Abstract

Introduction

This was a single-center pilot study that sought to describe an innovative use of 4DryField® PH (premix) for preventing the recurrence of intrauterine adhesions (IUAs) after hysteroscopic adhesiolysis in patients with Asherman’s syndrome (AS).

Material and methods

Twenty-three patients with AS were enrolled and 20 were randomized (1:1 ratio) to intrauterine application of 4DryField® PH (n = 10) or Hyalobarrier® gel (n = 10) in a single-blind manner. We evaluated IUAs (American Fertility Society [AFS] score) during initial hysteroscopy and second-look hysteroscopy one month later. Patients completed a follow-up symptoms questionnaire three and reproductive outcomes questionnaire six months later.

Results

The demographic and clinical characteristics, as well as severity of IUAs, were comparable in both groups. The mean initial AFS score was 9 and 8.5 in the 4DryField® PH and Hyalobarrier® gel groups, respectively (p = .476). There were no between-group differences in AFS progress (5.9 vs. 5.6, p = .675), need for secondary adhesiolysis (7 vs. 7 patients, p = 1), and the follow-up outcomes.

Conclusion

4DryField® PH could be a promising antiadhesive agent for preventing the recurrence of IUAs, showing similar effectiveness and safety to Hyalobarrier® gel. Our findings warrant prospective validation in a larger clinical trial.

Clinical trial registry number

ISRCTN15630617

Introduction

Asherman’s syndrome (AS) is a multifaceted condition characterized by intrauterine adhesions (IUAs) and clinical symptoms such as hypo/amenorrhea, cyclic pelvic pain, and infertility [Citation1–5]. It is caused by trauma to the basal layer of the endometrium. The recently pregnant uterus seems to be more prone to damage of the endometrial basal layer [Citation6]. Risk factors for AS include intrauterine surgery (e.g., dilatation and curettage [D&C]) or procedures potentially involving the uterine cavity (e.g., myomectomy, embolization of uterine arteries) [Citation7,Citation8].

Hysteroscopy has become the standard method to diagnose and treat AS [Citation1]. We can classify IUAs as primary or secondary depending on whether they reoccur after previous hysteroscopic adhesiolysis. The prevalence of secondary IUAs ranged from 20% to 62.5% in previous studies [Citation9,Citation10]. Because many patients with AS require repeated lysis, AS is challenging to treat [Citation11].

Owing to the complexity of AS and its treatment, as well as the uncertain reproductive prognosis of women with AS, we believe that the prevention of secondary IUAs is a critical part of therapy. The most commonly used antiadhesive applied in the uterine cavity is hyaluronic acid gel, which had beneficial effects in several studies [Citation12]. The results were summarized in a recent meta-analysis and review, which showed that using hyaluronan gel is a safe and effective method to prevent recurrence of IUAs [Citation13].

To our knowledge, there are no studies in which 4DryField® PH (PlantTech Medical GmbH, Lüneburg, Germany) was instilled in the uterine cavity for preventing the recurrence of IUAs. Therefore, the aim of our study was to evaluate the effect of using 4DryField® PH compared to Hyalobarrier gel® (Anika Therapeutics, Padova, Italy) for preventing the recurrence of IUAs in women with AS.

Material and methods

Study design and setting

This prospective, randomized controlled, single-blinded, pilot, feasibility study was conducted at the Department of Gynecological Endoscopy and Minimally Invasive Surgery of the General University Hospital in Prague, an international teaching center for gynecological endoscopy and a tertiary care national reference center for treating women with AS and other surgically challenging reproductive issues. The patients were recruited between March 2022 and September 2022. Data collection was finished in January 2023. All patients provided written informed consent. This study was approved by the local Ethics Committee and the local Institutional Review Board, and registered on the ISRCTN Registry (15630617).

Study population

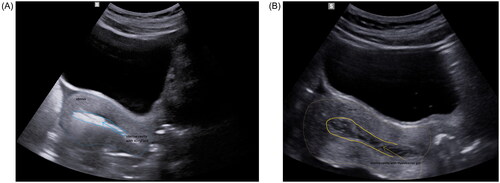

In total, 23 patients with suspected AS were screened and completed a health questionnaire focusing on their medical history, general physical condition, history of previous gynecological surgery, obstetric history, menstrual pattern, and other symptoms possibly related to AS (e.g., cyclic pelvic pain). Patients were randomized into two groups and blinded to which of the two medical devices they would receive. Three patients were not randomized due to mild adhesion in two patients and perioperative recognition of the uterine perforation in one patient. Therefore, 20 patients were randomized to either group A, in which 4DryField® PH was used as an antiadhesive barrier (n = 10) () or to group B, in which Hyalobarrier® gel was applied (n = 10) ().

Figure 1. Vaginal ultrasound images of the uterus after hysteroscopic adhesiolysis with final instillation of (A) 4DryField® PH (group A) or (B) Hyalobarrier® gel (group B).

Women aged 18–45 years were eligible if they wished to conceive in the near future, had moderate or severe IUAs corresponding to an American Fertility Society score (AFS) of ≥5 detected during hysteroscopy [Citation14], and if they provided informed consent.

Women were excluded from the study if they disagreed to participate in the study, were aged <18 years or >45 years, had mild IUAs or no IUAs detected during primary hysteroscopy (AFS <5), if perforation of the uterus was diagnosed during initial hysteroscopy, or if primary hysteroscopic resection was insufficient and made it impossible to achieve a sufficient capacity of the uterine cavity (90%–100%) during the first procedure.

Surgical technique

All patients underwent primary hysteroscopy under general anesthesia. In the first step, a rigid 5.5-mm diagnostic hysteroscope (Olympus Surgical Technologies Europe, Olympus Winter & IBE GmbH, Hamburg, Germany) was used to verify the diagnosis and to classify the stage of AS. In the second step the operative 8.0-mm-wide hysteroscope (Olympus Surgical Technologies Europe) was employed when treatment was needed. Saline solution was used to distend the uterine cavity. The intrauterine pressure was maintained between 70 and 100 mmHg. All procedures were navigated by ultrasound with optimal filling of the urinary bladder (200–300 ml of saline solution). The uterine cavity was observed and the primary AFS score was determined by two senior surgeons before performing adhesiolysis. Intrauterine adhesiolysis was performed using cold scissors while avoiding excessive bleeding and unnecessary damage or tissue hypoxia (possibly caused by electrocautery) to the healthy endometrium. The goal of hysteroscopic reconstruction of the uterine cavity was to create a sufficiently spacious cavity for future pregnancy, of ≥90% of the primary uterine cavity volume, which was assessed and compared to the pre-adhesiolysis state by two senior surgeons using hysteroscopic and sonographic methods simultaneously in a single procedure. The antiadhesive agent was then instilled inside the cavity (). 4DryField® PH was applied as a viscous gel (premix), which was prepared by mixing 3 g of 4DryField® PH with 18 ml of sterile saline solution. This concentration was empirically determined by our surgeons with agreement from the manufacturer (PlantTec Medical). Ten milliliters of Hyalobarrier® gel was instilled into the uterine cavity in the standard formulation and form stated by the manufacturer (Anika Therapeutics).

All subjects were administered with hormonal therapy for one month: 6 mg estrogen per day (Estrofem® 2 mg, Novo Nordisk A/S, Bagsværd, Denmark) plus 20 mg dydrogesterone per day (Duphaston® 10 mg, Abbott Biologicals B.V., Olst, The Netherlands) in the second half of the menstrual cycle. One month later, second-look hysteroscopy was performed and the secondary AFS score was determined. If necessary, secondary adhesiolysis was performed. The patients were then encouraged to conceive with or without the use of assisted reproduction techniques depending on their wishes and further reproductive context.

Follow-up questionnaire

Three months after the second-look hysteroscopy, all of the women were sent a questionnaire asking about their symptoms, menstrual pattern, complications, and reproductive health. Six months after the surgery all patients were asked about their reproductive outcomes again. Responses were obtained from all subjects and the data were analyzed.

Statistical analysis

The patients were randomized into groups A and B at the time of primary hysteroscopy at a 1:1 ratio, resulting in ten patients in each group. The two-sample t test with Welch correction was used to compare the following numerical covariates recorded prior to treatment between the two groups: age, body mass index (BMI), and number of D&C procedures performed prior to symptoms of AS. The following binary covariates were analyzed using the difference in probabilities test: medical history of chronic internal and gynecological diseases, prior gynecological surgery, origin of AS due to D&C for first trimester abortion/difficult removal of placenta after labor, nulliparity, menstrual pattern, cyclic pelvic pain, secondary sterility, and primary AFS score. We also analyzed between-group differences in the follow-up period for restoration of menstrual pattern, final capacity of the uterine cavity, and the need for secondary adhesiolysis. These comparisons were made using the ratio test, in which the null hypothesis was the absence of between-group differences in these outcomes. ΔAFS from before to after treatment was evaluated using a linear model. The effect of treatment was adjusted by the primary AFS, based on the specific values for moderate adhesions (AFS 7–9) and severe adhesions (AFS 10–12). ΔAFS was determined as the primary AFS score minus the secondary AFS score. Greater ΔAFS indicates a better clinical effect of the antiadhesive agent. The significance of the effect of the treatment was determined using the likelihood ratio test. Statistical significance was set at p < .05.

Results

Both groups comprised ten women. Three subjects were excluded before randomization. There were no between-group differences in baseline characteristics (age and BMI) and medical history (). Both groups were also comparable in terms of their symptoms and severity of AS (). The mean primary AFS score was not significantly different between the two groups (9 vs. 8.5, p = .476).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics and medical history.

Table 2. Symptoms before treatment.

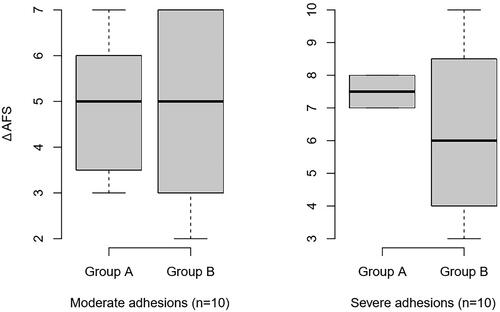

ΔAFS was 0.3 points greater in group A than in group B, although this was not significantly different (5.9 vs. 5.6, p = .675) (). When we compared the two groups with respect to the severity of disease, the expected ΔAFS was 0.38 lower in group B than in group A (p = .675, 95% confidence interval [CI] − 1.50 to 2.26). The expected AFS progress was 1.9 higher in patients with severe IUAs than in patients with moderate IUAs (p = .06, 95% CI −0.15 to 3.65) ().

Figure 2. Box plots of ΔAFS (range) in subgroups of patients with moderate (A) or severe (B) adhesions. Thick horizontal bars, boxes, and whiskers represent the mean, standard deviation, and range, respectively. AFS, American Fertility Society.

Table 3. Main results.

The secondary capacity of the uterine cavity was not significantly different between the two groups (86% vs. 84%, p = .671; two-sample t test with Welch correction).

During the follow-up, restoration of the menstrual pattern to eumenorrhea was achieved in the same number of patients per group (8 vs. 8, p = 1.000), a similar number of patients had hypomenorrhea (1 vs. 2), and one patient had amenorrhea in group A. Regarding complications, one patient in group A and two patients in group B reported pelvic pain, which was most probably related to their other gynecological problems as ovarian cyst and condition after recent oocyte retrieval. No other complaints were recorded. Thus, the complication rate was not significantly different between the two groups.Women in both groups achieved a comparable number of pregnancies after treatment (). However, we registered one patient with amenorrhea in group A. This woman underwent laparoscopic salpingectomy due to extrauterine tubal pregnancy and during this procedure D&C was performed, thus resulting in recurrence of AS.

Table 4. Follow-up outcomes.

We did not record any procedure- or device-associated adverse events during the study.

Discussion

IUAs recur after hysteroscopic adhesiolysis in up to 62.5% of women [Citation10,Citation15]. Several methods for preventing secondary IUAs have been described and used over the last few decades, but a superior technique has not been established [Citation16–18]. Many studies using different medical devices, reporting varying effectiveness, have been published. 4DryField® PH is a modified starch that has long been used in abdominal and pelvic surgery [Citation19]. To our knowledge, this is the first study to apply 4DryField® PH as a premix into the uterine cavity after adhesiolysis to prevent de novo adhesions.

The optimal properties of antiadhesive agents have been well defined in previous studies [Citation20,Citation21]. These properties include good biocompatibility, low immunogenicity, high mechanical strength, and biodegradability. These properties ensure that the medical device can efficiently reach the site of tissue injury without fear of rejection and are strong enough to support the uterine cavity to reduce the formation of fibrosis. The degradation rate should match the repair process of the endometrium, and the material should be completely biodegraded without harming the body. Considering these properties, the consistency of 4DryField® PH premix seems to be particularly convenient. This premix, which has a very viscous gelatinous consistency, can remain at the site of tissue injury without being washed away by uterine fluid to maintain a protective barrier for a sufficiently long time (up to seven days). Furthermore, the premix fulfills other required properties, including good tolerability, an appropriate safety profile, and is easy to apply into the uterine cavity.

Many classification and scoring systems have been proposed in an effort to unify the description of the extent and clinical presentation of AS [Citation22]. For the purpose of our study, we used the AFS classification because we consider it to be the clearest and most concise system.

At first glance, the achieved effect of treatment seems to be promising (), but we should remember the best results of the treatment of AS (i.e., normal menstrual pattern, no cyclic pain, ability to conceive) are observed a few months after surgery, and the outcomes can change over time. Some patients may experience recurrence of their symptoms of AS, especially after further intrauterine procedures (e.g., D&C for missed abortion). In the follow-up period we registered one patient with amenorrhea in group A. This woman experienced an extrauterine tubal pregnancy, which was managed laparoscopically. Laparoscopic salpingectomy was done but unfortunately D&C was also performed.

We are aware of some limitations of our study, particularly the small number of patients in each group. A larger prospective randomized controlled study is needed to validate or refute our findings. To ensure that the surgical assessment of the uterine cavity was not considered subjective, the assessment was done surgically, with hysteroscopic and sonographic evaluation. The AFS score was determined by two experienced surgeons at all times in all women. We cherish the value of two-dimensional and particularly three-dimensional ultrasound preoperatively to assess the stage of AS in accordance with published papers [Citation23]. We did ultrasound examination prior to hysteroscopy as well as perioperatively to navigate the surgeon to increase safety of the procedure.

Although this is just a pilot study, we sought to obtain preliminary information on the reproductive outcomes of our patients, because these are of the greatest importance to them [Citation24].

We should also consider the strengths of our study, including its prospective randomized, controlled, study design with control group and that it is the first study of its kind to investigate a novel use of 4DryField® PH.

Conclusion

The intent was to propose an innovative use of 4DryField® PH, and to investigate its efficacy and safety in patients with AS. Our findings suggest that 4DryField® PH may be as effective as Hyalobarrier® gel for preventing secondary IUAs in patients with AS. 4DryField® PH is a promising antiadhesive barrier in patients with severe IUAs.

Statement

The original article has not been published and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere.

Date and number of IRB

November 30, 2021, Ethics Committee of the General Faculty Hospital, Prague, 119/21 S-IV.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their great gratitude to Mr. Jaromir Macoun for statistical consultations and analysis of the results. The authors also acknowledge Nicholas D. Smith PhD for assistance with English-language scientific editing.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. All medical devices used during the study were supplied at no cost by DahlhausenCZ without conditions for use.

Data availability statement

All data generated and analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).

Additional information

Funding

References

- March CM. Management of asherman’s syndrome. Reprod Biomed Online. 2011;23(1):63–76. doi:10.1016/j.rbmo.2010.11.018.

- Yu D, Wong YM, Cheong Y, et al. Asherman syndrome–one century later. Fertil Steril. 2008;89(4):759–779. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.02.096.

- Asherman JG. Amenorrhoea traumatica (atretica). J Obstet Gynaecol Br Emp. 1948;55(1):23–30. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1948.tb07045.x.

- Asherman JG. Traumatic intrauterine adhesions. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Emp. 1950;57(6):892–896. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1950.tb06053.x.

- Asherman JG. Traumatic intrauterine adhesions and their effects on fertility. Int J Fertil. 1957;2:49–54.

- Schenker JG, Margalioth EJ. Intrauterine adhesions: an updated appraisal. Fertil Steril. 1982;37(5):593–610. doi:10.1016/s0015-0282(16)46268-0.

- Sebbag L, Even M, Fay S, et al. Early second-look hysteroscopy: prevention and treatment of intrauterine post-surgical adhesions. Front Surg. 2019;6:50. doi:10.3389/fsurg.2019.00050.

- Mara M, Horak P, Kubinova K, et al. Hysteroscopy after uterine fibroid embolization: evaluation of intrauterine findings in 127 patients. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2012;38(5):823–831. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0756.2011.01782.x.

- Hanstede MF, Van der Meij E, Goedemans L, et al. Results of centralized asherman surgery, 2003-2013. Fertil Steril. 2015;104(6):1561–1568.e1. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.08.039.

- Warembourg S, Huberlant S, Garric X, et al. Prevention and treatment of intra-uterine synechia: review of literature. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2015;44(4):366–379. doi:10.1016/j.jgyn.2014.10.014.

- Dreisler E, Kjer JJ. Asherman’s syndrome: current perspectives on diagnosis and management. Int J Womens Health. 2019;11:191–198. doi:10.2147/IJWH.S165474.

- Fei Z, Xin X, Fei H, et al. Meta-analysis of use of hyaluronic acid gel to prevent intrauterine adhesions after miscarriage. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;244:1–4. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2019.10.018.

- Unanyan A, Pivazyan L, Krylova E, et al. Comparison of effectiveness of hyaluronan gel, intrauterine device and their combination of prevention of adhesions in patients after intrauterine surgery: systemic review and meta analysis. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2022;51(4):102334. doi:10.1016/j.jogoh.2022.102334.

- The American fertility society classifications of adnexal adhesions, distal tubal occlusion, tubal occlusion secondary to tubal ligation, tubal pregnancies, müllerian anomalies and intrauterine adhesions. Fertil Steril. 1988;49:944–955. doi:10.1016/s0015-0282(16)59942-7.

- Abudukeyoumu A, Li MQ, Xie F. Transforming growth factor-B1 in intrauterine adhesion. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2020;84(2):e13262. doi:10.1111/aji.13262.

- Vitale SG, Riemma G, Carugno J, et al. Post surgical barrier strategies to avoid the recurrence of intrauterine adhesion formation after hysteroscopic adhesiolysis: a network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;226(4):487–498.e8. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2021.09.015.

- Zhou Q, Shi X, Saravelos S, et al. Auto-cross-linked hyaluronic acid gel for prevention of intrauterine adhesions after hysteroscopic adhesiolysis: a randomized controlled trial. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28(2):307–313. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2020.06.030.

- Bosteels J, Weyers S, D’Hooghe TM, et al. Anti-adhesion therapy following operative hysteroscopy for treatment of female subfertility. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;11:CD011110. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011110.

- Krämer B, Neis F, Brucker SY, et al. Peritoneal adhesions and their prevention - current trends. Surg Technol Int. 2021;38:221–233. doi:10.52198/21.STI.38.HR1385.

- Guiyang C, Zhipeng H, Wei S, et al. Recent developments in biomaterial-based hydrogel as the delivery system for repairing endometrial injury. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022;10:894252. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2022.894252.

- Wang J, Yang C, Xie Y, et al. Application of bioactive hydrogels for functional treatment of intrauterine adhesion. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2021;9:760943. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2021.760943.

- Manchanda R, Rathore A, Carugno J, et al. Classification systems of asherman’s syndrome. An old problem with new directions. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2021;30(5):304–310. doi:10.1080/13645706.2021.1893190.

- Knopman J, Copperman AB. Value of 3D ultrasound in the management of suspected asherman’s syndrome. J Reprod Med. 2007;52(11):1016–1022.

- Mara M, Borcinova M, Lisa Z, et al. The perinatal outcomes of women treated for asherman syndrome: a propensity score-matched cohort study. Hum Reprod. 2023;38:1297–1304. doi:10.1093/humrep/dead092.