Abstract

Purpose

In diagnostic systems (e.g., DSM-5, ICD-10), depression is defined categorically. However, the concept of subthreshold depression (SD) has gained increasing interest in recent years. The purpose of the present paper was to review, based on a scoping review, the relevant papers in this field published between October 2011 and September 2020.

Materials and methods

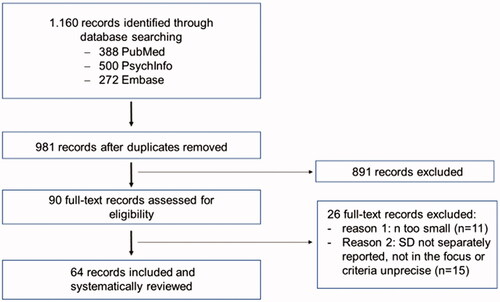

Of the 1,160 papers identified, 64 records could be included in further analysis. The scoping review was conducted using both electronic and manual methods.

Results

The main result of the analysis is that the operationalisation criteria used are highly heterogeneous, which also leads to very heterogenous epidemiological data.

Conclusions

Clear conclusions are not possible scrutinising the reported results. Most definitions seem to be arbitrary, with considerable overlap (e.g., between SD and minor depression). The review also revealed that the impact of SD on quality of life and related parameters appear to be in the range of the respective impact of major depression (MD) and therapeutic approaches might be helpful for SD and also for the prevention of conversion from SD to MD. Keeping the presented difficulties in mind, a proposal for the definition of SD is made in the present paper in order to facilitate the discussion leading to more homogeneous criteria.

Introduction

In both the DSM-5 and ICD-10-system, depression is defined categorially. In DSM-5, the distinction between major and minor depression is given, in the ICD-10, the distinction between mild, moderate and severe depressive episodes. In the ICD-10, depressive adjustment disorders (ICD-10: F43.2) are defined – besides a critical life event as a trigger – as depressive symptoms which do not fulfil the criteria for a mild depressive episode. Regarding symptom severity, the definition of dysthymia in ICD-10 has much in common with depressive adjustment disorders. However, no critical life event can be identified and the duration has to be at least two years.

In the last decades and especially in the last 10–15 years, the concept of subthreshold depression (SD), which is sometimes also called subsyndromal depression, has gained increasing interest. The most widely used definition for SD is a clinically relevant level of depressive symptoms without meeting the diagnostic criteria for a major depressive disorder (MD) in the DSM system (or a depressive episode in the ICD-system). Such conditions can be defined dimensionally (i.e., by the definition of a cut-off score on a validated self-rating depression instrument without fulfilling the criteria for MD) or categorially (i.e., fewer than five symptoms of DSM-MD) (Ebert et al., Citation2018).

In 2012, Rodríguez et al. published a survey on SD conditions based on the literature published between January 2001 and September 2011 and identified with a PUBMED research. In this survey, the relevant data regarding definitions and associated factors of SD and also minor depression (as defined in DSM-IV) were reviewed. The main results of their work regarding SD are given in . It should be noted that minor depression (according to the DSM system) is not referred to here, since minor depression is not the topic of the presented paper. However, as the authors point out, there is a huge overlap between SD and minor depression, which can also be seen when scrutinising the respective diagnostic criteria for SD used by the different authors as depicted in of their thoroughly written review.

Table 1. Prevalences of subthreshold depression (SD) and related syndromes and settings according to Rodriguez et al. (Citation2012).

Rodriguez et al. (Citation2012) reported prevalence rates between 2.9 and 9.9% in primary care and 1.4–17.2% in community settings. Results regarding gender and family status remained unclear. It became obvious that quality of life was considerably lower in people with SD, although the quality of life was even more reduced in people with MD. The authors concluded that depression, as a disorder, is better explained as a spectrum rather than a “collection of discrete categories.” Since SD, although falling below the diagnostic categories, is also characterised by severe functional impairments, further research aiming to characterise this condition more precisely and more clearly is urgently needed, and a well-recognized unique definition of SD is still missing.

How important it is to come to a valid definition of SD can also be deduced from the fact that meta-analyses [for example regarding the efficacy of psychotherapeutic interventions (Cuijpers et al., Citation2014) or comparing mortality rates between MD and SD (Cuijpers et al., Citation2013)] already exist, summarising different studies. However, as these studies mostly use heterogeneous definitions of SD, the meaning of such meta-analyses is questionable. In the narrative review of Biella et al. (Citation2019) it is therefore also emphasised that, although SD is the most prevalent psychiatric condition in the elderly, no consensus regarding the diagnostic items varying across countries and research groups exists, which consecutively leads to the high variability of the reported results.

However, before a more valid definition of SD can be established, the current definitions and main epidemiological findings should be reviewed, also since 10 years have passed since the review of Rodriguez et al. (Citation2012) and only PUBMED/MEDLINE was used as a literature database in this review.

Thus, the purpose of the presented scoping review is two-fold: first, the systematic literature survey is continued starting from 2012 onwards, and second, the epidemiological data will be summarised and the diagnostic criteria will be extracted and discussed in order to help establish generalised operationalisations for SD instead of very individual approaches as has often been the case over the last 20 years.

Methods

The literature review was conducted using both electronic and manual methods. Regarding electronic methods, the search was performed in PUBMED/MEDLINE, PSYCHINFO and EMBASE databases covering October 2011 to September 2020. Search strategy focussed on terms for ‘subthreshold’ and ‘depression’, with ‘epidemiology’, ‘human and economic burden’ and ‘prevention and therapy’. The precise methods were again tailored to each database. The full search strategy for the PUBMED/MEDLINE database was: (minor depression [Title/Abstract] OR subthreshold depression [Title/Abstract] OR subsyndromal depression [Title/Abstract] OR subclinical depression [Title/Abstract] AND (subthreshold depressive symptoms OR subclinical depressive conditions). This search strategy corresponds exactly to that used by Rodriguez et al. (Citation2012). No restrictions for language were applied.’ References of the identified papers were screened manually to find additional related studies.

Eligibility criteria

After reading the abstracts, the eligibility of the selected full-text articles was evaluated by HPV and JS independently without automation tools using the following criteria:

Type of study: For epidemiological studies, only trials with original data published as full articles in peer-reviewed journals were included, no study protocols, diagnostic or methodological papers were considered. Moreover, only studies representative of the general population (including sub-populations of several age groups) or of specific patient populations (e.g., primary care or psychiatry) were included. In cases where two or more articles reported data from the same study sample, only the most relevant article was considered. Reviews and meta-analyses were excluded except for those of outstanding quality, as judged by HPV (e. g. adding additional aspects).

In contrast to the approach regarding epidemiological data, no requirements regarding the type of paper or the diagnostic criteria used had to be met in order to obtain complete information regarding operationalisation approaches for SD. With one exception: if the number of participants in the SD group was too small (i.e., number of participants < 60), then the respective paper was also not included.

Data extraction

Studies’ characteristics were extracted considering the following items: setting (general population, specific patient population, adolescents, adults, elderly, etc.), country, the study period of data collection, study design (longitudinal, cross-sectional, retrospective), sample size, age range, assessment of SD.

Assessment of methodological quality

As in the publication of Haller et al. (Citation2014) and in a comparable paper of our group (Volz et al., Citation2021), both works, however, dealing with subthreshold anxiety, a scoring system according to Loney et al. (Citation1998) was used in a modified way in order to critically score the epidemiological studies. One point was given for each of the following criteria:

Random population sample with an unbiased sampling strategy.

Adequate sample size (>1,000).

Adequate response rate (>70%).

Comparisons between respondents/non-respondents (i.e., those who refused the initial query).

Reliable and valid assessment of SD (standardised instruments used).

Less than three points were judged as “low quality,” at least three points as “high quality.”

Data analysis

No formal data analysis was performed and the respective data of the single studies are reported narratively.

Results

Search results

1,160 papers were identified in the database search. By manually checking the reference lists, no further papers could be identified. Of these 1,160 papers, 179 were duplicates. The remaining 981 abstracts were then screened, and 90 studies were read in full text to assess their eligibility for inclusion in this review. Of these, 26 studies were excluded: 11 because n was too low and 15 because SD was not the main focus of the respective paper. See also .

Subsyndromal depression – operationalisation

As can be seen from , the operationalisation of SD is very heterogeneous. However, certain patterns can be identified:

Table 2. Different definitions of subthreshold depression.

Combination of a validated instrument (mostly used: Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale-Revised [CESD], Brief Patient Health Questionnaire Mood Scale [PHQ-9] or Beck Depression Inventors [BDI-II]) to identify depressive symptoms and the exclusion of DSM-IV MD (exclusion sometimes also operationalised, e.g., via Composite International Diagnostic Interview [CIDI], Semi-Structured Clinical Interview [SCID] or Mini International Neuro-Psychiatric Interview [MINI]).

Only some, but not all DSM-(IV) symptoms of MD, exclusion of DSM (-IV) MD sometimes operationalised via CIDI, SCID or MINI.

By far the most often used instrument was the CESD, which was used in 16 of the listed 61 trials in . The CESD is a 20-item measure (an eight-item version is also used), originally published by Radloff (Citation1977). The patient or the caregiver is asked to rate depressive symptoms of the previous week like restless sleep, poor appetite, depressed mood, or feeling lonely (= rarely or none of the time, 1 = some or little of the time, 2 = moderately or much of the time, 3 = most or almost all the time). Scores range from 0 to 60, with high scores indicating pronounced depressive symptoms.

The most commonly used definition for SD using CESD is CESD ≥ 16. However, other cut-off values were also used, e.g., > 9 or between 8 and 15. Besides the different cut-off values, it is sometimes difficult to compare such defined populations across different studies, as different versions of the CESD exist.

The second most frequently used instrument was the PHQ-9 (Kroenke et al., Citation2001). This is a self-administered depression version of the PRIME-MD (Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders). The patient must score every single symptom of the nine DSM symptoms regarding the past 14 days according to not at all (0), several days (1), more than half the days (2) and nearly every day (3). Thus, the instrument can not only be used to get a score representing the severity of depression but also to find a DSM diagnosis. Here, the most used operationalisation for SD is a score between five and 14, but five to nine or ≥ 9 are also used.

In the elderly, the most often used instrument is the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) (Montorio & Izal, Citation1996). This scale is a self-report measure of depression in the elderly. The respondent can answer “yes” or “no,” with each answer indicating depressive complaints being awarded 1 point. Two versions exist: firstly, the 30-item version called the GDS-long form (GDS-L). Secondly, 15 items showing a high correlation with depressive symptoms were chosen from these 30 items for the GDS-short form (GDS-S). However, the most used definition in the trials included is ≥ 16.

Epidemiology

Prevalence

General population

Here, epidemiological studies found are described, with only a few exceptions (Pickett et al., Citation2014; Wyman et al., Citation2020). Two large-scale representative studies examining the life-time resp. the 12-months prevalence of SD could be identified:

Pietrzak et al. (Citation2013) used data from a representative sample of 43,093 adult participants of the NESARC (National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions) interviewed during a so-called wave I of this study, performed in the years 2001 and 2002. The lifetime prevalence of SD in this trial was 11.6%.

Stubbs et al. (Citation2017a) described a 12-month SD prevalence of 2.5% (the respective finding for a brief depression episode was 2.7%, for a depressive episode 6.5%) in a population of 237,952 people. In this publication and others of this group, special attention was paid to the association between depressive symptoms and pain. The prevalence of severe pain in the last 30 days in the just mentioned trial of Stubbs et al. (Citation2017a) across the entire sample was 10.7%, and the mean (SD) pain scores were 23.3 (26.0), 43.0 (26.2), 41.7 (26.8), and 49.9 (26.29) for no depression, subsyndromal depression, brief depressive episode, and depressive episode, respectively, while the prevalence of severe pain for these four conditions was 8.0, 28.2, 20.2, and 34.0%, respectively. Whereas the frequency of depressive episodes increased with pain intensity, this was not the case for brief depressive episodes or for SD. A paper published somewhat earlier (Stubbs et al., Citation2016), with the same approach and the same cohort included, focussed on back pain, showing an odds ratio of 22.21 for SD participants compared to controls. Similar prevalence rates reported by Stubbs et al. (Citation2018) used a very similar sample to explore the association between depression and smoking. The prevalence of current smoking was higher in depressed participants, with odds ratios between 1.36 and 1.49 for SD, brief depressive episodes, and MD compared to people without depression. Also in this sample, Stubbs et al. (Citation2017b) could show that physical health was worse in depressed participants than in controls, also in the SD-group.

Peters et al. (Citation2015) found 3,901 participants with a life-time history of SD in a representative sample of 34,923 participants of the first wave of the NESARC in the United States. Special risk factors for developing MD three years later (diagnosed at the second wave of this trial) were low education, substance use, and younger age. These factors marginally increased the risk of MD.

Topuzoğlu et al. (Citation2015) reported, based on a sample of 3,514 inhabitants of Izmir, Turkey, a 12-month prevalence rate of SD of 4.2% (SD: 0.3), of clinical depression of 8.2% (0.4). Jeuring et al. (Citation2018) looked at the development of the rates of SD and MD over 20 years (1992, 2002, 2012) and found an increase in MD (2.1, 3.9, 3.8%, respectively), which was not present for SD (7.2, 8.7, and 6.2%). Higher socioeconomic and psychosocial conditions are regarded as protective against MD and SD.

Special populations

Diabetes mellitus

Schmitz et al. (Citation2014) described in 1,064 patients with diabetes type 2 that nearly half of the participants suffered from at least one episode of SD. The more episodes of SD were present the higher the risk of poor functioning/impaired health-related quality of life was. Wang et al. (Citation2018) reported a point prevalence for SD of 11.6% in 808 patients hospitalised due to diabetes type 2.

Elderly

On the basis of a representative sample of 10,409 participants being at least 55 years of age, Laborde-Lahoz et al. (Citation2015) reported that 13.8% had a lifetime prevalence of SD (13.7% of MD). Participants with SD had significantly increased odds ratios (OR) for lifetime mood (adjusted odd-ratios 3.65–10.55), anxiety (1.61–2.50), and any personality (1.62) disorders. They also had increased odds of developing new-onset MD (1.44) as well as an anxiety disorder (1.52) from wave 1 to wave 2 (which was performed 2 years later).

In elderly patients, Xiao et al. (Citation2016) investigated 1,068 elderly inhabitants of Shanghai, China, and found a point prevalence of SD of 1.7% (MD: 2.4%) in home care recipients (n = 811). Xiang et al. (Citation2018) found a point prevalence of 38.7% for SD and 13.4% for MD in 811 community-dwelling adults aged 60 and over.

A very interesting study was presented by Sigström et al. (Citation2018). In a population-based sample, 563 participants were investigated at the age of 70, 450 “survivors” at the age of 75 and 79 years. The cumulative 9-year-prevalence rate for SD was 30.9% (for minor depression 27.6, for MD 9.3%). Lee et al. (Citation2013) found practically no differences regarding several demographic parameters between SD and MD patients in a non-representative sample of 315 elderly using community long-term care.

In a population-based sample, Ludvigsson et al. (Citation2016) looked at participants born in 1922 and living in a certain region in Sweden. Of the 650 subjects identified, 496 responded. The authors reported a prevalence rate of 27% for SD (and 6% for MD). 22% of the SD persons received antidepressant treatment compared to only 17% of the MD persons.

Ho et al. (Citation2016) used data collected from the National Mental Health Survey of the Elderly (NMHS-E), which was a nationally representative population-based survey sample of older adults. In 1,092 people, they found a point prevalence rate of 9.0% for SD (and 5.1% for MD).

Looking at a cross-sectional approach on a subgroup of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) being older than 50 years and taking opioids (n = 1,036), Brooks et al. (Citation2019) reported a point prevalence rate for subthreshold depression of 22.8 (for moderate and severe depression of 13.0 and 11.8%).

Wu et al. (2020) found a point prevalence of 11.6% for SD and 5.1% for MD in a population-based cohort study using different catchment areas in 8 different low to middle-income countries including 15,991 people older than 64 years.

Using a similar sample as Wu et al. (Citation2020), but a different definition of SD, Johansson et al. (Citation2019) found a point prevalence of 5.4% for ICD-10 depression and 20.6% for SD in 11,474 older adults. Using the same design, Gonçalves-Pereira et al. (Citation2019) found a point prevalence rate for SD of 18.0 and for ICD-10 depression of 4.4% among 1.405 older people in Southern Portugal.

In 6,640 elderly people in Korea (community-based, random sample), Oh et al. (Citation2020) reported a point prevalence rate of 9.24% for SD, which was 2.4fold higher than that of syndromal depression. The incidence rate of subsyndromal depression was 21.70 per 1,000 person-years.

Vaccaro et al. (Citation2017) estimated a point prevalence of 15.71% (95% confidence interval [C.I.]: 13.70–17.72) for SD and 5.58% (4.31–6.95) for MD in a very carefully performed epidemiological trial in a group of 1,321 elderly people (70–74 years), drawn from the responders of the cross-sectional phase of InveCe.Ab (Invecchiamento Cerebrale in Abbiategrasso, Brain Ageing in Abbiategrasso).

Almeida et al. (Citation2015) published a cross-sectional study of 1,649 community-dwelling men aged at least 80 years. Of these, 14.5% suffered from SD (7.3% had clinically significant depression). Decreased interest in sex and anxiety before sex was associated with SD.

Adolescents

In the trial of Balázs et al. (Citation2013), 12,395 adolescents aged between 14 and 16 years from the Saving and Empowering Young Lives in Europe (SEYLE) study were included. The primary aim of the SEYLE study was to compare the efficacy, cost-effectiveness and cultural adaptability of suicide-prevention strategies in schools (Wasserman et al., Citation2010) in a randomised trial. In each of the 11 participating countries, 1,000 participants from different schools were recruited. No diagnoses were established, and the level of depression (and anxiety) was measured via self-rating scales. The authors found 29.2% of the population to be subthreshold depressive and 10.5% depressed with high comorbidities regarding anxiety and subthreshold anxiety. Functional impairment, measured with the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), was reduced, and suicidality (Paykel Suicide Scale [PSS]) had increased already in the subthreshold depressive group, but even more, pronounced in the depressive group.

On the basis of 2,022 adolescents recruited from eight state-subsidized schools located in the northern part of Santiago, Chile, Crockett et al. (Citation2020) reported a point prevalence of 16.5% for SD and 17.7% for MD. A major risk factor was the female sex.

Philipson et al. (Citation2020) used data drawn from the Uppsala Longitudinal Adolescent Depression Study, a community-based cohort study initiated in Uppsala, Sweden, in the early 1990s. Comprehensive diagnostic assessments were conducted at the age of 16–17 years and in follow-up interviews 15 years later (these results will be reported under “3.2.2 Course”). In 321 adolescents, the authors found 64 with SD.

In a prospective cohort-based study comprising 274 primary care attenders (13–18 years), Gledhill and Garralda (Citation2013) found 25% to be suffering from SD. In a meta-analysis comprising a total of 24 studies (Wesselhoeft et al., Citation2013), the different criteria to operationalise SD were listed (yielding considerable heterogeneity). Regarding epidemiological data, the authors summarised the results of 5 studies reporting estimates of life-time prevalence of SD and MD between 5.3–12.0 resp. 1.1–14.6%. 5 studies reported one-year prevalence rates to be 1.0–20.7 resp. 0.8–13.0%. In 6 out of 12 suited studies comparing prevalence rates for SD and MD, higher prevalence rates for SD were reported. The results regarding risk factors for SD were very heterogeneous, female gender was identified most consistently.

Hill et al. (Citation2014) investigated 1,709 adolescents aged between 14 and 18 years with a mean age of 16.6 (SD: 1.2) years. The participants were randomly selected from nine high schools in Western Oregon. Of these 1,709 adolescents, 424 suffered from SD.

Chronic kidney disease

Shirazian et al. (Citation2016) investigated a sample of 2,500 participants, drawn from data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES). This is a multistage, stratified, clustered probability sample of the US civilian non-institutionalized population conducted in 2-year cycles by the National Centre for Health Statistics (NCHS). These surveys examine disease prevalences and trends over time. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) was defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate of 15–60 ml/min/1.73 m2 or urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio of ≥ 30 mg/g. For the 2,500 participants with CKD, the weighted point prevalence was 21.4% for SD symptoms and 3.1% for severe depressive symptoms. Awareness (of the CKD and resulting consequences) was significantly associated with depressive symptoms.

Visual impaired

In 914 visual-impaired patients attending outpatient low-vision rehabilitation centres in the Netherlands and Flanders, van der Aa et al. (Citation2015a) found a point prevalence of 47.6% for participants suffering either from subthreshold depressive or subthreshold anxiety symptoms.

Course

General population

In the trial of Pietrzak et al. (Citation2013) already reported above, two waves were performed: wave 1 in the years 2001 and 2002, and wave 2 in the years 2004 and 2005. In individuals showing an SD at wave 1, the risk of developing a major depression until wave II was increased (ORs 1.72–2.05) compared to those participants showing no depression. The same was true for dysthymia, social phobia, and generalised anxiety disorder (ORs 1.41–2.92). Among respondents with SD at wave 1, Cluster A and B personality disorders and worse mental health status were associated with an increased likelihood of developing incident major depression at wave 2.

A very interesting and comprehensive meta-analysis in this context was published by Lee et al. (Citation2019). In a systematic literature review, the group identified 16 studies (total n = 67,319) investigating the question of whether the incidence of MD after SD is elevated. The incidence rate ratio (IRR) for people with SD to develop MD was 1.95 (95% C.I.: 1.28–2.97). Subgroup analyses estimated similar IRR for different age groups (youth, adults and elderly) and sample types (community-based and primary care). Sensitivity analyses showed the robustness of the results with regard to different sources of study heterogeneity.

Some reports focussed on the effect of different interventions to lower the conversion rate from SD to MD. Cuijpers et al. (Citation2016) reported in a meta-analysis comprising 5 studies that interpersonal psychotherapy lowers the conversion rate of SD into MD (follow-up time 3–18 months). The odds ratio compared to the control group was 0.30 (95% C.I.: 0.10–0.88). Similar results were described by Reins et al. (Citation2021) who meta-analytically evaluated the results of 7 trials with a total of 2,186 participants for internet-based psychotherapy. Krishna et al. (Citation2013) reported in their review consisting of 4 trials that group psychological interventions in older adults with SD had a significant effect on depressive symptomatology, which is not maintained on follow-up. Buntrock et al. (Citation2016) investigated in a controlled study looking at the effect of a web-based guided self-help intervention whether the conversion rate of SD to MD in a follow-up of 1 year could be changed. After one year, 27% of participants in the intervention group developed MD, compared to 41% in the control group. The same group (Krishna et al., Citation2015) reported on meta-analytical results of 8 trials. These were similar to the first published review with only 4 trials. The authors additionally reported that the conversion rate from SD into MD was not reduced by group psychotherapy. In a controlled clinical trial investigating the effect of a stepped care approach in SD patients with diabetes mellitus type 2 and/or coronary heart disease with a follow-up of 12 months, no difference regarding the conversion rate to MD between the intervention and the control group could be found (Pols et al., Citation2017). This was also true after an observation period of 2 years (Pols et al., Citation2018).

Karsten et al. (Citation2013) used data from the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (N = 1,266, aged 18–65). Linear mixed models were used to identify predictors of functional impairment at baseline, 1- and 2-year follow-up. The authors found a higher functional impairment in participants with SD at baseline. At the follow-up after 1 and 2 years, this functional impairment improved but remained much higher than in controls.

Special populations

Adolescents

In the investigation of Hill et al. (Citation2014) (see above), the participants (mean age: 16.6 years) were seen again after one year, at the age of 24, and at the age of 30 years. 144 of the original sample of 1.709 adolescents developed MD, the most important risk factors for this development were poor friend support and a history of a (comorbid) anxiety or substance use disorder.

Jinnin et al. (Citation2016) screened 2,494 first-year undergraduate students (2,281 responded) from Hiroshima University in Japan with the help of the Beck Depression Inventory (2nd edition, BDI-II). The students were 18 or 19 years old and had not had an MD in the past 12 months. The total group was separated into three subgroups: low symptom group (BDI-II-score ≤ 10), middle symptom group (BDI-II-score between 11 and 17), and high symptom group (BDI-II-score ≥ 18); the latter group was considered to suffer from SD. Originally, the numbers of students belonging to the different classes were 1,918, 276 resp. 87. After contacting and performing other procedures, 68, 57 resp. 66 participants remained. These participants were examined every two months for 1 year. Using different statistical methods (mainly growth mixture modelling [GMM]), three classes could be identified. In the “increasing group” (n = 26), by far the most (n = 22) belonged to the SD group. Three students in the SD group developed MD during the 12-months follow-up.

Gledhill and Garralda (Citation2013) (see above) reported that, after 6 months, 57% of adolescents suffering from SD still showed persistent depressive symptoms and 12% had developed MD. In a 15-years follow-up, Philipson et al. (Citation2020) (see above) found that SD was, in contrast to persistent depressive disorder, not linked to lower income.

Elderly

In an 8-year follow-up of data of 496 very old participants of a prospective cohort study (Ludvigsson et al., Citation2016, see above), Ludvigsson et al. (Citation2019) showed that mortality was increased in a group of MD-participants but not in the SD-group compared to controls. Morbidity, especially activities of daily living and quality-of-life parameters were increased in the MD- and the SD-group compared to controls. Ludvigsson et al. (Citation2018) could show in a similar study that direct costs in people with SD were 1.48-fold higher than in controls.

Zhang et al. (Citation2020) found in 1,188 older people without dementia (455 with mild cognitive impairment [MCI], 733 without MCI), a subgroup of the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI), that SD at baseline was associated with a significant cognitive decline in cognition during the 5 years follow-up. Also, SD participants showed significantly accelerated atrophy in the hippocampus and middle temporal gyrus.

In the already reported trial of Sigström et al. (Citation2018), the cross-sectional prevalence rate for SD (and minor depression) increased over time. If participants had suffered from SD at the age of 70 years, 47.2% had SD at follow-up and 36.1% had MD or minor depression. In this population-based sample, more than half of the participants experienced some degree of depression during their eighth decade of life. Most new episodes of MD occurred in people who were already in a depressive state (SD, minor depression) at baseline. As the authors stated, this could have implications for late-life depression strategies.

In a 10 years follow-up of the already reported trial of Ho et al. (Citation2016), no higher mortality risk for SD could be identified. For MD, higher mortality risk was mainly due to increased cardiovascular and stroke mortality. Based on data from randomly selected 1,000 participants older than 65 years, Jeong et al. (Citation2013) reported that MD was associated with higher mortality in the follow-up phase of this trial, but SD was not.

At the follow-up (average follow-up time of 3.9 years) of the participants of the already reported Wu et al. (2020) trial, it was found for MD (and subthreshold anxiety), but not for SD, that higher risk mortality existed (hazard ratio 1.45, 95% C.I.: 1.24–1.70).

The research group of the already mentioned trial reported by Johansson et al. (Citation2019) conducted a follow-up after four years and found that people with depression and with SD showed a higher risk for the development of dementia (hazard ratio 1.63, 95% C.I.: 1.26–2.11 resp. 1.28, 1.09–1.51).

Visual impaired

van der Aa et al. (Citation2015b) (main results see above, van der Aa et al., Citation2015a) described that in visually impaired participants suffering either from subthreshold depressive or subthreshold anxiety symptoms (47.6% of the sample), 34% recovered from their depressive/anxiety symptoms, while 18% developed a depressive and/or anxiety disorder after a watchful waiting period of 3 months.

Discussion

The main results of this paper are:

SD has a higher prevalence than MD, although a precise estimation is not possible, since different definitions of SD in huge epidemiological trials have been used. All evaluated subgroups are concerned; in the elderly and adolescents, the prevalence seems to be even higher than in the general population. This might be due to the particular, albeit different, stress factors in these age groups.

The impact of SD on quality of life and related parameters are in the range of the respective impact of MD, but in most trials, in which such parameters were evaluated, it was slightly weaker than in MD.

In a considerable number of cases, conversion from SD to MD takes place.

Therapeutic options to treat SD were not the main topic of this paper. However, it should be noted that a group of trials could demonstrate that therapeutic approaches might be helpful for SD and might also be helpful for the prevention of conversion from SD to MD.

Since SD, as shown, is such an important issue having significant implications, early diagnosis and treatment is necessary, but this is currently not taken into account. The importance of subthreshold diagnoses can also be seen in the fact that most suicide attempters have also subthreshold psychiatric disorders (Balázs et al., Citation2000). However, before recommendations for early diagnosis and treatment can be made, a precise definition/description of the disease entity, used by most clinicians and researchers, is needed.

Nevertheless, as another main result of the presented review, it can be stated that such a well-recognized definition does not exist. The opposite is the case: There is a huge heterogeneity of definitions and no consensus can be derived from the published literature.

Before going into a little more detail, it is important to be aware of the field in which such definitions are used:

Clinical issues, i.e., finding patients suffering from SD in a quick and reliable manner to decide whether a treatment is necessary or not.

Research issues, i.e., precisely defining a target population for research.

Regarding clinical issues, the routine application of a scale – even a self-evaluation scale like the PHQ-9 – is not feasible, since clinicians do not use scales in the routine setting. In different settings, however, this is strongly recommended, especially to document long-term changes. In this context, a definition based on the DSM- or ICD-system is needed, since clinicians are familiar with these diagnostic categories. As SD is, like MD, probably an episodic disorder, the same definition as for dysthymia (in ICD-10) could be used in order to describe symptom severity (“A chronic depression of mood […] which is not sufficiently severe […] to justify a diagnosis of severe, moderate, or mild recurrent depressive disorder). However, the duration should be at least 14 days (as is the case for depressive episodes) but shorter than two years (to be distinguished from dysthymia). The disadvantage of this proposal based purely on clinical categories is the overlap with the DSM definition of minor depression (i.e., the total number of symptoms not exceeding 4).

Regarding research issues, the use of scales to define the target population is a very common approach. On the other side, as has been shown in this paper, the most frequently used scales such as CESD or PHQ-9 are not primarily suited to determine symptom severity of SD, because they are more or fewer operationalizations of DSM symptoms. Moreover, these scales are completed by the patient or the caregiver. In our view, it is very astonishing that in not a single identified research paper was an observer-based scale such as the Montgomery-Ӑsberg Depression Rating Scale (MDRS) used to define symptom severity more precisely. This is, of course, related to the nature of most of the trials identified, which is epidemiological research where observer-based scales are due to pragmatic reasons (high number of included patients) not feasible. But such an approach was also not chosen in small-scale trials. Self and observer-rating scales, however, measure in part different symptom dimensions (e.g., Seemüller et al., Citation2022). Another research deficit is that intervention studies have rarely been performed, especially with regard to pharmacological approaches.

To return to the main topic of this paragraph, a clear-cut, well-recognized and generally used definition of SD is lacking. However, the main parameters of such a definition are clear:

No MD (DSM) or depressive episode (ICD) (and also no history of such conditions).

A certain number of symptoms is mandatory, also comprising core symptoms of a depressive episode like depressed mood, anhedonia or loss of energy for a certain time span, e.g., 14 days.

The definition should (for research issues) not only be based on the presence of certain symptoms but should also be based on an additional patient- or caregiver-based instrument in order to enhance the reliability of the number-of-symptoms-based approach; even better would be an observer-(physician/psychologist) rated scale.

For intervention studies, an observer-based instrument seems to be mandatory.

Conclusions

Scrutinising the reported results and other papers in the field, clear conclusions are not possible. Most definitions are arbitrary, the overlap (as stated, e.g., between SD and minor depression) is considerable, and the epidemiological results are, mainly for this reason, highly variable.

Nevertheless, keeping these points in mind and incorporating the main results of our review paper, one proposal for the definition to achieve consensus in this highly important field could be:

Presence of least two DSM depressive symptoms for at least two weeks, one symptom of depressed mood, no MD or minor depression.

PHQ-9 between five and nine and/or CESD at least 16.

MDRS between ten and 18 (for 2 weeks).

Hopefully, this proposal leads to a discussion in the field resulting in much more homogeneous inclusion criteria; otherwise, the so important research in this field is of reduced impact only.

Keypoints section

A clear-cut, well-recognized and generally used definition of SD is lacking. Nevertheless, keeping these points in mind and incorporating the main results of our review paper, one proposal for a definition to achieve consensus in this highly important field could be:

Presence of least two DSM depressive symptoms for at least two weeks, one symptom of depressed mood, no MD or minor depression.

PHQ-9 between five and nine and/or CESD at least 16.

MDRS between ten and 18 (for 2 weeks).

Disclosure statement

Hans-Peter Volz has served as a consultant or on advisory boards for Astra/Zeneca, Eli Lilly, Lundbeck, Pfizer, Schwabe, Janssen, Otsuka, Angelini, and Sage and has served on speakers’ bureaus for Astra/Zeneca, Eli Lilly, Lundbeck, Schwabe, Janssen, Bayer, Recordati, and neuraxpharm. Siegfried Kasper has received grants/research support, consulting fees and/or honoraria within the last three years; grant/research support from Lundbeck; he has served as a consultant or on advisory boards Celegne, IQVIA, Janssen, Lundbeck. Mundipharma, Recordati, Takeda and Schwabe; and he has served on speakers bureaus for Angelini, Aspen Farmaceutica S.A., Janssen, Krka Pharma, Lundbeck, Medichem Pharmaceuticals Inc., Neuraxpharma, OM Pharma, Pierre Fabre, Sanofi, Servier, Schwabe, Sun Pharma. Hans-Jürgen Möller has received grant/research support, consulting fees and honoraria within the last years from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly. GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Cilag, Lundbeck, MSD, Novartis, Organon, Otsuka, Pfizer, Schwabe, Sepracor, Servier, and Wyeth. Erich Seifritz has received honoraria from Schwabe GmbH for educational lectures. He has further received educational grants and consulting fees from Janssen Cilag, Lundbeck, Angelini, Otsuka, Servier, Recordati, Vifor, Sunovion, and Mepha.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Almeida, O., Yeap, B. B., Hankey, G. J., Golledge, J., & Flicker, L. (2015). Association of depression with sexual and daily activities: A community study of octogenarian men. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 23(3), 234–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2013.09.007

- Ayuso-Mateos, J., Nuevo, R., Verdes, E., Naidoo, N., & Chatterji, S. (2010). From depressive symptoms to depressive disorders: The relevance of thresholds. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 196(5), 365–371. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.109.071191

- Backenstrass, M., Frank, A., Joest, K., Hingmann, S., Mundt, C., & Kronmüller, K. (2006). A comparative study of nonspecific depressive symptoms and minor depression regarding functional impairment and associated characteristics in primary care. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 47(1), 35–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2005.04.007

- Balázs, J., Bitter, I., Lecrubier, Y., Csiszér, N., & Ostorharics, G. (2000). Prevalence of subthreshold forms of psychiatric disorders in persons making suicide attempts in Hungary. European Psychiatry, 15(6), 354–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-9338(00)00503-4

- Balázs, J., Miklósi, M., Keresztény, A., Hoven, C. W., Carli, V., Wasserman, C., Apter, A., Bobes, J., Brunner, R., Cosman, D., Cotter, P., Haring, C., Iosue, M., Kaess, M., Kahn, J. P., Keeley, H., Marusic, D., Postuvan, V., Resch, F., … Wasserman, D. (2013). Adolescent subthreshold-depression and anxiety: psychopathology, functional impairment and increased suicide risk. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 54(6), 670–677. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12016

- Baumeister, H., & Morar, V. (2008). The impact of clinical significance criteria on subthreshold depression prevalence rates. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 118(6), 443–450. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01287.x

- Biella, M. M., Borges, M. K., Strauss, J., Mauer, S., Martinelli, J. E., & Aprahamian, I. (2019). Subthreshold depression needs a prime time in old age psychiatry? A narrative review of current evidence. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 15, 2763–2772. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S223640

- Brooks, J. M., Petersen, C., Kelly, S. M., & Reid, M. C. (2019). Likelihood of depressive symptoms in US older adults by prescribed opioid potency: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005-2013. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 34(10), 1481–1489. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5157

- Buntrock, C., Berking, M., Smit, F., Lehr, D., Nobis, S., Riper, H., Cuijpers, P., & Ebert, D. (2017). Preventing depression in adults with subthreshold depression: Health-economic evaluation alongside a pragmatic randomized controlled trial of a web-based intervention. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19(1), e5. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.6587

- Buntrock, C., Ebert, D., Lehr, D., Riper, H., Smit, F., Cuijpers, P., & Berking, M. (2015). Effectiveness of a web-based cognitive behavioural intervention for subthreshold depression: Pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 84(6), 348–358. https://doi.org/10.1159/000438673

- Buntrock, C., Ebert, D. D., Lehr, D., Smit, F., Riper, H., Berking, M., & Cuijpers, P. (2016). Effect of a web-based guided self-help intervention for prevention of major depression in adults with subthreshold depression a randomized clinical trial. Jama, 315(17), 1854–1863. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.4326

- Camacho, A., Larsen, B., McClelland, R. L., Morgan, C., Criqui, M. H., Cushman, M., & Allison, M. A. (2014). Association of subsyndromal and depressive symptoms with inflammatory markers among different ethnic groups: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). Journal of Affective Disorders, 164, 165–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.04.018

- Crockett, M., Martínez, V., & Jiménez-Molina, Á. (2020). Subthreshold depression in adolescence: Gender differences in prevalence, clinical features, and associated factors. Journal of Affective Disorders, 272, 269–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.111

- Cuijpers, P., Donker, T., Weissman, M. M., Ravitz, P., & Cristea, I. A. (2016). Interpersonal psychotherapy for mental health problems: A comprehensive meta-analysis. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 173(7), 680–687. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15091141

- Cuijpers, P., Koole, S. L., van Dijke, A., Roca, M., Li, J., & Reynolds, C. F. (2014). Psychotherapy for subclinical depression: Meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 205(4), 268–274. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.113.138784

- Cuijpers, P., Vogelzangs, N., Twisk, J., Kleiboer, A., Li, J., & Penninx, B. W. (2013). Differential mortality rates in major and subthreshold depression: Meta-analysis of studies that measured both. British Journal of Psychiatry, 202(1), 22–27. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.112.112169

- da Silva Lima, A. F., & de Almeida Fleck, M. P. (2007). Subsyndromal depression: An impact on quality of life? Journal of Affective Disorders, 100(1-3), 163–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2006.10.010

- Ebert, D. D., Buntrock, C., Lehr, D., Smit, F., Riper, H., Baumeister, H., Cuijpers, P., & Berking, M. (2018). Effect of a web-based guided self-help intervention for prevention of major depression in adults with subthreshold depression: A randomized clinical trial. Behavior Therapy, 49(1), 71–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2017.05.004

- Fergusson, D. M., Horwood, L. J., Ridder, E. M., & Beautrais, A. L. (2005). Subthreshold depression in adolescence and mental health outcomes in adulthood. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(1), 66–72. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.1.66

- Forsell, Y. (2007). A three-year follow-up of major depression, dysthymia, minor depression and subsyndromal depression: Results from a population-based study. Depression and Anxiety, 24(1), 62–65. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20231

- Furukawa, T. A., Horikoshi, M., Kawakami, N., Kadota, M., Sasaki, M., Sekiya, Y., Hosogoshi, H., Kashimura, M., Asano, K., Terashima, H., Iwasa, K., Nagasaku, M., & Grothaus, L. C. (2012). Telephone cognitive-behavioral therapy for subthreshold depression and presenteeism in workplace: A randomized controlled trial. PLOS One, 7(4), e35330. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0035330

- Gledhill, J., & Garralda, M. E. (2013). Sub-syndromal depression in adolescents attending primary care: Frequency, clinical features and 6 months outcome. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48(5), 735–744. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-012-0572-z

- Goldney, R. D., Fisher, L. J., Dal, G. E., & Taylor, A. W. (2004). Subsyndromal depression: Prevalence, use of health services and quality of life in an Australian population. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 39(4), 293–298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-004-0745-5

- Gómez-Restrepo, C., Bohórquez, A., Pinto Masis, D., Gil Laverde, J. F. A., Rondón Sepúlveda, M., & Díaz-Granados, N. (2004). The prevalence of and factors associated with depression in Colombia. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública, 16(6), 378–386. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1020-49892004001200003

- Gonçalves-Pereira, M., Prina, A. M., Cardoso, A. M., da Silva, J. A., Prince, M., & Xavier, M. (2019). The prevalence of late-life depression in a Portuguese community sample: A 10/66 Dementia Research Group study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 246, 674–681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.067

- Gosling, J. A., Batterham, P., Ritterband, L., Glozier, N., Thorndike, F., Griffiths, K., Mackinnon, A., & Christensen, H. M. (2018). Online insomnia treatment and the reduction of anxiety symptoms as a secondary outcome in a randomised controlled trial: The role of cognitive-behavioural factors. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 52(12), 1183–1193. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867418772338

- Haller, H., Cramer, H., Lauche, R., Gass, F., & Dobos, G. J. (2014). The prevalence and burden of subthreshold generalized anxiety disorder: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 14, 128. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-128

- Hill, R. M., Pettit, J. W., Lewinsohn, P. M., Seeley, J. R., & Klein, D. N. (2014). Escalation to major depressive disorder among adolescents with subthreshold depressive symptoms: Evidence of distinct subgroups at risk. Journal of Affective Disorders, 158, 133–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.02.011

- Ho, C. S., Jin, A., Nyunt, M. S. Z., Feng, L., & Ng, T. P. (2016). Mortality rates in major and subthreshold depression: 10-year follow-up of a Singaporean population cohort of older adults. Postgraduate Medicine, 7, 642–647.

- Horiuchi, S., Aoki, S., Takagaki, K., & Shoji, F. (2017). Association of perfectionistic and dependent dysfunctional attitudes with subthreshold depression. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 10, 271–275. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S135912

- Jeong, H. G., Lee, J. J., Lee, S. B., Park, J. H., Huh, Y., Han, J. W., Kim, T. H., Chin, H. J., & Kim, K. W. (2013). Role of severity and gender in the association between late-life depression and all-cause mortality. International Psychogeriatrics, 25(4), 677–684. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610212002190

- Jeuring, H. W., Comijs, H. C., Deeg, D. J. H., Stek, M. L., Huisman, M., & Beekman, A. T. F. (2018). Secular trends in the prevalence of major and subthreshold depression among 55–64-year olds over 20 years. Psychological Medicine, 48(11), 1824–1834. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717003324

- Jinnin, R., Okamoto, Y., Takagaki, K., Nishiyama, Y., Yamamura, T., Okamoto, Y., Miyake, Y., Takebayashi, Y., Tanaka, K., Sugiura, Y., Shimoda, H., Kawakami, N., Furukawa, T. A., & Yamawak, S. (2016). Detailed course of depressive symptoms and risk for developing depression in late adolescents with subthreshold depression: A cohort study. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 13, 25–33. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S117846

- Johansson, L., Guerra, M., Prince, M., Hörder, H., Falk, H., Stubbs, B., & Prina, A. M. (2019). Associations between depression, depressive symptoms, and incidence of dementia in Latin America: A 10/66 Dementia Research Group Study. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 69(2), 433–441. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-190148

- Judd, L. L., Rapaport, M. H., Paulus, M. P., & Brown, J. L. (1994). Subsyndromal symptomatic depression: A new mood disorder? J Clin Psychiatry, 55(Supplement), 18–28.

- Kang, T., Eno Louden, J., Ricks, E., & Jones, R. L. L. (2015). Aggression, substance use disorder, and presence of a prior suicide attempt among juvenile offenders with subclinical depression. Law and Human Behavior, 39(6), 593–601. https://doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000145

- Karp, J. F., Zhang, J., Wahed, A. S., Anderson, S., Dew, M. A., Fitzgerald, K., Weiner, D. K., Albert, S., Gildengers, A., Butters, M., & Reynolds, C. F. (2019). Improving patient reported outcomes and preventing depression and anxiety in older adults with knee osteoarthritis: Results of a sequenced multiple assignment randomized trial (SMART) study. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 27(10), 1035–1045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2019.03.011

- Karsten, J., Penninx, W. J. H., Verboom, C. E., Nolen, W. A., & Hartman, C. A. (2013). Course and risk factors of functional impairment in subthreshold depression and anxiety. Depression and Anxiety, 30(4), 386–394. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22021

- Krishna, M., Honagodu, A., Rajendra, R., Sundarachar, R., Lane, S., & Lepping, P. (2013). A systematic review and meta-analysis of group psychotherapy for sub-clinical depression in older adults. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 28(9), 881–888. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.3905

- Krishna, M., Lepping, P., Jones, S., & Lane, S. (2015). Systematic review and meta-analysis of group cognitive behavioural psychotherapy treatment for sub-clinical depression. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 16, 7–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2015.05.043

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

- Laborde‐Lahoz, P., El-Gabalawy, R., Kinley, J., Kirwin, P. D., Sareen, J., & Pietrzak, R. (2015). Subsyndromal depression among older adults in the USA: Prevalence, comorbidity, and risk for new-onset psychiatric disorders in late life. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 30(7), 677–685. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4204

- Lee, M. J., Hasche, L. K., Choi, S., Proctor, E. K., & Morrow-Howell, N. (2013). Comparison of major depressive disorder and subthreshold depression among older adults in community long-term care. Aging & Mental Health, 17(4), 461–469. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2012.747079

- Lee, Y. Y., Stockings, E. A., Harris, M. G., Doi, S. A. R., Page, I. S., Davidson, S. K., & Barendregt, J. J. (2019). The risk of developing major depression among individuals with subthreshold depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Psychological Medicine, 49(1), 92–102. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291718000557

- Loney, P. L., Chambers, L. W., Bennett, K. J., Roberts, J. G., & Stratford, P. W. (1998). Critical appraisal of the health research literature: Prevalence or incidence of a health problem. Chronic Diseases in Canada, 19(4), 170–176.

- Ludvigsson, M., Bernfort, L., Marcusson, J., Wressle, E., & Milberg, A. (2018). Direct costs of very old persons with subsyndromal depression: A 5-year prospective study. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 26(7), 741–751. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2018.03.007

- Ludvigsson, M., Marcusson, J., Wressle, E., & Milberg, A. (2019). Morbidity and mortality in very old individuals with subsyndromal depression: An 8-year prospective study. International Psychogeriatrics, 31(11), 1569–1579. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610219001480

- Ludvigsson, M., Marcusson, J., Wressle, E., & Milberg, A. (2016). Markers of subsyndromal depression in very old persons. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 31(6), 619–628. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4369

- Mokhtar, N. M., Bahrudin, M. F., Ghani, N. A., Rani, R. A., & Ali, R. A. R. (2020). Prevalence of subthreshold depression among constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome patients. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1936. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01936

- Moldovan, R., Cobeanu, O., & David, D. (2013). Cognitive bibliotherapy of mild depressive symptomatology: Randomized clinical trial of efficacy and mechanisms of change. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 20(6), 482–493. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1814

- Montorio, I., & Izal, M. (1996). The geriatric depression scale: A review of its development and utility. International Psychogeriatrics, 8(1), 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1041610296002505

- Morgan, A. J., Jorm, A. F., & Mackinnon, A. J. (2012). Email-based promotion of self-help for subthreshold depression: Mood memos randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 200(5), 412–418. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.111.101394

- Oh, D. J., Han, J. W., Kim, T. H., Kwak, K. P., Kim, B. J., Kim, S. G., Kim, J. L., Moon, S. W., Park, J. H., Ryu, S. H., Youn, J. C., Lee, D. Y., Lee, D. W., Lee, S. B., Lee, J. J., Jhoo, J. H., & Kim, K. W. (2020). Epidemiological characteristics of subsyndromal depression in late life. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 54(2), 150–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867419879242

- Peters, A. T., Shankman, S. A., Deckersbach, T., & West, A. E. (2015). Predictors of first-episode unipolar major depression in individuals with and without sub-threshold depressive symptoms: A prospective, population-based study. Psychiatry Research, 230(2), 150–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2015.08.030

- Philipson, A., Alaie, I., Ssegonja, R., Imberg, H., Copeland, W., Möller, M., Hagberg, L., & Jonsson, U. (2020). Adolescent depression and subsequent earnings across early to middle adulthood: A 25-year longitudinal cohort study. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, e123, 1–10.

- Pickett, Y. R., Ghosh, S., Rohs, A., Kennedy, G. J., Bruce, M. L., & Lyness, J. M. (2014). Healthcare use among older primary care patients with minor depression. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 22(2), 207–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2012.08.018

- Pietrzak, R. H., Kinley, J., Afifi, T. O., Enns, M. W., Fawcett, J., & Sareen, J. (2013). Subsyndromal depression in the United States: Prevalence, course, and risk of incident psychiatric outcomes. Psychological Medicine, 43(7), 1401–1414. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291712002309

- Pols, A. D., Adriaanse, M. C., Van Tulder, M. W., Heymans, M. W., Bosmans, J. E., Van Dijk, S. E., & Van Marwijk, H. W. J. (2018). Two-year effectiveness of a stepped-care depression prevention intervention and predictors of incident depression in primary care patients with diabetes type 2 and/or coronary heart disease and subthreshold depression: Data from the Step-Dep cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open, 8(10), e020412. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020412

- Pols, A. D., Van Dijk, S. E., Bosmans, J. E., Hoekstra, T., Van Marwijk, H. W. J., Van Tulder, M. W., & Adriaanse, M. C. (2017). Effectiveness of a stepped-care intervention to prevent major depression in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and/or coronary heart disease and subthreshold depression: A pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial. PLOS One, 12(8), e0181023. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0181023

- Poppelaars, M., Tak, Y. R., Lichtwarck-Aschoff, A., Engels, R. C. M. E., Lobel, A., Merry, S. N., Lucassen, M. F. G., & Granic, I. (2016). A randomized controlled trial comparing two cognitive-behavioral programs for adolescent girls with subclinical depression: A school-based program (Op Volle Kracht) and a computerized program (SPARX). Behaviour Research and Therapy, 80, 33–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2016.03.005

- Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662167700100306

- Regeer, E. J., Krabbendam, L., de Graaf, R., Have, M., Nolen, W. A., & van Os, J. (2006). A prospective study of the transition rates of subthreshold (hypo)mania and depression in the general population. Psychological Medicine, 36(5), 619–627. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291705006823

- Reins, J. A., Buntrock, C., Zimmermann, J., Grund, S., Harrer, M., Lehr, D., Baumeister, H., Weisel, K., Domhardt, M., Imamura, K., Kawakami, N., Spek, V., Nobis, S., Snoek, F., Cuijpers, P., Klein, J. P., Moritz, S., & Ebert, D. D. (2021). Efficacy and moderators of internet-based interventions in adults with subthreshold depression: An individual participant data meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 90(2), 94–106.

- Rodríguez, M. R., Nuevo, R., Chatterji, S., & Ayuso-Mateos, J. L. (2012). Definitions and factors associated with subthreshold depressive conditions: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 12, 181. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-12-181

- Rucci, P., Gherardi, S., Tansella, M., Piccinelli, M., Berardi, D., Bisoffi, G., Corsino, M. A., & Pini, S. (2003). Subthreshold psychiatric disorders in primary care: Prevalence and associated characteristics. Journal of Affective Disorders, 76(1–3), 171–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00087-3

- Schmitz, N., Gariépy, G., Smith, K. J., Clyde, M., Malla, A., Boyer, R., Strychar, I., Lesage, A., & Wang, J. L. (2014). Recurrent subthreshold depression in type 2 diabetes: An important risk factor for poor health outcome. Diabetes Care, 37(4), 970–978. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc13-1832

- Seemüller, F., Schennach, R., Musil, R., Obermeier, M., Oppolzer, B., Adli, M., Bauer, M., Brieger, P., Laux, G., Gaebel, W., Falkai, P., Riedel, M., & Möller, H. J. (2022). Quantifying Depression: A factorial analytic comparison of three commonly used depression scales (HAMD, MADRS, BDI) in a large sample of depressed inpatients. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience.

- Shirazian, S., Diep, R., Jacobson, A. M., Grant, C. D., Mattana, J., & Calixte, R. (2016). Awareness of chronic kidney disease and depressive symptoms: National health and nutrition examination surveys 2005-2010. American Journal of Nephrology, 44(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1159/000446929

- Sigström, R., Waern, M., Gudmundsson, P., Skoog, I., & Östling, S. (2018). Depressive spectrum states in a population-based cohort of 70-year olds followed over 9 years. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 33(8), 1028–1037. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4888

- Singhal, M., Munivenkatappa, M., Kommu, J. V. S., & Philip, M. (2018). Efficacy of an indicated intervention program for Indian adolescents with subclinical depression. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 33, 99–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2018.03.007

- Stubbs, B., Koyanagi, A., Thompson, T., Veronese, N., Carvalho, A. F., Solomi, M., Mugisha, J., Schofield, P., Cosco, T., Wilson, N., & Vancampfort, D. (2016). The epidemiology of back pain and its relationship with depression, psychosis, anxiety, sleep disturbances, and stress sensitivity: Data from 43 low- and middle-income countries. General Hospital Psychiatry, 43, 63–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2016.09.008

- Stubbs, B., Vancampfort, D., Firth, J., Solmi, M., Siddiqi, N., Smith, L., Carvalho, A. F., & Koyanagi, A. (2018). Association between depression and smoking: A global perspective from 48 low- and middle-income countries. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 103, 142–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.05.018

- Stubbs, B., Vancampfort, D., Veronese, N., Kahl, K. G., Mitchell, A. J., Lin, P.-Y., Tseng, P.-T., Mugisha, J., Solmi, M., Carvalho, A. F., & Koyanagi, A. (2017b). Depression and physical health multimorbidity: Primary data and country-wide meta-analysis of population data from 190 593 people across 43 low- and middle-income countries. Psychological Medicine, 47(12), 2107–2117. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717000551

- Stubbs, B., Vancampfort, D., Veronese, N., Thompson, T., Fornaro, M., Schofield, P., Solmi, M., Mugisha, J., Carvalho, A. F., & Koyanagi, A. (2017a). Depression and pain: Primary data and meta-analysis among 237 952 people across 47 low- and middle-income countries. Psychological Medicine, 47(16), 2906–2917. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717001477

- Takagaki, K., Okamoto, Y., Jinnin, R., Mori, A., Nishiyama, Y., Yamamura, T., Yokoyama, S., Shiota, S., Okamoto, Y., Miyake, Y., Ogata, A., Kunisato, Y., Shimoda, H., Kawakami, N., Furukawa, T. A., & Yamawaki, S. (2018). Enduring effects of a 5-week behavioral activation program for subthreshold depression among late adolescents: An exploratory randomized controlled trial. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 14, 2633–2641. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S172385

- Takagaki, K., Okamoto, Y., Jinnin, R., Mori, A., Nishiyama, Y., Yamamura, T., Yokoyama, S., Shiota, S., Okamoto, Y., Miyake, Y., Ogata, A., Kunisato, Y., Shimoda, H., Kawakami, N., Furukawa, T. A., & Yamawaki, S. (2016). Behavioral activation for late adolescents with subthreshold depression: A randomized controlled trial. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 25(11), 1171–1182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-016-0842-5

- Topuzoğlu, A., Binbay, T., Ulaş, H., Elbi, H., Tanık, F. A., Zağli, N., & Alptekin, K. (2015). The epidemiology of major depressive disorder and subthreshold depression in Izmir, Turkey: Prevalence, socioeconomic differences, impairment and help-seeking. Journal of Affective Disorders, 181, 78–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.04.017

- Vaccaro, R., Borrelli, P., Abbondanza, S., Davin, A., Polito, L., Colombo, M., Vitali, S. F., Villani, S., & Guaita, A. (2017). Subthreshold depression and clinically significant depression in an Italian population of 70-74-year-olds: Prevalence and association with perceptions of self. BioMed Research International, 2017, 3592359. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/3592359

- van der Aa, H. P. A., Hoeben, M., Rainey, L., van Rens, G. H. M. B., Vreeken, H. L., & van Nispen, R. M. A. (2015b). Why visually impaired older adults often do not receive mental health services: The patient's perspective. Qual Life Res, 24(4), 969–978. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-014-0835-0

- van der Aa, H. P. A., Krijnen-de Bruin, E., van Rens, G. H. M. B., Twisk, J. W. R., & van Nispen, R. M. (2015a). Watchful waiting for subthreshold depression and anxiety in visually impaired older adults. Quality of Life Research, 24(12), 2885–2893. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-015-1032-5

- van Zoonen, K., Kleiboer, A., Cuijpers, P., Jan, S., Penninx, B., Verhaak, P., & Beekman, A. (2016). Determinants of attitudes towards professional mental health care, informal help and self-reliance in people with subclinical depression. Social Psychiatry, 62, 84–93.

- Vancampfort, D., Stubbs, B., Firth, J., Hallgren, M., Schuch, F., Lahti, J., Rosenbaum, S., Ward, P. B., Mugisha, J., Carvalho, A. F., & Koyanagi, A. (2017). Physical activity correlates among 24,230 people with depression across 46 low- and middle-income countries. Journal of Affective Disorders, 221, 81–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.06.012

- Volz, H. P., Saliger, J., Kasper, S., Möller, H. J., & Seifritz, E. (2021). Subsyndromal generalized anxiety disorder: operationalization and epidemiology – a systematic literature survey. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, July 27, 1–10, online ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1080/13651501.2021.1941120

- Vulser, H., Paillère Martinot, M.-L., Artiges, E., Miranda, R., Penttilä, J., Grimmer, Y., van Noort, B. M., Stringaris, A., Struve, M., Fadai, T., Kappel, V., Goodman, R., Tzavara, E., Massaad, C., Banaschewski, T., Barker, G. J., Bokde, A. L. W., Bromberg, U., Brühl, R., … Lemaitre, H. (2018). Early variations in white matter microstructure and depression outcoume in adolescents with subthreshold depression. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 175(12), 1255–1264. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17070825

- Vuorilehto, M., Melartin, T., & Isometsä, E. (2005). Depressive disorders in primary care: Recurrent, chronic, and co-morbid. Psychological Medicine, 35(5), 673–682. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291704003770

- Wang, D., Shi, L., Li, L., Guo, X., Li, Y., Guo, X., Li, Y., Xu, Y., Yin, S., Wu, Q., Yang, Y., Zhuang, X., Gai, Y., Li , & Liu, Y. (2018). Subthreshold depression among diabetes patients in Beijing: Cross-sectional associations among sociodemographic, clinical, and behavior factors. Journal of Affective Disorders, 237, 80–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.05.016

- Wasserman, D., Carli, V., Wasserman, C., Apter, A., Balazs, J., Bobes, J., Bracale, R., Brunner, R., Bursztein-Lipsicas, C., Corcoran, P., Cosman, D., Durkee, T., Feldman, D., Gadoros, J., Guillemin, F., Haring, C., Kahn, JP., Kaess, M., Keeley, H., … Hoven, CW. (2010). Saving and Empowering Young Lives in Europe (SEYLE): A randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health, 10, 192. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-192

- Weisel, K. K., Zarski, A. C., Berger, T., Krieger, T., Schaub, M. P., Moser, C. T., Berking, M., Dey, M., Botella, C., Baños, R., Herrero, R., Etchemendy, E., Riper, H., Cuijpers, P., Bolinski, F., Kleiboer, A., Görlich, D., Beecham, J., Jacobi, C., & Ebert, D. D. (2019). Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of guided and unguided internet- and mobile-based indicated transdiagnostic prevention of depression and anxiety (ICare Prevent)): A three-armed randomized controlled trial in four European countries. Internet Interventions, 16, 52–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2018.04.002

- Wesselhoeft, R., Sørensen, M. J., Heiervang, E. R., & Bilenberg, N. (2013). Subthreshold depression in children and adolescents – A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 151(1), 2–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.06.010

- Wong, S. Y. S., Sun, Y. Y., Chan, A. T. Y., Leung, M. K. W., Chao, D. V. K., Li, C. C. K., Chan, K. K. H., Tang, W. K., Mazzucchelli, T., Au, A. M. L., & Yip, B. H. K. (2018). Treating subthreshold depression in primary care: A randomized controlled trial of behavioral activation with mindfulness. Annals of Family Medicine, 16(2), 111–119. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2206

- Wu, Y. T., Kralj, C., Acosta, D., Guerra, M., Huang, Y., Jotheeswaran, A. T., Jimenez-Velasquuez, I. Z., Liu, Z., Libre Rodriguez, J. J., Sala, A., Sosa, A. L., Alkoholy, R., Prince, M., & Prina, A. M. (2020). The association between depression, anxiety, and mortality in older people across eight low‐ and middle‐income countries: Results from the 10/66 cohort study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 35(1), 29-36.

- Wyman, M. F., Jonaitis, E. M., Ward, E. C., Zuelsdorff, M., & Gleason, C. E. (2020). Depressive role impairment and subthreshold depression in older black and white women: Race differences in the clinical significance criterion. International Psychogeriatrics, 32(3), 393–405. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610219001133

- Xiang, X., Leggett, A., Himle, J. A., & Kales, H. C. (2018). Major depression and subthreshold depression among older adults receiving home care. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 26(9), 939–949. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2018.05.001

- Xiao, S., Lewis, M., Mellor, D., McCabe, M., Byrne, L., Wang, T., Wang, J., Zhu, M., Cheng, Y., Yang, C., & Dong, S. (2016). The China longitudinal ageing study: overview of the demographic, psychosocial and cognitive data of the Shanghai sample. Journal of Mental Health, 25(2), 131–136. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2015.1124385

- Xiao, S., Li, J., Tang, M., Chen, W., Bao, F., Wang, H., Wang, Y., Liu, Y., Wang, Y., Yuan, Y., Zuo, X., Chen, Z., Zhang, X., Cui, X., Cui, L., Li, C., Wang, T., Wi, W., & Zhang, M. (2013). Methodology of Chinás national study on the evaluation, early recognition, and treatment of psychological problems in the elderly: The China Longitudinal Aging Study (CLAS). Shanghai Arch Psychiatry, 25, 91–98.

- Zarski, A. C., Berking, M., Reis, D., Lehr, D., Buntrock, C., Schwarzer, R., & Ebert, D. D. (2018). Turning good intentions into actions by using the health action process approach to predict adherence to internet-based depression prevention: Secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(1), e9.20. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.8814

- Zhang, Z., Wei, F., Shen, X. N., Ma, Y. H., Chen, K. L., Dong, Q., Tan, L., & Yu, J. T. (2020). Associations of subsyndromal symptomatic depression with cognitive decline and brain atrophy in elderly individuals without dementia: A longitudinal study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 274, 262–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.097