Abstract

Objective

To describe MDD patients starting antidepressant (AD) treatment by pharmacological approach and identify factors associated with a longer sick leave (SL) duration.

Methods

Retrospective study on IQVIA German Disease Analyser (specialists) and Spanish Longitudinal Patient Database (general practitioners and specialists). MDD patients initiating AD treatment between July 2016–June 2018 were grouped by therapeutic approach (AD monotherapy vs. combination/switch/add-on) and their characteristics were analysed descriptively. Multiple logistic regression models were run to evaluate factors affecting SL duration (i.e., >30 days).

Results

One thousand six hundred and eighty-five patients (monotherapy: 58%; combination/switch/add-on: 42%) met inclusion criteria for Germany, and 1817 for Spain (monotherapy: 83%; combination/switch/add-on: 17%). AD treatment influenced SL duration: combination/switch/add-on patients had a 2-fold and a 4-fold risk of having >30 days of SL than monotherapy patients, respectively in Germany and Spain. Patients with a gap of time between MDD diagnosis and AD treatment initiation had a higher likelihood of experiencing a longer SL both in Germany and Spain (38% higher likelihood and 6-fold risk of having >30 days of SL, respectively).

Conclusions

A careful and timely selection of AD treatment approach at the time of MDD diagnosis may improve functional recovery and help to reduce SL, minimising the socio-economic burden of the disease.

The major depressive disorder has a substantial impact on work absenteeism.

The present study aimed to describe MDD patients starting antidepressant (AD) treatment depending on the pharmacological approach and to identify factors associated with longer sick leave (SL) duration.

Patients receiving AD monotherapy had a lower likelihood of having more than 30 days of sick leave than those receiving AD combination/switch/add-on.

Patients for whom a gap of time between MDD diagnosis and initiation of AD treatment was observed, showed a higher likelihood of having more than 30 days of sick leave.

Because findings from this analysis relied on secondary data, the authors would like to claim the urgency of conducting prospective observational studies that further investigate the effect that different AD therapeutic approaches and timely initiation of treatment might exert on patients’ recovery.

Key points

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a chronic and debilitating mental disease affecting the emotional, intellectual, and social functioning of patients, thus impairing their quality of life (Hemels et al., Citation2004; Hofmann et al., Citation2017). MDD is one of the most common types of mental disorder among adults in Western Countries and its lifetime prevalence are estimated to be around 10% both in Germany and Spain (Kessler & Bromet, Citation2013).

Literature evidence on MDD persistence and age of onset is consistent across countries (Kessler & Bromet, Citation2013): clinical studies showed that among people seeking treatment for MDD, a substantial proportion have a chronic-recurrent course of illness (Hardeveld et al., Citation2010; Torpey & Klein, Citation2008), and disease onset is placed in early adulthood (Kessler & Bromet, Citation2013). In particular, the median age of onset was found to be 28 years in Germany and 30 years in Spain (Kessler & Bromet, Citation2013). The recurrent and chronic course of MDD and its early onset cause this mental disorder to have a substantial impact on work productivity; the cost of the lower employment rate related to chronic depression was estimated to be around 176 billion Euro in 2015 which is equivalent to 1.2% of the Gross Domestic Product across all European countries (OECD/European Union, Citation2018).

In the past years, the contribution of mental disorders to the costs of permanent disability pensions has tripled in Germany, and more than half of them were caused by depression and neurotic disorders (Wedegärtner et al., Citation2007). In 2012, the average work disability period due to a single depressive episode was of 46 days, increasing up to 65 days in case of a recurrent episode (Krauth et al., Citation2014). In Spain, about 80% of the annual cost of depression has been attributed to productivity loss (Salvador-Carulla et al., Citation2011), and the median duration of temporary disability due to depressive disorder was found to be 120 days (Catalina Romero et al., Citation2011). A recent study showed that the average total duration of sick leave (SL) associated with depression, anxiety, or adjustment disorder could reach up to six months in case of late intervention (Marco et al., Citation2020). From this perspective, the impact of MDD on work productivity is an issue of keen interest to insurers and governments (Wedegärtner et al., Citation2007). Further, adopting an individual perspective, it is worth mentioning that work disability can hugely affect the quality of life (QOL), as employment is often an important component of a person’s life (Nieuwenhuijsen, Citation2020). A study conducted in the UK showed that the ability to work was ranked as the sixth most important aspect of QOL by healthy people, whereas health-impaired individuals ranked it as the third most important aspect (Bowling, Citation1995).

Current German and Spanish practice guidelines recommend psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, or a combination of both for the treatment of depressive disorders (DGPPN & ÄZQ, Citation2015; Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality, Citation2014). The effectiveness of antidepressant (AD) treatments and psychotherapy in reducing symptoms associated with depression and anxiety has been confirmed in several studies. In particular, the development of more selective drugs, such as agomelatine, which is a melatonin analogue acting as an MT1/MT2 melatonergic receptors agonist and 5-HT2C antagonist, allowed to overcome limitations of first- and second-generation ADs (e.g., delay in the onset of action, high recurrence, low response rates, and induction of frequent side effects) (Pompili et al., Citation2013). Nonetheless, evidence of the beneficial effect of MDD treatments on an earlier return to work is inconsistent. Authors of a recently updated systematic literature review evaluated the effect of several interventions aimed to facilitate an earlier return to work in MDD patients. The main findings suggest that a combination of a work-directed intervention and a clinical intervention probably reduces SL days, even if, in the long run, this does not lead to more people in the intervention group being at work. Moreover, no evidence supporting a difference in effect on SL of one AD medication compared to another was found. However, the authors also declared that their confidence in results was mostly moderate to low because some findings were based on small numbers of studies and participants (Nieuwenhuijsen, Citation2020). Another systematic review by Lee et al. suggested that AD treatment improves workplace outcomes, including absenteeism, in MDD adult patients (Lee et al., Citation2018). Recently, results of an analysis carried out by the authors of the present paper on data from German general practitioners, showed that several variables affect SL duration in MDD patients starting AD treatment. The choice of AD therapeutic approach and the promptness of treatment initiation were the variables under the physician’s control (i.e., AD therapeutic approach and promptness of treatment initiation) among those considered in the study. It was found that the expected SL days number in patients treated with AD combination/switch/add-on was higher than in patients on AD monotherapy. In addition, the expected number of SL days was higher in patients diagnosed with MDD before the decision to start AD treatment than in those without a previous MDD diagnosis registration (Kasper, Citation2021). The present study involved two cohorts of patients affected by MDD and managed by specialists in Germany, and by general practitioners and specialists in Spain. The main objectives of the analysis were to describe MDD patients starting AD treatment according to the therapeutic approach chosen by the physician (i.e., AD monotherapy vs. AD combination, switch, or add-on) and to identify factors associated with longer SL duration (i.e., >30 days) after starting AD treatment.

Materials and methods

Description of the data source

This was a retrospective observational cohort study using data from electronic medical records (EMRs) captured by IQVIA German Disease Analyser (DA) and Spanish Longitudinal Panel Database (LPD). Both databases provide routine care information from physician consultations obtained from the computer systems of representative samples of practices throughout Germany and Spain (Katz et al., Citation2017; Rathmann et al., Citation2018). Patients’ data are entered directly by physicians and include diagnoses (according to the International Classification of Diseases—ICD, 10th and 9th revision, respectively for Germany and Spain), drug prescriptions (according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification), medical and demographic data. German DA collects data from General Practitioners (GPs) and specialists. In Spain, patients are affiliated with GPs, who act as gatekeepers for accessing specialist care (Garrote, Citation2018). The Spanish LPD database can track patients through GPs and specialists.

Two separate analyses were conducted on German and Spanish data. Information from psychiatrists and neurologists (around 200 physicians providing information on more than 7000 patients) was considered for the analysis of German data, while information from GPs (around 1000 physicians providing information on ∼560,000 patients), psychiatrists and neurologists (more than 150 physicians providing information on ∼29,000 patients) was included for the analysis on Spanish data.

All the analyses presented here were based on anonymized data that didn’t involve any clinical trial on human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors. Being so, review board approval and patient consent were not necessary.

Study design and definitions

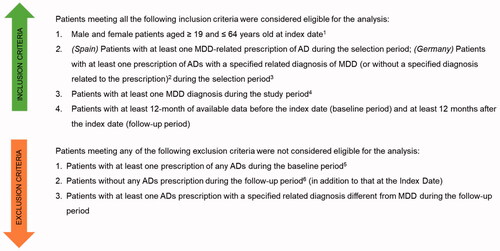

All patients with at least one prescription of AD (defined as a drug belonging to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical class N06A) during the period 01 July 2016–30 June 2018 (‘selection period’) were initially selected. The date of the first AD prescription was defined as the ‘Index Date’. A two-year period, starting 12 months before (‘baseline’) and lasting up to 12 months after (‘follow-up’) the Index Date was observed (‘study period’). MDD diagnoses were identified through the registration of ICD-10 codes F32.xx and/or F33.xx for Germany and ICD-9 codes 296.2x and/or 296.3x and/or 311.xx for Spain. For inclusion/exclusion criteria, please refer to .

Figure 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for inclusion in the study cohorts. 1Index Date: date of first AD prescription during the selection period. 2In the German database, the diagnosis related to the prescription is specified in about 30% of the cases only. 3Selection period: 1 July 2016–30 June 2018. 4Study period: 1 July 2015–30 June 2019. 5Baseline period: 12-month period preceding the Index Date (excluded). 6Follow-up period: 12-month period starting at the Index Date (excluded). AD: antidepressant; MDD: major depressive disorder.

Patients meeting the eligibility criteria were then classified into two different groups based on the AD therapeutic approach at Index Date and during follow-up: AD monotherapy group (AD MONO) included patients having prescriptions of a single AD both at Index Date and during follow-up; AD combination/switch/add-on group (AD COMBI-SW-ADD) included patients having prescriptions of more than one AD at Index Date, as well as patients with prescriptions for a single AD at Index Date, but who received prescriptions for different AD during follow-up.

Information extracted from the databases

The following information was extracted from the databases for the final study cohorts: comorbidities of interest for the present analysis scope (please refer to Supplementary Material for the list of psychiatric and non-psychiatric conditions considered, as well as the ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes used to define their occurrence), recordings of MDD diagnosis during baseline, demographic characteristics at the Index Date, AD prescriptions during follow-up, MDD severity, SL registrations (for any psychiatric/neurologic cause for Germany and MDD-related for Spain) during the study period. Information on MDD severity was derived from ICD-10 codes used by physicians to register the MDD diagnosis closest to the Index Date in Germany. Appendix 2 shows the ICD-10 codes used to define MDD severity. Because ICD-9 codes do not include MDD severity, such information was not considered for Spain.

Outcomes definition and statistical analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics, as well as the number of SL days reported during the 12-month baseline and follow-up periods, were stratified by the AD therapeutic approach. Information on SL, including both the starting and the ending date of each episode, was directly recorded by GPs. For each patient, the duration of the SL episode was summed to get the total number of SL days experienced during the study period. A multiple logistic regression model was implemented to investigate which variables might be associated with the likelihood of having more than 30 SL days during follow-up, i.e., once AD treatment has been initiated. The cut-off of 30 SL days was chosen based on the results of a survey conducted in 2012 by Ipsos Healthcare, which found that the average duration of SL related to an episode of MDD was 30.6 days in Spain (Ipsos Healthcare, Citation2019). For both countries, models accounted for the AD therapeutic approach, presence of baseline MDD, age class, sex, and baseline psychiatric and non-psychiatric comorbidities. The model run on German data also accounted for MDD severity. Since SL notes are usually reported for the employed population only and information on employment status was not available in both databases, a sensitivity analysis focussing on subjects having at least one SL registration during the baseline period (i.e., workers) was performed on a German panel. The same analysis was not carried out on Spanish data due to the small number of patients with (MDD-related) SL registrations during the baseline period. All the analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 and p-values lower than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Study population

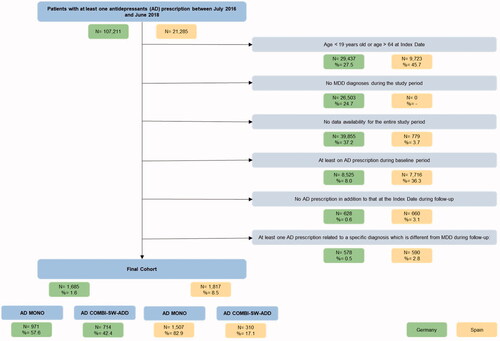

Data from 107,211 patients with at least one AD prescription during the selection period were captured from the IQVIA German DA database. A final cohort of 1685 patients was defined according to eligibility criteria. AD MONO and AD COMBI-SW-ADD patients accounted for 57.6% and 42.4% of the cohort, respectively (). For IQVIA Spanish LPD, data from 21,285 patients with at least one AD prescription during the selection period were captured. According to eligibility criteria, the Spanish final cohort included 1817 patients: 82.9% of them were classified as AD MONO, and 17.1% as AD COMBI-SW-ADD ().

Figure 2. Attrition of study sample. AD: antidepressant; MDD: major depressive disorder; AD MONO: patients who had prescriptions of a single AD both at Index Date and during follow-up; AD COMBI-SW-ADD: patients who had a prescription of more than one AD at Index Date, and patients who had prescriptions of a single AD at Index Date, but received prescriptions of different AD during follow-up.

Characteristics of study patients

No significant age differences were identified, neither between AD therapeutic approach groups nor between countries, with an overall mean age of ∼48 years (). Women were consistently more numerous than men and accounted for 59.5 and 66.4% of the German and Spanish cohort, respectively. The comparison between AD therapeutic approach groups revealed a higher proportion of females among AD COMBI-SW-ADD patients in Germany, while the opposite occurred in Spain. The most frequently reported psychiatric comorbidities were anxiety, headache/migraine, substance abuse disorder, and neuropathic pain. No particular trend did emerge from the comparison between AD therapeutic approaches in Germany, while slightly higher proportions of patients with psychiatric comorbidities were observed for the AD MONO group in Spain. It is worth mentioning that because Germany it was included only data coming from specialists, non-psychiatric conditions were reported for a minority of patients. Muscular skeletal diseases were the most common non-psychiatric conditions in both countries. The comparison between AD therapeutic approaches in Spain showed higher proportions of patients with non-psychiatric comorbidities for the AD MONO group (). Patients who had an MDD diagnosis during baseline, thus before starting AD treatment, accounted for 28.0 and 21.3% of the German and Spanish cohort, respectively. However, while the proportion of patients with a previous MDD diagnosis was higher for the AD MONO group in Germany, the opposite occurred in Spain (). Around half of the German patients were classified as having moderate MDD, 6% had mild MDD, and the comparison between AD therapeutic approaches showed a higher proportion of patients with moderate-to-severe MDD for the AD COMBI-SW-ADD group (69.2 vs. 62.4%) ().

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of major depressive disorder (MDD) patients by antidepressant (AD) therapeutic approach.

Sick leave days registrations throughout the study period by AD therapeutic approach

The mean number of SL days during the baseline period for the AD MONO and AD COMBI-SW-ADD group was 11.5 and 15.4 days, respectively in Germany, and 0.7 and 2.0 days in Spain. After Index Date (i.e., starting therapy) the mean number of SL days increased for both AD MONO and AD COMBI-SW-ADD groups, but the follow-up vs. baseline differences was more marked for the latter group. Indeed, the mean number of SL days during follow-up reached 23.7 and 40.3 days, respectively for AD MONO and AD COMBI-SW-ADD in Germany, and 3.5 and 11.8 days in Spain (data not shown).

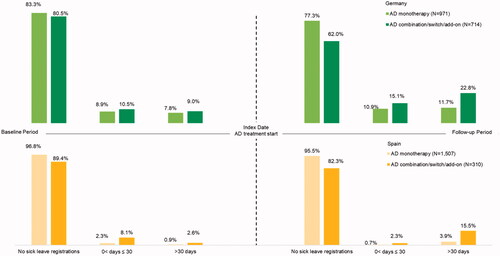

represents the stratification of patients by AD therapeutic approach and number of SL days, before and after the start of treatment, for Germany and Spain. The proportion of patients with more than 30 days of SL was lower for the AD MONO group both during baseline and follow-up, but differences between AD treatment approach groups were larger during follow-up ().

Predictors of sick leave days experience during follow-up

According to multiple logistic models, the AD therapeutic approach and the presence of a time gap between MDD diagnosis and the start of AD treatment were the only variables significantly associated with the likelihood of experiencing more than 30 days of SL during follow-up. German and Spanish AD COMBI-SW-ADD patients had a 2.2- and a 4.4-folds likelihood of having more than 30 days of SL than AD MONO patients, respectively. German patients for whom it was observed a time gap between MDD diagnosis and the start of AD treatment showed a 38% higher likelihood of having more than 30 days of SL compared to those without MDD diagnoses registrations before AD treatment. Analogously, the likelihood of experiencing more than 30 days of SL for Spanish patients with a time gap between diagnosis and the start of treatment was 6.1-folds that of patients without previous diagnoses (). The sensitivity analysis performed on the subgroup of 311 German patients with at least one SL registration during the baseline period confirmed results from the main analysis on the AD therapeutic approach. No statistically significant associations were found for all the other covariates included in the model (data not shown).

Table 2. Results from the multiple logistic regression model estimate the likelihood of having more than 30 days of sick leave during the follow-up period.

Discussion

The objectives of this study were to describe patients affected by MDD and managed by physicians with different AD therapeutic approaches (either AD monotherapy or AD combination, switch or add-on), and to identify factors associated with longer SL duration (i.e., >30 days) after starting AD treatment.

Results from the analyses on both German and Spanish data revealed that (1) patients receiving AD monotherapy had a lower likelihood of having more than 30 days of sick leave than those receiving AD combination/switch/add-on; (2) patients for whom a gap of time between MDD diagnosis and initiation of AD treatment was observed, showed a higher likelihood of having more than 30 days of sick leave.

Monotherapy was the most common treatment approach when an AD treatment was started in patients diagnosed with MDD in both countries. However, the proportion of patients who received AD-COMBI-SW-ADD was much higher in Germany where data came from psychiatrists and neurologists, compared to Spain (42.4 vs. 17.1%), where data came from both GPs and specialists. This data is consistent with previous findings which showed that psychiatrists prescribe ADs combination more frequently than GPs (Lapeyre-Mestre et al., Citation1998; McManus et al., Citation2001, Citation2003). Age and sex distributions did not differ between countries, and little variations were found when comparing demographic characteristics between AD treatment groups. Furthermore, the predominance of female sex found by the present analysis is in line with the 2017 World Health Organisation (WHO) report on ‘Depression and other common mental disorders’, and the same is for findings on age, which showed one-third of the patients being 55–64 years old (WHO, Citation2017). The proportion of patients with psychiatric comorbidities described in the present study was generally low. Focussing on anxiety, which was the most frequently reported condition, the percentage of patients was lower compared to that reported by Freytag et al., in particular when looking at German data (5.5 vs. 26.4%) (Freytag et al., Citation2017). However, patients who were receiving AD for other diagnoses were excluded from the present study, and this may have led to the exclusion of some patients with comorbid psychiatric disorders. No differences were found between AD treatment groups in Germany, while a slightly higher proportion of subjects affected by anxiety was observed for AD MONO compared to the AD COMBI-SW-ADD group in Spain. The distribution of German patients by MDD severity, based on ICD-10 codes, showed a higher proportion of moderate-to-severe MDD than that reported by Freytag et al. (Citation2017), and by the previous analysis conducted by the authors (Kasper, Citation2021). However, in both cases, findings relied on GPs data, thus it cannot be excluded that differences observed could reflect a higher severity of MDD in patients treated by specialists. On the other hand, the proportion of patients with moderate MDD was absolutely comparable to that described by Bretschneider et al., who conducted a general population survey on adult patients younger than 65 years, and assessed severity based on the WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview (Bretschneider et al., Citation2018). The comparison of MDD severity distribution between AD treatment groups in the present study showed a slightly higher proportion of severe MDD among patients receiving AD COMBI-SW-ADD, even if differences were not remarkable.

Results from the descriptive analysis of SL revealed a similar trend in both countries, with a higher number of SL days for the AD COMBI-SW-ADD group throughout the entire study period. However, differences between AD treatment approach groups became much more evident during follow-up, thus after AD treatment initiation. Our data showed that patients treated with AD-MONO or AD-COMBI-SW-ADD had similar characteristics at baseline, as already seen in the previous analysis (Kasper, Citation2021), and, in the absence of other insights that could help to explain the choice of the therapeutic approach, we could similarly argue that patients who received a combination, an add-on or switched to a different AD during follow-up received an ineffective or inappropriate treatment at the initiation. This may have required subsequent treatment adjustments, which, in turn, may have led to potential delays in response and an increase in SL days. In light of the above results, which reinforce findings from the previous analysis (Kasper, Citation2021), it should be underlined the important of selecting AD treatments based on specific patients’ needs and clinical characteristics.

Results from the descriptive analysis of SL days were confirmed by the multiple logistic regression models, which showed that AD COMBI-SW-ADD patients had a higher probability of having more than 30 days of SL during follow-up compared to AD MONO patients. Except for the recently published analysis by Kasper et al., which, consistently with the present one, found a higher expected number of SL days in AD COMBI-SW-ADD patients (Kasper, Citation2021), previous studies attempting to estimate the effect of AD treatments on SL mainly focussed on AD classes or molecules (Gasse et al., Citation2013; Kennedy et al., Citation2016; Wang et al., Citation2015; Winkler et al., Citation2007), rather than AD treatment approach. A study by Dewa et al. reported that as MDD management became more complex (i.e., switched medication, more than one prescription, two prescriptions of different AD), the likelihood of return to work reduced (Dewa et al., Citation2003). The latter result is in line with findings from the present study, which showed a better outcome in terms of SL being associated with the AD MONO approach. Results from the multiple logistic regression models also showed that the presence of an MDD diagnosis before starting AD treatment, indicating a time gap between diagnosis and treatment initiation, was a condition that, together with the AD treatment approach, affected SL duration after AD treatment has started. This finding, consistent with results from the previous analysis (Kasper, Citation2021), seems to reinforce the idea that promptness of AD treatment initiation might have a positive effect on patients’ working lives. Finally, the present analysis did not find further statistically significant associations between the variables considered and the likelihood of a longer SL duration. However, it is worth mentioning that evidence of the influence of older age, MDD severity, and comorbidities on slower return to work has been previously reported (Ervasti et al., Citation2017).

This study was based on data coming from a German cohort of patients followed by specialists and a Spanish cohort of patients co-treated by GPs and specialists. The opportunity to take advantage of two heterogeneous data sources is a very important strength of the present study. Using specialists’ data from the IQVIA German DA, and GPs and specialists’ data from the IQVIA Spanish LPD, allowed us to gain insights from two different perspectives, as well as from two different countries. The combined evaluation of findings from the two sources of real-world data gave a more comprehensive overview of the management of patients affected by MDD and initiating AD treatment, and on factors that might affect SL course in such patients. That said, the agreement of the main results coming from the two cohorts gives extreme robustness to findings emerging from these analyses, which also agrees with results from the previous one (Kasper, Citation2021). However, the present study also had some limitations related to the data source and analytical approaches which are typical of real-world evidence studies. SL registrations in the German IQVIA DA® database did not report the underlying reason for the request. Therefore, it is not possible to know whether the absence from work was specifically due to MDD or not. However, since SL requests were recorded by psychiatrists and neurologists for patients affected by MDD and receiving AD treatments, it is believed that requests were likely related to MDD. Furthermore, in the German IQVIA DA database, treatment prescriptions are not always linked to a specific diagnosis. The strategy to mitigate this limitation was to include patients with at least one MDD diagnosis during the study period while excluding patients receiving ADs to treat conditions other than MDD during follow-up. In both databases, it is not possible to identify employed populations. Therefore, it was decided to perform a sensitivity analysis on the subgroup of patients who had at least one SL registration during baseline. Findings from the sensitivity analysis confirmed the influence of the AD treatment approach on SL duration in Germany. Unfortunately, the same analysis was not carried out on Spanish data due to the low number of patients with MDD-related SL requests during baseline. Both German IQVIA® DA and Spanish LPD databases do not capture information on psychotherapy, which is recommended by practice guidelines (DGPPN & ÄZQ, Citation2015; Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality, Citation2014). However, the present study focussed on the pharmacological approach, thus authors believe that the exclusion of patients potentially receiving psychotherapy as monotherapy did not affect the results’ interpretation. On the other hand, considering the similarity of patients’ characteristics between the AD therapeutic approach groups, there is no reason to argue that physicians’ habits in prescribing psychotherapy may differ between the two groups of patients. In addition, data on patients’ exposure to study treatments were obtained from prescription records, assuming that all registered prescriptions were taken. However, although this should be taken into consideration when interpreting the study results, it has already been shown that data on prescription rates and volumes, such as those obtained from the IQVIA German DA and Spanish LPD, are consistent with those measured by data sources providing information on dispensed medications (Levi et al., Citation2016). Dichotomisation of the variable accounting for the number of SL days might have caused an increase in the probability of observing associations from the logistic regression model and might have led to an underestimation of the extent of variation in outcome between groups (Altman & Royston, Citation2006). However, dichotomisation was necessary because of the non-normal distribution of the number of SL days. Finally, it is worth mentioning the possibility that there were still underlying patient characteristics or behaviours that were not tracked or controlled, which might have influenced both the AD treatment approach adopted by physicians and SL duration.

Conclusion

Data of the present analysis, which agrees with findings recently published by the authors and relies on German GPs’ data (Kasper, Citation2021), showed no differences in baseline characteristics between patients receiving antidepressant monotherapy or antidepressant combination/switch/add-on therapy. This seems to further reinforce the idea that no particular reasons were driving the initial antidepressant therapeutic approach, that was found to be associated with SL duration. This finding suggests that a patient-tailored approach may improve functional recovery and help reduce the socio-economic burden of the disease. Another factor significantly affecting SL duration was the promptness of starting antidepressant treatment when the major depressive disorder is diagnosed. The sensitivity analysis did not confirm the latter result however, it is worth mentioning that (1) the sample on whom the sensitivity analysis was run was very small and (2) a higher expected number of SL days in patients for whom a time gap was observed between the MDD diagnosis and AD treatment initiation was reported by the previous analysis on German GPs data (Kasper, Citation2021). These findings relied on secondary data, and, for this reason, they have intrinsic limitations and can’t be considered confirmatory. The nature of this study is explorative and findings should be considered as a propaedeutic for the planning of future studies rather than conclusive. However, considering the agreement observed, the authors would like to claim the urgency of further investigation into the effect that different AD therapeutic approaches and timely initiation of treatment might exert on patients’ recovery by conducting prospective observational studies.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (21.1 KB)Acknowledgments

Annalisa Bonelli, Alessandro Comandini, Giorgio Di Dato and Valeria Pegoraro were involved in the conception and design of the study. Valeria Pegoraro was involved in the data analysis and drafting of the paper. Siegfried Kasper, Diego Palao, Miquel Roca, and Hans-Peter Volz were responsible for the conception and design of the study, as well as for clinical validation of the study and review of the manuscript. All the authors were involved in data interpretation and critically reviewed the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure statement

This study was funded by Angelini Pharma S.p.A. Annalisa Bonelli, Agnese Cattaneo, Alessandro Comandini, and Giorgio Di Dato are employees of Angelini Pharma S.p.A. Franca Heiman and Valeria Pegoraro are employees of IQVIA. Miquel Roca received research funds or grants from Angelini, Janssen, Lundbeck, and Pfizer. Siegfried Kasper received grants/research support, consulting fees, and/or honoraria within the last three years from Angelini, AOP Orphan Pharmaceuticals AG, Celgene GmbH, Janssen-Cilag Pharma GmbH, KRKA-Pharma, Lundbeck A/S, Mundipharma, Neuraxpharm, Pfizer, Sage, Sanofi, Schwabe, Servier, Shire, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma Co. Ltd., Sun Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd., and Takeda. Hans-Peter Volz received grants/research support, consulting fees, and/or honoraria within the last three years from Lundbeck, Pfizer, Schwabe, Bayer, Janssen-Cilag, Neuraxpharm, Recordati, AstraZeneca, Gilead, Servier, Otsuka, Recordati. Diego Palao has received grants and also served as a consultant or advisor for Angelini, Janssen, Lundbeck, and Servier.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Altman, D. G., & Royston, P. (2006). The cost of dichotomising continuous variables. BMJ, 332(7549), 1080. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7549.1080

- Bowling, A. (1995). What things are important in people’s lives? A survey of the public’s judgements to inform scales of health related quality of life. Social Science & Medicine, 41(10), 1447–1462. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(95)00113-l

- Bretschneider, J., Janitza, S., Jacobi, F., Thom, J., Hapke, U., Kurth, T., & Maske, U. E. (2018). Time trends in depression prevalence and health-related correlates: Results from population-based surveys in Germany 1997–1999 vs. 2009–2012. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 394. doi:10.1186/s12888-018-1973-7

- Catalina Romero, C., Cabrera Sierra, M., Sainz Gutiérrez, J. C., Barrenechea Albarrán, J. L., Madrid Conesa, A., & Calvo Bonacho, E. (2011). Variables moduladoras de la discapacidad asociada al trastorno depresivo. Revista de Calidad Asistencial, 26(1), 39–46. doi:10.1016/j.cali.2010.11.006

- Dewa, C. S., Hoch, J. S., Lin, E., Paterson, M., & Goering, P. (2003). Pattern of antidepressant use and duration of depression-related absence from work. British Journal of Psychiatry, 183(6), 507–513. doi:10.1192/bjp.183.6.507

- Ervasti, J., Joensuu, M., Pentti, J., Oksanen, T., Ahola, K., Vahtera, J., Kivimäki, M., & Virtanen, M. (2017). Prognostic factors for return to work after depression-related work disability: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 95, 28–36. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.07.024

- Freytag, A., Krause, M., Lehmann, T., Schulz, S., Wolf, F., Biermann, J., Wasem, J., & Gensichen, J. (2017). Depression management within GP-centered health care — A case-control study based on claims data. General Hospital Psychiatry, 45, 91–98. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2016.12.008

- Garrote, J. (2018). The primary health care situation in Spain. Organizacion Medical Collegial de Espana. Consejo General de Colegios Oficiales de Medicos. World Medical Journal, 64, 15-19.

- Gasse, C., Petersen, L., Chollet, J., & Saragoussi, D. (2013). Pattern and predictors of sick leave among users of antidepressants: A Danish retrospective register-based cohort study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 151(3), 959–966. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2013.08.015

- Hardeveld, F., Spijker, J., De Graaf, R., Nolen, W. A., & Beekman, A. T. F. (2010). Prevalence and predictors of recurrence of major depressive disorder in the adult population. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 122(3), 184–191. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01519.x

- Hemels, M. E. H., Kasper, S., Walter, E., & Einarson, T. R. (2004). Cost-effectiveness analysis of escitalopram: A new SSRI in the first-line treatment of major depressive disorder in Austria. Current Medical Research and Opinion., 20(6), 869–878. doi:10.1185/030079904125003737

- Hofmann, S. G., Curtiss, J., Carpenter, J. K., & Kind, S. (2017). Effect of treatments for depression on quality of life: A meta-analysis. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 46(4), 265–286. doi:10.1080/16506073.2017.1304445

- Ipsos Healthcare (2019). IDEA: Impact of depression at work in Europe audit. Retrieved from https://www.europeandepressionday.eu/2019/04/11/idea/

- Kasper, S. (2021). Predictors of sick leave days in patients affected by major depressive disorder receiving antidepressant treatment in general practice setting in Germany. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, 25(1), 1–10. doi:10.1080/13651501.2021.1895524

- Katz, P., Pegoraro, V., & Liedgens, H. (2017). Characteristics, resource utilization and safety profile of patients prescribed with neuropathic pain treatments: A real-world evidence study on general practices in Europe – The role of the lidocaine 5% medicated plaster. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 33(8), 1481–1489. doi:10.1080/03007995.2017.1335191

- Kennedy, S. H., Avedisova, A., Belaïdi, C., Picarel-Blanchot, F., & de Bodinat, C. (2016). Sustained efficacy of agomelatine 10 mg, 25 mg, and 25–50 mg on depressive symptoms and functional outcomes in patients with major depressive disorder. A placebo-controlled study over 6 months. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 26(2), 378–389. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2015.09.006

- Kessler, R. C., & Bromet, E. J. (2013). The epidemiology of depression across cultures. Annual Review of Public Health, 34, 119–138. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114409

- Krauth, C., Stahmeyer, J. T., Petersen, J. J., Freytag, A., Gerlach, F. M., & Gensichen, J. (2014). Resource utilisation and costs of depressive patients in Germany: Results from the primary care monitoring for depressive patients trial. Depression Research and Treatment, 2014(2014), 730891.

- Lapeyre-Mestre, M., Desboeuf, K., Aptel, I., Chale, J.-J., & Montastruc, J.-L. (1998). A comparative survey of antidepressant drug prescribing habits of general practitioners and psychiatrists. Clinical Drug Investigation, 16, 53–61. doi:10.2165/00044011-199816010-00007

- Lee, Y., Rosenblat, J. D., Lee, JGoo., Carmona, N. E., Subramaniapillai, M., Shekotikhina, M., Mansur, R. B., Brietzke, E., Lee, J.-H., Ho, R. C., Yim, S. J., & McIntyre, R. S. (2018). Efficacy of antidepressants on measures of workplace functioning in major depressive disorder: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 227, 406–415. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.003

- Levi, M., Pasqua, A., Cricelli, I., Cricelli, C., Piccinni, C., Parretti, D., & Lapi, F. (2016). Patient adherence to olmesartan/amlodipine combinations: Fixed versus extemporaneous combinations. Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy, 22(3), 255–262. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2016.22.3.255

- Marco, J. H., Alonso, S., & Andani, J. (2020). Early intervention with cognitive behavioral therapy reduces sick leave duration in people with adjustment, anxiety and depressive disorders. Journal of Mental Health, 29(3), 247–255. doi:10.1080/09638237.2018.1521937

- McManus, P., Mant, A., Mitchell, P., Birkett, D., & Dudley, J. (2001). Co-prescribing of SSRIs and TCAs in Australia: How often does it occur and who is doing it?: Co-prescribing of SSRIs and TCAs. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 51(1), 93–98. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2125.2001.01319.x

- McManus, P., Mant, A., Mitchell, P., Britt, H., & Dudley, J. (2003). Use of antidepressants by general practitioners and psychiatrists in Australia. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 37(2), 184–189. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1614.2003.01132.x

- Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality (2014). Clinical practice guideline on the management of depression in adults. Clinical practice guidelines in the Spanish NHS.

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie, Psychotherapie und Nervenheilkunde (DGPPN), & Ärztliches Zentrum Für Qualität In Der Medizin (ÄZQ) (2015). S3-Leitlinie/Nationale VersorgungsLeitlinie Unipolare Depression – Langfassung, 2. Auflage. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie, Psychotherapie und Nervenheilkunde (DGPPN); Bundesärztekammer (BÄK); Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung (KBV); Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (AWMF). doi:10.6101/AZQ/000364

- Nieuwenhuijsen, K. (2020). Interventions to improve occupational health in depressed people. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 4(2), CD006237. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006237.pub4

- OECD/European Union (2018). Health at a glance: Europe 2018: State of health in the EU cycle. OECD Publishing. doi:10.1787/health_glance_eur-2018-en

- Pompili, M., Serafini, G., Innamorati, M., Venturini, P., Fusar-Poli, P., Sher, L., Amore, M., & Girardi, P. (2013). Agomelatine, a novel intriguing antidepressant option enhancing neuroplasticity: A critical review. The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry, 14(6), 412–431. doi:10.3109/15622975.2013.765593

- Rathmann, W., Bongaerts, B., Carius, H.-J., Kruppert, S., & Kostev, K. (2018). Basic characteristics and representativeness of the German Disease Analyzer database. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 56(10), 459–466. doi:10.5414/CP203320

- Salvador-Carulla, L., Bendeck, M., Fernández, A., Alberti, C., Sabes-Figuera, R., Molina, C., & Knapp, M. (2011). Costs of depression in Catalonia (Spain). Journal of Affective Disorders, 132(1–2), 130–138. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2011.02.019

- Torpey, D. C., & Klein, D. N. (2008). Chronic depression: update on classification and treatment. Current Psychiatry Reports, 10(6), 458–464. doi:10.1007/s11920-008-0074-6

- Wang, G., Gislum, M., Filippov, G., & Montgomery, S. (2015). Comparison of vortioxetine versus venlafaxine XR in adults in Asia with major depressive disorder: A randomized, double-blind study. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 31(4), 785–794. doi:10.1185/03007995.2015.1014028

- Wedegärtner, F., Sittaro, N.-A., Emrich, H. M., & Dietrich, D. E. [(2007). Disability caused by affective disorders–What do the Federal German Health report data teach us? Psychiatrische Praxis, 34 Suppl 3, S252–S255. doi:10.1055/s-2007-970976

- Winkler, D., Pjrek, E., Moser, U., & Kasper, S. (2007). Escitalopram in a working population: Results from an observational study of 2378 outpatients in Austria. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental, 22(4), 245–251. doi:10.1002/hup.839

- World Health Organization (2017). Depression and other common mental disorders global health estimates.