Abstract

Introduction: This study evaluated the accuracy of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) for preoperative staging of rectal cancer and guiding the treatment of transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) in early rectal cancer.

Material and methods: One-hundred-twenty-six patients with rectal cancer were staged preoperatively using EUS and the results were compared with postoperative histopathology results. Radical surgeries, including low anterior resection (LAR), abdominal-perineal resection (APR) and Hartmann surgeries, were performed on patients with advanced rectal cancers, and TEM was performed on patients with stage T1. The Kappa statistic was used to determine agreement between EUS-based staging and pathology staging.

Results: The overall accuracies of EUS for T and N stage were 90.8% (Kappa = 0.709) and 76.7% (Kappa = 0.419), respectively. The accuracies of EUS for uT1, uT2, uT3, and uT4 stages were 96.8%, 92.1%, 84.1%, and 88.9%, respectively, and for uN0, uN1, and uN2 stages, they were 71.9%, 64.9%, and 93.0%, respectively. Twelve patients underwent TEM and received confirmed pathology results of early rectal cancer. After postoperative follow-up, there were no local recurrences or distant metastases.

Conclusion: EUS is a good and comparable technique for postoperative staging of rectal cancer. Moreover, EUS is used as indicator for preoperative staging and tumor assessment strategy when considering TEM.

Introduction

Significant advancements in endoscopic techniques have added to our understanding of the causes of local-regional recurrence of rectal cancer, with refinements in surgical techniques and new imaging modalities having greatly improved our selection of treatments and surgical planning [Citation1]. The depth of tumor infiltration of the rectal wall and the involvement of the regional lymph nodes are the major factors in determining prognosis [Citation2]. Correct staging of a tumor is very important for patient care, providing a good indication of survival and allowing for optimal patient treatment. Assessments of the depth of cancer invasion (T-stage) and the presence of lymph node involvement (N-stage) are fundamental components of cancer staging. As a complementary technique to other cross-sectional imaging methods, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) represents one of the most significant developments in endoscopy, with its main application being the staging of rectal cancer [Citation3]. EUS is useful for evaluating local tumor invasion and lymph node metastasis and, thereby, establishing the stage of the primary tumor prior to surgery for individualized treatment [Citation4].

Transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) has been an important development in the treatment of rectal disease in recent years. TEM is a technical procedure that provides excellent magnification and working area within the rectal lumen, allowing the surgeon to perform full-thickness excision of large sessile rectal polyps or early rectal cancer in stages Tis and T1 [Citation5]. Moreover, the TEM procedure provides accurate assurance of the resection margins and the possibility of suturing [Citation6].

The aim of our study was to evaluate the role of EUS in the staging of rectal cancer and to analyze both the accuracy and limitations of this imaging method. We compared the preoperative images of patients and performed TEM with the corresponding postoperative pathological results to choose reasonable surgical procedures and to evaluate the clinical prognosis.

Material and methods

Clinical data

A total of 126 patients with rectal cancer were recruited into this study between June 2012 and December 2015. They had received EUS for preoperative staging of rectal cancer at the general surgery department of the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University. The group included 76 male and 50 female patients, 27 ∼ 82 years of age, with histologically proven rectal cancer through enteroscopy. In our study, 22 patients had undergone preoperative neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy; however, 17 patients refused preoperative neoadjuvant treatment, opting for immediate surgery. Low anterior resection (LAR) was performed in 72 patients, abdominal-perineal resection (APR) in 36 patients, Hartmann surgery in six patients, and TEM in 12 patients. After EUS examination, all patients underwent surgical treatment of the tumor and received diagnostic results of the histopathology examination. All patients provided written informed consent for input of their data into our database and use of their data for research purposes. The demographic and clinical characteristics of all surgical groups are summarized in .

Table 1. Clinical and demographic patient characteristics.

Examination and evaluation methods

Ultrasonic endoscope equipment

All preoperative assessments were performed using an Olympus ultrasonic endoscope (UM-200 type, Olympia, Tokyo, Japan), with a frequency of 715 MHz to 12 MHz, with the miniature probe (UM-2R) using a frequency of 12 MHz.

Evaluation criteria

The staging criteria of Hildebrandt et al. [Citation7] were used as the ultrasonic staging (uT staging) for the depth of infiltration of the rectal cancer, with the stages defined as follows:

stage uT1, the tumor is localized in the mucosa or submucosa, with a strong echo zone through the complete second layer;

stage uT2, the tumor has infiltrated the muscularis propria, but is localized in the rectal wall, with a strong echo zone of the second layer, with some destruction visible, and with thickened low echoes in the muscle layer, while a strong echo zone is visible through the complete third layer;

stage uT3, full-thickness tumor involvement, with infiltration of the fibrous and adipose tissue around the rectum, with visible destruction within the strong echo zone of the third layer and irregular low echo jagged protrusions which are suggestive of tumor involvement of tissue outside of the intestinal wall;

stage uT4, tumor involvement of adjacent organs or tissues (prostate or vagina, etc.), with loss of the strong echo zone of the normal margins around organs and, therefore, a loss of boundary between an organ and the low echo zone tumor.

Metastases of lymph nodes appear as low-echo structures near the blood vessels of the mesorectum and tissues around the tumor, having clear boundaries and lower echoes compared to the echo strength of the surrounding tissue. Absence of such low-echo structures and a maximum lymph node diameter of <5 mm were considered to indicate negative lymph node metastasis (uN0), with the presence of low echo structures and a maximum lymph node diameter ≥5 mm as indicative of lymph node metastasis (uNx), with the following stages of metastasis defined: stage uN0, no local lymph node metastasis; stage uN1, involvement of one to three lymph nodes; and stage uN2, involvement of >4 lymph nodes.

TEM therapy

Surgical methods

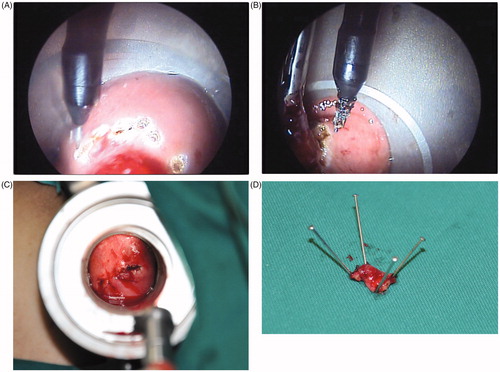

The TEM was performed by “mark”, “resection” and “suture” ().

Figure 1. The surgical procedures of TEM (A) Mark (The boundary line of the resection was burned with an ultrasound knife.) (B) Resection (Resect the intestinal wall full-thickness and ensure the integrity of specimen with 1 cm of the incisal margin.) (C) Suture (Continuous or interrupted full-thickness suture was carried out with 3–0 absorbable sutures.) (D) Specimen (The resected sample was submitted for pathological examination after the fixation of the margin with a pin.).

Postsurgical follow-up

Patients were followed up every three months for the first year postsurgery, every six months for the next three years and annually thereafter. The follow-up examinations included colonoscopy, physical examination and assay of serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA); EUS or pelvic computed tomography (CT) examination was performed if necessary.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed with SPSS version 20.0 statistical software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous variables are expressed as the mean ± standard deviations. The accuracy, sensitivity and specificity of EUS for preoperative TNM staging were evaluated against the pathological report, which was considered the gold standard. The Kappa statistic was used to determine consistency between the EUS-based staging and pathology staging, with a Kappa >0.75 indicating favorable consistency (the maximum of Kappa being 1) and a Kappa <0.4 indicating unfavorable consistency.

Results

Accuracy of EUS on the evaluation of T staging for rectal cancer

The agreement between the EUS-based and pathological staging was 90.8%, with a favorable overall Kappa = 0.709, with agreement of the four tumor stages as follows: 96.8% for T1; 92.1% for T2; 84.1% for T3; and 88.9% for T4. For the 24 cases of non-agreement, EUS staging underestimated the tumor stage in 15 cases and underestimated the stage in nine cases ().

Table 2. Comparison on the consistency of preoperative T staging and postoperative pathological T staging for rectal cancer by EUS evaluation.

Accuracy of EUS on lymph node staging for rectal cancer

The overall accuracy rate was 76.7% for the evaluation of presurgical N staging (uN) by EUS, which was deemed to be unfavorable (Kappa = 0.419), with the accuracy rate for the three stages of lymph node involvement as follows: 71.9% for uN0; 64.9% for uN1; and 93.0% for uN2. The EUS-based staging underestimated the stage of lymph node involvement in 13 cases and overestimated the stage in 27 cases ()

Table 3. Comparison on consistency of preoperative N staging and postoperative pathological N staging for rectal cancer by EUS evaluation.

Surgery

TEM was performed in 12 of the 126 patients, who were classified as stage Tis or T1N0M0 by preoperative EUS staging. The tumors were located within 12 cm of the anal verge, and the TEM procedures were a mean operative time of 92 min (range, 6 5 ∼ 123 min). The pathological T stages of the cases treated using TEM included seven Tis and five T1 cases. The mean distance from the anal verge was 5.2 cm (range, 3–10 cm), and the mean tumor size was 2.1 cm (diameter range, 0.5–6 cm). Tumors were distributed along the rectal wall, with 50.0% (n = 6) anterior, 16.7% (n = 2) lateral and 33.3% (n = 4) posterior. No severe complications were observed during or after surgery, and patients were discharged within two to three days after surgery. The mean hospital stay was 6.1 (range, 4 ∼ 10) days. Wound healing was favorable in all cases, and the enteroscopy was performed one month after surgery. The median follow-up period was 21.6 (range, 1 1 ∼ 31) months, and no local recurrence and distant metastases were observed.

Surgical procedures were performed in the other 114 patients, including 72 cases of LAR, 36 cases of APR and six cases of Hartmann procedure; no severe complications were observed during or after surgery. The patients were discharged seven to ten days after surgery once the anal aerofluxus had recovered and the patient was able to take food. The median postoperative follow-up period was 17.3 (range, 5 ∼ 33) months. Recurrence was noted in two male patients who had undergone an open Hartmann procedure. A rise in serological tumor markers was identified in three male patients treated with LAR but with no evidence of recurrence on enteroscopy and CT examination. No obvious local recurrence and distant metastases were identified in other patients.

Discussion

Accurate EUS staging of rectal cancer is crucial to guide the therapeutic strategy, namely, the selection of immediate surgical treatment or preoperative neoadjuvant therapy, to reduce local recurrence rates, to improve indications for sphincter-preserving surgeries, and, possibly, to improve the overall prognosis of patients[Citation8]. Previous reports that have compared the accuracy of EUS to other image-based examinations for rectal cancer staging have demonstrated the superiority of EUS over CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [Citation9].

In addition, EUS can be provided to a patient at a lower cost than CT or MRI and avoids the need to consider contrast medium sensitivity for CT and the presence of metal implants for MRI. Moreover, EUS is an easy and feasible technique for hospitals to develop, without requiring a large financial investment and can be situated only in the department of gastroenterology,thus not requiring additional space.

Nevertheless, there are some disadvantages of EUS compared to CT and MRI for T and N staging of rectal carcinoma. The quality of EUS is highly dependent on the skill of the operator and therefore requires sufficient skill to be developed to ensure accurate staging [Citation10]. In addition, EUS has poor patient acceptability and limited depth of penetration. Moreover, the assessment of the mesorectal fascia is also hampered by the limited field of view of EUS [Citation11]. In addition, EUS cannot be reliably used to assess posttherapy responses, as it cannot reliably differentiate between postradiation edema, inflammation, fibrosis and viable tumors [Citation12]. Among these factors, operator dependency is a major factor in obtaining accurate results, with a learning curve being necessary to achieve sufficient proficiency for orientation, identification and interpretation of images, with precise probe positioning by an experienced operator being most likely to yield accurate results.

The new modalities of transrectal ultrasonography (TRUS) and three-dimensional (3-D) TRUS have been widely accepted for evaluating rectal cancer [Citation13] and can provide better visual images of the tumor volume and spatial relationships to the adjacent organs and structures. Kim MJ [Citation14] reported that TRUS has 69–94% accuracy for the T staging of rectal cancer, and the sensitivity and specificity of TRUS for the T staging of rectal cancers were as follows: T1, 87.8% and 98.3%; T2, 80.5% and 95.6%; T3, 96.4% and 90.6%; and T4, 95.4% and 98.3%, respectively. In addition, the overall sensitivity and sensitivity of TRUS in the diagnosis of lymph node involvement were 73.2% and 75.8%, respectively. Both EUS and TRUS are important modalities for evaluating local tumor invasion and lymph node metastasis. Therefore, it is very important to choose and utilize the two technologies during the preoperative evaluation of rectal cancer.

In this study, the diagnostic accuracy of EUS for T staging of rectal cancer was 90.8%, with uT staging being overestimated in nine cases and underestimated in 15 cases. EUS showed the highest sensitivity of 85.7%, and the highest specificity of 98.2% for distinguishing uT1. Conversely, it showed the lowest sensitivity of 75.8% for uT4 and the lowest specificity of 85.5% for uT3. The κ coefficient was 0.709. These over- and underestimations were ubiquitous in the sense that the distribution was across different T stages. Overestimation mainly resulted from inflammatory reactions around tumor tissues and the shortcomings of EUS in identifying inflammatory reactions, fibrosis and lymph follicles around the tumor, with misinterpretation of the depth of tumor infiltration resulting in a relatively higher T staging. The technical proficiency and diagnostic experience of surgeons could reduce the incidence of overestimation of T staging and improve the accuracy rate of diagnosis [Citation15]. Underestimation of the depth of tumor infiltration was mainly due to the inability to detect some microinvasions that cannot be detected. Additionally, fecal residue remaining in the rectum and gas in the tumor ulceration can lead to artifacts that reduce the quality of the ultrasound image which, again, affects the accuracy of the evaluation of the depth of tumor infiltration.

The inadequacy of N staging using image-based assessments, despite adequate preoperative T staging, has previously been reported [Citation16]. The reasons for this inadequacy are that perirectal lymph nodes with a maximum diameter ≥5 mm visualized by EUS are regarded as positive and accounted for N staging [Citation17], but some enlarged lymph nodes are actually reactive inflammatory nodes. Moreover, approximately 18% of lymph nodes with metastatic foci are < 5 mm in diameter [Citation18]. As local resection is not suitable for tumors at any T stage, the N staging of EUS is important for the selection of surgical methods. In our study, the accuracy rate of EUS was lower for N than for T staging, with our accuracy rate of 76.7% being lower than the rate that has been reported in previous studies. In our case series, EUS underestimated the N staging in 13 cases and overestimated the staging in 27 cases. EUS showed the highest sensitivity of 85.7% and the highest specificity of 94.0% for distinguishing uN2. Conversely, it showed the lowest sensitivity of 54.3% for uN0 and the lowest specificity of 61.7% for uN1. The κ coefficient was 0.419. Underestimation usually resulted from the presence of smaller metastatic lymph nodes or metastatic lymph nodes that were fused with the intestinal wall and from an unfavorable penetration of the EUS probe, resulting in some metastatic lymph nodes not being detected. Overestimation was largely due to inflammatory reactions of the tumor that caused enlargement of lymph nodes around the tumor, which were misdiagnosed as metastatic lymph nodes. Again, the technical proficiency and diagnostic experience of surgeons are significant factors that can affect the accuracy of N staging. Based on our results, we deem that the evaluation of N staging for rectal cancer by EUS remains difficult.

Valid preoperative assessment after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for advanced rectal cancer patients is crucial to determine the individualized treatment strategy. To predict the pathological stage following neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in patients with rectal cancer, we evaluated the role of EUS in the staging of patients with rectal cancer only to analyze both the accuracy and limitations of this imaging method. The overall accuracy rates of presurgical uT and uN staging were 79.5% and 69.7%, respectively. The uT stage was underestimated in five cases and overestimated in four cases, while the uN stage was underestimated in seven cases and overestimated in three cases (). Dickman et al. evaluated the accuracy of EUS among 138 patients who had undergone preoperative neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, reporting positive predictive values of EUS of 44.6% for uT staging and 22.0% for uN staging [Citation19]. The performance of preoperative EUS in predicting the uT and uN stage of rectal cancer at surgery is poor. Similar to the above studies, we found a reduced accuracy of EUS for preoperative uT and uN staging in patients who had undergone preoperative neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, which might be mainly due to microscopic persistence (understaging) in the wall or to inflammation and scarring of the perirectal fat (overstaging).

Table 4. Comparison on the consistency of preoperative T and N staging following neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in patients with rectal cancer and postoperative pathological T and N staging for rectal cancer by EUS evaluation.

TEM is a minimally invasive surgery that has previously been shown to be effective in treating rectal adenomas and is a reasonable choice in some patients with T1 rectal adenocarcinomas [Citation20,Citation21]. However, TEM may not be effective for the treatment of rectal neoplasms with deeper wall penetration or metastatic nodal involvement.

Kudo [Citation22] proposed a submucosal (sm) classification (sm1 refers to infiltration into the upper third, sm2 into the middle third and sm3 into the lower third of the submucosal layer) that describes the depth of tumor invasion into the submucosa. There are favorable histopathologic features for T1, grade I or II (sm1-2) after TEM according to National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines. Bach et al. [Citation23] reported a multicenter database of 487 rectal cancer patients (253 pT1) treated by TEM and found that depth of the submucosal invasion > sm1 was an independent predictor of local recurrence, while the risks of recurrence for sm2–3 and pT2 lesions were similar. The limitation of TEM in the treatment of more locally advanced tumors is obvious. Lymph node involvement ranges from 12% to 28% in patients with T2 tumors and from 36% to 66% in those with T3 tumors [Citation24]. Borschitz et al. reported local recurrence rates of 29% and 50% for low- and high-risk patients with T2 rectal adenocarcinomas, respectively [Citation25]. Mellgren A et al. compared recurrence and survival rates after treating early rectal cancers with local excision and radical surgery, and the results showed a high rate of local recurrence after local excision (T1 = 18%, T2 = 47%) compared to radical surgery (T1 = 0%, T2 = 6%). There was also a higher rate of overall recurrence, including distant metastases, in the local excision group (T1 = 21%, T2 = 47%) compared to radical surgery (T1 = 9%, T2 = 16%), which was statistically significant for T2 tumors [Citation26].

Therefore, TEM is not indicated for stage T2 tumors, and preoperative evaluation for rectal cancer and application of evidence-based surgical indications are crucial to determine whether or not to proceed with local resection. Successive treatment is not recommended after local resection with favorable histopathologic features, including <3 cm size, T1, grade I or II, no lymphatic or venous invasion, or negative margins. Transabdominal or combined abdominoperineal surgery is still required for >3 cm in size, >T1, with grade III, lymphovascular invasion, positive margin, or sm3 depth of tumor invasion after surgery according to NCCN guidelines [Citation27]. However, Meng WC et al. reported TEM performed in 31 patients with rectal villous adenoma and rectal carcinoma, six of which were T2 or T3 tumors because of multiple comorbidities, poor chest function, and advanced age. As a result, TEM can also serve as a good option for local palliation of these patients [Citation28].

The surgeon can have a discussion with the patient about the future treatment options if the subsequent TEM specimen is shown to be malignant on pathological examination. The consequences of overstaging on EUS are worse than understaging because once a patient has undergone radical surgery this decision cannot be rescinded, whereas if a TEM specimen’s histology subsequently shows a poor oncological outcome, radical surgery can still be performed. For this reason, the EUS increases the confidence that an advanced tumor is not suitable for TEM [Citation10].

Over our one to three years of follow-up of the 12 patients treated with TEM, local recurrence and distant metastasis were not observed. The study by Zieren et al. reported a longer hospital stay and higher rates of complications and bleeding with TEM than total mesorectal excision (TME), but with no differences in the rate of survival and of distant metastasis [Citation29]. However, Doornebosch PG et al. reported that the quality of life after surgery was significantly superior after TEM than that after radical resection for rectal cancer, especially for patients who underwent combined abdominoperineal resection [Citation30]. As a minimally invasive surgical technique, TEM also has the advantage of little injury and fast recovery, which plays an important role in the treatment of early rectal cancer. Accurate preoperative staging of rectal cancer is necessary for surgeons to appropriately counsel patients regarding the risks and benefits of local resection compared to radical resection.

Conclusion

EUS has greatly advanced over the past 20 years, with proven benefit for the diagnosis and treatment of a variety of benign and malignant conditions. It is now established as a key component of the staging of rectal cancers, with demonstrated high sensitivity, specificity, safety, and cost-effectiveness. Although the limitations of EUS for preoperative staging for rectal cancer need to be fully appreciated, EUS remains one of the most reliable methods for preoperative staging of rectal cancer and, thus, provides a distinct benefit when developing individualized treatment plans for patients with rectal cancer. According to our data, we affirm that EUS offers high accuracy for rectal cancer staging, with a good correlation with histological T staging. At the same time, it can be of significant benefit to guide the treatment of patients with early rectal cancer who are undergoing TEM.

Declarations of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Trial registration

Chinese Clinical Trial Registry, ChiCTR1800016250. Registered 22 May 2018 - Retrospectively registered.

References

- Kolligs FT. Diagnostics and epidemiology of colorectal cancer. Visc Med. 2016;32:158–164.

- Herzog T, Belyaev O, Chromik AM, et al. TME quality in rectal cancer surgery. Eur J Med Res. 2010;15:292–296.

- Puli SR, Bechtold ML, Reddy JB, et al. How good is endoscopic ultrasound in differentiating various T stages of rectal cancer? Meta-analysis and systematic review. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:254–265.

- Samee A, Selvasekar CR. Current trends in staging rectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:828–834.

- Saclarides TJ. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2015;28:165–175.

- Chen WJ, Wu N, Zhou JL, et al. Full-thickness excision using transanal endoscopic microsurgery for treatment of rectal neuroendocrine tumors. WJG.. 2015;21:9142.

- Hildebrandt U, Feifel G. Preoperative staging of rectal cancer by intrarectal ultrasound. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985;28:42–46.

- Marone P, de Bellis M, Avallone A, et al. Accuracy of endoscopic ultrasound in staging and restaging patients with locally advanced rectal cancer undergoing neoadjuvant chemoradiation. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2011;35:666–670.

- Kocaman O, Baysal B, Şentürk H, et al. Staging of rectal carcinoma: MDCT, MRI or EUS. Single center experience. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2014;25:669–673.

- Mondal D, Betts M, Cunningham C, et al. How useful is endorectal ultrasound in the management of early rectal carcinoma? Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014;29:1101–1104.

- Halefoglu AM, Yildirim S, Avlanmis O, et al. Endorectal ultrasonography versus phased-array magnetic resonance imaging for preoperative staging of rectal cancer. WJG. 2008;14:3504–3510.

- Krajewski KM, Kane RA. Ultrasound staging of rectal cancer. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2008;29:427–432.

- Burdan F, Sudol-Szopinska I, Staroslawska E, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging and endorectal ultrasound for diagnosis of rectal lesions. Eur J Med Res. 2015;20:4.

- Kim MJ. Transrectal ultrasonography of anorectal diseases: advantages and disadvantages. Ultrasonography. 2014;34:19–31.

- Cartana ET, Gheonea DI, Saftoiu A. Advances in endoscopic ultrasound imaging of colorectal diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:1756–1766.

- Colombo PE, Patani N, Bibeau F, et al. Clinical impact of lymph node status in rectal cancer. Surg Oncol. 2011;20:e227–e233.

- Jurgensen C, Teubner A, Habeck JO, et al. Staging of rectal cancer by EUS: depth of infiltration in T3 cancers is important. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:325–328.

- Cartana ET, Parvu D, Saftoiu A. Endoscopic ultrasound: current role and future perspectives in managing rectal cancer patients. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2011;20:407–413.

- Dickman R, Kundel Y, Levy-Drummer R, et al. Restaging locally advanced rectal cancer by different imaging modalities after preoperative chemoradiation: a comparative study. Radiat Oncol. 2013;8:278.

- Quaresima S, Balla A, D’Ambrosio G, et al. Endoluminal loco-regional resection by TEM after R1 endoscopic removal or recurrence of rectal tumors. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2016;25:134–140.

- Kanehira E, Tanida T, Kamei A, et al. A single surgeon's experience with transanal endoscopic microsurgery over 20 years with 153 early cancer cases. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2014;23:5–9.

- Kudo S. Endoscopic mucosal resection of flat and depressed types of early colorectal cancer. Endoscopy. 1993;25:455–461.

- Bach SP, Hill J, Monson JR, et al. Association of coloproctology of Great B, Ireland transanal endoscopic microsurgery C: a predictive model for local recurrence after transanal endoscopic microsurgery for rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2009;96:280–290.

- Heidary B, Phang TP, Raval MJ, et al. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery: a review. Can J Surg. 2014;57:127–138.

- Borschitz T, Heintz A, Junginger T. Transanal endoscopic microsurgical excision of pT2 rectal cancer: results and possible indications. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:292–301.

- Mellgren A, Sirivongs P, Rothenberger DA, et al. Is local excision adequate therapy for early rectal cancer? Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1064–1071.

- Network NCC: National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Guidelines (Version2.2018, Rectal Cancer). Accessed June 27, 2018.

- Meng WC, Lau PY, Yip AW. Treatment of early rectal tumours by transanal endoscopic microsurgery in Hong Kong: prospective study. Hong Kong Med J. 2004;10:239–243.

- Zieren J, Paul M, Menenakos C. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) vs. radical surgery (RS) in the treatment of rectal cancer: indications, limitations, prospectives. A review. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2007;70:374–380.

- Doornebosch PG, Tollenaar RA, Gosselink MP, et al. Quality of life after transanal endoscopic microsurgery and total mesorectal excision in early rectal cancer. Colorect Dis. 2007;9:553–558.