Abstract

Background

Antidepressants are one of the most frequently prescribed groups of medications. The aim of the study was to evaluate the prevalence and patterns of antidepressants prescribed between 2009 and 2018 in Slovenia in different patient-age groups.

Methods

This retrospective cross-sectional study performed a nationwide database analysis of all outpatient antidepressant prescriptions based on Slovenian health claims data. Prevalence was defined as number of recipients prescribed at least one antidepressant per 1000 inhabitants. Antidepressant consumption was presented as total dispensed defined daily doses per year.

Results

In 2018, 147,300 patients were prescribed at least one antidepressant. The prevalence had increased by 16% in ten years and by 7.6% in age standardised data. The largest increase in prevalence was seen in the oldest patients (>80 years, 25% increase); of these, antidepressants are now prescribed to 1 in 4. Use of antidepressants had increased by 38%, suggesting longer treatment duration, increase in dose prescribed or both. SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) were the most prescribed antidepressants (70% share), with escitalopram and sertraline the most commonly prescribed antidepressants.

Conclusion

The prevalence of antidepressant prescribing and antidepressant consumption is increasing, mainly due to the population ageing and the increasing prescribing in elderly patients.

The prevalence of antidepressant prescribing as well as antidepressants’ consumption is increasing, reflecting both population ageing and rising prescribing rates.

The increase in prevalence and consumption is most dramatic in the oldest patients (over 80 years of age).

SSRIs continue to be the most commonly prescribed antidepressants, whilst prescribing of SNRIs is increasing.

Future research should focus on evaluating appropriate prescribing of antidepressants (treatment selection, dosage and duration), especially in the elderly.

Key Points

Introduction

Antidepressants (AD) are one of the most commonly prescribed groups of medications in Europe (Abbing-Karahagopian et al., Citation2014; Forns et al., Citation2019). Their widespread use can be attributed to the range of indications they treat, including depression, generalised anxiety disorder, sleep-wake disorders and neuropathic pain (Wong et al., Citation2017). A growing body of information from randomised controlled trials has led to clinical practice guidelines that provide specific recommendations for the most appropriate AD classes, as well as within-class medications (Cipriani et al., Citation2018).

AD use has been shown to have increased over the years, not only in Europe but also globally (Noordam et al., Citation2015; Forns et al., Citation2019; Luo & Kataoka, Citation2020) and some studies have reported a greater increase in older patients. Although AD therapy has many benefits, if administered inadequately or not monitored, it may lead to potential adverse effects, such as an increased risk of falls, fractures, QT prolongation and even increased mortality rates, especially among the elderly (Boström et al., Citation2016; Sobieraj et al., Citation2019). Increased prescribing trends can also involve an increased risk of adverse events. However, it is not yet clear to what extent the increase in prescribing prevalence can be attributed to an increase in AD prescribing rates and to what extent it is due to the ageing of the population and hence increasing number of elderly patients.

Although many studies report an increase in the prevalence of AD recipients in recent years, the studies do not provide in-depth information regarding specific AD consumption (Forns et al., Citation2019; Luo & Kataoka, Citation2020; Noordam et al., Citation2015). Clinical guidelines report substantial differences between AD in terms of effectiveness as well as safety. In a recent systematic review and network meta-analysis agomelatine, amitriptyline, escitalopram and mirtazapine proved the most effective, while agomelatine, citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, sertraline, and vortioxetine were tolerated best. On the other hand, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, reboxetine, and trazodone were the least effective medications and amitriptyline, clomipramine, duloxetine, fluvoxamine, reboxetine, trazodone, and venlafaxine had the highest discontinuation rates (Cipriani et al., Citation2018). Because of these substantial differences, the right choice of treatment is crucial (Cipriani et al., Citation2018; NICE, Citation2020).

Even less information is available on AD consumption in different patient subgroups (e.g., elderly patients) in clinical practice. Reporting patterns of AD use is important: both to inform clinical practice and to identify subgroups that may be vulnerable to AD underuse, overuse or other forms of misuse.

In this study, we analyse the prevalence of AD recipients and AD use in six different patient age groups from 2009 to 2018.

Methods

Study design and population

This retrospective cross-sectional study analyses health claims data containing all outpatient AD prescriptions issued in Slovenia in the period from 1 January 2009 to 31 December 2018 (the ‘study period’). The inclusion criterion for the study was that study participants had at least one AD prescription dispensed to them over at least one year of the study period. Study participants were then followed until the first of the following endpoints was reached: (i) death, (ii) treatment discontinuation or (iii) end of the study period. ADs were defined as medications with Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification N06A.

Data sources

Health claims data were obtained from the national database of the Slovenian Health Insurance Institute, the authority that manages insurance funds on behalf of the national health system in Slovenia; statutory health insurance is provided to the entire Slovenian population. The health claims database lists all publicly funded outpatient prescriptions dispensed in Slovenia. The database does not include information on sales of over-the-counter medications, hospital-dispensed medications, or privately (out-of-pocket) prescribed medications. More details on the Slovenian healthcare system and data on health claims can be found elsewhere (Cebron Lipovec et al., Citation2020).

All study data were anonymized and unique patient identifiers were allocated, allowing patient-level analysis. Patient-specific study variables were sex and age, and prescription-specific study variables were: dispensed medications, coded by the ATC classification, and date of prescription; neither the prescribed dose nor the prescribing indication were included as study variables.

Ethical considerations

Our study was a retrospective analysis of routinely collected data from the Slovenian Health Insurance Institute, which required no ethical approval.

Data analysis

The prevalence of AD recipients in specific age groups in the study was defined as the number of study participants (‘recipients’) divided by the total Slovenian population in that calendar year, expressed as recipients per 1000 inhabitants. Age standardised prevalence was calculated using the age distribution of the Slovenian population in 2009. AD consumption was defined as the total number of AD defined daily doses (DDDs) per 1000 inhabitants (DDDs/1000 inhabitants/day), where DDD is defined as »the assumed average maintenance dose per day for a drug used for its main indication in adults« (WHO, Citation2020). AD consumption for individual ADs was calculated as the proportion of DDD for each individual AD divided by the total AD consumption in each year of analysis. Study participants were placed into the following age groups: <18 years, 18 − 30 years, 31 − 50 years, 51 − 64 years, 65 − 80 years and >80 years. All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 25.0.

Results

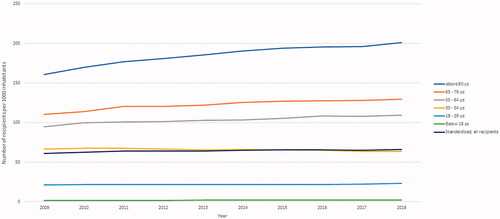

Our study included between 124,500 and 147,300 AD recipients in each year analysed. The prevalence of AD recipients increased steadily over the study period, from 61 recipients per 1000 inhabitants in 2009 to 71 recipients per 1000 inhabitants in 2018. While overall prevalence increased by 16.4% over a 10-year period, age-standardised prevalence increased by 7.6% over the same period.

Prevalence increased with the age of study participants throughout the study period, with ADs most commonly prescribed to older patients (>65 years). The largest increase in the number of recipients was observed in the oldest patients’ group (>80 years), which increased from 161 patients per 1000 inhabitants in 2009 to 200 patients per 1000 inhabitants in 2018). In patients aged 55 to 79 years, the prevalence ranged from 95 to 110 recipients per 1000 inhabitants in 2009 and showed a small but steady increase over the study period. In younger patients (<55 years), the prevalence remained constant throughout the study period. In women, the prevalence was about twice as high as in men during the entire study period.

AD consumption, represented as the number of prescribed DDDs, increased by 38% over the study period, from 43 DDD/1000 inhabitants/day in 2009 to 60 DDD/1000 inhabitants/day in 2018. Among elderly patients, the total number of prescribed DDDs was twice as high as of all AD recipients – 85 DDD/1000 inhabitants/day in 2009, which increased to 120 DDD/1000 inhabitants/day in 2018.

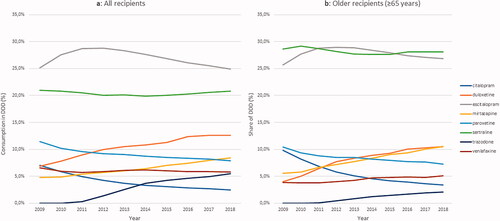

In the overall population, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) accounted for 75% of all AD prescriptions in 2009, and 67% in 2018, and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) accounted for 12% of all AD prescriptions in 2009, and 18% in 2018. The most commonly prescribed ADs throughout the study period were escitalopram and sertraline, each accounting for approximately 25% of all DDDs dispensed. The next most commonly prescribed ADs were: duloxetine (5% of all AD prescriptions in 2009, increasing to 11% by 2018), mirtazapine (5%, increasing to 8%), paroxetine (13%, decreasing to 9%), citalopram (8%, decreasing to 3%) and venlafaxine (steady 8% throughout the study period).

Among older recipients, prescribing patterns were similar to those in the general population. Sertraline and escitalopram were also the most commonly prescribed ADs, accounting for more than 50% of all ADs throughout the study period. Sertraline and mirtazapine were more frequently prescribed to older recipients compared to the overall study population.

Discussion

The prevalence of AD recipients in Slovenia has increased steadily over the observed 10 years, reaching a relative increase of 16%. If the effects of population ageing are taken into account, the increase in prevalence was approximately 8%. The greatest increase in prevalence was observed among the oldest patients, in whom the number of AD recipients increased by 25%, so that, in 2018, every fourth participants aged > 80 years received at least one AD prescription. We conclude that the overall increase in prevalence is therefore mainly due to population ageing and increasing prescribing rates among the oldest patients.

This study found that the overall prevalence of AD recipients in Slovenia was close to the reported European average (7.2% for 2010) but below the US average (10.4% for 2015) (Lewer et al., Citation2015; Luo & Kataoka, Citation2020) The prevalence was twice as high in older patients compared to younger patients, reflecting similar patterns as were reported in Denmark and in the Netherlands (Abbing-Karahagopian et al., Citation2014; Sonnenberg et al., Citation2008). Similarly, the number of AD recipients was twice as high in female patients as in men, also reflecting similar patterns reported in Spain, Germany, Denmark, UK and the Netherlands (Abbing-Karahagopian et al., Citation2014).

The observed 38% increase in AD consumption (total DDDs) over the ten-year period is similar to data from Spain (49% increase in prescribed DDDs) and Sweden (33% increase in DDDs), but lower than in Australia (50% increase in DDDs) (Eek et al., Citation2021; Forns et al., Citation2019) The 100% increase in AD use compared to the corresponding prevalence suggests an increase in treatment dose or duration of use; similar increases in AD duration have been reported in the USA (Luo & Kataoka, Citation2020).

The results of this study show that SSRIs were the most commonly prescribed class of ADs during the study period, accounting for approximately 60% of all ADs prescribed in 2018; this finding is not surprising in the context of current clinical guidelines for the treatment of major depressive disorders in adults (Cipriani et al., 2018; NICE, Citation2020). The number of SSRI prescriptions in Slovenia increased steadily over the study period, with a similar increase to that found in a recent study of AD prescribing patterns in five other European countries (Abbing-Karahagopian et al., Citation2014; Sonnenberg et al., Citation2008). However, the overall proportion of AD prescriptions for SSRI medications decreased from 68% to 58%; this decrease was mainly due to a lower number of prescriptions for paroxetine and citalopram. While the low prescription rates of citalopram are similar to those found in Spain, they are contrary to comparable data for AD initiators in Germany, Denmark and Sweden, where citalopram is one of the most commonly prescribed ADs (Forns et al., Citation2019) Escitalopram, on the other hand, was the most commonly prescribed AD, in contrast with various other countries, but in line with current reviews, which report escitalopram as being one of the best ADs in terms of efficacy and acceptability (Cipriani et al., Citation2018).

Prescribing rates for mirtazapine are increasing in several European countries, especially among the elderly (Forns et al., Citation2019) In some clinical guidelines, mirtazapine is considered as first-line treatment (Gabriel et al., Citation2020) due to its rapid onset of action, good patient adherence and high efficacy (Cipriani et al., 2018). The PRISCUS list recommends mirtazapine as a possible alternative to benzodiazepines due to its sedative effects (Holt et al., Citation2010). Duloxetine has also increased in prescriptions, nearly doubling in the last decade; this increase in prescribing may be partly due to the wide range of prescribing indications, which include indications that are not related to depression (Wong et al., Citation2017). Many previous generation ADs, such as TCA, are falling out of favour in a number of European countries, including Slovenia (Abbing-Karahagopian et al., Citation2014). Although the two newest ADs on the Slovenian market, agomelatine and vortioxetine, are attracting clinical attention, their prescribing rate remains below 5% of the total market. Both ADs showed effectiveness and satisfactory tolerability in major depressive disorder and may hence be either a valuable alternative to SSRIs or SNRIs in the course of monotherapy or be administered in the course of antidepressant combination treatments (Dold & Kasper, Citation2017). In Slovenia, both medications have prescribing restrictions and may only be used in adults as second-line therapy for severe depressive episodes, based on a recommendation by the patient’s psychiatrist (Agomelatine, Citation2021; Vortioxetine, Citation2021).

A recent study by Seifert et al. analysed the time trends in pharmacological treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD) in psychiatric inpatients in Germany, Austria and Switzerland between 2001 and 2017. Results should be compared with caution since the authors presented the percentage of patients on therapy, whereas we presented the percentage of DDD dispensed: interesting differences may be observed. The authors observed a slight decrease in the number of patients on AD treatment, whereas our results show a substantial increase in AD consumption. Similar to our findings, the authors reported a steep decline in prescribing of TCA and increase in SNRI prescribing, whilst SSRI use remain consistent over time, albeit much less prevalent (max 35% patients versus 70% consumption rate in our study). Contrary to our findings, NaSSa, mostly mirtazapine, were used more frequently (max ca. 32% of patients) and declined over the observed period. Some of the observed differences may be explained by the fact that a different population was analysed (psychiatric inpatients with confirmed MDD versus general outpatients), among others. (Seifert et al., Citation2021).

The increase in AD prescribing, especially in the elderly, is alarming. Although most new ADs are very effective and tolerable and thus valuable substances in reducing depressive symptoms and preventing detrimental consequences such as treatment-resistant depression, chronicity as well as suicide, inadequate and/or unmonitored prescribing poses a serious risk to patients. Even when an AD prescribing decision follows current clinical guidelines, that decision may not be properly clinically justified. Elderly patients are particularly vulnerable to adverse drug reactions, such as increased risk of falls, fractures, QT prolongation which may translate into reduced mobility and independence as well as increased mortality rates (Coupland et al., Citation2011; Pisa et al., Citation2020). Increased AD use is linked to prolonged treatment duration; this may either reflect appropriate maintenance treatment for depression (six months to one year or longer, depending on the individual disease course (Bauer et al., Citation2017) or it may be potentially unwarranted prolonged treatment,. Due to the limitations of our study, the exact interpretation of increased consumption is not possible. However, prolonged treatment duration and potential AD overprescribing in elderly patients has been reported elsewhere (Alduhishy, Citation2018; Stroka, Citation2016) and constitutes a challenge, which needs to be carefully addressed and requires further research.

The present study needs to be interpreted in light of its limitations. The database used does not contain patient diagnoses nor the indication for which the AD was prescribed. As antidepressants are the first-line treatment for various diagnoses besides depression, e.g., anxiety disorders and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), the results was not necessarily representative of the pharmacological treatment of depression in Slovenia. Similarly, it was not possible to evaluate the prescribed daily doses. In the absence of patient adherence data, actual AD use may be lower than the reported prescribing rates. Furthermore, the database analysed includes only ADs prescribed in outpatient practices and does not include prescriptions dispensed by hospitals and out-of-pocket prescriptions. However, in Slovenia, there are almost no medications dispensed by hospitals, whilst out-of-pocket prescriptions represent less than 3% of all outpatient prescriptions (Kostnapfel & Albreht, Citation2020) Consequently, the results from our database cover almost all dispensed antidepressants in Slovenia. At the same time, our study includes a large population sample, represents AD use over a 10-year period and is one of the few studies that provide age-standardised prevalence data. Hence, it provides a comprehensive insight into prescribing patterns at both the population level and in older patients.

Figure 2. Consumption of individual AD for (a) all recipients and (b) older recipients. Values are presented only for AD which exceeded a consumption of 5% at any point. AD analysed, but not shown in the figure include: agomelatine, amitriptyline, bupropion, doxepin, fluoxetine, clomipramine, maprotiline, mianserin, moclobemide, reboxetine, tianeptine, vortioxetine.

Conclusions

The prevalence of AD recipients and AD use has increased over past decade, reflecting both an ageing population and higher prescribing rates. AD use has increased most in older patients, with SSRIs (escitalopram and sertraline) being the most commonly prescribed ADs, closely followed by mirtazapine and duloxetine. The rapid increase in prevalence and even higher increase in medication use, especially in older patients, requires further research and clinical attention.

Disclosure statement

No relevant financial or non-financial competing interests to report.

References

- Abbing-Karahagopian, V., Huerta, C., Souverein, P. C., de Abajo, F., Leufkens, H. G. M., Slattery, J., Alvarez, Y., Miret, M., Gil, M., Oliva, B., Hesse, U., Requena, G., de Vries, F., Rottenkolber, M., Schmiedl, S., Reynolds, R., Schlienger, R. G., de Groot, M. C. H., Klungel, O. H., … De Bruin, M. L. (2014). Antidepressant prescribing in five European countries: Application of common definitions to assess the prevalence, clinical observations, and methodological implications. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 70(7), 849–857. doi:10.1007/s00228-014-1676-z

- Agomelatine. (2021). Slovenian central drugs database: http://www.cbz.si/cbz/bazazdr2.nsf/o/B95EE4893CC76478C12583CA0005A126?opendocument

- Alduhishy, M. (2018). The overprescription of antidepressants and its impact on the elderly in Australia. Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, 40(3), 241–243. doi:10.1590/2237-6089-2016-0077

- Bauer, M., Severus, E., Möller, H.-J., Young, A. H, & WFSBP Task Force on Unipolar Depressive Disorders. (2017). Pharmacological treatment of unipolar depressive disorders: Summary of WFSBP guidelines. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, 21(3), 166–176. doi:10.1080/13651501.2017.1306082

- Cebron Lipovec, N., Jazbar, J., & Kos, M. (2020). Anticholinergic burden in children, adults and older adults in Slovenia: A nationwide database study. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 020–65989. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-65989-9

- Cipriani, A., Furukawa, T. A., Salanti, G., Chaimani, A., Atkinson, L. Z., Ogawa, Y., Leucht, S., Ruhe, H. G., Turner, E. H., Higgins, J. P. T., Egger, M., Takeshima, N., Hayasaka, Y., Imai, H., Shinohara, K., Tajika, A., Ioannidis, J. P. A., & Geddes, J. R. (2018). Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Focus (American Psychiatric Publishing), 16(4), 420–429. doi:10.1176/appi.focus.16407

- Coupland, C., Dhiman, P., Morriss, R., Arthur, A., Barton, G., & Hippisley-Cox, J. (2011). Antidepressant use and risk of adverse outcomes in older people: Population based cohort study. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 343(343), d4551. doi:10.1136/bmj.d4551

- Dold, M., & Kasper, S. (2017). Evidence-based pharmacotherapy of treatment-resistant unipolar depression. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, 21(1), 13–23. doi:10.1080/13651501.2016.1248852

- Eek, E., Driel, M., Falk, M., Hollingworth, S. A., & Merlo, G. (2021). Antidepressant use in Australia and Sweden – A cross-country comparison. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety, 30(4), 409–417. doi:10.1002/pds.5158

- Forns, J., Pottegård, A., Reinders, T., Poblador-Plou, B., Morros, R., Brandt, L., Cainzos-Achirica, M., Hellfritzsch, M., Schink, T., Prados-Torres, A., Giner-Soriano, M., Hägg, D., Hallas, J., Cortés, J., Jacquot, E., Deltour, N., Perez-Gutthann, S., Pladevall, M., & Reutfors, J. (2019). Antidepressant use in Denmark, Germany, Spain, and Sweden between 2009 and 2014: Incidence and comorbidities of antidepressant initiators. Journal of Affective Disorders, 249, 242–252. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2019.02.010

- Gabriel, F. C., de Melo, D. O., Fráguas, R., Leite-Santos, N. C., Mantovani da Silva, R. A., & Ribeiro, E. (2020). Pharmacological treatment of depression: A systematic review comparing clinical practice guideline recommendations. PLoS One, 15(4), e0231700. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0231700

- Boström, G., Hörnsten, C., Brännström, J., Conradsson, M., Nordström, P., Allard, P., Gustafson, Y., & Littbrand, H. (2016). Antidepressant use and mortality in very old people. International Psychogeriatrics, 28(7), 1201–1210. doi:10.1017/S104161021600048X

- Holt, S., Schmiedl, S., & Thürmann, P. A. (2010). Potentially inappropriate medications in the elderly: The PRISCUS list. Deutsches Arzteblatt International, 107(31–32), 543–551.

- Kostnapfel, T., & Albreht, T. (2020). “Use of ambulatory prescribed medications in Slovenia in 2019.” National Public Health Institute Report. https://www.nijz.si/sites/www.nijz.si/files/publikacije-datoteke/publikacija_220520_koncno_0.pdf. Accessed October 2021.

- Lewer, D., O'Reilly, C., Mojtabai, R., & Evans-Lacko, S. (2015). Antidepressant use in 27 European countries: Associations with sociodemographic, cultural and economic factors. The British Journal of Psychiatry : The Journal of Mental Science, 207(3), 221–226. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.114.156786

- Luo, Y., & Kataoka, Y. (2020). National prescription patterns of antidepressants in the treatment of adults with major depression in the US between 1996 and 2015: A population representative survey based analysis. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 35. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00035

- NICE. (2020). "National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Depression in adults: treatment and management (update)." from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/indevelopment/gidcgwave0725/documents. Accessed 3 November 2020.

- Noordam, R., Aarts, N., Verhamme, K. M., Sturkenboom, M. C. M., Stricker, B. H., & Visser, L. E. (2015). Prescription and indication trends of antidepressant drugs in the Netherlands between 1996 and 2012: A dynamic population-based study. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 71(3), 369–375. doi:10.1007/s00228-014-1803-x

- Pisa, F. E., Reinold, J., Kollhorst, B., Haug, U., & Schink, T. (2020). Individual antidepressants and the risk of fractures in older adults: A new user active comparator study. Clinical Epidemiology, 12, 667–678. doi:10.2147/CLEP.S222888

- Seifert, J., Engel, R. R., Bernegger, X., Führmann, F., Bleich, S., Stübner, S., Sieberer, M., Greil, W., Toto, S., & Grohmann, R. (2021). Time trends in pharmacological treatment of major depressive disorder: Results from the AMSP Pharmacovigilance Program from 2001–2017. Journal of Affective Disorders, 281, 547–556. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2020.12.073

- Sobieraj, D. M., Martinez, B. K., Hernandez, A. V., Coleman, C. I., Ross, J. S., Berg, K. M., Steffens, D. C., & Baker, W. L. (2019). Adverse effects of pharmacologic treatments of major depression in older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 67(8), 1571–1581. doi:10.1111/jgs.15966

- Sonnenberg, C. M., Deeg, D. J. H., Comijs, H. C., van Tilburg, W., & Beekman, A. T. F. (2008). Trends in antidepressant use in the older population: Results from the LASA-study over a period of 10 years. Journal of Affective Disorders, 111(2–3), 299–305. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2008.03.009

- Stroka, M. A. (2016). Drug overprescription in nursing homes: An empirical evaluation of administrative data. The European Journal of Health Economics : HEPAC : Health Economics in Prevention and Care, 17(3), 257–267. doi:10.1007/s10198-015-0676-y

- Vortioxetine (2021). Slovenian central drugs database: http://www.cbz.si/cbz/bazazdr2.nsf/o/F4FF2FFBC3B3DA30C1257C780004AF79?opendocument

- WHO. (2020). WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology Norwegian Institute of Public Health. ATC/DDD Index, https://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/?code=N06A&showdescription=no. Accessed: 3rd November 2020.

- Wong, J., Motulsky, A., Abrahamowicz, M., Eguale, T., Buckeridge, D. L., & Tamblyn, R. (2017). Off-label indications for antidepressants in primary care: Descriptive study of prescriptions from an indication based electronic prescribing system. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 356(356), j603. doi:10.1136/bmj.j603