Abstract

A unique database named ‘AN-SAPO’ was developed by Iwato Corp. and Japan Brain Corp. in collaboration with the psychiatric clinics run by Himorogi Group in Japan. The AN-SAPO database includes patients’ depression/anxiety score data from a mobile app named AN-SAPO and medical records from medical prescription software named ‘ORCA’. On the mobile app, depression/anxiety severity can be evaluated by answering 20 brief questions and the scores are transferred to the AN-SAPO database together with the patients’ medical records on ORCA. Currently, this database is used at the Himorogi Group’s psychiatric clinics and has over 2000 patients’ records accumulated since November 2013. Since the database covers patients’ demographic data, prescribed drugs, and the efficacy and safety information, it could be a useful supporting tool for decision-making in clinical practice. We expect it to be utilised in wider areas of medical fields and for future pharmacovigilance and pharmacoepidemiological studies.

Introduction

The number of patients with depression is rapidly increasing worldwide, with an estimated 350 million people affected. Especially in case of depression that is chronic and of moderate or severe intensity, it may become a serious health condition (World Health Organization Citation2016). The majority of patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) present with typical anxiety symptoms. Approximately 95% of MDD patients have psychological anxiety symptoms and 85% have somatic anxiety symptoms (Hamilton Citation1983). Joffe et al. (Citation1993) reported that MDD patients with high levels of anxiety had greater severity of depressive illness and functional impairment, and the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study found that MDD with anxiety symptoms had poorer acute outcomes than MDD without anxiety symptoms following antidepressant treatment (Fava et al. Citation2008). In addition, the presence of comorbid psychiatric conditions appears to have a detrimental effect on the prognosis and outcome of medical illnesses (Lecrubier Citation2001); hence, total care and total management of these disorders or symptoms are essential to restore patients’ quality of life and alleviate the burden on the health services.

Scales of depression and anxiety symptoms

The 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D17) (Hamilton Citation1960) and the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (Montgomery & Asberg Citation1979) are the most widely used instruments to measure the level of depression in clinical trials. Anxiety scales that are used throughout the world include the Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety (HAM-A) (Hamilton Citation1969) and the Sheehan Patient-Rated Anxiety Scale (SPRAS) (Sheehan & Harnett-Sheehan Citation1990). Since it takes considerable time to evaluate depression/anxiety symptoms using these scales, however, they are rarely used in clinical practice. To resolve this problem, Himorogi Psychiatric Institute developed brief self-rating depression/anxiety scales (10 items for each scale) making the evaluation of items in depression and anxiety scales that had been developed for Western culture applicable to Japanese culture (Himorogi Self-Rating Depression Scale [HSDS]) (Mimura et al. Citation2011a) and (Himorogi Self-Rating Anxiety Scale [HSAS]) (Mimura et al. Citation2011b). Since the two scales provide patient-reported outcomes, they can contribute to eliminating possible bias that can be caused by observer-rated reports. In addition, the 10 items in each scale are easy to answer, which makes them appropriate to be used in daily clinical practice. High correlation was demonstrated between the HSDS and the Japanese version of the HAM-D17, and between the HSAS and the Japanese versions of the Hamilton Rating Scale for the Anxiety Scale Interview Guide (HAMA-IG) (Bruss et al. Citation1994) as well as the SPRAS. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the HSDS and the HSAS were 0.85 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.82–0.88) and 0.87 (95% CI: 0.85–0.90), respectively, which showed sufficient reliability (Mimura et al. Citation2011a, Citation2011b).

Unique database for gathering data from a mobile app, named AN-SAPO and medical prescription software, named ‘ORCA’

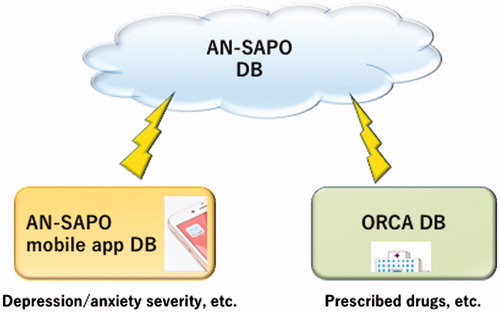

In 2013, Iwato Corp. and Japan Brain Corp. developed a unique mobile app named ‘AN-SAPO mobile app’ (Iwato Corp. and Japan Brain Corp. Citation2013), which is an abbreviation for ‘Anshin Sapo-to’ in Japanese, meaning ‘relief support’ in English, on the basis of an idea of one of the authors, Yoshinori Watanabe (head director of Himorogi Psychiatric Institute) in response to needs in the aftermath of the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake (Watanabe Citation2013). With this app, users can evaluate their severity of depression/anxiety by answering the brief questions of HSDS/HSAS wherever they are at any time, and their HSDS/HSAS scores are recorded on the app. Users can also record the details of their medications such as drug names and set alarms on their smartphones to remind themselves of the time to take medications. It is also possible to follow sequential changes in the HSDS and HSAS scores as well as changes in the number of medicines in graphs, and compare these data with the averages of the total AN-SAPO users. There are more than 20,000 users of this app in Japan (as of January 2017). Iwato Corp. and Japan Brain Corp. also developed a unique database named ‘AN-SAPO database’ (), which includes patients’ HSDS and HSAS scores collected with the AN-SAPO mobile app (Iwato Corp. and Japan Brain Corp. Citation2013; Watanabe Citation2013) and patient data collected from medical prescription software named ‘ORCA’ (Online Receipt Computer Advantage) (Japan Medical Association Citation2016), which is also used as medical practitioners’ receipt for health insurance claim. ORCA, which is used at 16,122 hospitals/clinics in Japan (as of 15 February 2017) (Japan Medical Association Citation2017), was launched by Japan Medical Association in 2002 in the view to promoting Information Technology in medical paperwork processing. Patient information in ORCA such as prescription records can be collected and anonymised to be used as data if patients’ consent and approval by an institutional review board are obtained. As of January 2017, the AN-SAPO database is used at the psychiatric clinics run by Himorogi Group. More than 2000 patients’ data have been accumulated since November 2013. This database covers patients’ demographic data, information on prescribed drugs, efficacy (HSDS and HSAS) and safety data (adverse events). Therefore, we expect that the database can be a useful data source to collect and analyse patient-reported outcomes in combination with receipt records. For this study, we obtained all patients’ consent for secondary use of their data and our study was approved by the internal Institutional Review Board. A total of 1301 patients (female: 672; male: 629) who continued to visit Himorogi Group’s psychiatric clinics for longer than 2 years without an absence of more than 3 months were included (data extraction date: 14 November 2015). The mean age (standard deviation) was 48.56 (17.35) years. The number of patients (%) are 28 (2.2%) aged under 18 years, 573 (44.0%) aged 18–44 years, 464 (35.7%) aged 45–64 years and 236 (18.1%) aged 65 years and older as of 31 October 2015.

Examples of the utilisation of AN-SAPO database

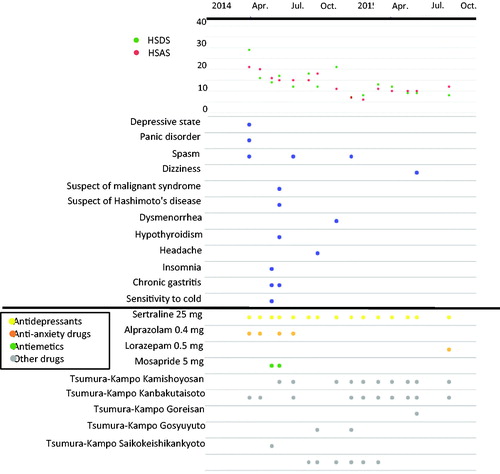

The sequential changes in the HSDS and HSAS scores and information on diagnoses, adverse events and prescribed drugs over time collected in the AN-SAPO database can easily be visualised using a JavaScript library for manipulating documents on the basis of data (Data Driven Documents JavaScript [D3.js]) (D3.js Citation2015). The classification of drugs (antidepressants, anti-anxiety drugs, hypnotics and antipsychotics) was that defined by the MHLW (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare in Japan Citation2016) of Japan. is a sample graphic. Symptom changes (HSDS and HSAS scores), prescribed drugs and the occurrence of adverse events can be visually determined for each patient. The monitoring data are useful as a supporting decision-making tool for prescribing doctors.

Database research and conventional post-marketing surveillance

Pharmacoepidemiological studies using various types of database (e.g., claims database and medical record database) have recently attracted attention as a means of evaluating the safety and efficacy of drugs in Western countries (Japan Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association Citation2009). In Japan, however, the conventional methodology of uncontrolled, prospective and observational research is still standard for pharmaceutical company-sponsored post-marketing surveillance (PMS) to collect safety and efficacy information on new drugs, regardless of the individual research question, because the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) of Japan mandates the conduct of PMS of new drugs. Most PMS research has been conducted on thousands of subjects, even after the Guideline on Pharmacovigilance Planning (International Conference on Harmonisation [ICH]-E2E) (ICH Steering Committee Citation2004) based on international consensus was officially released in 2004 (Narukawa Citation2014). Conventional PMS is not cost-effective at all, because it requires huge expenses and human resources, and puts an enormous burden on healthcare providers and pharmaceutical companies compared to the benefit obtained from the results. Furthermore, with conventional PMS, ‘selection bias’ is an unavoidable matter because investigational sites are selected by the sponsor and enrolled patients are selected by physicians contracted by the sponsor. In addition, data obtained from clinical trials for drug development are limited because clinical trials involve limitations known as ‘Five Toos’, that is, (1) too few, (2) too simple, (3) too median-aged, (4) too narrow and (5) too brief (Rogers Citation1987). Therefore, a system of collecting prescription, safety and efficacy information of drugs in actual clinical practice after launch and providing appropriate feedback to patients is essential to evaluate the actual value of new drugs and promote their proper use.

Considering such background, the AN-SAPO database may also be useful as a pharmacovigilance tool for pharmaceutical companies since efficacy and safety data can be collected simultaneously and the effect of drug switching and augmentation can be examined. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of the target and other similar drugs also becomes possible.

Limitations

Limitations of the AN-SAPO database include the presence of unstructured data and narrative fields that have not been extracted, the lack of information on the prescribed dose of each drug, which makes it impossible to examine the effect of dose increases or decreases visually, and the absence of efficient information such as the duration of the underlying diseases and the course of adverse events. These points need to be improved to use this database more efficiently for pharmacovigilance and pharmacoepidemiological studies in the future.

Future perspective

This is the first report introducing AN-SAPO, a unique database that collects data from both a mobile app and medical prescription software. Despite the above-mentioned limitations, the AN-SAPO database could become not only a supporting tool for decision-making in clinical practice but also a potentially useful data source as a pharmacovigilance tool for pharmaceutical companies. Moreover, the use of modern technology such as mobile apps and database software in clinical practice may play an important role in the psychiatric field as well as in other areas of medical treatment. For example, depressive symptoms that might be caused by somatic diseases such as cancer, diabetes or heart disease (Polsky et al. Citation2005; Patten et al. Citation2016) could be detected/treated more easily when patient data become available as a common tool between psychiatrists and physicians in other medical fields through the utilisation of modern technology. So far, this database has been used only at limited psychiatric clinics, but we expect it to be used in wider areas of medical fields for prevention and treatment of psychiatric diseases such as depression and for future pharmacovigilance and pharmacoepidemiological studies.

Geolocation information

This study was conducted in Japan.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Mr. Yasutaka Yamamoto of Megumi Inc. and Mr. Kazutaka Onodera of Japan Brain Corp. for extracting and cleaning of data.

Disclosure statement

Yoshinori Watanabe is the originator of the AN-SAPO mobile app as well as AN-SAPO database, and the head director of Himorogi Group. Yoshinori Watanabe has received speaker’s honoraria from Pfizer Japan Inc., GlaxoSmithKline K.K., Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Janssen Pharmaceutical K.K., Meiji Seika Pharma Co., Ltd., Eli Lilly Japan K.K., MSD K.K., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Mochida Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corp. and Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma Co., Ltd. within the past 5 years. Yoko Hirano, Yuko Asami, Maki Okada and Kazuya Fujita are employees of Pfizer Japan Inc., which funded the study.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bruss GS, Gruenberg AM, Goldstein RD, Barber JP. 1994. Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale Interview guide: joint interview and test-retest methods for interrater reliability. Psychiatry Res. 53:191–202.

- D3.js. 2015. [cited 2016 Oct 27]. Available from: https://d3js.org/

- Fava M, Rush AJ, Alpert JE, Balasubramani GK, Wisniewski SR, Carmin CN, Biggs MM, Zisook S, Leuchter A, Howland R, et al. 2008. Difference in treatment outcome in outpatients with anxious versus nonanxious depression: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 165:342–351.

- Hamilton M. 1960. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 23:56–62.

- Hamilton M. 1969. Diagnosis and rating of anxiety. Br J Psychiatry. 3:76–79.

- Hamilton M. 1983. The clinical distinction between anxiety and depression. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 15 :165S–169S.

- ICH Steering Committee. 2004. ICH Harmonised tripartite guideline – pharmacovigilance planning E2E; [cited 2016 Oct 27]. Available from: http://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000156732.pdf

- Iwato Corp. and Japan Brain Corp. 2013. AN-SAPO introduction site; [cited 2016 Oct 27]. Available from: http://www.an-sapo.com/

- Japan Medical Association. 2016. ORCA project; [cited 2016 Oct 27]. Available from: https://www.orca.med.or.jp/receipt/

- Japan Medical Association. 2017. ORCA project; [cited 2016 Oct 27]. Available from: http://www.jma-receipt.jp/operation/index.html

- Japan Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association. 2009. Potential of drug use-results survey data for pharmacoepidemiological research (in Japanese). Jpn J Pharmacoepidemiol. 14:53–59.

- Joffe RT, Bagby RM, Levitt A. 1993. Anxious and nonanxious depression. Am J Psychiatry. 150:1257–1258.

- Lecrubier Y. 2001. The burden of depression and anxiety in general medicine. J Clin Psychiatry. 62:4–9.

- Mimura C, Murashige M, Oda T, Watanabe Y. 2011a. Development and psychometric evaluation of a Japanese scale to assess depression severity: Himorogi Self-rating Depression Scale. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 15:50–55.

- Mimura C, Nishioka M, Sato N, Hasegawa R, Horikoshi R, Watanabe Y. 2011b. A Japanese scale to assess anxiety severity: development and psychometric evaluation. Int J Psychiatry Med. 41:29–45.

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare in Japan. 2016. Points to consider according to the revision of the medical fee (notice) (in Japanese); [cited 2016 Oct 27]. Available from: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/file.jsp?id=335812&name=file/06-Seisakujouh-ou-12400000-Hokenkyoku/0000114868.pdf

- Montgomery SA, Asberg M. 1979. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 134:382–389.

- Narukawa M. 2014. Research on the situation and implications of the post-marketing surveillance study in Japan – Considerations based on a questionnaire survey (in Japanese). RSMP. 4:11–19.

- Patten SB, Williams JV, Lavorato DH, Wang JL, Jetté N, Sajobi TT, Fiest KM, Bulloch AG. 2016. Patterns of association of chronic medical conditions and major depression. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 27:1–9.

- Polsky D, Doshi JA, Marcus S, Oslin D, Rothbard A, Thomas N, Thompson CL. 2005. Long-term risk for depressive symptoms after a medical diagnosis. Arch Intern Med. 13165:1260–1266.

- Rogers AS. 1987. Adverse drug events: identification and attribution. Drug Intell Clin Pharm. 21:915–920.

- Sheehan DV, Harnett-Sheehan K, 1990. Psychometric assessment of anxiety disorders. In: Sartorius N, Andreoli V, Cassano G, Eisenberg L, Kielholz P, Pancheri P, Racagni G, editors. Anxiety: psychobiological and clinical perspectives. New York: Hemisphere Publishing; p. 85–100.

- Watanabe Y. 2013. We can recover from depression if medicines are reduced – new app ‘AN-SAPO’ we can control for ourselves – (in Japanese). 2nd ed. Tokyo: SHUFUNOTOMO Co., Ltd.

- World Health Organization. 2016. Depression, Fact Sheet; [cited 2016 Oct 27]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs369/en/