ABSTRACT

A critical analysis of the benefits and challenges of adopting a hybrid approach to conducting qualitative research in schools with children as co-researchers is presented. The study involved 18 children (10–11-years), working as co-researchers in pairs to interview each other with a goal of understanding their experiences online, particularly in terms of digital citizenship and mental wellbeing. Children participated in a pre-research lesson for the acquisition of interviewing skills. Analysis identified three key methodological lessons. First, the co-research approach with foundational learning enabled children to be active and responsible interviewers. Second, the adult researcher and school staff had a role in empowering children through empathy, reassurance, positive praise, and supporting them when upset. The final theme recognised the challenges of research being conducted remotely with implications for future research.

Introduction

Conducting educational research in sensitive topic areas is crucial to advance our understanding of children’s lives. This work is complex, challenging, and tied to researcher perceptions of children and childhood. Educational research has aligned with modern perspectives, seeing children as interdependent co-constructors of their worlds with rights (e.g. James & Prout, Citation2015). To enshrine these values within research, interdisciplinary work using innovative and creative methods are needed, especially for complex questions, a challenge heightened by COVID-19.

The COVID-19 pandemic created research situations whereby adaptation, flexibility, and pragmatic decision-making became necessary. However, as we move towards a post-pandemic society, educational research communities need pedagogical discussions to ascertain which approaches remain useful, and where pre-COVID ways of working are preferable. Our intention here is to stimulate researcher community dialogue to promote sharing and collaboration across the field of education.

Power

Children’s rights frameworks recognise children as competent social beings with agency (Fraser & Robinson, Citation2004) and active involvement in decision-making (Lundy, Citation2007). Embedded within this ideology is the right to participation. Thus, children have the right to participate in areas that impact their lives, including a right to participate in research (Skauge et al., Citation2021). While theoretical tensions exist regarding the concept of participation (Fleming, Citation2013), advocates have fought against the traditional view of children as passive, and promote them as active agents (Thomas, Citation2015). Thus, researchers work to integrate children’s rights and centralise children’s voices to inform policy and practice.

By centralising children’s voices, we see the narrative shift from constructing them as vulnerable with limited competence, to rights-holders with expertise (Tisdall, Citation2017). For researchers this is not straightforward, given the need to navigate competing demands. For example, balancing rights to participation with a right to protection (Caputo, Citation2017). Importantly, ascribing deontological processes does not negate a rights-based approach within research and it is possible to integrate them. Researchers should move away from conceptualisations of vulnerability as naturalised, as this can limit children’s rights to participation (Tisdall, Citation2017). The notion of participation is embedded within the qualitative approach (Pope, Citation2020) and researchers should operate in child-centred ways by using methods focused on children’s experiences and perspectives. This is because child-centred research explores how children experience their lives through connections to their context (Clark, Citation2010) and provide them some control and power (Alderson, Citation2008).

Research in schools

Arguably, one way to balance participation against protectionism, is to conduct child-centred research in environments that already provide safeguarding and where children naturally congregate. It is arguably helpful to utilise environments children are familiar with, comfortable in, and that promote their welfare, like schools (Griffin et al., Citation2014). Conducting research in schools nonetheless brings challenges, as these are educational institutions undertaking the institutional role of teaching and learning. Recruiting children through schools requires knowledge of the school, a communication pathway with appropriate personnel, and a trajectory to benefit. This is essential, as schools face many demands and need a rationale to engage with researchers that aligns with their objectives (Sviydzenka et al., Citation2016).

In undertaking educational research to empower children and working in partnership with schools, the nature of the knowledge production will be of interest in balancing participation and protection. A concern is that this ‘vulnerable’ population may need further safeguards if the project is sensitive, thus adding a layer of complexity (Marsh et al., Citation2017). This may be because of the inherent sensitive qualities of the topic or relating to the practical means of addressing those issues through methods (Mallon et al., Citation2021). To manage this, researchers require techniques that facilitate open discussion, while addressing any discomfort (Batat & Tanner, Citation2021). Schools, therefore, play a role in balancing empowerment and protection as they partner with researchers. Yet, there may be practical barriers that hinder participation, whereby schools reduce children’s participation (Graham et al., Citation2017).

Requiring innovation

In advancing participation debates there is growing interest in using participatory designs that centralise children in the project. The goal has been to provide ways for researchers to engage children, while creating new tools and practices that are impactful and inclusive (Cumbo & Selwyn, Citation2022). Thus, there is agreement that researchers could adopt innovative methodologies and adapt traditional methods when working with ‘vulnerable’ populations (Azzari & Baker, Citation2020).

Such adaptations were profound when researchers found themselves facing the global problem of knowledge production during the pandemic. COVID-19 presented new challenges, but also opportunities, to generate novel insights, discussions, and ideas about how to do research with groups typically constructed as ‘vulnerable’ (Dodds & Hess, Citation2020). Acknowledging opportunities was crucial, as children are more likely to be excluded from research during crisis as perceptions of vulnerability increase (Martin, Citation2010). Yet, evidence shows how well they can contribute views during these times (Hart & Tyrer, Citation2006).

Hearing children’s voices during the pandemic required considerable consideration of how best to reach and include them in research. Schools closed globally to reduce viral spread with many adopting online learning to continue children’s education (Crompton et al., Citation2021). More than 1.5 billion children were impacted by school closures (Thomson, Citation2020). These closures, and other measures, have been subject to criticisms proposing that this adult-centric position has reduced children’s rights to participate in a range of decision-making areas (Goulds, Citation2020). The impact of school closures alongside other COVID-19 restrictions attracted media and policy attention questioning what the potential impact on children would be. Holt and Murray (Citation2022) highlighted that media and policy debates at the time ‘obscured’ the voice of children’s lived experiences. School closures meant that researchers found recruitment and access to participants became more difficult, as health and education were prioritised over knowledge production through research. Nonetheless, researchers adapted their ways of working to enable children the opportunity to engage in research and maintain their partnership working with schools, albeit mostly online.

Online approaches were necessary because of social distancing and public health measures (Dodds & Hess, Citation2020). Although conducting research using the internet can be restricting, as it excludes those with limited digital literacy or access (Lijadi and van Schalkwyk, 2015 Thomas, Citation2015), in the circumstances, researchers had little choice. This meant that education researchers doing research with children, engaging in sensitive topics, had to find ways that managed safeguarding while promoting children’s voices.

In this paper, we report our challenges of working remotely with children as co-researchers to consider where things worked well (or not) when engaging in a sensitive topic. We faced the pre-existing issues of doing research with a ‘vulnerable population’, in a topic whereby issues of confidentiality were paramount due to possible mental health or bullying disclosures, and the likelihood of using certain apps or platforms underage. We discuss our methodological adaptations, particularly where the researcher was online, and children were in the school space with a teaching assistant. To do so, we draw upon empirical data for pedagogical discussion.

Method

Context

There are two primary goals of education: (1) acquisition of knowledge through an official curriculum and (2) to help children to be responsible socially engaged citizens (Biesta, Citation2013). It was this second goal our research project served. We aimed to explore children’s online conduct and moral decision-making as connected to digital empathy, digital responsibility, and digital care (digital ethics of care – see O’Reilly et al., Citation2021). Aligned with this, we explored children’s wellbeing in online spaces.

A co-researcher approach for data-gathering

Pre-COVID-19 there was a growing trend to include children as co-researchers to reduce adult power (Clark, Citation2010). This enables space to enhance children’s participation and respect their rights (Dunn, Citation2015). In a co-research project, children are assigned research roles and conduct research with their peers to generate knowledge (Van Doorn et al., Citation2013). By including children as co-researchers, they develop skills they can translate into their lives and harness a sense of self-efficacy (Cumbo & Selwyn, Citation2022). Our positionality as female researchers from different disciplinary backgrounds, is one of respect for children’s rights and of appreciating the value of children’s voices. This in part drove our commitment to utilising the basic principles of a co-research design.

In reflecting on co-researching with children during COVID-19, Cuevas-Parra (Citation2020) concludes that researchers should think afresh about children’s engagement in crisis contexts. Cuevas-Parra proposes that one way is to create moments when children can explore topics of importance to them, by ‘actively’ participating in research. Cuevas-Parra also describes the importance of being critical about the dichotomies arising when we understand the state of childhood to mean both competence and protection, to think carefully about ethics ensuring that child co-researchers can have some ownership over their research actions and do that safely. This is important as there are challenges in conducting research in schools because of limiting assumptions of adults regarding the capabilities of children (Graham et al., Citation2017).

We therefore adopted the same critical perspective advocated by Cuevas-Parra (Citation2020). When our project was funded, it was designed to take place in the school classroom during one academic year to maintain engagement and include a full co-research approach involving children in all phases. However, as schools were tentatively returning to physical spaces, public health restrictions remained in place. For example, schools introduced ‘bubbles’ whereby pupils and staff were allocated into a bubble and not able to mix with others outside it. This made it difficult for those external to a school to visit, as they were not members of a bubble. The government in England removed the requirement for ‘bubbles’ 21st July 2021 (after our data collection).

In preparation for data collection, we worked closely with our child advisory board and adult professional stakeholder group (teachers, digital experts, academics, health practitioners) to facilitate the project. Furthermore, in consultation we agreed a hybrid approach was appropriate for interviewing. We therefore retained our co-researcher approach for the data gathering phase specifically but not subsequent phases. In collaboration with the school’s deputy head and our researcher (SA) who has a background in education including qualified teacher status, a lesson plan with resources was co-designed. The lesson was devised to build upon and extend children’s knowledge, skills, and understanding of interviewing which had previously been acquired through their English curriculum. The lesson introduced using interviews for knowledge production in research. This was essential, as children required training in the core practical aspects of doing qualitative interviews (Van Doorn et al., Citation2014). As part of this skills development, children were introduced to a semi-structured style to ensure some flexibility in implementing the interview question guide in practice. Children were given freedom to introduce their own questions and re-word those provided. Our intent was to navigate the challenging boundary where training children is framed by researcher and teacher norms but working to support them in skills development rather than manage them in their role (see Kellett, Citation2011).

We worked in partnership with the mainstream primary school to ensure parents and children were provided sufficient information. The school was larger than average and located in a town in the East Midlands. The number of pupils eligible for free school meals was just below national average at the time of data collection. In total, 18 children aged 10–11-years volunteered across two classes. The teachers created dyads from across these two classes. Each dyad had a class member from each class. This was to allow children to interview one another without preconceived ideas which may have been generated from the interview lesson conducted with the whole class. Putting children into pairs can help to reduce adult power (Griffin et al., Citation2014). Child A assumed the interviewer role, with Child B as interviewee, and when completed, they swapped roles. Our hybrid approach had the two children in the classroom with a Teaching Assistant, and our adult researcher (RB) online via the school’s video conferencing platform. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Due to practical constraints of the children transitioning from primary to secondary school and the pragmatic problems created by COVID-19, we were unable to retain the children’s participation as co-researchers beyond data collection.

Analytic approach

Data were subjected to a reflexive thematic analysis due to this being participant-driven and inductive (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019). In the initial phase, two researchers (RB and MO) familiarised themselves with the data and independently generated codes, subsequently meeting to discuss inconsistencies. A mapping exercise ensured agreement as consistent with the quality indicators of the approach (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021). Data saturation was reached. While our original formulation of children as co-researchers would have comprised co-creative work on analysis, the pandemic conditions made this inappropriate; as a result, we drew specifically on our child advisory board to ground truth the findings as a compromise.

We utilised the themes generated from the wider project, consultations with our child advisory board and adult stakeholder group, and dialogue with a professional artist to co-create a digital ethics of care toolkit, including lessons with resources. For this paper, our concern is with the peer-interviewing benefits and challenges, and it is these data we focus on.

Ethics

We acquired approval from the University of Leicester ethics committee. We collected written informed consent from parents, but only included children who actively assented prior to the study starting and again verbally at the beginning of interview. Safeguarding was assured through the presence of the teaching assistant and the research assistant was familiar with the school’s safeguarding policies and the protocols to follow should an issue arise. The school were provided with an encrypted digital recorder and the child interviewers controlled the device. For anonymity, we identify the children as Child1–9, to indicate which number pair, and a/b to indicate whether it was the first or second interviewee in that pair speaking.

Findings

Our intention is to provide a pedagogical journey of the benefits and challenges of using a hybrid approach to co-research with children in schools. We do not report the thematic analysis that yielded findings about children’s online conduct (these are to be reported elsewhere), rather we report the methodological themes to illustrate some of the ways in which this hybrid approach can be successful or limited. Thus, we report three themes: 1) children as active and responsible interviewers, 2) adult interviewer support as beneficial, and 3) challenges of the hybrid approach.

Theme one: children as active and responsible interviewers

Developing skills in communication and interviewing is embedded into the existing curriculum (Department for Education, 2014). Aligning research with existing tasks within schools can facilitate the perceptions of teachers regarding its value. In strengthening our relationship with the teachers, we conducted several consultations to design a lesson plan and resources with appropriate objectives and focus on skills children needed to be interviewers. During the school week, all children in that year group (year 6) were provided with training. Those children participating then conducted interviews in pairs. The children’s enthusiasm for the topic of digital media and emotional wellbeing, their expertise on these matters, and their willingness to share those life experiences meant that they engaged with the activity with a full repertoire of ideas on how to direct the questions. To facilitate this, the adult online researcher at the outset of each paired interview, provided a short reminder of the training and skills.

So, you should have the prompt sheet with you, in front of you, yeah, with the questions. (Pause). And also remembering those skills that you learned on Friday, so making the interviewee feel comfortable, checking you’ve understood what’s being shared, finding out a bit more information.

The adult online researcher was present via a laptop and the children could interact and ask questions. To open each interview set, this researcher reminded the children that this was an opportunity to put into practice those skills acquired in a previous lesson, while also reminding them of basic ethics of the project such as not answering questions they did not want to and that they were there voluntarily. While this provided a prompt for some of the skills for acquiring information from the interviewee, it also reminded the children that they were in control.

A fundamental qualitative interview skill is question design, with open questions generally preferred and some acknowledgement that with children closed questions can facilitate rapport (O’Reilly & Dogra, Citation2016). Operating from a competence paradigm, we recognised that children of this age could differentiate open from closed questions and have some understanding of when to use them. The child interviewers were professional in how they asked questions, using open design, and providing space for the interviewee to reflect and consider their answers.

Interviewer: What do you do when someone is unkind to you online?

Interviewee: I might ignore it or tell someone.

Child 2a&b

Interviewer: What might be unkind, disrespectful behaviours online?

Interviewee: Like people make really mean comments about you, like I don’t like your hair or something.

Child 9a&b

Interviewer: How do you feel when other children are kind or unkind to you online?

Interviewee: It’s … it’s not the best feeling because it just … it’s … I just feel it happens more online because it’s easier to do it behind a phone than in-person, because in-person it’s scarier. So, I just think it’s easier online which is kind of sad, because then it happens most of the time.

Child 7a&b

Wh-questions are usually classified as open questions. Communication research illustrates that wh-questions are those prefaced with a wh-, who, what, where, why, when [and include how] (Koshik, Citation2003). This question design goes beyond an interrogative style of questioning, as it encourages some elaboration and invites alternative responses. The success of the open wh-questions as a tool for encouraging some reflection from the interviewee is illustrated by these examples, especially in pair seven, where the child interviewer asks a ‘how do you feel’ type question prompting the interviewee to provide a protracted answer. Notably, in all examples, the child interviewer opens the conversational floor space, for their interviewee to reflect and consider, and did not interrupt or jump to the next question too quickly.

The demonstration of active listening was clear, as children used their interviewing skills to demonstrate that they were attending to the answers. One useful way of demonstrating active listening and putting the question into the interviewee’s domain of knowledge, is through a ‘you said x’ prefaced question (Kiyimba & O’Reilly, Citation2018). While ‘you said x’ formulations illustrate attending to prior talk is arguably a sophisticated technique for encouraging elaboration, the child interviewers nonetheless did utilise this skill (which was not on the interview guide).

When you said keeping people in groups, do you think that keeping certain people in different friendship groups that like click and really go well together is a good idea? Or do you think everybody should be able to like mix and stuff? Child 3b

You said lessons, what might these lessons look like? Child 7a

These two child interviewers utilised different kinds of question design, with Child 3b using a closed question, opened with an ‘either/or’ interpretation and Child 7a utilising a simple and open wh- question. However, commonly, the ‘you said x’ preface to this information elicitation, served two important functions. First, this preface illustrated to the interviewee that they were listening, as they recalled specific aspects of the interviewee’s earlier disclosures. Second, this preface positions the content of the question in the interviewee’s domain of knowledge and provides a platform for elaboration on that earlier disclosure. This skill encouraged interviewees to discuss their personal experiences on a topic that was delicate. This was also accomplished through positive reinforcement via praise, as they prompted their participants to continue with verbal indicators of support.

Interviewee: If you had like the school computers or iPads, I would let the kids all go on an online server on the game …

Interviewer: That’s good.

Child 6a&b

Yes yeah, very good point. And how do you feel when other children or your friends are kind or unkind to you online? Child 3b

Positive words of encouragement in the form of praise can be a useful way of demonstrating alignment with the interviewee, and here the children provided such support for their peers to illustrate treating the response as valuable. By offering positive assessments of the responses arguably helps to generate a rapport, which creates further space for elaboration of answers.

This need for elaboration was recognised by the child interviewers, as they adopted further useful interviewing skills to ensure that their interviewee remained engaged and on topic.

Interviewee: Well, it depends, sometimes they can be mean or sometimes they can be kind and respectful.

Interviewer: Yes. Okay, um, can you expand on that?

Interviewee: Well, um, sometimes you can help maybe be kind by, um, giving comments that are nice or you cannot be nice by giving bad comments

Child 4a&b

As guided in their interview training (with some example prompts on their interview guide), they used prompts and did not close areas of conversation started by the interviewee too quickly. They utilised phrases asking interviewees to expand on that, to give examples, or say more. In those cases where the interviewer prompted for further information, the interviewees did indeed provide more detail.

There were occasions where interviewees struggled to articulate an answer to a question. This is arguably unsurprising given their young age as well as the complexity of the topic and some of the questions. However, what was sophisticated, was that the interviewers often recognised that the question remained unconsidered by choosing to return to the difficult question, usually rewording it slightly.

Let’s go back to the question before that you couldn’t answer. How could schools help children have a respectful and health relationship online? Child 5a

Aligned with this reflective questioning style, interviewers recognised there was the potential for misinterpretation in their dyadic communication. They noted that in processing the answers from the interviewee, they were an active agent in the interview construction. A frequently employed technique, then, was to seek clarification. This served the dual purpose of displaying that the responses provided were being heard (active listening), and of checking the accuracy of the hearing while moving outside of the interview guide. While this is an excellent reflective technique, the interrogative tag questions do close down the interviewee’s responses rather than open space for elaboration.

Interviewer: So, according to your voice, you said that like you can tell when people are upset, um, that like they start typing less and less, is that correct?

Interviewee: yeah, that’s correct

Child 6a&b

Interviewer: Yeah, okay, so I heard you say that when you’re, if you’re on an online game and you’re feeling upset you would leave the call and also tell a trusted adult. Is this correct?

Interviewee: yeah

Child 6a&b

In some cases, rather than providing a formulation of the interviewee’s response and checking it, they instead queried what the interviewee meant by seeking a more meaningful clarification.

Interviewee: Like, attacking someone. Lowering someone’s self-esteem and things like that.

Interviewer: What do you mean by attacking?

Interviewee: Um, saying crude comments and just nasty things online.

Child 7a&b

By clarifying an interpretation and by questioning the meaning of a response, the interviewers could ascertain a degree of certainty about the interviewee’s answers to the question.

Theme two: adult support as beneficial

The co-researcher approach assigned roles to children and empowered them in the knowledge production process. They had control over the recording device, the delivery of the interview schedule, and engagement of the interviewee. However, they only received one training session on interviewing skills, were novice researchers, and were children to whom we were responsible for ensuring protection. Thus, the hybrid presence of an adult researcher was pragmatically necessary. This left us with dilemmas of managing power dynamics, working to ensure the adults (teaching assistant and researcher) did not inadvertently control the research process.

One way to maintain the role of the child researchers was to afford them opportunities and choices. As adults, we did not predetermine which child took the role of interviewer first and neither did we control how long the interview lasted. Instead, the online adult researcher provided choice to reduce power, facilitated as her presence was mediated by the screen.

Adult online researcher: Thank you. And so, who would like to be the interviewer first?

Child: Me

Child1a

Adult online researcher: perfect, so who would like to be doing the interview first?

Child: Me.

Child5b

The adult online researcher also offered other choices to ensure children remained in control of the interview such as whether they wanted a break once the first interviewer had completed their set of questions. Thus, the adult online researcher checked there was agreement between the child pair, and both were comfortable to continue.

Adult online researcher: So, would you like a break between the two interviews or are you …

ChildB: No, I’m fine, I’d rather just do it. Just do it now.

ChildA: Yeah.

Child 4a&b

In this example, the adult online researcher utilised their emotional intelligence, particularly empathy by acknowledging the potential physical and emotional impacts of being an interviewer or interviewee. By providing children options this allowed them to feel in control. Furthermore, children’s participation was openly valued and acknowledged through positive feedback.

Congruent with this need for positive reinforcement and valuing of the children’s contributions, the adult online researcher, and the teaching assistant in the room (not shown here), did provide encouragement and praise. There were many ways in which this was accomplished, but mostly with extreme case formulations (Pomerantz, Citation1986), to add emphasis.

Adult online researcher: … and that’s another brilliant interview.Toward Child 3b

Adult online researcher: Yeah, great, and yes, it’s perfectly okay to say exactly what you’re feeling and thinking. Toward Child 6a&b

The adults engaging with the child dyads played an important role in encouraging and facilitating the flow of the interviews. The children were using newly acquired interviewing skills and the use of extreme case formulations with emphasis through praise was a mechanism to consolidate and promote additional learning. The children were participating in a research project, but it was also an opportunity for personal benefit through education. Using terms like ‘brilliant’ functioned to encourage the children to continue, but also highlighted their learning which was consistent with the educational environment where children are praised and encouraged in their acquisition of knowledge and skills.

Facilitating the process of the interviews also meant that the adult parties had a researcher role to ensure that the full spread of child expertise and knowledge was realised in practice. While the children did an excellent job of interviewing their peer, there were areas of the research agenda that required further elaboration and the adults were able to pursue this in situ, as they were privileged hearing parties to the original answers provided. However, this required some delicate management to ensure it was perceived as building upon those earlier responses and was accomplished in a way that did not undermine the child interviewers, but rather complemented them.

Adult online researcher: Excellent, and again I’ll ask a couple more questions, just things that came up as you were talking, that was really great. Toward Child 4a&b

Adult online researcher: Thank you, those are amazing answers as well. I’d just like to pick up because you said, you’ve mentioned a few times that you’ve seen kind of your friends experience unkind things being sad. Are you able to give any examples of what that looked like and what happened? Toward Child7a

To manage this delicacy, the adult online researcher typically utilised praise to illustrate that the responses were valued. This was coupled with signposting so that the expectations of the children were effectively managed, and encouraged elaboration of previously raised issues, which also showed attention to the proceedings.

Theme three: challenges of the hybrid approach

The adult parties were ready to intervene when things became more challenging. As the adult online researcher was not school personnel and due to restrictions imposed by the pandemic, she was not present physically. This created challenges and our hybrid approach was adopted. Children of this young age do require protection, and strategies were necessary to manage any upset or safeguarding. Having a familiar adult present, like the teaching assistant, can be a reassuring presence as children try out their new skills, and this responsible adult is available to notice non-verbal cues that the adult online researcher may not detect. A good example of this was those occasions where the children sometimes struggled to articulate an answer to a question and they started to become upset or frustrated, but this was sometimes subtle. In those instances, the adult in the room is cued to those nuanced changes in body language and could step in and provide encouragement and reassurance.

Due to the sensitive nature of the topic and potential unanticipated disclosures in relation to digital media, emotional wellbeing, and mental health, it was important to have a present adult in the room in case of distress. The adult online researcher was nonetheless proactive in checking the emotional states of the children.

Adult online researcher: And are you both kind of feeling okay? I know talking about these things, particularly the unkind behaviours can be upsetting sometimes. So, are you both feeling okay?

Child7a: Yeah.

Adult online researcher: And obviously if that changes, if you kind of think about anything we’ve discussed and you start feeling upset or maybe angry later on just, yeah, just talk to a teacher. ‘Cause I don’t want you to be carrying those feelings throughout the day.

Child7a: Yeah.

Child7b: Uh huh.

Child 7 a&b

The adult online researcher conveyed to the children that it was recognisably a topic that might cause upset, particularly where the children had experienced unkind comments, bullying, or other potentially harmful online issues. There were rare occasions where the children became upset, and this was managed by the adults.

Adult online researcher: Okay, we don’t have to talk about this if it’s upsetting.

Child: [Crying]

Teaching assistant started to sooth the child and speak to her.

Adult online researcher: Would you like to take a break, [name]?

Teaching assistant took the child out of the room. Child2a

In relaying an upsetting example of cyberbullying (dealt with by the child’s parents with the school), the child became upset. Shortly into her story, the online researcher noticed a change in the child’s tone and facial expression saw that she appeared visibly uncomfortable. As pre-arranged, the teaching assistant was active in soothing the child. At this point the adult online researcher stepped in and suggested a break, and the teaching assistant took the child out of the room. To mitigate the potential impact of listening to a peer becoming upset and ensure the needs of both children were attended to, the adult online researcher also checked in with the partner that they were okay. This effectively managed the upset as the child returned very shortly afterward and both children were happy to continue. While the online adult researcher had no opportunities to follow up and could only point out to the children to seek support, having a teaching assistant present in the room did mean there was an adult who could check-in later. In consultation with school personnel, the children did return to classroom activities and found the experience positive.

These kinds of examples illustrate why it was important for us to have an adult in the interviewing space with the children as they conducted their role as interviewers. However, the presence of a familiar adult in the classroom environment did provide a disadvantage that may have been overcome if the adult online researcher could have been in the school building instead. That is, it is possible that children did censor some responses because of the presence of an educator (which may occur also with the presence of a researcher). For example, it is known that children of this age group use a range of digital media, and our participants also disclosed this, but it is also known that many in this age group are using media that has an age restriction older than their years. However, while there were occasions where they hinted at this, at times they were reticent to talk about those issues in the presence of the teaching assistant, despite the encouragement to be open.

Child: I don’t use social media really.

Teaching assistant tried to reassure the child they would not get into trouble for disclosing. Child 2b

Child: Some people, they do have, like WhatsApp which is like, um, like over their age group but their parents will check it. Child 3a

Whilst steps were taken to support children in understanding they were participating in research and with this came a level of confidentiality, having a teaching assistant in the room may be confusing particularly when known to the children and in normal day-to-day exchanges the boundaries are different.

Discussion

Our intention with this paper is to promote qualitative community dialogue regarding the extent to which it may be helpful to maintain some of the methodological adaptations that were necessary during the pandemic. We have reflected on our co-researcher approach that was necessarily hybrid because of public health measures in place. The aim of our project was to explore the experiences of children of their digital media use and ascertain their beliefs of how that influenced their mental health and wellbeing, while considering the impact of their online conduct and moral decision-making. Thus, there was recognition of the balance between their participation and protection, the construction of competency and vulnerability, and the affordance of rights and power, while meeting the goals of the research agenda. In this pedagogical narrative, we attended to our child-centred, co-researcher approach to data collection and the adaptations we made to achieve that.

To maintain a child-centred approach that respected children’s rights to participation, we provided children the opportunity to build an additional identity as a qualitative interviewer and implement their skills in practice. Through our hybrid approach, we maintained flexible, active engagement of the children and found ways to make the process enjoyable (Flewitt et al., Citation2018). Using this co-research participatory technique functioned to dilute the hierarchies of adult/child power differences and gave voice to children (Haffejee et al., Citation2022). Throughout the process, the power and control shifted dynamically between the children, the classroom-based teaching assistant, and the researcher online.

While we did not want to construct the children as vulnerable, we did acknowledge that vulnerability is neither static nor absolute, as it is contextual and fluid (Nordentoft & Kappel, Citation2011), and moments of vulnerability within the interviews required an adult-led intervention to manage upset. Importantly, there was anticipation and arguably expectation from the children themselves that the adult parties would step in and manage such situations. It was necessary to account for the heterogeneity in the population, but also in their experiences and resilience to relay narratives about any difficult or negative events they had encountered.

As is often the case with co-researched or participatory projects and as encouraged by Cuevas-Parra (Citation2020), we reflected on the questions of ‘who is speaking’ and ‘who is being heard’ at the project conception, delivery, and analysis stages. During the project conception and delivery, the involvement of the school particularly a senior leader and teachers was important. In co-designing a lesson to teach interview skills the school’s input allowed the content to be pitched appropriately to enable prior knowledge, skills and understanding to be built upon whilst also providing children the opportunity to acquire additional skills. For example, how to probe and seek clarity in an interview alongside strategies for making the interviewee comfortable. By having teachers deliver these lessons, children acquire new learning through a trusted adult with the aim to maximise their opportunity to practise and take risks in developing new skills.

The hybrid nature of the data gathering appeared to offer a surprising benefit; having no unknown researcher in the physical room meant the children were more able to find their own style of expression, albeit using the techniques and some linguistic framings they had been taught. Their voices became more centred and their flow more established without interruption from adults. There were, of course, instances where the adult in the room intervened – whether because they knew of additional needs that needed scaffolding or because of their own discomfort with silence – but there was rapid and easy establishment of a conversational flow with the children’s voices – as interviewer or interviewee – that contributed heavily to ensuring that it was they who were both speaking and being heard.

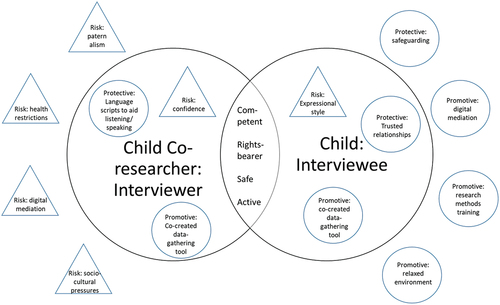

This conversational flow and easy expressional style invited some reflection from the research team as to the ways researchers can actively do their part to create spaces of communication for co-research with children after crisis experiences such as lockdowns. In those reflections, we realised that there were external and internal risk factors as well as protective and promotive factors, that needed to be fostered to enable children to build an identity for themselves as a researcher. We share the examples of these observed for working with children as co-researchers to gather data in . Future research could explore whether these factors are applicable i) to the other conventional stages of the research cycle and ii) in non-crisis contexts.

is not, of course, an exhaustive list of the risk, promotive, and protective factors for child-researcher identity-building, but rather those we observed in this project specifically. What can be seen is the co-creational nature of the roles of interviewer and interviewee, intersected by the values underpinning the project (and wider evidence base) of children as i) competent, ii) bearers of rights, iii) people balancing the right to explore, challenge and take risks as well as remain safe and well, and iv) people able to take action to provide insights into their own lives.

In the role of child interviewer, we observed the risk of confidence (or its absence) as having the potential to impact on the creation of the appropriate sorts of communicative space. This was counterbalanced by a protective factor in the form of the provision of language scripts in the lesson to aid listening and speaking skills, and a promotive factor in the form of the interview schedule. We also interpreted the interview schedule to be a promotive factor for the child-as-interviewee, alongside a protective factor in the form of a trusted relationship with both the other child in the dyad and the adult in the room. The main risk to the interviewee in our communicative space was to their expressional style, which would enable them to share their perspectives verbally. This was a small-scale exploratory study, but this interpretation suggests that using some alternative, non-verbal, form of data gathering such as creative work might mitigate against the risk of the interviewee being unable to truly manifest their voice in the research. Future larger-scale research could explore this further.

External to the dyads themselves, there were risk, promotive, and protective factors in the wider environment that offered crucial context to the conversations being had. Some of the risk factors have been observed in other studies such as the risk of paternalism (Willumsen et al., Citation2014). Others – health restrictions – were temporary in nature and associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, while the last relating to socio-cultural pressures and expectations were mitigated by the supervised dyadic nature of the interviews. These were not ‘hot seat’ activities in which the children were expected to ‘perform’ for an audience. The interview training, they received in a relaxed, trusted environment afforded by the practitioners were important to promoting the communicative space where children could build a researcher-identity, while thoughtful safeguarding approaches and (as much as possible) unobtrusive use of the technology acted as protective factors in the space.

Our intention with this article was to further stimulate discussions within the pedagogical and research communities about ways of facilitating children’s rights to be interpreters of, and agents in, their own lives. While there are undoubtedly limitations to the study, not least the small-scale exploratory nature of the activity, constraining our opportunities to pursue involvement of children at all points in the project, and the limited nature of the sample, our conceptualisation of the risk, promotive, and protective factors in creating communicative spaces with children provides a starting point for those doing this work in the aftermath of crises.

Acknowledgment

We thank the children and teachers who made this research possible and the ESRC e-Nurture network for the funds – G107030 PA-R2

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Michelle O’Reilly

Michelle O’Reilly is an Associate Professor of Communication in Mental Health and Chartered Psychologist in Health for the University of Leicester. She is also a Research Consultant and Quality Improvement Advisor for Leicestershire Partnership NHS Trust.

Sarah Adams

Sarah Adams is a Lecturer in Education Studies (Primary) for the Faculty of Wellbeing, Education & Language Studies at the Open University.

Rachel Batchelor

Rachel Batchelor is a Doctoral Student for Clinical Psychology at the University of Oxford.

Diane Levine

Diane Levine is a Lecturer in Criminology for the University of Leicester.

References

- Alderson, P. (2008). Children’s participation rights: Young children’s rights: Exploring beliefs, principles and practice (second ed.). Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Azzari, C., & Baker, S. (2020). Consumer vulnerability: Foundations, phenomena, and future investigations. Consumer Vulnerability, Routledge.

- Batat, W., & Tanner, J. F. (2021). Unveiling (in) vulnerability in an adolescent’s consumption subculture: A framework to understand adolescents’ experienced (in) vulnerability and ethical implications. Journal of Business Ethics, 169(4), 713–730. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04309-2

- Biesta, G. (2013). The beautiful risk of education. Paradigm Publishers.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise & Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 328–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

- Caputo, V. (2017). Children’s participation and protection in a globalised world: Reimagining ‘too young to wed’ through a cultural politics of childhood. The International Journal of Human Rights, 21(1), 76–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642987.2016.1248124

- Clark, C. (2010). In a younger voice: Doing child-centred qualitative research. Oxford University Press.

- Crompton, H., Burke, D., Jordan, K., & Wilson, S. (2021). Learning with technology during emergencies: A systematic review of K‐12 education. British Journal of Educational Technology. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13114

- Cuevas-Parra, P. (2020). Co-researching with children in the time of COVID-19: Shifting the narrative on methodologies to generate knowledge. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 1609406920982135. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406920982135

- Cumbo, B., & Selwyn, N. (2022). Using participatory design approaches in educational research. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 45(1), 60–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743727X.2021.1902981

- Dodds, S., & Hess, A. (2020). Adapting research methodology during COVID-19: Lessons for transformative service research. Journal of Service Management, 32(2), 203–217. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-05-2020-0153

- Dunn, J. (2015). Insiders’ perspectives: A children’s rights approach to involving children in advising on adult-initiated research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 18(1), 91–104.

- Fleming, J. (2013). Young people’s participation – where next? Children and Society, 27, 484–495. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1099-0860.2012.00442.x

- Flewitt, R., Jones, P., Potter, J., Domingo, M., Collins, P., Munday, E., & Stenning, K. (2018). I enjoyed it because … you could do whatever you wanted and be creative’: Three principles for participatory research and pedagogy. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 41(4), 372–386. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743727X.2017.1405928

- Fraser, S., & Robinson, C. (2004). Paradigms and philosophies. In S. Fraser, V. Lewis, S. Ding, M. Kellett, & C. Robinson (Eds.), Doing research with children and young people (pp. pp; 59–78). Sage.

- Goulds, S. (2020). Living under lockdown: Girls and COVID-19. PLAN International.

- Graham, A., Simmons C., & Truscott, J. (2017). ‘I’m more confident Now, I was really quiet’: Exploring the potential benefits of child-led research. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 30(2), 190–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2016.1242803

- Griffin, K., Lahman, M., & Opitz, M. (2014). Shoulder-to-shoulder research with children: Methodological and ethical considerations. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 14(1), 18–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718X14523747

- Haffejee, S., Theron, L., Hassan, S., & Vostanis , P. (2022). Juxtaposing disadvantaged children’s insights on psychosocial help-seeking with those of service providers: Lessons from South Africa and Pakistan. Child & Youth Services. https://doi.org/10.1080/0145935X.2022.2101445

- Hart, J., & Tyrer, B. (2006). Research with children living in situations of armed conflict: Concepts, ethics and methods. (Working paper No.30). Refugee Studies Centre.

- Holt, L., & Murray, L. (2022). Children and Covid 19 in the UK. Children’s Geographies, 20(4), 487–494. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2021.1921699

- James, A., & Prout, A. (2015). Introduction. In A James and A Prout (Eds)., Constructing and reconstructing childhood: Contemporary issues in the sociological study of childhood; classic edition (pp. 1–5). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315745008

- Kellett, M. (2011). Empowering children and young people as researchers: Overcoming barriers and building capacity. Child Indicators Research, 4(2), 205–219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-010-9103-1

- Kiyimba, N., & O’Reilly, M. (2018). Reflecting on what ‘you said’ as a way of reintroducing difficult topics in child mental health assessments. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 23(3), 148–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12215

- Koshik, I. (2003). WH-questions used as challenges. Discourse Studies, 5(1), 51–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614456030050010301

- Lundy, L. (2007). ‘Voice’ is not enough: Conceptualising article 12 of the United Nations convention on the rights of the child. British Educational Research Journal, 33(6), 927–942. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920701657033

- Mallon, S., Borgstrom, E., & Murphy, S. (2021). Unpacking sensitive research: A stimulating exploration of an established concept. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 24(5), 517–521. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2020.1857965

- Marsh, C., Browne, J., Taylor, J., & Davis, D. (2017). A researcher’s journey: Exploring a sensitive topic with vulnerable women. Women & Birth, 30(1), 63–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2016.07.003

- Martin, M.-L. (2010). Child participation in disaster risk reduction: The case of flood-affected children in Bangladesh. Third World Quarterly, 31(8), 1357–1375. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2010.541086

- Nordentoft, H., & Kappel, N. (2011). Vulnerable participants in health research: Methodological and ethical challenges. Journal of Social Work Practice, 25(3), 365–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650533.2011.597188

- O’Reilly, M., & Dogra, N. (2016). Interviewing children and young people for research. Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526419439

- O’Reilly, M., Levine, D., & Law, E. (2021). Digital ethics of care philosophy to understand adolescents’ sense of responsibility on social media. Pastoral Care in Education, 39(2), 91–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643944.2020.1774635

- Pomerantz, A. (1986). Extreme case formulations: A way of legitimising claims. Human studies, 9, 219–229.

- Pope, E. (2020). From participants to co-researchers: Methodological alterations to a qualitative case study. The Qualitative Report, 25(10), 3749–3761. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2020.4394

- Skauge, B., Storhaug, A., & Marthinsen, E. (2021). The what, why and how of child participation—A review of the conceptualization of “child participation” in child welfare. Social Sciences, 10(2), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10020054

- Sviydzenka, N., Aitken, J., & Dogra, N. (2016). Research and partnerships with schools. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 51(8), 1203–1209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1224-5

- Thomas, N. (2015). Children and young people’s participation in research. In T. Gal & B. F. Duramy (Eds.), International perspectives and empirical findings on child participation: From social exclusion to child-inclusive policies (pp. pp: 89–110). Oxford University press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199366989.003.0005

- Thomson, G. (2020). Futures of 370 million children in jeopardy as school closures deprive them of school meals – UNICEF and WFP. UNICEF.

- Tisdall, K. (2017). Conceptualising children and young people’s participation: Examining vulnerability, social accountability and co-production. The International Journal of Human Rights, 21(1), 59–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642987.2016.1248125

- Van Doorn, F., Gielen, M., & Stappers, P. (2014, June). Children as co-researchers: More than just a role-play. IDC '14: Proceedings of the 2014 conference on Interaction design and children, 237–240. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/2593968.2610461

- Van Doorn, F., Stappers, P., & Gielen, M. (2013, April). Design research by proxy: Using children as researchers to conduct contextual design research. CHI '13: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2883–2892. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/2470654.2481399

- Willumsen, E., Hugaas, J., & Studsrød, I. (2014). The child as co-researcher—moral and epistemological issues in childhood research. Ethics and Social Welfare, 8(4), 332–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/17496535.2014.894108