ABSTRACT

To what extent is regulation associated with supply in the platform economy (PE)? We address this research question by analyzing the relationship between the strictness of rules/laws in 59 U.S. cities and the number of short-stay accommodation offerings. We find that the stricter regulation is, the higher the supply in these platforms. We also investigate how the presence (or lack thereof) of money transactions in the platform affects this relationship. We discover that the presence of money transactions in these platforms negatively moderates the positive relationship between regulation strictness and the supply of short-stay accommodations. This paper contributes to the literature by investigating how aggregate supply in the PE is affected by legal uncertainties, thereby joining the debate on how digital platforms are reforming labor practices in major parts of the economy and industrial value chains.

1. Introduction

“We’re not against regulation. We want to be regulated because to regulate us would be to recognize us … ” The issue, he said, is that “There are laws for people and there are laws for business, but you are a new category, a third category, people as businesses. As hosts, you are micro-entrepreneurs and there are no laws written for micro-entrepreneurs.” – Airbnb CEO Brian Chesky

“New Yorkers who make money on the side by offering their apartments for short-term rental through Airbnb have declared themselves confused, unhappy and nervous. “I’m not sure if it’s legal or not,” said Sierra Kraft, 30, who works for a nonprofit accreditation service and, via Airbnb, rents out her tiny one-bedroom apartment in an old tenement building on the Lower East Side in Manhattan … ” – The Guardian

These anecdotes illustrate how the absence of the regulation – defined as a set of rules designed to control and govern conduct by an authority that may enforce the imposition of penalties (Joerges and Vos Citation1999) – is related to the growth of digital platforms. This relation also directly expands to include the supply of goods and services in these platforms: the less the platform grows, the fewer people who are willing to participate in them (Rochet and Tirole Citation2003). In this paper, we aim to understand to what extent the presence of regulation is associated with supply in digital platforms. Supplier users provide the goods/services to platforms and are pervasive in the platform economy (PE).Footnote1 There is an emerging debate on whether regulation is necessary to encourage people to participate in the PE (Sundararajan Citation2016; Ranchordás Citation2015). Thus, it is important, practically and theoretically, to study whether and to what extent regulation strictness encourages (or discourages) supply in digital platforms. The strictness (or lack thereof) of a robust legal framework could discourage people from supplying the PE, particularly in the accommodation/housing market, which is typically heavily regulated (Malpezzi Citation1996).

Furthermore, some digital platforms are based on the concept of free accommodation, such as Couchsurfing, while others, such as Airbnb, require payment. It is not yet clear whether regulation is related to both in the same way. Some scholars argue that non-monetary benefits, such as hosts socializing with their guest, are the main driver of supply in the PE (Botsman and Rogers Citation2011; Tussyadiah and Pesonen Citation2016). Others reveal that the sharing of accommodation is purely economically driven (Böcker and Meelen Citation2016). However, a quantitative investigation into the supply in the PE that considers regulation strictness as an important variable in the formation of supply is still mostly absent. Aggregate supply in the PE could be stagnant because regulation does not specify whether engaging in the PE is legal or illegal (Franzetti Citation2015).

We build on previous work on how supply emerges in the PE (Eisenmann, Parker, and Van Alstyne Citation2006; Boudreau Citation2010; Hagiu and Wright Citation2015) and insert regulation as a variable that influences the growth of short-stay accommodation platforms. Our research question is as follows: Does regulation stimulate supply in short-stay accommodation platforms (both money-based and free)? To answer this question, we quantitatively analyze the relationship between the strictness of regulation and the quantity of PE offerings in a United States (U.S.) city. Our argument in this paper is that the fewer rules there are, the more uncertainty there is regarding whether it is legal or not to participate and thus the less people will engage in the PE. We use the RoomscoreFootnote2 index created by the R Street Institute (a nonprofit public policy research organization with an orientation towards anti-regulation and pro free markets) to gauge the strictness of short-term rental regulation in 59 U.S. cities. With various levels of regulation strictness, we compare the amount of PE supply for both money-based and free platforms across these cities. We capture money-based and free short-stay accommodation supply with Airbnb and Couchsurfing, respectively. The findings suggest that regulation strictness is positively related to PE supply. In the specific case of short-stay accommodation platforms that involve money transactions, such as Airbnb, we see that supply increases with the increasing strictness of rules but less than in free short-stay accommodation platforms, such as Couchsurfing. These findings serve to inform policy makers in their debate on whether it is better to adopt a laissez-faire approach or regulatory interference to promote the growth of the PE (cf. Uzunca, Rigtering, and Ozcan Citation2018). As Miller (Citation2016) underlines, an appropriate direction is still missing to address the regulation of the PE.

2. Literature review

PE growth and regulation are closely linked, and a burgeoning literature in legal scholarship has started to focus extensively on this relationship (Ranchordás Citation2015; Davidson and Infranca Citation2016; Lobel Citation2016; Biber et al. Citation2017; Light Citation2018; Pollman and Barry Citation2016). There is an abundant tradition of studying sharing, reciprocity, bartering, and gift-giving that can be of use when considering the PE (Kolm Citation2000). For instance, Belk underlines the mechanisms of sharing (Belk, Tian, and Paavola Citation2010) and the relationship between sharing and the PE (Belk Citation2014). Some scholars in particular focus on the reasons that lead people to participate in the PE (Hamari, Sjöklint, and Ukkonen Citation2016). There is also a rich emerging literature on the regulation of PE that highlights the need and conditions for regulating digital platforms (Ranchordás Citation2015; Schor Citation2016; Miller Citation2016). However, the lack of a clear understanding of the mechanisms that drive the interaction between PE supply and regulation makes it problematic to forecast whether an increase in regulation encourages or harms supply in digital platforms. Here, we provide a brief synopsis of the literature on ‘does regulation stimulate PE supply?’ The first part of the literature review describes the PE and outlines how supply in these digital platforms are reforming labor practices in major parts of the economy and industrial value chains. In the second part, we identify discrepancies and gaps concerning three related questions: 1) How does regulation affect the PE? 2) How does supply emerge in the PE? 3) How do money transactions influence PE supply?

2.1. What is the PE?

The PE is a broad term for a set of business models, platforms, and exchanges that mediates social and economic exchanges online (Kenney and Zysman Citation2016). From a sharing economy perspective, PE enables better exchange of underutilized goods and services (Schor Citation2016), and these exchanges are made available through digital platforms. The distinguishing characteristics include a decentralized market, a focus on access over ownership of resources, an emphasis on firms becoming the facilitator of negotiation (rather than acting as a producer), and mechanisms of self-governance (Botsman and Rogers Citation2011). A common definition of sharing platforms among scholars is still missing. Most of the emerging literature adopts the following definition of the sharing economy: ‘consumers granting each other temporary access to their underutilized physical assets, possibly for money’ (Frenken et al. Citation2015). This definition allows us to qualify both Airbnb (for money) and Couchsurfing (for free) as sharing platforms. In the specific cases of Airbnb and Couchsurfing, supplier users offer their houses, spare rooms, or even couches on the platform. Frenken et al. (Citation2015) underline three major aspects of this definition:

Sharing is about consumer-to-consumer (C2C) platforms and not about renting or leasing a right from a company (business-to-consumer).

Sharing is about consumers giving each other temporary access to a good and not about the transfer of ownership of the good. Thus, the PE does not include the second-hand economy, in which goods are sold or given away to consumers.

PE is about a more cost-effective use of tangible assets and not about private individuals providing each other a service.

Some scholars include immaterial exchanges (time and skills) such as transportation, cooking, and teaching services in the PE (Botsman and Rogers Citation2011, Schor Citation2016). Another definition that complements Botsma and Rogers’s and Frenken’s points of view is the Sundararajan (Citation2016) interpretation of PE from a sharing economy perspective. The author defines the PE as economic systems that have five key features:

Market-based: the PE produces markets that permit the exchange of goods and the rise of innovative services, resulting in possibly higher levels of commercial activity.

High-impact capital: the PE exposes new possibilities for a wide range of transactions, from assets and skills to time and capital, that allow resources to be used at levels resembling their total potential.

Crowd-based ‘networks’ rather than centralized organizations or ‘hierarchies’: the amount of capital and labor comes from decentralized people on a peer-to-peer basis rather than corporations. In the future, exchange could be negotiated by shared crowd-based marketplaces rather than by centralized third parties.

Blurring lines separating the personal and the professional: the quantity of work and services often commercializes and scales peer-to-peer activities such as offering somebody transportation or lending someone cash, activities that used to be recognized as ‘personal.’

Blurring lines between full-time and casual labor, between independent and dependent work, and between job and leisure: many commonly full-time employment opportunities are replaced by arrangement work that features a continuum of levels of time commitment, economic dependence and entrepreneurship.

When taken together, these definitions do not entirely apply to Airbnb, as the platform also facilitates transactions that do not involve ‘underutilized physical assets.’ Airbnb is often used to convert what has formerly been a housing unit into a de facto hotel room. Therefore, we adopt the recently proposed expanded definition of the sharing economy, which explicitly captures both market and nonmarket logics and practices (Laurell and Sandström Citation2017, 63): ‘ICT-enabled platforms for exchanges of goods and services drawing on nonmarket logics such as sharing, lending, gifting and swapping as well as market logics such as renting and selling.’

Given the number of definitions that have emerged and the diverse ways the PE affects our daily lives, sharing platforms provide viable alternatives for people to offer short-term accommodation in their houses. Here, we focus particularly on platforms concerning short-term accommodations. Several scholars have begun to analyze these platforms, particularly the effect of short-term accommodation platforms on the tourism industry and hotels (Zervas, Proserpio, and Byers Citation2017; Guttentag Citation2015). Airbnb is one of the digital platforms through which people can monetize their underutilized location and showcase it to an audience of millions (Botsman and Rogers Citation2011; Hempel Citation2012). Airbnb is disrupting the hotel industry (Guttentag Citation2015). New York City, which has the second-highest concentration of Airbnb listings per million people in the U.S., is seeing drops in revenue per available room, the primary indicator of the hotel industry’s financial health (Brown and Dev Citation1999). Couchsurfing is often advertised as the symbol for short-stay accommodation in the PE (Kamenetz Citation2011; Sacks Citation2011). Couchsurfing employs a variety of mechanisms and reputation systems to connect travelers with willing hosts at their destination and, perhaps more importantly, to build a high degree of trust among strangers (Kas, Corten, and van de Rijt Citation2018). Couchsurfing continues to maintain its original philosophy, and its free-stay business model is, in principle, its core competence. ‘Sharing for free’ is what encourages reciprocity and connection among guests and hosts, encouraging them to spend time together (Lauterbach et al. Citation2009). If there was payment involved, the service would be just another place to sleep at night, like Airbnb.

2.2. How does regulation affect the PE?

Several researchers have examined the impact of regulation on innovation and other business performance outcomes (Cosh and Hughes Citation2003; Cosh and Wood Citation1998). Since the PE is an emerging phenomenon, regulation has not yet made full progress (Lobel Citation2016; Biber et al. Citation2017). This ongoing process results in heterogeneous regulation across countries and even within the same country. In the U.S., Marshall (Citation2017) demonstrates that digital platforms have features that make old regulatory frameworks inadequate, and Miller (Citation2016) suggests that existing regulation is unable to support this new phenomenon. As a result of the lack of appropriate and adequate regulation, a major portion of the PE is still regulated under the old rules of its incumbent competitors (Davidson and Infranca Citation2016; Light Citation2018; Pollman and Barry Citation2016). The regulation of sharing companies such as Airbnb is a new issue for regulators, and a bulletproof solution is still missing (Geron Citation2013).Footnote3

Different studies have investigated the effects of regulation strictness, such as restrictions on land use and on house and vacant land prices (Quigley and Raphael Citation2005; Ihlanfeldt Citation2007), and have found that land use laws have significant impacts on the prices of accommodations, rents, and vacant land. No study has yet examined whether and how regulation strictness in the emergence of PE is related to the supply of short-stay accommodations. Studies by both Quigley and Raphael (Citation2005) and Ihlanfeldt (Citation2007) address a number of methodological shortcomings found in prior work on land use regulation, but much work remains to be done. In particular, one needs to look specifically at local zoning laws and laws regulating short-term accommodation. The legal literature focusing on regulation shows that policy makers have tried to apply tax limitations and incumbent rules to PE businesses (Ranchordás Citation2015; Davidson and Infranca Citation2016). The New York State Supreme Court stated, ‘While Expedia, Priceline, and Hotwire are best defined as retailers and resellers and, as such, can be controlled and taxed accordingly, it is much harder to find a comparable taxing analogue for the Internet-Sharing Economy’ (Dickerson and Sylvia Citation2016). Many municipalities in the U.S. have started regulating home sharing or have begun inquiries with the intention of inducing the PE to acquiesce to current laws (Logan Citation2014; Roomscore Citation2016; Pollman and Barry Citation2016). Airbnb now has an overview of the local laws that may apply to hosts in various jurisdictions in the U.S. To help its users comply with state regulation, Airbnb automatically and for free distributes tax forms to hosts that receive over $20,000 in rents and host more than 200 people via Airbnb in a year (Airbnb Citation2017). The PE disrupts the traditional framework of government regulation because the relationship among the participants is ambiguous in Airbnb (Ranchordás Citation2015). The taxes owed to different parties and nonparties in Airbnb transactions are hard to determine (Dickerson and Sylvia Citation2016). Authorities in the U.S. have also been pushing to regulate short-term housing with a focus on liability and tax payment (Hantman Citation2015). Recent regulations in February 2015 in Airbnb’s hometown of San Francisco implemented several limitations: homeowners who lend their houses or rooms in their first residence must have $500,000 in liability insurance, live in the residence for at least 270 days of the year, acquire an Airbnb license, obtain permission from the city hall, and maintain the house free of building code infractions (Hantman Citation2015). After this ordinance, Airbnb declared that it would provide supplemental responsibility insurance to its hosts for free. Portland officially accepted short-term renting of family homes and introduced some mandatory laws in January 2015 (Hantman Citation2015). It is important to emphasize another aspect of Portland’s regulation: the Portland City Council decided to modify the definition of a hotel to include any ‘house, duplex, condominium, multi-dwelling structure, trailer home, [and] houseboat’ rented for less than thirty consecutive days (Portland Citation2015). This modification is a typical example of attempting to fit Airbnb into the existing legal framework. Chicago and Washington, D.C., started raising hotel taxes for Airbnb in February 2015 (Badger Citation2015). Nashville, Tennessee, passed regulations for Airbnb on 26 February 2015 (Nashville Citation2017). As seen, many U.S. cities are moving towards the inclusion of Airbnb in the legal framework. Some European capitals, such as Amsterdam and Berlin, have been quicker to react to home sharing than their U.S. counterparts. In Europe, legislators have tried to create appropriate new laws to regulate short-stay accommodations, while regulations passed in major U.S. cities so far have focused mainly on requiring insurance coverage and obtaining tourist taxes from Airbnb hosts (Hantman Citation2015). Taxes are a central point of interest; however, it is more important to focus on appropriate, long-term-oriented, and well-grounded regulation of the PE (see our Roomscore dataset explanation in the methods section). Limiting the number of days per year that a place can serve as Airbnb is a temporary solution, not a definitive one, as there are several such platforms (City of Amsterdam Citation2017). As seen, although a great deal is happening, the major portion of the PE is still regulated by old rules made for incumbents or is in a gray area of regulation (Franzetti Citation2015). Couchsurfing, as Lampinen (Citation2016) underlines, is still mostly based on the concept of self-regulation and legitimacy granted by the community. There is not, as of today, a particular local rule that regulates the use of Couchsurfing. The main area of concern about Couchsurfing regulation is privacy management (Lampinen Citation2016), but this debate is outside the scope of this paper.

2.3. How does supply emerge in the PE?

Notwithstanding a recent wave in awareness of the PE, a great deal remains to be discovered about the emergence of supply in the PE (Tussyadiah and Pesonen Citation2015; Grassmuck Citation2012). Hamari, Sjöklint, and Ukkonen (Citation2016) investigate people’s motivations to take part in the PE, and their results reveal that participation in the PE is driven by many factors, such as the sustainability of participation, economic gains, and enjoyment of the activity. These findings provide insight into how supply emerges in the PE. While some scholars argue that economic reasons are the principal factor for PE supply to emerge (Bardhi and Eckhardt Citation2012; Bellotti et al. (Citation2015), other scholars contend that environmental motivations lead people to supply the PE (Botsman and Rogers Citation2011; Gansky Citation2010). Botsman and Rogers (Citation2011) propose that social motivations also increase PE supply. According to Botsman and Rogers (Citation2011), people offer short-term accommodation because they want to socialize with their guest (Tussyadiah and Pesonen Citation2015). A quantitative investigation into PE supply is still mostly missing. Böcker and Meelen (Citation2016) reveal that supply in the PE differs among sociodemographic groups, within users and providers, and, in particular, among various types of shared goods: accommodation, cars, rides, tools and meals. The supply of short-term accommodation is profoundly economically driven according to these authors’ findings. Younger people are more economically driven to use and provide shared assets through Airbnb. Younger, higher-income, and well-educated groups are less socially driven, and women are more environmentally motivated. None of these studies consider an important element in the emergence of supply: the existence (or lack thereof) of regulation. People could avoid offering their homes/rooms in the PE because of regulation. Especially in the short-term accommodation market, which is typically heavily regulated (Malpezzi Citation1996), the strictness, or total absence thereof, of a robust legal framework could discourage people from becoming a supplier to the PE (Mattson-Teig Citation2015) and, for example, listing their properties on Airbnb or Couchsurfing.

2.4. How does the presence of monetary transactions influence PE supply?

Hamari, Sjöklint, and Ukkonen (Citation2016) developed a model to demonstrate the motivational reasons behind PE participation and discovered that PE is often seen as not only ecologically but also economically appealing. Belk, Tian, and Paavola (Citation2010) and Lamberton and Rose (Citation2012) similarly explain that PE supply could be led by rational, utility maximizing behavior because the consumer substitutes ownership of goods with lower-cost alternatives from a platform. In the previous literature, there are indications of both positive and negative impacts of including money transactions on sharing behavior (Bock et al. Citation2005; Kankanhalli, Tan, and Wei Citation2005). Hars and Ou (Citation2001) analyze the intrinsic drivers of supplying for free in open source projects and find that a strong motivation is the possibility of future economic benefits. Prothero et al. (Citation2011) underline that sharing operates as an incentive for saving economic resources in the system.

3. Hypothesis development

We aim to examine whether the presence of strict regulation is associated with a higher or lower supply of short-term accommodation in the PE. The mechanisms through which such regulation influences PE supply are still understudied. On the one hand, it is possible that stricter regulation is synonymous with a certain legal framework and that people have clarity on what is legal and what it is forbidden. Regulation also creates clear boundaries for a playing field for companies, thus incentivizing innovation and entrepreneurship. It is plausible that people feel safer in a city with strict legislation that leaves no room for doubt. A legislation gap leads to regulatory uncertainty, and the aggregate PE supply stagnates, as people are naturally averse to uncertainty (Morgan, Henrion, and Small Citation1992; Liu Citation2010). On the other hand, it is also plausible that a strict and articulated legal framework might decrease PE supply because a high level of regulation strictness could indicate bans and restrictions on the PE. If regulatory intervention is strict, it could kill incentives for innovation and entrepreneurship. Our broad inquiry – Does regulation stimulate the supply of short-term accommodations in the PE? – forms the core of the research investigated in this paper. While both explanations are plausible, we think the former dominates the latter (Cosh and Hughes Citation2003); it is possible that PE supply is positively related to regulation strictness.

(H1) Regulation strictness is positively associated with PE supply.

Second, we aim to disclose the difference in the relationship between regulation and PE supply when money is involved or not. On the one hand, we could claim that in the presence of a monetary gain, supply will be more sensitive to regulation, as people will be more inclined to follow the rules. Higher attention to rules when money transactions are involved could indicate why Airbnb is banned or limited in many cities, while Couchsurfing is still free of bans in all U.S. cities. In that case, we could say that the presence of monetary transactions in the platform mitigates the positive relationship between regulation and PE supply. It is possible that the presence of money in the transaction makes people more conscious and hesitant to break the rules and be fined. Users who rent rooms for money on Airbnb are more concerned with the possible fines, so legislation has a stronger association with their behavior (Mattson-Teig Citation2015). For instance, New York City legislators fined two Airbnb users in February 2017 for purportedly listing various short-term home rentals on Airbnb. The New York City Council strongly limited the proliferation of Airbnb after 2016 (Miller and Jefferson-Jones Citation2017), and the city fined the two hosts $17,000 each. On the other hand, we can also underline that there is a strong positive correlation between house prices and regulation (Glaeser, Gyourko, and Saks Citation2003). Higher house prices are positively correlated with the possibility of gains from Airbnb (Jefferson-Jones Citation2015). We could also argue that if there is strict regulation, there are also higher income opportunities, which could justify a positive influence of money transactions on PE supply in the case of strict regulation. However, our literature review hints that the former dominates the latter; thus, we hypothesize that the presence of money transactions in the platform mitigates the positive relationship between regulation and PE supply.Footnote4 That is, the aggregate number of people who share their property on Airbnb will increase less than the aggregate number of people who share their property on Couchsurfing as regulation becomes stricter.

(H2) The presence of money transactions in the platform negatively moderates the positive relationship between regulation strictness and PE supply.

4. Methodology and data

The purpose of this paper is to investigate the relationship between regulation strictness and PE supply (H1) and to further understand how this relationship is affected by the presence or absence of money transactions (H2). To accomplish this purpose, we needed to select a context of study that is representative to investigate PE supply and regulation strictness. We chose the U.S. because it is a prime example of a heterogeneous country where stark differences between regulatory responses have emerged across cities (Tzur Citation2017). The U.S. is, therefore, the perfect context to test the influence of different levels of regulation strictness on short-term accommodation supply in the PE.

4.1. Dependent variable – supply

There is not yet a perfect measure to capture the emergence of the PE in a country (Nicholls Citation2016), and the number of offerings on digital platforms is the best proxy to verify supply in the PE. We thus focused on active hosts who list accommodations on two major short-stay accommodation platforms to capture the suppliers of listed homes. It is more logical that legislation will influence someone who is willing to share his house rather than a renter (Mattson-Teig Citation2015). To determine how many hosts list short-stay accommodations on Airbnb in a city, we used the AirDNA database (https://www.airdna.co/). AirDNA provides an assembly of Airbnb data collected from publicly accessible information on the Airbnb website. The AirDNA database traces the offerings of over 4 million Airbnb listings around the world. In 2017, AirDNA identified a total of 650,000 Airbnb listings in the U.S. California led all states with 125,803 total properties listed, followed by New York with 94,976 Airbnb rentals (see ). Hawaii led the ranking for Airbnb-listed houses per inhabitants with 10.61 listings for every one thousand citizens. Washington D.C. is technically not one of the 50 states, as it does not have a deciding delegation in Congress, and the federal administration reserves power over the municipality. However, as we focused on city-level data in our analysis and the definition of a city is based on the metropolitan region, Washington D.C. was included in our dataset.

We used the tool Investment Explorer, a built-in app on the AirDNA portal, to verify the number of listed active hosts in 2018. It was important for our research purpose to use the AirDNA dataset because AirDNA contains only ‘active’ hosts and listings. A large portion of the listings on Airbnb are created and never rented, which could occur because creating a listing for a house on Airbnb requires only a few minutes and is free. Many people try to create a listing for their home without proceeding to the actual renting of the house on Airbnb. Thus, to avoid data inaccuracy, we used the AirDNA dataset for the 59 U.S. cities for which we had the Roomscore index. We explain these cities in detail in the next section when we describe our regulation strictness index.

Couchsurfing listings were taken directly from the organization’s web site: www.couchsurfing.com. The website provides detailed information on listed locals who offer short-stay accommodation. The number of hosts available in each city in 2018 was exported to create the second dependent variable of interest, i.e., PE supply without money transaction. We created a dummy variable, money, to identify whether the supplied short-stay accommodation was rented for money, i.e., on Airbnb, or for free, i.e., on Couchsurfing (we explain this variable later). This variable is called supply.

4.2. Independent variable – regulation strictness

The main independent variable that we used to predict our dependent variable, supply, was regulatory strictness. We used the Roomscore index (http://www.roomscore.org/), which assesses 59 U.S. cities for their openness to commerce conducted through short-term rental platforms such as Airbnb, Couchsurfing, HomeAway (and its related brand, Vacation Rentals by Owner or VRBO), FlipKey (a brand of TripAdvisor), and even Craigslist. Roomscore was built by R Street (a nonprofit public policy research organization with a particular ideological orientation towards anti-regulation and pro free markets) during 2015 and 2016 after extensively reviewing municipal and state requirements (since both can have a significant impact on PE supply), proceedings of legislative sessions, legal filings, and press reports to help illuminate the state of short-term rental regulation in U.S. cities. This investigation is supported by conversations with lodging regulators in cities when necessary.

The Roomscore index focuses on five key policy areas: legal framework, restrictions, taxation, licensing requirements, and enforcement. Each city starts with a base score of 90, and points are added or deducted based on how open/strict the city is with regards to these policy areas. Therefore, the lower the Roomscore is, the stricter regulation is in the city (see for the Roomscore scoring methodology).Footnote5 We considered inverting this index to make it consistent with our aim in this research, but using a ‘reversed’ index of regulatory freedom is not necessarily intuitive and may have econometric implications. Therefore, we maintained the original Roomscore index.Footnote6

Table 1. Roomscore scoring methodology.

For the 59 U.S. cities, the average overall Roomscore was 74.7, and the median score was 73.5. Cities with these scores received a letter grade of C. The standard deviation among the scores was 14.3, indicating a wide variance in scoring. The maximum value was 97 (for the cities of Galveston and Savannah), and the lowest value was 50 (for the cities of Atlanta, Denver, and Oklahoma City). See for the Roomscore results for our sample of 59 cities.

Table 2. Roomscore results for 59 U.S. cities.

Despite not being developed specifically for our research purposes (Roomscore is a general index with the aim of providing trends for the evolving regulatory frameworks for short-term rentals), it is safe to say that Roomscore is highly related to our interest in capturing regulation strictness for short-stay accommodation. This relation can be seen in the questions asked when forming the measure. The Roomscore index is formed by answering the following questions (for the five policy areas mentioned above):

Does the city have a tailored legal framework for short-term rental regulation?

What, if any, legal restrictions are in place to curb short-term rentals?

What tax-collection obligations are placed on short-term rental services?

How burdensome and expensive is the city’s licensing regime for short-term rentals?

How hostile is the city’s enforcement regime for short-term rentals, including restrictions that do not fit neatly into the prior categories?

We also included several control variables compiled from auxiliary datasets, which are explained below.

4.3. Long-term rents, house prices, and hotel prices

Guttentag (Citation2015) defines the short-term accommodation sector as part of the (informal) accommodation sector, and he underlines a strong correlation between the use of these platforms and the prices of other accommodation options in the zone. Therefore, it is natural to search for the counter argument that the relation may go from high rental, housing, or hotel prices to having higher/lower supply rather than from regulation to supply. We thus needed to isolate the relationship between regulation and PE supply by controlling for various alternative explanations, such as hotel prices, local property prices, and longer-term rents, in our empirical analysis. For example, if long-term rental prices are higher, the supply of short-term housing might be negatively affected, as owners will tend to opt for the better paying option.Footnote7 For long-term rental prices, we used Numbeo (www.numbeo.com), the world’s largest database of user contributed data about cities and countries worldwide. Numbeo provides information on world living conditions, including cost of living, housing indicators, health care, traffic, crime, and pollution. We manually collected from Numbeo the price of an apartment (1 bedroom) in the city center per month for our 59 cities.

Another alternative explanation is that PE supply might be related to housing prices. While there is an endogenous relationship between these two variables (i.e., while more PE supply leaves fewer houses on the housing market for locals to buy, driving up housing prices, higher housing prices will in return decrease new PE supply, as people will not be able to easily buy more houses). Thus, we believe that controlling for local property prices was important for our analysis. We used the median sales price of existing single-family homes from National Association of Realtors for Metropolitan Areas (https://www.nar.realtor/) for our cities of interest.

Finally, we needed to consider how regulation is in association with local price, availability, and quality influences the competition faced by short-term accommodation platforms. Strict regulation might make entry more lucrative, but the relationship may go from high hotel prices to having many entries rather than from regulation to entry. To isolate the relationship between regulation and PE supply, we controlled for hotel prices in each city.Footnote8 Our data came from Business Travel News’ (BTN’s) Corporate Travel Index, which ranks U.S. cities in terms of hotel accommodation costs.Footnote9 We double-checked the accuracy of these data from the Hotel Price Index of Hotels.com (https://hpi.hotels.com/), which reports the average hotel prices per room per night paid by visitors.

4.4. Population

Another control variable that we considered is the population of the city. It is reasonable to think that the more people there are in a city, the greater the short-term accommodation supply in the PE. We accessed data from the U.S. Census dataset. The U.S. Census Bureau is a major agency of the U.S. Federal Demographic System, responsible for providing data about the American economy and population. We double-checked the accuracy of these data through the Wikipedia pages for our 59 cities.

4.5. GDP

This control variable is related to the overall prosperity of people living in a city. Gross domestic product (GDP) is commonly used to determine the economic performance of a whole country or region, and we included this index as a control variable because the wealth of people is also correlated with PE supply (Cansoy and Schor Citation2017). The source of the data was the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis.

4.6. Number of hotels

Zervas, Proserpio, and Byers (Citation2014) conducted an extensive study on the close relationship between the availability of hotels and Airbnb. The strong relationship that connects the supply in these two industries needed to be controlled to estimate the impact of regulation on PE supply. The number of hotels in each of our 59 cities was taken from www.booking.com, the largest worldwide portal for booking a room in a hotel.

4.7. Dummy variable – money

To test our H2, we needed to create a dummy variable to separate how regulation strictness is related to supply for the platform that involves money transaction, Airbnb, from the supply for the platform that does not require a money transaction, Couchsurfing. This dummy variable had a value of zero for Couchsurfing and one for Airbnb.

4.8. Econometric specifications

Our econometric model involved the relationship between the dependent variable, supply, and the independent variable, regulation strictness, as well as its interaction with money and the control variables. This multivariate regression specification is depicted below (Aiken and West Citation1991):

We introduced these variables in a stepwise fashion, but we considered the full model to test our hypotheses. As there were missing values in the hotel and housing prices, the total number of observations dropped in the full model. However, it was eventually a stricter test of our hypotheses since we controlled for all the main variables that could influence PE supply. Concerning the temporal unit of analysis, all the supply data were the most up-to-date data available from 2018. The Roomscore index was from 2016. However, this time gap did not cause any problems for the analysis because regulation strictness is not expected to change drastically in the short run (moreover, the relationship between regulation and supply is not immediately observed).Footnote10 For these reasons, we contend that this two-year gap was acceptable for our analysis.

As an initial step, we considered which of the socioeconomic factors associated with each U.S. city was significantly correlated with PE supply. We used a linear regression model in the form of ordinary least squares (OLS) (see Models 1, 2, 3). We tested our OLS models for autocorrelation by calculating Moran’s test (Putnam 2001) on the residuals.

5. Results

We report our findings in two sections. First, we discuss cross-correlations between our variables. Second, we explain the regression results we obtained to answer our research question.

To provide an overview of which of our variables are correlated with each other, we estimated the cross-correlation matrix and the means and standard deviations for the variables (). We note that the first column shows which variables are correlated with our dependent variable, PE supply. As expected, PE supply tends to be negatively correlated with regulation strictness (which means higher strictness is correlated with higher supply). Since some of our independent variables present high levels of cross-correlations, we expected that some of the variables that were highly correlated with PE supply would not show the same significance levels in the regression analysis.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations.

We report the results of the OLS model in . We discovered a negative coefficient (i.e., positive relationship) between PE supply and regulation strictness. In the first model, we included only regulation strictness and money. From Model 2 onward, we included the interaction effect and control variables in a stepwise manner. Because the coefficients were relatively stable across models and because Model 3 offered the best fit (including the full model), we argue that Model 3 offers the test of our hypotheses (though we briefly discuss all models below).

Table 4. The association between regulation strictness and PE supply.

The regression results for Model 1 were significant. The significance of the coefficient of regulation strictness could result from omitted variables bias, and to correct for this, we added the control variables in Models 2 and 3. In Model 2, we introduced some of our control variables and the interaction effect with the dummy variable money into the regression. The 0.675 R-squared means that our model explains more than half of the variance in PE supply, although the correlations among the independent variables might tend to inflate the standard errors in the regressions.Footnote11 However, the average variance inflation factor (VIF) for all the covariates is 5.05, which is below the common threshold of 10 (Ryan Citation1997). Therefore, multicollinearity between the variables was not considered a significant concern.

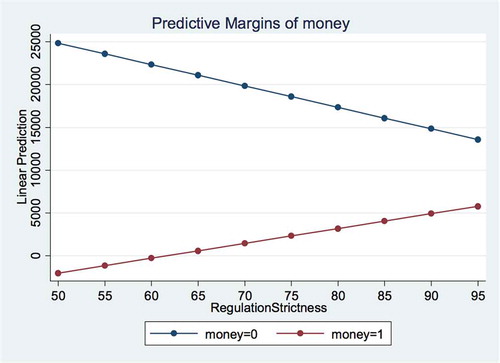

The increased significance of Model 2 means that Model 2 is more reliable than Model 1 for predicting PE supply. We see that in Model 2, regulation strictness is still positively related to PE supply and is significant at the p < 0.1 level. The interaction effect with money is negative and significant at the p < 0.05 level.Footnote12 Among the control variables, only population is significant. In Model 3, we inserted two more control variables, GDP and hotel prices, and the results remained the same.Footnote13 The strong and negative relationship between money and PE supply is also notable, and this is visible in . The coefficient of regulation strictness still has a significant and positive association with PE supply.

6. Discussion and conclusion

With this research, we aimed to understand the mechanisms that explain the relationship between the supply of short-term accommodation and regulation. Here, we provide a summary of our answer to our research question: ‘Does regulation stimulate supply in short-stay accommodation platforms?’ We first discuss why our results confirm our hypothesis together with the practical and theoretical implications. We then discuss the limitations of this research and highlight possible future research directions.

Hypothesis 1 – Regulation strictness is positively associated with PE supply.

We find that the stricter regulation is, the higher the PE supply. Our results indicate that all else being equal, a decrease of one Roomscore index point in short-term rental regulation increases PE supply by 250 hosts, on average. This increase sounds plausible because if there are more rules and a legitimate legal framework, the supply of short-term accommodation would be higher due to more certainty about the legal and illegal activities concerning the PE. The estimated coefficient of regulation strictness is both statistically and economically significant. This result also complies with the previous literature. People are naturally averse to uncertainty (Morgan, Henrion, and Small Citation1992; Liu Citation2010), and an increase in legislation diminishes legal uncertainty. Cosh and Hughes (Citation2003) also provide evidence that innovative activity is positively affected when regulation provides clear guidelines. Our study builds on these findings by showing that regulation strictness is positively related to PE supply, and this discovery has practical implications. Policy makers willing to increase the supply in digital sharing platforms can focus more on regulating the PE (in terms of giving clear guidelines and clarity) rather than adopting a laissez-faire approach (cf. Uzunca, Rigtering, and Ozcan Citation2018).

Hypothesis 2 – The presence of money transactions in the platform negatively moderates the positive relationship between regulation strictness and PE supply.

The sign of the coefficient for the interaction term in Model 3 is suggestive. The positive and statistically significant association indicates that we can accept H2. PE supply has a less positive relationship () to regulation strictness in for-money platforms, such as Airbnb, compared to free-stay-based platforms, such as Couchsurfing. Specifically, for every one-point decrease in the Roomscore index, we see 423 () fewer hosts in the increase in PE supply compared to the same relationship with free PE supply. This finding sounds reasonable because if regulation strictness increases (i.e., Roomscore index decreases), there will be more enforcement of the imposition of penalties (Joerges and Vos Citation1999), which will in turn increase the chances of fines (Weiser Citation2005). The estimated interaction coefficient of ‘money*regulation strictness’ is both statistically and economically significant, and this result complies with the previous literature. Mattson-Teig (Citation2015) reports that users who rent the rooms for money on Airbnb are more afraid of possible fines, so legislation has a stronger effect on their behaviors. Short-term accommodation platforms based on free-stay, such as Couchsurfing, are still mostly based on the concept of self-regulation and legitimacy granted by the community. When there is a lower possibility of receiving a fine when sharing their home for free (Lampinen Citation2016), people are less negatively affected by regulation strictness concerning supplying these platforms. Free-stay-based short-term accommodation platforms are less influenced by legislation because they are based on sharing, reciprocity, and gift-giving principles (Kolm Citation2000) and not on a ‘similar short-term rental agreement’ (Lauterbach et al. Citation2009).

6.1. Limitations

This paper is subject to certain limitations that offer opportunities for future research. First, while we explicitly state that our focus is on short-term accommodation platforms, similar research on other forms of sharing, such as cars, rides, tools and meals, should be performed to produce a more generalizable claim for the whole PE. As Böcker and Meelen (Citation2016) reveal, supply in the PE differs among sociodemographic groups, within users and providers, and, in particular, among various types of shared goods. Future research should conduct a broader analysis including other contexts in which PE is prevalent, such as transportation and goods sharing. Second, another limitation of the model is the lack of a time variable to monitor the relationship between PE supply and regulation strictness over time. Although the time gap between our variables (i.e., the Roomscore index is from 2016, while our dependent variable, PE supply, is from 2018) does not undermine a cross-sectional comparison (quite the opposite, the presence of this time gap ensures that regulation came first and then PE supply was observed), it could be beneficial to utilize a longitudinal approach, ideally a panel dataset. Similarly, a natural experiment concerning a drastic regulatory change in a certain area would prove to be very fruitful for future research.

Finally, we conducted our analysis only in U.S. cities due our focus on having substantial variance in regulatory strictness. While the U.S. is a large, heterogeneous, and economically diverse country that offers the ability to study PE supply, further research comparing multiple geographical locations and countries is needed to guarantee the robustness of our findings (cf. Boon, Spruit, and Frenken, Citationforthcoming).

6.2. Future research

Scholars could focus on the below set of questions to expand the findings of this research:

Are money transactions and free-stay-based platforms substitutes or complements in the PE?

Will too much regulation decrease PE supply?

If so, how can regulators determine the point at which there is too much regulation, thus hindering PE growth?

A proper index for measuring PE supply is still lacking. It could be interesting to develop an official index to measure PE growth and involvement across the world.

Since Airbnb has whole home listings as well as house sharing, it would be interesting to distinguish these two. In many cities, Airbnb is a platform used by commercial operators, e.g., in Sydney, some hosts have as many as 100 properties. Such hosts are likely to have a different view of regulation from a household renting out a spare bedroom.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 The PE includes Internet-based businesses that mediate social and economic interactions (Kenney and Zysman Citation2016). For example, Airbnb is a ‘platform business’ built around connecting property owners with short-term lodgers. Compared to the related concept of the ‘sharing economy’ – defined as an economic system in which assets or services are shared between private individuals either for free or for a fee, typically by means of the Internet – we adopt the term ‘platform economy’ to reflect the role of platform intermediaries that match supply with demand (Light Citation2018; Lobel Citation2016).

3 There have been some efforts to look at PE regulation at the city level. For example, Tzur (Citation2017) groups 40 U.S. cities in regulatory categories for ride-sharing, such as weak, medium, and strong, in terms of their regulatory approaches to transport network companies (TNCs). Karanovic, Berends, and Engel (Citation2018) use this grouping to analyze how Uber drivers frame the company in cities with diverse regulatory approaches to TNCs. A similar initiative for short-term accommodation has been established by the R Street Institute with its Roomscore index (http://www.rstreet.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/RSTREET55.pdf).

4 For the counter argument that the association may go from high housing prices to having higher supply rather than from regulation to supply, we isolate the association between regulation and PE supply by controlling for various alternative explanations, such as hotel prices, local property prices, and longer-term rents in our empirical analysis.

5 The full report explaining the methodology in detail can be found on http://www.rstreet.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/RSTREET55.pdf.

6 We are grateful to an anonymous reviewer for raising this issue. The empirical results are evaluated in the next section according to this directionality; a lower Roomscore index score indicates higher regulation strictness.

7 Within the same city, increasing long-term rental prices, while keeping short-term housing prices constant, will decrease short term rental supply.

8 We are grateful to our editor for raising this issue.

10 Also, regulation often takes longer to respond to increasing supply than the other way around (i.e., supply is more responsive to regulation). In this sense, our focus in the paper is more on the initial emergence of short-term accommodation in a city (given regulation strictness).

11 It is logical to have correlations between the control variables in our case since populated areas have higher number of hotels, higher long term rental prices, higher housing price, etc.

12 As mentioned before, due to the nature of the calculation of the Roomscore Index, a negative (positive) coefficient indicates a positive (negative) relationship between regulation strictness and PE supply.

13 One might argue that p < 0.1 is not a very high level of significance, but given the number of observations and all the included control variables in the regressions, we performed a conservative and strict test of our hypotheses.

References

- Aiken, L. S., and S. G. West. 1991. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. London: Sage.

- Airbnb. 2017. “About Us. Airbnb.” Accessed 6 June 2017. https://www.airbnb.com/

- Badger, E. 2015. “Airbnb Is about to Start Collecting Hotel Taxes in More Major Cities, Including Washington.” WASH. POST, January 29. Accessed 26 June 2017. http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/wonkblog/wp/2015/01/29/airbnb-is-about-to-start-collecting-hotel-taxes-in-more-major-cities-includingwashington

- Bardhi, F., and G. M. Eckhardt. 2012. “Access-Based Consumption: The Case of Car Sharing.” Journal of Consumer Research 39 (4): 881–898. doi:10.1086/666376.

- Belk, R. 2014. “You are What You Can Access: Sharing and Collaborative Consumption Online.” Journal of Business Research 67 (8): 1595–1600. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.10.001.

- Belk, R. W., K. Tian, and H. Paavola. 2010. “Consuming Cool: Behind the Unemotional Mask.” In Research in Consumer Behavior edited by R. Belk, Vol. 12, 183–208. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Bellotti, V., A. Ambard, D. Turner, C. Gossmann, K. Demkova, and J. M. Carroll. 2015. “A Muddle of Models of Motivation for Using Peer-To-Peer Economy Systems.” Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1085–1094. Seoul, Republic of Korea: ACM, April 18–23, 2015.

- Biber, E., S.E. Light, J.B. Ruhl, and J. Salzman. 2017. “Regulating Business Innovation as Policy Disruption: From the Model T to Airbnb.” Vanderbilt Law Review 70: 1561–1626.

- Bock, G. W., R. W. Zmud, Y. G. Kim, and J. N. Lee. 2005. “Behavioral Intention Formation in Knowledge Sharing: Examining the Roles of Extrinsic Motivators, Social-Psychological Forces, and Organizational Climate.” MIS Quarterly 87–111. doi:10.2307/25148669.

- Böcker, L., and A. A. H. Meelen. 2016. “Sharing for People, Planet or Profit? Analysing Motivations for Intended SE Participation.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 23: 28–39. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2016.09.004.

- Boon, W. P. C., K. Spruit, and K. Frenken. forthcoming. “Collective Institutional Work: The Case of Airbnb in Amsterdam, London and New York.” Industry & Innovation. doi:10.1080/13662716.2019.1633279.

- Botsman, R., and R. Rogers. 2011. What’s Mine Is Yours: How Collaborative Consumption Is Changing the Way We Live. London: Collins.

- Boudreau, K. 2010. “Open Platform Strategies and Innovation: Granting Access Vs. Devolving Control.” Management Science 56 (10): 1849–1872. doi:10.1287/mnsc.1100.1215.

- Brown, J. R., and C. S. Dev. 1999. “Looking beyond RevPAR: Productivity Consequences of Hotel Strategies.” The Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 40 (2): 23–33. doi:10.1177/001088049904000213.

- Cansoy, M., and J.B. Schor. 2017. “Who Gets to Share in the Sharing Economy: Racial Discrimination on Airbnb.” Working Paper, Boston College.

- City of Amsterdam. 2017. “Short Stay Policy.” Accessed 26 June 2017. http://www.iamsterdam.com/en/local/live/housing/rental-property/shortstay/

- Cosh, A., and A. Hughes. 2003. “Innovation Activity: Outputs, Inputs, Intentions and Constraints.” In Enterprise Challenged, edited by A. Cosh and A. Hughes, 45–56. Cambridge: ESRC Centre for Business Research, University of Cambridge.

- Cosh, A., and E. Wood. 1998. “Innovation: Scale, Objectives and Constraints.” In Enterprise Britain, edited by A. Cosh and A. Hughes, 38–48. Cambridge: ESRC Centre for Business Research, University of Cambridge.

- Davidson, N. M., and J. Infranca. 2016. “The Sharing Economy as an Urban Phenomenon.” Yale Law and Policy Review 34: 215–279.

- Dickerson, T., and O. Sylvia. 2016. “Taxing Internet Transactions: Airbnb and the SE.” 86 N.Y. ST. B.J. 49, 50.

- Eisenmann, T., G. Parker, and M. W. Van Alstyne. 2006. “Strategies for Two-Sided Markets.” Harvard Business Review 84 (10): 92.

- Franzetti, A. 2015. “Risks of the Sharing Economy.” Risk Management 62 (3): 10–12.

- Frenken, K., T. Meelen, M. Arets, and P. van de Glind 2015. “Smarter Regulation for the SE.” The Guardian, 20.

- Gansky, L. 2010. The Mesh: Why the Future of Business Is Sharing. New York: Penguin.

- Geron, T. 2013. “Airbnb and the Unstoppable Rise of the Share Economy.” FORBES, January 23. Accessed 25 June 2017. http://www.forbes.com/sites/tomiogeron/2013/01/23/airbnb-and-the-unstoppable-rise-of-theshare-economy

- Glaeser, E. L., J. Gyourko, and R. Saks 2003. Why Is Manhattan so Expensive? Regulation and the Rise in House Prices ( No. w10124). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Grassmuck, V. R. 2012. “The Sharing Turn: Why We are Generally Nice and Have a Good Chance to Cooperate Our Way Out of the Mess We Have Gotten Ourselves Into.” In Cultures and Ethics of Sharing, edited by W. Sützl, F. Stalder, R. Maier, and T. Hug. doi:10.1094/PDIS-11-11-0999-PDN.

- Guttentag, D. 2015. “Airbnb: Disruptive Innovation and the Rise of an Informal Tourism Accommodation Sector.” Current Issues in Tourism 18 (12): 1192–1217. doi:10.1080/13683500.2013.827159.

- Hagiu, A., and J. Wright. 2015. “Multi-Sided Platforms.” International Journal of Industrial Organization 43: 162–174. doi:10.1016/j.ijindorg.2015.03.003.

- Hamari, J., M. Sjöklint, and A. Ukkonen. 2016. “The SE: Why People Participate in Collaborative Consumption.” J Assn Inf Sci Tec 67: 2047–2059. doi:10.1002/asi.23552.

- Hantman. 2015. “Working Together to Collect and Remit in Washington D.C. And Chicago, Illinois.” Accessed 26 June 2017. http://www.chicagotribune.com/bluesky/originals/chi-airbnb-chicago-taxes-bsi-20150130-story.html

- Hars, A., and S. Ou. 2001. “Working for Free? Motivations of Participating in Open Source Projects.” System Sciences, 2001. Proceedings of the 34th Annual Hawaii International Conference on, 9. Maui, HI: IEEE.

- Hempel, J. 2012. “More than a Place to Crash.” Fortune. Accessed 3 July 2017. http://tech.fortune.cnn.com/2012/05/03/airbnb-apartments-social-media/

- Ihlanfeldt, K. R. 2007. “The Effect of Land Use Regulation on Housing and Land Prices.” Journal of Urban Economics 61 (3): 420–435. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2006.09.003.

- Jefferson-Jones, J. 2015. “Can Short-Term Rental Arrangements Increase Home Values?: A Case for Airbnb and Other Home Sharing Arrangements.” Cornell Real Estate Review 13 (1): 12–19.

- Joerges, C., and E. Vos, Eds. 1999. EU Committees: Social Regulation, Law and Politics, 311–338). Oxford: Hart.

- Kamenetz, A. 2011. “The Case for Generosity.” Fast Company 153(March 2011): 52–54.

- Kankanhalli, A., B. C. Tan, and K. K. Wei. 2005. “Contributing Knowledge to Electronic Knowledge Repositories: An Empirical Investigation.” MIS Quarterly 113–143. doi:10.2307/25148670.

- Karanovic, J., H. Berends, and Y. Engel 2018. “Is Platform Capitalism Legit? Ask the Workers.” Working paper.

- Kas, J., R. Corten, and A. van de Rijt 2018. “Experimental Evaluation of Single-Role and Mixed-Role Reputation Systems in a Trust Game and a Lending Game.” Working paper.

- Kenney, M., and J. Zysman. 2016. “The Rise of the Platform Economy.” Issues in Science and Technology 32 (3): 61–69.

- Kolm, S. C. 2000. “Introduction: The Economics of Reciprocity, Giving and Altruism.” In Iea Conference Volume Series. 130 vols., 1–46. Basingstoke: Macmillan Press; New York: St Martin’s Press; 1998.

- Lamberton, C. P., and R. L. Rose. 2012. “When Is Ours Better than Mine? A Framework for Understanding and Altering Participation in Commercial Sharing Systems.” Journal of Marketing 76 (4): 109–125. doi:10.1509/jm.10.0368.

- Lampinen, A. 2016. “Hosting Together via Couchsurfing: Privacy Management in the Context of Network Hospitality.” International Journal of Communication 10: 20.

- Laurell, C., and C. Sandström. 2017. “The Sharing Economy in Social Media: Analyzing Tensions between Market and Non-Market Logics.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 125: 58–65. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2017.05.038.

- Lauterbach, D., H. Truong, T. Shah, and L. Adamic. 2009. “Surfing a Web of Trust: Reputation and Reciprocity on Couchsurfing. Com.” Computational Science and Engineering, 2009. CSE’09. International Conference on, 4 vols., 346–353. Vancouver, Canada: IEEE.

- Light, S. E. 2018. “The Role of the Federal Government in Regulating the Sharing Economy (October 3, 2017).” In Cambridge Handbook on the Law of the Sharing Economy, edited by N. Davidson, M. Finck, and J. Infranca. Cambridge Univ. Press. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3047322

- Liu. 2010. Uncertainty Theory: A Branch of Mathematics for Modeling Human Uncertainty. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

- Lobel, O. 2016. “The Law of the Platform 101.” Minnesota Law Review 87: 88–89.

- Logan, T. 2014. “Airbnb Touts Its Economic Benefits as L.A. Leaders Seek to Clamp Down, L.A.” TIMES, December 4. Accessed 25 June 2017. http://www.latimes.com/business/la-fi-airbnb-la-20141205-story.html

- Malpezzi, S. 1996. “Housing Prices, Externalities, and Regulation in US Metropolitan Areas.” Journal of Housing Research 7: 209–242.

- Marshall, P. 2017. “Issue: The SE Short Article: Advice for the SE.” Accessed March 30. businessresearcher.sagepub.com

- Mattson-Teig, B. 2015. “Residential Managers Police AIRBNB “Guests”.” Journal of Property Management 80 (5): 32–37.

- Miller, S. R. 2016. “First Principles for Regulating the Sharing Economy.” Forthcoming ABA Probate & Property.

- Miller, S. R., and J. Jefferson-Jones 2017. “AirBNB and the Battle between Internet. Exceptionalism and Local Control of Land Use.” Forthcoming ABA Probate & Property.

- Morgan, M. G., M. Henrion, and M. Small. 1992. Uncertainty: A Guide to Dealing with Uncertainty in Quantitative Risk and Policy Analysis. New York: Cambridge university press.

- Nashville, T. “Ordinance BL2014-951.2015.” Accessed 26 June 2017. http://www.nashville.gov/mc/ordinances/term_2011_2015/bl2014_951.htm

- Nicholls, K. 2016. “The Feasibility of Measuring the Sharing Economy: Progress Update. An Update on the Work Undertaken by the Office for National Statistics so Far on Assessing the Feasibility of Measuring the SE in the UK.” Accessed 17 April 2017. https://www.ons.gov.uk/releases/thefeasibilityofmeasuringthesharingeconomyprogressupdate

- Pollman, E., and J. M. Barry. 2016. “Regulatory Entrepreneurship.” Southern California Law Review 90: 383–448.

- Portland, O. R. 2015. “Zoning Code Ch. 33.207; Portland, Or., Amend Transient Lodgings Tax to Add Definitions and Clarify Duties for Operators for Short-Term Rental Locations.” Accessed 26 June 2017. http://media.oregonlive.com/front-porch/other/Short-term%20rental%20ordinance.pdf

- Prothero, A., S. Dobscha, J. Freund, W. E. Kilbourne, M. G. Luchs, L. K. Ozanne, and J. Thøgersen. 2011. “Sustainable Consumption: Opportunities for Consumer Research and Public Policy.” Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 30 (1): 31–38. doi:10.1509/jppm.30.1.31.

- Quigley, J. M., and S. Raphael. 2005. “Regulation and the High Cost of Housing in California.” The American Economic Review 95 (2): 323–328. doi:10.1257/000282805774670293.

- Ranchordás, S. 2015. “Does Sharing Mean Caring: Regulating Innovation in the SE.” Minnesota Journal of Law, Science & Technology 16: 413.

- Rochet, J. C., and J. Tirole. 2003. “Platform Competition in Two-Sided Markets.” Journal of the European Economic Association 1 (4): 990–1029. doi:10.1162/154247603322493212.

- Roomscore 2016. “Roomscore 2016: Short-Term-Rental Regulation in U.S. Cities.” Accessed 12 February 2018. https://www.rstreet.org/2016/03/16/roomscore-2016-short-term-rental-regulation-in-u-s-cities/

- Ryan, T. 1997. Modern Regression Analysis. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

- Sacks, D. 2011. “The Sharing Economy.” Fast Company ( 155 May), 88–93.

- Schor, J. 2016. “Debating the Sharing Economy.” Journal of Self-Governance and Management Economics 4 (3): 7–22. doi:10.22381/JSME4320161.

- Sundararajan, A. 2016. The Sharing Economy: The End of Employment and the Rise of Crowd-Based Capitalism. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Tussyadiah, I. P., and J. Pesonen. 2016. “Impacts of Peer-To-Peer Accommodation Use on Travel Patterns.” Journal of Travel Research 55 (8): 1022–1040.

- Tzur, A. 2017. “Uber Über Regulation? Regulatory Change following the Emergence of New Technologies in the Taxi Market.” Regulation & Governance. Advance online publication. doi:10.1111/rego.12170.

- Uzunca, B., J. C. Rigtering, and P. Ozcan. 2018. “Sharing and Shaping: A Cross-Country Comparison of How Sharing Economy Firms Shape Their Institutional Environment to Gain Legitimacy.” Academy of Management Discoveries 4 (3): 248–272. doi:10.5465/amd.2016.0153.

- Weiser, P. J. 2005. “The Relationship of Antitrust and Regulation in a Deregulatory Era.” Antitrust Bull. 50: 549.

- Zervas, G., D. Proserpio, and J. W. Byers. 2017. “The Rise of the Sharing Economy: Estimating the Impact of Airbnb on the Hotel Industry.” Journal of Marketing Research 54 (5): 687–705.