – life destinations. In the moment of reflection that each sweep imposed, participants were asked to consider the past (events since the last sweep or differences between themselves and parents), the present (relationships, attitude towards authority, schoolwork) and the future (plans, ambitions, fantasies) together.

We see here in stark terms the gap between expectation and experience, but it is the qualitative material that offers intimate fragments of what this gap meant to different individuals at different times. At once prospective and retrospective, this data not only sketches a narrative in the sense of linear event chronology that ranges across time and space, but also documents a process through which individuals were asked to generate accounts of their lives that brought together intention, cause, and effect into a coherent sequence and which they had a chance to update or revise at regular intervals. While lacking the density of qualitative testimony found in extended interviews, the dynamic nature of the cohort data offers the important advantage of being able to hear how the everyday experience of social mobility unfolded over time. This, as Lynn Abrams explains, is a fundamental component of autobiographical structure and entails an ongoing reflexive interrogation that is integral ‘to the late modern project of self – articulation and self – realization’ (Abrams, Citation2014, p. 14). Through the pen portraits, we are offered multifaceted and conditional accounts of what it meant to be socially mobile in Britain after the Second World War. We start to discern the cohort members as autonomous subjects embedded in everyday relational networks and as active citizens navigating the institutions and structures of power of the welfare state.

We are conscious that our pen portrait approach presents challenges and limitations of its own, and stress that its validity rests upon the vast amount of groundbreaking quantitative research that the cohort data has made possible. Firstly, the unevenness of the data between cohorts makes cross – cohort comparison work highly challenging. This article has highlighted the richness and possibilities of placing the life of NSHD participants into narrative form (especially using the previously unheralded early sweeps, c. 1955–1972), but this has proved far harder with NCDS and BCS70, which never provided such scope for open questions and answers. Without text – rich material, pen portrait narratives produced through closed questions alone risk becoming overly repetitive and frustratingly one dimensional for researchers seeking to understand the complexities of individual lives (Elliott, Citation2005: 72–4). Secondly, the insights gained are necessarily limited by the questions participants were asked. For example, unlike in the NCDS and BCS70 school – age sweeps, NSHD showed little interest in leisure pursuits and popular youth culture. Subsequently, this crucial dimension of adolescent identity formation was largely absent in the qualitative answers, and thus our pen portraits, even though extensive historical and sociological research has shown its central importance in young people’s lives (Bynner et al., Citation1997; Osgerby, Citation1997; Tinkler, Citation2020).

Conclusion

While education and social mobility has been the focus for this article, the pen portrait method when applied to the NSHD specifically could be used to add similar subjective and longitudinal depth to many other processes of social change that are of interest to historians of post–1945 Britain, including, but not limited to, immigration and emigration, religion and secularisation, marriage and family life, and mental health. Our person–centred approach to the British cohort studies adds to previous quantitative findings generated from the cohort data by providing insights into the processes through which these factors interact in individual lives. In this article, we used some of the pen portraits to illuminate the processes underpinning social mobility, within which we see the interaction of specific empirical factors, such as region, and cultural expectations surrounding gender norms. The pen portraits also shed light on key theoretical principles of life course research, such as historical time and place, agency, and the timing of key life events.

The research has highlighted the challenges of working across disciplines and within the necessarily stringent ethical and data protection frameworks which are essential to protecting the anonymity of participants. While the data teams at the MRC Unit for Lifelong Health and Ageing and Centre for Longitudinal Studies (both based at University College London) have offered hugely appreciated support and guidance, their overriding responsibility remains the protection of potentially identifiable personal data and the integrity of what are ongoing research projects. Nonetheless, these challenges notwithstanding, without the combination of skills and disciplinary expertise that underpins this research, it would not have been possible to generate new insights into the lives of the ordinary people who stand behind the aggregated cohort data. In this respect, the approach we outline here underscores the possibilities not only of mixed methods approaches, but of interdisciplinary collaboration to offer new perspectives on data we think we know well.

Only rarely do quantitative studies that use cohort data acknowledge the historical circumstances of its production. This largely, and understandably, reflects the research priorities of social scientists, epidemiologists and other frequent users of the birth cohort studies. Nonetheless, as the pen portraits demonstrate, divorcing the coded data from individual lives located within specific historical contexts can mean that participants’ explanations of the challenges faced in their daily lives are eclipsed by larger macro processes (Østergaard & Thomson, Citation2020). This is not to suggest that the former are more important than the latter, nor to underestimate the hugely significant role played by structural inequalities in shaping individuals’ life trajectories. But we do argue that the postwar British birth cohort studies can be two things at the same time, with one not detracting from the other: datasets for policymaking and archives for historians.

The cohort data is socially constructed and highly contingent on its historical moment. It evidences individual research agendas, pressing contemporary issues, and hard-fought battles over funding (Pearson, Citation2016; Wadsworth, Citation2014). In this respect, historians’ perspectives can help elucidate how this data was shaped by the context in which it was collected and organized. Moving forward, this has wider implications for how we think about these kinds of large, publicly funded scientific projects, which in time will provide as important historical perspectives as they do contemporary or prospective insights: the cohorts should also be seen as national history enterprises. As the cohort members approach old age (the 1946 cohort will turn 80 in 2026), the data collected, stored, and repackaged into new forms about these individuals’ lives is of growing value to historians interested in understanding more about the experiences of ‘ordinary people’ in the postwar decades. The digitization of Mass Observation directives proved the catalyst for a rich harvest of new historical studies, something that is being replicated with ongoing work on the NCDS Age–11 life essays (Goodman et al, Does the language of 11-year-olds predict their future?, 2016–18Footnote20; Tisdall (Citation2021).

Finally, we stress that our unique exploration of the open questions across three postwar British birth cohort studies has revealed the pre – eminence of the NSHD as a veritable goldmine of qualitative birth cohort data. This data is an accident of history; from the early 1970s the NSHD was transitioning from an ‘education’ to a ‘health’ study, and broad open questions were often included to keep study members engaged while the survey worked out the direction of its future (Pearson Citation2016: 111).Footnote21 But these accidental open questions yield rich and unexpected responses, as have the more purposeful open questions included in studies such as the Australian Longitudinal Study of Women’s Health (Tavener et al., Citation2016) and the recent Covid–19 surveys targeted at UK cohort members (Carpentieri et al., Citation2020). The ‘big qual’ data produced by such questions are ripe for qualitative analysis, as in the current paper, and, using modern machine learning techniques, more quantitative approaches (Pongiglione et al., Citation2020). We strongly recommend a return to these types of questions in future sweeps of longitudinal cohort/panel studies (see also Thompson, Citation2004).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

JD Carpentieri

JD Carpentieri is Associate Professor of Social Science and Policy at the UCL Institute of Education. His research focuses on the use of qualitative and mixed methods to explore areas such as education, ageing, and the intergenerational impact of educational inequality. He has worked extensively with the British Birth Cohort studies.

Laura Carter

Laura Carter is Lecturer in British History at Université Paris Cité and a member of the research lab LARCA, CNRS UMR 8225. She previously worked as a Postdoctoral Research Associate on the project Secondary Education and Social Change in the United Kingdom since 1945, University of Cambridge. Her research focuses on twentieth-century British social and cultural history.

Chris Jeppesen

Chris Jeppesen is a Postdoctoral Research Associate on the project Secondary Education and Social Change in the United Kingdom since 1945, University of Cambridge. His research focuses on twentieth-century British social and cultural history.

Notes

1. All participant names used throughout the article are pseudonyms.

2. SESC also developed samples for NCDS and BCS70 and undertook research on the original questionnaires, which is being used in the project’s wider research. This article focuses only on the NSHD, as explained below.

3. Interview with John Goldthorpe (Citation2013), Paul Thompson, Pioneers of Social Research, 1996–2018, UKDA: https://discover.ukdataservice.ac.uk/QualiBank/Document/?id=q-623c4954-635c-4be4-9f79-ad3ed0925620

4. For a recent rehearsal of these debates see the various contributions to ‘Roundtable: Historians’ uses of archived material from sociological research’, Twentieth Century British History, 33(3), 2022.

5. Northern Ireland was not included by NSHD after the first sweep and, unlike for NCDS and BCS, those who arrived in the UK as children weren’t subsequently included.

6. To find out more about NSHD data sharing go to: skylark.ucl.ac.uk.

7. 1968, age 22, form H3: ‘On the last questionnaire many of you wrote at length about yourselves and your opinions of life in general. We are still most interested to hear what is happening to you, whether this is inside or outside the special topics we have covered in this questionnaire’; 1969, age 23, form H4: ‘On recent questionnaires many of you wrote at length about yourselves and your opinions of life in general. We are still most interested to hear what is happening to you, whether this is inside or outside the special topics we have covered in this questionnaire.’

8. The average length of an answer to the 1968 question by women was 65 words, in 1969 61 words. The average length of an answer to the 1968 question by men was 50 words, in 1969 58 words.

9. Here, as throughout the pen portraits, direct quotations from survey questionnaires/documents are given in quotations marks.

10. Data collection for the 1972 sweep, which involved a detailed at – home interview and a wealth of qualitative answers, was contracted to a research organisation called Social and Community Planning Research. The NSHD team trained the interviewers for three days and provided them in an instruction manual. The interviewers were all female.

11. These were government regional careers officers providing links between young people, schools, and the local labour market.

12. NSHD NF4 (1961), p. 1.

13. NSHD A7 (1961), p. 2.

14. Geographical mobility based on region at age 13 vs. region at age 36, using a scale of 0–4: 0: no move; 1: move to an adjacent region in the same nation; 2: move to another region in the same nation; 3: move to another nation; 4: unknown.