Abstract

Objective

To identify sick leave days (SLD) predictors after starting antidepressant (AD) treatment in patients affected by major depressive disorder (MDD), managed by general practitioners, with a focus on different AD therapeutic approaches.

Methods

Retrospective study on German IQVIA® Disease Analyser database. 19–64 year old MDD patients initiating AD treatment between July-2016 and June-2018 were grouped by therapeutic approach (AD monotherapy versus combination/switch/add-on). Data were analysed descriptively by AD therapeutic approach, while a zero-inflated Poisson (ZIP) multiple regression model was run to evaluate SLD predictors.

Results

8,891 patients met inclusion criteria (monotherapy: 66%; combination/switch/add-on: 34%). All covariates had an influence on SLD after AD treatment initiation. Focussing on variables that physicians may more easily intervene to improve outcomes, it was found that the expected SLD number of combination/switch/add-on patients was 1.6 times that of monotherapy patients, and the expected SLD number of patients diagnosed with MDD before the decision to start AD treatment was 1.2 times that of patients not diagnosed with MDD.

Conclusions

A patient tailored approach in the selection of AD treatment at the time of MDD diagnosis may improve functional recovery and help to reduce the socio-economic burden of the disease.

Few studies previously investigated the effect of antidepressant treatment approaches on sick leave days in major depressive disorder.

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study evaluating the effect of different antidepressant treatment approaches on sick leave days in major depressive disorder in German patients.

Patients receiving antidepressant monotherapy treatment seemed to lose fewer working days than patients receiving antidepressants combination/switch/add-on therapy, both before and after starting treatment, even if differences were more pronounced after treatment has started.

The use of antidepressant monotherapy or combination/switch/add-on therapy was the strongest predictor of sick leave days after starting antidepressant treatment: the expected number of sick leave days for the combination/switch/add-on group was 1.6 times that of the monotherapy group.

Among factors associated with increased sick leave days, antidepressant therapeutic approach and the promptness of starting the antidepressant treatment when major depressive disorder is diagnosed, are those on which physicians may more easily intervene to improve outcomes.

Findings from the present study suggest that a patient tailored approach may improve functional recovery and help reducing the socio-economic burden of the disease.

KEY POINTS

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a persistent, debilitating mental disorder which interferes considerably with patients’ functioning at several levels (emotional, intellectual and social), and impairs overall quality of life (Hemels et al. Citation2004b; Hofmann et al. Citation2017). MDD is one of the most common types of mental disorder among adults in Western countries (Kessler and Bromet Citation2013). The German Health Interview and Examination Survey for adults (DEGS1-MH) found a 12-month prevalence of 6.0% for MDD, with lifetime prevalence being considerably higher (Krauth et al. Citation2014).

MDD also places a substantial economic burden on patients, their families and society (Hemels et al. Citation2004b). In fact, its high prevalence has resulted in increased primary and secondary healthcare resources utilisation (HRUs), sick leave and disability pensions, which have, in turn, contributed to continuously rising healthcare costs since the 1990s (Hemels et al. Citation2004b; Roca et al. Citation2009; Gili et al. Citation2013). In particular, due to the early age of onset and its recurrent and chronic course, MDD has a substantial impact on work productivity, with a significant component of disease burden found to be absenteeism from work (Stewart et al. Citation2003; Hemels et al. Citation2004a). Further, from an individual point of view, work disability can hugely affect quality of life, as employment is often an important component of a person’s life (Nieuwenhuijsen et al., Citation2008). A study conducted in the UK revealed that being able to work was viewed as the sixth most important aspect of quality of life by healthy people, whereas health-impaired individuals ranked work ability their third most important aspect (Bowling Citation1995).

Bültmann et al. examined the impact of depressive symptoms on long-term sickness absence in a representative sample of the Danish workforce. After having adjusted for demographic, health-related and lifestyle factors, they found that both men and women with severe depressive symptoms were at increased risk of long-term sickness absence (Bültmann et al. Citation2006). In 2012, in Germany, the average work disability period due to a single depressive episode was 46.4 days, which increased to 64.6 days for recurrent episodes (Krauth et al. Citation2014). In recent years, the contribution of mental disorders to the costs of permanent disability pensions in Germany has tripled; more than half of these costs are attributable to depression, anxiety and related neurotic disorders. From this perspective, the impact of MDD on work productivity is an issue of keen interest to insurers and governments (Wedegärtner et al. Citation2007). Depressive disorders can be accurately diagnosed and effectively treated (Nieuwenhuijsen et al., 2008). Current German practice guidelines for the treatment of MDD recommend psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, or a combination of both (DGPPN et al. Citation2009). Pharmacologic treatments include tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAO-inhibitors), serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitors (SARIs), and selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) (Hansen et al. Citation2005; Nieuwenhuijsen et al. 2008). A recent meta-analysis by Cipriani et al. found that all antidepressants (ADs) were more efficacious than placebo in adults with MDD, with small differences observed between AD molecules (Cipriani et al. Citation2018). However, only few studies have examined the effect of treatment in terms of function, work ability or return to work in depressed patients (Skoglund et al. Citation2019). Although it has been demonstrated that ADs and psychotherapy are effective in reducing depressive and anxiety symptoms, there is little evidence that this beneficial effect might result in an earlier return to work (Nieuwenhuijsen et al. 2008; Skoglund et al. Citation2019). In particular, the course of sick leave in relation to AD use has been seldom investigated. Studies conducted in the US showed that sick leave increases prior to AD treatment initiation and decreases after initiation (Claxton et al. Citation1999; Birnbaum et al. Citation2000). A 2013 study by Gasse et al. aimed at describing predictors of sick leave in patients newly initiated on ADs in Denmark, found that among first-line ADs, only TCAs were associated with a slightly lower risk of sick leave (Gasse et al. Citation2013).

The present study, which was exploratory in nature, investigated whether starting different AD therapeutic approaches (i.e., AD monotherapy versus AD combination, switch or add-on) might have different impacts on sick leave days, in a cohort of MDD patients managed by general practitioners (GPs) in Germany. The main study objectives were to describe MDD patients managed by GPs with different AD therapeutic approaches, to explore the sick leave days trend before and after starting AD treatment, according to different AD therapeutic approaches, and to identify predictors of sick leave days after starting AD treatment.

Material and methods

Description of the data source

This was a retrospective observational cohort study using data from electronic medical records (EMRs), captured by the German IQVIA® Disease Analyser (DA) database. The German IQVIA® DA database provides routine care information from physician consultations, including diagnoses according to the International Classification of Diseases 10th revision (ICD-10), drug prescriptions, as well as medical and demographic data obtained from the computer systems of a representative sample of practices throughout Germany (Becher et al. Citation2009; Rathmann et al. Citation2018). Patient data are entered directly by GPs, internists, and other medical specialties, such as cardiologists, diabetologists, gynaecologists, orthopaedics, paediatricians, psychiatrists, neurologists and urologists. The German Association for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy (DGPPN) research project on mental healthcare utilisation in Germany found that non-psychiatric disciplines, like general practice, were the most frequently used providers of outpatient mental health care (Gaebel et al. Citation2012). In addition, due to the increasing number of depressed patients and the development of new antidepressant drugs, primary care physicians today play an important role in the treatment of these conditions (Jeschke et al. Citation2012; Freytag et al. Citation2017). Based on these reasons, the present study was focussed on primary care, analysing data from approximately 5 million patient records collected from across more than 1,500 GPs. The validity and representativeness of the data in the German IQVIA® DA database has been confirmed by an external comparison with state health insurance (SHI) data (Ehlken et al. Citation2019). German law allows the use of anonymous EMRs for research purposes under certain conditions. According to this legislation, it is not necessary to obtain informed consent from patients or approval from a Ethics Committee for this type of retrospective observational study that contains no directly identifiable data. Because patients were only queried as aggregates and no protected health information was available for queries, no approval from an institutional review board was required for the use of this database or the completion of this study (Tanislav et al. Citation2021).

Study design

All patients with at least one prescription of AD (defined as a drug belonging to the N06A Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical class) during the period 01 July 2016 − 30 June 2018 (‘selection period’) were initially selected. The date of the first AD prescription was defined as the ‘Index Date’. A two-year period, starting 12 months prior to (‘baseline’) and lasting up to 12 months after (‘follow-up’) the Index Date was observed (‘study period’). To be included in the study, patients had to be aged between 19 and 64 years at the Index Date, have at least one recorded diagnosis of MDD (ICD-10 codes: F32.xx or F33.xx), and have available data during the study period. Patients who had at least one AD prescription during baseline, patients who did not take AD on a regular basis (i.e., those who did not have any additional AD prescription during follow-up), and those who had at least one AD prescription-related diagnosis different from MDD during follow-up, were excluded from the study.

Study patients were classified into two different groups based on AD therapeutic approach at Index Date and during follow-up. Patients who had prescriptions of a single AD both at Index Date and during follow-up were included in the AD monotherapy group (AD MONO); patients who had prescriptions of more than one AD at Index Date, as well as patients who had prescriptions of a single AD at Index Date, but received prescriptions of different AD during follow-up, were included in the AD combination/switch/add-on group (AD COMBI-SW-ADD).

The following information was extracted from the database for the final study cohort: comorbidities of interest for the present analysis scope, recordings of MDD diagnosis during baseline, demographic characteristics at the Index Date, AD prescriptions during follow-up, MDD characteristics (i.e., severity and recurrence of episodes), sick leave registrations for any cause during baseline and follow-up. Comorbidities of interest included both psychiatric (anxiety, obsessive compulsive disorder, bipolar I disorder, substance abuse disorder, schizophrenia, eating disorder, sleep disorder, headache/migraine, neuropathic pain) and non-psychiatric (obesity, hyperlipidaemia, diabetes mellitus, muscular skeletal disease, hypertension, coronary artery disease, and cerebrovascular disease) conditions. Annexe I of the Supplementary Materials shows the ICD-10 codes used to define the above comorbidities. Information on severity and recurrence of MDD episodes was derived from ICD-10 codes used by physicians to register the MDD diagnosis closest to the Index Date. Annexe II of the Supplementary Materials shows the ICD-10 codes used to define MDD severity and recurrence.

Outcomes definitions and statistical analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics, as well as the number of sick leave days reported during the 12-month baseline and follow-up periods were stratified by AD therapeutic approach. Information on sick leave, including both the starting and the ending date of each episode, was directly recorded by GPs. For each patient, the duration of each sick leave episode was summed to get the total number of sick leave days experienced during the study period. A graphical representation of average number (mean and standard deviation) of sick leave days was provided per quarter of year (‘quarter’) and differences between groups were investigated by non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. A multiple zero-inflated Poisson regression model (ZIP model) was run to investigate which variables might be associated with the number of sick leave days during follow-up, i.e., once AD treatment has been initiated. Previous studies have used ZIP regression to model days of sick leave (Goetzel et al. Citation2010; Gordeev et al. Citation2014; Asay et al. Citation2016; Merola et al. Citation2018). ZIP regression is used to model count data with an excess of zero counts which determine a right-skewed distribution, such as the one observed for the variable representing the number of sick leave days in this study (33.2% of patients did not make any sick leave request during follow-up). Assuming that the excess zeros are generated by a separate process from the count values, they can be modelled independently. ZIP models assume that, for some of the subjects, zeros occur by a Poisson process, but others were not even eligible to have the event occurring. As a consequence, the ZIP model fits, simultaneously, two separate regression models: a logit model for predicting the probability of being a certain-zero (in this specific case, for instance, a patient might not be part of the workforce or might not be eligible to sick leave compensation), and a Poisson model determining the count of the response for individuals who are eligible for a non-zero count (e.g., patients who are part of the workforce and eligible for sick leave compensation). The use of such a model allowed for the possibility that some patients might not be part of the workforce. Indeed, while the individuals selected for this study could be considered as being of working age at Index Date, it was not possible to track whether they were actually working. Annexe III of Supplementary Materials shows the description of criteria determining the choice of model covariates. Finally, because around half of the patients had an unspecified MDD severity, a sensitivity analysis was run on the subgroup of patients with a specified MDD severity. All the analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 and p-values lower than .05 were considered as statistically significant.

Results

Study population

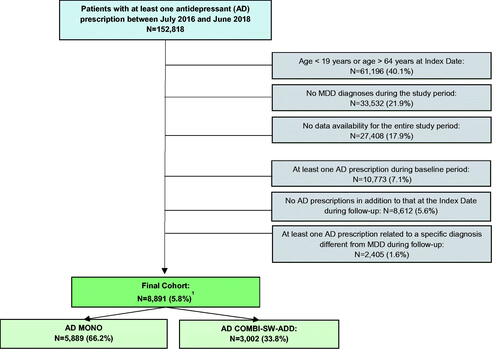

Data from 152,818 patients with at least one prescription of AD during the selection period were captured from the German IQVIA® DA database. A final cohort of 8,891 patients was defined according to eligibility criteria. AD MONO patients numbered 5,889 (66.2%), while AD COMBI-SW-ADD patients numbered 3,002 (33.8%) (). Among AD COMBI-SW-ADD patients, only 317 (10.6%) had prescriptions of more than one AD at the Index Date (data not shown).

Figure 1. Attrition of study sample. AD: Antidepressant; MDD: Major Depressive Disorder; AD MONO: patients who had prescriptions of a single AD both at Index Date and during follow-up; AD COMBI-SW-ADD: patients who had prescription of more than one AD at Index Date, and patients who had prescriptions of a single AD at Index Date, but received prescriptions of different AD during follow-up. 1One patient was excluded due to missing information about sex.

Characteristics of study patients

No significant differences in demographic characteristics were identified between the AD MONO and AD COMBI-SW-ADD groups. Overall, mean age was 47 years and females accounted for 62.8% of the study population. The most frequently observed baseline psychiatric comorbidities were anxiety, headache/migraine, neuropathic pain and substance abuse disorder; for baseline non-psychiatric comorbidities, these were muscular skeletal disease and hypertension. No particular trends were observed when comparing proportions of patients affected with each psychiatric condition between two groups. All non-psychiatric comorbidities were more frequently reported in the AD MONO group, except for muscular skeletal and coronary artery diseases. Focussing on MDD-related variables, about one third of all patients had an MDD diagnosis during baseline. A lower proportion of patients with moderate-to-severe MDD was reported in the AD MONO group, while no differences were observed in terms of recurrence, with a single MDD episode occurring in almost 90% of individuals from each group ().

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of major depressive disorder (MDD) patients by antidepressant (AD) therapeutic approach.

Sick leave days throughout study period

The distribution of sick leave days showed a higher proportion of patients in the AD MONO group without sick leave and a lower proportion of patients with more than 30 days of sick leave, compared to the AD COMBI-SW-ADD group, both during baseline and follow-up. However, differences between the groups became more pronounced during follow-up. Further, the comparison between distribution of baseline and follow-up sick leave days within AD therapeutic approach group showed stronger differences for the AD COMBI-SW-ADD group ().

Table 2. Baseline and follow-up distribution of sick leave days stratified by antidepressant (AD) therapeutic approach.

shows the trends of sick leave days throughout baseline and follow-up (by quarter) by AD therapeutic approach group. The mean number of sick leave days was relatively stable from baseline quarter I to baseline quarter III, while it increased during baseline quarter IV (i.e., prior to AD treatment initiation), in both groups. Once AD treatment was initiated (i.e., at the beginning of follow-up quarter I), the mean number of sick leave days increased, reaching a peak in follow-up quarter I that progressively decreased from follow-up quarter II onwards, in both groups. However, the mean number of sick leave days during the final follow-up quarter (IV) was higher than that observed during baseline quarter I for both groups, although the differences observed between the start and end of the study period were much smaller for the AD MONO group. In fact, the increase in mean sick leave days from baseline quarter I to follow-up quarter IV was around 33% for the AD MONO group and 130% for the AD COMBI-SW-ADD group. Overall, a statistically significant higher mean number of sick leave days was observed for the AD COMBI-SW-ADD group, throughout the entire study period (). Accordingly, the mean number of sick leave days during the baseline period was 27.9 days for the AD MONO group and 33.3 days for the AD COMBI-SW-ADD group, compared to 43.9 days and 76.3 days, respectively, during the follow-up period (data not shown).

Figure 2. Sick leave days (mean and standard deviation [SD]) throughout baseline and follow-up study quarters by antidepressant (AD) therapeutic approach. AD: Antidepressant; AD MONO: patients who had prescriptions of a single AD both at Index Date and during follow-up; AD COMBI-SW-ADD: patients who had prescription of more than one AD at Index Date, and patients who had prescriptions of a single AD at Index Date, but received prescriptions of different AD during follow-up; SD: standard deviation. *p-value from non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test for differences between groups is statistically significant.

![Figure 2. Sick leave days (mean and standard deviation [SD]) throughout baseline and follow-up study quarters by antidepressant (AD) therapeutic approach. AD: Antidepressant; AD MONO: patients who had prescriptions of a single AD both at Index Date and during follow-up; AD COMBI-SW-ADD: patients who had prescription of more than one AD at Index Date, and patients who had prescriptions of a single AD at Index Date, but received prescriptions of different AD during follow-up; SD: standard deviation. *p-value from non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test for differences between groups is statistically significant.](/cms/asset/9343956e-5a1c-4fc0-b23b-79c3bb84b46c/ijpc_a_1972120_f0002_b.jpg)

Predictors of sick leave days during follow-up

All the variables included in the Poisson model component were significantly associated with sick leave days. However, different magnitudes of association were observed. The variable that appeared to most strongly impact sick leave days after starting AD treatment was AD therapeutic approach, followed by MDD severity and patient age. Indeed, the expected number of sick leave days during follow-up for the AD COMBI-SW-ADD group was around 1.6 times higher than that of the AD MONO group. Further, baseline substance abuse disorder, neuropathic pain and cerebrovascular disease, as well as the presence of MDD diagnosis before initiation of AD treatment, were associated with a higher expected number of sick leave days during follow-up (magnitude of effect: between 1.2 and 1.3). The association with the other variables included in the model, even if statistically significant, could be considered as negligible due to the very small magnitude of effects () . Results from the logit component of the ZIP model showed that older patients, females, and those affected by baseline coronary artery disease and/or cerebrovascular disease had a statistically significant higher likelihood of being in the ‘certain-zero’ group (). Annexe IV of the Supplementary Materials shows results from the sensitivity analysis. The ZIP model run on the subgroup of patients with a specified level of MDD severity confirmed most of the findings from the model run on the total cohort, including those on AD therapeutic approach.

Table 3. Results from the Poisson component of the zero-inflated Poisson (ZIP) model predicting the number of sick leave days during follow-up.

Table 4. Results from the logit component of the zero-inflated Poisson (ZIP) model predicting the membership to the ‘Certain Zero’ sick leave days group.

Discussion

The aim of the study was to describe patients affected by MDD and managed by GPs with different AD therapeutic approaches, either AD monotherapy or AD combination, switch or add-on; to explore the sick leave days trend before and after starting AD treatment according to the different AD therapeutic approaches; and to identify predictors of sick leave days after starting AD treatment.

AD monotherapy was the most common treatment initiated in patients with MDD diagnosis observed in the study. This approach appeared to be compliant with German DGPPN guidelines (DGPPN et al. 2009), which only recommend the simultaneous use of two ADs in cases of treatment resistance (Wiegand et al. Citation2016). This is different from what is suggested by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) (American Psychiatric Association Citation2010) and the British National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health Citation2010), which consider augmentation with a second AD an adequate strategy (Wiegand et al. Citation2016). A study by Wiegand et al. using German health insurance data to assess treatment patterns in MDD, reported that only approximately 9% of patients managed by GPs were treated with two ADs simultaneously (Wiegand et al. Citation2016). The present study found only 317 (3.6%) patients which had been prescribed more than one AD at Index Date. However, considering that the AD-COMBI-SW-ADD group included patients who may have received an add-on AD drug during follow-up, it is expected that the actual percentage of patients simultaneously treated with different ADs may be higher than 3.6%. Furthermore, the 33.8% of AD COMBI-SW-ADD patients described in the present study is consistent with data from a French trial conducted on a sample of one million patients (Fagot et al. Citation2016). Age and sex distributions in the present study are in line with the 2017 World Health Organisation (WHO) report on ‘Depression and other common mental disorders’, which showed a higher prevalence in women (62.8% of the total cohort) and one third of patients aged between 55 and 64 years (World Health Organization Citation2017). While AD MONO patients were more frequently affected by non-psychiatric comorbidities, a higher proportion of patients with baseline anxiety and moderate-to-severe MDD was observed in the AD COMBI-SW-ADD group. The proportion of patients with psychiatric comorbidities described in the present study was generally low. In particular, the percentage of patients with anxiety was much lower when compared to the Freytag et al. study (7.3% versus 26.4%) (Citation2017). However, it should be noted that patients who were receiving AD for other diagnoses were excluded from the present study, which may have led to the exclusion of some patients with comorbid psychiatric disorders. That said, the distribution of patients by MDD severity, based on ICD-10 codes, was quite similar to the one observed by Freytag et al. (Citation2017). In particular, proportions of patients with mild and severe MDD were comparable, while a higher proportion of patients with moderate MDD was observed in the present study (Freytag et al. Citation2017).

Results from the analysis of sick leave revealed a similar trend for both groups, although a higher mean number of sick leave days was observed for the AD COMBI-SW-ADD group throughout the study period. Following peaks in the first quarter of follow-up, decreases in sick leave days were observed, even though the numbers did not return to the values of the first baseline quarter, and particularly for the AD COMBI-SW-ADD group. Furthermore, differences in number of sick leave days between the start and the end of the study period were much smaller in the AD MONO group compared to the AD COMBI-SW-ADD group. Similar trends were observed in previous studies, suggesting that the initiation of AD treatment results in a reduction of sick leave days (Claxton et al. Citation1999; Birnbaum et al. Citation2000; Gasse et al. Citation2013). Our data showed that the populations included in the two groups (AD-MONO and AD COMBI-SW-ADD), had similar characteristics at baseline. Nevertheless, patients in the latter group received a combination, an add-on or switched to a different AD during the follow-up period. In the absence of other data that could help to explain this therapeutic approach, we could argue that these patients received an ineffective or inappropriate treatment at initiation. This may have necessitated subsequent treatment adjustments, which, in turn, led to potential delays in response, and an increase in sick leave days. In light of the above results, it should be underlined the importance of selecting AD treatments based on specific patients’ needs and clinical characteristics.

Results from the descriptive analysis of sick leave days trends were confirmed by the multiple regression ZIP model, which showed that the expected number of sick leave days during follow-up was around 1.6 times higher in AD COMBI-SW-ADD patients compared to AD MONO patients. AD therapeutic approach was the predictor with the highest magnitude of association. Previous studies have attempted to estimate the effect of AD treatments on sick leave, however, they mainly focussed on AD classes or molecules (Winkler et al. Citation2007; Gasse et al. Citation2013; Wang et al. Citation2015), rather than AD treatment approach. A systematic review by Lee confirmed that AD treatment improves workplace outcomes, including reductions in sick leave among adult patients with MDD (Lee et al. Citation2018). Consistent with our findings, the study by Dewa et al. described that as MDD management became more complex (i.e., switched medication, more than one prescription, two prescriptions of different AD), the likelihood of return to work reduced (Dewa et al. Citation2003). Better outcomes associated with the AD MONO approach suggested by our findings were also observed in several studies, in which the non-superiority of switching AD classes over continuation of ongoing AD treatment was demonstrated (Ruhé et al. Citation2006; Rush et al., Citation2006; Bschor and Baethge Citation2010; Romera et al. Citation2012; Schosser et al. Citation2012; Bschor et al. Citation2018).

Results from the ZIP model showed that an older age and more severe MDD were predictive of a higher number of sick leave days. In line with our findings, pooled relative risks (RRs) calculated by Ervasti et al. showed that older age and a higher MDD severity were associated with slower returns to work after an episode of depression (Ervasti et al. Citation2017). The presence of most of the psychiatric and non-psychiatric comorbidities evaluated by the ZIP model resulted in a higher expected number of sick leave days, consistent with the Ervasti findings (Ervasti et al. Citation2017). Interestingly, among factors affecting sick leave, the presence of MDD diagnosis before starting AD treatment was also found to be determinant. This result seems to suggest that promptness of AD treatment initiation might have a positive effect on patients’ working lives. Unfortunately, no previous studies evaluating this aspect were found.

Findings from our model which showed a decreased number of sick leave days for patients with baseline anxiety and headache/migraine, as well as for patients with a recurrent MDD episode, are somewhat unexpected. Despite a previous finding about a favourable outcome in terms of sick leave for patients affected by anxiety (Gasse et al. Citation2013), our result might be an artefact and should also be interpreted with caution due to the very small magnitude of the association found (i.e., patients with baseline anxiety had an expected number of sick leave days 0.96 times that of patients without baseline anxiety). Similar conclusions might be drawn with regards to the slightly decreased number of sick leave days observed for patients with baseline headache/migraine.

Recurrent MDD was found to be associated with a lower number of sick leave days during follow-up. Even if this result is contradictory with previous findings (Ebrahim et al. Citation2013; Ervasti et al. Citation2017; Lee et al. Citation2018), it was hypothesised that recurrence of MDD might make patients more self-aware, and thus more prepared to manage their condition, leading to better outcomes in terms of sick leave days.

This study was based on a large population from a primary-care setting, with each patient having been observed for a two-year period. The data source used for this study is considered representative of the primary-care setting in Germany and is widely used for pharmacoepidemiologic research (Stang et al. Citation2007; Becher et al. Citation2009; Rathmann et al. Citation2018; Ehlken et al. Citation2019). However, the study had some limitations related to the data source and analytical approaches which are typical of real-world evidence studies.

Sick leave requests recorded in the German IQVIA DA® database did not report the underlying reason for the request. Therefore, it is not possible to know whether absence from work was specifically due to MDD or not, however, the implementation of a multivariate model including comorbidities among covariates, should have mitigated this limitation. In addition, as depression is associated with elevated risk of onset, persistence, and severity of a wide range of physical disorders (Kessler and Bromet Citation2013), it is believed that investigation of sick leave predictors in MDD patients should be considered of interest regardless of the specific condition which has caused the request. Furthermore, the stigma perceived by patients suffering from depression, might affect their communication with physicians. Indeed, patients may report a cause different from depression as the reason for their request of sick leave. This may lead to an underestimation of the influence of depression on a patient’s working life. From this perspective, it is believed that investigation about the real causes underlying sick leave should be a further aspect considered, in order to improve the quality of care of patients with mental health problems.

In the German IQVIA® DA database, treatment prescriptions are not always linked to a specific diagnosis. The strategy to mitigate this limitation was to include patients with at least one MDD diagnosis during the study period, while excluding patients who had at least one AD prescription with a recorded diagnosis different from MDD during the follow-up period (i.e., patients receiving AD to treat conditions other than MDD).

In the German IQVIA® DA database it is not possible to identify employed populations. Therefore, it was decided to run the multiple ZIP regression model, to account for the probability that patients were not part of the workforce. Results from the logit part of the ZIP model showed a lower probability of being part of the workforce for women, older people, and those affected by particularly disabling conditions, which reassured that the adoption of this model succeeded in mitigating this limitation.

It should be also noted that severity of MDD was derived from ICD-10 codes recorded by physicians. The increasing trend observed in the expected number of sick leave days according to MDD severity, which is also consistent with previous studies (Ervasti et al. Citation2017), gives us confidence that MDD severity based on ICD-10 codes captured the accurate extent of the condition in the study population. Further, the German IQVIA® DA database does not allow for tracking of psychotherapy, which, instead, is recommended by German practice guidelines as a monotherapy or in combination with drugs (DGPPN et al. 2009). However, it should be noted that, as the focus of the present study was the pharmacological approach, the exclusion of patients potentially receiving psychotherapy as a monotherapy did not affect results’ interpretation. On the other hand, considering the similarity of patients’ characteristics in the different AD therapeutic approach groups, there are no reasons that could make argue that psychotherapy prescription habits of GPs might differ between the two groups of patients. Finally, it is worth mentioning the possibility that there were still underlying patient characteristics or behaviours that we were unable to track or control for, which might have influenced both the AD treatment approach taken by physicians and sick leave days.

Conclusion

Our data showed no differences in baseline characteristics between patients receiving antidepressant monotherapy or antidepressant combination/switch/add-on therapy. This, together with the very low number of patients starting antidepressant combination therapy at the Index Date, seems to suggest that there were no particular reasons driving the initial antidepressant therapeutic approach that, nevertheless, was identified as the predictor with the highest influence on sick leave days in major depressive disorder patients. Another factor significantly affecting sick leave days was the promptness of starting antidepressant treatment when major depressive disorder is diagnosed. Such findings suggest that a patient tailored approach may improve functional recovery and help reducing the socio-economic burden of the disease. As this study relied on secondary data and, for this reason, it has intrinsic limitations, the authors would like to underline that its findings should not be considered conclusive, but rather propaedeutic to the planning of future studies. In particular, conducting observational studies with prospective and ad-hoc data collection would allow investigating the effect of antidepressant treatment approach and patients’ characteristics on sick leave days, also taking into account the efficacy and tolerability of treatment.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (38.5 KB)Acknowledgments

Annalisa Bonelli, Alessandro Comandini, Giorgio Di Dato and Valeria Pegoraro were involved in the conception and design of the study. Valeria Pegoraro was involved in data analysis and drafting the paper. Siegfried Kasper, Diego Palao, Miquel Roca and Hans-Peter Volz were responsible for the conception and design of the study, as well as for clinical validation of the study and review of the manuscript. All the authors were involved in data interpretation and critically reviewed the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure statement

This study was funded by Angelini Pharma S.p.A. Annalisa Bonelli, Agnese Cattaneo, Alessandro Comandini, and Giorgio Di Dato are employees of Angelini Pharma S.p.A. Franca Heiman and Valeria Pegoraro are employees of IQVIA. Siegfried Kasper received grants/research support, consulting fees and/or honoraria within the last three years from Angelini, AOP Orphan Pharmaceuticals AG, Celgene GmbH, Janssen-Cilag Pharma GmbH, KRKA-Pharma, Lundbeck A/S, Mundipharma, Neuraxpharm, Pfizer, Sage, Sanofi, Schwabe, Servier, Shire, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma Co. Ltd., Sun Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. and Takeda. Miquel Roca received research funds or grants from Angelini, Janssen, Lundbeck and Pfizer. Hans-Peter Volz received grants/research support, consulting fees and/or honoraria within the last three years from Lundbeck, Pfizer, Schwabe, Bayer, Janssen-Cilag, Neuraxpharm, Recordati, AstraZeneca, Gilead, Servier, Otsuka, Recordati. Diego Palao has received grants and also served as consultant or advisor for Angelini, Janssen, Lundbeck and Servier.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. 2010. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder, Third Edition.

- Asay GRB, Roy K, Lang JE, Payne RL, Howard DH. 2016. Absenteeism and employer costs associated with chronic diseases and health risk factors in the US workforce. Prev Chronic Dis. 13:E141.

- Becher H, Kostev K, Schröder-Bernhardi D. 2009. Validity and representativeness of the “Disease Analyzer” patient database for use in pharmacoepidemiological and pharmacoeconomic studies. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 47(10):617–626.

- Birnbaum HG, Cremieux PY, Greenberg PE, Kessler RC. 2000. Management of major depression in the workplace: impact on employee work loss. Dis Manag Health Outcomes. 7(3):163–171.

- Bowling A. 1995. What things are important in people’s lives? A survey of the public’s judgements to inform scales of health related quality of life. Soc Sci Med. 41(10):1447–1462.

- Bschor T, Baethge C. 2010. No evidence for switching the antidepressant: systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs of a common therapeutic strategy. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 121(3):174–179.

- Bschor T, Kern H, Henssler J, Baethge C. 2018. Switching the antidepressant after nonresponse in adults with major depression: a systematic literature search and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 79(1):16r10749.

- Bültmann U, Rugulies R, Lund T, Christensen KB, Labriola M, Burr H. 2006. Depressive symptoms and the risk of long-term sickness absence: a prospective study among 4747 employees in Denmark. Soc Psychiat Epidemiol. 41(11):875–880.

- Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, Chaimani A, Atkinson LZ, Ogawa Y, Leucht S, Ruhe HG, Turner EH, Higgins JPT, et al. 2018. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet. 391(10128):1357–1366.

- Claxton AJ, Chawla AJ, Kennedy S. 1999. Absenteeism among employees treated for depression. J Occup Environ Med. 41(7):605–611.

- Dewa CS, Hoch JS, Lin E, Paterson M, Goering P. 2003. Pattern of antidepressant use and duration of depression-related absence from work. Br J Psychiatry. 183(6):507–513.

- DGPPN, BÄK, KBV, AWMF, AkdÄ, BPtK, BApK, DAGSHG, DEGAM, DGPM, & DGPs, DGRW (Ed). 2009. S3-Leitlinie/Nationale VersorgungsLeitlinie Unipolare Depression.

- Ebrahim S, Guyatt GH, Walter SD, Heels-Ansdell D, Bellman M, Hanna SE, Patelis-Siotis I, Busse JW. 2013. Association of psychotherapy with disability benefit claim closure among patients disabled due to depression. PLoS One. 8(6):e67162.

- Ehlken B, Shlaen M, Torres M. d P L F d, Hisada M, Bennett D. 2019. Use of azilsartan medoxomil in the primary-care setting in Germany: a real-world evidence study. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 57(6):275–283.

- Ervasti J, Joensuu M, Pentti J, Oksanen T, Ahola K, Vahtera J, Kivimaki M, Virtanen M. 2017. Prognostic factors for return to work after depression-related work disability: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 95:28–36.

- Fagot J-P, Cuerq A, Samson S, Fagot-Campagna A. 2016. Cohort of one million patients initiating antidepressant treatment in France: 12-month follow-up. Int J Clin Pract. 70(9):744–751.

- Freytag A, Krause M, Lehmann T, Schulz S, Wolf F, Biermann J, Wasem J, Gensichen J. 2017. Depression management within GP-centered health care – a case-control study based on claims data. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 45:91–98.

- Gaebel W, Kowitz S, Zielasek J. 2012. The DGPPN research project on mental healthcare utilization in Germany: inpatient and outpatient treatment of persons with depression by different disciplines. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 262(Suppl 2):S51–S55.

- Gasse C, Petersen L, Chollet J, Saragoussi D. 2013. Pattern and predictors of sick leave among users of antidepressants: a Danish retrospective register-based cohort study. J Affect Disord. 151(3):959–966.

- Gili M, Roca M, Basu S, McKee M, Stuckler D. 2013. The mental health risks of economic crisis in Spain: evidence from primary care centres, 2006 and 2010. Eur J Public Health. 23(1):103–108.

- Goetzel RZ, Gibson TB, Short ME, Chu B, Waddel J, Bowen J, Lemon SC, Fernandez ID, Ozminkowski RJ, Wilson MG, et al. 2010. A multi-worksite analysis of the relationships among body mass index, medical utilization, and worker productivity. J Occup Environ Med. 52(1S):S52–S58.

- Gordeev VS, Maksymowych WP, Schachna L, Boonen A. 2014. Understanding presenteeism in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: contributing factors and association with sick leave: presenteeism in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Care Res. 66(6):916–924.

- Hansen RA, Gartlehner G, Lohr KN, Gaynes BN, Carey TS. 2005. Efficacy and safety of second-generation antidepressants in the treatment of major depressive disorder. Ann Intern Med. 143(6):415–426.

- Hemels ME, Kasper S, Walter E, Einarson TR. 2004a. Cost-effectiveness of escitalopram versus citalopram in the treatment of severe depression. Ann Pharmacother. 38(6):954–960.

- Hemels MEH, Kasper S, Walter E, Einarson TR. 2004b. Cost-effectiveness analysis of escitalopram: a new SSRI in the first-line treatment of major depressive disorder in Austria. Curr Med Res Opin. 20(6):869–878.

- Hofmann SG, Curtiss J, Carpenter JK, Kind S. 2017. Effect of treatments for depression on quality of life: a meta-analysis. Cogn Behav Ther. 46(4):265–286.

- Jeschke E, Ostermann T, Vollmar HC, Tabali M, Matthes H. 2012. Depression, comorbidities, and prescriptions of antidepressants in a german network of GPs and specialists with subspecialisation in anthroposophic medicine: a longitudinal observational study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012:508623–508628.

- Kennedy SH, Avedisova A, Belaïdi C, Picarel-Blanchot F, de Bodinat C. 2016. Sustained efficacy of agomelatine 10 mg, 25 mg, and 25–50 mg on depressive symptoms and functional outcomes in patients with major depressive disorder: a placebo-controlled study over 6 months. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 26(2):378–389.

- Kessler RC, Bromet EJ. 2013. The epidemiology of depression across cultures. Annu Rev Public Health. 34:119–138.

- Krauth C, Stahmeyer JT, Petersen JJ, Freytag A, Gerlach FM, Gensichen J. 2014. Resource utilisation and costs of depressive patients in germany: results from the primary care monitoring for depressive patients trial. Depress Res Treat. 2014:730891.

- Lee Y, Rosenblat JD, Lee JG, Carmona NE, Subramaniapillai M, Shekotikhina M, Mansur RB, Brietzke E, Lee JH, Ho RC, et al. 2018. Efficacy of antidepressants on measures of workplace functioning in major depressive disorder: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 227:406–415.

- Merola D, Yong C, Noga SJ, Shermock KM. 2018. Costs associated with productivity loss among U.S. patients newly diagnosed with multiple myeloma receiving oral versus injectable chemotherapy. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 24(10):1019–1026.

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK). 2010. Depression: the treatment and management of depression in adults (Updated Edition). London: British Psychological Society.

- Nieuwenhuijsen K, Bültmann U, Neumeyer ‐Gromen A, Verhoeven AC, Verbeek JH, Feltz‐Cornelis CM. 2008. Interventions to improve occupational health in depressed people. In: The Cochrane Collaboration, editor. Cochrane database of systematic reviews. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- Rathmann W, Bongaerts B, Carius H-J, Kruppert S, Kostev K. 2018. Basic characteristics and representativeness of the German Disease Analyzer database. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 56(10):459–466.

- Roca M, Gili M, Garcia-Garcia M, Salva J, Vives M, Garcia Campayo J, Comas A. 2009. Prevalence and comorbidity of common mental disorders in primary care. J Affect Disord. 119(1–3):52–58.

- Romera I, Pérez V, Menchòn JM, Schacht A, Papen R, Neuhauser D, Abbar M, Svanborg P, Gilaberte I. 2012. Early switch strategy in patients with major depressive disorder: a double-blind, randomized study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 32(4):479–486.

- Ruhé HG, Huyser J, Swinkels JA, Schene AH. 2006. Switching antidepressants after a first selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor in major depressive disorder: a systematic review. J Clin Psychiatry. 67(12):1836–1855.

- Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Stewart JW, Nierenberg AA, Thase ME, Ritz L, Biggs MM, Warden D, Luther JF, et al. 2006. Bupropion-SR, sertraline, or venlafaxine-XR after failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med. 354(12):1231–1242.

- Schosser A, Serretti A, Souery D, Mendlewicz J, Zohar J, Montgomery S, Kasper S. 2012. European Group for the Study of Resistant Depression (GSRD)-where have we gone so far: review of clinical and genetic findings. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 22(7):453–468.

- Skoglund I, Bjorkelund C, Svenningsson I, Petersson E, Augustsson P, Nejati S, Ariai N, Hange D. 2019. Influence of antidepressant therapy on sick leave in primary care: ADAS, a comparative observational study. Heliyon. 5(1):e01101.

- Stang P, Morris L, Kempf J, Henderson S, Yood MU, Oliveria S. 2007. The coprescription of contraindicated drugs with statins: continuing potential for increased risk of adverse events. Am J Ther. 14(1):30–40.

- Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Chee E, Hahn SR, Morganstein D. 2003. Cost of lost productive work time among US workers with depression. JAMA. 289(23):3135.

- Tanislav C, Jacob L, Kostev K. 2021. Consultations decline for stroke, transient ischemic attack, and myocardial infarction during the COVID-19 pandemic in germany. Neuroepidemiology. 55(1):1–8.

- Wang G, Gislum M, Filippov G, Montgomery S. 2015. Comparison of vortioxetine versus venlafaxine XR in adults in Asia with major depressive disorder: a randomized, double-blind study. Curr Med Res Opin. 31(4):785–794.

- Wedegärtner F, Sittaro N-A, Emrich H, Dietrich D. 2007. [Disability caused by affective disorders-what do the Federal German Health report data teach us?]. Psychiatr Prax. 34(Suppl 3):S252–S255.

- Wiegand HF, Sievers C, Schillinger M, Godemann F. 2016. Major depression treatment in Germany-descriptive analysis of health insurance fund routine data and assessment of guideline-adherence. J Affect Disord. 189:246–253.

- Winkler D, Pjrek E, Moser U, Kasper S. 2007. Escitalopram in a working population: results from an observational study of 2378 outpatients in Austria. Hum Psychopharmacol Clin Exp. 22(4):245–251.

- World Health Organization. 2017. Depression and other common mental disorders global health estimates. Geneva: WHO.