Abstract

Introduction: Prescribing trends in maintenance therapy of patients with primary psychotic disorders (PSD) may vary worldwide. Present study aimed to investigate prescription patterns in a sample of outpatients with PSD from Serbia.

Methods: In a sample of 73 PSD outpatients we analysed the rate of antipsychotic polypharmacy and psychotropic polypharmacy, concomitant continual benzodiazepine use, and associations between therapy, psychotic symptoms and quality of life.

Results: Maintenance therapy (median daily dose 321 mg of chlorpromazine equivalents) predominantly consisted of monotherapy with second generation antipsychotics (45.2%), followed by antipsychotic polypharmacy based on first and second generation combination (25.0%). The median number of psychotropic drugs was 3. Benzodiazepines were continually prescribed to more than 60% of patients (mean daily dose 2.9 ± 2.0 mg lorazepam equivalents). Patients with benzodiazepine use had significantly more psychotropic medications and more antipsychotic polypharmacy, poorer quality of life and more severe psychopathology in comparison to another group.

Conclusion: The present study demonstrated new information regarding the prescription patterns of psychotropic drugs in outpatients with PSD in Serbia, amplified with clinically relevant information. This study also revealed distinct prescription patterns concerning antipsychotic/benzodiazepine polypharmacy. Overall, such findings are likely to contribute to improving clinical practice and care for patients with PSD in general.

Present exploratory research aimed to elucidate trends of antipsychotics polypharmacy and concomitant use of psychotropic medications including benzodiazepines in the maintenance treatment of outpatients with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, amplified with clinically relevant information (symptoms and quality of life).

‘Antipsychotic (AP) polypharmacy’ was defined as concurrent use of more than one AP for at least 1 month; ‘Psychotropic polypharmacy’ was defined as the combination of AP and a different class of psychotropic drugs medication for at least one month.

The median number of prescribed psychotropic drugs was 3 (mean 3.1 ± 1.1) and the average AP daily dose was moderate (median 321 mg of chlorpromazine equivalents). However, the rates of AP polypharmacy (45.2%) and benzodiazepine prescription on a continual basis (>60%) found in our sample could be considered relatively high.

Outpatients with higher AP daily dose and higher BPRS symptom score were receiving more benzodiazepines.

For improvement of the local, as well as general clinical practice and care for patients with psychotic disorders, and for education in psychiatry, such analyses need to be done on a regular basis and on larger samples.

Keypoints

Introduction

Pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia and other primary psychotic disorders (PSD) consists of acute phase and maintenance phase therapy according to contemporary international and national guidelines for their treatment (Lehman et al. Citation2004; Lečić-Tosevski Citation2013). Continuous use of antipsychotic (AP) drugs, which starts during the acute illness phase, is recommended during the maintenance phase treatment (Leucht et al. Citation2012). Throughout this phase of therapy, symptoms of psychosis should be significantly reduced and the treatment goals are to avoid relapses and to promote recovery towards integration into society.

Although AP monotherapy is the standard approach for managing symptoms of PSD (Hasan et al. Citation2013), with currently available compounds it proves to be insufficient in a significant number of patients (Zink et al. Citation2010). Thus, multiple medications may be often prescribed, even beyond the acute phase of the illness. According to the current national guideline for treatment of patients with PSD, add-on benzodiazepine (BZD) treatment could be considered as an augmentation strategy, whereas clinical indications include agitation, anxiety and catatonic signs and symptoms (Lečić-Tosevski Citation2013). However, the recommended duration or dose of such add-on treatment has not been provided in the Serbian guidelines.

Amongst PSD outpatients, prescribing multiple APs may result in high rates of adverse outcomes, metabolic disturbances, societal burden and impaired quality of life (Cetin Citation2014; Sun et al. Citation2014). Moreover, it has been speculated that AP polypharmacy is associated with increased mortality; however, there are no methodologically sound studies available to date to support the assumption of causality (Tiihonen et al. Citation2012). Nevertheless, growing evidence suggests that long-term utilisation of benzodiazepines (BZD) and of anti-cholinergic medication (ACM) during the maintenance therapy of PSD is associated with higher rates of adverse outcomes. BZD use has been linked with increased mortality risk in patients with schizophrenia (Fontanella et al. Citation2016), while medications that raise serum anticholinergic activity have been shown to adversely affect cognition (Vinogradov et al. Citation2009). Regular reviews of both BZD and ACM use, which could be expected in approximately one-third of the cases (Vares et al. Citation2011), are desirable to improve clinical practice.

Mental health-care practice in Central and Eastern European countries remains ‘a blind spot on the global mental health map’ (Winkler et al. Citation2017). In Serbia, the cross-sectional evaluation of patients at discharge from one university psychiatric hospital performed ten years ago has shown that majority of PSD patients were prescribed with more than one AP and more than 3 different psychotropic drugs in total (Maric et al. Citation2011). The most frequent AP combination at that time was the concomitant use of two first generation antipsychotics (FGAs). Moreover, according to more recent large-scale study of hospital discharge BZD prescription in this region (Croatia, North Macedonia and Serbia), patients with PSD had higher odds of receiving BZDs (80.4%) in comparison to patients with all other ICD-10 main psychiatric categories (Maric et al. Citation2017).

Prescription patterns could differ amongst patients at hospital discharge in comparison to maintenance therapy phase of outpatients (Hasan et al. Citation2013). Yet, to the best of our knowledge, pharmacotherapy of PSD outpatients in this region has not been sufficiently evaluated. Thus, the present study aimed to investigate prescription patterns in PSD outpatients from a real-world setting, based on the data from two centres in Serbia (university psychiatric clinic and general psychiatric state hospital) covering both urban and rural part of the country, thus, increasing the likelihood of having a nationally representative study sample. We focussed on AP polypharmacy and psychotropic polypharmacy in this article by applying the concept of ‘antipsychotic polypharmacy’ defined as concurrent use of more than one AP for at least 1 month (Kreyenbuhl et al. Citation2006; Barnes and Paton Citation2011) and ‘psychotropic polypharmacy’ as the combination of AP and an different class of psychotropic drugs medication for at least 1 month (Fleischhacker and Uchida Citation2014). The main outcome of interest was to assess the rate of AP polypharmacy. The second outcome was to assess the rate of psychotropic polypharmacy – with particular focus on concomitant long term use of AP with BZDs for at least 1 month. Finally, we aimed to explore the associations of pharmacotherapy with symptoms of psychosis and with the quality of life.

Methods

Present exploratory research was conducted as a part of the larger study exploring the implementation of the psychosocial intervention DIALOG + for patients with psychotic disorders in low- and middle-income countries in South Eastern Europe (Grant agreement no. 779334). Clinicians working with PSD outpatients from two sites from Serbia were invited to participate in the study. Study participants were recruited from two outpatient clinics in Serbia, namely from university psychiatric hospital in Belgrade and special psychiatric hospital in Vrsac. Included hospitals have had well established psychiatric services and both sites have been health care institutions operated by the government and contracted with the National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF). No differences were found in prescribing patterns between two samples from two clinics, so the decision was made to group them together for the final analysis.

Patients eligibility criteria included: primary diagnosis of psychosis or related disorder (ICD-10 F20-29, i.e., PSD), age 18–65, history of at least one psychiatric hospital admission in their lifetime, capacity and will to provide informed consent and a history of attending the outpatient clinic for at least 1 month with unchanging prescription pattern prior to the inclusion. Patients were excluded if having a diagnosis of organic brain disorders, variable prescription pattern and severe cognitive deficits (thus, being unable to provide informed consent and reliable information to study instruments).

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its design was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine University of Belgrade, as well as by the professional boards of the both study sites. All participants provided written informed consent before the study and researchers completed the baseline assessment, which included socio-demographic and clinical assessment.

The 24-item Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (Overall and Gorham Citation1962) was used to assess patients’ current symptom status, whereas each symptom was rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 – not present, 7 – extremely severe). Total average scores vary from 1.00 to 7.00 with lower scores indicating less severe psychopathology. For additional information about particular symptom domains, four BPRS sub-dimensions were constructed: Disorganisation, Reality distortion, Depression and Negative symptoms (Ventura et al. Citation2000).

The brief 10-item Recovering Quality of Life (ReQoL-10) (Keetharuth et al. Citation2018), a Patient Reported Outcome Measure, was used to assess participants’ quality of life, covering seven themes: activity, hope, belonging and relationships, self-perception, well-being, autonomy, as well as one additional physical health question. The positively and negatively worded items score 0–4, where zero on the scale represents the poorest quality of life and four the highest. ReQoL-10 score up to 24 is considered as falling within the clinical range (Keetharuth et al. Citation2018). In addition to ReQol, we used one more question about physical health (problems with mobility, difficulties caring for yourself or feeling physically unwell) over the last week (0–4) and scored dichotomously (no or mild problems versus moderate–severe problems).

The data about prescribed psychotropic drugs included the generic and trade names of each drug and daily dose. Medical chart review was used to list all psychotropic medications prescribed over the 4 weeks period preceding the evaluation, either on regular basis or discontinuously (as needed). Only medication prescribed on the regular basis was included in further analyses. The use of the following drugs was recorded in the study: APs, antidepressants, mood-stabilizers, BZDs, ACM, drugs used to treat addictive disorders and non-psychotropic concomitant medication. Duration of illness was calculated as time elapsed from the first AP medication prescription.

For APs and BZDs, we added calculations to get additional information about the dose equivalents and daily doses (DD). AP drugs were classified as either first-generation – FGA (chlorpromazine or promazine, fluphenazine, haloperidol, levomepromazine, sulpiride), second-generation – SGA (clozapine, risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, ziprasidone, paliperidone) or third-generation agents - TGA (aripiprazole). The mean AP dose during the last month was calculated and transformed into chlorpromazine equivalents (Leucht et al. Citation2016). In cases when more than one AP was used, chlorpromazine equivalent dosages were summed to obtain total daily AP dose (AP DD). According to the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Guidelines, AP DD above 600 mg CPZ equivalents were considered high maintenance dose. Daily dose of more than 1000 mg/day (i.e., the maximum SPC daily dose for chlorpromazine) in chlorpromazine equivalents was considered very high dose (Royal College of Psychiatrists, Citation2014). BZD medication included all available BZDs and presented as lorazepam equivalent doses (World Health Organisation Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistic Methodology). Lorazepam 1 mg equivalent doses were calculated as follows: diazepam 5 mg; bromazepam 3 mg; clonazepam 0.5 mg; alprazolam 0.25 mg; midazolam 7.5 mg; zolpidem 5 mg (midazolam and zolpidem were considered as hypnotics, while all other were grouped into anxiolytics). The equivalent doses given above are representative of information from two resources (Sadock et al. Citation2003; Zitman and Couvée Citation2001), as per previous articles (Maric et al. Citation2017). In cases when more than one BZD were used, lorazepam equivalent doses were summed to obtain total daily BZD dose (BZD DD). According to the ATC/DDD system, the mean daily dose >2.5 mg of lorazepam equivalents (DDD) was considered high. According to the Longo and Johnson (Citation2000), alprazolam, bromazepam, lorazepam, midazolam and zolpidem were classified as short-acting BZDs, whereas clonazepam and diazepam were considered as long-acting drugs. Owing to the most of the current guidelines recommendations that maximum duration of BZD use should not exceed 2–4 weeks (WHO Programme on Substance Abuse Citation1996; Ministry of Health Singapore Citation2008; Taylor et al. Citation2018), and having in mind that Tiihonen et al. (Citation2012) found that more than 80% of all deaths occurred during treatment periods with prescriptions that included more than 28 DDD of BZD, we considered continual prescription of BZD for at least 4 weeks as long-term BZD use.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed by the SPSS version 20.0 statistical software. Descriptive statistics (socio-demographic and clinical measures) were presented using absolute and relative numbers, means, standard deviations and medians. After initial testing for data normality (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test), the between-group analyses (AP monotherapy versus AP polypharmacy; BZD yes versus BZD no) were accordingly assessed using appropriate parametric or non-parametric tests (Chi-square test, Mann–Whitney test, Student t-test for independent samples) and Pearson’s correlation for associations between the study parameters. Effect sizes were provided as appropriate, and interpreted as follows: Mann–Whitney r and phi coefficient – 0.1 small, 0.3 medium, 0.5 large; Cramer’s V – 0.06 small, 0.17 medium, 0.29 large; Hedges’s G – 0.2 small, 0.5 medium, 0.8 large. All p values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the sample

The data related to the demographics, drug prescription patterns and clinically relevant information (symptoms and quality of life) were obtained and analysed for 73 PSD outpatients from two sites from Serbia. Their main socio-demographic/clinical characteristics and quality of life indices are presented in .

Table 1. Study sample.

A slightly larger number of patients was treated with AP monotherapy (N = 40; 54.8% of the total sample), whereby the majority of them were prescribed with the SGA (33 out of 40 patients). Regarding the AP polypharmacy (N = 33, 45.2%), the combination of FGA + SGA was most frequently prescribed (19 out of 33 patients).

The mean daily AP dose was 334.4 mg of CPZ equivalents (SD 188.7; median 321.0 mg). In total, there were 8 cases with DD of 600 mg or more of CPZ equivalents (no one was prescribed with daily dose above 1000 mg of CPZ equivalents). The average daily AP dose (CPZ equivalents) was significantly higher in patients treated with AP polypharmacy in comparison to those treated with AP monotherapy (434.0 ± 169.6 mg/day and 253.3 ± 163.8 mg/day, respectively; t = 4.641, df = 71, p = 0.00; Hedges’ G = 1.1). Statistically significant difference between the polypharmacy and monotherapy patient groups was also observed in terms of diagnostic categories’ frequencies (χ2=10.204, df = 4, p = 0.04, Cramer’s V = 0.36), namely – AP polypharmacy was the most common in patients diagnosed with schizophrenia and their AP daily doses were higher (median: F20 – 362.00 mg/day; F25 – 300.00 mg/day and F29 – 218.00 mg/day; df = 2, F = 3.464, p = 0.037). AP DD positively correlated with age (r = 0.270, p = 0.021).

The total BPRS scores were significantly higher in patients treated with AP polypharmacy in comparison to AP monotherapy group (t(65)= −1.93, p = 0.05, mean difference = −0.21, 95% CI: −0.43/0.01, Hedges’s G = 0.47). However, there were neither significant differences in terms of four constructed BPRS subdomains (Disorganisation, Reality distortion, Depression and Negative symptoms), nor regarding the indicators of quality of life (ReQoL) and physical health between AP mono- and polypharmacy groups. Detailed information regarding the patterns of AP prescription in the present sample and their relation to the examined clinical parameters are presented in .

Table 2. Prescription of antipsychotic medication and relation to clinical parameters.

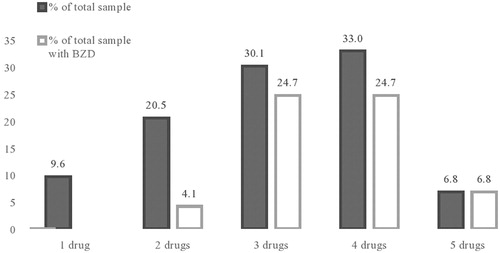

Considering the rate of psychotropic polypharmacy (see ), one third of the sample was prescribed with four psychotropic drugs (32.9%), followed by those prescribed with three (30.1%), two (20.5%) and five (6.8%) psychotropic drugs. Only 9.6% of examined patients were treated with one psychotropic drug (i.e., AP). The drugs most frequently prescribed in conjunction with APs were BZDs (60.3%), whereas the mean average daily dose (lorazepam equivalents) was 2.9 mg (SD 2.0). The prevalence of patients treated with long-acting BZDs was 27.4% in our sample, while other shorter acting BZDs were prescribed to 32.9% of participants. Out of other patients treated with psychotropic drug combinations 35.8% were prescribed with a concomitant mood-stabilizer, 25.7% with an antidepressant, and 23.3% with an anticholinergic drug. Polypharmacy positively correlated with age (r = 0.291; p = 0.012).

ACM was prescribed in 17 patients. All patients who had FGA in monotherapy (n = 2) or two FGA combined (n = 1) were prescribed with ACM, while in SGA monotherapy group ACM was prescribed to 6 out of 33 patients, and in TGA monotherapy group to 1 out of 3 patients. The average AP CPZ equivalent daily dose in patients with ACM was not significantly different in comparison to daily dose of AP in patients with no ACM (U = 383, z= −683, p = 0.495).

In comparison to patients with no BZD, patients with BZD use had significantly more psychotropic medications (median 2 and 4 psychotropic drugs, respectively; U = 246, z= −4.59, p = 0.00, r = 0.54) and more AP polypharmacy (χ2=6.030, df = 1, p = 0.01, phi coefficient = 0.29). Correlation between AP DD and BZD DD was significant (r = 0.314; p = 0.038).

In patients with BDZ use we found significantly lower ReQol scores (t(65)=1.99, p = 0.05, mean difference = 3.85, 95% CI: −0.01/7.70, Hedges’s G = 0.49) and significantly higher total BPRS scores (t(65)= −3.50, p = 0.00, mean difference= −0.37, 95% CI: −0.58/−0.16, Hedges’s G = 0.86) – indicating poorer quality of life and the presence of more severe psychopathology. Regarding the preliminary analyses of four BPRS subdomains, the patients co-prescribed with BZD showed significantly higher rates of reality distortion (median 1.1 and 0.8, respectively; U = 371, z= −2.27, p = 0.02, r = 0.3) and depression (median 2.3 and 1.8, respectively; U = 347, z= −2.48, p = 0.01, r = 0.3) than those not receiving BZD, whereas the groups did not differ in terms of negative symptom dimension and disorganisation (see ).

Table 3. Prescription of benzodiazepines and relation to clinical parameters.

Patients treated with long-acting BZDs did not differ from those treated with shorter acting BZDs in terms of quality of life (p = 0.27) or psychopathology indicators (total BPRS scores, p = 0.27).

Discussion

Regarding AP therapy, present study showed that maintenance therapy in outpatients with PSD predominantly consisted of monotherapy with SGA (45.2%), followed by AP polypharmacy based on FGA + SGA combination (25.0%). This is different in comparison to an earlier study from this area (Maric et al. Citation2011) and shows the tendency towards increased use of the SGAs. Increased availability of newer APs and changing pattern of prescriptions during the last decade could be possible explanations and, summing up, the prescribing clinicians appear to have acted rationally when selecting AP medication. Our findings have also shown that AP polypharmacy was the most common in the subgroup of patients with schizophrenia (rate of AP polypharmacy in this subgroup was 67%). No significant differences in terms of quality of life or illness duration between AP monotherapy and polypharmacy groups have been found.

Although in some European regions (Gaviria et al. Citation2015), AP polypharmacy could reach 60%, in most of the large-scale studies AP polypharmacy in schizophrenia has been 10–35% (Williams et al. Citation2012), 35% was found in US public mental health study (Covell et al. Citation2002), 20% in Korea (Kim et al. Citation2014), while 10% was evident in Germany (Weinbrenner et al. Citation2009). In Korea (Kim et al. Citation2014), where approximately 20% of patients with schizophrenia were prescribed AP polypharmacy, it was associated with a longer duration of illness, more severe positive symptoms, and poorer social functioning. In comparison to the aforementioned results, the rate of AP polypharmacy found in our sample (45.2%) could be considered relatively high.

In our sample, the highest AP DD were noticed in patients with schizophrenia and the lowest in patients with unspecified psychosis (when diagnostic subgroups with more than 10 participants were examined). In general, daily AP dose found in this study (median 321 mg of CPZ equivalents) could be considered moderate according to WFSBP recommendations, where a maintenance dosage below 600 CPZ equivalents has been recommended (Hasan et al. Citation2013). It could be also considered similar to other outpatient cohorts across the world (Leucht et al. Citation2012). In a systematic review, higher dosages of 375 mg/d CPZ equivalents did not produce additional effectiveness in maintenance therapy of schizophrenia (Bollini et al. Citation1994). In another review, 200–500 CPZ equivalents were shown to be optimal for the maintenance therapy (Barbui et al. Citation1996).

All of the currently approved APs block dopamine receptors, indicating that manipulation of dopaminergic function is fundamental to a therapeutic response in psychosis. However, D2 blockade by AP drugs is necessary but not always sufficient for adequate AP response (Howes et al. Citation2009) and this could be one of the reasons why real-world prescription practice is psychotropic polypharmacy rather than monotherapy practice. Considering psychotropic polypharmacy, our study showed that the majority of participants were prescribed with 4 psychotropic drugs (32.9%), followed by those prescribed with 3 (30.1%) and 2 drugs (20.5%). The median number of prescribed psychotropic drugs for PSD was 3 (mean 3.1 ± 1.1), which was similar (or slightly lower) in comparison to the analyses published 10 years ago (11) which were based on prescriptions at hospital discharge. The most common co-prescribed drugs with APs were BZDs, followed by mood-stabilizers, antidepressants and ACM.

BZDs were prescribed to more than 60% of patients on a continual basis (for at least 4 weeks continually), with mean daily dose which could be considered relatively high (according to the ATC/DDD system). The rate of BZD co-prescription in the present outpatient sample could be considered very high, but it is still lower in comparison to the rate of BZD prescription at hospital discharge shown by another study from our region. Although BZD prescription rate was not significantly different between diagnostic sub-groups (i.e., schizophrenia, schizo-affective disorder and unspecified psychosis), we noticed that patients with higher AP DD also had higher BZD DD. The aforementioned notion might suggest that patients with more severe and complex PSD symptoms (as indicated by higher AP DD and higher BPRS score) are receiving more BZD. However, cross-sectional design of this study was a limitation to elaborate this association further and to drive conclusions about the causality.

Therapeutic benefit of add‐on BZDs in the treatment of acute psychosis includes less extrapyramidal symptoms (Gillies et al. Citation2001) and there is also some evidence for a favourable effect of BZDs in the short-term treatment of akathisia (Lima et al. Citation2002). Nevertheless, having in mind the serious consequences of prolonged BZD use in patients with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, our data should be used as a starting point for careful consideration of BZD prescription in the region and for the implementation of strategies aiming to increase the knowledge about rational BZD use. For example, as the prescription of BZD correlated with symptom score (in particular with depression and with reality distortion BPRS dimensions), and BZD use was also associated with lower physical health in our sample, the clinicians should try to recommend more specific interventions for these particular symptom-domains and also to consider non-pharmacological interventions, instead of prolonged BZD use. If clinician decide to prescribe a BZD, it should be emphasised that that the medication is only a ‘temporary’ solution with clear agreements with regard to medication withdrawal (Anthierens et al. Citation2007).

Considering ACM medication, our findings showed continual use in 23% outpatients, mostly, but not exclusively in association with FGA medication. The rate of ACM is lower in comparison to a study from Bahrein, which found ACM in one third of patients, but their sample was mixed (hospital patients and outpatients (Al Khaja et al. Citation2012). Nevertheless, the need for continued therapy with anticholinergics, and even more with BZD is frequently not reassessed and many patients remain on them for many years. Psychiatrists may be reluctant to discontinue BZD and ACM; however, the practice should be evaluated systematically in order to help in preventing serious risks of irrational polypharmacy.

Since there were higher doses and more polypharmacy in subjects with more symptoms, it could be considered as a sign that these individuals do not respond to medication and would maybe benefit from other forms of therapies – individual or group psychosocial interventions, occupational therapy, or so.

This study has several strengths and limitations. It is the first/largest study in Serbia to explore prescription patterns in outpatients with PSD, amplified with clinically relevant information (symptoms and quality of life of the outpatients), and to involve patients from two clinical settings, which adds to the generalizability of our findings. However, the findings are based on cross-sectional design and included prescription for the last month (written in the medical records). To get more comprehensive information about the maintenance phase therapy in PSD, additional studies will be needed to reflect longer patterns of medication. Moreover, our sample consisted of the whole spectrum of non-affective psychosis cases, but due to small number of participants in some diagnostic categories, we were unable to explore the particular subgroups in details. The numbers of participants receiving ACM, antidepressants and mood-stabilizers were also small for any additional analyses; however, our findings could be used to calculate sample sizes for future trials in this field. However, present research was exploratory and future studies on this topic – based on larger samples/number of included sites are needed.

Conclusion

Prescribing trends of PSD patients may vary across countries, as many factors could contribute to pharmacological treatment patterns, including patient-level issues, provider prescribing decisions, health system culture, organisational structure, and many other similar factors.

The present study demonstrated new information regarding the prescription patterns of psychotropic drugs in outpatients with PSD in Serbia, amplified with clinically relevant information (symptoms and quality of life of the outpatients). This study also revealed distinct prescription patterns in Serbia, especially concerning AP + BZD polypharmacy and described an under-researched area for this region. For improvement of the local, as well as general clinical practice and care for patients with psychotic disorders, and for education in psychiatry, such analyses need to be done on a regular basis.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under Grant agreement No 779334. The funding was received through the ‘Global Alliance for Chronic Diseases (GACD) prevention and management of mental disorders’ (SCI-HCO-07-2017) funding call.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Al Khaja KAJ, Al-Haddad MK, Sequeira RP, Al-Offi AR. 2012. Antipsychotic and anticholinergic drug prescribing pattern in psychiatry: extent of evidence-based practice in Bahrain. PP. 03(04):409–416. doi:10.4236/pp.2012.34055

- Anthierens S, Habraken H, Petrovic M, Christiaens T. 2007. The lesser evil? Initiating a benzodiazepine prescription in general practice: a qualitetive study on GPs’ perspectives. Scand J Prim Health Care. 25(4):214–219. doi:10.1080/02813430701726335

- Barbui C, Saraceno B, Liberati A, Garattini S. 1996. Low-dose neuroleptic therapy and relapse in schizophrenia: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur Psychiatry. 11(6):306–313. doi:10.1016/S0924-9338(96)89899-3

- Barnes TR, Paton C. 2011. Antipsychotic polypharmacy in schizophrenia: benefits and risks. CNS Drugs. 25(5):383–399. doi:10.2165/11587810-000000000-00000

- Bollini P, Pampallona S, Orza MJ, Adams ME, Chalmers TC. 1994. Antipsychotic drugs: is more worse? A meta-analysis of the published randomized control trials. Psychol Med. 24(2):307–316. doi:10.1017/S003329170002729X

- Cetin M. 2014. A serious risk: excessive and inappropriate antipsychotic prescribing. Klinik Psikofarmakoloji Bulteni. 24(1):1–4. doi:10.5455/bcp.20140314014626

- Covell NH, Jackson CT, Evans AC, Essock SM. 2002. Antipsychotic prescribing practices in Connecticut's public mental health system: rates of changing medications and prescribing styles. Schizophr Bull. 28(1):17–29. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006920

- Fleischhacker WW, Uchida H. 2014. Critical review of antipsychotic polypharmacy in the treatment of schizophrenia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 17(7):1083–1093. doi:10.1017/S1461145712000399

- Fontanella CA, Campo JV, Phillips GS, Hiance-Steelesmith DL, Sweeney HA, Tam K, Lehrer D, Klein R, Hurst M. 2016. Benzodiazepine use and risk of mortality among patients with schizophrenia: a retrospective longitudinal study. J Clin Psychiatry. 77(05):661–667. doi:10.4088/JCP.15m10271

- Gaviria AM, Franco JG, Aguado V, Rico G, Labad J, De Pablo J, Vilella E. 2015. A non-interventional naturalistic study of the prescription patterns of antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia from the Spanish province of Tarragona. PLoS One. 10(10):e0139403. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0139403

- Gillies D, Beck A, McCloud A. 2001. Benzodiazepines alone or in combination with antipsychotic drugs for acute psychosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4:CD003079.

- Hasan A, Falkai P, Wobrock T, Lieberman J, Glenthoj B, Gattaz WF, Thibaut F, Möller H-J, WFSBP Task force on Treatment Guidelines for Schizophrenia. 2013. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Guidelines for Biological Treatment of Schizophrenia, Part 2: Update 2012 on the long-term treatment of schizophrenia and management of antipsychotic-induced side effects. World J Biol Psychiatry. 14(1):2–44. doi:10.3109/15622975.2012.739708

- Howes O, Egerton A, Allan V, McGuire P, Stokes P, Kapur S. 2009. Mechanisms underlying psychosis and antipsychotic treatment response in schizophrenia: insights from PET and SPECT imaging. Curr Pharm Des. 15(22):2550–2559. doi:10.2174/138161209788957528

- Keetharuth AD, Brazier J, Connell J, Bjorner JB, Carlton J, Taylor Buck E, Ricketts T, McKendrick K, Browne J, Croudace T. 2018. Recovering Quality of Life (ReQoL): a new generic self-reported outcome measure for use with people experiencing mental health difficulties. Br J Psychiatry. 212(1):42–49. doi:10.1192/bjp.2017.10

- Kim HY, Lee HW, Jung SH, Kang MH, Bae JN, Lee JS, Kim CE. 2014. Prescription patterns for patients with schizophrenia in Korea: a focus on antipsychotic polypharmacy. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 12(2):128–136. doi:10.9758/cpn.2014.12.2.128

- Kreyenbuhl J, Valenstein M, McCarthy JF, Ganoczy D, Blow FC. 2006. Long-term combination antipsychotic treatment in VA patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 84(1):90–99. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2006.02.023

- Lečić-Tosevski D (Ed.). 2013. Nacionalni vodič dobre kliničke prakse za dijagnostikovanje i lečenje shizofrenije. Republička stručna komisija za izradu i implementaciju vodiča u kliničkoj praksi. Beograd: Ministarstvo zdravlja Republike Srbije, Serbian).

- Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, McGlashan TH, Miller AL, Perkins DO, Askland K. 2004. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. Am J Psychiatry. 161(2 Suppl):1–56.

- Leucht S, Heres S, Kissling W, Davis JM. 2012. Evidence-based pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia. In: Stein D, Lerer B, Stahl SM, editors. Essential evidence-based psychopharmacology. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; p. 18–38.

- Leucht S, Samara M, Heres S, Davis JM. 2016. Dose equivalents for antipsychotic drugs: the DDD method. SCHBUL. 42(suppl 1):S90–S94. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbv167

- Lima AR, Soares-Weiser K, Bacaltchuk J, Barnes TR. 2002. Benzodiazepines for neuroleptic-induced acute akathisia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1:CD001950.

- Longo LP, Johnson B. 2000. Addiction: part I. Benzodiazepines – side effects, abuse risk and alternatives. Am Fam Physician. 61(7):2121–2128.

- Maric NP, Latas M, Andric Petrovic S, Soldatovic I, Arsova S, Crnkovic D, Gugleta D, Ivezic A, Janjic V, Karlovic D. 2017. Prescribing practices in Southeastern Europe – focus on benzodiazepine prescription at discharge from nine university psychiatric hospitals. Psychiatry Res. 258:59–65. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2017.09.059

- Maric NP, Pavlovic Z, Jasovic-Gasic M. 2011. Changes in antipsychotic prescription practice at University Hospital in Belgrade, Serbia: 2009 vs. 2004. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 123(6):495–495. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01690.x

- Ministry of Health Singapore. 2008. MOH Clinical Practice Guidelines 2/2008. Prescribing of benzodiazepines. https://www.moh.gov.sg/docs/librariesprovider4/guidelines/cpg_prescribing-of-benzodiazepines.pdf

- Overall JE, Gorham DR. 1962. The brief psychiatric rating scale. Psychol Rep. 10(3):799–812. doi:10.2466/pr0.1962.10.3.799

- Royal College of Psychiatrists. 2014. Consensus statement on high-dose antipsychotic medication. London: Royal College of Psychiatrists; p. 1–53.

- Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Kaplan HI. 2003. Kaplan & Sadocks’ synopsis of Psychiatry: behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Sun FF, Stock EM, Copeland LA, Zeber JE, Ahmedani BK, Morissette SB. 2014. Polypharmacy with antipsychotic drugs in patients with schizophrenia: trends in multiple health care systems. Am J Heal Pharm. 71(9):728–738. doi:10.2146/ajhp130471

- Taylor D, Barnes TRE, Young AH. 2018. The Maudsley prescribing guidelines in psychiatry. 13th ed. Newark: John Wiley & Sons.

- Tiihonen J, Suokas JT, Suvisaari JM, Haukka J, Korhonen P. 2012. Polypharmacy with antipsychotics, antidepressants, or benzodiazepines and mortality in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 69(5):476–483. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1532

- Vares M, Saetre P, Stralin P, Levander S, Lindström E, Jönsson EG. 2011. Concomitant medication of psychoses in a lifetime perspective. Hum Psychopharmacol Clin Exp. 26(4–5):322–331. doi:10.1002/hup.1209

- Ventura J, Nuechterlein KH, Subotnik KL, Gutkind D, Gilbert EA. 2000. Symptom dimensions in recent-onset schizophrenia and mania: a principal components analysis of the 24-item Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychiatry Res. 97(2–3):129–135. doi:10.1016/S0165-1781(00)00228-6

- Vinogradov S, Fisher M, Warm H, Holland C, Kirshner MA, Pollock BG. 2009. The cognitive cost of anticholinergic burden: decreased response to cognitive training in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 166(9):1055–1062. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09010017

- Weinbrenner S, Assion HJ, Stargardt T, Busse R, Juckel G, Gericke CA. 2009. Drug prescription patterns in schizophrenia outpatients: analysis of data from a German health insurance fund. Pharmacopsychiatry. 42(2):66–71. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1103293

- WHO Programme on Substance Abuse. 1996. Rational use of benzodiazepines. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/65947

- Williams EO, Stock EM, Zeber JE, Copeland LA, Palumbo FB, Stuart M, Miller NA. 2012. Payer types associated with antipsychotic polypharmacy in an ambulatory care setting. J Pharm Heal Serv Res. 3(3):149–155. doi:10.1111/j.1759-8893.2012.00083.x

- Winkler P, Krupchanka D, Roberts T, Kondratova L, Machů V, Höschl C, Sartorius N, Van Voren R, Aizberg O, Bitter I, et al. 2017. A blind spot on the global mental health map: a scoping review of 25 years’ development of mental health care for people with severe mental illnesses in central and eastern Europe. Lancet Psychiatry. 4(8):634–642. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30135-9

- Zink M, Englisch S, Meyer-Lindenberg A. 2010. Polypharmacy in schizophrenia. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 23(2):103–111. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283366427

- Zitman FG, Couvée JE. 2001. Chronic benzodiazepine use in general practice patients with depression: an evaluation of controlled treatment and taper-off: report on behalf of the Dutch Chronic Benzodiazepine Working Group . Br J Psychiatry. 178:317–324. doi:10.1192/bjp.178.4.317